Rick Just's Blog, page 97

March 30, 2022

Idaho's First County Seat (Tap to read)

During the first session of the Idaho Territorial Legislature in 1864, lawmakers created Oneida County, naming Soda Springs as its county seat. Although other counties had been created, Soda Springs was the first county seat to be named.

General Patrick Connor is credited with founding Soda Springs. In a sense, he founded two towns side-by-side. Connor’s troops led about 325 Morrisites to the valley where they platted the village of Morristown in 1863. Several years of cold weather discouraged the residents of Morristown, most of whom left for greener pastures. The Morristown site is mostly covered by Anderson Reservoir today.

Connor established Fort Connor on the hill above Morristown and laid out the town of Soda Springs above the fort. For a time, the two communities were known as Upper Town and Lower Town. The county offices for Oneida County were located at first in General Connor’s adobe store and hotel.

Soda Springs wasn’t the county seat for long. After three years Malad became the county seat of Oneida County. The town became a county seat again in 1919, this time for Caribou County when the Legislature divided up Oneida County. It remains the county seat today.

The area is famous for its soda deposits and numerous surrounding springs. The area was known as Soda Springs long before it was settled. Oregon Trail pioneers often stopped there.

The town has some interesting historical artifacts and one unique claim to fame. It has a mechanically timed geyser in the middle of town.

General Patrick Connor is credited with founding Soda Springs. In a sense, he founded two towns side-by-side. Connor’s troops led about 325 Morrisites to the valley where they platted the village of Morristown in 1863. Several years of cold weather discouraged the residents of Morristown, most of whom left for greener pastures. The Morristown site is mostly covered by Anderson Reservoir today.

Connor established Fort Connor on the hill above Morristown and laid out the town of Soda Springs above the fort. For a time, the two communities were known as Upper Town and Lower Town. The county offices for Oneida County were located at first in General Connor’s adobe store and hotel.

Soda Springs wasn’t the county seat for long. After three years Malad became the county seat of Oneida County. The town became a county seat again in 1919, this time for Caribou County when the Legislature divided up Oneida County. It remains the county seat today.

The area is famous for its soda deposits and numerous surrounding springs. The area was known as Soda Springs long before it was settled. Oregon Trail pioneers often stopped there.

The town has some interesting historical artifacts and one unique claim to fame. It has a mechanically timed geyser in the middle of town.

Published on March 30, 2022 04:00

March 29, 2022

Tolo Lake (Tap to read)

Tolo Lake, near Grangeville, was in the news in the fall of 1994 when the Idaho Department of Fish and Game was deepening the drained lake to provide for better fishing. Fish and Game was hoping to take out a dozen feet of silt so that it could better support fish and waterfowl. What they found during the excavation was neither fish nor fowl. It was something much, much larger.

Tolo Lake, which is about 36 acres, was a rendezvous point for the Nez Perce, or nimí·pu, for many years, including at the start of what became the Nez Perce War. Digging there could help wildlife, sure, but it could also shed light on the Tribe’s history. But when the first bone was exposed it was clearly not an artifact of the Nez Perce occupation of the site. It was a leg bone 4 ½ feet tall. Its discovery quickly piqued the interest of archeologists, so scientists from the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho State Historical Society, University of Idaho, and the Idaho Natural History Museum descended on the site where it was quickly determined that these were the bones of mammoths.

Mammoths were not called that for nothing. They weighed 10-15,000 pounds and stood about 14 feet at the shoulder. They were alive in North America as recently as 4,500 to 12,500 years ago, meaning they may have been familiar to the first people on the continent.

The dig exposed the bones of three mammoths and an ancient bison skull. The longest tusk discovered was measured at 16 feet. One of the tusks is on display at the Bicentennial Museum in Grangeville. The town also boasts a mammoth skeleton replica in an interpretive exhibit next to the Grangeville Chamber of Commerce office.

Tolo Lake, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, was named for a Nez Perce woman who alerted settlers of the rampage that started the Nez Perce War.

Tolo Lake, which is about 36 acres, was a rendezvous point for the Nez Perce, or nimí·pu, for many years, including at the start of what became the Nez Perce War. Digging there could help wildlife, sure, but it could also shed light on the Tribe’s history. But when the first bone was exposed it was clearly not an artifact of the Nez Perce occupation of the site. It was a leg bone 4 ½ feet tall. Its discovery quickly piqued the interest of archeologists, so scientists from the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho State Historical Society, University of Idaho, and the Idaho Natural History Museum descended on the site where it was quickly determined that these were the bones of mammoths.

Mammoths were not called that for nothing. They weighed 10-15,000 pounds and stood about 14 feet at the shoulder. They were alive in North America as recently as 4,500 to 12,500 years ago, meaning they may have been familiar to the first people on the continent.

The dig exposed the bones of three mammoths and an ancient bison skull. The longest tusk discovered was measured at 16 feet. One of the tusks is on display at the Bicentennial Museum in Grangeville. The town also boasts a mammoth skeleton replica in an interpretive exhibit next to the Grangeville Chamber of Commerce office.

Tolo Lake, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, was named for a Nez Perce woman who alerted settlers of the rampage that started the Nez Perce War.

Published on March 29, 2022 04:00

March 28, 2022

Valentine Wrote about Idaho (Tap to read)

So, here’s a guy (me) who writes quirky little stories about Idaho history, writing about a guy who wrote quirky little stories about Idaho history. This post may eat its own tail.

