Rick Just's Blog, page 118

August 7, 2021

The Great Betrayal

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

In yesterday’s post we left Emma and George Bennett getting ready to leave for Helena, Mountain where they were to meet Emma’s parents and travel back to England.

George and Emma rented a little miner’s cabin on the outskirts of Helena. She didn’t want to go into town because Helena was teeming with rough and tumble miners, half of them drunk at any given time.

So, George would dutifully go into town every day to see if Emma’s parents had shown up. Every day he would come back and report that they had not. Finally, the last Missouri River flatboat of the season left Helena.

Emma could not understand why her parents had not shown up as planned. It was only later—too late—that she found they had indeed arrived in Helena. They had camped in the middle of the street so they could not be missed. George, who secretly had no desire to go back to England, had gone into town each day only to watch them and stay hidden himself, until the day they left.

It was a cruel blow to Emma, made even more devastating when she later learned that her mother and a newborn sister had both died when they arrived in England, before they even reached their home.

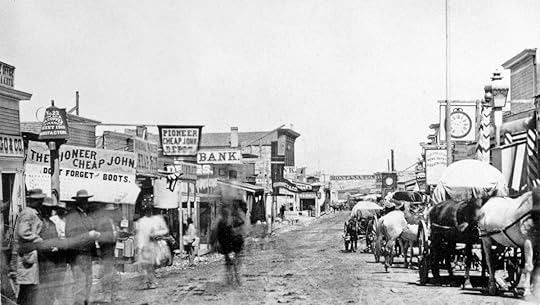

George’s betrayal was not to be his last bad deed. You’ll learn more in tomorrow’s post. This is what the main street in Helena looked like in the 1860s. It's no wonder Emma didn't want to go into town.

This is what the main street in Helena looked like in the 1860s. It's no wonder Emma didn't want to go into town.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

In yesterday’s post we left Emma and George Bennett getting ready to leave for Helena, Mountain where they were to meet Emma’s parents and travel back to England.

George and Emma rented a little miner’s cabin on the outskirts of Helena. She didn’t want to go into town because Helena was teeming with rough and tumble miners, half of them drunk at any given time.

So, George would dutifully go into town every day to see if Emma’s parents had shown up. Every day he would come back and report that they had not. Finally, the last Missouri River flatboat of the season left Helena.

Emma could not understand why her parents had not shown up as planned. It was only later—too late—that she found they had indeed arrived in Helena. They had camped in the middle of the street so they could not be missed. George, who secretly had no desire to go back to England, had gone into town each day only to watch them and stay hidden himself, until the day they left.

It was a cruel blow to Emma, made even more devastating when she later learned that her mother and a newborn sister had both died when they arrived in England, before they even reached their home.

George’s betrayal was not to be his last bad deed. You’ll learn more in tomorrow’s post.

This is what the main street in Helena looked like in the 1860s. It's no wonder Emma didn't want to go into town.

This is what the main street in Helena looked like in the 1860s. It's no wonder Emma didn't want to go into town.

Published on August 07, 2021 04:00

August 6, 2021

Stage Station Keepers

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August. Yesterday I told about the marriage of George Bennett and Emma Thompson, and how he was mustered out of the army under questionable circumstances.

After George mustered out of the army he, and Emma moved back to Morristown for a short time, then to Lincoln Creek at the foot of the Blackfoot Mountains. There they stayed with Emma’s aunt, Jane Higham and Jane’s husband, George. The Bennetts used their wagon beds as bedrooms while all used the little shanty the Highams had built for meals.

Emma milked cows and sold milk and butter to travelers headed to Montana and to nearby stage stations. That summer of 1866 they built a cabin, hauling cottonwood logs 15 miles from where the trees grew along the Snake River near present day Firth. As Emma wrote, “(the house was) eight logs high, one door, a window or hole with cloth for glass, a fireplace of rocks, the ground for a floor. Willows and grass with mud on top for the roof. The cracks between the logs filled with more mud.”

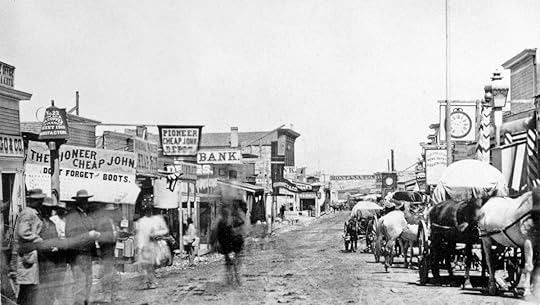

During the winter of 1866 and 1867, George and Emma took a job managing the stage station at Taylor Bridge. Where that bridge crossed the Snake River would soon be called Eagle Rock, then later Idaho Falls. They were paid $60 a month. In March they went to Ross Fork to manage a stage station for Wells Fargo for $75 a month.

At both stage stations Emma cooked, and George tended the livestock. Stagecoaches would arrive at all hours. Passengers came in for a bite to eat while fresh horses were harnessed up. Stage stops were located 10 or 15 miles from each other because that’s as far as a team could travel. Stages could make 100 miles in a day this way.

In the fall of 1867 Emma’s parents, who were still at Morristown, decided they’d had enough of this rugged land and would move back to England. They had lost a younger daughter that winter and Emma’s mother, Frances was despondent. She just wanted to go home. She also wanted Emma and her husband to go with them.

Emma wasn’t keen about moving back to England, a place she had no memories of, but she was a good daughter. So, Emma and George set out for Helena, Montana where they were to meet up with the Thompsons and take a steamer down the Missouri to the Mississippi and on to New Orleans where they would catch a ship back to England.

Tomorrow we’ll learn just what sort of scoundrel George Bennett was.

Taylor Bridge in 1871. William Henry Jackson photo.

Taylor Bridge in 1871. William Henry Jackson photo.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August. Yesterday I told about the marriage of George Bennett and Emma Thompson, and how he was mustered out of the army under questionable circumstances.

After George mustered out of the army he, and Emma moved back to Morristown for a short time, then to Lincoln Creek at the foot of the Blackfoot Mountains. There they stayed with Emma’s aunt, Jane Higham and Jane’s husband, George. The Bennetts used their wagon beds as bedrooms while all used the little shanty the Highams had built for meals.

Emma milked cows and sold milk and butter to travelers headed to Montana and to nearby stage stations. That summer of 1866 they built a cabin, hauling cottonwood logs 15 miles from where the trees grew along the Snake River near present day Firth. As Emma wrote, “(the house was) eight logs high, one door, a window or hole with cloth for glass, a fireplace of rocks, the ground for a floor. Willows and grass with mud on top for the roof. The cracks between the logs filled with more mud.”

During the winter of 1866 and 1867, George and Emma took a job managing the stage station at Taylor Bridge. Where that bridge crossed the Snake River would soon be called Eagle Rock, then later Idaho Falls. They were paid $60 a month. In March they went to Ross Fork to manage a stage station for Wells Fargo for $75 a month.

At both stage stations Emma cooked, and George tended the livestock. Stagecoaches would arrive at all hours. Passengers came in for a bite to eat while fresh horses were harnessed up. Stage stops were located 10 or 15 miles from each other because that’s as far as a team could travel. Stages could make 100 miles in a day this way.

In the fall of 1867 Emma’s parents, who were still at Morristown, decided they’d had enough of this rugged land and would move back to England. They had lost a younger daughter that winter and Emma’s mother, Frances was despondent. She just wanted to go home. She also wanted Emma and her husband to go with them.

Emma wasn’t keen about moving back to England, a place she had no memories of, but she was a good daughter. So, Emma and George set out for Helena, Montana where they were to meet up with the Thompsons and take a steamer down the Missouri to the Mississippi and on to New Orleans where they would catch a ship back to England.

