Rick Just's Blog, page 99

March 10, 2022

A Disappearing Island (Tap to read)

If you do a Google search for McConnel Island, you’ll come up with a couple of near matches, one for the McConnel Islands, plural, near Antarctica, and one for McConnell Island (note the second L) in the San Jaun Islands in Washington State.

If you’re looking for McConnel Island in Idaho, you’ll have to dig a little deeper. Ask around when you’re in Parma.

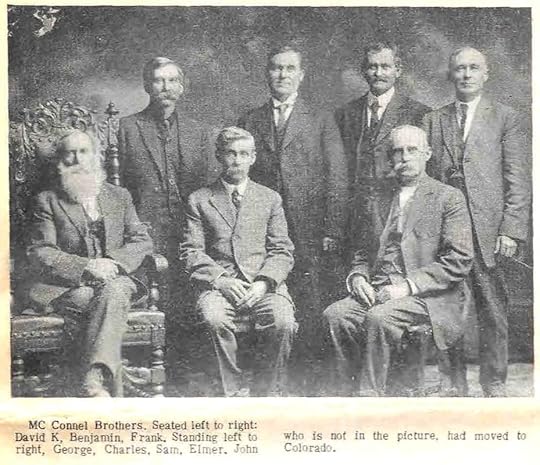

In the early days of settlement in that area the Boise River formed a delta, with two channels, one to the north and one to the south, forming a 4000-acre island. In 1865, David McConnel claimed land on the island and built a home there as a squatter. In 1879 he applied for and received a homestead claim of an additional 160 acres, bringing his ranch to about 500 acres. Other families, including that of David’s brother, Ben, lived there, and it even had a McConnel Island School.

David McConnel had come West in 1862 with a large Oregon Trail wagon train. He acted as a scout for that train. McConnel had 11 siblings, 10 brothers and a sister. Eight of his brothers followed him to the Boise Valley from their home in Iowa.

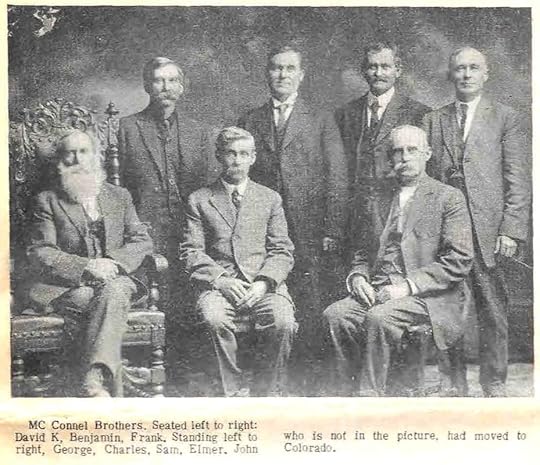

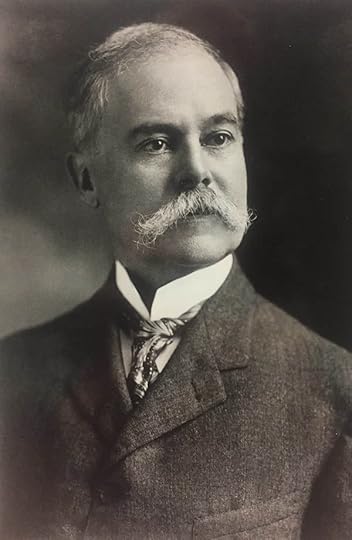

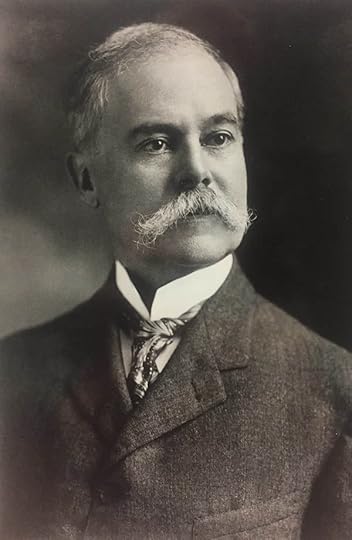

McConnel, who would one day be an Idaho governor, was a vigilante. That word has a negative note to it today, but it was a point of pride for him. It was the beginning of law and order in the area. In writing about his grandfather, Carl Isenberg recalled McConnel saying that “until the committee was formed and operated on several of the rustlers, murderers, etc., no one could feel secure, but that after a few examples, property and individual safety was secure.”

The island became McConnel Island because of David McConnel’s association with it. It ceased being an island when the Ross Fill was built to block off the southern channel of the river to help solve a frequent flooding problem.

Thanks to Merv McConnel for supplying much of the information used for this story.

If you’re looking for McConnel Island in Idaho, you’ll have to dig a little deeper. Ask around when you’re in Parma.

In the early days of settlement in that area the Boise River formed a delta, with two channels, one to the north and one to the south, forming a 4000-acre island. In 1865, David McConnel claimed land on the island and built a home there as a squatter. In 1879 he applied for and received a homestead claim of an additional 160 acres, bringing his ranch to about 500 acres. Other families, including that of David’s brother, Ben, lived there, and it even had a McConnel Island School.

David McConnel had come West in 1862 with a large Oregon Trail wagon train. He acted as a scout for that train. McConnel had 11 siblings, 10 brothers and a sister. Eight of his brothers followed him to the Boise Valley from their home in Iowa.

McConnel, who would one day be an Idaho governor, was a vigilante. That word has a negative note to it today, but it was a point of pride for him. It was the beginning of law and order in the area. In writing about his grandfather, Carl Isenberg recalled McConnel saying that “until the committee was formed and operated on several of the rustlers, murderers, etc., no one could feel secure, but that after a few examples, property and individual safety was secure.”

The island became McConnel Island because of David McConnel’s association with it. It ceased being an island when the Ross Fill was built to block off the southern channel of the river to help solve a frequent flooding problem.

Thanks to Merv McConnel for supplying much of the information used for this story.

