Rick Just's Blog, page 120

July 18, 2021

The Great Ice Fire of 1929

In a post earlier this month, I talked about the pea picker strike of 1935 in Teton County. There’s a quirky little story that I discovered in researching that. Let’s call it The Great Ice Fire of 1929.

Peas are highly perishable. They need to be harvested quickly and refrigerated so that they don’t lose their sugar content. Shipping the pea crop from Teton County necessitated ample supplies of ice in the days before refrigerated railway cars were available. Local entrepreneurs began farming ice in the winter and storing it in an insulated shelter during the hot days of the summer for use for shipping peas in August.

How do you farm ice? Well, you can gather it in the wild by cutting blocks of ice from a river or lake, or you can dig a pit and fill it with water, letting winter do its work.

The Hillman brothers had gone the pit route in 1929, covering the ice-filled hole with generous quantities of straw. Pea harvest was about to begin that August. Unfortunately, some careless smoker tossed a butt onto the covered pit, igniting the straw. The resulting fire burned about 500 tons of ice, worth about $1500.

Published on July 18, 2021 04:00

July 17, 2021

The Desmet Fires

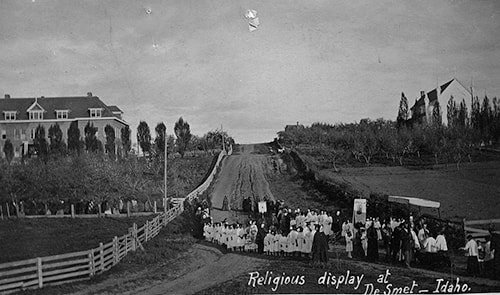

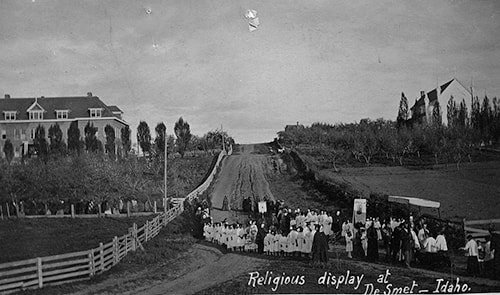

In this postcard image taken some time before 1939, the Mary Immaculate School in Desmet is on the left, while the Gothic style Sacred Heart church is on the right. Both structures would end in flames, though 72 years apart.

The first to burn was the Sacred Heart church of the Jesuit mission on April 2, 1939. Archbishop Seghers, the first bishop of the Pacific northwest and Alaska, had placed the cornerstone of the church in 1881. A legend about the fate of the church is told at the Museum of North Idaho. An elderly Coeur d’Alene named Agatha Timothy is said to have loved the church so much that she vowed to “take it to heaven with her.” The day after she died a furnace explosion caused the fire that destroyed the building.

The nearby Mary Immaculate School, run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence was built in 1892 as a boarding school for girls. It was one of many built across the West, with, perhaps, the best of intentions. Often the schools served to educate, but also separate Native American students from their families. The school closed in 1974. It burned on Feb. 3, 2011. The landmark building on the hill above DeSmet was on the National Register of Historic Places. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe is planning the Sister’s Building Park and Gathering Area on the site. It will include interpretive panels telling the history of the area.

The first to burn was the Sacred Heart church of the Jesuit mission on April 2, 1939. Archbishop Seghers, the first bishop of the Pacific northwest and Alaska, had placed the cornerstone of the church in 1881. A legend about the fate of the church is told at the Museum of North Idaho. An elderly Coeur d’Alene named Agatha Timothy is said to have loved the church so much that she vowed to “take it to heaven with her.” The day after she died a furnace explosion caused the fire that destroyed the building.

The nearby Mary Immaculate School, run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence was built in 1892 as a boarding school for girls. It was one of many built across the West, with, perhaps, the best of intentions. Often the schools served to educate, but also separate Native American students from their families. The school closed in 1974. It burned on Feb. 3, 2011. The landmark building on the hill above DeSmet was on the National Register of Historic Places. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe is planning the Sister’s Building Park and Gathering Area on the site. It will include interpretive panels telling the history of the area.

Published on July 17, 2021 04:00

July 16, 2021

Lalia Boone

When it comes to Idaho place names, Lalia Boone was the acknowledged expert. Her book

Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary

is indispensable for Idaho historians.

You might think that Boone came from an old Idaho family and grew up hearing Idaho place names over the dinner table. If you thought that, you’d be way off.

