Rick Just's Blog, page 129

April 18, 2021

Count Those Islands

Three Island Crossing was a terror for Oregon Trail pioneers. The ford at the Snake River near the present-day town of Glenns Ferry was one of the most feared parts of the journey. The river, some 200 yards wide, was deceptively placid looking. The current was relentless. About half those traveling the Oregon Trail risked a crossing there. Half chose to stay on the south side of the river where the trail was worse and longer but the chance of losing everything to the river did not loom.

Narcissa Whitman, one of four missionaries on their way to historic and tragic roles in history, wrote this about the crossing in August of 1836: "We have come fifteen miles and have had the worst route in all the journey for the cart. We might have had a better one but for being misled by some of the company who started out before the leaders.

“It was two o'clock before we came into camp. They were preparing to cross Snake River. The river is divided by two islands into three branches, and is fordable. The packs are placed upon the tops of the highest horses and in this way we crossed without wetting. Two of the tallest horses were selected to carry Mrs. Spalding and myself over. Mr. McLeod gave me his and rode mine. The last branch we rode as much as half a mile in crossing and against the current too, which made it hard for the horses, the water being up to their sides. Husband had considerable difficulty crossing the cart. Both cart and mules were turned upside down in the river and entangled in the harness. The mules would have been drowned but for a desperate struggle to get them ashore. Then after putting two of the strongest horses before the cart, and two men swimming behind to steady it, they succeeded in getting it across.

“I once thought that crossing streams would be the most dreaded part of the journey. I can now cross the most difficult stream without the least fear. There is one manner of crossing which husband has tried but I have not, neither do I wish to. Take an elk skin and stretch it over you, spreading yourself out as much as possible, then let the Indian women carefully put you on the water and with a cord in the mouth they will swim and draw you over. Edward, how do you think you would like to travel in this way?"

John C. Fremont told of another crossing in 1842: “About two o’clock we had arrived at the ford where the road crosses to the right bank of the Snake River. An Indian was hired to conduct us through the ford, which proved impracticable for us, the water sweeping away the howitzer and nearly drowning the mules, which we were able to extricate by cutting them out of the harness. The river is expanded into a little bay, in which there are two islands, across which is the road of the ford; and the emigrants had passed by placing two of their heavy wagons abreast of each other, so as to oppose a considerable mass against the body of water.”

Fremont mentions just two islands, not three. Like other travelers he probably ignored the third island, using just two to make his crossing. The interpretive center at Three Island Crossing State Park tells the story.

One thing not related to the famous crossing at all frustrates rangers there. In recent decades the name Three Island Crossing is often confused with Three Mile Island in the minds of those who remember the nuclear accident that happened a continent away.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

Narcissa Whitman, one of four missionaries on their way to historic and tragic roles in history, wrote this about the crossing in August of 1836: "We have come fifteen miles and have had the worst route in all the journey for the cart. We might have had a better one but for being misled by some of the company who started out before the leaders.

“It was two o'clock before we came into camp. They were preparing to cross Snake River. The river is divided by two islands into three branches, and is fordable. The packs are placed upon the tops of the highest horses and in this way we crossed without wetting. Two of the tallest horses were selected to carry Mrs. Spalding and myself over. Mr. McLeod gave me his and rode mine. The last branch we rode as much as half a mile in crossing and against the current too, which made it hard for the horses, the water being up to their sides. Husband had considerable difficulty crossing the cart. Both cart and mules were turned upside down in the river and entangled in the harness. The mules would have been drowned but for a desperate struggle to get them ashore. Then after putting two of the strongest horses before the cart, and two men swimming behind to steady it, they succeeded in getting it across.

“I once thought that crossing streams would be the most dreaded part of the journey. I can now cross the most difficult stream without the least fear. There is one manner of crossing which husband has tried but I have not, neither do I wish to. Take an elk skin and stretch it over you, spreading yourself out as much as possible, then let the Indian women carefully put you on the water and with a cord in the mouth they will swim and draw you over. Edward, how do you think you would like to travel in this way?"

John C. Fremont told of another crossing in 1842: “About two o’clock we had arrived at the ford where the road crosses to the right bank of the Snake River. An Indian was hired to conduct us through the ford, which proved impracticable for us, the water sweeping away the howitzer and nearly drowning the mules, which we were able to extricate by cutting them out of the harness. The river is expanded into a little bay, in which there are two islands, across which is the road of the ford; and the emigrants had passed by placing two of their heavy wagons abreast of each other, so as to oppose a considerable mass against the body of water.”

Fremont mentions just two islands, not three. Like other travelers he probably ignored the third island, using just two to make his crossing. The interpretive center at Three Island Crossing State Park tells the story.

One thing not related to the famous crossing at all frustrates rangers there. In recent decades the name Three Island Crossing is often confused with Three Mile Island in the minds of those who remember the nuclear accident that happened a continent away.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

Published on April 18, 2021 04:00

April 17, 2021

How Cold Was It?

This winter of 2016-2017 was one for the record books in many parts of the state. Tales will be told about it, perhaps not as creative as this one, taken from the Eagle Rock Register, January 28, 1888 in describing the situation in Malad.

“This has been the coldest spell Maladians ever experienced. Thermometers less than twelve feet long are absolutely worthless as indicators of the temperature. The water in wells 14 feet deep has been frozen solid. Coal oil is sold by the yard, beer by the foot, and the hottest kind of rot-gut whiskey by the stick. It is said that in St. John a kerosene lamp was frozen while burning, and that not only the lamp was frozen and the oil was solidified, but the flame was frozen stiff and was just as natural as a petrified pig. . . Should anybody doubt this statement, we respectfully ask them to come in before spring and examine the record. We have the very words in which this statement was made to us, in solid chunks of ice.”

