Rick Just's Blog, page 135

February 17, 2021

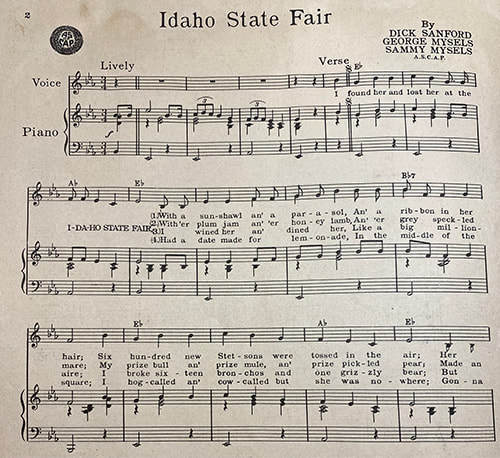

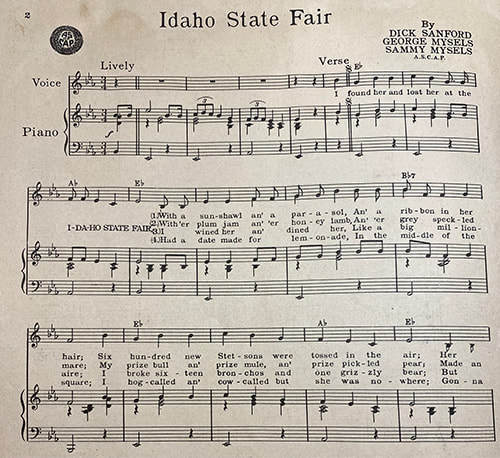

"I Found Her and I Lost Her..."

I grew up in Eastern Idaho where the Idaho State Fair is a big deal. In my formative years I heard the song “Idaho State Fair” enough for it to become an ear worm. It occurs to me that faithful readers of this blog might not all have had the chance to enjoy it. So, here’s a link to the song.

You probably didn’t hear this on top 40 stations in 1952—excluding KBLI of course—when it was recorded by Vaughn Monroe. That’s because it was the B side of the 45. The A side was “Lady Love,” which you likely didn’t hear either. As a public service I provide you with a link so you can determine for yourself why this might not have been a big hit. You’re welcome.

You probably didn’t hear this on top 40 stations in 1952—excluding KBLI of course—when it was recorded by Vaughn Monroe. That’s because it was the B side of the 45. The A side was “Lady Love,” which you likely didn’t hear either. As a public service I provide you with a link so you can determine for yourself why this might not have been a big hit. You’re welcome.

Published on February 17, 2021 04:00

February 16, 2021

The Boise Gnaws its Banks

Idaho experienced a long wet winter in 2016-2017, which resulted in flooding along many rivers. It did considerable damage to parks and Boise’s famous Greenbelt.

In 1928 the story was somewhat the same when the Statesman ran a piece about the raging Boise and a successful effort to keep damage at Julia Davis Park to a minimum.

“The angry river, gnawing at the banks skirting Julia Davis park was foiled of its prey, the projecting point near the tennis courts, by an all night battle of the street department, said Harry K. Fritchman, chairman of the park board…”

“The point in question was “made” ground, manufactured from tin cans, cracker boxes, decaying automobiles, street litter and cigaret (sic) cartons, said Fritchman. When the river started to work on it, this material gave way like butter under a hot knife—until the street department commenced to pile rocks along the banks, stopping the flow.”

I was struck by the description of the river bank and the trash of which it was comprised. Want to go for a swim there? Eager to fry a trout plucked from the river’s waters?

One of the purposes of studying history is to better appreciate how far we have come. The Boise River was once little more than a sewer. It was so difficult to access that many residents of the city never even saw it.