Tomorrow we’ll learn just what sort of scoundrel George Bennett was.

Taylor Bridge in 1871. William Henry Jackson photo.

Taylor Bridge in 1871. William Henry Jackson photo.

Published on August 06, 2021 04:00

August 5, 2021

The Scoundrel Soldier

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Yesterday we learned about Emma and her connection to the famous Ninety Percent Spring near Soda Springs.

Emma Thompson was a teenager at Morristown, though that term—teenager—was yet to be invented. Her memories about those days were full of community dances and handsome soldiers. She would marry one in February 1865, a month after her 15th birthday.

Emma Thompson married 28-year-old George Waldrum Bennett, a supply sergeant.

George Bennett was an Englishman who had travelled extensively, and whose father was a well-known actor and playwright at the time in England.

In his blue uniform with brass buttons—naïve Emma thought they were gold at first—he must have been a dashing figure to a young girl who had known little but dirt floors and hard work to that point. Early on in their marriage, though, there was a hint of trouble.

The army moved George Bennett and his new wife to Fort Douglas, Utah, where he worked in the commissary. The commissary burned down, and Sergeant Bennett was suspected of causing the fire. He was thrown in the guardhouse along with another man.

This left 15-year-old Emma alone, and frightened about what would happen to her. After a few days she worked up the courage to go inquire about George’s fate.

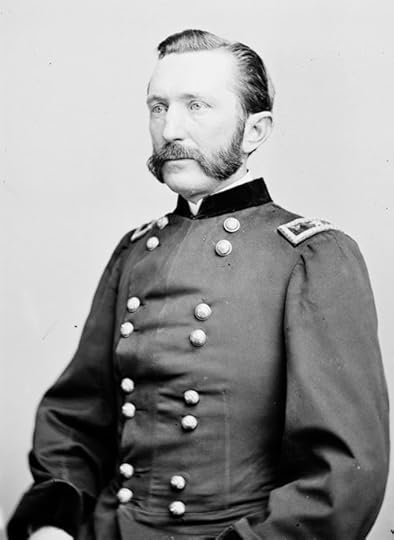

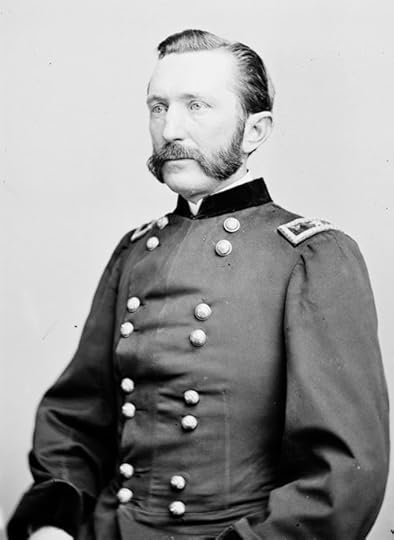

It was post commander Patrick Conner she went to see. By that time, he was Brigadier General Conner, and a very imposing figure. Emma pleaded for mercy for her husband.

At some point General Conner expressed his surprise, by saying, “Why, my child, you are married?” He ended their meeting with the words, “We’ll see what we can do about it.”

George Bennett (or, George Waldron, see story below) was released the next day, and soon was mustered out of the army.

Tomorrow we’ll catch up with Emma and George back in Idaho.

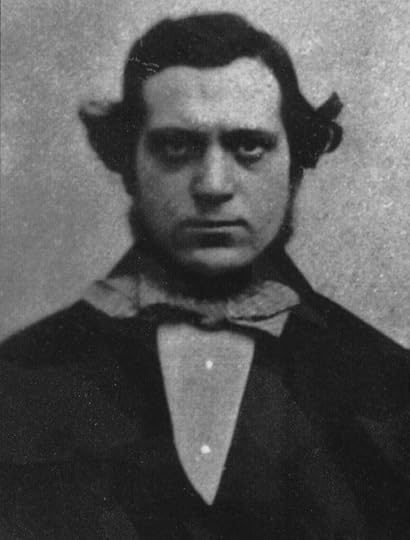

We don’t know for sure if this is a picture of George Bennett. It is a tintype, showing what seems to be a military man of about the right age. It is among the possessions of Emma passed down through her family.

We don’t know for sure if this is a picture of George Bennett. It is a tintype, showing what seems to be a military man of about the right age. It is among the possessions of Emma passed down through her family.

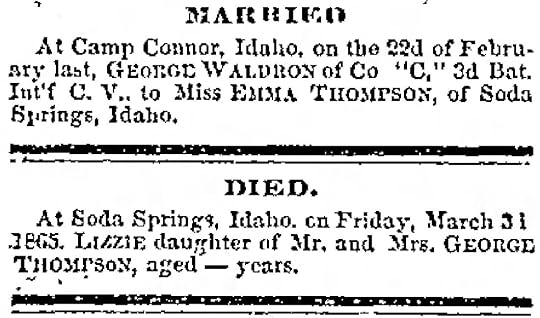

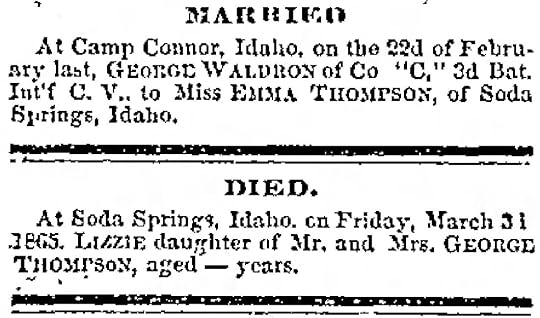

General Patrick Conner An Aside About George Bennett It has been difficult for the Just/Reid family to learn more about Bennett’s days with the California Volunteers. Oddly, he had enlisted under the name George Waldron. We learned this recently when I stumbled across the wedding announcement for George and Emma in the Union Vedette, the Fort Douglas camp newsletter. It also carried news from Fort Conner at present-day Soda Springs.

General Patrick Conner An Aside About George Bennett It has been difficult for the Just/Reid family to learn more about Bennett’s days with the California Volunteers. Oddly, he had enlisted under the name George Waldron. We learned this recently when I stumbled across the wedding announcement for George and Emma in the Union Vedette, the Fort Douglas camp newsletter. It also carried news from Fort Conner at present-day Soda Springs.

We can only speculate about why Bennett registered under an assumed name. He would later show a villainous side, so perhaps he was trying to cover his tracks. Although know the name he used in the army help us to track him, it also complicated it. There was a George Waldron who was a well-known actor in the West at the time, and he and our George were often in the same towns at the same time. Further complicating our search was the fact that our George also acted in local productions from time to time.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Yesterday we learned about Emma and her connection to the famous Ninety Percent Spring near Soda Springs.

Emma Thompson was a teenager at Morristown, though that term—teenager—was yet to be invented. Her memories about those days were full of community dances and handsome soldiers. She would marry one in February 1865, a month after her 15th birthday.

Emma Thompson married 28-year-old George Waldrum Bennett, a supply sergeant.

George Bennett was an Englishman who had travelled extensively, and whose father was a well-known actor and playwright at the time in England.

In his blue uniform with brass buttons—naïve Emma thought they were gold at first—he must have been a dashing figure to a young girl who had known little but dirt floors and hard work to that point. Early on in their marriage, though, there was a hint of trouble.

The army moved George Bennett and his new wife to Fort Douglas, Utah, where he worked in the commissary. The commissary burned down, and Sergeant Bennett was suspected of causing the fire. He was thrown in the guardhouse along with another man.

