Rick Just's Blog, page 96

May 10, 2022

Another Bigfoot Story (Tap to Read)

I’ll probably put my foot in it on this one. My average-sized foot.

Bigfoot was a legendary Indian. He was known for the enormous tracks he left. Those tracks were alleged to be 17 ½” long, large even for a man 6’ 6” tall. Allegedly.

Bigfoot’s tracks were said to have been seen often at the site of depredations perpetrated by indigenous people on immigrants, especially in Idaho and Oregon. He was always one step ahead of anyone trying to catch him. Stepping was part of the legend. He always walked or ran rather than ride a horse, the better to leave moccasin tracks, not doubt.

In November of 1878, the Idaho Statesman ran a sensational story about the death of Bigfoot, written by William T. Anderson of Fisherman’s Cove, Humboldt County, California, who had heard it from the man who killed him. It detailed the 16 bullets that went into Bigfoot’s body, fired by one John Wheeler, who caught up with him in Owyhee County. Both of the big man’s arms and both of his legs were broken by bullets in the fight with Wheeler. Knowing he was at death’s door, Bigfoot decided to tell Wheeler his life story. He did so in prose that Dick d’Easum who wrote about it years later for the Idaho Statesman said was packed with enough “frothy facts of his boyhood and manhood to fill a Theodore Dreiser novel.”

In the Anderson account of the death of Bigfoot, the man had an actual name. He was Starr Wilkinson, who was a lad living in the Cherokee nation when his father, a white man, was hanged for murder. His mother was of mixed blood, Negro and Cherokee. The drama of Bigfoot’s life went on for thousands of words, many of which were quite eloquent for a man gurgling them out with 16 bullet wounds in his body.

Odd that Wheeler himself never said anything about killing one of the most notorious bad men in the West. Odd that he didn’t collect the $1,000 reward on the man’s head. Wheeler had an outlaw record to his own credit. He killed a man on Wood River in 1868, and got away with it. He was sentenced to ten years in prison for a stagecoach robbery in Oregon. After leaving prison, he was eventually sentenced to hang for a murder committed during another stage robbery, this time in California.

Awaiting certain death, Wheeler wrote a series of letters to his wife, his sister, his attorney, and a girlfriend reflecting on his life. He wrote not a word about Bigfoot. His musings complete, Wheeler took poison in jail rather than face the rope, and died.

Many historians discount the whole legend of Bigfoot. Dick d’Easum put it this way: “Just as nobody is ever attacked by a little bear, no pioneer of the 1860s ever lost a steer or a wife or a set of harness to a small Indian. Little Indians were sometimes caught and killed. Dead Indians had little feet. Indians that prowled and pillaged and slipped away unscathed were invariably possessed of huge trotters.”

So, if Bigfoot was a myth, why would you name a town after him? That town is Nampa, reportedly taking its name from Shoshoni words Namp (foot) and Puh (big), and by some reports named after the legendary Bigfoot. Historian Annie Laurie Bird did research on the name Nampa in 1966, concluding that it probably did come from a Shoshoni word pronounced “nambe” or “nambuh” and meaning footprint. She did not weigh in on the Bigfoot connection.

A marauding giant is such a good story that it may never die. It was good enough that Bigfoot was killed, again, in New Mexico, 14 years after he was ventilated in Owyhee County. No word on whether he was able to gasp out his life story that time.

Bigfoot was a legendary Indian. He was known for the enormous tracks he left. Those tracks were alleged to be 17 ½” long, large even for a man 6’ 6” tall. Allegedly.

Bigfoot’s tracks were said to have been seen often at the site of depredations perpetrated by indigenous people on immigrants, especially in Idaho and Oregon. He was always one step ahead of anyone trying to catch him. Stepping was part of the legend. He always walked or ran rather than ride a horse, the better to leave moccasin tracks, not doubt.

In November of 1878, the Idaho Statesman ran a sensational story about the death of Bigfoot, written by William T. Anderson of Fisherman’s Cove, Humboldt County, California, who had heard it from the man who killed him. It detailed the 16 bullets that went into Bigfoot’s body, fired by one John Wheeler, who caught up with him in Owyhee County. Both of the big man’s arms and both of his legs were broken by bullets in the fight with Wheeler. Knowing he was at death’s door, Bigfoot decided to tell Wheeler his life story. He did so in prose that Dick d’Easum who wrote about it years later for the Idaho Statesman said was packed with enough “frothy facts of his boyhood and manhood to fill a Theodore Dreiser novel.”

In the Anderson account of the death of Bigfoot, the man had an actual name. He was Starr Wilkinson, who was a lad living in the Cherokee nation when his father, a white man, was hanged for murder. His mother was of mixed blood, Negro and Cherokee. The drama of Bigfoot’s life went on for thousands of words, many of which were quite eloquent for a man gurgling them out with 16 bullet wounds in his body.

