Rick Just's Blog, page 144

November 19, 2020

Long Before Selfies, Boise Posed for Pictures

Anytime a new technology comes along, its use for illicit purposes follows closely behind. That was true with photography. The first mention of a photographer in the Idaho Statesman was a two-line story from San Francisco that told of someone being charged with the manufacture of indecent pictures. That was in 1865 when those naughty shots would have been daguerreotypes.

By 1867 the news was about a portrait photographer who had set up shop in town. Junk and Company Photographers, operated by John Junk, were offering their services in Boise’s classifieds for a couple of years. You could get “pictures in every style” as well as enameled cards. In 1869, Photographer Junk was mentioned in the Statesman once more, this time as a resident of Helena, Montana, and the victim of a fire, the fourth time flames had destroyed his business.

S.W. Wood was in town in the fall of 1873 with his camera and a tent set up on Eighth Street near the old court house where he was “prepared to do all kinds of work in his line, and at reasonable prices.” He was likely one of many traveling photographers of the day.

Boise had its own resident picture-taker again in 1874 when I.B. Curry set up shop. He operated until about 1880.

Photography was becoming a necessity among a certain class when in 1877 the Statesman carried this advice headlined “How to Fix the Mouth.”

“As the season is approaching when the ladies will be looking their prettiest, and the clear strong sunlight will be conducive to the highest success of the art, the following suggestions from a distinguished photographer may prove of great value:

“When a lady, sitting for a picture, would compose her mouth to a bland and serene character, she should, just upon entering the room, say ‘Bosom,’ and keep the expression into which the mouth subsides until the desired effect in the camera is evident.”

The article went on to suggest that if a lady were to want “to assume a distinguished and somewhat noble bearing, not suggestive of sweetness, she should say ‘Brush,’ the result of which is infallible. If she wishes to make her mouth look small, she must say ‘Flip,’ but if the mouth be already too small and needs enlarging she must say ‘Cabbage.’”

Whether or not the instructions were intended to form a mouth where the tongue would rest firmly in the cheek is not entirely clear.

The Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman covered a photo shoot of 500 students in the spring of 1887. The City School students from first grade through high school were rounded up by “Prof. Daniels,” who was the superintendent of the school district, and arranged “them in a group, the large girls and boys in the rear, and the very little folks in various pretty attitudes in the fore-ground.” According to the paper “Photographer Cook blush(ed) at finding himself the object of one thousand curious and sparkling eyes.”

It would be a treat to see that old photo and to check for goofy faces, protruding tongues, and rabbit ears from fingers. How early did that start, do you suppose?

This picture of elegant women enjoying wine was probably taken about 1889 in Boise. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

This picture of elegant women enjoying wine was probably taken about 1889 in Boise. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

By 1867 the news was about a portrait photographer who had set up shop in town. Junk and Company Photographers, operated by John Junk, were offering their services in Boise’s classifieds for a couple of years. You could get “pictures in every style” as well as enameled cards. In 1869, Photographer Junk was mentioned in the Statesman once more, this time as a resident of Helena, Montana, and the victim of a fire, the fourth time flames had destroyed his business.

S.W. Wood was in town in the fall of 1873 with his camera and a tent set up on Eighth Street near the old court house where he was “prepared to do all kinds of work in his line, and at reasonable prices.” He was likely one of many traveling photographers of the day.

Boise had its own resident picture-taker again in 1874 when I.B. Curry set up shop. He operated until about 1880.

Photography was becoming a necessity among a certain class when in 1877 the Statesman carried this advice headlined “How to Fix the Mouth.”

“As the season is approaching when the ladies will be looking their prettiest, and the clear strong sunlight will be conducive to the highest success of the art, the following suggestions from a distinguished photographer may prove of great value:

“When a lady, sitting for a picture, would compose her mouth to a bland and serene character, she should, just upon entering the room, say ‘Bosom,’ and keep the expression into which the mouth subsides until the desired effect in the camera is evident.”

The article went on to suggest that if a lady were to want “to assume a distinguished and somewhat noble bearing, not suggestive of sweetness, she should say ‘Brush,’ the result of which is infallible. If she wishes to make her mouth look small, she must say ‘Flip,’ but if the mouth be already too small and needs enlarging she must say ‘Cabbage.’”

Whether or not the instructions were intended to form a mouth where the tongue would rest firmly in the cheek is not entirely clear.

The Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman covered a photo shoot of 500 students in the spring of 1887. The City School students from first grade through high school were rounded up by “Prof. Daniels,” who was the superintendent of the school district, and arranged “them in a group, the large girls and boys in the rear, and the very little folks in various pretty attitudes in the fore-ground.” According to the paper “Photographer Cook blush(ed) at finding himself the object of one thousand curious and sparkling eyes.”

It would be a treat to see that old photo and to check for goofy faces, protruding tongues, and rabbit ears from fingers. How early did that start, do you suppose?

