Rick Just's Blog, page 106

December 30, 2021

The Galloping Goose and the Dinkey (Tap to Read)

It’s not always a train that you might see riding the rails. You’ve probably seen small railroad work cars from time to time on the tracks with four metal wheels. They’re usually a little smaller than a Volkswagen bug. They are commonly called “speeders,” and have become popular in recent years with people who buy them, trick them out, and use them on abandoned railways.

Sometimes you’ll see a specially equipped railroad-operated pickup on the rails, using steel wheels that can be lowered down.

But have you ever seen a bus use the tracks? They were fairly common in the 20s and 30s. They were usually conversions of buses or trucks retrofitted with steel wheels to run a railroad line. They were often called Galloping Gooses. Geese, for the plural? Maybe.

You can view a Galloping Goose in Soda Springs at Corrigan Park in the heart of the city. This particular Goose had a custom wooden body and used a Model T engine. It ran between Soda Springs and the Anaconda Mine. According to Ellen Carney’s book, History of Soda Springs , the Galloping Goose would leave the mine when enough passengers had gathered to make the trip worthwhile. When it rolled in to Soda Springs the driver would ease it on to a turntable. Once parked on the turntable the passengers would get out and push the rig around so it could head back to the mine.

Soda Springs has another piece of railroad history in the same park. It’s called the Dinkey Engine. This miniature engine was also used to run back and forth between the mines. It was apparently out of service and abandoned when the Alexander Reservoir filled in 1924, drowning the Dinkey. During repairs to the reservoir in 1976, residents spotted it and drug it out. Union Pacific helped with the restoration and the city put the Dinkey on display in the park.

Sometimes you’ll see a specially equipped railroad-operated pickup on the rails, using steel wheels that can be lowered down.

But have you ever seen a bus use the tracks? They were fairly common in the 20s and 30s. They were usually conversions of buses or trucks retrofitted with steel wheels to run a railroad line. They were often called Galloping Gooses. Geese, for the plural? Maybe.

You can view a Galloping Goose in Soda Springs at Corrigan Park in the heart of the city. This particular Goose had a custom wooden body and used a Model T engine. It ran between Soda Springs and the Anaconda Mine. According to Ellen Carney’s book, History of Soda Springs , the Galloping Goose would leave the mine when enough passengers had gathered to make the trip worthwhile. When it rolled in to Soda Springs the driver would ease it on to a turntable. Once parked on the turntable the passengers would get out and push the rig around so it could head back to the mine.

Soda Springs has another piece of railroad history in the same park. It’s called the Dinkey Engine. This miniature engine was also used to run back and forth between the mines. It was apparently out of service and abandoned when the Alexander Reservoir filled in 1924, drowning the Dinkey. During repairs to the reservoir in 1976, residents spotted it and drug it out. Union Pacific helped with the restoration and the city put the Dinkey on display in the park.

Published on December 30, 2021 04:00

December 29, 2021

John West's Vote Didn't Count (Tap to Read)

At the risk of causing readers to run away jibbering incoherently, I present for your consideration a story about voting and a contested ballot. This is not a contemporary story and I’m not once going to bring up party affiliation. It is about the difference a single vote can have in an election and how important that vote can be for the candidate and the voter.

The year was 1870. An election took place that June in Boise with a slate of candidates for various offices there for the choosing. The race for Ada County Sheriff turned out to be the one to watch.

L.B. Lindsey and William Bryon were the candidates in the race, and it was a close one. Six of the ballots had some variation of Wm. Bryon's name, but not the exact name. For instance, someone had written Bryon without a first name, three had spelled the name Brion, and three spelled it Bryant. They similar issues with ballots cast for Lindsey, or Linsy, or Lindsley, or Lensy. The election judges all the variations accepted as legal ballots. Upon further examination, judges determined that a handful of people who had cast ballots were not legal voters. Those ballots were thrown out.

It came down to 419 votes for Bryon, and 418 votes for Lindsey. One vote could make the difference between a victory or a tie. There was one ballot submitted by John West that had a special status.

West was a legal voter, and he had spelled the candidate’s name right. So why was his vote originally denied? Because he was, as the papers would say at that time, a colored man. Poll workers initially denied him the vote for that reason, probably because they did not know that the 15th Amendment to the Constitution had been ratified in February of that year. That amendment reads, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The election judges determined that West’s vote was legitimate. He had written in Bryon's name, giving the new sheriff 420 votes.

That could have been the end of the story. Bryon was happy, and West was happy. West’s happiness might have been tempered a bit when Bryon arrested him a few months later on the charge of battery. West had gotten into a fistfight with Frank Slocum. The jury found West guilty. He was fined $30 and court costs, totaling $107.

That could have been the end of the story. West refused to pay the $107 and as a result, ended up in jail. He filed a writ of habeas corpus. In response, Sheriff Bryon offered a certified copy of the judgment in the case. When the Idaho Supreme Court reviewed it, they wrote a lengthy description of the case's circumstances, which local paper printed in full. We don’t have space and readers don’t have the patience to wade through that, so I’ll summarize.

The description of the case provided by the sheriff left out one detail, to wit, he failed to state what crime West was charged with. In its wisdom, the court determined that West could not be held without a stated crime for which he had been convicted. They ordered that he be discharged at once.

West, who was quick to engage in a fight, had a few other minor scrapes with the law over the years. He also got to know well the makers of laws. John West served as the master of the legislative cloakroom for many sessions of the Idaho Legislature, making sure everything was clean and in good order.

