Rick Just's Blog, page 131

March 29, 2021

A Railroad with a Distinction

Arrowrock Dam, dedicated in 1915, was the tallest dam in the world, for a few years. You probably knew that. Did you know the railroad line that was built from the community of Barber all the way along the Boise River to the construction site of the Arrowrock Dam was the first publicly owned railroad line in the country?

The Barber Lumber Company wanted a rail line along the river that could haul timber out of the mountains. They owned the right of way where the line would need to go. The Bureau of Reclamation needed a way to get material back and forth to and from the dam site, so they worked out an agreement with Barber Lumber company where Reclamation would lease the tracks and run the railroad. That made the Arrowrock and Barber Railroad the first publicly owned line in the nation.

The Arrowrock and Barber Railroad ran from—wait for it—Arrowrock to Barber and back. The Oregon Shortline ran from Barber to the new Reclamation office in Boise, where materials were warehoused and sent to the construction site as needed. The Reclamation Service Boise Project Office, at 214 Broadway Avenue in Boise, was listed on the National Register of Historic Place in 2010.

Working on the railroad, in this case the Arrowrock to Barber Railroad.

Working on the railroad, in this case the Arrowrock to Barber Railroad.

The Barber Lumber Company wanted a rail line along the river that could haul timber out of the mountains. They owned the right of way where the line would need to go. The Bureau of Reclamation needed a way to get material back and forth to and from the dam site, so they worked out an agreement with Barber Lumber company where Reclamation would lease the tracks and run the railroad. That made the Arrowrock and Barber Railroad the first publicly owned line in the nation.

The Arrowrock and Barber Railroad ran from—wait for it—Arrowrock to Barber and back. The Oregon Shortline ran from Barber to the new Reclamation office in Boise, where materials were warehoused and sent to the construction site as needed. The Reclamation Service Boise Project Office, at 214 Broadway Avenue in Boise, was listed on the National Register of Historic Place in 2010.

Working on the railroad, in this case the Arrowrock to Barber Railroad.

Working on the railroad, in this case the Arrowrock to Barber Railroad.

Published on March 29, 2021 04:00

March 28, 2021

Beehive Burners

I have a special memory about beehive burners, sometimes called teepee or wigwam burners. Shaped something like each item they are named after, they were a common sight in 1960. My memory proves it.

My parents brought me along that summer on a trip that took us from our ranch on the Blackfoot River all the way to Edmonton, Alberta, Canada and back. We had a near-new 1959 Ford pickup and a new slide-in camper with a sleeping compartment hanging over the cab. They were the latest invention. We saw exactly two of them on our two-week trip.

And that has what to do with beehive burners? I spotted one on our way north out of Idaho Falls. Pop told me that they were used to burn off wood waste from lumber mills. Not many miles down the road, we saw another, then another. My mother had bought 10-year-old me a book, or series of books, called I Spy to keep me entertained on the long road trip. I was already geared up to check off various objects I spied from chickens to radio antennas, so it made sense for me to start counting beehive burners.

I spent much of the road trip sprawled across the bed above the cab staring out of the tiny forward-facing windows, flouting future road rules. If I didn’t see a beehive burner first, my parents would pound on the roof to let me know there was one nearby. By the time we got back home I had tallied 50 of them.

Take that same trip today and you might see a few, mostly relics of bygone days not yet turned into scrap.

Beehive burners were typically fed by a conveyor belt that moved sawdust, woodchips, and snaggled branches into a hole near their top. The wood detritus fell onto the pile of burning debris below. On top of the burners was a smoke vent covered in steel mesh to help keep sparks from flying too far.

Air quality concerns have shut the things down in many places. They belch a lot of smoke. Lumber operations produce much less waste today, too, using what was once burned for particle board and mulch.

This is a picture of a beehive or wigwam burner operating at the Louisiana-Pacific lumber plant near Post Falls in 1973. The photo is from the U.S. National Archives, David Falconer photographer.

This is a picture of a beehive or wigwam burner operating at the Louisiana-Pacific lumber plant near Post Falls in 1973. The photo is from the U.S. National Archives, David Falconer photographer.

My parents brought me along that summer on a trip that took us from our ranch on the Blackfoot River all the way to Edmonton, Alberta, Canada and back. We had a near-new 1959 Ford pickup and a new slide-in camper with a sleeping compartment hanging over the cab. They were the latest invention. We saw exactly two of them on our two-week trip.

And that has what to do with beehive burners? I spotted one on our way north out of Idaho Falls. Pop told me that they were used to burn off wood waste from lumber mills. Not many miles down the road, we saw another, then another. My mother had bought 10-year-old me a book, or series of books, called I Spy to keep me entertained on the long road trip. I was already geared up to check off various objects I spied from chickens to radio antennas, so it made sense for me to start counting beehive burners.

I spent much of the road trip sprawled across the bed above the cab staring out of the tiny forward-facing windows, flouting future road rules. If I didn’t see a beehive burner first, my parents would pound on the roof to let me know there was one nearby. By the time we got back home I had tallied 50 of them.

Take that same trip today and you might see a few, mostly relics of bygone days not yet turned into scrap.

Beehive burners were typically fed by a conveyor belt that moved sawdust, woodchips, and snaggled branches into a hole near their top. The wood detritus fell onto the pile of burning debris below. On top of the burners was a smoke vent covered in steel mesh to help keep sparks from flying too far.