Boone was born in 1907, in Tehuacana, Texas. She graduated from Westminster Junior College there in 1925. Boone taught in county schools in Texas for years, becoming a principal in 1944. A lifelong educator, she never stopped learning, getting a BA in English in 1938 from East Texas State College, and a masters in medieval literature and linguistics from the University of Oklahoma in 1947. Boone was a trailblazer in 1951 when she became the first woman to get a doctorate at the University of Florida.

In 1965 Boone took a job as professor of English at the University of Idaho. She taught there until her retirement in 1973.

Lalia Boone became interested in Idaho place names because many of them seemed strange to her southern ears. Her curiosity led her to found the Idaho Place Names Project in 1966. The project received early funding from the National Science Foundation, and it became one of two pilot projects nationwide in the American Name Society Place Name Survey.

She and her students spent years interviewing locals across the state for the project, the archives of which are housed at the University of Idaho. Cort Conley, who ran the University of Idaho Press at the time, said that Boone “Commandeered derivations from her students the way wool socks snag wood ticks.”

You might think that Boone came from an old Idaho family and grew up hearing Idaho place names over the dinner table. If you thought that, you’d be way off.

Boone was born in 1907, in Tehuacana, Texas. She graduated from Westminster Junior College there in 1925. Boone taught in county schools in Texas for years, becoming a principal in 1944. A lifelong educator, she never stopped learning, getting a BA in English in 1938 from East Texas State College, and a masters in medieval literature and linguistics from the University of Oklahoma in 1947. Boone was a trailblazer in 1951 when she became the first woman to get a doctorate at the University of Florida.

In 1965 Boone took a job as professor of English at the University of Idaho. She taught there until her retirement in 1973.

Lalia Boone became interested in Idaho place names because many of them seemed strange to her southern ears. Her curiosity led her to found the Idaho Place Names Project in 1966. The project received early funding from the National Science Foundation, and it became one of two pilot projects nationwide in the American Name Society Place Name Survey.

She and her students spent years interviewing locals across the state for the project, the archives of which are housed at the University of Idaho. Cort Conley, who ran the University of Idaho Press at the time, said that Boone “Commandeered derivations from her students the way wool socks snag wood ticks.”

Published on July 16, 2021 04:00

July 15, 2021

The Coeur d'Alene USO Fire

In 1935, Coeur d’Alene city leaders began talking about the need for a civic auditorium. Money is always tight for such aspirational projects, but the mission of the Works Project Administration (WPA), the largest agency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal program, was to create jobs. Building the city an auditorium would generate jobs during construction, and serve the community well into the future.

With the WPA putting up 65 percent of construction costs and providing the labor, work was begun on the auditorium in 1936. It hosted some events before its completion but wasn’t fully open until 1938.

It became the USO-Civic Auditorium in 1942 when military officials and USO personnel approached the city about providing off-base entertainment services for the “boots” at the new Farragut Naval Training Station (FNTS), and smaller military facilities in the area. The United Service Organization (USO), a non-profit dedicated to providing entertainment to US troops, took over the operation of the building with the understanding that it would be returned to the City of Coeur d’Alene when it was no longer needed as a USO.

The beautiful log building (pictured) was in a city park adjacent to Lake Coeur d’Alene. Service members could enjoy the beach, weather permitting, and take part in dances, play ping pong, see movies, and just enjoy a little free time. More than 2,000 sailors a day visited the USO during its peak.

On October 9, 1945, a 17-year-old recruit from Farragut boarded a bus with fellow boots for a little R and R in town. William Barna, from New Jersey, had been at FNTS only three weeks. A 6th-grade drop-out, Barna had no explanation for his actions that night. What he did was methodically tear stuffing from the upholstery in three cars in preparation for lighting them on fire. Then, he went into the USO and surreptitiously unlocked a back door so he could get back in after the building was closed for the night. When the patrons and staff were gone, Barna entered through the door and began pulling down curtains. He piled them on the floor along with wads of paper, and set it all on fire.

The three cars and the log USO-Civic Auditorium went up in flames, a devastating loss to the community.

Barna was convicted of second-degree arson and given 5 to 10 years in the state prison. He served only four years before being released in 1949.

Much of the material for this post was taken from an article written by Don Pischner in the summer 2012 edition of the Museum of Northern Idaho’s newsletter.

The USO before the fire.