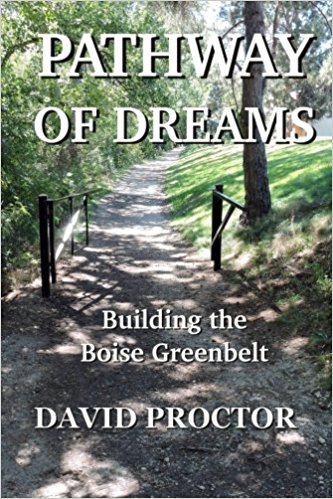

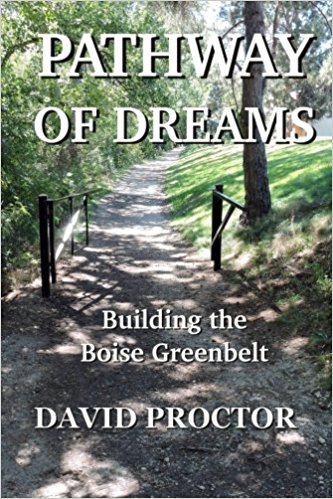

To learn more about the way the river was, and about its remarkable transformation into a Boise icon you can do no better than read Pathway of Dreams, Building the Boise Greenbelt , by the late David Proctor.

In 1928 the story was somewhat the same when the Statesman ran a piece about the raging Boise and a successful effort to keep damage at Julia Davis Park to a minimum.

“The angry river, gnawing at the banks skirting Julia Davis park was foiled of its prey, the projecting point near the tennis courts, by an all night battle of the street department, said Harry K. Fritchman, chairman of the park board…”

“The point in question was “made” ground, manufactured from tin cans, cracker boxes, decaying automobiles, street litter and cigaret (sic) cartons, said Fritchman. When the river started to work on it, this material gave way like butter under a hot knife—until the street department commenced to pile rocks along the banks, stopping the flow.”

I was struck by the description of the river bank and the trash of which it was comprised. Want to go for a swim there? Eager to fry a trout plucked from the river’s waters?

One of the purposes of studying history is to better appreciate how far we have come. The Boise River was once little more than a sewer. It was so difficult to access that many residents of the city never even saw it.

To learn more about the way the river was, and about its remarkable transformation into a Boise icon you can do no better than read Pathway of Dreams, Building the Boise Greenbelt , by the late David Proctor.

Published on February 16, 2021 04:00

February 15, 2021

Look Out!

This moss-covered old tree doesn’t look like much, but look closer. Maybe a treehouse some kid tacked together back in the dark ages? Staff at Heyburn State Park, where this tree is located, learned what it was at a Civilian Conservation Core (CCC) reunion a few years ago. It was a fire lookout. Unlike more formal lookouts in forests today, people didn’t spend a lot of time in this one. It was just a simple platform where someone could stand and take a regular look around for smoke after climbing up the tree.

Published on February 15, 2021 04:00

February 14, 2021

The Governor's House

It’s ephemera month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

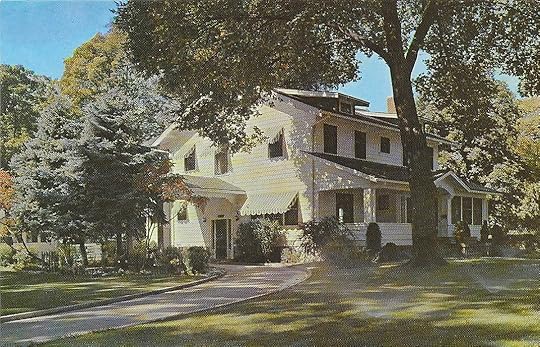

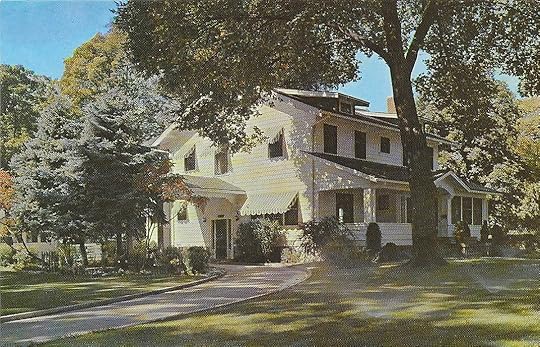

Today’s piece is a picture postcard of the Idaho governor’s residence.

The Pierce House was built in 1914 as a wedding present for the bride of Walter E. Pierce. Pierce had come to Boise in 1890 with ambitions to be instrumental in the building of a city. He was a young developer itching to ply his trade in the West. He probably picked Boise because it was about to become the capitol city of the country’s newest state.

With his partners, Lindley H. Cox and John M. Haines, doing business as W.E. Pierce and Company, he developed most of the North End’s subdivisions and platted others along State Street and in the East End. He was at one time the owner of Boise’s Natatorium and was a principle in the Boise & Interurban. Pierce was also instrumental in the development of the Hotel Boise, today known as the Hoff Building.

