Rick Just's Blog, page 108

December 9, 2021

It's YOU-stick (Tap to Read)

My GPS mapping system disagrees with most people in Boise when it comes to pronouncing the name Ustick. Boiseans typically pronounce it YOU-stick. The disembodied voice that comes out of my dashboard insists it’s UH-stick. So does the voice that comes out of my computer on HowToProunouce.com.

I’m sticking with the traditional Boise pronunciation because neither of the computer voices actually knew Harlan Page Ustick, and many Boiseans did, once.

It was Dr. Harlan P. Ustick, to be exact. Ustick, who was born in Ohio, was a prominent Boise physician who specialized in eye and ear maladies beginning in 1892. In the Treasure Valley he is most remembered for creating the town of Ustick as a development half a dozen miles outside of Boise. Ustick, the man, organized the Boise Valley Railway company with his partner Watson Donaldson. Ustick, the community, was founded in 1908 as the developers sold off five- and ten-acre lots of farmland “with terms so easy anyone can buy this.”

Harlan Ustick was also a partner in the Boise Gas and Light Company, which powered the railway. The tracks and cars would later become part of the system remembered today as the Interurban.

Ustick never did get big. Here we’re talking about the town, not making a judgment on the girth of its founder. It was about three blocks in size, boasting a bank, two churches, a school, a few retail stores, and an Interuban depot. It was known for its irrigated orchards in its heyday.

Dr. Ustick, a man of many interests, was also an orchardist, and secretary of the Southern Idaho Fruit Growers Association. He raised mostly plums (to dry for prunes), apples, and peaches. In 1902 he had 40 acres of apple orchards and 30 acres of plums, which brought in $7,500 when freighted to the east and to California.

There are traces of the little community along and near Ustick Road. The bank building is probably the most prominent. Dr. Ustick founded the bank upon the creation of the town in 1908. It closed in 1911. The building can still be seen today on the corner of Ustick Road and Mumbarto Avenue. The Ustick School is down Mumbarto a bit. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places it is today a residence.

The town’s founder had many investments, including in the Cinnabar Mine near Yellow Pine. He was there when he wrote his last letter to his wife, telling of the wonderful prospects of the mine, but complaining about the high altitude. He had been taking strychnine to stimulate his heart. Mrs. Ustick, according to an article in the September 28, 1917 edition of the Idaho Statesman, had written back to her husband pleading with him to return home. “If the altitude is affecting your health, come home at once; the richest mine in the state is not worth risking your health for.” He never got the letter. Dr. Harlan Page Ustick died on September 26, 1917 in Yellow Pine from heart disease.

The town that bore his name lasted about 50 years, with the post office closing down in 1958.

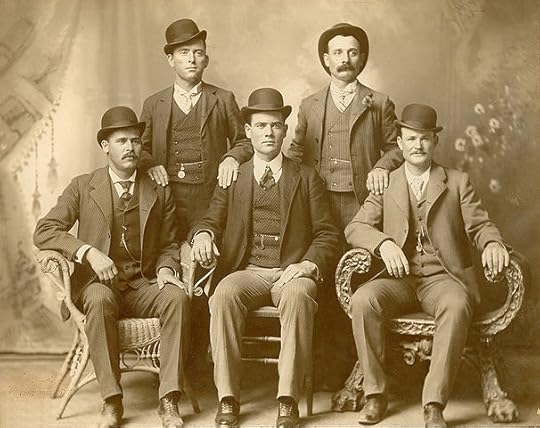

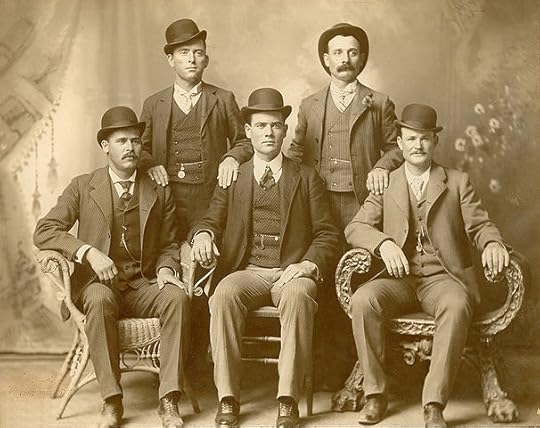

Doctor Harlan P. Ustick is the man in the top hat, at the “Silver Spike” ceremony for the Boise Valley Railway Company, which he operated. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 64-57-8.

Doctor Harlan P. Ustick is the man in the top hat, at the “Silver Spike” ceremony for the Boise Valley Railway Company, which he operated. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 64-57-8.

I’m sticking with the traditional Boise pronunciation because neither of the computer voices actually knew Harlan Page Ustick, and many Boiseans did, once.

It was Dr. Harlan P. Ustick, to be exact. Ustick, who was born in Ohio, was a prominent Boise physician who specialized in eye and ear maladies beginning in 1892. In the Treasure Valley he is most remembered for creating the town of Ustick as a development half a dozen miles outside of Boise. Ustick, the man, organized the Boise Valley Railway company with his partner Watson Donaldson. Ustick, the community, was founded in 1908 as the developers sold off five- and ten-acre lots of farmland “with terms so easy anyone can buy this.”

Harlan Ustick was also a partner in the Boise Gas and Light Company, which powered the railway. The tracks and cars would later become part of the system remembered today as the Interurban.

