Rick Just's Blog, page 117

August 17, 2021

The Presto Post Office

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

The reason there is a place in in Idaho called Presto (not Preston), is that there was a Presto Post Office from August 6, 1889 through February 28, 1907. When you have a post office, you need to call it something. Nels Just put “Presto” on the application. The name came from neighbor Presto Burrell who had settled in the Blackfoot River Valley a few months before the Justs did.

The first postmaster, a man who lived for a time in the Just home, was Albert F. McElroy. He held that position for less than a year when Emma Just took over as postmistress on November 13, 1890. Emma’s son, Fred Bennett, was named the postmaster on April 27, 1904 and held that position until the office was discontinued.

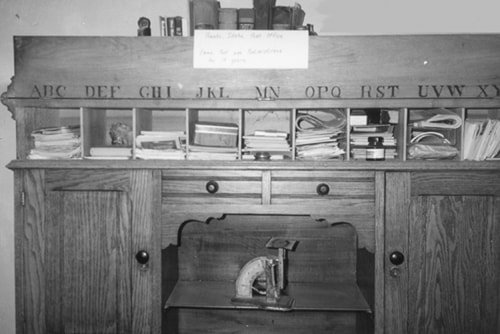

When we think of a post office today, we think of a building. The Presto Post Office was a desk. It resided in the home of Nels and Emma Just until the desk moved to the home of Fred Bennett in 1904. Once there was no longer a need for a post officer—the Shelley Post Office took over that roll—the desk moved back to the Just home to serve as a piece of furniture. It is still in the home today.

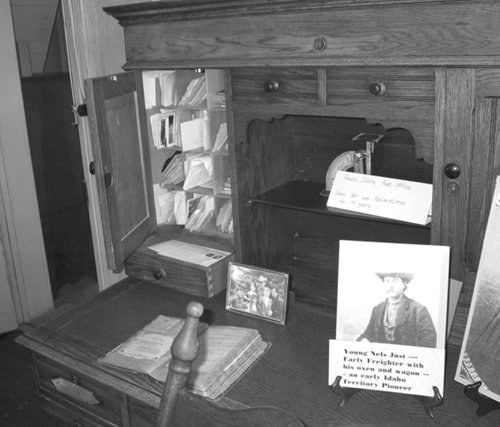

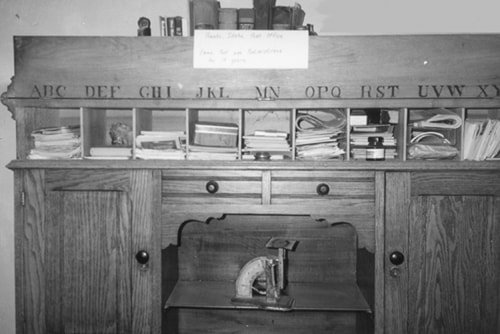

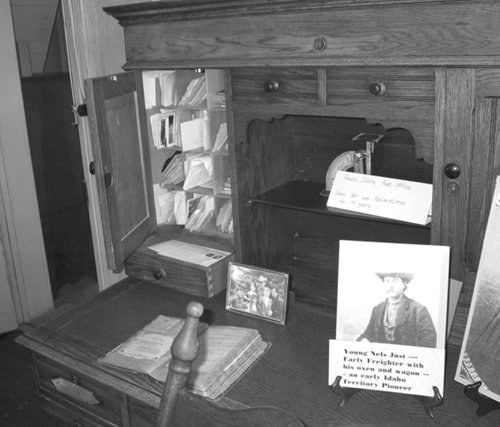

This is the Presto Post Office desk. Note that the top compartment is closed in this picture.

This is the Presto Post Office desk. Note that the top compartment is closed in this picture.  This photo shows the door of the top compartment open, revealing the cubbies for alphabetized mail beneath.

This photo shows the door of the top compartment open, revealing the cubbies for alphabetized mail beneath.

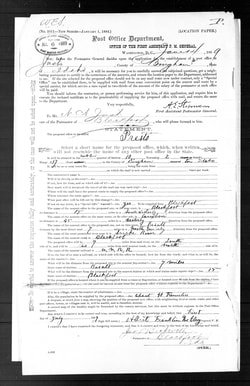

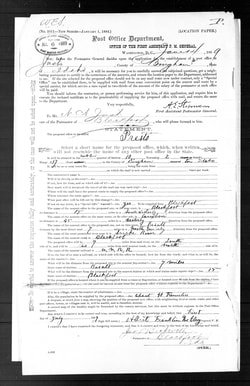

Above is the application for the Presto, Idaho post office.

Above is the application for the Presto, Idaho post office.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

The reason there is a place in in Idaho called Presto (not Preston), is that there was a Presto Post Office from August 6, 1889 through February 28, 1907. When you have a post office, you need to call it something. Nels Just put “Presto” on the application. The name came from neighbor Presto Burrell who had settled in the Blackfoot River Valley a few months before the Justs did.

The first postmaster, a man who lived for a time in the Just home, was Albert F. McElroy. He held that position for less than a year when Emma Just took over as postmistress on November 13, 1890. Emma’s son, Fred Bennett, was named the postmaster on April 27, 1904 and held that position until the office was discontinued.

When we think of a post office today, we think of a building. The Presto Post Office was a desk. It resided in the home of Nels and Emma Just until the desk moved to the home of Fred Bennett in 1904. Once there was no longer a need for a post officer—the Shelley Post Office took over that roll—the desk moved back to the Just home to serve as a piece of furniture. It is still in the home today.

This is the Presto Post Office desk. Note that the top compartment is closed in this picture.

This is the Presto Post Office desk. Note that the top compartment is closed in this picture.  This photo shows the door of the top compartment open, revealing the cubbies for alphabetized mail beneath.

This photo shows the door of the top compartment open, revealing the cubbies for alphabetized mail beneath.

Above is the application for the Presto, Idaho post office.

Above is the application for the Presto, Idaho post office.

Published on August 17, 2021 04:00

August 16, 2021

Restoring an 1887 Map

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

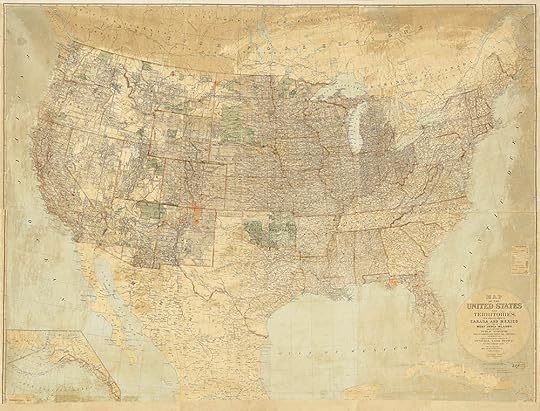

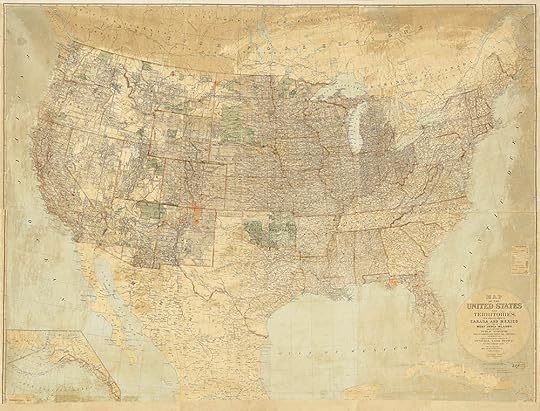

My great grandfather Nels Just, who had recently become a naturalized citizen, was proud of his adopted country. When his brick house along the Blackfoot River was finished in 1887, he ordered a four foot by six foot General Land Office Map of the United States, mounting it to the wall in the hallway of the new house.

The house doubled as the Post Office for Presto, Idaho Territory, then Presto, Idaho beginning in 1890. My great grandmother Emma Just was the postmistress for 13 years, welcoming postal patrons into her home, handing them their mail, and often talking with them about current events, using the map as a conversation tool.