The USO before the fire.

With the WPA putting up 65 percent of construction costs and providing the labor, work was begun on the auditorium in 1936. It hosted some events before its completion but wasn’t fully open until 1938.

It became the USO-Civic Auditorium in 1942 when military officials and USO personnel approached the city about providing off-base entertainment services for the “boots” at the new Farragut Naval Training Station (FNTS), and smaller military facilities in the area. The United Service Organization (USO), a non-profit dedicated to providing entertainment to US troops, took over the operation of the building with the understanding that it would be returned to the City of Coeur d’Alene when it was no longer needed as a USO.

The beautiful log building (pictured) was in a city park adjacent to Lake Coeur d’Alene. Service members could enjoy the beach, weather permitting, and take part in dances, play ping pong, see movies, and just enjoy a little free time. More than 2,000 sailors a day visited the USO during its peak.

On October 9, 1945, a 17-year-old recruit from Farragut boarded a bus with fellow boots for a little R and R in town. William Barna, from New Jersey, had been at FNTS only three weeks. A 6th-grade drop-out, Barna had no explanation for his actions that night. What he did was methodically tear stuffing from the upholstery in three cars in preparation for lighting them on fire. Then, he went into the USO and surreptitiously unlocked a back door so he could get back in after the building was closed for the night. When the patrons and staff were gone, Barna entered through the door and began pulling down curtains. He piled them on the floor along with wads of paper, and set it all on fire.

The three cars and the log USO-Civic Auditorium went up in flames, a devastating loss to the community.

Barna was convicted of second-degree arson and given 5 to 10 years in the state prison. He served only four years before being released in 1949.

Much of the material for this post was taken from an article written by Don Pischner in the summer 2012 edition of the Museum of Northern Idaho’s newsletter.

The USO before the fire.

The USO before the fire.

Published on July 15, 2021 04:00

July 14, 2021

Early Irrigation in Bingham County

People who move into the state and even many Idaho natives often know little about how important irrigation is. Without it, the southern part of the state would be what it had been for millennia, a desert.

This came to mind while I was doing some research on Idaho pioneer Presto Burrell for a family magazine I edit. My family isn’t related to Burrell, but he was important enough in our history that our magazine is called Presto Press, named after him, as was the community of ranches where I grew up, near Blackfoot. It is called Lower Presto.

The April 29, 1910, issue of the Idaho Republican, a Blackfoot newspaper had the following under the heading, Blackfoot A Historic Spot.

“The newspapers of the state are giving Blackfoot some publicity on account of the fact that this is the fortieth anniversary of the building of the first irrigating ditches in the upper Snake River Valley. Now, within four decades we have more mileage of canals and more acreage of irrigable lands than any other county in the United States, and the marvelous development of forty years, for things move rapidly now.

“It was in 1870 that Fred S. Stevens, Presto Burrell, and Henry Dunn made their first ditches to convey water out upon the soil and they are all living and making money out of the products being raised each year by the same ditches on the same lands. Their work was experimental and the present prosperous population is reaping the benefit of the demonstrations they made.”

My great grandparents, Nels and Emma Just moved to the valley in which Presto Burrell settled, just a few months after he did. In later years Emma would be the postmistress for the area and Nels would suggest the name Presto for the post office. That’s how the area got its name, something Mr. Burrell was never comfortable with.