Ustick never did get big. Here we’re talking about the town, not making a judgment on the girth of its founder. It was about three blocks in size, boasting a bank, two churches, a school, a few retail stores, and an Interuban depot. It was known for its irrigated orchards in its heyday.

Dr. Ustick, a man of many interests, was also an orchardist, and secretary of the Southern Idaho Fruit Growers Association. He raised mostly plums (to dry for prunes), apples, and peaches. In 1902 he had 40 acres of apple orchards and 30 acres of plums, which brought in $7,500 when freighted to the east and to California.

There are traces of the little community along and near Ustick Road. The bank building is probably the most prominent. Dr. Ustick founded the bank upon the creation of the town in 1908. It closed in 1911. The building can still be seen today on the corner of Ustick Road and Mumbarto Avenue. The Ustick School is down Mumbarto a bit. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places it is today a residence.

The town’s founder had many investments, including in the Cinnabar Mine near Yellow Pine. He was there when he wrote his last letter to his wife, telling of the wonderful prospects of the mine, but complaining about the high altitude. He had been taking strychnine to stimulate his heart. Mrs. Ustick, according to an article in the September 28, 1917 edition of the Idaho Statesman, had written back to her husband pleading with him to return home. “If the altitude is affecting your health, come home at once; the richest mine in the state is not worth risking your health for.” He never got the letter. Dr. Harlan Page Ustick died on September 26, 1917 in Yellow Pine from heart disease.

The town that bore his name lasted about 50 years, with the post office closing down in 1958.

Doctor Harlan P. Ustick is the man in the top hat, at the “Silver Spike” ceremony for the Boise Valley Railway Company, which he operated. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 64-57-8.

Doctor Harlan P. Ustick is the man in the top hat, at the “Silver Spike” ceremony for the Boise Valley Railway Company, which he operated. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 64-57-8.

Published on December 09, 2021 04:00

December 8, 2021

The Spud Bowl (Tap to Read)

The Idaho Potato Bowl has been around for a while. It wasn’t the first “bowl” named after the state’s famous tuber. That honor probably goes to Idaho State College’s “Spud Bowl.” It wasn’t a bowl game, though a sports columnist for the Idaho State Journal opined that there should be a bowl game with that name back in 1949.

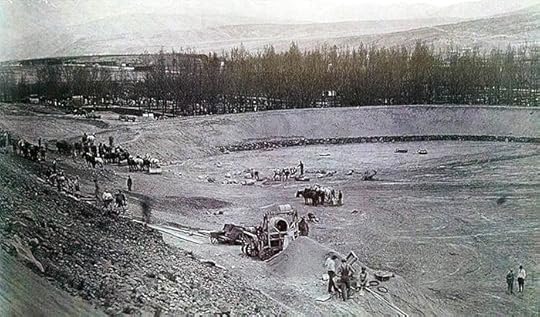

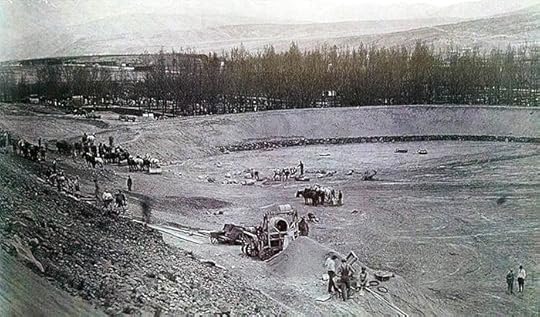

The “Spud Bowl” was the college football field built by the Civil Works Administration (CWA) in 1936. CWA was one of the New Deal projects that came out of the Roosevelt administration. The photo below shows men scraping out the shape of the Spud Bowl.

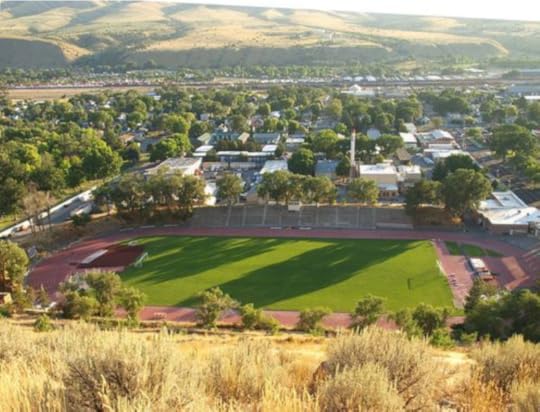

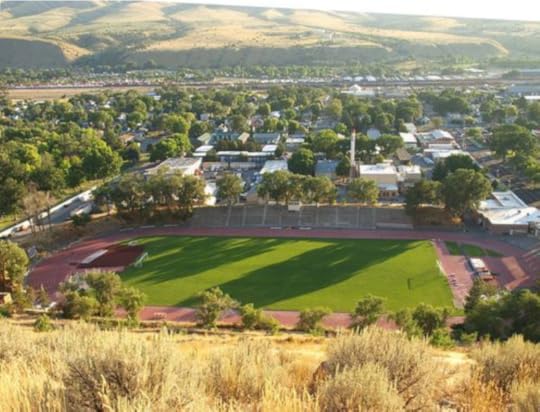

The football field was renamed for William E. “Bud” Davis, who was Idaho State University President from 1965-1975.

The color photo at the bottom of this post is of Davis Field as it looks today. It has a seating capacity of 4,000 fans.

The “Spud Bowl” was the college football field built by the Civil Works Administration (CWA) in 1936. CWA was one of the New Deal projects that came out of the Roosevelt administration. The photo below shows men scraping out the shape of the Spud Bowl.

