Rick Just's Blog, page 92

June 19, 2022

The Columbian Bell (tap to read)

Miss Hattie Felix Harris of Boise, a Columbian Club member, oversaw Idaho’s participation in a nationwide project that garnered the support of tens of thousands of people. The Columbia Liberty Bell was one of countless efforts to get on the bandwagon for the 1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago.

I’ve written previously about all the effort that went into constructing and furnishing the Idaho Building for the Exposition and Boise’s venerable Columbian Club, which is the last such club still active in the United States.

The Columbia Liberty Bell was the brainchild of William Dowell of New Jersey. He sought thousands of contributions to the project. Money was necessary, of course, but he envisioned a bell that included relics from history melted down to help form the bell. According to the website Chicagology, the bell included “ The keys of Jefferson Davis’ house, pike heads used by John Brown at Harper’s Ferry, John C, Calhoun’s silver spoon and Lucretia Mott’s silver fruit knife, Simon Bolivar’s watch chain, hinges from the door of Abraham Lincoln’s house at Springfield, George Washington’s surveying chain, Thomas Jefferson’s copper kettle, Mrs. Parnell’s earrings, and Whittier’s pen.”

Hattie Felix Harris stirred up interest in Idaho donations, which included “Bullion, gold and silver, besides some very rare relics.” In the May 13, 1893 article summing up the Idaho drive, the only item specifically noted was “a beautiful specimen of silver bullion taken from the DeLamar Mine” in Owyhee County.

Harris supplied the newspaper with a list of the monetary donations for counties around the state, totaling $110.

The Columbian Liberty Bell was cast on the evening of June 22, 1893, with at least 1,000 people looking on at the Meneely Bell Foundry in Troy, New York. That conglomeration of items and materials included in the pour did not affect it, according to Mr. Maneely, in a New York Times article the following day. “Mr. Maneely says… the great bulk of the material is copper and tin, and the gold and silver form only a small portion of the whole mass.”

And, what a mass it was. The bell weighed 13,000 pounds and stood seven feet high.

The Columbian Liberty Bell arrived late for its date in Chicago. It rang several times during the Exposition for various events. Crowd interest was not what promoters had hoped. There was so much else to see.

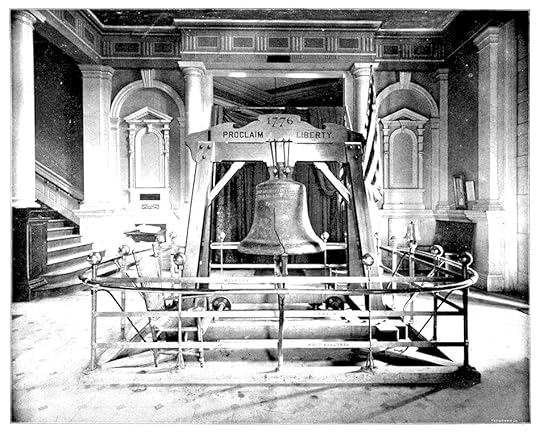

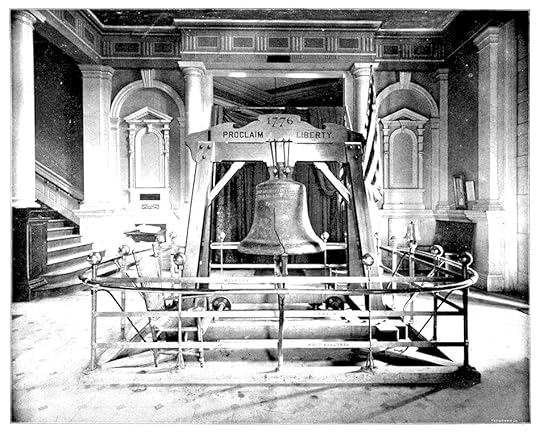

After the Exposition closed, the bell went on a world tour. And that was the end of it. How one loses track of a 13,000-pound bell is puzzling. The best guess anyone has is that it was melted down during the Bolshevik revolution. The Columbian Bell on exhibit in Chicago in 1893.

The Columbian Bell on exhibit in Chicago in 1893.

I’ve written previously about all the effort that went into constructing and furnishing the Idaho Building for the Exposition and Boise’s venerable Columbian Club, which is the last such club still active in the United States.

The Columbia Liberty Bell was the brainchild of William Dowell of New Jersey. He sought thousands of contributions to the project. Money was necessary, of course, but he envisioned a bell that included relics from history melted down to help form the bell. According to the website Chicagology, the bell included “ The keys of Jefferson Davis’ house, pike heads used by John Brown at Harper’s Ferry, John C, Calhoun’s silver spoon and Lucretia Mott’s silver fruit knife, Simon Bolivar’s watch chain, hinges from the door of Abraham Lincoln’s house at Springfield, George Washington’s surveying chain, Thomas Jefferson’s copper kettle, Mrs. Parnell’s earrings, and Whittier’s pen.”

Hattie Felix Harris stirred up interest in Idaho donations, which included “Bullion, gold and silver, besides some very rare relics.” In the May 13, 1893 article summing up the Idaho drive, the only item specifically noted was “a beautiful specimen of silver bullion taken from the DeLamar Mine” in Owyhee County.

Harris supplied the newspaper with a list of the monetary donations for counties around the state, totaling $110.

The Columbian Liberty Bell was cast on the evening of June 22, 1893, with at least 1,000 people looking on at the Meneely Bell Foundry in Troy, New York. That conglomeration of items and materials included in the pour did not affect it, according to Mr. Maneely, in a New York Times article the following day. “Mr. Maneely says… the great bulk of the material is copper and tin, and the gold and silver form only a small portion of the whole mass.”

And, what a mass it was. The bell weighed 13,000 pounds and stood seven feet high.

