Rick Just's Blog, page 101

February 18, 2022

The Land Rush Train Crash (Tap to read)

When I ran across this story on GenDisasters.com, it drew my attention because it was labeled as an electric train collision in Caldwell, Idaho. But, as I read the story, I found that someone was a little confused. The crash occurred at a little spot on the railroad called Gibson, just west of Coeur d’Alene. Many of the train passengers were going back and forth between Coeur d’Alene and Spokane to take part in the “Indian land opening” in 1909. That was when much of what was previously allocated to the Coeur d’Alene Tribe for their reservation was opened for homesteading. As with most land rushes, chaos commenced.

Those running the lottery for the land rush estimated that between 10 and 20 thousand people might take part. Officials in Coeur d’Alene were ecstatic, until the people started showing up like herds of bison. More than 7,000 came. There wasn’t a hotel room or even a room in a private house left to rent. Meanwhile, hoteliers in Spokane warned that Coeur d’Alene prices would be too high and encouraged rushers to stay in their city.

Fortune seekers on their way between Coeur d’Alene and Spokane to participate in the land rush packed two Spokane & Inland Railway trains on Saturday afternoon, July 31, 1909, the No. 5 eastbound and the No. 20 westbound. Why they were on the same track was for investigators to later determine, but on that afternoon the only thing that mattered was that they met head-on, each train going about 45 miles per hour.

The Twin Falls Times News covered the story in depth a few days later because a local man was one of many injured.

“It was the smoking car of the westbound train that all of the deaths occurred and most of the injured were hurt. This car was crowded to the limit, the aisle being packed with standing passengers.

“When the crash came the partition separating the motorman from the passengers was swept backward and with it the front seats. Passengers in the front of the car were thrown on top of those in the rear, while the front car of the eastbound train telescoped the smoker and smashed the seats, framework and window glass into an inextrable (sic) mass, from which the victims were extricated with difficulty.”

Sixteen died in the crash. Reports of the number injured varied from 75 to 116.

Though on the day of the crash most of the injured and dead were headed to Spokane, it was the Idaho land rush that had brought many of them to the area in the first place.

Those running the lottery for the land rush estimated that between 10 and 20 thousand people might take part. Officials in Coeur d’Alene were ecstatic, until the people started showing up like herds of bison. More than 7,000 came. There wasn’t a hotel room or even a room in a private house left to rent. Meanwhile, hoteliers in Spokane warned that Coeur d’Alene prices would be too high and encouraged rushers to stay in their city.

Fortune seekers on their way between Coeur d’Alene and Spokane to participate in the land rush packed two Spokane & Inland Railway trains on Saturday afternoon, July 31, 1909, the No. 5 eastbound and the No. 20 westbound. Why they were on the same track was for investigators to later determine, but on that afternoon the only thing that mattered was that they met head-on, each train going about 45 miles per hour.

The Twin Falls Times News covered the story in depth a few days later because a local man was one of many injured.

“It was the smoking car of the westbound train that all of the deaths occurred and most of the injured were hurt. This car was crowded to the limit, the aisle being packed with standing passengers.

“When the crash came the partition separating the motorman from the passengers was swept backward and with it the front seats. Passengers in the front of the car were thrown on top of those in the rear, while the front car of the eastbound train telescoped the smoker and smashed the seats, framework and window glass into an inextrable (sic) mass, from which the victims were extricated with difficulty.”

Sixteen died in the crash. Reports of the number injured varied from 75 to 116.

Though on the day of the crash most of the injured and dead were headed to Spokane, it was the Idaho land rush that had brought many of them to the area in the first place.

Published on February 18, 2022 04:00

February 17, 2022

A Plastic Harvest (Tap to read)

Brown plastic potato pins are ubiquitous in Idaho. Don't you have one? The Idaho Potato Commission will sell you a bag of 50 for $7. It was that commission, specifically its director Jay Sherlock, that came up with the idea for the pins.

It was 1965 and the Girl Scouts were having their famous Girl Scout Roundup at Farragut State Park. Idaho was famous for potatoes, but the girls were disappointed because they couldn’t see them growing in North Idaho. As quoted in a 1970 Idaho Statesman interview, Sherlock said that “Idaho First National Bank scraped up some potato banks and gave them to the girls as souvenirs.” They didn’t get pins, though.

Sherlock remembered a pickle company from his childhood that had distributed pickle pins, so he decided to borrow that idea. By 1967, when the World Boy Scout Jamboree came to Farragut, the Idaho Potato Commission was ready with plastic potato pins. They have distributed, conservatively, 2.5 bajillion of them since.

It was 1965 and the Girl Scouts were having their famous Girl Scout Roundup at Farragut State Park. Idaho was famous for potatoes, but the girls were disappointed because they couldn’t see them growing in North Idaho. As quoted in a 1970 Idaho Statesman interview, Sherlock said that “Idaho First National Bank scraped up some potato banks and gave them to the girls as souvenirs.” They didn’t get pins, though.

