Rick Just's Blog, page 110

November 19, 2021

Pickett's Corral (Tap to read the story)

Pickett’s Corral is a natural amphitheater in the bluffs formed by the Payette River about five miles northeast of Emmett. Or, Picket’s Corral. Or, maybe, Picket Corral. It was named because the corral was made of pickets, so I’m going to go with Picket Corral.

It garnered a name in the first place because it was a notorious robber’s roost for a few years in the 1860s. A band of horse rustlers chose the spot because its natural shape made building a corral easy. They ran the pickets between the walls of the small box canyon and built a living quarters nearby.

Stealing horses was only part of the business. The men were adept at producing bogus gold and passing it off as the real thing. Calling the gang outlaws, though, is a little shaky. There weren’t many laws and even less enforcement in the Oregon Territory prior to 1863. When Idaho Territory came into being that year the situation didn’t improve much.

One young man who had been quietly raising watermelons and onions near Horseshoe Bend for sale to prospectors in the region took particular umbrage when he lost a horse to the Picket Corral gang. His name was William John McConnell. He and other citizens took it upon themselves to clean out Picket Corral. Some would call them vigilantes. McConnell referred to himself that way in his book, Frontier Law, that came out in 1924.

McConnell stopped in at a roadhouse in what was then called Emmettsville to have a drink while waiting for his fellow vigilantes to show up in force. Unfortunately, the toughs had heard McConnell and his men were out to get them. Several of the outlaws called McConnell outside where they confronted him. He backed up against the building and set his hands at the ready to grab his revolvers. Then he gave them a little speech.

“Show your colors,” he said. “I will make the biggest funeral ever held in this valley. You are here to murder me. I don’t think you can do it.”

He was right. Frozen in place by the man’s defiance they stood there while he read them a notice of banishment. Their ringleader left for Oregon the next day and the others scattered, abandoning Picket Corral.

The rogue sheriff elected in 1864 in Ada County, set out to avenge the treatment of some of his Picket Corral compatriots by killing McConnel. Sheriff David Updyke, who will get his own blog post soon enough, was not successful and was later hanged by vigilantes.

Vigilante McConnell did alright for himself in life. He moved to Oregon where he was elected to the state senate. In the 1880s he moved back to Idaho where he opened a general store in Moscow with a partner. McConnell was a delegate to Idaho’s constitutional convention and briefly became a U.S. Senator from Idaho. In 1893 he became Idaho’s third governor, serving until 1897. That gave his daughter, Mary, a chance to meet and marry William E. Borah. McConnell passed away in 1925 at age 85.

Picket Corral became less of a robber’s roost over the year and more of a place to have a picnic.

[image error]

It garnered a name in the first place because it was a notorious robber’s roost for a few years in the 1860s. A band of horse rustlers chose the spot because its natural shape made building a corral easy. They ran the pickets between the walls of the small box canyon and built a living quarters nearby.

Stealing horses was only part of the business. The men were adept at producing bogus gold and passing it off as the real thing. Calling the gang outlaws, though, is a little shaky. There weren’t many laws and even less enforcement in the Oregon Territory prior to 1863. When Idaho Territory came into being that year the situation didn’t improve much.

One young man who had been quietly raising watermelons and onions near Horseshoe Bend for sale to prospectors in the region took particular umbrage when he lost a horse to the Picket Corral gang. His name was William John McConnell. He and other citizens took it upon themselves to clean out Picket Corral. Some would call them vigilantes. McConnell referred to himself that way in his book, Frontier Law, that came out in 1924.

McConnell stopped in at a roadhouse in what was then called Emmettsville to have a drink while waiting for his fellow vigilantes to show up in force. Unfortunately, the toughs had heard McConnell and his men were out to get them. Several of the outlaws called McConnell outside where they confronted him. He backed up against the building and set his hands at the ready to grab his revolvers. Then he gave them a little speech.

“Show your colors,” he said. “I will make the biggest funeral ever held in this valley. You are here to murder me. I don’t think you can do it.”

He was right. Frozen in place by the man’s defiance they stood there while he read them a notice of banishment. Their ringleader left for Oregon the next day and the others scattered, abandoning Picket Corral.

The rogue sheriff elected in 1864 in Ada County, set out to avenge the treatment of some of his Picket Corral compatriots by killing McConnel. Sheriff David Updyke, who will get his own blog post soon enough, was not successful and was later hanged by vigilantes.

Vigilante McConnell did alright for himself in life. He moved to Oregon where he was elected to the state senate. In the 1880s he moved back to Idaho where he opened a general store in Moscow with a partner. McConnell was a delegate to Idaho’s constitutional convention and briefly became a U.S. Senator from Idaho. In 1893 he became Idaho’s third governor, serving until 1897. That gave his daughter, Mary, a chance to meet and marry William E. Borah. McConnell passed away in 1925 at age 85.

Picket Corral became less of a robber’s roost over the year and more of a place to have a picnic.

[image error]

Published on November 19, 2021 04:00

November 18, 2021

The Idaho Connection to Paladin (Tap to read the story)

Okay, I’m going to back into this one like I’m unloading a spud truck.

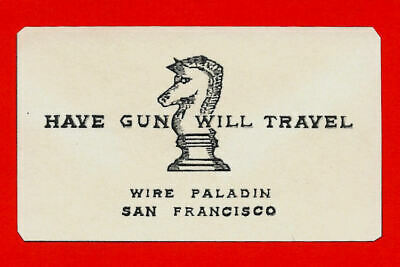

I got a hot tip about an Idaho author I wasn’t aware of. He was the guy who wrote the book, A Man Called Paladin , on which the television series, Have Gun Will Travel was based. That series, which starred Richard Boone as Paladin, ran from 1957 to 1963. I remember the chess piece knight and the business card, which appeared in almost every episode. Those were impressionable years for me, so I turned to gunfighting as an adult.

Well, no, that’s not true. Nor is the TV series based on the book. Grab the children out of the way, I’m still backing into this thing.

Have Gun Will Travel holds a couple of distinctions. It was one of only a handful of TV series that generated a radio series of the same name. The reverse—still in reverse here—was more often the case. Twenty-five of the episodes in the Western were written by Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek.

Just about to the loading dock, now.

A Man Called Paladin was written in 1964, the year after the TV series went off the air. It was written by a prolific author with solid Idaho roots, Frank Chester Robertson.

Okay, we’re parked now and ready to unload.

Frank Robertson was born in Moscow, Idaho in 1890, the year of Idaho’s statehood. At some point in his early childhood, Frank’s father became a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS), and moved the family to Chesterfield, Idaho, which was founded by Mormon settlers in 1881.

Young Frank helped support the family by herding sheep while his father was away on LDS missions. In 1914 Robertson proved up on a 320-acre homestead east of Chesterfield and began raising a family. They would eventually move to Utah where he would write most of the 150 novels he is famous for.

Robertson’s first book, though, was written at his Chesterfield home. Called The Foreman of the Forty Bar , it first appeared in a national magazine, and then as a syndicated feature in several newspapers before being published in 1924. His most popular book memorialized his family’s experience at Chesterfield. It was written in 1950 and called A Ram in the Thicket: The Story of a Roaming Homesteader Family on the Mormon Frontier .

Frank Robertson passed away in 1969. Chesterfield is on the National Register of Historic Places, getting that distinction in 1980. Sadly, Robertson’s childhood cabin was dismantled and removed in 1978.

I got a hot tip about an Idaho author I wasn’t aware of. He was the guy who wrote the book, A Man Called Paladin , on which the television series, Have Gun Will Travel was based. That series, which starred Richard Boone as Paladin, ran from 1957 to 1963. I remember the chess piece knight and the business card, which appeared in almost every episode. Those were impressionable years for me, so I turned to gunfighting as an adult.

Well, no, that’s not true. Nor is the TV series based on the book. Grab the children out of the way, I’m still backing into this thing.

Have Gun Will Travel holds a couple of distinctions. It was one of only a handful of TV series that generated a radio series of the same name. The reverse—still in reverse here—was more often the case. Twenty-five of the episodes in the Western were written by Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek.

Just about to the loading dock, now.

A Man Called Paladin was written in 1964, the year after the TV series went off the air. It was written by a prolific author with solid Idaho roots, Frank Chester Robertson.

Okay, we’re parked now and ready to unload.

Frank Robertson was born in Moscow, Idaho in 1890, the year of Idaho’s statehood. At some point in his early childhood, Frank’s father became a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS), and moved the family to Chesterfield, Idaho, which was founded by Mormon settlers in 1881.

Young Frank helped support the family by herding sheep while his father was away on LDS missions. In 1914 Robertson proved up on a 320-acre homestead east of Chesterfield and began raising a family. They would eventually move to Utah where he would write most of the 150 novels he is famous for.

Robertson’s first book, though, was written at his Chesterfield home. Called The Foreman of the Forty Bar , it first appeared in a national magazine, and then as a syndicated feature in several newspapers before being published in 1924. His most popular book memorialized his family’s experience at Chesterfield. It was written in 1950 and called A Ram in the Thicket: The Story of a Roaming Homesteader Family on the Mormon Frontier .

Frank Robertson passed away in 1969. Chesterfield is on the National Register of Historic Places, getting that distinction in 1980. Sadly, Robertson’s childhood cabin was dismantled and removed in 1978.

Published on November 18, 2021 04:00

November 17, 2021

On the National Register, in Two Counties (Tap to read the story)

Historic preservationists generally prefer that a building be preserved in its original location so that people better understand its context. Sometimes that isn’t possible, and the relocation of the building becomes part of its history. The Bishop’s House, now on a foundation near the old Idaho State Penitentiary, and Temple Beth Israel, located today near Morris Hill Cemetery are examples of important buildings that moved across town within the city of Boise.

There’s another building on the National Register of Historic Places in Ada County that didn’t stay put. In fact, it didn’t even stay in the county.

The MacMillan Chapel was constructed in 1899 on the northeast corner of what today is the intersection of West MacMillan and North Cloverdale roads. Idaho State Senator John MacMillan owned the land where the chapel would reside, donating two acres to the Meridian Methodist Episcopal Church South.

Built by community members, it is a small, one-story frame building with a steep-pitched roof. With little decorative trim not much about the carpenter gothic building conveys its purpose, except for the steeple and the white paint, yet at the same time it is an exemplary chapel of the kind that springs to mind when one hears the word.

There is a love story tied to the little chapel. A young couple was on a buggy ride in 1916 that would count as their first date. In a story told in a 1975 Idaho Statesman article, as they passed the chapel, Albert turned to his date, Hazel, and said, “I dare you to go to church here with me.”

Quoted in the article, Hazel said, “Since I was a church-going gal, I took the dare.” The couple became Albert and Hazel DeMeyer, married in 1921. What makes that story more interesting, is that the DeMeyers ended up owning the chapel long after it had been abandoned. They had rented the Jenkins Ranch where it was located for 15 years before buying the property in 1953.

The DeMeyers built their home on the original site of the chapel, moving the little church back away from the road and turning it to face Cloverdale. They used the chapel building mostly for storage. In 1984 it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Then, in 1993 the DeMeyers donated the chapel to a nonprofit group which moved it to a site near Star.

In 2004, Anne and Lewis McKellips purchased the building and moved it to 18121 Dean Lane in Canyon County. Today, completely refurbished, it is called the Stillwater Hollow Chapel and is the focus of the Stillwater Hollow events center, used frequently for weddings.