When he died at age 80, John West was remembered by the Idaho Statesman as “the dean of colored pioneers in Idaho.” No mention was made of that contested ballot.

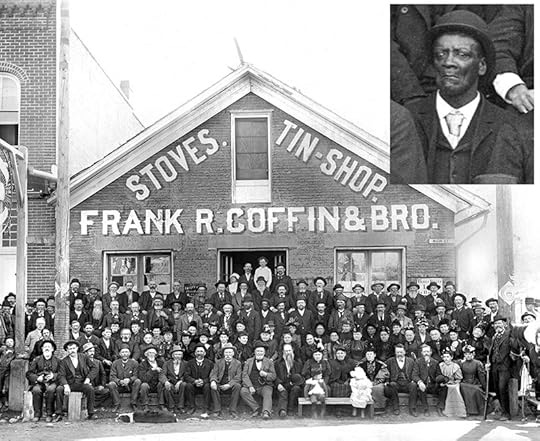

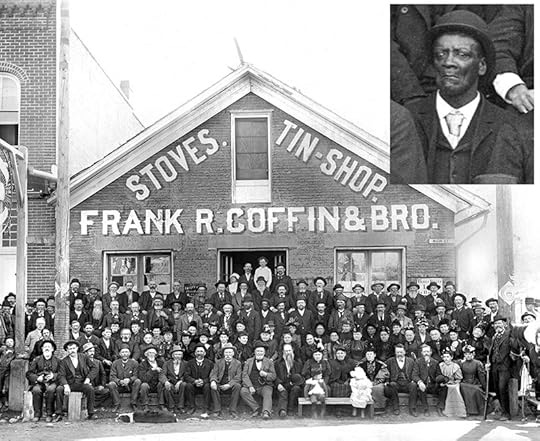

One of the few photos of John West known to exist shows him in the center of a large group of men posing in front of the Frank R. Coffin and Brother establishment in Boise. It was the largest hardware store in Idaho Territory and had locations in Hailey and Bellevue. West is near the center of the picture and shown in the inset. The purpose of the gathering is unknown. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

One of the few photos of John West known to exist shows him in the center of a large group of men posing in front of the Frank R. Coffin and Brother establishment in Boise. It was the largest hardware store in Idaho Territory and had locations in Hailey and Bellevue. West is near the center of the picture and shown in the inset. The purpose of the gathering is unknown. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The year was 1870. An election took place that June in Boise with a slate of candidates for various offices there for the choosing. The race for Ada County Sheriff turned out to be the one to watch.

L.B. Lindsey and William Bryon were the candidates in the race, and it was a close one. Six of the ballots had some variation of Wm. Bryon's name, but not the exact name. For instance, someone had written Bryon without a first name, three had spelled the name Brion, and three spelled it Bryant. They similar issues with ballots cast for Lindsey, or Linsy, or Lindsley, or Lensy. The election judges all the variations accepted as legal ballots. Upon further examination, judges determined that a handful of people who had cast ballots were not legal voters. Those ballots were thrown out.

It came down to 419 votes for Bryon, and 418 votes for Lindsey. One vote could make the difference between a victory or a tie. There was one ballot submitted by John West that had a special status.

West was a legal voter, and he had spelled the candidate’s name right. So why was his vote originally denied? Because he was, as the papers would say at that time, a colored man. Poll workers initially denied him the vote for that reason, probably because they did not know that the 15th Amendment to the Constitution had been ratified in February of that year. That amendment reads, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The election judges determined that West’s vote was legitimate. He had written in Bryon's name, giving the new sheriff 420 votes.

That could have been the end of the story. Bryon was happy, and West was happy. West’s happiness might have been tempered a bit when Bryon arrested him a few months later on the charge of battery. West had gotten into a fistfight with Frank Slocum. The jury found West guilty. He was fined $30 and court costs, totaling $107.

That could have been the end of the story. West refused to pay the $107 and as a result, ended up in jail. He filed a writ of habeas corpus. In response, Sheriff Bryon offered a certified copy of the judgment in the case. When the Idaho Supreme Court reviewed it, they wrote a lengthy description of the case's circumstances, which local paper printed in full. We don’t have space and readers don’t have the patience to wade through that, so I’ll summarize.

The description of the case provided by the sheriff left out one detail, to wit, he failed to state what crime West was charged with. In its wisdom, the court determined that West could not be held without a stated crime for which he had been convicted. They ordered that he be discharged at once.

West, who was quick to engage in a fight, had a few other minor scrapes with the law over the years. He also got to know well the makers of laws. John West served as the master of the legislative cloakroom for many sessions of the Idaho Legislature, making sure everything was clean and in good order.

When he died at age 80, John West was remembered by the Idaho Statesman as “the dean of colored pioneers in Idaho.” No mention was made of that contested ballot.

One of the few photos of John West known to exist shows him in the center of a large group of men posing in front of the Frank R. Coffin and Brother establishment in Boise. It was the largest hardware store in Idaho Territory and had locations in Hailey and Bellevue. West is near the center of the picture and shown in the inset. The purpose of the gathering is unknown. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

One of the few photos of John West known to exist shows him in the center of a large group of men posing in front of the Frank R. Coffin and Brother establishment in Boise. It was the largest hardware store in Idaho Territory and had locations in Hailey and Bellevue. West is near the center of the picture and shown in the inset. The purpose of the gathering is unknown. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on December 29, 2021 04:00

December 28, 2021

Steamboats Collide (Tap to Read)

Monday, July 17, 1905, was a typical summer day on the St. Joe River. Steamboats were traveling up and down the "Shadowy" St. Joe, which locals claimed, incorrectly, to be the world's highest navigable river.