Sherlock remembered a pickle company from his childhood that had distributed pickle pins, so he decided to borrow that idea. By 1967, when the World Boy Scout Jamboree came to Farragut, the Idaho Potato Commission was ready with plastic potato pins. They have distributed, conservatively, 2.5 bajillion of them since.

Published on February 17, 2022 04:00

February 16, 2022

A Forgotten Military Base (Tap to read)

Idaho contributed to the war effort during World War II as the site of Farragut Naval Training Station, where more than 292,000 “boots” got their training. There was another training base proposed for Idaho about the same time. The Army even started construction on the site.

Farragut was perfect for the Navy because of Lake Pend Oreille. The second base would be on a lake, too, but it wasn’t the lake that made the site “perfect.” M.S. Benedict, Targhee National Forest Supervisor at the time, was quoted as saying, “The weather is severe with sub-zero temperatures for most of the winter. The area has about 4 feet of snow and the many slopes in the area are ideal for training ski troops. There is mountainous country, too, which could be used for toughening soldiers.” Benedict also counted the “high velocity winds (that) sweep across the area” as a plus.

The War Department was looking for a place to train troops who would be experts at skiing and winter survival.

A 100,000-acre site surrounding Henrys Lake just a few miles from West Yellowstone, Montana was selected for the training center. The camp would host 35,000 troops and cost some $20 million to build.

The State of Idaho was on board with the plan. Gov. Chase Clark revealed that the Idaho Transportation Department had ordered a huge new rotary snow plow to keep the roads in the area of the proposed base open.

Construction contracts were let in 1941 and buildings started going up for the new base. Foundations and vaults appeared and the structures began to take shape.

Almost immediately the Army Quartermaster began to question much about the project from high rates paid for rental vehicles to confusion and a lack of direction for the construction.

When that “perfect” winter weather hit, all construction ceased. In the spring of 1942 salvageable materials were hauled off and demolition equipment was moved in to bring down the bones of the buildings.

The country was at war, so why the Army did what it did was kept secret. Did contractor issues kill the base so quickly? That seems unlikely.

Thomas Howell, who lives in Ashton, has done considerable research on this subject, and it is from his website where I obtained the information for this short piece. Howell has a theory that it was trumpeter swans that killed the base, and he provides some compelling information to back that up. There were only 140 adults and 69 cygnets in the Lower 48 at that time mostly at Montana’s Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and the Railroad Ranch in Island Park (now Harriman State Park). Wildlife enthusiasts were not wild about the idea of introducing men shooting artillery into trumpeter swan habitat.

I urge you to read more about this on Tom’s site, and see the pictures of remaining foundations and other (pardon the pun) concrete evidence of the ill-fated base that can still be seen today near Henrys Lake State Park.

Farragut was perfect for the Navy because of Lake Pend Oreille. The second base would be on a lake, too, but it wasn’t the lake that made the site “perfect.” M.S. Benedict, Targhee National Forest Supervisor at the time, was quoted as saying, “The weather is severe with sub-zero temperatures for most of the winter. The area has about 4 feet of snow and the many slopes in the area are ideal for training ski troops. There is mountainous country, too, which could be used for toughening soldiers.” Benedict also counted the “high velocity winds (that) sweep across the area” as a plus.

The War Department was looking for a place to train troops who would be experts at skiing and winter survival.

A 100,000-acre site surrounding Henrys Lake just a few miles from West Yellowstone, Montana was selected for the training center. The camp would host 35,000 troops and cost some $20 million to build.

The State of Idaho was on board with the plan. Gov. Chase Clark revealed that the Idaho Transportation Department had ordered a huge new rotary snow plow to keep the roads in the area of the proposed base open.

Construction contracts were let in 1941 and buildings started going up for the new base. Foundations and vaults appeared and the structures began to take shape.

Almost immediately the Army Quartermaster began to question much about the project from high rates paid for rental vehicles to confusion and a lack of direction for the construction.

When that “perfect” winter weather hit, all construction ceased. In the spring of 1942 salvageable materials were hauled off and demolition equipment was moved in to bring down the bones of the buildings.

The country was at war, so why the Army did what it did was kept secret. Did contractor issues kill the base so quickly? That seems unlikely.

Thomas Howell, who lives in Ashton, has done considerable research on this subject, and it is from his website where I obtained the information for this short piece. Howell has a theory that it was trumpeter swans that killed the base, and he provides some compelling information to back that up. There were only 140 adults and 69 cygnets in the Lower 48 at that time mostly at Montana’s Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and the Railroad Ranch in Island Park (now Harriman State Park). Wildlife enthusiasts were not wild about the idea of introducing men shooting artillery into trumpeter swan habitat.

