Rick Just's Blog, page 134

February 27, 2021

The Tallest Mountain in Idaho. Not.

It’s ephemera month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

The top postcard depicts Idaho’s highest point. I’m not sure when the postcard was produced, but I know it was before 1934. That’s because the card shows Hyndman Peak. That peak, named after the superintendent of the Silver King Mine in Sawtooth City, Major William Hyndman, was thought to be Idaho’s highest mountain at 12,009 feet, until the U.S. Geological Survey found that an unnamed mountain in the Lost River Range was higher. USGS named it Mt. Borah in honor of then US Senator William E. Borah. The second postcard gets it right. Naming a mountain for a living person isn’t something that would be done today, even though Borah had already served as a senator from Idaho for 27 years. Mount Borah tops Hyndman Peak by more than 600 feet at 12, 662 feet.

Borah lived long enough after the mountain was named for him to run for a presidential nomination a couple of times before he died in office in 1940.

Published on February 27, 2021 04:00

February 26, 2021

The Blackfoot Sugar Factory

It’s ephemera month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

I’ve written about the Blackfoot Sugar Factory before, but didn’t remember that I had this old postcard. This picture was taken sometime before 1937, going by the postmark. You’re looking more or less west from what is now US 91. At this time the road was dirt. The highway was a major route running from Long Beach to Alberta between 1947 and 1965. Today, although several segments of it still exist, including the one through Blackfoot, it has largely been replaced by I-15.

With the powerlines and trees in the way this doesn’t show much detail of the building, but there is a lot going on. The roadster parked in front looks like a Model T, perhaps dating the photo to sometime in the 20s. There’s a coupe of some kind parked under the trees with a couple of horses tied up nearby. To the left of the photo “under” the smokestack, is one of the staff houses. A string of five of those houses are still there being used as residences. The sugar factory itself is long gone.

One of the more interesting items in the picture is the ramp you can see leading up to the right and around the back of the building. The 1943 watercolor below this picture shows the ramp from a different angle, looking more toward the south. Wagons and train cars moved up those ramps to a beet dumping site behind the factory.

Pre-1937 photo of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory.

Pre-1937 photo of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory.  This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory was painted by my cousin Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory was painted by my cousin Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

I’ve written about the Blackfoot Sugar Factory before, but didn’t remember that I had this old postcard. This picture was taken sometime before 1937, going by the postmark. You’re looking more or less west from what is now US 91. At this time the road was dirt. The highway was a major route running from Long Beach to Alberta between 1947 and 1965. Today, although several segments of it still exist, including the one through Blackfoot, it has largely been replaced by I-15.

With the powerlines and trees in the way this doesn’t show much detail of the building, but there is a lot going on. The roadster parked in front looks like a Model T, perhaps dating the photo to sometime in the 20s. There’s a coupe of some kind parked under the trees with a couple of horses tied up nearby. To the left of the photo “under” the smokestack, is one of the staff houses. A string of five of those houses are still there being used as residences. The sugar factory itself is long gone.

One of the more interesting items in the picture is the ramp you can see leading up to the right and around the back of the building. The 1943 watercolor below this picture shows the ramp from a different angle, looking more toward the south. Wagons and train cars moved up those ramps to a beet dumping site behind the factory.

Pre-1937 photo of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory.

Pre-1937 photo of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory.  This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory was painted by my cousin Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot Sugar Factory was painted by my cousin Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

Published on February 26, 2021 04:00

February 25, 2021

Idaho's Film Sleuth

This is a photo of Tom Trusky, who was a professor at BSU who happened to be a good friend of mine. Tom loved to find little treasures that were lost to history. He discovered that there was once a movie studio on the shores of Priest Lake run by a woman named Nell Shipman. Little was known about her, and the films she produced there had mostly been lost to time. Tom decided he’d find them. He had no idea how difficult that would be. He searched archives in Canada, the United Kingdom, and in Russia. He began finding them, one after another, until he found every single one of her films.

On top of that, he found her unpublished autobiography and convinced BSU to publish it under the title The Silent Screen and My Talking Heart .

