Rick Just's Blog, page 138

January 18, 2021

Boise's First Female Dentist

The August 27, 1892 edition of the Idaho Statesman had a note about the first female dentist in the world. Henrietta Hirschfeldt was said to have graduated in 1869 from Pennsylvania College. This was apparently as common as roller skates on a goose, thus worthy of the mention.

When, in 1906, Boise was under threat of having its own distaff dentist, the Statesman felt it necessary to assure readers that Carrie Berthaumm, DDS, was probably physically capable of extracting a tooth. “She is a well-built woman of—well, probably 20 or over, and appears eminently capable of handling any refractory molars that she might encounter without calling in the assistance of the janitor of her building, or using a block and tackle.”

That snide remark aside, Berthaumm did practice dentistry in Boise for many years with little further notice from the local paper, save for the weekly ads she purchased announcing her practice.

As if the sarcastic reporter who announced the beginning of her practice were prescient, Dr. Berthaumm did employ a janitor. He made the news because of dentistry, though not for helping her pull teeth. In June 1917, the janitor discovered that Berthaumm’s office had been broken into. Nothing seemed to be missing, but the culprit had left something behind. The janitor found a good-sized piece of gold on the floor. Knowing that Berthaumm did not handle gold filings, he took the little treasure to her colleague, Dr. Cohn, who discovered his desk drawer had been jimmied and the gold within stolen. All the dental offices in town had been hit over the weekend by the sloppy burglar, who took what gold he or she could find but left the costlier platinum behind.

When, in 1906, Boise was under threat of having its own distaff dentist, the Statesman felt it necessary to assure readers that Carrie Berthaumm, DDS, was probably physically capable of extracting a tooth. “She is a well-built woman of—well, probably 20 or over, and appears eminently capable of handling any refractory molars that she might encounter without calling in the assistance of the janitor of her building, or using a block and tackle.”

That snide remark aside, Berthaumm did practice dentistry in Boise for many years with little further notice from the local paper, save for the weekly ads she purchased announcing her practice.

As if the sarcastic reporter who announced the beginning of her practice were prescient, Dr. Berthaumm did employ a janitor. He made the news because of dentistry, though not for helping her pull teeth. In June 1917, the janitor discovered that Berthaumm’s office had been broken into. Nothing seemed to be missing, but the culprit had left something behind. The janitor found a good-sized piece of gold on the floor. Knowing that Berthaumm did not handle gold filings, he took the little treasure to her colleague, Dr. Cohn, who discovered his desk drawer had been jimmied and the gold within stolen. All the dental offices in town had been hit over the weekend by the sloppy burglar, who took what gold he or she could find but left the costlier platinum behind.

Published on January 18, 2021 04:00

January 17, 2021

Bills Island

Yesterday, I wrote about the name Island Park and how its origins are unclear. Today, we look at an island within Island Park. One thing we know for sure about I.P. Bills Island is that it had nothing to do with the naming of Island Park. Bills Island (for short) only became an island in 1939.

That was the year the Bureau of Reclamation completed the Island Park Dam on the North Fork of the Snake River, more commonly known today as the Henrys Fork.

Much of the land behind the dam was owned by Judge Daniel P. Trude. Trude noticed that what had been a hill on his property would become an island once the reservoir filled. Prior to that inundation, he had a causeway built to the hill.

Judge Trude’s family enjoyed the island as a picnic spot and a place for family outings. When he passed away, his widow and two daughters decided to give the land to the Boy Scouts of America. The Scouts snubbed their generosity on the grounds that administering the island would be too difficult. Disappointed, the family decided to sell the property.

Ivan P. Bills retired in 1945 after 30 years in the automobile business. He started a guide service in Island Park the next year. He was able to scrape together $15,000 to buy 285 acres on the island. The Forest Service managed an additional 100 acres.

Bills and his wife, Yetta, moved into a lodge on the property. They rented rooms and boats and continued with the guiding business. Before long it became apparent that selling lots on the island was a better business than catering to anglers. In 1948 they divided the property into 112 lots, all on the waterfront and began selling them for $1,000 each. The Bills platted another 96 lots on the interior of the island in 1964.

In 1971 I.P. Bills, who was 73, decided it was time to back away from his duties as administrator of the island. Property owners there formed the Bills Island Association, a 501 (c) 4, elected a board of directors, and began making decisions about issues that came up.

Bills passed away in 1984. The island named after him is still managed today by the association. It is a gated property.

