Rick Just's Blog, page 122

June 29, 2021

Chautauquas had a Bit of Everything

Chautauquas in the Treasure Valley during the early part of the 20th Century offered so much education and entertainment that, described in today’s terms, they were Ted Talks, the Osher Institute, Toastmasters, Khan Academy, the Shakespeare Festival, Treefort, and the Cabin Readings and Conversations all rolled into one. Author Dick d’Easum wrote, “When Chautauqua was in flower it must be remembered that radio was in its infancy, television was unborn, and the automobile was a box mounted on punctures.”

These travelling congregations of culture were started by a Methodist minister, John Heyl Vincent, and a local businessman, Lewis Miller at Chautauqua Lake, New York in 1874. It began as an outdoor summer school for Sunday school teachers. With those religious roots, it’s not surprising that many Chautauquas had religious elements, and were sometimes sponsored by various denominations. Most had ample entertainment and educational opportunities for those with more secular tastes.

Best known for their temporary manifestations, Chautauquas could be almost anything in a community. Chautauqua Circle women’s clubs popped up around the country to discuss books and better themselves in order to change the world. Inmates started Chautauqua Societies in prison for self-improvement.

Travelling Chautauquas operated much like a circus sideshow, rolling into town with massive tents and the accoutrements of speakers, musicians, and entertainers. In smaller towns they would stay a day or two. In larger towns, they were usually the center of attention for a week.

The first Idaho State Chautauqua took place in Boise in 1910. It lasted nine days. In the buildup to the event promoters extolled the quality of the speakers and the variety of entertainment. Sometimes calling it “the people’s university,” they described three divisions of each day.

The morning section would feature classes and schools, mostly designed around the domestic sciences and agriculture, but also including athletic instruction, discussions about literature and history, as well as bible classes. The University of Idaho supplied many of the instructors. In the afternoon the heavier lectures for book lovers and those seeking knowledge took place. The evening was a time for entertainment from musical acts and theater companies.

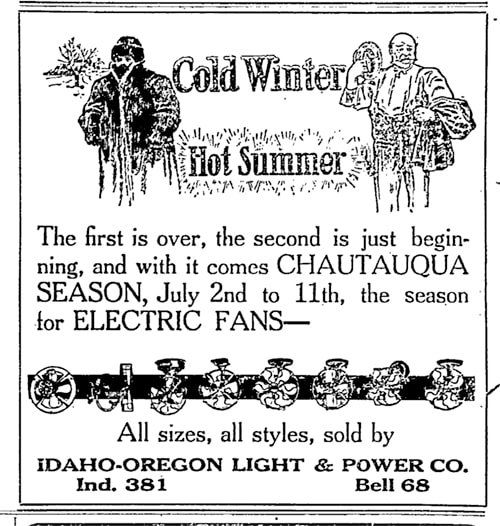

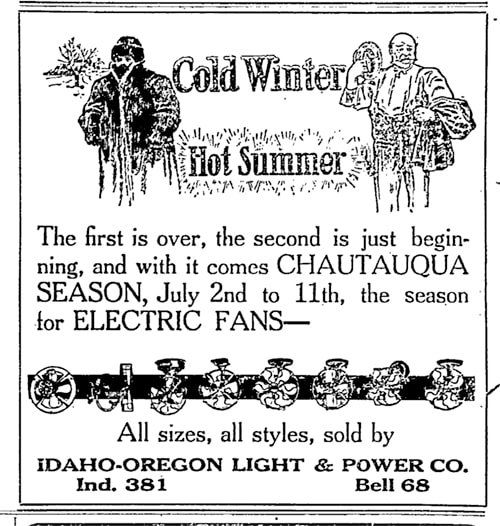

As the event—encompassing July 4—grew nearer, local businesses began to promote it to their own benefit. Tie-ins sold everything from lace curtains to building lots to flour with specials during Chautauqua.

The main speaker of the Chautauqua was to be Idaho Senator W.E. Borah, but there was speculation about who else might show up at the last minute. William Jennings Bryan was among the most popular speakers at such events across the country. Another was Dr. Russell Conwell, famous for his “Acres of Diamonds” speech, the point of which was that one could seek fortune far and wide yet miss the acres of diamonds in one’s own backyard. He delivered it more than 5,000 times.

The Chautauqua included ball games, cavalry drills, chalk art exhibitions, fireworks, readings, fashion shows, concerts, political speeches, exhibits, and more. The Chinese community in Boise was joyful because they were able to procure a “monster dragon” to wind along the parade route on the Fourth of July.

One feature of the celebration visible at the major entertainment venues was the Chautauqua salute. The waving of white handkerchiefs was a tradition that had grown from an event years earlier at the suggestion that a deaf speaker could not hear the applause of a crowd. Since almost everyone carried a white handkerchief, the resulting flutter was a glorious sight.