Published on March 10, 2022 04:00

March 9, 2022

Poets Laureates (Tap to read)

Poets laureates were frequently mentioned in early newspapers. Most of those stories were about poets in England, where there was a lot of respect for the title because it was bestowed by the royal family. British poets laureate often graced the pages of the Idaho Statesman in the early days. Alfred Austin was a favorite in the 1890s.

The term was loosely thrown around as an honor for those in clubs and organizations where someone would dash off a rhyme from time to time. Often the title was used in jest. The first mention of an Idaho poet laureate was used that way.

On March 25, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran an article with the headline, Poet Laureate of Idaho is on the Job at State House. “The spring poet may be a joke in some quarters,” the article began, “but he is an actual living, glowing reality in Boise, and with the first warm rain that burst the buds of the trees he blossomed forth and has been busily engaged for the past few days distributing his poems about the statehouse.”

The man was allegedly using the pen name Hask Haskell. No further mention of that name every appeared in the paper again.

But in 1923, it finally happened. Gov. C.C. Moore named Irene Welch Grissom (photo) of Idaho Falls Idaho’s first poet laureate. She appeared in stories here and there reading her poems to various groups and releasing new books for many years. Tracking her in a digital search was a little iffy because although everyone seemed to agree on the spelling of her first and last name, her middle name sometimes appeared as Welsh, sometimes Walsh, sometimes Welsch.

Shortly after Idaho named a poet laureate, Wyoming residents decided they needed one. Wyoming Governor W.B. Ross was reluctant to appoint one because he wasn’t sure he had the legal authority. The editor of the Casper Daily Herald was checking into how Idaho had done it, according to a blurb in the Statesman, which quoted Kelly the elevator man at the statehouse as saying “Now I ask you, what have they in Wyoming to muse about ‘cept rattlesnakes, oil and cows?”

So, snark was alive and well in Idaho in 1923.

Irene Welch Grissom was apparently expected to serve as Idaho’s poet laureate for life. She did so for many years until she committed a scandalous crime. In 1948 she moved to (gasp!) California.

So, that year, Gov. C.A. Robbins appointed a committee of writers who would nominate a new poet laureate. They recommended, and Gov. Robbins selected, Sudie Stuart Hager of Kimberly as Idaho’s second poet laureate. There was confusion over her middle name in stories, as well. It sometimes appeared as Stewart.

Hager served until her death in 1982.

So, we had two poet laureates. No more. Today, the Idaho Commission on the Arts selects an Idaho Writer in Residence who serves for three years, receiving a modest stipend.

Here’s a list of the Idaho Poets Laureate and Idaho Writers in Residence to date:

Irene Welsh Grissom (1923-1948, poet laureate)

Sudie Stuart Hager (1949-1982, poet laureate)

Ron McFarland (1984-1985) (first person named Writer-in-Residence)

Robert Wrigley (1986-1987)

Eberle Umbach (1988-1989)

Neidy Messer (1990-1991)

Daryl Jones (1992-1993)

Clay Morgan (1994-1995)

Lance Olsen (1996-1998)

Bill Johnson (1999-2000)

Jim Irons (July 2, 2001-2004)

Kim Barnes (April 2004-2006)

Anthony "Tony" Doerr (July 2007-July 2010)

Brady Udall (July 1, 2010-June 20, 2013)

Dianne Raptosh, (July 2013-June 2016)

Christian Winn (July 2016 to June 2019)

Malia Collins (July 2019 to 2021)

Cmarie Furhman (present)

The term was loosely thrown around as an honor for those in clubs and organizations where someone would dash off a rhyme from time to time. Often the title was used in jest. The first mention of an Idaho poet laureate was used that way.

On March 25, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran an article with the headline, Poet Laureate of Idaho is on the Job at State House. “The spring poet may be a joke in some quarters,” the article began, “but he is an actual living, glowing reality in Boise, and with the first warm rain that burst the buds of the trees he blossomed forth and has been busily engaged for the past few days distributing his poems about the statehouse.”

The man was allegedly using the pen name Hask Haskell. No further mention of that name every appeared in the paper again.

But in 1923, it finally happened. Gov. C.C. Moore named Irene Welch Grissom (photo) of Idaho Falls Idaho’s first poet laureate. She appeared in stories here and there reading her poems to various groups and releasing new books for many years. Tracking her in a digital search was a little iffy because although everyone seemed to agree on the spelling of her first and last name, her middle name sometimes appeared as Welsh, sometimes Walsh, sometimes Welsch.

Shortly after Idaho named a poet laureate, Wyoming residents decided they needed one. Wyoming Governor W.B. Ross was reluctant to appoint one because he wasn’t sure he had the legal authority. The editor of the Casper Daily Herald was checking into how Idaho had done it, according to a blurb in the Statesman, which quoted Kelly the elevator man at the statehouse as saying “Now I ask you, what have they in Wyoming to muse about ‘cept rattlesnakes, oil and cows?”

So, snark was alive and well in Idaho in 1923.

Irene Welch Grissom was apparently expected to serve as Idaho’s poet laureate for life. She did so for many years until she committed a scandalous crime. In 1948 she moved to (gasp!) California.

So, that year, Gov. C.A. Robbins appointed a committee of writers who would nominate a new poet laureate. They recommended, and Gov. Robbins selected, Sudie Stuart Hager of Kimberly as Idaho’s second poet laureate. There was confusion over her middle name in stories, as well. It sometimes appeared as Stewart.

Hager served until her death in 1982.

So, we had two poet laureates. No more. Today, the Idaho Commission on the Arts selects an Idaho Writer in Residence who serves for three years, receiving a modest stipend.