Captain George Reynolds was at the helm of the Boneta on her regular run up the river to St. Maries. He'd navigated those waters many times before and had held a master's license for 25 years. Reynolds was also part-owner of the boat, which had been constructed the summer before at Johnson's boat works in Coeur d'Alene. This was

the Boneta's first run in a few days, having spent some time getting a blown cylinder repaired.

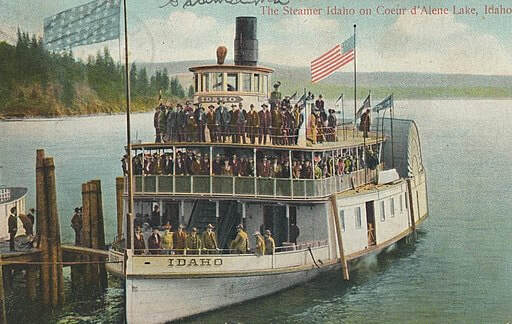

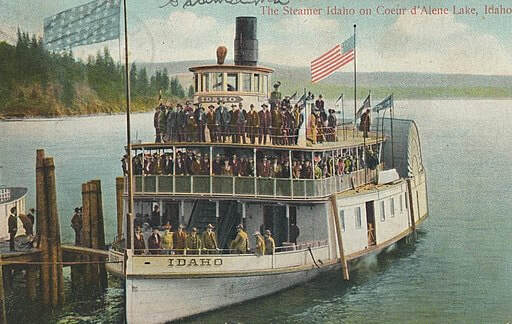

Meanwhile, the fast steamer Idaho was on her regular run downstream on the St. Joe, captained by Jim Spaulding. The Idaho was a sidewheeler built-in 1903.

Reynolds was expecting to encounter the Idaho at any moment, given their common schedules. According to his account, he blew one long blast with his steam whistle to alert any boat that he was approaching a blind bend in the river known as Bend Wah, about three miles above Chatcolet Bridge.

"Just then, the Idaho hove in sight coming around the bend," Reynolds told the Coeur d'Alene Press. 111 then blew two whistles to pass her on my right. She answered the alarm whistle but never answered the passing whistle."

Both captains had different versions of what whistles blew when and what each meant. To say there was some confusion understates it.

Captain Spaulding refused to talk with the press. Red Collar Line management-the company that owned the Idaho-said they "did not care to enter into a newspaper controversy."

Captain Reynolds talked quite a lot, accusing the Idaho's captain of deliberately ramming the Boneta.

"When I saw that she was going to run me down if she kept on that course, I stopped my boat and backed, expecting that she would do the same, but she continued to come full head-on.

"I swung my boat across the river to try to avoid a collision.

The Idaho's pilot then swung the Idaho and followed me, still continuing to work his boat full steam ahead. Then when within 20 feet of me he stopped his engines."

The Idaho rammed into the Boneta, punching a big hole in the side of the boat about one-third of the way back from the bow. Captain Reynolds quickly grounded the Boneta. Still, she partially sank in about 15 feet of water.

Meanwhile, the Idaho paused long enough to be sure no one was injured, then continued on her way downriver, her bow scraped a bit and sporting a broken jackstaff . The five passengers who were on the Boneta were unhurt. A team of horses also rode out the collision with no injury.

The owners later raised the Boneta, and she began operating again on Lake Coeur d'Alene and the St. Joe. Although the arguments about who was to blame went to trial, the court could not determine culpability.

Captain George Reynolds was at the helm of the Boneta on her regular run up the river to St. Maries. He'd navigated those waters many times before and had held a master's license for 25 years. Reynolds was also part-owner of the boat, which had been constructed the summer before at Johnson's boat works in Coeur d'Alene. This was

the Boneta's first run in a few days, having spent some time getting a blown cylinder repaired.

Meanwhile, the fast steamer Idaho was on her regular run downstream on the St. Joe, captained by Jim Spaulding. The Idaho was a sidewheeler built-in 1903.

Reynolds was expecting to encounter the Idaho at any moment, given their common schedules. According to his account, he blew one long blast with his steam whistle to alert any boat that he was approaching a blind bend in the river known as Bend Wah, about three miles above Chatcolet Bridge.

"Just then, the Idaho hove in sight coming around the bend," Reynolds told the Coeur d'Alene Press. 111 then blew two whistles to pass her on my right. She answered the alarm whistle but never answered the passing whistle."

Both captains had different versions of what whistles blew when and what each meant. To say there was some confusion understates it.

Captain Spaulding refused to talk with the press. Red Collar Line management-the company that owned the Idaho-said they "did not care to enter into a newspaper controversy."

Captain Reynolds talked quite a lot, accusing the Idaho's captain of deliberately ramming the Boneta.

"When I saw that she was going to run me down if she kept on that course, I stopped my boat and backed, expecting that she would do the same, but she continued to come full head-on.

"I swung my boat across the river to try to avoid a collision.

The Idaho's pilot then swung the Idaho and followed me, still continuing to work his boat full steam ahead. Then when within 20 feet of me he stopped his engines."

