Rick Just's Blog, page 126

May 19, 2021

Lindy in Boise

There was no bigger celebrity in 1927 than Charles Lindbergh. On May 27 of that year the 25-year-old US Mail pilot had landed his single-engine plane, the Spirit of St. Louis in Paris to complete the first solo flight across the Atlantic. Then he took a real trip. The Daniel Guggenheim Fund sponsored a three-month flying tour that would take him to 48 states, where he would visit 92 cities and give 147 speeches.

Lindbergh landed in Boise on September 4 and was greeted by a crowd of 40,000 people. This picture, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, shows, left to right, Leo J. Falk, Gov. H.C. Baldridge, and Boise Mayor Walter F. Hanson with Lindbergh. The Spirit of St. Lewis is in the background.

The Idaho Statesman described Lindy’s departure thusly: “Lindy made a graceful take-off, just as he had landed the day before. He circled over the city, then headed northeast over the hills, rising higher and higher into the clouds until the Spirit of St. Louis appeared a little speck in the sky. Lindy was gone.”

It was his only stop in Idaho on the tour, but folks in the northern part of the state had a chance to see him and his famous plane land in Spokane on September 12.

Lindbergh landed in Boise on September 4 and was greeted by a crowd of 40,000 people. This picture, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, shows, left to right, Leo J. Falk, Gov. H.C. Baldridge, and Boise Mayor Walter F. Hanson with Lindbergh. The Spirit of St. Lewis is in the background.

The Idaho Statesman described Lindy’s departure thusly: “Lindy made a graceful take-off, just as he had landed the day before. He circled over the city, then headed northeast over the hills, rising higher and higher into the clouds until the Spirit of St. Louis appeared a little speck in the sky. Lindy was gone.”

It was his only stop in Idaho on the tour, but folks in the northern part of the state had a chance to see him and his famous plane land in Spokane on September 12.

Published on May 19, 2021 04:00

May 18, 2021

Heise's Medal

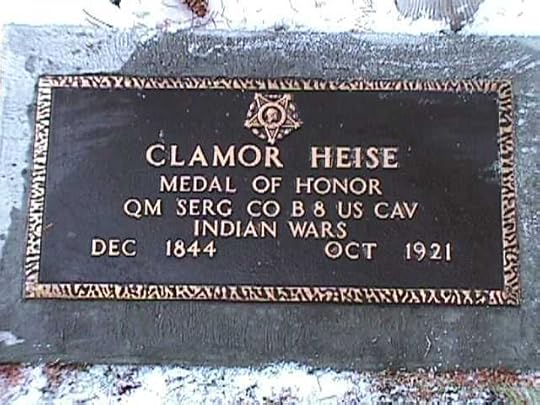

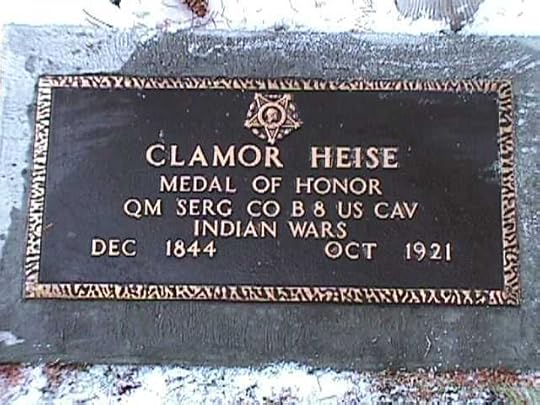

As I wrote in a previous post, Richard Clamor Heise was the founder of Heise Hot Springs in eastern Idaho. He is buried on the grounds of the resort.

One thing about Heise that may come as a surprise to many is that he was a Medal of Honor winner. The details of the action for which he was awarded the medal are sketchy. He was recognized for his service between August 13 and October 31, 1868 during the Indian Wars in the vicinity of the Black Mountains of Arizona. He was cited for “Bravery in scouts and actions against Indians.”

Heise’s actions may have well been heroic, but one must remember that the Medal of Honor requirements were less strict inn the early days of its existence. Heise was one of 40 soldiers of Company B, 8th US Cavalry who were so honored for their actions during that time and at that place.

One thing about Heise that may come as a surprise to many is that he was a Medal of Honor winner. The details of the action for which he was awarded the medal are sketchy. He was recognized for his service between August 13 and October 31, 1868 during the Indian Wars in the vicinity of the Black Mountains of Arizona. He was cited for “Bravery in scouts and actions against Indians.”

Heise’s actions may have well been heroic, but one must remember that the Medal of Honor requirements were less strict inn the early days of its existence. Heise was one of 40 soldiers of Company B, 8th US Cavalry who were so honored for their actions during that time and at that place.

Published on May 18, 2021 04:00

May 17, 2021

An Idaho Car

In the early days of automobiles many entrepreneurial mechanics tried building their own. A few even started their own brands, some of which live on today. Many towns in the Northwest had their own automobiles being built in small assembly plants in the teens and twenties. Lost brands such as the Totem, the Spokane, the Tilikum, and the Seattle were the result. By the 1930s most of those upstarts had disappeared. Then, in 1975 Don Stinebaugh of Post Falls, Idaho decided to build a car.

Stinebaugh was an inventor with at least 48 patents to his name. He’d invented a snowmobile engine that made him a fair amount of money, for one. His cars grew out of his tinkering with off highway vehicles. He built several all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) that people liked, including tandem axel models that pre-dated today’s side-by-side utility task vehicles (UTVs) . Had he continued down that (non) road, he might have done well with his vehicles. He got distracted, though, when people started to encourage him to convert his ATVs for street use.

Cutting to the chase, the 1975 Leata was born from those early off-road vehicles. It had a hand-laid fiberglass body, an 83-HP Pinto engine, and a diamond tuft interior that would not be out-of-place in a hot rod. The first Leatas looked a bit like a British Morris (left in the photo) with a continental kit on the back. Stinebaugh built about 20 of them. One was returned because it went too fast for the owner.

There was no 1976 Leata, but Sinebaugh wasn’t through. He brought out the Leata Cabalero in 1977 (right in the photo). It came in several models, including a convertible and a pickup. The Cabalero was basically a Chevette with a custom body. Where the original Leata could claim snappy performance, the 1977 models were sluggish. The automotive press panned them. Stinebaugh made and sold about 70 of them, then closed up shop.

Leata’s were not aesthetically pleasing. They filled no real automotive need a Pinto couldn’t fill for less money. Still, my hat is off to Mr. Stinebaugh for following his dream and creating an Idaho original.

[image error]

Stinebaugh was an inventor with at least 48 patents to his name. He’d invented a snowmobile engine that made him a fair amount of money, for one. His cars grew out of his tinkering with off highway vehicles. He built several all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) that people liked, including tandem axel models that pre-dated today’s side-by-side utility task vehicles (UTVs) . Had he continued down that (non) road, he might have done well with his vehicles. He got distracted, though, when people started to encourage him to convert his ATVs for street use.

Cutting to the chase, the 1975 Leata was born from those early off-road vehicles. It had a hand-laid fiberglass body, an 83-HP Pinto engine, and a diamond tuft interior that would not be out-of-place in a hot rod. The first Leatas looked a bit like a British Morris (left in the photo) with a continental kit on the back. Stinebaugh built about 20 of them. One was returned because it went too fast for the owner.