Originally listed as an Ada County property on the National Register of Historic Places, the MacMillan Chapel is now listed on the Register for Canyon County.

MacMillan Chapel, located at MacMillan and Cloverdale for many years, is now called Stillwater Hollow Chapel. The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places in both Canyon and Ada counties. Dan Smede photo.

MacMillan Chapel, located at MacMillan and Cloverdale for many years, is now called Stillwater Hollow Chapel. The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places in both Canyon and Ada counties. Dan Smede photo.

There’s another building on the National Register of Historic Places in Ada County that didn’t stay put. In fact, it didn’t even stay in the county.

The MacMillan Chapel was constructed in 1899 on the northeast corner of what today is the intersection of West MacMillan and North Cloverdale roads. Idaho State Senator John MacMillan owned the land where the chapel would reside, donating two acres to the Meridian Methodist Episcopal Church South.

Built by community members, it is a small, one-story frame building with a steep-pitched roof. With little decorative trim not much about the carpenter gothic building conveys its purpose, except for the steeple and the white paint, yet at the same time it is an exemplary chapel of the kind that springs to mind when one hears the word.

There is a love story tied to the little chapel. A young couple was on a buggy ride in 1916 that would count as their first date. In a story told in a 1975 Idaho Statesman article, as they passed the chapel, Albert turned to his date, Hazel, and said, “I dare you to go to church here with me.”

Quoted in the article, Hazel said, “Since I was a church-going gal, I took the dare.” The couple became Albert and Hazel DeMeyer, married in 1921. What makes that story more interesting, is that the DeMeyers ended up owning the chapel long after it had been abandoned. They had rented the Jenkins Ranch where it was located for 15 years before buying the property in 1953.

The DeMeyers built their home on the original site of the chapel, moving the little church back away from the road and turning it to face Cloverdale. They used the chapel building mostly for storage. In 1984 it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Then, in 1993 the DeMeyers donated the chapel to a nonprofit group which moved it to a site near Star.

In 2004, Anne and Lewis McKellips purchased the building and moved it to 18121 Dean Lane in Canyon County. Today, completely refurbished, it is called the Stillwater Hollow Chapel and is the focus of the Stillwater Hollow events center, used frequently for weddings.

Originally listed as an Ada County property on the National Register of Historic Places, the MacMillan Chapel is now listed on the Register for Canyon County.

MacMillan Chapel, located at MacMillan and Cloverdale for many years, is now called Stillwater Hollow Chapel. The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places in both Canyon and Ada counties. Dan Smede photo.

MacMillan Chapel, located at MacMillan and Cloverdale for many years, is now called Stillwater Hollow Chapel. The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places in both Canyon and Ada counties. Dan Smede photo.

Published on November 17, 2021 04:00

November 16, 2021

Mackay Shine (Tap to read the story)

If there’s one thing Mackay is known for today, it is that newcomers to Idaho can almost never pronounce it correctly. The name is pronounced "Mackie" with the accent on the first syllable.

It was apparently better known about 100 years ago as the place where good liquor originated.

Mick Hoover, the curator of the Lost River Museum, says that the moonshine operation in Mackay during Prohibition was on an industrial scale. Barrels of corn came into the Mackay Depot marked ‘corn for distilling,’ along with sugar and yeast. Everyone seemed to know what the ingredients were for but chose to not notice them. “Mackay Shine” was shipped by rail to Chicago and points east. It became known across the country for its quality, allegedly because the pure water in the area made for a good product. There is a small moonshine still on display in the museum.

But it wasn’t just corn liquor that Mackay was known for. On September 10, 1917, there was a report in the Blackfoot Idaho Republican, that a distillery was discovered in Custer County by the sheriff of Butte County, who was looking for the source of prune brandy that had been showing up in the area.

“For some time an intoxicating beverage has been used freely in the vicinity of the distillery,” the article read, “and the officials have been baffled in their efforts to located its source.” The distillery had been found only after “every possible ruse (had) been resorted to.”

The black market in moonshine came early to Idaho. The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified in January 1919, but Idaho had outlawed the sale of booze in 1917. The Eighteenth Amendment was eventually repealed by the Twenty-First Amendment in 1933, after it became clear Prohibition was causing more problems than it solved.

Governor Moses Alexander signing the bill that outlawed booze in Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Governor Moses Alexander signing the bill that outlawed booze in Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

It was apparently better known about 100 years ago as the place where good liquor originated.

Mick Hoover, the curator of the Lost River Museum, says that the moonshine operation in Mackay during Prohibition was on an industrial scale. Barrels of corn came into the Mackay Depot marked ‘corn for distilling,’ along with sugar and yeast. Everyone seemed to know what the ingredients were for but chose to not notice them. “Mackay Shine” was shipped by rail to Chicago and points east. It became known across the country for its quality, allegedly because the pure water in the area made for a good product. There is a small moonshine still on display in the museum.

But it wasn’t just corn liquor that Mackay was known for. On September 10, 1917, there was a report in the Blackfoot Idaho Republican, that a distillery was discovered in Custer County by the sheriff of Butte County, who was looking for the source of prune brandy that had been showing up in the area.

“For some time an intoxicating beverage has been used freely in the vicinity of the distillery,” the article read, “and the officials have been baffled in their efforts to located its source.” The distillery had been found only after “every possible ruse (had) been resorted to.”

The black market in moonshine came early to Idaho. The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified in January 1919, but Idaho had outlawed the sale of booze in 1917. The Eighteenth Amendment was eventually repealed by the Twenty-First Amendment in 1933, after it became clear Prohibition was causing more problems than it solved.

Governor Moses Alexander signing the bill that outlawed booze in Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Governor Moses Alexander signing the bill that outlawed booze in Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Published on November 16, 2021 04:00

November 15, 2021

How Freezeout Hill got its Name (Tap to read the story)

Today, when you travel north on State Highway 16 into Emmett, you glide down a gentle hill in the comfort of your car to arrive in the famous fruit-growing valley.

