Rick Just's Blog, page 102

February 8, 2022

Betsy With an Extra E (Tap to read)

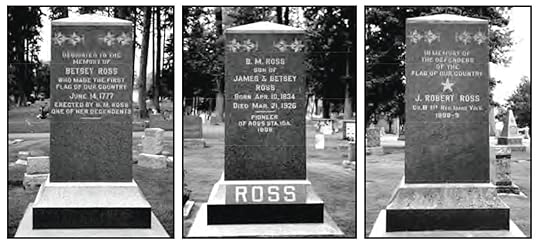

Not all that is written in stone is true. I did a post earlier about a monument memorializing a (probably) nonexistent massacre near Almo. We can trace the roots of that one and get at least an inkling of why the memorial exists. Not so with the memorial to Betsey Ross in the Forest Memorial Cemetery in Coeur d’Alene.

Yes, it is apparently supposed to honor the woman of flag-making legend, although her name did not have that extra E. She died in Philadelphia in 1836. This memorial doesn’t say she’s buried in Coeur d’Alene, just that she is being honored by one of her descendants, B.M. Ross. On one side of the monument B.M. Ross is listed as the son of James and Betsey Ross, born in 1834. Interesting, in that Betsy Ross would have been 82 in 1834, two years before she died. Also, she had seven daughters and no sons.

The Coeur d’Alene Parks Department, which manages the cemeteries in the city, has done an excellent walking tour brochure about the history buried (sorry) in the cemetery. That’s where I found most of the information for this post. If you know anything about Betsey Ross or B.M. Ross, they’d love to hear about it. Clearly someone spent quite a bit of money to put up the monument. The question is, why?

Yes, it is apparently supposed to honor the woman of flag-making legend, although her name did not have that extra E. She died in Philadelphia in 1836. This memorial doesn’t say she’s buried in Coeur d’Alene, just that she is being honored by one of her descendants, B.M. Ross. On one side of the monument B.M. Ross is listed as the son of James and Betsey Ross, born in 1834. Interesting, in that Betsy Ross would have been 82 in 1834, two years before she died. Also, she had seven daughters and no sons.

The Coeur d’Alene Parks Department, which manages the cemeteries in the city, has done an excellent walking tour brochure about the history buried (sorry) in the cemetery. That’s where I found most of the information for this post. If you know anything about Betsey Ross or B.M. Ross, they’d love to hear about it. Clearly someone spent quite a bit of money to put up the monument. The question is, why?

Published on February 08, 2022 04:00

February 7, 2022

A Cougar Tale (Tap to read)

In 1943, Seaman Second Class A.P. McKinley and Specialist First Class John D. Lyons wrote to the Idaho Department of Fish and Game to settle a bet. Both sailors were stationed somewhere in the South Pacific. Lyons, who was from Idaho had bet McKinley, who was from California, that Idaho cougars could grow to 16 feet in length.

Why Governor C.F. Bottolfsen decided to jump into the argument is lost to history. He had been a newspaperman before becoming governor, so he probably relished the idea of exercising his word skills, thus:

“When you claim that only 16-foot cougars are found in Idaho you may be referring to the kittens which frolic in their dens until they attain 17 or 18 feet. I have heard of cougars that measured 20 feet from tip-of-the-nose to tip-of-the-tail, and that’s no tall tale, either.”

Uh, yeah, it was. The governor went on.

“Any smaller cougars would have a hard time for survival in our forests. A nine-foot cougar would have only an outside fighting chance against a couple of our giant jackrabbits. Mr. McKinley would not be safe if he went out with anything short of a buffalo gun, because anti-tank gun tests have shown the hide of these sturdy beasts to be as tough as an eight-inch plank.”

Not one to let a good joke lie, C.J. Westcott, president of the Idaho Wildlife Federation, also wrote to Lyons, adding, “It is evident from Mr. McKinley’s letter that he is from California, where the wildlife outside of Hollywood is not much to brag about. George Metz, who lives up Burgdorf way, shot a male cougar which measured 19 feet with its tail curled up.”

Dick d’Easum, who as a Statesman columnist had written plenty of whoppers himself, was at that time working as the Fish and Game information director. He wrote to the sailors to clear up any confusion—he was representing Fish and Game after all—telling them the biggest specimen known to have been killed in Idaho measured “about 10 feet.” And thus ended the tall… tail.