Chautauquas thrived in Idaho and elsewhere for a few more years, waning in the mid-twenties only as other forms of entertainment, especially radio, came to the forefront.

The end of the Chautauquas was perhaps foreshadowed in 1925 in Boise when former baseball player turned evangelist Billy Sunday deplored the rise of jazz music. Later, in that same tent, a Boise audience clapped “until their hands were sore” for a jazz performance. Many advertisers looked for a tie-in with Chautauqua, no matter how remote.

Many advertisers looked for a tie-in with Chautauqua, no matter how remote.

These travelling congregations of culture were started by a Methodist minister, John Heyl Vincent, and a local businessman, Lewis Miller at Chautauqua Lake, New York in 1874. It began as an outdoor summer school for Sunday school teachers. With those religious roots, it’s not surprising that many Chautauquas had religious elements, and were sometimes sponsored by various denominations. Most had ample entertainment and educational opportunities for those with more secular tastes.

Best known for their temporary manifestations, Chautauquas could be almost anything in a community. Chautauqua Circle women’s clubs popped up around the country to discuss books and better themselves in order to change the world. Inmates started Chautauqua Societies in prison for self-improvement.

Travelling Chautauquas operated much like a circus sideshow, rolling into town with massive tents and the accoutrements of speakers, musicians, and entertainers. In smaller towns they would stay a day or two. In larger towns, they were usually the center of attention for a week.

The first Idaho State Chautauqua took place in Boise in 1910. It lasted nine days. In the buildup to the event promoters extolled the quality of the speakers and the variety of entertainment. Sometimes calling it “the people’s university,” they described three divisions of each day.

The morning section would feature classes and schools, mostly designed around the domestic sciences and agriculture, but also including athletic instruction, discussions about literature and history, as well as bible classes. The University of Idaho supplied many of the instructors. In the afternoon the heavier lectures for book lovers and those seeking knowledge took place. The evening was a time for entertainment from musical acts and theater companies.

As the event—encompassing July 4—grew nearer, local businesses began to promote it to their own benefit. Tie-ins sold everything from lace curtains to building lots to flour with specials during Chautauqua.

The main speaker of the Chautauqua was to be Idaho Senator W.E. Borah, but there was speculation about who else might show up at the last minute. William Jennings Bryan was among the most popular speakers at such events across the country. Another was Dr. Russell Conwell, famous for his “Acres of Diamonds” speech, the point of which was that one could seek fortune far and wide yet miss the acres of diamonds in one’s own backyard. He delivered it more than 5,000 times.

The Chautauqua included ball games, cavalry drills, chalk art exhibitions, fireworks, readings, fashion shows, concerts, political speeches, exhibits, and more. The Chinese community in Boise was joyful because they were able to procure a “monster dragon” to wind along the parade route on the Fourth of July.

One feature of the celebration visible at the major entertainment venues was the Chautauqua salute. The waving of white handkerchiefs was a tradition that had grown from an event years earlier at the suggestion that a deaf speaker could not hear the applause of a crowd. Since almost everyone carried a white handkerchief, the resulting flutter was a glorious sight.

Chautauquas thrived in Idaho and elsewhere for a few more years, waning in the mid-twenties only as other forms of entertainment, especially radio, came to the forefront.

The end of the Chautauquas was perhaps foreshadowed in 1925 in Boise when former baseball player turned evangelist Billy Sunday deplored the rise of jazz music. Later, in that same tent, a Boise audience clapped “until their hands were sore” for a jazz performance.

Many advertisers looked for a tie-in with Chautauqua, no matter how remote.

Many advertisers looked for a tie-in with Chautauqua, no matter how remote.

Published on June 29, 2021 02:00

June 27, 2021

The Pocatello

This is the US Naval Frigate Pocatello, a patrol frigate that completed a dozen patrols west of Seattle during WWII. Three things are of interest about the otherwise prosaic history of the vessel. First, she was named after the City of Pocatello, Idaho. You may have surmised that. It wasn’t so clear in the AP report about her christening that appeared in the October 18, 1943, edition of the Idaho Statesman. That story had the boat being named for Chief Pocatello, not the city. Since the city was named after Chief Pocatello it is probably a moot point.

The Pocatello was launched from the Kaiser Shipyard in Richmond, California, which leads to the second point of interest. As the AP story reported, “Miss Thelma Dixey, 17, now of Oroville, Calif., sponsored the vessel. She was the granddaughter of Ralph Dixey, prominent Fort Hall Indian and great granddaughter of Chief Pocatello who headed the Shoshone Tribe.

“Miss Dixey swung lustily with the champagne bottle as the ship slid into the waters of San Francisco Bay.