Air quality concerns have shut the things down in many places. They belch a lot of smoke. Lumber operations produce much less waste today, too, using what was once burned for particle board and mulch.

This is a picture of a beehive or wigwam burner operating at the Louisiana-Pacific lumber plant near Post Falls in 1973. The photo is from the U.S. National Archives, David Falconer photographer.

This is a picture of a beehive or wigwam burner operating at the Louisiana-Pacific lumber plant near Post Falls in 1973. The photo is from the U.S. National Archives, David Falconer photographer.

Published on March 28, 2021 04:00

March 27, 2021

Little Jo

Have you ever fantasized about starting a new life? Perhaps no one ever did that more completely than Little Jo Monaghan.

Jo showed up in Ruby City, Idaho Territory in 1867 or 1868 determined to try his hand at mining. He was a slight little guy, no more than five feet tall, but he was a real worker. He dug with the best of them for several weeks, then decided mining was just too tough.

Jo Monaghan then became a sheepherder, spending three years mostly in the company of sheep. After that, he worked in a livery for a time and took to breaking horses for a living. He was so good at it that Andrew Whalen hired him to work in Whalen’s Wild West Show, billing the bronc rider as Cowboy Joe. Whalen offered $25 to anyone who could find a horse the man couldn’t ride.

Eventually Jo homesteaded near Rockville, Idaho. He built a cabin and raised a few livestock, living a quiet life. He served on juries and voted in elections. Jo Monaghan was a respected member of the community. A quiet man. Except that he wasn’t

In 1904 Jo Monaghan passed away. The Weiser Signal marked Jo’s death with the headline, "Sex is Discovered After Death" and noted that, "There are a number of people residing in Weiser, who knew the supposed man intimately, and never had a suspicion that she was not what she represented to be."

Jo Monaghan was a woman. Who that woman was is still open to speculation. One story often told is that she was from a wealthy New York family and had found herself in a family way. As that story goes, she left her child for her sister to raise and headed West. It wasn’t uncommon for women at that time to travel as men to help assure their own safety. Jo may have done that and simply found it convenient to keep up the ruse.

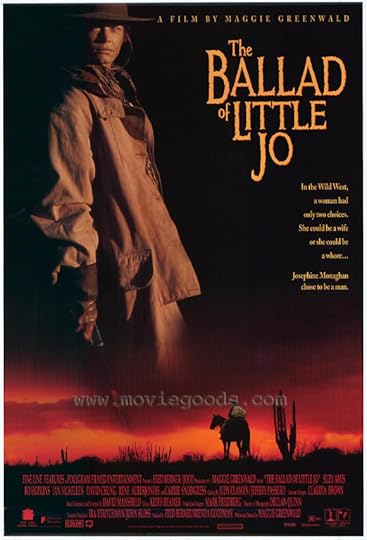

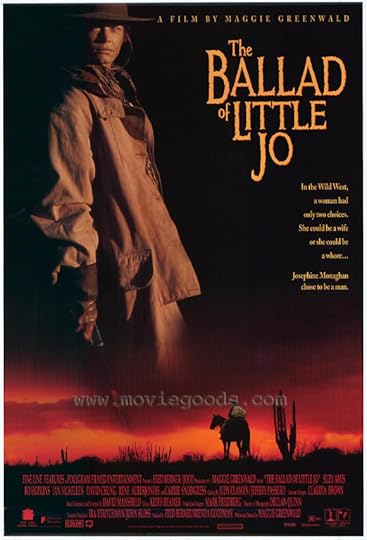

The story has fascinated people for decades. A 1993 movie called The Ballad of Little Joe, written and directed by Maggie Greenwald and starring Suzy Amis as Jo told a version of her life.

The part of the story that always interested me was that he voted. No, make that SHE voted. She might have been one of the first women to cast a vote in the United States.

Jo showed up in Ruby City, Idaho Territory in 1867 or 1868 determined to try his hand at mining. He was a slight little guy, no more than five feet tall, but he was a real worker. He dug with the best of them for several weeks, then decided mining was just too tough.

Jo Monaghan then became a sheepherder, spending three years mostly in the company of sheep. After that, he worked in a livery for a time and took to breaking horses for a living. He was so good at it that Andrew Whalen hired him to work in Whalen’s Wild West Show, billing the bronc rider as Cowboy Joe. Whalen offered $25 to anyone who could find a horse the man couldn’t ride.

Eventually Jo homesteaded near Rockville, Idaho. He built a cabin and raised a few livestock, living a quiet life. He served on juries and voted in elections. Jo Monaghan was a respected member of the community. A quiet man. Except that he wasn’t

In 1904 Jo Monaghan passed away. The Weiser Signal marked Jo’s death with the headline, "Sex is Discovered After Death" and noted that, "There are a number of people residing in Weiser, who knew the supposed man intimately, and never had a suspicion that she was not what she represented to be."

Jo Monaghan was a woman. Who that woman was is still open to speculation. One story often told is that she was from a wealthy New York family and had found herself in a family way. As that story goes, she left her child for her sister to raise and headed West. It wasn’t uncommon for women at that time to travel as men to help assure their own safety. Jo may have done that and simply found it convenient to keep up the ruse.