Odd that Wheeler himself never said anything about killing one of the most notorious bad men in the West. Odd that he didn’t collect the $1,000 reward on the man’s head. Wheeler had an outlaw record to his own credit. He killed a man on Wood River in 1868, and got away with it. He was sentenced to ten years in prison for a stagecoach robbery in Oregon. After leaving prison, he was eventually sentenced to hang for a murder committed during another stage robbery, this time in California.

Awaiting certain death, Wheeler wrote a series of letters to his wife, his sister, his attorney, and a girlfriend reflecting on his life. He wrote not a word about Bigfoot. His musings complete, Wheeler took poison in jail rather than face the rope, and died.

Many historians discount the whole legend of Bigfoot. Dick d’Easum put it this way: “Just as nobody is ever attacked by a little bear, no pioneer of the 1860s ever lost a steer or a wife or a set of harness to a small Indian. Little Indians were sometimes caught and killed. Dead Indians had little feet. Indians that prowled and pillaged and slipped away unscathed were invariably possessed of huge trotters.”

So, if Bigfoot was a myth, why would you name a town after him? That town is Nampa, reportedly taking its name from Shoshoni words Namp (foot) and Puh (big), and by some reports named after the legendary Bigfoot. Historian Annie Laurie Bird did research on the name Nampa in 1966, concluding that it probably did come from a Shoshoni word pronounced “nambe” or “nambuh” and meaning footprint. She did not weigh in on the Bigfoot connection.

A marauding giant is such a good story that it may never die. It was good enough that Bigfoot was killed, again, in New Mexico, 14 years after he was ventilated in Owyhee County. No word on whether he was able to gasp out his life story that time.

Published on May 10, 2022 04:00

May 9, 2022

Valentine Wrote About Idaho (Tap to Read)

So, here’s a guy (me) who writes quirky little stories about Idaho history, writing about a guy who wrote quirky little stories about Idaho history. This post may eat its own tail.

Dan Valentine wasn’t from Idaho, and he didn’t live here. Still, he was a purveyor of Idaho history, not in a scholarly sense, but in a storytelling sense. Valentine was a columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 30 years, retiring in 1980. In the 1950s and 60s, that paper was widely read in Southeastern Idaho. Enough so that Valentine included many humorous observations about the state.

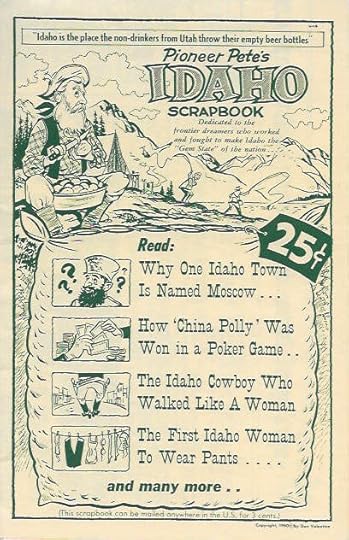

Valentine published several books that grew out of his columns. They were often sold in restaurants and truck stops across Idaho and Utah. I ran across one of his publications recently while going through some family memorabilia. It’s a four-page newsletter quarter-folded into a book-sized pamphlet, called Pioneer Pete’s IDAHO Scrapbook, dated 1960. The amount of information he was able to squeeze in there is jaw-dropping. It included the story of Peg Leg Annie, a piece about Little Joe Monaghan, stories about Lana Turner, Polly Bemis, Ernest Hemingway, Diamondfield Jack, the lone parking meter in Murphy, and a dozen more. A better understanding of history has since put several of the stories into the apocryphal category, but at that time they were widely believed to be true.

Valentine’s material was featured on the Johnny Carson Show, as well as programs hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Garry Moore, and Art Linkletter.

A taste from the pamphlet:

Cats were allegedly worth $10 each in Idaho City once, because of a mouse problem.

Boise (at that time) was said to boast the only wooden cigar store Indian factory in the world.

If the state of Idaho was flattened out it would be larger than Texas.

Valentine was once accused of being a bit chauvinistic in his columns, but he’s also the guy who once said "I don't know why women would want to give up complete superiority for mere equality."

Dan Valentine passed away in 1991 at age 73.

Dan Valentine wasn’t from Idaho, and he didn’t live here. Still, he was a purveyor of Idaho history, not in a scholarly sense, but in a storytelling sense. Valentine was a columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 30 years, retiring in 1980. In the 1950s and 60s, that paper was widely read in Southeastern Idaho. Enough so that Valentine included many humorous observations about the state.

Valentine published several books that grew out of his columns. They were often sold in restaurants and truck stops across Idaho and Utah. I ran across one of his publications recently while going through some family memorabilia. It’s a four-page newsletter quarter-folded into a book-sized pamphlet, called Pioneer Pete’s IDAHO Scrapbook, dated 1960. The amount of information he was able to squeeze in there is jaw-dropping. It included the story of Peg Leg Annie, a piece about Little Joe Monaghan, stories about Lana Turner, Polly Bemis, Ernest Hemingway, Diamondfield Jack, the lone parking meter in Murphy, and a dozen more. A better understanding of history has since put several of the stories into the apocryphal category, but at that time they were widely believed to be true.

