Rick Just's Blog, page 128

April 29, 2021

The Wealthiest Woman

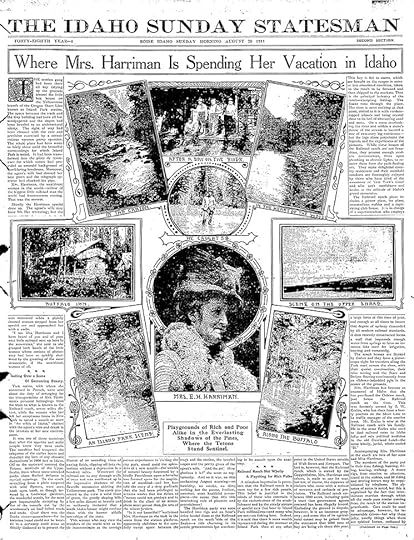

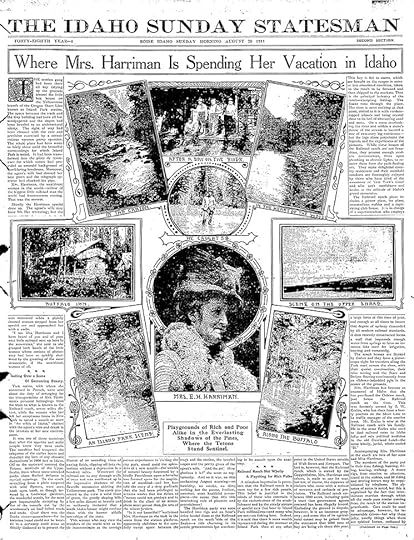

On Sunday, August 20, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran a full-page story with nine photos about a place in Island Park that was hosting a special guest, the “wealthiest woman in the world.” It was the first time Mrs. E.H. (Mary) Harriman would visit the state, but it would not be the last.

E.H. Harriman, “the biggest little railroad man the world had known,” had died in 1909, shortly after purchasing shares in the Island Park Land and Cattle Company. The place was already being called the Railroad Ranch because the men who bought the first 3,000 acres of the property in 1899 were associated with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Harriman, who ran Union Pacific Railroad, solidified that name with his purchase.

The article mentions, without naming them, that Mary Harriman’s sons came along with her. It would be those sons who had the most impact on Idaho, Averell by creating the Sun Valley Resort, and E. Roland by ultimately donating the Railroad Ranch to the State of Idaho to create Harriman State Park of Idaho (the latter two words in the name to distinguish it from Harriman State Park in New York).

The wealth of the Harrimans, the Guggenheims, and other investors did not escape the notice of the unnamed Statesman reporter, who wrote, “it is said that there is more wealth represented during the summer at Island Park than at any other point in the United States outside of Wall Street and Newport.”

Mrs. Harriman fell in love with the place, as did Averell and Roland.

The reporter predicted the future, when he (probably not she) wrote, “The world is open to Mrs. Harriman, but she selected Island Park as the place to spend her summer vacation in 1911; and it is an open secret that she will return next year and the next and indefinitely.”

Over the years there was no shortage of grousing from sportsmen and anglers who felt locked out of the Railroad Ranch, but ultimately saving this jewel of the Gem State was well worth it.

E.H. Harriman, “the biggest little railroad man the world had known,” had died in 1909, shortly after purchasing shares in the Island Park Land and Cattle Company. The place was already being called the Railroad Ranch because the men who bought the first 3,000 acres of the property in 1899 were associated with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Harriman, who ran Union Pacific Railroad, solidified that name with his purchase.

The article mentions, without naming them, that Mary Harriman’s sons came along with her. It would be those sons who had the most impact on Idaho, Averell by creating the Sun Valley Resort, and E. Roland by ultimately donating the Railroad Ranch to the State of Idaho to create Harriman State Park of Idaho (the latter two words in the name to distinguish it from Harriman State Park in New York).

The wealth of the Harrimans, the Guggenheims, and other investors did not escape the notice of the unnamed Statesman reporter, who wrote, “it is said that there is more wealth represented during the summer at Island Park than at any other point in the United States outside of Wall Street and Newport.”

Mrs. Harriman fell in love with the place, as did Averell and Roland.

The reporter predicted the future, when he (probably not she) wrote, “The world is open to Mrs. Harriman, but she selected Island Park as the place to spend her summer vacation in 1911; and it is an open secret that she will return next year and the next and indefinitely.”

Over the years there was no shortage of grousing from sportsmen and anglers who felt locked out of the Railroad Ranch, but ultimately saving this jewel of the Gem State was well worth it.

Published on April 29, 2021 04:00

April 28, 2021

Slaves in Idaho History

Idaho was not involved in the Civil War, though one can find vestiges of that sad chapter of American history in towns and places named by proponents of one side or another. Atlanta and Yankee Fork are two examples.

But slavery played a part in earliest Idaho history.

Lewis and Clark, those great and fortunate explorers who first came into what would later become Idaho brought slavery with them. William Clark owned an African-American man named York. Clark’s father had given the explorer the man when both were boys.

By all accounts York was treated well on the expedition and seemed to find some measure of freedom there, trusted to reconnoiter on his own. He was also given an equal vote with other members of the Corps of Discovery.

York’s taste of freedom turned bitter when he did not receive pay at the end of the journey, as others did. He asked for his freedom, but Clark at refused to grant it. Accounts are not in agreement about what happened to York in the ensuing years. Clark eventually gave him his freedom, but what York did with it is still unclear. One account has him living out his life as an honored member of the Crow tribe.

York has received some recognition. Wikipedia lists two books about him written by Frank X. Walker. A play and an opera were also written about York. Books about the Corps of Discovery often mention him admiringly. A statue of York (pictured) stands in Louisville, Kentucky.

York deserved better from Clark. But, both were men of their times and to expect Clark to behave differently would be to expect him to transcend his upbringing and the life he was accustomed to living.

I can’t resist adding a footnote to this story of a famous slave. York was not the only member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who had been enslaved. Definitions can be tricky, but Sacagawea (or Sacajawea, if you prefer) was taken from her family at about age 12 in a battle between her Lemhi Shoshone Tribe and members of the Hidatsa Tribe. She was sold, or claimed as a gambling prize, by Toussaint Charbonneau and became his wife at age 13.

But slavery played a part in earliest Idaho history.

Lewis and Clark, those great and fortunate explorers who first came into what would later become Idaho brought slavery with them. William Clark owned an African-American man named York. Clark’s father had given the explorer the man when both were boys.

By all accounts York was treated well on the expedition and seemed to find some measure of freedom there, trusted to reconnoiter on his own. He was also given an equal vote with other members of the Corps of Discovery.

York’s taste of freedom turned bitter when he did not receive pay at the end of the journey, as others did. He asked for his freedom, but Clark at refused to grant it. Accounts are not in agreement about what happened to York in the ensuing years. Clark eventually gave him his freedom, but what York did with it is still unclear. One account has him living out his life as an honored member of the Crow tribe.

York has received some recognition. Wikipedia lists two books about him written by Frank X. Walker. A play and an opera were also written about York. Books about the Corps of Discovery often mention him admiringly. A statue of York (pictured) stands in Louisville, Kentucky.

York deserved better from Clark. But, both were men of their times and to expect Clark to behave differently would be to expect him to transcend his upbringing and the life he was accustomed to living.

I can’t resist adding a footnote to this story of a famous slave. York was not the only member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who had been enslaved. Definitions can be tricky, but Sacagawea (or Sacajawea, if you prefer) was taken from her family at about age 12 in a battle between her Lemhi Shoshone Tribe and members of the Hidatsa Tribe. She was sold, or claimed as a gambling prize, by Toussaint Charbonneau and became his wife at age 13.

Published on April 28, 2021 04:00

April 26, 2021

Tablerock Rocks

The Jellison brothers, C.O., C.L., and E.A., homesteaded near Table Rock in the 1890s with a stone and timber claim. What timber there might have been is long gone, but the stone from the quarries they established is part of Boise’s foundation. So to speak.

Table Rock sandstone makes up the greater part of the old Idaho State Penitentiary, and is used to good effect in the Emmanuel Lutheran Church, the Bown House, St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, the Union Block, Boise City National Bank, the United States Assay Office, Temple Beth Israel, the Borah Building, St. John’s Cathedral, and many others.

In 1906, the Capitol Commission, in charge of building Idaho’s statehouse, purchased one of the Jellison Brothers’ quarries on Table Rock in order to facilitate the construction of Idaho’s seat of government. The Idaho State Capitol is probably the most visible and dramatic use of Table Rock sandstone in Boise.

Sandstone from Table Rock found its way to major buildings all over the state, including the First Presbyterian Church in Idaho Falls, the Administration Building and Brink Hall at the University of Idaho, and Strahorn Hall at the College of Idaho in Caldwell.

Out of state the stone went to a building on the campus of Yale University and was a popular construction material for several downtown Portland buildings.

Working in a quarry is dangerous, and it was often left to inmates at the Idaho State Penitentiary in the early days. In 1903, two inmates were “hurled into eternity” while working on a troublesome boulder. The 10-foot-high rock, said to be 25 feet square, had a crack running through the middle of it. Workers set charges in the split, hoping to blow the rock apart. The blasts had little effect. Inmates John Stewart and William Maney scrambled up to the top of the boulder to clear away rubble for another go at it. That was when the rock came apart, splitting in two and throwing the men 40 feet down the side of the ridge. Neither survived.

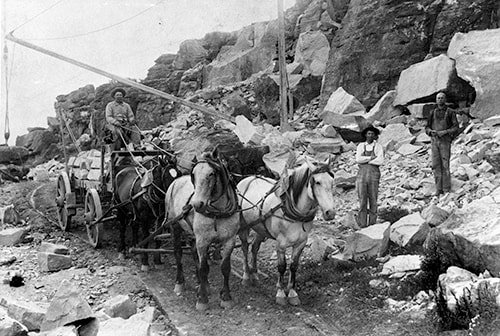

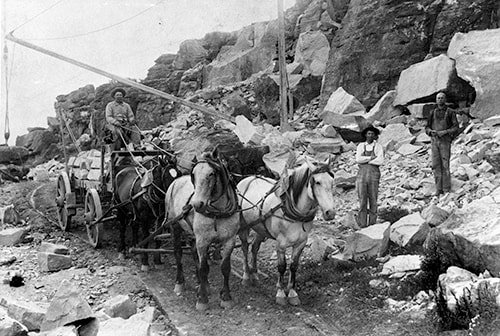

Manpower and horsepower moved a lot of rock from the quarries. In 1912, a new owner of one of the quarries, put electrical power to work. Harry K. Fritchman, a former mayor of Boise, constructed a tramway on rails from the quarry to the Oregon Shortline Railroad, more than a mile away. You can still see the scar of the tramway line on the southeast side of Table Rock.

Ambitious as the tramway was, it was not nearly as aspirational as an idea born in 1907. That year one of the Jellison brothers announced that he was going to build a luxury hotel on top of Table Rock. He envisioned spectacular views from the resort which would rise up from the center of a 685-acre parcel appropriately landscaped. An extension from the Boise Valley Electric line would run to the top of Table Rock and circle around the perimeter. One can imagine geothermal water from nearby wells heating pools and spas in the development. The quarry would be stubbed into the line for transport of stone.

Alas, 1907 was also the year of the “Banker’s Panic,” which sank big money plans like a rock. So, Table Rock is not known today for its splendid hotel. Its history is written in rock, though, still providing sandstone for Boise and beyond. Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Table Rock sandstone makes up the greater part of the old Idaho State Penitentiary, and is used to good effect in the Emmanuel Lutheran Church, the Bown House, St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, the Union Block, Boise City National Bank, the United States Assay Office, Temple Beth Israel, the Borah Building, St. John’s Cathedral, and many others.

In 1906, the Capitol Commission, in charge of building Idaho’s statehouse, purchased one of the Jellison Brothers’ quarries on Table Rock in order to facilitate the construction of Idaho’s seat of government. The Idaho State Capitol is probably the most visible and dramatic use of Table Rock sandstone in Boise.

Sandstone from Table Rock found its way to major buildings all over the state, including the First Presbyterian Church in Idaho Falls, the Administration Building and Brink Hall at the University of Idaho, and Strahorn Hall at the College of Idaho in Caldwell.

Out of state the stone went to a building on the campus of Yale University and was a popular construction material for several downtown Portland buildings.

Working in a quarry is dangerous, and it was often left to inmates at the Idaho State Penitentiary in the early days. In 1903, two inmates were “hurled into eternity” while working on a troublesome boulder. The 10-foot-high rock, said to be 25 feet square, had a crack running through the middle of it. Workers set charges in the split, hoping to blow the rock apart. The blasts had little effect. Inmates John Stewart and William Maney scrambled up to the top of the boulder to clear away rubble for another go at it. That was when the rock came apart, splitting in two and throwing the men 40 feet down the side of the ridge. Neither survived.

Manpower and horsepower moved a lot of rock from the quarries. In 1912, a new owner of one of the quarries, put electrical power to work. Harry K. Fritchman, a former mayor of Boise, constructed a tramway on rails from the quarry to the Oregon Shortline Railroad, more than a mile away. You can still see the scar of the tramway line on the southeast side of Table Rock.

Ambitious as the tramway was, it was not nearly as aspirational as an idea born in 1907. That year one of the Jellison brothers announced that he was going to build a luxury hotel on top of Table Rock. He envisioned spectacular views from the resort which would rise up from the center of a 685-acre parcel appropriately landscaped. An extension from the Boise Valley Electric line would run to the top of Table Rock and circle around the perimeter. One can imagine geothermal water from nearby wells heating pools and spas in the development. The quarry would be stubbed into the line for transport of stone.

Alas, 1907 was also the year of the “Banker’s Panic,” which sank big money plans like a rock. So, Table Rock is not known today for its splendid hotel. Its history is written in rock, though, still providing sandstone for Boise and beyond.

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on April 26, 2021 04:00

April 25, 2021

Chewing Up The Valley

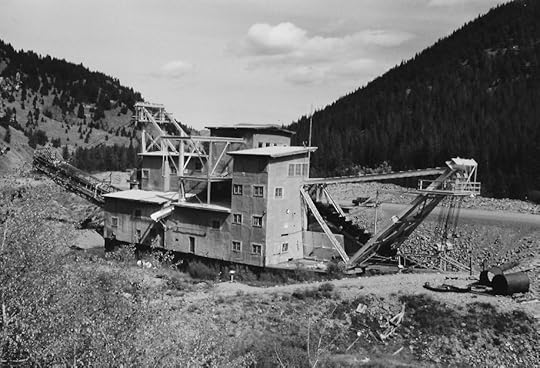

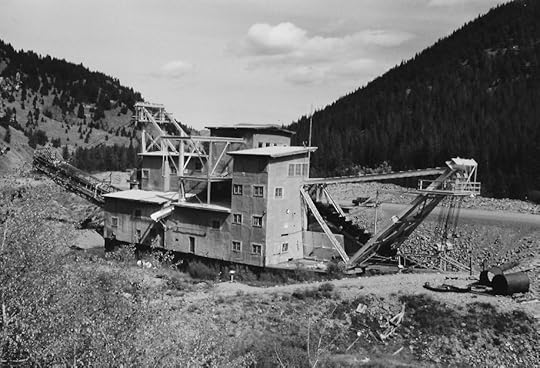

The Yankee Fork Dredge is probably the best-preserved machine of its kind in the lower 48. Built in 1940 by Bucyrus Erie, the machine was designed to pull out the $11 million worth of gold that allegedly sat there for the taking in the gravel bed along a 5 ½ mile stretch of Yankee Fork Creek just before it flows into the Salmon River.

The Silas Mason Company of New York assembled the dredge on site mostly from parts hauled in by train to Mackay, then by truck to the claim. The pontoons that let the dredge float were manufactured in Boise, as was the superstructure.

The dredge weighs 988 tons, and is 112 feet long by 54 feet wide by 64 feet high. Each of the 71 buckets that make up the mouth of the digging chain can hold 8 cubic feet and themselves weigh a little over a ton. Imagine a chain saw with iron buckets linked together instead of a chain. That’s what bit into the creek bottom relentlessly driven by twin 350 hp diesel engines. The gravel fed into a conveyor system inside the dredge where the gold was sifted out. A swinging arm behind the machine spit out gravel in neat arcs producing rock hills in its wake, the ridges of which look like the backbone of a buried dragon.

The dredge worked the claim off and on until 1952. The J.R. Simplot Company bought the operation in 1949.

The dredge didn’t find $11 million in gold, only about $1.5 million. It cost about that to operate, so turning the creek upside down didn’t pay much of a dividend.

Still, the dredge is an interesting place to visit. Regular tours are conducted Memorial Day Weekend through Labor Day. Google it for details.

The Forest Service is planning some ambitious restoration work in the valley, which is the best news the stream has had since 1952.

The photo of the dredge is courtesy of Mario Delisio.

The Silas Mason Company of New York assembled the dredge on site mostly from parts hauled in by train to Mackay, then by truck to the claim. The pontoons that let the dredge float were manufactured in Boise, as was the superstructure.

The dredge weighs 988 tons, and is 112 feet long by 54 feet wide by 64 feet high. Each of the 71 buckets that make up the mouth of the digging chain can hold 8 cubic feet and themselves weigh a little over a ton. Imagine a chain saw with iron buckets linked together instead of a chain. That’s what bit into the creek bottom relentlessly driven by twin 350 hp diesel engines. The gravel fed into a conveyor system inside the dredge where the gold was sifted out. A swinging arm behind the machine spit out gravel in neat arcs producing rock hills in its wake, the ridges of which look like the backbone of a buried dragon.

The dredge worked the claim off and on until 1952. The J.R. Simplot Company bought the operation in 1949.

The dredge didn’t find $11 million in gold, only about $1.5 million. It cost about that to operate, so turning the creek upside down didn’t pay much of a dividend.

Still, the dredge is an interesting place to visit. Regular tours are conducted Memorial Day Weekend through Labor Day. Google it for details.

The Forest Service is planning some ambitious restoration work in the valley, which is the best news the stream has had since 1952.

The photo of the dredge is courtesy of Mario Delisio.

Published on April 25, 2021 04:00

April 24, 2021

A Casualty in the Time of War

It’s September 30, 1918. A young man from Kentucky is shot in the abdomen, later dying of his wounds. His draft registration listed John T. Chesnut as a sheepherder working for Hallstrom and Company in Midvale, Idaho.

Just another casualty of World War I?

In a way, perhaps. Chesnut was watching the Wild West parade in Weiser when mounted cavalry members came trotting by, not in formation, but in a skirmish with an invisible enemy. Their ammunition, appropriate for invisible enemies, was blank. Except for that one round.

Harley McCullough fired at Chesnut, striking him in the stomach. The 28-year-old went down. The parade stopped. Chesnut died.

McCullough was described by the Payette Enterprise as “about twenty years of age and well-known in Payette, …a respectable young man (who) is much grieved over the sad accident.”

The shooter was arrested but released on bail. Charges were likely dropped. I found no evidence of his incarceration.

Chesnut’s hometown paper, the London Sentinel, London, Kentucky, made the leap that it was a military demonstration gone wrong during wartime. I think it’s more likely that the “cavalry” were parade participants dressed up as cavalry members from days gone by. Nevertheless, a tragic accident.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Just another casualty of World War I?

In a way, perhaps. Chesnut was watching the Wild West parade in Weiser when mounted cavalry members came trotting by, not in formation, but in a skirmish with an invisible enemy. Their ammunition, appropriate for invisible enemies, was blank. Except for that one round.

Harley McCullough fired at Chesnut, striking him in the stomach. The 28-year-old went down. The parade stopped. Chesnut died.

McCullough was described by the Payette Enterprise as “about twenty years of age and well-known in Payette, …a respectable young man (who) is much grieved over the sad accident.”

The shooter was arrested but released on bail. Charges were likely dropped. I found no evidence of his incarceration.

Chesnut’s hometown paper, the London Sentinel, London, Kentucky, made the leap that it was a military demonstration gone wrong during wartime. I think it’s more likely that the “cavalry” were parade participants dressed up as cavalry members from days gone by. Nevertheless, a tragic accident.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Published on April 24, 2021 04:00

April 23, 2021

One of Idaho's Famous Drowned Towns

Named for Teddy Roosevelt, the mining town of Roosevelt, Idaho is a footnote in Idaho’s history of disasters. The ramshackle town, east of Yellowpine, started in 1902 when miners first came to the Thunder Mountain District on rumors of a major gold find. The Dewey Mine’s production fell far short of the rumors. It operated for five years, closing in 1907.

A few obstinate miners hung on, but Roosevelt was all but a ghost town in the spring of 1909 when “disaster” struck. It was the slow-moving kind of disaster that occurred without human casualty. A landslide three miles long and 200 feet high plugged Monumental Creek, backing up water and flooding the town. It took a couple of days for the slide to happen, so getting out of its way wasn’t much of a feat. The valley filled in slowly, causing most of the buildings in the town to float.

Mining may have contributed to the slide, but the area was prone to such events and heavy rains were probably the main cause.

There was a bright side to the slide. That mud, moved free of charge by the forces of nature, made some areas easier to mine.

For years the remains of the town bobbed around in Roosevelt Lake. Nowadays you may find a few boards here and there along the shoreline, a reminder of a slow-moving disaster.

The photo of floating buildings on Roosevelt Lake is from the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection. It was taken sometime after 1909.

A few obstinate miners hung on, but Roosevelt was all but a ghost town in the spring of 1909 when “disaster” struck. It was the slow-moving kind of disaster that occurred without human casualty. A landslide three miles long and 200 feet high plugged Monumental Creek, backing up water and flooding the town. It took a couple of days for the slide to happen, so getting out of its way wasn’t much of a feat. The valley filled in slowly, causing most of the buildings in the town to float.

Mining may have contributed to the slide, but the area was prone to such events and heavy rains were probably the main cause.

There was a bright side to the slide. That mud, moved free of charge by the forces of nature, made some areas easier to mine.

For years the remains of the town bobbed around in Roosevelt Lake. Nowadays you may find a few boards here and there along the shoreline, a reminder of a slow-moving disaster.

The photo of floating buildings on Roosevelt Lake is from the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection. It was taken sometime after 1909.

Published on April 23, 2021 04:00

April 22, 2021

Boise's First Home

Boise became a city in 1863. Remarkably, the first home built in what would become Idaho’s capital city is still standing. The O’Farrell cabin was built from cottonwood trees cut down nearby by John A. O’Farrell in June of 1863. O’Farrell used a broad axe to flatten out the logs for his cabin. Branches and clay served as chinking between the logs. Inside, visitors would find a dirt floor and fabric covering the walls.

The following year when bricks and saw-cut lumber became available, O’Farrell improved the cabin by replacing the pole roof with cut rafters and hand-split shingles. He covered the inside walls, floor and ceiling with planks, added a brick fireplace, and installed glass windows.

The O’Farrell family lived in the cabin for seven more years before moving to a brick home.

In 1910 the O’Farrell children donated the old cabin to the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). The DAR moved the home across Fort Street and conducted the first restoration of the little building. Over the years they opened it occasionally for public tours and did some more restoration work. By 1957 the DAR found that it was unable to care for the building, so donated it to the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers. That group erected a roof structure over the entire cabin and installed bars on the windows to protect it.

The City of Boise took ownership of the cabin, and in 1979 the Boise City Historic Preservation Commission did some restoration work. Charles Hummel and the Columbian Club started a fund drive to restore the cabin in 1995. By 2002 the restoration fund was sufficient to bring the cabin back to its 1912 condition, with 85 percent of the original cabin materials still in place.

The O'Farrell cabin as it looks today.

The O'Farrell cabin as it looks today.

The following year when bricks and saw-cut lumber became available, O’Farrell improved the cabin by replacing the pole roof with cut rafters and hand-split shingles. He covered the inside walls, floor and ceiling with planks, added a brick fireplace, and installed glass windows.

The O’Farrell family lived in the cabin for seven more years before moving to a brick home.

In 1910 the O’Farrell children donated the old cabin to the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). The DAR moved the home across Fort Street and conducted the first restoration of the little building. Over the years they opened it occasionally for public tours and did some more restoration work. By 1957 the DAR found that it was unable to care for the building, so donated it to the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers. That group erected a roof structure over the entire cabin and installed bars on the windows to protect it.

The City of Boise took ownership of the cabin, and in 1979 the Boise City Historic Preservation Commission did some restoration work. Charles Hummel and the Columbian Club started a fund drive to restore the cabin in 1995. By 2002 the restoration fund was sufficient to bring the cabin back to its 1912 condition, with 85 percent of the original cabin materials still in place.

The O'Farrell cabin as it looks today.

The O'Farrell cabin as it looks today.

Published on April 22, 2021 04:00

April 21, 2021

The Cowpuncher

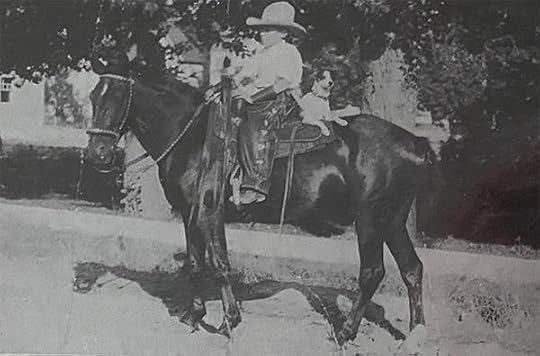

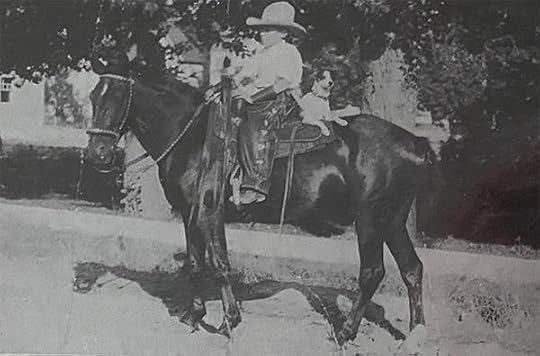

The first motion picture filmed in Idaho left few tracks. One still from the picture remains along with a copy of the play it was developed from, and a poor-quality publicity shot from a newspaper.

Shot in 1915, The Cowpuncher used sites in and around Idaho Falls, including Wolverine Canyon, Taylor Mountain, and various street scenes. Much of the movie revolved around the War Bonnet Roundup that year.

The filming caused quite a stir in Idaho Falls, with the Idaho Register reporting that “Several thousand people forgot to go to church Sunday morning,” going instead to see the shooting of one of the big scenes of the movie.

There might have been a touch of hype when writers described the film. The Evening Capital News in March 1916 said, “Some of the best known motion picture stars were brought to Idaho to film this feature and that they have turned out a masterpiece is conceded by all who have seen the picture.”

C.M. Griffin, Claudia Louise, and Maria Ascaraga were the “best known” stars in the film, none of who even rate an IMDb mention today.

Motion Picture News in its December 25, 1915 edition stated, “It is not likely that a more massive and pretentious Western Picture will ever be attempted.” Clearly, Heaven’s Gate, also shot in Idaho, was decades beyond the writer’s imagination.

Tom Trusky, who knew how to track down information on lost films, was able to locate an Idaho Falls man, Paul Fisher, in 1990. Fisher had appeared in the film as a boy, and he gave Trusky the still below.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.  This publicity photo from The Cowpuncher appeared in the Evening Capital News in Boise in 1916.

This publicity photo from The Cowpuncher appeared in the Evening Capital News in Boise in 1916.  Chief Redwing in a publicity still from the 1911 film Plains Across. Redwing later appeared in The Cowpuncher.

Chief Redwing in a publicity still from the 1911 film Plains Across. Redwing later appeared in The Cowpuncher.

Shot in 1915, The Cowpuncher used sites in and around Idaho Falls, including Wolverine Canyon, Taylor Mountain, and various street scenes. Much of the movie revolved around the War Bonnet Roundup that year.

The filming caused quite a stir in Idaho Falls, with the Idaho Register reporting that “Several thousand people forgot to go to church Sunday morning,” going instead to see the shooting of one of the big scenes of the movie.

There might have been a touch of hype when writers described the film. The Evening Capital News in March 1916 said, “Some of the best known motion picture stars were brought to Idaho to film this feature and that they have turned out a masterpiece is conceded by all who have seen the picture.”

C.M. Griffin, Claudia Louise, and Maria Ascaraga were the “best known” stars in the film, none of who even rate an IMDb mention today.

Motion Picture News in its December 25, 1915 edition stated, “It is not likely that a more massive and pretentious Western Picture will ever be attempted.” Clearly, Heaven’s Gate, also shot in Idaho, was decades beyond the writer’s imagination.

Tom Trusky, who knew how to track down information on lost films, was able to locate an Idaho Falls man, Paul Fisher, in 1990. Fisher had appeared in the film as a boy, and he gave Trusky the still below.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.  This publicity photo from The Cowpuncher appeared in the Evening Capital News in Boise in 1916.

This publicity photo from The Cowpuncher appeared in the Evening Capital News in Boise in 1916.  Chief Redwing in a publicity still from the 1911 film Plains Across. Redwing later appeared in The Cowpuncher.

Chief Redwing in a publicity still from the 1911 film Plains Across. Redwing later appeared in The Cowpuncher.

Published on April 21, 2021 04:00

April 20, 2021

A Solitary Parking Meter

How small is it? That sounds like a joke set-up, rather than the beginning of a totally serious story about Murphy, Idaho and its famous parking meter.

In January, 1956, the Associated Press fed a story to their wire service subscribers about Murphy, Idaho’s solitary parking meter. Murphy, at the time, had only 31 residents, which probably made it the county seat with the smallest population in the country. Since then population has skyrocketed to nearly 100 people.

But, about that parking meter… Kenneth Downing, then the county clerk, thought it might be a good gag to install a parking meter in front of a wire gate at the courthouse that people were always blocking with their cars. It seemed to cut down on the pesky parking, but it didn’t raise a lot of money. It didn’t even work, at first. City fathers, or city jokesters, or someone later repaired it so they could collect coins. Theoretically.

Downing appeared in the AP photo that accompanied the story tying his horse up to the meter. The article pointed out that there were probably more horses in the county than cars, anyway.

You can still visit Owyhee County’s only parking meter today, more than 50 years later, making this one long-running joke.

In January, 1956, the Associated Press fed a story to their wire service subscribers about Murphy, Idaho’s solitary parking meter. Murphy, at the time, had only 31 residents, which probably made it the county seat with the smallest population in the country. Since then population has skyrocketed to nearly 100 people.

But, about that parking meter… Kenneth Downing, then the county clerk, thought it might be a good gag to install a parking meter in front of a wire gate at the courthouse that people were always blocking with their cars. It seemed to cut down on the pesky parking, but it didn’t raise a lot of money. It didn’t even work, at first. City fathers, or city jokesters, or someone later repaired it so they could collect coins. Theoretically.

Downing appeared in the AP photo that accompanied the story tying his horse up to the meter. The article pointed out that there were probably more horses in the county than cars, anyway.

You can still visit Owyhee County’s only parking meter today, more than 50 years later, making this one long-running joke.

Published on April 20, 2021 04:00

April 19, 2021

A Better Name

It makes me uncomfortable even writing this, but history is history. According to a 1949 edition of the Mullan News, Mullan was not always called Mullan. The name it has today honors John Mullan because it was located on the military road he had built. The town was platted in 1888. In 1889 the Northern Pacific Railroad made a stab at changing the name when they built a station there and called it Ryan Station after a railroad official. Residents stuck with the name they’d picked, honoring the famous captain.

So, I’m not uncomfortable yet. What gives me pause is that, again, according to that 1949 paper, the area was originally called Nigger Prairie. It was so named because they found a negro who had died and buried him across from the (then) present site of the Congregational church.

Changing the name had nothing to do with modern sensibilities, but I’m glad they saw fit to do so. Thanks to Heather Callah for bringing this story to my attention.

The picture is of John Mullan late in his life.

So, I’m not uncomfortable yet. What gives me pause is that, again, according to that 1949 paper, the area was originally called Nigger Prairie. It was so named because they found a negro who had died and buried him across from the (then) present site of the Congregational church.

Changing the name had nothing to do with modern sensibilities, but I’m glad they saw fit to do so. Thanks to Heather Callah for bringing this story to my attention.

The picture is of John Mullan late in his life.

Published on April 19, 2021 04:00