This picture of elegant women enjoying wine was probably taken about 1889 in Boise. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

This picture of elegant women enjoying wine was probably taken about 1889 in Boise. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on November 19, 2020 04:00

November 18, 2020

A Little Photo Mystery

Many readers will remember the story about “Jimmy the Stiff” that I posted a year ago. That story resulted in a successful Go Fund Me campaign to get James Hogan a cemetery marker.

Idaho Statesman reporter Katherine Jones covered that effort. She recently sent me this photo, sent to her by Roxann Howell Dehlin of Nampa. Ms. Dehlin saw a photo of Hogan that ran with the article, looking a bit out of place in his scruffy clothes, posing with elected officials. It reminded her of this picture her family has.

The souvenir photo, apparently made for Sen. Anthony Russell, is well done and goes to great lengths to identify him. Left nameless is the gentleman at the upper left of the picture, peeking slyly around the wall in what we might today call a photo bomb.

Practically everyone in the picture wears a hat—even the photo bomber—with the exception of two gentlemen relegated to the back row, perhaps for their error in haberdashery.

Mysteries—even the most insignificant ones—are fun. We know next to nothing about who this man was, though it is probably safe to say he was not an Idaho state senator in 1905. What’s your wild guess?

Idaho Statesman reporter Katherine Jones covered that effort. She recently sent me this photo, sent to her by Roxann Howell Dehlin of Nampa. Ms. Dehlin saw a photo of Hogan that ran with the article, looking a bit out of place in his scruffy clothes, posing with elected officials. It reminded her of this picture her family has.

The souvenir photo, apparently made for Sen. Anthony Russell, is well done and goes to great lengths to identify him. Left nameless is the gentleman at the upper left of the picture, peeking slyly around the wall in what we might today call a photo bomb.

Practically everyone in the picture wears a hat—even the photo bomber—with the exception of two gentlemen relegated to the back row, perhaps for their error in haberdashery.

Mysteries—even the most insignificant ones—are fun. We know next to nothing about who this man was, though it is probably safe to say he was not an Idaho state senator in 1905. What’s your wild guess?

Published on November 18, 2020 04:00

November 17, 2020

The Galloping Goose and the Dinkey

It’s not always a train that you might see riding the rails. You’ve probably seen small railroad work cars from time to time on the tracks with four metal wheels. They’re usually a little smaller than a Volkswagen bug. They are commonly called “speeders,” and have become popular in recent years with people who buy them, trick them out, and use them on abandoned railways.

Sometimes you’ll see a specially equipped railroad-operated pickup on the rails, using steel wheels that can be lowered down.

But have you ever seen a bus use the tracks? They were fairly common in the 20s and 30s. They were usually conversions of buses or trucks retrofitted with steel wheels to run a railroad line. They were often called Galloping Gooses. Geese, for the plural? Maybe.

You can view a Galloping Goose in Soda Springs at Corrigan Park in the heart of the city. This particular Goose had a custom wooden body and used a Model T engine. It ran between Soda Springs and the Anaconda Mine. According to Ellen Carney’s book, History of Soda Springs , the Galloping Goose would leave the mine when enough passengers had gathered to make the trip worthwhile. When it rolled in to Soda Springs the driver would ease it on to a turntable. Once parked on the turntable the passengers would get out and push the rig around so it could head back to the mine.

Soda Springs has another piece of railroad history in the same park. It’s called the Dinkey Engine. This miniature engine was also used to run back and forth between the mines. It was apparently out of service and abandoned when the Alexander Reservoir filled in 1924, drowning the Dinkey. During repairs to the reservoir in 1976, residents spotted it and drug it out. Union Pacific helped with the restoration and the city put the Dinkey on display in the park.

The Galloping Goose

The Galloping Goose  The restored Dinkey engine.

The restored Dinkey engine.

Sometimes you’ll see a specially equipped railroad-operated pickup on the rails, using steel wheels that can be lowered down.

But have you ever seen a bus use the tracks? They were fairly common in the 20s and 30s. They were usually conversions of buses or trucks retrofitted with steel wheels to run a railroad line. They were often called Galloping Gooses. Geese, for the plural? Maybe.

You can view a Galloping Goose in Soda Springs at Corrigan Park in the heart of the city. This particular Goose had a custom wooden body and used a Model T engine. It ran between Soda Springs and the Anaconda Mine. According to Ellen Carney’s book, History of Soda Springs , the Galloping Goose would leave the mine when enough passengers had gathered to make the trip worthwhile. When it rolled in to Soda Springs the driver would ease it on to a turntable. Once parked on the turntable the passengers would get out and push the rig around so it could head back to the mine.

Soda Springs has another piece of railroad history in the same park. It’s called the Dinkey Engine. This miniature engine was also used to run back and forth between the mines. It was apparently out of service and abandoned when the Alexander Reservoir filled in 1924, drowning the Dinkey. During repairs to the reservoir in 1976, residents spotted it and drug it out. Union Pacific helped with the restoration and the city put the Dinkey on display in the park.

The Galloping Goose

The Galloping Goose  The restored Dinkey engine.