The large map, varnished to ward off fingerprints, had hung unprotected for 127 years. Small pieces of the map had flaked off and it had discolored over the years. In 2014 our family decided to restore and protect the map so it would last at least another century.

With help from the Idaho Heritage Trust, we contracted with a restoration specialist in New York City. To get it to New York, we had to take it off the wall and ship it. That was a process that took several hours. Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus supervised the work.

The map had been mounted on the wall by Nels with lath strips using tacks. The process of safely taking it down included the use of a large “folder” built from fiber board to assure the map stayed flat and did not fall and crumple.

Once we got the map down flat on the large kitchen table in the house, we began removing the lath and tacks. It was then that we discovered that about a one-inch strip at the bottom of the map was missing. Nels had cut it off, none too cleanly. Why? We can’t know, but my guess is that he cut the lath to fit the map, then discovered he’d trimmed the side slats an inch too short. He wasn’t about to harness up a team to take into town to get more lath. So, his solution was just to haggle off the bottom of the map. No one would know. And no one did know until 127 years later. I confess, I would have done the same thing.

We rolled the map on an acid-free cardboard tube, wrapped the map with acid-free paper, placed it in an acid-free box, then placed the box in a length of plastic sewer pipe, filling it out with packing material. We used fitted sewer pipe ends to seal the map and shipped it to New York City.

Restoration on a wall map of this nature first involves removing the map from the original linen backing and then removing the glossy varnish coating the recto. The caustic glues common in the 19th century and the slowly degrading varnish, and exposure to temperature variation, had caused the moderate yellowing and chipping to the map. By having both the linen backing and the varnish removed, the restorer could then access the printed paper map to begin the repair work. When that was finished, the map was laid down on fresh linen and the edging was replaced.

A few months later, the map came back. We had Todd Hanson of Hanson’s Design and Fabrication in Meridian custom build a handsome case for the map, using museum grade Plexiglas to protect it. We displayed the restored map at the Idaho State Historical Archives for a few weeks, and at the Boise Public Library. The Idaho Statehouse hosted it for a day, then it headed to Blackfoot. It was displayed at the Blackfoot Library for a time, then returned to the hallway where it belongs. The 1887 map. This is a scan of the restored map before it was put in its case. Note that the map is much brighter than it was before restoration, but one can still see streaks of varnish. It would have damaged the map to do further removal of the coating. Because of the lighting conditions in the hallway where the map hangs in its new case it is very difficult to get photo of in situ.

The 1887 map. This is a scan of the restored map before it was put in its case. Note that the map is much brighter than it was before restoration, but one can still see streaks of varnish. It would have damaged the map to do further removal of the coating. Because of the lighting conditions in the hallway where the map hangs in its new case it is very difficult to get photo of in situ.  Electricity was long ago shut off in the 1887 house, so we were working with only what natural light came in through the kitchen windows. Some of the details show up better in black and white. For instance, as the map is being flipped over you can see by the backlighting that it is a series of six printed panels taped together on the back.

Electricity was long ago shut off in the 1887 house, so we were working with only what natural light came in through the kitchen windows. Some of the details show up better in black and white. For instance, as the map is being flipped over you can see by the backlighting that it is a series of six printed panels taped together on the back.  Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus, left, gave us instruction on how best to remove the lath once the map was flat on the table. In the background you can see the large plastic tube that would serve as the hard shipping container for the map.

Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus, left, gave us instruction on how best to remove the lath once the map was flat on the table. In the background you can see the large plastic tube that would serve as the hard shipping container for the map.  The map was carefully wrapped and rolled before being placed in an acid-free cardboard box, then inserted into the shipping container.

The map was carefully wrapped and rolled before being placed in an acid-free cardboard box, then inserted into the shipping container.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

My great grandfather Nels Just, who had recently become a naturalized citizen, was proud of his adopted country. When his brick house along the Blackfoot River was finished in 1887, he ordered a four foot by six foot General Land Office Map of the United States, mounting it to the wall in the hallway of the new house.

The house doubled as the Post Office for Presto, Idaho Territory, then Presto, Idaho beginning in 1890. My great grandmother Emma Just was the postmistress for 13 years, welcoming postal patrons into her home, handing them their mail, and often talking with them about current events, using the map as a conversation tool.

The large map, varnished to ward off fingerprints, had hung unprotected for 127 years. Small pieces of the map had flaked off and it had discolored over the years. In 2014 our family decided to restore and protect the map so it would last at least another century.

With help from the Idaho Heritage Trust, we contracted with a restoration specialist in New York City. To get it to New York, we had to take it off the wall and ship it. That was a process that took several hours. Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus supervised the work.

The map had been mounted on the wall by Nels with lath strips using tacks. The process of safely taking it down included the use of a large “folder” built from fiber board to assure the map stayed flat and did not fall and crumple.

Once we got the map down flat on the large kitchen table in the house, we began removing the lath and tacks. It was then that we discovered that about a one-inch strip at the bottom of the map was missing. Nels had cut it off, none too cleanly. Why? We can’t know, but my guess is that he cut the lath to fit the map, then discovered he’d trimmed the side slats an inch too short. He wasn’t about to harness up a team to take into town to get more lath. So, his solution was just to haggle off the bottom of the map. No one would know. And no one did know until 127 years later. I confess, I would have done the same thing.

We rolled the map on an acid-free cardboard tube, wrapped the map with acid-free paper, placed it in an acid-free box, then placed the box in a length of plastic sewer pipe, filling it out with packing material. We used fitted sewer pipe ends to seal the map and shipped it to New York City.

Restoration on a wall map of this nature first involves removing the map from the original linen backing and then removing the glossy varnish coating the recto. The caustic glues common in the 19th century and the slowly degrading varnish, and exposure to temperature variation, had caused the moderate yellowing and chipping to the map. By having both the linen backing and the varnish removed, the restorer could then access the printed paper map to begin the repair work. When that was finished, the map was laid down on fresh linen and the edging was replaced.

A few months later, the map came back. We had Todd Hanson of Hanson’s Design and Fabrication in Meridian custom build a handsome case for the map, using museum grade Plexiglas to protect it. We displayed the restored map at the Idaho State Historical Archives for a few weeks, and at the Boise Public Library. The Idaho Statehouse hosted it for a day, then it headed to Blackfoot. It was displayed at the Blackfoot Library for a time, then returned to the hallway where it belongs.

The 1887 map. This is a scan of the restored map before it was put in its case. Note that the map is much brighter than it was before restoration, but one can still see streaks of varnish. It would have damaged the map to do further removal of the coating. Because of the lighting conditions in the hallway where the map hangs in its new case it is very difficult to get photo of in situ.

The 1887 map. This is a scan of the restored map before it was put in its case. Note that the map is much brighter than it was before restoration, but one can still see streaks of varnish. It would have damaged the map to do further removal of the coating. Because of the lighting conditions in the hallway where the map hangs in its new case it is very difficult to get photo of in situ.  Electricity was long ago shut off in the 1887 house, so we were working with only what natural light came in through the kitchen windows. Some of the details show up better in black and white. For instance, as the map is being flipped over you can see by the backlighting that it is a series of six printed panels taped together on the back.

Electricity was long ago shut off in the 1887 house, so we were working with only what natural light came in through the kitchen windows. Some of the details show up better in black and white. For instance, as the map is being flipped over you can see by the backlighting that it is a series of six printed panels taped together on the back.  Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus, left, gave us instruction on how best to remove the lath once the map was flat on the table. In the background you can see the large plastic tube that would serve as the hard shipping container for the map.

Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus, left, gave us instruction on how best to remove the lath once the map was flat on the table. In the background you can see the large plastic tube that would serve as the hard shipping container for the map.  The map was carefully wrapped and rolled before being placed in an acid-free cardboard box, then inserted into the shipping container.

The map was carefully wrapped and rolled before being placed in an acid-free cardboard box, then inserted into the shipping container.