Tom Trusky wrote the following about Nell in 2008: “In the summer of 1922, Nell Shipman Productions moved from Spokane, Washington to its final residence, Priest Lake, in the Panhandle of north Idaho. There, the company would complete shooting of what historians and silent film fans term Shipman’s magnum opus, The Grub-Stake (1922), and four noteworthy two-reel films in a series titled The Little Dramas of the Big Places (1924). Although Shipman and her crew could not have known it, this was sundown for the democratic, “Indie,” one-girl-do-it-all days of cinema. Dawn of the next day, the studio system and male movie moguls would define for decades what Hollywood meant, prior to the advent of television, Gloria Steinem, Sundance, satellite feeds, and on-line downloads.”

Nell Shipman was the screenwriter, director, star, and stunt woman in her movies. They featured strong women more likely to save men from danger than the other way around. Her pioneering included what by today’s standards would be a PG-rated nude scene of her showering beneath a waterfall. The movie was hyped with the slogan, “Is the nude, rude?” Shipman Point in Priest Lake State Park is named for this early film pioneer.

Because of the scholarship of Professor Trusky, who passed away in 2009, Boise State University is the home to a digital collection of Shipman photographs and other memorabilia. Many of her films are available online. Revival of interest in Shipman resulted in an award-winning 2015 documentary called Girl From God’s Country, by Boise filmmaker Karen Day.

On top of that, he found her unpublished autobiography and convinced BSU to publish it under the title The Silent Screen and My Talking Heart .

Tom Trusky wrote the following about Nell in 2008: “In the summer of 1922, Nell Shipman Productions moved from Spokane, Washington to its final residence, Priest Lake, in the Panhandle of north Idaho. There, the company would complete shooting of what historians and silent film fans term Shipman’s magnum opus, The Grub-Stake (1922), and four noteworthy two-reel films in a series titled The Little Dramas of the Big Places (1924). Although Shipman and her crew could not have known it, this was sundown for the democratic, “Indie,” one-girl-do-it-all days of cinema. Dawn of the next day, the studio system and male movie moguls would define for decades what Hollywood meant, prior to the advent of television, Gloria Steinem, Sundance, satellite feeds, and on-line downloads.”

Nell Shipman was the screenwriter, director, star, and stunt woman in her movies. They featured strong women more likely to save men from danger than the other way around. Her pioneering included what by today’s standards would be a PG-rated nude scene of her showering beneath a waterfall. The movie was hyped with the slogan, “Is the nude, rude?” Shipman Point in Priest Lake State Park is named for this early film pioneer.

Because of the scholarship of Professor Trusky, who passed away in 2009, Boise State University is the home to a digital collection of Shipman photographs and other memorabilia. Many of her films are available online. Revival of interest in Shipman resulted in an award-winning 2015 documentary called Girl From God’s Country, by Boise filmmaker Karen Day.

Published on February 25, 2021 04:00

February 24, 2021

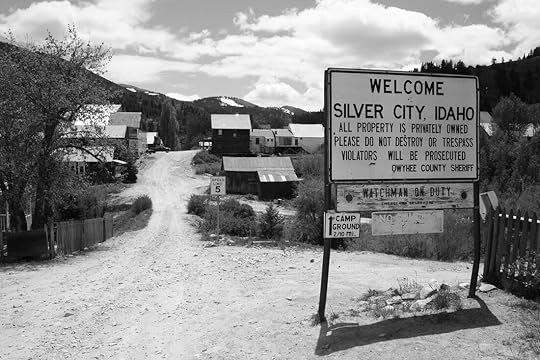

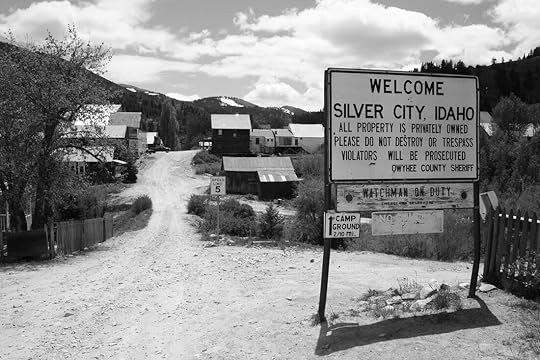

The Underground War

You've heard of underground newspapers, and the underground economy...but have you ever heard of an underground war? Idaho had one, once:

In 1868 there were two mines near Silver City that were located just 75 feet apart, the Ida Elmore and the Golden Chariot. In fact, on claim maps, the two mines actually overlapped.

To avoid trouble, the mining companies agreed to block off an area of unmined ore between them as a neutral zone. Neither company would mine there.

Ah, but that ore was tempting! Both companies cheated and began mining toward each other.

