Rick Just's Blog, page 127

May 9, 2021

Famous Philo

When Philo T. Farnsworth appeared on the 1950s TV show, "I've Got a Secret," he leaned over and whispered his secret in the game show host's ear. When the secret was flashed on the screen for the audience and viewers at home, there was a lot of oohing and ahhing. Philo Taylor Farnsworth's secret was amazing. He had invented television. Perhaps even more amazing, he had done it when he was a high school student in Rigby, Idaho in 1922.

As a high school student, Farnsworth had recently heard radio broadcasts for the first time, and he was enchanted with the medium. But, wouldn't it be great if you could send pictures through the air, too? The young inventor sketched his idea for the cathode ray tube on a high school blackboard. That tube became the basis for modern television.

At the age of 20, Farnsworth produced the first all-electronic television image. In 1930, he received the first patent for television.

The former Rigby High School student went on to invent the first simple electron microscope. He did pioneering work on radar, black light viewing, and the peaceful use of atomic energy.

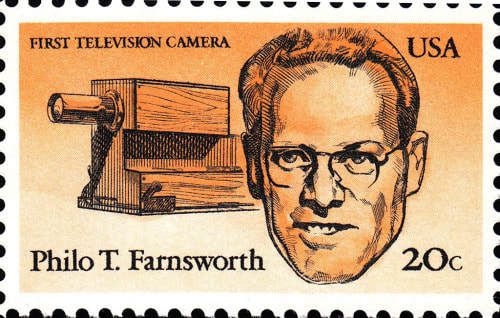

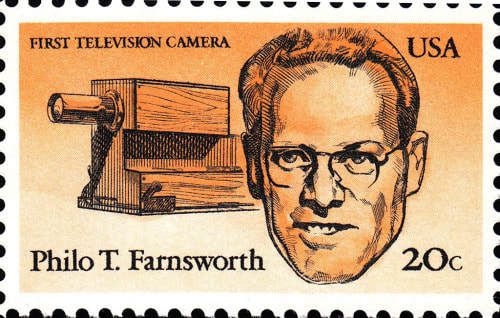

In all, Philo T. Farnsworth held over 300 U.S. and foreign patents. In 1983 the inventor was honored with a postage stamp. He is one of only three Idahoans so honored.

You can visit the Farnsworth TV and Pioneer Museum in Rigby, if you’d like to learn more.

As a high school student, Farnsworth had recently heard radio broadcasts for the first time, and he was enchanted with the medium. But, wouldn't it be great if you could send pictures through the air, too? The young inventor sketched his idea for the cathode ray tube on a high school blackboard. That tube became the basis for modern television.

At the age of 20, Farnsworth produced the first all-electronic television image. In 1930, he received the first patent for television.

The former Rigby High School student went on to invent the first simple electron microscope. He did pioneering work on radar, black light viewing, and the peaceful use of atomic energy.

In all, Philo T. Farnsworth held over 300 U.S. and foreign patents. In 1983 the inventor was honored with a postage stamp. He is one of only three Idahoans so honored.

You can visit the Farnsworth TV and Pioneer Museum in Rigby, if you’d like to learn more.

Published on May 09, 2021 04:00

May 8, 2021

Four Trains, Two Crashes, Part 2

Yesterday I wrote about a deadly head-on collision between two trains near American Falls in 1949. Today you'll learn about a second crash that occurred on the same line in 1951, and learn about a possible cause of both wrecks.

The second, eerily similar head-on collision between trains in Idaho occurred at Orchard, about 30 miles southeast of Boise on November 25, 1951. This time, both engines were diesel, and both were moving. The crew in the westbound freight spotted the oncoming engines and made an emergency stop. As that train was coming to a halt, Brakeman Ted Royter leapt from the four-engine train and ran to pull a switch that would route the eastbound engines onto a spur line. He arrived too late.

The grinding crash killed three crewmen in the lead eastbound engine and two in the westbound diesel cab. Of the 185 cars being pulled by the engines, 43 of them derailed, tearing up tracks as they tumbled and skidded. Three men in the caboose of the eastbound train escaped injury, as did two men in the westbound train’s caboose.

The sensational wreck, which happened on a Sunday, brought out carloads of people from Boise to see the pile-up. Police estimated that 5,000 people came to see the aftermath of the collision. A Boise camera club would later hold a special meeting to show photos club members had taken. (Note: If anyone has one, please post)

In both of the train wrecks all the crewmembers who might have shed some light on what happened perished in the collisions. There was no evidence that either of the engineers of the speeding trains had attempted to slow down.

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) investigated both wrecks without coming to a conclusion about the cause of either. But after the second collision the ICC “indulged in speculation,” according to the April 21, 1952 issue of Railway Age, a trade publication for the railroad industry. The investigators thought conditions might have been right for the occupants of both cabs of the diesel-electric locomotives to have been overcome by toxic gases seeping in from the train’s exhaust.

This speculation was bolstered by testimony of the operator at the Orchard station who tried to signal the speeding train to stop. It blew through the station without slowing down. The station operator did not see anyone in the cab and noted that all the windows and doors were closed.

