Rick Just's Blog, page 113

September 26, 2021

The Shelley Farm Camp

Most of us know something about Japanese internment camps. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor hysteria ran high, pressuring President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. It forced the removal and incarceration of more than 120,000 U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry (Nikkei) in ten prison camps across the West, based mostly on their ethnicity. Some 13,000 ended up at what is sometimes called the Hunt Camp at Minidoka, Idaho.

Less well known is a program that brought many of those incarcerated Americans to work in the beet fields of Bingham County.

Sugar is a staple product at any time. During World War II it was a staple that was in short supply. We think of sugar as a basic baking ingredient and something to put on our cereal. But in wartime it takes on new importance. It can be converted to industrial alcohol to be used in the making of synthetic rubber and munitions. It was so important to the latter, that the United States Beet Sugar Association stated that a fifth of an acre of sugar beets went up in smoke every time a sixteen-inch gun was fired.

The federal government encouraged farmers to plant more sugar beets, since the supply of cane sugar imported from the Philippines was cut off during the war. But planting beets isn’t enough. Farmers needed workers to cultivate and harvest their crops. Many men who might have once hoed the rows were now working in defense industries or fighting in the war.

Volunteers stepped up to thin beets. Business owners closed shops early, members of various clubs stepped up, and Idaho Fish and Game employees spent some time in the fields. A newspaper editor, a college president, and countless clerks volunteered. But more help was needed.

The Japanese internment camps became a source of labor for the wartime sugar harvests. Laborers and their families moved into the beet fields in nine western states. The Farm Labor Camp in Shelley was the center of the activity in Bingham County.

The program lasted about three years, employing several hundred workers in Bingham County from the internment camp at Minidoka.

A young boy made a pet of a mourning dove at the Shelley Farm Camp. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A young boy made a pet of a mourning dove at the Shelley Farm Camp. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

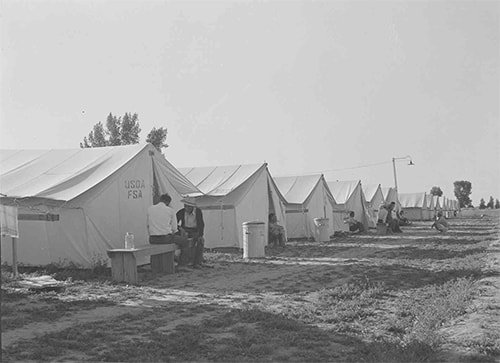

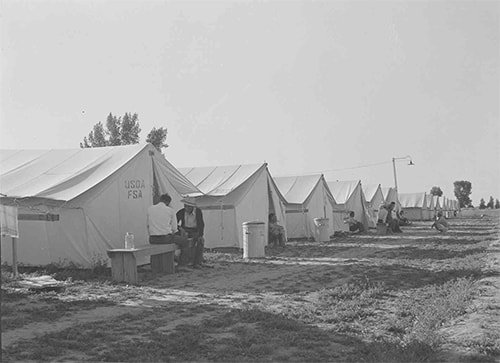

Internees from the Minidoka Camp were housed temporarily in tents at the Shelley Farm Camp so that they could help with the sugar beet crop in the county. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Internees from the Minidoka Camp were housed temporarily in tents at the Shelley Farm Camp so that they could help with the sugar beet crop in the county. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Less well known is a program that brought many of those incarcerated Americans to work in the beet fields of Bingham County.

Sugar is a staple product at any time. During World War II it was a staple that was in short supply. We think of sugar as a basic baking ingredient and something to put on our cereal. But in wartime it takes on new importance. It can be converted to industrial alcohol to be used in the making of synthetic rubber and munitions. It was so important to the latter, that the United States Beet Sugar Association stated that a fifth of an acre of sugar beets went up in smoke every time a sixteen-inch gun was fired.

The federal government encouraged farmers to plant more sugar beets, since the supply of cane sugar imported from the Philippines was cut off during the war. But planting beets isn’t enough. Farmers needed workers to cultivate and harvest their crops. Many men who might have once hoed the rows were now working in defense industries or fighting in the war.

Volunteers stepped up to thin beets. Business owners closed shops early, members of various clubs stepped up, and Idaho Fish and Game employees spent some time in the fields. A newspaper editor, a college president, and countless clerks volunteered. But more help was needed.

The Japanese internment camps became a source of labor for the wartime sugar harvests. Laborers and their families moved into the beet fields in nine western states. The Farm Labor Camp in Shelley was the center of the activity in Bingham County.

The program lasted about three years, employing several hundred workers in Bingham County from the internment camp at Minidoka.

A young boy made a pet of a mourning dove at the Shelley Farm Camp. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A young boy made a pet of a mourning dove at the Shelley Farm Camp. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress. Internees from the Minidoka Camp were housed temporarily in tents at the Shelley Farm Camp so that they could help with the sugar beet crop in the county. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Internees from the Minidoka Camp were housed temporarily in tents at the Shelley Farm Camp so that they could help with the sugar beet crop in the county. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Published on September 26, 2021 04:00

September 25, 2021

Hugh Whitney Got Away, Part III

This is part three of a three-part story about Hugh Whitney. previously I told you about his robbing a saloon in Monida, Montana, then hopping on a train into Idaho. He was briefly arrested on board the train by a deputy who had gotten on in Spencer, Idaho for that purpose. When the cuffs came out he shot the deputy, then the train conductor. The latter later died. Yesterday we ended with Whitney shooting three fingers off the hand of a deputy who tried to stop him when he crossed the Menan Bridge.

After that, wanted posters went up across a three-state area offering a $500 reward. This was before anyone knew much about Whitney, other than he was a cowhand and a killer, probably from Cokeville, Wyoming. Then officials found out he had grown up on a ranch in Adams County, Idaho, about three miles south of Council, where his parents still lived. Idaho Governor James Hawley added $500 to the reward money, and Oregon Shortline officials put in another $1,000.

It was about that time Whitney became a ghost and a boogeyman. He was nowhere and everywhere, terrorizing gentle folks with his very existence.

Sightings came in from Idaho, Montana, Utah, and Wyoming. On August 13, the Idaho Statesman reported that Whitney had been arrested in Rexburg. Except it turned out not to be Whitney, but a young man from Boise who had wandered away from his surveying crew and gotten lost.

Then, on September 10, Whitney was positively seen, along with his brother, Charles, holding up a bank in Cokeville, Wyoming. The brothers had worked as sheepherders in the area but had been fired because Hugh Whitney had a habit of herding sheep by firing his pistol at them. The Whitneys stole about $500, mostly from 14 bank customers since the safe was on a timer and couldn’t be opened for them. When they finished with their collection of offerings, they mounted up and, shooting as they went, galloped out of town. Hugh Whitney got away.

Large posses from Cokeville and Afton, Wyoming, as well as Montepelier, Idaho pursued the pair. The brothers were spotted crossing a toll bridge at Chubb Springs not far from the Blackfoot Reservoir. Posses from Idaho Falls and Rexburg set out to intercept them.

On September 15, the Montpelier paper carried a story of a sighting of the Whitneys there. In the same issue the paper took umbrage over a dispatch from Cokeville that went to the Salt Lake Herald-Republican that claimed the pair had been hiding out in Montpelier for weeks with the aid of local residents.

On September 18, reports hit the papers that posses were closing in on Hugh Whitney near the Idaho Wyoming border.

On September 22, the Whitneys were surely the two masked men who robbed a resort at Hailey and shot a musician dead.

The ghostly Whitneys then made a series of appearances, starting with their capture in Montpelier by two homesteaders. Then Hugh was taken into custody in a Pocatello barber shop. Then he was captured in Mackay. Except, no, he wasn’t. That rounded out 1912.

In July, 1913, Whitney showed up in The Pocatello Tribune if not in Rigby, where he might have robbed a bank. At this point, you would be well advised to get a refreshment of your choice and settle in for the reading of the next sentence, which I will quote verbatim. “That it was Hugh Whitney, notorious Wyoming and Idaho desperado, who held up the bank at Rigby Tuesday afternoon, escaping with $3500; that he eluded a sheriff’s posse by swinging around by Willow Creek and back to the main line of the Short Line at Firth; that he boarded train No. 2, southbound, early yesterday morning, alighting at Pocatello and taking eastbound train No. 5, bound for his Wyoming haunts; that a saddle horse left near the station at Firth with a sack of silver tied to the horn belonged to the desperado; that he is by this time safe among his friends somewhere north of Cokeville, and that it is useless to search further for him, is the belief of local officers of the law, who yesterday afternoon received word from Firth that a saddle horse was found hitched there yesterday morning, with a sack of silver tied to the saddlehorn.”

