Rick Just's Blog, page 100

February 28, 2022

Pop Quiz (Tap to read)

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture. If you missed that story, click the letter for a link.

1). Why were starlings introduced to the U.S.?

A. To drive less desirable birds from their nesting sites

B. So that everyone could enjoy their murmurations

C. Because they were mentioned in a Shakespeare play

D. Someone thought they would make a great game bird

E. So they could pick biting insects off of cattle

2). How big were cougars in Idaho according to Governor C.F. Bottolfsen?

A. 10 feet, nose to tail

B. 12 feet, nose to tail

C. 15 feet, nose to tail

D. 20 feet, nose to tail

E. 22 feet, nose to tail

3). Who was the Blue Lady of Boise?

A. A shopkeeper with methemoglobinemia

B. A singer known best for her mournful renditions

C. The wife of a Boise mayor who always dressed in blue

D. Trick question: It’s a rock formation near Castle Rock

E. An alleged ghost

4). Who was Gobo Fango?

A. A vaudeville entertainer popular in North Idaho

B. It was the stage name of actor George Waldron

C. A Black sheepherder killed by a local rancher

D. The companion dog of “Idaho Bill”

E. That was the pseudonym of a frequent writer of letters to the editor

5) What nationality was Jesus Urquides?

A. Probably Mexican

B. Probably Spanish

C. Probably Basque

D. Probably Costa Rican

E. Probably Hawaiian Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

1, C

2, D

3, E

4, C

5, A

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). Why were starlings introduced to the U.S.?

A. To drive less desirable birds from their nesting sites

B. So that everyone could enjoy their murmurations

C. Because they were mentioned in a Shakespeare play

D. Someone thought they would make a great game bird

E. So they could pick biting insects off of cattle

2). How big were cougars in Idaho according to Governor C.F. Bottolfsen?

A. 10 feet, nose to tail

B. 12 feet, nose to tail

C. 15 feet, nose to tail

D. 20 feet, nose to tail

E. 22 feet, nose to tail

3). Who was the Blue Lady of Boise?

A. A shopkeeper with methemoglobinemia

B. A singer known best for her mournful renditions

C. The wife of a Boise mayor who always dressed in blue

D. Trick question: It’s a rock formation near Castle Rock

E. An alleged ghost

4). Who was Gobo Fango?

A. A vaudeville entertainer popular in North Idaho

B. It was the stage name of actor George Waldron

C. A Black sheepherder killed by a local rancher

D. The companion dog of “Idaho Bill”

E. That was the pseudonym of a frequent writer of letters to the editor

5) What nationality was Jesus Urquides?

A. Probably Mexican

B. Probably Spanish

C. Probably Basque

D. Probably Costa Rican

E. Probably Hawaiian

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)1, C

2, D

3, E

4, C

5, A

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on February 28, 2022 04:00

February 27, 2022

Blaine County's Weird Shape (Tap to read)

Have you ever wondered why Idaho’s Blaine County is shaped so weirdly? Each county shape in the state is unique, but Blaine County calls attention to itself by sending a tentacle far south of its bulk, like an ameba reaching out to snatch a snack. It reminds one of the shapes of those tortuous voting districts some states have where politicians string together partisans from one party or the other in order to win elections.

Political intrigue partly explains the weird shape of Blaine County. It is something of a leftover county, with its shape changing four times between March 5, 1895, and February 6, 1917.

There was much drama over the shape of counties in February 1895 when the question of Blaine County was first debated in the Idaho Legislature. Rumors abounded that Nampa wanted to be a part of Ada County and that Boise County was about to be split up with part of it to be named Butte County. The rumors were so frequent and contradictory that one legislative wag ginned up a phony bill to create one giant county called Grant County. It would have consolidated the 21 counties that then existed into a single county. Grant County’s county seat was to be the city of Shoshone, which was one of the towns then embroiled over a debate regarding what was to become of Alturas and Logan counties. The bill writer, tongue in check, thought that making one county, the boundaries of which would match the boundaries of the state, would solve all the boundary problems.

The proposal to create a county called Blaine, named for 1854 Republican presidential nominee James G. Blaine, was contentious because of the financial pickle Alturas County, which was in a state of bankruptcy. Citizens of Logan County, which was to be combined with Alturas to form Blaine County, objected to taking on the debt of Alturas.

Poor Alturas. Its last gasp would come on March 5, 1895 when the Blaine county bill prevailed. It was a bloated county upon its creation by the Idaho Territorial Legislature in 1864. Taking up more map space than the states of Maryland, New Jersey, and Delaware combined, it was doomed to be whittled down to nothing.

The new Blaine County didn’t retain its original shape for long, either. The Legislature carved Lincoln County from it just a couple of weeks later, on March 18. It lost a little more weight in January of 1913 when Power County was extracted from Blaine. The dieting county slimmed down to its present shape in February 1917 when Butte and Camas counties were trimmed away.

