Rick Just's Blog, page 150

September 18, 2020

That Call of the Sirens

If you were a resident of Crescent City, California who was visiting Idaho and happened to be in Blackfoot, you could be forgiven if you started looking for high ground at noon.

Okay, I admit that’s a tortured way to get into a story about Blackfoot’s noon siren. At least I didn’t make references to Greek mythology and those alluring rocks.

Noon whistles were common in factory towns where it signaled a lunch break. Noon sirens served the same function. Both were once also used to summon volunteer firefighters to the station when needed, which was often not at noon.

Blackfoot’s use of a noon siren probably started in 1919. I found the following article in the September 19, 1919 edition of the (Blackfoot) Idaho Republican, headlined, Electric Siren for Noon Whistle.

“The electric siren installed by the fire department under leadership of Fire Chief Fred Simon, which is heard to lift its penetrating voice exactly at 12 o’clock of each day, is apparently meeting with satisfaction, and if no discouragers of the good idea get busy soon, Mr. Simon states that he will have the siren accepted.”

The headline implies that there might once have been a whistle in Blackfoot that the siren replaced.

The siren Blackfoot uses today is probably from the 50s. The controls are in a big orange box with a Civil Defense logo on it. The horns are on a water tower. If you’re curious what it sounds like, go to YouTube and search for Blackfoot Idaho siren. Be sure to turn the volume all the way up.

Blackfoot Fire Chief Kevin Gray says, “People live and die by it.” The automated siren sometimes gets off a bit when the station tests its generator. “We hear about it,” Gray says. “People go to lunch when they hear the noon whistle, and they come back by the clock. If the whistle is late they’ve missed a little lunch time.”

Occasional proposals to do away with the siren have been met with stiff citizen resistance, so the tradition continues.

There are probably several town where noon sirens are part of the community tradition. I’ve heard the one in Blackfoot off and on since the mid-50s. What community sirens do you know about?

Okay, I admit that’s a tortured way to get into a story about Blackfoot’s noon siren. At least I didn’t make references to Greek mythology and those alluring rocks.

Noon whistles were common in factory towns where it signaled a lunch break. Noon sirens served the same function. Both were once also used to summon volunteer firefighters to the station when needed, which was often not at noon.

Blackfoot’s use of a noon siren probably started in 1919. I found the following article in the September 19, 1919 edition of the (Blackfoot) Idaho Republican, headlined, Electric Siren for Noon Whistle.

“The electric siren installed by the fire department under leadership of Fire Chief Fred Simon, which is heard to lift its penetrating voice exactly at 12 o’clock of each day, is apparently meeting with satisfaction, and if no discouragers of the good idea get busy soon, Mr. Simon states that he will have the siren accepted.”

The headline implies that there might once have been a whistle in Blackfoot that the siren replaced.

The siren Blackfoot uses today is probably from the 50s. The controls are in a big orange box with a Civil Defense logo on it. The horns are on a water tower. If you’re curious what it sounds like, go to YouTube and search for Blackfoot Idaho siren. Be sure to turn the volume all the way up.

Blackfoot Fire Chief Kevin Gray says, “People live and die by it.” The automated siren sometimes gets off a bit when the station tests its generator. “We hear about it,” Gray says. “People go to lunch when they hear the noon whistle, and they come back by the clock. If the whistle is late they’ve missed a little lunch time.”

Occasional proposals to do away with the siren have been met with stiff citizen resistance, so the tradition continues.

There are probably several town where noon sirens are part of the community tradition. I’ve heard the one in Blackfoot off and on since the mid-50s. What community sirens do you know about?

Published on September 18, 2020 04:00

September 17, 2020

Bear Track Williams

Not all property owned by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (IDPR) is a state park. One little known site is called “Bear Track” Williams Recreation Area. Though owned by IDPR, it is managed by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. That’s because the site is primarily for fishing access.

Two parcels, totaling 480 acres, are along Hwy 93 between Carey and Richfield, near Craters of the Moon National Monument.

Ernest Hemingway’s son, Jack, donated the property to the Idaho Foundation for Parks and Lands in 1973, with the intent that they would turn it over to the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation when the donation could be used as a match for acquisition or development of state park property.

IDPR took over ownership of two parcels in 1974 and 1975.

Jack Hemingway purchased the property with the intention of making the donation and specifying that it be named for Taylor “Bear Tracks” Williams.