But really, how cold was it?

The record temperature ever recorded in Idaho was 60 below zero at Island Park Dam on January 18, 1943. That’s according to that unfailingly accurate source, the internet. The same source lists a temp of 118 on July 28, 1934 as Idaho’s record high. That was recorded in Orofino.

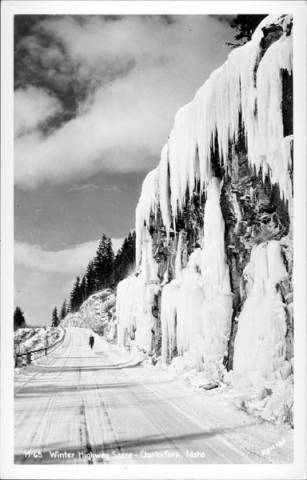

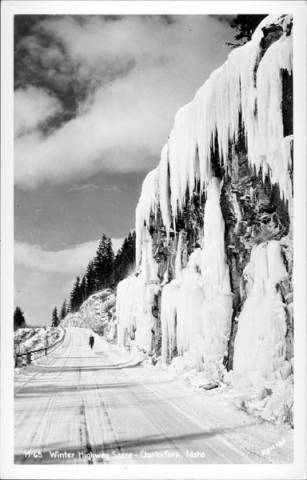

Wherever you’re enjoying Idaho’s summer today, cool off for a moment with this winter scene of a highway near Clarks Fork, probably in the 1940s, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection.

Wherever you’re enjoying Idaho’s summer today, cool off for a moment with this winter scene of a highway near Clarks Fork, probably in the 1940s, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection.

“This has been the coldest spell Maladians ever experienced. Thermometers less than twelve feet long are absolutely worthless as indicators of the temperature. The water in wells 14 feet deep has been frozen solid. Coal oil is sold by the yard, beer by the foot, and the hottest kind of rot-gut whiskey by the stick. It is said that in St. John a kerosene lamp was frozen while burning, and that not only the lamp was frozen and the oil was solidified, but the flame was frozen stiff and was just as natural as a petrified pig. . . Should anybody doubt this statement, we respectfully ask them to come in before spring and examine the record. We have the very words in which this statement was made to us, in solid chunks of ice.”

But really, how cold was it?

The record temperature ever recorded in Idaho was 60 below zero at Island Park Dam on January 18, 1943. That’s according to that unfailingly accurate source, the internet. The same source lists a temp of 118 on July 28, 1934 as Idaho’s record high. That was recorded in Orofino.

Wherever you’re enjoying Idaho’s summer today, cool off for a moment with this winter scene of a highway near Clarks Fork, probably in the 1940s, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection.

Wherever you’re enjoying Idaho’s summer today, cool off for a moment with this winter scene of a highway near Clarks Fork, probably in the 1940s, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection.

Published on April 17, 2021 04:00

April 16, 2021

Fire at the Forbidden Palace

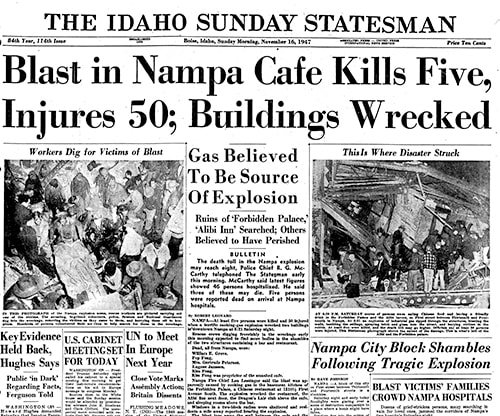

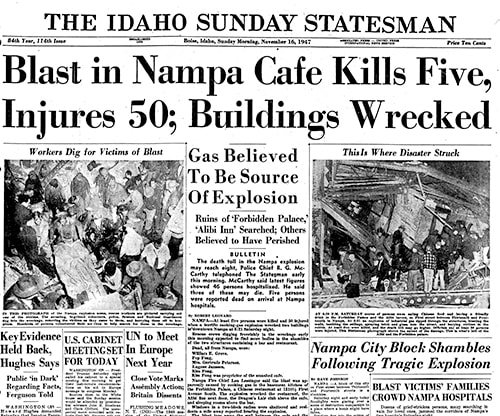

On Saturday night, November 16, 1947, a customer walked into the Forbidden Palace Chinese restaurant in Nampa, sat down at the counter and said, “I smell gas.”

The waitress replied, “I do, too.”

As if the conversation set it off, an enormous blast rocked the restaurant and the Alibi tavern next door. The floor dropped from beneath their feet and the ceiling came crashing down on top of them. For a moment, as the dust settled, there was silence. Then the screams began.

Fifty people were injured in the explosion and building collapse, six were killed.

The explosion occurred as a service truck was filling the butane gas tank the restaurant used for cooking.

Within a couple of weeks Knu Gas and Appliance of Boise and Nampa was running ads notifying customers that they had nothing to do with the explosion and extolling the safety of PROPANE gas and gas appliances.

By the end of the year, the “Superlatives of 47” feature in the Idaho Statesman listed the Forbidden Palace explosion the greatest Boise Valley disaster of the year.

Numerous lawsuits against the City of Nampa and the company that installed the butane tank were filed. The Idaho Supreme Court ultimately absolved the city of responsibility.