The story has fascinated people for decades. A 1993 movie called The Ballad of Little Joe, written and directed by Maggie Greenwald and starring Suzy Amis as Jo told a version of her life.

The part of the story that always interested me was that he voted. No, make that SHE voted. She might have been one of the first women to cast a vote in the United States.

Published on March 27, 2021 04:00

March 26, 2021

Kullyspell House

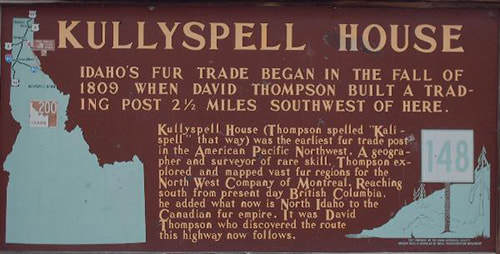

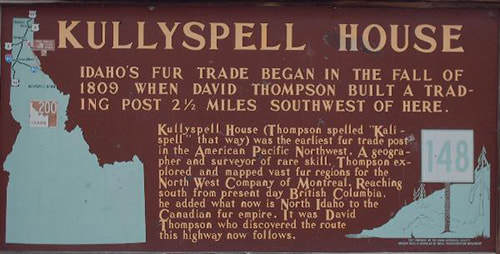

In 1809 explorer David Thompson, who worked for the North West Company, directed the construction of the first white establishment in what later became Idaho.

The trading post, called Kullyspell House, was located near present day Hope, about 16 miles from Sandpoint. The historical marker is on Idaho 200 at about mile marker 48.

It was made of split logs and had two big stone chimneys. It was the chimneys that lasted the longest. For 87 years they stood like tombstones against the elements before finally toppling in a big windstorm. With the chimneys fallen, Kullyspell House all but vanished.

In time, even the locals forgot its exact location.

Then in 1928 a group of Idaho pioneers and historians set out to settle the question of just where Kullyspell House had been located. Ironically, they used a blind man as their guide. An aged Indian named Kali Too remembered seeing the chimneys as a child. Even though Kali Too had been blind for many years he remembered the landscape clearly. He told the group to go to a certain point along the shore of Lake Pend Oreille. From there, he told them to look for a big rock that was shaped like a bear's paw. Sure enough, when they got to the site there was a rock that looked like a bear's paw. From there the old Indian directed the party inland. In just a few minutes a cheer went up. They had found a pile of rocks that might once have been the missing chimneys. Later archaeological research proved it. Kullyspell House--or what was left of it--had been found. You might call it blind luck.

The trading post, called Kullyspell House, was located near present day Hope, about 16 miles from Sandpoint. The historical marker is on Idaho 200 at about mile marker 48.

It was made of split logs and had two big stone chimneys. It was the chimneys that lasted the longest. For 87 years they stood like tombstones against the elements before finally toppling in a big windstorm. With the chimneys fallen, Kullyspell House all but vanished.

In time, even the locals forgot its exact location.

Then in 1928 a group of Idaho pioneers and historians set out to settle the question of just where Kullyspell House had been located. Ironically, they used a blind man as their guide. An aged Indian named Kali Too remembered seeing the chimneys as a child. Even though Kali Too had been blind for many years he remembered the landscape clearly. He told the group to go to a certain point along the shore of Lake Pend Oreille. From there, he told them to look for a big rock that was shaped like a bear's paw. Sure enough, when they got to the site there was a rock that looked like a bear's paw. From there the old Indian directed the party inland. In just a few minutes a cheer went up. They had found a pile of rocks that might once have been the missing chimneys. Later archaeological research proved it. Kullyspell House--or what was left of it--had been found. You might call it blind luck.

Published on March 26, 2021 04:00

March 25, 2021

The Misses Mudge

Sometimes you can go just so far in historical research. That can be frustrating if there is clearly a story there to uncover. Or, as in the case of the Misses Mudge, it can be a couple of hours spent getting the bones of a story from a single clue. That’s satisfying in itself, even if it doesn’t add much to the historical record.

I found a photograph among my great grandparent’s collections that sent me on a little journey. Nels and Emma Just were Idaho pioneers who came to the state (separately) in 1863. They met in 1870 during the construction of the military Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek. She was baking bread for the soldiers and living with her aunt and uncle nearby. He was a freighter who counted the fort an occasional customer.

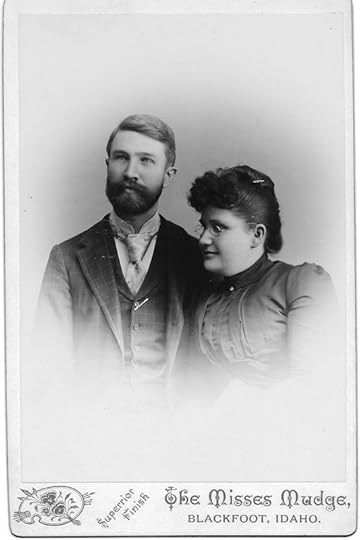

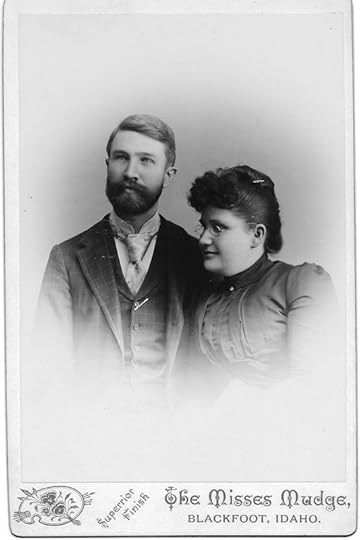

The photo, below, is of Fort Hall’s Dr. Gregory and his wife. I’ll research them for another post. This is not about the photo itself, but about the photographers, The Misses Mudge. I was able to develop an interesting post from a similar clue found on another photo in that collection, leading me to learn more about the Union Pacific Photo Car. I wasn’t as successful with this search, but I’ll tell you what I learned.