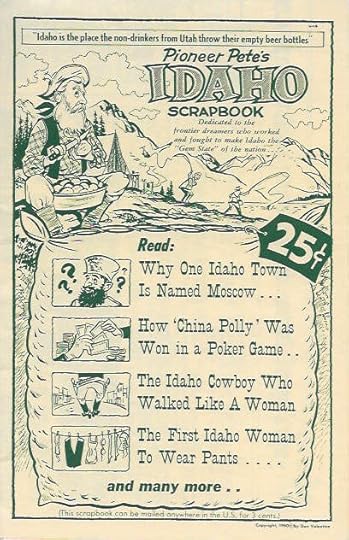

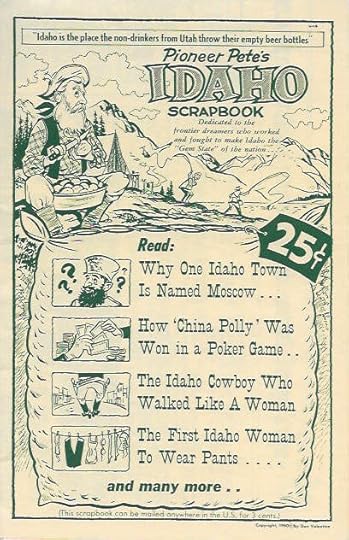

Dan Valentine wasn’t from Idaho, and he didn’t live here. Still, he was a purveyor of Idaho history, not in a scholarly sense, but in a storytelling sense. Valentine was a columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 30 years, retiring in 1980. In the 1950s and 60s, that paper was widely read in Southeastern Idaho. Enough so that Valentine included many humorous observations about the state.

Valentine published several books that grew out of his columns. They were often sold in restaurants and truck stops across Idaho and Utah. I ran across one of his publications recently while going through some family memorabilia. It’s a four-page newsletter quarter-folded into a book-sized pamphlet, called Pioneer Pete’s IDAHO Scrapbook, dated 1960. The amount of information he was able to squeeze in there is jaw-dropping. It included the story of Peg Leg Annie, a piece about Little Joe Monaghan, stories about Lana Turner, Polly Bemis, Ernest Hemingway, Diamondfield Jack, the lone parking meter in Murphy, and a dozen more. A better understanding of history has since put several of the stories into the apocryphal category, but at that time they were widely believed to be true.

Valentine’s material was featured on the Johnny Carson Show, as well as programs hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Garry Moore, and Art Linkletter.

A taste from the pamphlet:

Cats were allegedly worth $10 each in Idaho City once, because of a mouse problem.

Boise (at that time) was said to boast the only wooden cigar store Indian factory in the world.

If the state of Idaho was flattened out it would be larger than Texas.

Valentine was once accused of being a bit chauvinistic in his columns, but he’s also the guy who once said "I don't know why women would want to give up complete superiority for mere equality."

Dan Valentine passed away in 1991 at age 73.

Dan Valentine wasn’t from Idaho, and he didn’t live here. Still, he was a purveyor of Idaho history, not in a scholarly sense, but in a storytelling sense. Valentine was a columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 30 years, retiring in 1980. In the 1950s and 60s, that paper was widely read in Southeastern Idaho. Enough so that Valentine included many humorous observations about the state.

Valentine published several books that grew out of his columns. They were often sold in restaurants and truck stops across Idaho and Utah. I ran across one of his publications recently while going through some family memorabilia. It’s a four-page newsletter quarter-folded into a book-sized pamphlet, called Pioneer Pete’s IDAHO Scrapbook, dated 1960. The amount of information he was able to squeeze in there is jaw-dropping. It included the story of Peg Leg Annie, a piece about Little Joe Monaghan, stories about Lana Turner, Polly Bemis, Ernest Hemingway, Diamondfield Jack, the lone parking meter in Murphy, and a dozen more. A better understanding of history has since put several of the stories into the apocryphal category, but at that time they were widely believed to be true.

Valentine’s material was featured on the Johnny Carson Show, as well as programs hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Garry Moore, and Art Linkletter.

A taste from the pamphlet:

Cats were allegedly worth $10 each in Idaho City once, because of a mouse problem.

Boise (at that time) was said to boast the only wooden cigar store Indian factory in the world.

If the state of Idaho was flattened out it would be larger than Texas.

Valentine was once accused of being a bit chauvinistic in his columns, but he’s also the guy who once said "I don't know why women would want to give up complete superiority for mere equality."

Dan Valentine passed away in 1991 at age 73.

Published on March 28, 2022 04:00

March 27, 2022

Another Bigfoot Story (Tap to read)

I’ll probably put my foot in it on this one. My average-sized foot.

Bigfoot was a legendary Indian. He was known for the enormous tracks he left. Those tracks were alleged to be 17 ½” long, large even for a man 6’ 6” tall. Allegedly.

Bigfoot’s tracks were said to have been seen often at the site of depredations perpetrated by indigenous people on immigrants, especially in Idaho and Oregon. He was always one step ahead of anyone trying to catch him. Stepping was part of the legend. He always walked or ran rather than ride a horse, the better to leave moccasin tracks, not doubt.

In November of 1878, the Idaho Statesman ran a sensational story about the death of Bigfoot, written by William T. Anderson of Fisherman’s Cove, Humboldt County, California, who had heard it from the man who killed him. It detailed the 16 bullets that went into Bigfoot’s body, fired by one John Wheeler, who caught up with him in Owyhee County. Both of the big man’s arms and both of his legs were broken by bullets in the fight with Wheeler. Knowing he was at death’s door, Bigfoot decided to tell Wheeler his life story. He did so in prose that Dick d’Easum who wrote about it years later for the Idaho Statesman said was packed with enough “frothy facts of his boyhood and manhood to fill a Theodore Dreiser novel.”