There was no 1976 Leata, but Sinebaugh wasn’t through. He brought out the Leata Cabalero in 1977 (right in the photo). It came in several models, including a convertible and a pickup. The Cabalero was basically a Chevette with a custom body. Where the original Leata could claim snappy performance, the 1977 models were sluggish. The automotive press panned them. Stinebaugh made and sold about 70 of them, then closed up shop.

Leata’s were not aesthetically pleasing. They filled no real automotive need a Pinto couldn’t fill for less money. Still, my hat is off to Mr. Stinebaugh for following his dream and creating an Idaho original.

[image error]

Published on May 17, 2021 04:00

May 16, 2021

Two-Gun Bob's Dog

Robert Limbert was a renaissance man of the West. He was a taxidermist, a hunting guide, an exhibit designer, an explorer, a writer, a photographer, and a tireless promoter of Idaho. Limbert was known as “Two-Gun Bob” when he was demonstrating his shooting skills for an audience. He built Redfish Lake Lodge, and on and on… More stories to follow, but today’s story is a little footnote (you’ll forgive me for that one, maybe?) in his most famous accomplishment.

Limbert was the man who explored what we now know as Craters of the Moon, and wrote the 25-page article that appeared in National Geographic in 1924 that intrigued the nation enough for Calvin Coolidge to proclaim it a national monument later that year. The article is available online and includes many of Lambert’s pictures that are still stunning today.

The National Geographic article documented a trip he and a friend took across the forbidding black desert. Here’s the cavalier way he described it:

“One morning in May W. L. Cole and I, both of Boise, Idaho, left Minidoka, packing on our backs bedding. an aluminum cook outfit, a 5 x 7 camera and tripod, binoculars, and supplies sufficient for two weeks, making a total pack each of 55 pounds.”

And now, to the footnote:

“We also took with us an Airedale terrier for a camp dog. This was a mistake, for after three days' travel his feet were worn raw and bleeding. In some places it was necessary to carry him or sit and wait while he picked his way across.”

The dog of the adventure was not named Scout, or Hercules, or Intrepid. He was named Teddy. He was mentioned once more in the article: “The dog was in terrible shape also: it was pitiful to watch him as he hobbled after us.”

Left at what Limbert wrote for National Geographic you might think he just watched his companion animal suffer. He did much more than that for the Airedale. He cut up clothing to make booties for the dog, then did it again when they wore out.

The three of them—two men and a dog—covered 80 miles in 17 days.

The picture below, which appeared in National Geographic, is “a lava spout in Vermilion Canyon.” Teddy is resting to the right while Limbert and Cole pose for the picture. Limbert was the photographer. He was in most of the pictures he took of the expedition, which were apparently shot using a timer or remote shutter release. Limbert was a tireless promoter of Idaho, and of Robert Limbert, for which we should be glad. The photo comes from the Robert Limbert papers, Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

Limbert was the man who explored what we now know as Craters of the Moon, and wrote the 25-page article that appeared in National Geographic in 1924 that intrigued the nation enough for Calvin Coolidge to proclaim it a national monument later that year. The article is available online and includes many of Lambert’s pictures that are still stunning today.

The National Geographic article documented a trip he and a friend took across the forbidding black desert. Here’s the cavalier way he described it:

“One morning in May W. L. Cole and I, both of Boise, Idaho, left Minidoka, packing on our backs bedding. an aluminum cook outfit, a 5 x 7 camera and tripod, binoculars, and supplies sufficient for two weeks, making a total pack each of 55 pounds.”

And now, to the footnote:

“We also took with us an Airedale terrier for a camp dog. This was a mistake, for after three days' travel his feet were worn raw and bleeding. In some places it was necessary to carry him or sit and wait while he picked his way across.”

The dog of the adventure was not named Scout, or Hercules, or Intrepid. He was named Teddy. He was mentioned once more in the article: “The dog was in terrible shape also: it was pitiful to watch him as he hobbled after us.”

Left at what Limbert wrote for National Geographic you might think he just watched his companion animal suffer. He did much more than that for the Airedale. He cut up clothing to make booties for the dog, then did it again when they wore out.

The three of them—two men and a dog—covered 80 miles in 17 days.

The picture below, which appeared in National Geographic, is “a lava spout in Vermilion Canyon.” Teddy is resting to the right while Limbert and Cole pose for the picture. Limbert was the photographer. He was in most of the pictures he took of the expedition, which were apparently shot using a timer or remote shutter release. Limbert was a tireless promoter of Idaho, and of Robert Limbert, for which we should be glad. The photo comes from the Robert Limbert papers, Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

Published on May 16, 2021 04:00

May 15, 2021

Longing for the Interurban

File this one under “You don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.”

Boise had a street car system in 1890. They were built in many cities in the latter part of the 19th century as an efficient way to get people around town. Boise’s system soon became Treasure Valley’s system, with lines going in a 60-mile loop to Eagle, Star, Middleton, Caldwell, Nampa, Meridian and back to Boise.

It was popular for people to pack a picnic lunch and take the loop on a Sunday just for the fun of it. Spurs were extended from Caldwell to Wilder and Lake Lowell, as well.

Several companies ran portions of the system, which become generally known as the Interurban, over the years. The light rail trains were powered by electricity, so it shouldn’t come as a big surprise that Idaho Power Company ran the trains for a time.

Wouldn’t something like that be a wonderful resource today? So why weren’t “we” smart enough to save the Interurban?

First, you need to know that it wasn’t a public system. Several companies were involved over the years, each trying to make a profit, and none really succeeding. Yes, there’s a conspiracy theory that General Motors bought up all the light rail lines in the country and closed them down so that people would have to buy cars. And, yes, GM was convicted for plotting to monopolize transportation systems post World War One. But it wasn’t GM that killed the systems. Not exactly. They were trying to make a profit from their National City Lines (which did NOT run a system in the Treasure Valley).

Cars did help kill the trollies when people began buying them. But it was buses that proved their demise. It was simply much cheaper to add a bus route and a few bus stop signs as cities grew. Quicker, too. Interurban tracks were taken out in some places as buses and cars became the dominant forms of transportation. Often they didn’t even bother pulling up the tracks, instead they just paved over them like the useless relics they had become.

Ah, but, wouldn’t it be nice to hop on a smooth running trolley and watch the cities and sagebrush go by while you enjoyed an ice cream cone on a Sunday afternoon?

The photo is a packed Boise and Interurban car from 1910, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

For more on the Interurban, read Treasure Valley's Electric Railway by Barbara Perry Bauer and Elizabeth Jacox.

Boise had a street car system in 1890. They were built in many cities in the latter part of the 19th century as an efficient way to get people around town. Boise’s system soon became Treasure Valley’s system, with lines going in a 60-mile loop to Eagle, Star, Middleton, Caldwell, Nampa, Meridian and back to Boise.

It was popular for people to pack a picnic lunch and take the loop on a Sunday just for the fun of it. Spurs were extended from Caldwell to Wilder and Lake Lowell, as well.

Several companies ran portions of the system, which become generally known as the Interurban, over the years. The light rail trains were powered by electricity, so it shouldn’t come as a big surprise that Idaho Power Company ran the trains for a time.

Wouldn’t something like that be a wonderful resource today? So why weren’t “we” smart enough to save the Interurban?