The photograph of the doctor and his wife is a good example of a cabinet card. Cabinet cards were introduced in the 1860s, and were especially popular in the 1870s, 80s, and 90s. They disappeared from popular use in the 1930s.

Cabinet cards, thin photos mounted on card stock that formed its own frame, were designed to be placed on a cabinet, shelf, or dresser to display a favorite photo. They were larger than the photographic type they replaced, small carte de viste photos most often displayed in an album. Cabinet card brought photos out for everyone to view.

It was common for photographers to put their imprint on the front and something about their business on the back. What drew me to the creator or creators of this cabinet card was the name, “The Misses Mudge.” I’m a sucker for alliteration and I’m always on the lookout for jobs women were doing in earlier days that one might not have expected.

Women photographers were not especially rare, but the Mudges were probably the first to set up shop in Blackfoot. Years later (the 1950s and 1960s) Grace Sandberg would be THE photographer in Blackfoot.

What drew the Mudges to Idaho? I wasn’t able to learn that, but we know it wasn’t accidental. The sisters Kathrine Raymond Mudge and Caroline Alide Mudge, sent samples of their work ahead of their arrival to be put on display in the Blackfoot Post Office. That was in May 1892.

“The Misses Mudge, of Randalis, Iowa, will be here in about two weeks to open a photograph gallery. They come highly recommended, but their work will be on exhibition at the post office within a few days and will speak for itself. Notice it and judge of it.”

The sisters went by Kate and Carry. It took some sleuthing to learn that. Carry was mentioned by name exactly once in the Blackfoot paper, Kate a handful of times. Whenever the mention involved photography, and often when it didn’t, they were called The Misses Mudge.

In August 1892, they had set up their gallery “south of Hopkins lumber.” It was open four days a week, Wednesday through Saturday, saving Mondays and Tuesdays for “finishing work.” Portraits were their bread and butter, but the Mudge sisters made the papers when they travelled to Fort Hall to take pictures of various things, and when they shot group photos.

The Misses Mudge closed their gallery in December, probably to winter in California. They were back in Blackfoot the following spring taking photos and taking part in community activities. They often sang as a duet for various functions, particularly those sponsored by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

In July 1893 The Misses Mudge were advertising their cabinet photos for $3 a dozen. That seems like a bargain, at least until you consider what wages were at that time. A farmworker was making about $13 a month.

The sisters took a train to California in October 1893. They came back the following spring, but little mention was made of them after that. In 1904, Kate came back for a visit.

The Misses Mudge, and a third sister, Rosela Emma “Rose” Mudge, ended up in Redlands, California. All three had been teachers at some time in their lives. None of them ever married. The three sisters are buried in Redlands.

We will probably never know what brought them to Blackfoot that summer of 1892. They left their mark in family photo albums of the time, many of which are still around. One thing they did not leave behind, at least for me to find, was a picture of The Misses Mudge.

I found a photograph among my great grandparent’s collections that sent me on a little journey. Nels and Emma Just were Idaho pioneers who came to the state (separately) in 1863. They met in 1870 during the construction of the military Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek. She was baking bread for the soldiers and living with her aunt and uncle nearby. He was a freighter who counted the fort an occasional customer.

The photo, below, is of Fort Hall’s Dr. Gregory and his wife. I’ll research them for another post. This is not about the photo itself, but about the photographers, The Misses Mudge. I was able to develop an interesting post from a similar clue found on another photo in that collection, leading me to learn more about the Union Pacific Photo Car. I wasn’t as successful with this search, but I’ll tell you what I learned.

The photograph of the doctor and his wife is a good example of a cabinet card. Cabinet cards were introduced in the 1860s, and were especially popular in the 1870s, 80s, and 90s. They disappeared from popular use in the 1930s.

Cabinet cards, thin photos mounted on card stock that formed its own frame, were designed to be placed on a cabinet, shelf, or dresser to display a favorite photo. They were larger than the photographic type they replaced, small carte de viste photos most often displayed in an album. Cabinet card brought photos out for everyone to view.

It was common for photographers to put their imprint on the front and something about their business on the back. What drew me to the creator or creators of this cabinet card was the name, “The Misses Mudge.” I’m a sucker for alliteration and I’m always on the lookout for jobs women were doing in earlier days that one might not have expected.

Women photographers were not especially rare, but the Mudges were probably the first to set up shop in Blackfoot. Years later (the 1950s and 1960s) Grace Sandberg would be THE photographer in Blackfoot.