The football field was renamed for William E. “Bud” Davis, who was Idaho State University President from 1965-1975.

The color photo at the bottom of this post is of Davis Field as it looks today. It has a seating capacity of 4,000 fans.

Published on December 08, 2021 04:00

December 7, 2021

Exploding Billiard Balls, and More! (Tap to Read)

I traveled down a path of good intentions today, trimmed in ivory. It led past the carcasses of elephants to gigatons of trash.

My exploration started with an article from a story in the August 4, 1864 edition of the Idaho Statesman. Headlined, “Where Our Ivory Comes From,” the piece caught my attention because I thought the answer was all too obvious. Ivory has been treasured by artisans for centuries because it is easy to carve yet durable. Elephants have been the largest source of ivory, though walrus, hippopotamus, narwhal, sperm whales, and elk all provide ivory. Providing it usually costs the animal its life.

But the 1864 article was not about elephants.

“You carry a beautiful cane—it cost $3.50—$1.50 extra, on account of its beautiful pure ivory head. Your wife has a costly fan, with a pure ivory handle. In your pocket is your pure ivory-handled pocketknife, very pretty and fine. On your table is a set of knives and forks with pure ivory handles, and little they have cost for being pure ivory. The ring in which are the reins of your costly double harness is pure ivory. The handles of parasols are pure ivory—and so on, with many articles useful and ornamental. But it happens that this “pure ivory” is manufactured from the shin bones of the dead horses of the U.S. Army.”

Well, that took a turn. I found the article by accident, which is often the case when I’m looking for interesting Idaho tidbits. I was searching for something about harness when this little piece popped up because it included that word in the text.

Encouraged by the quirkiness the article offered, I did a quick search on ivory. And that’s where the trouble began.

Early billiard balls were made of ivory. It gave the perfect heft, click, and bounce players enjoyed. But in the 1860s there was something of a billiard ball panic because ivory was allegedly in short supply. It wasn’t. Nevertheless, the belief that it was set billiard ball manufacturers on a quest for a material to replace ivory balls.

British inventor Alan Parkes came up with something he called Parkesine in 1862. It was the first plastic. It didn’t work well for billiard balls, so the quest was still on for the perfect synthetic material. John Wesley Hyatt, hoping to win a $10,000 prize from Big Billiard (a name I made up to represent the industry, so don’t call me on that) came up with celluloid. Celluloid is better known for its use in early motion picture film stock. That early film was highly flammable, and billiard balls made from celluloid had a similar, annoying feature. They exploded.

Exploding billiard balls would have been a health hazard for those who hung out in establishments where the game was played, but the explosions weren’t like grenades going off. They occasionally made a sharp pop, causing little damage even to the felt on billiard tables. The percussion sounded much like a gunshot, which reportedly caused quite a few “sports” to drop the hand of cards they’d been dealt to frantically look around the room.

Today, billiard balls are made from resin, another type of plastic. And, today, we are buried by plastic of all kinds because it shares something with the ivory it replaced. It is durable. Too durable, as it turns out.

One last note: Inventor John Wesley Hyatt never received the $10,000 prize, but he did start the Albany Billiard Ball Company. It stayed in business for 118 years.

My exploration started with an article from a story in the August 4, 1864 edition of the Idaho Statesman. Headlined, “Where Our Ivory Comes From,” the piece caught my attention because I thought the answer was all too obvious. Ivory has been treasured by artisans for centuries because it is easy to carve yet durable. Elephants have been the largest source of ivory, though walrus, hippopotamus, narwhal, sperm whales, and elk all provide ivory. Providing it usually costs the animal its life.

But the 1864 article was not about elephants.

“You carry a beautiful cane—it cost $3.50—$1.50 extra, on account of its beautiful pure ivory head. Your wife has a costly fan, with a pure ivory handle. In your pocket is your pure ivory-handled pocketknife, very pretty and fine. On your table is a set of knives and forks with pure ivory handles, and little they have cost for being pure ivory. The ring in which are the reins of your costly double harness is pure ivory. The handles of parasols are pure ivory—and so on, with many articles useful and ornamental. But it happens that this “pure ivory” is manufactured from the shin bones of the dead horses of the U.S. Army.”

Well, that took a turn. I found the article by accident, which is often the case when I’m looking for interesting Idaho tidbits. I was searching for something about harness when this little piece popped up because it included that word in the text.

Encouraged by the quirkiness the article offered, I did a quick search on ivory. And that’s where the trouble began.

Early billiard balls were made of ivory. It gave the perfect heft, click, and bounce players enjoyed. But in the 1860s there was something of a billiard ball panic because ivory was allegedly in short supply. It wasn’t. Nevertheless, the belief that it was set billiard ball manufacturers on a quest for a material to replace ivory balls.

British inventor Alan Parkes came up with something he called Parkesine in 1862. It was the first plastic. It didn’t work well for billiard balls, so the quest was still on for the perfect synthetic material. John Wesley Hyatt, hoping to win a $10,000 prize from Big Billiard (a name I made up to represent the industry, so don’t call me on that) came up with celluloid. Celluloid is better known for its use in early motion picture film stock. That early film was highly flammable, and billiard balls made from celluloid had a similar, annoying feature. They exploded.

Exploding billiard balls would have been a health hazard for those who hung out in establishments where the game was played, but the explosions weren’t like grenades going off. They occasionally made a sharp pop, causing little damage even to the felt on billiard tables. The percussion sounded much like a gunshot, which reportedly caused quite a few “sports” to drop the hand of cards they’d been dealt to frantically look around the room.