But this is about Pierce House, which served as the Governor’s House from 1947 to 1989. Built for $11,000 in 1914, it was sold it to the State of Idaho by a subsequent owner in 1947 for $25,000. It needed some major upgrades, including a new heating system.

Having a residence for a governor at all was novel for Idaho. Governors lived in their own homes during most of Idaho’s early history. If they didn’t already live in Boise, finding housing was sometimes difficult. C.A. Bottleson, a newspaper publisher from Arco, lived in the Owyhee Hotel during his first term and at the Hotel Boise (thank you Walter Pierce) during his second term. His successor, Arnold Williams, lived with his wife in a remodeled garage while serving as governor.

C.A. Robbins was the first Idaho governor to take up residence at 21st and Irene. The Robert E. Smylie family moved in next, calling the place home for three terms. When the Samuelsons moved in, Ruby Samuelson took it on as a project to equip the house with the necessities for hosting state dinners, this in spite of the fact that hosting much more than a family dinner was a challenge in the home. She raised funds for the purchase of china, crystal, sliver, and other permanent furnishings for the Governor’s House, much of it featuring the state seal. Mrs. Samuelson raised more than $4,000 for that purpose.

Having a nice set of dinnerware didn’t make the house much more useable for state functions in the opinion of Carol Andrus, the next first lady to live there. It was still small, and as Mrs. Andrus said, “If you plug two teapots into one plug-in in the kitchen, you blow a fuse.”

When Andrus was appointed Secretary of the Interior by President Jimmy Carter in 1977—the first Idahoan to hold a cabinet position—John and Lola Evans moved into the Pierce House. They were the last governor and first lady to occupy it. Andrus was elected governor again and began serving the third of his four terms in 1987. He and Carol were not interested in moving back into the Pierce House, and it was sold in 1989.

Though J.R. Simplot donated his grand house on the hill overlooking Boise in 2004 for use as the governor’s mansion, it had a lot of issues that precluded that use. It was given back to the Simplot family in 2016 and soon after demolished.

Providing Idaho’s governor with an official residence has not been a burning issue for many years.

Today’s piece is a picture postcard of the Idaho governor’s residence.

The Pierce House was built in 1914 as a wedding present for the bride of Walter E. Pierce. Pierce had come to Boise in 1890 with ambitions to be instrumental in the building of a city. He was a young developer itching to ply his trade in the West. He probably picked Boise because it was about to become the capitol city of the country’s newest state.

With his partners, Lindley H. Cox and John M. Haines, doing business as W.E. Pierce and Company, he developed most of the North End’s subdivisions and platted others along State Street and in the East End. He was at one time the owner of Boise’s Natatorium and was a principle in the Boise & Interurban. Pierce was also instrumental in the development of the Hotel Boise, today known as the Hoff Building.

But this is about Pierce House, which served as the Governor’s House from 1947 to 1989. Built for $11,000 in 1914, it was sold it to the State of Idaho by a subsequent owner in 1947 for $25,000. It needed some major upgrades, including a new heating system.

Having a residence for a governor at all was novel for Idaho. Governors lived in their own homes during most of Idaho’s early history. If they didn’t already live in Boise, finding housing was sometimes difficult. C.A. Bottleson, a newspaper publisher from Arco, lived in the Owyhee Hotel during his first term and at the Hotel Boise (thank you Walter Pierce) during his second term. His successor, Arnold Williams, lived with his wife in a remodeled garage while serving as governor.

C.A. Robbins was the first Idaho governor to take up residence at 21st and Irene. The Robert E. Smylie family moved in next, calling the place home for three terms. When the Samuelsons moved in, Ruby Samuelson took it on as a project to equip the house with the necessities for hosting state dinners, this in spite of the fact that hosting much more than a family dinner was a challenge in the home. She raised funds for the purchase of china, crystal, sliver, and other permanent furnishings for the Governor’s House, much of it featuring the state seal. Mrs. Samuelson raised more than $4,000 for that purpose.

Having a nice set of dinnerware didn’t make the house much more useable for state functions in the opinion of Carol Andrus, the next first lady to live there. It was still small, and as Mrs. Andrus said, “If you plug two teapots into one plug-in in the kitchen, you blow a fuse.”