What drew the Mudges to Idaho? I wasn’t able to learn that, but we know it wasn’t accidental. The sisters Kathrine Raymond Mudge and Caroline Alide Mudge, sent samples of their work ahead of their arrival to be put on display in the Blackfoot Post Office. That was in May 1892.

“The Misses Mudge, of Randalis, Iowa, will be here in about two weeks to open a photograph gallery. They come highly recommended, but their work will be on exhibition at the post office within a few days and will speak for itself. Notice it and judge of it.”

The sisters went by Kate and Carry. It took some sleuthing to learn that. Carry was mentioned by name exactly once in the Blackfoot paper, Kate a handful of times. Whenever the mention involved photography, and often when it didn’t, they were called The Misses Mudge.

In August 1892, they had set up their gallery “south of Hopkins lumber.” It was open four days a week, Wednesday through Saturday, saving Mondays and Tuesdays for “finishing work.” Portraits were their bread and butter, but the Mudge sisters made the papers when they travelled to Fort Hall to take pictures of various things, and when they shot group photos.

The Misses Mudge closed their gallery in December, probably to winter in California. They were back in Blackfoot the following spring taking photos and taking part in community activities. They often sang as a duet for various functions, particularly those sponsored by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

In July 1893 The Misses Mudge were advertising their cabinet photos for $3 a dozen. That seems like a bargain, at least until you consider what wages were at that time. A farmworker was making about $13 a month.

The sisters took a train to California in October 1893. They came back the following spring, but little mention was made of them after that. In 1904, Kate came back for a visit.

The Misses Mudge, and a third sister, Rosela Emma “Rose” Mudge, ended up in Redlands, California. All three had been teachers at some time in their lives. None of them ever married. The three sisters are buried in Redlands.

We will probably never know what brought them to Blackfoot that summer of 1892. They left their mark in family photo albums of the time, many of which are still around. One thing they did not leave behind, at least for me to find, was a picture of The Misses Mudge.

Published on March 25, 2021 04:00

March 24, 2021

Idaho's First Radio Station

This story starts in September of 1917, when Harry Redeker was hired as a chemistry and physics teacher at Boise High School. In the evenings, he taught Morse Code to young men who were about to head into the maw of World War One.

After the war, Redeker got his amateur radio license and continued the classes, this time broadcasting on station 7YA starting in December 1919. The student station eventually began broadcasting music and speech, thanks to improved equipment and technology.

On July 18, 1922, radio station KFAU was first licensed. It started broadcasting on July 20.

There wasn’t a lot of competition on the radio dial, so the station had some impact. On July 30, 1922, the Idaho Statesman reported that listeners could clearly hear the station in Kuna, Nampa, Caldwell, Parma, Payette, Weiser, and Ontario. Some reported hearing it in Twin Falls and St. Anthony. Listeners heard live music performed by local musicians, religious broadcasts, and a speech by Sen. William Borah.

Under Redeker’s guidance and with community support the station grew, increasing its power to 4,000 watts during the day and 2,000 watts at night in 1926. Daytime production was handled by Boise High School students, while the Boise Chamber of Commerce took over at night. Notably, the Chamber also began financing the radio station.

By 1927 the station had become so popular that there was pressure on the school board to sell KFAU so that it could become Idaho’s first commercial station. The Idaho Statesman, which had run dozens of articles and program listings over the years, was making plans of its own to start a commercial radio station, though those plans never reached fruition.

With increasing controversy over the fate of the station, some of the fun had gone out of the project for Harry Redeker. He took a job in California.

In September, 1928, KFAU was sold to Curtis G. Phillips and Frank Hill. The call letters changed to KIDO in November of 1928. From that time forward, Phillips went by the nickname “Kido.”

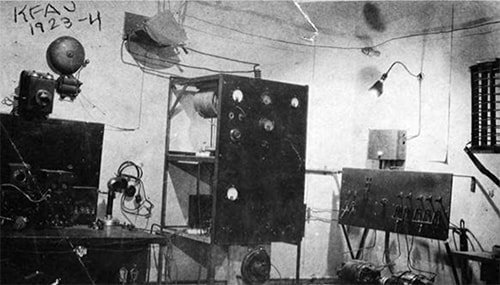

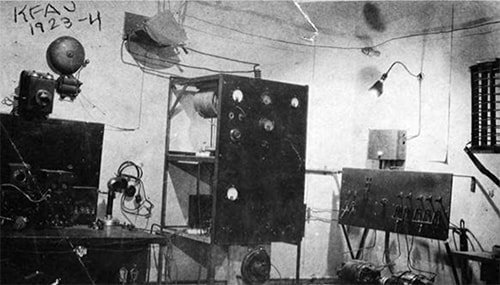

KIDO still broadcasts from Boise today, although that studio in Boise High School, shown in the photo and inset below, is long gone.

Thanks to Art Gregory and the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation, Inc. for their help on this story. KFAU was a high school radio station in 1923. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1923. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

After the war, Redeker got his amateur radio license and continued the classes, this time broadcasting on station 7YA starting in December 1919. The student station eventually began broadcasting music and speech, thanks to improved equipment and technology.

On July 18, 1922, radio station KFAU was first licensed. It started broadcasting on July 20.