First, you need to know that it wasn’t a public system. Several companies were involved over the years, each trying to make a profit, and none really succeeding. Yes, there’s a conspiracy theory that General Motors bought up all the light rail lines in the country and closed them down so that people would have to buy cars. And, yes, GM was convicted for plotting to monopolize transportation systems post World War One. But it wasn’t GM that killed the systems. Not exactly. They were trying to make a profit from their National City Lines (which did NOT run a system in the Treasure Valley).

Cars did help kill the trollies when people began buying them. But it was buses that proved their demise. It was simply much cheaper to add a bus route and a few bus stop signs as cities grew. Quicker, too. Interurban tracks were taken out in some places as buses and cars became the dominant forms of transportation. Often they didn’t even bother pulling up the tracks, instead they just paved over them like the useless relics they had become.

Ah, but, wouldn’t it be nice to hop on a smooth running trolley and watch the cities and sagebrush go by while you enjoyed an ice cream cone on a Sunday afternoon?

The photo is a packed Boise and Interurban car from 1910, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

For more on the Interurban, read Treasure Valley's Electric Railway by Barbara Perry Bauer and Elizabeth Jacox.

Published on May 15, 2021 04:00

May 14, 2021

A Legendary Highwayman, Part 5 of 5

Link to yesterday's post.

And now, after four days of build-up about Ed Trafton, we come to the heist that made him famous. We’ve followed him in and out of prison, trailed behind his rustled horses, and seen him betray his own mother over and over. Now we learn of the “Lone Highwayman of Yellowstone Park.”

Ed Trafton was nearing 60 in 1915, an age when most men would rather settle down and put rustling behind them. He had purchased a farm in Rupert with some of the money he had stolen from his mother. But he wanted at least one more heist before he gave up his guns.

Yellowstone National Park was country he knew well. One thing he knew about it was that in 1915 wealthy tourists who stayed at various establishments in the park toured in relative luxury, riding in spiffed up stages pulled by teams of horses. The practice was for these stages to leave every few minutes on the tour. Spacing them out assured that the well-dressed travelers did not have to endure dust from the stage ahead.

On Wednesday, July 29, 1914, the first stage left Old Faithful Lodge at about 8 am. They rolled along enjoying the scenery until they were about nine miles from the lodge. That’s when a single gunman, his lower face covered by a neckerchief, stepped out in front of the coach holding a gun.

Guns were illegal in the park, so no one in or on the stage had one.

James C. Pinkston, who was visiting Yellowstone from Alabama with his wife and daughter described the incident to Salt Lake City reporters.

“We were just passing Shoshone point when suddenly the bandit appeared, stopped our driver and issue an order for the tourists to step out of the vehicle preparatory to holding a big ‘convention,’ over which he evidently intended to act as presiding minister.

“Naturally, we got out.

“Once on the ground, we had to deposit our money in a rude sack which he had furnished for the occasion. He told all of us to put in nothing but money, and if he saw any rings or other jewelry going in, he rudely threw it aside.”

The bandit herded all the passengers to a natural amphitheater and ordered them to sit. Soon, a second coach pulled up behind the first. The highwayman ordered everyone out. When they hesitated, according to Pinkston, the man said, “I bet if you heard a dinner bell ringing you wouldn’t hesitate like that. Now get out. We’re going to hold a calm peaceful convention and I want to enlist your aid.”

The dropping of cash into a sack was repeated, then repeated again when another coach pulled up.

When the fifth coach rumbled up, it presented a special opportunity. Two friends, Miss Estelle Hammond of London, and Miss Alice Cay of Sydney, Australia, were aboard. According to the Salt Lake Telegram the women had been visiting in untamed Australia and had arrived in the genteel United States just a few days before.

“We were never held up in wild Australia,” Miss Cay told the paper, which reported that she smiled about the adventure. She was able to take five photographs of the highwayman for her scrapbook.

Talking about her photographic escapade, Miss Cay said, “I was afraid to try at first. [Some men] said, ‘for heaven’s sake, don’t try it. He’ll shoot you.’ I tried, though, and really, I believe he rather like it. I believe he is, oh, what’s your American word for it, oh, yes, a flirt. I really do.

“He was chivalrous to the extreme. He ordered us to be perfectly comfortable and commanded us in threatening tones to make ourselves comfortable, saying that if we didn’t enjoy the procedure, he would blow our bodies into atoms. Oh, it was thrilling.”

For a hold-up story that needed no exaggeration, this one received quite a bit. One report stated that the Yellowstone Highwayman had held up as many as 300 tourists in 40 coaches for a haul of as much as $20,000. The real story was incredible enough. He held up 165 passengers on 15 coaches. The driver of coach number 16 saw what was going on ahead, turned around, and warned the oncoming stages.

The bandit ended up with less than $1,000 in cash, and a little over $100 in jewelry. Apparently, he decided to keep a few of the ladies’ trinkets.

It wasn’t excellent detective work that led to Trafton’s capture. It was a woman. Not the woman who took pictures of him, but a woman he knew well.

A few months after the robbery, when Trafton was back in Rupert, Minnie caught him with another woman. For her revenge, she located the Yellowstone loot that he had hidden in a barn and took it to authorities. After Ed was arrested, Minnie filed for divorce and moved her family to Ogden, Utah. She eventually remarried.

After spending nine months in the Cheyenne jail, Trafton sat for days through a trial that included some 50 witnesses, photographs of him during the robbery, and positive identification of the jewelry found in the barn by those who owned it. It took the jury 30 minutes to reach a guilty verdict. He was sentenced to spend five years at the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

After Trafton was convicted, special agent Melrose, who pops up now and again in this story, told the press that the Yellowstone Bandit had been a suspect in the kidnapping of Alonzo Ernest Empy, which I’ve written about before, and was part of a plot to kidnap Joseph F. Smith, the nephew of the Church of Latter Day Saints founder Joseph Smith, then serving as the sixth president of the church. Trafton wasn’t involved in the Empy kidnapping, as far as we know. Melrose believed that three men were plotting to take Smith, hide him away somewhere in the Jackson Hole area, and hold him for $100,000 in ransom.

After just a few months in prison Trafton wrote a letter to Special Agent Melrose, claiming that he was at death’s door and asking to be moved from Kansas to the prison in Colorado where he had recently resided following the theft of his mother’s money.

“It’s a hard job to put a ‘bull elk,’ who has lived in the open most of his life, into a closet and expect him to ‘make it.’” Trafton wrote to Melrose. “You’ve done your part, as any man with red blood in his veins would do, when he swore allegiance to Uncle Sam. But give me a chance for my life. It’s all I’ve got that’s worthwhile.”

The line about Melrose doing his part referenced the fact that the special agent, whom Trafton had befriended, was the man who escorted him to Cheyenne for trial.

Whether Melrose attempted to honor Trafton’s request is unknown. For the first time in his life, Ed Harrington Trafton served out his entire sentence.

Trafton got out of Leavenworth in 1920. There was nothing for him anymore in Driggs. He thought Hollywood might be interested in his story, so he travelled there in 1922 with that glowing letter about his past exploits from Melrose in his pocket.

That his life ended while he was enjoying an ice cream soda seems every bit as absurd as his claim that he was the model for The Virginian. Trafton’s life story is worthy of a book, but probably not one in which he was the hero.