It was a little more difficult to descend into that valley in 1862. That was the year Tim Goodale first tried it. Goodale led some 338 wagons and 2,900 head of stock down the steep drop into the valley. He was the man who popularized the Goodale Cutoff, a northern spur of the Oregon Trail that left the main route near Fort Hall and rejoined it at the Powder River near present-day Baker City, Oregon.

The site got its name a couple of years later when a freighter and another wagon filled with valley residents tried the grade in the winter. The settlers rough-locked their wagon brakes in an attempt to skid it down the slopes. This method was sometimes called freezing the brakes.

Call it what you will, the wagon slid into a gulch and the settlers trudged back up the hill to spend the night with the freighter who had decided not to risk the descent. They spent a bitter night on the ridge, which froze the experience in their minds. They would later describe it as being “froze out of the valley.” That led to the naming of the place we know today as Freezeout Hill.

It was a little more difficult to descend into that valley in 1862. That was the year Tim Goodale first tried it. Goodale led some 338 wagons and 2,900 head of stock down the steep drop into the valley. He was the man who popularized the Goodale Cutoff, a northern spur of the Oregon Trail that left the main route near Fort Hall and rejoined it at the Powder River near present-day Baker City, Oregon.

The site got its name a couple of years later when a freighter and another wagon filled with valley residents tried the grade in the winter. The settlers rough-locked their wagon brakes in an attempt to skid it down the slopes. This method was sometimes called freezing the brakes.

Call it what you will, the wagon slid into a gulch and the settlers trudged back up the hill to spend the night with the freighter who had decided not to risk the descent. They spent a bitter night on the ridge, which froze the experience in their minds. They would later describe it as being “froze out of the valley.” That led to the naming of the place we know today as Freezeout Hill.

Published on November 15, 2021 04:00

November 14, 2021

Idaho's Normal Schools, Part 2 (Tap to read the story)

Yesterday I gave a little history of the Albion State Normal School in southern Idaho. In 1893 the Idaho State Legislature authorized two normal schools, one in Albion and the other in Lewiston. Funding for those schools was slow in coming. It became up to the towns where the schools would reside to get them going.

The City of Lewiston donated 10 acres in a city park as the site for the new normal school. The “park” was little more than a sandy, barren hill, soon to be known as Normal Hill.

Construction of the first campus building went on in fits and starts until 1895 when the Legislature issued bonds to pay for its completion. That assurance, and the sight of a building going up, encouraged the new president of the school, George Knepper, to get things going. He found temporary space in a downtown building to begin classes. Forty-six students were in that first class in January 1896. In the fall, classes would begin on campus.

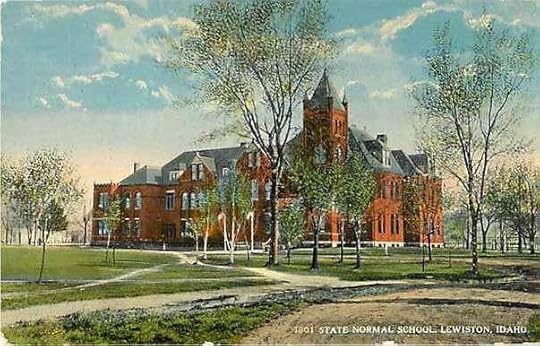

That first campus building (picture), which still stands, was later named James W. Reid Centennial Hall in honor of the man who lobbied successfully for creation of the school. Today it is the center for student services and holds administrative offices and classrooms.

The school expanded to offer 4-year degrees in 1943 and became the Northern Idaho College of Education in 1947.

As mentioned yesterday, the Idaho Legislature commissioned a study of Idaho’s higher education institutions in. 1946. That study resulted in the closure of both the Northern Idaho College of Education and Albion Normal School in 1951.

Albion never did reopen, but in 1955 the Lewiston campus got going again as the Lewis-Clark Normal School. It originally operated as a branch of Idaho State University, offering degrees for elementary school teachers. In 1963 the Legislature gave Lewis-Clark its autonomy as an independent undergraduate institution. Its role was expanded in 1965 to include practical and associate degrees in nursing. Then, in 1971 the Idaho Legislature changed the name to Lewis-Clark State College.

Today the college offers a variety of undergraduate degrees in liberal arts, sciences, business, technical programs, and education.

The City of Lewiston donated 10 acres in a city park as the site for the new normal school. The “park” was little more than a sandy, barren hill, soon to be known as Normal Hill.

Construction of the first campus building went on in fits and starts until 1895 when the Legislature issued bonds to pay for its completion. That assurance, and the sight of a building going up, encouraged the new president of the school, George Knepper, to get things going. He found temporary space in a downtown building to begin classes. Forty-six students were in that first class in January 1896. In the fall, classes would begin on campus.

That first campus building (picture), which still stands, was later named James W. Reid Centennial Hall in honor of the man who lobbied successfully for creation of the school. Today it is the center for student services and holds administrative offices and classrooms.

The school expanded to offer 4-year degrees in 1943 and became the Northern Idaho College of Education in 1947.

As mentioned yesterday, the Idaho Legislature commissioned a study of Idaho’s higher education institutions in. 1946. That study resulted in the closure of both the Northern Idaho College of Education and Albion Normal School in 1951.

Albion never did reopen, but in 1955 the Lewiston campus got going again as the Lewis-Clark Normal School. It originally operated as a branch of Idaho State University, offering degrees for elementary school teachers. In 1963 the Legislature gave Lewis-Clark its autonomy as an independent undergraduate institution. Its role was expanded in 1965 to include practical and associate degrees in nursing. Then, in 1971 the Idaho Legislature changed the name to Lewis-Clark State College.

Today the college offers a variety of undergraduate degrees in liberal arts, sciences, business, technical programs, and education.

Published on November 14, 2021 04:00

November 13, 2021

Idaho's Normal Schools, Part One (Tap to read the story)

When I was growing up, I heard a lot about the Albion Normal School because my mother went there. I’m sure I wasn’t the first to wonder, if this was the “normal” school, where did the students who weren’t normal go?

Normal schools in the U.S. were simply colleges that produced teachers. Idaho had two of them. In a way, it still has both, though the campus at Albion hasn’t been a place of higher education since 1951.

We’ll look at a little history of Albion, today. Tomorrow the subject will be the Lewiston Normal School. Both schools were authorized by the Idaho State Legislature in 1893.

Today, Albion is a small south-central Idaho town. But in 1893, it was a small south-central Idaho town. What? Some did scratch their heads when the site was picked. There was no railroad nearby and nothing particular that would lead one to believe a college would thrive there. It did have the advantage of being about a day’s travel away from most places in southern Idaho, and it had an influential senator who proposed the location.

The proposal nearly died at its inception. The bill creating the school called for funds to come from the sale of public lands granted by Congress for colleges devoted to the development of agriculture and the mechanical arts. The Idaho Attorney General wrote an opinion that such a funding method was unconstitutional. In his opinion only the interest from such funds could be used while the principle remained untouched. In his opinion, Attorney General Parsons wrote, “The intention of congress (was) to create an irreducible fund, one that will not only benefit present but also all future generations, is most manifest.” We call income from those lands the State Endowment Fund today.

Both normal schools were authorized, but with nearly no funding.

That didn’t stop the citizens of Albion. J.E. Miller donated land for the campus of the new normal school and the citizens got together to construct the first building with volunteer labor. In 1894 classes began with 23 students and two teachers.

At first the Albion Normal School offered only one year of instruction to its students. By 1934 it was a two-year school with 200 students.

But, it was still in Albion, that small south-central Idaho town. That didn’t make sense to a lot of people and the school endured efforts to close it in 1911 and 1917. Then, in 1946, the Idaho Legislature commissioned a study of the state’s institutions of higher learning. That study recommended the closure of Albion if it did not substantially increase its student enrollment within five years. Those years ticked by without an uptick, and the school was shuttered in 1951.

Its mission of educating teachers was transferred to Idaho State College, now Idaho State University in Pocatello.

During its time, more than 6,500 teachers got degrees there, including future U.S. Secretary of Education Terrill Bell. Oh, and my mom, my aunt, and my great aunt. Who do you know that went to Albion?

Normal schools in the U.S. were simply colleges that produced teachers. Idaho had two of them. In a way, it still has both, though the campus at Albion hasn’t been a place of higher education since 1951.

We’ll look at a little history of Albion, today. Tomorrow the subject will be the Lewiston Normal School. Both schools were authorized by the Idaho State Legislature in 1893.

Today, Albion is a small south-central Idaho town. But in 1893, it was a small south-central Idaho town. What? Some did scratch their heads when the site was picked. There was no railroad nearby and nothing particular that would lead one to believe a college would thrive there. It did have the advantage of being about a day’s travel away from most places in southern Idaho, and it had an influential senator who proposed the location.

The proposal nearly died at its inception. The bill creating the school called for funds to come from the sale of public lands granted by Congress for colleges devoted to the development of agriculture and the mechanical arts. The Idaho Attorney General wrote an opinion that such a funding method was unconstitutional. In his opinion only the interest from such funds could be used while the principle remained untouched. In his opinion, Attorney General Parsons wrote, “The intention of congress (was) to create an irreducible fund, one that will not only benefit present but also all future generations, is most manifest.” We call income from those lands the State Endowment Fund today.

Both normal schools were authorized, but with nearly no funding.

That didn’t stop the citizens of Albion. J.E. Miller donated land for the campus of the new normal school and the citizens got together to construct the first building with volunteer labor. In 1894 classes began with 23 students and two teachers.

At first the Albion Normal School offered only one year of instruction to its students. By 1934 it was a two-year school with 200 students.

But, it was still in Albion, that small south-central Idaho town. That didn’t make sense to a lot of people and the school endured efforts to close it in 1911 and 1917. Then, in 1946, the Idaho Legislature commissioned a study of the state’s institutions of higher learning. That study recommended the closure of Albion if it did not substantially increase its student enrollment within five years. Those years ticked by without an uptick, and the school was shuttered in 1951.

Its mission of educating teachers was transferred to Idaho State College, now Idaho State University in Pocatello.

During its time, more than 6,500 teachers got degrees there, including future U.S. Secretary of Education Terrill Bell. Oh, and my mom, my aunt, and my great aunt. Who do you know that went to Albion?

Published on November 13, 2021 04:00

November 11, 2021

The Boise Victory Center (Tap to read the story)

During World War II cities and towns across the country established Victory Centers. They were places temporarily put into service to raise money for the war effort through the sale of war bonds.

Boise’s Victory Center was a stage in front of city hall. Every week on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, organizers would present entertainment there starting when the noon whistle went off. The performances were meant to inspire downtown workers to buy bonds and, not incidentally, sign up for some branch of the military to serve their country.

The first mention of a Victory Center in The Idaho Statesman, on June 12, 1942, had a strong Idaho connection, but it wasn’t about Boise. It was about the Portland Victory Center, where Lana Turner had bestowed kisses on the top purchasers of war bonds. Turner, from Wallace, Idaho, was generous with her kisses and the people of Portland—likely the male people of Portland—were generous with their dollars. The crowd of some 30,000 purchased $379,000 worth of war bonds.

Inspired by Portland’s success, Boise merchants announced the first performance on the Victory Center stage in front of city hall at the end of June. The city band played, and every time someone bought a bond the emcee rang a bell.

The Statesman commended the Retail Merchants Bureau for the Victory Center, writing that, “If they take the trouble to arrange snappy, diversified programs, they will attract copious crowds to Victory Center, nee the City Hall vista.”

The newspaper’s praise continued: “Boise candidly apes Portland and Seattle in the Victory Center idea. Those two coast cities have mammoth Victory Center stages raised at the heart of the commercial districts and hold interesting programs daily, interspersed with effective bond buying ballyhoo. The programs attract thousands of people, utilize crowd emotion, fan the red-blooded Yankee spirit and sell thousands of dollars’ worth of victory bonds.”

The first week in July 1942, the Victory Center performance featured “a negro quartet from Camp Bonneville,” along with the Gowen Field orchestra. The U.S. treasury publicity chief made an appearance, declaring the Victory Center a vital part of the war bond effort. R.M. Logsdon, the state war bond committee secretary said, “It bares the patriotic spirit where the hurried noon-day crowds can pause to reflect on the urgency of financial support of the war effort.”

Performances on the stage included the dramatization of a prize-winning play by a KIDO troupe, Ivan Hopper’s orchestra, and a solo sung by Curt Williams. Rousing, patriotic speeches were not uncommon. One such, given by E.G. Harlan of the Boise Chamber of Commerce, included the line, “When a small boy saves his dimes and nickels until he can buy $5 worth of stamps, perhaps he is buying an airplane first aid kit that may save the life of his older brother in service.”

When the Dailey Brothers circus came to town, Mary, Rosie, and Nemo put on a show at the Victory Center. Mayor A.A. Walker posed with one of the pachyderms performers for a front-page picture.

That bond bell that rang up the purchases was probably scrap metal by the time it quit dinging on July 10. The City of Boise bought $50,000 in war bonds. A $1,000 war bond could be purchased for $750 and redeemed after the war for face value.

KIDO and The Statesman got together in August to sponsor a slogan contest. Those participating were to complete the phrase “Sponsor a Naval Recruit” with six catchy words of their own. The winner of the contest, from hundreds of entries, was Mrs. Dorothy Layne of Boise. Her slogan was “Sponsor a Naval Recruit—put more kicks in America’s boot.” That earned her a $25 war bond.

It wasn’t all about the money. At one Victory Center presentation 74 young men signed on with the navy. In subsequent days the Victory Center goal was to raise $1,000 each to pay for transportation and training of the men. They ended up raising $81,000.

[image error] Boise’s Victory Center was established to encourage the purchase of war bonds. Photo, United States. Dept. of the Treasury war bonds poster, 1942.

Boise’s Victory Center was a stage in front of city hall. Every week on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, organizers would present entertainment there starting when the noon whistle went off. The performances were meant to inspire downtown workers to buy bonds and, not incidentally, sign up for some branch of the military to serve their country.

The first mention of a Victory Center in The Idaho Statesman, on June 12, 1942, had a strong Idaho connection, but it wasn’t about Boise. It was about the Portland Victory Center, where Lana Turner had bestowed kisses on the top purchasers of war bonds. Turner, from Wallace, Idaho, was generous with her kisses and the people of Portland—likely the male people of Portland—were generous with their dollars. The crowd of some 30,000 purchased $379,000 worth of war bonds.

Inspired by Portland’s success, Boise merchants announced the first performance on the Victory Center stage in front of city hall at the end of June. The city band played, and every time someone bought a bond the emcee rang a bell.

The Statesman commended the Retail Merchants Bureau for the Victory Center, writing that, “If they take the trouble to arrange snappy, diversified programs, they will attract copious crowds to Victory Center, nee the City Hall vista.”

The newspaper’s praise continued: “Boise candidly apes Portland and Seattle in the Victory Center idea. Those two coast cities have mammoth Victory Center stages raised at the heart of the commercial districts and hold interesting programs daily, interspersed with effective bond buying ballyhoo. The programs attract thousands of people, utilize crowd emotion, fan the red-blooded Yankee spirit and sell thousands of dollars’ worth of victory bonds.”

The first week in July 1942, the Victory Center performance featured “a negro quartet from Camp Bonneville,” along with the Gowen Field orchestra. The U.S. treasury publicity chief made an appearance, declaring the Victory Center a vital part of the war bond effort. R.M. Logsdon, the state war bond committee secretary said, “It bares the patriotic spirit where the hurried noon-day crowds can pause to reflect on the urgency of financial support of the war effort.”

Performances on the stage included the dramatization of a prize-winning play by a KIDO troupe, Ivan Hopper’s orchestra, and a solo sung by Curt Williams. Rousing, patriotic speeches were not uncommon. One such, given by E.G. Harlan of the Boise Chamber of Commerce, included the line, “When a small boy saves his dimes and nickels until he can buy $5 worth of stamps, perhaps he is buying an airplane first aid kit that may save the life of his older brother in service.”

When the Dailey Brothers circus came to town, Mary, Rosie, and Nemo put on a show at the Victory Center. Mayor A.A. Walker posed with one of the pachyderms performers for a front-page picture.

That bond bell that rang up the purchases was probably scrap metal by the time it quit dinging on July 10. The City of Boise bought $50,000 in war bonds. A $1,000 war bond could be purchased for $750 and redeemed after the war for face value.

KIDO and The Statesman got together in August to sponsor a slogan contest. Those participating were to complete the phrase “Sponsor a Naval Recruit” with six catchy words of their own. The winner of the contest, from hundreds of entries, was Mrs. Dorothy Layne of Boise. Her slogan was “Sponsor a Naval Recruit—put more kicks in America’s boot.” That earned her a $25 war bond.

It wasn’t all about the money. At one Victory Center presentation 74 young men signed on with the navy. In subsequent days the Victory Center goal was to raise $1,000 each to pay for transportation and training of the men. They ended up raising $81,000.

[image error] Boise’s Victory Center was established to encourage the purchase of war bonds. Photo, United States. Dept. of the Treasury war bonds poster, 1942.

Published on November 11, 2021 04:00

November 9, 2021

Slicing Through the Fairgrounds (Tap to Read)

An advisory committee formed in 2020 to consider moving the Western Idaho Fairgrounds from its location in Garden City. This isn’t a new idea. A similar group popped up in 1963 when it became clear that the Western Idaho Fairgrounds would need to find a new home. Spoiler alert: The one they found was in Garden City at its present location.

The fair had operated at its Fairview Avenue location since 1916. In case you ever wondered where Fairview Avenue got its name, you need wonder no more. The fairgrounds lay between Fairview Avenue on the north and Irving Street on the south. Orchard Street was the eastern boundary and Curtis Road bordered the fairgrounds on the west.

If this all seems impossible because of that multi-lane interstate highway spur running through the middle of it, you’ve hit on the reason for the move. The Idaho Transportation Department carved out a lot of dirt diagonally through the fairgrounds property, dropping the elevation of the highway well below grade (see graphic below).

Although moving the fairgrounds was an obvious need in 1963, the fair didn’t open at its current Garden City site until 1967. The move was delayed a bit because the savvy City of Boise annexed the old fairgrounds property in 1966, certain that values would go up and services would be needed. Overlaying city zoning on the property ruffled the feathers of some potential developers, but the annexation went through.

The fair became The Western Idaho Fair along with the move in 1967. Previously it had billed itself as The Western Idaho State Fair, though it had no affiliation with the state. The new site was 235 acres, compared with the 45-acre site along Fairview. That gave the county room to expand with parking for 6,000 cars. The Exposition Building made its debut in 1967, allowing for two acres of indoor exhibits.

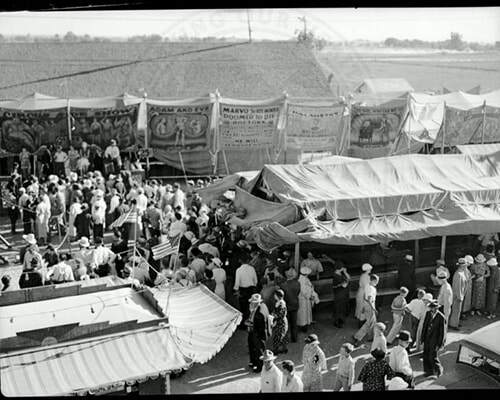

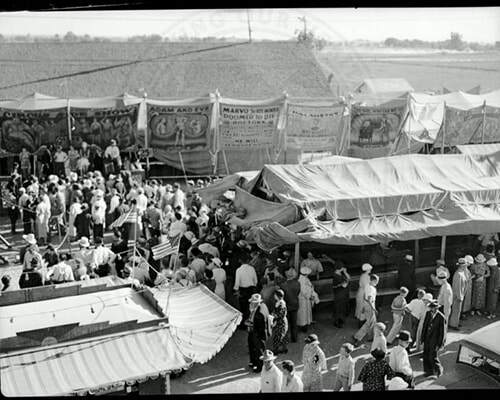

The new fairgrounds generated many millions in economic activity and continues to do so today. It will likely be an economic engine for years into to the future, wherever it is. A shot of the Western Idaho Fair from 1934. Note the bare ground at the top of the picture, probably looking west. The perimeter signs advertise Adam and Eve, Marvo the Wonder Boy Doomed to Die, palmistry, and the Girl Who Can Not Die. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A shot of the Western Idaho Fair from 1934. Note the bare ground at the top of the picture, probably looking west. The perimeter signs advertise Adam and Eve, Marvo the Wonder Boy Doomed to Die, palmistry, and the Girl Who Can Not Die. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

The fair had operated at its Fairview Avenue location since 1916. In case you ever wondered where Fairview Avenue got its name, you need wonder no more. The fairgrounds lay between Fairview Avenue on the north and Irving Street on the south. Orchard Street was the eastern boundary and Curtis Road bordered the fairgrounds on the west.

If this all seems impossible because of that multi-lane interstate highway spur running through the middle of it, you’ve hit on the reason for the move. The Idaho Transportation Department carved out a lot of dirt diagonally through the fairgrounds property, dropping the elevation of the highway well below grade (see graphic below).

Although moving the fairgrounds was an obvious need in 1963, the fair didn’t open at its current Garden City site until 1967. The move was delayed a bit because the savvy City of Boise annexed the old fairgrounds property in 1966, certain that values would go up and services would be needed. Overlaying city zoning on the property ruffled the feathers of some potential developers, but the annexation went through.

The fair became The Western Idaho Fair along with the move in 1967. Previously it had billed itself as The Western Idaho State Fair, though it had no affiliation with the state. The new site was 235 acres, compared with the 45-acre site along Fairview. That gave the county room to expand with parking for 6,000 cars. The Exposition Building made its debut in 1967, allowing for two acres of indoor exhibits.

The new fairgrounds generated many millions in economic activity and continues to do so today. It will likely be an economic engine for years into to the future, wherever it is.

A shot of the Western Idaho Fair from 1934. Note the bare ground at the top of the picture, probably looking west. The perimeter signs advertise Adam and Eve, Marvo the Wonder Boy Doomed to Die, palmistry, and the Girl Who Can Not Die. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A shot of the Western Idaho Fair from 1934. Note the bare ground at the top of the picture, probably looking west. The perimeter signs advertise Adam and Eve, Marvo the Wonder Boy Doomed to Die, palmistry, and the Girl Who Can Not Die. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on November 09, 2021 05:02

November 8, 2021

The Idanha and that other Idanha (Tap to read the story)

Today you’d be hard pressed to find a residential lot in Boise for $125,000. In 1900 that amount built Boise’s most expensive building. The Idanha Hotel, which opened for business on January 3, 1901. It boasted 140 rooms on six floors with three grand turrets on the north, east, and west corners at 10th and Main. It was the tallest structure in the state and housed the state’s first elevator.