Today, billiard balls are made from resin, another type of plastic. And, today, we are buried by plastic of all kinds because it shares something with the ivory it replaced. It is durable. Too durable, as it turns out.

One last note: Inventor John Wesley Hyatt never received the $10,000 prize, but he did start the Albany Billiard Ball Company. It stayed in business for 118 years.

Published on December 07, 2021 04:00

December 6, 2021

The Sacagawea Dollar (Tap to Read)

One of the more beautiful coins ever produced by the U.S. Mint features the face of a living Idahoan. U.S. coins don’t honor living individuals, so you might have done a double take when you read that. The coin honors Sacagawea, the Shoshone woman who was such an important part of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

If you spell her name “Sacajawea,” and pronounce it with a soft “J,” you’re not alone. Many Idahoans learned to spell and pronounce it that way growing up. Spelling it with a “G” and using the hard “G” sound to pronounce it seems a little more common nowadays.

The woman depicted on the coin is an artist’s rendition of Sacagawea. The artist, Glenna Maxey Goodacre, used Idahoan and Shoshone-Bannock Tribal Member Randy‘L Teton as a model for the coin. Goodacre is also known for designing the Vietnam Women’s Memorial in Washington, DC.

Randy’L He-dow Teton was chosen as the model for the coin by Goodacre when the artist visited the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, where Teton’s mother was employed. Randy’L was going to school at the University of New Mexico at the time.

A graduate of Blackfoot High School, Randy’L Teton today is the public affairs manager of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes.

Beautiful though the “golden dollar” is, it’s rare to see one in circulation today. You can get them easily enough, but people simply don’t carry coins the way they once did.

[image error] This is a promotional card for the Sacajawea dollar, featuring two photos of Randy’L Teton.

If you spell her name “Sacajawea,” and pronounce it with a soft “J,” you’re not alone. Many Idahoans learned to spell and pronounce it that way growing up. Spelling it with a “G” and using the hard “G” sound to pronounce it seems a little more common nowadays.

The woman depicted on the coin is an artist’s rendition of Sacagawea. The artist, Glenna Maxey Goodacre, used Idahoan and Shoshone-Bannock Tribal Member Randy‘L Teton as a model for the coin. Goodacre is also known for designing the Vietnam Women’s Memorial in Washington, DC.

Randy’L He-dow Teton was chosen as the model for the coin by Goodacre when the artist visited the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, where Teton’s mother was employed. Randy’L was going to school at the University of New Mexico at the time.

A graduate of Blackfoot High School, Randy’L Teton today is the public affairs manager of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes.

Beautiful though the “golden dollar” is, it’s rare to see one in circulation today. You can get them easily enough, but people simply don’t carry coins the way they once did.

[image error] This is a promotional card for the Sacajawea dollar, featuring two photos of Randy’L Teton.

Published on December 06, 2021 04:00

December 5, 2021

The Tragedy of Pearl Royal Hendrickson (Tap to Read)

Pearl Royal Hendrickson had a name that seemed aspirational. Though he lived in a ramshackle cabin in the Boise foothills, he was not without aspiration. Hendrickson was looking for wealth in the hills above Boise, like countless miners before him all across the State of Idaho. With the wealth, had he found it, might have come fame. Instead, his hunt for gallium would bring him only infamy.

His quest for gallium seems a little odd. Today the soft, silvery metal is used in electronic circuit boards, semiconductors, and LEDs. Why he thought it valuable in 1940 is open to conjecture. Gallium is akin to mercury in that it softens to a liquid when held in your hand. Playing with mercury that way is dangerous, but gallium seems relatively safe. Perhaps the changeable nature of the element held some fascination for Hendrickson.

Hendrickson was often called a squatter, though he may have originally had permission from the property owner to build his cabin on the foothills ridge near Bogus Basin. He and the landowner came to a dispute in 1936 when Hendrickson cut a cord of wood from the nearby forest. The property owner took him to court. Scant coverage of the matter appeared in the Idaho Statesman at the time, focusing mostly on the cost of the trials—an estimated $100—as compared with the value of the wood, $5. Two juries heard the case. The first couldn’t agree on a verdict and the second found Hendrickson not guilty.

The squatter was back in court again in 1939, this time fighting for his mineral rights in federal court against the Forest Service. Squatter was the appropriate term for the man by that time, because the Forest Service had purchased the property where he lived and wanted him off. Their argument against his mineral rights claim was that no mineral of worth had been discovered. This time Hendrickson lost the case.

In the early morning of Wednesday, July 31, 1940, Deputy U.S. Marshall John Glenn and Boise Police Captain George Haskin caught a cab and took it up the dirt road into the foothills for the purpose of serving a contempt of court citation to Hendrickson. They left the cab and driver on the road and walked in to Hendrickson’s cabin, about three quarters of a mile away.

While Haskin covered the window of the cabin, Glenn pounded on the door and roused Hendrickson. The Marshall said a few words about why they were there. Hendrickson, who had frequently said they would have to take him from his cabin boots first, shot the man twice. Glenn staggered away a few feet and fell dead. Haskin ran around the cabin and took cover. A few minutes later he made his way back to the taxi, and then back to town for reinforcements.

About 8 am law enforcement began to arrive at the cabin. U.S. Marshall George Meffan was the first, driving his car right up to the cabin where it stalled. Before he could get out Hendrickson shot him dead behind the wheel.