Why Governor C.F. Bottolfsen decided to jump into the argument is lost to history. He had been a newspaperman before becoming governor, so he probably relished the idea of exercising his word skills, thus:

“When you claim that only 16-foot cougars are found in Idaho you may be referring to the kittens which frolic in their dens until they attain 17 or 18 feet. I have heard of cougars that measured 20 feet from tip-of-the-nose to tip-of-the-tail, and that’s no tall tale, either.”

Uh, yeah, it was. The governor went on.

“Any smaller cougars would have a hard time for survival in our forests. A nine-foot cougar would have only an outside fighting chance against a couple of our giant jackrabbits. Mr. McKinley would not be safe if he went out with anything short of a buffalo gun, because anti-tank gun tests have shown the hide of these sturdy beasts to be as tough as an eight-inch plank.”

Not one to let a good joke lie, C.J. Westcott, president of the Idaho Wildlife Federation, also wrote to Lyons, adding, “It is evident from Mr. McKinley’s letter that he is from California, where the wildlife outside of Hollywood is not much to brag about. George Metz, who lives up Burgdorf way, shot a male cougar which measured 19 feet with its tail curled up.”

Dick d’Easum, who as a Statesman columnist had written plenty of whoppers himself, was at that time working as the Fish and Game information director. He wrote to the sailors to clear up any confusion—he was representing Fish and Game after all—telling them the biggest specimen known to have been killed in Idaho measured “about 10 feet.” And thus ended the tall… tail.

Published on February 07, 2022 04:00

February 6, 2022

The Tragedy of Gobo Fango (Tap to read)

Gobo Fango is not a name you often encounter in Idaho history, memorable as it is. Fango was born in Eastern Cape Colony of what is now South Africa in about 1855. He was a member of the Gcaleka tribe. He was saved from a bloody war with the British that would kill 100,000 of his people, only to end up the victim of a range war some 27 years later in Idaho Territory.

Fango’s desperate, starving mother left him in the crook of a tree when he was three when she could no longer carry him. The sons of Henry and Ruth Talbot, English-speaking settlers, found him. The family adopted Gobo Fango. Or maybe they simply claimed him as property. In either case, they probably saved his life.

The Talbots became converts to the LDS religion. Records of their baptisms exist, though none such for Fango. They smuggled Fango out of the country and into the United States where they found their way to Utah in 1861.

Gobo Fango worked for the Talbots as an indentured servant, by some accounts, as a slave by others. He lived in a shed near their home. When a teenager he was sold, or given to another Mormon family.

Eventually Fango was on his own and working for a sheep operation near Oakley, in Idaho Territory. He was even able to acquire a herd of his own.

Cattlemen viewed sheep as a scourge that was destroying the range. Range wars broke out all over the West between sheep men and cattlemen.

It was one of those conflicts that brought an end to Gobo Fango.

The Idaho Territorial Legislature had passed a law known as the Two-Mile Limit intended to keep sheep grazers at least two miles away from a cattleman’s grazing claim. Early one day cattleman Frank Bedke and a companion rode into Fango’s camp to tell him he and his sheep were too close to Bedke’s claim and that he should leave. Fango resisted. Exactly what happened will never be known, but the black man ended up with a bullet passing through the back of his head and another tearing through his abdomen.

The cattlemen rode away. Gobo Fango, who, incredibly, was still alive, began crawling toward his employer’s home, holding his intestines in his hand as he dragged himself four and half miles.

Gobo Fango lived four or five days before succumbing to his wounds. He made out a will leaving his money and property to friends. Frank Bedke would be tried twice for his murder, with the first trial ending with a hung jury. The second time he was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

The headstone of Gobo Fango can be seen today in the Oakley Cemetery.

Fango’s desperate, starving mother left him in the crook of a tree when he was three when she could no longer carry him. The sons of Henry and Ruth Talbot, English-speaking settlers, found him. The family adopted Gobo Fango. Or maybe they simply claimed him as property. In either case, they probably saved his life.

The Talbots became converts to the LDS religion. Records of their baptisms exist, though none such for Fango. They smuggled Fango out of the country and into the United States where they found their way to Utah in 1861.

Gobo Fango worked for the Talbots as an indentured servant, by some accounts, as a slave by others. He lived in a shed near their home. When a teenager he was sold, or given to another Mormon family.

Eventually Fango was on his own and working for a sheep operation near Oakley, in Idaho Territory. He was even able to acquire a herd of his own.

Cattlemen viewed sheep as a scourge that was destroying the range. Range wars broke out all over the West between sheep men and cattlemen.

It was one of those conflicts that brought an end to Gobo Fango.