The Columbian Liberty Bell arrived late for its date in Chicago. It rang several times during the Exposition for various events. Crowd interest was not what promoters had hoped. There was so much else to see.

After the Exposition closed, the bell went on a world tour. And that was the end of it. How one loses track of a 13,000-pound bell is puzzling. The best guess anyone has is that it was melted down during the Bolshevik revolution.

The Columbian Bell on exhibit in Chicago in 1893.

The Columbian Bell on exhibit in Chicago in 1893.

Published on June 19, 2022 04:00

June 18, 2022

Ralph Dixey (tap to read)

No one expected much of the Shoshone and Bannock people in the late 1800s. Their way of life, following fish, game, and plants with the seasons, ended when they were pushed onto the Fort Hall Reservation and told they were now farmers. Some were unable to cope with a life they didn't understand. They received little help from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The narrative of failure and talk of lazy, alcoholic Indians became the broad-stroke story for many settlers in the area. But what is often untold is the Shoshone-Bannock people's success despite the odds against them.

Some Tribal members embraced opportunity when they saw it. Ralph Dixey is one of those people who has fascinated me since I first learned about him.

Ralph Willet Dixey was born in Boise on July 4, 1874. Orphaned at age four, he went to Ross Fork to live with an uncle. In 1879, Ralph's uncle began farming on 160 acres near the Blackfoot River, where he put in a small dam to irrigate crops.

Ralph grew up learning about irrigation, farming, and ranching. In 1921 he and others on the reservation formed the Fort Hall Indian Stockman's Association. Most Indian cattle and horse owners, some 150, became members. Dixey served as its president for the first ten years of the organization.

The Association grew and cut most of its own hay, fenced grazing areas, developed watering systems, and purchased prime breeding stock. In short order, the stock they raised became well known for its quality. The Association commonly had about 6500 head of cattle and horses running on a range of nearly 70,000 acres.

Although the cattle buyers came from as far away as southern California, the Stockman's Association sold most of the beef locally, believing it would build goodwill with the white community.

Ralph Dixey was well known in Blackfoot for managing the Southeastern Idaho Round-Up and Livestock Show, which became a major part of the Eastern Idaho State Fair.

Dixey's leadership role on the reservation took him to Washington, DC, more than once to testify before Congress on behalf of his people. The press sometimes mistakenly called him Chief Dixey.

This stockman of some note was known for his horses and his horsepower. Dixey was a car guy. In 1917, he became one of the first owners of a Willys-Knight Eight in Idaho. Then, in 1919, he surprised everyone, including his wife, when he bought her a Stutz Bearcat Roadster so she could drive into town whenever she pleased.

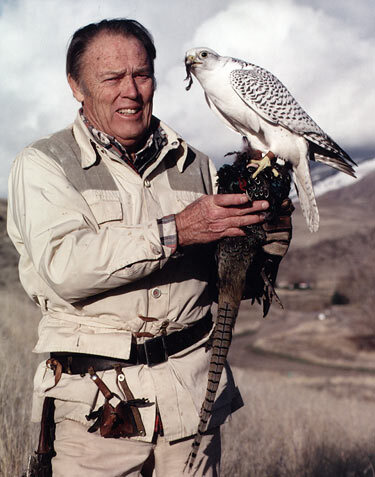

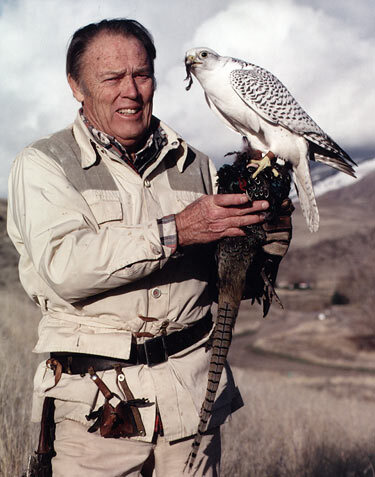

Ralph Dixey was a man who straddled two worlds. Proud of his native heritage, he made warbonnets for Hollywood movies and recorded war dance songs to preserve them. At the same time, he was a successful businessman. Dixey died at age 96 in 1959. Ralph Dixey in traditional dress.

Ralph Dixey in traditional dress.  A 1917 Willys-Knight 8 similar to the one driven by Ralph Dixey.

A 1917 Willys-Knight 8 similar to the one driven by Ralph Dixey.  Dixey bought his wife a Stutz Bearcat.

Dixey bought his wife a Stutz Bearcat.

The narrative of failure and talk of lazy, alcoholic Indians became the broad-stroke story for many settlers in the area. But what is often untold is the Shoshone-Bannock people's success despite the odds against them.

Some Tribal members embraced opportunity when they saw it. Ralph Dixey is one of those people who has fascinated me since I first learned about him.

Ralph Willet Dixey was born in Boise on July 4, 1874. Orphaned at age four, he went to Ross Fork to live with an uncle. In 1879, Ralph's uncle began farming on 160 acres near the Blackfoot River, where he put in a small dam to irrigate crops.

Ralph grew up learning about irrigation, farming, and ranching. In 1921 he and others on the reservation formed the Fort Hall Indian Stockman's Association. Most Indian cattle and horse owners, some 150, became members. Dixey served as its president for the first ten years of the organization.

The Association grew and cut most of its own hay, fenced grazing areas, developed watering systems, and purchased prime breeding stock. In short order, the stock they raised became well known for its quality. The Association commonly had about 6500 head of cattle and horses running on a range of nearly 70,000 acres.

Although the cattle buyers came from as far away as southern California, the Stockman's Association sold most of the beef locally, believing it would build goodwill with the white community.