The blast increased calls for establishing a state fire marshal to formulate rules on LPG. Legislation was introduced and defeated in 1948. It wasn’t until 1982 that the first state fire marshal was named. The office is a division of the Idaho Department of Insurance. The director of that department selects the fire marshal with approval of the governor.

The waitress replied, “I do, too.”

As if the conversation set it off, an enormous blast rocked the restaurant and the Alibi tavern next door. The floor dropped from beneath their feet and the ceiling came crashing down on top of them. For a moment, as the dust settled, there was silence. Then the screams began.

Fifty people were injured in the explosion and building collapse, six were killed.

The explosion occurred as a service truck was filling the butane gas tank the restaurant used for cooking.

Within a couple of weeks Knu Gas and Appliance of Boise and Nampa was running ads notifying customers that they had nothing to do with the explosion and extolling the safety of PROPANE gas and gas appliances.

By the end of the year, the “Superlatives of 47” feature in the Idaho Statesman listed the Forbidden Palace explosion the greatest Boise Valley disaster of the year.

Numerous lawsuits against the City of Nampa and the company that installed the butane tank were filed. The Idaho Supreme Court ultimately absolved the city of responsibility.

The blast increased calls for establishing a state fire marshal to formulate rules on LPG. Legislation was introduced and defeated in 1948. It wasn’t until 1982 that the first state fire marshal was named. The office is a division of the Idaho Department of Insurance. The director of that department selects the fire marshal with approval of the governor.

Published on April 16, 2021 04:00

April 15, 2021

"Dad" Clay Foils a Kidnapping

What are the odds of being a participant in two kidnappings? J.C. “Dad” Clay of Idaho Falls could claim that. He had different roles in each adventure, first as the driver of a carload of law enforcement officers that captured a kidnapper, and second as the kidnappee and captor of the kidnappers.

I’ll be writing multiple stories about Dad Clay, so I won’t attempt to describe him in detail. Suffice to say, for this story, that he owned the first automobile garage in the state. He started his Idaho Falls garage in 1909. By 1914, he was selling cars there and had published Idaho’s first road log to help travelers get around the state. His first brush with kidnapping came in 1915.

That’s when the kidnapper of E.A. Empey was apprehended. The Idaho Statesman, on July 28, 1915 described it like this: “A party was at once organized at the Sheriff’s office, consisting of deputies and reporters, who in a big car driven by J.C. Clay, an old resident of the community, thoroughly familiar with every road and trail in the entire country and a fast driver, were soon on the way to meet the bandit and his captors.” Clay played a small role in that incident, which you can read all about through the link above. His role was decidedly larger during the next kidnapping the following year.

According to an oral history told to his family, the kidnapping came about because he ran a taxi service next to his garage. A couple of tough looking young men came by looking for a ride into the country. An employee was set to take them, but Clay didn’t think it was safe for the boy to head out with those customers, so he decided to take them himself.

One of the men hopped into the seat beside the driver and the other got in back. They had driven about 20 miles when the man in the back seat slipped a piece of pipe out from under his coat where he had been hiding it and wacked Dad Clay over the head, knocking him out. The pair frisked Clay, finding a derringer in his side pocket and his wallet. They tied his hands and feet together and threw the unconscious man in the back.

After a few minutes and miles of travel, Clay came to. He could hear the toughs in front of the car laughing about hijacking his taxi. He came to understand that it was their plan to dump him in a ditch somewhere after killing him. Since this didn’t mesh well with his own plans for the future, Dad Clay worked his hands and feet free from the ropes while his kidnappers weren’t paying any attention. In the process, he discovered that the pipe he’d been beaned with was down there on the floor with him.

Clay rose up and returned the favor, clubbing each man hard on the head with the pipe. He tied both of them up, doing a better job of it than they had, and piled them in the back seat. He had found his derringer and couple of pistols the men had been carrying. His passengers secured, he turned around and headed back to town.

Dad Clay delivered the carjackers to the sheriff’s office, where he found out they’d escaped from a nearby correctional facility.

There is a newspaper account of the story which differs a bit. In that version one of the kidnappers escaped for a short time before being apprehended by authorities, but the essential account of Clay’s bonk on the head and turning the tables on the men to bring them to justice seems essentially true. A portrait of "Dad" Clay.

A portrait of "Dad" Clay.

I’ll be writing multiple stories about Dad Clay, so I won’t attempt to describe him in detail. Suffice to say, for this story, that he owned the first automobile garage in the state. He started his Idaho Falls garage in 1909. By 1914, he was selling cars there and had published Idaho’s first road log to help travelers get around the state. His first brush with kidnapping came in 1915.

That’s when the kidnapper of E.A. Empey was apprehended. The Idaho Statesman, on July 28, 1915 described it like this: “A party was at once organized at the Sheriff’s office, consisting of deputies and reporters, who in a big car driven by J.C. Clay, an old resident of the community, thoroughly familiar with every road and trail in the entire country and a fast driver, were soon on the way to meet the bandit and his captors.” Clay played a small role in that incident, which you can read all about through the link above. His role was decidedly larger during the next kidnapping the following year.

According to an oral history told to his family, the kidnapping came about because he ran a taxi service next to his garage. A couple of tough looking young men came by looking for a ride into the country. An employee was set to take them, but Clay didn’t think it was safe for the boy to head out with those customers, so he decided to take them himself.