The ICC’s report included weather conditions that indicated that the exhaust from the train could have travelled along with the engines because of the speed and direction of winds, finding its way into air vents. Under those conditions carbon monoxide poisoning could happen quickly and without preliminary symptoms. An autopsy had not been conducted on the engineers in either crash, so determining the exact cause of their incapacity—if they were indeed unable to control the engines—could not be determined. The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

The second, eerily similar head-on collision between trains in Idaho occurred at Orchard, about 30 miles southeast of Boise on November 25, 1951. This time, both engines were diesel, and both were moving. The crew in the westbound freight spotted the oncoming engines and made an emergency stop. As that train was coming to a halt, Brakeman Ted Royter leapt from the four-engine train and ran to pull a switch that would route the eastbound engines onto a spur line. He arrived too late.

The grinding crash killed three crewmen in the lead eastbound engine and two in the westbound diesel cab. Of the 185 cars being pulled by the engines, 43 of them derailed, tearing up tracks as they tumbled and skidded. Three men in the caboose of the eastbound train escaped injury, as did two men in the westbound train’s caboose.

The sensational wreck, which happened on a Sunday, brought out carloads of people from Boise to see the pile-up. Police estimated that 5,000 people came to see the aftermath of the collision. A Boise camera club would later hold a special meeting to show photos club members had taken. (Note: If anyone has one, please post)

In both of the train wrecks all the crewmembers who might have shed some light on what happened perished in the collisions. There was no evidence that either of the engineers of the speeding trains had attempted to slow down.

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) investigated both wrecks without coming to a conclusion about the cause of either. But after the second collision the ICC “indulged in speculation,” according to the April 21, 1952 issue of Railway Age, a trade publication for the railroad industry. The investigators thought conditions might have been right for the occupants of both cabs of the diesel-electric locomotives to have been overcome by toxic gases seeping in from the train’s exhaust.

This speculation was bolstered by testimony of the operator at the Orchard station who tried to signal the speeding train to stop. It blew through the station without slowing down. The station operator did not see anyone in the cab and noted that all the windows and doors were closed.

The ICC’s report included weather conditions that indicated that the exhaust from the train could have travelled along with the engines because of the speed and direction of winds, finding its way into air vents. Under those conditions carbon monoxide poisoning could happen quickly and without preliminary symptoms. An autopsy had not been conducted on the engineers in either crash, so determining the exact cause of their incapacity—if they were indeed unable to control the engines—could not be determined.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

Published on May 08, 2021 04:00

May 7, 2021

Four Trains, Two Crashes, Part 1

In 1949, and again in 1951, head-on train crashes in Southern Idaho made headlines.

The first collision took place at 4:05 a.m. on January 30 in a lava rock cut-through about six miles west of American Falls. A westbound steam locomotive had been trying to climb the grade with little success, losing traction until the train came to a full stop. Crew members had reported their difficulty and noticed that a nearby signal had turned yellow. Engineer William Cramer wondered at first if a second locomotive had been sent from Pocatello to help them get up the grade. His story appeared in the Idaho State Journal on January 31.

“Then I saw the other freight about one half mile ahead of us as it rounded a curve,” Cramer said. “I knew it couldn’t stop in that short distance downhill, so I yelled to the fireman and brakeman, ‘get off, get off’

“They were working about five feet away, but they knew by my voice that we had to get off quick.”

The three jumped from the gangway of the cab and scrambled through about three feet of snow, getting about 30 feet from their abandoned engine.

“It seemed like Providence that we jumped on the south side,” Cramer said, “because most of the box cars piled up on the north side of our locomotive after the diesel telescoped into it.”

And there’s a point to remember. The stalled westbound engine was steam powered, while the speeding eastbound locomotive was powered by diesel.

The three trainmen in the diesel died in the smashup. The three who had jumped from the steam engine lived to tell the story.

Crews worked quickly to clear the tracks of the locomotives and 24 freight cars that had derailed. Railroad authorities set up a shuttle bus service from Pocatello to Shoshone to get some 400 people from scheduled passenger trains around the wreck. The line was cleared the next day.

Early estimates of the damage caused by the head-on collision were in excess of $1 million, making it Idaho’s most expensive train accident to date.

Tomorrow, I'll tell you about the 1951 crash and a possible cause of both collisions.

The first collision took place at 4:05 a.m. on January 30 in a lava rock cut-through about six miles west of American Falls. A westbound steam locomotive had been trying to climb the grade with little success, losing traction until the train came to a full stop. Crew members had reported their difficulty and noticed that a nearby signal had turned yellow. Engineer William Cramer wondered at first if a second locomotive had been sent from Pocatello to help them get up the grade. His story appeared in the Idaho State Journal on January 31.

“Then I saw the other freight about one half mile ahead of us as it rounded a curve,” Cramer said. “I knew it couldn’t stop in that short distance downhill, so I yelled to the fireman and brakeman, ‘get off, get off’

“They were working about five feet away, but they knew by my voice that we had to get off quick.”

The three jumped from the gangway of the cab and scrambled through about three feet of snow, getting about 30 feet from their abandoned engine.

“It seemed like Providence that we jumped on the south side,” Cramer said, “because most of the box cars piled up on the north side of our locomotive after the diesel telescoped into it.”

And there’s a point to remember. The stalled westbound engine was steam powered, while the speeding eastbound locomotive was powered by diesel.

The three trainmen in the diesel died in the smashup. The three who had jumped from the steam engine lived to tell the story.

Crews worked quickly to clear the tracks of the locomotives and 24 freight cars that had derailed. Railroad authorities set up a shuttle bus service from Pocatello to Shoshone to get some 400 people from scheduled passenger trains around the wreck. The line was cleared the next day.

Early estimates of the damage caused by the head-on collision were in excess of $1 million, making it Idaho’s most expensive train accident to date.