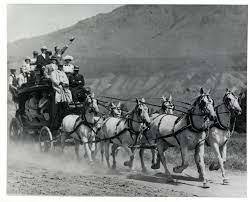

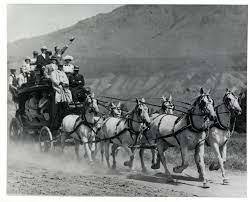

On the left, a Yellowstone observation coach that as part of the park's collection. On the right a coach in action from about the time of Trafton's exploits.

On the left, a Yellowstone observation coach that as part of the park's collection. On the right a coach in action from about the time of Trafton's exploits.

And now, after four days of build-up about Ed Trafton, we come to the heist that made him famous. We’ve followed him in and out of prison, trailed behind his rustled horses, and seen him betray his own mother over and over. Now we learn of the “Lone Highwayman of Yellowstone Park.”

Ed Trafton was nearing 60 in 1915, an age when most men would rather settle down and put rustling behind them. He had purchased a farm in Rupert with some of the money he had stolen from his mother. But he wanted at least one more heist before he gave up his guns.

Yellowstone National Park was country he knew well. One thing he knew about it was that in 1915 wealthy tourists who stayed at various establishments in the park toured in relative luxury, riding in spiffed up stages pulled by teams of horses. The practice was for these stages to leave every few minutes on the tour. Spacing them out assured that the well-dressed travelers did not have to endure dust from the stage ahead.

On Wednesday, July 29, 1914, the first stage left Old Faithful Lodge at about 8 am. They rolled along enjoying the scenery until they were about nine miles from the lodge. That’s when a single gunman, his lower face covered by a neckerchief, stepped out in front of the coach holding a gun.

Guns were illegal in the park, so no one in or on the stage had one.

James C. Pinkston, who was visiting Yellowstone from Alabama with his wife and daughter described the incident to Salt Lake City reporters.

“We were just passing Shoshone point when suddenly the bandit appeared, stopped our driver and issue an order for the tourists to step out of the vehicle preparatory to holding a big ‘convention,’ over which he evidently intended to act as presiding minister.

“Naturally, we got out.

“Once on the ground, we had to deposit our money in a rude sack which he had furnished for the occasion. He told all of us to put in nothing but money, and if he saw any rings or other jewelry going in, he rudely threw it aside.”

The bandit herded all the passengers to a natural amphitheater and ordered them to sit. Soon, a second coach pulled up behind the first. The highwayman ordered everyone out. When they hesitated, according to Pinkston, the man said, “I bet if you heard a dinner bell ringing you wouldn’t hesitate like that. Now get out. We’re going to hold a calm peaceful convention and I want to enlist your aid.”

The dropping of cash into a sack was repeated, then repeated again when another coach pulled up.

When the fifth coach rumbled up, it presented a special opportunity. Two friends, Miss Estelle Hammond of London, and Miss Alice Cay of Sydney, Australia, were aboard. According to the Salt Lake Telegram the women had been visiting in untamed Australia and had arrived in the genteel United States just a few days before.

“We were never held up in wild Australia,” Miss Cay told the paper, which reported that she smiled about the adventure. She was able to take five photographs of the highwayman for her scrapbook.

Talking about her photographic escapade, Miss Cay said, “I was afraid to try at first. [Some men] said, ‘for heaven’s sake, don’t try it. He’ll shoot you.’ I tried, though, and really, I believe he rather like it. I believe he is, oh, what’s your American word for it, oh, yes, a flirt. I really do.

“He was chivalrous to the extreme. He ordered us to be perfectly comfortable and commanded us in threatening tones to make ourselves comfortable, saying that if we didn’t enjoy the procedure, he would blow our bodies into atoms. Oh, it was thrilling.”

For a hold-up story that needed no exaggeration, this one received quite a bit. One report stated that the Yellowstone Highwayman had held up as many as 300 tourists in 40 coaches for a haul of as much as $20,000. The real story was incredible enough. He held up 165 passengers on 15 coaches. The driver of coach number 16 saw what was going on ahead, turned around, and warned the oncoming stages.

The bandit ended up with less than $1,000 in cash, and a little over $100 in jewelry. Apparently, he decided to keep a few of the ladies’ trinkets.

It wasn’t excellent detective work that led to Trafton’s capture. It was a woman. Not the woman who took pictures of him, but a woman he knew well.

A few months after the robbery, when Trafton was back in Rupert, Minnie caught him with another woman. For her revenge, she located the Yellowstone loot that he had hidden in a barn and took it to authorities. After Ed was arrested, Minnie filed for divorce and moved her family to Ogden, Utah. She eventually remarried.

After spending nine months in the Cheyenne jail, Trafton sat for days through a trial that included some 50 witnesses, photographs of him during the robbery, and positive identification of the jewelry found in the barn by those who owned it. It took the jury 30 minutes to reach a guilty verdict. He was sentenced to spend five years at the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

After Trafton was convicted, special agent Melrose, who pops up now and again in this story, told the press that the Yellowstone Bandit had been a suspect in the kidnapping of Alonzo Ernest Empy, which I’ve written about before, and was part of a plot to kidnap Joseph F. Smith, the nephew of the Church of Latter Day Saints founder Joseph Smith, then serving as the sixth president of the church. Trafton wasn’t involved in the Empy kidnapping, as far as we know. Melrose believed that three men were plotting to take Smith, hide him away somewhere in the Jackson Hole area, and hold him for $100,000 in ransom.

After just a few months in prison Trafton wrote a letter to Special Agent Melrose, claiming that he was at death’s door and asking to be moved from Kansas to the prison in Colorado where he had recently resided following the theft of his mother’s money.

“It’s a hard job to put a ‘bull elk,’ who has lived in the open most of his life, into a closet and expect him to ‘make it.’” Trafton wrote to Melrose. “You’ve done your part, as any man with red blood in his veins would do, when he swore allegiance to Uncle Sam. But give me a chance for my life. It’s all I’ve got that’s worthwhile.”

The line about Melrose doing his part referenced the fact that the special agent, whom Trafton had befriended, was the man who escorted him to Cheyenne for trial.

Whether Melrose attempted to honor Trafton’s request is unknown. For the first time in his life, Ed Harrington Trafton served out his entire sentence.

Trafton got out of Leavenworth in 1920. There was nothing for him anymore in Driggs. He thought Hollywood might be interested in his story, so he travelled there in 1922 with that glowing letter about his past exploits from Melrose in his pocket.

That his life ended while he was enjoying an ice cream soda seems every bit as absurd as his claim that he was the model for The Virginian. Trafton’s life story is worthy of a book, but probably not one in which he was the hero.

On the left, a Yellowstone observation coach that as part of the park's collection. On the right a coach in action from about the time of Trafton's exploits.

On the left, a Yellowstone observation coach that as part of the park's collection. On the right a coach in action from about the time of Trafton's exploits.

Published on May 14, 2021 04:00

May 13, 2021

A Legendary Highwayman, Part 4 of 5

Yesterday we left Ed and Minnie Trafton when they were Teton Valley entrepreneurs, shearing and dipping sheep, running a boarding house and saloon, and possibly expediting the transfer of livestock from one hapless owner to another without benefit of paperwork.