Through all that reduction in size, Blaine County managed to keep that weird little strip reaching down to Lake Walcott because it improved the county’s tax base. That narrow reach of land encompassed a bit of railroad property, taxes for which helped Blaine County keep its books balanced.

Political intrigue partly explains the weird shape of Blaine County. It is something of a leftover county, with its shape changing four times between March 5, 1895, and February 6, 1917.

There was much drama over the shape of counties in February 1895 when the question of Blaine County was first debated in the Idaho Legislature. Rumors abounded that Nampa wanted to be a part of Ada County and that Boise County was about to be split up with part of it to be named Butte County. The rumors were so frequent and contradictory that one legislative wag ginned up a phony bill to create one giant county called Grant County. It would have consolidated the 21 counties that then existed into a single county. Grant County’s county seat was to be the city of Shoshone, which was one of the towns then embroiled over a debate regarding what was to become of Alturas and Logan counties. The bill writer, tongue in check, thought that making one county, the boundaries of which would match the boundaries of the state, would solve all the boundary problems.

The proposal to create a county called Blaine, named for 1854 Republican presidential nominee James G. Blaine, was contentious because of the financial pickle Alturas County, which was in a state of bankruptcy. Citizens of Logan County, which was to be combined with Alturas to form Blaine County, objected to taking on the debt of Alturas.

Poor Alturas. Its last gasp would come on March 5, 1895 when the Blaine county bill prevailed. It was a bloated county upon its creation by the Idaho Territorial Legislature in 1864. Taking up more map space than the states of Maryland, New Jersey, and Delaware combined, it was doomed to be whittled down to nothing.

The new Blaine County didn’t retain its original shape for long, either. The Legislature carved Lincoln County from it just a couple of weeks later, on March 18. It lost a little more weight in January of 1913 when Power County was extracted from Blaine. The dieting county slimmed down to its present shape in February 1917 when Butte and Camas counties were trimmed away.

Through all that reduction in size, Blaine County managed to keep that weird little strip reaching down to Lake Walcott because it improved the county’s tax base. That narrow reach of land encompassed a bit of railroad property, taxes for which helped Blaine County keep its books balanced.

Published on February 27, 2022 04:00

February 26, 2022

Chief Washakie (Tap to read)

Back before there was an Idaho, or a Wyoming, or pick your state, there was a Shoshoni land that stretched irregularly from Death Valley north to where Salmon is today, and east into the Wind River Range. It encompassed much of southern Idaho and northern Utah.

It was into this vast territory that a boy was born, known then as Pinaquanah and today as Washakie. He would become a leader of the Shoshone people and would be richly honored. He may have met his first white men in 1811 along the Boise River when Wilson Hunt’s party was on its way through to Astoria. When he was 16 he met Jim Bridger. They were friends for many years and Bridger married one of Washakie’s daughters in 1850.

Washakie became the chief of the Eastern Snakes in the late 1800s. His people were friendly with fur traders and later soldiers. He and his warriors helped General George Crook defeat the Sioux following Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn.

Chief Washakie, and other tribal chiefs, signed the Fort Bridger treaties of 1863 and 1868, establishing large reservations for the Shoshone people. The Eastern Shoshones, Washakie’s band, initially received more than three million acres in the Wind River Country. In most such treaties between the U.S. and Indian tribes, the tribes saw their lands dramatically reduced in size. Today the Wind River Reservation is about 2.2 million acres.

Washakie loved gambling and was a renowned artist, using hides as the medium on which he painted. He was interested in religion and became first an Episcopalian, then later in his life, as he became friends with Brigham Young, a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He believed deeply in education. Today’s Chief Washakie Foundation carries on his tradition of educating his people with his great-great grandson as its head.

Chief Washakie was honored in many ways. In 1878 Fort Washakie, in Wyoming, became the first—and to date—only U.S. military outpost to be named after a Native American. Wyoming’s Washakie County is named for him. Washakie, Utah, now a ghost town, carries his name. The dining hall at the University of Wyoming is Washakie Hall. There’s a statue of the man in downtown Casper. More importantly, Chief Washakie is depicted in a bronze sculpture in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol building. Two ships have carried his name, the Liberty Ship SS Chief Washakie commissioned during World War II, and the USS Washakie, a U.S. Navy harbor tug. When he died in 1900 he was given a full military funeral.

It was into this vast territory that a boy was born, known then as Pinaquanah and today as Washakie. He would become a leader of the Shoshone people and would be richly honored. He may have met his first white men in 1811 along the Boise River when Wilson Hunt’s party was on its way through to Astoria. When he was 16 he met Jim Bridger. They were friends for many years and Bridger married one of Washakie’s daughters in 1850.

Washakie became the chief of the Eastern Snakes in the late 1800s. His people were friendly with fur traders and later soldiers. He and his warriors helped General George Crook defeat the Sioux following Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn.