Thanks to the association for much of the information used in this post.

A Google Earth shot of Bills Island.

A Google Earth shot of Bills Island.

That was the year the Bureau of Reclamation completed the Island Park Dam on the North Fork of the Snake River, more commonly known today as the Henrys Fork.

Much of the land behind the dam was owned by Judge Daniel P. Trude. Trude noticed that what had been a hill on his property would become an island once the reservoir filled. Prior to that inundation, he had a causeway built to the hill.

Judge Trude’s family enjoyed the island as a picnic spot and a place for family outings. When he passed away, his widow and two daughters decided to give the land to the Boy Scouts of America. The Scouts snubbed their generosity on the grounds that administering the island would be too difficult. Disappointed, the family decided to sell the property.

Ivan P. Bills retired in 1945 after 30 years in the automobile business. He started a guide service in Island Park the next year. He was able to scrape together $15,000 to buy 285 acres on the island. The Forest Service managed an additional 100 acres.

Bills and his wife, Yetta, moved into a lodge on the property. They rented rooms and boats and continued with the guiding business. Before long it became apparent that selling lots on the island was a better business than catering to anglers. In 1948 they divided the property into 112 lots, all on the waterfront and began selling them for $1,000 each. The Bills platted another 96 lots on the interior of the island in 1964.

In 1971 I.P. Bills, who was 73, decided it was time to back away from his duties as administrator of the island. Property owners there formed the Bills Island Association, a 501 (c) 4, elected a board of directors, and began making decisions about issues that came up.

Bills passed away in 1984. The island named after him is still managed today by the association. It is a gated property.

Thanks to the association for much of the information used in this post.

A Google Earth shot of Bills Island.

A Google Earth shot of Bills Island.

Published on January 17, 2021 04:00

January 16, 2021

Why Island Park?

I’ve been reading

Beyond the One Hundredth Meridian

by Wallace Stenger. It’s about the explorations of John Wesley Powell. At one point in the narrative, Stenger mentioned that Powell named a spot along the Green River, Island Park.

That caught my ear because of the fuzzy origins of the name Island Park in Eastern Idaho. There are a few theories on where the name came from. In the earliest days of Idaho history there were apparently large mats of reeds and foliage floating on Henrys Lake. The name might have come from those floating islands. Another theory is that the “islands” referred to the open meadows in the otherwise heavily forested area. Yet a third theory is just the opposite. That one holds that the “islands” were islands of timber on the sagebrush plain. This is the one that Lalia Boone, author of Idaho Place Names, seems to prefer, since it came from Charlie Pond, one of the early lodge owners in the area.

As I often do, I searched through newspaper archives for early mentions of the name Island Park. There were many, most referring to other places across the country called Island Park. There was an Island Park racecourse in Albany, New York around 1890. There is a Round Island Park also in New York State. There’s a Woodsdale Island Park in Cincinnati. An Island Park Farm in Kentucky was exporting horses to Europe in the late 1800s. And, of course, there is Island Park in St. Anthony, Idaho.

I confess that last one was new to me, and it made me wonder if the name of the region north of St. Anthony had come somehow from that little island off Bridge Street.

After reading the etymology of the word “park” in the Oxford English Dictionary, it occurs to me that some of today’s confusion is about that part of the name. We often think of a park as something developed and managed by a governmental entity. Within the Island Park region, there are two state parks, Henrys Lake and Harriman. So, parks within a park.

The older meaning of the word, and one still used casually today, is something like an outdoor place where the public can recreate. But one of the many definitions and usages caught my eye: “Applied in some parts of the United States, especially Colorado and Wyoming, to a high plateau-like valley among the mountains.”

That definition fits Island Park, which is a plateau flattened by a collapsed caldera. It also sounds a lot like Charlie Pond’s origin story for the name as reported by Lalia Boone.

None of this speculation proves anything, but it helps me better understand a confusing name. It also reminds me of a favorite saying of my late friend and mentor John Freemuth: “God can’t make Wilderness. Only Congress can do that.” Lest you think that blasphemous, John’s point was that from a public lands standpoint “Wilderness” is a designation given by Congress. Similarly, “park” in its official sense is a designation of a governmental entity. That doesn’t stop anyone from referring to a place they love as wilderness or a park.

Tomorrow I’ll tell you about an island in Island Park that came about long after the area got its name A little island in Millionaire’s Hole, Harriman State Park, in Island Park.