The restored Dinkey engine.

Published on November 17, 2020 04:00

November 16, 2020

A Contested Ballot

At the risk of causing readers to run away jibbering incoherently, I present for your consideration a story about voting and a contested ballot. This is not a contemporary story and I’m not once going to bring up party affiliation. It is about the difference a single vote can have in an election and how important that vote can be for the candidate and the voter.

The year was 1870. An election took place that June in Boise with a slate of candidates for various offices there for the choosing. The race for Ada County Sheriff turned out to be the one to watch.

L.B. Lindsey and William Bryon were the candidates in the race, and it was a close one. Six of the ballots had some variation of Wm. Bryon's name, but not the exact name. For instance, someone had written Bryon without a first name, three had spelled the name Brion, and three spelled it Bryant. They similar issues with ballots cast for Lindsey, or Linsy, or Lindsley, or Lensy. The election judges all the variations accepted as legal ballots. Upon further examination, judges determined that a handful of people who had cast ballots were not legal voters. Those ballots were thrown out.

It came down to 419 votes for Bryon, and 418 votes for Lindsey. One vote could make the difference between a victory or a tie. There was one ballot submitted by John West that had a special status.

West was a legal voter, and he had spelled the candidate’s name right. So why was his vote originally denied? Because he was, as the papers would say at that time, a colored man. Poll workers initially denied him the vote for that reason, probably because they did not know that the 15th Amendment to the Constitution had been ratified in February of that year. That amendment reads, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The election judges determined that West’s vote was legitimate. He had written in Bryon's name, giving the new sheriff 420 votes.

That could have been the end of the story. Bryon was happy, and West was happy. West’s happiness might have been tempered a bit when Bryon arrested him a few months later on the charge of battery. West had gotten into a fistfight with Frank Slocum. The jury found West guilty. He was fined $30 and court costs, totaling $107.

That could have been the end of the story. West refused to pay the $107 and as a result, ended up in jail. He filed a writ of habeas corpus. In response, Sheriff Bryon offered a certified copy of the judgment in the case. When the Idaho Supreme Court reviewed it, they wrote a lengthy description of the case's circumstances, which local paper printed in full. We don’t have space and readers don’t have the patience to wade through that, so I’ll summarize.

The description of the case provided by the sheriff left out one detail, to wit, he failed to state what crime West was charged with. In its wisdom, the court determined that West could not be held without a stated crime for which he had been convicted. They ordered that he be discharged at once.

West, who was quick to engage in a fight, had a few other minor scrapes with the law over the years. He also got to know well the makers of laws. John West served as the master of the legislative cloakroom for many sessions of the Idaho Legislature, making sure everything was clean and in good order.

When he died at age 80, John West was remembered by the Idaho Statesman as “the dean of colored pioneers in Idaho.” No mention was made of that contested ballot.

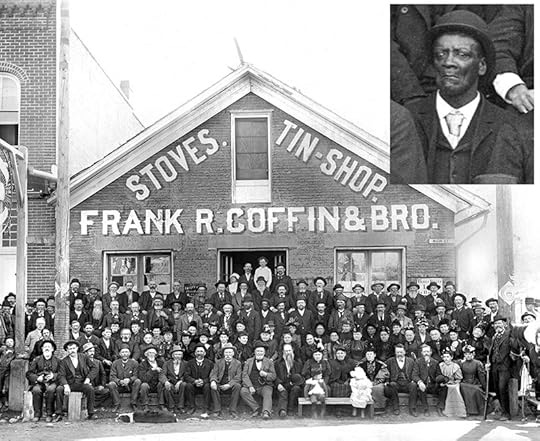

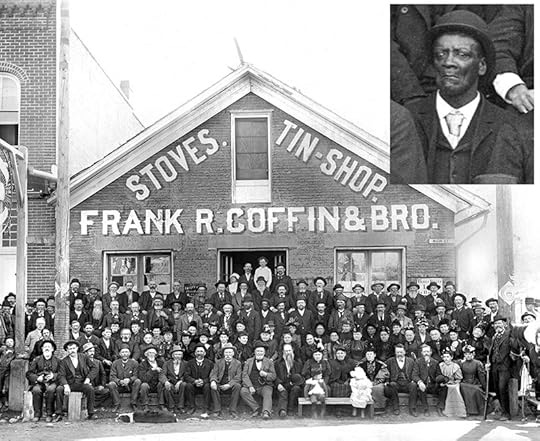

One of the few photos of John West known to exist shows him in the center of a large group of men posing in front of the Frank R. Coffin and Brother establishment in Boise. It was the largest hardware store in Idaho Territory and had locations in Hailey and Bellevue. West is near the center of the picture and shown in the inset. The purpose of the gathering is unknown. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

One of the few photos of John West known to exist shows him in the center of a large group of men posing in front of the Frank R. Coffin and Brother establishment in Boise. It was the largest hardware store in Idaho Territory and had locations in Hailey and Bellevue. West is near the center of the picture and shown in the inset. The purpose of the gathering is unknown. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The year was 1870. An election took place that June in Boise with a slate of candidates for various offices there for the choosing. The race for Ada County Sheriff turned out to be the one to watch.

