Rick Just's Blog, page 125

May 29, 2021

Those Boise Fords

What town comes to mind when you think automobile manufacturing? Detroit? Dearborn? Boise?

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, is H.H. and M.B. Bryant’s Ford dealership in 1917. It was located at 1602 Main. But it wasn’t just an ordinary dealership. They put together Fords there for a time in 1914. H.H. was married to Henry Ford’s sister, so had a bit of an in.

Ford was famous for revolutionizing the industry with the assembly line process, beginning with the 1914 Model T. It’s not clear what advantage shipping pieces and parts to Boise for assembly had for Mr. Bryant, but he did put together cars in the capital city for a while.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, is H.H. and M.B. Bryant’s Ford dealership in 1917. It was located at 1602 Main. But it wasn’t just an ordinary dealership. They put together Fords there for a time in 1914. H.H. was married to Henry Ford’s sister, so had a bit of an in.

Ford was famous for revolutionizing the industry with the assembly line process, beginning with the 1914 Model T. It’s not clear what advantage shipping pieces and parts to Boise for assembly had for Mr. Bryant, but he did put together cars in the capital city for a while.

Published on May 29, 2021 04:00

May 28, 2021

Idaho's Favorite Roadside Signs

Farris Lind was a crop duster, but he didn’t get his nickname, “Fearless,” for flying the farms with the most dangerous turns. He just liked the alliteration when he heard about Fearless Fosdick. Lind also served as WWII flight instructor.

He ran his first gas station in 1936 when he was only 20. That one was in Twin Falls.

After returning from service in WWII, Lind thought up a way to make his Boise service station famous. He scattered humorous signs all over southern Idaho to perk up drivers bored with many miles of sagebrush. One side advertised his growing number of Stinker Stations, while the other side offered humor, such as, in a field of lava rock (melon gravel left over from the Bonneville Flood), “Petrified watermelon. Take one home to your mother-in-law.”

During an Ad Club luncheon in Boise in 1948, Lind told about his three pet skunks, Cleo, Theo, and B.O., and how often people told him they had pet skunks when they were kids, which led Lind to postulate that 80 percent of Boiseans had pet skunks at one time. He told stories about people who would stop in to talk about his signs, often bringing one of those petrified watermelons to him. One of his favorites was a sign that said “No fishing within 400 yards.” It was placed miles from any drop of water. Lind said people would stop a ways down the road, turn around, and take another look. One guy allegedly walked half a mile down a dry wash looking for fishing country.

Lind got into the humorous sign business almost by accident. In 1946, with the war behind him, he tried to buy exterior plywood to advertise his service station, but only interior plywood was available. That meant both sides had to be painted to preserve the wood. Lind was quoted in the Idaho Statesman, saying, “As long as the back side of the sign was painted, I got the idea of putting humor or curiosity catching remarks on the back side”.

Some of those remarks include:

"Lava is free. Make your own soap."

"This area is for the birds. It's fowl territory."

"Nudist area. (Keep your eyes on the road.)"

"Sheep herders headed for town have right of way."

"For a fast pickup, pass a state patrolman."

At one time, there were about 150 Stinker Station signs between Green River, Wyoming and Jordan Valley, Oregon. Farris Lind came up with the humor for every one of them.

Lind contracted polio in 1963. He continued to run his company from an iron lung after that, never losing his trademark sense of humor.

He got a few complaints about his signs. Several people didn’t cotton to his sign outside of Salt Lake City that declared “Salt Lake City is full of lonely, beautiful women.” To avoid offending anyone, he had the word “lonely” removed. A similar sign about the women near Glenns Ferry prompted someone to scrawl “Where?” across it.

One of my personal favorites is still standing near Beeches Corner in Idaho Falls. It says, “Warning to tourists: Do not laugh at the natives.” About a billion years ago I was riding in a car with a fellow ten-year-old, he saw the sign and turned to me in wonder saying, “Are there NATIVES around here!?”

Fearless Farris Lind passed away in 1983. My book about Farris Lind is called Fearless. You can get a copy by clicking on the cover photo with the skunk on this page.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

He ran his first gas station in 1936 when he was only 20. That one was in Twin Falls.

After returning from service in WWII, Lind thought up a way to make his Boise service station famous. He scattered humorous signs all over southern Idaho to perk up drivers bored with many miles of sagebrush. One side advertised his growing number of Stinker Stations, while the other side offered humor, such as, in a field of lava rock (melon gravel left over from the Bonneville Flood), “Petrified watermelon. Take one home to your mother-in-law.”

During an Ad Club luncheon in Boise in 1948, Lind told about his three pet skunks, Cleo, Theo, and B.O., and how often people told him they had pet skunks when they were kids, which led Lind to postulate that 80 percent of Boiseans had pet skunks at one time. He told stories about people who would stop in to talk about his signs, often bringing one of those petrified watermelons to him. One of his favorites was a sign that said “No fishing within 400 yards.” It was placed miles from any drop of water. Lind said people would stop a ways down the road, turn around, and take another look. One guy allegedly walked half a mile down a dry wash looking for fishing country.