Here’s a list of the Idaho Poets Laureate and Idaho Writers in Residence to date:

Irene Welsh Grissom (1923-1948, poet laureate)

Sudie Stuart Hager (1949-1982, poet laureate)

Ron McFarland (1984-1985) (first person named Writer-in-Residence)

Robert Wrigley (1986-1987)

Eberle Umbach (1988-1989)

Neidy Messer (1990-1991)

Daryl Jones (1992-1993)

Clay Morgan (1994-1995)

Lance Olsen (1996-1998)

Bill Johnson (1999-2000)

Jim Irons (July 2, 2001-2004)

Kim Barnes (April 2004-2006)

Anthony "Tony" Doerr (July 2007-July 2010)

Brady Udall (July 1, 2010-June 20, 2013)

Dianne Raptosh, (July 2013-June 2016)

Christian Winn (July 2016 to June 2019)

Malia Collins (July 2019 to 2021)

Cmarie Furhman (present)

Published on March 09, 2022 04:00

March 8, 2022

The Georgie Oakes (Tap to read)

I’d seen this picture, from the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection, many times over the years but missed one interesting detail until recently. It’s the steamboat Georgie Oakes docked at Mission Landing near the Cataldo Mission of the Sacred Heart. The picture was taken around 1891.

Mission Landing was as far up the Coeur d’Alene River as you could get with a big boat. Supplies for the mines were off-loaded here onto a narrow-gauge railway (just visible in the lower right) that took them to the Coeur d’Alene Mining District, Kellogg, Wallace, and Murray. Ore went the other direction, down the railway to the landing and by boat from there.

What I hadn’t noticed before, until I read the picture description furnished by the Idaho State Historical Society, was that the “dock” the Georgie Oakes is tied up to is the cannibalized hull of the steamer Coeur d’Alene, the boat it replaced on the river.

Today we have a romanticized view of those often-elegant looking boats that plied the waters of Lake Coeur d’Alene, and the Coeur d’Alene and St. Joe rivers. In their day, they were working boats that held little charm for most people. None of the many steamers that worked the waters are around still today. No one bothered to save even one. Most burned accidentally, or were scuttled. One went down as the center point of the Fourth of July celebration in 1927. People looked on while the burning boat sank into the lake, sputtering and smoking until it was only a memory. That was the fate of the grand lady of the lakes, the Georgie Oakes.

Mission Landing was as far up the Coeur d’Alene River as you could get with a big boat. Supplies for the mines were off-loaded here onto a narrow-gauge railway (just visible in the lower right) that took them to the Coeur d’Alene Mining District, Kellogg, Wallace, and Murray. Ore went the other direction, down the railway to the landing and by boat from there.

What I hadn’t noticed before, until I read the picture description furnished by the Idaho State Historical Society, was that the “dock” the Georgie Oakes is tied up to is the cannibalized hull of the steamer Coeur d’Alene, the boat it replaced on the river.

Today we have a romanticized view of those often-elegant looking boats that plied the waters of Lake Coeur d’Alene, and the Coeur d’Alene and St. Joe rivers. In their day, they were working boats that held little charm for most people. None of the many steamers that worked the waters are around still today. No one bothered to save even one. Most burned accidentally, or were scuttled. One went down as the center point of the Fourth of July celebration in 1927. People looked on while the burning boat sank into the lake, sputtering and smoking until it was only a memory. That was the fate of the grand lady of the lakes, the Georgie Oakes.

Published on March 08, 2022 04:00

March 7, 2022

Boise's Bat Wing Building (Tap to read)

A building doesn’t have to be large to be architecturally significant. A gas station built in 1964 on State Street in Boise has made a big splash recently among people who appreciate mid-century modern architecture.

According to Dan Everheart of the Idaho State Historic Preservation Office, In 1956, Clarence Reinhardt, the corporate architect for Phillips Petroleum, began to experiment with dramatic V-shaped canopies at the company’s branded filling stations. By 1960, a harlequin paint scheme and Reinhardt’s “bat wing” canopy were launched as the “New Look” of the Phillips architectural brand. Phillips 66 station in Boise was one example.

State Street is also SH 44, so the station was called the Forty-Four and Sixty-Six Service Station. It only lasted as a gas station for about ten years. Milan and Blazena Kral purchased the building in 1977 and operated a German car repair shop there for 20 years. The Krals were defectors from Soviet Czechoslovakia who made a new life in Boise. Their son and daughter-in-law rehabilitated the building in 2020.

The building now houses Design Vim, a sustainable design company.

Preservation Idaho gave an Orchid award to the redevelopment project in 2020. It's also on the cover of a recent report from the National Park Service about the success of the Federal Historic Tax Credit program. The owners of the building received the tax credit for restoration. You can read more about it by downloading the federal report here.

The old Phillips 66 on State Street in Boise is now Design Vim.

The old Phillips 66 on State Street in Boise is now Design Vim.

According to Dan Everheart of the Idaho State Historic Preservation Office, In 1956, Clarence Reinhardt, the corporate architect for Phillips Petroleum, began to experiment with dramatic V-shaped canopies at the company’s branded filling stations. By 1960, a harlequin paint scheme and Reinhardt’s “bat wing” canopy were launched as the “New Look” of the Phillips architectural brand. Phillips 66 station in Boise was one example.

State Street is also SH 44, so the station was called the Forty-Four and Sixty-Six Service Station. It only lasted as a gas station for about ten years. Milan and Blazena Kral purchased the building in 1977 and operated a German car repair shop there for 20 years. The Krals were defectors from Soviet Czechoslovakia who made a new life in Boise. Their son and daughter-in-law rehabilitated the building in 2020.

The building now houses Design Vim, a sustainable design company.

Preservation Idaho gave an Orchid award to the redevelopment project in 2020. It's also on the cover of a recent report from the National Park Service about the success of the Federal Historic Tax Credit program. The owners of the building received the tax credit for restoration. You can read more about it by downloading the federal report here.

The old Phillips 66 on State Street in Boise is now Design Vim.

The old Phillips 66 on State Street in Boise is now Design Vim.

Published on March 07, 2022 04:00

March 6, 2022

Fred Dubois and the Test Oath (Tap to read)

In 1882, Fred T. Dubois might be found crawling beneath a house searching for a secret compartment where a polygamist was hiding. In 1887 he could be found in Congress, representing Idaho Territory. There was a solid link between the two activities.