This left 15-year-old Emma alone, and frightened about what would happen to her. After a few days she worked up the courage to go inquire about George’s fate.

It was post commander Patrick Conner she went to see. By that time, he was Brigadier General Conner, and a very imposing figure. Emma pleaded for mercy for her husband.

At some point General Conner expressed his surprise, by saying, “Why, my child, you are married?” He ended their meeting with the words, “We’ll see what we can do about it.”

George Bennett (or, George Waldron, see story below) was released the next day, and soon was mustered out of the army.

Tomorrow we’ll catch up with Emma and George back in Idaho.

We don’t know for sure if this is a picture of George Bennett. It is a tintype, showing what seems to be a military man of about the right age. It is among the possessions of Emma passed down through her family.

We don’t know for sure if this is a picture of George Bennett. It is a tintype, showing what seems to be a military man of about the right age. It is among the possessions of Emma passed down through her family. General Patrick Conner An Aside About George Bennett It has been difficult for the Just/Reid family to learn more about Bennett’s days with the California Volunteers. Oddly, he had enlisted under the name George Waldron. We learned this recently when I stumbled across the wedding announcement for George and Emma in the Union Vedette, the Fort Douglas camp newsletter. It also carried news from Fort Conner at present-day Soda Springs.

General Patrick Conner An Aside About George Bennett It has been difficult for the Just/Reid family to learn more about Bennett’s days with the California Volunteers. Oddly, he had enlisted under the name George Waldron. We learned this recently when I stumbled across the wedding announcement for George and Emma in the Union Vedette, the Fort Douglas camp newsletter. It also carried news from Fort Conner at present-day Soda Springs.We can only speculate about why Bennett registered under an assumed name. He would later show a villainous side, so perhaps he was trying to cover his tracks. Although know the name he used in the army help us to track him, it also complicated it. There was a George Waldron who was a well-known actor in the West at the time, and he and our George were often in the same towns at the same time. Further complicating our search was the fact that our George also acted in local productions from time to time.

Published on August 05, 2021 04:00

August 4, 2021

Emma Finds a Spring

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August. Yesterday I told the story about the Morrisite War. If you missed it, you might want to click previous below to get the rest of the story.

The displaced followers of Joseph Morris were escorted out of Utah and into the newly formed Idaho Territory in 1863 in the aftermath of the Morrisite War. They founded a community called Morristown, named in honor of their martyred leader, Joseph Morris.

The stop on the Oregon Trail had been called Soda Springs since at least 1859, because of several naturally carbonated springs in the area. As more settlers moved in, that town name took hold and Morristown was soon forgotten. The site where it stood is largely covered by the waters of Anderson Reservoir.

When the Morrisites first arrived a group of teenagers discovered another spring nearby. Emma Thompson was among them and wrote about it in a letter to a cousin:

“We had not been here long when a party of us young folk discovered an especially good spring not far from our settlement. People who have tasted the famed water of other countries say it is as fine as any. I don’t think anyone had ever tasted I before, for the men took the sod away and opened up the source. They have named it Ninety Percent Spring.”

I’ve never seen an explanation for the name.

Here’s a little piece that has appeared on my blog before about the mineral water from that spring:

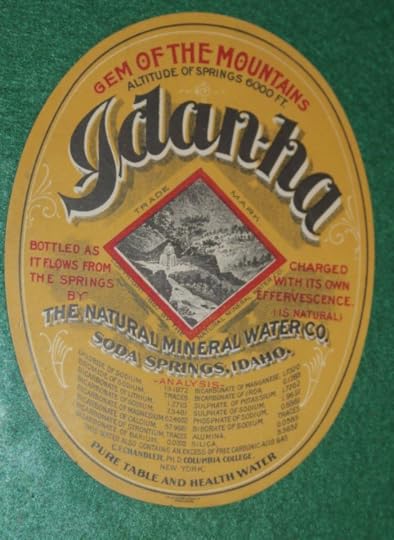

Bottled water is ubiquitous. It’s shipped all over the world and consumed by the billions of gallons by people who usually have a faucet nearby. But before I get off on a rant, I want to say that bottling water and shipping it all over the globe isn’t a new thing. They were doing it in Idaho in 1887.

The Natural Mineral Water Co. incorporated May 17, 1887 was located in Soda Springs, Idaho. They bottled water from Ninety Percent Springs and called it Idanha. Some claim the name is an Indian word meaning something like “spirit of healing waters.” The company would sometimes spell it Idan-Ha. The Idanha Hotel, built by the Union Pacific, came along that same year. That’s the one in Soda Springs. Boise’s Idanha, named after the earlier hotel, came along later.

Idanha water was shipped to eastern markets and foreign countries. It won first prize at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. The water is said to have won first place at a World’s Fair in Paris, though the date isn’t certain.

The bottling works burned down in 1895. One might wonder what would burn in a water bottling plant. Nevertheless, it did burn and was rebuilt, getting back to business a couple of years later. The plant filled a million bottles a year in the early days.

Idanha was a great name for a couple of hotels and premium bottled water. It still serves as the name of a town in Oregon. Historians agree that the town name was linked to Idanha water in some way, but no one seems to know how.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August. Yesterday I told the story about the Morrisite War. If you missed it, you might want to click previous below to get the rest of the story.

The displaced followers of Joseph Morris were escorted out of Utah and into the newly formed Idaho Territory in 1863 in the aftermath of the Morrisite War. They founded a community called Morristown, named in honor of their martyred leader, Joseph Morris.

The stop on the Oregon Trail had been called Soda Springs since at least 1859, because of several naturally carbonated springs in the area. As more settlers moved in, that town name took hold and Morristown was soon forgotten. The site where it stood is largely covered by the waters of Anderson Reservoir.

When the Morrisites first arrived a group of teenagers discovered another spring nearby. Emma Thompson was among them and wrote about it in a letter to a cousin:

“We had not been here long when a party of us young folk discovered an especially good spring not far from our settlement. People who have tasted the famed water of other countries say it is as fine as any. I don’t think anyone had ever tasted I before, for the men took the sod away and opened up the source. They have named it Ninety Percent Spring.”

I’ve never seen an explanation for the name.

Here’s a little piece that has appeared on my blog before about the mineral water from that spring:

Bottled water is ubiquitous. It’s shipped all over the world and consumed by the billions of gallons by people who usually have a faucet nearby. But before I get off on a rant, I want to say that bottling water and shipping it all over the globe isn’t a new thing. They were doing it in Idaho in 1887.

The Natural Mineral Water Co. incorporated May 17, 1887 was located in Soda Springs, Idaho. They bottled water from Ninety Percent Springs and called it Idanha. Some claim the name is an Indian word meaning something like “spirit of healing waters.” The company would sometimes spell it Idan-Ha. The Idanha Hotel, built by the Union Pacific, came along that same year. That’s the one in Soda Springs. Boise’s Idanha, named after the earlier hotel, came along later.

Idanha water was shipped to eastern markets and foreign countries. It won first prize at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. The water is said to have won first place at a World’s Fair in Paris, though the date isn’t certain.

The bottling works burned down in 1895. One might wonder what would burn in a water bottling plant. Nevertheless, it did burn and was rebuilt, getting back to business a couple of years later. The plant filled a million bottles a year in the early days.

Idanha was a great name for a couple of hotels and premium bottled water. It still serves as the name of a town in Oregon. Historians agree that the town name was linked to Idanha water in some way, but no one seems to know how.

Published on August 04, 2021 04:00

August 3, 2021

Emma and the Morrisite War

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

We’re going to spend some time in Utah for this post. Trust me. We’ll get to the Idaho connection.