I hope you took a breath.

In September of 1913, Salt Lake officials captured Whitney. No, they didn’t. A few days later he was sighted all over town in Pocatello. No, he wasn’t.

On September 27, The Idaho Statesman quipped that “Any town that wants to be sure to stay on the map should at once capture Bandit Hugh Whitney.”

By March 1914, Whitney Fever had yet to subside. The Statesman reported that a “desperate looking character” was trailed by reporters hoping for a scoop, only to find it was a local man who had just returned from a wool-buying trip in Oregon.

In July of 1914, three years after the murder of Conductor Kidd, they had Whitney at last. He was involved in the robbery of a train near Pendleton, Oregon. Two outlaws got away, but the “body of the dead desperado (was) positively identified as that of Hugh Whitney.”

Alas, no it wasn’t. The body had been identified because there was a watch that purportedly belonged to Whitney among the man’s belongings.

In 1915, speculation was high that the man holding a prominent Bingham County rancher for ransom was Hugh Whitney. He wasn’t.

The fever cooled for a while, but in 1925 Reno, Nevada police thought they had Hugh Whitney in custody. Say it with me, “they didn’t.”

In 1926, Hugh Whitney was killed during a bank robbery in Roseville, California. Not.

Hugh Whitney, according to The Post Register of March 10, 1932, was living somewhere in the area of Idaho Falls. Montana officers had tipped them off that Whitney was living incognito so near to the many places he had frequented (or not) some 21 years earlier. The excitement soon faded away.

Little was heard of Hugh Whitney, save for those “25 years ago” columns until 1951. That’s when a rancher named Frank S. Taylor sat down for a little talk with the governor of Montana, whom he knew. “Frank” had a confession to make.

Frank Taylor was actually Charlie Whitney, brother of the notorious Hugh and sometimes partner in crime. He was coming forward to confess, because Hugh Whitney had died. Charlie wanted to come clean.

It seems the brothers had fled the West after the Cokeville bank robbery. They lived in Wisconsin and Minnesota for about a year, then changed their names and moved to Montana. They worked as ranch hands near Glasgow in northeastern Montana.

The brothers both enlisted in the army during WWI and fought in France. They returned to Montana after the war, but Hugh went to Saskatchewan in 1935, where he prospered as a rancher. On his deathbed Hugh had confessed to his crimes and absolved Charlie of participation in any of them, except for the Cokeville bank robbery.

Montana’s governor sent Wyoming’s governor a letter recommending clemency for Charlie’s role in that hold up.

Charlie Whitney-cum-Frank Taylor traveled to Cheyenne to face whatever music was playing there. He spent ten days in jail while a judge, named Robert Christmas, contemplated his fate. The Christmas present was that the judge saw no point in punishing the 63-year-old-man for robbing a bank that no longer existed. He pardoned Charlie, who returned to ranching in Montana, where he passed away in 1968. But Hugh? Hugh Whitney got away.

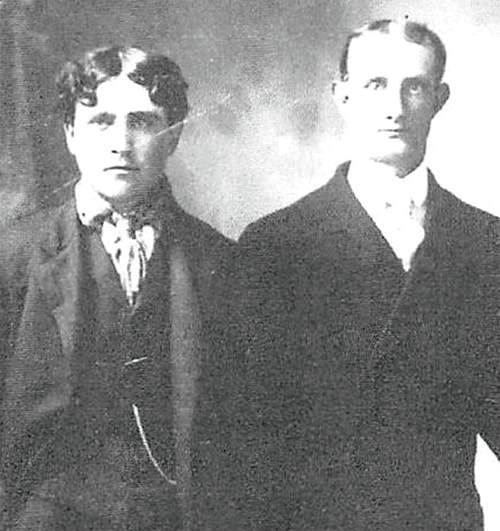

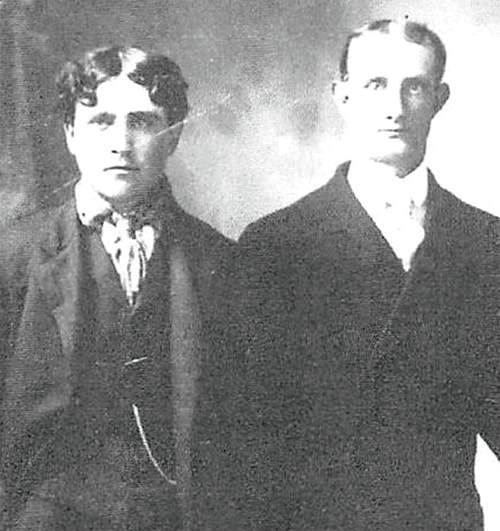

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

After that, wanted posters went up across a three-state area offering a $500 reward. This was before anyone knew much about Whitney, other than he was a cowhand and a killer, probably from Cokeville, Wyoming. Then officials found out he had grown up on a ranch in Adams County, Idaho, about three miles south of Council, where his parents still lived. Idaho Governor James Hawley added $500 to the reward money, and Oregon Shortline officials put in another $1,000.

It was about that time Whitney became a ghost and a boogeyman. He was nowhere and everywhere, terrorizing gentle folks with his very existence.

Sightings came in from Idaho, Montana, Utah, and Wyoming. On August 13, the Idaho Statesman reported that Whitney had been arrested in Rexburg. Except it turned out not to be Whitney, but a young man from Boise who had wandered away from his surveying crew and gotten lost.

Then, on September 10, Whitney was positively seen, along with his brother, Charles, holding up a bank in Cokeville, Wyoming. The brothers had worked as sheepherders in the area but had been fired because Hugh Whitney had a habit of herding sheep by firing his pistol at them. The Whitneys stole about $500, mostly from 14 bank customers since the safe was on a timer and couldn’t be opened for them. When they finished with their collection of offerings, they mounted up and, shooting as they went, galloped out of town. Hugh Whitney got away.

Large posses from Cokeville and Afton, Wyoming, as well as Montepelier, Idaho pursued the pair. The brothers were spotted crossing a toll bridge at Chubb Springs not far from the Blackfoot Reservoir. Posses from Idaho Falls and Rexburg set out to intercept them.

On September 15, the Montpelier paper carried a story of a sighting of the Whitneys there. In the same issue the paper took umbrage over a dispatch from Cokeville that went to the Salt Lake Herald-Republican that claimed the pair had been hiding out in Montpelier for weeks with the aid of local residents.

On September 18, reports hit the papers that posses were closing in on Hugh Whitney near the Idaho Wyoming border.

On September 22, the Whitneys were surely the two masked men who robbed a resort at Hailey and shot a musician dead.

The ghostly Whitneys then made a series of appearances, starting with their capture in Montpelier by two homesteaders. Then Hugh was taken into custody in a Pocatello barber shop. Then he was captured in Mackay. Except, no, he wasn’t. That rounded out 1912.

In July, 1913, Whitney showed up in The Pocatello Tribune if not in Rigby, where he might have robbed a bank. At this point, you would be well advised to get a refreshment of your choice and settle in for the reading of the next sentence, which I will quote verbatim. “That it was Hugh Whitney, notorious Wyoming and Idaho desperado, who held up the bank at Rigby Tuesday afternoon, escaping with $3500; that he eluded a sheriff’s posse by swinging around by Willow Creek and back to the main line of the Short Line at Firth; that he boarded train No. 2, southbound, early yesterday morning, alighting at Pocatello and taking eastbound train No. 5, bound for his Wyoming haunts; that a saddle horse left near the station at Firth with a sack of silver tied to the horn belonged to the desperado; that he is by this time safe among his friends somewhere north of Cokeville, and that it is useless to search further for him, is the belief of local officers of the law, who yesterday afternoon received word from Firth that a saddle horse was found hitched there yesterday morning, with a sack of silver tied to the saddlehorn.”

I hope you took a breath.

In September of 1913, Salt Lake officials captured Whitney. No, they didn’t. A few days later he was sighted all over town in Pocatello. No, he wasn’t.

On September 27, The Idaho Statesman quipped that “Any town that wants to be sure to stay on the map should at once capture Bandit Hugh Whitney.”

By March 1914, Whitney Fever had yet to subside. The Statesman reported that a “desperate looking character” was trailed by reporters hoping for a scoop, only to find it was a local man who had just returned from a wool-buying trip in Oregon.

In July of 1914, three years after the murder of Conductor Kidd, they had Whitney at last. He was involved in the robbery of a train near Pendleton, Oregon. Two outlaws got away, but the “body of the dead desperado (was) positively identified as that of Hugh Whitney.”

Alas, no it wasn’t. The body had been identified because there was a watch that purportedly belonged to Whitney among the man’s belongings.

In 1915, speculation was high that the man holding a prominent Bingham County rancher for ransom was Hugh Whitney. He wasn’t.

The fever cooled for a while, but in 1925 Reno, Nevada police thought they had Hugh Whitney in custody. Say it with me, “they didn’t.”

In 1926, Hugh Whitney was killed during a bank robbery in Roseville, California. Not.

Hugh Whitney, according to The Post Register of March 10, 1932, was living somewhere in the area of Idaho Falls. Montana officers had tipped them off that Whitney was living incognito so near to the many places he had frequented (or not) some 21 years earlier. The excitement soon faded away.

Little was heard of Hugh Whitney, save for those “25 years ago” columns until 1951. That’s when a rancher named Frank S. Taylor sat down for a little talk with the governor of Montana, whom he knew. “Frank” had a confession to make.

Frank Taylor was actually Charlie Whitney, brother of the notorious Hugh and sometimes partner in crime. He was coming forward to confess, because Hugh Whitney had died. Charlie wanted to come clean.

It seems the brothers had fled the West after the Cokeville bank robbery. They lived in Wisconsin and Minnesota for about a year, then changed their names and moved to Montana. They worked as ranch hands near Glasgow in northeastern Montana.

The brothers both enlisted in the army during WWI and fought in France. They returned to Montana after the war, but Hugh went to Saskatchewan in 1935, where he prospered as a rancher. On his deathbed Hugh had confessed to his crimes and absolved Charlie of participation in any of them, except for the Cokeville bank robbery.

Montana’s governor sent Wyoming’s governor a letter recommending clemency for Charlie’s role in that hold up.

Charlie Whitney-cum-Frank Taylor traveled to Cheyenne to face whatever music was playing there. He spent ten days in jail while a judge, named Robert Christmas, contemplated his fate. The Christmas present was that the judge saw no point in punishing the 63-year-old-man for robbing a bank that no longer existed. He pardoned Charlie, who returned to ranching in Montana, where he passed away in 1968. But Hugh? Hugh Whitney got away.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Published on September 25, 2021 04:00

September 24, 2021

Hugh Whitney Got Away, Part II

This is part two of a three-part story about Hugh Whitney. Yesterday I told you about his robbing a saloon in Monida, Montana, then hopping on a train into Idaho. He was briefly arrested on board the train by a deputy who had gotten on in Spencer, Idaho for that purpose. When the cuffs came out he shot the deputy, then the train conductor. The latter later died.

The story was a sensation in Southeastern Idaho. Every paper carried updates on the search for Whitney. And what a search it was. Hundreds of men joined the effort within hours. Two groups got close to the escaped men, following them across the desert. Both times the pursuers backed away because of the hammering gunfire.

Somewhere near Hamer, the men split up. Whitney stole a horse at the McGill Ranch, shooting young Edgar McGill in the skirmish. Early reports were that Whitney had killed the youth, but he survived.

Authorities brought in bloodhounds from the Montana State Prison at Deer Lodge. They joined the lawmen and volunteers in the search but turned up only a shoplifter who was hiding out on the desert. A band of Blackfeet Indians joined the search, along with a hundred men from the Rigby area who were scouring the desert, mostly on horseback and with the aid of a couple of automobiles.

The Idaho Statesman reported that Whitney was likely somewhere between Blackfoot and Idaho Falls. The article said, “Until he shall faint from fatigue or fall before the guns of his hunters there will be no rest for isolated ranch families or the lonely sheepherders. New crimes are expected hourly as long as the desperate man is at large.”

Searchers thought that Whitney might try to cross the Menan Bridge to get back on the south side of the Snake where the going would be easier. They stationed Deputy Reuben Scott on the bridge with his rifle at the ready. Sure enough, here came Whitney riding his stolen horse across the planks at a slow clop.

“Halt and get off that horse,” Deputy Scott called out. Whitney replied, “Lookout, I’m a-coming’” and spurred his steed to a gallop. He took a running aim at the lawman and fired once. Scott’s rifle dropped to the ground, as did three of his fingers. Hugh Whitney got away.

Check back tomorrow for the conclusion of this three-part story.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

The story was a sensation in Southeastern Idaho. Every paper carried updates on the search for Whitney. And what a search it was. Hundreds of men joined the effort within hours. Two groups got close to the escaped men, following them across the desert. Both times the pursuers backed away because of the hammering gunfire.

Somewhere near Hamer, the men split up. Whitney stole a horse at the McGill Ranch, shooting young Edgar McGill in the skirmish. Early reports were that Whitney had killed the youth, but he survived.

Authorities brought in bloodhounds from the Montana State Prison at Deer Lodge. They joined the lawmen and volunteers in the search but turned up only a shoplifter who was hiding out on the desert. A band of Blackfeet Indians joined the search, along with a hundred men from the Rigby area who were scouring the desert, mostly on horseback and with the aid of a couple of automobiles.

The Idaho Statesman reported that Whitney was likely somewhere between Blackfoot and Idaho Falls. The article said, “Until he shall faint from fatigue or fall before the guns of his hunters there will be no rest for isolated ranch families or the lonely sheepherders. New crimes are expected hourly as long as the desperate man is at large.”

Searchers thought that Whitney might try to cross the Menan Bridge to get back on the south side of the Snake where the going would be easier. They stationed Deputy Reuben Scott on the bridge with his rifle at the ready. Sure enough, here came Whitney riding his stolen horse across the planks at a slow clop.

“Halt and get off that horse,” Deputy Scott called out. Whitney replied, “Lookout, I’m a-coming’” and spurred his steed to a gallop. He took a running aim at the lawman and fired once. Scott’s rifle dropped to the ground, as did three of his fingers. Hugh Whitney got away.

Check back tomorrow for the conclusion of this three-part story.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Published on September 24, 2021 04:00

September 23, 2021

Hugh Whitney Got Away, Part I

That headline would have sufficed a couple dozen times in newspapers across Idaho, Oregon, and Wyoming beginning in June 1911. The details of each story changed, but the headline would serve well enough.

This story is much longer than my usual posts, so I’m going to break it into three parts. Come back the next two days to find out what happened.

For all his escapes to come, Hugh Whitney started out his life of crime in such a reckless way his eventual capture would seem a certainty. He and an accomplice, perhaps his older brother Charlie or a man named Sesker, robbed a saloon in Monida, Montana on June 17, 1911. It would come out later that Whitney may have felt he was owed the money he stole. He had been drinking in the establishment the night before. He was blind drunk, and somehow lost what money he had, whether to a robber or in a card game is unclear.

On that Saturday morning Whitney and his friend went back to the pool hall, guns drawn, not bothering to cover their faces. They had a few free drinks, stole a little cash and whiskey, and sauntered down the street to the train station, where they casually bought tickets that would take them into Idaho.

The saloon keep telephoned Fremont County Deputy Sheriff Samuel Melton to report the robbery. Melton caught the train at Spencer. It didn’t take him long to find Hugh Whitney and the other man in the smoking room playing a game of cards with a couple of traveling men. Melton pulled his gun on the men and placed them under arrest. They laid their own guns on the table where the card game was taking place.

When Melton tried to cuff Whitney, the latter leapt for his gun, grabbed it, and fired twice into the deputy’s body. Melton was hit in the shoulder and chest. The train’s conductor, William Kidd, arrived on the scene at that time. He grabbed Whitney, but the robber shot him once in the chest. The conductor slumped over a seat.

Slipping quietly away at that point might have been the better course of action for Whitney and his partner. Instead, they made their way through the cars of the train blazing away randomly with guns in each hand. Whitney pulled the signal cord, then waited as the train slowed to a stop. He casually walked down the steps of the train, then turned and began firing into the cars as he backed away. This seemed meant to discourage pursuit. Just before he disappeared into the sagebrush, Whitney doffed his hat and waved it theatrically at the passengers.

Conductor Kidd died the next day in a Pocatello Hospital. Deputy Melton struggled near death for weeks but ultimately survived. Hugh Whitney got away.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

This story is much longer than my usual posts, so I’m going to break it into three parts. Come back the next two days to find out what happened.

For all his escapes to come, Hugh Whitney started out his life of crime in such a reckless way his eventual capture would seem a certainty. He and an accomplice, perhaps his older brother Charlie or a man named Sesker, robbed a saloon in Monida, Montana on June 17, 1911. It would come out later that Whitney may have felt he was owed the money he stole. He had been drinking in the establishment the night before. He was blind drunk, and somehow lost what money he had, whether to a robber or in a card game is unclear.

On that Saturday morning Whitney and his friend went back to the pool hall, guns drawn, not bothering to cover their faces. They had a few free drinks, stole a little cash and whiskey, and sauntered down the street to the train station, where they casually bought tickets that would take them into Idaho.

The saloon keep telephoned Fremont County Deputy Sheriff Samuel Melton to report the robbery. Melton caught the train at Spencer. It didn’t take him long to find Hugh Whitney and the other man in the smoking room playing a game of cards with a couple of traveling men. Melton pulled his gun on the men and placed them under arrest. They laid their own guns on the table where the card game was taking place.

When Melton tried to cuff Whitney, the latter leapt for his gun, grabbed it, and fired twice into the deputy’s body. Melton was hit in the shoulder and chest. The train’s conductor, William Kidd, arrived on the scene at that time. He grabbed Whitney, but the robber shot him once in the chest. The conductor slumped over a seat.

Slipping quietly away at that point might have been the better course of action for Whitney and his partner. Instead, they made their way through the cars of the train blazing away randomly with guns in each hand. Whitney pulled the signal cord, then waited as the train slowed to a stop. He casually walked down the steps of the train, then turned and began firing into the cars as he backed away. This seemed meant to discourage pursuit. Just before he disappeared into the sagebrush, Whitney doffed his hat and waved it theatrically at the passengers.

Conductor Kidd died the next day in a Pocatello Hospital. Deputy Melton struggled near death for weeks but ultimately survived. Hugh Whitney got away.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Published on September 23, 2021 04:00

September 22, 2021

Cynthia Mann

Cynthia Mann arrived in Boise an invalid in June 1879. Her journey across southern Idaho, lying on a pallet on the floor of a stagecoach, had been so brutal that at one point she begged to be left at a stage station so she could die beneath a roof.

Born in Kentucky, educated in Kansas, Cynthia Mann began teaching when she was just 18. At age 26 her husband, Samuel Mann, whom she would later divorce, brought her to Boise in the hopes that the change of climate might improve her health. Something did, for she became a dynamo in local affairs related to education, suffrage, politics, and prohibition.

Mann taught at several schools in Boise and in nearby communities. She was often mentioned in early papers as a teacher at Cloverdale, Cole, Central School, and Park School. She was one of the organizers of the Idaho State Teachers Association, and in 1906 ran for Superintendent of Public Schools on the Prohibitionist ticket.

“Lady Mann” was the affectionate nickname given to her by students, who were intensely loyal to her. She taught hundreds of children, and the children of those children, through the years. She is best remembered as the teacher of the “ungraded” school at the Children’s Home Finding and Aid Society of Idaho. That organization began in 1908 as a residence and adoption center for homeless children. It exists today as the Children’s Home Society of Idaho, carrying on its mission of placing children in good homes, though it is no longer a residence institution.

The handsome stone building, designed by Tourtellotte and Company, for the Children’s Home Finding and Aid Society of Idaho is located at 740 E. Warm Springs Avenue. It is so located because of Cynthia Mann. Never a wealthy woman, Mann was savvy about real estate and owned a fair amount of it. She donated almost the entire block where the Society is located today, then went on to make many more donations large and small over the years.

Cynthia Mann was sometimes called a “club woman.” She tirelessly supported education and political reform as one of the early members of the Columbian Club and a founding member of the Boise chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was active in the YWCA, the Business Women’s Club, and the Council of Women Voters.

Man spoke often on the history of suffrage in Idaho and went to Washington, DC more than once to lobby for national women’s suffrage. It was on a trip to DC to visit her brother in 1911 when she almost met her end.

Mrs. Mann was reading the inscription on a “Peace Monument,” erected in memory of soldiers and sailors when a woman driving a horse and buggy knocked her down and ran over her. Bleeding from severe facial injuries and dazed, she was taken to a local Casualty hospital that had a shady reputation.

As she told the story, “I was badly cut about the face, in two places on my lip, sustained a bad gash in my forehead, and my feet were bruised. My head was bothering me more than any other portion of my anatomy, and it was just 24 hours after I begged for it that I got any ice to put on it, and this in the face of the terrible summer heat.”

To her good fortune, Addison T. Smith, secretary to Senator Weldon B. Heyburn of Idaho, read about her accident in the newspaper. “Mr. Smith came for me at once and insisted on taking me to his home and I feel that I owe my life to him and Mrs. Smith.”

The Idaho Statesman, in reporting about the incident, called Cynthia Mann “perhaps the greatest philanthropist in the state of Idaho.”

To, as they say, add insult to injury, Mann was robbed by a nurse while in the hospital. She got her $20 back only after Smith and a Congressman French put pressure on the institution.

Cynthia Mann continued her activism and her teaching until February of 1920. She qualified for a small pension, but at age 66 refused to quit teaching. Her health was starting to fail, so she got her affairs in order, which in her case meant creating a will that gave her remaining funds to her beloved clubs, for hospital work in South America, and $800 for the rehabilitation of a small village, Tilliloy, in northern France. She left most of the money for the construction of the Ward Massacre site monument to the Pioneer Chapter of the D.A.R.

On February 6, 1920, Cynthia Mann died of pneumonia following a bout of influenza.

Lady Mann planned her own funeral to the last detail. The following is a portion of what was read at the service, at her request.

“I had a dream which was not all a dream. I dreamed I was the children’s friend, that I loved them enough to give them pain, if by so doing, they might grow up good and true and beautiful in the sight of God. I loved them enough to go without what was unnecessary that they might have what would put good things into their lives: sweet thoughts and beautiful memories.”

Also at her request, Cynthia Mann’s body was carried by a group of her early pupils to be put to rest in Morris Hill Cemetery. Her marker reads, “It was Happiness to Serve.”

Cynthia Mann arrived in Boise in 1879 in such poor health she was unable to stand. Over the next 41 years she would become known as “the children’s friend” and one of Idaho’s best-known philanthropists. This photo was taken of her when she was Cynthia Pease, age 16, in Lawrence, Kansas. Photo Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Cynthia Mann arrived in Boise in 1879 in such poor health she was unable to stand. Over the next 41 years she would become known as “the children’s friend” and one of Idaho’s best-known philanthropists. This photo was taken of her when she was Cynthia Pease, age 16, in Lawrence, Kansas. Photo Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Born in Kentucky, educated in Kansas, Cynthia Mann began teaching when she was just 18. At age 26 her husband, Samuel Mann, whom she would later divorce, brought her to Boise in the hopes that the change of climate might improve her health. Something did, for she became a dynamo in local affairs related to education, suffrage, politics, and prohibition.

Mann taught at several schools in Boise and in nearby communities. She was often mentioned in early papers as a teacher at Cloverdale, Cole, Central School, and Park School. She was one of the organizers of the Idaho State Teachers Association, and in 1906 ran for Superintendent of Public Schools on the Prohibitionist ticket.

“Lady Mann” was the affectionate nickname given to her by students, who were intensely loyal to her. She taught hundreds of children, and the children of those children, through the years. She is best remembered as the teacher of the “ungraded” school at the Children’s Home Finding and Aid Society of Idaho. That organization began in 1908 as a residence and adoption center for homeless children. It exists today as the Children’s Home Society of Idaho, carrying on its mission of placing children in good homes, though it is no longer a residence institution.