So, who was “Bear Tracks” Williams? He was one of several hunting and fishing guides who began working in the Wood River Valley when Averell Harriman built his famous Sun Valley Resort. The guides often found themselves rubbing shoulders with the wealthy and famous. Williams guided for Ernest Hemingway, and they became good friends. He often accompanied Hemingway to Cuba. They spent many hours together along Silver Creek and the Little Wood River.

One would assume this outdoor guide got his nickname because of his proficiency in tracking or because of some harrowing tale. Nope. He got the nickname because he walked with his toes pointed out.

“Bear Tracks” Williams Recreation Area is prized for its angling opportunities in the sagebrush desert. Fly fishing there is catch and release. There has been virtually no development on the site since Jack Hemingway donated it more than 40 years ago, which is probably just the way he would have wanted it.

Two parcels, totaling 480 acres, are along Hwy 93 between Carey and Richfield, near Craters of the Moon National Monument.

Ernest Hemingway’s son, Jack, donated the property to the Idaho Foundation for Parks and Lands in 1973, with the intent that they would turn it over to the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation when the donation could be used as a match for acquisition or development of state park property.

IDPR took over ownership of two parcels in 1974 and 1975.

Jack Hemingway purchased the property with the intention of making the donation and specifying that it be named for Taylor “Bear Tracks” Williams.

So, who was “Bear Tracks” Williams? He was one of several hunting and fishing guides who began working in the Wood River Valley when Averell Harriman built his famous Sun Valley Resort. The guides often found themselves rubbing shoulders with the wealthy and famous. Williams guided for Ernest Hemingway, and they became good friends. He often accompanied Hemingway to Cuba. They spent many hours together along Silver Creek and the Little Wood River.

One would assume this outdoor guide got his nickname because of his proficiency in tracking or because of some harrowing tale. Nope. He got the nickname because he walked with his toes pointed out.

“Bear Tracks” Williams Recreation Area is prized for its angling opportunities in the sagebrush desert. Fly fishing there is catch and release. There has been virtually no development on the site since Jack Hemingway donated it more than 40 years ago, which is probably just the way he would have wanted it.

Published on September 17, 2020 04:00

September 16, 2020

An Idaho Hero

David Bruce Bleak, born in Idaho Falls in 1932, never finished high school. After dropping out he tried his hand at farming and working for the railroad. He grew bored and decided enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1950 might provide a little excitement.

Bleak was a big man, 6 foot 5 and 250 pounds. If you saw him standing in platoon formation, you might not have readily picked him out as medic material, but the Army saw it that way. In 1952 Bleak found himself in Korea, where he was promoted to sergeant.

Sgt. Bleak was part of a patrol attached to the 2nd Battalion, 223rd Infantry. They were sent north to capture Chinese soldiers for the purpose of interrogation.

The 20-year-old soldier from Idaho and his patrol crept up a hillside where they were met with blistering enemy fire, suffering several casualties. Bleak helped the wounded, then continued to advance with his patrol.

Another man fell near the top of the hill. Three enemy troops laid down gunfire in an effort to keep the big medic from getting to the wounded soldier. That did not stop Bleak. He rushed into the trench where they were hiding and killed two enemies with his bare hands and dispatched the third with a trenching knife.

Moving out of the trench the medic saw an enemy grenade land in front of a companion. Without a thought for his own life he threw himself between the grenade and the soldier. Bleak took shrapnel to his back, but his injuries were minor.

A few minutes later a machine-gun bullet struck the young medic in the leg. Ignoring his injury, Bleak picked up a wounded man and started carrying him to safety. On his way down the hill two enemy soldiers charged with fixed bayonets. In a move that any editor would throw out if the story were fiction, Bleak grabbed the charging soldiers with his bare hands, smashing their heads together.

For his selfless heroism, David Bruce Bleak became the 61st Medal of Honor winner of the Korean War, receiving the honor from President Dwight D. Eisenhower in October, 1953.

Bleak left the Army after the war and returned to Idaho. Later he and his wife, Lois, would move to Wyoming where he would work as a meat cutter, a truck driver, and a rancher. The family-–they had four kids—moved back to Idaho where he ran a dairy farm in Moore for ten years, before taking a job as a janitor at the “site,” today called the Idaho National Laboratory. He would end his career there as chief hot cell technician, responsible for disposing of spent nuclear fuel rods.

David Bleak died in Arco in 2006 at age 74. David Bruce Bleak at his Medal of Honor Ceremony.

David Bruce Bleak at his Medal of Honor Ceremony.

Bleak was a big man, 6 foot 5 and 250 pounds. If you saw him standing in platoon formation, you might not have readily picked him out as medic material, but the Army saw it that way. In 1952 Bleak found himself in Korea, where he was promoted to sergeant.