Published on August 16, 2021 04:00

August 15, 2021

Restoring the Big House

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

Today, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August. The Nels and Emma Just house, known to the family as the Big House, is located on the Blackfoot River about 10 miles east of Blackfoot, Idaho. This brick home was finished in 1887. Given the time involved in forming and firing the bricks, it is likely the project was begun one or two years earlier. The house was constructed on the foundation of a frame house built some years earlier. The large kitchen of the frame house was demolished, allowing the construction of the brick kitchen and dining area to take place while the family lived in the remaining rooms of the original house. When the kitchen was finished, the remainder of the frame house was demolished, and the new brick home was completed.

Nels and Emma raised five boys and one girl in the family home. Their daughter, Agnes Just Reid, and her husband Robert Reid raised five boys there. The house has been unoccupied since 1976, when Agnes Just Reid passed away. Douglass Reid, fourth son of Agnes and Robert, owned the home and kept it untouched for about 35 years after his mother’s death. Shortly before Doug passed away in 2012, he donated the property to the Presto Preservation Association, the nonprofit family association dedicated to preserving the history of Nels and Emma Just and their descendants. The association owns the house today, along with the nearby pioneer cemetery where Nels and Emma are buried. Agnes and Robert’s youngest son, Wallace donated the pioneer cemetery ground to the association, also in 2012.

The Presto Preservation Association is an Idaho Corporation and a 501 (c)3 nonprofit that was formed in 1994 for the purpose of preserving the history of Nels and Emma Just and their descendants. It takes its name from the area where the house is located, Lower Presto, Idaho, which was named by Nels Just in honor of early pioneer Presto Burrell, who was a soldier in Colonel Conner’s California Volunteers.

The Brick Restoration Project

With technical expertise from the Idaho Heritage trust and using a series of matching grants from the same organization, the family has been restoring the brickwork since 2017.

During the project we discovered water damage to the front of the building, both inside

and out, caused by water seeping into the concrete sidewalk and wicking up into the bricks and mortar over the decades.

Many of the original bricks were damaged beyond repair, and earlier repair work that had been done with good intentions had resulted in damaging even more bricks. We were short hundreds of bricks. There are companies that can reproduce bricks very close to original specifications, but we found a better solution.

The property owners of a site south of Blackfoot on the Blackfoot River, just before it joins the Snake River, thought they had a pile of bricks from an old house that had been covered over with soil. We thought it was brick mine. Remarkably, the first settlers in what would become Blackfoot, built a brick home the same year, 1887, as Nels and Emma Just. Fred and Finnetta Garrett Stevens were longtime friends of the Justs. The Stevens home was the center of social activities for many years in Blackfoot, but was eventually abandoned and demolished, probably in the 1960s.

We got permission from the owners of the old Stevens place to mine the bricks. In the spring of 2019, about 20 members of the Reid side of the family began gathering bricks to replace damaged bricks in the Nels and Emma home (see picture).

Also, that spring, we removed the concrete sidewalk and regraded the slope of the lawn to move water away from the front of the house. We installed a new wooden boardwalk in keeping with the original design of the house. At the same time, we repaired some of the woodwork associated with the porch overhang.

Restoration projects often take longer than one thinks, and the Nels and Emma Just house is no exception. One more season of brick restoration will be needed to complete repairs to the damaged brick. Water seepage has softened and deteriorated even some of the inner walls of the house.

The Big House circa 1890.

The Big House circa 1890.  The brick mining crew: From top, Jess Reid, Fred Reid, Mark Pratt, Riggin Oleson, Debbie Reid-Oleson, Ira Oleson and Ruger Oleson; Ott Clark, Cole Clark, Howdy Clark, Bennett Davis, Clara Jensen, Lilly Davis, Gerry Becker, Wendy Pratt, and Harlie Oleson; Front: Ken Davis, Becky Davis, Nils Arnold, Megan Arnold, Zac Davis, Betsy Just, Ginger Reid, Leah Pratt and Seth Pratt.

The brick mining crew: From top, Jess Reid, Fred Reid, Mark Pratt, Riggin Oleson, Debbie Reid-Oleson, Ira Oleson and Ruger Oleson; Ott Clark, Cole Clark, Howdy Clark, Bennett Davis, Clara Jensen, Lilly Davis, Gerry Becker, Wendy Pratt, and Harlie Oleson; Front: Ken Davis, Becky Davis, Nils Arnold, Megan Arnold, Zac Davis, Betsy Just, Ginger Reid, Leah Pratt and Seth Pratt.

Working on repairs to the front of the house.

Working on repairs to the front of the house.  The Big House as it looks today.

The Big House as it looks today.

Today, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August. The Nels and Emma Just house, known to the family as the Big House, is located on the Blackfoot River about 10 miles east of Blackfoot, Idaho. This brick home was finished in 1887. Given the time involved in forming and firing the bricks, it is likely the project was begun one or two years earlier. The house was constructed on the foundation of a frame house built some years earlier. The large kitchen of the frame house was demolished, allowing the construction of the brick kitchen and dining area to take place while the family lived in the remaining rooms of the original house. When the kitchen was finished, the remainder of the frame house was demolished, and the new brick home was completed.

Nels and Emma raised five boys and one girl in the family home. Their daughter, Agnes Just Reid, and her husband Robert Reid raised five boys there. The house has been unoccupied since 1976, when Agnes Just Reid passed away. Douglass Reid, fourth son of Agnes and Robert, owned the home and kept it untouched for about 35 years after his mother’s death. Shortly before Doug passed away in 2012, he donated the property to the Presto Preservation Association, the nonprofit family association dedicated to preserving the history of Nels and Emma Just and their descendants. The association owns the house today, along with the nearby pioneer cemetery where Nels and Emma are buried. Agnes and Robert’s youngest son, Wallace donated the pioneer cemetery ground to the association, also in 2012.

The Presto Preservation Association is an Idaho Corporation and a 501 (c)3 nonprofit that was formed in 1994 for the purpose of preserving the history of Nels and Emma Just and their descendants. It takes its name from the area where the house is located, Lower Presto, Idaho, which was named by Nels Just in honor of early pioneer Presto Burrell, who was a soldier in Colonel Conner’s California Volunteers.

The Brick Restoration Project

With technical expertise from the Idaho Heritage trust and using a series of matching grants from the same organization, the family has been restoring the brickwork since 2017.

During the project we discovered water damage to the front of the building, both inside

and out, caused by water seeping into the concrete sidewalk and wicking up into the bricks and mortar over the decades.

Many of the original bricks were damaged beyond repair, and earlier repair work that had been done with good intentions had resulted in damaging even more bricks. We were short hundreds of bricks. There are companies that can reproduce bricks very close to original specifications, but we found a better solution.

The property owners of a site south of Blackfoot on the Blackfoot River, just before it joins the Snake River, thought they had a pile of bricks from an old house that had been covered over with soil. We thought it was brick mine. Remarkably, the first settlers in what would become Blackfoot, built a brick home the same year, 1887, as Nels and Emma Just. Fred and Finnetta Garrett Stevens were longtime friends of the Justs. The Stevens home was the center of social activities for many years in Blackfoot, but was eventually abandoned and demolished, probably in the 1960s.

We got permission from the owners of the old Stevens place to mine the bricks. In the spring of 2019, about 20 members of the Reid side of the family began gathering bricks to replace damaged bricks in the Nels and Emma home (see picture).

Also, that spring, we removed the concrete sidewalk and regraded the slope of the lawn to move water away from the front of the house. We installed a new wooden boardwalk in keeping with the original design of the house. At the same time, we repaired some of the woodwork associated with the porch overhang.

Restoration projects often take longer than one thinks, and the Nels and Emma Just house is no exception. One more season of brick restoration will be needed to complete repairs to the damaged brick. Water seepage has softened and deteriorated even some of the inner walls of the house.

The Big House circa 1890.

The Big House circa 1890.  The brick mining crew: From top, Jess Reid, Fred Reid, Mark Pratt, Riggin Oleson, Debbie Reid-Oleson, Ira Oleson and Ruger Oleson; Ott Clark, Cole Clark, Howdy Clark, Bennett Davis, Clara Jensen, Lilly Davis, Gerry Becker, Wendy Pratt, and Harlie Oleson; Front: Ken Davis, Becky Davis, Nils Arnold, Megan Arnold, Zac Davis, Betsy Just, Ginger Reid, Leah Pratt and Seth Pratt.