Lind got into the humorous sign business almost by accident. In 1946, with the war behind him, he tried to buy exterior plywood to advertise his service station, but only interior plywood was available. That meant both sides had to be painted to preserve the wood. Lind was quoted in the Idaho Statesman, saying, “As long as the back side of the sign was painted, I got the idea of putting humor or curiosity catching remarks on the back side”.

Some of those remarks include:

"Lava is free. Make your own soap."

"This area is for the birds. It's fowl territory."

"Nudist area. (Keep your eyes on the road.)"

"Sheep herders headed for town have right of way."

"For a fast pickup, pass a state patrolman."

At one time, there were about 150 Stinker Station signs between Green River, Wyoming and Jordan Valley, Oregon. Farris Lind came up with the humor for every one of them.

Lind contracted polio in 1963. He continued to run his company from an iron lung after that, never losing his trademark sense of humor.

He got a few complaints about his signs. Several people didn’t cotton to his sign outside of Salt Lake City that declared “Salt Lake City is full of lonely, beautiful women.” To avoid offending anyone, he had the word “lonely” removed. A similar sign about the women near Glenns Ferry prompted someone to scrawl “Where?” across it.

One of my personal favorites is still standing near Beeches Corner in Idaho Falls. It says, “Warning to tourists: Do not laugh at the natives.” About a billion years ago I was riding in a car with a fellow ten-year-old, he saw the sign and turned to me in wonder saying, “Are there NATIVES around here!?”

Fearless Farris Lind passed away in 1983. My book about Farris Lind is called Fearless. You can get a copy by clicking on the cover photo with the skunk on this page.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

Published on May 28, 2021 04:00

May 27, 2021

The Mascot for the Corps of Discovery

We don’t know the color of the most famous dog in Idaho history. Until 1987, we didn’t even know his name.

His name was Seaman, probably in recognition that his breed, the Newfoundland, was well known as a sailor’s dog. The journals of Lewis and Clark often mention Seaman. He belonged to Meriwether Lewis. Historians thought his name was Scannon because the journal entries seemed to say that. Historian Donald Jackson discovered the error of interpretation when scrutinizing a map from the expedition that called a creek Seaman Creek. Knowing that the explorers often named features after members of the Corps of Discovery, he put it together that the stream was named in honor of the dog.

The dog is usually described as black, but that is only an assumption. Seaman’s color is not mentioned in any of the writings of Lewis or other members of the Corps of Discovery.

The big dog was much admired by people they met along the way. Early in the journey, Lewis wrote, “[O]ne of the Shawnees a respectable looking Indian offered me three beverskins for my dog with which he appeared much pleased...I prised much for his docility and qualifications generally for my journey and of course there was no bargain.”

It was a harrowing journey for all, no less for the dog. He suffered a beaver bite that almost killed him. He had a close call with a bison and was frequently in a state of panic because of bears. Seaman suffered from grass seeds in his paws and fur, an affliction known well to dogs today romping around in the outdoors in Idaho. He also suffered terribly from mosquito bites.

But what happened to Seaman? The journals of the expedition don’t help us here. A book written in 1814 that contains some information about the Corps of Discovery mentions a dog collar in a Virginia museum with the inscription, "The greatest traveller of my species. My name is SEAMAN, the dog of captain Meriwether Lewis, whom I accompanied to the Pacific ocean through the interior of the continent of North America."

The collar seems to have been lost to time, but the inscription gives more weight to Seaman being the proper name.

We can hope that given several entries about his health and the dangers he faced that Lewis would surely have mentioned the death of the dog if it happened on the expedition. In any case, he lives on in stories and statues. Seaman is a popular figure with sculptors. The photo is of the statue of Seaman at the Sacajawea Center in Salmon, Idaho.

His name was Seaman, probably in recognition that his breed, the Newfoundland, was well known as a sailor’s dog. The journals of Lewis and Clark often mention Seaman. He belonged to Meriwether Lewis. Historians thought his name was Scannon because the journal entries seemed to say that. Historian Donald Jackson discovered the error of interpretation when scrutinizing a map from the expedition that called a creek Seaman Creek. Knowing that the explorers often named features after members of the Corps of Discovery, he put it together that the stream was named in honor of the dog.

The dog is usually described as black, but that is only an assumption. Seaman’s color is not mentioned in any of the writings of Lewis or other members of the Corps of Discovery.

The big dog was much admired by people they met along the way. Early in the journey, Lewis wrote, “[O]ne of the Shawnees a respectable looking Indian offered me three beverskins for my dog with which he appeared much pleased...I prised much for his docility and qualifications generally for my journey and of course there was no bargain.”