Chief Washakie, and other tribal chiefs, signed the Fort Bridger treaties of 1863 and 1868, establishing large reservations for the Shoshone people. The Eastern Shoshones, Washakie’s band, initially received more than three million acres in the Wind River Country. In most such treaties between the U.S. and Indian tribes, the tribes saw their lands dramatically reduced in size. Today the Wind River Reservation is about 2.2 million acres.

Washakie loved gambling and was a renowned artist, using hides as the medium on which he painted. He was interested in religion and became first an Episcopalian, then later in his life, as he became friends with Brigham Young, a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He believed deeply in education. Today’s Chief Washakie Foundation carries on his tradition of educating his people with his great-great grandson as its head.

Chief Washakie was honored in many ways. In 1878 Fort Washakie, in Wyoming, became the first—and to date—only U.S. military outpost to be named after a Native American. Wyoming’s Washakie County is named for him. Washakie, Utah, now a ghost town, carries his name. The dining hall at the University of Wyoming is Washakie Hall. There’s a statue of the man in downtown Casper. More importantly, Chief Washakie is depicted in a bronze sculpture in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol building. Two ships have carried his name, the Liberty Ship SS Chief Washakie commissioned during World War II, and the USS Washakie, a U.S. Navy harbor tug. When he died in 1900 he was given a full military funeral.

Published on February 26, 2022 04:00

February 25, 2022

Pulling Contests on Pulling Hill (Tap to read)

The Google Earth satellite photo of Pulling Hill on the northeast side of the Presto Bench a few miles outside of Firth looks a little like an art installation. Motorcycles installed it, for the most part. I helped with that as a kid. In the winter the hillsides were where everyone went to sleigh and sometimes snowmobile.

Pulling Hill always seemed like an odd name to me. It turns out that pulling contests were often run between cars in the early days of same. Maybe some of those contests involved pulling something, but this one was all about a hill climb.

It seems that a car salesman from Boise (even then a metropolis that engendered great suspicion in rural parts of the state) walked into Rasumus Hansen’s 3A Garage in Blackfoot. A disagreement ensued over which car was better at climbing hills, the salesman’s car or Rass Hansen’s car. Sadly, the make and model of each is lost to history or we could take side bets.

They set a day for the contest and agreed that the winner would receive $100 from the loser. When the day came a large crowd was on hand to witness the event. Leading up to the main event a few other cars tried the hill with varying results. Rass Hansen went first in the main climb, getting only part-way up the hill. The man from Boise chugged all the way to the top in his car. However, upon inspection, it turned out the Boise man had modified his car for the occasion, something explicitly forbidden in the bet. Hansen’s car was declared the winner by default and the reputation of people from Boise dropped another notch.

From that day forward, the steep hill on Presto Bench became Pulling Hill. Many more matches of automobile fitness followed, as did motorcycle races, bucking horse contests, and submarine races. That last is actually a local term for necking more appropriately applied when the occupants of an automobile were parked near the Firth River Bottoms overlooking the Snake River, but the sport was much the same.

Pulling Hill became a county recreation site in 1970. The official name for the 25.5 acre site is Presto Park.

Thanks to Snake River Echoes, the quarterly publication of the Upper Snake River Valley Historical Society for much of the information in this post, found in the Spring 1985 edition in an article by Ruby Hansen Hanft.

Pulling Hill always seemed like an odd name to me. It turns out that pulling contests were often run between cars in the early days of same. Maybe some of those contests involved pulling something, but this one was all about a hill climb.

It seems that a car salesman from Boise (even then a metropolis that engendered great suspicion in rural parts of the state) walked into Rasumus Hansen’s 3A Garage in Blackfoot. A disagreement ensued over which car was better at climbing hills, the salesman’s car or Rass Hansen’s car. Sadly, the make and model of each is lost to history or we could take side bets.

They set a day for the contest and agreed that the winner would receive $100 from the loser. When the day came a large crowd was on hand to witness the event. Leading up to the main event a few other cars tried the hill with varying results. Rass Hansen went first in the main climb, getting only part-way up the hill. The man from Boise chugged all the way to the top in his car. However, upon inspection, it turned out the Boise man had modified his car for the occasion, something explicitly forbidden in the bet. Hansen’s car was declared the winner by default and the reputation of people from Boise dropped another notch.

From that day forward, the steep hill on Presto Bench became Pulling Hill. Many more matches of automobile fitness followed, as did motorcycle races, bucking horse contests, and submarine races. That last is actually a local term for necking more appropriately applied when the occupants of an automobile were parked near the Firth River Bottoms overlooking the Snake River, but the sport was much the same.

Pulling Hill became a county recreation site in 1970. The official name for the 25.5 acre site is Presto Park.

Thanks to Snake River Echoes, the quarterly publication of the Upper Snake River Valley Historical Society for much of the information in this post, found in the Spring 1985 edition in an article by Ruby Hansen Hanft.