There wasn’t a lot of competition on the radio dial, so the station had some impact. On July 30, 1922, the Idaho Statesman reported that listeners could clearly hear the station in Kuna, Nampa, Caldwell, Parma, Payette, Weiser, and Ontario. Some reported hearing it in Twin Falls and St. Anthony. Listeners heard live music performed by local musicians, religious broadcasts, and a speech by Sen. William Borah.

Under Redeker’s guidance and with community support the station grew, increasing its power to 4,000 watts during the day and 2,000 watts at night in 1926. Daytime production was handled by Boise High School students, while the Boise Chamber of Commerce took over at night. Notably, the Chamber also began financing the radio station.

By 1927 the station had become so popular that there was pressure on the school board to sell KFAU so that it could become Idaho’s first commercial station. The Idaho Statesman, which had run dozens of articles and program listings over the years, was making plans of its own to start a commercial radio station, though those plans never reached fruition.

With increasing controversy over the fate of the station, some of the fun had gone out of the project for Harry Redeker. He took a job in California.

In September, 1928, KFAU was sold to Curtis G. Phillips and Frank Hill. The call letters changed to KIDO in November of 1928. From that time forward, Phillips went by the nickname “Kido.”

KIDO still broadcasts from Boise today, although that studio in Boise High School, shown in the photo and inset below, is long gone.

Thanks to Art Gregory and the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation, Inc. for their help on this story.

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1923. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1923. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on March 24, 2021 04:00

March 23, 2021

Jackson Sundown

Did you ever play cowboys and Indians as a kid? Today’s story is about a man who wasn’t playing. He was a cowboy and an Indian.

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn was a nephew of Nez Perce Chief Joseph. He was 14 in 1877 when the flight of the Nez Perce took place across much of Idaho and parts of Oregon, Wyoming, and Montana. His uncle famously surrendered with the eloquent “I will fight no more forever” speech at Bear Paws Battlefield in Montana.

Meanwhile, Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn, wounded, went with a small group of Nez Perce into Canada where he lived for a couple of years with Sitting Bull’s Sioux.

He lived in Washington and Montana, gaining a reputation as a skilled horseman, and a new name, Jackson Sundown, before moving to Idaho in 1910. His skills atop a bucking bronco became so well-known that other riders would simply pull out of the competition when they heard Sundown had signed up. At least one rodeo manager solved that problem by paying Sundown $50 a day for exhibition bronc riding.

In 1911, Sundown along with George Fletcher, who was black, and John Spain, a white cowboy, competed at the Pendleton (Oregon) Roundup in a famous multi-racial showdown. Ken Kesey told that story in his 1995 book, Last Go Round .

In 1915, at the age of 52, Jackson Sundown came in only third in bronc riding at the Pendleton Roundup. He decided to retire. But the next year, Alexander Phimister Proctor, a noted sculptor who was working on a sculpture of Sundown at the time talked the man into riding just once more. Jackson won the saddle bronc competition that day at the age of 53. Many of his competitors were half that age or less.

Jackson Sundown died of pneumonia in 1923. He was buried at Slickpoo Mission Cemetery near Culdesac, Idaho. He was inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 2006.

The picture is Lora Remington Potvin with Jackson Sundown in traditional dress posing in front of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver. The sculptor, Alexander P. Proctor, lived in Lewiston in 1916 and 1917, according to Steve Branting. The photo is courtesy of Steve Branting and Edmond and Lora Potvin Collection.

The picture is Lora Remington Potvin with Jackson Sundown in traditional dress posing in front of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver. The sculptor, Alexander P. Proctor, lived in Lewiston in 1916 and 1917, according to Steve Branting. The photo is courtesy of Steve Branting and Edmond and Lora Potvin Collection.

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn was a nephew of Nez Perce Chief Joseph. He was 14 in 1877 when the flight of the Nez Perce took place across much of Idaho and parts of Oregon, Wyoming, and Montana. His uncle famously surrendered with the eloquent “I will fight no more forever” speech at Bear Paws Battlefield in Montana.

Meanwhile, Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn, wounded, went with a small group of Nez Perce into Canada where he lived for a couple of years with Sitting Bull’s Sioux.

He lived in Washington and Montana, gaining a reputation as a skilled horseman, and a new name, Jackson Sundown, before moving to Idaho in 1910. His skills atop a bucking bronco became so well-known that other riders would simply pull out of the competition when they heard Sundown had signed up. At least one rodeo manager solved that problem by paying Sundown $50 a day for exhibition bronc riding.

In 1911, Sundown along with George Fletcher, who was black, and John Spain, a white cowboy, competed at the Pendleton (Oregon) Roundup in a famous multi-racial showdown. Ken Kesey told that story in his 1995 book, Last Go Round .

In 1915, at the age of 52, Jackson Sundown came in only third in bronc riding at the Pendleton Roundup. He decided to retire. But the next year, Alexander Phimister Proctor, a noted sculptor who was working on a sculpture of Sundown at the time talked the man into riding just once more. Jackson won the saddle bronc competition that day at the age of 53. Many of his competitors were half that age or less.

Jackson Sundown died of pneumonia in 1923. He was buried at Slickpoo Mission Cemetery near Culdesac, Idaho. He was inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 2006.

The picture is Lora Remington Potvin with Jackson Sundown in traditional dress posing in front of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver. The sculptor, Alexander P. Proctor, lived in Lewiston in 1916 and 1917, according to Steve Branting. The photo is courtesy of Steve Branting and Edmond and Lora Potvin Collection.