It was a harrowing journey for all, no less for the dog. He suffered a beaver bite that almost killed him. He had a close call with a bison and was frequently in a state of panic because of bears. Seaman suffered from grass seeds in his paws and fur, an affliction known well to dogs today romping around in the outdoors in Idaho. He also suffered terribly from mosquito bites.

But what happened to Seaman? The journals of the expedition don’t help us here. A book written in 1814 that contains some information about the Corps of Discovery mentions a dog collar in a Virginia museum with the inscription, "The greatest traveller of my species. My name is SEAMAN, the dog of captain Meriwether Lewis, whom I accompanied to the Pacific ocean through the interior of the continent of North America."

The collar seems to have been lost to time, but the inscription gives more weight to Seaman being the proper name.

We can hope that given several entries about his health and the dangers he faced that Lewis would surely have mentioned the death of the dog if it happened on the expedition. In any case, he lives on in stories and statues. Seaman is a popular figure with sculptors. The photo is of the statue of Seaman at the Sacajawea Center in Salmon, Idaho.

Published on May 27, 2021 04:00

May 26, 2021

That's Standrod, with a D

One of Idaho’s most beautiful homes is the Standrod Mansion in Pocatello. Bonus: It may be haunted.

Drew W. Standrod was a lawyer in Malad City, Idaho in 1890 when he became a member of Idaho’s constitutional convention. He was later elected Fifth Judicial District State Judge. His district covered what are now the counties of Oneida, Bannock, Bingham, Fremont, Lemhi, Custer, and Bear Lake. In 1895 he and his family moved to Pocatello to be more centrally located in his district. He served as a judge until 1899 when he went into private practice in Pocatello.

Standrod was also a financier, serving on the boards of the Standrod and Company Bank in Blackfoot, and the J.N. Ireland and Company Bank in Malad. Those banks led to the creation of banks still well-known in Idaho, Ireland Bank and D.L. Evans Bank. Standrod was also a partner in the Yellowstone Hotel in Pocatello.

D.W. Standrod became a member of Idaho’s first Public Utilities Commission and as such wrote much of the irrigation and water rights law in use today.

Lest one think that he was a success at everything, it should be noted that he ran for a seat on the Idaho Supreme Court and for governor of the state, losing in both campaigns.

Emma Standrod, his wife, was a school principal and founder of the Wyeth Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was active in historical preservation and the Red Cross.

The Standrods built their mansion in 1902 using mostly local materials. The two-story home is one of only a few in the state built in the Châteauesque style, a revival style based on the French Renaissance architecture of the monumental French country houses. The prominent corner tower gives the home a castle-like—some might say forbidding—appearance. It would not be out of place in a Charles Addams cartoon from the New Yorker. Perhaps that bolsters the ghost stories attached to the mansion.

Legend has it that daughter Cammie Standrod, distraught over the disappearance of a boyfriend her father did not approve of, died in that iconic tower. She is said to have had a kidney disease and in her weakened state caught a cold that proved her demise. Cammie is the star of most stories of haunting, though some mention the ghostly image of an elderly man, perhaps D.W. himself, who also died in his mansion.

Though the City of Pocatello owned the home for about 20 years, the Standrod Mansion is now a private residence.

Drew W. Standrod was a lawyer in Malad City, Idaho in 1890 when he became a member of Idaho’s constitutional convention. He was later elected Fifth Judicial District State Judge. His district covered what are now the counties of Oneida, Bannock, Bingham, Fremont, Lemhi, Custer, and Bear Lake. In 1895 he and his family moved to Pocatello to be more centrally located in his district. He served as a judge until 1899 when he went into private practice in Pocatello.

Standrod was also a financier, serving on the boards of the Standrod and Company Bank in Blackfoot, and the J.N. Ireland and Company Bank in Malad. Those banks led to the creation of banks still well-known in Idaho, Ireland Bank and D.L. Evans Bank. Standrod was also a partner in the Yellowstone Hotel in Pocatello.

D.W. Standrod became a member of Idaho’s first Public Utilities Commission and as such wrote much of the irrigation and water rights law in use today.

Lest one think that he was a success at everything, it should be noted that he ran for a seat on the Idaho Supreme Court and for governor of the state, losing in both campaigns.

Emma Standrod, his wife, was a school principal and founder of the Wyeth Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was active in historical preservation and the Red Cross.

The Standrods built their mansion in 1902 using mostly local materials. The two-story home is one of only a few in the state built in the Châteauesque style, a revival style based on the French Renaissance architecture of the monumental French country houses. The prominent corner tower gives the home a castle-like—some might say forbidding—appearance. It would not be out of place in a Charles Addams cartoon from the New Yorker. Perhaps that bolsters the ghost stories attached to the mansion.

Legend has it that daughter Cammie Standrod, distraught over the disappearance of a boyfriend her father did not approve of, died in that iconic tower. She is said to have had a kidney disease and in her weakened state caught a cold that proved her demise. Cammie is the star of most stories of haunting, though some mention the ghostly image of an elderly man, perhaps D.W. himself, who also died in his mansion.