Sgt. Bleak was part of a patrol attached to the 2nd Battalion, 223rd Infantry. They were sent north to capture Chinese soldiers for the purpose of interrogation.

The 20-year-old soldier from Idaho and his patrol crept up a hillside where they were met with blistering enemy fire, suffering several casualties. Bleak helped the wounded, then continued to advance with his patrol.

Another man fell near the top of the hill. Three enemy troops laid down gunfire in an effort to keep the big medic from getting to the wounded soldier. That did not stop Bleak. He rushed into the trench where they were hiding and killed two enemies with his bare hands and dispatched the third with a trenching knife.

Moving out of the trench the medic saw an enemy grenade land in front of a companion. Without a thought for his own life he threw himself between the grenade and the soldier. Bleak took shrapnel to his back, but his injuries were minor.

A few minutes later a machine-gun bullet struck the young medic in the leg. Ignoring his injury, Bleak picked up a wounded man and started carrying him to safety. On his way down the hill two enemy soldiers charged with fixed bayonets. In a move that any editor would throw out if the story were fiction, Bleak grabbed the charging soldiers with his bare hands, smashing their heads together.

For his selfless heroism, David Bruce Bleak became the 61st Medal of Honor winner of the Korean War, receiving the honor from President Dwight D. Eisenhower in October, 1953.

Bleak left the Army after the war and returned to Idaho. Later he and his wife, Lois, would move to Wyoming where he would work as a meat cutter, a truck driver, and a rancher. The family-–they had four kids—moved back to Idaho where he ran a dairy farm in Moore for ten years, before taking a job as a janitor at the “site,” today called the Idaho National Laboratory. He would end his career there as chief hot cell technician, responsible for disposing of spent nuclear fuel rods.

David Bleak died in Arco in 2006 at age 74.

David Bruce Bleak at his Medal of Honor Ceremony.

David Bruce Bleak at his Medal of Honor Ceremony.

Published on September 16, 2020 04:00

September 15, 2020

Stagecoaches

Stagecoaches are an icon of Westerns. They were always getting robbed and occasionally attacked by Indians. Unlike six-gun duels in the street which were largely an invention of dime novels, stagecoaches deserve their icon status.

The best known and most successful of the stagecoach companies was the Overland Stage. Stagecoaches brought passengers and supplies, but their most important cargo was mail. Ben Holladay, who ran the company, had the US Mail contract, which brought him more than a million dollars a year for a time. He built a mansion in Washington, DC just so he could lobby Congress for contracts.

Running a stage line was profitable, but it was also expensive and complicated. Holladay had to set up stage stations every 10 to 15 miles along his routes. The one that ran through Idaho started in Kansas. The stations had vast stores of shelled corn for the horses and men to take care of the animals. The Overland Stage could boast the capability of moving along at 100 miles a day, by rolling day and night. There were frequent delays, like the ones that ended up in the movies.

Newspapers depended on the arrival of other newspapers from across the country to supplement their local editions. On August 2, 1864, the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman published a story under the standing head "By Overland Stage." It explained the delay in getting news from the company by listing some of the issues coaches had run into in recent days. About 100 miles out of Denver Indians had stolen all the Overland Stage Livestock. A stage near Fort Bridger, Wyoming had also been stopped by Indians. A third stage was attacked near Platte Bridge.

The coaches were comfortable when compared with walking. All the Overland Stages were built on a standard pattern called The Concord Coach. They had heavy leather springs and were pulled by four or six horses. Passengers piled in and piled on. The company was all about profit, so they didn’t necessarily go on a schedule. They would often wait until a stage was full of people and supplies. The picture shows a stagecoach (perhaps not an Overland) on a road along the Snake River Canyon near Twin Falls. It is one of the Idaho State Historical Society’s photos from the Bisbee collection.

As important as they were, stagecoaches roamed the West for a fairly short time. The Overland Stage Company, which made Holladay a fortune, lasted about ten years. Holladay transitioned to railroads, which is the way the mail went. He lost most of his fortune trying to run trains.

The best known and most successful of the stagecoach companies was the Overland Stage. Stagecoaches brought passengers and supplies, but their most important cargo was mail. Ben Holladay, who ran the company, had the US Mail contract, which brought him more than a million dollars a year for a time. He built a mansion in Washington, DC just so he could lobby Congress for contracts.