A little island in Millionaire’s Hole, Harriman State Park, in Island Park.

That caught my ear because of the fuzzy origins of the name Island Park in Eastern Idaho. There are a few theories on where the name came from. In the earliest days of Idaho history there were apparently large mats of reeds and foliage floating on Henrys Lake. The name might have come from those floating islands. Another theory is that the “islands” referred to the open meadows in the otherwise heavily forested area. Yet a third theory is just the opposite. That one holds that the “islands” were islands of timber on the sagebrush plain. This is the one that Lalia Boone, author of Idaho Place Names, seems to prefer, since it came from Charlie Pond, one of the early lodge owners in the area.

As I often do, I searched through newspaper archives for early mentions of the name Island Park. There were many, most referring to other places across the country called Island Park. There was an Island Park racecourse in Albany, New York around 1890. There is a Round Island Park also in New York State. There’s a Woodsdale Island Park in Cincinnati. An Island Park Farm in Kentucky was exporting horses to Europe in the late 1800s. And, of course, there is Island Park in St. Anthony, Idaho.

I confess that last one was new to me, and it made me wonder if the name of the region north of St. Anthony had come somehow from that little island off Bridge Street.

After reading the etymology of the word “park” in the Oxford English Dictionary, it occurs to me that some of today’s confusion is about that part of the name. We often think of a park as something developed and managed by a governmental entity. Within the Island Park region, there are two state parks, Henrys Lake and Harriman. So, parks within a park.

The older meaning of the word, and one still used casually today, is something like an outdoor place where the public can recreate. But one of the many definitions and usages caught my eye: “Applied in some parts of the United States, especially Colorado and Wyoming, to a high plateau-like valley among the mountains.”

That definition fits Island Park, which is a plateau flattened by a collapsed caldera. It also sounds a lot like Charlie Pond’s origin story for the name as reported by Lalia Boone.

None of this speculation proves anything, but it helps me better understand a confusing name. It also reminds me of a favorite saying of my late friend and mentor John Freemuth: “God can’t make Wilderness. Only Congress can do that.” Lest you think that blasphemous, John’s point was that from a public lands standpoint “Wilderness” is a designation given by Congress. Similarly, “park” in its official sense is a designation of a governmental entity. That doesn’t stop anyone from referring to a place they love as wilderness or a park.

Tomorrow I’ll tell you about an island in Island Park that came about long after the area got its name

A little island in Millionaire’s Hole, Harriman State Park, in Island Park.

A little island in Millionaire’s Hole, Harriman State Park, in Island Park.

Published on January 16, 2021 04:00

January 15, 2021

Boise's Union Block

If you’re familiar with a near-block-long group of stone buildings between Capitol Boulevard and 8th Street in downtown Boise, you probably know those structures as the Union Block. You’re right, but also a little wrong.

The building in the center of these structures is actually the Union Block all by itself, as it says on the sandstone facade. Architect John E. TourellotteIt designed the building in 1899. It was completed in 1902. This was during a little building boom in Boise. As plans were announced for the Union Block, adjacent property owners jumped on the bandwagon, matching facades on their buildings to that of the Union Block. The Idaho Statesman of July 27, 1901, noted that “The adjoining owners agreeing to immediately build, and in conformity with the plans of the new structure, means practically an entire stone block for Idaho Street.”

According to the Idaho Architecture Project Website, the Union Block Building is a Richardsonian Romanesque-styled building. The sandstone came from Table Rock and the whole thing cost $35,000 to build.

Why was the building called the Union Block? The original owners were Union supporters who wanted to show that and thumb their collective noses to southern sympathizers who were still prevalent decades after the Civil War.

This was apparently a common tactic. Boise’s Union Block was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. Joining it in that honor are at least eleven other Union Blocks around the country, including one in Iowa, two in Kansas, one in Maine, two in Michigan, one in North Dakota, one in New York, one in Ohio, one in Oregon, and one in Utah.

The building in the center of these structures is actually the Union Block all by itself, as it says on the sandstone facade. Architect John E. TourellotteIt designed the building in 1899. It was completed in 1902. This was during a little building boom in Boise. As plans were announced for the Union Block, adjacent property owners jumped on the bandwagon, matching facades on their buildings to that of the Union Block. The Idaho Statesman of July 27, 1901, noted that “The adjoining owners agreeing to immediately build, and in conformity with the plans of the new structure, means practically an entire stone block for Idaho Street.”