Fred Dubois came to Idaho Territory in 1880 with his brother Dr. Jesse Dubois, Jr, who had been appointed physician at the Fort Hall Indian Agency. The younger Dubois—Fred was only 29—spent a few months as a cattle drive cowboy before he got into his preferred career, politics. The Dubois brothers grew up in Illinois. Their parents were friends with Abraham Lincoln. So, Fred Dubois had political connections in Washington, D.C. That smoothed the way for him to become U.S. Marshall for Idaho Territory, a position for which he had no discernable qualifications.

Nevertheless, he embraced the job, especially when it came to arresting Mormon polygamists. He was frustrated, though, because juries of their peers routinely set the polygamists free.

Dubois pushed to get a bill passed in the territorial legislature that would allow him to bring men with multiple wives to justice, even though polygamy was already illegal under federal law. The result was the “test oath.” Under the terms of the law territorial officials could require an oath of nonsupport of “celestial marriage” before a person could vote, hold office, or serve on a jury. Suddenly a jury of a polygamist’s peers could not include members of the LDS faith. The prohibition was soon ensconced in the Idaho constitution. It was enforced for only a few years, but remained in the constitution until 1982.

It wasn’t polygamy itself that Dubois abhorred, or the Mormon faith. It was the political power of Mormons he wanted to quell. They tended to vote in a block. In 1880, for instance, every vote in Bear Lake County was for a Democrat.

Politics was very much Fred T. Dubois’ game. He became popular with non-Mormons statewide, and since Mormons could no longer vote, he easily won election as a territorial delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1887. He was elected to the Senate after Idaho became a state, serving from 1901 to 1907.

Thanks to Randy Stapilus for his book Jerks in Idaho History , and Deana Lowe Jensen for her book about Fred T. Dubois, Let the Eagle Scream . I depended heavily on both for this post.

Fred Dubois came to Idaho Territory in 1880 with his brother Dr. Jesse Dubois, Jr, who had been appointed physician at the Fort Hall Indian Agency. The younger Dubois—Fred was only 29—spent a few months as a cattle drive cowboy before he got into his preferred career, politics. The Dubois brothers grew up in Illinois. Their parents were friends with Abraham Lincoln. So, Fred Dubois had political connections in Washington, D.C. That smoothed the way for him to become U.S. Marshall for Idaho Territory, a position for which he had no discernable qualifications.

Nevertheless, he embraced the job, especially when it came to arresting Mormon polygamists. He was frustrated, though, because juries of their peers routinely set the polygamists free.

Dubois pushed to get a bill passed in the territorial legislature that would allow him to bring men with multiple wives to justice, even though polygamy was already illegal under federal law. The result was the “test oath.” Under the terms of the law territorial officials could require an oath of nonsupport of “celestial marriage” before a person could vote, hold office, or serve on a jury. Suddenly a jury of a polygamist’s peers could not include members of the LDS faith. The prohibition was soon ensconced in the Idaho constitution. It was enforced for only a few years, but remained in the constitution until 1982.

It wasn’t polygamy itself that Dubois abhorred, or the Mormon faith. It was the political power of Mormons he wanted to quell. They tended to vote in a block. In 1880, for instance, every vote in Bear Lake County was for a Democrat.

Politics was very much Fred T. Dubois’ game. He became popular with non-Mormons statewide, and since Mormons could no longer vote, he easily won election as a territorial delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1887. He was elected to the Senate after Idaho became a state, serving from 1901 to 1907.

Thanks to Randy Stapilus for his book Jerks in Idaho History , and Deana Lowe Jensen for her book about Fred T. Dubois, Let the Eagle Scream . I depended heavily on both for this post.

Published on March 06, 2022 04:00

March 5, 2022

Nell Shipman (Tap to read)

Nell Shipman was a Canadian actress, author, screenwriter, producer, director, and animal rights activist who made her mark in Idaho, though her contributions to the art of filmmaking would not be recognized until decades after her death.

Shipman was the screenwriter, director, star, and stunt woman in her movies. They featured strong women more likely to save men from danger than the other way around. Her pioneering included what by today’s standards would be a PG-rated nude scene of her showering beneath a waterfall. The movie was hyped with the slogan, “Is the nude, rude?” Shipman Point in Priest Lake State Park is named for this early film pioneer.

Tom Trusky, who “rediscovered” Shipman in his scholarly research, wrote the following about Nell in 2008 :“In the summer of 1922, Nell Shipman Productions moved from Spokane, Washington to its final residence, Priest Lake, in the Panhandle of North Idaho. There, the company would complete the shooting of what historians and silent film fans term Shipman’s magnum opus, The Grub-Stake (1922), and four noteworthy two-reel films in a series titled The Little Dramas of the Big Places (1924). Although Shipman and her crew could not have known it, this was sundown for the democratic, “Indie,” one-girl-do-it-all days of cinema. Dawn of the next day, the studio system and male movie moguls would define for decades what Hollywood meant, prior to the advent of television, Gloria Steinem, Sundance, satellite feeds, and online downloads.”

Trusky located all of the “lost” Shipman films, published her autobiography The Silent Screen and My Talking Heart , and established Boise State University as a major archival site for her work.

Many of her films are available online. Revival of interest in Shipman resulted in an award-winning 2015 documentary called Girl From God’s Country,” by Boise filmmaker Karen Day.

Nell Shipman on location overlooking Priest Lake.

Nell Shipman on location overlooking Priest Lake.

Shipman was the screenwriter, director, star, and stunt woman in her movies. They featured strong women more likely to save men from danger than the other way around. Her pioneering included what by today’s standards would be a PG-rated nude scene of her showering beneath a waterfall. The movie was hyped with the slogan, “Is the nude, rude?” Shipman Point in Priest Lake State Park is named for this early film pioneer.