I urge you to read more about this on Tom’s site, and see the pictures of remaining foundations and other (pardon the pun) concrete evidence of the ill-fated base that can still be seen today near Henrys Lake State Park.

Published on February 16, 2022 04:00

February 15, 2022

Some Haydens in Idaho (Tap to read)

A reader asked where the name Hayden came from for Hayden Creek in North Idaho. It seemed like a simple request, and I found the answer quickly in Lalia Boone’s definitive Idaho Place Names. Probably. Her explanation for the name Hayden Creek referred to a creek in Lemhi County, not the one that flows into Hayden Lake. That Hayden Creek flows from Hayden Basin. The basin and creek were named for Jim Hayden who was an early packer and freighter in the area. Hayden’s claim to fame was peppered with gunfire. Bill Smith, who was one of the first to discover gold in Leesburg, was playing cards with Jim Hayden in 1871. There was a dispute about a hand. Smith took umbrage at Hayden and fired at the man. Hayden was said to be unarmed, but he found a gun somewhere and shot back, killing Smith. Hayden was acquitted when he went to trial. His relief at that was short-lived. Hayden was killed by Indians in Birch Creek Valley in 1877.

The Hayden Creek our reader asked about flows into Hayden Lake in Kootenai County and is not mentioned in Boone's book. The lake and town are named after Mathew Hayden so it follows that the creek probably also carries his name. Hayden was reportedly (wait for it…) playing cards with John Hager at Hager’s cabin. There was no gunplay involved with this one. The two men agreed to name the lake after the winner of a seven-up game. Hayden won.

But wait! There’s more! We can’t forget Hayden Peak in Owyhee County. It was named after Everett Hayden, a surveyor working for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s. Reportedly there was some local grumbling at the time because Hayden had never even been near the peak.

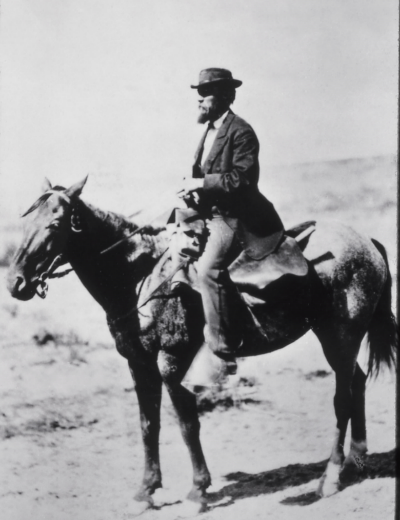

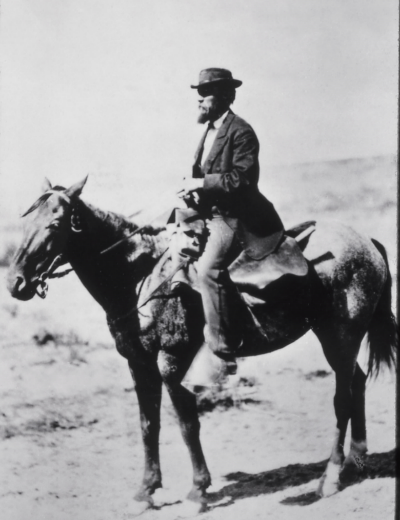

And, maybe there should be something else named Hayden in Idaho after a man the state has so far not honored. It was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (photo) who lead the famous Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871, which passed through Fort Hall on its way to what would become our nation’s first national park. The expedition named a lot of things, including Higham Peak in Bingham County, but nothing in Idaho bears the name of its leader.

The Hayden Creek our reader asked about flows into Hayden Lake in Kootenai County and is not mentioned in Boone's book. The lake and town are named after Mathew Hayden so it follows that the creek probably also carries his name. Hayden was reportedly (wait for it…) playing cards with John Hager at Hager’s cabin. There was no gunplay involved with this one. The two men agreed to name the lake after the winner of a seven-up game. Hayden won.

But wait! There’s more! We can’t forget Hayden Peak in Owyhee County. It was named after Everett Hayden, a surveyor working for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s. Reportedly there was some local grumbling at the time because Hayden had never even been near the peak.

And, maybe there should be something else named Hayden in Idaho after a man the state has so far not honored. It was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (photo) who lead the famous Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871, which passed through Fort Hall on its way to what would become our nation’s first national park. The expedition named a lot of things, including Higham Peak in Bingham County, but nothing in Idaho bears the name of its leader.

Published on February 15, 2022 04:00

February 14, 2022

Idaho Bill (Tap to read)

Idaho Bill was a well-known character in the 1920s. While doing research on him I found a hundred or so mentions of his exploits in newspapers nationwide. One of the few states where newspapers seemed to ignore him was Idaho.

When Idaho searches turned up scant evidence of Idaho Bill, I began to wonder if his nickname had anything to do with Idaho at all.