One of the men hopped into the seat beside the driver and the other got in back. They had driven about 20 miles when the man in the back seat slipped a piece of pipe out from under his coat where he had been hiding it and wacked Dad Clay over the head, knocking him out. The pair frisked Clay, finding a derringer in his side pocket and his wallet. They tied his hands and feet together and threw the unconscious man in the back.

After a few minutes and miles of travel, Clay came to. He could hear the toughs in front of the car laughing about hijacking his taxi. He came to understand that it was their plan to dump him in a ditch somewhere after killing him. Since this didn’t mesh well with his own plans for the future, Dad Clay worked his hands and feet free from the ropes while his kidnappers weren’t paying any attention. In the process, he discovered that the pipe he’d been beaned with was down there on the floor with him.

Clay rose up and returned the favor, clubbing each man hard on the head with the pipe. He tied both of them up, doing a better job of it than they had, and piled them in the back seat. He had found his derringer and couple of pistols the men had been carrying. His passengers secured, he turned around and headed back to town.

Dad Clay delivered the carjackers to the sheriff’s office, where he found out they’d escaped from a nearby correctional facility.

There is a newspaper account of the story which differs a bit. In that version one of the kidnappers escaped for a short time before being apprehended by authorities, but the essential account of Clay’s bonk on the head and turning the tables on the men to bring them to justice seems essentially true.

A portrait of "Dad" Clay.

A portrait of "Dad" Clay.

Published on April 15, 2021 04:00

April 14, 2021

"Dad" Clay

John Colby Clay was born in Minnesota in 1854. He came West when he was 15. He kicked around the Dakotas, Wyoming, and Oregon for a number of years punching cattle, ranching, and driving a freight wagon. He ended up settling in Idaho in 1892.

In 1908 (or 1909, or 1910… accounts differ) J.C. Clay had an epiphany. He was fascinated with automobiles and decided to bet his future on them. Already in his 50s, it wouldn’t seem like a time to start a new venture, but he did. No one knows exactly when people started calling him “Dad” Clay, but he solidified that moniker by building Dad Clay’s Garage. It was the first automobile service center in the state. It grew to include car dealerships for a time and a taxi company. Proving that he was a man way ahead of his time, he built an underground parking area beneath the garage.

Dad Clay was elected the “good roads” chairman of the Idaho State Automobile Association. He took that job seriously. He began marking roads, much as Charlie Sampson did in the Boise area. Sampson started out painting advertising signs about his music business. Clay erected hundreds of black and orange signs all over Southeastern Idaho giving the mileage to his Idaho Falls garage. In 1914, Dad Clay published the first guide to Idaho’s 5,500 miles of roads. It was a big hit with auto enthusiasts, though at least one resident of Pocatello accused him of discriminating against the Gate City by routing travelers around it.

Running Idaho’s first garage wasn’t enough to keep Dad Clay busy, though. He was involved in real estate development, a coal mine, Teton Light and Power, a security firm, and managed the Idaho Falls baseball team, the Sunnylanders. Clay was also a well-known golfer locally. He once famously bet his false teeth on the outcome of a match.

Dad Clay’s love for automobiles got him in trouble at least a couple of times. He was carjacked once, turning the tables on the bad guys. That story runs tomorrow.

He was well known for driving full speed wherever he went. That was to his detriment in April of 1914 when he caused a three-car collision on the outskirts of Firth. A Studebaker was dawdling along in front of Dad Clay, who was driving his Hupmobile. A Ford was coming the other direction, but Clay was sure he could make it, so he swung around the Studebaker. What caused the wreck wasn’t exactly clear, but Clay hit the Studebaker, then the Ford, throwing the eight passengers in the three cars all over the road. Clay received a broken arm and everyone else had cuts and bruises. A judge determined that the accident was Dad Clay’s fault. The occupants of the other cars vowed to sue him. The results of that lawsuit, if one did come about, are unknown.

At age 87, Clay sold his garage to a nephew. He passed away the next year on a trip to California at age 88. “Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”  Clay, standing in front of the car, in Dad Clay’s Garage.

Clay, standing in front of the car, in Dad Clay’s Garage.

In 1908 (or 1909, or 1910… accounts differ) J.C. Clay had an epiphany. He was fascinated with automobiles and decided to bet his future on them. Already in his 50s, it wouldn’t seem like a time to start a new venture, but he did. No one knows exactly when people started calling him “Dad” Clay, but he solidified that moniker by building Dad Clay’s Garage. It was the first automobile service center in the state. It grew to include car dealerships for a time and a taxi company. Proving that he was a man way ahead of his time, he built an underground parking area beneath the garage.

Dad Clay was elected the “good roads” chairman of the Idaho State Automobile Association. He took that job seriously. He began marking roads, much as Charlie Sampson did in the Boise area. Sampson started out painting advertising signs about his music business. Clay erected hundreds of black and orange signs all over Southeastern Idaho giving the mileage to his Idaho Falls garage. In 1914, Dad Clay published the first guide to Idaho’s 5,500 miles of roads. It was a big hit with auto enthusiasts, though at least one resident of Pocatello accused him of discriminating against the Gate City by routing travelers around it.

Running Idaho’s first garage wasn’t enough to keep Dad Clay busy, though. He was involved in real estate development, a coal mine, Teton Light and Power, a security firm, and managed the Idaho Falls baseball team, the Sunnylanders. Clay was also a well-known golfer locally. He once famously bet his false teeth on the outcome of a match.

Dad Clay’s love for automobiles got him in trouble at least a couple of times. He was carjacked once, turning the tables on the bad guys. That story runs tomorrow.