Valentine’s material was featured on the Johnny Carson Show, as well as programs hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Garry Moore, and Art Linkletter.

A taste from the pamphlet:

Cats were allegedly worth $10 each in Idaho City once, because of a mouse problem.

Boise (at that time) was said to boast the only wooden cigar store Indian factory in the world.

If the state of Idaho was flattened out it would be larger than Texas.

Valentine was once accused of being a bit chauvinistic in his columns, but he’s also the guy who once said "I don't know why women would want to give up complete superiority for mere equality."

Dan Valentine passed away in 1991 at age 73.

Published on May 09, 2022 04:00

May 8, 2022

Tolo Lake (Tap to Read)

Tolo Lake, near Grangeville, was in the news in the fall of 1994 when the Idaho Department of Fish and Game was deepening the drained lake to provide for better fishing. Fish and Game was hoping to take out a dozen feet of silt so that it could better support fish and waterfowl. What they found during the excavation was neither fish nor fowl. It was something much, much larger.

Tolo Lake, which is about 36 acres, was a rendezvous point for the Nez Perce, or nimí·pu, for many years, including at the start of what became the Nez Perce War. Digging there could help wildlife, sure, but it could also shed light on the Tribe’s history. But when the first bone was exposed it was clearly not an artifact of the Nez Perce occupation of the site. It was a leg bone 4 ½ feet tall. Its discovery quickly piqued the interest of archeologists, so scientists from the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho State Historical Society, University of Idaho, and the Idaho Natural History Museum descended on the site where it was quickly determined that these were the bones of mammoths.

Mammoths were not called that for nothing. They weighed 10-15,000 pounds and stood about 14 feet at the shoulder. They were alive in North America as recently as 4,500 to 12,500 years ago, meaning they may have been familiar to the first people on the continent.

The dig exposed the bones of three mammoths and an ancient bison skull. The longest tusk discovered was measured at 16 feet. One of the tusks is on display at the Bicentennial Museum in Grangeville. The town also boasts a mammoth skeleton replica in an interpretive exhibit next to the Grangeville Chamber of Commerce office.

Tolo Lake, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, was named for a Nez Perce woman who alerted settlers of the rampage that started the Nez Perce War.

Tolo Lake, which is about 36 acres, was a rendezvous point for the Nez Perce, or nimí·pu, for many years, including at the start of what became the Nez Perce War. Digging there could help wildlife, sure, but it could also shed light on the Tribe’s history. But when the first bone was exposed it was clearly not an artifact of the Nez Perce occupation of the site. It was a leg bone 4 ½ feet tall. Its discovery quickly piqued the interest of archeologists, so scientists from the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho State Historical Society, University of Idaho, and the Idaho Natural History Museum descended on the site where it was quickly determined that these were the bones of mammoths.

Mammoths were not called that for nothing. They weighed 10-15,000 pounds and stood about 14 feet at the shoulder. They were alive in North America as recently as 4,500 to 12,500 years ago, meaning they may have been familiar to the first people on the continent.

The dig exposed the bones of three mammoths and an ancient bison skull. The longest tusk discovered was measured at 16 feet. One of the tusks is on display at the Bicentennial Museum in Grangeville. The town also boasts a mammoth skeleton replica in an interpretive exhibit next to the Grangeville Chamber of Commerce office.

Tolo Lake, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, was named for a Nez Perce woman who alerted settlers of the rampage that started the Nez Perce War.

Published on May 08, 2022 04:00

May 7, 2022

Women Writers From Idaho (Tap to Read)

There are many exceptional woman writers who are connected to Idaho. Here are some who are native to the state.

Carol Ryrie Brink, who wrote more than 30 juvenile and adult books, including the 1936 Newbury Prize-winning Caddie Woodlawn . Brink was born in Moscow and attended the University of Idaho. She was awarded an honorary doctorate of letters from U of I in 1965, and Brink Hall on the campus is named for her.

Marilynn Robinson, who won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her book Gilead in 2005 was born in Sandpoint. Her book Housekeeping , which is set in Sandpoint, was a Pulitzer finalist in 1982.

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich was born in Sugar City, Idaho. Her history of midwife Martha Ballard, titled The Midwife’s Tale , won a Pulitzer Prize and was later made into a documentary film for the PBS series American Experience. Oddly, she may enjoy more fame for a single line in a scholarly publication than for her prize-winning work. She is remembered for the line, "well-behaved women seldom make history," which came from an article about Puritan funeral services. She would later write a book with that title.

Tara Westover was born in Clifton, Idaho. Her 2018 memoir Educated was on many best book lists, including the New York Time top ten list for the year.

Sarah Palin sold more than two million copies of her book Going Rogue . The former governor of Alaska and vice-presidential candidate was born in Sandpoint. She received her bachelor’s degree in communication with a journalism emphasis from the University of Idaho in 1987.