The final item of some interest is that the XO, or executive officer of the ship was Buddy Ebsen, who served aboard the Pocatello until she was decommissioned in 1946. Ebsen was a dancer and actor who appeared in many movies, including Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and became best known for his roles as Jed Clampett in The Beverly Hillbillies , and the title character in the TV series Barnaby Jones.

No word on whether or not he ever visited Pocatello.

The Pocatello was launched from the Kaiser Shipyard in Richmond, California, which leads to the second point of interest. As the AP story reported, “Miss Thelma Dixey, 17, now of Oroville, Calif., sponsored the vessel. She was the granddaughter of Ralph Dixey, prominent Fort Hall Indian and great granddaughter of Chief Pocatello who headed the Shoshone Tribe.

“Miss Dixey swung lustily with the champagne bottle as the ship slid into the waters of San Francisco Bay.

The final item of some interest is that the XO, or executive officer of the ship was Buddy Ebsen, who served aboard the Pocatello until she was decommissioned in 1946. Ebsen was a dancer and actor who appeared in many movies, including Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and became best known for his roles as Jed Clampett in The Beverly Hillbillies , and the title character in the TV series Barnaby Jones.

No word on whether or not he ever visited Pocatello.

Published on June 27, 2021 04:00

June 26, 2021

That Tree May Not be Dead

It's a shame to look at a hillside covered with dead pine trees. You wonder what got them...fire, insects, disease? Sometimes it's difficult to tell. And sometimes, though they look it, they're not dead at all.

Many of us can't tell one type of tree from another. There are so many different kinds. About the only thing we're sure of is that trees with leaves lose them during the winter, and trees with needles keep them year around. That’s an easy rule... until you run across a tamarack.

The western larch, Larix laricina, or tamarack, has needles. Most people would call it a pine tree. But it does the strangest thing in the fall. The tamarack turns orange, or brilliant yellow, then drops its needles.

Tamarack is often mixed in with ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, and lodgepole pine. In the fall the brilliant trees stand out like a scattering of glowing candles among the evergreens.

You can see tamaracks around McCall, in the Little Salmon River country, along the Clearwater River, and many places in northern Idaho. There's a whole hillside due south of New Meadows that is almost covered with tamarack. That's appropriate, because the tiny settlement of Tamarack, Idaho is not far away.

Tamarack wood is heavy and dense. It's often used for utility poles, fence posts, and mine timbers. It doesn't work well in building concrete forms, though. The wood contains a sugar that keeps concrete from curing.

The elves at Wikipedia tell us that the word tamarack is the Algonquian name for the species and means "wood used for snowshoes."

Many of us can't tell one type of tree from another. There are so many different kinds. About the only thing we're sure of is that trees with leaves lose them during the winter, and trees with needles keep them year around. That’s an easy rule... until you run across a tamarack.

The western larch, Larix laricina, or tamarack, has needles. Most people would call it a pine tree. But it does the strangest thing in the fall. The tamarack turns orange, or brilliant yellow, then drops its needles.

Tamarack is often mixed in with ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, and lodgepole pine. In the fall the brilliant trees stand out like a scattering of glowing candles among the evergreens.

You can see tamaracks around McCall, in the Little Salmon River country, along the Clearwater River, and many places in northern Idaho. There's a whole hillside due south of New Meadows that is almost covered with tamarack. That's appropriate, because the tiny settlement of Tamarack, Idaho is not far away.

Tamarack wood is heavy and dense. It's often used for utility poles, fence posts, and mine timbers. It doesn't work well in building concrete forms, though. The wood contains a sugar that keeps concrete from curing.

The elves at Wikipedia tell us that the word tamarack is the Algonquian name for the species and means "wood used for snowshoes."

Published on June 26, 2021 04:00

June 25, 2021

English Teachers won't be Happy

Idaho became a state in 1890. Idahoans disagree on countless things, but there is probably near universal agreement about the name of the state. It’s important that we agree on the names of things. Imagine how confusing it would be if half the citizens of Arco called it by its original name, Root Hog. With apologies to The Lovin’ Spoonful, someone has to finally decide.

The standardization of names was why the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (USBGN) was created, coincidentally the same year as the state of Idaho. Its charge is to “maintain uniform geographic names usage throughout the Federal Government.” The Board makes sure things are spelled consistently on maps and that two mountains in the same range don’t have the same name.

Driving English majors crazy is also, seemingly, part of the charge of the USBGN. This comes about because of the institution’s phobia about apostrophes. Since its inception, the USBGN has abhorred apostrophes, particularly discouraging the use of possessive apostrophes. That’s why Glenns Ferry is not Glenn’s Ferry and the Henrys Fork is not the Henry’s Fork.

There is nothing in the Board’s archives indicating why they discouraged the use of apostrophes. They do try to justify it in… words. Here you go: “The word or words that form a geographic name change their connotative function and together become a single denotative unit. They change from words having specific dictionary meaning to fixed labels used to refer to geographic entities. The need to imply possession or association no longer exists.”