Ralph Dixey was well known in Blackfoot for managing the Southeastern Idaho Round-Up and Livestock Show, which became a major part of the Eastern Idaho State Fair.

Dixey's leadership role on the reservation took him to Washington, DC, more than once to testify before Congress on behalf of his people. The press sometimes mistakenly called him Chief Dixey.

This stockman of some note was known for his horses and his horsepower. Dixey was a car guy. In 1917, he became one of the first owners of a Willys-Knight Eight in Idaho. Then, in 1919, he surprised everyone, including his wife, when he bought her a Stutz Bearcat Roadster so she could drive into town whenever she pleased.

Ralph Dixey was a man who straddled two worlds. Proud of his native heritage, he made warbonnets for Hollywood movies and recorded war dance songs to preserve them. At the same time, he was a successful businessman. Dixey died at age 96 in 1959.

Ralph Dixey in traditional dress.

Ralph Dixey in traditional dress.  A 1917 Willys-Knight 8 similar to the one driven by Ralph Dixey.

A 1917 Willys-Knight 8 similar to the one driven by Ralph Dixey.  Dixey bought his wife a Stutz Bearcat.

Dixey bought his wife a Stutz Bearcat.

Published on June 18, 2022 04:00

June 17, 2022

"Crazy" Schweitzer (tap to read)

I find that readers are always eager to learn how some town or geographical feature came by its name. Today I’ll explain the genesis of the name Schweitzer Mountain, as best I can. There seems little information on Mr. Schweitzer except that he was something of a hermit who lived on the mountain and that he had served in the Swiss Army. Oh, and there’s the little detail about the cats.

Let’s start with a bit about Ella M. Farmin, courtesy of the book Idaho Women in History , by Betty Penson-Ward. Farmin was one of the earliest residents of Sandpoint, and is credited with civilizing the place a bit. At one time in the early days Sandpoint had 110 residents and 23 saloons, according to the book. Farmin turned one of those saloons into a Sunday School (at least on Sundays), and organized the Civic Club in town

Penson-Ward’s book is about Idaho women, so doesn’t mention Ella’s husband. The Farmins built the first house in Sandpoint, proving up their homestead in 1898.

I’m walking down this path with Ella Farmin, because in 1892 she was the telegraph operator who barely escaped an attack by “a crazy man.” The sheriff tracked the man to his cabin on the mountain where, as the story goes, he was “boiling cats for his dinner.” Pet cats had been going missing for some time and this seemed to explain that little mystery. Mr. Schweitzer was escorted to an asylum and disappeared from history, leaving only his last name behind to mark the mountain where he once lived.

This is the first ski lodge under construction at Schweitzer in 1963. The lodge later burned down and more elaborate facilities have replaced it. Lake Pend Oreille is in the distance.

This is the first ski lodge under construction at Schweitzer in 1963. The lodge later burned down and more elaborate facilities have replaced it. Lake Pend Oreille is in the distance.

Let’s start with a bit about Ella M. Farmin, courtesy of the book Idaho Women in History , by Betty Penson-Ward. Farmin was one of the earliest residents of Sandpoint, and is credited with civilizing the place a bit. At one time in the early days Sandpoint had 110 residents and 23 saloons, according to the book. Farmin turned one of those saloons into a Sunday School (at least on Sundays), and organized the Civic Club in town

Penson-Ward’s book is about Idaho women, so doesn’t mention Ella’s husband. The Farmins built the first house in Sandpoint, proving up their homestead in 1898.

I’m walking down this path with Ella Farmin, because in 1892 she was the telegraph operator who barely escaped an attack by “a crazy man.” The sheriff tracked the man to his cabin on the mountain where, as the story goes, he was “boiling cats for his dinner.” Pet cats had been going missing for some time and this seemed to explain that little mystery. Mr. Schweitzer was escorted to an asylum and disappeared from history, leaving only his last name behind to mark the mountain where he once lived.

This is the first ski lodge under construction at Schweitzer in 1963. The lodge later burned down and more elaborate facilities have replaced it. Lake Pend Oreille is in the distance.

This is the first ski lodge under construction at Schweitzer in 1963. The lodge later burned down and more elaborate facilities have replaced it. Lake Pend Oreille is in the distance.

Published on June 17, 2022 04:00

June 16, 2022

Rock Cairns (tap to read)

You’ve probably seen a rock cairn somewhere in your travels. People with an artistic bent often leave little stacks of rock in or alongside riverbeds, a tribute to their balancing abilities.

Just don’t. Artistic as your stones may be, they are a distraction from the natural beauty people have come to see. Moving rocks around disturbs micro-ecosystems, often killing creepy crawly critters that might not be on anyone’s list of favorite animals, but are an important part of nature. If you must stack, do it in your yard. End of editorial.

Stone cairns are common on all continents. Stacking rocks is an ancient way to mark things. They may be memorial markers, markers to locate caches, and in later years, property markers on the corner of lots.

In Idaho, Basque sheepherders made stone cairns to mark trails or just to pass the time. They are called “harrimutilak’ or stone boys. They could be over six feet tall. I remember one at the top of Garden Creek Peak in Bingham County when I was a kid. It may not have been a Basque cairn, since it was on the Forth Hall Reservation, but I remember my dad calling it a “sheepherders monument.” You could see it for miles around.

Post Office Creek, which runs into the Lochsa, got its name from a misunderstanding about Nez Perce cairns in the area. Meriwether Lewis wrote about them in his June 27, 1806 journal entry: “…on this eminence the nativs have raised a conic mound of Stons of 6 or 8 feet high and erected a pine pole of 15 feet long.” According to Borg Hendrickson and Linwood Laughy’s 1989 book, Clearwater Country!, two such mounds were at the head of the creek. They became known as Indian Post Office because people believed the Nez Perce left messages for one another on or in the cairns. Lewis had been told they were markers for trails and fishing sites, which seems more likely.

Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.

Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.  Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar.

Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar.

Just don’t. Artistic as your stones may be, they are a distraction from the natural beauty people have come to see. Moving rocks around disturbs micro-ecosystems, often killing creepy crawly critters that might not be on anyone’s list of favorite animals, but are an important part of nature. If you must stack, do it in your yard. End of editorial.

Stone cairns are common on all continents. Stacking rocks is an ancient way to mark things. They may be memorial markers, markers to locate caches, and in later years, property markers on the corner of lots.

In Idaho, Basque sheepherders made stone cairns to mark trails or just to pass the time. They are called “harrimutilak’ or stone boys. They could be over six feet tall. I remember one at the top of Garden Creek Peak in Bingham County when I was a kid. It may not have been a Basque cairn, since it was on the Forth Hall Reservation, but I remember my dad calling it a “sheepherders monument.” You could see it for miles around.

Post Office Creek, which runs into the Lochsa, got its name from a misunderstanding about Nez Perce cairns in the area. Meriwether Lewis wrote about them in his June 27, 1806 journal entry: “…on this eminence the nativs have raised a conic mound of Stons of 6 or 8 feet high and erected a pine pole of 15 feet long.” According to Borg Hendrickson and Linwood Laughy’s 1989 book, Clearwater Country!, two such mounds were at the head of the creek. They became known as Indian Post Office because people believed the Nez Perce left messages for one another on or in the cairns. Lewis had been told they were markers for trails and fishing sites, which seems more likely.

Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.

Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.  Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar.

Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar.

Published on June 16, 2022 04:00

June 15, 2022

Morley Nelson (tap to read)

Idaho is a mecca for raptor lovers from all over the world. That’s because it is a magnet for birds of prey. The World Center for Birds of Prey is in Boise, Boise State University is home to the Raptor Research Center and offers the only Masters of Science in Raptor Research, and The Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area (NCA)is south of Kuna.

The birds congregate in the NCA not because it is a protected area, but because it is an ideal place for raptors to live. The uplift of air from the Snake River Canyon makes flying and gliding (sorry) a breeze for the birds, and the uplands above the canyon rim provide habitat for ground squirrels and other critters the birds consider lunch.

Morley Nelson figured that out when he first saw the canyon in the late 1940s. He had developed a love for raptors—especially peregrine falcons—growing up on a farm in North Dakota. When he moved to Idaho, following a WWII stint with the famous Tenth Mountain Division, he went out to the Snake River Canyon to see if he could find some raptors. He found a few. There are typically about 800 pairs of hawks, eagles, owls, and falcons that nest there each spring. It’s the greatest concentration of nesting raptors in North America, and probably the world.

Nelson became evangelical about the birds and their Snake River Canyon habitat. He worked on films about the birds with Walt Disney, Paramount Pictures, the Public Broadcasting System, and others. His passion for the birds was contagious, and through his efforts public understanding of their role in the natural world was greatly enhanced.

Morley Nelson convinced Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton to establish the Snake River Birds of Prey Natural area in 1971, and an expansion of the area by Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus in 1980. Then in 1993, US Representative Larry LaRocco led an effort in Congress to designate some 485,000 acres as a National Conservation Area.

It was also Nelson who led the effort to convince the Peregrine Fund to relocate to Boise and build the World Center for Birds of Prey south of town.

While those efforts were going on, Nelson was also doing pioneer work on an effort to save raptors from power line electrocution. He worked with the Edison Electric Institute and Idaho Power to study how raptors used those manmade perches known as power poles. Through those efforts poles are now designed to minimize electrocution and even provide safe nesting areas for the birds.

When Morley Nelson passed away in 2005 he had unquestionably done more to save and protect raptors than any other single person.

For more on Morley Nelson, see his biography, Cool North Wind , written by Steve Steubner.

The birds congregate in the NCA not because it is a protected area, but because it is an ideal place for raptors to live. The uplift of air from the Snake River Canyon makes flying and gliding (sorry) a breeze for the birds, and the uplands above the canyon rim provide habitat for ground squirrels and other critters the birds consider lunch.

Morley Nelson figured that out when he first saw the canyon in the late 1940s. He had developed a love for raptors—especially peregrine falcons—growing up on a farm in North Dakota. When he moved to Idaho, following a WWII stint with the famous Tenth Mountain Division, he went out to the Snake River Canyon to see if he could find some raptors. He found a few. There are typically about 800 pairs of hawks, eagles, owls, and falcons that nest there each spring. It’s the greatest concentration of nesting raptors in North America, and probably the world.

Nelson became evangelical about the birds and their Snake River Canyon habitat. He worked on films about the birds with Walt Disney, Paramount Pictures, the Public Broadcasting System, and others. His passion for the birds was contagious, and through his efforts public understanding of their role in the natural world was greatly enhanced.

Morley Nelson convinced Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton to establish the Snake River Birds of Prey Natural area in 1971, and an expansion of the area by Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus in 1980. Then in 1993, US Representative Larry LaRocco led an effort in Congress to designate some 485,000 acres as a National Conservation Area.

It was also Nelson who led the effort to convince the Peregrine Fund to relocate to Boise and build the World Center for Birds of Prey south of town.

While those efforts were going on, Nelson was also doing pioneer work on an effort to save raptors from power line electrocution. He worked with the Edison Electric Institute and Idaho Power to study how raptors used those manmade perches known as power poles. Through those efforts poles are now designed to minimize electrocution and even provide safe nesting areas for the birds.

When Morley Nelson passed away in 2005 he had unquestionably done more to save and protect raptors than any other single person.

For more on Morley Nelson, see his biography, Cool North Wind , written by Steve Steubner.