The sideline rustling business, for which Ed had already served a couple of sentences in the Idaho State Penitentiary, was starting to bring a little heat onto the Traftons. Some ranchers looked upon their herd shrinkage as an annoyance and part of the cost of doing business. But a couple of the cattlemen had begun to plot to catch Ed in the act.

It may have been good luck for Ed that his mother asked for his help in 1909, providing a good excuse to leave Teton Valley and let things cool down.

Annie Knight was the same mother from whom Ed had stolen money, a ham, and a horse for his grubstake in a failed attempt to get rich mining for gold in the Black Hills many years earlier. She was the same mother who allegedly bribed officials to get him out of prison.

Trafton’s forgiving mother asked he and Minnie to move to Denver to help her with her boarding house. Her husband, Ed’s stepfather, James Knight, was in poor health.

It was while running the Denver boarding house that Ed met Special Agent James Melrose, the U.S. Justice Department official who would one day write the glowing letter of reference that was found on Trafton when he died.

Melrose was fascinated by Trafton’s stories of the wild West. He learned that, according to Trafton, Ed was the inspiration for Owen Wister’s lead character in The Virginian. He heard tales of gunfights and cattle drives and narrow escapes. Melrose ate it up. To be fair, Trafton probably gave short shrift to his rustling exploits, if he mentioned them at all.

The special agent was so gullible, he probably didn’t even notice that Trafton was having an affair with Melrose’s wife in his spare time.

But all good things must end. In early 1910, James Knight passed away, leaving his wife Annie to collect on a $10,000 insurance policy.

Not trusting banks, Annie buried the money. Her loving son spent some time looking for it, to no avail. Eventually, Annie decided to trust a bank and to trust Ed Trafton to deposit the money.

Stand by for a big shock. Ed did not deposit the money. Writer Wayne Moss interviewed a grandson of Trafton’s to get family details for a story that ran in the Teton Valley Times in 2015. As Moss related it, Ed buried $4,000 in his own hiding spot in the backyard, hid $3,000 in a dresser drawer, intending it as a gift for his wife, and secreted away the remaining $3,000 under some floorboards.

Ed told his mother he had been robbed. No wait, that wasn’t it, he’d forgotten the money in a satchel he left on a trolly.

Annie Knight was not swayed by either story. She called the police, and they quickly found the $3,000 in Minnie’s drawer. Lickety split Ed and Minnie were behind bars.

Ed was convicted and sentenced to from 5 to 8 years in prison. Minnie, who protested her innocence, was convicted and sentenced to from 3 to 5 years. They would both reside in the Colorado State Penitentiary for the next couple of years.

The Trafton’s eldest daughter, Anna—probably lovingly named after the woman Ed stole $10,000 from—removed the $3,000 from beneath the floorboards and took her siblings to Pocatello to live. Minnie would join them upon her release in 1912. They opened a boarding house there.

Ed, who had a way of getting reduced sentences, was released in 1913. He dug up the remaining $4,000, collected his wife in Pocatello, and moved to Rupert where he was purchased a farm. (Note that some accounts say he worked on a Rupert farm, but did not own it)

Nearing 60, his thieving days were over.

Just kidding. Come back tomorrow for the final chapter in the story of Ed Trafton.

[image error] Ed Harington Trafton's Idaho State Penitentiary booking phono.

The sideline rustling business, for which Ed had already served a couple of sentences in the Idaho State Penitentiary, was starting to bring a little heat onto the Traftons. Some ranchers looked upon their herd shrinkage as an annoyance and part of the cost of doing business. But a couple of the cattlemen had begun to plot to catch Ed in the act.

It may have been good luck for Ed that his mother asked for his help in 1909, providing a good excuse to leave Teton Valley and let things cool down.

Annie Knight was the same mother from whom Ed had stolen money, a ham, and a horse for his grubstake in a failed attempt to get rich mining for gold in the Black Hills many years earlier. She was the same mother who allegedly bribed officials to get him out of prison.

Trafton’s forgiving mother asked he and Minnie to move to Denver to help her with her boarding house. Her husband, Ed’s stepfather, James Knight, was in poor health.

It was while running the Denver boarding house that Ed met Special Agent James Melrose, the U.S. Justice Department official who would one day write the glowing letter of reference that was found on Trafton when he died.

Melrose was fascinated by Trafton’s stories of the wild West. He learned that, according to Trafton, Ed was the inspiration for Owen Wister’s lead character in The Virginian. He heard tales of gunfights and cattle drives and narrow escapes. Melrose ate it up. To be fair, Trafton probably gave short shrift to his rustling exploits, if he mentioned them at all.

The special agent was so gullible, he probably didn’t even notice that Trafton was having an affair with Melrose’s wife in his spare time.

But all good things must end. In early 1910, James Knight passed away, leaving his wife Annie to collect on a $10,000 insurance policy.

Not trusting banks, Annie buried the money. Her loving son spent some time looking for it, to no avail. Eventually, Annie decided to trust a bank and to trust Ed Trafton to deposit the money.

Stand by for a big shock. Ed did not deposit the money. Writer Wayne Moss interviewed a grandson of Trafton’s to get family details for a story that ran in the Teton Valley Times in 2015. As Moss related it, Ed buried $4,000 in his own hiding spot in the backyard, hid $3,000 in a dresser drawer, intending it as a gift for his wife, and secreted away the remaining $3,000 under some floorboards.

Ed told his mother he had been robbed. No wait, that wasn’t it, he’d forgotten the money in a satchel he left on a trolly.

Annie Knight was not swayed by either story. She called the police, and they quickly found the $3,000 in Minnie’s drawer. Lickety split Ed and Minnie were behind bars.

Ed was convicted and sentenced to from 5 to 8 years in prison. Minnie, who protested her innocence, was convicted and sentenced to from 3 to 5 years. They would both reside in the Colorado State Penitentiary for the next couple of years.

The Trafton’s eldest daughter, Anna—probably lovingly named after the woman Ed stole $10,000 from—removed the $3,000 from beneath the floorboards and took her siblings to Pocatello to live. Minnie would join them upon her release in 1912. They opened a boarding house there.

Ed, who had a way of getting reduced sentences, was released in 1913. He dug up the remaining $4,000, collected his wife in Pocatello, and moved to Rupert where he was purchased a farm. (Note that some accounts say he worked on a Rupert farm, but did not own it)

Nearing 60, his thieving days were over.

Just kidding. Come back tomorrow for the final chapter in the story of Ed Trafton.

[image error] Ed Harington Trafton's Idaho State Penitentiary booking phono.

Published on May 13, 2021 04:00

May 12, 2021

A Legendary Highwayman, Part 3 of 5

As I wrote in previous posts, Ed Harrington Trafton was an outlaw and entrepreneur.

His escapades as the former were often ignored by locals while his business side was praised.

Trafton received a pardon from his 25-year sentence for horse stealing, serving just two. He got out of prison in 1889 and returned to the Teton Valley.

It wasn’t long until Ed found, inexplicably, that he had a surplus of horses that he needed to get rid of. He herded them to Hyrum, Utah where the locals wouldn’t recognize the altered brands. There he met 18-year-old Minnie Lyman. Ed, now 34, proposed to the daughter of the gentleman who was buying the horses.