You’re allowed to read that again, if you like.

The takeaway is that the USBGN is adamant that possessive apostrophes are not used in the many thousands of names scattered on United States maps. But, as with the old rule of grammar, “I after E, except after C,” there are a few exceptions. Five, to be exact.

Martha’s Vineyard and its otherwise offensive apostrophe was approved in 1933 after an extensive local campaign. Ike’s Point in New Jersey was approved in 1944 because “it would be unrecognizable otherwise.” In 1963, John E’s Pond got the nod of approval because it would be confused with John S Pond. Note the lack of a period in John S Pond. The USBGN doesn’t like periods, either. Carlos Elmer’s Joshua View was approved in 1995 at the request of the Arizona State Board on Geographic and Historic Names, because “otherwise three apparently given names in succession would dilute the meaning.” In this case Joshua refers to a stand of trees. Finally, Clark’s Mountain in Oregon got to keep its apostrophe in 2002 to “correspond with the personal references of Lewis and Clark.”

Alert readers will have already noted that there is an apostrophe used often in Idaho places names. That one is in the middle of Coeur d’Alene when it refers to the city, the lake, the valley, the tribal reservation, the mountain, the mountain range, and the river. It’s not a possessive apostrophe, so USBGN lets it live.

Postal officials also put the kibosh on certain names. For instance, there is only one city named Eagle in Idaho, though not for a lack of trying. The citizens of a little town south of Sandpoint wanted to call their home Eagle in 1900. To avoid confusion, the postal bureaucracy said no. The citizens in a spate of creativity just changed the E to an S on the post office application form and Sagle was born.

The standardization of names was why the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (USBGN) was created, coincidentally the same year as the state of Idaho. Its charge is to “maintain uniform geographic names usage throughout the Federal Government.” The Board makes sure things are spelled consistently on maps and that two mountains in the same range don’t have the same name.

Driving English majors crazy is also, seemingly, part of the charge of the USBGN. This comes about because of the institution’s phobia about apostrophes. Since its inception, the USBGN has abhorred apostrophes, particularly discouraging the use of possessive apostrophes. That’s why Glenns Ferry is not Glenn’s Ferry and the Henrys Fork is not the Henry’s Fork.

There is nothing in the Board’s archives indicating why they discouraged the use of apostrophes. They do try to justify it in… words. Here you go: “The word or words that form a geographic name change their connotative function and together become a single denotative unit. They change from words having specific dictionary meaning to fixed labels used to refer to geographic entities. The need to imply possession or association no longer exists.”

You’re allowed to read that again, if you like.

The takeaway is that the USBGN is adamant that possessive apostrophes are not used in the many thousands of names scattered on United States maps. But, as with the old rule of grammar, “I after E, except after C,” there are a few exceptions. Five, to be exact.

Martha’s Vineyard and its otherwise offensive apostrophe was approved in 1933 after an extensive local campaign. Ike’s Point in New Jersey was approved in 1944 because “it would be unrecognizable otherwise.” In 1963, John E’s Pond got the nod of approval because it would be confused with John S Pond. Note the lack of a period in John S Pond. The USBGN doesn’t like periods, either. Carlos Elmer’s Joshua View was approved in 1995 at the request of the Arizona State Board on Geographic and Historic Names, because “otherwise three apparently given names in succession would dilute the meaning.” In this case Joshua refers to a stand of trees. Finally, Clark’s Mountain in Oregon got to keep its apostrophe in 2002 to “correspond with the personal references of Lewis and Clark.”

Alert readers will have already noted that there is an apostrophe used often in Idaho places names. That one is in the middle of Coeur d’Alene when it refers to the city, the lake, the valley, the tribal reservation, the mountain, the mountain range, and the river. It’s not a possessive apostrophe, so USBGN lets it live.

Postal officials also put the kibosh on certain names. For instance, there is only one city named Eagle in Idaho, though not for a lack of trying. The citizens of a little town south of Sandpoint wanted to call their home Eagle in 1900. To avoid confusion, the postal bureaucracy said no. The citizens in a spate of creativity just changed the E to an S on the post office application form and Sagle was born.

Published on June 25, 2021 04:00

June 24, 2021

The Capitol's Vault Doors

There are many beautiful doors in Idaho’s statehouse. Most are wooden, many with glass or frosted glass windows in the upper half. Two, though, are unique. To enter certain offices in the Idaho Capitol, you step through the openings of door-sized safes. The gleaming steel doors with hefty metal latches, knurled knobs, and gold-leaf lettering once protected the state’s treasury back when physical money from tax revenues was kept there before finding its way to the bank.

There is little need for enormous vaults to protect cash anymore, but when the renovated statehouse was reopened to the public in 2010 we found that those historical doors—minor treasures in themselves—had been retained.