Emily Ruskovich grew up in the panhandle of Idaho on Hoo Doo Mountain. She now teaches at Boise State University. Her 2017 novel, Idaho , was critically acclaimed.

Elaine Ambrose grew up on a potato farm near Wendell. She is best known for her eight books of humor and recently released a memoir called Frozen Dinners, A Memoir of a Fractured Family .

Sister Mary Alfreda Elsensohn (1897-1989) was born in Grangeville, Idaho and she was professed as a Benedictine sister at the Monastery of St. Gertrude in 1916. She was educated at Washington State University, Gonzaga University, and University of Idaho. Her best-known book is Polly Bemis: Idaho County’s Most Romantic Character . Sister Elsensohn created the museum at St. Gertrudes near Cottonwood. The Idaho Humanaties Council and the Idaho State Historical Society give an annual award in her name for Idaho museums.

Jacquie Rogers, born on a farm near Homedale, writes Western humor and Western romance, for which she has won several prizes. Go to any of her books on Amazon, such as Sidetracked in Silver City , and click on her name for a complete list. Idahoan Carol Ryrie Brink received a Newberry Award for her book Caddie Woodlawn.

Idahoan Carol Ryrie Brink received a Newberry Award for her book Caddie Woodlawn.

Carol Ryrie Brink, who wrote more than 30 juvenile and adult books, including the 1936 Newbury Prize-winning Caddie Woodlawn . Brink was born in Moscow and attended the University of Idaho. She was awarded an honorary doctorate of letters from U of I in 1965, and Brink Hall on the campus is named for her.

Marilynn Robinson, who won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her book Gilead in 2005 was born in Sandpoint. Her book Housekeeping , which is set in Sandpoint, was a Pulitzer finalist in 1982.

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich was born in Sugar City, Idaho. Her history of midwife Martha Ballard, titled The Midwife’s Tale , won a Pulitzer Prize and was later made into a documentary film for the PBS series American Experience. Oddly, she may enjoy more fame for a single line in a scholarly publication than for her prize-winning work. She is remembered for the line, "well-behaved women seldom make history," which came from an article about Puritan funeral services. She would later write a book with that title.

Tara Westover was born in Clifton, Idaho. Her 2018 memoir Educated was on many best book lists, including the New York Time top ten list for the year.

Sarah Palin sold more than two million copies of her book Going Rogue . The former governor of Alaska and vice-presidential candidate was born in Sandpoint. She received her bachelor’s degree in communication with a journalism emphasis from the University of Idaho in 1987.

Emily Ruskovich grew up in the panhandle of Idaho on Hoo Doo Mountain. She now teaches at Boise State University. Her 2017 novel, Idaho , was critically acclaimed.

Elaine Ambrose grew up on a potato farm near Wendell. She is best known for her eight books of humor and recently released a memoir called Frozen Dinners, A Memoir of a Fractured Family .

Sister Mary Alfreda Elsensohn (1897-1989) was born in Grangeville, Idaho and she was professed as a Benedictine sister at the Monastery of St. Gertrude in 1916. She was educated at Washington State University, Gonzaga University, and University of Idaho. Her best-known book is Polly Bemis: Idaho County’s Most Romantic Character . Sister Elsensohn created the museum at St. Gertrudes near Cottonwood. The Idaho Humanaties Council and the Idaho State Historical Society give an annual award in her name for Idaho museums.

Jacquie Rogers, born on a farm near Homedale, writes Western humor and Western romance, for which she has won several prizes. Go to any of her books on Amazon, such as Sidetracked in Silver City , and click on her name for a complete list.

Idahoan Carol Ryrie Brink received a Newberry Award for her book Caddie Woodlawn.

Idahoan Carol Ryrie Brink received a Newberry Award for her book Caddie Woodlawn.

Published on May 07, 2022 04:00

May 6, 2022

My Private Idaho (Tap to read)

We all have our own Idaho. I wrote about that a few years back in my novel,

Keeping Private Idaho

. Today—forgive my indulgence—I’m going to introduce you to mine.

Along about 1956 my father, who we called Pop, noticed that the configuration of ditches near the house on our family ranch outside of Blackfoot made three sides of a rectangle. I still remember him scraping up dirt with a squat little Ford tractor, pushing it up into what would become a dike along that fourth side.

Pop’s father and grandfather had built a major part of the canal system in Eastern Idaho, so he knew a little bit about making water do what he wanted it to. Usually that meant setting canvas dams in ditches and scraping off the high spots so that a field of alfalfa could get water. But while he was tromping around in waders with a shovel, pointing the way for water, he was thinking about his all-time favorite activity: fishing.

When pop diverted the water into what now had dikes on four sides, we saw his vision come to life. He had created a fish pond, about an acre in size. My brothers and I watched as the tankers came from Springfield with loads of rainbow trout, dumping them into the pond, which had quickly acquired moss, and bugs, and frogs.