The Idaho Territorial Legislature had passed a law known as the Two-Mile Limit intended to keep sheep grazers at least two miles away from a cattleman’s grazing claim. Early one day cattleman Frank Bedke and a companion rode into Fango’s camp to tell him he and his sheep were too close to Bedke’s claim and that he should leave. Fango resisted. Exactly what happened will never be known, but the black man ended up with a bullet passing through the back of his head and another tearing through his abdomen.

The cattlemen rode away. Gobo Fango, who, incredibly, was still alive, began crawling toward his employer’s home, holding his intestines in his hand as he dragged himself four and half miles.

Gobo Fango lived four or five days before succumbing to his wounds. He made out a will leaving his money and property to friends. Frank Bedke would be tried twice for his murder, with the first trial ending with a hung jury. The second time he was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

The headstone of Gobo Fango can be seen today in the Oakley Cemetery.

Published on February 06, 2022 04:00

February 5, 2022

Political Pioneers (Tap to read)

In 1896, Idaho became the fourth state in the nation—preceded by Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah—to give women the right to vote. If you want to get technical, Idaho was actually the second state to do so, since Wyoming and Utah were both territories at the time. This was 23 years ahead of the 19th Amendment which gave that right to all women in the United States.

It wasn’t just voting that interested women. They wanted to be a part of the political process at every level. In 1898 voters elected three women to the Idaho Legislature, Mrs. Mary Wright from Kootenai County (left in the photo), Mrs. Hattie Noble from Boise County, and Mrs. Clara Pamelia Campbell from Ada County. It was the fifth Idaho Legislature.

On February 8, 1899, the Idaho Daily Statesman noted that Mrs. Wright had become the first woman to preside over the Idaho Legislature, and perhaps the first to preside over any legislature in the nation. She was chairman of the committee of the whole during the preceding afternoon and “ruled with a firm but impartial hand.”

Mary Wright was elected Chief Clerk of the House of Representatives, and went on to take a job as the private secretary of Congressman Thomas Glenn.

All of this seemed not to sit well with her husband, who “filed a red hot divorce bill” according the Idaho Statesman, reporting on the proceedings in a Sandpoint court in the April 26, 1904 edition. Mr. Wright claimed that while in the legislature in Boise she “mingled with diverse men, at improper hours and times, making appointments with strange men at committee rooms and hotels.” He also claimed she lost $2,000 on the board of trade, and “used improper language before their son, a lad of 16.”

Mrs Wright shot back with a suit of her own claiming her husband had slandered her. The paper reported that “She produced two witnesses in court and showed that Wright had done little toward her support in years.” The divorce was granted… In favor of Mrs. Wright.

The first women to serve in the Idaho Legislature (back) Mrs. Mary Wright, Kootenai County; (left) Mrs. Hattie Noble, Boise County; (right) Mrs. Clara Pamela Campbell, Ada County. They served during the fifth session of the Legislature, 1898-99. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Archives, a division of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The first women to serve in the Idaho Legislature (back) Mrs. Mary Wright, Kootenai County; (left) Mrs. Hattie Noble, Boise County; (right) Mrs. Clara Pamela Campbell, Ada County. They served during the fifth session of the Legislature, 1898-99. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Archives, a division of the Idaho State Historical Society.

It wasn’t just voting that interested women. They wanted to be a part of the political process at every level. In 1898 voters elected three women to the Idaho Legislature, Mrs. Mary Wright from Kootenai County (left in the photo), Mrs. Hattie Noble from Boise County, and Mrs. Clara Pamelia Campbell from Ada County. It was the fifth Idaho Legislature.

On February 8, 1899, the Idaho Daily Statesman noted that Mrs. Wright had become the first woman to preside over the Idaho Legislature, and perhaps the first to preside over any legislature in the nation. She was chairman of the committee of the whole during the preceding afternoon and “ruled with a firm but impartial hand.”

Mary Wright was elected Chief Clerk of the House of Representatives, and went on to take a job as the private secretary of Congressman Thomas Glenn.

All of this seemed not to sit well with her husband, who “filed a red hot divorce bill” according the Idaho Statesman, reporting on the proceedings in a Sandpoint court in the April 26, 1904 edition. Mr. Wright claimed that while in the legislature in Boise she “mingled with diverse men, at improper hours and times, making appointments with strange men at committee rooms and hotels.” He also claimed she lost $2,000 on the board of trade, and “used improper language before their son, a lad of 16.”

