Rick Just's Blog, page 141

December 19, 2020

Those Disappearing Stinker Signs

Have you ever asked yourself whatever happened to all those Stinker Station signs?

Farris Lind had built his business on humor. Suddenly, in 1965 someone wanted to throw a bucket of cold water all over the most visible part of his funny business. That someone was Claudia Alta Johnson, better known as First Lady “Ladybird” Johnson.

The Highway Beautification Act (HBA) of 1965 was Ladybird Johnson’s signature issue. She and her supporters were getting tired of the proliferation of billboards alongside federal highways in the United States. The act prohibited most outdoor advertising along Interstate and federal highways and required removal or screening of junkyards in highway viewsheds.

The law threatened a key component of Farris Lind's success. In 1969, he sued the State of Idaho because the Legislature had passed laws to bring the state into compliance with the HBA. Signs were not allowed within 660 feet of a federal highway right-of-way. Lind said, "The federal and state government have no right to deprive a farmer or other landowner of any rental income he can get from signs on his property. I owe it to myself to take a swing at bureaucracy" (Capital Journal, December 12, 1969).

For signs on private property, Lind was paying $10-$15 a month rental. Some signs were on property he'd purchased.

The lawsuit asked that the highway beautification law be declared unconstitutional. Lind contended that it was unconstitutional because it prohibited the right to conduct a lawful business and impaired contractual arrangements Lind had with landowners.

The suit didn't gain any traction, and most of the signs came down, ending a run of about 25 years of memorable advertising.

Note that you can learn much more about Fearless Farris, an Idaho Original, by reading my book about him which you can order on this page. The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

Farris Lind had built his business on humor. Suddenly, in 1965 someone wanted to throw a bucket of cold water all over the most visible part of his funny business. That someone was Claudia Alta Johnson, better known as First Lady “Ladybird” Johnson.

The Highway Beautification Act (HBA) of 1965 was Ladybird Johnson’s signature issue. She and her supporters were getting tired of the proliferation of billboards alongside federal highways in the United States. The act prohibited most outdoor advertising along Interstate and federal highways and required removal or screening of junkyards in highway viewsheds.

The law threatened a key component of Farris Lind's success. In 1969, he sued the State of Idaho because the Legislature had passed laws to bring the state into compliance with the HBA. Signs were not allowed within 660 feet of a federal highway right-of-way. Lind said, "The federal and state government have no right to deprive a farmer or other landowner of any rental income he can get from signs on his property. I owe it to myself to take a swing at bureaucracy" (Capital Journal, December 12, 1969).

For signs on private property, Lind was paying $10-$15 a month rental. Some signs were on property he'd purchased.

The lawsuit asked that the highway beautification law be declared unconstitutional. Lind contended that it was unconstitutional because it prohibited the right to conduct a lawful business and impaired contractual arrangements Lind had with landowners.

The suit didn't gain any traction, and most of the signs came down, ending a run of about 25 years of memorable advertising.

Note that you can learn much more about Fearless Farris, an Idaho Original, by reading my book about him which you can order on this page.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

The Stinker Station signs graced Idaho highway from the 1940s to the mid 1960s. Only two exist today, both on private property.

Published on December 19, 2020 04:00

December 18, 2020

This one will be on the test!

On the north face of Idaho’s highest peak, Mt. Borah (12,662 feet), and shaded nearly completely by that mountain rests a glacier of about 25 acres. It was discovered in 1975 by Bruce Otto, a Boise State University geology student. Some have called the mountain cirque glacier Otto Glacier in honor of the man who discovered it.

In recent years, with climate change on everyone’s mind, there was speculation that the glacier had melted away. But two teams, one consisting of members of the Sloan family led by Collin Sloan, and the other consisting of US Forest Service employees trekked to the glacier in 2017 and found that it was largely still intact.

How could climbers have missed a 25-acre glacier during all the years that people have been hiking to the top? Well, about two-thirds of the glacier is perpetually covered with rock debris. Glimpsing a cirque with a snowbank isn’t unusual at most times of the year. Apparently, no one had taken the trouble to climb down to that perpetual patch of white to determine if it was a glacier until 1975.

So, what makes a patch of snow and ice a glacier? According to the report (take a deep breath here) The Otto Glacier on Borah Peak, Lost River Range, Custer County, Idaho: Reconnaissance Survey Finds Further Evidence for Active Glacier Watershed Monitoring Program, “A glacier is defined as a perennial mass of land ice formed by the recrystallization of snow that accumulates stress leading to the down-slope or outward motion of the ice mass.” A couple of important terms there are “perennial” and “motion.” Measurements using Google Earth imagery over a three-year period concluded that the glacier moves downslope between 50 and 200 cm per year.

I should mention that the authors of the above referenced paper were Joshua Keeley and Mathew Warbitton.

There are probably several shaded spots in Idaho mountains above 10,000 feet where one can find ice year-round. Rock glaciers are boulders fields that have ice occupying the spaces between them, but the deposits don’t really grow enough to cause the whole mass to move.

Glaciers move slowly, so barring a major meltdown they don’t make the news very often. One need not be fleet-footed to get out of their way.

The glacier on Borah Peak may soon be making the news, though. Idaho has the distinction of being one of the states without a named glacier. Sure, Florida and Kansas are in that category, too, but Idaho actually has a glacier. It just isn’t named. Note that I mentioned this one was sometimes called Otto Glacier. It might be an excellent honor for Mr. Otto to have a glacier named after him, but one must be dead before a geographical feature can honor one. Bruce Otto is probably not eager to meet that requirement.

Who makes up these rules? Someone has to, or there would be chaos in cartographic circles. The U.S. Geographical Names Board (USGNB) is the entity that decides what name is official and should go on maps.

A proposal to name the feature the Borah Glacier recently went before the Idaho Geographical Names Advisory Council (IGNAC). The council recommended that the name Borah Glacier be placed on that icy feature. That recommendation goes before the Idaho State Historical Society Board of Directors. If they approve the recommendation, it is then submitted to USGNB for a final decision. I’m monitoring that process and will let you know the outcome.

Bruce Otto at the glacier in 1975.

Bruce Otto at the glacier in 1975.

In recent years, with climate change on everyone’s mind, there was speculation that the glacier had melted away. But two teams, one consisting of members of the Sloan family led by Collin Sloan, and the other consisting of US Forest Service employees trekked to the glacier in 2017 and found that it was largely still intact.

How could climbers have missed a 25-acre glacier during all the years that people have been hiking to the top? Well, about two-thirds of the glacier is perpetually covered with rock debris. Glimpsing a cirque with a snowbank isn’t unusual at most times of the year. Apparently, no one had taken the trouble to climb down to that perpetual patch of white to determine if it was a glacier until 1975.