That’s when the siege—and that’s the word for it—began. Law enforcement officers from Boise, Ada County, Idaho City, Moscow, and the FBI surrounded the cabin and fired into it with everything they had for hours. And they had a lot. They used rifles, pistols, submachine guns, and even sticks of dynamite on Hendrickson. Sheltering in bushes and watching the situation develop were the county coroner and “girl reporter” Nina Varian. The fight went on for some four hours.

Varian, under the headline, “Girl Reporter Describes Tragic Drama of Man-Hunt; Negro Was Obsessed,” described it this way: “I saw grisly hell let loose in a lovely heaven of blue sky, green timber, gold sunshine. I crouched in soft, brown earth against hot gray rocks as the whine and roar of guns blasted all around me… I looked at two dead men—one sprawled like a blue lump on the ground, the other slumped over the wheel of his car, an inert mass; and I watched the frail hut that housed a doomed man.

“It was a man-hunt. Grim, relentless, terrible. Avenging man, hunting his kind; ruled by emotions muddied up from the dregs of ages past. I know now what ugly things are covered by the cloak of civilization.”

The outcome was never in doubt once the shooting started. Hendrickson fought for hours using his own weapons and the weapons of the men he killed. Eventually, he himself was killed.

The battle was covered on three pages of the newspaper on August 1, with stories from eyewitnesses, a timeline, multiple photos, and a sketch of scene. “Girl reporter” wasn’t the only term that jars today. Hendrickson was referred to as a negro and a colored man, both terms long since put to rest in most newspapers. The photos included one of Glenn’s body being unceremoniously carried away by two men.

Pearl Royal Hendrickson, 50, was carried off the same way, feet first, as he had promised many times if officials tried to evict him.

His quest for gallium seems a little odd. Today the soft, silvery metal is used in electronic circuit boards, semiconductors, and LEDs. Why he thought it valuable in 1940 is open to conjecture. Gallium is akin to mercury in that it softens to a liquid when held in your hand. Playing with mercury that way is dangerous, but gallium seems relatively safe. Perhaps the changeable nature of the element held some fascination for Hendrickson.

Hendrickson was often called a squatter, though he may have originally had permission from the property owner to build his cabin on the foothills ridge near Bogus Basin. He and the landowner came to a dispute in 1936 when Hendrickson cut a cord of wood from the nearby forest. The property owner took him to court. Scant coverage of the matter appeared in the Idaho Statesman at the time, focusing mostly on the cost of the trials—an estimated $100—as compared with the value of the wood, $5. Two juries heard the case. The first couldn’t agree on a verdict and the second found Hendrickson not guilty.

The squatter was back in court again in 1939, this time fighting for his mineral rights in federal court against the Forest Service. Squatter was the appropriate term for the man by that time, because the Forest Service had purchased the property where he lived and wanted him off. Their argument against his mineral rights claim was that no mineral of worth had been discovered. This time Hendrickson lost the case.

In the early morning of Wednesday, July 31, 1940, Deputy U.S. Marshall John Glenn and Boise Police Captain George Haskin caught a cab and took it up the dirt road into the foothills for the purpose of serving a contempt of court citation to Hendrickson. They left the cab and driver on the road and walked in to Hendrickson’s cabin, about three quarters of a mile away.

While Haskin covered the window of the cabin, Glenn pounded on the door and roused Hendrickson. The Marshall said a few words about why they were there. Hendrickson, who had frequently said they would have to take him from his cabin boots first, shot the man twice. Glenn staggered away a few feet and fell dead. Haskin ran around the cabin and took cover. A few minutes later he made his way back to the taxi, and then back to town for reinforcements.

About 8 am law enforcement began to arrive at the cabin. U.S. Marshall George Meffan was the first, driving his car right up to the cabin where it stalled. Before he could get out Hendrickson shot him dead behind the wheel.

That’s when the siege—and that’s the word for it—began. Law enforcement officers from Boise, Ada County, Idaho City, Moscow, and the FBI surrounded the cabin and fired into it with everything they had for hours. And they had a lot. They used rifles, pistols, submachine guns, and even sticks of dynamite on Hendrickson. Sheltering in bushes and watching the situation develop were the county coroner and “girl reporter” Nina Varian. The fight went on for some four hours.

Varian, under the headline, “Girl Reporter Describes Tragic Drama of Man-Hunt; Negro Was Obsessed,” described it this way: “I saw grisly hell let loose in a lovely heaven of blue sky, green timber, gold sunshine. I crouched in soft, brown earth against hot gray rocks as the whine and roar of guns blasted all around me… I looked at two dead men—one sprawled like a blue lump on the ground, the other slumped over the wheel of his car, an inert mass; and I watched the frail hut that housed a doomed man.

“It was a man-hunt. Grim, relentless, terrible. Avenging man, hunting his kind; ruled by emotions muddied up from the dregs of ages past. I know now what ugly things are covered by the cloak of civilization.”

The outcome was never in doubt once the shooting started. Hendrickson fought for hours using his own weapons and the weapons of the men he killed. Eventually, he himself was killed.

The battle was covered on three pages of the newspaper on August 1, with stories from eyewitnesses, a timeline, multiple photos, and a sketch of scene. “Girl reporter” wasn’t the only term that jars today. Hendrickson was referred to as a negro and a colored man, both terms long since put to rest in most newspapers. The photos included one of Glenn’s body being unceremoniously carried away by two men.

Pearl Royal Hendrickson, 50, was carried off the same way, feet first, as he had promised many times if officials tried to evict him.