In the Anderson account of the death of Bigfoot, the man had an actual name. He was Starr Wilkinson, who was a lad living in the Cherokee nation when his father, a white man, was hanged for murder. His mother was of mixed blood, Negro and Cherokee. The drama of Bigfoot’s life went on for thousands of words, many of which were quite eloquent for a man gurgling them out with 16 bullet wounds in his body.

Odd that Wheeler himself never said anything about killing one of the most notorious bad men in the West. Odd that he didn’t collect the $1,000 reward on the man’s head. Wheeler had an outlaw record to his own credit. He killed a man on Wood River in 1868, and got away with it. He was sentenced to ten years in prison for a stagecoach robbery in Oregon. After leaving prison, he was eventually sentenced to hang for a murder committed during another stage robbery, this time in California.

Awaiting certain death, Wheeler wrote a series of letters to his wife, his sister, his attorney, and a girlfriend reflecting on his life. He wrote not a word about Bigfoot. His musings complete, Wheeler took poison in jail rather than face the rope, and died.

Many historians discount the whole legend of Bigfoot. Dick d’Easum put it this way: “Just as nobody is ever attacked by a little bear, no pioneer of the 1860s ever lost a steer or a wife or a set of harness to a small Indian. Little Indians were sometimes caught and killed. Dead Indians had little feet. Indians that prowled and pillaged and slipped away unscathed were invariably possessed of huge trotters.”

So, if Bigfoot was a myth, why would you name a town after him? That town is Nampa, reportedly taking its name from Shoshoni words Namp (foot) and Puh (big), and by some reports named after the legendary Bigfoot. Historian Annie Laurie Bird did research on the name Nampa in 1966, concluding that it probably did come from a Shoshoni word pronounced “nambe” or “nambuh” and meaning footprint. She did not weigh in on the Bigfoot connection.

A marauding giant is such a good story that it may never die. It was good enough that Bigfoot was killed, again, in New Mexico, 14 years after he was ventilated in Owyhee County. No word on whether he was able to gasp out his life story that time.

A stature of Bigfoot in Parma.

A stature of Bigfoot in Parma.

Bigfoot was a legendary Indian. He was known for the enormous tracks he left. Those tracks were alleged to be 17 ½” long, large even for a man 6’ 6” tall. Allegedly.

Bigfoot’s tracks were said to have been seen often at the site of depredations perpetrated by indigenous people on immigrants, especially in Idaho and Oregon. He was always one step ahead of anyone trying to catch him. Stepping was part of the legend. He always walked or ran rather than ride a horse, the better to leave moccasin tracks, not doubt.

In November of 1878, the Idaho Statesman ran a sensational story about the death of Bigfoot, written by William T. Anderson of Fisherman’s Cove, Humboldt County, California, who had heard it from the man who killed him. It detailed the 16 bullets that went into Bigfoot’s body, fired by one John Wheeler, who caught up with him in Owyhee County. Both of the big man’s arms and both of his legs were broken by bullets in the fight with Wheeler. Knowing he was at death’s door, Bigfoot decided to tell Wheeler his life story. He did so in prose that Dick d’Easum who wrote about it years later for the Idaho Statesman said was packed with enough “frothy facts of his boyhood and manhood to fill a Theodore Dreiser novel.”

In the Anderson account of the death of Bigfoot, the man had an actual name. He was Starr Wilkinson, who was a lad living in the Cherokee nation when his father, a white man, was hanged for murder. His mother was of mixed blood, Negro and Cherokee. The drama of Bigfoot’s life went on for thousands of words, many of which were quite eloquent for a man gurgling them out with 16 bullet wounds in his body.

Odd that Wheeler himself never said anything about killing one of the most notorious bad men in the West. Odd that he didn’t collect the $1,000 reward on the man’s head. Wheeler had an outlaw record to his own credit. He killed a man on Wood River in 1868, and got away with it. He was sentenced to ten years in prison for a stagecoach robbery in Oregon. After leaving prison, he was eventually sentenced to hang for a murder committed during another stage robbery, this time in California.

Awaiting certain death, Wheeler wrote a series of letters to his wife, his sister, his attorney, and a girlfriend reflecting on his life. He wrote not a word about Bigfoot. His musings complete, Wheeler took poison in jail rather than face the rope, and died.

Many historians discount the whole legend of Bigfoot. Dick d’Easum put it this way: “Just as nobody is ever attacked by a little bear, no pioneer of the 1860s ever lost a steer or a wife or a set of harness to a small Indian. Little Indians were sometimes caught and killed. Dead Indians had little feet. Indians that prowled and pillaged and slipped away unscathed were invariably possessed of huge trotters.”

So, if Bigfoot was a myth, why would you name a town after him? That town is Nampa, reportedly taking its name from Shoshoni words Namp (foot) and Puh (big), and by some reports named after the legendary Bigfoot. Historian Annie Laurie Bird did research on the name Nampa in 1966, concluding that it probably did come from a Shoshoni word pronounced “nambe” or “nambuh” and meaning footprint. She did not weigh in on the Bigfoot connection.

A marauding giant is such a good story that it may never die. It was good enough that Bigfoot was killed, again, in New Mexico, 14 years after he was ventilated in Owyhee County. No word on whether he was able to gasp out his life story that time.

A stature of Bigfoot in Parma.

A stature of Bigfoot in Parma.