L.B. Lindsey and William Bryon were the candidates in the race, and it was a close one. Six of the ballots had some variation of Wm. Bryon's name, but not the exact name. For instance, someone had written Bryon without a first name, three had spelled the name Brion, and three spelled it Bryant. They similar issues with ballots cast for Lindsey, or Linsy, or Lindsley, or Lensy. The election judges all the variations accepted as legal ballots. Upon further examination, judges determined that a handful of people who had cast ballots were not legal voters. Those ballots were thrown out.

It came down to 419 votes for Bryon, and 418 votes for Lindsey. One vote could make the difference between a victory or a tie. There was one ballot submitted by John West that had a special status.

West was a legal voter, and he had spelled the candidate’s name right. So why was his vote originally denied? Because he was, as the papers would say at that time, a colored man. Poll workers initially denied him the vote for that reason, probably because they did not know that the 15th Amendment to the Constitution had been ratified in February of that year. That amendment reads, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The election judges determined that West’s vote was legitimate. He had written in Bryon's name, giving the new sheriff 420 votes.

That could have been the end of the story. Bryon was happy, and West was happy. West’s happiness might have been tempered a bit when Bryon arrested him a few months later on the charge of battery. West had gotten into a fistfight with Frank Slocum. The jury found West guilty. He was fined $30 and court costs, totaling $107.

That could have been the end of the story. West refused to pay the $107 and as a result, ended up in jail. He filed a writ of habeas corpus. In response, Sheriff Bryon offered a certified copy of the judgment in the case. When the Idaho Supreme Court reviewed it, they wrote a lengthy description of the case's circumstances, which local paper printed in full. We don’t have space and readers don’t have the patience to wade through that, so I’ll summarize.

The description of the case provided by the sheriff left out one detail, to wit, he failed to state what crime West was charged with. In its wisdom, the court determined that West could not be held without a stated crime for which he had been convicted. They ordered that he be discharged at once.

West, who was quick to engage in a fight, had a few other minor scrapes with the law over the years. He also got to know well the makers of laws. John West served as the master of the legislative cloakroom for many sessions of the Idaho Legislature, making sure everything was clean and in good order.

When he died at age 80, John West was remembered by the Idaho Statesman as “the dean of colored pioneers in Idaho.” No mention was made of that contested ballot.

One of the few photos of John West known to exist shows him in the center of a large group of men posing in front of the Frank R. Coffin and Brother establishment in Boise. It was the largest hardware store in Idaho Territory and had locations in Hailey and Bellevue. West is near the center of the picture and shown in the inset. The purpose of the gathering is unknown. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

One of the few photos of John West known to exist shows him in the center of a large group of men posing in front of the Frank R. Coffin and Brother establishment in Boise. It was the largest hardware store in Idaho Territory and had locations in Hailey and Bellevue. West is near the center of the picture and shown in the inset. The purpose of the gathering is unknown. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on November 16, 2020 04:00

November 15, 2020

The North Side Inn

In 1910 a lavish, modern hotel could be found standing in the middle of the southern Idaho desert near where the town of Jerome is today. Actually, it is exactly where the town of Jerome is, because the hotel had been built as a way to create Jerome and sell tracts of land newly opened for farming.

Jerome Kuhn and his brother W. H. were developers from Pittsburgh who had created the North Side Land and Water Company and the South Side Land and Water Company. The former was on the north side of the Snake River and the latter to the south. The millionaire brothers were exploiting the new Milner Dam which would bring water to the thirsty desert through a system of canals.

Why start with a fancy hotel? Because the potential buyers of said property would need a place to stay while examining the land.

Jerome Kuhn left his name on the town of Jerome and the county with the same name. Possibly. There is considerable confusion about that. It might have been named for Jerome Kuhn, Sr, Jerome Kuhn, Jr, or for Jerome Hill, a prominent investor in the projects. Wendell, Idaho, meanwhile, was named after the son of W.H. Kuhn. Unless his initials were W.S., of course. I’ve seen it both ways.

But the hotel.

The North Side Inn was a landmark in Jerome for 58 years before being torn down in 1968. It was much loved, and many residents hated to see it go. Some loved it so much that they built a replica of the hotel in 2009. It was meant to function as an office building but wasn’t immediately successful in the economic downturn taking place at the time. Called Heritage Plaza, the 14,000 sq ft building resembles the North Side Inn on the exterior, but with less detail. It was still available for sale or lease as this was written.

The North Side Inn.

The North Side Inn.  Today's North Side Heritage Plaza.

Today's North Side Heritage Plaza.

Jerome Kuhn and his brother W. H. were developers from Pittsburgh who had created the North Side Land and Water Company and the South Side Land and Water Company. The former was on the north side of the Snake River and the latter to the south. The millionaire brothers were exploiting the new Milner Dam which would bring water to the thirsty desert through a system of canals.