There is little need for enormous vaults to protect cash anymore, but when the renovated statehouse was reopened to the public in 2010 we found that those historical doors—minor treasures in themselves—had been retained.

Published on June 24, 2021 04:00

June 23, 2021

The Sampson Roads

Tourism professionals often lament that there are not better signs on our roads. Charlie Sampson thought the same thing back in 1914, and he did something about it.

Sampson ran the Sampson Music Company in Boise. One day, while making a delivery in the desert south of town, Charlie got lost. That annoyed him. He thought there should be signs along the roads so travelers could find their way. He took that suggestion to local officials. They ignored him. To their surprise, Sampson proved that he was not one to let a good idea die. He began to mark the roads around Boise himself.

Sampson carried a bucket of orange paint with him wherever he went, and painted signs on rocks, trees, barns, bridges, fences... just about anything that didn't move. The routes he marked became known locally as the Sampson Trails. Of course, many of the larger signs also included a few words about the Sampson Music Company.

Sampson became such a believer in his markers that he hired a three-man crew to keep the signs in shape. He spent thousands of dollars on the project.

In 1933 the Bureau of Highways decided to put a stop to Sampson's signing. They claimed it defaced the landscape. It probably did, but the Idaho Legislature didn't buy that argument. They passed a resolution commending Sampson for his efforts and giving him the right to continue marking the Sampson Trails.

Charlie Sampson died in 1935, leaving the task of guiding people along the roadways to others. One of those people is Cort Conley. His book, Idaho for the Curious , from which the story of Charlie Sampson was taken, is probably the best guide available for travelers interested in Idaho history.

The photo showing one of Sampson’s orange dots is from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Sampson ran the Sampson Music Company in Boise. One day, while making a delivery in the desert south of town, Charlie got lost. That annoyed him. He thought there should be signs along the roads so travelers could find their way. He took that suggestion to local officials. They ignored him. To their surprise, Sampson proved that he was not one to let a good idea die. He began to mark the roads around Boise himself.

Sampson carried a bucket of orange paint with him wherever he went, and painted signs on rocks, trees, barns, bridges, fences... just about anything that didn't move. The routes he marked became known locally as the Sampson Trails. Of course, many of the larger signs also included a few words about the Sampson Music Company.

Sampson became such a believer in his markers that he hired a three-man crew to keep the signs in shape. He spent thousands of dollars on the project.

In 1933 the Bureau of Highways decided to put a stop to Sampson's signing. They claimed it defaced the landscape. It probably did, but the Idaho Legislature didn't buy that argument. They passed a resolution commending Sampson for his efforts and giving him the right to continue marking the Sampson Trails.

Charlie Sampson died in 1935, leaving the task of guiding people along the roadways to others. One of those people is Cort Conley. His book, Idaho for the Curious , from which the story of Charlie Sampson was taken, is probably the best guide available for travelers interested in Idaho history.

The photo showing one of Sampson’s orange dots is from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on June 23, 2021 04:00

June 22, 2021

The Great Train Escape

As villains go John Gideon barely qualified. He didn’t kill anyone; he didn’t even hurt anyone. His claim to fame was that he probably participated in one of the heaviest heists of any Idaho bad guy. And that wasn’t even in Idaho.

With a biblical surname and an employee of a mine called the Golden Rule, he really should have been a more upstanding citizen. It was the golden part of that mine name that caused his downfall, as it does so many.

In July 1905, a single bandit held up the Meadows-Warren stage. Hoping not to be recognized, the robber covered his entire face with a kerchief, not even bothering with eyeholes. The weave of the cloth was probably loose enough for him to see out without witness eyes seeing in well enough to identify him. To complete his outfit, the man brandished a mismatched pair of pistols.

The highwayman demanded that the driver of the coach “throw down the sack.” Pretending not to understand precisely what the bandit was after; the driver threw down a sack filled with bottles. This not being the exact sack the outlaw wanted, he specified that it was the registered mail bag that interested him. The driver reluctantly tossed that to the ground, at which point the bandit told him to jump down and open it.

Once the contents were revealed, the bandit signaled for the stage to move on down the road.

The robber made off with $300 in cash and $1,200 in gold, most of the latter being the property of the Golden Rule operation. That would be the equivalent of about $40,000 today.

John Gideon did not wait a tick to start spending money fast enough to draw suspicion onto himself. No one could identify the bandit, but they had little trouble identifying a shirt and pistols found in Gideon’s possession.

Many men in Idaho’s criminal history paid for murder with a few years in jail. Gideon paid a little more for the theft of gold and currency. Robbing the mail is and was a federal offense. He was convicted of the crime and given a life sentence.