When Andrus was appointed Secretary of the Interior by President Jimmy Carter in 1977—the first Idahoan to hold a cabinet position—John and Lola Evans moved into the Pierce House. They were the last governor and first lady to occupy it. Andrus was elected governor again and began serving the third of his four terms in 1987. He and Carol were not interested in moving back into the Pierce House, and it was sold in 1989.

Though J.R. Simplot donated his grand house on the hill overlooking Boise in 2004 for use as the governor’s mansion, it had a lot of issues that precluded that use. It was given back to the Simplot family in 2016 and soon after demolished.

Providing Idaho’s governor with an official residence has not been a burning issue for many years.

Published on February 14, 2021 04:00

February 13, 2021

Idaho Pronounciations

It’s Lazy to say Boyzee. Yeah, I didn’t come up with that one. The point is, if you don’t pronounce a place’s name like the natives, you’re going to out yourself as someone not from around here. The preferred pronunciation for Idaho’s capital city is Boysee, though residents aren’t all that picky about it.

In nearby Garden City there’s a street called Chinden. Locals argue over the pronunciation, some insisting on “Shinden.” It’s a contraction for Chinese Gardens, so you decide.

Mackey is probably the town name in Idaho that throws most people off. It is pronounced "Mackie" with the accent on the first syllable.

Basalt is pronounced bəˈsôlt, with the accent on salt, if you’re a geologist. But if you’re from Basalt, Idaho, you probably pronounce it bay salt.

You might think Dubois should be pronounced Dew Bwah, as Blanche did in that Tennessee Williams play. Nope. Dew Boys with a soft s. That’s the way Sen. Fred T. Dubois, for whom it was named, pronounced it.

And finally, what about Pahsimeroi? Uh, I’m not having that argument.

In nearby Garden City there’s a street called Chinden. Locals argue over the pronunciation, some insisting on “Shinden.” It’s a contraction for Chinese Gardens, so you decide.

Mackey is probably the town name in Idaho that throws most people off. It is pronounced "Mackie" with the accent on the first syllable.

Basalt is pronounced bəˈsôlt, with the accent on salt, if you’re a geologist. But if you’re from Basalt, Idaho, you probably pronounce it bay salt.

You might think Dubois should be pronounced Dew Bwah, as Blanche did in that Tennessee Williams play. Nope. Dew Boys with a soft s. That’s the way Sen. Fred T. Dubois, for whom it was named, pronounced it.

And finally, what about Pahsimeroi? Uh, I’m not having that argument.

Published on February 13, 2021 04:00

February 12, 2021

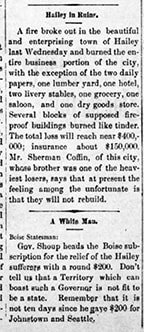

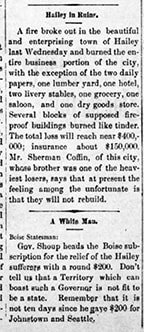

Hot in Hailey

With today’s 24-hour news cycle we sometimes reel from disaster to disaster. News did not travel so fast in the summer of 1889, but residents of Idaho must have felt a little whip-sawed nevertheless. First in the news, on May 31, there was the Johnstown Flood in Pennsylvania, sweeping more than 2,200 people to their deaths. Then came the Great Seattle Fire on June 6, burning 25 square blocks of that city to the ground. Then, on July 2, Idaho got its own disaster.

The fire alarm started ringing in Hailey at 1:30 in the morning and didn’t stop until the sun was well up. A fire had started in the Nevada Bakery. As the fire spread, townspeople saw that a row of frame buildings between the bakery and the Merchant’s Hotel was going to be lost. The hotel, though, was made of brick, so there the fire would stop. Or so they hoped. The flames barely slowed, engulfing the hotel. Other buildings in town were called fireproof, until they were turned to tinder.

Within a couple of hours most of the businesses in Hailey were little more than ash. About four square blocks burned. Remarkably, the conflagration did not touch any residence, and it left the offices of two newspapers standing, as if it wanted nothing more than publicity.

The fire alarm started ringing in Hailey at 1:30 in the morning and didn’t stop until the sun was well up. A fire had started in the Nevada Bakery. As the fire spread, townspeople saw that a row of frame buildings between the bakery and the Merchant’s Hotel was going to be lost. The hotel, though, was made of brick, so there the fire would stop. Or so they hoped. The flames barely slowed, engulfing the hotel. Other buildings in town were called fireproof, until they were turned to tinder.