Published on March 27, 2022 04:00

March 26, 2022

"Hello Girls" (Tap to read)

From the early days of telephone exchanges, the female operators who helped people place their calls were known as “Hello Girls.” There were frequent stories about them in the newspapers, most often about how they struggled to keep up with some change in the system, or how they were on strike for better wages in some city.

In 1917, a young woman from Emmett learned about a special group of “Hello Girls” she was about to join.

It was a hot August night when Anne Marie Campbell was working a call between two men on a crackly connection. The parties could not clearly hear each other, so she repeated the conversations back to each man so they could take care of business.

Minutes after that call ended, according to a 1984 Idaho Statesman interview with the woman who was now Anne Campbell Atkinson, she got a personal call on the switchboard. It was one of the men she’d just been helping. He said, “Madam, if you are the lady who just assisted with the call to New York, I’d like to hire you for the U.S. Army. I’m a recruiter for General Pershing and your voice is so crisp and clear—would you be willing to go to France as an operator for the Army? Your country needs you.”

And that’s how Atkinson became one of two Army “Hello Girls” from Idaho.

The Army had tried using men in the Signal Corps to operate telephone exchanges, but they did not excel at it. Every switchboard operator in the United States was a woman. Rather than struggle through teaching all the men how to work the system, they recruited women for the job. More than 7,500 volunteered for the first 100 slots. Two hundred twenty-three women—and two men—became Signal Corps Operators.

They were the first group of women to be placed in a combat situation for the United States. Two of them were killed in action.

The operators needed to speak French and English. They were good at their jobs, taking just 10 seconds to connect one party to the next, six times faster than the men they replaced. They connected more than 26 million phone calls.

The women proudly wore Signal Corps uniforms, served under commissioned officers, wore rank insignia and dog tags, took the Army oath, and were subject to court-martial. But when the war was over, they found out they were really “civilian contractors.”

The Army “Hello Girls” were largely forgotten for decades. Then, in 1979 the surviving “Hello Girls,” 19 in all, including Atkinson, who was nearly 88 at the time, received formal U.S. Army Honorable Discharges presented by the senior Army officer of the state where they resided. Accompanying Atkinson’s discharge was a letter that read “…whose service in World War I encompassed the period November 28, 1917, through June 30, 1919, be considered active military service the U.S. Armed Forces for the purpose of all laws administered by the Veterans; Administration.”

In 2021, legislation passed Congress to award a single Congressional Gold Medal to the Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit.

In anticipation of the question, I know little about the second Idaho “Hello Girl.” Her name was Hazel May Hammond and I believe she was from Sandpoint.

“Hello Girls” from World War I. Harris & Ewing, photographer, Library of Congress.

“Hello Girls” from World War I. Harris & Ewing, photographer, Library of Congress.

In 1917, a young woman from Emmett learned about a special group of “Hello Girls” she was about to join.

It was a hot August night when Anne Marie Campbell was working a call between two men on a crackly connection. The parties could not clearly hear each other, so she repeated the conversations back to each man so they could take care of business.

Minutes after that call ended, according to a 1984 Idaho Statesman interview with the woman who was now Anne Campbell Atkinson, she got a personal call on the switchboard. It was one of the men she’d just been helping. He said, “Madam, if you are the lady who just assisted with the call to New York, I’d like to hire you for the U.S. Army. I’m a recruiter for General Pershing and your voice is so crisp and clear—would you be willing to go to France as an operator for the Army? Your country needs you.”

And that’s how Atkinson became one of two Army “Hello Girls” from Idaho.

The Army had tried using men in the Signal Corps to operate telephone exchanges, but they did not excel at it. Every switchboard operator in the United States was a woman. Rather than struggle through teaching all the men how to work the system, they recruited women for the job. More than 7,500 volunteered for the first 100 slots. Two hundred twenty-three women—and two men—became Signal Corps Operators.

They were the first group of women to be placed in a combat situation for the United States. Two of them were killed in action.

The operators needed to speak French and English. They were good at their jobs, taking just 10 seconds to connect one party to the next, six times faster than the men they replaced. They connected more than 26 million phone calls.

The women proudly wore Signal Corps uniforms, served under commissioned officers, wore rank insignia and dog tags, took the Army oath, and were subject to court-martial. But when the war was over, they found out they were really “civilian contractors.”

The Army “Hello Girls” were largely forgotten for decades. Then, in 1979 the surviving “Hello Girls,” 19 in all, including Atkinson, who was nearly 88 at the time, received formal U.S. Army Honorable Discharges presented by the senior Army officer of the state where they resided. Accompanying Atkinson’s discharge was a letter that read “…whose service in World War I encompassed the period November 28, 1917, through June 30, 1919, be considered active military service the U.S. Armed Forces for the purpose of all laws administered by the Veterans; Administration.”

In 2021, legislation passed Congress to award a single Congressional Gold Medal to the Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit.

In anticipation of the question, I know little about the second Idaho “Hello Girl.” Her name was Hazel May Hammond and I believe she was from Sandpoint.

“Hello Girls” from World War I. Harris & Ewing, photographer, Library of Congress.

“Hello Girls” from World War I. Harris & Ewing, photographer, Library of Congress.

Published on March 26, 2022 04:00

March 25, 2022

Women Writers from Idaho (Tap to read)

There are many exceptional woman writers who are connected to Idaho. Here are some who are native to the state.

Carol Ryrie Brink, who wrote more than 30 juvenile and adult books, including the 1936 Newbury Prize-winning Caddie Woodlawn . Brink was born in Moscow and attended the University of Idaho. She was awarded an honorary doctorate of letters from U of I in 1965, and Brink Hall on the campus is named for her.

Marilynn Robinson, who won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her book Gilead in 2005 was born in Sandpoint. Her book Housekeeping , which is set in Sandpoint, was a Pulitzer finalist in 1982.

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich was born in Sugar City, Idaho. Her history of midwife Martha Ballard, titled The Midwife’s Tale , won a Pulitzer Prize and was later made into a documentary film for the PBS series American Experience. Oddly, she may enjoy more fame for a single line in a scholarly publication than for her prize-winning work. She is remembered for the line, "well-behaved women seldom make history," which came from an article about Puritan funeral services. She would later write a book with that title.

Tara Westover was born in Clifton, Idaho. Her 2018 memoir Educated was on many best book lists, including the New York Time top ten list for the year.

Sarah Palin sold more than two million copies of her book Going Rogue . The former governor of Alaska and vice-presidential candidate was born in Sandpoint. She received her bachelor’s degree in communication with a journalism emphasis from the University of Idaho in 1987.

Emily Ruskovich grew up in the panhandle of Idaho on Hoo Doo Mountain. She now teaches at Boise State University. Her 2017 novel, Idaho , was critically acclaimed.

Elaine Ambrose grew up on a potato farm near Wendell. She is best known for her eight books of humor and recently released a memoir called Frozen Dinners, A Memoir of a Fractured Family .

Sister Mary Alfreda Elsensohn (1897-1989) was born in Grangeville, Idaho and she was professed as a Benedictine sister at the Monastery of St. Gertrude in 1916. She was educated at Washington State University, Gonzaga University, and University of Idaho. Her best-known book is Polly Bemis: Idaho County’s Most Romantic Character . Sister Elsensohn created the museum at St. Gertrudes near Cottonwood. The Idaho Humanaties Council and the Idaho State Historical Society give an annual award in her name for Idaho museums.

Jacquie Rogers, born on a farm near Homedale, writes Western humor and Western romance, for which she has won several prizes. Go to any of her books on Amazon, such as Sidetracked in Silver City , and click on her name for a complete list.

Idahoan Carol Ryrie Brink received a Newberry Award for her book Caddie Woodlawn.

Idahoan Carol Ryrie Brink received a Newberry Award for her book Caddie Woodlawn.

Carol Ryrie Brink, who wrote more than 30 juvenile and adult books, including the 1936 Newbury Prize-winning Caddie Woodlawn . Brink was born in Moscow and attended the University of Idaho. She was awarded an honorary doctorate of letters from U of I in 1965, and Brink Hall on the campus is named for her.

Marilynn Robinson, who won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her book Gilead in 2005 was born in Sandpoint. Her book Housekeeping , which is set in Sandpoint, was a Pulitzer finalist in 1982.

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich was born in Sugar City, Idaho. Her history of midwife Martha Ballard, titled The Midwife’s Tale , won a Pulitzer Prize and was later made into a documentary film for the PBS series American Experience. Oddly, she may enjoy more fame for a single line in a scholarly publication than for her prize-winning work. She is remembered for the line, "well-behaved women seldom make history," which came from an article about Puritan funeral services. She would later write a book with that title.

Tara Westover was born in Clifton, Idaho. Her 2018 memoir Educated was on many best book lists, including the New York Time top ten list for the year.

Sarah Palin sold more than two million copies of her book Going Rogue . The former governor of Alaska and vice-presidential candidate was born in Sandpoint. She received her bachelor’s degree in communication with a journalism emphasis from the University of Idaho in 1987.

Emily Ruskovich grew up in the panhandle of Idaho on Hoo Doo Mountain. She now teaches at Boise State University. Her 2017 novel, Idaho , was critically acclaimed.

Elaine Ambrose grew up on a potato farm near Wendell. She is best known for her eight books of humor and recently released a memoir called Frozen Dinners, A Memoir of a Fractured Family .

Sister Mary Alfreda Elsensohn (1897-1989) was born in Grangeville, Idaho and she was professed as a Benedictine sister at the Monastery of St. Gertrude in 1916. She was educated at Washington State University, Gonzaga University, and University of Idaho. Her best-known book is Polly Bemis: Idaho County’s Most Romantic Character . Sister Elsensohn created the museum at St. Gertrudes near Cottonwood. The Idaho Humanaties Council and the Idaho State Historical Society give an annual award in her name for Idaho museums.

Jacquie Rogers, born on a farm near Homedale, writes Western humor and Western romance, for which she has won several prizes. Go to any of her books on Amazon, such as Sidetracked in Silver City , and click on her name for a complete list.

Idahoan Carol Ryrie Brink received a Newberry Award for her book Caddie Woodlawn.

Idahoan Carol Ryrie Brink received a Newberry Award for her book Caddie Woodlawn.

Published on March 25, 2022 04:00

March 24, 2022

Those Confusing Camas Prairies (Tap to read)

Not that Camas Prairie, the other one

After you’ve topped White Bird Pass, look to your left as you enter the rolling farm country around Grangeville. If you’re there in the early spring you can see patches of blue sometimes so thick they look like rippling ponds. If you’re paying attention you might pull over and read the Idaho Historical Society marker that explains that swatch of color. Camas. The flowering root was a key part of the diet of the Nez Perce.

If you’re a fan of historical markers, you probably already stopped at the one part-way up the steep White Bird grade that marks the beginning of the Nez Perce War. The first shots in that months-long running battle were fired from the top of a low hill as the Indians created a diversion there that allowed Chief Joseph and his people, who were camped on the prairie above, to slip away from soldiers.

When we talk about Camas Prairie, we could be talking about that one. Or we could be talking about the other Camas Prairie near Fairfield. It wasn’t part of the Nez Perce War, but it was the site of a war over the edible bulb itself, just one year later.

Farmers and ranchers were encroaching on land promised to the Bannock Tribe in 1878, and no one took the Tribe’s complaints seriously. The dispute turned into a war when hogs were found rooting in the camas fields. One can imagine the seething anger of the Bannocks when they saw pigs tearing up the plants that had been a staple for them for time beyond memory.

The Indians went on a rampage, stealing cattle and horses, attacking and burning a wagon train, and sinking the ferry at Glenn’s Ferry. The Bannocks joined up with Paiutes pillaging across southeastern Oregon. Troops pursued them and the Indians suffered a final defeat in the Blue Mountains, though small raiding parties trickled back into Idaho stirring up trouble well into the fall.

There’s a historical marker about the Bannock War on U.S. 20 near Hill City.

So, now we know there are two… Wait. There’s ANOTHER historical marker on Idaho 62 between Craigmont and Nez Perce that talks about THAT Camas Prairie. Lalia Boone, in her book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary, says that “Camas as a place name occurs throughout Idaho,” and doesn’t even bother to count up all the prairies and creeks so named.

If you’re still confused just know that camas is a beautiful flower that has been a key part of the unwritten and written history of this place we call Idaho.

After you’ve topped White Bird Pass, look to your left as you enter the rolling farm country around Grangeville. If you’re there in the early spring you can see patches of blue sometimes so thick they look like rippling ponds. If you’re paying attention you might pull over and read the Idaho Historical Society marker that explains that swatch of color. Camas. The flowering root was a key part of the diet of the Nez Perce.

If you’re a fan of historical markers, you probably already stopped at the one part-way up the steep White Bird grade that marks the beginning of the Nez Perce War. The first shots in that months-long running battle were fired from the top of a low hill as the Indians created a diversion there that allowed Chief Joseph and his people, who were camped on the prairie above, to slip away from soldiers.

When we talk about Camas Prairie, we could be talking about that one. Or we could be talking about the other Camas Prairie near Fairfield. It wasn’t part of the Nez Perce War, but it was the site of a war over the edible bulb itself, just one year later.

Farmers and ranchers were encroaching on land promised to the Bannock Tribe in 1878, and no one took the Tribe’s complaints seriously. The dispute turned into a war when hogs were found rooting in the camas fields. One can imagine the seething anger of the Bannocks when they saw pigs tearing up the plants that had been a staple for them for time beyond memory.

The Indians went on a rampage, stealing cattle and horses, attacking and burning a wagon train, and sinking the ferry at Glenn’s Ferry. The Bannocks joined up with Paiutes pillaging across southeastern Oregon. Troops pursued them and the Indians suffered a final defeat in the Blue Mountains, though small raiding parties trickled back into Idaho stirring up trouble well into the fall.

There’s a historical marker about the Bannock War on U.S. 20 near Hill City.

So, now we know there are two… Wait. There’s ANOTHER historical marker on Idaho 62 between Craigmont and Nez Perce that talks about THAT Camas Prairie. Lalia Boone, in her book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary, says that “Camas as a place name occurs throughout Idaho,” and doesn’t even bother to count up all the prairies and creeks so named.

If you’re still confused just know that camas is a beautiful flower that has been a key part of the unwritten and written history of this place we call Idaho.

Published on March 24, 2022 04:00

March 23, 2022

Idaho City's Burning Habit (Tap to read)

Idaho city had a habit of burning. This wasn’t unusual for mining towns. They were initially mainly built of lumber without a thought given to brick. When a mining settlement sprang up, its builders knew there was a very good chance it would be a temporary town.

The buildings of Idaho City were heated by stoves and fireplaces and lit by candles and lanterns. All those open flames were ready to snatch a dry curtain or a splash of grease from a frying pan. Everyone who lived there did their best to keep the smoke contained. Still, fires from heating and cooking were quietly coating the insides of cabins and commercial buildings with creosote, making them even more explosive.

On the 18th of May, 1865, residents of Boise noticed a glow from the northeast one evening. Speculation was that it was either Idaho City or Placerville burning. Early the following day, word started coming from businessmen arriving in Boise that it was Idaho City in ashes.

A few minutes before ten in the evening, the alarm spread that a fire had started on the second floor of a hurdy-gurdy dance hall and leaped to the rear of the City Hotel.

“The flames spread with the most astonishing rapidity,” according to the Idaho Statesman. “The town was composed of buildings made exclusively of pine inch boards, and in some cases shakes, covered with cotton lining and paper, to which was added the usual coating of lamp smoke so that it burned almost like a train of powder.”

The mining town had experienced a rash of small fires preceding the big blaze. This was viewed with suspicion since “As soon as the alarm became general, thousands of men could be seen running in all directions with one or two sacks of flour, a box of candles, a bundle of clothing, or anything that suited them.”

A witness remarked that “it was stealing on the grandest scale ever he dreamed of.”

The thieves were loosely organized. One or two hundred of them would gather store contents in a pile away from the burning town, appearing to help the merchants. Then, on a signal, they grabbed whatever they could and lit out.

Every hotel in the city was destroyed, along with most of the stores. Some merchants had fireproof cellars so they could quickly get back to business. By the next day, vendors were clearing away rubble so that a new town could spring up from the ashes.

The vibrant little city began to bustle again only to see a reprise of the disaster in May 1867, two years to the day from the first Idaho City fire.

The Hook and Ladder Company rolled out at noon on the report of flames in the roof of Cody’s saloon.

Despite the efforts of the firefighters and heroic citizens, every building on both sides of Main Street burned down, as did those for blocks around. The courthouse, Masonic Hall, the Catholic church, and the newspaper office were all gone. In addition, dozens of buildings burned, including Heineman and Issacs Bros bricks, touted for their fireproof properties.

Three days later, the Idaho Statesman reported that “as we go to press, all over the burnt district lumber for new buildings is to be seen, houses are rapidly going up, and the genuine “nil desperandum” determination of the brave-souled people is on every side and in every way admirably manifested.”

Better buildings went up after the second fire in two years. Several other fires broke out in succeeding decades but were contained to a building or two, leaving the bulk of Idaho City a place where one can see and touch the history of mining even today.

Idaho City circa 1895.

Idaho City circa 1895.

The buildings of Idaho City were heated by stoves and fireplaces and lit by candles and lanterns. All those open flames were ready to snatch a dry curtain or a splash of grease from a frying pan. Everyone who lived there did their best to keep the smoke contained. Still, fires from heating and cooking were quietly coating the insides of cabins and commercial buildings with creosote, making them even more explosive.

On the 18th of May, 1865, residents of Boise noticed a glow from the northeast one evening. Speculation was that it was either Idaho City or Placerville burning. Early the following day, word started coming from businessmen arriving in Boise that it was Idaho City in ashes.

A few minutes before ten in the evening, the alarm spread that a fire had started on the second floor of a hurdy-gurdy dance hall and leaped to the rear of the City Hotel.

“The flames spread with the most astonishing rapidity,” according to the Idaho Statesman. “The town was composed of buildings made exclusively of pine inch boards, and in some cases shakes, covered with cotton lining and paper, to which was added the usual coating of lamp smoke so that it burned almost like a train of powder.”

The mining town had experienced a rash of small fires preceding the big blaze. This was viewed with suspicion since “As soon as the alarm became general, thousands of men could be seen running in all directions with one or two sacks of flour, a box of candles, a bundle of clothing, or anything that suited them.”

A witness remarked that “it was stealing on the grandest scale ever he dreamed of.”

The thieves were loosely organized. One or two hundred of them would gather store contents in a pile away from the burning town, appearing to help the merchants. Then, on a signal, they grabbed whatever they could and lit out.

Every hotel in the city was destroyed, along with most of the stores. Some merchants had fireproof cellars so they could quickly get back to business. By the next day, vendors were clearing away rubble so that a new town could spring up from the ashes.

The vibrant little city began to bustle again only to see a reprise of the disaster in May 1867, two years to the day from the first Idaho City fire.

The Hook and Ladder Company rolled out at noon on the report of flames in the roof of Cody’s saloon.

Despite the efforts of the firefighters and heroic citizens, every building on both sides of Main Street burned down, as did those for blocks around. The courthouse, Masonic Hall, the Catholic church, and the newspaper office were all gone. In addition, dozens of buildings burned, including Heineman and Issacs Bros bricks, touted for their fireproof properties.

Three days later, the Idaho Statesman reported that “as we go to press, all over the burnt district lumber for new buildings is to be seen, houses are rapidly going up, and the genuine “nil desperandum” determination of the brave-souled people is on every side and in every way admirably manifested.”

Better buildings went up after the second fire in two years. Several other fires broke out in succeeding decades but were contained to a building or two, leaving the bulk of Idaho City a place where one can see and touch the history of mining even today.

Idaho City circa 1895.

Idaho City circa 1895.

Published on March 23, 2022 04:00

March 22, 2022

Oceanfront Property, Riggins (Tap to read0

If you think history doesn’t change, you’re just not paying attention. We learn things all the time that change our interpretation of history. Geology, though, that’s something you can count on.

Well…

Geologists are learning all the time, too. As certifiable human beings, they occasionally make mistakes and frequently disagree with one another.

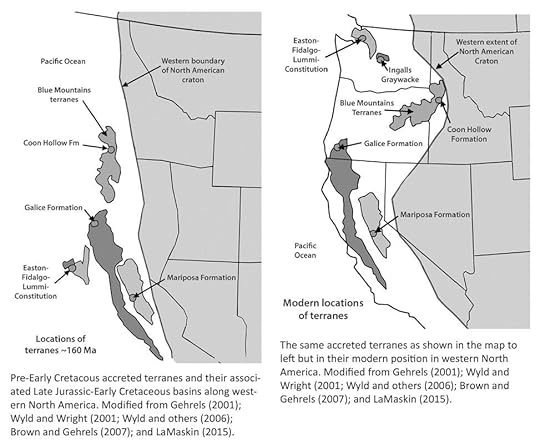

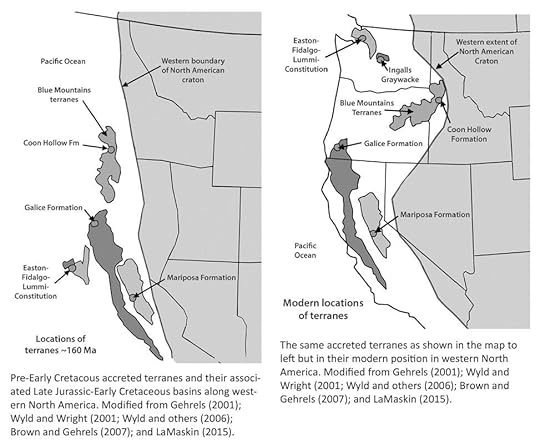

In my 1990 book, Idaho Snapshots, I joked about oceanfront property in Riggins, because at one time—not exactly last week—the area around Riggins would have overlooked the Pacific Ocean. This was a long time ago, in the Middle Permian to Early Cretaceous periods. I noted that what is now Washington and Oregon would have been an island before tectonic plate movement kissed that prehistorical land into what would become Idaho.