Tom Trusky, who “rediscovered” Shipman in his scholarly research, wrote the following about Nell in 2008 :“In the summer of 1922, Nell Shipman Productions moved from Spokane, Washington to its final residence, Priest Lake, in the Panhandle of North Idaho. There, the company would complete the shooting of what historians and silent film fans term Shipman’s magnum opus, The Grub-Stake (1922), and four noteworthy two-reel films in a series titled The Little Dramas of the Big Places (1924). Although Shipman and her crew could not have known it, this was sundown for the democratic, “Indie,” one-girl-do-it-all days of cinema. Dawn of the next day, the studio system and male movie moguls would define for decades what Hollywood meant, prior to the advent of television, Gloria Steinem, Sundance, satellite feeds, and online downloads.”

Trusky located all of the “lost” Shipman films, published her autobiography The Silent Screen and My Talking Heart , and established Boise State University as a major archival site for her work.

Many of her films are available online. Revival of interest in Shipman resulted in an award-winning 2015 documentary called Girl From God’s Country,” by Boise filmmaker Karen Day.

Nell Shipman on location overlooking Priest Lake.

Nell Shipman on location overlooking Priest Lake.

Published on March 05, 2022 04:00

March 4, 2022

A Terrible Tiger Tale (Tap to read)

A Terrible Tiger Tale

I often stagger down the halls of history, careening off the walls and sometimes stumbling into a cobweb-filled room that has been long forgotten. Such was the case recently when I tried to match up a cool photo of a circus parade in Blackfoot with a story from contemporaneous newspapers. It turned out there wasn’t much more to say about the Blackfoot photo but searching for the circus name turned up a story from Twin Falls that is graphic enough for me to warn those who might have delicate constitutions to turn back. Now.

On May 26, 1907 the Sells-Floto Circus set up tents in Twin Falls. They advertised “100 startling, superb, sensational and stupendous surprises.” The number of surprises might have been off a bit, but surprises there were.

The circus had some headliners named Markel and Agnes, a pair of tigers. Handlers were in the process of feeding the big cats when Markel began to beat furiously against the cage door with his front paws. The door gave way and the tiger leapt on the nearest thing that looked like food, a Shetland pony, and began tearing at its neck. The tiger keeper whacked Markel between the eyes with an iron bar. The cat jumped off the little horse and onto the back of a second Shetland. The keeper tried the trick with the bar again, causing the tiger to repeat his retreat, only to leap onto the back of a third pony. A third whack to the face with an iron bar drove the tiger off the Shetland and into the crowd, perhaps not the result the keeper was hoping for.

As the news service story stated, “A panic followed. Women grasped their children and dragged them from the path of the maddened animal.

“The screams of the frightened spectators mingled with the trumpeting of the elephants and the cries of excited animals in the cages.”

Mrs. S. E. Rosell tried to pull her four-year-old daughter, Ruth, out of the way, to no avail. The cat knocked them down. “Holding the mother with his paws the tiger sank his teeth in the neck of the child.”

Local blacksmith J.W. Bell pushed his own family aside then aimed his .32 caliber revolver at the tiger from three feet away. The big cat took six bullets before finally collapsing.

Sadly, Ruth Rosell died from her wounds a couple of hours later.

Devastating as the experience must have been, the circus—the same circus—was back in Twin Falls for another show the following year. You’ve heard the saying, “The show must go on,” right?

UPDATE: Since I first posted this story in 2019, Carol Barret, great-granddaughter of J.W. Bell contacted me with a little more detail about the story.

It seems that the custom of the time regarding firearms was changing. Many venues, including the circus, discouraged sidearms at public gatherings. John Bell “felt naked” without his gun, so he put it on underneath his trousers.

There’s little humor in this story, but one moment of it might have been when Bell ducked behind a tent pole to drop his pants so he could get the pistol out.

The tiger got close enough to Bell that some of the entry wounds showed powder burns.

The owner of the tiger made some noise about suing John Bell for destroying his valuable animal. That was ridiculous on its face, so never happened. I couldn’t track it, but I would be surprised if the family of the girl who died didn’t sue the circus.

Carol Barret said that her great-grandfather had a tiger claw on his watch chain for some years. She heard that a newspaper in Colorado displayed the pelt from the tiger on an office wall. I couldn’t find confirmation of that.

John Bell

John Bell

I often stagger down the halls of history, careening off the walls and sometimes stumbling into a cobweb-filled room that has been long forgotten. Such was the case recently when I tried to match up a cool photo of a circus parade in Blackfoot with a story from contemporaneous newspapers. It turned out there wasn’t much more to say about the Blackfoot photo but searching for the circus name turned up a story from Twin Falls that is graphic enough for me to warn those who might have delicate constitutions to turn back. Now.

On May 26, 1907 the Sells-Floto Circus set up tents in Twin Falls. They advertised “100 startling, superb, sensational and stupendous surprises.” The number of surprises might have been off a bit, but surprises there were.

The circus had some headliners named Markel and Agnes, a pair of tigers. Handlers were in the process of feeding the big cats when Markel began to beat furiously against the cage door with his front paws. The door gave way and the tiger leapt on the nearest thing that looked like food, a Shetland pony, and began tearing at its neck. The tiger keeper whacked Markel between the eyes with an iron bar. The cat jumped off the little horse and onto the back of a second Shetland. The keeper tried the trick with the bar again, causing the tiger to repeat his retreat, only to leap onto the back of a third pony. A third whack to the face with an iron bar drove the tiger off the Shetland and into the crowd, perhaps not the result the keeper was hoping for.

As the news service story stated, “A panic followed. Women grasped their children and dragged them from the path of the maddened animal.

“The screams of the frightened spectators mingled with the trumpeting of the elephants and the cries of excited animals in the cages.”

Mrs. S. E. Rosell tried to pull her four-year-old daughter, Ruth, out of the way, to no avail. The cat knocked them down. “Holding the mother with his paws the tiger sank his teeth in the neck of the child.”

Local blacksmith J.W. Bell pushed his own family aside then aimed his .32 caliber revolver at the tiger from three feet away. The big cat took six bullets before finally collapsing.