Published on February 25, 2022 04:00

February 24, 2022

A Road Named Protest (Tap to read)

If you’ve been reading these history posts for a while, you know that I’m interested in how things got their names. I’ve done posts on how the state got its name, where county names came from, and why cities in Idaho have their names. I’m even a proud member pf the Idaho Geographic Names Advisory Committee.

So, you would not be surprised that the name Protest Road in Boise has always intrigued me. What protest was it commemorating? Women’s suffrage, perhaps? Something to do with a labor strike from back in the Wobbly days? Maybe it came from the civil rights struggle.

As it turns out, Protest Road is named such because of a protest. Over a road. That road.

In March of 1950 stakes were going up in South Boise for a new road that would connect the area to a new fire station being built on the rim above. That wasn’t a surprise. Residents had voted to construct such a road. But in the mind of a citizen protest committee, the stakes indicated the road was being planned in the wrong place. The road as staked out would send fire engines to Boise Avenue, where they would have to reverse their direction and come back into South Boise along a narrow and twisting thoroughfare. They had voted on a route that would allow engines to access South Boise more directly.

More than 500 citizens showed up in early community meetings on the matter. They voted to form the South Boise Citizens Protest Committee. Ultimately a sensible alignment of the road was proposed that seemed to work for everyone. It was decided that the road should be called Protest Road in commemoration of the efforts of the Committee.

This wasn’t the first time a citizen protest committee from South Boise had been formed. I found an article from 1907 in the Statesman headlined “Citizens of South Boise to Hold an Indignation Meeting Next Tuesday Night.” That “indignation” was also over a transportation issue, poor rail service to the area.

It’s not surprising that residents take their transportation issues seriously in South Boise. Transportation was there before there was a South Boise. The Oregon Trail runs through that section of town.

Thanks to Barbara Perry Bauer for her help with research on this post and for her delightful little book South Boise Scrapbook.

So, you would not be surprised that the name Protest Road in Boise has always intrigued me. What protest was it commemorating? Women’s suffrage, perhaps? Something to do with a labor strike from back in the Wobbly days? Maybe it came from the civil rights struggle.

As it turns out, Protest Road is named such because of a protest. Over a road. That road.

In March of 1950 stakes were going up in South Boise for a new road that would connect the area to a new fire station being built on the rim above. That wasn’t a surprise. Residents had voted to construct such a road. But in the mind of a citizen protest committee, the stakes indicated the road was being planned in the wrong place. The road as staked out would send fire engines to Boise Avenue, where they would have to reverse their direction and come back into South Boise along a narrow and twisting thoroughfare. They had voted on a route that would allow engines to access South Boise more directly.

More than 500 citizens showed up in early community meetings on the matter. They voted to form the South Boise Citizens Protest Committee. Ultimately a sensible alignment of the road was proposed that seemed to work for everyone. It was decided that the road should be called Protest Road in commemoration of the efforts of the Committee.

This wasn’t the first time a citizen protest committee from South Boise had been formed. I found an article from 1907 in the Statesman headlined “Citizens of South Boise to Hold an Indignation Meeting Next Tuesday Night.” That “indignation” was also over a transportation issue, poor rail service to the area.

It’s not surprising that residents take their transportation issues seriously in South Boise. Transportation was there before there was a South Boise. The Oregon Trail runs through that section of town.

Thanks to Barbara Perry Bauer for her help with research on this post and for her delightful little book South Boise Scrapbook.

Published on February 24, 2022 04:00

February 23, 2022

Pass that Plate (Tap to read)

License plates are ubiquitous. Everyone who has a car, truck, or motorcycle in Idaho owns at least a couple of them. So why the heck would anyone collect them? Because they’re interesting, and because most of them get thrown away or recycled, so the surviving plates become rarer and rarer as their litter mates succumb. Yes, I just used “litter mates” to describe license plates. Maybe that’s a first and this post will become collectable.

I’m a very minor collector of license plates. I have about 40 or 50, mostly because I keep my personalized plates when it’s time to replace them. And I’m old. There’s that.

Collectors lust for one of Idaho’s first state plates, issued in 1913. There are only a couple of those still around. Idaho issued only single plates for automobiles in 1913 and 1914, ensuring a little extra rarity. Other rarities are early city plates issued by Hailey, Nampa, Payette, Weiser, Lewiston, and Boise, prior to 1913. According to Dan Smith, an acknowledged expert on Idaho license plates, only 19 of those are known to exist.

Did you know there were once hand-painted Idaho license plates? From 1913 to 1924 dealer plates were embossed with the words IDAHO DEALER, but there were no embossed numbers. Dealers had numbers painted on them by professionals. For a time, if you lost your license plate you would be issued a “flat” plate with no number on it, and you were expected to have your number painted on it by a professional. There are only a handful of those around anymore.