Within a couple of hours most of the businesses in Hailey were little more than ash. About four square blocks burned. Remarkably, the conflagration did not touch any residence, and it left the offices of two newspapers standing, as if it wanted nothing more than publicity.

Published on February 12, 2021 04:00

February 11, 2021

Heise Hot Springs

It’s ephemera month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

Today’s post was inspired by a postcard from Heise Hot Springs.

Richard Camor Heise arrived in Idaho around 1890, the year Idaho became a state. He was a German immigrant who had fought in the Civil War and Indian skirmishes while in the army.

Heise was working as a salesman in about 1894 when he heard about some natural hot springs not far from Eagle Rock (now Idaho Falls). They were allegedly good for whatever ailed one. Heise had severe rheumatism, so he decided to try the mineral waters. They brought him some relief, so he homesteaded in the area and began to develop the hot springs into a spa.

Even before a bridge was built to make the area more accessible his little resort became popular. Heise developed a series of pipes and pools where the water temperature could be adjusted to the needs of his clientele.

Heise passed away on Halloween, 1921, but his hot springs spa continues to this day.

Heise Hot Springs post card. The photo was likely taken before 1910.

Heise Hot Springs post card. The photo was likely taken before 1910.

Today’s post was inspired by a postcard from Heise Hot Springs.

Richard Camor Heise arrived in Idaho around 1890, the year Idaho became a state. He was a German immigrant who had fought in the Civil War and Indian skirmishes while in the army.

Heise was working as a salesman in about 1894 when he heard about some natural hot springs not far from Eagle Rock (now Idaho Falls). They were allegedly good for whatever ailed one. Heise had severe rheumatism, so he decided to try the mineral waters. They brought him some relief, so he homesteaded in the area and began to develop the hot springs into a spa.

Even before a bridge was built to make the area more accessible his little resort became popular. Heise developed a series of pipes and pools where the water temperature could be adjusted to the needs of his clientele.

Heise passed away on Halloween, 1921, but his hot springs spa continues to this day.

Heise Hot Springs post card. The photo was likely taken before 1910.

Heise Hot Springs post card. The photo was likely taken before 1910.

Published on February 11, 2021 04:00

February 10, 2021

Farragut Sprouts

The next time you feel like grumbling about that road project that seems to go on forever, remember Farragut State Park. More appropriately, remember the Farragut Naval Training Station that was built on the shores of Lake Pend Oreille to train Navy recruits for World War II.

Building an all new naval training station was a tremendous effort. It had to be done fast, because the war was suddenly on. This photograph shows construction at Camp Waldron barracks in 1942. Construction at Farragut Naval Training Station began in March, and recruits started training in September of THE SAME YEAR. The final construction budget was $57 million. Recruits, called “boots,” would train there for only 26 months. Even so, 293,380 men received their basic training at Farragut.

Today, Farragut State Park remembers those naval training station days with a series of exhibits in the original Navy brig.

Building an all new naval training station was a tremendous effort. It had to be done fast, because the war was suddenly on. This photograph shows construction at Camp Waldron barracks in 1942. Construction at Farragut Naval Training Station began in March, and recruits started training in September of THE SAME YEAR. The final construction budget was $57 million. Recruits, called “boots,” would train there for only 26 months. Even so, 293,380 men received their basic training at Farragut.

Today, Farragut State Park remembers those naval training station days with a series of exhibits in the original Navy brig.

Published on February 10, 2021 04:00

February 9, 2021

A Very Ghosty Ghost Town

There are lots of ghost towns scattered around Idaho. Today's story is about a town that came and went so fast, it probably doesn't even rate a proper ghost.

Alturas County was enormous. When created in 1864, it included practically all the land between the Snake and Salmon rivers in the south-central part of the state.

Now, when you create a new county, you always like to name a county seat. About the only thing you really need for a county seat is a town. But Alturas County, with all those thousands of acres, didn't have a real town, so the legislature invented one. They called it Esmeralda, and it was located on a beautiful plateau near the South Fork of the Boise River, about a mile below what is now Featherville.