Published on December 05, 2021 04:00

December 4, 2021

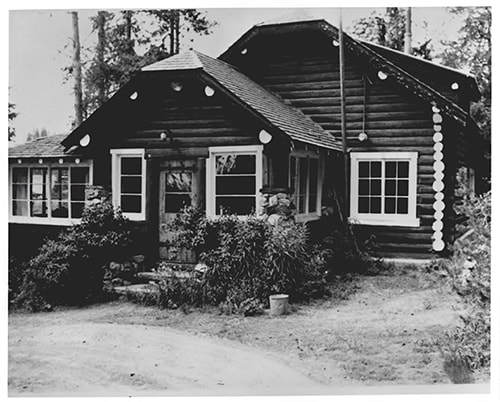

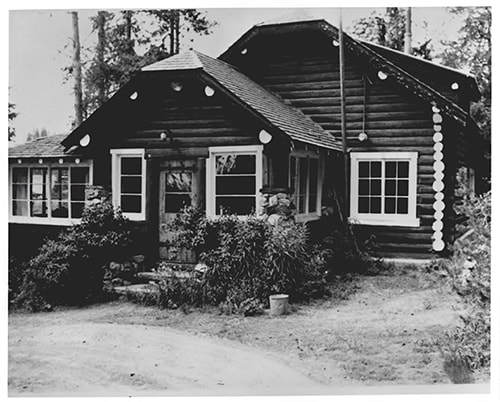

Johnny Sack's Cabin (Tap to Read)

John Parsons sent me a link to a cool 3D tour of Johnny Sack’s cabin in Island Park. I decided to write a little about the cabin and share the link with you.

The cabin, built by the hands of Johnny Sack, isn’t the typical ramshackle residence you might expect from an Idaho loner. It’s a piece of art.

Sack and his brother Andy, arrived in Island Park by train in June 1909, during a blizzard, according to the Fremont County website. The brothers mostly worked cattle in the area for years before Johnny started building cabins and furniture for a living. He’d had some training working for the Studebaker Wagon Corporation, which morphed into the Studebaker car company.

In 1929, Johnny Sack leased a site at Big Springs for $4.15 a year from the Forest Service and began building his own cabin. It took about three years to complete. The main part of the log bungalow is about 20 x 27 feet. In the 1972 National Register of Historic Places application for the cabin, it states “It is considered to be the work of a master craftsman.”

You can read more about the exquisite little cabin and its builder on the website and take a virtual tour of the interior. Take special note of the unique pieces of furniture also carved and assembled by Sack.

1972 photo of the Johnny Sack cabin from its National Register of Historic Places application.

1972 photo of the Johnny Sack cabin from its National Register of Historic Places application.

The cabin, built by the hands of Johnny Sack, isn’t the typical ramshackle residence you might expect from an Idaho loner. It’s a piece of art.

Sack and his brother Andy, arrived in Island Park by train in June 1909, during a blizzard, according to the Fremont County website. The brothers mostly worked cattle in the area for years before Johnny started building cabins and furniture for a living. He’d had some training working for the Studebaker Wagon Corporation, which morphed into the Studebaker car company.

In 1929, Johnny Sack leased a site at Big Springs for $4.15 a year from the Forest Service and began building his own cabin. It took about three years to complete. The main part of the log bungalow is about 20 x 27 feet. In the 1972 National Register of Historic Places application for the cabin, it states “It is considered to be the work of a master craftsman.”

You can read more about the exquisite little cabin and its builder on the website and take a virtual tour of the interior. Take special note of the unique pieces of furniture also carved and assembled by Sack.

1972 photo of the Johnny Sack cabin from its National Register of Historic Places application.

1972 photo of the Johnny Sack cabin from its National Register of Historic Places application.

Published on December 04, 2021 04:00

December 3, 2021

Those Beehive Charcoal Kilns (Tap to Read)

The charcoal kilns near Leadore resemble the skep or beehive depicted on the state flag of Utah. Made from local clay, they fit in well with the vast landscape of the Lemhi Valley. They are located about halfway between Salmon and Idaho Falls, some six miles west of State Highway 28.

Only four of the 16 original kilns survive today, now protected and interpreted by the US Forest Service and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The kilns are dwarfed by the towering mountains on both sides of the valley. They seem small at first, but as you approach them their scale becomes more apparent. They are 20 feet high—about the height of a two-story house—and 21-and-half feet in diameter. The circumference around the 14-inch-thick walls is about 73 feet.

Warren King of Butte, Montana, constructed the kilns in 1885 to service the needs of the Viola mine smelter across the valley in Nicholia. The kilns operated from 1885 to 1889. It was not a small operation. Some 200 men—mostly Irish, Italian, and Chinese immigrants—worked the nearby forests cutting, sawing, and transporting four-foot lengths of log, then carefully arranging them inside each kiln, stacked on end. The two-day burn reduced about 35 cords of wood to 500 pounds of charcoal.

Following a fire at the hoisting works, the Viola mine closed in 1889. The price of lead and silver kept it closed.

Locals discovered the utility of the perfectly good bricks and made most of the kilns into buildings and walls around the valley.

The Charcoal Kilns located off State Highway 28 near Leadore, Idaho. The kilns are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Charcoal Kilns located off State Highway 28 near Leadore, Idaho. The kilns are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Only four of the 16 original kilns survive today, now protected and interpreted by the US Forest Service and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The kilns are dwarfed by the towering mountains on both sides of the valley. They seem small at first, but as you approach them their scale becomes more apparent. They are 20 feet high—about the height of a two-story house—and 21-and-half feet in diameter. The circumference around the 14-inch-thick walls is about 73 feet.