The brick mining crew: From top, Jess Reid, Fred Reid, Mark Pratt, Riggin Oleson, Debbie Reid-Oleson, Ira Oleson and Ruger Oleson; Ott Clark, Cole Clark, Howdy Clark, Bennett Davis, Clara Jensen, Lilly Davis, Gerry Becker, Wendy Pratt, and Harlie Oleson; Front: Ken Davis, Becky Davis, Nils Arnold, Megan Arnold, Zac Davis, Betsy Just, Ginger Reid, Leah Pratt and Seth Pratt. Working on repairs to the front of the house.

Working on repairs to the front of the house.  The Big House as it looks today.

The Big House as it looks today.

Published on August 15, 2021 04:00

August 14, 2021

On the Witness Stand

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Do you remember how Emma and her father were involved in the Morrisite War of 1862. Those memories would come flooding back 17 years later when Robert Burton, the leader of the Mormon Militia, was put on trial for killings that occurred by his hand at Kington Fort. And his fate was decided by none other than Emma Thompson Just. Here’s how it was described in Letters of Long Ago.

________________

Blackfoot River, Idaho Territory

March 8, 1879

My Dear Father:

Here I have been so busy relating the details of family life that I have forgotten to mention the coming of the railroad. When we settled here, my husband always said there would be a railroad in ten years and his prophesy has been fulfilled in about seven as it reached the little burg of Blackfoot fifteen miles from us, sometime during December. Now, I've had a ride on the steam car. Would you believe it? And a visit to the city of Zion, the Zion that you brought my mother six thousand miles to see.

It is very changed since I saw it last in the sixties, but I took little note of its improvements for my mind was too much engrossed in the three-months-old baby in my arms and in the fact that I was the star witness in a murder trial. Can you imagine it Father? Your little Em taking such a part in the affairs of men.

I did not realize that my testimony was of such vital importance until it was all over, then the remark of the attorney was heard to the effect that I was the one witness they feared, but wait, I have not told you. One cold night in February a very unusual looking man appeared at the door and after making several inquiries, drew out the subpoena that called me as witness on the trial of Robert T. Burton being held on the charge of murder at Salt Lake.

In the years of our trials of homesteading, I have tried to forget the details most unpleasant of all our early experiences, the Mormon-Morrisite war. As I have grown more mature in judgment, I have realized that we poor misguided Morrisites were very much at fault, for in defying the sheriff 's posse as we did, we were really defying our government, for even though the posse was formed from the pillars of the Mormon church they were vested with the authority from Washington and we should not have tried to evade arrest. But this is all looking backward and I must proceed with my adventure.

Of course, first of all, I protested that I could not leave my family but Nels said it was my duty to go and he felt sure that my memory could not fail to bring the guilty to justice.

So I went but with a sinking heart! I regretted to leave my four boys that I had never been away from overnight; I regretted to take my tiny infant among people where might lurk the germs of every dread disease; and I regretted most of all, going among the Mormon people. They say a burnt child dreads the fire, so I guess a child that has been shot at cannot help fearing the hand that pulled the trigger. Every foot of the way we traveled I expected the train would be blown off the track, for it carried a number of witnesses, or I expected we would be burned in the court room, anything to wreak the Mormon vengeance as I had known it. But the Mormons are changed since those days, Father, they are a different people.

Still, frightened as I was, when I sat in the witness chair the old scenes came back to me as vividly as if they had occurred but yesterday.

I saw the hills blackened by the approaching enemy, heard the bugle call, our own beloved Morrisite call, that assembled us in the bowery and I knew again with what joy and trust I went forth expecting to be delivered by the hand of the Almighty. Then I saw a cannon ball come rushing through that humble gathering, fired by the waiting hordes on the hillside, and two of our trusting Morrisites lying dead in the bowery. Yes, I saw it all, father, and told them as only one who had seen could ever tell it, and the Mormons assembled there in the name of the law, began to fear me just as I had at first feared them.

I told them of the babe in its mother's arms falling to the ground at the boom of the first cannon and before the firing ceased, falling again when its second protector was killed. I told them of a woman, then in their city, who had lost the entire lower part of her face when the first ball was fired into that defenseless gathering of men, women and children.

I told them of the hoisting of the white flag by our terror stricken band and of the Mormon warriors, less heeding than any savage tribe of the wilderness, continuing to fire, killing four right under the flag of truce.

I told them how, on the second day, I had gone skipping across the public square in childish fearlessness with "cannons to the right of me and cannons to the left of me" to find my mother huddled in the little cellar under our house, white as in death, marking the number of cannons fired with a stick in the dirt. She had counted seventy-five that one day. Oh, Father, I can see her always, poor suffering creature, as she took me in her arms saying: "Thank God, my child, you are safe.” I looked at her in childish eagerness and dismay saying: "Why, mother, is your faith weakening? God will punish these foolish destroyers." But she only hugged me closer sobbing: "My child, bullets will kill"

I told them how after three days of almost continuous firing, they had surrounded us taking our men prisoners after having killed our beloved prophet, Joseph Morris. I told them how in the struggle that followed his fall, you stood by the lifeless form of the prophet and said to the Mormon that had once posed as our friend: ''You've killed him, now you better kill me." And of his attempt to shoot you had his gun not refused to obey his will. Then I told them of the gentle creature, Mrs. Bowman, who came forth during the struggle calling one of the leaders "A blood thirsty wretch." I told them how, before my childish eyes the fiend exclaimed: "No woman shall call me that and live." and suiting the action to the word, he shot her down.

And so after all these years, I was the instrument to avenge these wrongs to what mild extent it could ever be done. I was in the witness chair and my word would send to the gallows the murderer of that poor woman.

After questioning me sufficiently, they asked me to look around the court room and see if I recognized anyone. Did I? Well, I certainly did, just as I would recognize you, my own father, after all these years of separation. There he sat with his same flowing beard and gleaming eyes. His face had been the one thing that I could see distinctly all during my examination, as it had looked when I saw him years before and as it looked then. I think it had really served to bring the scenes before me more vividly as I recounted the details, particularly when it had come to the point of his pulling me roughly away from the body of Joseph Morris just after I had seen him slay Mrs. Bowman, but at this point my memory only served to set him free.

You father, no doubt would have remembered correctly, but the two leaders, Stoddard and Burton, had always been pointed out to me together and just as sometimes will occur, I had transposed the names, and the guilty man that I saw before me was the one I had always believed to be Stoddard. It so happened that the man Stoddard had been dead a good many years, so my testimony simply laid all the crimes on to the dead man and set free the criminal before me. So ignorant was I of courts and counsels, and so dependent upon my childish recollections, that it never occurred to me there was any chance for mistake until I had killed my own evidence.

Anyway, I was glad to be through with it and be free to come back to my little boys and my home. I had been gone for two weeks and had never heard a word for each day they expected I would be back. Each day Nels had sent a team to meet me only to find a letter saying the trial dragged on. I guess it seemed long to them but it was surely an eternity to me, and I have never smelled anything so sweet as the sage brush that crushed under the wheels that night when they brought me home. It was a mild spring night and had been raining so that everything was fresh and pure in such contrast from the coal smoke I had been obliged to breathe. I found everyone well though the children had been sick during my absence and we were a happy family indeed to be reunited. I think that home homecoming will always stand out as one of the happiest times of my life and in spite of my failure as a “star witness.” I hope this letter will carry to you a portion of the contentment that is in my heart.

Always the same,

Emma

_______________

Tomorrow, the story of Nels and Emma building their brick home in 1887. That home will be open for public tours that day. Click here for the details.