The handsome stone building, designed by Tourtellotte and Company, for the Children’s Home Finding and Aid Society of Idaho is located at 740 E. Warm Springs Avenue. It is so located because of Cynthia Mann. Never a wealthy woman, Mann was savvy about real estate and owned a fair amount of it. She donated almost the entire block where the Society is located today, then went on to make many more donations large and small over the years.

Cynthia Mann was sometimes called a “club woman.” She tirelessly supported education and political reform as one of the early members of the Columbian Club and a founding member of the Boise chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was active in the YWCA, the Business Women’s Club, and the Council of Women Voters.

Man spoke often on the history of suffrage in Idaho and went to Washington, DC more than once to lobby for national women’s suffrage. It was on a trip to DC to visit her brother in 1911 when she almost met her end.

Mrs. Mann was reading the inscription on a “Peace Monument,” erected in memory of soldiers and sailors when a woman driving a horse and buggy knocked her down and ran over her. Bleeding from severe facial injuries and dazed, she was taken to a local Casualty hospital that had a shady reputation.

As she told the story, “I was badly cut about the face, in two places on my lip, sustained a bad gash in my forehead, and my feet were bruised. My head was bothering me more than any other portion of my anatomy, and it was just 24 hours after I begged for it that I got any ice to put on it, and this in the face of the terrible summer heat.”

To her good fortune, Addison T. Smith, secretary to Senator Weldon B. Heyburn of Idaho, read about her accident in the newspaper. “Mr. Smith came for me at once and insisted on taking me to his home and I feel that I owe my life to him and Mrs. Smith.”

The Idaho Statesman, in reporting about the incident, called Cynthia Mann “perhaps the greatest philanthropist in the state of Idaho.”

To, as they say, add insult to injury, Mann was robbed by a nurse while in the hospital. She got her $20 back only after Smith and a Congressman French put pressure on the institution.

Cynthia Mann continued her activism and her teaching until February of 1920. She qualified for a small pension, but at age 66 refused to quit teaching. Her health was starting to fail, so she got her affairs in order, which in her case meant creating a will that gave her remaining funds to her beloved clubs, for hospital work in South America, and $800 for the rehabilitation of a small village, Tilliloy, in northern France. She left most of the money for the construction of the Ward Massacre site monument to the Pioneer Chapter of the D.A.R.

On February 6, 1920, Cynthia Mann died of pneumonia following a bout of influenza.

Lady Mann planned her own funeral to the last detail. The following is a portion of what was read at the service, at her request.

“I had a dream which was not all a dream. I dreamed I was the children’s friend, that I loved them enough to give them pain, if by so doing, they might grow up good and true and beautiful in the sight of God. I loved them enough to go without what was unnecessary that they might have what would put good things into their lives: sweet thoughts and beautiful memories.”

Also at her request, Cynthia Mann’s body was carried by a group of her early pupils to be put to rest in Morris Hill Cemetery. Her marker reads, “It was Happiness to Serve.”

Cynthia Mann arrived in Boise in 1879 in such poor health she was unable to stand. Over the next 41 years she would become known as “the children’s friend” and one of Idaho’s best-known philanthropists. This photo was taken of her when she was Cynthia Pease, age 16, in Lawrence, Kansas. Photo Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Cynthia Mann arrived in Boise in 1879 in such poor health she was unable to stand. Over the next 41 years she would become known as “the children’s friend” and one of Idaho’s best-known philanthropists. This photo was taken of her when she was Cynthia Pease, age 16, in Lawrence, Kansas. Photo Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on September 22, 2021 04:00

September 21, 2021

An Indian Education

The sad looking wreck of a school shown in the black and white picture accompanying this column represented an enormous improvement for the children of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. Built in 1937, the Lincoln Creek Day School operated only until 1944. It was part of a last-ditch effort from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to indoctrinate Shoshone and Bannock children into white culture. After this school, and a couple of others like it on the reservation were closed, Indian children most often began enrolling in regular public schools.

The Lincoln Creek Day School was an improvement over the Lincoln Creek Boarding School which was built at the first site of the military Fort Hall a few miles away. Children were cajoled to attend the day school to receive an education during the day and allowed to go home to their families at night. Like many such schools on reservations around the country, the earlier boarding school was much like a prison. Beginning in 1882 children were taken from their families, often by reservation police, and forced to live at the school in sometimes dangerous conditions.

At the Fort Hall boarding school children would attend classes during the morning hours. In the afternoon the girls would work in the kitchen, laundry, or sewing room, while the boys raised crops for school use and tended milk cows. All wore uniforms and most got new names. Siblings from a family might end up with two or three surnames.

Sickness spread quickly in the cramped boarding school. In 1891, ten students died from scarlet fever. Some students committed suicide. Years later students remembered playing in the schoolyard and finding bones of buried children at the Lincoln Creek Boarding School.

The attitude of the government was probably best summed up by the following quote.

"The Indians must conform to ‘the white man's ways,' peaceably if they will, forcibly if they must. They must adjust themselves to their environment, and conform their mode of living substantially to our civilization. This civilization may not be the best possible, but it is the best the Indians can get. They can not escape it, and must either conform to it or be crushed by it." –Thomas Morgan, US Commissioner of Indian Affairs, October 1889

Dr. Brigham Madsen, prominent historian of the early West wrote in his book, The Northern Shoshoni, "An ironic footnote to the educational troubles at Fort Hall came in a directive from the commissioner's office in August 1892 that all Indian schools were to hold an appropriate celebration in honor of Columbus Day in ‘line with practices and exercises of the public schools of this country.' Furthermore, the ‘interest and enthusiasm' of the children' were to be ‘thoroughly aroused.' No doubt many of the Shoshoni and Bannock wished Columbus had discovered some other country."

It is important to remember even the dark side of our history. All traces of the Lincoln Creek Boarding School are gone, but the Tribe is working to preserve The Lincoln Creek Day School. The Idaho Heritage Trust has been helping them do that with several grants in recent years. Once the renovation is completed, it will become a community center for that section of the reservation.

The Lincoln Creek Day School had fallen into disuse and become an attraction for vandals by latter part of the Twentieth Century when this picture was taken.

The Lincoln Creek Day School had fallen into disuse and become an attraction for vandals by latter part of the Twentieth Century when this picture was taken.

There is still much to do inside the Lincoln Creek Day School, but the exterior of the building now shows the results of much loving attention.

There is still much to do inside the Lincoln Creek Day School, but the exterior of the building now shows the results of much loving attention.

The Lincoln Creek Day School was an improvement over the Lincoln Creek Boarding School which was built at the first site of the military Fort Hall a few miles away. Children were cajoled to attend the day school to receive an education during the day and allowed to go home to their families at night. Like many such schools on reservations around the country, the earlier boarding school was much like a prison. Beginning in 1882 children were taken from their families, often by reservation police, and forced to live at the school in sometimes dangerous conditions.

At the Fort Hall boarding school children would attend classes during the morning hours. In the afternoon the girls would work in the kitchen, laundry, or sewing room, while the boys raised crops for school use and tended milk cows. All wore uniforms and most got new names. Siblings from a family might end up with two or three surnames.

Sickness spread quickly in the cramped boarding school. In 1891, ten students died from scarlet fever. Some students committed suicide. Years later students remembered playing in the schoolyard and finding bones of buried children at the Lincoln Creek Boarding School.

The attitude of the government was probably best summed up by the following quote.

"The Indians must conform to ‘the white man's ways,' peaceably if they will, forcibly if they must. They must adjust themselves to their environment, and conform their mode of living substantially to our civilization. This civilization may not be the best possible, but it is the best the Indians can get. They can not escape it, and must either conform to it or be crushed by it." –Thomas Morgan, US Commissioner of Indian Affairs, October 1889

Dr. Brigham Madsen, prominent historian of the early West wrote in his book, The Northern Shoshoni, "An ironic footnote to the educational troubles at Fort Hall came in a directive from the commissioner's office in August 1892 that all Indian schools were to hold an appropriate celebration in honor of Columbus Day in ‘line with practices and exercises of the public schools of this country.' Furthermore, the ‘interest and enthusiasm' of the children' were to be ‘thoroughly aroused.' No doubt many of the Shoshoni and Bannock wished Columbus had discovered some other country."