In 1857 Mormon convert Joseph Morris began seeing visions and getting messages from God. As this was in the tradition of the church, he felt he should get some recognition for being a chosen one. He began writing letters to church leader Brigham Young telling him of the visions and assuring the man that God had a plan for Young. He was to be second in command to Joseph Morris.

Brigham Young took little notice, never bothering to reply, though Morris continued to pester him with prophecies.

Morris began to gather disaffected Mormons around him and preach about God’s revelations. Some of the Mormons had been converted in faraway places such as Denmark. Their English was not good, and they were surprised and dismayed to learn about certain church practices such as polygamy when they found their way to Utah.

In 1861 Morris gathered his flock of about 300 believers in the newly named Church of the First Born at an old stockade called Kington Fort at what is now known as South Weber. As per the received wisdom of God, they planted no crops. What was the point? Jesus was on his way.

Jesus was delayed, several times, and as each appointment slid by with no savior, more and more Morrisites, which they were also called, grew disenchanted. Some of them felt they had not received supplies commensurate with what they had contributed to the commune upon their departure. Two men hijacked a Morrisite grain wagon to make things even. The Morrisites caught them and brought them back to the fort to be “tried by the Lord when he came.”

The wives of the captured men pleaded with the territorial government to intervene. Chief Justice John Kinney sent the U.S. Marshall with an order demanding their release. The Morrisites refused. So, Justice Kinney activated the territorial militia as a posse comitatus to arrest the Morrisite leaders. What became known as the Mormon Militia, led by Deputy U.S. Marshall Robert T. Burton, set out for Kington Fort. Once they arrived, Burton demanded the release of the men.

Morris refused, even with somewhere between 500 and 1,000 men gathered on the hills above the fort. When a 30-minute ultimatum came from Burton, Morris secluded himself to receive instructions from God.

The faithful gathered beneath a brush arbor to hear Morris tell them what God had told him. At that point a cannonball came bouncing into the fort and through the crowd, killing two women outright and shattering the jaw of a young girl.

The Morrisites held out for three days before finally surrendering. The surrender did not go well. In a final kerfuffle inside the fort, Burton shot and killed Morris. Others were also killed. The total tally of dead in the Morrisite War was 11, two of them militia members.

Emma Thompson, nee Just, and her parents were followers of Joseph Morris. George Thompson played a dramatic role during the surrender of the Morrisites. Here is the story in Emma's own words:

"We Morrisites thought that none of our number who were faithful could be killed. Even when Morris was shot and fell lifeless to the ground we did not think him dead. I saw the wadding fly back from his clothes and thought it was the bullets rebounding from him. We considered him invulnerable, or that if he should be killed he would be immediately restored to life. When Morris was killed my father sat upon his body saying, 'Now kill me, for I have nothing more to live for.'"

Fortunately, when Burton aimed his pistol at Emma's father, the gun misfired, giving other Morrisites the opportunity to drag George Thompson away.

Morris’s body was put on display in front of city hall in Salt Lake City. In the subsequent trial, in 1863, 66 Morrisites were convicted of resistance and fined $100 each. Seven were convicted of second degree murder.

Fortunately for the Morrisites a new governor had been appointed to oversee Utah Territory. Within three days of their conviction, he pardoned all the Morrisites.

Leaving Utah was high on the to do list for most Morrisites. A hundred or so went to Carson City Nevada. One hundred and sixty opted to try the newly formed Idaho Territory to the north.

The Morrisites were escorted north by a contingent of troops from the California Volunteers, a group of men who had signed up for the military so they could fight on the side of the Union in the Civil War, but who found themselves instead stationed in Utah, fighting Indians and protecting apostates. They were led by Colonel Patrick E. Conner.

The soldiers created Camp Conner, near the present day city of Soda Springs, while the Morrisites started a town they named after their fallen leader, Morristown. Morristown would last only a few years before being subsumed by the community of Soda Springs. Many of the Morrisites moved north to help in the founding of Blackfoot. Others, still, moved to Deer Lodge, Montana where their Church of the First Born continued into the 1950s.

I’m a descendant of the Morrisites who founded Morristown and settled in the Blackfoot area. I often present a one-hour lecture on the Morrisite War at various venues around Idaho. If you want to learn more about the Morrisites I recommend two books. The first is the definitive historical examination by C. LeRoy Anderson,PhD, called Joseph Morris and the Saga of the Morrisites . The second, written by my great aunt Agnes Just Reid, is called Letters of Long Ago . I also invite you to listen to my YouTube presentation on the Morrisite War. For information on my program, please contact me through my website. The only known photo of Joseph Morris, circa 1860.

The only known photo of Joseph Morris, circa 1860.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

We’re going to spend some time in Utah for this post. Trust me. We’ll get to the Idaho connection.

In 1857 Mormon convert Joseph Morris began seeing visions and getting messages from God. As this was in the tradition of the church, he felt he should get some recognition for being a chosen one. He began writing letters to church leader Brigham Young telling him of the visions and assuring the man that God had a plan for Young. He was to be second in command to Joseph Morris.

Brigham Young took little notice, never bothering to reply, though Morris continued to pester him with prophecies.

Morris began to gather disaffected Mormons around him and preach about God’s revelations. Some of the Mormons had been converted in faraway places such as Denmark. Their English was not good, and they were surprised and dismayed to learn about certain church practices such as polygamy when they found their way to Utah.

In 1861 Morris gathered his flock of about 300 believers in the newly named Church of the First Born at an old stockade called Kington Fort at what is now known as South Weber. As per the received wisdom of God, they planted no crops. What was the point? Jesus was on his way.

Jesus was delayed, several times, and as each appointment slid by with no savior, more and more Morrisites, which they were also called, grew disenchanted. Some of them felt they had not received supplies commensurate with what they had contributed to the commune upon their departure. Two men hijacked a Morrisite grain wagon to make things even. The Morrisites caught them and brought them back to the fort to be “tried by the Lord when he came.”

The wives of the captured men pleaded with the territorial government to intervene. Chief Justice John Kinney sent the U.S. Marshall with an order demanding their release. The Morrisites refused. So, Justice Kinney activated the territorial militia as a posse comitatus to arrest the Morrisite leaders. What became known as the Mormon Militia, led by Deputy U.S. Marshall Robert T. Burton, set out for Kington Fort. Once they arrived, Burton demanded the release of the men.

Morris refused, even with somewhere between 500 and 1,000 men gathered on the hills above the fort. When a 30-minute ultimatum came from Burton, Morris secluded himself to receive instructions from God.

The faithful gathered beneath a brush arbor to hear Morris tell them what God had told him. At that point a cannonball came bouncing into the fort and through the crowd, killing two women outright and shattering the jaw of a young girl.

The Morrisites held out for three days before finally surrendering. The surrender did not go well. In a final kerfuffle inside the fort, Burton shot and killed Morris. Others were also killed. The total tally of dead in the Morrisite War was 11, two of them militia members.

Emma Thompson, nee Just, and her parents were followers of Joseph Morris. George Thompson played a dramatic role during the surrender of the Morrisites. Here is the story in Emma's own words:

"We Morrisites thought that none of our number who were faithful could be killed. Even when Morris was shot and fell lifeless to the ground we did not think him dead. I saw the wadding fly back from his clothes and thought it was the bullets rebounding from him. We considered him invulnerable, or that if he should be killed he would be immediately restored to life. When Morris was killed my father sat upon his body saying, 'Now kill me, for I have nothing more to live for.'"

Fortunately, when Burton aimed his pistol at Emma's father, the gun misfired, giving other Morrisites the opportunity to drag George Thompson away.

Morris’s body was put on display in front of city hall in Salt Lake City. In the subsequent trial, in 1863, 66 Morrisites were convicted of resistance and fined $100 each. Seven were convicted of second degree murder.