On March 11, 1868, Idaho's underground war began deep within the mines. Miners on both sides laid down their picks, put out their lights, and began shooting at each other in the dark. They tried to drown each other, too, in those tunnels 300 feet beneath the surface. And they fought with jets of steam and hot water. The battle went on day and night with shotguns, rifles,

handguns--even hand grenades.

It's surprising how few casualties there were. By some accounts 100 men fired several thousand bullets at each other in the dark tunnels. No doubt some accounts were exaggerated. Mine timbers nine inches thick were nearly cut in half by the gunfire. And yet, only three men were killed in the mining war.

Troops were finally sent to stop the war after it had gone along in fits and starts for about three weeks. The owners of the two mines worked out their differences and went about the business of getting rich. The disputed Silver City vein eventually yielded seven million dollars worth of ore.

In 1868 there were two mines near Silver City that were located just 75 feet apart, the Ida Elmore and the Golden Chariot. In fact, on claim maps, the two mines actually overlapped.

To avoid trouble, the mining companies agreed to block off an area of unmined ore between them as a neutral zone. Neither company would mine there.

Ah, but that ore was tempting! Both companies cheated and began mining toward each other.

On March 11, 1868, Idaho's underground war began deep within the mines. Miners on both sides laid down their picks, put out their lights, and began shooting at each other in the dark. They tried to drown each other, too, in those tunnels 300 feet beneath the surface. And they fought with jets of steam and hot water. The battle went on day and night with shotguns, rifles,

handguns--even hand grenades.

It's surprising how few casualties there were. By some accounts 100 men fired several thousand bullets at each other in the dark tunnels. No doubt some accounts were exaggerated. Mine timbers nine inches thick were nearly cut in half by the gunfire. And yet, only three men were killed in the mining war.

Troops were finally sent to stop the war after it had gone along in fits and starts for about three weeks. The owners of the two mines worked out their differences and went about the business of getting rich. The disputed Silver City vein eventually yielded seven million dollars worth of ore.

Published on February 24, 2021 04:00

February 23, 2021

Idaho, the Song

When you hear the word Idaho, the first thing you think of is jazz, right? Right?

Okay, maybe not. But there is a pretty great song called “Idaho” that is a fairly well-known jazz piece. It was written by Jesse Stone who, as far as I know, had no connection to Idaho.

“Idaho” was originally recorded by Alvino Rey and his orchestra in 1941. The next year, Benny Goodman had a version that hit number 4 on the pop charts. Here’s a link to that one. You’ll probably have to endure a few seconds of commercial before you get to it. Oh, and don’t expect the singing to start right away. Guy Lombardo sold 4 million copies of his version.

The song is a snappy little number. Even so, I was surprised to learn that Stone was also the writer behind the decidedly rock, “Shake, Rattle, and Roll.”

The cover for the sheet music of “Idaho.” Potatoes aren’t mentioned in the song, but they made the cover!

The cover for the sheet music of “Idaho.” Potatoes aren’t mentioned in the song, but they made the cover!

Okay, maybe not. But there is a pretty great song called “Idaho” that is a fairly well-known jazz piece. It was written by Jesse Stone who, as far as I know, had no connection to Idaho.

“Idaho” was originally recorded by Alvino Rey and his orchestra in 1941. The next year, Benny Goodman had a version that hit number 4 on the pop charts. Here’s a link to that one. You’ll probably have to endure a few seconds of commercial before you get to it. Oh, and don’t expect the singing to start right away. Guy Lombardo sold 4 million copies of his version.

The song is a snappy little number. Even so, I was surprised to learn that Stone was also the writer behind the decidedly rock, “Shake, Rattle, and Roll.”

The cover for the sheet music of “Idaho.” Potatoes aren’t mentioned in the song, but they made the cover!

The cover for the sheet music of “Idaho.” Potatoes aren’t mentioned in the song, but they made the cover!

Published on February 23, 2021 04:00

February 22, 2021

A Mysterious Disappearance

Walter S. Campbell helped shape the Boise we know today. He was the architect for the Adelman Building, the Central Fire Station, the Telephone Building, and not least the Idanha Hotel. But it was Boise’s first Federal Building, now known as the Borah Building, that may have brought his storied career to an end.