The picture is Lora Remington Potvin with Jackson Sundown in traditional dress posing in front of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver. The sculptor, Alexander P. Proctor, lived in Lewiston in 1916 and 1917, according to Steve Branting. The photo is courtesy of Steve Branting and Edmond and Lora Potvin Collection.

Published on March 23, 2021 04:00

March 22, 2021

That Table Rock Hotel

You know Table Rock above the Old Idaho Penitentiary in Boise as the flat-topped mountain where the lighted cross stands overlooking the valley. You might also know it as a place where numerous rowdy parties have been held over the years. Do you remember that it is the home of Boise’s rock quarry? Do you recall that the big Boise “B” is located on the west end of the mesa?

Table Rock is all those things. If a plan put forth in 1907 had come to fruition, it would be something quite different.

In November of 1907, the Idaho Statesman ran the headline, “Hotel To Be Built On Table Rock.” J.S. Jellison had purchased his brother’s interest in the quarry on Table Rock, including 685 acres of property.

The hotel Jellison envisioned would be “a delightful summer resort.” Part of the ambitious plan was to run a set of trolley tracks up to the top of the mesa and in a loop around the rim of Table Rock. There was to be a branch line to the quarry to facilitate bringing rock into the valley.

And readers never heard another peep about it again. A trolley loop around the rim of Table Rock would be one more reason today to lament the loss of the Interurban. Perhaps.

Table Rock is all those things. If a plan put forth in 1907 had come to fruition, it would be something quite different.

In November of 1907, the Idaho Statesman ran the headline, “Hotel To Be Built On Table Rock.” J.S. Jellison had purchased his brother’s interest in the quarry on Table Rock, including 685 acres of property.

The hotel Jellison envisioned would be “a delightful summer resort.” Part of the ambitious plan was to run a set of trolley tracks up to the top of the mesa and in a loop around the rim of Table Rock. There was to be a branch line to the quarry to facilitate bringing rock into the valley.

And readers never heard another peep about it again. A trolley loop around the rim of Table Rock would be one more reason today to lament the loss of the Interurban. Perhaps.

Published on March 22, 2021 04:00

March 21, 2021

Indian Rocks State Park

Several parks have come and gone over the 109-year history of state parks in Idaho. One you might remember is Indian Rocks State Park. The Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (technically the Idaho Department of Parks at the time) acquired 3,000 acres south of Pocatello from the US Bureau of Land Management in 1968 through the Federal Recreation and Public Purposes Act for $2.50 an acre. The Indian Rocks State Park visitor center was located on the west side of I-15 at the exit to Lava Hot Springs.

Park planners hoped campers would stop on their way to Yellowstone National Park. They also hoped a planned reservoir nearby would attract boaters and fishermen. The US Army Corps of Engineers decided there was not enough public support for building a reservoir on nearby Marsh Creek. The park closed in 1983 during a state budget crisis, and it never reopened.

The visitor center at Indian Rocks State Park in the 1970s.

The visitor center at Indian Rocks State Park in the 1970s.

Park planners hoped campers would stop on their way to Yellowstone National Park. They also hoped a planned reservoir nearby would attract boaters and fishermen. The US Army Corps of Engineers decided there was not enough public support for building a reservoir on nearby Marsh Creek. The park closed in 1983 during a state budget crisis, and it never reopened.

The visitor center at Indian Rocks State Park in the 1970s.

The visitor center at Indian Rocks State Park in the 1970s.

Published on March 21, 2021 04:00

March 20, 2021

Writers Born in Idaho

Idaho is proud of its writers from Ernest Hemingway to Anthony Doer. Neither of those was born in the state, though. Some who were born here include:

Carol Ryrie Brink, who wrote more than 30 juvenile and adult books, including the 1936 Newbury Prize-winning Caddie Woodlawn . Brink was born in Moscow and attended the University of Idaho. She was awarded an honorary doctorate of letters from U of I in 1965, and Brink Hall on the campus is named for her.

Vardis Fisher was a prolific and gifted writer who created the 12-volume Testament of Man, which depicted human history from cavemen to civilization. He is probably best known today for his historical novel, Children of God, which traced the history of the Mormons, and won the 1939 Harper Prize in Fiction, and his novel Mountain Man (1965) which was adapted for Sydney Pollack's film, Jeremiah Johnson (1972). Fisher was born near Rigby and lived in his later years in Hagerman.

Richard McKenna was born in Mountain Home. He’s best known for the historical novel The Sand Pebbles , which was made into the 1966 film of the same name starring Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough, Richard Crenna, and Candice Bergen.

Sarah Palin sold more than two million copies of her book Going Rogue . The former governor of Alaska and vice-presidential candidate was born in Sandpoint. She received her bachelor’s degree in communication with a journalism emphasis from the University of Idaho in 1987.

Ezra Pound (pictured) was an American expatriate who was as well known for his controversial views as for his poetry. He helped shape the work of T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Robert Frost, Ernest Hemingway and others. His unfinished work The Cantos is much admired still, long after his death in 1972. Pound was born in Hailey, though he spent little time there.