I first ran across Col. R.B. Pearson—popularly known as Idaho Bill—in a Leslie’s Weekly from September, 1921. The gist of the article was that the Colonel was providing a service to rodeos that had recently become a necessity. Rodeos had previously found unbroken horses at about any cattle ranch nearby. But in the 1920s, ranches could no longer afford to keep horses that weren’t ready to work. So, Idaho Bill and some other entrepreneurs began gathering up broncos with bad reputations to supply to rodeos. For $600 to $1000 he would supply rodeos with 25 or 30 horses for three or four days, guaranteeing that they would buck.

The Leslie’s article, and many others I found said that Col. R.B. Pearson was born—probably without the rank—at or near Hastings, Nebraska while his folks were coming west on the Oregon Trail. That story morphed around a bit, but the upshot was that he was not born in Idaho. I found a reliable source that said he was also not born on the Oregon Trail, but in Sweden. His parents came to Nebraska when he was four.

R.B. Pearson went by Barney in his early days. His Swedish name, Bonde (pronounced boon-duh) was just not American enough. His father bought a ranch in the Weiser area and asked his son to run it.

According to many newspaper articles, Idaho Bill was a favorite Indian scout for Buffalo Bill, George Armstrong Custer, and others. How a transplanted Idahoan even met those people is open to speculation. Especially when Buffalo Bill died when Idaho Bill was eight.

Idaho Bill had a habit of roping anything that moved. Cows were no challenge for him, so he began roping wolves and coyotes. In 1921 newspapers all around the country ran a story datelined El Paso that began “A wild cinnamon bear went joy riding out San Antonio street in a claw-torn open car. Col. R.B. Pearson, bearded invader of the wilds for the last 45 years, was chauffeur for the bear.”

The story went on to say that Idaho Bill had roped the bear as a seven-month-old cub weighing 180 pounds. Speculation was that the bear would weigh 1,100 pounds when full grown.

“This is the ninth bear Colonel Pearson has roped.” The article stated. “He handled lions in Africa by the same method.”

The instinct of a carnivore to being roped and dragged is probably to try to get away by pulling, so this is… plausible?

This wasn’t the first time Idaho Bill had used his rope to impress the masses, and it wouldn’t be the last. In 1908 he roped wolves and delivered them to an exhibition in Chicago. In 1927 he delivered a 375 pound cinnamon bear to President Calvin Coolidge in Washington, DC. He was said to have capture many cougars and not a few snow leopards with his lariat.

Coolidge was not the only president to be charmed by Idaho Bill. Teddy Roosevelt is said to have befriended the Colonel. Some accounts say he visited Idaho Bill on a presidential tour of the state in 1903. Idaho papers covered that trip hour by hour without any mention of a side trip to Weiser.

Pearson acquired some wealth from his exploits, mostly from the wild west shows he produced. In 1923, while on his way to deliver broncos to a rodeo in East Las Vegas, New Mexico, Idaho bill lost his wallet in Santa Fe. He was loading the recalcitrant horses when the wallet fell out. Idaho Bill stated that there was about $40,000 in the wallet, three $10,000 bills (yes, they were in circulation at the time) and bills of lower denomination. He was offering a reward of $20,000 for the return of his wallet. No word on whether he ever got it back.

One more story about his money might have been because of that lost wallet. In 1930 the Falls City Nebraska Journal reported that Idaho Bill kept his money in his boots. He walked around with a couple of $10,000 bills and several $1,000 bills rolled up in his boots.

Idaho Bill demonstrated his “bank” for a local congressman. He pulled out a six gun along with the money as a deterrent to anyone who might be tempted to palm one of the bills he passed around for inspection.

For an in-depth article on Idaho Bill, read a story by Monty McCord in the January 2022 issue of True West Magazine.

Idaho Bill died in Los Angeles in 1942.

Idaho Bill with a bear in the back of his car.

Idaho Bill with a bear in the back of his car.

When Idaho searches turned up scant evidence of Idaho Bill, I began to wonder if his nickname had anything to do with Idaho at all.

I first ran across Col. R.B. Pearson—popularly known as Idaho Bill—in a Leslie’s Weekly from September, 1921. The gist of the article was that the Colonel was providing a service to rodeos that had recently become a necessity. Rodeos had previously found unbroken horses at about any cattle ranch nearby. But in the 1920s, ranches could no longer afford to keep horses that weren’t ready to work. So, Idaho Bill and some other entrepreneurs began gathering up broncos with bad reputations to supply to rodeos. For $600 to $1000 he would supply rodeos with 25 or 30 horses for three or four days, guaranteeing that they would buck.

The Leslie’s article, and many others I found said that Col. R.B. Pearson was born—probably without the rank—at or near Hastings, Nebraska while his folks were coming west on the Oregon Trail. That story morphed around a bit, but the upshot was that he was not born in Idaho. I found a reliable source that said he was also not born on the Oregon Trail, but in Sweden. His parents came to Nebraska when he was four.