Mrs Wright shot back with a suit of her own claiming her husband had slandered her. The paper reported that “She produced two witnesses in court and showed that Wright had done little toward her support in years.” The divorce was granted… In favor of Mrs. Wright.

The first women to serve in the Idaho Legislature (back) Mrs. Mary Wright, Kootenai County; (left) Mrs. Hattie Noble, Boise County; (right) Mrs. Clara Pamela Campbell, Ada County. They served during the fifth session of the Legislature, 1898-99. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Archives, a division of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The first women to serve in the Idaho Legislature (back) Mrs. Mary Wright, Kootenai County; (left) Mrs. Hattie Noble, Boise County; (right) Mrs. Clara Pamela Campbell, Ada County. They served during the fifth session of the Legislature, 1898-99. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Archives, a division of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on February 05, 2022 04:00

February 4, 2022

Blame Shakespeare (Tap to read)

Blame Shakespeare. More accurately, you should blame Shakespeare enthusiasts, particularly one Eugene Schieffelin.

Starlings. You should blame him for starlings. Folklore has it that Schieffelin introduced the birds, along with dozens of other non-native species, to bring to the United States all the birds mentioned in Shakespeare plays. The motivation may be apocryphal, but Schieffelin and others did import about a hundred pare in 1890 and 1891 to New York City’s Central Park.

It wasn’t uncommon at that time for well-meaning ornithologists to release birds they enjoyed into this new land. They had no concept of invasive species.

The first mention of starlings in the Idaho Statesman was on August 2, 1893: “Many persons have wondered why the starling got its name, which comes from an old word, meaning to look fixedly or to stare, and certainly its eyes are sharp and quick to see danger, so that it is not easily shot in the fields.”

This was clearly written during a tragic shortage of periods at the typesetting table.

The next mention of the bird in the Statesman was in 1909. The story, headlined An Unwelcome Guest, reported that “Uncle Sam” had imported a few pair of starlings to Central Park to keep insects away from fruit crops. Ironically, starlings liked the fruit as well as the insects did. The birds were becoming more common in the East than native birds. The story included another stab at the etymology of the name, attributing it to the starlike yellow spots on the bird’s dark plumage.

Beginning in 1911, the word starling in the Statesman referred most often to the Starling Hotel at 716 ½ Main Street in Boise. It was a magnet for police calls.

In 1947, the Statesman reported on the starling problem in Washington, DC. “… any pedestrian who happens to stroll beneath these trees emerges as spotted as a leopard.” Citizens debated the best way to take care of the birds. One suggested bringing in owls to eat or scare the starlings. “But what if the owl becomes an equally big menace?” the reporter asked. All right, replied the citizen. Bring in eagles to eat the owls. The article ended with the line, “Nobody has figured out yet what to do about the eagles.”

Then, in 1948, the inevitable happened. The Statesman headline read, Caldwell Reports English Starling Moving on Idaho. “Dal Whiffin of Caldwell reported Wednesday he observed a flock of English Starlings in Caldwell. This is believed to be the first report of the birds in Idaho.

“Prof. Harold Tucker of the College of Idaho confirmed Whiffin’s identification of the birds.

“Ornithologists report the starling is anti-social towards other birds and drives them from their nesting areas. The starlings particularly like to drive bluebirds away. The bluebird is the Idaho state bird.”

This propensity of starlings is one of the reasons Al Larson started the bluebird box program in Idaho.

Starlings are one of the most successful birds on the planet. They compete with native birds for nest sites and food. Their murmuration, while beautiful, confuses predators that might otherwise keep their numbers in control. That same murmuration can be a hazard to airplanes.

One other issue with this invasive species is their penchant for spreading weed seeds, particularly those of another invasive species, the Russian Olive.

Agriculturalists hate them. Studies have shown the birds can eat up to 630 pounds of cattle feed every hour.

Starlings are one of only four birds in Idaho that are not protected. The other three are English sparrows, Eurasian-collared doves, and feral pigeons.

We would have all been better off if those 19th century ornithologists had spent their time in Central Park reading sonnets.

Common starling. Wikipedia Commons photo by PierreSelim.

Common starling. Wikipedia Commons photo by PierreSelim.

Starlings. You should blame him for starlings. Folklore has it that Schieffelin introduced the birds, along with dozens of other non-native species, to bring to the United States all the birds mentioned in Shakespeare plays. The motivation may be apocryphal, but Schieffelin and others did import about a hundred pare in 1890 and 1891 to New York City’s Central Park.