According to the Idaho Architecture Project Website, the Union Block Building is a Richardsonian Romanesque-styled building. The sandstone came from Table Rock and the whole thing cost $35,000 to build.

Why was the building called the Union Block? The original owners were Union supporters who wanted to show that and thumb their collective noses to southern sympathizers who were still prevalent decades after the Civil War.

This was apparently a common tactic. Boise’s Union Block was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. Joining it in that honor are at least eleven other Union Blocks around the country, including one in Iowa, two in Kansas, one in Maine, two in Michigan, one in North Dakota, one in New York, one in Ohio, one in Oregon, and one in Utah.

Published on January 15, 2021 04:00

January 14, 2021

Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers

Thanks to the Idaho Department of Transportation, the Idaho State Historical Society, and not least, Merle Wells, Idaho has a robust set of roadside historical markers. The inclination to mark historical points in the state was the genesis of the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers.

The group formed in 1925 to commemorate Idaho history. Their first act was to install a monument to honor George Grimes, one of the men who first discovered gold in the Boise Basin on August 2, 1862. He was killed a few days later and his partner, Moses Splawn, buried him in a nearby prospect hole. Splawn’s story was that hostile Indians killed Grimes. Some suspect the story might have been, let’s say, convenient.

The Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers placed 47 monuments in southwestern Idaho alone. Often, they were carved into the shape of Idaho using sandstone from Table Rock.

One problem with carving your stories about history in stone is that history doesn’t always stay the same. A prime example is the marker that was placed on Government Island in the Boise River in 1933. It was meant to commemorate the arrival of Colonel Pinkney Lugenbeel who scouted for a location of what would be Fort Boise. He settled on a site on July 4, 1863.

Certainly, this was an important link in the chain of events leading to the establishment of Boise. Lugenbeel helped plat the city a few days later.

Whoever wrote the inscription for the monument placed by the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers participated in a bit of hyperbole, not to mention misspelling. Okay, we’ll mention the misspelling, too. The inscription read:

GOVERNMENT ISLAND

THE BEGINNING OF CIVILIZATION

IN BOISE VALLEY MAJOR LUGENBILE

SENT BY THE U.S. GOV’T TO

ESTABLISH BOISE BARRACKS.

CAMPED HERE JUNE 1863

The spelling mistake was in Lugenbeel’s name. The hyperbole was to call his efforts “the beginning of civilization in Boise Valley.” Had the writer added “European style” before the word civilization, it would have been more accurate. Indians had a civilization in the valley for millennia prior to the major’s arrival.

Government Island is no longer an island, and the Lugenbeel monument is no longer in place. Boise City parks personnel removed the monument in 2017 for restoration, then had second thoughts about putting it back up with the original condescending language.

Thanks to Boise City Department of Arts and History. Much of the information in this post, including the photo below, can be found in their publication Government Island Monument—A Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers Artifact.

The group formed in 1925 to commemorate Idaho history. Their first act was to install a monument to honor George Grimes, one of the men who first discovered gold in the Boise Basin on August 2, 1862. He was killed a few days later and his partner, Moses Splawn, buried him in a nearby prospect hole. Splawn’s story was that hostile Indians killed Grimes. Some suspect the story might have been, let’s say, convenient.

The Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers placed 47 monuments in southwestern Idaho alone. Often, they were carved into the shape of Idaho using sandstone from Table Rock.

One problem with carving your stories about history in stone is that history doesn’t always stay the same. A prime example is the marker that was placed on Government Island in the Boise River in 1933. It was meant to commemorate the arrival of Colonel Pinkney Lugenbeel who scouted for a location of what would be Fort Boise. He settled on a site on July 4, 1863.

Certainly, this was an important link in the chain of events leading to the establishment of Boise. Lugenbeel helped plat the city a few days later.

Whoever wrote the inscription for the monument placed by the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers participated in a bit of hyperbole, not to mention misspelling. Okay, we’ll mention the misspelling, too. The inscription read:

GOVERNMENT ISLAND

THE BEGINNING OF CIVILIZATION

IN BOISE VALLEY MAJOR LUGENBILE

SENT BY THE U.S. GOV’T TO

ESTABLISH BOISE BARRACKS.

CAMPED HERE JUNE 1863

The spelling mistake was in Lugenbeel’s name. The hyperbole was to call his efforts “the beginning of civilization in Boise Valley.” Had the writer added “European style” before the word civilization, it would have been more accurate. Indians had a civilization in the valley for millennia prior to the major’s arrival.