Running a stage line was profitable, but it was also expensive and complicated. Holladay had to set up stage stations every 10 to 15 miles along his routes. The one that ran through Idaho started in Kansas. The stations had vast stores of shelled corn for the horses and men to take care of the animals. The Overland Stage could boast the capability of moving along at 100 miles a day, by rolling day and night. There were frequent delays, like the ones that ended up in the movies.

Newspapers depended on the arrival of other newspapers from across the country to supplement their local editions. On August 2, 1864, the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman published a story under the standing head "By Overland Stage." It explained the delay in getting news from the company by listing some of the issues coaches had run into in recent days. About 100 miles out of Denver Indians had stolen all the Overland Stage Livestock. A stage near Fort Bridger, Wyoming had also been stopped by Indians. A third stage was attacked near Platte Bridge.

The coaches were comfortable when compared with walking. All the Overland Stages were built on a standard pattern called The Concord Coach. They had heavy leather springs and were pulled by four or six horses. Passengers piled in and piled on. The company was all about profit, so they didn’t necessarily go on a schedule. They would often wait until a stage was full of people and supplies. The picture shows a stagecoach (perhaps not an Overland) on a road along the Snake River Canyon near Twin Falls. It is one of the Idaho State Historical Society’s photos from the Bisbee collection.

As important as they were, stagecoaches roamed the West for a fairly short time. The Overland Stage Company, which made Holladay a fortune, lasted about ten years. Holladay transitioned to railroads, which is the way the mail went. He lost most of his fortune trying to run trains.

Published on September 15, 2020 04:00

September 14, 2020

This will Sweep You Away

Your broom was brought to you by Benjamin Franklin. Probably. More on that in a bit.

A broom is an essential device for household cleaning. Brooms have been around for centuries, changing very little, and are still as useful as ever. When the first domestic vacuum cleaners appeared around 1905, one might have assumed the days of brooms were numbered. That portable suction device did become indispensable, yet the vacuum did not supplant the broom the way the automobile supplanted the horse and buggy.

But, let’s not get sucked into the vacuum story. This post is about brooms, specifically the brooms of Boise.

The broom business in Boise started in a small way in 1875 when Mr. Douglass Markham, a blind man, harvested a small crop of broom corn near Middleton and cobbled together a few brooms for sale. The Idaho Statesman noted that local brooms could sell for 25 cents less than imported brooms and opined that “Any man who will engage in the business extensively enough to supply the trade will soon make a nice little fortune.” The paper estimated that the fledgling territory could use 2,000 brooms a year.

By 1879 the Idaho Statesman was regularly running an ad for brooms placed by one Jacob Meyer, boasting that his brooms “have the best quality of bright, healthy broom corn, nicely turned handles, firmly bound with wire, and are strong and durable.”

Broom corn is a type of sorghum that features fibrous seed branches that can be as long as 36 inches. Table corn originated in the Americas, but broomcorn has its roots (figuratively) in central Africa. It spread all over the Mediterranean during the Dark Ages. So, one tick in the positive column for the Dark Ages, I guess.

But what about Ben? According to an 1899 article in the Idaho Statesman (and numerous other sources), Franklin “should be the patron saint of housewives.” Let me quickly add that husbands have also been known to master sweeping. The Statesman article said that there was “a very pleasant little fairy story concerning Benjamin Franklin… The story goes that Dr. Franklin was examining a whisk broom that had been brought over from England. He found a single seed on the broom, picked it off, planted it, and raised a stalk of corn from which is descended all the broom corn of the United States.”

At one time there were several hundred broom factories scattered around the country. As with most manufacturing the operations consolidated into Big Broom, so to speak. Today there has been a bit of a renaissance in broom making. It has become something of an artisanal occupation in many places.

A broom is an essential device for household cleaning. Brooms have been around for centuries, changing very little, and are still as useful as ever. When the first domestic vacuum cleaners appeared around 1905, one might have assumed the days of brooms were numbered. That portable suction device did become indispensable, yet the vacuum did not supplant the broom the way the automobile supplanted the horse and buggy.

But, let’s not get sucked into the vacuum story. This post is about brooms, specifically the brooms of Boise.

The broom business in Boise started in a small way in 1875 when Mr. Douglass Markham, a blind man, harvested a small crop of broom corn near Middleton and cobbled together a few brooms for sale. The Idaho Statesman noted that local brooms could sell for 25 cents less than imported brooms and opined that “Any man who will engage in the business extensively enough to supply the trade will soon make a nice little fortune.” The paper estimated that the fledgling territory could use 2,000 brooms a year.

By 1879 the Idaho Statesman was regularly running an ad for brooms placed by one Jacob Meyer, boasting that his brooms “have the best quality of bright, healthy broom corn, nicely turned handles, firmly bound with wire, and are strong and durable.”