Sadly, Ruth Rosell died from her wounds a couple of hours later.

Devastating as the experience must have been, the circus—the same circus—was back in Twin Falls for another show the following year. You’ve heard the saying, “The show must go on,” right?

UPDATE: Since I first posted this story in 2019, Carol Barret, great-granddaughter of J.W. Bell contacted me with a little more detail about the story.

It seems that the custom of the time regarding firearms was changing. Many venues, including the circus, discouraged sidearms at public gatherings. John Bell “felt naked” without his gun, so he put it on underneath his trousers.

There’s little humor in this story, but one moment of it might have been when Bell ducked behind a tent pole to drop his pants so he could get the pistol out.

The tiger got close enough to Bell that some of the entry wounds showed powder burns.

The owner of the tiger made some noise about suing John Bell for destroying his valuable animal. That was ridiculous on its face, so never happened. I couldn’t track it, but I would be surprised if the family of the girl who died didn’t sue the circus.

Carol Barret said that her great-grandfather had a tiger claw on his watch chain for some years. She heard that a newspaper in Colorado displayed the pelt from the tiger on an office wall. I couldn’t find confirmation of that.

John Bell

John Bell

Published on March 04, 2022 04:00

March 3, 2022

Cariboo and Caribou County (Tap to read)

There are, occasionally, caribou in Idaho, and not just when Santa is flying over the state and, once again, pointedly skipping MY house. The caribou that wander in and out of Idaho in Boundary County, back and forth across the border with Canada, are the only caribou left in the Lower 48.

Note that the caribou are in Boundary County. Caribou County does not have Caribou and never has in recorded history. So why would you name a county after caribou that never get closer than, say 480 miles away?

Residents are quick to tell you that Caribou County is not named after any sort of reindeer. And they are mostly correct. The county is named after “Carriboo” Jack Fairchild, a miner who was among those who first discovered gold on what is now called Caribou Mountain.

But one must wonder where Carriboo Jack got his name. As it turns out, the inveterate storyteller got his nickname because when questioned about the veracity of one of his stories he would often reply, “It is so, I will let you know I am from Cariboo.”

The Cariboo he was from was a mining district in British Columbia, where Fairchild had also worked a claim. The area retains the spelling, with a single “r” today. Carriboo had the extra “r” in his name because, I don’t know, he deserved it? And why don’t the Canadians spell it caribou?

The county in Idaho was called Carriboo until 1921, when someone decided to “correct” it. Caribou Mountian, Caribou City, and the Caribou National Forest all owe their name to Cariboo Jack, the story teller.

One story he often told was about his origins. “I was born in a blizzard snowdrift in the worst storm ever to hit Canada. I was bathed in a gold pan, suckled by a caribou, wrapped in a buffalo rug, and could whip any grizzly going before I was thirteen. That’s when I left home.” A guy like that can spell his name any way he wants.

Much of this story comes from a piece Ellen Carney wrote for the Caribou County website.

Note that the caribou are in Boundary County. Caribou County does not have Caribou and never has in recorded history. So why would you name a county after caribou that never get closer than, say 480 miles away?

Residents are quick to tell you that Caribou County is not named after any sort of reindeer. And they are mostly correct. The county is named after “Carriboo” Jack Fairchild, a miner who was among those who first discovered gold on what is now called Caribou Mountain.

But one must wonder where Carriboo Jack got his name. As it turns out, the inveterate storyteller got his nickname because when questioned about the veracity of one of his stories he would often reply, “It is so, I will let you know I am from Cariboo.”

The Cariboo he was from was a mining district in British Columbia, where Fairchild had also worked a claim. The area retains the spelling, with a single “r” today. Carriboo had the extra “r” in his name because, I don’t know, he deserved it? And why don’t the Canadians spell it caribou?

The county in Idaho was called Carriboo until 1921, when someone decided to “correct” it. Caribou Mountian, Caribou City, and the Caribou National Forest all owe their name to Cariboo Jack, the story teller.

One story he often told was about his origins. “I was born in a blizzard snowdrift in the worst storm ever to hit Canada. I was bathed in a gold pan, suckled by a caribou, wrapped in a buffalo rug, and could whip any grizzly going before I was thirteen. That’s when I left home.” A guy like that can spell his name any way he wants.

Much of this story comes from a piece Ellen Carney wrote for the Caribou County website.

Published on March 03, 2022 04:00

March 2, 2022

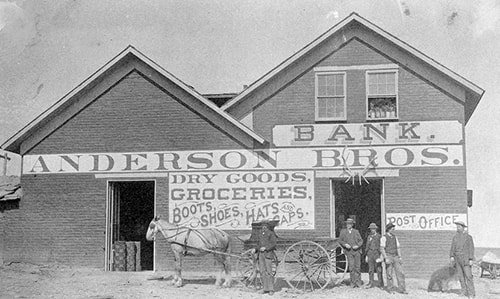

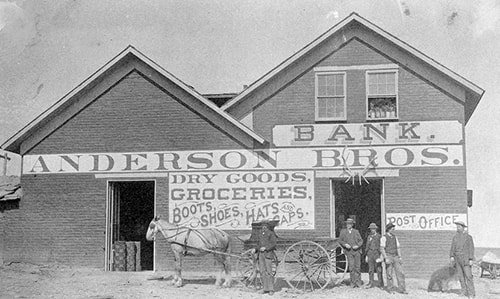

A Post Office, Bank, and General Store (Tap to read)

In the 1860s it wasn’t wise to carry around a lot of money or gold in Idaho Territory. There was always someone ready to relieve you of it and, perhaps, your life if you hesitated to turn over your wealth.

Travelers between Corrine or Kelton, Utah, and Virginia City, Montana began asking the proprietors at the Anderson Brothers store at Taylor Bridge to hold their money for them, keeping it safe until they would return. Taylor Bridge was a toll bridge at what was first called Taylor Bridge, then Eagle Rock as it became a town, and Idaho Falls when it became a city. The Anderson Brothers store was one of the first to serve travelers going back and forth between the Montana mines and Utah supply points.