Government Island is no longer an island, and the Lugenbeel monument is no longer in place. Boise City parks personnel removed the monument in 2017 for restoration, then had second thoughts about putting it back up with the original condescending language.

Thanks to Boise City Department of Arts and History. Much of the information in this post, including the photo below, can be found in their publication Government Island Monument—A Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers Artifact.

Published on January 14, 2021 04:00

January 13, 2021

Rescue Mine

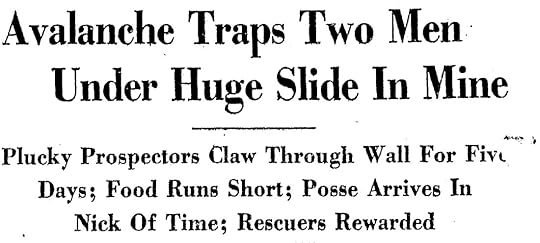

In 1890 the Idaho World reported a “curious story” about a mining operation in the Coeur d’Alenes. Two men, Thomas Burke and Delaine Llewellyn had discovered a promising lead that set them to digging on a peak known then as Welshman’s Point.

Hoping to find a rich vein of gold ore they succeeded in tunneling a distance of 171 feet. The two slept deep in their mine because it was the dead of winter. On January 13 a snow slide rammed snow and debris a hundred feet deep into the entrance of the tunnel.

The men had spent a couple of years digging rock and hauling it out of the mountain to make the tunnel. Now they were faced with digging a hundred feet of snow from within the mine to reach the outside world.

Burke and Llewellyn had food enough for six days. Water wasn’t a problem. They would not soon be short of melted snow. They began digging, carrying snow back into the tunnel behind them and dumping it on the rock floor. They dug to the point of exhaustion, toiling for five days.

The men were on the point of giving up when they saw a faint light in the snow. Minutes later a dozen miners broke through from the other side.

So thrilled were they with their rescue, that Burke and Llewellyn gave their rescuers equal shares in the mine when they struck a rich vein a few days later. It would be known from then on as the Rescue Mine.

Hoping to find a rich vein of gold ore they succeeded in tunneling a distance of 171 feet. The two slept deep in their mine because it was the dead of winter. On January 13 a snow slide rammed snow and debris a hundred feet deep into the entrance of the tunnel.

The men had spent a couple of years digging rock and hauling it out of the mountain to make the tunnel. Now they were faced with digging a hundred feet of snow from within the mine to reach the outside world.

Burke and Llewellyn had food enough for six days. Water wasn’t a problem. They would not soon be short of melted snow. They began digging, carrying snow back into the tunnel behind them and dumping it on the rock floor. They dug to the point of exhaustion, toiling for five days.

The men were on the point of giving up when they saw a faint light in the snow. Minutes later a dozen miners broke through from the other side.

So thrilled were they with their rescue, that Burke and Llewellyn gave their rescuers equal shares in the mine when they struck a rich vein a few days later. It would be known from then on as the Rescue Mine.

Published on January 13, 2021 04:00

January 12, 2021

Sliding Toward the Finish

The next time you daredevil skiers and boarders get to feeling particularly proud of yourselves, I invite you to remember the winter of 1864 and the storied slider race in Placerville.

Mining slows down a tad in the mountains in the winter when your claim is buried under 15 feet of snow, so it’s no wonder that the bored citizens of Placerville put out a challenge that January to all comers who would race against their “famous” sled, the Flying Cloud. The winner would receive $1,000.

The residents of Bannock (later to become Idaho City) were equally bored, so they began practicing with various colorfully named sleds, shooting down the icy hill on Wall Street. A sled named Slim Jim was the first to attract some attention. It crashed into a woodpile breaking Harry Phillips’ right leg and causing some injury to the head of one “Oyster Jack” Hall.

Undeterred by the carnage, G. Gans came sledding down at breakneck speeds, breaking no necks, but snapping the collar bone of a bystander.

Sled-generated injuries got so common that the local paper put out a notice that they would no longer print a recitation of damages unless there were broken bones or serious dislocations.

When the sledders judged their skills adequate for the challenge, they jumped into a big horse-drawn sleigh and, towing their railed racers behind them, set out for Placerville to take up the challenge.

After the requisite number of speeches and other entertainments, including a parade, the race was set to begin. The Bannock men determined their best shot against Placerville’s Flying Cloud was a sled called the Wide West, piloted by Bill Mullaly.