Though the City of Pocatello owned the home for about 20 years, the Standrod Mansion is now a private residence.

Published on May 26, 2021 04:00

May 25, 2021

Another Drowned Town

Power County, in southern Idaho, is named for the electricity generating facilities at the American Falls Dam. The dam is vitally important to the county. In fact, it is so important that they moved the entire town of American Falls to higher ground to accommodate the American Falls Reservoir.

Moving a town is a big job. It took about 18 months, starting in 1925, and wasn't complete until 1927.

Individual houses were moved by truck. They put larger buildings on rollers and pulled them along a few inches at a time. The Methodist church came down brick by brick and was reconstructed with the rest of the town on the hill above the river. The Lutheran church was moved in one piece. In the middle of the move parishioners simply propped a ladder up against the building, climbed in, and held services in the middle of the street.

When the reservoir began to fill, the only thing left of the old town of American Falls was a cement grain elevator, abandoned foundations, and a grid of roads and sidewalks. You can still see the lonely old grain elevator sticking up like a tombstone for the town when the reservoir is low.

One other thing lost as a result of the dam project--the waterfall that gave the town its name. The 25-foot American Falls of the Snake River is now a part of history.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

Moving a town is a big job. It took about 18 months, starting in 1925, and wasn't complete until 1927.

Individual houses were moved by truck. They put larger buildings on rollers and pulled them along a few inches at a time. The Methodist church came down brick by brick and was reconstructed with the rest of the town on the hill above the river. The Lutheran church was moved in one piece. In the middle of the move parishioners simply propped a ladder up against the building, climbed in, and held services in the middle of the street.

When the reservoir began to fill, the only thing left of the old town of American Falls was a cement grain elevator, abandoned foundations, and a grid of roads and sidewalks. You can still see the lonely old grain elevator sticking up like a tombstone for the town when the reservoir is low.

One other thing lost as a result of the dam project--the waterfall that gave the town its name. The 25-foot American Falls of the Snake River is now a part of history.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

Published on May 25, 2021 04:00

May 24, 2021

The Idaho Buildings

If you think of the Idaho Building at 8th and Bannock in Boise as THE Idaho Building, you’re missing a bit of history. The downtown Boise Building’s story goes back to 1910, when it replaced a livery barn. The building, designed by Tortellotte & Co., made the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Today, we’re looking at three other Idaho Buildings that gained a measure of fame, none of them located in Idaho.

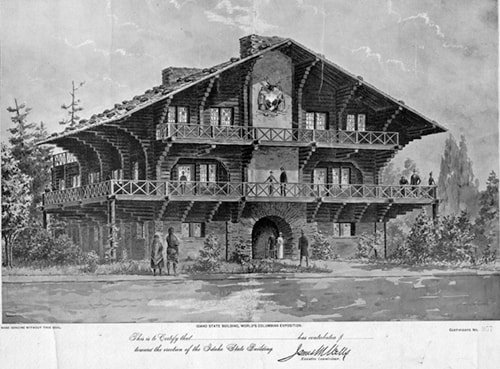

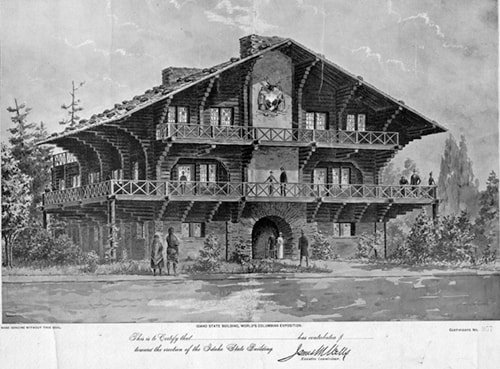

Giddy with statehood, Idaho was eager to participate in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was a celebration of the quadricentennial of Columbus’ “discovery” of the new world, albeit celebrated a year late.

The exhibition structure was designed by Spokane architect K.K. Cutter, but the Idaho Building was otherwise all Idaho. It used 22 types of lumber, all from Shoshone County. The stonework came from Nez Perce County and the foundation veneer was lava rock from Southern Idaho, which had an abundance.

The interior was uniquely Idaho. A frying pan clock with golden hands was set to Idaho time. The men’s reception room had a hunting knife for a latch. Some chairs were made from antlers and mountain lion skins. Guests drank from silver cups made in Idaho, until most of them disappeared. There was needlework from the ladies of Albion, watercolors of Idaho wildflowers from Post Falls, fossil rocks from Boise, and a mastodon tusk from Blackfoot.

Boise’s Columbian Club, which is active to this day, was named for its original mission, which was to furnish the Idaho Building.

The Columbian Exposition was billed as the “White City.” This huge log cabin drew attention to itself simply for not being white.