Fortunately for the Morrisites a new governor had been appointed to oversee Utah Territory. Within three days of their conviction, he pardoned all the Morrisites.

Leaving Utah was high on the to do list for most Morrisites. A hundred or so went to Carson City Nevada. One hundred and sixty opted to try the newly formed Idaho Territory to the north.

The Morrisites were escorted north by a contingent of troops from the California Volunteers, a group of men who had signed up for the military so they could fight on the side of the Union in the Civil War, but who found themselves instead stationed in Utah, fighting Indians and protecting apostates. They were led by Colonel Patrick E. Conner.

The soldiers created Camp Conner, near the present day city of Soda Springs, while the Morrisites started a town they named after their fallen leader, Morristown. Morristown would last only a few years before being subsumed by the community of Soda Springs. Many of the Morrisites moved north to help in the founding of Blackfoot. Others, still, moved to Deer Lodge, Montana where their Church of the First Born continued into the 1950s.

I’m a descendant of the Morrisites who founded Morristown and settled in the Blackfoot area. I often present a one-hour lecture on the Morrisite War at various venues around Idaho. If you want to learn more about the Morrisites I recommend two books. The first is the definitive historical examination by C. LeRoy Anderson,PhD, called Joseph Morris and the Saga of the Morrisites . The second, written by my great aunt Agnes Just Reid, is called Letters of Long Ago . I also invite you to listen to my YouTube presentation on the Morrisite War. For information on my program, please contact me through my website.

The only known photo of Joseph Morris, circa 1860.

The only known photo of Joseph Morris, circa 1860.

Published on August 03, 2021 04:00

August 2, 2021

Two Journeys to America

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August he history of a family goes back beyond memory, of course. The Justs and Reids focus mostly on our family story that began when Nels Just and Emma Thompson, who would become our most studied ancestors, came to the United States as children. Today I’ll share a snapshot of the journeys that first brought them to Utah. Much of this material has been passed down for generations, the name of the original author forgotten.

The Journey of Emma Thompson

Emma was three years old when she left England with her parents for the United States in 1853. Her father, George, was 27. Frances, her mother, was 26. George Thompson’s sister, Jane, and her husband Charles Higham were also on board. Both families would lose children while at sea. The Highams lost their two-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, on the voyage. The Thompsons lost their infant daughter Georgiana.

The Thompsons and the Highams were among the 209 passengers who sailed aboard the Onward from Liverpool. They were the only Mormon converts on the ship. The Onward docked in New Orleans on January 17, 1854.

The Mormon converts stayed in New Orleans long enough for Jane Higham to give birth to a girl, Polly, on January 30, and for Frances Thompson to give birth to George William Thompson on April 20. Two-month-old George William died on June 13 in St. Louis while on their journey west.

Emma had few memories about the journey since she was so young at the time. Years later she wrote this about the wagon trip to Utah:

“My father drove an ox team for an invalid who had a good outfit but was unable to drive. We started from Ft Leavenworth Kansas. I cannot remember much about it, only days and days in a covered wagon. Once the whole train had to stop to let a big heard of buffalo pass. We could see the long black string making a big dust as they shuffled along with their shaggy coats. They were the only ones I ever saw, yet we have owned many of their robes. Dad had a coat as late as 1876. Another incident I can recall, of some painted Indians. Two or three were sitting in the front of the wagon asking for many things. The sick man told my mother to give them anything they wanted, if they would only go. After getting a few articles of food they left, to great relief of us all. The next circumstance is of a young woman being killed; fell out of the wagon one night when we were driving late and was run over. I can distinctly remember seeing her lying in a tent, one ear was bloody, her name was Fisher.

“On arriving in Salt Lake, the invalid, his team and all his belongings were given over to the Mormon Elders, whom he had seen in England. Never knew what became of his property, he died soon after. His only wish was to live long enough to see ‘Zion.’”

The Journey of Nels Just

Nels Just came to the United States and went on to Utah Territory four years after Emma and her parents. He was 10 when his parents became Mormons and left Denmark. The Thompson and Higham families were the only Mormons on board the Onward. The ship the Justs travelled on was packed with LDS converts.

In 1857 the immigrants traveled to England where they boarded the huge ship, Westmoreland at Liverpool. There were 340 Scandinavians and four presiding elders. The trip took 36 days to cross the Atlantic and they landed at Philadelphia on May 31, 1857. The group traveled to Baltimore, Maryland, then to Wheeling, Virginia and finally arrived at Iowa City, Iowa. Later, by wagon, they traveled to Florence, Nebraska where the trek to Utah began.

There, two companies were formed. The Justs were assigned to the Christiansen Handcart Company. These two companies were the last to leave Florence that year. They left one day apart, and arrived in Salt Lake the same day, September 3, 1857.

In the Just’s Company, there were 68 handcarts, three wagons and ten mules. Strong men, women and children pulled the handcarts. Ten-year-old Nels probably did his share

of pulling a handcart. Often in adverse conditions such as mud, deep ruts, sand, each handcart had to be pulled and pushed to make progress.

The three wagons carried treasures the immigrants brought from Denmark for their new homes in Salt Lake but it was not long before most of the treasures were discarded to make room for the sick and others unable to walk. The group encountered bad storms and extremely hot, dry weather. Often they camped where there was no water. They had to ration their food and ford streams and rivers. At one such river, several Indians helped them across, riding their horses while a pioneer woman or child behind them clung to their naked bodies. The travelers had

little clothing of their own.

The trek was hard on shoes. Many ingenious repairs of shoes were made so the pioneers could keep walking. There was much sickness and as many as one in ten died and were buried on the trail. There were some births. One night one of the women disappeared and returned bringing a baby girl in her apron. That baby survived and still was living in Utah at least in 1911.

Some days they practically starved although they saw herds of buffalo. According to the diaries of the trek, they did not kill any for food, fearing a buffalo stampede. At one point the group encountered a troop of military men who offered them a crippled beef, which they gratefully accepted.

The Ship Westmoreland, with U.S. registry, weighing 999 tons, R. Decan serving as Ship’s Master, departed Liverpool, England, April 25, 1857, arrived at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 31, 1857. The number of LDS passengers was reported as 544, a number that included Nels Just, his parents and siblings. C.C.A Christensen, who painted the picture above, was one of the Westmoreland’s ship’s stewards during the voyage from Liverpool. He distributed water and provisions to the passengers, was the clerk of the company and kept a record of the voyage in English. This watercolor was painted some ten years after the voyage, (1867) from memory and except for the star and a few other small details, is noted as being correct for the Westmoreland. No photograph of the Westmoreland is known to exist. Note the painted black squares along the sides of the ship to simulate gun port hatches. From a distance, this was a powerful deterrent to the sea raiders of the time.

The Ship Westmoreland, with U.S. registry, weighing 999 tons, R. Decan serving as Ship’s Master, departed Liverpool, England, April 25, 1857, arrived at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 31, 1857. The number of LDS passengers was reported as 544, a number that included Nels Just, his parents and siblings. C.C.A Christensen, who painted the picture above, was one of the Westmoreland’s ship’s stewards during the voyage from Liverpool. He distributed water and provisions to the passengers, was the clerk of the company and kept a record of the voyage in English. This watercolor was painted some ten years after the voyage, (1867) from memory and except for the star and a few other small details, is noted as being correct for the Westmoreland. No photograph of the Westmoreland is known to exist. Note the painted black squares along the sides of the ship to simulate gun port hatches. From a distance, this was a powerful deterrent to the sea raiders of the time.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August he history of a family goes back beyond memory, of course. The Justs and Reids focus mostly on our family story that began when Nels Just and Emma Thompson, who would become our most studied ancestors, came to the United States as children. Today I’ll share a snapshot of the journeys that first brought them to Utah. Much of this material has been passed down for generations, the name of the original author forgotten.