Broom corn is a type of sorghum that features fibrous seed branches that can be as long as 36 inches. Table corn originated in the Americas, but broomcorn has its roots (figuratively) in central Africa. It spread all over the Mediterranean during the Dark Ages. So, one tick in the positive column for the Dark Ages, I guess.

But what about Ben? According to an 1899 article in the Idaho Statesman (and numerous other sources), Franklin “should be the patron saint of housewives.” Let me quickly add that husbands have also been known to master sweeping. The Statesman article said that there was “a very pleasant little fairy story concerning Benjamin Franklin… The story goes that Dr. Franklin was examining a whisk broom that had been brought over from England. He found a single seed on the broom, picked it off, planted it, and raised a stalk of corn from which is descended all the broom corn of the United States.”

At one time there were several hundred broom factories scattered around the country. As with most manufacturing the operations consolidated into Big Broom, so to speak. Today there has been a bit of a renaissance in broom making. It has become something of an artisanal occupation in many places.

Published on September 14, 2020 04:00

September 13, 2020

Not that Moscow

Idaho has some lofty place names that would seem to honor much larger and better-known places. Paris is one of those. If you’re expecting an Eiffel Tower, you’re not likely to find one. The name Paris came from the man who platted the town. His name was Frederick Perris. How the name morphed into the spelling that place in France uses is unknown. The U.S. Postal Service is more often the culprit in such cases, having a long history of “correcting” the spelling of post office names.

That happened to a place called Moscow. No, not the one in Idaho. I’ll get to that in a minute. Moscow, Kansas, one of more than 20 Moscows in the U.S., was honoring a Spanish conquistador named Luis de Moscoso, according to a story on the PRI website about the naming of the Moscow cities across the country. For some reason, they wanted to shorten the name to Mosco. A postal person in DC may have thought Kansans simply didn’t know how to spell, so he helpfully added the W, and it officially became Moscow.

None of the Moscows seem ready to claim a Russian connection. The one we know best was allegedly named by Samuel Miles Neff, who owned the first general store there. In that story, Neff had lived in Moscow, Pennsylvania, and Moscow, Iowa, so why not live in another Moscow, this time in Idaho.

There is at least one Idaho town that gets its name, more or less, from the city you would expect. Atlanta was named for a nearby gold discovery that was called Atlanta. It was named after the Battle of Atlanta. News of Sherman’s victory there came about the same time gold was discovered, according to Lalia Boone’s book, Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary.

That happened to a place called Moscow. No, not the one in Idaho. I’ll get to that in a minute. Moscow, Kansas, one of more than 20 Moscows in the U.S., was honoring a Spanish conquistador named Luis de Moscoso, according to a story on the PRI website about the naming of the Moscow cities across the country. For some reason, they wanted to shorten the name to Mosco. A postal person in DC may have thought Kansans simply didn’t know how to spell, so he helpfully added the W, and it officially became Moscow.

None of the Moscows seem ready to claim a Russian connection. The one we know best was allegedly named by Samuel Miles Neff, who owned the first general store there. In that story, Neff had lived in Moscow, Pennsylvania, and Moscow, Iowa, so why not live in another Moscow, this time in Idaho.

There is at least one Idaho town that gets its name, more or less, from the city you would expect. Atlanta was named for a nearby gold discovery that was called Atlanta. It was named after the Battle of Atlanta. News of Sherman’s victory there came about the same time gold was discovered, according to Lalia Boone’s book, Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary.

Published on September 13, 2020 04:00

September 12, 2020

The Biking Boys of Boise

Bicycling was all the rage in 1901. Of particular interest was the racing of tandem bicycles. Teams from all over the country were setting out to set or break records.

On April 9 the Idaho Statesman ran a story headlined, “Two Young Men of This City Will Ride Their Bike to Buffalo.” Riding to Buffalo, New York would be arduous for today’s bike riders on today’s paved roads. In 1901 there were paved roads, mostly in cities, but the young men were going to be riding on a lot of dirt roads better fit for wagons.

The bicyclists were Roy Pendelton, a barber, and Ira King, who worked at the Idanha Hotel. They got themselves a Tribune Tandem, much like the one pictured, and hoped their trip would reap rewards from the bicycle company. They expected to leave Boise in early June and take 25 days to travel the 2300 miles to Buffalo. Once they crossed the Rocky Mountains, they expected to make 150 to 175 miles a day.

Pendleton had considerable experience as a bicycle racer. Alas, the pair only made it as far as Wyoming before giving up their quest.