At the end of the exposition the building was taken down log by log and moved to… No, not some lake in Idaho. It was sold at auction and moved to Wisconsin where it was to be used on Lake Geneva as a retreat for orphaned boys. The wealthy owner who had it rebuilt on the lakeshore lost interest in the project, so the orphans never saw the building. It was used for a time as a residence for laborers building a road, then for ice storage. Somehow it got the reputation as being haunted by “Idaho cowboys.” That did not raise its resale value. In 1911, the building was torn down. Some of the logs were used for a municipal pier. The rest of the building seemed to vanish along with those ghosts.

But we have no time to mourn the demise of that Idaho Building. There were other expositions ahead that beckoned to chambers of commerce in Idaho.

The next Idaho building went up in 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Unlike the 1893 building, this one was modest in size. At 60 feet square, it was the smallest state exhibit at the celebration. Even so, it took second prize among those exhibits.

The hacienda style architecture of the ranch house was so popular the architect had more than 300 requests for the plans. With a roof of red clay tiles and an adobe exterior, it might as well have represented the Southwest. At the end of the exposition a Texan purchased the building for $6,940. It was moved piece-by-piece to San Antonio by rail. Rather than simply put it back together the buyer decided to make two houses out of it. The pair of homes are still standing side by side today on Beacon Hill.

The third Idaho Building to appear in an exposition was closer to home. Idaho was represented at Portland’s 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition by a 100-foot by 60-foot building that resembled a Swiss chalet. Boise architects Wayland and Fennell designed it. Portland’s Idaho Building was noted for its striking colors, depicted in the hand-painted photo accompanying this article.

Idaho was generous with its $8,900 building, allowing Montana, Wyoming, and Nevada to use it for their state’s days at the fair. Several Idaho cities got use of the building on certain days, showing exhibits from Boise, Weiser, Pocatello, Wallace, Moscow, and Lewiston. The Idaho Statesman called the building “a cold-blooded business getter.” That was supposed to be a compliment.

The building generated a movement in Boise to have it brought to the city as a permanent exhibit. There was much excitement about this until it was pointed out that the Idaho Building was not meant to be a permanent structure. It wouldn’t stand being disassembled, transported, and reassembled, so the idea was abandoned. The structure, like many others at the exposition, was ultimately torn down.

So, this trio of Idaho buildings never made it to the state. We’ll have to be satisfied with the six-story Idaho Building in downtown Boise that was built to last, and hope it survives long into the future. It has already twice dodged a wrecking ball in the name of urban renewal.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Today, we’re looking at three other Idaho Buildings that gained a measure of fame, none of them located in Idaho.

Giddy with statehood, Idaho was eager to participate in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was a celebration of the quadricentennial of Columbus’ “discovery” of the new world, albeit celebrated a year late.

The exhibition structure was designed by Spokane architect K.K. Cutter, but the Idaho Building was otherwise all Idaho. It used 22 types of lumber, all from Shoshone County. The stonework came from Nez Perce County and the foundation veneer was lava rock from Southern Idaho, which had an abundance.

The interior was uniquely Idaho. A frying pan clock with golden hands was set to Idaho time. The men’s reception room had a hunting knife for a latch. Some chairs were made from antlers and mountain lion skins. Guests drank from silver cups made in Idaho, until most of them disappeared. There was needlework from the ladies of Albion, watercolors of Idaho wildflowers from Post Falls, fossil rocks from Boise, and a mastodon tusk from Blackfoot.

Boise’s Columbian Club, which is active to this day, was named for its original mission, which was to furnish the Idaho Building.

The Columbian Exposition was billed as the “White City.” This huge log cabin drew attention to itself simply for not being white.

At the end of the exposition the building was taken down log by log and moved to… No, not some lake in Idaho. It was sold at auction and moved to Wisconsin where it was to be used on Lake Geneva as a retreat for orphaned boys. The wealthy owner who had it rebuilt on the lakeshore lost interest in the project, so the orphans never saw the building. It was used for a time as a residence for laborers building a road, then for ice storage. Somehow it got the reputation as being haunted by “Idaho cowboys.” That did not raise its resale value. In 1911, the building was torn down. Some of the logs were used for a municipal pier. The rest of the building seemed to vanish along with those ghosts.

But we have no time to mourn the demise of that Idaho Building. There were other expositions ahead that beckoned to chambers of commerce in Idaho.

The next Idaho building went up in 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Unlike the 1893 building, this one was modest in size. At 60 feet square, it was the smallest state exhibit at the celebration. Even so, it took second prize among those exhibits.

The hacienda style architecture of the ranch house was so popular the architect had more than 300 requests for the plans. With a roof of red clay tiles and an adobe exterior, it might as well have represented the Southwest. At the end of the exposition a Texan purchased the building for $6,940. It was moved piece-by-piece to San Antonio by rail. Rather than simply put it back together the buyer decided to make two houses out of it. The pair of homes are still standing side by side today on Beacon Hill.