Campbell, who was from Scotland, studied architecture at the University of Edinburgh. He opened his Boise firm in 1889. It wasn’t long after, 1891, that talk began about building a $200,000 federal building in Boise. It would remain little more than talk for another ten years.

Meanwhile, Campbell began making his mark. His first major public building was Swanger Hall at the Albion Normal School. Designed in 1896 and completed the following year, it was a Queen Anne verging on classical style building that was the centerpiece of the campus until it burned in 1947.

Back in Boise, Campbell designed the Telephone Building, now the home of Main Street Bistro, at 609 W. Main. Built in about three months in 1900, the two-story building with its distinctive row of four rounded arch windows on the main floor is built from Boise sandstone and still retains the name TELEPHONE centered and carved in the stone above the second story. It was the Boise office American Bell Telephone Company.

The Idanha is Campbell’s best-known building. He visited every major hotel between Boise and New York City for inspiration, and it shows. The six-story brick and sandstone hotel was the tallest building in town when it went up in 1900, and it has been a beloved landmark ever since.

In September of 1901, Campbell’s firm began work on the new Federal Building in Boise. That it would use sandstone was no surprise. W. S. Campbell owned a sandstone quarry near Idaho City. During the course of construction, a 10,000-pound block of stone was brought down for the federal building steps.

While that building was going up, Campbell’s firm got the contract for the Adelman Building at 624 West Idaho. Built in 1902, Its corner turret reminiscent of those on the Idanha, the building houses Dharma Sushi & Thai today.

The Central Fire Station at 522 W. Idaho Street was next on Campbells list. Built in 1903, the Central Fire Station was Boise’s first big move away from a volunteer fire department. Today, the Melting Pot restaurant occupies part of the building. For a decade CSHQA architects, who trace their beginning back to Campbell, called it home.

Ah, but the Federal Building. Things were not going well for the project. Contractors were clamoring for their pay and the project was months, then years behind.

Following Campbell’s career in the papers of the time his name shows up on February 26, 1904 when his firm received a third-place prize in a design competition for the new Carnegie Library. Then on March 22 of that same year, the Capital News ran a story that began, “W.S. Campbell, the architect whose disappearance has caused considerable alarm, has been located in Scotland.”

The paper went on: “No word… has been received from him and no reason is advanced by his family or friends as to why he should so suddenly disappear. When he left Boise several weeks ago, he stated that he was going to Omaha, St. Louis and Chicago to see about material for the federal building.”

Campbell was a big name in Boise, and his disappearance was met with puzzlement. Some thought he had met with foul play or had fallen ill.

The paper noted that his “various accounts” were “all straight.” Maybe. But H.A. Riddenbaugh, who took over the contract for the federal building, sued Campbell for some $7,000, winning a judgment in the case.

The Capital News noted that there was “a rumor that his domestic affairs were not pleasant.” The article ended with the observation that intimate friends of Campbell thought he would never return to Boise.

But he did return to the city he clearly loved, though not in life. William S. Campbell died in British Columbia in 1930. He was interred at Morris Hill Cemetery. His wife, Minnie, died in 1962 and is buried at Dry Creek Cemetery.

Campbell’s reasons for disappearing for all those years are still open for speculation.

The Boise federal building in about 1906. Note the capitol dome under construction in the background. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The Boise federal building in about 1906. Note the capitol dome under construction in the background. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Campbell, who was from Scotland, studied architecture at the University of Edinburgh. He opened his Boise firm in 1889. It wasn’t long after, 1891, that talk began about building a $200,000 federal building in Boise. It would remain little more than talk for another ten years.

Meanwhile, Campbell began making his mark. His first major public building was Swanger Hall at the Albion Normal School. Designed in 1896 and completed the following year, it was a Queen Anne verging on classical style building that was the centerpiece of the campus until it burned in 1947.

Back in Boise, Campbell designed the Telephone Building, now the home of Main Street Bistro, at 609 W. Main. Built in about three months in 1900, the two-story building with its distinctive row of four rounded arch windows on the main floor is built from Boise sandstone and still retains the name TELEPHONE centered and carved in the stone above the second story. It was the Boise office American Bell Telephone Company.

The Idanha is Campbell’s best-known building. He visited every major hotel between Boise and New York City for inspiration, and it shows. The six-story brick and sandstone hotel was the tallest building in town when it went up in 1900, and it has been a beloved landmark ever since.