Tomorrow, I'll tell you about the 1951 crash and a possible cause of both collisions.

Published on May 07, 2021 04:00

May 6, 2021

Grays Lake

First, Grays Lake isn’t a lake. It’s a “high elevation, 22,000-acre bulrush marsh” according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services webpage about the site in Southeastern Idaho. It’s located about 40 miles northeast of Soda Springs.

Much of the refuge was set aside in 1908 by the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes to use for an irrigation project. Water is drawn down annually in the spring for irrigation, taking out all but about six inches of water. In many years the whole marsh can dry up in the summer.

The unnatural hydrology isn’t always ideal for birds, but there have still been 250 species recorded at the refuge. About 100 of those are known to nest there. Notably, Grays Lake is typically home to about 200 nesting pairs of sandhill cranes. That’s the largest nesting population of the species in the world.

Grays Lake was named for mountain man John Grey. If you’re scratching your head about why he was named Grey and the lake is Grays Lake—with an a—there is much more to trouble your gray or grey hair over than that. The mountain man was also known as Ignace Hatchiorauquasha. That last name throws my spellchecker into a desolate land where it finds no road signs. Further, on many early maps Grays Lake is marked as Days Lake. Some thought it was named for John Day, an early trapper on the Astor Expedition. He has a town in Oregon named for him, so no sobbing.

But about that name, Hatchiorauquasha. It’s Iroquois. Gray/Grey/Hatchiorauquasha was half Scottish and half Iroquois. He chose the name Ignace because he considered St. Ignatius his patron saint.

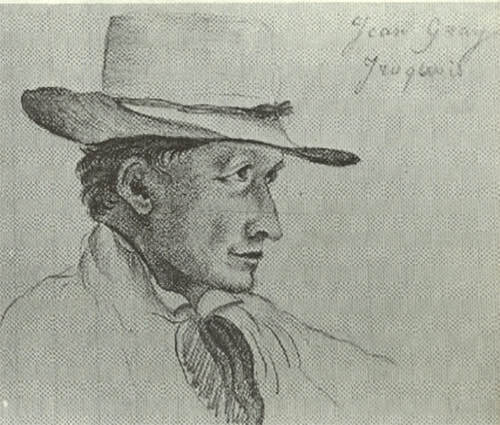

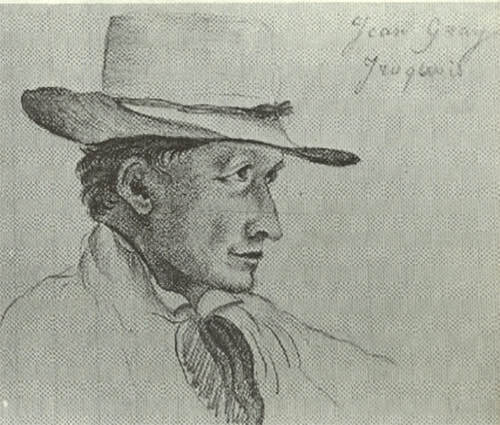

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who travelled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who travelled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Much of the refuge was set aside in 1908 by the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes to use for an irrigation project. Water is drawn down annually in the spring for irrigation, taking out all but about six inches of water. In many years the whole marsh can dry up in the summer.

The unnatural hydrology isn’t always ideal for birds, but there have still been 250 species recorded at the refuge. About 100 of those are known to nest there. Notably, Grays Lake is typically home to about 200 nesting pairs of sandhill cranes. That’s the largest nesting population of the species in the world.

Grays Lake was named for mountain man John Grey. If you’re scratching your head about why he was named Grey and the lake is Grays Lake—with an a—there is much more to trouble your gray or grey hair over than that. The mountain man was also known as Ignace Hatchiorauquasha. That last name throws my spellchecker into a desolate land where it finds no road signs. Further, on many early maps Grays Lake is marked as Days Lake. Some thought it was named for John Day, an early trapper on the Astor Expedition. He has a town in Oregon named for him, so no sobbing.

But about that name, Hatchiorauquasha. It’s Iroquois. Gray/Grey/Hatchiorauquasha was half Scottish and half Iroquois. He chose the name Ignace because he considered St. Ignatius his patron saint.

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who travelled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who travelled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Published on May 06, 2021 04:00

May 5, 2021

Doc Roach

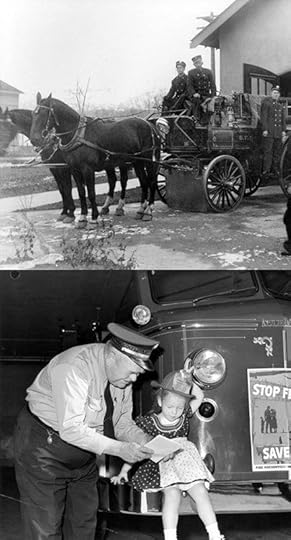

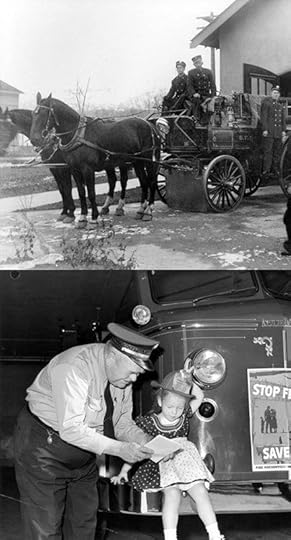

Not many public servants reach a measure of fame, even in their home towns. W.F. “Doc” Roach did. Roach started his career with the Boise Fire Department in 1910 when fire engines were pulled by horses, and didn’t retire until 1965. The top picture, below, taken in 1912, shows him on the left, seated on the fire wagon at Boise Fire Station Number 2 in the North End.