R.B. Pearson went by Barney in his early days. His Swedish name, Bonde (pronounced boon-duh) was just not American enough. His father bought a ranch in the Weiser area and asked his son to run it.

According to many newspaper articles, Idaho Bill was a favorite Indian scout for Buffalo Bill, George Armstrong Custer, and others. How a transplanted Idahoan even met those people is open to speculation. Especially when Buffalo Bill died when Idaho Bill was eight.

Idaho Bill had a habit of roping anything that moved. Cows were no challenge for him, so he began roping wolves and coyotes. In 1921 newspapers all around the country ran a story datelined El Paso that began “A wild cinnamon bear went joy riding out San Antonio street in a claw-torn open car. Col. R.B. Pearson, bearded invader of the wilds for the last 45 years, was chauffeur for the bear.”

The story went on to say that Idaho Bill had roped the bear as a seven-month-old cub weighing 180 pounds. Speculation was that the bear would weigh 1,100 pounds when full grown.

“This is the ninth bear Colonel Pearson has roped.” The article stated. “He handled lions in Africa by the same method.”

The instinct of a carnivore to being roped and dragged is probably to try to get away by pulling, so this is… plausible?

This wasn’t the first time Idaho Bill had used his rope to impress the masses, and it wouldn’t be the last. In 1908 he roped wolves and delivered them to an exhibition in Chicago. In 1927 he delivered a 375 pound cinnamon bear to President Calvin Coolidge in Washington, DC. He was said to have capture many cougars and not a few snow leopards with his lariat.

Coolidge was not the only president to be charmed by Idaho Bill. Teddy Roosevelt is said to have befriended the Colonel. Some accounts say he visited Idaho Bill on a presidential tour of the state in 1903. Idaho papers covered that trip hour by hour without any mention of a side trip to Weiser.

Pearson acquired some wealth from his exploits, mostly from the wild west shows he produced. In 1923, while on his way to deliver broncos to a rodeo in East Las Vegas, New Mexico, Idaho bill lost his wallet in Santa Fe. He was loading the recalcitrant horses when the wallet fell out. Idaho Bill stated that there was about $40,000 in the wallet, three $10,000 bills (yes, they were in circulation at the time) and bills of lower denomination. He was offering a reward of $20,000 for the return of his wallet. No word on whether he ever got it back.

One more story about his money might have been because of that lost wallet. In 1930 the Falls City Nebraska Journal reported that Idaho Bill kept his money in his boots. He walked around with a couple of $10,000 bills and several $1,000 bills rolled up in his boots.

Idaho Bill demonstrated his “bank” for a local congressman. He pulled out a six gun along with the money as a deterrent to anyone who might be tempted to palm one of the bills he passed around for inspection.

For an in-depth article on Idaho Bill, read a story by Monty McCord in the January 2022 issue of True West Magazine.

Idaho Bill died in Los Angeles in 1942.

Idaho Bill with a bear in the back of his car.

Idaho Bill with a bear in the back of his car.

Published on February 14, 2022 04:00

February 13, 2022

The Hansen Bridge (Tap to read)

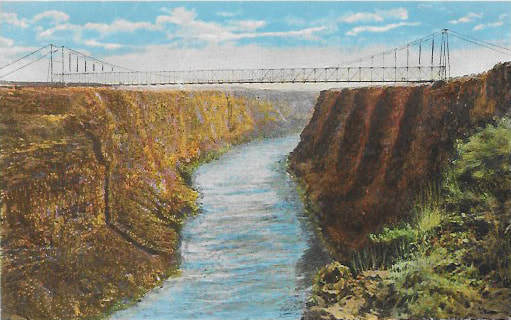

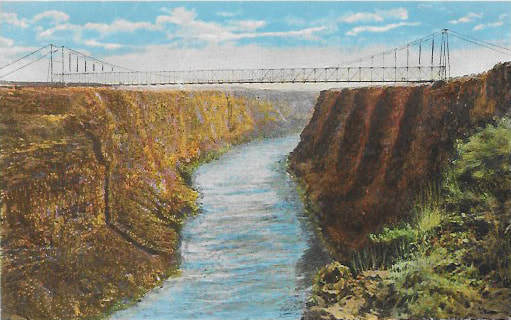

The Hansen Bridge, which spanned the Snake River Canyon near the town of Hansen, was a bit of a wonder in 1919 when it was built. It was 608 feet across, making it the second-longest span in the country at the time. At 325 feet above the river, some accounts had it listed as being the highest suspension bridge in the world. And some accounts also listed it as being 345 feet above the Snake and 688 feet long. Break out your tape measure.

Superlatives aside, it held no record for width. At 16 feet, it seemed not to foresee a future where a couple of trucks might want to pass in opposite directions. The original wooden decking on the bridge also seemed better suited to wagons, whose use was waning, than automobiles.