In September of 1901, Campbell’s firm began work on the new Federal Building in Boise. That it would use sandstone was no surprise. W. S. Campbell owned a sandstone quarry near Idaho City. During the course of construction, a 10,000-pound block of stone was brought down for the federal building steps.

While that building was going up, Campbell’s firm got the contract for the Adelman Building at 624 West Idaho. Built in 1902, Its corner turret reminiscent of those on the Idanha, the building houses Dharma Sushi & Thai today.

The Central Fire Station at 522 W. Idaho Street was next on Campbells list. Built in 1903, the Central Fire Station was Boise’s first big move away from a volunteer fire department. Today, the Melting Pot restaurant occupies part of the building. For a decade CSHQA architects, who trace their beginning back to Campbell, called it home.

Ah, but the Federal Building. Things were not going well for the project. Contractors were clamoring for their pay and the project was months, then years behind.

Following Campbell’s career in the papers of the time his name shows up on February 26, 1904 when his firm received a third-place prize in a design competition for the new Carnegie Library. Then on March 22 of that same year, the Capital News ran a story that began, “W.S. Campbell, the architect whose disappearance has caused considerable alarm, has been located in Scotland.”

The paper went on: “No word… has been received from him and no reason is advanced by his family or friends as to why he should so suddenly disappear. When he left Boise several weeks ago, he stated that he was going to Omaha, St. Louis and Chicago to see about material for the federal building.”

Campbell was a big name in Boise, and his disappearance was met with puzzlement. Some thought he had met with foul play or had fallen ill.

The paper noted that his “various accounts” were “all straight.” Maybe. But H.A. Riddenbaugh, who took over the contract for the federal building, sued Campbell for some $7,000, winning a judgment in the case.

The Capital News noted that there was “a rumor that his domestic affairs were not pleasant.” The article ended with the observation that intimate friends of Campbell thought he would never return to Boise.

But he did return to the city he clearly loved, though not in life. William S. Campbell died in British Columbia in 1930. He was interred at Morris Hill Cemetery. His wife, Minnie, died in 1962 and is buried at Dry Creek Cemetery.

Campbell’s reasons for disappearing for all those years are still open for speculation.

The Boise federal building in about 1906. Note the capitol dome under construction in the background. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The Boise federal building in about 1906. Note the capitol dome under construction in the background. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on February 22, 2021 05:01

February 21, 2021

The Thomas Brothers

Many people have important, but little known roles in Idaho history. Here are a couple of guys you’ve probably never heard of who had a positive impact on outdoor recreation in the state.

In 1918, the Thomas family, in the top picture, enjoys a camping trip at Billingsley Creek, near Hagerman. The two family members identified in this photograph are the children—Bob Thomas (on the left in the light colored stocking cap) and his brother Eldred on the right. Billingsley Creek would become a unit of Thousand Springs State Park 84 years later, in 2002. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Thomas brothers would serve the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation—Bob as an Idaho Park and Recreation Board member and Eldred as a member of the RV Advisory committee. In the lower picture Bob, who also served Idaho as a fish and game commissioner, is still wearing a stocking cap in this self-portrait at Farragut State Park around 2000.

In 1918, the Thomas family, in the top picture, enjoys a camping trip at Billingsley Creek, near Hagerman. The two family members identified in this photograph are the children—Bob Thomas (on the left in the light colored stocking cap) and his brother Eldred on the right. Billingsley Creek would become a unit of Thousand Springs State Park 84 years later, in 2002. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Thomas brothers would serve the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation—Bob as an Idaho Park and Recreation Board member and Eldred as a member of the RV Advisory committee. In the lower picture Bob, who also served Idaho as a fish and game commissioner, is still wearing a stocking cap in this self-portrait at Farragut State Park around 2000.

Published on February 21, 2021 04:00

February 20, 2021

DXing KSEI

It’s ephemera month at Speaking of Idaho. I’m writing a few little blurbs about some interesting ephemera I’ve collected over the years. Often there’s little or no historic value to the pieces, but each one tells a story.

This is an unused “verified reception” stamp from KSEI radio in Pocatello. During the 1920s and early 1930s it became a fad to collect these stamps from stations far away. Some collectors had stamp books in which they kept their prizes.

Listeners who heard a weak signal from a far-away station sent that station a card telling the details of what they heard, such as the subject of a newscast, what a commercial said, or what song was playing at the time. The stations would send back a card with a stamp on it verifying that the description matched their programing at that moment.