As history writer Dick d’Easum said in a 1955 column about the race, “the $1,000 bet had been lying around in the weather too long, or something, and shrunk to $50.”

That did not dampen the enthusiasm of the racers. In the first heat the Wide West was the winner. It was the same story for the second race. Then, Flying Cloud won the third. In the fourth Wide West went jetting by the judge far in the lead, except that the judge wasn’t actually there, having stepped away for a moment to conduct some personal business.

The Bannock racers claimed victory. The Placerville men took umbrage. There was a little dustup about who had actually won. Eventually everyone decided to call it a draw and no money exchanged hands. But that satisfied no one.

That evening they changed race venues, picking a murderous, ice-covered hill on which to run the sleds. The Wide West shot down the hill so fast and far ahead that d’Easum noted the “Flying Cloud was lucky to get second.”

The crowd from Bannock took a victory lap through town with drums beating and banners flying. The pilot of the Wide West glided down the street towing an empty Flying Cloud behind him. The Placerville citizens were so disgusted with the performance of their famous sled, they let him keep it like a war trophy.

Mining slows down a tad in the mountains in the winter when your claim is buried under 15 feet of snow, so it’s no wonder that the bored citizens of Placerville put out a challenge that January to all comers who would race against their “famous” sled, the Flying Cloud. The winner would receive $1,000.

The residents of Bannock (later to become Idaho City) were equally bored, so they began practicing with various colorfully named sleds, shooting down the icy hill on Wall Street. A sled named Slim Jim was the first to attract some attention. It crashed into a woodpile breaking Harry Phillips’ right leg and causing some injury to the head of one “Oyster Jack” Hall.

Undeterred by the carnage, G. Gans came sledding down at breakneck speeds, breaking no necks, but snapping the collar bone of a bystander.

Sled-generated injuries got so common that the local paper put out a notice that they would no longer print a recitation of damages unless there were broken bones or serious dislocations.

When the sledders judged their skills adequate for the challenge, they jumped into a big horse-drawn sleigh and, towing their railed racers behind them, set out for Placerville to take up the challenge.

After the requisite number of speeches and other entertainments, including a parade, the race was set to begin. The Bannock men determined their best shot against Placerville’s Flying Cloud was a sled called the Wide West, piloted by Bill Mullaly.

As history writer Dick d’Easum said in a 1955 column about the race, “the $1,000 bet had been lying around in the weather too long, or something, and shrunk to $50.”

That did not dampen the enthusiasm of the racers. In the first heat the Wide West was the winner. It was the same story for the second race. Then, Flying Cloud won the third. In the fourth Wide West went jetting by the judge far in the lead, except that the judge wasn’t actually there, having stepped away for a moment to conduct some personal business.

The Bannock racers claimed victory. The Placerville men took umbrage. There was a little dustup about who had actually won. Eventually everyone decided to call it a draw and no money exchanged hands. But that satisfied no one.

That evening they changed race venues, picking a murderous, ice-covered hill on which to run the sleds. The Wide West shot down the hill so fast and far ahead that d’Easum noted the “Flying Cloud was lucky to get second.”

The crowd from Bannock took a victory lap through town with drums beating and banners flying. The pilot of the Wide West glided down the street towing an empty Flying Cloud behind him. The Placerville citizens were so disgusted with the performance of their famous sled, they let him keep it like a war trophy.

Published on January 12, 2021 04:00

January 11, 2021

Possum Sweetheart

It will come as no shock to you that Idaho is an agricultural state. Knowing this, you would likely display little surprise to learn that there is a statue that honors a famous Idaho cow. What you might not expect is that the statue is in Washington state.

Segis Pietertje Prospect was born on a farm near Meridian in 1913 and was owned by George Layton. He sold the Holstein to E. A. Stuart, the CEO of Carnation. She became Stuart’s favorite cow. He nicknamed her Possum Sweetheart.

The company’s tagline for many years was “Carnation Condensed Milk, the milk from contented cows.” E.A. believed deeply in the philosophy that happy cows produced more milk. On the wall in the cow barn on the Carnation Farms spread, were painted these words:

“The RULE to be observed in this stable at all times, toward the cattle, young and old, is that of patience and kindness….

Remember that this is the home of mothers. Treat each cow as a mother should be treated. The giving of milk is a function of motherhood; rough treatment lessens the flow. That injures me as well as the cow. Always keep these ideas in mind in dealing with my cattle.”