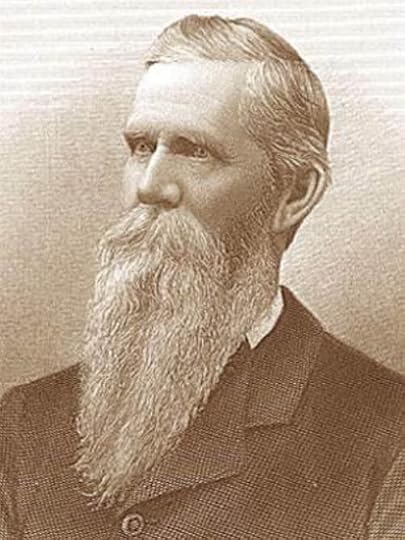

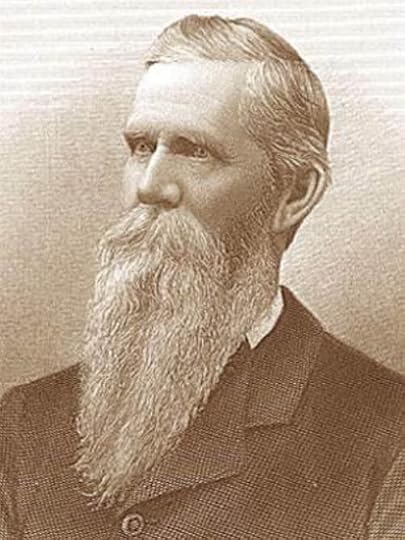

Robert T. Burton was acquitted of murder charges stemming from the Morrisite War.

Robert T. Burton was acquitted of murder charges stemming from the Morrisite War.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Do you remember how Emma and her father were involved in the Morrisite War of 1862. Those memories would come flooding back 17 years later when Robert Burton, the leader of the Mormon Militia, was put on trial for killings that occurred by his hand at Kington Fort. And his fate was decided by none other than Emma Thompson Just. Here’s how it was described in Letters of Long Ago.

________________

Blackfoot River, Idaho Territory

March 8, 1879

My Dear Father:

Here I have been so busy relating the details of family life that I have forgotten to mention the coming of the railroad. When we settled here, my husband always said there would be a railroad in ten years and his prophesy has been fulfilled in about seven as it reached the little burg of Blackfoot fifteen miles from us, sometime during December. Now, I've had a ride on the steam car. Would you believe it? And a visit to the city of Zion, the Zion that you brought my mother six thousand miles to see.

It is very changed since I saw it last in the sixties, but I took little note of its improvements for my mind was too much engrossed in the three-months-old baby in my arms and in the fact that I was the star witness in a murder trial. Can you imagine it Father? Your little Em taking such a part in the affairs of men.

I did not realize that my testimony was of such vital importance until it was all over, then the remark of the attorney was heard to the effect that I was the one witness they feared, but wait, I have not told you. One cold night in February a very unusual looking man appeared at the door and after making several inquiries, drew out the subpoena that called me as witness on the trial of Robert T. Burton being held on the charge of murder at Salt Lake.

In the years of our trials of homesteading, I have tried to forget the details most unpleasant of all our early experiences, the Mormon-Morrisite war. As I have grown more mature in judgment, I have realized that we poor misguided Morrisites were very much at fault, for in defying the sheriff 's posse as we did, we were really defying our government, for even though the posse was formed from the pillars of the Mormon church they were vested with the authority from Washington and we should not have tried to evade arrest. But this is all looking backward and I must proceed with my adventure.

Of course, first of all, I protested that I could not leave my family but Nels said it was my duty to go and he felt sure that my memory could not fail to bring the guilty to justice.

So I went but with a sinking heart! I regretted to leave my four boys that I had never been away from overnight; I regretted to take my tiny infant among people where might lurk the germs of every dread disease; and I regretted most of all, going among the Mormon people. They say a burnt child dreads the fire, so I guess a child that has been shot at cannot help fearing the hand that pulled the trigger. Every foot of the way we traveled I expected the train would be blown off the track, for it carried a number of witnesses, or I expected we would be burned in the court room, anything to wreak the Mormon vengeance as I had known it. But the Mormons are changed since those days, Father, they are a different people.

Still, frightened as I was, when I sat in the witness chair the old scenes came back to me as vividly as if they had occurred but yesterday.

I saw the hills blackened by the approaching enemy, heard the bugle call, our own beloved Morrisite call, that assembled us in the bowery and I knew again with what joy and trust I went forth expecting to be delivered by the hand of the Almighty. Then I saw a cannon ball come rushing through that humble gathering, fired by the waiting hordes on the hillside, and two of our trusting Morrisites lying dead in the bowery. Yes, I saw it all, father, and told them as only one who had seen could ever tell it, and the Mormons assembled there in the name of the law, began to fear me just as I had at first feared them.

I told them of the babe in its mother's arms falling to the ground at the boom of the first cannon and before the firing ceased, falling again when its second protector was killed. I told them of a woman, then in their city, who had lost the entire lower part of her face when the first ball was fired into that defenseless gathering of men, women and children.

I told them of the hoisting of the white flag by our terror stricken band and of the Mormon warriors, less heeding than any savage tribe of the wilderness, continuing to fire, killing four right under the flag of truce.

I told them how, on the second day, I had gone skipping across the public square in childish fearlessness with "cannons to the right of me and cannons to the left of me" to find my mother huddled in the little cellar under our house, white as in death, marking the number of cannons fired with a stick in the dirt. She had counted seventy-five that one day. Oh, Father, I can see her always, poor suffering creature, as she took me in her arms saying: "Thank God, my child, you are safe.” I looked at her in childish eagerness and dismay saying: "Why, mother, is your faith weakening? God will punish these foolish destroyers." But she only hugged me closer sobbing: "My child, bullets will kill"

I told them how after three days of almost continuous firing, they had surrounded us taking our men prisoners after having killed our beloved prophet, Joseph Morris. I told them how in the struggle that followed his fall, you stood by the lifeless form of the prophet and said to the Mormon that had once posed as our friend: ''You've killed him, now you better kill me." And of his attempt to shoot you had his gun not refused to obey his will. Then I told them of the gentle creature, Mrs. Bowman, who came forth during the struggle calling one of the leaders "A blood thirsty wretch." I told them how, before my childish eyes the fiend exclaimed: "No woman shall call me that and live." and suiting the action to the word, he shot her down.

And so after all these years, I was the instrument to avenge these wrongs to what mild extent it could ever be done. I was in the witness chair and my word would send to the gallows the murderer of that poor woman.

After questioning me sufficiently, they asked me to look around the court room and see if I recognized anyone. Did I? Well, I certainly did, just as I would recognize you, my own father, after all these years of separation. There he sat with his same flowing beard and gleaming eyes. His face had been the one thing that I could see distinctly all during my examination, as it had looked when I saw him years before and as it looked then. I think it had really served to bring the scenes before me more vividly as I recounted the details, particularly when it had come to the point of his pulling me roughly away from the body of Joseph Morris just after I had seen him slay Mrs. Bowman, but at this point my memory only served to set him free.

You father, no doubt would have remembered correctly, but the two leaders, Stoddard and Burton, had always been pointed out to me together and just as sometimes will occur, I had transposed the names, and the guilty man that I saw before me was the one I had always believed to be Stoddard. It so happened that the man Stoddard had been dead a good many years, so my testimony simply laid all the crimes on to the dead man and set free the criminal before me. So ignorant was I of courts and counsels, and so dependent upon my childish recollections, that it never occurred to me there was any chance for mistake until I had killed my own evidence.

Anyway, I was glad to be through with it and be free to come back to my little boys and my home. I had been gone for two weeks and had never heard a word for each day they expected I would be back. Each day Nels had sent a team to meet me only to find a letter saying the trial dragged on. I guess it seemed long to them but it was surely an eternity to me, and I have never smelled anything so sweet as the sage brush that crushed under the wheels that night when they brought me home. It was a mild spring night and had been raining so that everything was fresh and pure in such contrast from the coal smoke I had been obliged to breathe. I found everyone well though the children had been sick during my absence and we were a happy family indeed to be reunited. I think that home homecoming will always stand out as one of the happiest times of my life and in spite of my failure as a “star witness.” I hope this letter will carry to you a portion of the contentment that is in my heart.