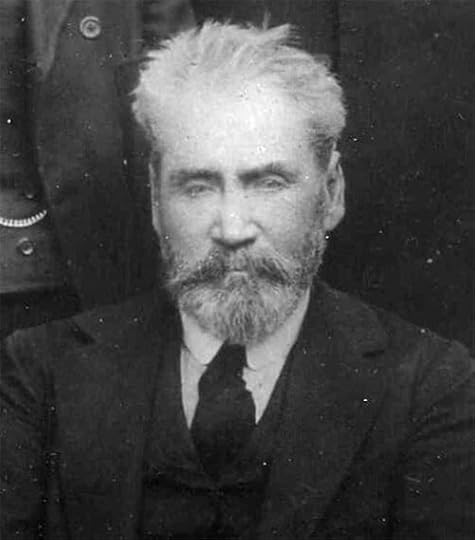

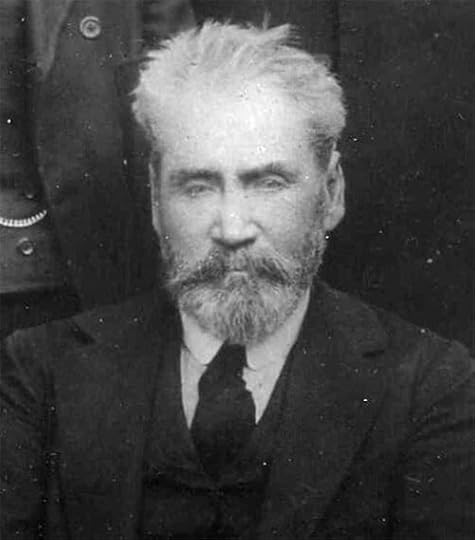

So, I grew up in that little valley where one of the first irrigation ditches in Bingham County was dug by Presto Burrell (photo). Family members—cousins—still farm and ranch in the valley. You’re likely to see a few more stories about early irrigation in future posts.

This came to mind while I was doing some research on Idaho pioneer Presto Burrell for a family magazine I edit. My family isn’t related to Burrell, but he was important enough in our history that our magazine is called Presto Press, named after him, as was the community of ranches where I grew up, near Blackfoot. It is called Lower Presto.

The April 29, 1910, issue of the Idaho Republican, a Blackfoot newspaper had the following under the heading, Blackfoot A Historic Spot.

“The newspapers of the state are giving Blackfoot some publicity on account of the fact that this is the fortieth anniversary of the building of the first irrigating ditches in the upper Snake River Valley. Now, within four decades we have more mileage of canals and more acreage of irrigable lands than any other county in the United States, and the marvelous development of forty years, for things move rapidly now.

“It was in 1870 that Fred S. Stevens, Presto Burrell, and Henry Dunn made their first ditches to convey water out upon the soil and they are all living and making money out of the products being raised each year by the same ditches on the same lands. Their work was experimental and the present prosperous population is reaping the benefit of the demonstrations they made.”

My great grandparents, Nels and Emma Just moved to the valley in which Presto Burrell settled, just a few months after he did. In later years Emma would be the postmistress for the area and Nels would suggest the name Presto for the post office. That’s how the area got its name, something Mr. Burrell was never comfortable with.

So, I grew up in that little valley where one of the first irrigation ditches in Bingham County was dug by Presto Burrell (photo). Family members—cousins—still farm and ranch in the valley. You’re likely to see a few more stories about early irrigation in future posts.

Published on July 14, 2021 04:00

July 13, 2021

Beyond Hope

Residents of Hope, Idaho, take note. Here’s another of the endless opportunities to play on the name of your town by declaring that something is beyond Hope. In this case, someONE was beyond.

Hope was named in 1882 for a Doctor Hope who was a veterinarian with the Northern Pacific Railroad. But this is a beyond hope story.

It seems that a barber showed up in Sandpoint and worked in a barbershop there for a few days. He was reportedly a handsome, clean-shaven man with graying auburn hair who might have come from Kansas City.

None of that would have made the papers. His last act, did. The Spokesman Review reported that “he came to Hope Thursday evening showing signs of having been under the influence of liquor. During the evening, he flourished a razor in a hotel office and told the night clerk he would prove to the people present that he was a nervy man by cutting his own throat.”

The clerk talked quietly to the man and persuaded him to put the razor away.

But early the next morning the man was back. Quoting the paper, “at 5:30 he walked out onto the platform and five minutes later drew the razor from his breast pocket with his right hand, pulled down his shirt collar with the left hand, threw his head back and a little to one side, then drew the blade across his jugular and cut an awful gash in his throat.”

After that the report gets graphic. Suffice to say the man spent a minute or two dying. No clue about who he was could be found among his effects.

The paper dutifully reported that the coroner ruled the death a suicide.

Hope was named in 1882 for a Doctor Hope who was a veterinarian with the Northern Pacific Railroad. But this is a beyond hope story.

It seems that a barber showed up in Sandpoint and worked in a barbershop there for a few days. He was reportedly a handsome, clean-shaven man with graying auburn hair who might have come from Kansas City.

None of that would have made the papers. His last act, did. The Spokesman Review reported that “he came to Hope Thursday evening showing signs of having been under the influence of liquor. During the evening, he flourished a razor in a hotel office and told the night clerk he would prove to the people present that he was a nervy man by cutting his own throat.”

The clerk talked quietly to the man and persuaded him to put the razor away.