Some of the companies producing the stamps also sold them unused to collectors. This is one of those unused stamps, which I am donating to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation for their museum in Caldwell, which is housed in the old KFXD studios there. It isn’t yet open to the public, but we’ll keep you posted.

The reason this odd hobby existed is that atmospheric conditions at night make it possible for AM signals to travel great distances. The AM waves bounce off the ionosphere when darkness falls. If the receiver is also in the dark, the signals can be heard halfway across the globe.

Most AM stations don’t bother printing up stamps anymore, but the hobby still exists among shortwave enthusiasts. It’s called DXing. The D is for distance and the X is for unknown. There are magazines about it and online chat groups. DXers get all the relevant information to prove they heard the station, then send the station an email for confirmation.

Back in the late 60s, when I was working at KBLI in Blackfoot, I remember getting a DX card from someone in Japan who had heard the sign-off recording just as the sun was going down, the perfect time to catch a signal from a daytime only station.

This is an unused “verified reception” stamp from KSEI radio in Pocatello. During the 1920s and early 1930s it became a fad to collect these stamps from stations far away. Some collectors had stamp books in which they kept their prizes.

Listeners who heard a weak signal from a far-away station sent that station a card telling the details of what they heard, such as the subject of a newscast, what a commercial said, or what song was playing at the time. The stations would send back a card with a stamp on it verifying that the description matched their programing at that moment.

Some of the companies producing the stamps also sold them unused to collectors. This is one of those unused stamps, which I am donating to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation for their museum in Caldwell, which is housed in the old KFXD studios there. It isn’t yet open to the public, but we’ll keep you posted.

The reason this odd hobby existed is that atmospheric conditions at night make it possible for AM signals to travel great distances. The AM waves bounce off the ionosphere when darkness falls. If the receiver is also in the dark, the signals can be heard halfway across the globe.

Most AM stations don’t bother printing up stamps anymore, but the hobby still exists among shortwave enthusiasts. It’s called DXing. The D is for distance and the X is for unknown. There are magazines about it and online chat groups. DXers get all the relevant information to prove they heard the station, then send the station an email for confirmation.

Back in the late 60s, when I was working at KBLI in Blackfoot, I remember getting a DX card from someone in Japan who had heard the sign-off recording just as the sun was going down, the perfect time to catch a signal from a daytime only station.

Published on February 20, 2021 04:00

February 19, 2021

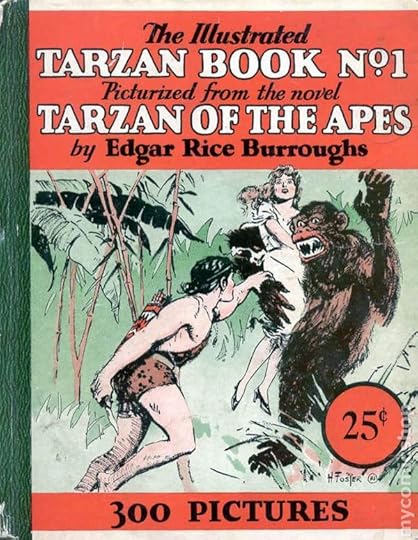

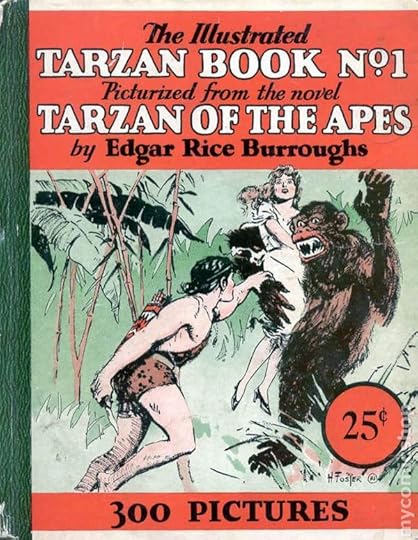

Tarzan of Idaho

Tarzan of the Apes. The setting for those stories was deepest, darkest Africa, but the author spent some of his early days in deepest, darkest... Pocatello.

Edgar Rice Burroughs came to the state in the mid 1890s. His brothers worked on a ranch their father had purchased near Yale, Idaho (which the brothers, Yale graduates, had convinced the postal service to name) and he got a job there, too, as a cowhand. But he didn’t stick with any job very long. Burroughs worked for a local dredge company for a while, then found himself unemployed.