Always the same,

Emma

_______________

Tomorrow, the story of Nels and Emma building their brick home in 1887. That home will be open for public tours that day. Click here for the details.

Robert T. Burton was acquitted of murder charges stemming from the Morrisite War.

Robert T. Burton was acquitted of murder charges stemming from the Morrisite War.

Published on August 14, 2021 04:00

August 13, 2021

The Timber Culture Act Brings Shade to the Valley

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

I am the beneficiary of bad science. A grove of cottonwoods five minute’s walk from where I grew up afforded me countless hours climbing trees. I spent much of my early summers pretending their limbs were the corridors of spaceships or the rugged route to the top of the Matterhorn.

Cottonwoods weren’t the only variety of tree there, but I can’t check on the species because the grove is gone now. Trees have a lifespan, and these started theirs in 1887. The last of their bones were shoved to the side to make way for crops a few years ago.

It was bad science that encouraged Congress to pass the Timber Culture Act in 1873. Those were the days when people believed that “rain will follow the plow.” They also believed planting trees would alter the climate and ecology of the Great Plains.

This belief was a perfect example of the common mistake of confusing cause with effect. Trees and plows did not bring milder weather and rain. They were the result of more favorable weather and rain.

The original Timber Culture Act called for participating farmers to plant 40 acres of trees on their 160 acres. However, in 1878, Congress reduced that requirement to 10 acres of trees.

Nels Just knew a good deal when he saw one. He applied for acreage under the act in 1887. On May 21, 1890, he received the first Timber Culture patent in Idaho after “proving up.” One had to prove that at least 675 trees were still standing. He, his wife Emma, their children, and hired men had planted hundreds of “slim switches,” as Agnes Just Reid wrote about the origin of the grove in which I whiled away hours. Hundreds of cottonwoods lined a half-mile ditch bank, leading to the family homestead, providing shade in a few years and eventually a stately entrance to the property.

Planting ten acres of trees did not bring rain to the Great Plains or to southeastern Idaho. Nels had to get the water to the trees through a series of canals and ditches he sometimes dug by hand and sometimes contracted for with diggers and blasters.

Many historians consider the Timber Culture Act a failure. Most trees planted in the Great Plains died from a lack of water. In the arid West, where irrigation was a part of farm life from the very beginning, the trees did better. In any case, Congress repealed the act in 1891.

The grove Nels and Emma planted provided shade for cattle and a pleasant place for the family to hold reunions, beginning in 1904. Over the years, the family started having reunions at homes and occasionally parks in Bingham and Bonneville counties. Finally, in 1999 we came back to the grove one last time for our get-together. Many of the old trees were dying off then; their purpose fulfilled long ago. This photo shows the grove Nels and Emma Just planted in fulfillment of their obligation under the Timber Culture Act. The date of the photo is unknown, but was probably in the early part of the 20th Century.

This photo shows the grove Nels and Emma Just planted in fulfillment of their obligation under the Timber Culture Act. The date of the photo is unknown, but was probably in the early part of the 20th Century.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

I am the beneficiary of bad science. A grove of cottonwoods five minute’s walk from where I grew up afforded me countless hours climbing trees. I spent much of my early summers pretending their limbs were the corridors of spaceships or the rugged route to the top of the Matterhorn.

Cottonwoods weren’t the only variety of tree there, but I can’t check on the species because the grove is gone now. Trees have a lifespan, and these started theirs in 1887. The last of their bones were shoved to the side to make way for crops a few years ago.

It was bad science that encouraged Congress to pass the Timber Culture Act in 1873. Those were the days when people believed that “rain will follow the plow.” They also believed planting trees would alter the climate and ecology of the Great Plains.

This belief was a perfect example of the common mistake of confusing cause with effect. Trees and plows did not bring milder weather and rain. They were the result of more favorable weather and rain.

The original Timber Culture Act called for participating farmers to plant 40 acres of trees on their 160 acres. However, in 1878, Congress reduced that requirement to 10 acres of trees.

Nels Just knew a good deal when he saw one. He applied for acreage under the act in 1887. On May 21, 1890, he received the first Timber Culture patent in Idaho after “proving up.” One had to prove that at least 675 trees were still standing. He, his wife Emma, their children, and hired men had planted hundreds of “slim switches,” as Agnes Just Reid wrote about the origin of the grove in which I whiled away hours. Hundreds of cottonwoods lined a half-mile ditch bank, leading to the family homestead, providing shade in a few years and eventually a stately entrance to the property.

Planting ten acres of trees did not bring rain to the Great Plains or to southeastern Idaho. Nels had to get the water to the trees through a series of canals and ditches he sometimes dug by hand and sometimes contracted for with diggers and blasters.

Many historians consider the Timber Culture Act a failure. Most trees planted in the Great Plains died from a lack of water. In the arid West, where irrigation was a part of farm life from the very beginning, the trees did better. In any case, Congress repealed the act in 1891.

The grove Nels and Emma planted provided shade for cattle and a pleasant place for the family to hold reunions, beginning in 1904. Over the years, the family started having reunions at homes and occasionally parks in Bingham and Bonneville counties. Finally, in 1999 we came back to the grove one last time for our get-together. Many of the old trees were dying off then; their purpose fulfilled long ago.

This photo shows the grove Nels and Emma Just planted in fulfillment of their obligation under the Timber Culture Act. The date of the photo is unknown, but was probably in the early part of the 20th Century.

This photo shows the grove Nels and Emma Just planted in fulfillment of their obligation under the Timber Culture Act. The date of the photo is unknown, but was probably in the early part of the 20th Century.

Published on August 13, 2021 04:00

August 12, 2021

I Almost Drowned

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

The title of this post applies to every descendant of Nels and Emma Just. Taken in whole from Letters of Long Ago, by Agnes Just Reid, this one gives us a look at the occasional terror of pioneer life and it illustrates the brutal honesty of Emma Just.

_____________

Blackfoot River, Idaho Territory

September 14, 1877

Dear Father:

Tell me, Father, is it a mark of insanity for one to wish to take his own life? My husband says it is, but I insist that it is perfectly sensible, so we shall expect you to cast the deciding vote. I have been on the point of killing my children and myself that we might be spared a more terrible fate, and before you agree with Nels that my mind is becoming unbalanced, I want you to know how logical it all appears to me. I think I must have mentioned our fear of an Indian uprising when I wrote last. Well, with the coming of spring our worst fears were confirmed and the summer has been a season of terror. I often wonder if some of the newspaper reports reach even to where you are and if you picture us, your very own, being burned to death in the little cabin as you read of a lonely habitation being destroyed.

The Nez Perce tribes to the north of us with Chief Joseph as leader have been doing depredations of all descriptions, and each time we hear, coming nearer and nearer to us. Albert Lyon, whom you remember from Soda Springs days, was captured by them out in the Birch Creek country, which is only a hundred miles from here, and he barely escaped with his life. He was freighting with Green's outfit and when the Indians came upon them they took possession of the wagons and drivers but assured them they meant no harm, just wanted to detain them so that they could not give the alarm. After being held several days, Lyon managed to give them the slip by dropping into the wash then following down the bed of the stream, and finally reached a cabin in time to save himself from a death of starvation. His fellow travelers were all killed and the wagons burned before the savages moved camp. Some, who wish to promote a Christian attitude toward the red man, insist that it was because Lyon betrayed the trust, but it seems to me he simply saved his own scalp. (Editor's Note: A recent Facebook post included copies of a letter Green wrote about the incident)

But to return to my own story. Nels has been putting up hay at Fort Hall the greater part of the summer, often staying away overnight. Brooding as I did, I could not sleep when alone and I dared not make a light for it would only serve as a target for some stealthy redskin, so all night my imagination ran riot. I would see through the windows bushes and stumps that were familiar to me by daylight, but by night they took the form of a crouching savage, of which there were a million more just behind the shadows, surrounding the cabin. Night after night I spent in that way, and day after day I milked the cows and made the butter with my head hidden away in an old slat sunbonnet, lest the children might discover my changing expressions.