The Idaho rammed into the Boneta, punching a big hole in the side of the boat about one-third of the way back from the bow. Captain Reynolds quickly grounded the Boneta. Still, she partially sank in about 15 feet of water.

Meanwhile, the Idaho paused long enough to be sure no one was injured, then continued on her way downriver, her bow scraped a bit and sporting a broken jackstaff . The five passengers who were on the Boneta were unhurt. A team of horses also rode out the collision with no injury.

The owners later raised the Boneta, and she began operating again on Lake Coeur d'Alene and the St. Joe. Although the arguments about who was to blame went to trial, the court could not determine culpability.

Published on December 28, 2021 04:00

December 27, 2021

Packer John Part Two (Tap to Read)

Continuing the story of Packer John from yesterday’s post.

I’ve known this story for years and had visited Packer John’s Cabin when it was a state park unit several times (it is now managed by Adams County). What I didn’t know was anything about “Packer” John. I assumed he was probably a grizzled old guy who got along better with mules than with people.

John Welch was neither grizzled nor old. He built that cabin in the winter of 1862 when he was 20 years old. It wasn’t in his plans to build a cabin, but the weather caught him on a trip south from Lewiston. He couldn’t make it over the pass into Long Valley with his string. The cabin was to keep he and his crew warm. Welch probably had no idea he was building a convention center.

After serving its role in early Idaho history, the cabin was abandoned. Emma Edwards Green, the artist who created Idaho’s state seal, stopped by the site in 1891 to paint a couple of pictures of the relic. It attracted photographers for a while, then served as an unofficial picnic and camping area. The Idaho Legislature appropriated $500 in 1909 to purchase the cabin and a little land—10 acres—around it. It was memorialized in 1936 with a monument placed along the road by the Daughters of the Idaho Pioneers. It became a state park in 1951 and lost that status in 1982.

But, there I go, writing about the cabin. I wanted to write about young “Packer” John Welch.

Welch ran a store in Leesburg for a while and—not surprisingly—ran a pack string on the trail between Boise and Lewiston. Packing was something he did for just a short time. He was more interested in making money than running mules, so he ended up in Salmon. “Ended up” is about right.

It’s unclear where Welch got $300 worth of gold dust, but he had it in his possession on December 21, 1867. His travelling companion, John S. Ramey had $3200 in cash and $500 worth of gold dust. They were headed from Salmon to Boise on December 15, 1867, each riding a horse and leading a pack animal.

About 25 miles south of Malad Station they were accosted by four highwaymen. Two of the robbers held guns on the pair, while their partners relieved Welch and Ramey of the valuables. It did not sit well with either of the victims, but it was Welch who decided to voice his disgruntlement.

The December 21, 1867 Idaho Statesman described it this way. “Welch complained that ‘this was too bad,’ and remarked that ‘he would meet some of them again, and he would know them, too.’” That’s when one of the guards shot him through the head.

John Ramey, who happened to be the undersheriff in Idaho County, lived to tell about the incident.

So, Packer John Welch would never be a grizzled old packer. He was 25 when he died. His brother, William, retrieved the body and took it back to Clackamas County Oregon for burial.

The monument placed by the Daughters of Idaho Pioneers in 1936 still exists.

The monument placed by the Daughters of Idaho Pioneers in 1936 still exists.

I’ve known this story for years and had visited Packer John’s Cabin when it was a state park unit several times (it is now managed by Adams County). What I didn’t know was anything about “Packer” John. I assumed he was probably a grizzled old guy who got along better with mules than with people.

John Welch was neither grizzled nor old. He built that cabin in the winter of 1862 when he was 20 years old. It wasn’t in his plans to build a cabin, but the weather caught him on a trip south from Lewiston. He couldn’t make it over the pass into Long Valley with his string. The cabin was to keep he and his crew warm. Welch probably had no idea he was building a convention center.

After serving its role in early Idaho history, the cabin was abandoned. Emma Edwards Green, the artist who created Idaho’s state seal, stopped by the site in 1891 to paint a couple of pictures of the relic. It attracted photographers for a while, then served as an unofficial picnic and camping area. The Idaho Legislature appropriated $500 in 1909 to purchase the cabin and a little land—10 acres—around it. It was memorialized in 1936 with a monument placed along the road by the Daughters of the Idaho Pioneers. It became a state park in 1951 and lost that status in 1982.

But, there I go, writing about the cabin. I wanted to write about young “Packer” John Welch.

Welch ran a store in Leesburg for a while and—not surprisingly—ran a pack string on the trail between Boise and Lewiston. Packing was something he did for just a short time. He was more interested in making money than running mules, so he ended up in Salmon. “Ended up” is about right.

It’s unclear where Welch got $300 worth of gold dust, but he had it in his possession on December 21, 1867. His travelling companion, John S. Ramey had $3200 in cash and $500 worth of gold dust. They were headed from Salmon to Boise on December 15, 1867, each riding a horse and leading a pack animal.

About 25 miles south of Malad Station they were accosted by four highwaymen. Two of the robbers held guns on the pair, while their partners relieved Welch and Ramey of the valuables. It did not sit well with either of the victims, but it was Welch who decided to voice his disgruntlement.

The December 21, 1867 Idaho Statesman described it this way. “Welch complained that ‘this was too bad,’ and remarked that ‘he would meet some of them again, and he would know them, too.’” That’s when one of the guards shot him through the head.