Roach served five years as one of Boise’s first motorcycle police officers, but served the rest of his 54-year career with Boise Fire. Roach was a dispatcher for the fire department from 1922 to 1947, when he became the city’s fire marshal, a position he stayed in until his retirement.

Roach was well known in the city because of his efforts at fire prevention, including public campaigns. In the bottom photo Doc Roach stands with the winner of the 1957 “Miss Sparky” competition that was held as part of Fire Prevention Week. Sarah Jane Benson was “Miss Sparky” that year.

Doc Roach shot and collected hundreds of photos over his career, creating a precious resource for historians. The two featured photos are from the Doc Roach Fire Collection Courtesy of Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

Roach served five years as one of Boise’s first motorcycle police officers, but served the rest of his 54-year career with Boise Fire. Roach was a dispatcher for the fire department from 1922 to 1947, when he became the city’s fire marshal, a position he stayed in until his retirement.

Roach was well known in the city because of his efforts at fire prevention, including public campaigns. In the bottom photo Doc Roach stands with the winner of the 1957 “Miss Sparky” competition that was held as part of Fire Prevention Week. Sarah Jane Benson was “Miss Sparky” that year.

Doc Roach shot and collected hundreds of photos over his career, creating a precious resource for historians. The two featured photos are from the Doc Roach Fire Collection Courtesy of Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

Published on May 05, 2021 04:00

May 4, 2021

Bud the Dog

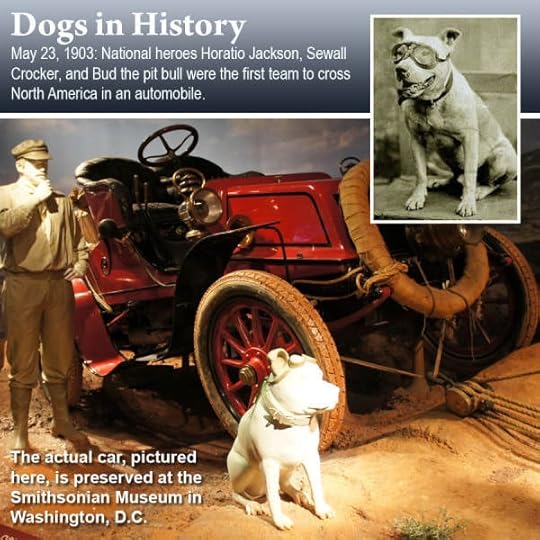

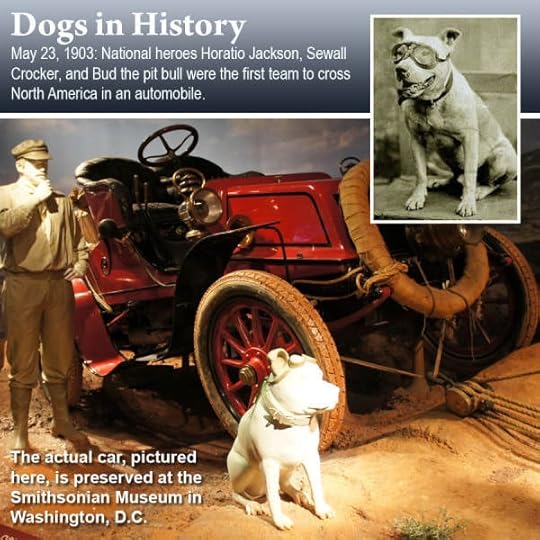

I asked for suggestions about dogs in Idaho history and got a good one from Jeff Schrade. I hadn’t heard about Bud the motoring pit bull, before.

The story starts on May 23, 1903, in San Francisco when Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson and Sewall Crocker climbed into the front seat a of second-hand cherry-red Winton touring car and set out for New York City. The trip started as a $50 bar bet. Jackson, who had little experience with automobiles, was challenged on his statement that an automobile could make it coast-to-coast in 90 days. He took the bet, bought the car, and hired Crocker to go along with him as a driver and mechanic.

There were no road maps back then. There were barely roads. Only about 150 miles of pavement existed in the country, all of that within city limits.

The old saw about someone having more money than sense might have applied to Jackson. This was a spur-of-the-moment adventure that should have ended in disaster. Instead, it became a string of small disasters, flat tires, broken parts, and gasoline shortages, that piled up to make a success.

I found only one mention of the trip in an Idaho newspaper while it was taking place. There was a brief story on the front page of the Montpelier Examiner on Friday, June, 19, 1903. Headlined “A Curiosity for this City,” the short piece focused more on the fact the Winton was the first automobile to appear in Montpelier than the trip itself.

Nelson didn’t start getting much newspaper coverage until he had made it a little further east. By the time he hit Chicago on July 17, he got a grand reception from city officials. Publicity for the stunt built with a stop in Cleveland, where the Winton had been built. Outside of Buffalo all three riders were thrown out of the car in a little accident, but none were hurt.

Three? Nelson, of course, and Crocker… And Bud. It seems that when the humans left Caldwell, Idaho on June 12, Nelson discovered he’d left his coat behind at the hotel. They went back to get it and encountered a man with a bull dog along the way. The man suggested that they really needed a mascot for their trip. Nelson had been looking for one, so paid the man $15 and got Bud to climb aboard.