Published on June 15, 2022 04:00

June 14, 2022

Lava Hot Springs (tap to read)

Dempsey Idaho Was a Hot Spot

So, you haven’t heard of Dempsey, largely because it wasn’t called that for long. Dempsey was in southeastern Idaho, where Bob Dempsey, a trapper, had his camp for about 10 years from 1851 to 1861. He moved to the Montana gold fields after that and dropped off the map. The town named after him got a post office in 1895, but the name Dempsey disappeared in 1915, when they started calling the place Lava Hot Springs, which is more reflective of the major draw to the town.

The hot springs were deeded to the State of Idaho in 1902. In 1913, the hot springs site became a state park, and the state built a natatorium there in 1918. In 1967 management of the site was taken over by the newly formed Lava Hot Springs Foundation, a group appointed by the governor to run the place. That foundation is still in existence today, running a large complex of water features.

The pools at Lava Hot Springs are from 102 to 112 degrees. Their Olympic-sized outdoor pool has diving boards, high and low diving platforms, and corkscrew waterslides. Next to the pool is the big waterslide that comes swooping in right across the main road into town.

Located about 45 minutes south of Pocatello not far off I-15, Lava Hot Springs is a major draw for Utah recreationists.

So, you haven’t heard of Dempsey, largely because it wasn’t called that for long. Dempsey was in southeastern Idaho, where Bob Dempsey, a trapper, had his camp for about 10 years from 1851 to 1861. He moved to the Montana gold fields after that and dropped off the map. The town named after him got a post office in 1895, but the name Dempsey disappeared in 1915, when they started calling the place Lava Hot Springs, which is more reflective of the major draw to the town.

The hot springs were deeded to the State of Idaho in 1902. In 1913, the hot springs site became a state park, and the state built a natatorium there in 1918. In 1967 management of the site was taken over by the newly formed Lava Hot Springs Foundation, a group appointed by the governor to run the place. That foundation is still in existence today, running a large complex of water features.

The pools at Lava Hot Springs are from 102 to 112 degrees. Their Olympic-sized outdoor pool has diving boards, high and low diving platforms, and corkscrew waterslides. Next to the pool is the big waterslide that comes swooping in right across the main road into town.

Located about 45 minutes south of Pocatello not far off I-15, Lava Hot Springs is a major draw for Utah recreationists.

Published on June 14, 2022 04:00

June 13, 2022

The Lapwai Press (tap to read)

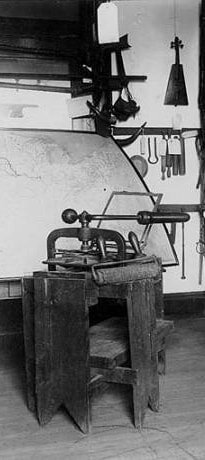

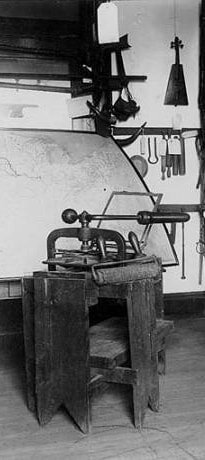

Idaho became a state in 1890, as probably everyone reading this knows. It was 1959 before Hawaii became a state, yet it was to Hawaii that Reverend Henry Harmon Spalding turned to obtain a major machine of civilization. In 1838 Spalding wrote to the Congregational mission in Honolulu, “requesting the donation of a second-hand press and that the Sandwich Islands Mission should instruct someone, to be sent there from Oregon, in the art of printing, and in the meantime print a few small books in Nez Perces.”

The Sandwich Islands would later become the Hawaiian Islands, and the Oregon Spalding referred to what was then Oregon Territory, where his own Lapwai Mission stood. It would not become Idaho Territory until 1863, long after the Spaldings had fled the territory.

According to the book, The Lapwai Mission Press, by Wilfred P. Schoenberg, S.J., from which the quotes in this post are also taken, no book of Nez Perce was printed in Hawaii, though a proof consisting of a couple of pages of set type for a Nez Perce spelling book created by Spalding and his wife Eliza was printed. Instead, the Sandwich Island Mission prepared to fulfill Spalding’s main request, which was for a printing press to be sent to Lapwai.

The press they would send, was the fifth press in Hawaii. It would be the first in the Pacific Northwest, the eighth in what would become the West of the United States. Importantly, it is the only one of those first eight still in existence.

The Sandwich Island Mission sent not just the press, but the pressman. Edwin Oscar Hall, a lay minister in the congregation, would accompany the press to Lapwai. He agreed to do so partly because his wife’s health would benefit from a cooler climate.

Hall set up the press and began working it on May 16, 1839, three days after they arrived at Lapwai. He set about running proof sheets, and by May 24 he had printed four hundred copies of an 8-page book using an artificial alphabet of the Nez Perce Spalding had devised. This “reader for beginners and children” was the first book printed in Oregon Territory. If you had a copy of that thin tome it would be worth quite a lot today. But you don’t, because shortly after the little books were printed they were destroyed.

In July, 1839, all the missionaries of Oregon Territory got together to discuss the book. They found Spalding’s attempt to create a Nez Perce alphabet and provide a means for translating the language could not “be relied on for books, or as a standard in any sense.”

The Reverend Asa Bowen Smith edited a new version of Spalding’s book, which would be called First Book: Designed For Children And New Beginners.” It was published in August, 1839.

The book the missionaries rejected and ordered destroyed, lived on in a way. In later years it was discovered that some pages of that earliest printing were used in the cover and binding of the new “first book.”

The printer Hall and his wife returned to the Sandwich Islands in May of 1840, leaving the press behind.