John Ramey, who happened to be the undersheriff in Idaho County, lived to tell about the incident.

So, Packer John Welch would never be a grizzled old packer. He was 25 when he died. His brother, William, retrieved the body and took it back to Clackamas County Oregon for burial.

The monument placed by the Daughters of Idaho Pioneers in 1936 still exists.

The monument placed by the Daughters of Idaho Pioneers in 1936 still exists.

Published on December 27, 2021 04:00

December 26, 2021

Packer John Part One (Tap to Read)

If the size of a building were the measure of its fame, Packer John’s Cabin would be at about the bottom of the list in Idaho. At 432 square feet it probably wouldn’t even bring half a million dollars today if it were in Boise’s North End. The 18’ x 24’ cabin was built by John William Welch, Jr. to serve as a storage space and occasional shelter from winter weather. It was located roughly halfway between Lewiston and Boise on Goose Creek near what is now the tiny community of Meadows.

“Halfway” was its reason for fame. The capital of Idaho Territory was, let’s say, transitioning from Lewiston to Boise in 1863. Democrats decided the place was perfect for their first territorial convention because of its location. Before you start guffawing about Democrats needing only a phone booth for their convention, you should know a couple of things. First, there were no phonebooths in 1863 and second, the Republican Party had only lately been invented.

As it turned out, the Democrats got their wires crossed somehow about where they were meeting, so the ended up trekking to Lewiston to have their confab. They did meet at Packer John’s Cabin, though, in 1864. So did some version of the Republicans.

So, a small measure of fame for a small cabin. Tomorrow, we take a look at Packer John, the man who built the cabin.

The Packer John's Cabin replica.

The Packer John's Cabin replica.

“Halfway” was its reason for fame. The capital of Idaho Territory was, let’s say, transitioning from Lewiston to Boise in 1863. Democrats decided the place was perfect for their first territorial convention because of its location. Before you start guffawing about Democrats needing only a phone booth for their convention, you should know a couple of things. First, there were no phonebooths in 1863 and second, the Republican Party had only lately been invented.

As it turned out, the Democrats got their wires crossed somehow about where they were meeting, so the ended up trekking to Lewiston to have their confab. They did meet at Packer John’s Cabin, though, in 1864. So did some version of the Republicans.

So, a small measure of fame for a small cabin. Tomorrow, we take a look at Packer John, the man who built the cabin.

The Packer John's Cabin replica.

The Packer John's Cabin replica.

Published on December 26, 2021 04:00

December 25, 2021

Merry Christmas! (Tap to Read)

I decided to pop in on some Idaho newspapers from the past to see what people were saying about Christmas.

In 1867 the Tremont Restaurant was opening for the first time on Christmas day in Idaho City, offering “the best of everything in the best style.”

In 1882, the Wood River Times noted that “The swift hand of time, in turning over the pages of days and months, has brought us around again to the joyful time of Christmas.”

On December 24, 1886, the Idaho County Free Press in Grangeville noted in a column called Sidewalk Prattle that “The stores look like the holiday season these days,” and that “A cold wave is naturally followed by a matrimonial wave.”

The next year, on December 24, the Idaho News in Blackfoot was wishing “A merry Christmas to all our brethren of the Idaho Press,” and noted that the temperature had hit 21 below on Wednesday.

In 1889, the Caldwell Tribune announced a Grand Masquerade Ball to be held in Emmett. “No disreputable persons admitted. Ball tickets including supper, $2.50; spectators $1.00. A grand time is anticipated and everything possible will be done to guarantee it.”

On December 20, 1890, the Ketchum Keystone reported that “Preparations are being made by Mrs. Dr. Ritchie and others for a Christmas tree. It will be erected in Union Congregational Church and the ladies desire that someone volunteer to procure the tree.”

In 1891, Miss Emma Edwards, who had lately designed the Idaho state seal, was selling Idaho Christmas cards “with a photo of some prominent feature of Boise, half concealed with sprays of natural grasses.” The Idaho Daily Statesman noted that the effect was “very pleasing.”

In the Coeur d’Alene Press in 1893 V.W. Sander & Co., a dry goods store, was wishing a Merry Xmas to all in its ad. They had “Holiday goods, including things useful and ornamental for our little ones.” They hoped that “Santa Claus will come in spite of the hard times and make the little folks happy!”

And a happy Christmas to you.

Some Christmas gift-giving ideas from 100 years ago.

Some Christmas gift-giving ideas from 100 years ago.

In 1867 the Tremont Restaurant was opening for the first time on Christmas day in Idaho City, offering “the best of everything in the best style.”

In 1882, the Wood River Times noted that “The swift hand of time, in turning over the pages of days and months, has brought us around again to the joyful time of Christmas.”

On December 24, 1886, the Idaho County Free Press in Grangeville noted in a column called Sidewalk Prattle that “The stores look like the holiday season these days,” and that “A cold wave is naturally followed by a matrimonial wave.”

The next year, on December 24, the Idaho News in Blackfoot was wishing “A merry Christmas to all our brethren of the Idaho Press,” and noted that the temperature had hit 21 below on Wednesday.

In 1889, the Caldwell Tribune announced a Grand Masquerade Ball to be held in Emmett. “No disreputable persons admitted. Ball tickets including supper, $2.50; spectators $1.00. A grand time is anticipated and everything possible will be done to guarantee it.”