But early the next morning the man was back. Quoting the paper, “at 5:30 he walked out onto the platform and five minutes later drew the razor from his breast pocket with his right hand, pulled down his shirt collar with the left hand, threw his head back and a little to one side, then drew the blade across his jugular and cut an awful gash in his throat.”

After that the report gets graphic. Suffice to say the man spent a minute or two dying. No clue about who he was could be found among his effects.

The paper dutifully reported that the coroner ruled the death a suicide.

Published on July 13, 2021 04:00

July 12, 2021

A Farragut ID Tag

Dan Eggart sent me a photo of an ID tag of his dad, Ronald E. Eggart. Ronald Eggart served at Farragut for a time before going to Europe during WWII. Both of his brothers also served over there.

Dan wondered what kind of ID tag it was. I’d never seen one before, so I asked Dennis Woolford who is a ranger at Farragut State Park and coauthor of a book on Farragut Naval Training Station. Dennis said it was an ID tag often used by civilians who were working on the base. He sent a photo (below) that showed several people who worked in Supply and Accounting wearing similar badges. Most wearing them were civilians, but I spot a few on Navy personnel, too. I also spot a dog some of the men snuck into the picture in the upper left-hand quadrant.

Dan wondered what kind of ID tag it was. I’d never seen one before, so I asked Dennis Woolford who is a ranger at Farragut State Park and coauthor of a book on Farragut Naval Training Station. Dennis said it was an ID tag often used by civilians who were working on the base. He sent a photo (below) that showed several people who worked in Supply and Accounting wearing similar badges. Most wearing them were civilians, but I spot a few on Navy personnel, too. I also spot a dog some of the men snuck into the picture in the upper left-hand quadrant.

Published on July 12, 2021 04:00

July 11, 2021

Basque Boarding Houses

Assimilating into a new country and culture is not something that is done overnight. The Basques had some unique ways of coping with the stress of immigration.

You may think of Basques as sheepherders because in this country they often were. For most of them it wasn’t a way of life they had known in the Old Country. It was simply a job that they could learn quickly and one that didn’t require them to take on a new language immediately. The sheep didn’t care what language they spoke.

With themselves for company Basque Sheepherders got along fine during the warm months of the year. But what to do come winter? Their solution was to come together in Basque boarding houses where they could speak the language they knew, eat familiar food, and socialize with their own people. At the same time, the boarding houses were in towns where English was common and they could learn more about their adopted country.

During much of the Twentieth Century you could find Basque boarding houses, or ostatuak, in Boise, Caldwell, Cascade, Emmett, Gooding, Hailey, Jerome, Mackay, Mountain Home, Mullan, Nampa, Pocatelo, Rupert, Shoshone, and Twin Falls. There were more than 50 of them in Boise, alone, including one at the city’s oldest standing brick building, the Jacobs-Uberuaga House (photo), built in 1864. It became a Basque boarding house in 1910. The house is now the physical and historical center of Boise’s Basque Block.

You may think of Basques as sheepherders because in this country they often were. For most of them it wasn’t a way of life they had known in the Old Country. It was simply a job that they could learn quickly and one that didn’t require them to take on a new language immediately. The sheep didn’t care what language they spoke.

With themselves for company Basque Sheepherders got along fine during the warm months of the year. But what to do come winter? Their solution was to come together in Basque boarding houses where they could speak the language they knew, eat familiar food, and socialize with their own people. At the same time, the boarding houses were in towns where English was common and they could learn more about their adopted country.

During much of the Twentieth Century you could find Basque boarding houses, or ostatuak, in Boise, Caldwell, Cascade, Emmett, Gooding, Hailey, Jerome, Mackay, Mountain Home, Mullan, Nampa, Pocatelo, Rupert, Shoshone, and Twin Falls. There were more than 50 of them in Boise, alone, including one at the city’s oldest standing brick building, the Jacobs-Uberuaga House (photo), built in 1864. It became a Basque boarding house in 1910. The house is now the physical and historical center of Boise’s Basque Block.