Following the trial, which took place in federal court in Moscow, Gideon came close to a moment of excitement. He confided in a cellmate that he had committed the crime, but he didn’t intend to pay for it. He planned to stomp the leg of the federal marshal assigned to transport him to prison at McNeill’s Island in the Puget Sound, a federal facility. It was a real threat because Gideon would be wearing an Oregon Boot on his foot. That was an iron device designed to make escape more difficult. It was heavy enough to break the bone of a man who might drop his guard. Fortunately, the cellmate told the story before the train left with Gideon, making the marshal sufficiently leery of that booted foot.

After spending about a year in the lockup at McNeill’s Island, Gideon was transferred to the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. It was there that he found another day or two of fame.

On April 21, 1910, Gideon and five coconspirators overpowered a locomotive crew to make an escape. A switch engine was in the prison yard—probably not an uncommon occurrence, there being tracks to facilitate that. Using pistols carved for the occasion to look real, they pressed the barrels of the faux weapons into the necks of crew members. The engineer, valuing his life appropriately, crashed the steam engine through the closed prison gates.

The prisoners were not well-acquainted with train schedules, so did not know when or if an oncoming train might slam into them. One-by-one they jumped off the roaring train. They hadn’t gone more than a mile. All but one of them, including Gideon, were captured within a matter of hours.

The bold escape made headlines across the country, failed though it ultimately was. Perhaps the fame gave Gideon some satisfaction, though it clearly did not make up for a life in prison. He became, as they say, a model prisoner. In 1920, John Gideon walked away from the prison farm where he was working, never to be heard from again.

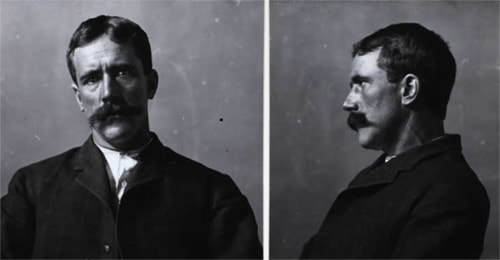

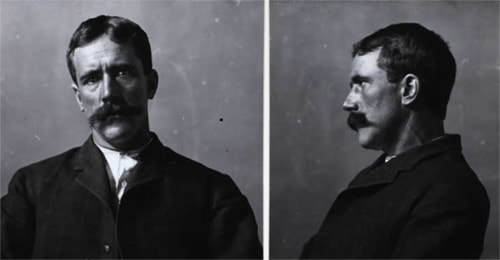

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

With a biblical surname and an employee of a mine called the Golden Rule, he really should have been a more upstanding citizen. It was the golden part of that mine name that caused his downfall, as it does so many.

In July 1905, a single bandit held up the Meadows-Warren stage. Hoping not to be recognized, the robber covered his entire face with a kerchief, not even bothering with eyeholes. The weave of the cloth was probably loose enough for him to see out without witness eyes seeing in well enough to identify him. To complete his outfit, the man brandished a mismatched pair of pistols.

The highwayman demanded that the driver of the coach “throw down the sack.” Pretending not to understand precisely what the bandit was after; the driver threw down a sack filled with bottles. This not being the exact sack the outlaw wanted, he specified that it was the registered mail bag that interested him. The driver reluctantly tossed that to the ground, at which point the bandit told him to jump down and open it.

Once the contents were revealed, the bandit signaled for the stage to move on down the road.

The robber made off with $300 in cash and $1,200 in gold, most of the latter being the property of the Golden Rule operation. That would be the equivalent of about $40,000 today.

John Gideon did not wait a tick to start spending money fast enough to draw suspicion onto himself. No one could identify the bandit, but they had little trouble identifying a shirt and pistols found in Gideon’s possession.

Many men in Idaho’s criminal history paid for murder with a few years in jail. Gideon paid a little more for the theft of gold and currency. Robbing the mail is and was a federal offense. He was convicted of the crime and given a life sentence.

Following the trial, which took place in federal court in Moscow, Gideon came close to a moment of excitement. He confided in a cellmate that he had committed the crime, but he didn’t intend to pay for it. He planned to stomp the leg of the federal marshal assigned to transport him to prison at McNeill’s Island in the Puget Sound, a federal facility. It was a real threat because Gideon would be wearing an Oregon Boot on his foot. That was an iron device designed to make escape more difficult. It was heavy enough to break the bone of a man who might drop his guard. Fortunately, the cellmate told the story before the train left with Gideon, making the marshal sufficiently leery of that booted foot.

After spending about a year in the lockup at McNeill’s Island, Gideon was transferred to the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. It was there that he found another day or two of fame.

On April 21, 1910, Gideon and five coconspirators overpowered a locomotive crew to make an escape. A switch engine was in the prison yard—probably not an uncommon occurrence, there being tracks to facilitate that. Using pistols carved for the occasion to look real, they pressed the barrels of the faux weapons into the necks of crew members. The engineer, valuing his life appropriately, crashed the steam engine through the closed prison gates.