Frank Chester Robertson was born in Moscow. He wrote more than 150 novels and many more short stories. Robertson won the Silver Spur award in 1954 from the Western Writers of America best juvenile story for Sagebrush Sorrel.

Patrick McManus was born in Sandpoint. He wrote a mystery series but is best known Outdoor Life and Field and Stream articles, as well as his many books of backwoods Idaho humor.

Marilynn Robinson, who won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her book Gilead in 2005 was born in Sandpoint. Her book Housekeeping , which is set in Sandpoint, was a Pulitzer finalist in 1982.

Tom Spanbaur grew up outside of Pocatello. He is a gay writer who often explores themes of sexual identity and race. Three of his five novels take place in Idaho, The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon , Now is the Hour, and Faraway Places.

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich was born in Sugar City, Idaho. Her history of midwife Martha Ballard, titled The Midwife’s Tale , won a Pulitzer Prize and was later made into a documentary film for the PBS series American Experience. Oddly, she may enjoy more fame for a single line in a scholarly publication than for her prize-winning work. She is remembered for the line, "well-behaved women seldom make history," which came from an article about Puritan funeral services. She would later write a book with that title.

Douglas Unger was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for his 1984 debut novel Leaving the Land . His other three novels and a collection of short stories have also garnered major nominations and awards. He was born in Moscow.

Tara Westover was born in Clifton, Idaho. Her 2018 memoir Educated was on many best book lists, including the New York Time top ten list for the year.

Emily Ruskovich grew up in the panhandle of Idaho on Hoo Doo Mountain. She now teaches at Boise State University. Her 2017 novel, Idaho , was critically acclaimed.

Elaine Ambrose grew up on a potato farm near Wendell. She is best known for her eight books of humor and recently released a memoir called Frozen Dinners, A Memoir of a Fractured Family .

This is by no means a comprehensive list of writers born in Idaho. I’m happy to hear about those I’ve missed so that they can be included in later lists.

Carol Ryrie Brink, who wrote more than 30 juvenile and adult books, including the 1936 Newbury Prize-winning Caddie Woodlawn . Brink was born in Moscow and attended the University of Idaho. She was awarded an honorary doctorate of letters from U of I in 1965, and Brink Hall on the campus is named for her.

Vardis Fisher was a prolific and gifted writer who created the 12-volume Testament of Man, which depicted human history from cavemen to civilization. He is probably best known today for his historical novel, Children of God, which traced the history of the Mormons, and won the 1939 Harper Prize in Fiction, and his novel Mountain Man (1965) which was adapted for Sydney Pollack's film, Jeremiah Johnson (1972). Fisher was born near Rigby and lived in his later years in Hagerman.

Richard McKenna was born in Mountain Home. He’s best known for the historical novel The Sand Pebbles , which was made into the 1966 film of the same name starring Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough, Richard Crenna, and Candice Bergen.

Sarah Palin sold more than two million copies of her book Going Rogue . The former governor of Alaska and vice-presidential candidate was born in Sandpoint. She received her bachelor’s degree in communication with a journalism emphasis from the University of Idaho in 1987.

Ezra Pound (pictured) was an American expatriate who was as well known for his controversial views as for his poetry. He helped shape the work of T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Robert Frost, Ernest Hemingway and others. His unfinished work The Cantos is much admired still, long after his death in 1972. Pound was born in Hailey, though he spent little time there.

Frank Chester Robertson was born in Moscow. He wrote more than 150 novels and many more short stories. Robertson won the Silver Spur award in 1954 from the Western Writers of America best juvenile story for Sagebrush Sorrel.

Patrick McManus was born in Sandpoint. He wrote a mystery series but is best known Outdoor Life and Field and Stream articles, as well as his many books of backwoods Idaho humor.

Marilynn Robinson, who won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her book Gilead in 2005 was born in Sandpoint. Her book Housekeeping , which is set in Sandpoint, was a Pulitzer finalist in 1982.

Tom Spanbaur grew up outside of Pocatello. He is a gay writer who often explores themes of sexual identity and race. Three of his five novels take place in Idaho, The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon , Now is the Hour, and Faraway Places.

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich was born in Sugar City, Idaho. Her history of midwife Martha Ballard, titled The Midwife’s Tale , won a Pulitzer Prize and was later made into a documentary film for the PBS series American Experience. Oddly, she may enjoy more fame for a single line in a scholarly publication than for her prize-winning work. She is remembered for the line, "well-behaved women seldom make history," which came from an article about Puritan funeral services. She would later write a book with that title.

Douglas Unger was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for his 1984 debut novel Leaving the Land . His other three novels and a collection of short stories have also garnered major nominations and awards. He was born in Moscow.

Tara Westover was born in Clifton, Idaho. Her 2018 memoir Educated was on many best book lists, including the New York Time top ten list for the year.

Emily Ruskovich grew up in the panhandle of Idaho on Hoo Doo Mountain. She now teaches at Boise State University. Her 2017 novel, Idaho , was critically acclaimed.

Elaine Ambrose grew up on a potato farm near Wendell. She is best known for her eight books of humor and recently released a memoir called Frozen Dinners, A Memoir of a Fractured Family .

This is by no means a comprehensive list of writers born in Idaho. I’m happy to hear about those I’ve missed so that they can be included in later lists.

Published on March 20, 2021 04:00