Published on July 11, 2021 04:00

July 10, 2021

The Art of Boise

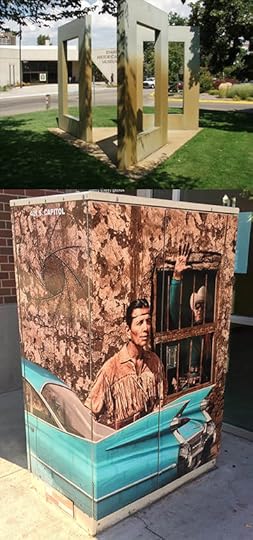

Boise is a city filled with public art, thanks largely to the efforts of the Boise City Arts and History program. But it wasn’t always that way. The first piece of public art didn’t come along until 1915, when a statute of Abraham Lincoln went up at the Old Soldier’s Home. In 1927 a life-size statue of assassinated former governor Frank Steunenberg was installed across from the Capitol’s main entrance. That was the only public art in the city until Point of Origin, a modernistic series of metal frames, was installed in front of City Hall in 1978. The sculpture, which was meant to frame various city views for the appreciative art connoisseur, generated more controversy than admiration. It was eventually moved to the grounds of the Boise Art Museum (top picture), where it ruffles fewer feathers.

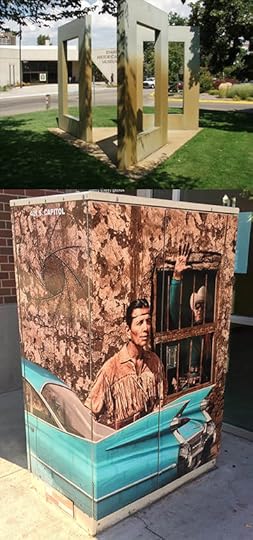

That less-than-lauded attempt to art up the city wasn’t a great start. In spite of it the city arts program has soared in recent years, with dozens of installations of major art pieces all over town, including more than 160 beloved art-wrapped traffic control boxes (bottom picture).

That less-than-lauded attempt to art up the city wasn’t a great start. In spite of it the city arts program has soared in recent years, with dozens of installations of major art pieces all over town, including more than 160 beloved art-wrapped traffic control boxes (bottom picture).

Published on July 10, 2021 04:00

July 9, 2021

A Fatality on the Interurban

One often hears a lament from Boiseans regarding the long vanished Interurban. The conversation often goes that “we” made a mistake letting that system that looped around the Treasure Valley taking passengers between and within Boise, Star, Caldwell, and other locations slip from our grasp.

I’ve often said as much myself. But what is often forgotten is that it wasn’t a municipal system. It was a commercial system or, more properly, several commercial systems. The Interurban went away because it began to cost more to run than the revenue it brought in.

Also lost in the nostalgic dreams of cheap transportation for Sunday picnics and commuting workers is the fact that the Interurban was far from perfect. If you search through newspapers of the early teens and twenties, you’ll find dozens of references to fatal “electric car” crashes all over the country on interurban lines.

The Boise & Interurban had at least one fatal collision.

On the evening of July 20, 1910, two Boise & Interurban cars collided on Hill’s curve, a half mile west of Star. The motorman on the westbound car, William Earwood of Boise, was killed in the collision, while 16 passengers were injured, none seriously. A photo of one of the cars, below, is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

The two cars were each going about 20 miles per hour at the time of the collision, which resulted when one or both conductors failed to contact dispatch for a check on traffic before entering the curve.

It is worth noting W.E. Pierce, the owner of the company, held that the Boise & Interurban was under no obligation to pay for Earwood’s death, since it was determined that he was at fault. Nevertheless, they did pay his widow $4,000.

I’ve often said as much myself. But what is often forgotten is that it wasn’t a municipal system. It was a commercial system or, more properly, several commercial systems. The Interurban went away because it began to cost more to run than the revenue it brought in.

Also lost in the nostalgic dreams of cheap transportation for Sunday picnics and commuting workers is the fact that the Interurban was far from perfect. If you search through newspapers of the early teens and twenties, you’ll find dozens of references to fatal “electric car” crashes all over the country on interurban lines.

The Boise & Interurban had at least one fatal collision.

On the evening of July 20, 1910, two Boise & Interurban cars collided on Hill’s curve, a half mile west of Star. The motorman on the westbound car, William Earwood of Boise, was killed in the collision, while 16 passengers were injured, none seriously. A photo of one of the cars, below, is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

The two cars were each going about 20 miles per hour at the time of the collision, which resulted when one or both conductors failed to contact dispatch for a check on traffic before entering the curve.

It is worth noting W.E. Pierce, the owner of the company, held that the Boise & Interurban was under no obligation to pay for Earwood’s death, since it was determined that he was at fault. Nevertheless, they did pay his widow $4,000.

Published on July 09, 2021 04:00