No cow was more contented than Possum Sweetheart. At least none showed their contentment more in the production of milk. Sweetheart put out 37,380.1 pounds of milk in 365 days. The average production for a milk cow at the time was about 1,500 to 1,900 pounds of milk in that period of time.

The Idaho born and bred Holstein lived to be 12 years old, which is a long life for a cow. In 1928 E.A. Stuart commissioned a sculpture of his favorite cow. Well-known sculptor Frederick Willard Potter carved Possum Sweetheart’s life-size likeness into marble.

The sculpture to a cow who produced her own weight in milk every three weeks can still be seen today at Carnation Farms, Carnation, Washington.

Segis Pietertje Prospect was born on a farm near Meridian in 1913 and was owned by George Layton. He sold the Holstein to E. A. Stuart, the CEO of Carnation. She became Stuart’s favorite cow. He nicknamed her Possum Sweetheart.

The company’s tagline for many years was “Carnation Condensed Milk, the milk from contented cows.” E.A. believed deeply in the philosophy that happy cows produced more milk. On the wall in the cow barn on the Carnation Farms spread, were painted these words:

“The RULE to be observed in this stable at all times, toward the cattle, young and old, is that of patience and kindness….

Remember that this is the home of mothers. Treat each cow as a mother should be treated. The giving of milk is a function of motherhood; rough treatment lessens the flow. That injures me as well as the cow. Always keep these ideas in mind in dealing with my cattle.”

No cow was more contented than Possum Sweetheart. At least none showed their contentment more in the production of milk. Sweetheart put out 37,380.1 pounds of milk in 365 days. The average production for a milk cow at the time was about 1,500 to 1,900 pounds of milk in that period of time.

The Idaho born and bred Holstein lived to be 12 years old, which is a long life for a cow. In 1928 E.A. Stuart commissioned a sculpture of his favorite cow. Well-known sculptor Frederick Willard Potter carved Possum Sweetheart’s life-size likeness into marble.

The sculpture to a cow who produced her own weight in milk every three weeks can still be seen today at Carnation Farms, Carnation, Washington.

Published on January 11, 2021 04:00

January 10, 2021

The Switchiest Senator

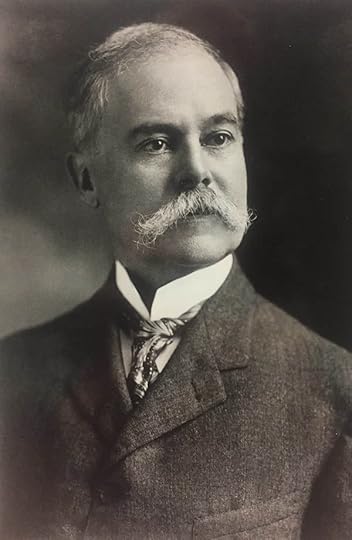

There have been 21 U.S. Senators who have switched parties while serving since 1890. Idaho Senator Fred T. Dubois was the switchiest of them all.

Dubois was elected as a Republican in 1890, the year Idaho became a state. He served a six-year term, and even headed the state’s delegation to the Republican National Convention in 1892 and 1896.

At that 1896 convention, there was a major split in the Republican Party. A faction of the party began calling themselves Silver Republicans. They were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy, the core of which was the minting of silver coins on demand, moving away from a gold-backed currency. It was a popular idea in Idaho and other western states where silver was plentiful. Dubois and other pro-silver Republicans left the convention in protest, forming their own party. He lost his 1896 bid for reelection.

As the turn of the century rolled around, Dubois led Idaho's Silver Republicans into a coalition with the Democrats. He became a rising star in the Democratic Party. Even so, he ran as a Silver Republican in 1900, and won. He was a Silver Republican when he was sworn in but switched to the Democratic party soon after. Dubois served one term as a Democrat, from 1901 to 1907, and did not seek reelection.

Senator Fred T Dubois (R, SR, D).

Senator Fred T Dubois (R, SR, D).

Dubois was elected as a Republican in 1890, the year Idaho became a state. He served a six-year term, and even headed the state’s delegation to the Republican National Convention in 1892 and 1896.

At that 1896 convention, there was a major split in the Republican Party. A faction of the party began calling themselves Silver Republicans. They were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy, the core of which was the minting of silver coins on demand, moving away from a gold-backed currency. It was a popular idea in Idaho and other western states where silver was plentiful. Dubois and other pro-silver Republicans left the convention in protest, forming their own party. He lost his 1896 bid for reelection.