The Journey of Emma Thompson

Emma was three years old when she left England with her parents for the United States in 1853. Her father, George, was 27. Frances, her mother, was 26. George Thompson’s sister, Jane, and her husband Charles Higham were also on board. Both families would lose children while at sea. The Highams lost their two-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, on the voyage. The Thompsons lost their infant daughter Georgiana.

The Thompsons and the Highams were among the 209 passengers who sailed aboard the Onward from Liverpool. They were the only Mormon converts on the ship. The Onward docked in New Orleans on January 17, 1854.

The Mormon converts stayed in New Orleans long enough for Jane Higham to give birth to a girl, Polly, on January 30, and for Frances Thompson to give birth to George William Thompson on April 20. Two-month-old George William died on June 13 in St. Louis while on their journey west.

Emma had few memories about the journey since she was so young at the time. Years later she wrote this about the wagon trip to Utah:

“My father drove an ox team for an invalid who had a good outfit but was unable to drive. We started from Ft Leavenworth Kansas. I cannot remember much about it, only days and days in a covered wagon. Once the whole train had to stop to let a big heard of buffalo pass. We could see the long black string making a big dust as they shuffled along with their shaggy coats. They were the only ones I ever saw, yet we have owned many of their robes. Dad had a coat as late as 1876. Another incident I can recall, of some painted Indians. Two or three were sitting in the front of the wagon asking for many things. The sick man told my mother to give them anything they wanted, if they would only go. After getting a few articles of food they left, to great relief of us all. The next circumstance is of a young woman being killed; fell out of the wagon one night when we were driving late and was run over. I can distinctly remember seeing her lying in a tent, one ear was bloody, her name was Fisher.

“On arriving in Salt Lake, the invalid, his team and all his belongings were given over to the Mormon Elders, whom he had seen in England. Never knew what became of his property, he died soon after. His only wish was to live long enough to see ‘Zion.’”

The Journey of Nels Just

Nels Just came to the United States and went on to Utah Territory four years after Emma and her parents. He was 10 when his parents became Mormons and left Denmark. The Thompson and Higham families were the only Mormons on board the Onward. The ship the Justs travelled on was packed with LDS converts.

In 1857 the immigrants traveled to England where they boarded the huge ship, Westmoreland at Liverpool. There were 340 Scandinavians and four presiding elders. The trip took 36 days to cross the Atlantic and they landed at Philadelphia on May 31, 1857. The group traveled to Baltimore, Maryland, then to Wheeling, Virginia and finally arrived at Iowa City, Iowa. Later, by wagon, they traveled to Florence, Nebraska where the trek to Utah began.

There, two companies were formed. The Justs were assigned to the Christiansen Handcart Company. These two companies were the last to leave Florence that year. They left one day apart, and arrived in Salt Lake the same day, September 3, 1857.

In the Just’s Company, there were 68 handcarts, three wagons and ten mules. Strong men, women and children pulled the handcarts. Ten-year-old Nels probably did his share

of pulling a handcart. Often in adverse conditions such as mud, deep ruts, sand, each handcart had to be pulled and pushed to make progress.

The three wagons carried treasures the immigrants brought from Denmark for their new homes in Salt Lake but it was not long before most of the treasures were discarded to make room for the sick and others unable to walk. The group encountered bad storms and extremely hot, dry weather. Often they camped where there was no water. They had to ration their food and ford streams and rivers. At one such river, several Indians helped them across, riding their horses while a pioneer woman or child behind them clung to their naked bodies. The travelers had

little clothing of their own.

The trek was hard on shoes. Many ingenious repairs of shoes were made so the pioneers could keep walking. There was much sickness and as many as one in ten died and were buried on the trail. There were some births. One night one of the women disappeared and returned bringing a baby girl in her apron. That baby survived and still was living in Utah at least in 1911.

Some days they practically starved although they saw herds of buffalo. According to the diaries of the trek, they did not kill any for food, fearing a buffalo stampede. At one point the group encountered a troop of military men who offered them a crippled beef, which they gratefully accepted.

The Ship Westmoreland, with U.S. registry, weighing 999 tons, R. Decan serving as Ship’s Master, departed Liverpool, England, April 25, 1857, arrived at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 31, 1857. The number of LDS passengers was reported as 544, a number that included Nels Just, his parents and siblings. C.C.A Christensen, who painted the picture above, was one of the Westmoreland’s ship’s stewards during the voyage from Liverpool. He distributed water and provisions to the passengers, was the clerk of the company and kept a record of the voyage in English. This watercolor was painted some ten years after the voyage, (1867) from memory and except for the star and a few other small details, is noted as being correct for the Westmoreland. No photograph of the Westmoreland is known to exist. Note the painted black squares along the sides of the ship to simulate gun port hatches. From a distance, this was a powerful deterrent to the sea raiders of the time.

The Ship Westmoreland, with U.S. registry, weighing 999 tons, R. Decan serving as Ship’s Master, departed Liverpool, England, April 25, 1857, arrived at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 31, 1857. The number of LDS passengers was reported as 544, a number that included Nels Just, his parents and siblings. C.C.A Christensen, who painted the picture above, was one of the Westmoreland’s ship’s stewards during the voyage from Liverpool. He distributed water and provisions to the passengers, was the clerk of the company and kept a record of the voyage in English. This watercolor was painted some ten years after the voyage, (1867) from memory and except for the star and a few other small details, is noted as being correct for the Westmoreland. No photograph of the Westmoreland is known to exist. Note the painted black squares along the sides of the ship to simulate gun port hatches. From a distance, this was a powerful deterrent to the sea raiders of the time.

Published on August 02, 2021 04:00

August 1, 2021

The Story of a Name

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August While most of the family stories I tell this month will have a solid Idaho connection, some will be background about the family before our ancestors got here in 1863. This story, and the two following it, are such background.

There has always been some confusion in the Just family about our surname. Nels Just’s father was named Peder (or Peter, in the English spelling) Anderson Just. Some argue that he actually went by Anderson. His father’s name was Anders Justsen, and HIS father’s name was Just Pedersen. What’s up with that? Is Just even a “real” name? Let me enlighten and confuse you.

A couple of centuries ago, Danish people did not have last names or surnames as we know them. They used a system called patronymics, instead. In this naming system, a male child’s patronymic or “efternavn” (English translation: “after name”) was formed from his father’s first name plus – sen (English translation – “son”). Since Just Pedersen’s boy was a “son of Just,” his name was recorded as Just’s sen thus “JUSTSEN.” This is why Anders Justsen had the JUSTSEN “after name.” He was Just’s son. A female child’s patronymic was formed from her father’s first name plus – datter (daughter) and so, a Just girl was “Just’s daughter,” her name was recorded as Ann JUSTDATTER. The Danes dropped the possessive in the patronymic, which is why there is only one “s” in Justsen and Pedersen.

To confuse things even further, the first two male children often received the paternal and maternal grandparents’ names, respectively, to honor their ancestors. If both grandfathers or both grandmothers had the same name (which was not unusual) and if at least two boys or two girls were born to the parents, the family would then have two sons or two daughters with

the same name, but different origins.

If a child with an honorary name died, the next child of that gender received the name of the dead child. That’s why my great grandfather Nels had two brothers named Peter. The first brother died. The second brother was known as Peter Just, II.