Esmeralda was never more than a handful of slap-dash cabins occupied by some early-day prospectors. Its moment of fame was little more than a moment. Two months after it was named the county seat of Alturas County, the county commissioners moved their operation to the new town of Rocky Bar, where gold had just been discovered. The commissioners and prospectors left Esmeralda, and the town just disappeared.

So did the county, eventually. Alturas County existed for over thirty years, but increased population within its boundaries prompted the legislature to split it up into smaller counties in 1896. Smaller, but not small counties. Blaine, Camas, Gooding, Lincoln, Jerome, Elmore, and Minidoka counties were all carved from Alturas.

The map, courtesy of the Idaho Genealogical Society, shows the original boundaries of Alturus County and the counties that split off from it.

Alturas County was enormous. When created in 1864, it included practically all the land between the Snake and Salmon rivers in the south-central part of the state.

Now, when you create a new county, you always like to name a county seat. About the only thing you really need for a county seat is a town. But Alturas County, with all those thousands of acres, didn't have a real town, so the legislature invented one. They called it Esmeralda, and it was located on a beautiful plateau near the South Fork of the Boise River, about a mile below what is now Featherville.

Esmeralda was never more than a handful of slap-dash cabins occupied by some early-day prospectors. Its moment of fame was little more than a moment. Two months after it was named the county seat of Alturas County, the county commissioners moved their operation to the new town of Rocky Bar, where gold had just been discovered. The commissioners and prospectors left Esmeralda, and the town just disappeared.

So did the county, eventually. Alturas County existed for over thirty years, but increased population within its boundaries prompted the legislature to split it up into smaller counties in 1896. Smaller, but not small counties. Blaine, Camas, Gooding, Lincoln, Jerome, Elmore, and Minidoka counties were all carved from Alturas.

The map, courtesy of the Idaho Genealogical Society, shows the original boundaries of Alturus County and the counties that split off from it.

Published on February 09, 2021 04:00

February 8, 2021

Signed, The Guv

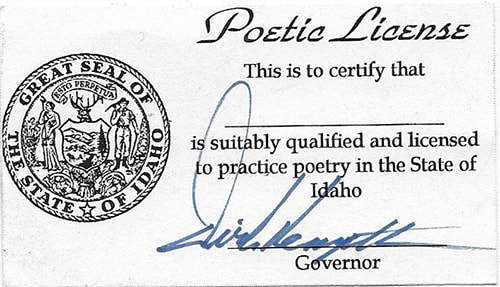

It’s Ephemera Month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

A governor’s signature on a bill can be one of the most important things they do. That same signature on a proclamation can have some level of importance, or it might be largely ceremonial. Today’s post is about the signatures that you may not have known that governors do.

There are collectors of gubernatorial signatures lurking around out there. I was one of them for a while. I collected a few from sitting governors when I came across them while working for the State of Idaho. Those were mostly proclamations and minor correspondence. Since I had a few of those, I decided to see if I could collect gubernatorial signatures from past governors.

It’s easy to start a hobby like that these days thanks to eBay. You can create a search bot that alerts you whenever the words governor, Idaho, and signature or autograph pop up. I collected a few signatures that were created during the course of business, such as a canceled check from George Shoup, Idaho’s last territorial governor and first state governor. Mostly, though, the signatures existed because someone wrote to the sitting governor and requested one.

Most governors answered requests like that by signing a blank card or even the outside of an envelope that was returned to the requestor. Here are a few samples.

Governor Henry Clarence Baldridge simply signed the front of an official envelope.

Governor Henry Clarence Baldridge simply signed the front of an official envelope.

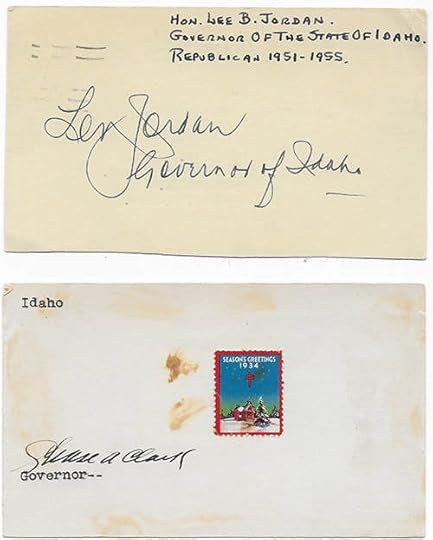

Governors Len B. Jordan and Chase Clark went for simplicity.