Bud became the star of the trip because, well, dog. And dog with driving goggles. The dust could be irritating on the eyes when you were speeding along at 15 or 20 MPH with no windshield. Bud didn’t seem to mind the goggles and he loved riding in the car.

The two guys and a dog rolled into New York City at 4:30 in the morning Sunday, July 26, 63 days, 12 hours and 30 minutes after leaving San Francisco. Nelson reportedly never did bother to collect on his bet. He spent $8,000 making himself and his dog famous. A 1903 Winton, along with a depiction of Nelson and Bud the dog tells the story of the first cross-county auto trip at the National Museum of American History in Washington, DC.

Ken Burns did a series for PBS on the adventure, called Horatio’s Drive in 2003, which can found on YouTube.

The story starts on May 23, 1903, in San Francisco when Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson and Sewall Crocker climbed into the front seat a of second-hand cherry-red Winton touring car and set out for New York City. The trip started as a $50 bar bet. Jackson, who had little experience with automobiles, was challenged on his statement that an automobile could make it coast-to-coast in 90 days. He took the bet, bought the car, and hired Crocker to go along with him as a driver and mechanic.

There were no road maps back then. There were barely roads. Only about 150 miles of pavement existed in the country, all of that within city limits.

The old saw about someone having more money than sense might have applied to Jackson. This was a spur-of-the-moment adventure that should have ended in disaster. Instead, it became a string of small disasters, flat tires, broken parts, and gasoline shortages, that piled up to make a success.

I found only one mention of the trip in an Idaho newspaper while it was taking place. There was a brief story on the front page of the Montpelier Examiner on Friday, June, 19, 1903. Headlined “A Curiosity for this City,” the short piece focused more on the fact the Winton was the first automobile to appear in Montpelier than the trip itself.

Nelson didn’t start getting much newspaper coverage until he had made it a little further east. By the time he hit Chicago on July 17, he got a grand reception from city officials. Publicity for the stunt built with a stop in Cleveland, where the Winton had been built. Outside of Buffalo all three riders were thrown out of the car in a little accident, but none were hurt.

Three? Nelson, of course, and Crocker… And Bud. It seems that when the humans left Caldwell, Idaho on June 12, Nelson discovered he’d left his coat behind at the hotel. They went back to get it and encountered a man with a bull dog along the way. The man suggested that they really needed a mascot for their trip. Nelson had been looking for one, so paid the man $15 and got Bud to climb aboard.

Bud became the star of the trip because, well, dog. And dog with driving goggles. The dust could be irritating on the eyes when you were speeding along at 15 or 20 MPH with no windshield. Bud didn’t seem to mind the goggles and he loved riding in the car.

The two guys and a dog rolled into New York City at 4:30 in the morning Sunday, July 26, 63 days, 12 hours and 30 minutes after leaving San Francisco. Nelson reportedly never did bother to collect on his bet. He spent $8,000 making himself and his dog famous. A 1903 Winton, along with a depiction of Nelson and Bud the dog tells the story of the first cross-county auto trip at the National Museum of American History in Washington, DC.

Ken Burns did a series for PBS on the adventure, called Horatio’s Drive in 2003, which can found on YouTube.

Published on May 04, 2021 04:00

May 3, 2021

Red is Dead

(Note: Today I’m running a guest blog written by Ben Knapp. Ben grew up in New Plymouth and lives in Boise. He has an associate degree from the College of Western Idaho and is a senior history major at BSU. Ben is the History Day associate coordinator for the Idaho State Historical Society. This semester he has been interning for Speaking of Idaho)

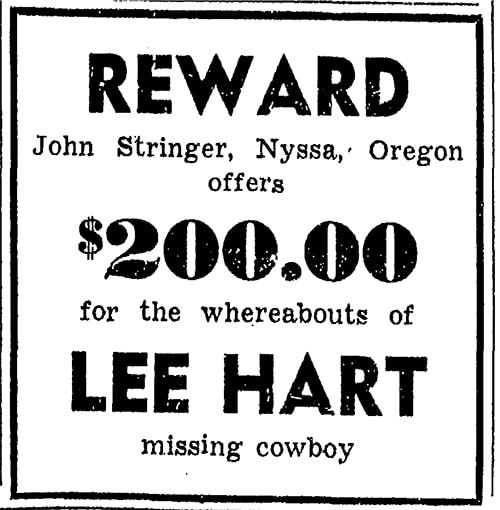

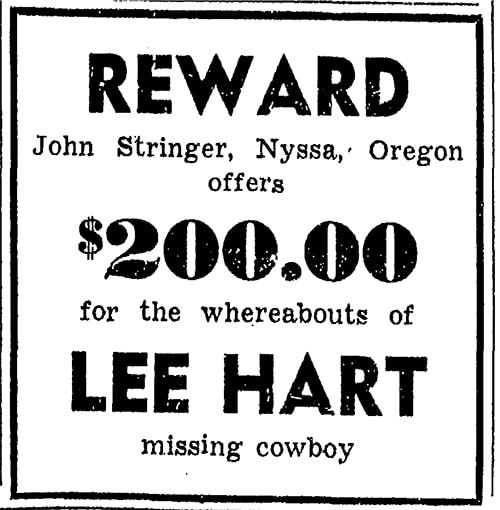

Red McCullough disappeared without a trace from the Sand Hollow area on October 28, 1945. McCullough was a tried and true cowboy, known for calf roping and cow cutting in the local rodeo scene. Nobody seemed to notice McCullough’s disappearance until his cattle partner and cabin-mate, Lee Hart, also vanished less than a month later. Once word spread about the two missing cowboys, the Washington County Sheriff opened an investigation into the matter.