Some locals may have been disappointed in the celebration for the bridge. Police seized 120 pints of booze one resident of Buhl was hoping to sell to the crowds when Gov. D.W. Davis officially opened the bridge.

The Hansen Bridge was important in its day, even if transportation needs quickly outgrew it. It remained in service until 1966.

Superlatives aside, it held no record for width. At 16 feet, it seemed not to foresee a future where a couple of trucks might want to pass in opposite directions. The original wooden decking on the bridge also seemed better suited to wagons, whose use was waning, than automobiles.

Some locals may have been disappointed in the celebration for the bridge. Police seized 120 pints of booze one resident of Buhl was hoping to sell to the crowds when Gov. D.W. Davis officially opened the bridge.

The Hansen Bridge was important in its day, even if transportation needs quickly outgrew it. It remained in service until 1966.

Published on February 13, 2022 04:00

February 12, 2022

Sandpoint's Cedar Street Bridge (Tap to read)

What do you do with a bridge that has outlived its usefulness? Often old bridges are sold and moved to a new location, or torn down for scrap. Not the Cedar Creek Bridge in Sandpoint.

The 400-foot-long bridge was built sometime in the 1920s so that pedestrians and cars could go from downtown Sandpoint to the railroad depot. As travel by rail became less popular, so did the bridge. By the 1970s it had fallen into disuse. The city blocked off the decaying bridge to traffic.

In the early 80s city officials were thinking about tearing it down when local entrepreneur Scott Glickenhaus approached them with an idea. He had seen the Ponte Vecchio, the oldest bridge in Florence, Italy. That bridge had housed shops as well as functioning as a bridge since the 13th century. Why not something like that in Sandpoint?

The derelict bridge was reinforced with new pilings, and a new enclosed structure was built on top of it from tamarack timbers. Shop spaces were built and rented. The bridge/mini-mall was opened in 1983. Coldwater Creek leased a small space on the bridge in 1988. Then a small mail-order retailer in Sandpoint, this was Coldwater Creek’s first retail store.

By 1995, Coldwater Creek had leased the entire bridge, which is about 16,000 square feet of space. In 2005 Coldwater Creek converted a downtown building for its use and moved out of the bridge.

A Sandpoint group purchased the bridge in 2006 and put over a million dollars into renovations. Today the Cedar Street Bridge hosts cart vendors, restaurants, gift shops, and boutiques and is a key feature of downtown Sandpoint.

The 400-foot-long bridge was built sometime in the 1920s so that pedestrians and cars could go from downtown Sandpoint to the railroad depot. As travel by rail became less popular, so did the bridge. By the 1970s it had fallen into disuse. The city blocked off the decaying bridge to traffic.

In the early 80s city officials were thinking about tearing it down when local entrepreneur Scott Glickenhaus approached them with an idea. He had seen the Ponte Vecchio, the oldest bridge in Florence, Italy. That bridge had housed shops as well as functioning as a bridge since the 13th century. Why not something like that in Sandpoint?

The derelict bridge was reinforced with new pilings, and a new enclosed structure was built on top of it from tamarack timbers. Shop spaces were built and rented. The bridge/mini-mall was opened in 1983. Coldwater Creek leased a small space on the bridge in 1988. Then a small mail-order retailer in Sandpoint, this was Coldwater Creek’s first retail store.

By 1995, Coldwater Creek had leased the entire bridge, which is about 16,000 square feet of space. In 2005 Coldwater Creek converted a downtown building for its use and moved out of the bridge.

A Sandpoint group purchased the bridge in 2006 and put over a million dollars into renovations. Today the Cedar Street Bridge hosts cart vendors, restaurants, gift shops, and boutiques and is a key feature of downtown Sandpoint.

Published on February 12, 2022 04:00

February 11, 2022

A Scandal that Probably Wasn't (Tap to read)

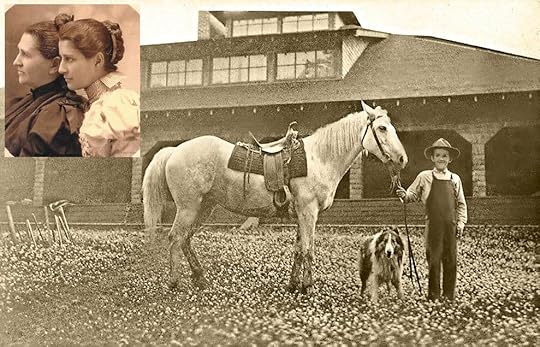

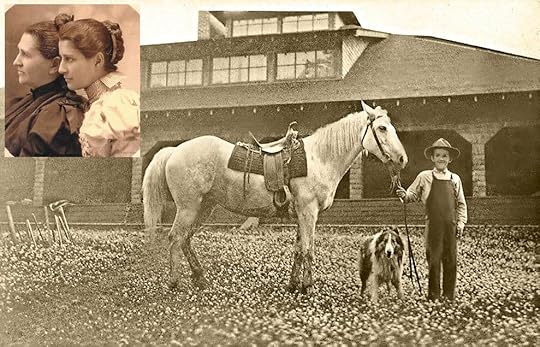

One step over from history is persistent, salacious rumor. Such is the story of Frieda Bethmann, one-time resident of Pardee, Idaho.