On April 9 the Idaho Statesman ran a story headlined, “Two Young Men of This City Will Ride Their Bike to Buffalo.” Riding to Buffalo, New York would be arduous for today’s bike riders on today’s paved roads. In 1901 there were paved roads, mostly in cities, but the young men were going to be riding on a lot of dirt roads better fit for wagons.

The bicyclists were Roy Pendelton, a barber, and Ira King, who worked at the Idanha Hotel. They got themselves a Tribune Tandem, much like the one pictured, and hoped their trip would reap rewards from the bicycle company. They expected to leave Boise in early June and take 25 days to travel the 2300 miles to Buffalo. Once they crossed the Rocky Mountains, they expected to make 150 to 175 miles a day.

Pendleton had considerable experience as a bicycle racer. Alas, the pair only made it as far as Wyoming before giving up their quest.

Published on September 12, 2020 04:00

September 11, 2020

Jimmy the Stiff, Revisited

This all started for me when I saw a photo of James Hogan and a brief story about his tragic life in the book

Legendary Locals of Boise

, by Barbara Perry Bauer and Elizabeth Jacox. I decided to do a little research on the man. Sifting through old papers I found story after story, most numbingly familiar.

In September of 1880, the Idaho World, which was published in Idaho City, said that “James Hogan, better known as Hogan the Gambler, was brought before a probate judge on a charge of stealing four hundred cigars. The judge fined Hogan $100 and gave him twenty-five days in jail for silent meditation on the fact that “Honesty is the best policy.”

Then, in March of, 1883, the same newspaper quoted Hogan as saying, “When I’ve money, I’m Hogan the Gambler; but when I’m broke I’m Hogan the shtiff!”

The Statesman first mentioned Hogan in January 1888. The article read, “Hogan the stiff;” as the city marshal calls him, has been locked up in the city jail for the past three or four days. He was drunk and disorderly at various times and places and hence locked up until he became sobered.”

In 1889, Jimmy made the paper twice. Both stories were in a faux formal style. In October, the report was that “Friday evening, Officer Haas invited Mr. Hogan of this city, to pass the night in the city lodging house on Eighth Street. The invitation was accepted in the spirit in which it was tendered.” The “lodging house” on Eighth was the city jail.

Then, just a month later there appeared the following: “A celebrity known here as Hogan has been the guest of the city and entertained for several weeks past at the city lodging house on Eighth street, left the city on the Idaho Central passenger train Wednesday evening for Nampa, where he took the west bound train of the Oregon Short Line for Tilamock Head and points further west. Mr. Hogan had intimated to the City Marshal that he needed a change of scene and diet, when “Old Nick” very courteously and kindly escorted him to the railroad depot on the other side of the river, where both took the train for Nampa. At Nampa, the parting scene took place, Mr. Hogan promising the marshal that he would write to him and to all his friends in Boise as soon as he reached his destination. “

Hogan stayed out of trouble, or perhaps, stayed out of Boise for about a year. A thorough search of other newspapers might locate him. In October, 1891 the Statesman reported simply that “Hogan the Stiff got drunk again yesterday and was taken in by Marshall Nicholson.’

In 1892, he got four mentions in the paper. He paid a $9 fine, served 20 days in jail for stealing a coat from a restaurant, was called by the Statesman “Boise’s boss boozer,’ and shipped out as the cook for the Idaho National Guard, which had been dispatched to Wallace to quell the union troubles in the mines up there. It was the fond hope of some in Boise that the guard would forget to bring him back home when they returned. The boys liked his cooking. They took up a collection to get him a new suit of clothes, and when they returned to Boise, James Hogan came back with them.

1894 was a banner year for James Hogan. A blurb said, “It is only a matter of time until Hogan the stiff will become a permanent county charge. He was only recently discharged from the county jail after serving a lengthy sentence for vagrancy, and yesterday Judge Clark sent him up for 70 days on the same charge.

A little later the Statesman reported that “Hogan, Boise’s veteran “bummer,” has been sent to the poor farm. Hogan said the only objection he had to going to the farm was because there were too many bums there. He didn’t like to associate with them.

A 90-day sentence. A 70-day sentence. The math was daunting for Jimmy in 1894. He would sometimes be out less than a day before being arrested again that year. Then there were the stolen shoes. Another inmate escaped with Hogan’s shoes. Jimmy commented that that’s what one gets for associating with a depraved set of men.

His big year was topped off when the Caldwell Tribune reported that “While Hogan the Stiff was delivering a speech against the Republican party on Main Street at a late hour Wednesday night he was shot at and barely missed, the bullet striking within a few feet of him.” The report came out on Christmas Day, so 1894 was about over.