As the only spot for hundreds of square miles that had even a hint of security, Anderson Brothers began keeping goods and wealth as a favor to miners, often with no receipt except a handshake. The miners would drop back by in person when they were ready to claim their possessions, or they’d send a note by mail to the Anderson Brothers store requesting they send it on to another destination.

The Anderson Brothers began to worry about having money and gold sitting around on shelves beneath the counter, so they ordered a safe. That safe, and its continued use inspired them to open Anderson Brothers Bank.

The store became an unofficial post office the same way it became an unofficial bank, by being a place where people stopped on their way to someplace else.

The post office came about because people would leave letters in a box, hoping someone going more or less in the direction the letter was headed would pick it up and take it a few miles closer. People just pawed through the mail looking for a letter for them, or finding a letter for someone else that they could move on down the road a bit.

If that sounds like a haphazard way to run a post office, it sounded the same way to a postal inspector that happened through on his way to Montana. When he pointed this out to the Anderson Brothers, according to an article in the August 26, 1932 edition of the Post Register, one of them kicked the box of letters out the door and said, “There is your post office. Take it with you, and if you don’t like the way we do things around here we will throw you after the box.”

The inspector had a change of heart and decided they could continue their unauthorized post office, which they did until an official one was established a few years later when the railroad arrived.

Travelers between Corrine or Kelton, Utah, and Virginia City, Montana began asking the proprietors at the Anderson Brothers store at Taylor Bridge to hold their money for them, keeping it safe until they would return. Taylor Bridge was a toll bridge at what was first called Taylor Bridge, then Eagle Rock as it became a town, and Idaho Falls when it became a city. The Anderson Brothers store was one of the first to serve travelers going back and forth between the Montana mines and Utah supply points.

As the only spot for hundreds of square miles that had even a hint of security, Anderson Brothers began keeping goods and wealth as a favor to miners, often with no receipt except a handshake. The miners would drop back by in person when they were ready to claim their possessions, or they’d send a note by mail to the Anderson Brothers store requesting they send it on to another destination.

The Anderson Brothers began to worry about having money and gold sitting around on shelves beneath the counter, so they ordered a safe. That safe, and its continued use inspired them to open Anderson Brothers Bank.

The store became an unofficial post office the same way it became an unofficial bank, by being a place where people stopped on their way to someplace else.

The post office came about because people would leave letters in a box, hoping someone going more or less in the direction the letter was headed would pick it up and take it a few miles closer. People just pawed through the mail looking for a letter for them, or finding a letter for someone else that they could move on down the road a bit.

If that sounds like a haphazard way to run a post office, it sounded the same way to a postal inspector that happened through on his way to Montana. When he pointed this out to the Anderson Brothers, according to an article in the August 26, 1932 edition of the Post Register, one of them kicked the box of letters out the door and said, “There is your post office. Take it with you, and if you don’t like the way we do things around here we will throw you after the box.”

The inspector had a change of heart and decided they could continue their unauthorized post office, which they did until an official one was established a few years later when the railroad arrived.

Published on March 02, 2022 04:00

March 1, 2022

History of Kuna Cave (Tap to read)

It's tempting to write this like a James Michener novel, going back to the beginning of time to give the history of Kuna Cave. You probably don’t have that much coffee, so I'll simply explain how a lava tube is formed.

When lava flows on the earth's surface from an active volcano, the top of the flow begins to cool and solidify as it encounters air. As it hardens, it forms a lava shell. Meanwhile, molten lava flows inside that shell until the eruption stops. Then, like water coming through a hose when you twist the faucet off, the molten lava continues flowing downhill, leaving behind the shell it has formed. Now you have a lava tube.

The Kuna Cave, about six miles southwest of Kuna, is a lava tube. Part of the roof collapsed at some point, leaving a hole in the desert floor into which unsuspecting jackrabbits could plunge. At least a couple of people have also fallen into that hole.

History doesn't record who discovered the cave. The owner of one of those skeletons has my vote. However, we know that Claude W. Gibson and his young friends made one of the earliest explorations of the cave in 1890. The group knew roughly where to look, so their claim isn't one of discovery. They trudged through the desert in a ragged line for about an hour before someone let out a yell.

The group gathered around the yeller and looked down into a three-by-four-foot hole. A shaft of sunlight fell on sand somewhere between 32 and 50 feet below, depending on who was doing the measuring.

Gibson's group came up with one of the better ways to get bodies into the cave. They rolled a wagon to the edge, propped up a wheel, wrapped a rope around the axle, and made it into a windlass. By turning the wheel slowly, they lowered each member of their party down into the cave. The last guy on top was a good rope climber, so he just monkeyed his way down. Sometime later, it occurred to them that someone could come along, steal their wagon, and leave them to ponder the sky through that hole three or four stories above.

They discovered the skeleton of someone who had spent their last days doing just that. Someone decided the man had been an Indian, though they found no artifact to prove that. It looked like he had piled up a tower of rocks trying to get up to that one-way opening.

Around the turn of the century, locals often took carriages to the Kuna cave on a Sunday afternoon for a picnic. Those who dared drop into the hole did so by ropes, a wire ladder, or, eventually, a wooden ladder left in place.

In May 1911, the cave got some extra attention when United States Surveyor General D. A. Utter and a posse of prominent engineers decided to explore the cave. General Utter spent a lot of time in Idaho. He started a vineyard in the King Hill area while still employed as the Surveyor General.

Utter described the cave to the Idaho Statesman: "The most beautiful formation in the cave is an arched hallway, as finely and smoothly constructed as though human hands had been at work there, and which runs forward about 250 feet. It is 20 feet high and about 30 feet wide. The flooring of the archway is covered with a fine coating of sand and is as level as one could wish."

The General got stuck trying to pass through an 18-inch opening and required much pulling and grunting on the part of his fellow explorers to get him out. A skinnier member of the party wormed his way through and crawled about 300 yards before sand blocked his way.