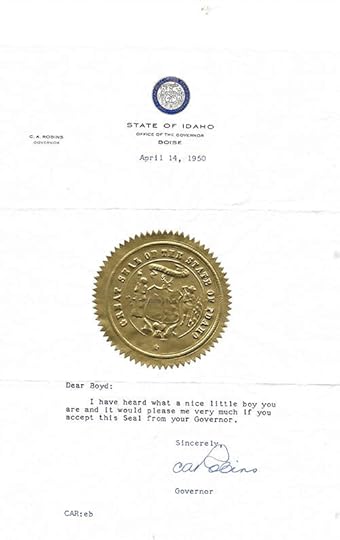

Governors Len B. Jordan and Chase Clark went for simplicity.  Governor C.A. Robbins tricked up his signature with a state seal and even wrote a nice little note on this one.

Governor C.A. Robbins tricked up his signature with a state seal and even wrote a nice little note on this one.

Robbins eventually created a souvenir for those requesting his autograph. Above is a special reply in the shape of a potato with room for the signature on the back. On the inside there were three scenes of Idaho.

Robbins eventually created a souvenir for those requesting his autograph. Above is a special reply in the shape of a potato with room for the signature on the back. On the inside there were three scenes of Idaho.

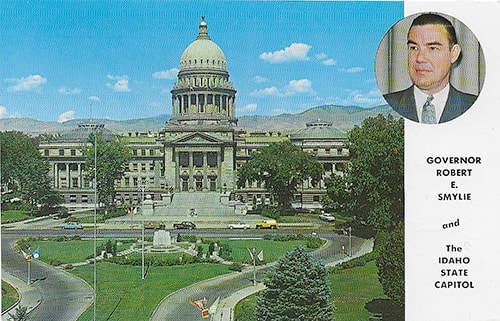

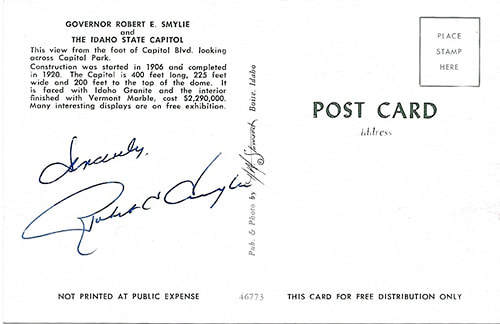

Governor Robert E. Smylie sent a postcard with his photo and a picture of the statehouse.

Governor Robert E. Smylie sent a postcard with his photo and a picture of the statehouse. The address side of the card included a blurb about the statehouse, Governor Smylie’s signature, and a note that the postcards weren’t printed at public expense. I don’t know who paid for the printing.

The address side of the card included a blurb about the statehouse, Governor Smylie’s signature, and a note that the postcards weren’t printed at public expense. I don’t know who paid for the printing.

This final example is the size of a business card. It’s my favorite. I was going to spend the day at the Elk City elementary school teaching the students about poetry. It was something Tom Trusky had cooked up for a National Endowment for the Arts grant. I thought it would be fun to give the kids each a “poetic license” signed by the governor. Much of a governor’s correspondence is actually signed by a machine that does a beautiful job of replicating a signature. I had arranged ahead of time to have his staff run the 50 cards through the machine. When I got to the office, we found that the machine was out of order. I was headed for Elk City the next day. Since the machine was down, I’d have to just forget the idea.

This final example is the size of a business card. It’s my favorite. I was going to spend the day at the Elk City elementary school teaching the students about poetry. It was something Tom Trusky had cooked up for a National Endowment for the Arts grant. I thought it would be fun to give the kids each a “poetic license” signed by the governor. Much of a governor’s correspondence is actually signed by a machine that does a beautiful job of replicating a signature. I had arranged ahead of time to have his staff run the 50 cards through the machine. When I got to the office, we found that the machine was out of order. I was headed for Elk City the next day. Since the machine was down, I’d have to just forget the idea.One of the governor’s aides excused himself for a moment. When he came back, he led me into the governor’s office. Dirk Kempthorne had agreed to sign each one individually while I waited. I was surprised that he took the time to do that for me and for the kids in Elk City.

Published on February 08, 2021 04:00