In 1842 or 43 the press was used to print a book for young readers in the Spokane language, a book of The Laws and Statutes, and a hymn book. Spalding labored for two years on a Nez Perce translation of the gospel of St. Matthew. It was printed in 1845. That year the last of the imprints from the Lapwai press appeared, a “vocabulary” of Nez Perce and English words. In 1846 the press was moved to The Dalles. It had a short history printing The Oregon and American Evangelical Unionist, and, years later, in 1875, was donated to the Oregon State Historical Society in Salem, where it resides today.

The Lapwai Press. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

The Lapwai Press. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

The Sandwich Islands would later become the Hawaiian Islands, and the Oregon Spalding referred to what was then Oregon Territory, where his own Lapwai Mission stood. It would not become Idaho Territory until 1863, long after the Spaldings had fled the territory.

According to the book, The Lapwai Mission Press, by Wilfred P. Schoenberg, S.J., from which the quotes in this post are also taken, no book of Nez Perce was printed in Hawaii, though a proof consisting of a couple of pages of set type for a Nez Perce spelling book created by Spalding and his wife Eliza was printed. Instead, the Sandwich Island Mission prepared to fulfill Spalding’s main request, which was for a printing press to be sent to Lapwai.

The press they would send, was the fifth press in Hawaii. It would be the first in the Pacific Northwest, the eighth in what would become the West of the United States. Importantly, it is the only one of those first eight still in existence.

The Sandwich Island Mission sent not just the press, but the pressman. Edwin Oscar Hall, a lay minister in the congregation, would accompany the press to Lapwai. He agreed to do so partly because his wife’s health would benefit from a cooler climate.

Hall set up the press and began working it on May 16, 1839, three days after they arrived at Lapwai. He set about running proof sheets, and by May 24 he had printed four hundred copies of an 8-page book using an artificial alphabet of the Nez Perce Spalding had devised. This “reader for beginners and children” was the first book printed in Oregon Territory. If you had a copy of that thin tome it would be worth quite a lot today. But you don’t, because shortly after the little books were printed they were destroyed.

In July, 1839, all the missionaries of Oregon Territory got together to discuss the book. They found Spalding’s attempt to create a Nez Perce alphabet and provide a means for translating the language could not “be relied on for books, or as a standard in any sense.”

The Reverend Asa Bowen Smith edited a new version of Spalding’s book, which would be called First Book: Designed For Children And New Beginners.” It was published in August, 1839.

The book the missionaries rejected and ordered destroyed, lived on in a way. In later years it was discovered that some pages of that earliest printing were used in the cover and binding of the new “first book.”

The printer Hall and his wife returned to the Sandwich Islands in May of 1840, leaving the press behind.

In 1842 or 43 the press was used to print a book for young readers in the Spokane language, a book of The Laws and Statutes, and a hymn book. Spalding labored for two years on a Nez Perce translation of the gospel of St. Matthew. It was printed in 1845. That year the last of the imprints from the Lapwai press appeared, a “vocabulary” of Nez Perce and English words. In 1846 the press was moved to The Dalles. It had a short history printing The Oregon and American Evangelical Unionist, and, years later, in 1875, was donated to the Oregon State Historical Society in Salem, where it resides today.

The Lapwai Press. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

The Lapwai Press. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

Published on June 13, 2022 04:00

June 12, 2022

Idaho Place Names that aren't what They Seem (tap to read)

It seems so obvious that since Lewiston, Idaho was named after Meriwether Lewis and Clarkston, Washington, just across the Snake River, was named for William Clark, and that Lewis County was named after Meriwether Lewis that Clark County must be named after William Clark. Obvious, but not true. Idaho’s Clark County is named for Sam K. Clark, an early settler who became the first state senator from the county.

It seems obvious, too, that Idaho’s Washington County, Washington Creek, Washington Lake, Washington Basin, and Washington Peak must all be named after the first American president, George Washington. In the case of Washington County, that is a correct assumption.

The rest of those Washingtons are in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area (SNRA) and they are named after another George Washington, George Washington Blackman. He was an African American prospector who came to the area in 1879 and stayed there for the rest of his life, which was reportedly near 100-years-long. (Blackman Peak, also in the SNRA, was also named after George Washington Blackman.) Granted, Blackman was probably named after the Father of Our Country, but those Idaho physical features were not.

There are many other “obvious” names that turn out not to be so obvious. Bliss, though no doubt blissful to some, was named after early settler David B. Bliss. Paris was not named for the home of the Eifel Tower, but for Frederick Perris who platted the townsite. It’s likely the name was changed by postal officials who had a habit of “correcting” applications that came their way.

Just one more for today. Did you think Monida Pass, which is in the aforementioned Clark County, was an Indian name with some colorful meaning? I’d never given it any thought, but it turns out this name probably should be obvious. It is a pass between the states of MONtana and IDAho.

It seems obvious, too, that Idaho’s Washington County, Washington Creek, Washington Lake, Washington Basin, and Washington Peak must all be named after the first American president, George Washington. In the case of Washington County, that is a correct assumption.

The rest of those Washingtons are in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area (SNRA) and they are named after another George Washington, George Washington Blackman. He was an African American prospector who came to the area in 1879 and stayed there for the rest of his life, which was reportedly near 100-years-long. (Blackman Peak, also in the SNRA, was also named after George Washington Blackman.) Granted, Blackman was probably named after the Father of Our Country, but those Idaho physical features were not.

There are many other “obvious” names that turn out not to be so obvious. Bliss, though no doubt blissful to some, was named after early settler David B. Bliss. Paris was not named for the home of the Eifel Tower, but for Frederick Perris who platted the townsite. It’s likely the name was changed by postal officials who had a habit of “correcting” applications that came their way.

Just one more for today. Did you think Monida Pass, which is in the aforementioned Clark County, was an Indian name with some colorful meaning? I’d never given it any thought, but it turns out this name probably should be obvious. It is a pass between the states of MONtana and IDAho.