A 1990 story in the Lewiston Tribune by Diane Pettit, which is easily found on the web, recounts the persistent rumors about Frieda and her son Miner. Frieda was the daughter of Francis Alfred Ferdinand Bethmann and Emile Bethmann. Her father was in the sugar importing business and her mother was active in the kindergarten movement.

The Bethmanns were friends with President Grover Cleveland. That Frieda turned up with a “nephew” named Miner who was almost certainly her son started the rumors rumbling. Cleveland admitted to fathering one illegitimate child in his bachelor days. Perhaps there was a second.

About 1908 after the death of her father, Frieda and her mother moved to a grand house overlooking the Clearwater River. Rumors had Pres. Cleveland building the house for his “mistress.” In fact, the house was built by Frieda’s mother. She purchased the land and oversaw its construction herself.

But it was Frieda everyone was interested in. Rumor had it that she had served as Cleveland’s appointment secretary, no doubt with emphasis on the “appointment.” In fact, she had served briefly as a kindergarten instructor to the Cleveland children.

The rumors had Cleveland making several visits to Idaho by rail. No photo or newspaper account seems to exist that would prove that. Cleveland allegedly signed the guest register at a Pomeroy, Washington hotel, but even that tenuous clue seems suspect as the signature looks nothing like Cleveland’s signature.

Miner Bethmann had reporters showing up on his doorstep from time to time throughout his life. He is said to have driven them off without comment.

The rumors persist and, yes, this retelling will only help keep them alive. We will probably never know who Miner’s father was. We do know that certain parts of the speculation, such as who built the house, are incorrect. Rumors about Cleveland visiting Frieda in Pardee seem not to add up. The Bethmanns moved there in 1908, the year Grover Cleveland died at age 71.

Pres. Cleveland may not have fathered a boy who grew up in Idaho, but he did do one thing that helped shape the state. In 1887 there was a movement in Congress to split off the northern part of Idaho Territory and attach it to Washington. The bill landed on President Cleveland’s desk, where it died as a pocket veto.

Thanks to Dick Southern for supplying much information on the Bethmanns in his exhaustive local book on Pardee, Idaho history They Called This Canyon “Home.”

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

A 1990 story in the Lewiston Tribune by Diane Pettit, which is easily found on the web, recounts the persistent rumors about Frieda and her son Miner. Frieda was the daughter of Francis Alfred Ferdinand Bethmann and Emile Bethmann. Her father was in the sugar importing business and her mother was active in the kindergarten movement.

The Bethmanns were friends with President Grover Cleveland. That Frieda turned up with a “nephew” named Miner who was almost certainly her son started the rumors rumbling. Cleveland admitted to fathering one illegitimate child in his bachelor days. Perhaps there was a second.

About 1908 after the death of her father, Frieda and her mother moved to a grand house overlooking the Clearwater River. Rumors had Pres. Cleveland building the house for his “mistress.” In fact, the house was built by Frieda’s mother. She purchased the land and oversaw its construction herself.

But it was Frieda everyone was interested in. Rumor had it that she had served as Cleveland’s appointment secretary, no doubt with emphasis on the “appointment.” In fact, she had served briefly as a kindergarten instructor to the Cleveland children.

The rumors had Cleveland making several visits to Idaho by rail. No photo or newspaper account seems to exist that would prove that. Cleveland allegedly signed the guest register at a Pomeroy, Washington hotel, but even that tenuous clue seems suspect as the signature looks nothing like Cleveland’s signature.

Miner Bethmann had reporters showing up on his doorstep from time to time throughout his life. He is said to have driven them off without comment.

The rumors persist and, yes, this retelling will only help keep them alive. We will probably never know who Miner’s father was. We do know that certain parts of the speculation, such as who built the house, are incorrect. Rumors about Cleveland visiting Frieda in Pardee seem not to add up. The Bethmanns moved there in 1908, the year Grover Cleveland died at age 71.

Pres. Cleveland may not have fathered a boy who grew up in Idaho, but he did do one thing that helped shape the state. In 1887 there was a movement in Congress to split off the northern part of Idaho Territory and attach it to Washington. The bill landed on President Cleveland’s desk, where it died as a pocket veto.

Thanks to Dick Southern for supplying much information on the Bethmanns in his exhaustive local book on Pardee, Idaho history They Called This Canyon “Home.”