So, what makes a patch of snow and ice a glacier? According to the report (take a deep breath here) The Otto Glacier on Borah Peak, Lost River Range, Custer County, Idaho: Reconnaissance Survey Finds Further Evidence for Active Glacier Watershed Monitoring Program, “A glacier is defined as a perennial mass of land ice formed by the recrystallization of snow that accumulates stress leading to the down-slope or outward motion of the ice mass.” A couple of important terms there are “perennial” and “motion.” Measurements using Google Earth imagery over a three-year period concluded that the glacier moves downslope between 50 and 200 cm per year.

I should mention that the authors of the above referenced paper were Joshua Keeley and Mathew Warbitton.

There are probably several shaded spots in Idaho mountains above 10,000 feet where one can find ice year-round. Rock glaciers are boulders fields that have ice occupying the spaces between them, but the deposits don’t really grow enough to cause the whole mass to move.

Glaciers move slowly, so barring a major meltdown they don’t make the news very often. One need not be fleet-footed to get out of their way.

The glacier on Borah Peak may soon be making the news, though. Idaho has the distinction of being one of the states without a named glacier. Sure, Florida and Kansas are in that category, too, but Idaho actually has a glacier. It just isn’t named. Note that I mentioned this one was sometimes called Otto Glacier. It might be an excellent honor for Mr. Otto to have a glacier named after him, but one must be dead before a geographical feature can honor one. Bruce Otto is probably not eager to meet that requirement.

Who makes up these rules? Someone has to, or there would be chaos in cartographic circles. The U.S. Geographical Names Board (USGNB) is the entity that decides what name is official and should go on maps.

A proposal to name the feature the Borah Glacier recently went before the Idaho Geographical Names Advisory Council (IGNAC). The council recommended that the name Borah Glacier be placed on that icy feature. That recommendation goes before the Idaho State Historical Society Board of Directors. If they approve the recommendation, it is then submitted to USGNB for a final decision. I’m monitoring that process and will let you know the outcome.

Bruce Otto at the glacier in 1975.

Bruce Otto at the glacier in 1975.

Published on December 18, 2020 04:00

December 17, 2020

Harry Orchard's Conversion

There are enough stories about Harry Orchard to fill a hundred blog posts. Today’s is about how he found religion.

Harry Orchard is well-known in Idaho as the man who rigged the bomb on that Caldwell gate that killed Frank Steunenberg, former governor of Idaho. Less well-known is that Harry’s real name was Albert Edward Horsley, a onetime cheese maker from Wooler, Ontario, Canada.

Orchard pleaded guilty to the murder and turned state’s evidence in the famous trial of “Big Bill” Haywood and Charles Moyer, both leaders in the Western Federation of Miners, and labor activist George Pettibone. Clarence Darrow got those men off, but Orchard went to prison, admitting to 26 murders.

Orchard’s conversion started before his sentencing in 1908. He had been moved to plead guilty by his reading of the Bible and was convinced it was the only way to save his soul. At first sentenced to hang, that sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment.

In the early days of his sentence, Orchard received a visit from the 21-year-old son of Governor Steunenberg, Julian. The young man brought a packet of pamphlets and books associated with the Seventh-day Adventist Church on the behest of his mother, Eveline Belle Steunenberg. She and her children were church members, and she urged Orchard to “give his life fully to Christ.”

He did so, joining the Adventist faith. He was baptized January 1, 1909 at the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Mrs. Steunenberg saw God’s hand in the assassination of her husband in a way that comforted her. It came out that Orchard had made three previous attempts to kill the man, all of which failed. On the day of the assassination, the former governor had told his family he was moved to worship with them. Though his death came just hours later, Mrs. Steunenberg came to believe God had stayed the hand of the assassin long enough to bring the governor into the fold. She would petition for Harry Orchard’s pardon and release in 1922.

Harry Orchard spent 46 years in Idaho’s prison system—though mostly not within the walls of the prison. That’s a story for another day. Orchard died April 13, 1954, at the age of 88. He was the longest serving prisoner in the system. His funeral service was conducted by the Boise Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Harry Orchard, right, raised hundreds of chickens and turkey at the old Idaho Penitentiary. He spent most of his 46 years at the prison living in a little house outside of the walls.

Harry Orchard, right, raised hundreds of chickens and turkey at the old Idaho Penitentiary. He spent most of his 46 years at the prison living in a little house outside of the walls.

Harry Orchard is well-known in Idaho as the man who rigged the bomb on that Caldwell gate that killed Frank Steunenberg, former governor of Idaho. Less well-known is that Harry’s real name was Albert Edward Horsley, a onetime cheese maker from Wooler, Ontario, Canada.

Orchard pleaded guilty to the murder and turned state’s evidence in the famous trial of “Big Bill” Haywood and Charles Moyer, both leaders in the Western Federation of Miners, and labor activist George Pettibone. Clarence Darrow got those men off, but Orchard went to prison, admitting to 26 murders.

Orchard’s conversion started before his sentencing in 1908. He had been moved to plead guilty by his reading of the Bible and was convinced it was the only way to save his soul. At first sentenced to hang, that sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment.

In the early days of his sentence, Orchard received a visit from the 21-year-old son of Governor Steunenberg, Julian. The young man brought a packet of pamphlets and books associated with the Seventh-day Adventist Church on the behest of his mother, Eveline Belle Steunenberg. She and her children were church members, and she urged Orchard to “give his life fully to Christ.”

He did so, joining the Adventist faith. He was baptized January 1, 1909 at the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Mrs. Steunenberg saw God’s hand in the assassination of her husband in a way that comforted her. It came out that Orchard had made three previous attempts to kill the man, all of which failed. On the day of the assassination, the former governor had told his family he was moved to worship with them. Though his death came just hours later, Mrs. Steunenberg came to believe God had stayed the hand of the assassin long enough to bring the governor into the fold. She would petition for Harry Orchard’s pardon and release in 1922.

Harry Orchard spent 46 years in Idaho’s prison system—though mostly not within the walls of the prison. That’s a story for another day. Orchard died April 13, 1954, at the age of 88. He was the longest serving prisoner in the system. His funeral service was conducted by the Boise Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Harry Orchard, right, raised hundreds of chickens and turkey at the old Idaho Penitentiary. He spent most of his 46 years at the prison living in a little house outside of the walls.

Harry Orchard, right, raised hundreds of chickens and turkey at the old Idaho Penitentiary. He spent most of his 46 years at the prison living in a little house outside of the walls.

Published on December 17, 2020 04:00

December 16, 2020

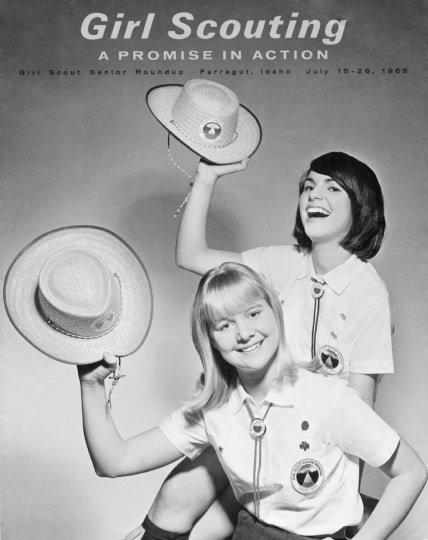

The Girl Scouts Created a State Park

The Girl Scouts played a huge role in the creation of Idaho’s state parks system. Governor Robert E. Smylie had been trying to convince the Legislature for years to create a system of state parks managed by professionals. In 1965 a lot of things came together to make Smylie’s idea palatable to Legislators. He’d lined up the gift of the Railroad Ranch, which would later become Harriman State Park. The Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund program was created, offering funding for park development. The state had recently traded land that was about to end up under Dworshak Reservoir for that old Navy base on the shores of Lake Pend Orielle.

The Girl Scouts sealed the deal, though. Smylie convinced them that Farragut would be the perfect place to hold the 1965 national Girl Scout Senior Roundup. It would bring a lot of money into north Idaho. So, with that commitment from the girl scouts in hand, the Legislature finally gave Smylie the parks department he was looking for.

Now, if you’re thinking it was the Boy Scouts that had the big gatherings, you’re not wrong. Just two days after the Girl Scout Roundup concluded, Governor Smylie sent out a press release announcing that Farragut had been selected as the site for the World Boy Scout Jamboree. Smylie, said, “Idaho is bigger today. The biggest planned event in Idaho’s history is no longer a hope; it’s an assured occurrence.”

That was a great event, and so were national Boy Scout events that came along in following years. But it was the Girl Scouts who led the way.

During the opening ceremonies for the 1965 Senior Girl Scout Roundup Governor Smylie shouted over the noise, “If you want a comparison in numbers, there are as many people here on this Idaho spot right now as live in Caldwell.” The program opened with 11,000 voices singing Girl Scout songs, recordings of which still sell occasionally on eBay today.

The Girl Scouts sealed the deal, though. Smylie convinced them that Farragut would be the perfect place to hold the 1965 national Girl Scout Senior Roundup. It would bring a lot of money into north Idaho. So, with that commitment from the girl scouts in hand, the Legislature finally gave Smylie the parks department he was looking for.

Now, if you’re thinking it was the Boy Scouts that had the big gatherings, you’re not wrong. Just two days after the Girl Scout Roundup concluded, Governor Smylie sent out a press release announcing that Farragut had been selected as the site for the World Boy Scout Jamboree. Smylie, said, “Idaho is bigger today. The biggest planned event in Idaho’s history is no longer a hope; it’s an assured occurrence.”

That was a great event, and so were national Boy Scout events that came along in following years. But it was the Girl Scouts who led the way.

During the opening ceremonies for the 1965 Senior Girl Scout Roundup Governor Smylie shouted over the noise, “If you want a comparison in numbers, there are as many people here on this Idaho spot right now as live in Caldwell.” The program opened with 11,000 voices singing Girl Scout songs, recordings of which still sell occasionally on eBay today.

Published on December 16, 2020 04:00

December 15, 2020

Where the Money Went

Yesterday I told you about Angela O’Farrell Hopper, the daughter of the first family to erect a permanent building in Boise. She was convicted of embezzling from the City of Boise. Everyone was shocked. Why had she done it and where had the money gone?

In November 1933, a couple of months after Hopper’s arrest, the story began to come together when her son, John, was arrested for receiving stolen property. The complaint against 21-year-old John, or Johnny, Hopper was that he had received $20,401.49 from his mother. Angela Hopper was already in prison, and John would shortly join her there.

Young Mr. Hopper, with his aunt Theresa O’Farrell in the courtroom looking on, denied that he knew the money his mother sent him was stolen. As reported in the Idaho Statesman on February 10, 1934, he said “Why if it was patent that this was stolen money did not the telephone company, the merchants and businessmen who received this money in Boise suspect something wrong?”

The prosecution argued that he knew well his mother’s financial circumstances and must have known the money was obtained illegitimately. They produced telegrams Hopper had sent to his mother from California demanding money time and again. Johnny Hopper had an extensive record of juvenile offenses and had a reputation in his Boise neighborhood for dealing violently with his mother and aunt when he didn’t get his way.

Hopper was a dapper looking young man with a high pompadour and a pencil thin mustache. He was described in newspaper reports as a Hollywood playboy who lived in a luxurious apartment. He had married an exotic chorus girl, though that match didn’t last.

The jury took just a few hours of deliberation to find John Hopper guilty. He was sentenced to from two to five years in February of 1934.

The “playboy” seemed to quickly mend his ways while in prison, deciding to become a lawyer and taking a correspondence course in the law while there. His good behavior convinced the parole board to set him free in November 1935 after just 20 months in prison.

In December of that year, John Hopper was on his way back to Los Angeles where he had a job lined up and an attorney interested in helping him pursue his legal career.

Three weeks later Hopper was back in a Boise jail charged with being drunk and disorderly. He failed to appear at his hearing, forfeiting his bond. It was the first of several arrests and forfeitures for Hopper.

In May 1936, his mother, convicted embezzler Angela Hopper was conditionally pardoned and released under parole to a couple in San Francisco.

In May, 1937, things got serious in Boise. Police answered a call at 420 Franklin Street, the O’Farrell family mansion, and discovered Hopper’s aunt, Theresa O’Farrell in a semi-conscious condition on her front lawn. She had been beaten over the head with a heavy platter. Inside the house they found pieces of the platter in a pool of blood. While investigators were in the house, John Hopper entered and demanded to know “what has happened here?” They noted that his clothing was bloodstained and quickly arrested him for assault.

A few days later, Hopper was charged with a complaint of insanity. His aunt, Theresa O’Farrell was still recovering in a Boise hospital where her condition was serious. He was judged to be an inebriate and committed to the state mental hospital at Blackfoot by district court Judge Charles F. Winstead.

Dr. V. E. Fisher and Dr. Mary Calloway testified that the former Hollywood night life addict should be placed under medical treatment with the possibility that he might be cured.

Under Idaho law, two years was the maximum he could spend at the mental institution. He would not come close to pushing that limit.

John Hopper was released from the asylum five months later, paroled by the hospital’s superintendents. They had the power to do so but took quite a lot of heat for it. The Director of Charitable Institutions, Lewis Williams, said, “I approved the parole. If a mistake has been made I assume all responsibility. But until Hopper demonstrates by misconduct that a mistake has been made, I have no apologies to make.” Hopper left the state for San Francisco.

While researching this story I expected to find evidence that Lewis Williams would be called on his mistake of releasing John Hopper. I found no further record of imprisonment for him, though. He sold cars for a while, then dropped off the radar. John Hopper died in California in 1951. The Idaho Statesman on June 4, 1953, noted that “Mrs. Angela O’Farrell Hopper, a resident of Boise until moving to San Francisco, Cal., several years ago, died there after a long illness.” No mention was made of her pioneer family or her time in the glare of a Boise spotlight. Mugshot photo of Johnny Hopper. He was convicted of receiving stolen property, money his mother, Angela O’Farrell Hopper, embezzled from the City of Boise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Mugshot photo of Johnny Hopper. He was convicted of receiving stolen property, money his mother, Angela O’Farrell Hopper, embezzled from the City of Boise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

In November 1933, a couple of months after Hopper’s arrest, the story began to come together when her son, John, was arrested for receiving stolen property. The complaint against 21-year-old John, or Johnny, Hopper was that he had received $20,401.49 from his mother. Angela Hopper was already in prison, and John would shortly join her there.

Young Mr. Hopper, with his aunt Theresa O’Farrell in the courtroom looking on, denied that he knew the money his mother sent him was stolen. As reported in the Idaho Statesman on February 10, 1934, he said “Why if it was patent that this was stolen money did not the telephone company, the merchants and businessmen who received this money in Boise suspect something wrong?”

The prosecution argued that he knew well his mother’s financial circumstances and must have known the money was obtained illegitimately. They produced telegrams Hopper had sent to his mother from California demanding money time and again. Johnny Hopper had an extensive record of juvenile offenses and had a reputation in his Boise neighborhood for dealing violently with his mother and aunt when he didn’t get his way.

Hopper was a dapper looking young man with a high pompadour and a pencil thin mustache. He was described in newspaper reports as a Hollywood playboy who lived in a luxurious apartment. He had married an exotic chorus girl, though that match didn’t last.

The jury took just a few hours of deliberation to find John Hopper guilty. He was sentenced to from two to five years in February of 1934.

The “playboy” seemed to quickly mend his ways while in prison, deciding to become a lawyer and taking a correspondence course in the law while there. His good behavior convinced the parole board to set him free in November 1935 after just 20 months in prison.

In December of that year, John Hopper was on his way back to Los Angeles where he had a job lined up and an attorney interested in helping him pursue his legal career.

Three weeks later Hopper was back in a Boise jail charged with being drunk and disorderly. He failed to appear at his hearing, forfeiting his bond. It was the first of several arrests and forfeitures for Hopper.

In May 1936, his mother, convicted embezzler Angela Hopper was conditionally pardoned and released under parole to a couple in San Francisco.

In May, 1937, things got serious in Boise. Police answered a call at 420 Franklin Street, the O’Farrell family mansion, and discovered Hopper’s aunt, Theresa O’Farrell in a semi-conscious condition on her front lawn. She had been beaten over the head with a heavy platter. Inside the house they found pieces of the platter in a pool of blood. While investigators were in the house, John Hopper entered and demanded to know “what has happened here?” They noted that his clothing was bloodstained and quickly arrested him for assault.

A few days later, Hopper was charged with a complaint of insanity. His aunt, Theresa O’Farrell was still recovering in a Boise hospital where her condition was serious. He was judged to be an inebriate and committed to the state mental hospital at Blackfoot by district court Judge Charles F. Winstead.

Dr. V. E. Fisher and Dr. Mary Calloway testified that the former Hollywood night life addict should be placed under medical treatment with the possibility that he might be cured.

Under Idaho law, two years was the maximum he could spend at the mental institution. He would not come close to pushing that limit.

John Hopper was released from the asylum five months later, paroled by the hospital’s superintendents. They had the power to do so but took quite a lot of heat for it. The Director of Charitable Institutions, Lewis Williams, said, “I approved the parole. If a mistake has been made I assume all responsibility. But until Hopper demonstrates by misconduct that a mistake has been made, I have no apologies to make.” Hopper left the state for San Francisco.

While researching this story I expected to find evidence that Lewis Williams would be called on his mistake of releasing John Hopper. I found no further record of imprisonment for him, though. He sold cars for a while, then dropped off the radar. John Hopper died in California in 1951. The Idaho Statesman on June 4, 1953, noted that “Mrs. Angela O’Farrell Hopper, a resident of Boise until moving to San Francisco, Cal., several years ago, died there after a long illness.” No mention was made of her pioneer family or her time in the glare of a Boise spotlight.

Mugshot photo of Johnny Hopper. He was convicted of receiving stolen property, money his mother, Angela O’Farrell Hopper, embezzled from the City of Boise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Mugshot photo of Johnny Hopper. He was convicted of receiving stolen property, money his mother, Angela O’Farrell Hopper, embezzled from the City of Boise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on December 15, 2020 04:00

December 14, 2020

Boise Shocked by Embezzlement

If you pay even a little attention to Boise’s history, you’ll know about the O’Farrell Cabin, the first permanent structure built in Boise. The city has preserved the cottonwood cabin in a location not far from where it was erected in 1863. This story, much less known, is about one of the O’Farrell’s daughters and how she slipped into a scandal that rocked the city she loved.

John and Mary O’Farrell had seven children. Two died in infancy. They raised five daughters and seven adopted children. In the interest of space, I will leave the stories of most of the O’Farrells for another time, concentrating on two daughters. Theresa, born in 1867, gets three cameo appearances in the story, which is largely about Angela, who was born in 1880.

Angela O’Farrell’s name appeared frequently in early newspapers. She was a student at St. Teresa’s, and by early accounts a good one. She was lauded for her careful embroidery, her skill at playing the piano, her singing, her drawing, and the essays she wrote. In 1889 she received a “crown of excellence” for perfect conduct.

When she was 17, Angela was one of dozens of contestants in the “Queen of Idaho” or “Queen of the Intermountain Fair” contest. The 1897 Intermountain Fair was Boise’s first big chance to show itself off. It would be a spectacular event if the Idaho Statesman had anything to say about it. The newspaper reported for weeks on the celebrities who might appear, the competitions to be held, and the rodeo that would attract cowboys from several states. The Statesman sponsored the “Queen” contest, raising money for the fair by soliciting votes from all over Idaho. You could vote as often as you liked, but each vote cost ten cents.

The winner of the contest was the daughter of a wealthy Lewiston businessman, 20-year-old Miss Bessie Volmer. The Statesman described her as “six feet tall and exceedingly graceful,” and they reported, “Few women are endowed by nature with greater personal beauty.”

Volmer received 3,813 votes. The runner up, with 2002 votes was Teresa O’Farrell. Angela O’Farrell received 16 votes. We don’t know how Angela felt about this, but it is likely she was happy for her older sister.

Angela had her life to get on with, anyway. She wanted to be a teacher and was in the first class of the “Teachers Institute and School of Methods,” housed for a time at Boise High School.

The mentions in the paper of Angela O’Farrell soon after were of the well-liked teacher in Meridian.

Angela married Edward Hopper in 1907. In 1911 the Hoppers had a son and named him John.

In 1920 Angela Hopper became the Boise City Clerk. Her name appeared in the news frequently in that official capacity. Then, in 1933 her world fell apart.

The headline in the Idaho Statesman on September 28 read, “Embezzlement Charges Rock Boise City Hall; Angela Hopper Arrested.”

As the story played out over the next few weeks and months the amount of the embezzlement climbed from $10,000, to $75,000, to somewhere near $100,000. A full accounting of what she took could never be made.

Hopper pleaded guilty and was sentenced to from one to ten years in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

One question on the minds of many Boiseans was, why? Why did a well-respected woman from a pioneer family risk embezzling all that money? A second question was, where did it go?

We’re going to answer those questions in tomorrow’s blog.

Left to right are Theresa, Angela, and Eveline O’Farrell. Theresa was assaulted by Johnny O’Farrell, Angela’s son. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Left to right are Theresa, Angela, and Eveline O’Farrell. Theresa was assaulted by Johnny O’Farrell, Angela’s son. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

John and Mary O’Farrell had seven children. Two died in infancy. They raised five daughters and seven adopted children. In the interest of space, I will leave the stories of most of the O’Farrells for another time, concentrating on two daughters. Theresa, born in 1867, gets three cameo appearances in the story, which is largely about Angela, who was born in 1880.

Angela O’Farrell’s name appeared frequently in early newspapers. She was a student at St. Teresa’s, and by early accounts a good one. She was lauded for her careful embroidery, her skill at playing the piano, her singing, her drawing, and the essays she wrote. In 1889 she received a “crown of excellence” for perfect conduct.

When she was 17, Angela was one of dozens of contestants in the “Queen of Idaho” or “Queen of the Intermountain Fair” contest. The 1897 Intermountain Fair was Boise’s first big chance to show itself off. It would be a spectacular event if the Idaho Statesman had anything to say about it. The newspaper reported for weeks on the celebrities who might appear, the competitions to be held, and the rodeo that would attract cowboys from several states. The Statesman sponsored the “Queen” contest, raising money for the fair by soliciting votes from all over Idaho. You could vote as often as you liked, but each vote cost ten cents.

The winner of the contest was the daughter of a wealthy Lewiston businessman, 20-year-old Miss Bessie Volmer. The Statesman described her as “six feet tall and exceedingly graceful,” and they reported, “Few women are endowed by nature with greater personal beauty.”

Volmer received 3,813 votes. The runner up, with 2002 votes was Teresa O’Farrell. Angela O’Farrell received 16 votes. We don’t know how Angela felt about this, but it is likely she was happy for her older sister.

Angela had her life to get on with, anyway. She wanted to be a teacher and was in the first class of the “Teachers Institute and School of Methods,” housed for a time at Boise High School.

The mentions in the paper of Angela O’Farrell soon after were of the well-liked teacher in Meridian.

Angela married Edward Hopper in 1907. In 1911 the Hoppers had a son and named him John.

In 1920 Angela Hopper became the Boise City Clerk. Her name appeared in the news frequently in that official capacity. Then, in 1933 her world fell apart.

The headline in the Idaho Statesman on September 28 read, “Embezzlement Charges Rock Boise City Hall; Angela Hopper Arrested.”

As the story played out over the next few weeks and months the amount of the embezzlement climbed from $10,000, to $75,000, to somewhere near $100,000. A full accounting of what she took could never be made.

Hopper pleaded guilty and was sentenced to from one to ten years in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

One question on the minds of many Boiseans was, why? Why did a well-respected woman from a pioneer family risk embezzling all that money? A second question was, where did it go?

We’re going to answer those questions in tomorrow’s blog.

Left to right are Theresa, Angela, and Eveline O’Farrell. Theresa was assaulted by Johnny O’Farrell, Angela’s son. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Left to right are Theresa, Angela, and Eveline O’Farrell. Theresa was assaulted by Johnny O’Farrell, Angela’s son. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on December 14, 2020 04:00

December 13, 2020

Barney Oldfield in Boise

Barney Oldfield was easily the most famous autoist of his day. Yes, autoist. Newspapers had yet to settle on terms such as driver or racer or race car driver in 1902 when Oldfield switched from racing bicycles to racing cars. That happened when bike-racer Oldfield was in Salt Lake City and someone lent him a gasoline-powered bicycle to try out. Some would call that a motorcycle. Henry Ford saw him ride and asked him if he’d like to try a racing automobile. Yes. Yes, he would. Even though they couldn’t at first get the racing Ford to even start, Oldfield bought the machine and his racing career was on its way.

His first major win came about because he took the corners like a motorcycle racer, allowing the rear end of the car to slide out or fishtail around a curve. At the 1902 Manufacturer’s Challenge Cup, Oldfield beat the reigning champion by half a mile in a five-mile race using the technique.

Oldfield’s need for speed became famous, Newspapers loved to carry stories about his breaking a speed limit in some town or another. He was the first man to reach the startling speed of 60 miles per hour and the first to take a turn at the Indianapolis Speedway at over 100 mph. Police reportedly were fond of asking citizen speeders they picked up if they thought they were Barney Oldfield.

Common headlines across the country in the early part of the Twentieth Century were variations of “Oldfield Smashes Record” again and again. He didn’t confine his efforts to only racing. Oldfield was always up for a stunt. In 1910 he raced Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson, toying with the man on the track by surging ahead and falling back to let him catch up. In a wire service story, he said, “I raced Jack Johnson neither for money or glory, but to eliminate from my profession an invader who would have had to be reckoned with sooner or later.” He would have said that with his signature cigar poking from the corner of his mouth. He found early on that one driver looked much like another after a race, covered in dust or mud, but the one with a cigar in his mouth stood out.

Oldfield became a sensation at county fairs all across the country. Prior to his appearance at the 1915 fairgrounds in Boise, The Idaho Statesman ran the following tease, “If neither Barney Oldfield, the world’s master driver, nor DeLoyd Thompson, the aerial marvel, is killed or injured when they present their series of sensational, spectacular and startling stunts on the massive Chicago speedway this afternoon, tonight they will commence their 1800-mile trip to appear in their nerve-tingling feats at the Boise race track on next Thursday afternoon.”

Boise Mayor Jeremiah W. Robinson climbed on board the hype train by declaring a “half holiday” the afternoon of June 24, the day of the exhibition of speed and daring. The Statesman piled on with “Thursday afternoon the clerks and other toilers, instead of simply visualizing the fear-chilling feats may, side by side with their employers, do what has been done in every other city where Thompson and Oldfield have shown—by their spontaneous and vociferous manifestations of appreciation demonstrate forcibly and indubitably that they coincide with the opinion of Mayor Robinson that each of these death cheaters is ‘without a peer in his line.’”

All the build-up worked. When the 24th rolled around the “largest crowd ever gathered in the city” turned out to see Oldfield and Thompson. There were 8,000 paid admissions.

Oldfield putted around the track in a couple of different cars, breaking the track record each time, for “the fastest mile ever traveled in Idaho,” according to the Statesman. Thompson, meanwhile, “soared aloft like a condor and tumbled to earth like a tumbler pigeon.”

Then the paper reported on the race with totally spontaneous and not at all scripted quotes. “The real excitement, with an accompaniment of comparative thrills, was produced by the race between Oldfield in his Flat Cyclone and Thompson in his biplane.

‘No cutting corners now,’ warned Barney as they got ready to start.

‘I don’t have to, to beat you in that old stinkpot, replied Thompson.

‘For mercy’s sake don’t fly too low this time,’ pleaded Mrs. Oldfield. “I look such a fright in black and I can’t get along without Barney.’

“All right, I won’t bean him too hard.’

“Away they went, Thompson 50 feet above the flying Fiat. Down swooped the biplane on the back stretch until only inches separated the wheels from Barney’s head. Barney coaxed a few links out the Fiat and as they passed the stand the first time he was a full car length ahead of the biplane. Thompson stuck right above Barney’s poll all the way around the second time and finished with his propeller fanning Barney’s oily brow.

‘Mercy, didn’t he fly too low,’ said Mrs. Oldfield

‘Don’t you remember the race in Pittsburg,’ reminded Barney, ‘when he kept so low that I couldn’t get under him? You’re not going to collect any insurance on me, not even a strip of a tire on that kind of racing.’

“At the end of the race Thompson soared again and began dropping bombs on an impromptu fort in the middle of the enclosure while he was bombarded by a mortar within the fortification. He circled around like an eagle while the bombs cracked far behind him. The fort was soon on fire and the aviator ‘descended within the lines’ as they say in Europe.”

What a show it was. If they brought something like that to Les Bois Park today, there wouldn’t be any need to argue semantics about video racing machines.

DeLoyd Thompson in his biplane leading the race with Barney Oldfield at the Boise Fairgrounds in 1915.

DeLoyd Thompson in his biplane leading the race with Barney Oldfield at the Boise Fairgrounds in 1915.  Oldfield looks neck and neck with Thompson rounding the corner.

Oldfield looks neck and neck with Thompson rounding the corner.

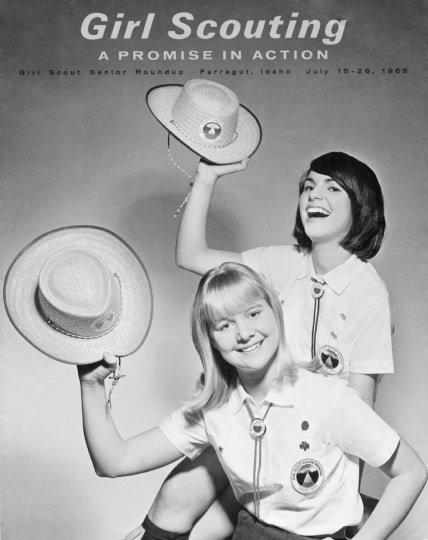

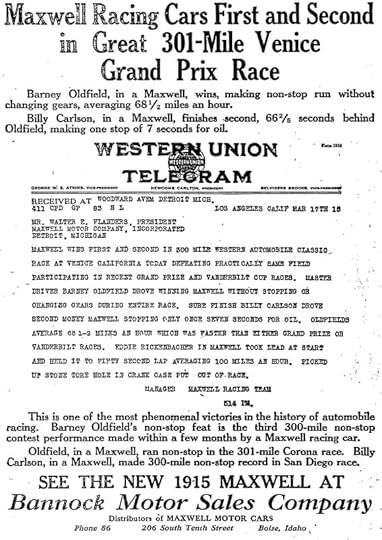

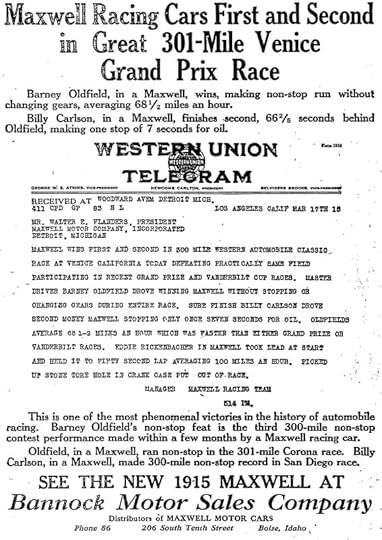

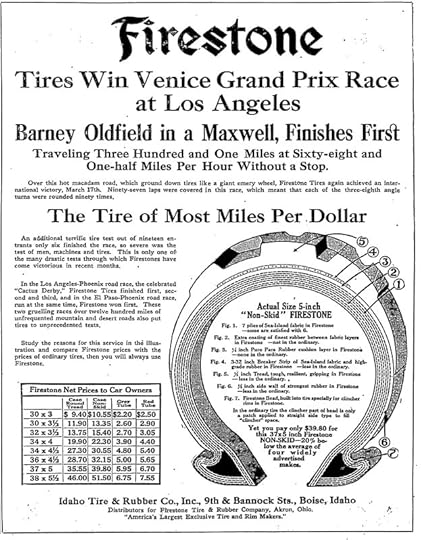

Advertisers took full advantage of Oldfield’s fame to sell their products.

Advertisers took full advantage of Oldfield’s fame to sell their products.

Can you imagine driving 301 miles at 68 ½ MPH without a stop?

Can you imagine driving 301 miles at 68 ½ MPH without a stop?

His first major win came about because he took the corners like a motorcycle racer, allowing the rear end of the car to slide out or fishtail around a curve. At the 1902 Manufacturer’s Challenge Cup, Oldfield beat the reigning champion by half a mile in a five-mile race using the technique.

Oldfield’s need for speed became famous, Newspapers loved to carry stories about his breaking a speed limit in some town or another. He was the first man to reach the startling speed of 60 miles per hour and the first to take a turn at the Indianapolis Speedway at over 100 mph. Police reportedly were fond of asking citizen speeders they picked up if they thought they were Barney Oldfield.

Common headlines across the country in the early part of the Twentieth Century were variations of “Oldfield Smashes Record” again and again. He didn’t confine his efforts to only racing. Oldfield was always up for a stunt. In 1910 he raced Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson, toying with the man on the track by surging ahead and falling back to let him catch up. In a wire service story, he said, “I raced Jack Johnson neither for money or glory, but to eliminate from my profession an invader who would have had to be reckoned with sooner or later.” He would have said that with his signature cigar poking from the corner of his mouth. He found early on that one driver looked much like another after a race, covered in dust or mud, but the one with a cigar in his mouth stood out.

Oldfield became a sensation at county fairs all across the country. Prior to his appearance at the 1915 fairgrounds in Boise, The Idaho Statesman ran the following tease, “If neither Barney Oldfield, the world’s master driver, nor DeLoyd Thompson, the aerial marvel, is killed or injured when they present their series of sensational, spectacular and startling stunts on the massive Chicago speedway this afternoon, tonight they will commence their 1800-mile trip to appear in their nerve-tingling feats at the Boise race track on next Thursday afternoon.”

Boise Mayor Jeremiah W. Robinson climbed on board the hype train by declaring a “half holiday” the afternoon of June 24, the day of the exhibition of speed and daring. The Statesman piled on with “Thursday afternoon the clerks and other toilers, instead of simply visualizing the fear-chilling feats may, side by side with their employers, do what has been done in every other city where Thompson and Oldfield have shown—by their spontaneous and vociferous manifestations of appreciation demonstrate forcibly and indubitably that they coincide with the opinion of Mayor Robinson that each of these death cheaters is ‘without a peer in his line.’”

All the build-up worked. When the 24th rolled around the “largest crowd ever gathered in the city” turned out to see Oldfield and Thompson. There were 8,000 paid admissions.

Oldfield putted around the track in a couple of different cars, breaking the track record each time, for “the fastest mile ever traveled in Idaho,” according to the Statesman. Thompson, meanwhile, “soared aloft like a condor and tumbled to earth like a tumbler pigeon.”

Then the paper reported on the race with totally spontaneous and not at all scripted quotes. “The real excitement, with an accompaniment of comparative thrills, was produced by the race between Oldfield in his Flat Cyclone and Thompson in his biplane.

‘No cutting corners now,’ warned Barney as they got ready to start.

‘I don’t have to, to beat you in that old stinkpot, replied Thompson.

‘For mercy’s sake don’t fly too low this time,’ pleaded Mrs. Oldfield. “I look such a fright in black and I can’t get along without Barney.’

“All right, I won’t bean him too hard.’

“Away they went, Thompson 50 feet above the flying Fiat. Down swooped the biplane on the back stretch until only inches separated the wheels from Barney’s head. Barney coaxed a few links out the Fiat and as they passed the stand the first time he was a full car length ahead of the biplane. Thompson stuck right above Barney’s poll all the way around the second time and finished with his propeller fanning Barney’s oily brow.

‘Mercy, didn’t he fly too low,’ said Mrs. Oldfield

‘Don’t you remember the race in Pittsburg,’ reminded Barney, ‘when he kept so low that I couldn’t get under him? You’re not going to collect any insurance on me, not even a strip of a tire on that kind of racing.’

“At the end of the race Thompson soared again and began dropping bombs on an impromptu fort in the middle of the enclosure while he was bombarded by a mortar within the fortification. He circled around like an eagle while the bombs cracked far behind him. The fort was soon on fire and the aviator ‘descended within the lines’ as they say in Europe.”

What a show it was. If they brought something like that to Les Bois Park today, there wouldn’t be any need to argue semantics about video racing machines.

DeLoyd Thompson in his biplane leading the race with Barney Oldfield at the Boise Fairgrounds in 1915.

DeLoyd Thompson in his biplane leading the race with Barney Oldfield at the Boise Fairgrounds in 1915.  Oldfield looks neck and neck with Thompson rounding the corner.

Oldfield looks neck and neck with Thompson rounding the corner. Advertisers took full advantage of Oldfield’s fame to sell their products.

Advertisers took full advantage of Oldfield’s fame to sell their products. Can you imagine driving 301 miles at 68 ½ MPH without a stop?

Can you imagine driving 301 miles at 68 ½ MPH without a stop?

Published on December 13, 2020 04:00

December 12, 2020

40 Horse Cave

I grew up hearing about picnics and other mild adventures at 40 Horse Cave. It’s located within Wolverine Canyon about 15 miles from Firth, and about 10 miles from the Blackfoot River Valley where I grew up.

I ran across a photo of 40 Horse Cave in an old family album and decided to find out more about it, mainly why it is called 40 Horse Cave.

There are two schools of thought about the name. One is that two men climbed up to the cave and commented to the other that you could put 40 horses inside. The second is that there actually were 40 horses in the cave on one occasion, that occasion being when horse thieves hid them there while being pursued by a posse.

To my disappointment, I could not find any documentation or early mentions of the cave that might have given me a clue as to the derivation of the name. I can only say that the horse thief story seems highly unlikely. The cave is about one hundred feet from the bottom of the canyon where the road is today. There was likely a trail through the canyon in the same location going back long before European settlers.

The climb up to the cave is steep and the slope has a lot of loose shale to navigate. Getting one horse, let alone 40, up into the cave would require several men or several hours. Each would have to be led up the steep slope, parked (a well-known equestrian term), and settled inside. They could not possibly be driven up the slope and into the cave even by the most persistent thieves. Further, even if one could drive horses up the slope and hide them in the cave, the resulting disturbance on the slope would be quite obvious from below. Need I mention that 40 horses standing around inside a spooky space would likely make some nervous noise?

The cave is certainly big enough to house horses, though it isn’t very deep. It goes back only about 50 feet.

I look forward to better horsemen than I speculating about how to get horses into the cave. Maybe we could make it an annual reenactment. I’ll buy the first ticket. A photo of 40 Horse Cave probably taken in the 1940s by Doug Reid.

A photo of 40 Horse Cave probably taken in the 1940s by Doug Reid.

I ran across a photo of 40 Horse Cave in an old family album and decided to find out more about it, mainly why it is called 40 Horse Cave.

There are two schools of thought about the name. One is that two men climbed up to the cave and commented to the other that you could put 40 horses inside. The second is that there actually were 40 horses in the cave on one occasion, that occasion being when horse thieves hid them there while being pursued by a posse.

To my disappointment, I could not find any documentation or early mentions of the cave that might have given me a clue as to the derivation of the name. I can only say that the horse thief story seems highly unlikely. The cave is about one hundred feet from the bottom of the canyon where the road is today. There was likely a trail through the canyon in the same location going back long before European settlers.

The climb up to the cave is steep and the slope has a lot of loose shale to navigate. Getting one horse, let alone 40, up into the cave would require several men or several hours. Each would have to be led up the steep slope, parked (a well-known equestrian term), and settled inside. They could not possibly be driven up the slope and into the cave even by the most persistent thieves. Further, even if one could drive horses up the slope and hide them in the cave, the resulting disturbance on the slope would be quite obvious from below. Need I mention that 40 horses standing around inside a spooky space would likely make some nervous noise?

The cave is certainly big enough to house horses, though it isn’t very deep. It goes back only about 50 feet.

I look forward to better horsemen than I speculating about how to get horses into the cave. Maybe we could make it an annual reenactment. I’ll buy the first ticket.

A photo of 40 Horse Cave probably taken in the 1940s by Doug Reid.

A photo of 40 Horse Cave probably taken in the 1940s by Doug Reid.

Published on December 12, 2020 04:00

December 11, 2020

The Man Who Created Idaho

I love odd little connections. Idaho has a ton of them with Abraham Lincoln. So many that they have become an obsession with Lincoln scholar and former Idaho Attorney General David Leroy.

Leroy has spent a lifetime collecting Lincoln memorabilia and documenting his connections with Idaho. The most visible result of his passion is the exhibit Abraham Lincoln, His Legacy in Idaho at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. Donated by David and Nancy Leroy in 2010, the exceptional exhibit displays more than 200 documents and artifacts.

So, what are the connections? Lincoln personally lobbied Congress for the creation of Idaho Territory, and signed that creation into law on March 3, 1863. But his interest in what would become our state started much earlier. Lincoln sought to be Idaho’s governor. Well, not exactly, but he did seek to govern Oregon Territory in 1849, part of which would one day become Idaho.

Lincoln was there at a meeting where it was decided the name of the new territory would be Idaho.

Many of the Lincoln connections were by way of Illinois and Indiana. Friends and neighbors of his helped shape the state. Samuel C. Parks, a law partner, was the territory’s first associate Supreme Court Justice. Another friend was Idaho’s seventh territorial governor, Mason Brayman. Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, sought appointment as a territorial governor of Idaho from Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but did not get it.

Years after Lincoln’s death a childhood playmate of Lincoln’s sons became U.S. Marshall of Idaho Territory, then a territorial congressional delegate. Fred T. Dubois lobbied hard to create the State of Idaho and to keep it from being split off and claimed by its neighbors.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, April 14, 1865, he had a meeting with Idaho’s delegate, William H. Wallace, about filling an Idaho supreme court vacancy. Wallace was said to have been invited to see a play that night with the Lincolns. He declined.

There’s a terrific little book about Lincoln’s connections to Idaho called Lincoln Never Slept Here, Idaho’s Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Tour written by Todd Shallat, PhD with Kathleen Craven Tuck Tuck.

#idahostatehistoricalarchives #Lincoln #abrahamlincoln #idahohistory

Two statues of Abraham Lincoln in Boise.

Two statues of Abraham Lincoln in Boise.

Leroy has spent a lifetime collecting Lincoln memorabilia and documenting his connections with Idaho. The most visible result of his passion is the exhibit Abraham Lincoln, His Legacy in Idaho at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. Donated by David and Nancy Leroy in 2010, the exceptional exhibit displays more than 200 documents and artifacts.

So, what are the connections? Lincoln personally lobbied Congress for the creation of Idaho Territory, and signed that creation into law on March 3, 1863. But his interest in what would become our state started much earlier. Lincoln sought to be Idaho’s governor. Well, not exactly, but he did seek to govern Oregon Territory in 1849, part of which would one day become Idaho.

Lincoln was there at a meeting where it was decided the name of the new territory would be Idaho.

Many of the Lincoln connections were by way of Illinois and Indiana. Friends and neighbors of his helped shape the state. Samuel C. Parks, a law partner, was the territory’s first associate Supreme Court Justice. Another friend was Idaho’s seventh territorial governor, Mason Brayman. Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, sought appointment as a territorial governor of Idaho from Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but did not get it.

Years after Lincoln’s death a childhood playmate of Lincoln’s sons became U.S. Marshall of Idaho Territory, then a territorial congressional delegate. Fred T. Dubois lobbied hard to create the State of Idaho and to keep it from being split off and claimed by its neighbors.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, April 14, 1865, he had a meeting with Idaho’s delegate, William H. Wallace, about filling an Idaho supreme court vacancy. Wallace was said to have been invited to see a play that night with the Lincolns. He declined.

There’s a terrific little book about Lincoln’s connections to Idaho called Lincoln Never Slept Here, Idaho’s Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Tour written by Todd Shallat, PhD with Kathleen Craven Tuck Tuck.

#idahostatehistoricalarchives #Lincoln #abrahamlincoln #idahohistory

Two statues of Abraham Lincoln in Boise.

Two statues of Abraham Lincoln in Boise.

Published on December 11, 2020 04:00

December 10, 2020

An Idaho G Man

All these years after their deaths, the names John Dillinger and “Baby Face” Nelson are familiar because of their infamy as crime figures. But an Idaho man you’ve probably never heard of was at least partly responsible for the demise of each.

Samuel P. Cowley was born in Franklin, Idaho in July 1899. He went to the Oneida Stake Academy, the Utah Agricultural College in Logan, Utah, and George Washington University in Washington, DC. He graduated from the latter with a law degree.

Cowley entered the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1929 as an agent and was promoted to inspector in 1934.

It was in July 1934 that a headline reading “Former Preston Man Helps Get Dillinger” ran on the front page of the Preston Citizen. Early reports said that it was Cowley’s bullet that ended the gangster’s life, but that wasn’t certain. Dillinger was gunned down after attending a picture show at the Biograph Theater in Chicago. The film he had been watching was Manhattan Melodrama starring Clark Gable, Myrna Loy, and William Powell.

Things went mostly right when Cowley participated in taking Dillinger down. Not so with “Baby Face” Nelson, whose real name was Lester Gillis.

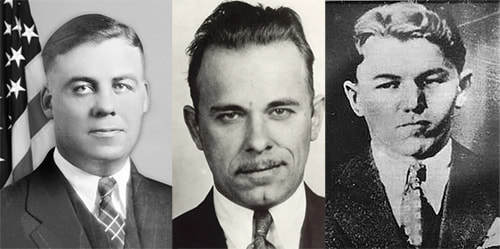

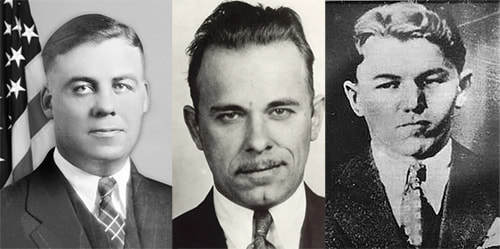

Just months after the gunfight in Chicago, on November 27, 1934, Cowley and Special Agent Herman E. Hollis stopped Nelson’s car with gunfire. Nelson, and companion John Paul Chase came out of the crippled car shooting. Cowley and Hollis returned fire, hitting and severely wounding Nelson, who would die that evening. Unfortunately, both Cowley and Hollis were also shot. Hollis died that day. Cowley passed away the next morning. John Paul Chase was later captured, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison. FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

Samuel P. Cowley was born in Franklin, Idaho in July 1899. He went to the Oneida Stake Academy, the Utah Agricultural College in Logan, Utah, and George Washington University in Washington, DC. He graduated from the latter with a law degree.

Cowley entered the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1929 as an agent and was promoted to inspector in 1934.

It was in July 1934 that a headline reading “Former Preston Man Helps Get Dillinger” ran on the front page of the Preston Citizen. Early reports said that it was Cowley’s bullet that ended the gangster’s life, but that wasn’t certain. Dillinger was gunned down after attending a picture show at the Biograph Theater in Chicago. The film he had been watching was Manhattan Melodrama starring Clark Gable, Myrna Loy, and William Powell.

Things went mostly right when Cowley participated in taking Dillinger down. Not so with “Baby Face” Nelson, whose real name was Lester Gillis.

Just months after the gunfight in Chicago, on November 27, 1934, Cowley and Special Agent Herman E. Hollis stopped Nelson’s car with gunfire. Nelson, and companion John Paul Chase came out of the crippled car shooting. Cowley and Hollis returned fire, hitting and severely wounding Nelson, who would die that evening. Unfortunately, both Cowley and Hollis were also shot. Hollis died that day. Cowley passed away the next morning. John Paul Chase was later captured, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison.

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

Published on December 10, 2020 04:00