Published on June 12, 2022 04:00

June 11, 2022

Hornikabrinka (tap to read)

Ah, what can one say about Hornikabrinka? Apparently, almost nothing. If you search for the word in The Idaho Statesman digital archives, you get several hits that talk about the 1913 revival of Hornikabrinka, which was to be held in conjunction with the semicentennial of the State of Idaho and the creation of Fort Boise that September. They were looking for “old-timers” who might be convinced to “reenact the stunts they used to do during the old time affairs.” What those stunts were is anyone’s guess.

There was a little spate of interest in Hornikabrinka in 1968 when a reader asked the Action Post columnist at the Statesman about it. They provided an answer that, though sketchy, set me on the right track. The columnist spelled it Hornikibrinki. The spelling of the event also included Horniki Brinki and Hornika Brinka in some references.

Speculation about exactly what it was, what it meant, and how it started seemed to be part of the fun. A headline from the August 1913 Idaho Statesman read “Hornika Brinika—What’s His Batting Average?” The reporter had walked around town asking people what the word or words meant to them. “Is it a drink, a germ, or a disease?”

During the 1913 celebration, it was billed as a revival of the tradition from around the founding of Boise. George Washington Stilts, a well-known practical joker in town during those earliest days, seemed to be one of the ringleaders of those celebrations. Which were exactly what?

Think Mardis Gras.

The September 27 Idaho Statesman had a full page about the festivities, headlined, “FROLIC OF THE FUNMAKERS—Mask Parade and Street Dance a Wild Revel of Pleasure.” The article began, “Herniki Briniki—symbol for expression of a wild, care free, abandoned, and yet not unduly boisterous variety of mirth that only that phrase will describe…” It continued “Fully 500 maskers took part in the parade, and such costumes! From the beautiful to the ridiculous, with the emphasis on the latter, they ranged, in a kaleidoscopic and seemingly endless variety.”

Then, showing the cultural sensitivity of the times it went on, “Every character commonly portrayed on the stage, from the pawnshop Jew and the plantation darkey, the heathen Chinee (sic) was there in half a dozen places.”

Moving on.

“At Sixth and Main streets a stop was made, and with the devil’s blacksmith shop as a backdrop and the red lights from The Statesman office lighting up the scene, the maskers staged the devil’s ball to the tune of that popular rag in a manner that would have set a grove of weeping willows to laughter.”

Now, there’s a metaphor you don’t often see.

When the parade was done, a dance commenced in front of the statehouse. “The capitol steps were black with humanity, and no space from which one could obtain a view of the dance space was vacant.”

All in all, good, clean fun. So, Boise kind of owns the name, however you spell it. It sounds way more entertaining than any parade I’ve ever seen in town. Someone should claim the name—however you want to spell it—and fest away. A rare pin from the Semicentennial Boise Hornikibrinika celebration.

A rare pin from the Semicentennial Boise Hornikibrinika celebration.

There was a little spate of interest in Hornikabrinka in 1968 when a reader asked the Action Post columnist at the Statesman about it. They provided an answer that, though sketchy, set me on the right track. The columnist spelled it Hornikibrinki. The spelling of the event also included Horniki Brinki and Hornika Brinka in some references.

Speculation about exactly what it was, what it meant, and how it started seemed to be part of the fun. A headline from the August 1913 Idaho Statesman read “Hornika Brinika—What’s His Batting Average?” The reporter had walked around town asking people what the word or words meant to them. “Is it a drink, a germ, or a disease?”

During the 1913 celebration, it was billed as a revival of the tradition from around the founding of Boise. George Washington Stilts, a well-known practical joker in town during those earliest days, seemed to be one of the ringleaders of those celebrations. Which were exactly what?

Think Mardis Gras.

The September 27 Idaho Statesman had a full page about the festivities, headlined, “FROLIC OF THE FUNMAKERS—Mask Parade and Street Dance a Wild Revel of Pleasure.” The article began, “Herniki Briniki—symbol for expression of a wild, care free, abandoned, and yet not unduly boisterous variety of mirth that only that phrase will describe…” It continued “Fully 500 maskers took part in the parade, and such costumes! From the beautiful to the ridiculous, with the emphasis on the latter, they ranged, in a kaleidoscopic and seemingly endless variety.”

Then, showing the cultural sensitivity of the times it went on, “Every character commonly portrayed on the stage, from the pawnshop Jew and the plantation darkey, the heathen Chinee (sic) was there in half a dozen places.”

Moving on.

“At Sixth and Main streets a stop was made, and with the devil’s blacksmith shop as a backdrop and the red lights from The Statesman office lighting up the scene, the maskers staged the devil’s ball to the tune of that popular rag in a manner that would have set a grove of weeping willows to laughter.”

Now, there’s a metaphor you don’t often see.

When the parade was done, a dance commenced in front of the statehouse. “The capitol steps were black with humanity, and no space from which one could obtain a view of the dance space was vacant.”

All in all, good, clean fun. So, Boise kind of owns the name, however you spell it. It sounds way more entertaining than any parade I’ve ever seen in town. Someone should claim the name—however you want to spell it—and fest away.

A rare pin from the Semicentennial Boise Hornikibrinika celebration.

A rare pin from the Semicentennial Boise Hornikibrinika celebration.

Published on June 11, 2022 04:00

June 10, 2022

A Boise School Ahead of its Time (tap to read)

When Amity School was built in southwest Boise, the design was ahead of its time. Only two other earth-sheltered schools were in existence in the US. And, if 50 years is the yardstick you use to measure what qualifies as a historical building—as many do—it is again ahead of its time. The Amity School is coming down this summer after 39 years of use.