The Sheriff recruited a posse of 20 men to search the surrounding area. They learned from a neighboring rancher that Hart was seen riding McCullough’s palomino stallion on November 18. The horse later returned to the neighbor’s ranch without a saddle or bridle. Two days later, on November 20, Hart briefly stopped at a friend’s house to eat a quick meal. There, Hart uttered three words that changed the Sheriff’s investigation from missing persons to homicide:

“Red is dead.”

A $200 reward was offered for information related to the whereabouts of McCullough, or Hart, and the Sheriff’s search intensified. Before long, the Sheriff theorized that the two men were both dead. He began probing reservoirs for signs of their bodies. On December 13, Hart was spotted nearly 160 miles south of his last known location in the Owyhee badlands. Five ranchers from that vicinity accurately described his appearance. By the next day, Hart was in law enforcement custody. He was found wandering in the desert between Murphy and Marsing.

Hart survived a total of 24 days on foot, without food or notable shelter. His only real protections against the elements were his trusty Levi overalls and a button up shirt. For sustenance, Hart ate rangeland grass by the handful. He once killed a porcupine with a club and cooked it on a small daytime fire, though he felt reluctant to ever light a fire at night. The Sheriff estimated that Hart walked a total of 500 winding miles. By the time he was found, Hart’s boots had given out, and his feet were badly frostbitten.

After eating his first real meal in over three weeks, Hart led the Sheriff and a small group of men to McCullough’s initial grave. It was less than a mile from the two cowboy’s shared cabin. He displayed disbelief that the body was missing. The coroner took a sample of dirt. When heated, it produced an odor which established that a body had been there for an unknown period of time. The next day Hart took the party to another shallow rock grave, located about five miles from the cabin. There, they found his body. It was evident that McCullough had died from a gunshot to the throat. Hart confessed that he was the person who fired the gun that killed his former partner, so he was formally arrested and charged with murder.

The question remained, why?

Hart claimed the killing was done in self defense. His attorney, future U.S. Senator Herman Welker of Payette, argued during the preliminary hearing that the charges should be dropped from murder to manslaughter. The Judge refused this request, and Hart’s jury trial was set for February. Hart was held without bail in the Washington County Jail for more than two months.

When February finally arrived, Hart pleaded his innocence. He entered the court wearing a brand new suit. True to his cowboy nature, Hart was quoted as saying, “I would feel a lot more comfortable if I was dressed in overalls, and had on my boots instead of these shoes.”

The prosecution sought a second degree murder charge, which carried a maximum penalty of life in prison. Their star witnesses were two high school students who were with McCullough earlier on the night of his death. The boys claimed McCullough became belligerently drunk at a local dance hall, so they escorted him back to his cabin. McCullough resisted, but Hart and the two boys convinced McCullough to stay. By the time the boys left, they claimed, Hart and McCullough had not started fighting.

Hart testified that McCullough wanted to sell his half of their cattle and leave their joint ranching operation. Hart suggested that McCullough sleep off his intoxication, and they could discuss the idea further the next day. This angered McCullough, Hart claimed, and McCullough “grabbed a rifle, and I grabbed a revolver and we started shooting. Red fell forward at my feet. I looked at him, saw he was dead, took a big drink of whisky and went to bed. The next morning I went out and fed the horses, and when I came back into the cabin and saw Red’s body lying there, I went loco crazy. I loaded his body on a horse, took it about a quarter of a mile away and buried it. Then I drank all the whisky I could pack.”

At that point, Hart said, he started hearing the voices of two imaginary men. These hallucinations convinced Hart to move McCullough’s body and eventually go on the run. Hart stated this was the first, and last, major disagreement he had ever had with McCullough. He finished his testimony by stating he “shot Red because he had a rifle and would have shot me.”

Hart’s defense revolved around this plea of insanity. Three doctors concurred that Hart was insane, either during or directly after the shooting. Two doctors disagreed, claiming Hart was fully “responsible except for the alcohol that was in him.” A total of seven other cowboys from Washington and Payette counties vouched that Hart was a peaceful and law abiding citizen, with generally good character and reputation.

At the conclusion of the trail, the Judge ordered the jury to return with one of four verdicts: guilty of murder in the second degree, guilty of voluntary manslaughter, guilty of involuntary manslaughter, or not guilty. The jury only deliberated for an hour before they returned with a “not guilty” acquittal verdict, and Hart and his new imaginary friends cheered.

Red McCullough disappeared without a trace from the Sand Hollow area on October 28, 1945. McCullough was a tried and true cowboy, known for calf roping and cow cutting in the local rodeo scene. Nobody seemed to notice McCullough’s disappearance until his cattle partner and cabin-mate, Lee Hart, also vanished less than a month later. Once word spread about the two missing cowboys, the Washington County Sheriff opened an investigation into the matter.

The Sheriff recruited a posse of 20 men to search the surrounding area. They learned from a neighboring rancher that Hart was seen riding McCullough’s palomino stallion on November 18. The horse later returned to the neighbor’s ranch without a saddle or bridle. Two days later, on November 20, Hart briefly stopped at a friend’s house to eat a quick meal. There, Hart uttered three words that changed the Sheriff’s investigation from missing persons to homicide:

“Red is dead.”