It wasn’t uncommon at that time for well-meaning ornithologists to release birds they enjoyed into this new land. They had no concept of invasive species.

The first mention of starlings in the Idaho Statesman was on August 2, 1893: “Many persons have wondered why the starling got its name, which comes from an old word, meaning to look fixedly or to stare, and certainly its eyes are sharp and quick to see danger, so that it is not easily shot in the fields.”

This was clearly written during a tragic shortage of periods at the typesetting table.

The next mention of the bird in the Statesman was in 1909. The story, headlined An Unwelcome Guest, reported that “Uncle Sam” had imported a few pair of starlings to Central Park to keep insects away from fruit crops. Ironically, starlings liked the fruit as well as the insects did. The birds were becoming more common in the East than native birds. The story included another stab at the etymology of the name, attributing it to the starlike yellow spots on the bird’s dark plumage.

Beginning in 1911, the word starling in the Statesman referred most often to the Starling Hotel at 716 ½ Main Street in Boise. It was a magnet for police calls.

In 1947, the Statesman reported on the starling problem in Washington, DC. “… any pedestrian who happens to stroll beneath these trees emerges as spotted as a leopard.” Citizens debated the best way to take care of the birds. One suggested bringing in owls to eat or scare the starlings. “But what if the owl becomes an equally big menace?” the reporter asked. All right, replied the citizen. Bring in eagles to eat the owls. The article ended with the line, “Nobody has figured out yet what to do about the eagles.”

Then, in 1948, the inevitable happened. The Statesman headline read, Caldwell Reports English Starling Moving on Idaho. “Dal Whiffin of Caldwell reported Wednesday he observed a flock of English Starlings in Caldwell. This is believed to be the first report of the birds in Idaho.

“Prof. Harold Tucker of the College of Idaho confirmed Whiffin’s identification of the birds.

“Ornithologists report the starling is anti-social towards other birds and drives them from their nesting areas. The starlings particularly like to drive bluebirds away. The bluebird is the Idaho state bird.”

This propensity of starlings is one of the reasons Al Larson started the bluebird box program in Idaho.

Starlings are one of the most successful birds on the planet. They compete with native birds for nest sites and food. Their murmuration, while beautiful, confuses predators that might otherwise keep their numbers in control. That same murmuration can be a hazard to airplanes.

One other issue with this invasive species is their penchant for spreading weed seeds, particularly those of another invasive species, the Russian Olive.

Agriculturalists hate them. Studies have shown the birds can eat up to 630 pounds of cattle feed every hour.

Starlings are one of only four birds in Idaho that are not protected. The other three are English sparrows, Eurasian-collared doves, and feral pigeons.

We would have all been better off if those 19th century ornithologists had spent their time in Central Park reading sonnets.

Common starling. Wikipedia Commons photo by PierreSelim.

Common starling. Wikipedia Commons photo by PierreSelim.

Published on February 04, 2022 04:00

February 3, 2022

Boise's Columbia Theater (Tap to read)

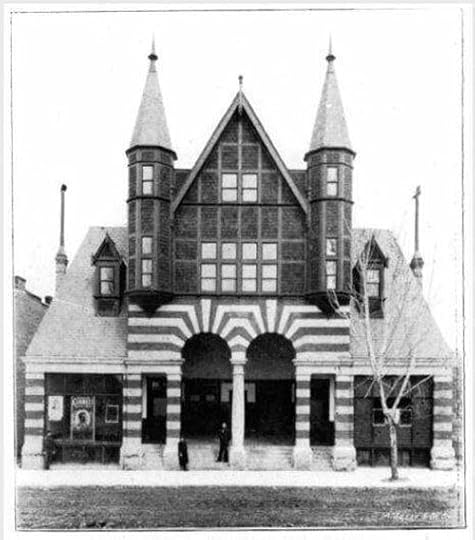

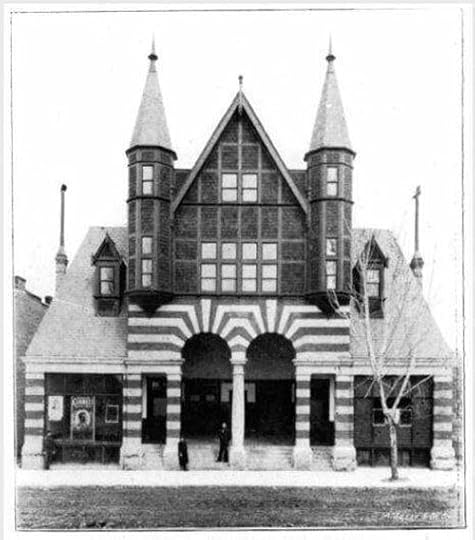

1892 was the 400th anniversary of the “discovery” of America by Columbus. Few were questioning the term “discovery” at that time, though descendants of Vikings and Native Americans likely had their own thoughts on the matter.