Why start with a fancy hotel? Because the potential buyers of said property would need a place to stay while examining the land.

Jerome Kuhn left his name on the town of Jerome and the county with the same name. Possibly. There is considerable confusion about that. It might have been named for Jerome Kuhn, Sr, Jerome Kuhn, Jr, or for Jerome Hill, a prominent investor in the projects. Wendell, Idaho, meanwhile, was named after the son of W.H. Kuhn. Unless his initials were W.S., of course. I’ve seen it both ways.

But the hotel.

The North Side Inn was a landmark in Jerome for 58 years before being torn down in 1968. It was much loved, and many residents hated to see it go. Some loved it so much that they built a replica of the hotel in 2009. It was meant to function as an office building but wasn’t immediately successful in the economic downturn taking place at the time. Called Heritage Plaza, the 14,000 sq ft building resembles the North Side Inn on the exterior, but with less detail. It was still available for sale or lease as this was written.

The North Side Inn.

The North Side Inn.  Today's North Side Heritage Plaza.

Today's North Side Heritage Plaza.

Published on November 15, 2020 04:00

November 14, 2020

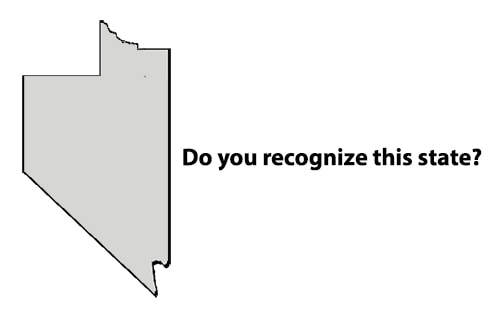

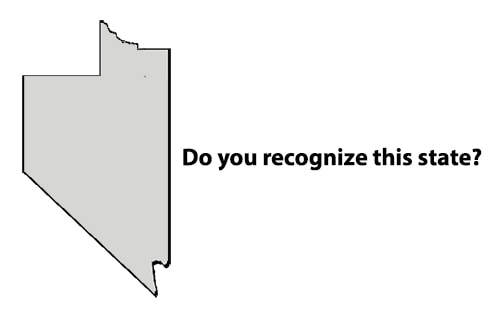

A Nevada Land Grab

In the early days of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho territorial boundaries bounced around a bit until they settled on the shapes you know today. I was surprised to see an article in the January 25, 1870 Idaho Statesman about an attempt to bite off a good chunk of Idaho by our neighbors to the south.

The article began, “We publish today a copy of a bill introduced into the United States senate by Senator Stewart of Nevada to annex the county of Owyhee and a large part of Oneida to that state.”

If the bill had passed, it likely would have led to a land grab by Oregon and Washington to annex other parts of the seven-year-old Idaho Territory. It perturbed the Statesman that the bill did not even mention the word Idaho. As the article stated, “The bill so reads that the people of Nevada are the only parties to be consulted. To the people of Idaho there is not so much as a ‘by your leave’ not even to the people of Owyhee county who are to be thus raffled off for the benefit of bankrupt Nevada.”

The Statesman didn’t take the effort very seriously, and neither did Congress. The next time the bill was mentioned in the paper was 50 years later as a footnote in the 50 Years Ago column.

The article began, “We publish today a copy of a bill introduced into the United States senate by Senator Stewart of Nevada to annex the county of Owyhee and a large part of Oneida to that state.”

If the bill had passed, it likely would have led to a land grab by Oregon and Washington to annex other parts of the seven-year-old Idaho Territory. It perturbed the Statesman that the bill did not even mention the word Idaho. As the article stated, “The bill so reads that the people of Nevada are the only parties to be consulted. To the people of Idaho there is not so much as a ‘by your leave’ not even to the people of Owyhee county who are to be thus raffled off for the benefit of bankrupt Nevada.”

The Statesman didn’t take the effort very seriously, and neither did Congress. The next time the bill was mentioned in the paper was 50 years later as a footnote in the 50 Years Ago column.

Published on November 14, 2020 04:00

November 13, 2020

Jimmy Stewart

The burning question in Boise on Valentine’s Day, 1943, was “is Jimmy Stewart really here?” The Idaho Statesman that day reported in its About Town column that it is was a rumor. “But that didn’t prevent Boise’s female population from dreaming, wondering, anticipating—and taking a good second look at every lieutenant they passed on the street.”

On page one of the same edition, the story read, “He’s Jimmy Stewart to millions of movie fans, but at Gowen Field Saturday he registered as First Lt. James M. Stewart, and on the routine registration forms, in the listing his occupation in civilian life he placed a question mark after the word ‘actor.’”

Stewart had been determined to serve his country. When he tried to enlist in the army, they turned him down because he was too skinny. At 6-foot-3, he tipped the scale at only 138 pounds. So, putting on weight became his goal. He started on a diet heavy with steaks, pasta, and milkshakes. When he stepped on the scales at his second physical in March of 1941, he was still a little shy of the minimum weight, but someone fudged the figures by a few ounces, and Jimmy Stewart was on his way to boot camp.