Around the beginning of the nineteenth century, the names had become so hybridized that only about two dozen were being used for first and for last names for both males and females. There could be half-a-dozen Ole Larsens or Karen Marie Jensens in the same parish, and in every parish across the country. The Danes were in a naming rut.

The Danish government decided to do something about this. In 1812 they passed a law requiring families to choose a fixed surname that future generations would continue to use. It took a while for everyone to comply. City dwellers followed the law first. Country dwellers were slower to adopt the new system. As people adhered to the law, fixating their name, most of them kept the name listed on the church books of the time.

So who fixated to the name Just? It seemed to begin in Nels’ father’s generation. He was born in 1816, shortly after the governmental edict went into effect. He was called Peder Andersen Just, yet he had three sisters carrying the name Andersdatter and a brother who went by Andersen. Nels himself had four brothers with the last name of Just, three with the last name of

Pedersen, and a sister with the last name of Pedersen. Several of them also had middle names that were referential to previous generations.

It could have been worse. Prior to the patronymic naming system, people had one name and a descriptor of some sort. Erik had red hair so he became “Erik the Red.” William was the last conqueror of England, so his descriptive name became “William the Conqueror.” If we still used that convention, I’d probably be known today as “Rick the Schnauzer Friend.”

One final note that will do absolutely no good, but which I cannot resist adding. For seventy plus years people I’m introduced to are delighted to discover, each for the first time, that in a roll call of names, I am Just Rick. Yes, it’s hilarious and, yes, I’ve heard it 27,314 times. Forgive me if I don’t roll on the floor with laughter. If you find me in a good mood, I’ll give you a tight little smile that hides most of my teeth.

On August 15, we’ll be hosting an open house at the home Nels and Emma built in 1887. It made the National Register of Historic Places last year. More details on that are available here.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August While most of the family stories I tell this month will have a solid Idaho connection, some will be background about the family before our ancestors got here in 1863. This story, and the two following it, are such background.

There has always been some confusion in the Just family about our surname. Nels Just’s father was named Peder (or Peter, in the English spelling) Anderson Just. Some argue that he actually went by Anderson. His father’s name was Anders Justsen, and HIS father’s name was Just Pedersen. What’s up with that? Is Just even a “real” name? Let me enlighten and confuse you.

A couple of centuries ago, Danish people did not have last names or surnames as we know them. They used a system called patronymics, instead. In this naming system, a male child’s patronymic or “efternavn” (English translation: “after name”) was formed from his father’s first name plus – sen (English translation – “son”). Since Just Pedersen’s boy was a “son of Just,” his name was recorded as Just’s sen thus “JUSTSEN.” This is why Anders Justsen had the JUSTSEN “after name.” He was Just’s son. A female child’s patronymic was formed from her father’s first name plus – datter (daughter) and so, a Just girl was “Just’s daughter,” her name was recorded as Ann JUSTDATTER. The Danes dropped the possessive in the patronymic, which is why there is only one “s” in Justsen and Pedersen.

To confuse things even further, the first two male children often received the paternal and maternal grandparents’ names, respectively, to honor their ancestors. If both grandfathers or both grandmothers had the same name (which was not unusual) and if at least two boys or two girls were born to the parents, the family would then have two sons or two daughters with

the same name, but different origins.

If a child with an honorary name died, the next child of that gender received the name of the dead child. That’s why my great grandfather Nels had two brothers named Peter. The first brother died. The second brother was known as Peter Just, II.

Around the beginning of the nineteenth century, the names had become so hybridized that only about two dozen were being used for first and for last names for both males and females. There could be half-a-dozen Ole Larsens or Karen Marie Jensens in the same parish, and in every parish across the country. The Danes were in a naming rut.

The Danish government decided to do something about this. In 1812 they passed a law requiring families to choose a fixed surname that future generations would continue to use. It took a while for everyone to comply. City dwellers followed the law first. Country dwellers were slower to adopt the new system. As people adhered to the law, fixating their name, most of them kept the name listed on the church books of the time.

So who fixated to the name Just? It seemed to begin in Nels’ father’s generation. He was born in 1816, shortly after the governmental edict went into effect. He was called Peder Andersen Just, yet he had three sisters carrying the name Andersdatter and a brother who went by Andersen. Nels himself had four brothers with the last name of Just, three with the last name of

Pedersen, and a sister with the last name of Pedersen. Several of them also had middle names that were referential to previous generations.

It could have been worse. Prior to the patronymic naming system, people had one name and a descriptor of some sort. Erik had red hair so he became “Erik the Red.” William was the last conqueror of England, so his descriptive name became “William the Conqueror.” If we still used that convention, I’d probably be known today as “Rick the Schnauzer Friend.”

One final note that will do absolutely no good, but which I cannot resist adding. For seventy plus years people I’m introduced to are delighted to discover, each for the first time, that in a roll call of names, I am Just Rick. Yes, it’s hilarious and, yes, I’ve heard it 27,314 times. Forgive me if I don’t roll on the floor with laughter. If you find me in a good mood, I’ll give you a tight little smile that hides most of my teeth.

Published on August 01, 2021 16:00

July 31, 2021

Pop Quiz!

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture. If you missed that story, click the letter for a link.

1). What happened in Idaho in 1935 that involved peas?

A. The governor declared martial law and called out the national guard to break a pea picker strike.

B. Calvin Lamborn “invented” sugar snap peas

C. Peas were declared Idaho’s state vegetable

D. “Pea Picker” Tennessee Ernie Ford was born near Idaho City

E. All of the above

2). Which of the following is a billionaire born in Blackfoot?

A. J.R. Simplot

B. Frank VanderSloot

C. John Huntsman, Sr.

D. Joe Albertson

E. John Huntsman, Jr.

3). Idaho place names expert Lalia Boone was born where?

A. Firth, Idaho

B. Tehuacana, Texas.

C. Elk City, Idaho

D. Bastrop, Texas

E. Rigby, Idaho

4). What happened to 500 tons of ice near Driggs in 1929?

A. It broke off from a glacier on the Idaho side of the Tetons

B. It melted in a fire

C. It was stolen during the night

D. It was used to make ice sculptures

E. It was shipped to Chicago by mistake because of clerk’s error

5) Which of the following is UNTRUE about Cletus Leo Schwitters?

A. He sometimes went by the name Clete Lee

B. He worked as an announcer on KIDO radio

C. He sometimes went by the name Byron Keith

D. He was born in Boise, Idaho

E. He starred in a movie with Orson Welles Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

1, A

2, C

3, B

4, B

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). What happened in Idaho in 1935 that involved peas?

A. The governor declared martial law and called out the national guard to break a pea picker strike.

B. Calvin Lamborn “invented” sugar snap peas

C. Peas were declared Idaho’s state vegetable

D. “Pea Picker” Tennessee Ernie Ford was born near Idaho City

E. All of the above

2). Which of the following is a billionaire born in Blackfoot?

A. J.R. Simplot

B. Frank VanderSloot

C. John Huntsman, Sr.

D. Joe Albertson

E. John Huntsman, Jr.

3). Idaho place names expert Lalia Boone was born where?

A. Firth, Idaho

B. Tehuacana, Texas.

C. Elk City, Idaho

D. Bastrop, Texas

E. Rigby, Idaho

4). What happened to 500 tons of ice near Driggs in 1929?

A. It broke off from a glacier on the Idaho side of the Tetons

B. It melted in a fire

C. It was stolen during the night

D. It was used to make ice sculptures

E. It was shipped to Chicago by mistake because of clerk’s error

5) Which of the following is UNTRUE about Cletus Leo Schwitters?