The county designators on plates have been around since 1932, but they weren’t all the familiar letter/number combination we see today. In 1932, for instance, Ada county was A1, while Lewis County was K4. It wasn’t until 1945 that the system we’re familiar with today became the standard.

So what’s that oddball license plate you have hanging in your garage worth? It depends. Condition is important as well as rarity. I looked at eBay to see what prices were like. You can get a lot of interesting Idaho plates for less than $50. Someone was asking $500 for a particularly special one. You’ll want to collect them because you find it an interesting hobby, not because you have kids to put through college.

Thanks to Dan Smith for his years of knowledge that went into his Idaho License Plates book, and for the photo. Message me if you want to know how to get a copy. Your local bookstore probably doesn’t have one.

I’m a very minor collector of license plates. I have about 40 or 50, mostly because I keep my personalized plates when it’s time to replace them. And I’m old. There’s that.

Collectors lust for one of Idaho’s first state plates, issued in 1913. There are only a couple of those still around. Idaho issued only single plates for automobiles in 1913 and 1914, ensuring a little extra rarity. Other rarities are early city plates issued by Hailey, Nampa, Payette, Weiser, Lewiston, and Boise, prior to 1913. According to Dan Smith, an acknowledged expert on Idaho license plates, only 19 of those are known to exist.

Did you know there were once hand-painted Idaho license plates? From 1913 to 1924 dealer plates were embossed with the words IDAHO DEALER, but there were no embossed numbers. Dealers had numbers painted on them by professionals. For a time, if you lost your license plate you would be issued a “flat” plate with no number on it, and you were expected to have your number painted on it by a professional. There are only a handful of those around anymore.

The county designators on plates have been around since 1932, but they weren’t all the familiar letter/number combination we see today. In 1932, for instance, Ada county was A1, while Lewis County was K4. It wasn’t until 1945 that the system we’re familiar with today became the standard.

So what’s that oddball license plate you have hanging in your garage worth? It depends. Condition is important as well as rarity. I looked at eBay to see what prices were like. You can get a lot of interesting Idaho plates for less than $50. Someone was asking $500 for a particularly special one. You’ll want to collect them because you find it an interesting hobby, not because you have kids to put through college.

Thanks to Dan Smith for his years of knowledge that went into his Idaho License Plates book, and for the photo. Message me if you want to know how to get a copy. Your local bookstore probably doesn’t have one.

Published on February 23, 2022 04:00

February 22, 2022

Lake, Reservoir. Whatever. (Tap to read)

Sometimes place names are a little deceptive, and deliberately so.

The town of Cascade was founded in 1912, consolidating the communities of Van Wyck, Thunder City, and Crawford, according to Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. The town was named for nearby Cascade Falls. Cascade Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1948, creating Cascade Reservoir and effectively drowning the falls the reservoir was named for.

Cascade Reservoir hosted boaters and anglers for more than 50 years until 1999, when Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade. So, we have a lake that isn’t a lake named for a waterfall which the (not) lake destroyed.

I get it. I’m not complaining about the dam or the reservoir, only noting the irony that can sometimes come about when naming something.

Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade because local tourism promoters thought it sounded better. They were right. Lake Cascade sounds like something nature created and is thus more enticing than what we may picture in our minds when we think of a reservoir.

Another example of this bait and switch is Logger Creek in Boise. Logger Creek sounds much more scenic than Logger Ditch. Ditch it is, though. It was created in 1865 to power a waterwheel flour mill, which later became a sawmill. The ditch was then used to float logs to the mill. Much of Logger Creek was filled in years later, but the remaining section, which pulls water from the Boise River now does little else but take that water for a scenic ride along the Greenbelt before diverting it back into the river.

The town of Cascade was founded in 1912, consolidating the communities of Van Wyck, Thunder City, and Crawford, according to Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. The town was named for nearby Cascade Falls. Cascade Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1948, creating Cascade Reservoir and effectively drowning the falls the reservoir was named for.

Cascade Reservoir hosted boaters and anglers for more than 50 years until 1999, when Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade. So, we have a lake that isn’t a lake named for a waterfall which the (not) lake destroyed.

I get it. I’m not complaining about the dam or the reservoir, only noting the irony that can sometimes come about when naming something.

Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade because local tourism promoters thought it sounded better. They were right. Lake Cascade sounds like something nature created and is thus more enticing than what we may picture in our minds when we think of a reservoir.

Another example of this bait and switch is Logger Creek in Boise. Logger Creek sounds much more scenic than Logger Ditch. Ditch it is, though. It was created in 1865 to power a waterwheel flour mill, which later became a sawmill. The ditch was then used to float logs to the mill. Much of Logger Creek was filled in years later, but the remaining section, which pulls water from the Boise River now does little else but take that water for a scenic ride along the Greenbelt before diverting it back into the river.

Published on February 22, 2022 04:00

February 21, 2022

Boise's Blue Lady Ghost (Tap to read)

You’d be a blue lady, too, if you were a) a lady and b) hanging around a Boise street corner at midnight in January with nothing to keep you warm but a dress and a flimsy scarf.

But it wasn’t the temperature that made the blue lady blue. Ghosts are little affected by the cold, or so I’ve heard. She was blue because she was dressed in blue. Her blue dress, long hair, and flimsy white scarf were the only descriptors that come down through the pages of the Idaho Statesman from 1916.

Four Chinese men walked from Idaho to Main along Seventh Street shortly after midnight on January 2. They saw a woman in blue emerge from the alley and walk to the corner in front of a saloon. When the men reached the corner, she vanished.

And here’s where the dog enters the story. Joe Peterson’s dog lived in the neighborhood. Peterson was the Idaho attorney general at the time. The dog, a St. Bernard named Rover (can I get a rimshot?), howled whenever the blue lady appeared.

Whether his howling brought the blue lady or simply announced her presence was of some conjecture. In either case, the howling was mournful, disturbing, and a little frightening. As one does with dogs who won’t shut up, someone fed him something. This was Chinatown, so a steaming bowl of pork fried rice was handy. Rover wolfed it down.

Over the next few nights, the howling of the dog, the appearance of the blue lady, the feeding of the dog, and the disappearance of the blue lady all got rolled into a cause and effect tale that was very much to Rover’s advantage.

If the pork fried rice failed to satiate the dog, someone would add a side of noodles.

Office Day, who walked the beat in that area, investigated. He quickly found the dog and heard it howl but never saw the lady.

The Statesman sent an intrepid report to investigate the ghost sighting. Some of the men who lived in the neighborhood claimed they’d followed her nearly around the block before she vanished just as they caught up with her. Someone had apparently fed the dog.

As reported in the Statesman, the writer did not have long to wait when the midnight hour struck.

“Suddenly, old Rover, from the middle of the street, commenced a most uncanny howling.

“The reporter’s blood commenced to congeal. The wind whistled round the corner and, catching up a bit of the snow, whirled it into a ghostly figure. The reporter strained his eye for the blue skirt; he could see, he imagined, the flowing hair, the white about the neck, and—yes, the blue skirt was beginning to materialize, when—the entire ghostly form vanished as old Rover gave his lingering wail, and the Chinaman rushed from the restaurant door and hastily threw onto the sidewalk a full sized meal, even for Rover, and rushed back to the restaurant, glancing furtively over his shoulder.”

There was speculation, of course, about who the blue lady was. Some thought she might have been an apparition of one of two Chinese women who had attempted suicide in the local jail. The operative word there was “attempted.” The general consensus was that ghosts came from the dead, not those who wished to be.

The blue lady quit appearing when Peterson moved Rover to a farm out in the country where he probably never ate pork fried rice again. Was the dog in cahoots with the specter? Humm. Maybe the blue lady could have made a nice… living(?) as a dog trainer.

But it wasn’t the temperature that made the blue lady blue. Ghosts are little affected by the cold, or so I’ve heard. She was blue because she was dressed in blue. Her blue dress, long hair, and flimsy white scarf were the only descriptors that come down through the pages of the Idaho Statesman from 1916.

Four Chinese men walked from Idaho to Main along Seventh Street shortly after midnight on January 2. They saw a woman in blue emerge from the alley and walk to the corner in front of a saloon. When the men reached the corner, she vanished.

And here’s where the dog enters the story. Joe Peterson’s dog lived in the neighborhood. Peterson was the Idaho attorney general at the time. The dog, a St. Bernard named Rover (can I get a rimshot?), howled whenever the blue lady appeared.

Whether his howling brought the blue lady or simply announced her presence was of some conjecture. In either case, the howling was mournful, disturbing, and a little frightening. As one does with dogs who won’t shut up, someone fed him something. This was Chinatown, so a steaming bowl of pork fried rice was handy. Rover wolfed it down.

Over the next few nights, the howling of the dog, the appearance of the blue lady, the feeding of the dog, and the disappearance of the blue lady all got rolled into a cause and effect tale that was very much to Rover’s advantage.

If the pork fried rice failed to satiate the dog, someone would add a side of noodles.

Office Day, who walked the beat in that area, investigated. He quickly found the dog and heard it howl but never saw the lady.

The Statesman sent an intrepid report to investigate the ghost sighting. Some of the men who lived in the neighborhood claimed they’d followed her nearly around the block before she vanished just as they caught up with her. Someone had apparently fed the dog.

As reported in the Statesman, the writer did not have long to wait when the midnight hour struck.

“Suddenly, old Rover, from the middle of the street, commenced a most uncanny howling.

“The reporter’s blood commenced to congeal. The wind whistled round the corner and, catching up a bit of the snow, whirled it into a ghostly figure. The reporter strained his eye for the blue skirt; he could see, he imagined, the flowing hair, the white about the neck, and—yes, the blue skirt was beginning to materialize, when—the entire ghostly form vanished as old Rover gave his lingering wail, and the Chinaman rushed from the restaurant door and hastily threw onto the sidewalk a full sized meal, even for Rover, and rushed back to the restaurant, glancing furtively over his shoulder.”

There was speculation, of course, about who the blue lady was. Some thought she might have been an apparition of one of two Chinese women who had attempted suicide in the local jail. The operative word there was “attempted.” The general consensus was that ghosts came from the dead, not those who wished to be.

The blue lady quit appearing when Peterson moved Rover to a farm out in the country where he probably never ate pork fried rice again. Was the dog in cahoots with the specter? Humm. Maybe the blue lady could have made a nice… living(?) as a dog trainer.

Published on February 21, 2022 04:00

February 20, 2022

J.R. and his Chips (Tap to read)

J.R. Simplot was not born in Idaho. He was born in—wait for it—Iowa, thus further confusing those who can’t tell the two states apart.

Simplot didn’t stay in Iowa long. His parents brought him and his six siblings to a little farm near Declo, Idaho when he was about a year old. One could say he left a bit of a mark on the state’s business history.

J.R. made his first money from feeding pigs, and then kept making it. And making it. He lived in a time when it wasn’t unusual to quit school after completing the eighth grade, which was what he did. Most dropouts didn’t go on to become the largest shipper of fresh potatoes in the nation, or become a phosphate king, which he also did. The story of how his company developed a method of freezing French fried potatoes, and how he did a handshake deal with Ray Kroc to supply fries to McDonalds is well known.

J.R. liked to say that he was big in chips. He meant potato chips, but he also meant computer chips. He was key in the early days of computer chip maker Micron Technology. Simplot gave the Parkinson brothers of Blackfoot $1 million in the early days of the company, then put in another $20 million to help Micron build its first fabrication plant in Boise.

J.R. Simplot died in 2008 at age 99. His company recently built a new headquarters building in Boise, and the J.R. Simplot Foundation built something called JUMP next door. That stands for Jack’s Urban Meeting Place. It’s the site of public performances in the arts, various makers studios, giant slippery slides, and a bunch of tractors. That description doesn’t do it justice. None does. You have to see it yourself to understand the vision. It’s worth a visit for the tractors alone. About 50 antique tractors from J.R. Simplot’s personal collection are on display at JUMP in downtown Boise.

The photo of J.R. Simplot with some unidentified kind of tuber is from the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

Simplot didn’t stay in Iowa long. His parents brought him and his six siblings to a little farm near Declo, Idaho when he was about a year old. One could say he left a bit of a mark on the state’s business history.

J.R. made his first money from feeding pigs, and then kept making it. And making it. He lived in a time when it wasn’t unusual to quit school after completing the eighth grade, which was what he did. Most dropouts didn’t go on to become the largest shipper of fresh potatoes in the nation, or become a phosphate king, which he also did. The story of how his company developed a method of freezing French fried potatoes, and how he did a handshake deal with Ray Kroc to supply fries to McDonalds is well known.

J.R. liked to say that he was big in chips. He meant potato chips, but he also meant computer chips. He was key in the early days of computer chip maker Micron Technology. Simplot gave the Parkinson brothers of Blackfoot $1 million in the early days of the company, then put in another $20 million to help Micron build its first fabrication plant in Boise.

J.R. Simplot died in 2008 at age 99. His company recently built a new headquarters building in Boise, and the J.R. Simplot Foundation built something called JUMP next door. That stands for Jack’s Urban Meeting Place. It’s the site of public performances in the arts, various makers studios, giant slippery slides, and a bunch of tractors. That description doesn’t do it justice. None does. You have to see it yourself to understand the vision. It’s worth a visit for the tractors alone. About 50 antique tractors from J.R. Simplot’s personal collection are on display at JUMP in downtown Boise.

The photo of J.R. Simplot with some unidentified kind of tuber is from the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

Published on February 20, 2022 04:00

February 19, 2022

A Spanish Packer and a Spanish Village (Tap to read)

When you were a miner in the early days of Idaho, you couldn’t just order up supplies from Amazon. There were no planes, no trucks, and most importantly, no roads. Everything had to be packed in to remote areas, usually by a string of mules. If you had a big job, you counted on Jesus Urquides to get what you needed where you needed it.

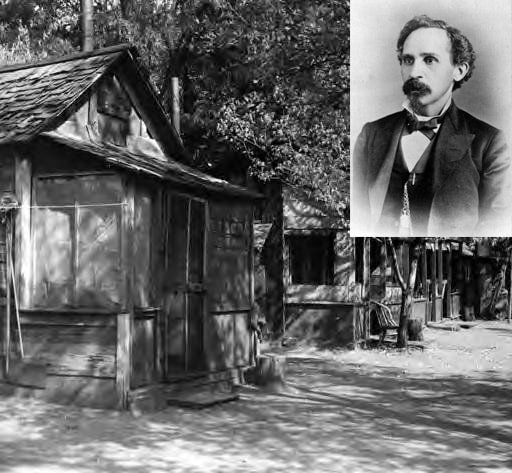

Urquides was born in 1833, perhaps in San Francisco, as many sources claim, or perhaps in Sonora, Mexico, as he once said in a magazine interview. He is often called Boise’s Basque packer, though he was probably Mexican, not Basque.

Urquides started freighting in 1850, taking supplies to the Forty-niners—the miners. The football team of the same name would come along about a hundred years later.

He bragged that there was not a camp of any size between California and Montana that he had not packed supplies to. He packed a lot of whiskey, ammunition for the military, railroad track, and the first mill to the mine at Thunder Mountain. We’re not talking about a couple of mules here. Urquides would have trains of 65 or more.

Probably his most famous packing feat came when he was called on to take a roll of copper wire for a tram to the Yellow Jacket mine outside of Challis. A roll of wire doesn’t seem like much, but it weighed 10,000 pounds. It had to be distributed in coils across 35 mules working three abreast. The tricky thing was that you couldn’t simply cut it and make a couple of tidy rolls for each mule. Cutting the wire, then splicing it back together would make it too dangerous to use on a tram. Urquides’ solution was to wrap each mule in a coil of wire it could handle—maybe up to 300 pounds—then string it on to the next mule, and on and on. Of course, if one mule took a tumble, he’d drag other mules down with him. This happened several times. Each time Urquides and his men would get the mules back on their feet, make sure the wire was okay, then set off again. He only had 70 miles to travel, much of it up and down mountains and through canyons.

Ridiculous as the arrangement seems, Urquides made it work. He delivered the unbroken wire to its destination. He once commented, “I never coveted another job like that.”

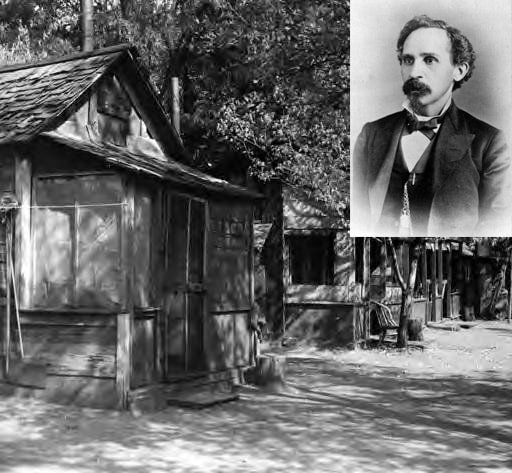

In the late 1870s Urquides built about 30 one-room buildings in Boise behind his home at 115 Main, to house his drivers and wranglers. It became known as “Spanish Village.” This shanty town would last about a hundred years, furnishing low-rent housing long past the days of 65-mule strings.

Jesus Urquides died in 1928 at age 95 and is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, not far from his Boise home. The photo of Spanish Village and Urquides are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Urquides was born in 1833, perhaps in San Francisco, as many sources claim, or perhaps in Sonora, Mexico, as he once said in a magazine interview. He is often called Boise’s Basque packer, though he was probably Mexican, not Basque.

Urquides started freighting in 1850, taking supplies to the Forty-niners—the miners. The football team of the same name would come along about a hundred years later.

He bragged that there was not a camp of any size between California and Montana that he had not packed supplies to. He packed a lot of whiskey, ammunition for the military, railroad track, and the first mill to the mine at Thunder Mountain. We’re not talking about a couple of mules here. Urquides would have trains of 65 or more.

Probably his most famous packing feat came when he was called on to take a roll of copper wire for a tram to the Yellow Jacket mine outside of Challis. A roll of wire doesn’t seem like much, but it weighed 10,000 pounds. It had to be distributed in coils across 35 mules working three abreast. The tricky thing was that you couldn’t simply cut it and make a couple of tidy rolls for each mule. Cutting the wire, then splicing it back together would make it too dangerous to use on a tram. Urquides’ solution was to wrap each mule in a coil of wire it could handle—maybe up to 300 pounds—then string it on to the next mule, and on and on. Of course, if one mule took a tumble, he’d drag other mules down with him. This happened several times. Each time Urquides and his men would get the mules back on their feet, make sure the wire was okay, then set off again. He only had 70 miles to travel, much of it up and down mountains and through canyons.

Ridiculous as the arrangement seems, Urquides made it work. He delivered the unbroken wire to its destination. He once commented, “I never coveted another job like that.”

In the late 1870s Urquides built about 30 one-room buildings in Boise behind his home at 115 Main, to house his drivers and wranglers. It became known as “Spanish Village.” This shanty town would last about a hundred years, furnishing low-rent housing long past the days of 65-mule strings.

Jesus Urquides died in 1928 at age 95 and is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, not far from his Boise home. The photo of Spanish Village and Urquides are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on February 19, 2022 04:00