There was a groundbreaking that October in Chicago to mark the anniversary. In the whirlwind of construction that followed that ceremonial shoveling, the 1893 Columbian Exposition became a reality.

Everything was Columbian or named after Columbus for months before and after. Boise had (and still has) its Columbian Club, which gathered artifacts for the Idaho exhibit. Less well known was that Boise also had the Columbia Theater. Unlike the Exposition, groundbreaking was in 1892, and the theater’s opening night was in December of the same year.

The mayor of Boise at the time, James Pinney, built the Columbia. Designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, who later served as architects for the Egyptian Theater, the Columbia was striking, though a bit odd looking. Its style was French renaissance.

The Columbia had a pretty good run, lasting 16 years before the former mayor replaced it with the much larger Pinney Theater in 1908. Its run was longer, but the redevelopment wrecking ball took it down in 1969.

Boise's Columbia Theater was a striking design.

Boise's Columbia Theater was a striking design.

There was a groundbreaking that October in Chicago to mark the anniversary. In the whirlwind of construction that followed that ceremonial shoveling, the 1893 Columbian Exposition became a reality.

Everything was Columbian or named after Columbus for months before and after. Boise had (and still has) its Columbian Club, which gathered artifacts for the Idaho exhibit. Less well known was that Boise also had the Columbia Theater. Unlike the Exposition, groundbreaking was in 1892, and the theater’s opening night was in December of the same year.

The mayor of Boise at the time, James Pinney, built the Columbia. Designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, who later served as architects for the Egyptian Theater, the Columbia was striking, though a bit odd looking. Its style was French renaissance.

The Columbia had a pretty good run, lasting 16 years before the former mayor replaced it with the much larger Pinney Theater in 1908. Its run was longer, but the redevelopment wrecking ball took it down in 1969.

Boise's Columbia Theater was a striking design.

Boise's Columbia Theater was a striking design.

Published on February 03, 2022 04:00

February 2, 2022

A Tunnel Beneath Boise! (tap to read)

Burying the story of Chinese tunnels in Boise for a moment, let’s take a look at a tunnel that indisputably exists. It’s the Capitol Mall Tunnel that runs more or less beneath State Street for a couple of blocks near the Idaho statehouse.

Digging the tunnel cost about $280,000 in 1977. It was created to provide underground access to state office buildings for use by state employees and legislators. The tunnel was originally designed to connect the Hall of Mirrors building (formally named the Joe R. Williams Building), the Len B Jordan Office Building, the Capitol Mall parking garage, the Pete T. Cenarrusa Building, and the statehouse. Today it also connects to the Idaho Supreme Court building and lessor known entities such as a credit union, a cafeteria, the state mail offices, and utilities.

The concrete tunnel, about 350 yards at its longest stretch, will not likely become a tourist attraction anytime soon. Although the smooth floor would thrill skateboarders, it isn’t open to the public. Access is available only to those who have key cards. Even so, there was an effort to cheer up the dreary gray walls in the 1980s. High school students were allowed to paint murals on the concrete walls. They are mildly interesting, but those walking through the tunnel might well wish for a midnight assault by spray paint from Banksy.

A mural of the word Agriculture with each letter filled with individual ag paintings was completed in February 2020 by Parma High School art teacher Linda McMillin. Unlike most of the earlier murals this one has a very professional look to it. That’s not a dig at the high school art student murals. They have a simple charm that captures a moment in time for the students who painted them.

Here are a few samples of the paintings in the tunnel.

Digging the tunnel cost about $280,000 in 1977. It was created to provide underground access to state office buildings for use by state employees and legislators. The tunnel was originally designed to connect the Hall of Mirrors building (formally named the Joe R. Williams Building), the Len B Jordan Office Building, the Capitol Mall parking garage, the Pete T. Cenarrusa Building, and the statehouse. Today it also connects to the Idaho Supreme Court building and lessor known entities such as a credit union, a cafeteria, the state mail offices, and utilities.