On December 20, 1890, the Ketchum Keystone reported that “Preparations are being made by Mrs. Dr. Ritchie and others for a Christmas tree. It will be erected in Union Congregational Church and the ladies desire that someone volunteer to procure the tree.”

In 1891, Miss Emma Edwards, who had lately designed the Idaho state seal, was selling Idaho Christmas cards “with a photo of some prominent feature of Boise, half concealed with sprays of natural grasses.” The Idaho Daily Statesman noted that the effect was “very pleasing.”

In the Coeur d’Alene Press in 1893 V.W. Sander & Co., a dry goods store, was wishing a Merry Xmas to all in its ad. They had “Holiday goods, including things useful and ornamental for our little ones.” They hoped that “Santa Claus will come in spite of the hard times and make the little folks happy!”

And a happy Christmas to you.

Some Christmas gift-giving ideas from 100 years ago.

Some Christmas gift-giving ideas from 100 years ago.

Published on December 25, 2021 04:00

December 24, 2021

Washing up those Fingers (Tap to Read)

Perhaps you use a finger bowl with every meal at your house. Mine, not so much. I think I could count the times I’ve been given such a choice in restaurant on… a few fingers.

They were quite common into the first part of the Twentieth Century but seem to have fallen out of use during World War I when citizens were encouraged to be conservative in all things.

Finger bowls came out of a Russian tradition of dining, where meals were served one course at a time. Finger bowls often arrived before desert, perhaps on a small plate with a doily beneath the bowl. Diners gave their fingers a little rinse, drying them on a napkin.

Since I rarely give lessons in etiquette, one might wonder why I bring this up at all. Does one wonder? Well, it is because I came across multiple references to J.K. White during research on the Ada County Poor Farm. White was the chief health inspector for the state of Idaho. He was instrumental in shutting the place down because of deplorable conditions. One of those references was an article all about finger bowls, so here we are.

White, during the regular course of his duties inspecting restaurants, discovered a common practice that gave him the willies. That’s a technical term in the inspection business. As White explained in the December 7, 1913 edition of the Idaho Statesman, “As it is now, the bowls are used and then emptied and placed on the sideboard or shelf to be used again.”

Clever readers will have noticed that there was a missing step between a finger bowl’s use and its reuse. Washing.

White put it quite forcefully: “We insist that this is wrong, subjecting the users of these bowls to the danger of contracting contagious diseases. If the bowls were thoroughly cleaned after each using, as the dishes are, no complaint could be made.”

Restaurants and, notably railroad dining cars, took the news in stride and agreed to henceforth give the bowls a thorough cleaning. So, rest assured, the next time you twiddle your fingers in such a bowl it has almost certainly been cleaned since the last finger twiddler used it.

They were quite common into the first part of the Twentieth Century but seem to have fallen out of use during World War I when citizens were encouraged to be conservative in all things.

Finger bowls came out of a Russian tradition of dining, where meals were served one course at a time. Finger bowls often arrived before desert, perhaps on a small plate with a doily beneath the bowl. Diners gave their fingers a little rinse, drying them on a napkin.

Since I rarely give lessons in etiquette, one might wonder why I bring this up at all. Does one wonder? Well, it is because I came across multiple references to J.K. White during research on the Ada County Poor Farm. White was the chief health inspector for the state of Idaho. He was instrumental in shutting the place down because of deplorable conditions. One of those references was an article all about finger bowls, so here we are.

White, during the regular course of his duties inspecting restaurants, discovered a common practice that gave him the willies. That’s a technical term in the inspection business. As White explained in the December 7, 1913 edition of the Idaho Statesman, “As it is now, the bowls are used and then emptied and placed on the sideboard or shelf to be used again.”

Clever readers will have noticed that there was a missing step between a finger bowl’s use and its reuse. Washing.

White put it quite forcefully: “We insist that this is wrong, subjecting the users of these bowls to the danger of contracting contagious diseases. If the bowls were thoroughly cleaned after each using, as the dishes are, no complaint could be made.”

Restaurants and, notably railroad dining cars, took the news in stride and agreed to henceforth give the bowls a thorough cleaning. So, rest assured, the next time you twiddle your fingers in such a bowl it has almost certainly been cleaned since the last finger twiddler used it.

Published on December 24, 2021 04:00

December 23, 2021

The Ada County Poor Farm (Tap to Read)

The Collister Neighborhood in Boise is full of mature trees and lovely homes today. From 1883 to 1916 it was the site of Ada County’s Poor Farm, located about where Cynthia Mann Elementary is today. The first doctor who contracted his services with the Poor Farm was Dr. George Collister. He practiced medicine in Boise for more than 50 years and owned a large orchard about six miles from downtown Boise. The area surrounding his orchard took on his name, as did the neighborhood and the street.

The Ada County Poor Farm was started with the best of intentions. The January 26, 1883 edition of the Idaho Statesman opined that “Some provision must be made for the care of the poor. Our present county hospital system is for the care of the indigent sick, idiotic and insane. The poor, or that class which may be in destitute circumstances, is not included in the hospital contract.”

The county purchased the property for the Poor Farm from John Hailey, owner of the Pioneer Stage Line, and the man for whom Hailey, Idaho was named. The purchase price of the 160 acres was $5,000.

Putting the poor to work, feeding them, and paying them a little money probably worked in some cases. But it soon became a place to send troublesome citizens the county didn’t know what else to do with. Boise’s notorious drunk, “Jimmy the Stiff” Hogan spent time there more than once. His only objection to the place was that there were “too many bums.”