James Hogan was usually listed as a cook, and sometimes as a waiter. He apparently also worked for a time at the Idaho statehouse, possibly as a janitor.

Hogan was political, in a ranting-at-the-Republicans sort of way. He was one of many prisoners who signed a petition for a breakaway group of Democrats while in jail. In 1896 Hogan expressed his regrets from jail that he would not be able to help Democratic electors. One wonders if that feeling was mutual.

In 1897 Hogan was in the paper as the victim of crime, not as a low-level perpetrator. One John Murphy was arrested for robbing Hogan. The paper couldn’t resist a dig, saying “No one would suppose that Hogan would have money for anyone to steal, but it is said he has been working and recently came into town with considerable cash.” Later that year, he was back in jail for being a common drunkard. He caused some mirth in the courtroom speaking in his own defense when he accused witnesses of being “worse drunkards nor he had been.”

Over the next ten years, Hogan was arrested at least 41 times, and the Statesman duly reported each instance.

I’ll just tell you about a couple. In 1900 a convention came to town. Conventioneers were each given a little badge that said Freedom of the City. About the time the convention broke up, Jimmy had been released from jail and told to leave town within 24 hours. But he found one of those Freedom of the City badges, pinned it on, and proceeded to act like it meant something. He said it was now “without the power of man to arrest him or otherwise deprive him of his liberty.” Jimmy was prone to make windy speeches about politics when he was well-lubricated, and this day he stationed himself on Main street and began to pontificate. To his surprise he felt the strong hand of the law on his collar and was whisked away to jail, protesting about the injustice all the way because, after all, he was wearing that pin. He got another 60 days for that one.

In 1903, the Statesman ran an unusually lengthy article about Hogan, pointing out that he had spent seven months of the past year in jail on long sentences, and that didn’t count the several short stints when he was there to just sleep it off.

In 1907 Hogan threw a brick at a phonograph in a tobacco store on Main Street, destroying it. He said the voices coming from the machine were calling him names.

That same year, in September, the headline was “Happy J. Hogan Leaves County Jail.” After serving his “forty-eleventh term in jail” Hogan had packed up his grip but left it with the deputy to take care of, saying he might as well keep it at the jail since he spent more time there than anywhere else.

Upon his departure deputies were watching him walk down the street. He turned and said, “Goodbye to ye, byes; don’t cry for me departure. Hogan the stiff will never desar-rt year. I’ll be back soon; never fear.”

The article ended with the line, “And he is expected.”

But he did not come back. The October 2, 1907 issue of the Statesman had a story about Hogan with a different tone. Hogan had passed away. No more Hogan the stiff, in this story. It read, “The deceased was about 65 years of age and resided in and around Boise for at least 30 years. He was a well-known character and friend to everybody in his humble way, while all who knew him were his friends. In late years it was through friendship that Hogan lived. Many gave him money and he was seldom found without some change in his pockets.”

The paper went on to say that many who had given him money to buy food would make up a purse to defray funeral expenses, and a special fund was being collected to buy flowers.

A crude concrete headstone marked his grave for 111 years. You’d have to get down on your hands and knees to read it.

I included a picture of his gravesite from the Find a Grave website when I first wrote about Jimmy in 2018. The photographer had tossed a red file folder over the little headstone to mark his grave for the photo. When people saw that, someone suggest that we get him a nice grave marker.

I did a little Go Fund Me campaign and in three or four days we had enough for an engraved stone marker, thanks to the generosity of Boise Valley Monument.

I’ll end this by explaining why the marker says what it does. You’d expect the dates of birth and death, of course. The epitaph is because of yet another Statesman article about Jimmy. The headline said “Just Plain Jimmy.” They quoted him saying to a reporter “Whin ye go up there to the Statesman office and write this up, please it jist plain Jimmy, and not Hogan the Stiff.

So, 111 years later, Jimmy got his wish. A toast to Just Plain Jimmy, 2018.

That's James Hogan on the left standing for a photo with the Idaho Legislature. He worked as a janitor in the capitol at one time. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society

That's James Hogan on the left standing for a photo with the Idaho Legislature. He worked as a janitor in the capitol at one time. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society

In September of 1880, the Idaho World, which was published in Idaho City, said that “James Hogan, better known as Hogan the Gambler, was brought before a probate judge on a charge of stealing four hundred cigars. The judge fined Hogan $100 and gave him twenty-five days in jail for silent meditation on the fact that “Honesty is the best policy.”