The concrete tunnel, about 350 yards at its longest stretch, will not likely become a tourist attraction anytime soon. Although the smooth floor would thrill skateboarders, it isn’t open to the public. Access is available only to those who have key cards. Even so, there was an effort to cheer up the dreary gray walls in the 1980s. High school students were allowed to paint murals on the concrete walls. They are mildly interesting, but those walking through the tunnel might well wish for a midnight assault by spray paint from Banksy.

A mural of the word Agriculture with each letter filled with individual ag paintings was completed in February 2020 by Parma High School art teacher Linda McMillin. Unlike most of the earlier murals this one has a very professional look to it. That’s not a dig at the high school art student murals. They have a simple charm that captures a moment in time for the students who painted them.

Here are a few samples of the paintings in the tunnel.

Published on February 02, 2022 04:00

February 1, 2022

Bear Track Williams (Tap to Read)

Not all property owned by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (IDPR) is a state park. One little-known site is called “Bear Track” Williams Recreation Area. Though owned by IDPR, it is managed by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. That’s because the site is primarily for fishing access.

Two parcels, totaling 480 acres, are along Hwy 93 between Carey and Richfield, near Craters of the Moon National Monument.

Ernest Hemingway’s son, Jack, donated the property to the Idaho Foundation for Parks and Lands in 1973, with the intent that they would turn it over to the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation when the donation could be used as a match for acquisition or development of state park property.

IDPR took over ownership of two parcels in 1974 and 1975.

Jack Hemingway purchased the property with the intention of making the donation and specifying that it be named for Taylor “Bear Tracks” Williams.

So, who was “Bear Tracks” Williams? He was one of several hunting and fishing guides who began working in the Wood River Valley when Averell Harriman built his famous Sun Valley Resort. The guides often found themselves rubbing shoulders with the wealthy and famous. Williams guided for Ernest Hemingway, and they became good friends. He often accompanied Hemingway to Cuba. They spent many hours together along Silver Creek and the Little Wood River.

One would assume this outdoor guide got his nickname because of his proficiency in tracking or because of some harrowing tale. Nope. He got the nickname because he walked with his toes pointed out.

“Bear Tracks” Williams Recreation Area is prized for its angling opportunities in the sagebrush desert. Fly fishing there is catch and release. There has been virtually no development on the site since Jack Hemingway donated it more than 40 years ago, which is probably just the way he would have wanted it.

Two parcels, totaling 480 acres, are along Hwy 93 between Carey and Richfield, near Craters of the Moon National Monument.

Ernest Hemingway’s son, Jack, donated the property to the Idaho Foundation for Parks and Lands in 1973, with the intent that they would turn it over to the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation when the donation could be used as a match for acquisition or development of state park property.

IDPR took over ownership of two parcels in 1974 and 1975.

Jack Hemingway purchased the property with the intention of making the donation and specifying that it be named for Taylor “Bear Tracks” Williams.

So, who was “Bear Tracks” Williams? He was one of several hunting and fishing guides who began working in the Wood River Valley when Averell Harriman built his famous Sun Valley Resort. The guides often found themselves rubbing shoulders with the wealthy and famous. Williams guided for Ernest Hemingway, and they became good friends. He often accompanied Hemingway to Cuba. They spent many hours together along Silver Creek and the Little Wood River.

One would assume this outdoor guide got his nickname because of his proficiency in tracking or because of some harrowing tale. Nope. He got the nickname because he walked with his toes pointed out.

“Bear Tracks” Williams Recreation Area is prized for its angling opportunities in the sagebrush desert. Fly fishing there is catch and release. There has been virtually no development on the site since Jack Hemingway donated it more than 40 years ago, which is probably just the way he would have wanted it.

Published on February 01, 2022 04:00

January 31, 2022

Pop Quiz (tap to read)

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture. If you missed that story, click the letter for a link.

1). Nampa’s Drake Drug fire in 1937 was caused by what?

A. A tipped over candle

B. Fireworks

C. A faulty hair dryer

D. An electrical short

E. A gas explosion

2). Which of the following forms of transportation has not been used by Union Pacific?

A. Trains

B. Buses

C. Steamboats

D. Trucks

E. Rickshaw

3). What did the ghost flutist of Sun Valley turn out to be?

A. A CD track on repeat

B. A ghost

C. A middle school student practicing in the woods

D. Wind blowing melodically through a pipe

E. Someone playing a prank

4). For whom was the Pronunciation Guide for the State of Idaho published?