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

Published on February 11, 2022 04:00

February 10, 2022

Idaho's Quickie Divorces (Tap to read)

Just can’t wait to get a divorce? Well, Idaho is one of the states where the residency requirement is short. Back in 1937 the Legislature reduced the residency requirement for obtaining a divorce in Idaho from 90 days to six weeks. Governor Chase Clark quickly signed it.

It was a blatant attempt to cash in on the quickie divorce trade Nevada was famous for. They matched Nevada’s residency requirement. Representative Dan Cavanagh from Twin Falls said about his bill, “We have a chance to assist our hotels and our resorts. We should make an effort to develop these resources.”

It wasn’t so much that lawmakers thought people would flock to Burley or Weippe to establish residency for a speedy divorce. They had Sun Valley in mind. Such divorces were typically sought by the wealthy who could afford to “reside” in a state for a few weeks to take care of that messy domestic problem.

Some rich ex-lovers probably did come to Idaho, but Nevada kept the reputation for hasty divorces, and weddings that could take place even faster.

Nowadays, Idaho requires a nine-week residency, or 62 days. That’s the fourth shortest time in the nation. South Dakota requires just 60 days. Nevada is still at six weeks, or 42 days. Alaska, with no residency requirement at all, tops the list.

It was a blatant attempt to cash in on the quickie divorce trade Nevada was famous for. They matched Nevada’s residency requirement. Representative Dan Cavanagh from Twin Falls said about his bill, “We have a chance to assist our hotels and our resorts. We should make an effort to develop these resources.”

It wasn’t so much that lawmakers thought people would flock to Burley or Weippe to establish residency for a speedy divorce. They had Sun Valley in mind. Such divorces were typically sought by the wealthy who could afford to “reside” in a state for a few weeks to take care of that messy domestic problem.

Some rich ex-lovers probably did come to Idaho, but Nevada kept the reputation for hasty divorces, and weddings that could take place even faster.

Nowadays, Idaho requires a nine-week residency, or 62 days. That’s the fourth shortest time in the nation. South Dakota requires just 60 days. Nevada is still at six weeks, or 42 days. Alaska, with no residency requirement at all, tops the list.

Published on February 10, 2022 04:00

February 9, 2022

Chicken Dinner Road (Tap to read)

Chicken dinner. Yum. It was yummy enough to get a road paved once in Canyon County.

The story about how Chicken Dinner Road got its name appeared in the Idaho Press Tribune in about 1992, and was reprinted in 2008. It seems that Morris and Laura Lamb were friends of Governor C. Ben Ross and his wife Edna. They had eaten dinner together many times at the Lamb home.

One day, in the 1930s, Mrs. Lamb, who was noted for her chicken, rolls, and apple pie meals, was in Boise. She invited the governor to come to dinner. During the same conversation, she complained to Ross about the pitiful condition of the road in front of their place, which was dirt pocked with potholes. Ross was purported to say something like, “Laura, if you get that road graded and graveled, I’ll see to it it’s oiled.

Mrs. Lamb approached the Canyon County Commissioners who saw that opportunity as a fine one. They graded and graveled the road. As soon as that was done, she was on the phone to the governor reminding him of his promise. The next day—this part seems unlikely, but it’s Mrs. Lamb’s story—the next day the road was oiled.

The story got around and local hooligans thought it would be droll to put up a big hand-scrawled sign in front of the Lamb house in the dark of night. It read “Lamb’s Chicken Dinner Avenue.” Mrs. Lamb was not amused. Still, the name stuck as Chicken Dinner Road.

Idaho Press Tribune writer Dave Wilkins penned the original story.

The story about how Chicken Dinner Road got its name appeared in the Idaho Press Tribune in about 1992, and was reprinted in 2008. It seems that Morris and Laura Lamb were friends of Governor C. Ben Ross and his wife Edna. They had eaten dinner together many times at the Lamb home.

One day, in the 1930s, Mrs. Lamb, who was noted for her chicken, rolls, and apple pie meals, was in Boise. She invited the governor to come to dinner. During the same conversation, she complained to Ross about the pitiful condition of the road in front of their place, which was dirt pocked with potholes. Ross was purported to say something like, “Laura, if you get that road graded and graveled, I’ll see to it it’s oiled.

Mrs. Lamb approached the Canyon County Commissioners who saw that opportunity as a fine one. They graded and graveled the road. As soon as that was done, she was on the phone to the governor reminding him of his promise. The next day—this part seems unlikely, but it’s Mrs. Lamb’s story—the next day the road was oiled.

The story got around and local hooligans thought it would be droll to put up a big hand-scrawled sign in front of the Lamb house in the dark of night. It read “Lamb’s Chicken Dinner Avenue.” Mrs. Lamb was not amused. Still, the name stuck as Chicken Dinner Road.

Idaho Press Tribune writer Dave Wilkins penned the original story.

Published on February 09, 2022 04:00