It is important to remember even the dark side of our history. All traces of the Lincoln Creek Boarding School are gone, but the Tribe is working to preserve The Lincoln Creek Day School. The Idaho Heritage Trust has been helping them do that with several grants in recent years. Once the renovation is completed, it will become a community center for that section of the reservation.

The Lincoln Creek Day School had fallen into disuse and become an attraction for vandals by latter part of the Twentieth Century when this picture was taken.

The Lincoln Creek Day School had fallen into disuse and become an attraction for vandals by latter part of the Twentieth Century when this picture was taken. There is still much to do inside the Lincoln Creek Day School, but the exterior of the building now shows the results of much loving attention.

There is still much to do inside the Lincoln Creek Day School, but the exterior of the building now shows the results of much loving attention.

Published on September 21, 2021 04:00

September 20, 2021

Byron Defenbach

As a writer who focuses on the history of Idaho, I inevitably run across others who did the same, and are now a part of history themselves. Vardis Fisher, for instance, wrote quite a lot of Idaho history for the Idaho Writers Project. Most of that appeared in books produced for the Works Project Administration (WPA) effort. One writer I enjoy was Dick d’Easum. I’m particularly attracted to him because his writing style was often a little snide and quirky, something I relish, and because he, too, wrote newspaper columns and books. Dick was the information director for a state natural resources agency, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. I held the same position with the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

But enough about Dick, at least for today. This post is about a man who wrote formal Idaho history books, a popular book about Native American heroines, and a regular newspaper column. Those were all passions of Byron Defenbach, but he also had a day job. Several of them, in fact.

Defenbach was deeply involved in government almost from the time he moved to Sandpoint around 1900. In the first few years of the Twentieth Century he served as mayor of the town, the Bonner County Assessor, and had a few terms as an Idaho state senator under his belt. He was also the postmaster of Sandpoint.

In 1915, Idaho created the State Board of Accountancy. Defenbach had received a bookkeeping and accountancy certificate from Kinman Business School in Spokane, so he rushed to Boise to become a Certified Public Accountant. Defenbach family lore has it that the handful of men standing in the office waiting to be issued a certificate drew straws to see who would go first. Byron Defenbach won. He received certificate number one, making him the first CPA in Idaho. He would later serve on the Idaho State Board of Accountancy and the Idaho State Tax Commission.

Defenbach established an accounting firm in Lewiston with two sons. They also had a Pocatello office. Many snippets in Idaho newspapers across the state in the 20s and 30s tell about him coming to town to conduct an audit of city or county books.

Active in the Republican party, and an established money man, Defenbach was elected Idaho State Treasurer in 1927, serving in that office until 1930. That entailed a move to Boise, where he would make a permanent home. In 1932 he ran for governor, losing to Democrat C. Ben Ross.

It was likely not an accident that Defenbach began writing a regular column for Idaho newspapers while still state treasurer in 1928. It served to get his name in front of voters for about three years leading up to his unsuccessful run for governor.

The columns, under the title “The State We Live In,” were not strictly Idaho history. He wrote many about Idaho institutions, why they were formed, and how they were run. Not coincidentally, this showed that he had a good grasp of issues regarding state normal schools, the Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind, State Hospital South, the Old Soldiers Home, the reform school, and on and on. He wrote about gold and silver and geology in general. He wrote about the weather.

Defenbach was an Idaho booster. He was part of a campaign to make City of Rocks a national monument. In a 1929 column he called the site “Goblin City” and compared it favorably to Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave and Garden of the Gods in Colorado. He ended his column with a paragraph that summed up his feelings about the site and gave some indication of the reach of his writings: “It is strange that so few, even of Idaho people, know of its existence, and it is to be regretted that greater efforts are not made to advertise, popularize, and capitalize this possession, unquestionably one of the outstanding show places of the state we live in. How many of the thirty-odd thousand readers of the seventy Idaho papers printing this article, ever heard of it before?”

City of Rocks, jointly operated by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service, became City of Rocks National Reserve in 1988.

Byron Defenbach, author of a The State We Live In, the three-volume Idaho the Place and its People—A History of the Gem State from Prehistoric Times to the Present Days, and Red Heroines of the Northwest passed away in 1947 at age 77.

My thanks to Defenbach’s grandson, also named Byron Defenbach, for his contribution to this post.

Byron Defenbach as a dapper young man. From the Defenbach family collection.

Byron Defenbach as a dapper young man. From the Defenbach family collection.

But enough about Dick, at least for today. This post is about a man who wrote formal Idaho history books, a popular book about Native American heroines, and a regular newspaper column. Those were all passions of Byron Defenbach, but he also had a day job. Several of them, in fact.

Defenbach was deeply involved in government almost from the time he moved to Sandpoint around 1900. In the first few years of the Twentieth Century he served as mayor of the town, the Bonner County Assessor, and had a few terms as an Idaho state senator under his belt. He was also the postmaster of Sandpoint.

In 1915, Idaho created the State Board of Accountancy. Defenbach had received a bookkeeping and accountancy certificate from Kinman Business School in Spokane, so he rushed to Boise to become a Certified Public Accountant. Defenbach family lore has it that the handful of men standing in the office waiting to be issued a certificate drew straws to see who would go first. Byron Defenbach won. He received certificate number one, making him the first CPA in Idaho. He would later serve on the Idaho State Board of Accountancy and the Idaho State Tax Commission.

Defenbach established an accounting firm in Lewiston with two sons. They also had a Pocatello office. Many snippets in Idaho newspapers across the state in the 20s and 30s tell about him coming to town to conduct an audit of city or county books.

Active in the Republican party, and an established money man, Defenbach was elected Idaho State Treasurer in 1927, serving in that office until 1930. That entailed a move to Boise, where he would make a permanent home. In 1932 he ran for governor, losing to Democrat C. Ben Ross.

It was likely not an accident that Defenbach began writing a regular column for Idaho newspapers while still state treasurer in 1928. It served to get his name in front of voters for about three years leading up to his unsuccessful run for governor.

The columns, under the title “The State We Live In,” were not strictly Idaho history. He wrote many about Idaho institutions, why they were formed, and how they were run. Not coincidentally, this showed that he had a good grasp of issues regarding state normal schools, the Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind, State Hospital South, the Old Soldiers Home, the reform school, and on and on. He wrote about gold and silver and geology in general. He wrote about the weather.

Defenbach was an Idaho booster. He was part of a campaign to make City of Rocks a national monument. In a 1929 column he called the site “Goblin City” and compared it favorably to Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave and Garden of the Gods in Colorado. He ended his column with a paragraph that summed up his feelings about the site and gave some indication of the reach of his writings: “It is strange that so few, even of Idaho people, know of its existence, and it is to be regretted that greater efforts are not made to advertise, popularize, and capitalize this possession, unquestionably one of the outstanding show places of the state we live in. How many of the thirty-odd thousand readers of the seventy Idaho papers printing this article, ever heard of it before?”

City of Rocks, jointly operated by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service, became City of Rocks National Reserve in 1988.

Byron Defenbach, author of a The State We Live In, the three-volume Idaho the Place and its People—A History of the Gem State from Prehistoric Times to the Present Days, and Red Heroines of the Northwest passed away in 1947 at age 77.

My thanks to Defenbach’s grandson, also named Byron Defenbach, for his contribution to this post.

Byron Defenbach as a dapper young man. From the Defenbach family collection.

Byron Defenbach as a dapper young man. From the Defenbach family collection.

Published on September 20, 2021 04:00

September 19, 2021

The Legend of Marie Dorian, Part II

When we left off yesterday, the Astorians—those still alive—had made it to Fort Astoria near the mouth of the Columbia. Marie and Pierre Dorion and their two children stayed at the fort a little over a year, then joined others on a beaver trapping expedition for the Pacific Fur Company in July 1813.

The men set up camp at the mouth of the Boise River near present-day Parma. After a time they determined a better site for their base would be along the Boise nearer present-day Caldwell. Marie and the kids, along with a few men, took care of things at the base camp while the trappers went out on their rounds in small groups. Pierre worked the Boise River along with Giles Le Clerc and Jacob Reznor.

In January 1814, the new year arrived with word from friendly local Indians that a band of Bannocks was terrorizing the trapping camps. Fearing for the safety of her husband, Marie piled the two kids on a horse with her and set out up the Boise to warn the trappers.

Three days later she arrived at the hut they had built, a little too late. Pierre and Jacob Reznor had been killed. Le Clerc was badly wounded. Marie got him up on a horse that was wandering near the camp, in spite of his protestations for her to leave him. The four of them began trekking back to the base camp. Two days later, Le Clerc died from his wounds.

Arriving at the base camp Marie Dorion found devastation. Everyone in camp had been killed and their bodies mutilated. All the weapons but a couple of knives had been looted. Marie gather together some meager supplies, including a buffalo robe and a couple of deerskins, and did what she had to do. In the dead of winter, she set out with her children for Fort Astoria, 500 miles away.

Her first major obstacle was the Snake River. She swam the horses across, dragging a float she had improvised for their supplies. Marie Dorion fought snowdrifts then for nine days up Burnt River, north along the Powder River, and across the hills to the Grande Ronde and to the foot of the Blue Mountains. Near today’s La Grande, Oregon, exhausted, Marie stopped and built a crude shelter beneath a rock overhang.

Marie and her children holed up in the shelter for 53 days. Early on Marie killed the horses, smoking their meat to preserve it. She caught mice with horsehair snares and foraged for a few frozen berries. Marie rationed the food through the winter. By mid-March it was getting dangerously low. They abandoned their shelter and set out on foot for the west. Marie looked for landmarks she might recognize from her trek to Astoria nearly two years before. But looking became agony. At that altitude everything was still blindingly white.

John Baptiste excitedly pointed to tracks in the snow. When they went to them their joy evaporated. The tracks were their own. They had been traveling in a circle.

The three sought the shelter of nearby brush and holed up for three days to let Marie’s eyes rest. The reprieve from staring into the maddening reflections did the trick. She could again see, but they were out of food. Growing weaker each day they were near the point where Paul, the youngest child, could no longer go on and Marie had lost the capacity to carry him.

Marie saw smoke. Quickly she found a rude shelter in the brush for the children and secreted them away there. Then she went to determine the source of the smoke. She found a camp from the Walla Walla Tribe. Some of them remembered her from two years before when she and the Astorians had travelled through the country. She was saved at last. The Walla Wallas took the three back to their camp where members of the Astoria group found them a few weeks later.

Marie Dorion would live out the rest of her life in the Northwest, first at Fort Okanagon near present-day Brewster, Washington, where she lived with a French-Canadian trapper named Venier. They had a daughter in about 1819 they named Marguerite. Later, Marie met Jean Baptiste Toupin, another French-Canadian. They had two children together, Francois and Marianne, and were married in a Roman Catholic ceremony.

The Toupins moved to the Willamette Valley and settled on a farm in 1841. Marie died there in 1850. The priest who recorded her death estimated her age at 100. After what she had been through, she may have looked very old and worn out, but she would have been about 64.

Marie Dorion became well-known in her lifetime thanks to Astoria: Or, Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains , written by Washington Irving and published in 1836.* She is memorialized at Madame Dorion Memorial Park near Wallula, Washington, and has a residence hall named after her at Eastern Oregon University in La Grande. Outside of North Powder, Oregon a memorial plaque marks the likely area where she gave birth to her third child while with the Wilson Price Hunt expedition. A memorial to her was installed at the St. Louis Catholic Church in Gervais, Oregon, just north of Salem, in 2014

Red Heroines of the Northwest , by Byron Defenbach, written in 1929, tells her story extensively. Contemporary accounts include Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson's Lost Pacific Empire , by Peter Stark, and the Tender Ties Trilogy , by Jane Kirkpatrick.*

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

The men set up camp at the mouth of the Boise River near present-day Parma. After a time they determined a better site for their base would be along the Boise nearer present-day Caldwell. Marie and the kids, along with a few men, took care of things at the base camp while the trappers went out on their rounds in small groups. Pierre worked the Boise River along with Giles Le Clerc and Jacob Reznor.

In January 1814, the new year arrived with word from friendly local Indians that a band of Bannocks was terrorizing the trapping camps. Fearing for the safety of her husband, Marie piled the two kids on a horse with her and set out up the Boise to warn the trappers.

Three days later she arrived at the hut they had built, a little too late. Pierre and Jacob Reznor had been killed. Le Clerc was badly wounded. Marie got him up on a horse that was wandering near the camp, in spite of his protestations for her to leave him. The four of them began trekking back to the base camp. Two days later, Le Clerc died from his wounds.

Arriving at the base camp Marie Dorion found devastation. Everyone in camp had been killed and their bodies mutilated. All the weapons but a couple of knives had been looted. Marie gather together some meager supplies, including a buffalo robe and a couple of deerskins, and did what she had to do. In the dead of winter, she set out with her children for Fort Astoria, 500 miles away.

Her first major obstacle was the Snake River. She swam the horses across, dragging a float she had improvised for their supplies. Marie Dorion fought snowdrifts then for nine days up Burnt River, north along the Powder River, and across the hills to the Grande Ronde and to the foot of the Blue Mountains. Near today’s La Grande, Oregon, exhausted, Marie stopped and built a crude shelter beneath a rock overhang.

Marie and her children holed up in the shelter for 53 days. Early on Marie killed the horses, smoking their meat to preserve it. She caught mice with horsehair snares and foraged for a few frozen berries. Marie rationed the food through the winter. By mid-March it was getting dangerously low. They abandoned their shelter and set out on foot for the west. Marie looked for landmarks she might recognize from her trek to Astoria nearly two years before. But looking became agony. At that altitude everything was still blindingly white.

John Baptiste excitedly pointed to tracks in the snow. When they went to them their joy evaporated. The tracks were their own. They had been traveling in a circle.

The three sought the shelter of nearby brush and holed up for three days to let Marie’s eyes rest. The reprieve from staring into the maddening reflections did the trick. She could again see, but they were out of food. Growing weaker each day they were near the point where Paul, the youngest child, could no longer go on and Marie had lost the capacity to carry him.

Marie saw smoke. Quickly she found a rude shelter in the brush for the children and secreted them away there. Then she went to determine the source of the smoke. She found a camp from the Walla Walla Tribe. Some of them remembered her from two years before when she and the Astorians had travelled through the country. She was saved at last. The Walla Wallas took the three back to their camp where members of the Astoria group found them a few weeks later.

Marie Dorion would live out the rest of her life in the Northwest, first at Fort Okanagon near present-day Brewster, Washington, where she lived with a French-Canadian trapper named Venier. They had a daughter in about 1819 they named Marguerite. Later, Marie met Jean Baptiste Toupin, another French-Canadian. They had two children together, Francois and Marianne, and were married in a Roman Catholic ceremony.

The Toupins moved to the Willamette Valley and settled on a farm in 1841. Marie died there in 1850. The priest who recorded her death estimated her age at 100. After what she had been through, she may have looked very old and worn out, but she would have been about 64.

Marie Dorion became well-known in her lifetime thanks to Astoria: Or, Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains , written by Washington Irving and published in 1836.* She is memorialized at Madame Dorion Memorial Park near Wallula, Washington, and has a residence hall named after her at Eastern Oregon University in La Grande. Outside of North Powder, Oregon a memorial plaque marks the likely area where she gave birth to her third child while with the Wilson Price Hunt expedition. A memorial to her was installed at the St. Louis Catholic Church in Gervais, Oregon, just north of Salem, in 2014

Red Heroines of the Northwest , by Byron Defenbach, written in 1929, tells her story extensively. Contemporary accounts include Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson's Lost Pacific Empire , by Peter Stark, and the Tender Ties Trilogy , by Jane Kirkpatrick.*

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Published on September 19, 2021 04:00

September 18, 2021

The Legend of Marie Dorion, Part I

This story is a long one, so I’ll to split it into two posts.

Let’s start with an Indian woman, born in 1786, who married a man of French-Canadian heritage. She and her husband served as interpreters to a famous expedition west in the early part of the 18th century. That trek took them across what would become Idaho. She went along to assist with interpretation, taking her son, John Baptiste with them. Her name has been the source of some speculation over the years, though it wasn’t because the pronunciation was in dispute. Marie is a common enough name, though not so common at that time for an Indian woman. The dispute has been whether she ever had a non-Anglo name.

No, this wasn’t Sacajawea, though the parallels are striking. This was Marie Dorion, a contemporary of Sacajawea perhaps born the same year. She very likely knew Sacajawea when they both lived in St. Louis.

Sacajawea was Shoshoni; Marie Dorion was Iowan (the tribe, not the state).

Marie’s husband was Pierre Dorion, Jr. His father, who had served as an interpreter for Lewis and Clark, was French-Canadian and his mother was Yankton-Sioux. With Marie’s Iowan heritage, the Dorions became valued members of the expedition. Between the two of them they spoke French, English, Spanish, and several Indian dialects.

The expedition, which I have studiously avoided naming up to this point, was one financed by fur magnate John Jacob Astor in 1810 in an attempt to claim trapping territory for his newly formed Pacific Fur Company. Astor and his partners chartered two expeditions, one by sea and one by land and river. The members of the ocean expedition built an outpost on the Columbia called Fort Astoria. The fort became the first American settlement in the territory. The Hudson Bay Company, and not incidentally, the British, had ambitions in the area as well.

Astor partnered with Wilson Price Hunt for the overland expedition that was to launch from St. Louis and explore trapping territory all the way to Fort Astoria. Hunt, a New Jersey native and St. Louis merchant would lead the cross-country expedition, in spite of his lack of experience in such endeavors. The group was often called the “Astorians” though Astor himself wasn’t along on either expedition.

On April 21, 1811 the Hunt Party left their winter camp at Fort Osage, near present-day Sibley, Missouri to begin the bulk of their trip west. The ocean-going Astorians had done their part, establishing Fort Astoria nine days earlier, though not without some loss of life due to the treacherous sand bar at the mouth of the Columbia.

The Hunt Party was a large one, consisting of some 60 men. Oh, and one woman. Most were French-Canadian river men, known as voyageurs, since much of the expedition was expected to take place on rivers, just as the Lewis and Clark Expedition had a few years earlier. Worried about a confrontation with hostile Blackfeet, the Hunt Party would cut down through present-day Wyoming and cross the Continental Divide at the headwaters of the Snake River. They hoped to take that unexplored river all the way to Fort Astoria. Abandoning their horses near the headwaters, the Hunt Party built 15 dugout canoes to that end.

The Hunt Party ran into a tad of trouble at Caldron Linn, about 340 miles downriver from where they put in. On October 28, 1811, they lost a canoe, a man, and the desire to travel further on the Snake, which, after a few days of scouting, they declared unnavigable.

Without horses and with suddenly useless dugout canoes, the Hunt Party cached most of their supplies and split up, with about half travelling on either side of the Snake River, setting out on foot for Fort Astoria. Smaller parties would have a better chance of finding enough food to sustain them.

Hunt took the northern route. The Dorian family, Pierre, Marie, John Baptiste, who was four, and Paul, who was two, walked along with him. Well, Marie Dorion carried the two-year-old much of the way, though she was by this time several months pregnant.

They were able to trade for a couple of horses near today’s Boise, but by the time December rolled around the horses had become food. Near starvation they stole several horses from a Shoshoni camp to help them along their way.

The Snake River, which they called the Mad River, proved more obstacle than travel route. Hunt’s party struggled downstream into Hells Canyon only to find the rest of their party slogging back upstream on the opposite side of the river, discouraged by the steep cliffs and relentless rapids ahead.

Marie stayed behind while the rest of the expedition set out on December 30, 1811. She gave birth to her baby, alone, near today’s North Powder, Oregon. Marie then caught up with the rest of party the next day. The baby died a few days later. Most of the bedraggled Hunt Party—45 of the original 60—finally made it to Astoria on May 11, 1812.

And that’s where we’ll leave the story for today. Stop by tomorrow to hear the heroics of Marie Dorian when she travelled back to present-day Idaho.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Let’s start with an Indian woman, born in 1786, who married a man of French-Canadian heritage. She and her husband served as interpreters to a famous expedition west in the early part of the 18th century. That trek took them across what would become Idaho. She went along to assist with interpretation, taking her son, John Baptiste with them. Her name has been the source of some speculation over the years, though it wasn’t because the pronunciation was in dispute. Marie is a common enough name, though not so common at that time for an Indian woman. The dispute has been whether she ever had a non-Anglo name.

No, this wasn’t Sacajawea, though the parallels are striking. This was Marie Dorion, a contemporary of Sacajawea perhaps born the same year. She very likely knew Sacajawea when they both lived in St. Louis.

Sacajawea was Shoshoni; Marie Dorion was Iowan (the tribe, not the state).

Marie’s husband was Pierre Dorion, Jr. His father, who had served as an interpreter for Lewis and Clark, was French-Canadian and his mother was Yankton-Sioux. With Marie’s Iowan heritage, the Dorions became valued members of the expedition. Between the two of them they spoke French, English, Spanish, and several Indian dialects.

The expedition, which I have studiously avoided naming up to this point, was one financed by fur magnate John Jacob Astor in 1810 in an attempt to claim trapping territory for his newly formed Pacific Fur Company. Astor and his partners chartered two expeditions, one by sea and one by land and river. The members of the ocean expedition built an outpost on the Columbia called Fort Astoria. The fort became the first American settlement in the territory. The Hudson Bay Company, and not incidentally, the British, had ambitions in the area as well.

Astor partnered with Wilson Price Hunt for the overland expedition that was to launch from St. Louis and explore trapping territory all the way to Fort Astoria. Hunt, a New Jersey native and St. Louis merchant would lead the cross-country expedition, in spite of his lack of experience in such endeavors. The group was often called the “Astorians” though Astor himself wasn’t along on either expedition.

On April 21, 1811 the Hunt Party left their winter camp at Fort Osage, near present-day Sibley, Missouri to begin the bulk of their trip west. The ocean-going Astorians had done their part, establishing Fort Astoria nine days earlier, though not without some loss of life due to the treacherous sand bar at the mouth of the Columbia.

The Hunt Party was a large one, consisting of some 60 men. Oh, and one woman. Most were French-Canadian river men, known as voyageurs, since much of the expedition was expected to take place on rivers, just as the Lewis and Clark Expedition had a few years earlier. Worried about a confrontation with hostile Blackfeet, the Hunt Party would cut down through present-day Wyoming and cross the Continental Divide at the headwaters of the Snake River. They hoped to take that unexplored river all the way to Fort Astoria. Abandoning their horses near the headwaters, the Hunt Party built 15 dugout canoes to that end.

The Hunt Party ran into a tad of trouble at Caldron Linn, about 340 miles downriver from where they put in. On October 28, 1811, they lost a canoe, a man, and the desire to travel further on the Snake, which, after a few days of scouting, they declared unnavigable.

Without horses and with suddenly useless dugout canoes, the Hunt Party cached most of their supplies and split up, with about half travelling on either side of the Snake River, setting out on foot for Fort Astoria. Smaller parties would have a better chance of finding enough food to sustain them.

Hunt took the northern route. The Dorian family, Pierre, Marie, John Baptiste, who was four, and Paul, who was two, walked along with him. Well, Marie Dorion carried the two-year-old much of the way, though she was by this time several months pregnant.

They were able to trade for a couple of horses near today’s Boise, but by the time December rolled around the horses had become food. Near starvation they stole several horses from a Shoshoni camp to help them along their way.

The Snake River, which they called the Mad River, proved more obstacle than travel route. Hunt’s party struggled downstream into Hells Canyon only to find the rest of their party slogging back upstream on the opposite side of the river, discouraged by the steep cliffs and relentless rapids ahead.

Marie stayed behind while the rest of the expedition set out on December 30, 1811. She gave birth to her baby, alone, near today’s North Powder, Oregon. Marie then caught up with the rest of party the next day. The baby died a few days later. Most of the bedraggled Hunt Party—45 of the original 60—finally made it to Astoria on May 11, 1812.

And that’s where we’ll leave the story for today. Stop by tomorrow to hear the heroics of Marie Dorian when she travelled back to present-day Idaho.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Published on September 18, 2021 04:00

September 17, 2021

The Blackfoot Sugar Factory