The third Idaho Building to appear in an exposition was closer to home. Idaho was represented at Portland’s 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition by a 100-foot by 60-foot building that resembled a Swiss chalet. Boise architects Wayland and Fennell designed it. Portland’s Idaho Building was noted for its striking colors, depicted in the hand-painted photo accompanying this article.

Idaho was generous with its $8,900 building, allowing Montana, Wyoming, and Nevada to use it for their state’s days at the fair. Several Idaho cities got use of the building on certain days, showing exhibits from Boise, Weiser, Pocatello, Wallace, Moscow, and Lewiston. The Idaho Statesman called the building “a cold-blooded business getter.” That was supposed to be a compliment.

The building generated a movement in Boise to have it brought to the city as a permanent exhibit. There was much excitement about this until it was pointed out that the Idaho Building was not meant to be a permanent structure. It wouldn’t stand being disassembled, transported, and reassembled, so the idea was abandoned. The structure, like many others at the exposition, was ultimately torn down.

So, this trio of Idaho buildings never made it to the state. We’ll have to be satisfied with the six-story Idaho Building in downtown Boise that was built to last, and hope it survives long into the future. It has already twice dodged a wrecking ball in the name of urban renewal.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on May 24, 2021 04:53

May 23, 2021

Kit Carson, Horse Thief?

Most of the stories I relate through Speaking of Idaho are well-known and can be corroborated by more than one source. Sometimes I run across a story that is of some interest, but is little more than hearsay. Today, presented as hearsay, is a story about Kit Carson.

Christopher Houston “Kit” Carson was well known in his own time through dime novels that told often exaggerated stories of the West. He was an army officer, a mountain man, and famously a guide for John C. Frémont. Nowhere in his resume does it list “horse thief.”

However, such a tale was told about the man in the May 20, 1923 edition of the Idaho Statesman. The article was part of a continuing series of stories told by the son of Captain Stanton G. Fisher. The elder Fisher had over the years been an Indian trader, chief of scouts, and the Indian Agent at Fort Hall. The time period when he held various posts and titles seems to have been from the late 1860s into the 1890s. He was involved in what some call the Nez Perce War.

Fisher’s son heard from his father that Kit Carson and Jim Beckworth, a freed slave who was a mulatto and himself a well-known mountain man, stole a string of 6 or 8 horses and mules from someone near Fort Hall. The teller of the tale was careful to say that stealing horses at that (unspecified) time was not necessarily looked upon with great disfavor if one didn’t steal them from a friend or neighbor.

The tale-teller said the owner of the small herd offered a beaver trap worth $16 for every animal returned to him. Jim Bridger, ANOTHER well-known mountain man who was also at the fort at that time, told a little Frenchman named Meachau LeClair about the reward offer. LeClair and a young Mexican named Thomas Lavatte set out to earn those beaver traps.

They caught up with Carson and Beckworth somewhere outside of Soda Springs. The pair waited until well into the night to approach the camp of the two men. They first silenced a bell tied around the neck of one horse, then quietly led the herd away without waking anyone. Not relishing the idea of being overtaken on their way back to Fort Hall by Carson and Beckworth, the men decided to steal the personal horses of the mountain men as well as the previously purloined herd. With some tense moments delivered courtesy of a growling guard dog, they were able to sneak the mounts away.

With Carson and Beckworth now on foot, LeClair and Lavatte pounded back to Fort Hall with the herd, which they would trade for the promised beaver traps. Along the way they stopped at Soda Springs where a store proprietor noticed the men had the Carson and Beckworth horses, to which the Frenchman allegedly said, in the third-hand telling of the tale, “Yas, you tell de man Kit Carson and de man Jim Beckworth dat de little Frenchman got his mool. You bet he no folly me.”

A grain of truth or a grain of salt? You be the judge.

Christopher Houston “Kit” Carson was well known in his own time through dime novels that told often exaggerated stories of the West. He was an army officer, a mountain man, and famously a guide for John C. Frémont. Nowhere in his resume does it list “horse thief.”

However, such a tale was told about the man in the May 20, 1923 edition of the Idaho Statesman. The article was part of a continuing series of stories told by the son of Captain Stanton G. Fisher. The elder Fisher had over the years been an Indian trader, chief of scouts, and the Indian Agent at Fort Hall. The time period when he held various posts and titles seems to have been from the late 1860s into the 1890s. He was involved in what some call the Nez Perce War.

Fisher’s son heard from his father that Kit Carson and Jim Beckworth, a freed slave who was a mulatto and himself a well-known mountain man, stole a string of 6 or 8 horses and mules from someone near Fort Hall. The teller of the tale was careful to say that stealing horses at that (unspecified) time was not necessarily looked upon with great disfavor if one didn’t steal them from a friend or neighbor.