With the help of his brother Harry, Edgar Rice Burroughs purchased a stationery and cigar store in Pocatello at 233 West Center Street in 1898. He also established a Pocatello delivery service, sometimes delivering newspapers himself from the back of a black horse named Crow. It turned out that Burroughs was not as successful at selling books as he would later become at writing them. He sold the failing Pocatello store a year after he bought it.

He tried ranching again. He worked for a dredge company again, this time in Minidoka. He lived in the Stanley Basin for a while, and even ran for office in 1904 in Parma, where he was elected alderman.

Eventually Burroughs moved out of Idaho. His continued bouts of unemployment gave him time to try his hand at writing. In 1914 he published a book called "Tarzan of the Apes," and its character became an international fictional hero. Edgar Rice Burroughs, a writer shaped in part by his many years in Idaho.

For much more on his Idaho connection, just Google Edgar Rice Burroughs Idaho.

Edgar Rice Burroughs came to the state in the mid 1890s. His brothers worked on a ranch their father had purchased near Yale, Idaho (which the brothers, Yale graduates, had convinced the postal service to name) and he got a job there, too, as a cowhand. But he didn’t stick with any job very long. Burroughs worked for a local dredge company for a while, then found himself unemployed.

With the help of his brother Harry, Edgar Rice Burroughs purchased a stationery and cigar store in Pocatello at 233 West Center Street in 1898. He also established a Pocatello delivery service, sometimes delivering newspapers himself from the back of a black horse named Crow. It turned out that Burroughs was not as successful at selling books as he would later become at writing them. He sold the failing Pocatello store a year after he bought it.

He tried ranching again. He worked for a dredge company again, this time in Minidoka. He lived in the Stanley Basin for a while, and even ran for office in 1904 in Parma, where he was elected alderman.

Eventually Burroughs moved out of Idaho. His continued bouts of unemployment gave him time to try his hand at writing. In 1914 he published a book called "Tarzan of the Apes," and its character became an international fictional hero. Edgar Rice Burroughs, a writer shaped in part by his many years in Idaho.

For much more on his Idaho connection, just Google Edgar Rice Burroughs Idaho.

Published on February 19, 2021 04:00

February 18, 2021

Who Owns those Parks?

People probably assume that all the state parks in Idaho are owned by the State of Idaho. That’s far from true. The Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (IDPR) manages Dworshak and Hells Gate state parks under an agreement with the US Army Corps of Engineers, the property owner. Spring Shores and Sandy Point in Lucky Peak State Park are also owned by the Corps.

The Coeur d’Alene Tribe owns Coeur d’Alenes Old Mission State Park. Lake Cascade and Lake Walcott state parks are managed under an agreement with the property owner, the Bureau of Reclamation. City of Rocks National Reserve is operated jointly with the National Park Service. IDPR owns some of the land, including nearby Castle Rocks State Park, and the Bureau of Land Management owns some. At Land of the Yankee Fork State Park, the property at Custer and Bonanza is owned by the Forest Service. The ATV/motorbike trail that runs between the historic Bayhorse townsite and the visitor center near Challis crosses both BLM and Forest Service property.

Winchester Lake State Park, below, was created in 1968, about the time this picture was taken. The park belongs to the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, but it is managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation through an agreement. It features a secluded campground, several rental yurts, hiking trails, and many fishing piers. The nearby Wolf Education and Research Center, operated by the Nez Perce tribe, is a major attraction.

The Coeur d’Alene Tribe owns Coeur d’Alenes Old Mission State Park. Lake Cascade and Lake Walcott state parks are managed under an agreement with the property owner, the Bureau of Reclamation. City of Rocks National Reserve is operated jointly with the National Park Service. IDPR owns some of the land, including nearby Castle Rocks State Park, and the Bureau of Land Management owns some. At Land of the Yankee Fork State Park, the property at Custer and Bonanza is owned by the Forest Service. The ATV/motorbike trail that runs between the historic Bayhorse townsite and the visitor center near Challis crosses both BLM and Forest Service property.

Winchester Lake State Park, below, was created in 1968, about the time this picture was taken. The park belongs to the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, but it is managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation through an agreement. It features a secluded campground, several rental yurts, hiking trails, and many fishing piers. The nearby Wolf Education and Research Center, operated by the Nez Perce tribe, is a major attraction.

Published on February 18, 2021 04:00