He was well known for driving full speed wherever he went. That was to his detriment in April of 1914 when he caused a three-car collision on the outskirts of Firth. A Studebaker was dawdling along in front of Dad Clay, who was driving his Hupmobile. A Ford was coming the other direction, but Clay was sure he could make it, so he swung around the Studebaker. What caused the wreck wasn’t exactly clear, but Clay hit the Studebaker, then the Ford, throwing the eight passengers in the three cars all over the road. Clay received a broken arm and everyone else had cuts and bruises. A judge determined that the accident was Dad Clay’s fault. The occupants of the other cars vowed to sue him. The results of that lawsuit, if one did come about, are unknown.

At age 87, Clay sold his garage to a nephew. He passed away the next year on a trip to California at age 88.

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”

“Dad” Clay at the wheel of his Hupmobile, equipped with Silvertown Tires by Goodrich. This image comes from Goodrich, the monthly magazine published by the B.F. Goodrich Rubber Company. It appeared in the April 1918 edition, noting that “Dad Clay was one of the early pioneers in Idaho and among the first men in the state to recognize that the motor car would supersede the broncho as an agent of transportation.”  Clay, standing in front of the car, in Dad Clay’s Garage.

Clay, standing in front of the car, in Dad Clay’s Garage.

Published on April 14, 2021 04:00

April 13, 2021

Foothills Development in Boise

For the past 30 years or so there has been a tension in Boise between those who love a view, and those who love a view. People wanted to build houses along the Boise Front for the view it afforded of the city and beyond. Other Boise residents objected to houses popping up on the foothills and spoiling THEIR view of the Front. It wasn’t just the view that had those residents concerned. They thought the Boise Front had intrinsic values of its own, from wildlife habitat to recreation opportunities. There have been victories on both sides over the years, but the consensus now seems to be in favor of limiting growth in the foothills.

That’s why an article in the March-April 1953 edition of Scenic Idaho magazine caught my attention. Titled “Boise Takes to the Heights,” it led off with these paragraphs:

“The Boise Chamber of Commerce has a motto: Building a Better Boise—But if the present trek of its population continues to elevated home sites, this might well be changed to: “Building a Higher Boise.”

Nor are the regular residents the only ones lifting their eyes to the hills… Newcomers from California’s crowded population centers, from the Midwest and the East have found the city’s clime to their liking… Many of these seek “elbowroom” and gratify their need for it by constructing homes on hill and bench that are not altogether California or western ranch-house or modernistic—but which architects say may become the forerunner of a strictly “Idaho Home.”

Imagine, people moving to Idaho from California, of all places!

Among the realtors hawking homes in J.R. Simplot’s Boise Heights development (excellent homesites from $1,000) was Day Realty, run by Ernie Day. Day built his own home there. Today, with sensibilities about the foothills turned about 180 degrees from those of 1953, one might be tempted to grumble about entrepreneurs such as Ernie Day building homes where homes, perhaps, should never have been built. But I think Ernie can be given a bit of a pass on this one. He became an outspoken champion of Idaho’s special places and would play a key role in saving the Whiteclouds from mining in the early 70s.

The article ended with a sentence that would get many Boisean’s blood boiling today:

“Thus, Boise takes to the heights, and for a city continuing to increase in population, the surrounding hills and benches have provided a natural setting, and an outlet of new beauty without loss in utility.”

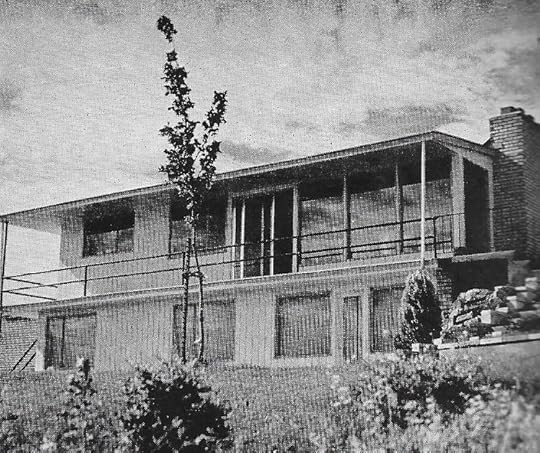

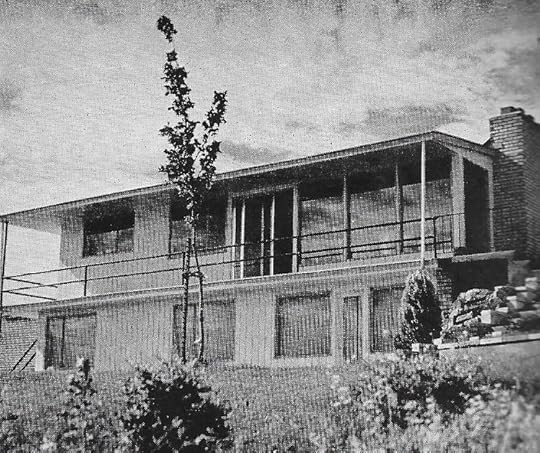

The photo is from the magazine article, which noted large windows set to provide a panoramic view to the southwest.

That’s why an article in the March-April 1953 edition of Scenic Idaho magazine caught my attention. Titled “Boise Takes to the Heights,” it led off with these paragraphs:

“The Boise Chamber of Commerce has a motto: Building a Better Boise—But if the present trek of its population continues to elevated home sites, this might well be changed to: “Building a Higher Boise.”