Eager as he was to serve, it was a bit of an adjustment. He’d been averaging $12,000 a week as an actor, according to the article “Mr. Stewart Goes to War,” by Richard L. Hayes on the HistoryNet website. An army private’s pay was $21 a month. It is reported that he sent $2.10 a month to his agent.

Stewart had a college degree from Princeton, and he was already licensed to fly multi-engine planes, so it was no surprise when he got his commission in January 1942. That meant he could wear his uniform when he presented Gary Cooper the Academy Award for best actor for Cooper’s performance in Sergeant York. Stewart had won the Oscar the year before for his role in Philadelphia Story.

The actor became a flight instructor, serving first at Mather Field, California, then transferred to Kirkland, New Mexico for bombardier school. He was at another base in New Mexico and HQ for the Second Air Force in Salt Lake City before coming to Boise, where he was a flight instructor for B-17s. He was also a sensation.

The About Town column on February 21, 1943, read, “Being constantly on the lookout for Jimmy Stewart has made Boiseans celebrity-conscious. We could have sworn we’ve been seeing Lucille Ball and John Garfield night-spotting about town…but it turned out to be Eileen Cummock, beauteous Gowen Field civilian employee, and Capt. Cox.”

About Town was breathless with chatter about Stewart. It wasn’t until June 21 that the paper published an actual photograph of the “ordinary American serving his country.” He was shown visiting back stage at a Gowen Field minstrel show at the Pinney Theater. They published another six days later of Stewart shaking hands with someone at a “recent Gowen Field Frolic.”

In July that year, Stewart got his captain’s bars and was called back to Hollywood to attend a wedding. In August, his stint in Boise was over. His stint in the military had just begun.

Jimmy Stewart would fly 20 bombing missions over Europe in World War II. Those were the missions he was credited with. He often flew self-assigned as a combat crewman when he was a commander. Oddly, he flew on one bombing mission in Vietnam as a non-duty observer in a B-52 when he was Air Force Reserve Brigadier General Stewart in 1966. He retired from the Air Force in 1968. In 1985, President Reagan promoted him to Major General on the retired list and presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Stewart didn’t spend a lot of time talking about the war or his military service. In fact, his movie contracts always included a clause that his military service would not be used as part of the publicity for the movie. Stewart passed away in 1997.

On page one of the same edition, the story read, “He’s Jimmy Stewart to millions of movie fans, but at Gowen Field Saturday he registered as First Lt. James M. Stewart, and on the routine registration forms, in the listing his occupation in civilian life he placed a question mark after the word ‘actor.’”

Stewart had been determined to serve his country. When he tried to enlist in the army, they turned him down because he was too skinny. At 6-foot-3, he tipped the scale at only 138 pounds. So, putting on weight became his goal. He started on a diet heavy with steaks, pasta, and milkshakes. When he stepped on the scales at his second physical in March of 1941, he was still a little shy of the minimum weight, but someone fudged the figures by a few ounces, and Jimmy Stewart was on his way to boot camp.

Eager as he was to serve, it was a bit of an adjustment. He’d been averaging $12,000 a week as an actor, according to the article “Mr. Stewart Goes to War,” by Richard L. Hayes on the HistoryNet website. An army private’s pay was $21 a month. It is reported that he sent $2.10 a month to his agent.

Stewart had a college degree from Princeton, and he was already licensed to fly multi-engine planes, so it was no surprise when he got his commission in January 1942. That meant he could wear his uniform when he presented Gary Cooper the Academy Award for best actor for Cooper’s performance in Sergeant York. Stewart had won the Oscar the year before for his role in Philadelphia Story.

The actor became a flight instructor, serving first at Mather Field, California, then transferred to Kirkland, New Mexico for bombardier school. He was at another base in New Mexico and HQ for the Second Air Force in Salt Lake City before coming to Boise, where he was a flight instructor for B-17s. He was also a sensation.

The About Town column on February 21, 1943, read, “Being constantly on the lookout for Jimmy Stewart has made Boiseans celebrity-conscious. We could have sworn we’ve been seeing Lucille Ball and John Garfield night-spotting about town…but it turned out to be Eileen Cummock, beauteous Gowen Field civilian employee, and Capt. Cox.”

About Town was breathless with chatter about Stewart. It wasn’t until June 21 that the paper published an actual photograph of the “ordinary American serving his country.” He was shown visiting back stage at a Gowen Field minstrel show at the Pinney Theater. They published another six days later of Stewart shaking hands with someone at a “recent Gowen Field Frolic.”

In July that year, Stewart got his captain’s bars and was called back to Hollywood to attend a wedding. In August, his stint in Boise was over. His stint in the military had just begun.