The tale-teller said the owner of the small herd offered a beaver trap worth $16 for every animal returned to him. Jim Bridger, ANOTHER well-known mountain man who was also at the fort at that time, told a little Frenchman named Meachau LeClair about the reward offer. LeClair and a young Mexican named Thomas Lavatte set out to earn those beaver traps.

They caught up with Carson and Beckworth somewhere outside of Soda Springs. The pair waited until well into the night to approach the camp of the two men. They first silenced a bell tied around the neck of one horse, then quietly led the herd away without waking anyone. Not relishing the idea of being overtaken on their way back to Fort Hall by Carson and Beckworth, the men decided to steal the personal horses of the mountain men as well as the previously purloined herd. With some tense moments delivered courtesy of a growling guard dog, they were able to sneak the mounts away.

With Carson and Beckworth now on foot, LeClair and Lavatte pounded back to Fort Hall with the herd, which they would trade for the promised beaver traps. Along the way they stopped at Soda Springs where a store proprietor noticed the men had the Carson and Beckworth horses, to which the Frenchman allegedly said, in the third-hand telling of the tale, “Yas, you tell de man Kit Carson and de man Jim Beckworth dat de little Frenchman got his mool. You bet he no folly me.”

A grain of truth or a grain of salt? You be the judge.

Published on May 23, 2021 04:00

May 22, 2021

Paul Bunyan in Idaho

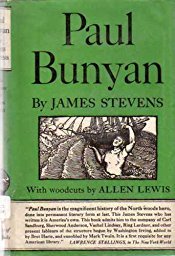

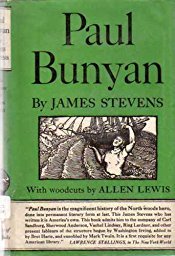

So, did you know that Paul Bunyan has an Idaho connection? Stories about Paul Bunyan and his giant blue ox, Babe, circulated around lumber camps across the country for decades before anyone thought to write them down and publish them. Eventually, many people did. One of the best remembered tellers of those tales was author James Stevens who spent much of his childhood in Idaho. Sinclair Lewis called Stevens “the true son of Paul Bunyan.”

Stevens was a soldier in France during World War I. He did more than fight, though. He published his Paul Bunyan stories in Stars and Stripes.

After the war he knocked around the country as an itinerant laborer, educating himself in local libraries wherever he went. He published poetry in Saturday Evening Post, and more Paul Bunyan stories in American Mercury.

Stevens’ 1945 novel Big Jim Turner, about an itinerant working man and poet who grew up around Knox, Idaho (now a ghost town), has many autobiographical elements in it.

His best-known work, though, is probably his Paul Bunyan book (pictured), published in 1925. Stevens died in Seattle in 1971.

This Paul Bunyan in St. Maries has a history of its own. He's one of several "Muffler Men" that can be seen around Idaho.

This Paul Bunyan in St. Maries has a history of its own. He's one of several "Muffler Men" that can be seen around Idaho.

Stevens was a soldier in France during World War I. He did more than fight, though. He published his Paul Bunyan stories in Stars and Stripes.

After the war he knocked around the country as an itinerant laborer, educating himself in local libraries wherever he went. He published poetry in Saturday Evening Post, and more Paul Bunyan stories in American Mercury.

Stevens’ 1945 novel Big Jim Turner, about an itinerant working man and poet who grew up around Knox, Idaho (now a ghost town), has many autobiographical elements in it.

His best-known work, though, is probably his Paul Bunyan book (pictured), published in 1925. Stevens died in Seattle in 1971.

This Paul Bunyan in St. Maries has a history of its own. He's one of several "Muffler Men" that can be seen around Idaho.

This Paul Bunyan in St. Maries has a history of its own. He's one of several "Muffler Men" that can be seen around Idaho.

Published on May 22, 2021 04:00

May 21, 2021

Heavy Construction

The Channel Tunnel between Great Britain and France is an engineering marvel that might have remained on the drawing board if it weren’t for the main who maintained his office in a converted home in Boise’s North End.

Jack Lemley graduated in 1960 from the University of Idaho with a degree in architecture. He worked for a few years as an engineer for a San Francisco company before moving his family to Boise in 1977 to take a job with Morrison Knudsen. He came on at MK as the executive vice president in charge of heavy construction. He managed major projects there until 1988 when he was passed over for the position of the CEO in favor of Bill Agee. One can’t help but wonder if MK would still be around if the decision had gone the other way.

Lemley’s resignation from MK came just in time for him to land the contract to supervise the construction of the Chunnel. It was about as big a job as they get. More than 15,000 people worked on the project. It resulted in two train tunnels and a service tunnel, more than 31 miles long and as deep 380 feet below sea level.

For his work on the project, Lemley was awarded the Order of Merit and Queen Elizabeth named him a Commander of the British Empire.