It turned out that not everyone sent to the farm was capable of work and many of them were unhealthy. Over the years the facility became rundown and mostly ignored by a string of superintendents more interested in padding their pockets than helping the poor. The main building became a place to house orphans, the sick, and the senile, something it wasn’t intended for.

In 1915, J.K. White, state sanitary inspector, paid a visit to the Ada County Poor Farm. His recommendation was “to do away entirely with this old dilapidated, germ laden, bug infested building, and the beds and bedding.” He went on to say, “The system of having these feeble old men take care of their own beds, wash their own clothing and take care of themselves, with no one directly in charge to see that they do it, is nothing short of criminal.”

A few months later the county closed the poor farm and purchased a site on Fairview where they constructed a two-story nursing home that was much better designed to care for the needs of the sick and indigent.

The Ada County Poor Farm was started with the best of intentions. The January 26, 1883 edition of the Idaho Statesman opined that “Some provision must be made for the care of the poor. Our present county hospital system is for the care of the indigent sick, idiotic and insane. The poor, or that class which may be in destitute circumstances, is not included in the hospital contract.”

The county purchased the property for the Poor Farm from John Hailey, owner of the Pioneer Stage Line, and the man for whom Hailey, Idaho was named. The purchase price of the 160 acres was $5,000.

Putting the poor to work, feeding them, and paying them a little money probably worked in some cases. But it soon became a place to send troublesome citizens the county didn’t know what else to do with. Boise’s notorious drunk, “Jimmy the Stiff” Hogan spent time there more than once. His only objection to the place was that there were “too many bums.”

It turned out that not everyone sent to the farm was capable of work and many of them were unhealthy. Over the years the facility became rundown and mostly ignored by a string of superintendents more interested in padding their pockets than helping the poor. The main building became a place to house orphans, the sick, and the senile, something it wasn’t intended for.

In 1915, J.K. White, state sanitary inspector, paid a visit to the Ada County Poor Farm. His recommendation was “to do away entirely with this old dilapidated, germ laden, bug infested building, and the beds and bedding.” He went on to say, “The system of having these feeble old men take care of their own beds, wash their own clothing and take care of themselves, with no one directly in charge to see that they do it, is nothing short of criminal.”

A few months later the county closed the poor farm and purchased a site on Fairview where they constructed a two-story nursing home that was much better designed to care for the needs of the sick and indigent.

Published on December 23, 2021 04:00

December 22, 2021

Jesse Owens Stays Overnight in Boise (Tap to Read)

Jesse Owens was one the biggest Olympic heroes of all time. When he took four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics in Germany, it put the lie to Hitler’s claims of Aryan superiority.

After his Olympic success, Owens often struggled to make a living. For a time, he put on exhibitions where he traveled around the country racing local runners in the 100-yard dash, giving them a 20-yard head start. He also raced against horses, preferring thoroughbreds that tended to startle when the starting gun was fired. That gave him a little edge.

Owens took a little swing through Idaho in 1945, appearing in Idaho Falls, Payette, and Boise. In Payette, he beat Payette Lady, a thoroughbred owned by Ike Whiteley. No time for his run was recorded.

In Boise, the holder of seven world records, ran for a crowd of 3500 at Airway Park. His appearance in the Capitol City wasn’t against horses, but select members of the Globetrotters and Bearded Davidites, exhibition baseball teams. The Statesman reported that “Owens won as he pleased, crossing the line first in the century after giving his opponents a 10-yard lead; then running the low hurdles while two players ran on the flat and finally circling the bases against four opponents, each running only one base.”

The crowd applauded, glad to welcome Owens to Boise. But the welcome was not universal. No Boise hotel would rent a room to the Black man. He stayed instead with Warner and Clara Terrell in their house on 15th Street.

After his Olympic success, Owens often struggled to make a living. For a time, he put on exhibitions where he traveled around the country racing local runners in the 100-yard dash, giving them a 20-yard head start. He also raced against horses, preferring thoroughbreds that tended to startle when the starting gun was fired. That gave him a little edge.

Owens took a little swing through Idaho in 1945, appearing in Idaho Falls, Payette, and Boise. In Payette, he beat Payette Lady, a thoroughbred owned by Ike Whiteley. No time for his run was recorded.

In Boise, the holder of seven world records, ran for a crowd of 3500 at Airway Park. His appearance in the Capitol City wasn’t against horses, but select members of the Globetrotters and Bearded Davidites, exhibition baseball teams. The Statesman reported that “Owens won as he pleased, crossing the line first in the century after giving his opponents a 10-yard lead; then running the low hurdles while two players ran on the flat and finally circling the bases against four opponents, each running only one base.”

The crowd applauded, glad to welcome Owens to Boise. But the welcome was not universal. No Boise hotel would rent a room to the Black man. He stayed instead with Warner and Clara Terrell in their house on 15th Street.

Published on December 22, 2021 04:00

December 21, 2021

Wilson Rawls (Tap to Read)

Writers who struggle with self-doubt should take heart from the story of Wilson Rawls.

Born in Oklahoma, in 1913, Rawls would remember and long for his youth in the Ozark Hills by writing countless stories, most of which went up in smoke. The Depression saw his near-destitute family set out for California in 1929, hoping for a better life. Their car broke down near Albuquerque. His father found a job in a nearby toothpaste factory, so they never made it to the Coast.