Nor are the regular residents the only ones lifting their eyes to the hills… Newcomers from California’s crowded population centers, from the Midwest and the East have found the city’s clime to their liking… Many of these seek “elbowroom” and gratify their need for it by constructing homes on hill and bench that are not altogether California or western ranch-house or modernistic—but which architects say may become the forerunner of a strictly “Idaho Home.”

Imagine, people moving to Idaho from California, of all places!

Among the realtors hawking homes in J.R. Simplot’s Boise Heights development (excellent homesites from $1,000) was Day Realty, run by Ernie Day. Day built his own home there. Today, with sensibilities about the foothills turned about 180 degrees from those of 1953, one might be tempted to grumble about entrepreneurs such as Ernie Day building homes where homes, perhaps, should never have been built. But I think Ernie can be given a bit of a pass on this one. He became an outspoken champion of Idaho’s special places and would play a key role in saving the Whiteclouds from mining in the early 70s.

The article ended with a sentence that would get many Boisean’s blood boiling today:

“Thus, Boise takes to the heights, and for a city continuing to increase in population, the surrounding hills and benches have provided a natural setting, and an outlet of new beauty without loss in utility.”

The photo is from the magazine article, which noted large windows set to provide a panoramic view to the southwest.

Published on April 13, 2021 04:00

April 12, 2021

Kelton

Idaho history doesn’t always neatly fit within the state’s borders. Such is the case with Kelton, Utah.

Kelton, named after a local stockman, became a section station on the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. It was located north of the Great Salt Lake and southwest of present-day Snowville, Utah.

In 1863 John Hailey established a stage route between Salt Lake City and Boise. Kelton was one of the stations along the way. Six years later, when Kelton became the best point to connect to the railroad from Boise, the route became known as the Kelton Road.

You can get to the ghost town of Kelton today in less than four hours. In the 1860s it took a little longer. A stage could make between the two towns in 42 hours. If you were hauling freight, it could take 18 days. Here’s a list of the stage stops along the Kelton Road, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s Reference Series.

Black's Creek (15 miles from Boise)

Baylock (13 miles)

Canyon Creek (12 miles)

Rattlesnake (8 miles)

Cold Springs (12 miles)

King Hill (10 miles)

Clover Creek (11 miles)

Malad (11 miles)

Sand Springs (11 miles)

Snake River at Clark's Ferry (10 miles)

Desert (12 miles)

Rock Creek (13 miles)

Mountain Meadows (14 miles)

Oakley Meadows (12 miles)

Goose Creek Summit (11 miles)

City of Rocks (11 miles)

Raft River (12 miles)

Clear Creek (12 miles)

Crystal Springs (10 miles)

Kelton (12 miles)

Kelton, Utah’s unique position as Idaho’s railway station ended in 1883 when the Oregon Shortline came through Southern Idaho. The end was sudden. By 1884 a traveler on the old route noticed that “grass now grows over the defunct overland Kelton stage road where the weary traveler once traveled in clouds of dust. . ."

Kelton survived until 1942 when the Southern Pacific pulled out the rails that had made the town boom.

You can see ruts through the lava and an old bridge abutment on the Kelton Road at Malad Gorge State Park. Go to the park unit north of the freeway.

You can also soak up some Kelton Road history at Stricker Ranch, operated by the Idaho State Historical Society. Rock Creek Station was there.

The Kelton Road crossed the Wood River just below this point. You can still see the ramp for the long-gone bridge just downstream from this point. This unit of Malad Gorge State Park is north of the freeway. It is a little known treasure where you can see some amazing water carved lava as well as the worn track of the Kelton Road through the rocks.

The Kelton Road crossed the Wood River just below this point. You can still see the ramp for the long-gone bridge just downstream from this point. This unit of Malad Gorge State Park is north of the freeway. It is a little known treasure where you can see some amazing water carved lava as well as the worn track of the Kelton Road through the rocks.

Kelton, named after a local stockman, became a section station on the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. It was located north of the Great Salt Lake and southwest of present-day Snowville, Utah.

In 1863 John Hailey established a stage route between Salt Lake City and Boise. Kelton was one of the stations along the way. Six years later, when Kelton became the best point to connect to the railroad from Boise, the route became known as the Kelton Road.

You can get to the ghost town of Kelton today in less than four hours. In the 1860s it took a little longer. A stage could make between the two towns in 42 hours. If you were hauling freight, it could take 18 days. Here’s a list of the stage stops along the Kelton Road, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s Reference Series.

Black's Creek (15 miles from Boise)

Baylock (13 miles)

Canyon Creek (12 miles)

Rattlesnake (8 miles)

Cold Springs (12 miles)

King Hill (10 miles)

Clover Creek (11 miles)

Malad (11 miles)

Sand Springs (11 miles)

Snake River at Clark's Ferry (10 miles)

Desert (12 miles)

Rock Creek (13 miles)

Mountain Meadows (14 miles)

Oakley Meadows (12 miles)

Goose Creek Summit (11 miles)

City of Rocks (11 miles)

Raft River (12 miles)

Clear Creek (12 miles)

Crystal Springs (10 miles)

Kelton (12 miles)

Kelton, Utah’s unique position as Idaho’s railway station ended in 1883 when the Oregon Shortline came through Southern Idaho. The end was sudden. By 1884 a traveler on the old route noticed that “grass now grows over the defunct overland Kelton stage road where the weary traveler once traveled in clouds of dust. . ."

Kelton survived until 1942 when the Southern Pacific pulled out the rails that had made the town boom.

You can see ruts through the lava and an old bridge abutment on the Kelton Road at Malad Gorge State Park. Go to the park unit north of the freeway.

You can also soak up some Kelton Road history at Stricker Ranch, operated by the Idaho State Historical Society. Rock Creek Station was there.

The Kelton Road crossed the Wood River just below this point. You can still see the ramp for the long-gone bridge just downstream from this point. This unit of Malad Gorge State Park is north of the freeway. It is a little known treasure where you can see some amazing water carved lava as well as the worn track of the Kelton Road through the rocks.

The Kelton Road crossed the Wood River just below this point. You can still see the ramp for the long-gone bridge just downstream from this point. This unit of Malad Gorge State Park is north of the freeway. It is a little known treasure where you can see some amazing water carved lava as well as the worn track of the Kelton Road through the rocks.

Published on April 12, 2021 04:00

April 11, 2021

First Cars

Automobiles were a wonder when the first came out, sure to attract a crowd in any Idaho city, including Idaho City, where according to the Idaho City World, in July of 1904, “Mr. and Mrs. F.L. Sweaney surprised the natives yesterday afternoon without previous warning, in an automobile.” It was the first horseless carriage ever seen there.

That was nothing, though, because the Hailey News-Miner reported the first automobile to be seen on the streets in Hailey more than a year earlier, in June 1903. The paper noted that “A Hailey lad was on the race track when the auto passed. On first seeing it approach he shouted out: ‘Here comes a runaway with the tongue out!’”

By 1905, autos were common enough in the capital city that the Idaho Statesman noted the first one to be seized in a legal process.

In 1907, that same paper told about the first car to make a long, arduous journey from Boise to Horseshoe Bend. It took the car, a White Steamer, an hour and a half to get to Pearl on the way to Horsehoe Bend. On the way back they did the trip from Pearl in an hour and 20 minutes, “the car behaving so well that at no time were they compelled to stop or do anything to the machine.”

That same year the first automobile reached Silver City, giving citizens their first look at a “Buzz Wagon.” The Statesman reported that “Many young and older people here had never seen an automobile before, and there have been many visitors at Gardener’s barn to look it over.”

By 1909 cars were old hat. The Statesman ran a humorous piece about the inevitability of car ownership. “It will be recalled that the first automobile was purchased by a Boise ice man. That is in harmony with fixed conditions. Luxuries are always secured first by the wealthiest classes. Then a plumber broke in. He was logically next. The coal man was a trifle late, though third, but he purchased a machine that eclipsed all others in point of style and speed. The doctors began to purchase, followed by the undertakers, another natural sequence. A little later on the bankers bought, but they could not afford such swell turnouts as those who entered the field earlier. So it will go down the line. Somewhere, probably as a tailender, the newspaper man will get in.” This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection, is of a Buick climbing Slaughterhouse Hill in Boise. The hill was a popular place to test the abilities of cars around 1910. It was, and perhaps still is if development hasn’t shaved it off, located a little north of the end of Harrison Boulevard.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection, is of a Buick climbing Slaughterhouse Hill in Boise. The hill was a popular place to test the abilities of cars around 1910. It was, and perhaps still is if development hasn’t shaved it off, located a little north of the end of Harrison Boulevard.

That was nothing, though, because the Hailey News-Miner reported the first automobile to be seen on the streets in Hailey more than a year earlier, in June 1903. The paper noted that “A Hailey lad was on the race track when the auto passed. On first seeing it approach he shouted out: ‘Here comes a runaway with the tongue out!’”

By 1905, autos were common enough in the capital city that the Idaho Statesman noted the first one to be seized in a legal process.

In 1907, that same paper told about the first car to make a long, arduous journey from Boise to Horseshoe Bend. It took the car, a White Steamer, an hour and a half to get to Pearl on the way to Horsehoe Bend. On the way back they did the trip from Pearl in an hour and 20 minutes, “the car behaving so well that at no time were they compelled to stop or do anything to the machine.”

That same year the first automobile reached Silver City, giving citizens their first look at a “Buzz Wagon.” The Statesman reported that “Many young and older people here had never seen an automobile before, and there have been many visitors at Gardener’s barn to look it over.”

By 1909 cars were old hat. The Statesman ran a humorous piece about the inevitability of car ownership. “It will be recalled that the first automobile was purchased by a Boise ice man. That is in harmony with fixed conditions. Luxuries are always secured first by the wealthiest classes. Then a plumber broke in. He was logically next. The coal man was a trifle late, though third, but he purchased a machine that eclipsed all others in point of style and speed. The doctors began to purchase, followed by the undertakers, another natural sequence. A little later on the bankers bought, but they could not afford such swell turnouts as those who entered the field earlier. So it will go down the line. Somewhere, probably as a tailender, the newspaper man will get in.”

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection, is of a Buick climbing Slaughterhouse Hill in Boise. The hill was a popular place to test the abilities of cars around 1910. It was, and perhaps still is if development hasn’t shaved it off, located a little north of the end of Harrison Boulevard.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection, is of a Buick climbing Slaughterhouse Hill in Boise. The hill was a popular place to test the abilities of cars around 1910. It was, and perhaps still is if development hasn’t shaved it off, located a little north of the end of Harrison Boulevard.

Published on April 11, 2021 04:30

April 10, 2021

Farragut Drill Halls

Farragut Naval Training Station, which is now Farragut State Park had some unique buildings.