Warren King of Butte, Montana, constructed the kilns in 1885 to service the needs of the Viola mine smelter across the valley in Nicholia. The kilns operated from 1885 to 1889. It was not a small operation. Some 200 men—mostly Irish, Italian, and Chinese immigrants—worked the nearby forests cutting, sawing, and transporting four-foot lengths of log, then carefully arranging them inside each kiln, stacked on end. The two-day burn reduced about 35 cords of wood to 500 pounds of charcoal.

Following a fire at the hoisting works, the Viola mine closed in 1889. The price of lead and silver kept it closed.

Locals discovered the utility of the perfectly good bricks and made most of the kilns into buildings and walls around the valley.

The Charcoal Kilns located off State Highway 28 near Leadore, Idaho. The kilns are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Charcoal Kilns located off State Highway 28 near Leadore, Idaho. The kilns are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Published on December 03, 2021 04:00

December 2, 2021

Butch's Bank (Tap to Read)

If Butch Cassidy had a sense of humor—and he apparently did—he would probably find it hilarious that one of the banks he robbed would one day become a museum celebrating that robbery.

Born Robert LeRoy Park in 1866 in Beaver, Utah, the man became “Butch,” a shortened version of “Butcher,” when he worked as one in Rock Springs Wyoming. The Cassidy he picked up from a friend and mentor who had that last name.

Cassidy and three “Wild Bunch” compatriots robbed the Montpelier bank on August 13, 1896, not long after he was released from prison in Wyoming where he served 18 months for stealing horses. They got away with somewhere between $5,000 and $15,000. His equally infamous sidekick, Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, better known as “The Sundance Kid,” would join the gang shortly after the Montpelier robbery.

The bank where the robbery took place was purchased and turned into a museum in 2016 by Radk Konarik. The Bank of Montpelier was the first bank chartered in the State of Idaho, opening its doors in 1891. As a museum it is now open during the summer, welcoming several thousand visitors each year who want to see the last standing bank that Butch Cassidy robbed.

Cassidy and Sundance were both killed in a shootout with the Bolivian Army in 1908, as depicted in the 1969 movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Unless they weren’t. There are many stories that say they came back to the States after their South American adventure and lived quiet lives. You can start chasing those down for fun on the Butch Cassidy Wikipedia page.

Born Robert LeRoy Park in 1866 in Beaver, Utah, the man became “Butch,” a shortened version of “Butcher,” when he worked as one in Rock Springs Wyoming. The Cassidy he picked up from a friend and mentor who had that last name.

Cassidy and three “Wild Bunch” compatriots robbed the Montpelier bank on August 13, 1896, not long after he was released from prison in Wyoming where he served 18 months for stealing horses. They got away with somewhere between $5,000 and $15,000. His equally infamous sidekick, Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, better known as “The Sundance Kid,” would join the gang shortly after the Montpelier robbery.

The bank where the robbery took place was purchased and turned into a museum in 2016 by Radk Konarik. The Bank of Montpelier was the first bank chartered in the State of Idaho, opening its doors in 1891. As a museum it is now open during the summer, welcoming several thousand visitors each year who want to see the last standing bank that Butch Cassidy robbed.

Cassidy and Sundance were both killed in a shootout with the Bolivian Army in 1908, as depicted in the 1969 movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Unless they weren’t. There are many stories that say they came back to the States after their South American adventure and lived quiet lives. You can start chasing those down for fun on the Butch Cassidy Wikipedia page.

Published on December 02, 2021 04:00

December 1, 2021

The Caxton Fire (Tap to Read)

In 1937, Caxton Printers was ready to celebrate its 30th anniversary. Starting as a printing and office services company, the printer had also begun publishing books in 1925 as Caxton Press. In January of 1937 Caxton released Idaho: A Guide in Word and Pictures, by Vardis Fisher, the first book from the Works Project Administration. It looked like a banner year for the company.

Then, on the morning of St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1937, someone in the building noticed smoke. Just after 9 am, word ran through the offices that there was a fire in the west stockroom where countless books and printing supplies were stored. Employees scramble to put the fire out with fire extinguishers, but the blaze had a good hold. Flames roared in a flash up the wall and into the second-floor offices.

There wasn’t even time to close the office safes before employees were forced to escaped through fire and smoke down the back stairs.

The head of the offset printing department on the east side of the building, G.H. Spurgeon, grabbed three expensive camera lenses before jumping through a window. Other employees scrambled to get equipment out, including two small lithographic presses.

A stroke of luck protected many of the company’s records. One of the office safes, door open, crashed through the weakened floor of the building. The door slammed shut when it landed, saving the contents.

The fire did not reach the basement but, the water firefighters used to quench the blaze cascaded into the $50,000 worth of school supplies stored there, ruining them.

The second edition of Fisher’s Idaho Guide was under production at the time of the fire. About 15 minutes before the alarm sounded a truckload of pictures left the lithographic department and went to the bindery room where they were destroyed.

Annuals for Northwest Nazarene college, Gooding College, the University of Idaho southern branch (now ISU), the College of Idaho, and Albion State Normal School, along with those of seven area high schools were under production at the time. The fire got them all.