A. He sometimes went by the name Clete Lee

B. He worked as an announcer on KIDO radio

C. He sometimes went by the name Byron Keith

D. He was born in Boise, Idaho

E. He starred in a movie with Orson Welles

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)1, A

2, C

3, B

4, B

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on July 31, 2021 04:00

July 30, 2021

A Baseball Great

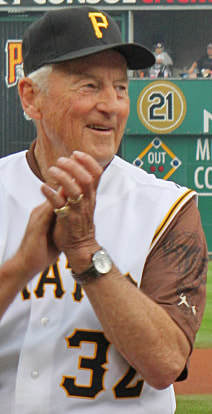

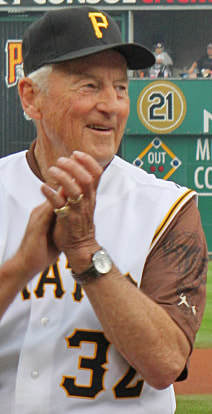

When you think of baseball players from Idaho, you might think of Harmon Kilibrew or Walter Johnson. Great players. But, don’t forget about Vern Law.

Born in Meridian, in 1930, Law first pitched in the majors for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1950. He played just one season, then left to serve in the military from 1951-1954. He returned to the Pirates and had his best year in 1960, when he won the Cy Young award and helped his team win the World Series against the New York Yankees. He was the winning pitcher in two series games.

An injury in 1963 forced him on to the voluntary retired list. In 1965, he was back on the mound, and received the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award as comeback player of the year. He left the game in 1967.

Law had a career win-loss record of 162-147. He had a 3.77 earned run average, and played in the All-Star game twice.

Law, who is LDS, got some ribbing for his devout beliefs. He was nicknamed “The Deacon” He was known for some great quotes, including “A winner never quits and a quitter never wins.”

Vern Law during the 1960 World Series anniversary celebration at PNC Park in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Vern Law during the 1960 World Series anniversary celebration at PNC Park in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Brock Fleeger on Flickr, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Common

Born in Meridian, in 1930, Law first pitched in the majors for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1950. He played just one season, then left to serve in the military from 1951-1954. He returned to the Pirates and had his best year in 1960, when he won the Cy Young award and helped his team win the World Series against the New York Yankees. He was the winning pitcher in two series games.

An injury in 1963 forced him on to the voluntary retired list. In 1965, he was back on the mound, and received the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award as comeback player of the year. He left the game in 1967.

Law had a career win-loss record of 162-147. He had a 3.77 earned run average, and played in the All-Star game twice.

Law, who is LDS, got some ribbing for his devout beliefs. He was nicknamed “The Deacon” He was known for some great quotes, including “A winner never quits and a quitter never wins.”

Vern Law during the 1960 World Series anniversary celebration at PNC Park in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Vern Law during the 1960 World Series anniversary celebration at PNC Park in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.Brock Fleeger on Flickr, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Common

Published on July 30, 2021 04:00

July 29, 2021

Mores Creek and More

Mores Creek is a tributary of the Boise River. Misspellings often find their way into place names, so it’s not surprising that it has also been known as Moore Creek and Moores Creek. J. Marion More, for whom the stream is named, used both last names himself, so the confusion is not surprising.

More was born John N. Moore in Tennessee in 1830. He carried his given name with him as he struck out for California when he was about 20. He settled in Mariposa where he became an undersheriff and was prominent in local Masonic affairs. Sometime in the late 1850s, Moore got into a “fracas” of some sort that was embarrassing enough that he skipped town, headed north to Washington Territory, and changed his name to John Marion More.

His past apparently forgotten, More was elected to the Washington Territorial Legislature in 1861 from Walla Walla. In 1862, stories of gold in eastern Oregon Territory enticed More and his friend, D.H. Fogus to the Boise Hills. More and Fogus were among the first miners to strike gold. More led a mining party that founded Idaho City on October 7, 1862. He staked some paying claims before heading back to Olympia to serve a second term in the Washington Territorial Legislature, where he was unsuccessful in pushing for the creation of a new territory east of the Cascades. Other interests prevailed in forming a territory with different boundaries, called Idaho Territory, on March 4, 1863.

More came back to the Boise Basin where his mines were doing well. He and Fogus bought controlling interest in the Oro Fino and Morning Star mines in Owyhee County. They pulled more than a million dollars from those operations within two years. Nevertheless, the bills caught up with the mine developers and they went bankrupt in 1866.

J. Marion More’s fortunes had again turned around by the spring of 1867. He had acquired a large interest in the Ida-Elmore properties atop War Eagle Mountain. An underground war had erupted between those working the Ida-Elmore and the Golden Chariot mines over the boundaries of those claims. More had been a key negotiator in bringing peace to the miners.

The agreement that brought the peace was not universally embraced by every miner. One Sam Lockhart, who had worked for the Golden Chariot, confronted More after the latter had been celebrating with alcohol and friends on the afternoon of April 1, 1868. Heated words were exchanged between Lockhart and More. More, according to Lockhart, had raised his cane as if to strike the miner. Lockhart pulled his gun and shot More in the chest.

Bullets flew back and forth. Lockhart took one to the shoulder. His friends drug More away to a local restaurant where he died three hours later.

Lockhart insisted that a man in More’s party fired the first shot. That became moot when gangrene set in, causing Lockhart to lose first his arm, then his life, a few weeks later.

According to Findagrave.com two stones mark J. Marion More’s grave, one spelling it More and one Moore. Oh, and the N. in his given name stood for Neptune.

More was born John N. Moore in Tennessee in 1830. He carried his given name with him as he struck out for California when he was about 20. He settled in Mariposa where he became an undersheriff and was prominent in local Masonic affairs. Sometime in the late 1850s, Moore got into a “fracas” of some sort that was embarrassing enough that he skipped town, headed north to Washington Territory, and changed his name to John Marion More.

His past apparently forgotten, More was elected to the Washington Territorial Legislature in 1861 from Walla Walla. In 1862, stories of gold in eastern Oregon Territory enticed More and his friend, D.H. Fogus to the Boise Hills. More and Fogus were among the first miners to strike gold. More led a mining party that founded Idaho City on October 7, 1862. He staked some paying claims before heading back to Olympia to serve a second term in the Washington Territorial Legislature, where he was unsuccessful in pushing for the creation of a new territory east of the Cascades. Other interests prevailed in forming a territory with different boundaries, called Idaho Territory, on March 4, 1863.

More came back to the Boise Basin where his mines were doing well. He and Fogus bought controlling interest in the Oro Fino and Morning Star mines in Owyhee County. They pulled more than a million dollars from those operations within two years. Nevertheless, the bills caught up with the mine developers and they went bankrupt in 1866.

J. Marion More’s fortunes had again turned around by the spring of 1867. He had acquired a large interest in the Ida-Elmore properties atop War Eagle Mountain. An underground war had erupted between those working the Ida-Elmore and the Golden Chariot mines over the boundaries of those claims. More had been a key negotiator in bringing peace to the miners.

The agreement that brought the peace was not universally embraced by every miner. One Sam Lockhart, who had worked for the Golden Chariot, confronted More after the latter had been celebrating with alcohol and friends on the afternoon of April 1, 1868. Heated words were exchanged between Lockhart and More. More, according to Lockhart, had raised his cane as if to strike the miner. Lockhart pulled his gun and shot More in the chest.

Bullets flew back and forth. Lockhart took one to the shoulder. His friends drug More away to a local restaurant where he died three hours later.

Lockhart insisted that a man in More’s party fired the first shot. That became moot when gangrene set in, causing Lockhart to lose first his arm, then his life, a few weeks later.

According to Findagrave.com two stones mark J. Marion More’s grave, one spelling it More and one Moore. Oh, and the N. in his given name stood for Neptune.

Published on July 29, 2021 04:00