When Nels came home he brought papers with vivid descriptions of the path of terror the Indians were leaving in their wake and I felt positive that it was only a matter of time until they would join our own tribes here and complete the destruction of the white race in southern Idaho.

The fall days began to come on when a heavy haze hung over everything, sometimes poetically called "Indian Summer," but that one word has taken the poetry out of everything for me this summer. Nels had not been home for several days and the desperation of continued loneliness was upon me, when toward evening the children came rushing in from their play to say there was a fire on the hill south of us. I tried to assure them that it was just something that looked like a fire, but I knew too well that it was a fire, a signal fire, that one band makes to let the others be in readiness for a celebration. That night I was almost frantic and while the children slept I made up my mind what I must do to save them. I resolved never to let them be mutilated by savage fingers before my very eyes. No, no! I had read of such cases and mine should never suffer so, while I was held captive perhaps to bear other children by the savage brute that had murdered mine.

I had given existence to mine, now at such a crisis it was my right to take it from them. I would drown the older ones, one by one, then take the baby in my arms and go in beside them. To try to hide would be useless. The baby would cry and we would be found and tortured more for trying to deceive them, so with the first intimation of their approach we would find our only safety in the river so near at hand. I felt perfectly sure that the end was near, the signal fire had been the culminating event in the tragedy, but after the children had eaten the breakfast which I was unable to taste, I went on with the milking, through force of habit, I suppose. I'd milk a cow, then go up the hill to strain my eyes for the coming of the enemy. At last I saw what I expected to see, a dust, or was it a smoke? In either case it meant the same. It was just at the point where the Shoemakers live and if it were dust, the Indians were reaching there; if smoke, they had been there and were leaving. There was no time to lose.

I called my poor terror-stricken babies around me and told them we must all drown together. If the older ones held any differences of opinion, they knew their mother too well to express them, so with a board in my hand, on which was to be scribbled an explanation to Nels, we started to the river.

Like Lot's wife I turned once to look back, and the cause of the dust I had seen was in plain view-my husband. I have heard of the interventions of Providence and this must be an illustration, for in ten minutes more he would have been a man without a family. He called me crazy and said he would never trust me alone again and I am not sure that I blame him. The solitude must be getting on my nerves. I need a neighbor. I need companionship. I never seem to feel lonesome for I am always busy, but I have had too much of my own society.

__________________

If you’re familiar with the circumstances of the Nez Perce War you know there was another side to the story, and that Joseph (see photo) was actually a peace thirsty chief. But where Emma was sitting, he scared her nearly to death.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

The title of this post applies to every descendant of Nels and Emma Just. Taken in whole from Letters of Long Ago, by Agnes Just Reid, this one gives us a look at the occasional terror of pioneer life and it illustrates the brutal honesty of Emma Just.

_____________

Blackfoot River, Idaho Territory

September 14, 1877

Dear Father:

Tell me, Father, is it a mark of insanity for one to wish to take his own life? My husband says it is, but I insist that it is perfectly sensible, so we shall expect you to cast the deciding vote. I have been on the point of killing my children and myself that we might be spared a more terrible fate, and before you agree with Nels that my mind is becoming unbalanced, I want you to know how logical it all appears to me. I think I must have mentioned our fear of an Indian uprising when I wrote last. Well, with the coming of spring our worst fears were confirmed and the summer has been a season of terror. I often wonder if some of the newspaper reports reach even to where you are and if you picture us, your very own, being burned to death in the little cabin as you read of a lonely habitation being destroyed.

The Nez Perce tribes to the north of us with Chief Joseph as leader have been doing depredations of all descriptions, and each time we hear, coming nearer and nearer to us. Albert Lyon, whom you remember from Soda Springs days, was captured by them out in the Birch Creek country, which is only a hundred miles from here, and he barely escaped with his life. He was freighting with Green's outfit and when the Indians came upon them they took possession of the wagons and drivers but assured them they meant no harm, just wanted to detain them so that they could not give the alarm. After being held several days, Lyon managed to give them the slip by dropping into the wash then following down the bed of the stream, and finally reached a cabin in time to save himself from a death of starvation. His fellow travelers were all killed and the wagons burned before the savages moved camp. Some, who wish to promote a Christian attitude toward the red man, insist that it was because Lyon betrayed the trust, but it seems to me he simply saved his own scalp. (Editor's Note: A recent Facebook post included copies of a letter Green wrote about the incident)

But to return to my own story. Nels has been putting up hay at Fort Hall the greater part of the summer, often staying away overnight. Brooding as I did, I could not sleep when alone and I dared not make a light for it would only serve as a target for some stealthy redskin, so all night my imagination ran riot. I would see through the windows bushes and stumps that were familiar to me by daylight, but by night they took the form of a crouching savage, of which there were a million more just behind the shadows, surrounding the cabin. Night after night I spent in that way, and day after day I milked the cows and made the butter with my head hidden away in an old slat sunbonnet, lest the children might discover my changing expressions.

When Nels came home he brought papers with vivid descriptions of the path of terror the Indians were leaving in their wake and I felt positive that it was only a matter of time until they would join our own tribes here and complete the destruction of the white race in southern Idaho.

The fall days began to come on when a heavy haze hung over everything, sometimes poetically called "Indian Summer," but that one word has taken the poetry out of everything for me this summer. Nels had not been home for several days and the desperation of continued loneliness was upon me, when toward evening the children came rushing in from their play to say there was a fire on the hill south of us. I tried to assure them that it was just something that looked like a fire, but I knew too well that it was a fire, a signal fire, that one band makes to let the others be in readiness for a celebration. That night I was almost frantic and while the children slept I made up my mind what I must do to save them. I resolved never to let them be mutilated by savage fingers before my very eyes. No, no! I had read of such cases and mine should never suffer so, while I was held captive perhaps to bear other children by the savage brute that had murdered mine.

I had given existence to mine, now at such a crisis it was my right to take it from them. I would drown the older ones, one by one, then take the baby in my arms and go in beside them. To try to hide would be useless. The baby would cry and we would be found and tortured more for trying to deceive them, so with the first intimation of their approach we would find our only safety in the river so near at hand. I felt perfectly sure that the end was near, the signal fire had been the culminating event in the tragedy, but after the children had eaten the breakfast which I was unable to taste, I went on with the milking, through force of habit, I suppose. I'd milk a cow, then go up the hill to strain my eyes for the coming of the enemy. At last I saw what I expected to see, a dust, or was it a smoke? In either case it meant the same. It was just at the point where the Shoemakers live and if it were dust, the Indians were reaching there; if smoke, they had been there and were leaving. There was no time to lose.

I called my poor terror-stricken babies around me and told them we must all drown together. If the older ones held any differences of opinion, they knew their mother too well to express them, so with a board in my hand, on which was to be scribbled an explanation to Nels, we started to the river.

Like Lot's wife I turned once to look back, and the cause of the dust I had seen was in plain view-my husband. I have heard of the interventions of Providence and this must be an illustration, for in ten minutes more he would have been a man without a family. He called me crazy and said he would never trust me alone again and I am not sure that I blame him. The solitude must be getting on my nerves. I need a neighbor. I need companionship. I never seem to feel lonesome for I am always busy, but I have had too much of my own society.

__________________

If you’re familiar with the circumstances of the Nez Perce War you know there was another side to the story, and that Joseph (see photo) was actually a peace thirsty chief. But where Emma was sitting, he scared her nearly to death.

Published on August 12, 2021 04:00

August 11, 2021

Buckskin and Butter

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

For this story I’m going to include a piece I’ve posted before but add some detail about several ways Nels and Emma Just became entrepreneur pioneers to survive and thrive in the early days of Idaho Territory. This blog post is taken partly from the Book, Letters of Long Ago , written by Emma's daughter, Agnes Just Reid.