General Utter speculated that the cave ran some six miles, all the way to the Snake River. He thought this because a strong, wet breeze inside the cave kept blowing out candles.

The 1911 party also discovered a skeleton. This one lay on a high ledge as if the person had tried their best to scale the walls of the dome. They decided this skeleton belonged to a white man, again with scant evidence.

Surveyor General Utter, a man who sometimes strayed into hyperbole, called the cave "one of the noted wonders of the country" and thought the government should make it into a resort once improvements were made to the entrance.

That idea died in the cave along with the anonymous men whose skeletons were found there. However, the Bureau of Land Management, which oversees the site today, has plans to put a grating over the entrance and provide a safer ladder into the cave in the near future. They also hope to build a parking lot and reduce the number of roads—six—that lead to the cave, providing a single, improved road.

Back in 1890, one of the first things Gibson's group did was scratch their names on the rock walls. Unfortunately, those wishing for immortality of a sort in recent years have favored spray paint to make their messages, leaving little in the Kuna Cave untarnished.

Three men and three women pose in Kuna Cave in this photo circa 1920. There is already graffiti on the walls, and someone has modified the photo to hide the worst of it. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Three men and three women pose in Kuna Cave in this photo circa 1920. There is already graffiti on the walls, and someone has modified the photo to hide the worst of it. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  The desert grass and shrubs had been trampled down around the mouth of the cave by 1898 when this picture of four unidentified men was taken. It’s easy to see how someone could have stumbled into the hole when the vegetation was intact. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The desert grass and shrubs had been trampled down around the mouth of the cave by 1898 when this picture of four unidentified men was taken. It’s easy to see how someone could have stumbled into the hole when the vegetation was intact. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

When lava flows on the earth's surface from an active volcano, the top of the flow begins to cool and solidify as it encounters air. As it hardens, it forms a lava shell. Meanwhile, molten lava flows inside that shell until the eruption stops. Then, like water coming through a hose when you twist the faucet off, the molten lava continues flowing downhill, leaving behind the shell it has formed. Now you have a lava tube.

The Kuna Cave, about six miles southwest of Kuna, is a lava tube. Part of the roof collapsed at some point, leaving a hole in the desert floor into which unsuspecting jackrabbits could plunge. At least a couple of people have also fallen into that hole.

History doesn't record who discovered the cave. The owner of one of those skeletons has my vote. However, we know that Claude W. Gibson and his young friends made one of the earliest explorations of the cave in 1890. The group knew roughly where to look, so their claim isn't one of discovery. They trudged through the desert in a ragged line for about an hour before someone let out a yell.

The group gathered around the yeller and looked down into a three-by-four-foot hole. A shaft of sunlight fell on sand somewhere between 32 and 50 feet below, depending on who was doing the measuring.

Gibson's group came up with one of the better ways to get bodies into the cave. They rolled a wagon to the edge, propped up a wheel, wrapped a rope around the axle, and made it into a windlass. By turning the wheel slowly, they lowered each member of their party down into the cave. The last guy on top was a good rope climber, so he just monkeyed his way down. Sometime later, it occurred to them that someone could come along, steal their wagon, and leave them to ponder the sky through that hole three or four stories above.

They discovered the skeleton of someone who had spent their last days doing just that. Someone decided the man had been an Indian, though they found no artifact to prove that. It looked like he had piled up a tower of rocks trying to get up to that one-way opening.

Around the turn of the century, locals often took carriages to the Kuna cave on a Sunday afternoon for a picnic. Those who dared drop into the hole did so by ropes, a wire ladder, or, eventually, a wooden ladder left in place.

In May 1911, the cave got some extra attention when United States Surveyor General D. A. Utter and a posse of prominent engineers decided to explore the cave. General Utter spent a lot of time in Idaho. He started a vineyard in the King Hill area while still employed as the Surveyor General.

Utter described the cave to the Idaho Statesman: "The most beautiful formation in the cave is an arched hallway, as finely and smoothly constructed as though human hands had been at work there, and which runs forward about 250 feet. It is 20 feet high and about 30 feet wide. The flooring of the archway is covered with a fine coating of sand and is as level as one could wish."

The General got stuck trying to pass through an 18-inch opening and required much pulling and grunting on the part of his fellow explorers to get him out. A skinnier member of the party wormed his way through and crawled about 300 yards before sand blocked his way.

General Utter speculated that the cave ran some six miles, all the way to the Snake River. He thought this because a strong, wet breeze inside the cave kept blowing out candles.

The 1911 party also discovered a skeleton. This one lay on a high ledge as if the person had tried their best to scale the walls of the dome. They decided this skeleton belonged to a white man, again with scant evidence.

Surveyor General Utter, a man who sometimes strayed into hyperbole, called the cave "one of the noted wonders of the country" and thought the government should make it into a resort once improvements were made to the entrance.

That idea died in the cave along with the anonymous men whose skeletons were found there. However, the Bureau of Land Management, which oversees the site today, has plans to put a grating over the entrance and provide a safer ladder into the cave in the near future. They also hope to build a parking lot and reduce the number of roads—six—that lead to the cave, providing a single, improved road.

Back in 1890, one of the first things Gibson's group did was scratch their names on the rock walls. Unfortunately, those wishing for immortality of a sort in recent years have favored spray paint to make their messages, leaving little in the Kuna Cave untarnished.

Three men and three women pose in Kuna Cave in this photo circa 1920. There is already graffiti on the walls, and someone has modified the photo to hide the worst of it. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Three men and three women pose in Kuna Cave in this photo circa 1920. There is already graffiti on the walls, and someone has modified the photo to hide the worst of it. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  The desert grass and shrubs had been trampled down around the mouth of the cave by 1898 when this picture of four unidentified men was taken. It’s easy to see how someone could have stumbled into the hole when the vegetation was intact. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The desert grass and shrubs had been trampled down around the mouth of the cave by 1898 when this picture of four unidentified men was taken. It’s easy to see how someone could have stumbled into the hole when the vegetation was intact. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on March 01, 2022 04:00