Jimmy Stewart would fly 20 bombing missions over Europe in World War II. Those were the missions he was credited with. He often flew self-assigned as a combat crewman when he was a commander. Oddly, he flew on one bombing mission in Vietnam as a non-duty observer in a B-52 when he was Air Force Reserve Brigadier General Stewart in 1966. He retired from the Air Force in 1968. In 1985, President Reagan promoted him to Major General on the retired list and presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Stewart didn’t spend a lot of time talking about the war or his military service. In fact, his movie contracts always included a clause that his military service would not be used as part of the publicity for the movie. Stewart passed away in 1997.

Published on November 13, 2020 04:00

November 12, 2020

How Much Coal?

Seeing this 1939 photo of a steam locomotive pulling into Glenns Ferry caused me to wonder about how much coal was used by your average train. As it turns out, it’s a bit like asking how much wood could a woodchuck chuck if a woodchuck could chuck wood.

The answer is, it depends. It depends on the size of the engine, the grade of the coal, the steepness of the terrain, and how much tonnage the locomotive is pulling. Temperature was also a factor. If it was winter, passenger trains were heated by steam generated by the locomotive, which made them less efficient at pulling.

I found some comments on the trusty internet from a former locomotive engineer for Union Pacific who said coal powered trains typically made stops every hundred miles or so to load up with more coal. Of course, that depends, too. It depends on the size of the tender and all the other “depends” listed above. The same engineer noted that trains had to stop twice as often to take on water, which was just as important as coal.

And, what about the guy shoveling the coal? Did he ever get a break? Not really. You didn’t want to put too much coal on at once or it wouldn’t burn efficiently. Experienced firemen would lift six to nine shovels full and dump them into the burner.

Now that I’ve given you almost no information you can really count on, I’m going to trust that some of the train fanatics who read these posts will set me straight. I’m looking at you, John Wood!

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

The answer is, it depends. It depends on the size of the engine, the grade of the coal, the steepness of the terrain, and how much tonnage the locomotive is pulling. Temperature was also a factor. If it was winter, passenger trains were heated by steam generated by the locomotive, which made them less efficient at pulling.

I found some comments on the trusty internet from a former locomotive engineer for Union Pacific who said coal powered trains typically made stops every hundred miles or so to load up with more coal. Of course, that depends, too. It depends on the size of the tender and all the other “depends” listed above. The same engineer noted that trains had to stop twice as often to take on water, which was just as important as coal.

And, what about the guy shoveling the coal? Did he ever get a break? Not really. You didn’t want to put too much coal on at once or it wouldn’t burn efficiently. Experienced firemen would lift six to nine shovels full and dump them into the burner.

Now that I’ve given you almost no information you can really count on, I’m going to trust that some of the train fanatics who read these posts will set me straight. I’m looking at you, John Wood!

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Published on November 12, 2020 04:00

November 11, 2020

Packer John, Part II

Continuing the story of Packer John from yesterday’s post.

I’ve known this story for years and had visited Packer John’s Cabin when it was a state park unit several times (it is now managed by Adams County). What I didn’t know was anything about “Packer” John. I assumed he was probably a grizzled old guy who got along better with mules than with people.

John Welch was neither grizzled nor old. He built that cabin in the winter of 1862 when he was 20 years old. It wasn’t in his plans to build a cabin, but the weather caught him on a trip south from Lewiston. He couldn’t make it over the pass into Long Valley with his string. The cabin was to keep he and his crew warm. Welch probably had no idea he was building a convention center.

After serving its role in early Idaho history, the cabin was abandoned. Emma Edwards Green, the artist who created Idaho’s state seal, stopped by the site in 1891 to paint a couple of pictures of the relic. It attracted photographers for a while, then served as an unofficial picnic and camping area. The Idaho Legislature appropriated $500 in 1909 to purchase the cabin and a little land—10 acres—around it. It was memorialized in 1936 with a monument placed along the road by the Daughters of the Idaho Pioneers. It became a state park in 1951 and lost that status in 1982.

But, there I go, writing about the cabin. I wanted to write about young “Packer” John Welch.

Welch ran a store in Leesburg for a while and—not surprisingly—ran a pack string on the trail between Boise and Lewiston. Packing was something he did for just a short time. He was more interested in making money than running mules, so he ended up in Salmon. “Ended up” is about right.

It’s unclear where Welch got $300 worth of gold dust, but he had it in his possession on December 21, 1867. His travelling companion, John S. Ramey had $3200 in cash and $500 worth of gold dust. They were headed from Salmon to Boise on December 15, 1867, each riding a horse and leading a pack animal.

About 25 miles south of Malad Station they were accosted by four highwaymen. Two of the robbers held guns on the pair, while their partners relieved Welch and Ramey of the valuables. It did not sit well with either of the victims, but it was Welch who decided to voice his disgruntlement.

The December 21, 1867 Idaho Statesman described it this way. “Welch complained that ‘this was too bad,’ and remarked that ‘he would meet some of them again, and he would know them, too.’” That’s when one of the guards shot him through the head.

John Ramey, who happened to be the undersheriff in Idaho County, lived to tell about the incident.