A $200 reward was offered for information related to the whereabouts of McCullough, or Hart, and the Sheriff’s search intensified. Before long, the Sheriff theorized that the two men were both dead. He began probing reservoirs for signs of their bodies. On December 13, Hart was spotted nearly 160 miles south of his last known location in the Owyhee badlands. Five ranchers from that vicinity accurately described his appearance. By the next day, Hart was in law enforcement custody. He was found wandering in the desert between Murphy and Marsing.

Hart survived a total of 24 days on foot, without food or notable shelter. His only real protections against the elements were his trusty Levi overalls and a button up shirt. For sustenance, Hart ate rangeland grass by the handful. He once killed a porcupine with a club and cooked it on a small daytime fire, though he felt reluctant to ever light a fire at night. The Sheriff estimated that Hart walked a total of 500 winding miles. By the time he was found, Hart’s boots had given out, and his feet were badly frostbitten.

After eating his first real meal in over three weeks, Hart led the Sheriff and a small group of men to McCullough’s initial grave. It was less than a mile from the two cowboy’s shared cabin. He displayed disbelief that the body was missing. The coroner took a sample of dirt. When heated, it produced an odor which established that a body had been there for an unknown period of time. The next day Hart took the party to another shallow rock grave, located about five miles from the cabin. There, they found his body. It was evident that McCullough had died from a gunshot to the throat. Hart confessed that he was the person who fired the gun that killed his former partner, so he was formally arrested and charged with murder.

The question remained, why?

Hart claimed the killing was done in self defense. His attorney, future U.S. Senator Herman Welker of Payette, argued during the preliminary hearing that the charges should be dropped from murder to manslaughter. The Judge refused this request, and Hart’s jury trial was set for February. Hart was held without bail in the Washington County Jail for more than two months.

When February finally arrived, Hart pleaded his innocence. He entered the court wearing a brand new suit. True to his cowboy nature, Hart was quoted as saying, “I would feel a lot more comfortable if I was dressed in overalls, and had on my boots instead of these shoes.”

The prosecution sought a second degree murder charge, which carried a maximum penalty of life in prison. Their star witnesses were two high school students who were with McCullough earlier on the night of his death. The boys claimed McCullough became belligerently drunk at a local dance hall, so they escorted him back to his cabin. McCullough resisted, but Hart and the two boys convinced McCullough to stay. By the time the boys left, they claimed, Hart and McCullough had not started fighting.

Hart testified that McCullough wanted to sell his half of their cattle and leave their joint ranching operation. Hart suggested that McCullough sleep off his intoxication, and they could discuss the idea further the next day. This angered McCullough, Hart claimed, and McCullough “grabbed a rifle, and I grabbed a revolver and we started shooting. Red fell forward at my feet. I looked at him, saw he was dead, took a big drink of whisky and went to bed. The next morning I went out and fed the horses, and when I came back into the cabin and saw Red’s body lying there, I went loco crazy. I loaded his body on a horse, took it about a quarter of a mile away and buried it. Then I drank all the whisky I could pack.”

At that point, Hart said, he started hearing the voices of two imaginary men. These hallucinations convinced Hart to move McCullough’s body and eventually go on the run. Hart stated this was the first, and last, major disagreement he had ever had with McCullough. He finished his testimony by stating he “shot Red because he had a rifle and would have shot me.”

Hart’s defense revolved around this plea of insanity. Three doctors concurred that Hart was insane, either during or directly after the shooting. Two doctors disagreed, claiming Hart was fully “responsible except for the alcohol that was in him.” A total of seven other cowboys from Washington and Payette counties vouched that Hart was a peaceful and law abiding citizen, with generally good character and reputation.

At the conclusion of the trail, the Judge ordered the jury to return with one of four verdicts: guilty of murder in the second degree, guilty of voluntary manslaughter, guilty of involuntary manslaughter, or not guilty. The jury only deliberated for an hour before they returned with a “not guilty” acquittal verdict, and Hart and his new imaginary friends cheered.

Published on May 03, 2021 04:00

May 2, 2021

A Gubernatorial Hunting Trip

Henry Clarence Baldridge was the 14th governor of the State of Idaho, serving from 1927 to 1931. He was a Republican who served in both the Idaho House and Senate as well as a couple of terms as lieutenant governor.

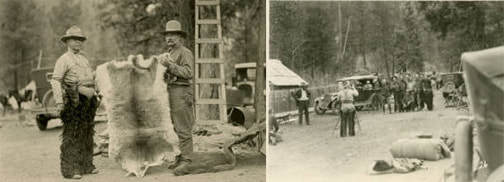

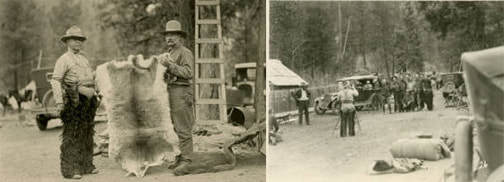

He went on a hunting trip in 1928 that wouldn’t even merit a footnote in Idaho history, except that we have pictures. As any TV news reporter will tell you, it didn’t happen unless someone took pictures.

The someone in this case was Ansgar Johnson, Sr. He was apparently with the governor and several other men on the hunting trip, and he came back with some great, in-focus shots. About a dozen of those pictures were donated to the Idaho State Historical Society and are part of their digital collection.

The photo on the left is of Gov. Baldrige in his furry chaps proudly standing next to a coyote skin. With him in the picture is a man identified as “Deadshot” Reed. In the photo on the right the governor is the one running a camera. It’s a “moving picture machine” according to the hand-written caption.