The newlyweds moved to Colter Bay on Jackson Lake and set up their new home. Some sources say their main business there was working with rustlers to move stolen horses and cattle. It was at the place on Jackson Lake where Owen Wister, author of The Virginian, may have spent some time with Trafton.

After a few years at Jackson Lake, the Traftons moved back to the Teton Valley where their five children, four girls and a boy, were born.

In 1899, Ed Trafton was arrested for dynamiting the Brandon Building in St Anthony, which was under construction, allegedly acting as a hired bomber. The bomb broke windows nearby and damaged a lawyer’s office but did little damage to the stone structure that was the apparent target. Trafton, if he was the incompetent bomber, was acquitted of those charges.

1901 was a memorable year for the Traftons. In February, the family was startled by a bullet smashing through the window of their home and grazing Minnie. How could anyone have a beef with such a nice family?

Later that year, Trafton was caught rustling beef, again, and was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. He got out in two and returned to the Teton Valley where he seemed to focus more on his business side for a few years, including the boarding house and restaurant.

Trafton’s sheep shearing business was one of large scale. In 1904 he told the Teton Peak newspaper in St. Anthony that he expected to shear 125,000 sheep and noted that dipping vats would also be available.

Exciting as sheep dipping is, we’re going to leave the tale there for a day. Come back tomorrow when we get to the stories that made the sheep dipper famous. [image error] Trafton was a well-known sheep dipper in the Teton Valley.

His escapades as the former were often ignored by locals while his business side was praised.

Trafton received a pardon from his 25-year sentence for horse stealing, serving just two. He got out of prison in 1889 and returned to the Teton Valley.

It wasn’t long until Ed found, inexplicably, that he had a surplus of horses that he needed to get rid of. He herded them to Hyrum, Utah where the locals wouldn’t recognize the altered brands. There he met 18-year-old Minnie Lyman. Ed, now 34, proposed to the daughter of the gentleman who was buying the horses.

The newlyweds moved to Colter Bay on Jackson Lake and set up their new home. Some sources say their main business there was working with rustlers to move stolen horses and cattle. It was at the place on Jackson Lake where Owen Wister, author of The Virginian, may have spent some time with Trafton.

After a few years at Jackson Lake, the Traftons moved back to the Teton Valley where their five children, four girls and a boy, were born.

In 1899, Ed Trafton was arrested for dynamiting the Brandon Building in St Anthony, which was under construction, allegedly acting as a hired bomber. The bomb broke windows nearby and damaged a lawyer’s office but did little damage to the stone structure that was the apparent target. Trafton, if he was the incompetent bomber, was acquitted of those charges.

1901 was a memorable year for the Traftons. In February, the family was startled by a bullet smashing through the window of their home and grazing Minnie. How could anyone have a beef with such a nice family?

Later that year, Trafton was caught rustling beef, again, and was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. He got out in two and returned to the Teton Valley where he seemed to focus more on his business side for a few years, including the boarding house and restaurant.

Trafton’s sheep shearing business was one of large scale. In 1904 he told the Teton Peak newspaper in St. Anthony that he expected to shear 125,000 sheep and noted that dipping vats would also be available.

Exciting as sheep dipping is, we’re going to leave the tale there for a day. Come back tomorrow when we get to the stories that made the sheep dipper famous. [image error] Trafton was a well-known sheep dipper in the Teton Valley.

Published on May 12, 2021 04:00

May 11, 2021

A Legendary Highwayman, Part 2 of 5

Yesterday we started the story of Edwin B. Trafton with an account of his death and how his life was the possible inspiration for the novel The Virginian, by Owen Wister. Today we’ll look at the high and low points of that life. Mostly the low.

Born in New Brunswick, Canada in 1857 to immigrants from Liverpool, Edwin Burnham Trafton seemed bent on outlawry from an early age. A few years after his father’s death and his mother Annie’s marriage to a neighbor, James Knight, Ed found himself in Denver, a juvenile delinquent who had a habit of appropriating guns from the residents of his mother’s boarding house.

At around age 20 Ed decided to set out on his own. He left Annie Knight a note, stole $40, a smoked ham, and her best horse, and took off for the Black Hills in search of gold.

His taste for gold never left him, but mining it was not his preferred method of acquisition.

After striking out in the Black Hills gold rush, Trafton settled in the Teton Valley near present day Driggs in 1878. The following year he homesteaded in the valley along Milk Creek and started a variety of endeavors, including sheep shearing, and eventually operating a small store that included a saloon and boarding house.

Ed Trafton lived parallel lives. He ran his legitimate businesses while at the same time robbing other businesses and stealing livestock. This seemed to be widely known and widely tolerated.

Arrested for horse stealing in 1887, Ed was sent to the jail in Blackfoot to await trial along with his alleged partner in the crime, Lem Nickerson. The theft had occurred in the Teton Valley, but Blackfoot was the county seat of a much larger Bingham county at that time. Ed was going by the name Harrington then, but I will continue to call him Trafton to help readers through a confusing story.

Nickerson’s wife was visiting regularly in the weeks before the trial. She got to be such a regular visitor that the guards let down their, well, guard. She slipped a long six-shooter into the pocket of her spouse during visitation.

Soon after noon on June 22, 1887, the leisurely escape began. Guard William High looked down the hall to the jail and saw that he was also looking down the barrel of a 45. Nickerson demanded that the guard “throw up your hands and deliver me the keys to this jail or down and out you go.”

Trafton and Nickerson overpowered another deputy on duty and locked the two officers in a cell. The accused horse thieves poked around the county offices and found three other men to lock away.

Then it was time for Ed Harrington Trafton to pen a little note to Judge Hayes, who he was scheduled to appear before: “We are off for the hills and the mountains which we love so dearly. We are familiar with the mountain trails and the officers cannot catch us, for we are well mounted and well armed. You cannot get a crack at me this time and when I meet you again it will be in hell.”

Perhaps while Trafton was working on that note, Nickerson strolled from the courthouse to where his family was staying in Blackfoot to retrieve some horses stashed there by his brother, bringing them back to the jail.

It was nearing dusk by the time the men were ready to make their escape.

A Pocatello man named Hughes, accused of murder, was also locked up in the jail. Nickerson and Trafton freed him, perhaps to provide an additional diversion to pursuers. Hughes was a Black man. He was aware that Indians often sympathized with dark-skinned people who were in trouble with white men, so he made his way to a scattering of tepees south of town. To his delight, the Indians did take him in, putting ocher on his face and giving him native clothes to wear. He hung around Blackfoot in that disguise for a few days before hopping a train to Montana.

While Hughes was making friends with the Indians, the other escapees made their way to Willow Creek in the Blackfoot Mountains where they looked up an old acquaintance, Johnnie Heath. They had a leisurely breakfast with him the next day, then headed out. Trafton and Nickerson made their way for several days through the Wolverine country, and eventually headed north, planning to cross the Snake River near present day Heise Hot Springs. High water made the crossing too dangerous. With a posse now in hot pursuit, Trafton and Nickerson took refuge in the willows on Pool Island.

Law enforcement officials from several towns came together to smoke out the escapees. A several days siege ensued, the result of which was that Trafton was shot in the foot and both men surrendered.

Their fellow escapee, Hughes, was recognized in Butte, Montana and brought back to Blackfoot to face execution days later.