Rawls became a carpenter and travelled widely plying his trade. He worked wood in Alaska, Canada, and South America. He got into a bit of trouble along the way, serving time twice in Oklahoma and once in New Mexico. Construction work finally brought him to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) site near Idaho Falls. He lived in a cabin near Mud Lake. It was on that Idaho job that he met his future wife, Sophie Ann Styczinski who was a budget analyst for the AEC. They married in 1958, just a couple of years before the carpenter became a novelist.

If editors had seen his early manuscripts, they might have thought he was better suited for carpentry than writing. The drafts were full of spelling and grammatical errors. He knew that and was ashamed that he was not a better writer. When he and Sophie were married, rather than show her his work, he set fire to five novel manuscripts and countless short stories and novelettes.

But the storyteller inside kept gnawing at him. During the winter, when construction work wasn’t available, he found himself with nothing to do.

“For three weeks I laid around the apartment and nearly went crazy,” Rawls told a reporter for the Idaho Statesman in 1961. “I told my wife my terrible secret. Never told anyone before. Not even my mother. I told her I had this great and awful desire to write.”

Sophie encouraged him. She bought him a pencil and a ruled tablet, and told him to sit down at the kitchen table and write. He re-wrote the novel three times in a year. When he had it right, Sophie took over. She edited it and typed it up. Then she mailed to the Saturday Evening Post. They paid $8,000 to serialize the story that would become his best-known novel, Where the Red Fern Grows. It was set in the Ozark Hills where he grew up trailing hounds with him as he explored.

In the Statesman article written to promote an appearance by the author at The Book Shop, Rawls said, “My writings are full of emotions. Most of ‘em kinda sad. Why, I had a letter from a schoolteacher say her whole class of little ones had to be taken out and git their faces washed from cryin’ so much when she read parts of my book out loud.”

Where the Red Fern Grows (1961) and his second novel Summer of the Monkeys (1976) each won multiple awards. Rawls passed away in 1984.

This sculpture in honor of Wilson Rawls and his books stands in front of the Idaho Falls Library. Called “Dreams Can Come True,” it depicts three characters from Where the Red Fern Grows, the boy Billy Coleman and two coonhounds. The sculpture is by Marilyn Hoff Hansen.

This sculpture in honor of Wilson Rawls and his books stands in front of the Idaho Falls Library. Called “Dreams Can Come True,” it depicts three characters from Where the Red Fern Grows, the boy Billy Coleman and two coonhounds. The sculpture is by Marilyn Hoff Hansen.

Born in Oklahoma, in 1913, Rawls would remember and long for his youth in the Ozark Hills by writing countless stories, most of which went up in smoke. The Depression saw his near-destitute family set out for California in 1929, hoping for a better life. Their car broke down near Albuquerque. His father found a job in a nearby toothpaste factory, so they never made it to the Coast.

Rawls became a carpenter and travelled widely plying his trade. He worked wood in Alaska, Canada, and South America. He got into a bit of trouble along the way, serving time twice in Oklahoma and once in New Mexico. Construction work finally brought him to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) site near Idaho Falls. He lived in a cabin near Mud Lake. It was on that Idaho job that he met his future wife, Sophie Ann Styczinski who was a budget analyst for the AEC. They married in 1958, just a couple of years before the carpenter became a novelist.

If editors had seen his early manuscripts, they might have thought he was better suited for carpentry than writing. The drafts were full of spelling and grammatical errors. He knew that and was ashamed that he was not a better writer. When he and Sophie were married, rather than show her his work, he set fire to five novel manuscripts and countless short stories and novelettes.

But the storyteller inside kept gnawing at him. During the winter, when construction work wasn’t available, he found himself with nothing to do.

“For three weeks I laid around the apartment and nearly went crazy,” Rawls told a reporter for the Idaho Statesman in 1961. “I told my wife my terrible secret. Never told anyone before. Not even my mother. I told her I had this great and awful desire to write.”

Sophie encouraged him. She bought him a pencil and a ruled tablet, and told him to sit down at the kitchen table and write. He re-wrote the novel three times in a year. When he had it right, Sophie took over. She edited it and typed it up. Then she mailed to the Saturday Evening Post. They paid $8,000 to serialize the story that would become his best-known novel, Where the Red Fern Grows. It was set in the Ozark Hills where he grew up trailing hounds with him as he explored.

In the Statesman article written to promote an appearance by the author at The Book Shop, Rawls said, “My writings are full of emotions. Most of ‘em kinda sad. Why, I had a letter from a schoolteacher say her whole class of little ones had to be taken out and git their faces washed from cryin’ so much when she read parts of my book out loud.”

Where the Red Fern Grows (1961) and his second novel Summer of the Monkeys (1976) each won multiple awards. Rawls passed away in 1984.

This sculpture in honor of Wilson Rawls and his books stands in front of the Idaho Falls Library. Called “Dreams Can Come True,” it depicts three characters from Where the Red Fern Grows, the boy Billy Coleman and two coonhounds. The sculpture is by Marilyn Hoff Hansen.

This sculpture in honor of Wilson Rawls and his books stands in front of the Idaho Falls Library. Called “Dreams Can Come True,” it depicts three characters from Where the Red Fern Grows, the boy Billy Coleman and two coonhounds. The sculpture is by Marilyn Hoff Hansen.

Published on December 21, 2021 04:00