So, Packer John Welch would never be a grizzled old packer. He was 25 when he died. His brother, William, retrieved the body and took it back to Clackamas County Oregon for burial. The monument placed by the Daughters of Idaho Pioneers in 1936 still exists.

The monument placed by the Daughters of Idaho Pioneers in 1936 still exists.

I’ve known this story for years and had visited Packer John’s Cabin when it was a state park unit several times (it is now managed by Adams County). What I didn’t know was anything about “Packer” John. I assumed he was probably a grizzled old guy who got along better with mules than with people.

John Welch was neither grizzled nor old. He built that cabin in the winter of 1862 when he was 20 years old. It wasn’t in his plans to build a cabin, but the weather caught him on a trip south from Lewiston. He couldn’t make it over the pass into Long Valley with his string. The cabin was to keep he and his crew warm. Welch probably had no idea he was building a convention center.

After serving its role in early Idaho history, the cabin was abandoned. Emma Edwards Green, the artist who created Idaho’s state seal, stopped by the site in 1891 to paint a couple of pictures of the relic. It attracted photographers for a while, then served as an unofficial picnic and camping area. The Idaho Legislature appropriated $500 in 1909 to purchase the cabin and a little land—10 acres—around it. It was memorialized in 1936 with a monument placed along the road by the Daughters of the Idaho Pioneers. It became a state park in 1951 and lost that status in 1982.

But, there I go, writing about the cabin. I wanted to write about young “Packer” John Welch.

Welch ran a store in Leesburg for a while and—not surprisingly—ran a pack string on the trail between Boise and Lewiston. Packing was something he did for just a short time. He was more interested in making money than running mules, so he ended up in Salmon. “Ended up” is about right.

It’s unclear where Welch got $300 worth of gold dust, but he had it in his possession on December 21, 1867. His travelling companion, John S. Ramey had $3200 in cash and $500 worth of gold dust. They were headed from Salmon to Boise on December 15, 1867, each riding a horse and leading a pack animal.

About 25 miles south of Malad Station they were accosted by four highwaymen. Two of the robbers held guns on the pair, while their partners relieved Welch and Ramey of the valuables. It did not sit well with either of the victims, but it was Welch who decided to voice his disgruntlement.

The December 21, 1867 Idaho Statesman described it this way. “Welch complained that ‘this was too bad,’ and remarked that ‘he would meet some of them again, and he would know them, too.’” That’s when one of the guards shot him through the head.

John Ramey, who happened to be the undersheriff in Idaho County, lived to tell about the incident.

So, Packer John Welch would never be a grizzled old packer. He was 25 when he died. His brother, William, retrieved the body and took it back to Clackamas County Oregon for burial.

The monument placed by the Daughters of Idaho Pioneers in 1936 still exists.

The monument placed by the Daughters of Idaho Pioneers in 1936 still exists.

Published on November 11, 2020 04:00

November 10, 2020

Packer John, Part I

If the size of a building were the measure of its fame, Packer John’s Cabin would be at about the bottom of the list in Idaho. At 432 square feet, it probably wouldn’t even bring half a million dollars today if it were in Boise’s North End. The 18’ x 24’ cabin was built by John William Welch, Jr. to serve as a storage space and occasional shelter from winter weather. It was located roughly halfway between Lewiston and Boise on Goose Creek near what is now the tiny community of Meadows.

“Halfway” was its reason for fame. The capital of Idaho Territory was, let’s say, transitioning from Lewiston to Boise in 1863. Democrats decided the place was perfect for their first territorial convention because of its location. Before you start guffawing about Democrats needing only a phone booth for their convention, you should know a couple of things. First, there were no phone booths in 1863 and second, the Republican Party had only lately been invented.

As it turned out, the Democrats got their wires crossed somehow about where they were meeting, so the ended up trekking to Lewiston to have their confab. They did meet at Packer John’s Cabin, though, in 1864. So did some version of the Republicans.

So, a small measure of fame for a small cabin. Tomorrow, we take a look at Packer John, the man who built the cabin.

A replica of the cabin was built on the site but no longer exists.

A replica of the cabin was built on the site but no longer exists.

“Halfway” was its reason for fame. The capital of Idaho Territory was, let’s say, transitioning from Lewiston to Boise in 1863. Democrats decided the place was perfect for their first territorial convention because of its location. Before you start guffawing about Democrats needing only a phone booth for their convention, you should know a couple of things. First, there were no phone booths in 1863 and second, the Republican Party had only lately been invented.

As it turned out, the Democrats got their wires crossed somehow about where they were meeting, so the ended up trekking to Lewiston to have their confab. They did meet at Packer John’s Cabin, though, in 1864. So did some version of the Republicans.

So, a small measure of fame for a small cabin. Tomorrow, we take a look at Packer John, the man who built the cabin.

A replica of the cabin was built on the site but no longer exists.

A replica of the cabin was built on the site but no longer exists.

Published on November 10, 2020 04:00