It’s likely that Ed Harrington Trafton regretted his snarky note to Judge Hayes. “Well, Mr. Harrington,” the judge said, “we have met again—but not in hell!” He then sentenced Harrington/Trafton to 25 years at hard labor in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Warden C.E. Arney, who took Trafton in at the penitentiary related a story years later that may shed some light on how the man led his parallel lives of businessman and outlaw. “Harrington was a clever fellow and aside from his outlaw traits was a pleasant companion, interesting and truthful. These traits elicited sympathy for him, and petitions soon circulated for his release. In 1888 I saw [him] in the penitentiary and in 1891 when I was running a newspaper in Rexburg, he was pardoned and I saw him in the wild pose of a cowboy, once more breathing the free mountain air, and astride a well gaited cayuse, ride down the streets of Rexburg wildly waving his broad brimmed hat at the friends who greeted him from the streets and store buildings, stopping only long enough to shake hands with those who had befriended him and then hurrying on to his old haunts in the Teton Basin and Jackson Hole Districts.”

Trafton had gotten out in two years, perhaps with the help of his mother who may have bribed someone. If so, she would come to regret that.

Tomorrow I’ll continue the story of the outlaw/entrepreneur. The Bingham County Courthouse was built in 1885. In 1887 Trafton was one of the men who escaped from the jail in the basement of the building.

The Bingham County Courthouse was built in 1885. In 1887 Trafton was one of the men who escaped from the jail in the basement of the building.

Born in New Brunswick, Canada in 1857 to immigrants from Liverpool, Edwin Burnham Trafton seemed bent on outlawry from an early age. A few years after his father’s death and his mother Annie’s marriage to a neighbor, James Knight, Ed found himself in Denver, a juvenile delinquent who had a habit of appropriating guns from the residents of his mother’s boarding house.

At around age 20 Ed decided to set out on his own. He left Annie Knight a note, stole $40, a smoked ham, and her best horse, and took off for the Black Hills in search of gold.

His taste for gold never left him, but mining it was not his preferred method of acquisition.

After striking out in the Black Hills gold rush, Trafton settled in the Teton Valley near present day Driggs in 1878. The following year he homesteaded in the valley along Milk Creek and started a variety of endeavors, including sheep shearing, and eventually operating a small store that included a saloon and boarding house.

Ed Trafton lived parallel lives. He ran his legitimate businesses while at the same time robbing other businesses and stealing livestock. This seemed to be widely known and widely tolerated.

Arrested for horse stealing in 1887, Ed was sent to the jail in Blackfoot to await trial along with his alleged partner in the crime, Lem Nickerson. The theft had occurred in the Teton Valley, but Blackfoot was the county seat of a much larger Bingham county at that time. Ed was going by the name Harrington then, but I will continue to call him Trafton to help readers through a confusing story.

Nickerson’s wife was visiting regularly in the weeks before the trial. She got to be such a regular visitor that the guards let down their, well, guard. She slipped a long six-shooter into the pocket of her spouse during visitation.

Soon after noon on June 22, 1887, the leisurely escape began. Guard William High looked down the hall to the jail and saw that he was also looking down the barrel of a 45. Nickerson demanded that the guard “throw up your hands and deliver me the keys to this jail or down and out you go.”

Trafton and Nickerson overpowered another deputy on duty and locked the two officers in a cell. The accused horse thieves poked around the county offices and found three other men to lock away.

Then it was time for Ed Harrington Trafton to pen a little note to Judge Hayes, who he was scheduled to appear before: “We are off for the hills and the mountains which we love so dearly. We are familiar with the mountain trails and the officers cannot catch us, for we are well mounted and well armed. You cannot get a crack at me this time and when I meet you again it will be in hell.”

Perhaps while Trafton was working on that note, Nickerson strolled from the courthouse to where his family was staying in Blackfoot to retrieve some horses stashed there by his brother, bringing them back to the jail.

It was nearing dusk by the time the men were ready to make their escape.

A Pocatello man named Hughes, accused of murder, was also locked up in the jail. Nickerson and Trafton freed him, perhaps to provide an additional diversion to pursuers. Hughes was a Black man. He was aware that Indians often sympathized with dark-skinned people who were in trouble with white men, so he made his way to a scattering of tepees south of town. To his delight, the Indians did take him in, putting ocher on his face and giving him native clothes to wear. He hung around Blackfoot in that disguise for a few days before hopping a train to Montana.

While Hughes was making friends with the Indians, the other escapees made their way to Willow Creek in the Blackfoot Mountains where they looked up an old acquaintance, Johnnie Heath. They had a leisurely breakfast with him the next day, then headed out. Trafton and Nickerson made their way for several days through the Wolverine country, and eventually headed north, planning to cross the Snake River near present day Heise Hot Springs. High water made the crossing too dangerous. With a posse now in hot pursuit, Trafton and Nickerson took refuge in the willows on Pool Island.

Law enforcement officials from several towns came together to smoke out the escapees. A several days siege ensued, the result of which was that Trafton was shot in the foot and both men surrendered.

Their fellow escapee, Hughes, was recognized in Butte, Montana and brought back to Blackfoot to face execution days later.

It’s likely that Ed Harrington Trafton regretted his snarky note to Judge Hayes. “Well, Mr. Harrington,” the judge said, “we have met again—but not in hell!” He then sentenced Harrington/Trafton to 25 years at hard labor in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Warden C.E. Arney, who took Trafton in at the penitentiary related a story years later that may shed some light on how the man led his parallel lives of businessman and outlaw. “Harrington was a clever fellow and aside from his outlaw traits was a pleasant companion, interesting and truthful. These traits elicited sympathy for him, and petitions soon circulated for his release. In 1888 I saw [him] in the penitentiary and in 1891 when I was running a newspaper in Rexburg, he was pardoned and I saw him in the wild pose of a cowboy, once more breathing the free mountain air, and astride a well gaited cayuse, ride down the streets of Rexburg wildly waving his broad brimmed hat at the friends who greeted him from the streets and store buildings, stopping only long enough to shake hands with those who had befriended him and then hurrying on to his old haunts in the Teton Basin and Jackson Hole Districts.”

Trafton had gotten out in two years, perhaps with the help of his mother who may have bribed someone. If so, she would come to regret that.

Tomorrow I’ll continue the story of the outlaw/entrepreneur.

The Bingham County Courthouse was built in 1885. In 1887 Trafton was one of the men who escaped from the jail in the basement of the building.

The Bingham County Courthouse was built in 1885. In 1887 Trafton was one of the men who escaped from the jail in the basement of the building.

Published on May 11, 2021 04:00

May 10, 2021

A Legendary Highwayman, Part 1 of 5

Starting at the beginning is so conventional in storytelling. In recognition of the irregular nature of this tale’s subject, I’m going to start at the end. On top of that, I’m going to start with something that doesn’t even seem to relate to the subject.

I always thought it odd that the book many scholars consider the first Western novel was called The Virginian. It is set in Wyoming where the lead character, who was born in Virginia, works as a cowboy. He is never referred to by name, only as The Virginian.

The author, at first glance, seems like an odd one to have invented the genre. Owen Wister was born in Philadelphia, attended schools in Great Britain and Switzerland, and ultimately graduated from Harvard, where he was a Hasty Pudding member. He studied music for a couple of years in a Paris conservatory before turning to the law, and eventually to writing.