“The winter was uneventful, but the spring, the spring has been wonderful! We have had guests, distinguished guests from the big world itself. You see there is a land to the northeast of us, perhaps a hundred miles, that is considered marvelous for its scenic possibilities and the government is sending a party of surveyors, chemists, etc., to pass judgment with a view to setting it aside for a national park. Well, this party happened to stop at our little cabin. There were representatives from all of the big eastern colleges, and then besides, there were the Moran brothers. I think you must have heard of Thomas Moran even as far away as England, for he is a wonderful nature artist. And his brother John is what I have heard you speak of as a "book maker." He writes magazine articles.

“And these two remarkable men were interested in us and in our way of living. Think of it, Father! I took them into the cellar where I had been churning to give them a drink of fresh buttermilk and while they drank and enjoyed it, I was smoothing the rolls of butter with my cedar paddle that Nels had whittled out for me with his pocket knife. I noticed the artist man paying special attention to the process and finally he ventured rather apologetically: "Mrs. Just, would you mind telling me what you varnish your rolls of butter with that gives them such a glossy appearance?" I thought the man was making fun of me, or sport of me as you would express it, but I looked into his face and saw that it was all candor. That is one of the happiest experiences of my life for that man who knows everything to be ignorant in the lines that I know so well. I tried to make him understand that the smooth paddle and the fresh butter were all sufficient but I think he is still rather bewildered. And do you know, since that day, the art of butter making has taken on anew dignity. I always did like to do it, but now my cedar paddle keeps singing to me with every stroke, "Even Thomas Moran cannot do this, Thomas Moran cannot do this," and before I know it the butter is all finished and I am ready to sing a different song to the washboard.”

Thomas Moran, of course, was a member of the Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871. The expedition was camped nearby along the Blackfoot River on their way to Yellowstone, and several members visited the Just cabin. Emma and Nels sold them some of their handiwork. Some leather gloves and britches, such as the ones worn by Hayden Expedition members in the William Henry Jackson photo below. Scroll down past the picture to read more about the industriousness of Nels and Emma Just.

A Cottage Industry Emma Just made a little bread. In 1869, shortly before marrying Nels, Emma was baking 35 loves a day for the men stationed at Fort Hall, which was still under construction. She would work from four in the morning until ten at night, making sure each man had his daily loaf. Her stove was small and would bake only four loaves at a time. When each loaf was ready to go, she put it in a sack bearing the name of the soldier for whom it was baked.

A Cottage Industry Emma Just made a little bread. In 1869, shortly before marrying Nels, Emma was baking 35 loves a day for the men stationed at Fort Hall, which was still under construction. She would work from four in the morning until ten at night, making sure each man had his daily loaf. Her stove was small and would bake only four loaves at a time. When each loaf was ready to go, she put it in a sack bearing the name of the soldier for whom it was baked.

In a time when it took a full day to freight anything 15 miles, locally-made items were a bargain. Nels, who was a freighter on and off for decades, knew this as well as anyone. He and Emma, were an industrious pair, rendering barrels of fat from slaughtered livestock to make tallow for candles, making butter in bulk, and furnishing hard working men with clothes to match their needs.

In 1878 Nels hauled 400 pounds of rendered fat to Corrinne, Utah Territory, hoping to get a nice price out of it. When offered just 4 cents a pound, he hauled the load all the way back—121 miles as the crow flies—to his home along the Blackfoot River in Idaho Territory. He and Emma proceeded to make soap and candles from the fat. They probably sold those items to the Anderson brothers, who had a store in Eagle Rock that carried their name.

We know the Anderson Brothers store sold buckskin gloves made by Emma and Nels. The Justs charged the brothers 75 cents a pair for the gloves, and $3 a pair for buckskin britches.

Tomorrow I'll tell you about the first Timber Culture Act patent issued in Idaho.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

For this story I’m going to include a piece I’ve posted before but add some detail about several ways Nels and Emma Just became entrepreneur pioneers to survive and thrive in the early days of Idaho Territory. This blog post is taken partly from the Book, Letters of Long Ago , written by Emma's daughter, Agnes Just Reid.

“The winter was uneventful, but the spring, the spring has been wonderful! We have had guests, distinguished guests from the big world itself. You see there is a land to the northeast of us, perhaps a hundred miles, that is considered marvelous for its scenic possibilities and the government is sending a party of surveyors, chemists, etc., to pass judgment with a view to setting it aside for a national park. Well, this party happened to stop at our little cabin. There were representatives from all of the big eastern colleges, and then besides, there were the Moran brothers. I think you must have heard of Thomas Moran even as far away as England, for he is a wonderful nature artist. And his brother John is what I have heard you speak of as a "book maker." He writes magazine articles.

“And these two remarkable men were interested in us and in our way of living. Think of it, Father! I took them into the cellar where I had been churning to give them a drink of fresh buttermilk and while they drank and enjoyed it, I was smoothing the rolls of butter with my cedar paddle that Nels had whittled out for me with his pocket knife. I noticed the artist man paying special attention to the process and finally he ventured rather apologetically: "Mrs. Just, would you mind telling me what you varnish your rolls of butter with that gives them such a glossy appearance?" I thought the man was making fun of me, or sport of me as you would express it, but I looked into his face and saw that it was all candor. That is one of the happiest experiences of my life for that man who knows everything to be ignorant in the lines that I know so well. I tried to make him understand that the smooth paddle and the fresh butter were all sufficient but I think he is still rather bewildered. And do you know, since that day, the art of butter making has taken on anew dignity. I always did like to do it, but now my cedar paddle keeps singing to me with every stroke, "Even Thomas Moran cannot do this, Thomas Moran cannot do this," and before I know it the butter is all finished and I am ready to sing a different song to the washboard.”

Thomas Moran, of course, was a member of the Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871. The expedition was camped nearby along the Blackfoot River on their way to Yellowstone, and several members visited the Just cabin. Emma and Nels sold them some of their handiwork. Some leather gloves and britches, such as the ones worn by Hayden Expedition members in the William Henry Jackson photo below. Scroll down past the picture to read more about the industriousness of Nels and Emma Just.

A Cottage Industry Emma Just made a little bread. In 1869, shortly before marrying Nels, Emma was baking 35 loves a day for the men stationed at Fort Hall, which was still under construction. She would work from four in the morning until ten at night, making sure each man had his daily loaf. Her stove was small and would bake only four loaves at a time. When each loaf was ready to go, she put it in a sack bearing the name of the soldier for whom it was baked.

A Cottage Industry Emma Just made a little bread. In 1869, shortly before marrying Nels, Emma was baking 35 loves a day for the men stationed at Fort Hall, which was still under construction. She would work from four in the morning until ten at night, making sure each man had his daily loaf. Her stove was small and would bake only four loaves at a time. When each loaf was ready to go, she put it in a sack bearing the name of the soldier for whom it was baked.In a time when it took a full day to freight anything 15 miles, locally-made items were a bargain. Nels, who was a freighter on and off for decades, knew this as well as anyone. He and Emma, were an industrious pair, rendering barrels of fat from slaughtered livestock to make tallow for candles, making butter in bulk, and furnishing hard working men with clothes to match their needs.

In 1878 Nels hauled 400 pounds of rendered fat to Corrinne, Utah Territory, hoping to get a nice price out of it. When offered just 4 cents a pound, he hauled the load all the way back—121 miles as the crow flies—to his home along the Blackfoot River in Idaho Territory. He and Emma proceeded to make soap and candles from the fat. They probably sold those items to the Anderson brothers, who had a store in Eagle Rock that carried their name.

We know the Anderson Brothers store sold buckskin gloves made by Emma and Nels. The Justs charged the brothers 75 cents a pair for the gloves, and $3 a pair for buckskin britches.

Tomorrow I'll tell you about the first Timber Culture Act patent issued in Idaho.

Published on August 11, 2021 04:00

August 10, 2021

Homesteading on Idaho's Blackfoot River

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August. This blog is wholly taken from the Book, Letters of Long Ago , written by Emma Just's daughter, Agnes Just Reid.

Blackfoot River, Idaho Territory

April 11, 1871

My Dear Father: