Rick Just's Blog, page 146

October 30, 2020

Waldron's Leg

There is a lot of history buried in cemeteries, some of it a little quirky. The Oneida County Relic Preservation and Historical Society in Malad City has a story on their website, written by Sue Thomas that lives up to that label.

Twenty-five-year-old Benjamin Waldron was harvesting with a horse-drawn thresher in the fall of 1878. Somehow he slipped into the workings of the machine and got his leg caught. Locals pried him out and threw him in the back of a wagon, then set out for Logan, Utah as fast as the horses could run. They ran fast enough to save Waldron, but not his leg. Doctors in Logan had to amputate it.

It would be one of the worst puns I’ve ever come up with to say that Waldron was attached to his leg, so I’ll skip that. Let’s just say he was fond of it. He asked that the leg be buried in the Samaria Cemetery, complete with its own headstone. His friends did that, and we have the picture below as evidence. The—well, we can’t call it a headstone, can we?—marker is engraved with the words “B.W. October 30, 1878.”

Though his wishes had been carried out, Ben Waldron wasn’t quite satisfied. He suffered with pain for weeks after his leg was interred. He couldn’t get it out of his head that his appendage was twisted somehow in its resting place, and that was causing his pain. Humoring him once again, Ben’s friends dug up the leg. They reported to him that, yes, it had been twisted but they had buried it again in a more comfortable pose.

Waldron felt better after that and eventually adjusted to life with just one leg. He became a businessman in later years. We don’t know much more about him, except that he died in 1914 and is buried in the same cemetery, albeit not near his resting leg.

Twenty-five-year-old Benjamin Waldron was harvesting with a horse-drawn thresher in the fall of 1878. Somehow he slipped into the workings of the machine and got his leg caught. Locals pried him out and threw him in the back of a wagon, then set out for Logan, Utah as fast as the horses could run. They ran fast enough to save Waldron, but not his leg. Doctors in Logan had to amputate it.

It would be one of the worst puns I’ve ever come up with to say that Waldron was attached to his leg, so I’ll skip that. Let’s just say he was fond of it. He asked that the leg be buried in the Samaria Cemetery, complete with its own headstone. His friends did that, and we have the picture below as evidence. The—well, we can’t call it a headstone, can we?—marker is engraved with the words “B.W. October 30, 1878.”

Though his wishes had been carried out, Ben Waldron wasn’t quite satisfied. He suffered with pain for weeks after his leg was interred. He couldn’t get it out of his head that his appendage was twisted somehow in its resting place, and that was causing his pain. Humoring him once again, Ben’s friends dug up the leg. They reported to him that, yes, it had been twisted but they had buried it again in a more comfortable pose.

Waldron felt better after that and eventually adjusted to life with just one leg. He became a businessman in later years. We don’t know much more about him, except that he died in 1914 and is buried in the same cemetery, albeit not near his resting leg.

Published on October 30, 2020 04:00

October 29, 2020

Bombs Over Idaho

I was listening to Radio Lab on NPR a couple of years ago when the words “Rigby, Idaho” caught my attention. The program was about the Japanese Fu-Go balloon bombs that were used briefly during World War II in a largely unsuccessful attack on the United States. How unsuccessful? Most people didn’t even know it was happening.

Japanese school children were key to the effort. They spent thousands of hours gluing together 600 pieces of tissue-thin paper to make the 33-foot diameter balloons. About 9,300 balloons were launched in Japan into the jet stream. Filled with hydrogen, the 70-foot-tall balloons were equipped with a mechanism that released sandbags when the barometric pressure indicated when it was time to lighten the load. It took about six days to drop all the bags. At that time the balloons were supposed to be across the Pacific and over the U.S. where they were to drop bombs randomly on the country. The bomb balloons were launched from late 1944 into early 1945. About 300 of them made it to the U.S.

Some of the bombs exploded and some touched down without going off. The press cooperated with the government, keeping sightings out of the papers to avoid a public panic and keep targeting information from the enemy, until May 5, 1945. On that day, one Fu-Go, or “fire balloon” bumped down near Bly, Oregon, where six picnickers from a local church found it and accidentally set it off. The pastor’s pregnant wife and five children from other families were killed in the blast. Newspapers across the country carried that story, with warnings to stay away from bombs and balloons if they were sighted.

What about that balloon bomb near Rigby? It was one of several found in Idaho. One was found between Hollister and Rogerson, one near Hailey, one near Boise, one near Gilmore, and several in the American Falls area. There were no reports of explosions anywhere in the state.

At least two of the balloon bombs came close to important targets. One landed harmlessly in a duck pond near U.S. war ships at the Mare Island, California navy yard. Another balloon got tangled in power lines outside the secret Hanford, Washington facility where fuel was being refined for the atomic bomb that would later be dropped on Nagasaki.

Sketch of a balloon bomb ready to launch.

Sketch of a balloon bomb ready to launch.

Japanese school children were key to the effort. They spent thousands of hours gluing together 600 pieces of tissue-thin paper to make the 33-foot diameter balloons. About 9,300 balloons were launched in Japan into the jet stream. Filled with hydrogen, the 70-foot-tall balloons were equipped with a mechanism that released sandbags when the barometric pressure indicated when it was time to lighten the load. It took about six days to drop all the bags. At that time the balloons were supposed to be across the Pacific and over the U.S. where they were to drop bombs randomly on the country. The bomb balloons were launched from late 1944 into early 1945. About 300 of them made it to the U.S.

Some of the bombs exploded and some touched down without going off. The press cooperated with the government, keeping sightings out of the papers to avoid a public panic and keep targeting information from the enemy, until May 5, 1945. On that day, one Fu-Go, or “fire balloon” bumped down near Bly, Oregon, where six picnickers from a local church found it and accidentally set it off. The pastor’s pregnant wife and five children from other families were killed in the blast. Newspapers across the country carried that story, with warnings to stay away from bombs and balloons if they were sighted.

What about that balloon bomb near Rigby? It was one of several found in Idaho. One was found between Hollister and Rogerson, one near Hailey, one near Boise, one near Gilmore, and several in the American Falls area. There were no reports of explosions anywhere in the state.

At least two of the balloon bombs came close to important targets. One landed harmlessly in a duck pond near U.S. war ships at the Mare Island, California navy yard. Another balloon got tangled in power lines outside the secret Hanford, Washington facility where fuel was being refined for the atomic bomb that would later be dropped on Nagasaki.

Sketch of a balloon bomb ready to launch.

Sketch of a balloon bomb ready to launch.

Published on October 29, 2020 05:05

October 28, 2020

What's Your Number?

Time for another then and now feature.

At one time if you exchanged telephone numbers with someone, you were exchanging two letters and five numbers. I’m ancient enough to remember that the prefix in the Blackfoot area was SU5. The SU stood for Sunset. Firth’s FI6, stood for Fireside. That changed in the 1960s

An article in the May 18, 1961 Idaho Statesman announced the change to seven-digit numbers from the alphanumeric combinations. “Boise Main office number prefixes will be 342, 343, and 344, followed by four digits.” No doubt there was some grumbling about that, even though the digits were always there beneath the letters. Those Sunset 5, or SU5, prefixes in Blackfoot, for instance, simply became 785.

That 1961 article in the Statesman announced another major change. Idaho, along with every other state in the nation, was getting an area code, 208. More populous states got several, but Idaho could get along with just one. It was all to facilitate long-distance dialing.

There was little need for digits when Idaho’s first telephone was installed in Lewiston in 1878. There was just the one phone at the telegraph office, which according to the Lewiston Tribune did not operate well, perhaps due to “some defect in the instrument.” In 1879, John Halley’s telephone, the first in Boise, needed no number, either. It connected the stage office with his residence about a mile away. The first telephone exchange—a telephone system—in the state was started in Hailey in 1883.

So, that was then. This is now. Idaho has added a second area code. New telephone users in the state now get a 986 area code. Our growing population demands it. Today with the prevalence of cell phones and people keeping their area code when they move from another state, area codes are less and less an indicator of the location of a caller. The major grumbling point about having a second area code is that you must now use it whenever you dial any number, even if it’s across the street.

Dialing. There’s a word that could have been sent to history’s trashcan but remains in use today even though dials are now found mostly in museums.

At one time if you exchanged telephone numbers with someone, you were exchanging two letters and five numbers. I’m ancient enough to remember that the prefix in the Blackfoot area was SU5. The SU stood for Sunset. Firth’s FI6, stood for Fireside. That changed in the 1960s

An article in the May 18, 1961 Idaho Statesman announced the change to seven-digit numbers from the alphanumeric combinations. “Boise Main office number prefixes will be 342, 343, and 344, followed by four digits.” No doubt there was some grumbling about that, even though the digits were always there beneath the letters. Those Sunset 5, or SU5, prefixes in Blackfoot, for instance, simply became 785.

That 1961 article in the Statesman announced another major change. Idaho, along with every other state in the nation, was getting an area code, 208. More populous states got several, but Idaho could get along with just one. It was all to facilitate long-distance dialing.

There was little need for digits when Idaho’s first telephone was installed in Lewiston in 1878. There was just the one phone at the telegraph office, which according to the Lewiston Tribune did not operate well, perhaps due to “some defect in the instrument.” In 1879, John Halley’s telephone, the first in Boise, needed no number, either. It connected the stage office with his residence about a mile away. The first telephone exchange—a telephone system—in the state was started in Hailey in 1883.

So, that was then. This is now. Idaho has added a second area code. New telephone users in the state now get a 986 area code. Our growing population demands it. Today with the prevalence of cell phones and people keeping their area code when they move from another state, area codes are less and less an indicator of the location of a caller. The major grumbling point about having a second area code is that you must now use it whenever you dial any number, even if it’s across the street.

Dialing. There’s a word that could have been sent to history’s trashcan but remains in use today even though dials are now found mostly in museums.

Published on October 28, 2020 04:00

October 27, 2020

The Ephemeral Lake Hazel

Since my posts on Chicken Dinner Road and Protest Road, I’ve received several requests to tell how other roads got their names. I can’t research them all right away, but one did catch my attention. It was about Lake Hazel Road that runs from Maple Grove Road in Boise to S. Robinson Road in Nampa. The request wasn’t about how the road got its name. They wondered where the heck the lake was?

The answer is, there is no Lake Hazel, but there was once. Sort of.

Back in the early 1900s there was a move to create reservoirs to capture Boise River water for irrigation purposes. Potential water users contracted with David R. Hubbard, a local land owner, to excavate reservoirs called Painter Lake, Hubbard Lake (later Hubbard Reservoir), Kuna Lake, Watkins Lake, Catherine Lake, and Rawson Lake. These were to be connected by laterals. All except Rawson Lake were completed. In the meantime, the much larger Boise Project came along with the promise to bring irrigation to the valley. The lakes were abandoned because they would likely interfere with the Boise Project. Since they were not being used for water storage, all the "lakes" disappeared in later years, except for Hubbard Reservoir.

So, what does all this have to do with Lake Hazel? Painter Lake was renamed Lake Hazel at some point. Even with the new name it was fated to be a lake in name only, with no water in evidence.

Thanks to Madeline Kelley Buckendorf, who did the research on this for a National Register of Historic Places application I found from 2003.

The answer is, there is no Lake Hazel, but there was once. Sort of.

Back in the early 1900s there was a move to create reservoirs to capture Boise River water for irrigation purposes. Potential water users contracted with David R. Hubbard, a local land owner, to excavate reservoirs called Painter Lake, Hubbard Lake (later Hubbard Reservoir), Kuna Lake, Watkins Lake, Catherine Lake, and Rawson Lake. These were to be connected by laterals. All except Rawson Lake were completed. In the meantime, the much larger Boise Project came along with the promise to bring irrigation to the valley. The lakes were abandoned because they would likely interfere with the Boise Project. Since they were not being used for water storage, all the "lakes" disappeared in later years, except for Hubbard Reservoir.

So, what does all this have to do with Lake Hazel? Painter Lake was renamed Lake Hazel at some point. Even with the new name it was fated to be a lake in name only, with no water in evidence.

Thanks to Madeline Kelley Buckendorf, who did the research on this for a National Register of Historic Places application I found from 2003.

Published on October 27, 2020 04:00

October 26, 2020

The Killing of Tresore

It wasn’t unusual for me to be picking my way across the backs of downed giants, jumping little creeks, and seeking picturesque shafts of light streaming through the cedars. I’d done it many times along the shores of Priest Lake, looking for that picture that would transport the viewer to that same spot to experience my awe of the big trees.

I was the communication chief for the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation, and part of that job was to serve as photographer of the parks. I had my favorite vantage point in each park where I could catch a sunrise, or the certain shadow of a dune. At Priest Lake the cedar groves were difficult to capture; their enormity and the cathedral-like nature of the forest they formed did not easily fit into an eyepiece.

That day I found a newly downed cedar, roots pointing into the air, still clinging to chunks of earth that had served the tree for at least a century. I walked the trunk toward those roots and looked through them, down to the shallow hole they had left behind and to the grassy area just beyond. There was a familiar formation of rocks, 13 stones in the shape of a cross, placed years before at the foot of a much younger tree.

I knew at once what it was. This was a part of the park known as Shipman Point, named after Nell Shipman, silent movie star who had her own movie studio in these woods. She had likely placed those stones there herself, in memory of Tresore, her great Dane.

Tresore was a movie star himself. He had played a feature role in one of Shipman’s movies, Back to God’s Country, filmed in 1919 in Canada. Shipman adored animals and was an early advocate for their humane treatment in films. She had a menagerie with her at Priest Lake, including Brownie the Bear, Barney the Elk, cougar, deer, sled dogs, and others.

In July, 1923, someone poisoned many of those animals, including Tresore. Shipman always suspected that her landlord, to whom she owed money, had been the culprit. She mourned the loss of her Dane and memorialized him with these words: “Here lies Champion Great Dane Tresore, an artist, a soldier, and a gentleman. Killed July 17 by the cowardly hand of a human cur. He died as he lived, protecting his mistress and her property.”

What Shipman could not have known was that Tresore, in his death, played a huge part in the revival of interest in her movies some 60 years later. A BSU professor named Tom Trusky ran across an essay she had written about the poisoning of Tresore in the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. He decided to find out more about Shipman. That led him down a path on which he discovered and restored every movie she ever made, and oversaw the publication of Shipman’s autobiography. Interest in her work as a pioneer woman in films remains high today because of Tom’s efforts.

Park rangers at Priest Lake, and some locals, knew where Tresore’s grave was long before I stumbled across it, of course. For me, my personal discovery came just a few months after my friend Tom’s death. It was a quirk he would have appreciated. He would have called it “a little treat.”

I was the communication chief for the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation, and part of that job was to serve as photographer of the parks. I had my favorite vantage point in each park where I could catch a sunrise, or the certain shadow of a dune. At Priest Lake the cedar groves were difficult to capture; their enormity and the cathedral-like nature of the forest they formed did not easily fit into an eyepiece.

That day I found a newly downed cedar, roots pointing into the air, still clinging to chunks of earth that had served the tree for at least a century. I walked the trunk toward those roots and looked through them, down to the shallow hole they had left behind and to the grassy area just beyond. There was a familiar formation of rocks, 13 stones in the shape of a cross, placed years before at the foot of a much younger tree.

I knew at once what it was. This was a part of the park known as Shipman Point, named after Nell Shipman, silent movie star who had her own movie studio in these woods. She had likely placed those stones there herself, in memory of Tresore, her great Dane.

Tresore was a movie star himself. He had played a feature role in one of Shipman’s movies, Back to God’s Country, filmed in 1919 in Canada. Shipman adored animals and was an early advocate for their humane treatment in films. She had a menagerie with her at Priest Lake, including Brownie the Bear, Barney the Elk, cougar, deer, sled dogs, and others.

In July, 1923, someone poisoned many of those animals, including Tresore. Shipman always suspected that her landlord, to whom she owed money, had been the culprit. She mourned the loss of her Dane and memorialized him with these words: “Here lies Champion Great Dane Tresore, an artist, a soldier, and a gentleman. Killed July 17 by the cowardly hand of a human cur. He died as he lived, protecting his mistress and her property.”

What Shipman could not have known was that Tresore, in his death, played a huge part in the revival of interest in her movies some 60 years later. A BSU professor named Tom Trusky ran across an essay she had written about the poisoning of Tresore in the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. He decided to find out more about Shipman. That led him down a path on which he discovered and restored every movie she ever made, and oversaw the publication of Shipman’s autobiography. Interest in her work as a pioneer woman in films remains high today because of Tom’s efforts.

Park rangers at Priest Lake, and some locals, knew where Tresore’s grave was long before I stumbled across it, of course. For me, my personal discovery came just a few months after my friend Tom’s death. It was a quirk he would have appreciated. He would have called it “a little treat.”

Published on October 26, 2020 04:00

October 25, 2020

Backing into Hemingway Butte

That beep, beep, beep you hear is the sound of me backing into this story. It’s about Hemingway Butte, which today is an off-highway vehicle play area managed by the Boise District Bureau of Land Management. It includes a popular trail system and steep hillsides where OHVs and motorbikes defy gravity for a few seconds courtesy of two-cycle engines.

Hemingway Butte is about three miles southwest of Walter’s Ferry, which itself is about 15 miles south of Nampa. Beep, beep, beep.

Walters Ferry wasn’t always called that. It became Walter’s Ferry when Lewellyn R. Walter bought out his partner’s share of the ferry business in 1886. Previous owners had been John Fruit, George Blankenbecker, John Morgan, Leonard Fuqa, a Mr. Boon, Samuel Neeley, Perry Munday, Robert Duncan, and Reese Miles. But, beep, beep, we must back up to Munday for this story, because the drama took place when it was called Munday’s Ferry.

It was at Munday’s Ferry that the stage came thundering up from the south in August of 1878, its driver mortally wounded. Indians were chasing the stage and directing bullets at it. Munday and three soldiers set across the river toward the embattled stage coach, while two other soldier remained on the north side of the Snake to provide cover fire.

The soldiers and Indians exchanged fire for several minutes, according to a report in the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, while the ferry landed and the wounded stagecoach driver “quietly kept his seat, and when the boat touched the bank drove the team up the grade from the river and asked for water.”

Dr. W.W. McKay was dispatched from Boise to care for the driver. He made the dusty, 30-mile trip by buggy in two and a half hours, only to find when he got there that William Hemingway had breathed his last minutes before.

William Hemingway was the name of the stagecoach driver, and the aforementioned butte was named in his honor, as it was near there that the Indian attack began. Hemingway was buried in Silver City beside his wife and two children who had gone before.

Today, Hemingway Butte is a popular ORV destination.

Today, Hemingway Butte is a popular ORV destination.

Hemingway Butte is about three miles southwest of Walter’s Ferry, which itself is about 15 miles south of Nampa. Beep, beep, beep.

Walters Ferry wasn’t always called that. It became Walter’s Ferry when Lewellyn R. Walter bought out his partner’s share of the ferry business in 1886. Previous owners had been John Fruit, George Blankenbecker, John Morgan, Leonard Fuqa, a Mr. Boon, Samuel Neeley, Perry Munday, Robert Duncan, and Reese Miles. But, beep, beep, we must back up to Munday for this story, because the drama took place when it was called Munday’s Ferry.

It was at Munday’s Ferry that the stage came thundering up from the south in August of 1878, its driver mortally wounded. Indians were chasing the stage and directing bullets at it. Munday and three soldiers set across the river toward the embattled stage coach, while two other soldier remained on the north side of the Snake to provide cover fire.

The soldiers and Indians exchanged fire for several minutes, according to a report in the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, while the ferry landed and the wounded stagecoach driver “quietly kept his seat, and when the boat touched the bank drove the team up the grade from the river and asked for water.”

Dr. W.W. McKay was dispatched from Boise to care for the driver. He made the dusty, 30-mile trip by buggy in two and a half hours, only to find when he got there that William Hemingway had breathed his last minutes before.

William Hemingway was the name of the stagecoach driver, and the aforementioned butte was named in his honor, as it was near there that the Indian attack began. Hemingway was buried in Silver City beside his wife and two children who had gone before.

Today, Hemingway Butte is a popular ORV destination.

Today, Hemingway Butte is a popular ORV destination.

Published on October 25, 2020 04:00

October 24, 2020

The Weird Story of George Colgate

In the fall of 1893, W.E. Carlin, the son of Brig. Gen. W.P. Carlin, Commander of the department of the Columbia, Vancouver, Washington, gathered together some friends for a hunting party in the Bitterroots of Idaho. They hired a Post Falls woodsman named George Colgate to cook for their little expedition.

A.L.A. Himmelwright, a businessman from New York who was on the trip, would later write a book about it. The details he provided painted a picture of a well-outfitted expedition: 125 pounds of flour, 30 pounds of bacon, 40 pounds of salt pork, 20 pounds of beans, eight pounds of coffee, and on and on. He described the guns, including Carlin’s three-barreled weapon that had two 12-gauge shotgun bores side-by-side with a .32 rifle beneath.

The group got to Kendrick by train, where they gathered together the supplies, five saddle horses, five pack horses, a spaniel and two terriers, and set out for a hunt.

Six inches of snow fell on September 22. That concerned guide Martin Spencer. He figured it would only get deeper as they moved higher into the mountains. Carlin decided to push on despite the snow, and although their cook had become ill. George Colgate’s legs had swollen to the point where he could barely hobble around. Everyone else shared in cooking duties as his abilities waned.

In the days to come Colgate rallied, then got progressively worse. One day he couldn’t even stay on his horse. As more snow flew, members of the hunting party nursed the cook while he lay in a tent.

Fifty miles from anything like civilization the Carlin party found themselves in a desperate situation with snow blocking trails and a man who could not be moved on their hands. Colgate was so sick he couldn’t talk. The men debated what to do. Should they stick it out where they were and hope the weather would break? Should they send someone ahead to bring back a rescue party?

While they pondered, another storm struck. Food was running short. They had to get out of there.

Someone struck on the idea of building a raft to float down the Lochsa. They lashed together some logs with cord and wire and attached a long sweep with which to guide the contraption. Before setting out on the raft, Himmelwright would make a dark entry in his diary: “It is a case of trying to save five lives or sacrificing them to perform the last sad rites for Colgate.”

The men set out downriver, leaving their cook behind seemingly on death’s door.

Cutting the story short, the hunting party lost their raft in a rapid several miles downstream. They survived by shooting a few grouse, catching a few fish, and even eating one of their dogs before a rescue party found them on November 21.

And now the story gets strange.

The men of the party were well known, so the tale of their failure to return when expected and their ultimate rescue had been carried in many newspapers, including the New York Times, which also carried the story of the bottle.

What bottle? The one that was purportedly found in the Snake River by one Sam Ellis at Penewawi, some 60 miles below Lewiston. Inside the bottle was this note:

FOOT OF BITTER ROOT MOUNTAINS, Nov. 27.—I am alive and well. Tell them to come and get me as soon as any one finds this. I am 50 miles from civilization as near as I can tell. I am George Colgate, one of the lost Carlin party. My legs are better. I can walk some. Come soon. Take this to Kendrick, Idaho, and you will be liberally rewarded. My name is George Colgate, from Post Falls. This bottle came by me and I caught it and wrote these words to take me out. Direct this to St. Elmo hotel, Kendrick, Idaho.

GEORGE COLGATE

“Good bye, wife and children.”

The small bottle was corked and fastened to a piece of driftwood with a rag tied to it.

The writing on the note was compared to Colgate’s signature on a hotel register and “was found to be wonderfully close.”

Two relief parties set out to rescue Colgate in the coming months. Neither met with success. Meanwhile, Carlin was adamant that the note in the bottle was a fake designed to somehow extort money from him and ruin his reputation.

The note seems a little pat and the finding of the bottle incredible, so maybe Carlin was right. In any case, his reputation suffered. There was debate for decades about the ethics of leaving a man to die in the wilderness.

And die he did. On August 23, 1894, the remains of George Colgate were found about eight miles from the spot where he was said to have been abandoned. How did he get there along with a matchbox, some fishing line, and other personal articles? Had he rallied long enough to drag himself through the snow that far? Had he lived to write a message in a bottle?

A.L.A. Himmelwright, a businessman from New York who was on the trip, would later write a book about it. The details he provided painted a picture of a well-outfitted expedition: 125 pounds of flour, 30 pounds of bacon, 40 pounds of salt pork, 20 pounds of beans, eight pounds of coffee, and on and on. He described the guns, including Carlin’s three-barreled weapon that had two 12-gauge shotgun bores side-by-side with a .32 rifle beneath.

The group got to Kendrick by train, where they gathered together the supplies, five saddle horses, five pack horses, a spaniel and two terriers, and set out for a hunt.

Six inches of snow fell on September 22. That concerned guide Martin Spencer. He figured it would only get deeper as they moved higher into the mountains. Carlin decided to push on despite the snow, and although their cook had become ill. George Colgate’s legs had swollen to the point where he could barely hobble around. Everyone else shared in cooking duties as his abilities waned.

In the days to come Colgate rallied, then got progressively worse. One day he couldn’t even stay on his horse. As more snow flew, members of the hunting party nursed the cook while he lay in a tent.

Fifty miles from anything like civilization the Carlin party found themselves in a desperate situation with snow blocking trails and a man who could not be moved on their hands. Colgate was so sick he couldn’t talk. The men debated what to do. Should they stick it out where they were and hope the weather would break? Should they send someone ahead to bring back a rescue party?

While they pondered, another storm struck. Food was running short. They had to get out of there.

Someone struck on the idea of building a raft to float down the Lochsa. They lashed together some logs with cord and wire and attached a long sweep with which to guide the contraption. Before setting out on the raft, Himmelwright would make a dark entry in his diary: “It is a case of trying to save five lives or sacrificing them to perform the last sad rites for Colgate.”

The men set out downriver, leaving their cook behind seemingly on death’s door.

Cutting the story short, the hunting party lost their raft in a rapid several miles downstream. They survived by shooting a few grouse, catching a few fish, and even eating one of their dogs before a rescue party found them on November 21.

And now the story gets strange.

The men of the party were well known, so the tale of their failure to return when expected and their ultimate rescue had been carried in many newspapers, including the New York Times, which also carried the story of the bottle.

What bottle? The one that was purportedly found in the Snake River by one Sam Ellis at Penewawi, some 60 miles below Lewiston. Inside the bottle was this note:

FOOT OF BITTER ROOT MOUNTAINS, Nov. 27.—I am alive and well. Tell them to come and get me as soon as any one finds this. I am 50 miles from civilization as near as I can tell. I am George Colgate, one of the lost Carlin party. My legs are better. I can walk some. Come soon. Take this to Kendrick, Idaho, and you will be liberally rewarded. My name is George Colgate, from Post Falls. This bottle came by me and I caught it and wrote these words to take me out. Direct this to St. Elmo hotel, Kendrick, Idaho.

GEORGE COLGATE

“Good bye, wife and children.”

The small bottle was corked and fastened to a piece of driftwood with a rag tied to it.

The writing on the note was compared to Colgate’s signature on a hotel register and “was found to be wonderfully close.”

Two relief parties set out to rescue Colgate in the coming months. Neither met with success. Meanwhile, Carlin was adamant that the note in the bottle was a fake designed to somehow extort money from him and ruin his reputation.

The note seems a little pat and the finding of the bottle incredible, so maybe Carlin was right. In any case, his reputation suffered. There was debate for decades about the ethics of leaving a man to die in the wilderness.

And die he did. On August 23, 1894, the remains of George Colgate were found about eight miles from the spot where he was said to have been abandoned. How did he get there along with a matchbox, some fishing line, and other personal articles? Had he rallied long enough to drag himself through the snow that far? Had he lived to write a message in a bottle?

Published on October 24, 2020 04:00

October 23, 2020

A Dry Snake River

The Snake River Basin Adjudication (SRBA) was an administrative and legal process that began in 1987 to determine the water rights in the Snake River Basin drainage. The best history of that battle can be found in the book A Little Dam Problem, by Jim Jones, who as a water attorney, Idaho Attorney General, and finally an Idaho Supreme Court Justice, was in it to the top of his chest waders. The Final Unified Decree for the SRBA was signed on August 25, 2014, bringing a measure of certainty to holders of Idaho water rights. I’d love to sum it up in a couple of paragraphs, but the story is too complex for this format. I recommend Jim’s 374-page book as the ultimate summation.

What I can do is give you a little peek at an early indicator that there was trouble with Idaho’s system of allocating water.

It startled me to see an article in the August 11, 1905, Idaho Republican, one of the Blackfoot Newspapers at the time. The startling headline was “Snake River Goes Dry.” Was it on the front page in a shouting font stretching all the way across beneath the banner? No, it was on page five. The headline was the same size as the body copy, albeit in bold face.

It seems that upstream canals—one of the largest of which had been built by my great grandfather—had taken every drop of water to irrigate thirsty crops in the Upper Snake River Valley. Fortunately, there was a solution at hand. The article said, “The court having issued an order to close the headgates of certain canals having later rights, the county commissioners are making diversion of the water from the canals into the river, and it is expected that it will again flow down and supply the old canals in this locality within a few days.”

Imagine the mighty Snake River so drained of its water there were only puddles for splashing fish to try to survive in. If you’ve ever seen the torrent of water coming over Shoshone Falls in a wet spring, that probably seems all but impossible. Now, imagine that happening every year below Milner Dam. You don’t have to imagine it. You can go see the dry riverbed right below the dam during the irrigation season in all but the very wettest years. It doesn’t remain dry for long. The springs below Milner begin recharging the river almost immediately.

In this Google Earth satellite photo you can see the dry Snake River below the Milner Dam, with all the water diverted into canals to the north.

In this Google Earth satellite photo you can see the dry Snake River below the Milner Dam, with all the water diverted into canals to the north.

What I can do is give you a little peek at an early indicator that there was trouble with Idaho’s system of allocating water.

It startled me to see an article in the August 11, 1905, Idaho Republican, one of the Blackfoot Newspapers at the time. The startling headline was “Snake River Goes Dry.” Was it on the front page in a shouting font stretching all the way across beneath the banner? No, it was on page five. The headline was the same size as the body copy, albeit in bold face.

It seems that upstream canals—one of the largest of which had been built by my great grandfather—had taken every drop of water to irrigate thirsty crops in the Upper Snake River Valley. Fortunately, there was a solution at hand. The article said, “The court having issued an order to close the headgates of certain canals having later rights, the county commissioners are making diversion of the water from the canals into the river, and it is expected that it will again flow down and supply the old canals in this locality within a few days.”

Imagine the mighty Snake River so drained of its water there were only puddles for splashing fish to try to survive in. If you’ve ever seen the torrent of water coming over Shoshone Falls in a wet spring, that probably seems all but impossible. Now, imagine that happening every year below Milner Dam. You don’t have to imagine it. You can go see the dry riverbed right below the dam during the irrigation season in all but the very wettest years. It doesn’t remain dry for long. The springs below Milner begin recharging the river almost immediately.

In this Google Earth satellite photo you can see the dry Snake River below the Milner Dam, with all the water diverted into canals to the north.

In this Google Earth satellite photo you can see the dry Snake River below the Milner Dam, with all the water diverted into canals to the north.

Published on October 23, 2020 04:00

October 22, 2020

A Valentine

So, here’s a guy (me) who writes quirky little stories about Idaho history, writing about a guy who wrote quirky little stories about Idaho history. This post may eat its own tail.

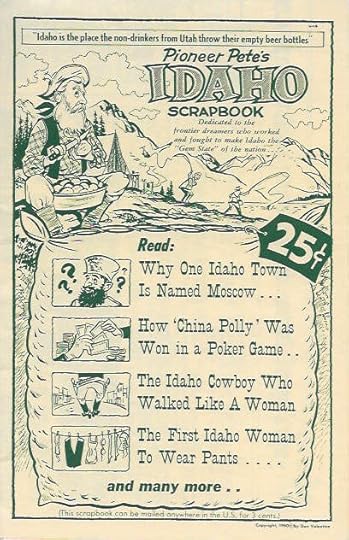

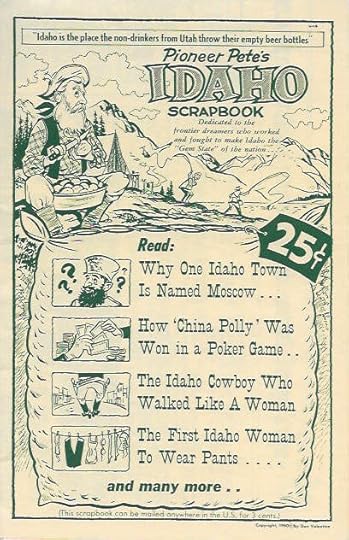

Dan Valentine wasn’t from Idaho, and he didn’t live here. Still, he was a purveyor of Idaho history, not in a scholarly sense, but in a storytelling sense. Valentine was a columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 30 years, retiring in 1980. In the 1950s and 60s, that paper was widely read in Southeastern Idaho. Enough so that Valentine included many humorous observations about the state.

Valentine published several books that grew out of his columns. They were often sold in restaurants and truck stops across Idaho and Utah. I ran across one of his publications recently while going through some family memorabilia. It’s a four-page newsletter quarter-folded into a book-sized pamphlet, called Pioneer Pete’s IDAHO Scrapbook, dated 1960. The amount of information he was able to squeeze in there is jaw-dropping. It included the story of Peg Leg Annie, a piece about Little Joe Monaghan, stories about Lana Turner, Polly Bemis, Ernest Hemingway, Diamondfield Jack, the lone parking meter in Murphy, and a dozen more. A better understanding of history has since put several of the stories into the apocryphal category, but at that time they were widely believed to be true.

Valentine’s material was featured on the Johnny Carson Show, as well as programs hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Garry Moore, and Art Linkletter.

A taste from the pamphlet:

Cats were allegedly worth $10 each in Idaho City once, because of a mouse problem.

Boise (at that time) was said to boast the only wooden cigar store Indian factory in the world.

If the state of Idaho was flattened out it would be larger than Texas.

Valentine was once accused of being a bit chauvinistic in his columns, but he’s also the guy who once said "I don't know why women would want to give up complete superiority for mere equality."

Dan Valentine passed away in 1991 at age 73.

Dan Valentine wasn’t from Idaho, and he didn’t live here. Still, he was a purveyor of Idaho history, not in a scholarly sense, but in a storytelling sense. Valentine was a columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 30 years, retiring in 1980. In the 1950s and 60s, that paper was widely read in Southeastern Idaho. Enough so that Valentine included many humorous observations about the state.

Valentine published several books that grew out of his columns. They were often sold in restaurants and truck stops across Idaho and Utah. I ran across one of his publications recently while going through some family memorabilia. It’s a four-page newsletter quarter-folded into a book-sized pamphlet, called Pioneer Pete’s IDAHO Scrapbook, dated 1960. The amount of information he was able to squeeze in there is jaw-dropping. It included the story of Peg Leg Annie, a piece about Little Joe Monaghan, stories about Lana Turner, Polly Bemis, Ernest Hemingway, Diamondfield Jack, the lone parking meter in Murphy, and a dozen more. A better understanding of history has since put several of the stories into the apocryphal category, but at that time they were widely believed to be true.

Valentine’s material was featured on the Johnny Carson Show, as well as programs hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Garry Moore, and Art Linkletter.

A taste from the pamphlet:

Cats were allegedly worth $10 each in Idaho City once, because of a mouse problem.

Boise (at that time) was said to boast the only wooden cigar store Indian factory in the world.

If the state of Idaho was flattened out it would be larger than Texas.

Valentine was once accused of being a bit chauvinistic in his columns, but he’s also the guy who once said "I don't know why women would want to give up complete superiority for mere equality."

Dan Valentine passed away in 1991 at age 73.

Published on October 22, 2020 04:00

October 21, 2020

Bigfoot

I’ll probably put my foot in it on this one. My average-sized foot.

Bigfoot was a legendary Indian. He was known for the enormous tracks he left. Those tracks were alleged to be 17 ½” long, large even for a man 6’ 6” tall. Allegedly.

Bigfoot’s tracks were said to have been seen often at the site of depredations perpetrated by indigenous people on immigrants, especially in Idaho and Oregon. He was always one step ahead of anyone trying to catch him. Stepping was part of the legend. He always walked or ran rather than ride a horse, the better to leave moccasin tracks, not doubt.

In November of 1878, The Idaho Statesman ran a sensational story about the death of Bigfoot, written by William T. Anderson of Fisherman’s Cove, Humboldt County, California, who had heard it from the man who killed him. It detailed the 16 bullets that went into Bigfoot’s body, fired by one John Wheeler, who caught up with him in Owyhee County. Both of the big man’s arms and both of his legs were broken by bullets in the fight with Wheeler. Knowing he was at death’s door, Bigfoot decided to tell Wheeler his life story. He did so in prose that Dick d’Easum who wrote about it years later for the Idaho Statesman said was packed with enough “frothy facts of his boyhood and manhood to fill a Theodore Dreiser novel.”

In the Anderson account of the death of Bigfoot, the man had an actual name. He was Starr Wilkinson, who was a lad living in the Cherokee nation when his father, a white man, was hanged for murder. His mother was of mixed blood, Negro and Cherokee. The drama of Bigfoot’s life went on for thousands of words, many of which were quite eloquent for a man gurgling them out with 16 bullet wounds in his body.

Odd that Wheeler himself never said anything about killing one of the most notorious bad men in the West. Odd that he didn’t collect the $1,000 reward on the man’s head. Wheeler had an outlaw record to his own credit. He killed a man on Wood River in 1868 and got away with it. He was sentenced to ten years in prison for a stagecoach robbery in Oregon. After leaving prison, he was eventually sentenced to hang for a murder committed during another stage robbery, this time in California.

Awaiting certain death, Wheeler wrote a series of letters to his wife, his sister, his attorney, and a girlfriend reflecting on his life. He wrote not a word about Bigfoot. His musings complete, Wheeler took poison in jail rather than face the rope and died.

Many historians discount the whole legend of Bigfoot. Dick d’Easum put it this way: “Just as nobody is ever attacked by a little bear, no pioneer of the 1860s ever lost a steer or a wife or a set of harness to a small Indian. Little Indians were sometimes caught and killed. Dead Indians had little feet. Indians that prowled and pillaged and slipped away unscathed were invariably possessed of huge trotters.”

So, if Bigfoot was a myth, why would you name a town after him? That town is Nampa, reportedly taking its name from Shoshoni words Namp (foot) and Puh (big), and by some reports named after the legendary Bigfoot. Historian Annie Laurie Bird did research on the name Nampa in 1966, concluding that it probably did come from a Shoshoni word pronounced “nambe” or “nambuh” and meaning footprint. She did not weigh in on the Bigfoot connection.

A marauding giant is such a good story that it may never die. It was good enough that Bigfoot was killed, again, in New Mexico, 14 years after he was ventilated in Owyhee County. No word on whether he was able to gasp out his life story that time.

A statue in honor of the Bigfoot legend stands on the grounds of the Fort Boise replica in Parma.

A statue in honor of the Bigfoot legend stands on the grounds of the Fort Boise replica in Parma.

Bigfoot was a legendary Indian. He was known for the enormous tracks he left. Those tracks were alleged to be 17 ½” long, large even for a man 6’ 6” tall. Allegedly.

Bigfoot’s tracks were said to have been seen often at the site of depredations perpetrated by indigenous people on immigrants, especially in Idaho and Oregon. He was always one step ahead of anyone trying to catch him. Stepping was part of the legend. He always walked or ran rather than ride a horse, the better to leave moccasin tracks, not doubt.

In November of 1878, The Idaho Statesman ran a sensational story about the death of Bigfoot, written by William T. Anderson of Fisherman’s Cove, Humboldt County, California, who had heard it from the man who killed him. It detailed the 16 bullets that went into Bigfoot’s body, fired by one John Wheeler, who caught up with him in Owyhee County. Both of the big man’s arms and both of his legs were broken by bullets in the fight with Wheeler. Knowing he was at death’s door, Bigfoot decided to tell Wheeler his life story. He did so in prose that Dick d’Easum who wrote about it years later for the Idaho Statesman said was packed with enough “frothy facts of his boyhood and manhood to fill a Theodore Dreiser novel.”

In the Anderson account of the death of Bigfoot, the man had an actual name. He was Starr Wilkinson, who was a lad living in the Cherokee nation when his father, a white man, was hanged for murder. His mother was of mixed blood, Negro and Cherokee. The drama of Bigfoot’s life went on for thousands of words, many of which were quite eloquent for a man gurgling them out with 16 bullet wounds in his body.

Odd that Wheeler himself never said anything about killing one of the most notorious bad men in the West. Odd that he didn’t collect the $1,000 reward on the man’s head. Wheeler had an outlaw record to his own credit. He killed a man on Wood River in 1868 and got away with it. He was sentenced to ten years in prison for a stagecoach robbery in Oregon. After leaving prison, he was eventually sentenced to hang for a murder committed during another stage robbery, this time in California.

Awaiting certain death, Wheeler wrote a series of letters to his wife, his sister, his attorney, and a girlfriend reflecting on his life. He wrote not a word about Bigfoot. His musings complete, Wheeler took poison in jail rather than face the rope and died.

Many historians discount the whole legend of Bigfoot. Dick d’Easum put it this way: “Just as nobody is ever attacked by a little bear, no pioneer of the 1860s ever lost a steer or a wife or a set of harness to a small Indian. Little Indians were sometimes caught and killed. Dead Indians had little feet. Indians that prowled and pillaged and slipped away unscathed were invariably possessed of huge trotters.”

So, if Bigfoot was a myth, why would you name a town after him? That town is Nampa, reportedly taking its name from Shoshoni words Namp (foot) and Puh (big), and by some reports named after the legendary Bigfoot. Historian Annie Laurie Bird did research on the name Nampa in 1966, concluding that it probably did come from a Shoshoni word pronounced “nambe” or “nambuh” and meaning footprint. She did not weigh in on the Bigfoot connection.

A marauding giant is such a good story that it may never die. It was good enough that Bigfoot was killed, again, in New Mexico, 14 years after he was ventilated in Owyhee County. No word on whether he was able to gasp out his life story that time.

A statue in honor of the Bigfoot legend stands on the grounds of the Fort Boise replica in Parma.

A statue in honor of the Bigfoot legend stands on the grounds of the Fort Boise replica in Parma.

Published on October 21, 2020 04:00