Wister became friends with Teddy Roosevelt and, like Roosevelt, spent many summers in the West, mostly in Wyoming.

The Virginian was a monster hit, reprinted fourteen times in 1902, the year it came out. It remains one of the 50 top-selling works of fiction.

So, the author was from Philadelphia, the book was set in Wyoming, where they named a mountain after Wister, and this is a blog about Idaho history. What’s the connection?

Possibly none. However, one-time Idaho State Penitentiary Warden C.E. Arney insisted that Ed Harrington Trafton, one-time inmate of his prison, was the man Wister used as his model for the hero in Wister’s story. That according to an article in the Idaho Statesman of September 17, 1922.

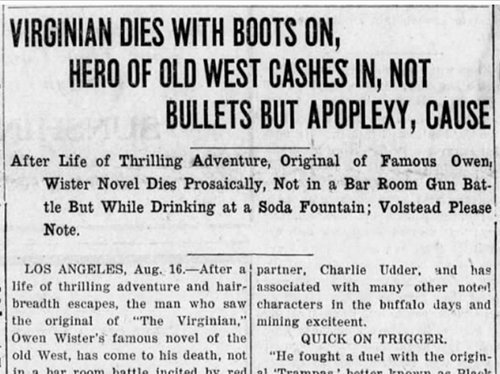

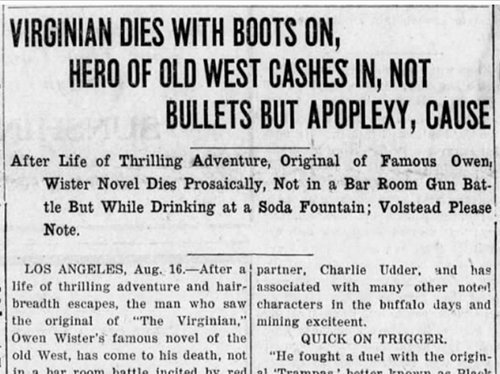

It wasn’t just the Statesman making this claim. On August 16, 1922, the Los Angeles Times ran a story with the stacked headline:

“THE VIRGINIAN”

DIES SUDDENLY

---

Owen Wister Novel Hero

Was Real Pioneer

---

Blazed First Trails Into

Jackson Hole Country

---

Ed Trafton Whacked Bulls

With Buffalo Bill

As proof of the connection, the Times offered a letter of introduction found on Trafton and written by James W. Melrose, who was a special agent in the Department of Justice for 16 years in Denver.

“This will introduce Edwin B. Trafton,” the letter states, “better known as ‘Ed Harrington.’”

“Mr. Trafton is the man from whom Owen Wister modeled the character, The Virginian, in his famous story of that name.”

Melrose went on to laud Trafton/Harrington as a well-known guide for 35 years in the Yellowstone country and a prolific big game hunter. According to the letter he built the first log cabin and blazed the first trails there in 1880. Harrington, Melrose said, was one of the first into the Black Hills for the gold rush there in 1875. He “whacked bulls out of old Cheyenne with the celebrated Buffalo Bill Cody.”

Perhaps the most important detail on his resume, as far as the Virginian connection goes, was that “He fought a duel with the original ‘Trampas,’ better known as Black Tex, who had given Ed until sundown to leave camp.”

Trampas was the name of the villain in The Virginian.

Left out of the Melrose letter were the multiple arrests of Trafton/Harrington, his history as a highwayman, and that time he stole $10,000 from his mother.

Did the author use Trafton/Harrington as the model for one of his characters? Given the man’s shady side, maybe he was the model for Trampas, the bad guy. Trampas and Trafton are a bit similar.

Wister himself never said that the Virginian was modeled after any single person.

The Times noted that, “The man whose adventurous life inspired Owen Wister to write The Virginian, one of the most popular stories of the pioneer West, dropped dead at Second Street and Broadway late yesterday afternoon while drinking an ice cream soda.” The cause of death was listed as apoplexy. He was 64 or 65 and is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California.

And thus, with Trafton’s end, we begin his story. It will continue with tomorrow’s post.

I always thought it odd that the book many scholars consider the first Western novel was called The Virginian. It is set in Wyoming where the lead character, who was born in Virginia, works as a cowboy. He is never referred to by name, only as The Virginian.

The author, at first glance, seems like an odd one to have invented the genre. Owen Wister was born in Philadelphia, attended schools in Great Britain and Switzerland, and ultimately graduated from Harvard, where he was a Hasty Pudding member. He studied music for a couple of years in a Paris conservatory before turning to the law, and eventually to writing.

Wister became friends with Teddy Roosevelt and, like Roosevelt, spent many summers in the West, mostly in Wyoming.

The Virginian was a monster hit, reprinted fourteen times in 1902, the year it came out. It remains one of the 50 top-selling works of fiction.

So, the author was from Philadelphia, the book was set in Wyoming, where they named a mountain after Wister, and this is a blog about Idaho history. What’s the connection?

Possibly none. However, one-time Idaho State Penitentiary Warden C.E. Arney insisted that Ed Harrington Trafton, one-time inmate of his prison, was the man Wister used as his model for the hero in Wister’s story. That according to an article in the Idaho Statesman of September 17, 1922.

It wasn’t just the Statesman making this claim. On August 16, 1922, the Los Angeles Times ran a story with the stacked headline:

“THE VIRGINIAN”

DIES SUDDENLY

---

Owen Wister Novel Hero

Was Real Pioneer

---

Blazed First Trails Into

Jackson Hole Country

---

Ed Trafton Whacked Bulls

With Buffalo Bill

As proof of the connection, the Times offered a letter of introduction found on Trafton and written by James W. Melrose, who was a special agent in the Department of Justice for 16 years in Denver.

“This will introduce Edwin B. Trafton,” the letter states, “better known as ‘Ed Harrington.’”

“Mr. Trafton is the man from whom Owen Wister modeled the character, The Virginian, in his famous story of that name.”

Melrose went on to laud Trafton/Harrington as a well-known guide for 35 years in the Yellowstone country and a prolific big game hunter. According to the letter he built the first log cabin and blazed the first trails there in 1880. Harrington, Melrose said, was one of the first into the Black Hills for the gold rush there in 1875. He “whacked bulls out of old Cheyenne with the celebrated Buffalo Bill Cody.”

Perhaps the most important detail on his resume, as far as the Virginian connection goes, was that “He fought a duel with the original ‘Trampas,’ better known as Black Tex, who had given Ed until sundown to leave camp.”

Trampas was the name of the villain in The Virginian.

Left out of the Melrose letter were the multiple arrests of Trafton/Harrington, his history as a highwayman, and that time he stole $10,000 from his mother.

Did the author use Trafton/Harrington as the model for one of his characters? Given the man’s shady side, maybe he was the model for Trampas, the bad guy. Trampas and Trafton are a bit similar.

Wister himself never said that the Virginian was modeled after any single person.

The Times noted that, “The man whose adventurous life inspired Owen Wister to write The Virginian, one of the most popular stories of the pioneer West, dropped dead at Second Street and Broadway late yesterday afternoon while drinking an ice cream soda.” The cause of death was listed as apoplexy. He was 64 or 65 and is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California.

And thus, with Trafton’s end, we begin his story. It will continue with tomorrow’s post.

Published on May 10, 2021 04:00