When the Boise School District purchased 15 acres for a new elementary school in 1975, energy issues were on everyone’s mind. The Yom Kippur war had taken place two years earlier and Arab countries were embargoing oil to the United States in retaliation for our country’s assistance to Israel in that conflict. Oil prices quadrupled.

So the school district decided to build an energy efficient building. They needed voter approval, of course. Usually school bonds are set for a given amount of money, then the district designs to that amount and comes in at or under budget. Not this time. Voters knew exactly what they were voting on when they went to the polls to give the up or down on the Amity School Bond. The district had already called for designs and chosen the most expensive one, at $3.5 million. They sold the proposal to voters on the idea that this earth-sheltered school with solar panels providing hot water heat, would pay for itself in lower energy costs. They expected the extra construction costs to be paid back in 16 years, and the solar panels to pay for themselves in 11 years. The district was wrong. With ever-increasing energy costs, the payback time was about half that.

Most people thought of Amity School as that “underground” school. It wasn’t. The concrete outer walls were poured on site, above ground, and the inner walls were completed with concrete block. Then, they put pre-cast concrete beams across the whole thing to form a roof. Once all the concrete was in place, they pushed about two feet of dirt up onto the roof and angled it against the walls on all sides to provide added insulation. The plan was originally to let the kids spend recess on the roof, playing in the grass. Early drawings showed landscaping up there, but it never happened, perhaps because there was plenty of ground for recess around the school and perhaps because watering the roof would add extra cost and complication, potentially causing leaks. That is, more leaks than were destined to happen anyway.

Designers didn’t want the school to feel like a cave, so they designed it so that every classroom had a door to the outside and one good-sized window. Offices, the lunchroom, restrooms, the gym, and the library were in the center of the structure and without natural light, but every room was painted in light, bright colors to compensate.

When the school came on line in 1979, its innovative design made Time Magazine. That first year the energy costs of the school were 72-74 percent lower than other schools in the district of similar size.

Amity School could handle 788 kids from kindergarten to sixth grade in 26 classrooms. Thousands of Boise kids grew up as “Groundhogs” (the school mascot was Solar Sam).

But, everything has a lifespan, and Amity School reached the end of its days in 2018, replaced by a new school built right next door.

Why tear down an innovative building? Leaks, mostly. That sod and concrete roof never could keep water out. But the district has learned a lot from the school. Several other schools in Boise use earth sheltered walls (not roofs) and other innovative features first tried out at Amity.

By the way, the first Amity School was in what was then the Meridian School District. It was built in 1919 to serve students a few miles west of the current school. The original Amity School was named such (probably) because the word means friendship and goodwill. They built a road to the school, which became Amity Road. The original school was converted to a private residence in the early 1950s, but was recently torn down. The name still stuck for the road, though, which then got attached to the earth-sheltered school, built in 1978, and first occupied in 1979.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

When the Boise School District purchased 15 acres for a new elementary school in 1975, energy issues were on everyone’s mind. The Yom Kippur war had taken place two years earlier and Arab countries were embargoing oil to the United States in retaliation for our country’s assistance to Israel in that conflict. Oil prices quadrupled.

So the school district decided to build an energy efficient building. They needed voter approval, of course. Usually school bonds are set for a given amount of money, then the district designs to that amount and comes in at or under budget. Not this time. Voters knew exactly what they were voting on when they went to the polls to give the up or down on the Amity School Bond. The district had already called for designs and chosen the most expensive one, at $3.5 million. They sold the proposal to voters on the idea that this earth-sheltered school with solar panels providing hot water heat, would pay for itself in lower energy costs. They expected the extra construction costs to be paid back in 16 years, and the solar panels to pay for themselves in 11 years. The district was wrong. With ever-increasing energy costs, the payback time was about half that.

Most people thought of Amity School as that “underground” school. It wasn’t. The concrete outer walls were poured on site, above ground, and the inner walls were completed with concrete block. Then, they put pre-cast concrete beams across the whole thing to form a roof. Once all the concrete was in place, they pushed about two feet of dirt up onto the roof and angled it against the walls on all sides to provide added insulation. The plan was originally to let the kids spend recess on the roof, playing in the grass. Early drawings showed landscaping up there, but it never happened, perhaps because there was plenty of ground for recess around the school and perhaps because watering the roof would add extra cost and complication, potentially causing leaks. That is, more leaks than were destined to happen anyway.

Designers didn’t want the school to feel like a cave, so they designed it so that every classroom had a door to the outside and one good-sized window. Offices, the lunchroom, restrooms, the gym, and the library were in the center of the structure and without natural light, but every room was painted in light, bright colors to compensate.

When the school came on line in 1979, its innovative design made Time Magazine. That first year the energy costs of the school were 72-74 percent lower than other schools in the district of similar size.

Amity School could handle 788 kids from kindergarten to sixth grade in 26 classrooms. Thousands of Boise kids grew up as “Groundhogs” (the school mascot was Solar Sam).

But, everything has a lifespan, and Amity School reached the end of its days in 2018, replaced by a new school built right next door.

Why tear down an innovative building? Leaks, mostly. That sod and concrete roof never could keep water out. But the district has learned a lot from the school. Several other schools in Boise use earth sheltered walls (not roofs) and other innovative features first tried out at Amity.

By the way, the first Amity School was in what was then the Meridian School District. It was built in 1919 to serve students a few miles west of the current school. The original Amity School was named such (probably) because the word means friendship and goodwill. They built a road to the school, which became Amity Road. The original school was converted to a private residence in the early 1950s, but was recently torn down. The name still stuck for the road, though, which then got attached to the earth-sheltered school, built in 1978, and first occupied in 1979.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym. You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors. The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about. The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

Published on June 10, 2022 04:00