Many books under production were also destroyed, but the owners and staff of the publishing company showed a remarkable resilience. As the sun was setting on the day of the fire—the largest in Caldwell history at that time—crews were working on various projects at other nearby printing companies. A meeting of the board of directors took place that same night to select equipment to be shipped in for a new plant. Orders for the equipment went out the next day.

Caxton Printers and Publishing erected a much larger building and kept one of the most famous publishing houses in the West alive. It still thrives in Caldwell today.

Why did J.H. Gipson choose to call his printing company Caxton? A man by the name of William Caxton produced the first book printed in English. That was in 1473 in Bruges, Belgium. In 1476 he was the first to bring a press to England, his home country. The first book he printed was a version of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. A.E. Gipson borrowed not only the name, but William Caxton’s printers mark (below) which is used to this day on Caxton’s books to honor that early printer.

For more on the history of Caxton Press, watch Idaho Experience on Idaho Public Television December 5. Here’s a link to a preview.

Then, on the morning of St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1937, someone in the building noticed smoke. Just after 9 am, word ran through the offices that there was a fire in the west stockroom where countless books and printing supplies were stored. Employees scramble to put the fire out with fire extinguishers, but the blaze had a good hold. Flames roared in a flash up the wall and into the second-floor offices.

There wasn’t even time to close the office safes before employees were forced to escaped through fire and smoke down the back stairs.

The head of the offset printing department on the east side of the building, G.H. Spurgeon, grabbed three expensive camera lenses before jumping through a window. Other employees scrambled to get equipment out, including two small lithographic presses.

A stroke of luck protected many of the company’s records. One of the office safes, door open, crashed through the weakened floor of the building. The door slammed shut when it landed, saving the contents.

The fire did not reach the basement but, the water firefighters used to quench the blaze cascaded into the $50,000 worth of school supplies stored there, ruining them.

The second edition of Fisher’s Idaho Guide was under production at the time of the fire. About 15 minutes before the alarm sounded a truckload of pictures left the lithographic department and went to the bindery room where they were destroyed.

Annuals for Northwest Nazarene college, Gooding College, the University of Idaho southern branch (now ISU), the College of Idaho, and Albion State Normal School, along with those of seven area high schools were under production at the time. The fire got them all.

Many books under production were also destroyed, but the owners and staff of the publishing company showed a remarkable resilience. As the sun was setting on the day of the fire—the largest in Caldwell history at that time—crews were working on various projects at other nearby printing companies. A meeting of the board of directors took place that same night to select equipment to be shipped in for a new plant. Orders for the equipment went out the next day.

Caxton Printers and Publishing erected a much larger building and kept one of the most famous publishing houses in the West alive. It still thrives in Caldwell today.

Why did J.H. Gipson choose to call his printing company Caxton? A man by the name of William Caxton produced the first book printed in English. That was in 1473 in Bruges, Belgium. In 1476 he was the first to bring a press to England, his home country. The first book he printed was a version of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. A.E. Gipson borrowed not only the name, but William Caxton’s printers mark (below) which is used to this day on Caxton’s books to honor that early printer.

For more on the history of Caxton Press, watch Idaho Experience on Idaho Public Television December 5. Here’s a link to a preview.

Published on December 01, 2021 04:00

November 30, 2021

Pop Quiz! (Tap to read)

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture. If you missed that story, click the letter for a link.

1). Which came first, the Idanha in Boise or the Idanha in Soda Springs?

A. The Idanha in Boise

B. The Idanha in Soda Springs

2). What distinction did Moroni Hicks have?

A. He was prisoner number 2 at the Idaho State Penitentiary

B. He was one of the first to sit on the LDS Quorum of 12 Apostles

C. He was the first to bring irrigation water to Rexburg

D. He was in prison for stealing a horse

E. He was the second victim of Lyda Southard

3). What Idaho town was well known for its moonshine during prohibition?

A. Franklin

B. Bayhorse

C. Huston

D. Mackay

E. Firth

4). Where was the ferry Idaho when it burned?

A. Lake Coeur d’Alene

B. The St Joe River

C. The East River

D. Priest Lake

E. The Coeur d’Alene River

5) Which of the following is true about Earl Wayland Bowman?

A. He ran a real estate newspaper called Homeseekers Monthly

B. He was orphaned at 10

C. He was known as “The Ramblin’ Kid”

D. He was the only socialist ever elected to the Idaho State Senate

E. All of the above Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

1, B

2, A

3, D

4, C

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). Which came first, the Idanha in Boise or the Idanha in Soda Springs?

A. The Idanha in Boise

B. The Idanha in Soda Springs

2). What distinction did Moroni Hicks have?

A. He was prisoner number 2 at the Idaho State Penitentiary

B. He was one of the first to sit on the LDS Quorum of 12 Apostles

C. He was the first to bring irrigation water to Rexburg

D. He was in prison for stealing a horse

E. He was the second victim of Lyda Southard

3). What Idaho town was well known for its moonshine during prohibition?

A. Franklin

B. Bayhorse

C. Huston

D. Mackay

E. Firth

4). Where was the ferry Idaho when it burned?

A. Lake Coeur d’Alene

B. The St Joe River

C. The East River

D. Priest Lake

E. The Coeur d’Alene River

5) Which of the following is true about Earl Wayland Bowman?

A. He ran a real estate newspaper called Homeseekers Monthly

B. He was orphaned at 10

C. He was known as “The Ramblin’ Kid”

D. He was the only socialist ever elected to the Idaho State Senate

E. All of the above

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)1, B

2, A

3, D

4, C

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on November 30, 2021 04:00