After the Chunnel was complete, Lemley became the CEO of U.S. Ecology in Houston. He moved the firm’s headquarters to Boise.

Even Boiseans who are well travelled probably see another project of Lemley’s much more often than they see the Chunnel. His firm designed and constructed the Idaho Water Center at the corner of Front and Broadway. It’s the home of the University of Idaho graduate engineering programs in Boise.

Lemley had his hand in dozens of major projects from Seattle’s Interstate-90 and Interstate-5 interchange to the Trans-Panama Pipeline.

A popular figure in Great Britain because of his success with the Chunnel project, Lemley was chosen to build the venues and infrastructure for the 2012 Olympics in London. Frustrated with political wrangling, he resigned the position in 2006.

Jack Lemley was inducted into the Idaho Hall of Fame in 1997 and into the Idaho Technology Council’s Hall of Fame in 2011.

Lemley’s son, Jim, is a manager of a different kind of big projects. He is a film producer best known for the Diving Bell and the Butterfly and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Slayer.

Jack Lemley graduated in 1960 from the University of Idaho with a degree in architecture. He worked for a few years as an engineer for a San Francisco company before moving his family to Boise in 1977 to take a job with Morrison Knudsen. He came on at MK as the executive vice president in charge of heavy construction. He managed major projects there until 1988 when he was passed over for the position of the CEO in favor of Bill Agee. One can’t help but wonder if MK would still be around if the decision had gone the other way.

Lemley’s resignation from MK came just in time for him to land the contract to supervise the construction of the Chunnel. It was about as big a job as they get. More than 15,000 people worked on the project. It resulted in two train tunnels and a service tunnel, more than 31 miles long and as deep 380 feet below sea level.

For his work on the project, Lemley was awarded the Order of Merit and Queen Elizabeth named him a Commander of the British Empire.

After the Chunnel was complete, Lemley became the CEO of U.S. Ecology in Houston. He moved the firm’s headquarters to Boise.

Even Boiseans who are well travelled probably see another project of Lemley’s much more often than they see the Chunnel. His firm designed and constructed the Idaho Water Center at the corner of Front and Broadway. It’s the home of the University of Idaho graduate engineering programs in Boise.

Lemley had his hand in dozens of major projects from Seattle’s Interstate-90 and Interstate-5 interchange to the Trans-Panama Pipeline.

A popular figure in Great Britain because of his success with the Chunnel project, Lemley was chosen to build the venues and infrastructure for the 2012 Olympics in London. Frustrated with political wrangling, he resigned the position in 2006.

Jack Lemley was inducted into the Idaho Hall of Fame in 1997 and into the Idaho Technology Council’s Hall of Fame in 2011.

Lemley’s son, Jim, is a manager of a different kind of big projects. He is a film producer best known for the Diving Bell and the Butterfly and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Slayer.

Published on May 21, 2021 04:00

May 20, 2021

Idaho's Missing Counties

Idaho has 44 counties, ranging in size from 8,485-square-mile Idaho County, to Payette County, which is 408 square miles. But it hasn’t always been that way. County boundaries and the names of counties changed quite a lot over the years.

The original Idaho Territory included what we now call Montana and most of present-day Wyoming in 1863. By 1864 the Territory began to resemble the shape of the state we know today, and had 14 counties.

Those enormous counties got smaller as population grew and the need for government closer to home grew with it. Once a county was named, that name tended to stick, even through shrinkage. We lost only two names in the shuffle, Alturas and Logan.

Alturas was a county from February 4, 1864 to March 5, 1895. It was a huge county, bigger than the states of New Jersey, Maryland, and Delaware combined. Elmore County and Logan County were carved out of Alturas in 1889 by the Idaho Legislature. But what the legislature giveth, it can also take away. In 1895 Logan and Alturas were combined to become Blaine County. Then just a couple of weeks later, the legislature sliced off a sizable piece of that to create Lincoln County.

Map courtesy of the Idaho Genealogical Society.

Map courtesy of the Idaho Genealogical Society.

The original Idaho Territory included what we now call Montana and most of present-day Wyoming in 1863. By 1864 the Territory began to resemble the shape of the state we know today, and had 14 counties.

Those enormous counties got smaller as population grew and the need for government closer to home grew with it. Once a county was named, that name tended to stick, even through shrinkage. We lost only two names in the shuffle, Alturas and Logan.

Alturas was a county from February 4, 1864 to March 5, 1895. It was a huge county, bigger than the states of New Jersey, Maryland, and Delaware combined. Elmore County and Logan County were carved out of Alturas in 1889 by the Idaho Legislature. But what the legislature giveth, it can also take away. In 1895 Logan and Alturas were combined to become Blaine County. Then just a couple of weeks later, the legislature sliced off a sizable piece of that to create Lincoln County.

Map courtesy of the Idaho Genealogical Society.

Map courtesy of the Idaho Genealogical Society.

Published on May 20, 2021 04:00