Do you have some cool old pictures taken in Idaho? The Idaho State Historical Society is one of several archives in the state where you could donate them. I’d be happy to help you share them here, if they show something that tells a good story.

He went on a hunting trip in 1928 that wouldn’t even merit a footnote in Idaho history, except that we have pictures. As any TV news reporter will tell you, it didn’t happen unless someone took pictures.

The someone in this case was Ansgar Johnson, Sr. He was apparently with the governor and several other men on the hunting trip, and he came back with some great, in-focus shots. About a dozen of those pictures were donated to the Idaho State Historical Society and are part of their digital collection.

The photo on the left is of Gov. Baldrige in his furry chaps proudly standing next to a coyote skin. With him in the picture is a man identified as “Deadshot” Reed. In the photo on the right the governor is the one running a camera. It’s a “moving picture machine” according to the hand-written caption.

Do you have some cool old pictures taken in Idaho? The Idaho State Historical Society is one of several archives in the state where you could donate them. I’d be happy to help you share them here, if they show something that tells a good story.

Published on May 02, 2021 04:00

May 1, 2021

Andy's Idaho Map

Okay, I’m vying for the least important Speaking of Idaho post of all time with this one. Even so, I may quell an argument that seems to bubble between Andy Griffith show fans.

Mayberry is not in Idaho. That won’t settle the argument, though. Mayberry is also not in North Carolina, the state in which the fictional town was said to be. Mount Airy, Andy Griffith’s boyhood home, embraces its role as “Mayberry,” and has as good a claim as any town.

The argument is about a map that hung on the wall in Andy’s office. Legend has it that the map, perhaps meant to be a county or city map, was actually a map of Idaho hung upside down. True. And false. A map of Idaho did hang upside down in the office for at least one, and possibly several episodes, but not for the whole series. Maps seemed to be a joke with the sets people. Nevada was also hung from its feet, North Carolina was displayed, and most often the map was of Cincinnati.

The old publicity photo below clearly shows your favorite state map flying in distress mode on the wall over Don Knotts’ shoulder.

The shape of Idaho is just another thing to love about the state. Pity the poor folks from Colorado for their lack of recognizable state lapel pins.

Mayberry is not in Idaho. That won’t settle the argument, though. Mayberry is also not in North Carolina, the state in which the fictional town was said to be. Mount Airy, Andy Griffith’s boyhood home, embraces its role as “Mayberry,” and has as good a claim as any town.

The argument is about a map that hung on the wall in Andy’s office. Legend has it that the map, perhaps meant to be a county or city map, was actually a map of Idaho hung upside down. True. And false. A map of Idaho did hang upside down in the office for at least one, and possibly several episodes, but not for the whole series. Maps seemed to be a joke with the sets people. Nevada was also hung from its feet, North Carolina was displayed, and most often the map was of Cincinnati.

The old publicity photo below clearly shows your favorite state map flying in distress mode on the wall over Don Knotts’ shoulder.

The shape of Idaho is just another thing to love about the state. Pity the poor folks from Colorado for their lack of recognizable state lapel pins.

Published on May 01, 2021 04:00

April 30, 2021

Pop Quiz!

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture. If you missed that story, click the letter for a link.

1). What was the fate of one of the drill halls at Farragut Naval Training Station?

A. It was moved to Boise to become a Costco

B. It became an Amazon warehouse

C. It was turned into a hockey stadium in Denver

D. It was turned into a hockey stadium in Calgary

E. It burned down near the end of WWII

2). What did the Kelton Road lead to?

A. The train station nearest to Southern Idaho

B. Bannock, Montana

C. The California gold fields

D. Ontario, Oregon

E. Sun Valley

3). What does Murphy, Idaho have that Firth, Idaho doesn’t?

A. A State Street

B. Dirt streets

C. A community sewage system

D. An airport

E. A parking meter

4). Why is Aviator Cave named that?

A. Because of a nearby plane crash

B. It was discovered by a pilot flying over it

C. It is located near where an atomic plane was being developed

D. There is a directional arrow for pilots nearby

E. Aviator was the last name of the man who discovered it.

5) What was once proposed to be built on top of Table Rock in Boise?

A. Hotel

B. Theme Park

C. Railroad Roundhouse

D. Airport

E. Post Office

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

1, C

2, A

3, E

4, B

5, A

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). What was the fate of one of the drill halls at Farragut Naval Training Station?

A. It was moved to Boise to become a Costco

B. It became an Amazon warehouse

C. It was turned into a hockey stadium in Denver

D. It was turned into a hockey stadium in Calgary

E. It burned down near the end of WWII

2). What did the Kelton Road lead to?

A. The train station nearest to Southern Idaho

B. Bannock, Montana

C. The California gold fields

D. Ontario, Oregon

E. Sun Valley

3). What does Murphy, Idaho have that Firth, Idaho doesn’t?

A. A State Street

B. Dirt streets

C. A community sewage system

D. An airport

E. A parking meter

4). Why is Aviator Cave named that?

A. Because of a nearby plane crash

B. It was discovered by a pilot flying over it

C. It is located near where an atomic plane was being developed

D. There is a directional arrow for pilots nearby

E. Aviator was the last name of the man who discovered it.

5) What was once proposed to be built on top of Table Rock in Boise?

A. Hotel

B. Theme Park

C. Railroad Roundhouse

D. Airport

E. Post Office

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)1, C

2, A

3, E

4, B

5, A

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on April 30, 2021 04:00