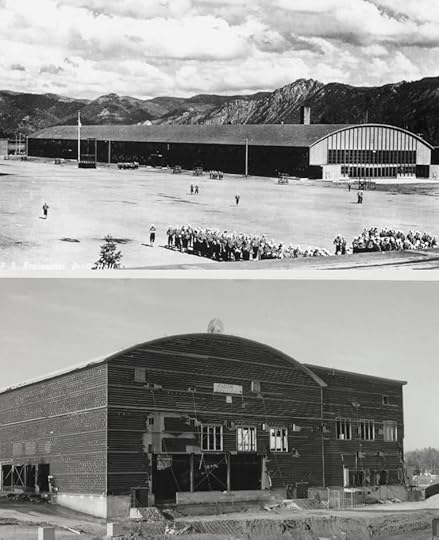

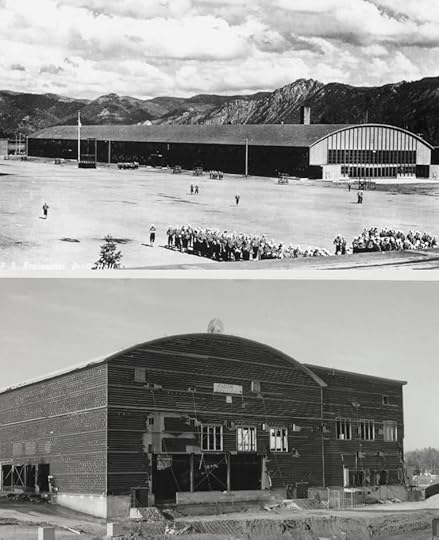

Each of the training camps had drill fields called “grinders” where the recruits marched. The huge regimental drill hall in the background of the top photo allowed training during all kinds of weather. They were billed as the largest clear span (without posts) structures in the world at that time. This particular structure is probably the drill hall at Camp Bennion.

At least two of the drill halls found life after the Navy. One found a new usein Spokane for many years as a Costco. It is still there, just off the Division street exit, and now houses a Goodwill warehouse.

Another of the drill halls was donated to the University of Denver, disassembled, and reassembled on the DU campus in 1948-49. It was used as a hockey arena that fans called “the old barn.” It stood on campus for nearly 50 years.

Above, one of the drill halls at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Below, the drill hall that was converted into a hockey arena in Denver. It was being torn down in this shot.

Above, one of the drill halls at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Below, the drill hall that was converted into a hockey arena in Denver. It was being torn down in this shot.

Each of the training camps had drill fields called “grinders” where the recruits marched. The huge regimental drill hall in the background of the top photo allowed training during all kinds of weather. They were billed as the largest clear span (without posts) structures in the world at that time. This particular structure is probably the drill hall at Camp Bennion.

At least two of the drill halls found life after the Navy. One found a new usein Spokane for many years as a Costco. It is still there, just off the Division street exit, and now houses a Goodwill warehouse.

Another of the drill halls was donated to the University of Denver, disassembled, and reassembled on the DU campus in 1948-49. It was used as a hockey arena that fans called “the old barn.” It stood on campus for nearly 50 years.

Above, one of the drill halls at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Below, the drill hall that was converted into a hockey arena in Denver. It was being torn down in this shot.

Above, one of the drill halls at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Below, the drill hall that was converted into a hockey arena in Denver. It was being torn down in this shot.

Published on April 10, 2021 04:00

April 9, 2021

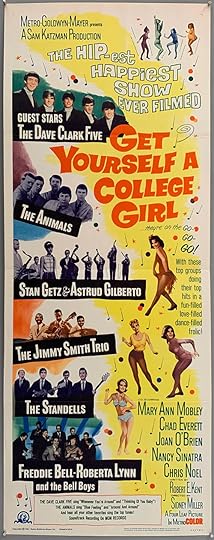

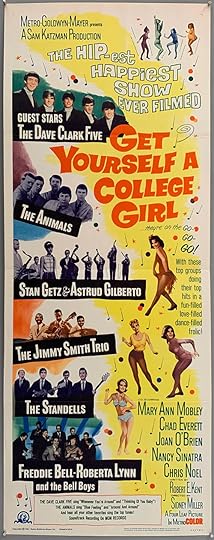

Get Yourself a College Girl

Would it surprise you to learn that “the hip-est, happiest show ever filmed” was shot in Idaho? Yes? Then prepare to be flabbergasted. Get Yourself a College Girl was the movie thus billed. It was so hip that it starred former Miss America Mary Ann Mobley, Chad Everett, and Nancy Sinatra, the latter a couple of years before her hit song about boots.

Not to worry, though. Nancy didn’t sing in the movie, but sooo many others did, including the Standells, Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, The Dave Clark Five, and The Animals. How hip is that? The movie was largely an excuse to have those groups and others perform in front of a camera.

The film was one of many shot in Sun Valley, this one in 1963. It was received. The LA Times called it “inoffensively silly.” Still, it’s with enduring a 30 second commercial to watch the trailer on YouTube.

A movie poster from Get Yourself a College Girl.

A movie poster from Get Yourself a College Girl.

Not to worry, though. Nancy didn’t sing in the movie, but sooo many others did, including the Standells, Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, The Dave Clark Five, and The Animals. How hip is that? The movie was largely an excuse to have those groups and others perform in front of a camera.

The film was one of many shot in Sun Valley, this one in 1963. It was received. The LA Times called it “inoffensively silly.” Still, it’s with enduring a 30 second commercial to watch the trailer on YouTube.

A movie poster from Get Yourself a College Girl.

A movie poster from Get Yourself a College Girl.

Published on April 09, 2021 04:00