The prisoners were not well-acquainted with train schedules, so did not know when or if an oncoming train might slam into them. One-by-one they jumped off the roaring train. They hadn’t gone more than a mile. All but one of them, including Gideon, were captured within a matter of hours.

The bold escape made headlines across the country, failed though it ultimately was. Perhaps the fame gave Gideon some satisfaction, though it clearly did not make up for a life in prison. He became, as they say, a model prisoner. In 1920, John Gideon walked away from the prison farm where he was working, never to be heard from again.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

Published on June 22, 2021 04:00

June 21, 2021

Sandblasting History

In downtown Boise, there is a doorway over which two words carved in stone have been sandblasted away. The words Boise Turnverein stretched above the arched entrance of the building at Sixth and Main from 1906 until 1915, proclaiming it the home of the German-American social club. If the light is just right, you can still read them.

The Turner movement started in Germany in the 19th Century as a way to promote good health through “turnen,” which in German is the practice of gymnastics. Turner societies started in most cities in the United States where a substantial German population resided.

In Boise, the Turn Verein and Harmonia Society started in 1870. Its first president was John Lemp, one of Boise’s best-known brewers. The Turners, athletic as their origins might have been, were also big fans of beer. The social side of the organization prevailed over gymnastics.

For the first few years the society sponsored events in Slocum Hall and the Masonic Hall, but by 1874, they had moved to the first Turn Verein Hall at 6th and Main. They frequently sponsored balls and theatrical events for the community and rented space for numerous community events. The Idaho Territorial Legislature met in the building in 1878, 1882, and 1884.

In 1875, the Fourth of July festivities in Boise were held under the auspices of the Turn Verein Society. The Turners marched proudly in the parade, carrying the flag of Germany. That the observance that year took place on July 5 made it no less of a celebration. The Fourth of July was on a Sunday, so the merriment was moved to Monday to assure that any incidental drinking that might accompany the festivities would not take place on the sabbath.

The Turners were a big part of Boise’s social order for decades. By 1904 their future was looking rosy enough to contract with Tourtellotte & Co to design a new meeting and event space at Sixth and Main. The contract for construction of the new building was let in April 1906. The Turners laid the cornerstone in elaborate ceremonies that included multiple speeches and musical numbers on August 1, 1906. Similar ceremonies marked the dedication of the completed building in December of that year.

The new Boise Turnverein was a two-story red brick building that featured an auditorium with a balcony, a billiard room, a parlor for lady guests, and a gym with showers. At some point, early in its history, the building held a drinking establishment called the Irrigator Bar, the first of many bars that would have that 6th and Main address.

The Turnverein served as a community theater and venue for balls for the next several years, at least until 1915. That was when international affairs, namely a war started by Germany, began to make the Turners uncomfortable with being in the limelight.

A small notice in the Idaho Statesman on February 8, 1916, said that the Turnverein Society of Boise had sold the property to Amelia Sonna for “$1 and other valuable considerations.” The Turnvereins had disbanded.

The Seventh Day Adventist church purchased the building in 1917, eventually converting it to a school. It would become a federal aviation control center in the 1950s and a printing business in the 60s. Since then, the building has served as the home of many restaurants and nightclubs, from the Old Boise Saloon, through Joe’s American Grill, Dirty Little Roddy’s, and China Blue.

The name over the door, Boise Turnverein, was sandblasted away by the Turners themselves before they sold the building and disbanded. But it did not wipe away the history. Today, it is still known as the Turnverein Building.

Turnverein members at the dedication of the Boise Turnverein building in 1906. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Turnverein members at the dedication of the Boise Turnverein building in 1906. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  If the light is right you can still make out Boise Turnverein over the entrance to the building today.

If the light is right you can still make out Boise Turnverein over the entrance to the building today.

The Turner movement started in Germany in the 19th Century as a way to promote good health through “turnen,” which in German is the practice of gymnastics. Turner societies started in most cities in the United States where a substantial German population resided.

In Boise, the Turn Verein and Harmonia Society started in 1870. Its first president was John Lemp, one of Boise’s best-known brewers. The Turners, athletic as their origins might have been, were also big fans of beer. The social side of the organization prevailed over gymnastics.

For the first few years the society sponsored events in Slocum Hall and the Masonic Hall, but by 1874, they had moved to the first Turn Verein Hall at 6th and Main. They frequently sponsored balls and theatrical events for the community and rented space for numerous community events. The Idaho Territorial Legislature met in the building in 1878, 1882, and 1884.

In 1875, the Fourth of July festivities in Boise were held under the auspices of the Turn Verein Society. The Turners marched proudly in the parade, carrying the flag of Germany. That the observance that year took place on July 5 made it no less of a celebration. The Fourth of July was on a Sunday, so the merriment was moved to Monday to assure that any incidental drinking that might accompany the festivities would not take place on the sabbath.