Pop called his big idea Chick Just’s Trout Ranch. He had orange signs made that he could tack up on fence posts so people could find their way to the ranch. He charged by the pound for fish they caught. No charge if you didn’t catch anything. But they always caught fish. That was his joy. He liked nothing better than to see a kid catch her first trout.

So, paradise for me. I didn’t care much about fishing, but I cared for nothing more than I cared for that pond. It was my world; one which I could pole across in a skiff pretending I was Huck Finn, and swim in trying not to drown. I caught a million tadpoles and watched them turn into frogs, and chased dragonflies that were enemy helicopters.

That pond was the center of my life growing up. It must have occupied 50 years of my childhood. Yet, when I do the math now, I’m stunned by it. Pop died in 1960. We moved into town in 1961. Five years, not 50.

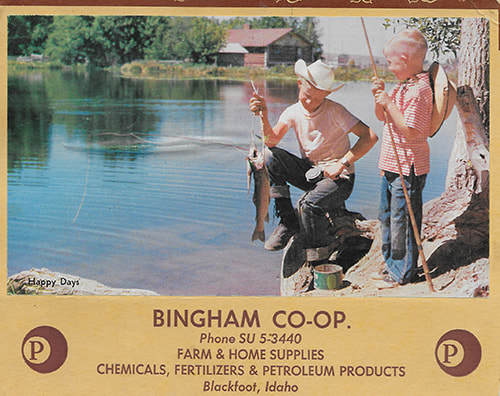

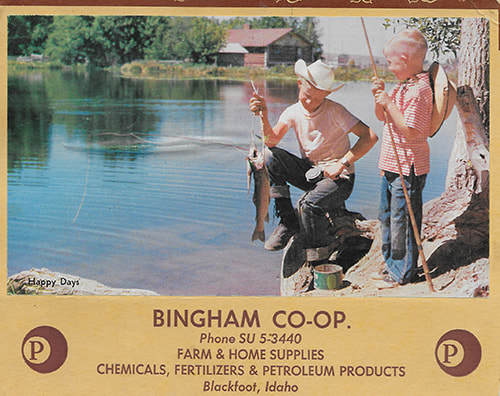

It was so idyllic for a kid you’d think I was making it up. But I have a picture. This one appeared on calendars and in magazines promoting Idaho for three or four years. It’s of me, the cute one, with my older brother, Kent. In the background, you can just make out our log house across the pond. My private Idaho. What does yours look like?

Along about 1956 my father, who we called Pop, noticed that the configuration of ditches near the house on our family ranch outside of Blackfoot made three sides of a rectangle. I still remember him scraping up dirt with a squat little Ford tractor, pushing it up into what would become a dike along that fourth side.

Pop’s father and grandfather had built a major part of the canal system in Eastern Idaho, so he knew a little bit about making water do what he wanted it to. Usually that meant setting canvas dams in ditches and scraping off the high spots so that a field of alfalfa could get water. But while he was tromping around in waders with a shovel, pointing the way for water, he was thinking about his all-time favorite activity: fishing.

When pop diverted the water into what now had dikes on four sides, we saw his vision come to life. He had created a fish pond, about an acre in size. My brothers and I watched as the tankers came from Springfield with loads of rainbow trout, dumping them into the pond, which had quickly acquired moss, and bugs, and frogs.

Pop called his big idea Chick Just’s Trout Ranch. He had orange signs made that he could tack up on fence posts so people could find their way to the ranch. He charged by the pound for fish they caught. No charge if you didn’t catch anything. But they always caught fish. That was his joy. He liked nothing better than to see a kid catch her first trout.

So, paradise for me. I didn’t care much about fishing, but I cared for nothing more than I cared for that pond. It was my world; one which I could pole across in a skiff pretending I was Huck Finn, and swim in trying not to drown. I caught a million tadpoles and watched them turn into frogs, and chased dragonflies that were enemy helicopters.

That pond was the center of my life growing up. It must have occupied 50 years of my childhood. Yet, when I do the math now, I’m stunned by it. Pop died in 1960. We moved into town in 1961. Five years, not 50.

It was so idyllic for a kid you’d think I was making it up. But I have a picture. This one appeared on calendars and in magazines promoting Idaho for three or four years. It’s of me, the cute one, with my older brother, Kent. In the background, you can just make out our log house across the pond. My private Idaho. What does yours look like?

Published on May 06, 2022 04:00

May 5, 2022

Idaho's Weird Shark (Tap to read)

Why don’t we have a state shark? Just asking. We have a state amphibian, a state bird, a state fish, a state flower, a state fruit, a state gem, a state horse, a state insect, a state raptor, a state tree, and a state vegetable (any guesses?). But, sadly, no state shark. Now, the picky readers out there will point out that to have a state shark, we’d have to have a shark in the state. Ha! I have you there.

True, it’s a fossil shark, but there’s precedent for that. Idaho has a state fossil, the Hagerman Horse. The shark I’m talking about is Helicoprion, which once swam the oceans over what is now Soda Springs. “Once” was about 250 million years ago.

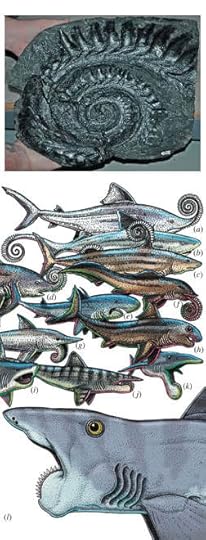

I’ve seen the famous fossils. Every time I’ve looked at them they puzzled me. I’m not alone. They puzzle scientists, too. Sharks don’t fossilize well because their skeletons are made of cartilage. Shark teeth, on the other hand, can hang around for millennia. So it is with the Helicoprion. All we have to prove that it once existed are teeth. But those teeth are so weird. They make up a spiral with small teeth in the center growing geometrically until those on the outer edge become large (picture, top).

With just those buzz-saw teeth to work from, scientists have speculated for years on what the shark would have looked like. Were the teeth in the front of its mouth? In the back? Were they down its throat somehow?

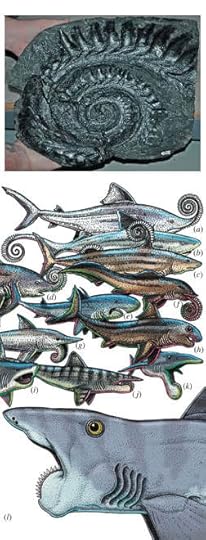

In 2013 an international team of paleontologists, including Professor Leif Tapanila of the Idaho Museum of Natural History and Idaho State University published a paper about the shark in the journal Biology Letters, describing a rare fossil specimen that contained enough cartilage to give scientists a better idea of the creature’s jaw configuration. The image, from that publication, shows several previous depictions above the larger version that their findings describe.

Cute, huh? Even if you’d pass on the state shark idea, think of the mascot possibilities! Soda Springs Cardinals, have you thought of this?

True, it’s a fossil shark, but there’s precedent for that. Idaho has a state fossil, the Hagerman Horse. The shark I’m talking about is Helicoprion, which once swam the oceans over what is now Soda Springs. “Once” was about 250 million years ago.

I’ve seen the famous fossils. Every time I’ve looked at them they puzzled me. I’m not alone. They puzzle scientists, too. Sharks don’t fossilize well because their skeletons are made of cartilage. Shark teeth, on the other hand, can hang around for millennia. So it is with the Helicoprion. All we have to prove that it once existed are teeth. But those teeth are so weird. They make up a spiral with small teeth in the center growing geometrically until those on the outer edge become large (picture, top).

With just those buzz-saw teeth to work from, scientists have speculated for years on what the shark would have looked like. Were the teeth in the front of its mouth? In the back? Were they down its throat somehow?

In 2013 an international team of paleontologists, including Professor Leif Tapanila of the Idaho Museum of Natural History and Idaho State University published a paper about the shark in the journal Biology Letters, describing a rare fossil specimen that contained enough cartilage to give scientists a better idea of the creature’s jaw configuration. The image, from that publication, shows several previous depictions above the larger version that their findings describe.

Cute, huh? Even if you’d pass on the state shark idea, think of the mascot possibilities! Soda Springs Cardinals, have you thought of this?

Published on May 05, 2022 04:00

May 4, 2022

A Deadly Explorer (Tap to read)

The Corps of Discovery, also known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, travelled through a wilderness making new discoveries, naming plants and animals and mountains and rivers for the first time, and inspiring awe in the primitive people who barely subsisted there. Right?

Well, it was all new to them, but people had operated successful societies in that “unexplored” country for thousands of years. Those plants and animals and mountains and rivers already had names. The people who lived there were interested in the innovations the Corps of Discovery brought with them from pants with pockets to pistols and ammunition. But they probably thought the white men (and one black man) were woefully ignorant when they went hungry with food so easily attainable nearby.

Wilderness? The natives had no such concept. This was no unoccupied frontier. The Mandan villages in what is now North Dakota where the Corps spent the winter of 1804-1805 were more densely populated than St. Louis, according to an essay by Roberta Conner in the 2006 anthology Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes. The Expedition itself estimated there were 114 tribes living along or near their route.

What they did not report, because they did not know it, was that one newcomer from the Old World had preceded them, devastating the Indian population. According to Charles C. Mann in his book 1491, New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, smallpox took out as much as 90 percent of the native population in the Americas. Mark Trahant, a writer with Indian ancestry from Blackfoot, noted in the above-mentioned anthology that a smallpox epidemic swept through Shoshone country around 1780.

Lewis and Clark encountered a considerable civilization on their journey, though one much reduced from what it had been a few generations before.

If you would like to learn more about how the indigenous people of the Americas lived and the impact epidemic had on them, I recommend the books previously mentioned and Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond.

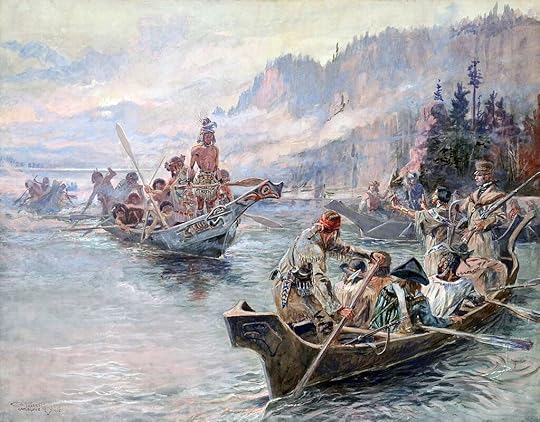

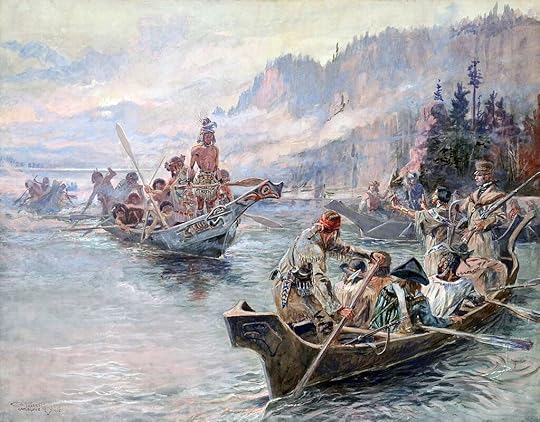

A depiction of the Lewis and Clark Expedition meeting with natives, by Charles M. Russell.

A depiction of the Lewis and Clark Expedition meeting with natives, by Charles M. Russell.

Well, it was all new to them, but people had operated successful societies in that “unexplored” country for thousands of years. Those plants and animals and mountains and rivers already had names. The people who lived there were interested in the innovations the Corps of Discovery brought with them from pants with pockets to pistols and ammunition. But they probably thought the white men (and one black man) were woefully ignorant when they went hungry with food so easily attainable nearby.

Wilderness? The natives had no such concept. This was no unoccupied frontier. The Mandan villages in what is now North Dakota where the Corps spent the winter of 1804-1805 were more densely populated than St. Louis, according to an essay by Roberta Conner in the 2006 anthology Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes. The Expedition itself estimated there were 114 tribes living along or near their route.

What they did not report, because they did not know it, was that one newcomer from the Old World had preceded them, devastating the Indian population. According to Charles C. Mann in his book 1491, New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, smallpox took out as much as 90 percent of the native population in the Americas. Mark Trahant, a writer with Indian ancestry from Blackfoot, noted in the above-mentioned anthology that a smallpox epidemic swept through Shoshone country around 1780.

Lewis and Clark encountered a considerable civilization on their journey, though one much reduced from what it had been a few generations before.

If you would like to learn more about how the indigenous people of the Americas lived and the impact epidemic had on them, I recommend the books previously mentioned and Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond.

A depiction of the Lewis and Clark Expedition meeting with natives, by Charles M. Russell.

A depiction of the Lewis and Clark Expedition meeting with natives, by Charles M. Russell.

Published on May 04, 2022 04:00

May 3, 2022

The Spiral Highway (Tap to read)

The Lewiston Hill road is an engineering marvel. Today it’s a four-lane, divided highway that allows drivers to zip up and down the road at 65 mph, hardly noticing the hill at all, unless you’re driving a truck. That wasn’t the case in 1915.

The Lewiston Spiral Highway was a huge project for the Idaho State Highway Commission in 1915 and 1916. It sucked up so much of the highway fund other parts of the state complained bitterly. But what a project. The road was to start in the valley at 725 feet above sea level, and top the hill above the city at 2,750 feet. That’s less than half a mile, as the crow flies, but Model T’s did not fly. The twisting road would run ten miles forth and back, and back and forth, testing many radiators in the climb.

An article in the September 27, 1916 edition of the Lewiston Morning Tribune reported that “Within just two and six tenths miles of the goal—which is the summit of Lewiston Hill—the big Marion Caterpillar steam shovel is still trembling with willing energy, still digging, still climbing, still creeping out of the valley over its own triumphant trail—a trail destined in time to become one of the noted scenic highways of the west.”

The Spiral Highway, sometimes called Uniontown Hill Road, cost the state and the Lewiston highway district $141,587. Oh, and 42 cents.

There was much demand for the new highway. According to a story in the January 12, 1918, edition of the Idaho Statesman “an actual count made by a man stationed at the Eighteenth street bridge” recorded 1280 cars climbing the hill on a single November day. The same article noted that you could see the Blue Mountains in Oregon to the southwest from the top of the hill.

Safety was a big concern. The Statesman article put everyone’s fears to rest. “The right-of-way has been fenced on both sides for the entire distance. Guarding railings, made of frame material with heavy posts were constructed at exposed points on the grade. Barbed wire was used for the balance of the distance. Both the guarding fencing and the wire are set in far enough on the highway to serve as a guide to autoists going over the road on the darkest nights.”

Oh, blessed barbed wire guiding our nighttime autoists!

The Lewiston Spiral Highway was a huge project for the Idaho State Highway Commission in 1915 and 1916. It sucked up so much of the highway fund other parts of the state complained bitterly. But what a project. The road was to start in the valley at 725 feet above sea level, and top the hill above the city at 2,750 feet. That’s less than half a mile, as the crow flies, but Model T’s did not fly. The twisting road would run ten miles forth and back, and back and forth, testing many radiators in the climb.

An article in the September 27, 1916 edition of the Lewiston Morning Tribune reported that “Within just two and six tenths miles of the goal—which is the summit of Lewiston Hill—the big Marion Caterpillar steam shovel is still trembling with willing energy, still digging, still climbing, still creeping out of the valley over its own triumphant trail—a trail destined in time to become one of the noted scenic highways of the west.”

The Spiral Highway, sometimes called Uniontown Hill Road, cost the state and the Lewiston highway district $141,587. Oh, and 42 cents.

There was much demand for the new highway. According to a story in the January 12, 1918, edition of the Idaho Statesman “an actual count made by a man stationed at the Eighteenth street bridge” recorded 1280 cars climbing the hill on a single November day. The same article noted that you could see the Blue Mountains in Oregon to the southwest from the top of the hill.

Safety was a big concern. The Statesman article put everyone’s fears to rest. “The right-of-way has been fenced on both sides for the entire distance. Guarding railings, made of frame material with heavy posts were constructed at exposed points on the grade. Barbed wire was used for the balance of the distance. Both the guarding fencing and the wire are set in far enough on the highway to serve as a guide to autoists going over the road on the darkest nights.”

Oh, blessed barbed wire guiding our nighttime autoists!

Published on May 03, 2022 04:00

May 2, 2022

The 50th Anniversary of Idaho's Worst Mining Disaster (Tap to read)

Just off Interstate 90, near the Big Creek exit, stands a 12-foot high steel statue of a miner at work (photo). A dim lamp glows on the miner's hard hat, in memory of Idaho's worst mine disaster.

At about noon on May 2nd, 1972 miners noticed smoke inside the Sunshine Silver Mine near Kellogg. The mine is a labyrinth of tunnels and shafts a mile deep and more. It was almost impossible to tell just where the smoke was coming from.

One hundred seventy-three men were in the mine on that fateful day. At the first hint of smoke they began to evacuate.

There are tales of bravery and tragedy too lengthy to recount. A hoistman ran his elevator-like hoist, lifting men through the toxic smoke to safety--until he died at the controls. One rescuer gave up his oxygen mask to an escaping miner, and in turn gave up his life. Heroism was the rule of the day with so many lives at stake.

Rescue efforts went on for a week, with nearly 100 men brought in from surrounding states and Canada. Then, on May 9th, two miners were found alive. Hopes soared with the discovery of the men, and rescuers redoubled their attempts. But that night workers began to recover bodies. The grim task continued until May 13th, eleven days after the fire began. There were no more survivors to be found.

Ninety-one men died from carbon monoxide poisoning inside the Sunshine Mine. The fire, with its deadly smoke, apparently started by spontaneous combustion in a junk pile deep within the mine. The Sunshine Mine disaster remains one of the deadliest in U.S. history.

At about noon on May 2nd, 1972 miners noticed smoke inside the Sunshine Silver Mine near Kellogg. The mine is a labyrinth of tunnels and shafts a mile deep and more. It was almost impossible to tell just where the smoke was coming from.

One hundred seventy-three men were in the mine on that fateful day. At the first hint of smoke they began to evacuate.

There are tales of bravery and tragedy too lengthy to recount. A hoistman ran his elevator-like hoist, lifting men through the toxic smoke to safety--until he died at the controls. One rescuer gave up his oxygen mask to an escaping miner, and in turn gave up his life. Heroism was the rule of the day with so many lives at stake.

Rescue efforts went on for a week, with nearly 100 men brought in from surrounding states and Canada. Then, on May 9th, two miners were found alive. Hopes soared with the discovery of the men, and rescuers redoubled their attempts. But that night workers began to recover bodies. The grim task continued until May 13th, eleven days after the fire began. There were no more survivors to be found.

Ninety-one men died from carbon monoxide poisoning inside the Sunshine Mine. The fire, with its deadly smoke, apparently started by spontaneous combustion in a junk pile deep within the mine. The Sunshine Mine disaster remains one of the deadliest in U.S. history.

Published on May 02, 2022 04:00

March 31, 2022

Hacked (Tap to read)

I was the victim of a Facebook hack, the result of which is that I am currently locked out of Facebook. The FBI and Idaho Attorney General's office are investigating. Meanwhile, I will be unable to post indefinitely.

Speaking of Idaho will be back. Please be patient.

Speaking of Idaho will be back. Please be patient.

Published on March 31, 2022 04:00