A. Radio and television broadcasters

B. Fourth grade students

C. Customers opening a new checking account

D. People moving to the state from California

E. Newspaper reporters

5) Why was 39 degrees below zero the temperature most often recorded during the Big Shiver of 1888?

A. Mercury thermometers break at that temperature

B. Coincidence

C. Alcohol-based thermometers hadn’t been invented yet

D. Mercury freezes at that temperature

E. Mercury-based thermometers hadn’t been invented yet Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

1, B

2, E (kick yourself if you missed this one)

3, D

4, A

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). Nampa’s Drake Drug fire in 1937 was caused by what?

A. A tipped over candle

B. Fireworks

C. A faulty hair dryer

D. An electrical short

E. A gas explosion

2). Which of the following forms of transportation has not been used by Union Pacific?

A. Trains

B. Buses

C. Steamboats

D. Trucks

E. Rickshaw

3). What did the ghost flutist of Sun Valley turn out to be?

A. A CD track on repeat

B. A ghost

C. A middle school student practicing in the woods

D. Wind blowing melodically through a pipe

E. Someone playing a prank

4). For whom was the Pronunciation Guide for the State of Idaho published?

A. Radio and television broadcasters

B. Fourth grade students

C. Customers opening a new checking account

D. People moving to the state from California

E. Newspaper reporters

5) Why was 39 degrees below zero the temperature most often recorded during the Big Shiver of 1888?

A. Mercury thermometers break at that temperature

B. Coincidence

C. Alcohol-based thermometers hadn’t been invented yet

D. Mercury freezes at that temperature

E. Mercury-based thermometers hadn’t been invented yet

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)1, B

2, E (kick yourself if you missed this one)

3, D

4, A

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on January 31, 2022 04:00

January 30, 2022

The Twin Falls Subway (tap to read)

The canals built by the Twin Falls Land and Water Company brought water to the Magic Valley, making it one of Idaho’s most productive agricultural areas. Bringing water to the desert made it bloom. But after a few years of planting crops, farmers learned something completely unexpected. They had too much water.

Milner Dam, built in 1905, feeds many miles of canals with Snake River water. The loess and alluvium of the desert provide the soil for the crops, but it’s a thin deposit blown in eons ago. Thirty or forty feet below the surface lies lava rock, a solid barrier to water drainage.

In the 1920s, farmers sometimes found themselves standing hip-deep in mud because their irrigation water had nowhere to go. So, in addition to the miles of canals on the surface, the Twin Falls Land and Water Company determined that they needed a drainage system to take the agricultural runoff back to the Snake River.

Beginning in 1926, tunnel crews dug, blasted, and drilled what would become a tunnel system nearly 22 miles in length. Some 350 men dug the tunnels between 1926 and 1951. Some 20 died in the effort, mostly when explosives detonated prematurely.

The tunnels average about six feet high and four feet wide. Water about 18 inches deep flows along the floor. It gets there from hundreds of holes drilled in the top of the tunnels to allow the saturated soil above to drain.

One can only imagine how many teenagers and older people who should have known better explored those tunnels over the years. Today, most of the entrances are sealed. Those that remain are kept a secret and for good reason. As one gets further back into the system, breathable air decreases, creating a hazard to anyone who enters.

Milner Dam under construction.

Milner Dam under construction.

Milner Dam, built in 1905, feeds many miles of canals with Snake River water. The loess and alluvium of the desert provide the soil for the crops, but it’s a thin deposit blown in eons ago. Thirty or forty feet below the surface lies lava rock, a solid barrier to water drainage.

In the 1920s, farmers sometimes found themselves standing hip-deep in mud because their irrigation water had nowhere to go. So, in addition to the miles of canals on the surface, the Twin Falls Land and Water Company determined that they needed a drainage system to take the agricultural runoff back to the Snake River.

Beginning in 1926, tunnel crews dug, blasted, and drilled what would become a tunnel system nearly 22 miles in length. Some 350 men dug the tunnels between 1926 and 1951. Some 20 died in the effort, mostly when explosives detonated prematurely.

The tunnels average about six feet high and four feet wide. Water about 18 inches deep flows along the floor. It gets there from hundreds of holes drilled in the top of the tunnels to allow the saturated soil above to drain.

One can only imagine how many teenagers and older people who should have known better explored those tunnels over the years. Today, most of the entrances are sealed. Those that remain are kept a secret and for good reason. As one gets further back into the system, breathable air decreases, creating a hazard to anyone who enters.

Milner Dam under construction.

Milner Dam under construction.

Published on January 30, 2022 04:00