The building is so iconic in Boise that it is a surprise to many to learn that It wasn’t Idaho’s first Idanha. The first one was built in 1887 in Soda Springs. That Idanha was a luxury hotel, with electric lights and natural gas heating. The Tri-Weekly Statesman quoted a gentleman who had seen the Soda Springs hotel as saying “the structure was not only one of the most complete in the West, but for its size one of the finest in the world.”

The two hotels were related only by name, and there is no solid evidence that the one in Boise was named after the Soda Springs Idanha. Developers likely knew about the first hotel, which had a good reputation at the time, so, why not borrow the name? The first Idanha had borrowed its name, after all. The moniker first appeared on the labels of Idanha Mineral Water, bottled in Soda Springs and sold all over the United States. But, let’s leave the Soda Springs hotel, which burned down in 1921, and get back to Boise’s grand hotel.

As the preferred place to stay in town for decades, the Idanha saw a lot of history. Walter “Big Train” Johnson, years before his induction into baseball’s hall of fame, practiced pitches in the hallway of the Idanha, shattering an inconveniently placed chamber pot with one low pitch.

Movie star Ethel Barrymore stayed there while attending the high-profile Haywood trial. “Big Bill” Haywood, a leader of the International Workers of the World was on trial for hiring Harry Orchard to assassinate Frank Steunenberg, a former Idaho governor who had clashed with the union. It was Clarence Darrow for the defense.

The Idanha came close to being the site of the assassination, until Harry Orchard had second thoughts about the bomb he had placed under Steunenberg’s bed. He disconnected the device because he feared it might injure or kill a chambermaid. Orchard planted another bomb at the gate of the former governor’s home in Caldwell to complete the job.

Famous folks who stayed at the Idanha included William Jennings Bryan, Sally Rand, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Polly Bemis. The legendary little Chinese woman who lived in the Salmon River country got her first elevator ride there.

And, since there’s always a remote chance someone may consider me famous one day, I must mention that I got to stay in a second-floor turret room courtesy of the federal government the night before I was inducted into the Marine Corps. It was easily the best part of that experience.

The Idanha is no longer a hotel. In recent years it was converted into an apartment building with 80 small apartments ranging in size from 380 to 786 square feet. That historic elevator has been giving tenants and management grief in recent years, becoming increasing unreliable.

From the outside the Idanha looks much the same as the day it opened. Though Vardis Fisher wrote in his 1936 guide to Boise, published only recently, “nobody finds it beautiful today,” that opinion about the Idanha is likely a minority one in 2020.

[image error] The Idanha in 1979. Photo by Leo J. "Scoop" Leeburn, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection. The Soda Springs Idanha was built in 1887. It burned in 1921.

The Soda Springs Idanha was built in 1887. It burned in 1921.

The building is so iconic in Boise that it is a surprise to many to learn that It wasn’t Idaho’s first Idanha. The first one was built in 1887 in Soda Springs. That Idanha was a luxury hotel, with electric lights and natural gas heating. The Tri-Weekly Statesman quoted a gentleman who had seen the Soda Springs hotel as saying “the structure was not only one of the most complete in the West, but for its size one of the finest in the world.”

The two hotels were related only by name, and there is no solid evidence that the one in Boise was named after the Soda Springs Idanha. Developers likely knew about the first hotel, which had a good reputation at the time, so, why not borrow the name? The first Idanha had borrowed its name, after all. The moniker first appeared on the labels of Idanha Mineral Water, bottled in Soda Springs and sold all over the United States. But, let’s leave the Soda Springs hotel, which burned down in 1921, and get back to Boise’s grand hotel.

As the preferred place to stay in town for decades, the Idanha saw a lot of history. Walter “Big Train” Johnson, years before his induction into baseball’s hall of fame, practiced pitches in the hallway of the Idanha, shattering an inconveniently placed chamber pot with one low pitch.

Movie star Ethel Barrymore stayed there while attending the high-profile Haywood trial. “Big Bill” Haywood, a leader of the International Workers of the World was on trial for hiring Harry Orchard to assassinate Frank Steunenberg, a former Idaho governor who had clashed with the union. It was Clarence Darrow for the defense.

The Idanha came close to being the site of the assassination, until Harry Orchard had second thoughts about the bomb he had placed under Steunenberg’s bed. He disconnected the device because he feared it might injure or kill a chambermaid. Orchard planted another bomb at the gate of the former governor’s home in Caldwell to complete the job.

Famous folks who stayed at the Idanha included William Jennings Bryan, Sally Rand, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Polly Bemis. The legendary little Chinese woman who lived in the Salmon River country got her first elevator ride there.

And, since there’s always a remote chance someone may consider me famous one day, I must mention that I got to stay in a second-floor turret room courtesy of the federal government the night before I was inducted into the Marine Corps. It was easily the best part of that experience.

The Idanha is no longer a hotel. In recent years it was converted into an apartment building with 80 small apartments ranging in size from 380 to 786 square feet. That historic elevator has been giving tenants and management grief in recent years, becoming increasing unreliable.

From the outside the Idanha looks much the same as the day it opened. Though Vardis Fisher wrote in his 1936 guide to Boise, published only recently, “nobody finds it beautiful today,” that opinion about the Idanha is likely a minority one in 2020.

[image error] The Idanha in 1979. Photo by Leo J. "Scoop" Leeburn, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

The Soda Springs Idanha was built in 1887. It burned in 1921.

The Soda Springs Idanha was built in 1887. It burned in 1921.

Published on November 08, 2021 04:00