As the turn of the century rolled around, Dubois led Idaho's Silver Republicans into a coalition with the Democrats. He became a rising star in the Democratic Party. Even so, he ran as a Silver Republican in 1900, and won. He was a Silver Republican when he was sworn in but switched to the Democratic party soon after. Dubois served one term as a Democrat, from 1901 to 1907, and did not seek reelection.

Senator Fred T Dubois (R, SR, D).

Senator Fred T Dubois (R, SR, D).

Published on January 10, 2021 04:00

January 9, 2021

Hoofprints on the Ceiling

Rangers at Malad Gorge State Park found a couple of sets of horse hoof prints in the park in 1990. That made a little news. Why? The hoof prints are estimated to be about a million years old.

In fact, the prints were rediscovered. A ranger was giving an interpretive program about the park when sisters Peggy Bennett Smith and Grace Bennett Goodlin interrupted to tell about a cave near the bottom of the gorge that they knew about. Smith, who lived in Hawaii, and Goodlin, visiting from Texas, had grown up nearby on their grandfather S.W. Ritchie’s ranch. As girls they had spent time fishing in the gorge and had found the cave, which they called “the pony track site.” (Deseret News, December 23, 1990)

Park Manager Kevin Lynott asked the sisters to show him the site, which they did.

Fossilized tracks of ancient animals are fairly common around the world. The ones at Malad Gorge may be unique. Rather than a depression in what was once mud, these prints were hoof-shaped mounds on the roof of the cave, almost as if you were looking at the bottom of the hoof plunging through the rock.

William (Bill) Akersten, PhD, then the curator of the Idaho Museum of Natural History studied the tracks and told how they were likely formed. There was wet sand or mud on top of an old lava flow when several horses came galloping along leaving hoof prints behind them. Speculating what they might have been running from a million years hence is just guesswork, but their existence proves that an active lava flow soon poured across the sand and the depressions left by the horses. At some point erosion from the nearby Malad River probably washed out the softer remnants of the ancient sand leaving behind a three-foot cave with hoof prints protruding from its ceiling.

The prints are about the size a modern horse might make. Though the animals that made them may have been distantly related, the prints were not made by the famous Hagerman Horse, fossils of which were found just a few miles away. The Hagerman Horse was smaller and lived about 2.5 million years earlier.

The ancient tracks may have had an impact a million years after the lava cooled. There was a proposal about that time to build a “high drop” power site that would have run a large pipe over the edge of the canyon and into the river. It would have threatened the unique hoof prints and the proposal was scrapped.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

In fact, the prints were rediscovered. A ranger was giving an interpretive program about the park when sisters Peggy Bennett Smith and Grace Bennett Goodlin interrupted to tell about a cave near the bottom of the gorge that they knew about. Smith, who lived in Hawaii, and Goodlin, visiting from Texas, had grown up nearby on their grandfather S.W. Ritchie’s ranch. As girls they had spent time fishing in the gorge and had found the cave, which they called “the pony track site.” (Deseret News, December 23, 1990)

Park Manager Kevin Lynott asked the sisters to show him the site, which they did.

Fossilized tracks of ancient animals are fairly common around the world. The ones at Malad Gorge may be unique. Rather than a depression in what was once mud, these prints were hoof-shaped mounds on the roof of the cave, almost as if you were looking at the bottom of the hoof plunging through the rock.

William (Bill) Akersten, PhD, then the curator of the Idaho Museum of Natural History studied the tracks and told how they were likely formed. There was wet sand or mud on top of an old lava flow when several horses came galloping along leaving hoof prints behind them. Speculating what they might have been running from a million years hence is just guesswork, but their existence proves that an active lava flow soon poured across the sand and the depressions left by the horses. At some point erosion from the nearby Malad River probably washed out the softer remnants of the ancient sand leaving behind a three-foot cave with hoof prints protruding from its ceiling.

The prints are about the size a modern horse might make. Though the animals that made them may have been distantly related, the prints were not made by the famous Hagerman Horse, fossils of which were found just a few miles away. The Hagerman Horse was smaller and lived about 2.5 million years earlier.

The ancient tracks may have had an impact a million years after the lava cooled. There was a proposal about that time to build a “high drop” power site that would have run a large pipe over the edge of the canyon and into the river. It would have threatened the unique hoof prints and the proposal was scrapped.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Published on January 09, 2021 04:00