Lands roughly west of Riggins along a north-south squiggly line (not an official term of geology) from Alaska to Mexico did form at different times, play their roles as islands, then snuggle up against the North American continent, adding much beloved land to these United States, including California (see graphic).

Most of these islands were formed by volcanic activity or started as mountain ranges beneath the Pacific. They rode oceanic plates on their journey to their present position. The result is called accreted terrane, meaning that land masses formed somewhere else found a different home. Geologists generally agree that a wide swath of the west coast is accreted terrane. They disagree on exactly when and how it all came together.

Evidence that those islands piled up against the rest of the continent is on display in the Riggins area. The photo below, generously contributed by Terry Maley from his book Idaho Geology, shows where two radically different kinds of rocks are squished side-by-side to form part of what we call Idaho.

Well…

Geologists are learning all the time, too. As certifiable human beings, they occasionally make mistakes and frequently disagree with one another.

In my 1990 book, Idaho Snapshots, I joked about oceanfront property in Riggins, because at one time—not exactly last week—the area around Riggins would have overlooked the Pacific Ocean. This was a long time ago, in the Middle Permian to Early Cretaceous periods. I noted that what is now Washington and Oregon would have been an island before tectonic plate movement kissed that prehistorical land into what would become Idaho.

Lands roughly west of Riggins along a north-south squiggly line (not an official term of geology) from Alaska to Mexico did form at different times, play their roles as islands, then snuggle up against the North American continent, adding much beloved land to these United States, including California (see graphic).

Most of these islands were formed by volcanic activity or started as mountain ranges beneath the Pacific. They rode oceanic plates on their journey to their present position. The result is called accreted terrane, meaning that land masses formed somewhere else found a different home. Geologists generally agree that a wide swath of the west coast is accreted terrane. They disagree on exactly when and how it all came together.

Evidence that those islands piled up against the rest of the continent is on display in the Riggins area. The photo below, generously contributed by Terry Maley from his book Idaho Geology, shows where two radically different kinds of rocks are squished side-by-side to form part of what we call Idaho.

Published on March 22, 2022 04:00

March 21, 2022

Not that Hemingway (Tap to read)

That beep, beep, beep you hear is the sound of me backing into this story. It’s about Hemingway Butte, which today is an off-highway vehicle play area managed by the Boise District Bureau of Reclamation. It includes a popular trail system and steep hillsides where OHVs and motorbikes defy gravity for a few seconds courtesy of two-cycle engines.

Hemingway Butte is about three miles southwest of Walter’s Ferry, which itself is about 15 miles south of Nampa. Beep, beep, beep.

Walters Ferry wasn’t always called that. It became Walter’s Ferry when Lewellyn R. Walter bought out his partner’s share of the ferry business in 1886. Previous owners had been John Fruit, George Blankenbecker, John Morgan, Leonard Fuqa, a Mr. Boon, Samuel Neeley, Perry Munday, Robert Duncan, and Reese Miles. But, beep, beep, we must back up to Munday for this story, because the drama took place when it was called Munday’s Ferry.

It was at Munday’s Ferry that the stage came thundering up from the south in August of 1878, its driver mortally wounded. Indians were chasing the stage and directing bullets at it. Munday and three soldiers set across the river toward the embattled stage coach, while two other soldier remained on the north side of the Snake to provide cover fire.

The soldiers and Indians exchanged fire for several minutes, according to a report in the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, while the ferry landed and the wounded stagecoach driver “quietly kept his seat, and when the boat touched the bank drove the team up the grade from the river and asked for water.”

Dr. W.W. McKay was dispatched from Boise to care for the driver. He made the dusty, 30-mile trip by buggy in two and a half hours, only to find when he got there that William Hemingway had breathed his last minutes before.

William Hemingway was the name of the stagecoach driver, and the aforementioned butte was named in his honor, as it was near there that the Indian attack began. Hemingway was buried in Silver City beside his wife and two children who had gone before.

Hemingway Butte is about three miles southwest of Walter’s Ferry, which itself is about 15 miles south of Nampa. Beep, beep, beep.

Walters Ferry wasn’t always called that. It became Walter’s Ferry when Lewellyn R. Walter bought out his partner’s share of the ferry business in 1886. Previous owners had been John Fruit, George Blankenbecker, John Morgan, Leonard Fuqa, a Mr. Boon, Samuel Neeley, Perry Munday, Robert Duncan, and Reese Miles. But, beep, beep, we must back up to Munday for this story, because the drama took place when it was called Munday’s Ferry.

It was at Munday’s Ferry that the stage came thundering up from the south in August of 1878, its driver mortally wounded. Indians were chasing the stage and directing bullets at it. Munday and three soldiers set across the river toward the embattled stage coach, while two other soldier remained on the north side of the Snake to provide cover fire.

The soldiers and Indians exchanged fire for several minutes, according to a report in the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, while the ferry landed and the wounded stagecoach driver “quietly kept his seat, and when the boat touched the bank drove the team up the grade from the river and asked for water.”

Dr. W.W. McKay was dispatched from Boise to care for the driver. He made the dusty, 30-mile trip by buggy in two and a half hours, only to find when he got there that William Hemingway had breathed his last minutes before.

William Hemingway was the name of the stagecoach driver, and the aforementioned butte was named in his honor, as it was near there that the Indian attack began. Hemingway was buried in Silver City beside his wife and two children who had gone before.

Published on March 21, 2022 04:00