The Turners were a big part of Boise’s social order for decades. By 1904 their future was looking rosy enough to contract with Tourtellotte & Co to design a new meeting and event space at Sixth and Main. The contract for construction of the new building was let in April 1906. The Turners laid the cornerstone in elaborate ceremonies that included multiple speeches and musical numbers on August 1, 1906. Similar ceremonies marked the dedication of the completed building in December of that year.

The new Boise Turnverein was a two-story red brick building that featured an auditorium with a balcony, a billiard room, a parlor for lady guests, and a gym with showers. At some point, early in its history, the building held a drinking establishment called the Irrigator Bar, the first of many bars that would have that 6th and Main address.

The Turnverein served as a community theater and venue for balls for the next several years, at least until 1915. That was when international affairs, namely a war started by Germany, began to make the Turners uncomfortable with being in the limelight.

A small notice in the Idaho Statesman on February 8, 1916, said that the Turnverein Society of Boise had sold the property to Amelia Sonna for “$1 and other valuable considerations.” The Turnvereins had disbanded.

The Seventh Day Adventist church purchased the building in 1917, eventually converting it to a school. It would become a federal aviation control center in the 1950s and a printing business in the 60s. Since then, the building has served as the home of many restaurants and nightclubs, from the Old Boise Saloon, through Joe’s American Grill, Dirty Little Roddy’s, and China Blue.

The name over the door, Boise Turnverein, was sandblasted away by the Turners themselves before they sold the building and disbanded. But it did not wipe away the history. Today, it is still known as the Turnverein Building.

Turnverein members at the dedication of the Boise Turnverein building in 1906. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Turnverein members at the dedication of the Boise Turnverein building in 1906. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  If the light is right you can still make out Boise Turnverein over the entrance to the building today.

If the light is right you can still make out Boise Turnverein over the entrance to the building today.

Published on June 21, 2021 04:00

June 20, 2021

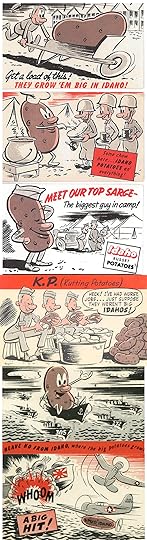

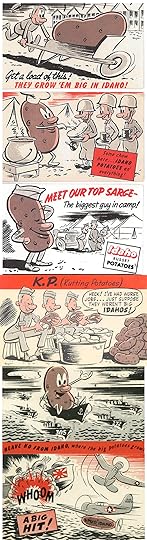

Farragut's Potato Postcards

Idaho has always been creative about its potatoes. The license plate slogan has been a big part of that, and there’s currently a huge potato on a big truck touring the country and attracting attention.

Did you know about the postcards? There have been big-potato-on-a-truck postcards for years, mostly produced by postcard companies. It was the Idaho Department of Agriculture that came up with a creative series of postcards to offer to those military folks who trained here during World War II. The top four below were aimed at those stationed at Gowen Field in Boise, and the bottom two were for the “boots” training at Farragut Naval Training Station.

The cards are all signed by the artist, “Hager.” And that’s all I know about him or her. Does anyone else out there know anything about this cartoonist?

Did you know about the postcards? There have been big-potato-on-a-truck postcards for years, mostly produced by postcard companies. It was the Idaho Department of Agriculture that came up with a creative series of postcards to offer to those military folks who trained here during World War II. The top four below were aimed at those stationed at Gowen Field in Boise, and the bottom two were for the “boots” training at Farragut Naval Training Station.

The cards are all signed by the artist, “Hager.” And that’s all I know about him or her. Does anyone else out there know anything about this cartoonist?

Published on June 20, 2021 04:00

June 19, 2021

Farragut Postcards

In yesterday’s post we looked at postcards that the Idaho Department of Agriculture made available to the “boots” at Farragut Naval Training Station during World War II. They all had a goofy potato theme and are popular with postcard collectors.

The Navy supplied postcards for the trainees at Farragut, too. They weren’t quite as colorful and didn’t feature any vegetables. The audio-visual department on the base, specifically Sp(P)3c Stan Gelling, produced them.

Boots could also buy a packet of black and white photos of base activities that they could send back home. No doubt the pictures were carefully staged to avoid giving any secrets away.

The Navy supplied postcards for the trainees at Farragut, too. They weren’t quite as colorful and didn’t feature any vegetables. The audio-visual department on the base, specifically Sp(P)3c Stan Gelling, produced them.

Boots could also buy a packet of black and white photos of base activities that they could send back home. No doubt the pictures were carefully staged to avoid giving any secrets away.

Published on June 19, 2021 04:00