Then, in March of, 1883, the same newspaper quoted Hogan as saying, “When I’ve money, I’m Hogan the Gambler; but when I’m broke I’m Hogan the shtiff!”

The Statesman first mentioned Hogan in January 1888. The article read, “Hogan the stiff;” as the city marshal calls him, has been locked up in the city jail for the past three or four days. He was drunk and disorderly at various times and places and hence locked up until he became sobered.”

In 1889, Jimmy made the paper twice. Both stories were in a faux formal style. In October, the report was that “Friday evening, Officer Haas invited Mr. Hogan of this city, to pass the night in the city lodging house on Eighth Street. The invitation was accepted in the spirit in which it was tendered.” The “lodging house” on Eighth was the city jail.

Then, just a month later there appeared the following: “A celebrity known here as Hogan has been the guest of the city and entertained for several weeks past at the city lodging house on Eighth street, left the city on the Idaho Central passenger train Wednesday evening for Nampa, where he took the west bound train of the Oregon Short Line for Tilamock Head and points further west. Mr. Hogan had intimated to the City Marshal that he needed a change of scene and diet, when “Old Nick” very courteously and kindly escorted him to the railroad depot on the other side of the river, where both took the train for Nampa. At Nampa, the parting scene took place, Mr. Hogan promising the marshal that he would write to him and to all his friends in Boise as soon as he reached his destination. “

Hogan stayed out of trouble, or perhaps, stayed out of Boise for about a year. A thorough search of other newspapers might locate him. In October, 1891 the Statesman reported simply that “Hogan the Stiff got drunk again yesterday and was taken in by Marshall Nicholson.’

In 1892, he got four mentions in the paper. He paid a $9 fine, served 20 days in jail for stealing a coat from a restaurant, was called by the Statesman “Boise’s boss boozer,’ and shipped out as the cook for the Idaho National Guard, which had been dispatched to Wallace to quell the union troubles in the mines up there. It was the fond hope of some in Boise that the guard would forget to bring him back home when they returned. The boys liked his cooking. They took up a collection to get him a new suit of clothes, and when they returned to Boise, James Hogan came back with them.

1894 was a banner year for James Hogan. A blurb said, “It is only a matter of time until Hogan the stiff will become a permanent county charge. He was only recently discharged from the county jail after serving a lengthy sentence for vagrancy, and yesterday Judge Clark sent him up for 70 days on the same charge.

A little later the Statesman reported that “Hogan, Boise’s veteran “bummer,” has been sent to the poor farm. Hogan said the only objection he had to going to the farm was because there were too many bums there. He didn’t like to associate with them.

A 90-day sentence. A 70-day sentence. The math was daunting for Jimmy in 1894. He would sometimes be out less than a day before being arrested again that year. Then there were the stolen shoes. Another inmate escaped with Hogan’s shoes. Jimmy commented that that’s what one gets for associating with a depraved set of men.

His big year was topped off when the Caldwell Tribune reported that “While Hogan the Stiff was delivering a speech against the Republican party on Main Street at a late hour Wednesday night he was shot at and barely missed, the bullet striking within a few feet of him.” The report came out on Christmas Day, so 1894 was about over.

James Hogan was usually listed as a cook, and sometimes as a waiter. He apparently also worked for a time at the Idaho statehouse, possibly as a janitor.

Hogan was political, in a ranting-at-the-Republicans sort of way. He was one of many prisoners who signed a petition for a breakaway group of Democrats while in jail. In 1896 Hogan expressed his regrets from jail that he would not be able to help Democratic electors. One wonders if that feeling was mutual.

In 1897 Hogan was in the paper as the victim of crime, not as a low-level perpetrator. One John Murphy was arrested for robbing Hogan. The paper couldn’t resist a dig, saying “No one would suppose that Hogan would have money for anyone to steal, but it is said he has been working and recently came into town with considerable cash.” Later that year, he was back in jail for being a common drunkard. He caused some mirth in the courtroom speaking in his own defense when he accused witnesses of being “worse drunkards nor he had been.”

Over the next ten years, Hogan was arrested at least 41 times, and the Statesman duly reported each instance.

I’ll just tell you about a couple. In 1900 a convention came to town. Conventioneers were each given a little badge that said Freedom of the City. About the time the convention broke up, Jimmy had been released from jail and told to leave town within 24 hours. But he found one of those Freedom of the City badges, pinned it on, and proceeded to act like it meant something. He said it was now “without the power of man to arrest him or otherwise deprive him of his liberty.” Jimmy was prone to make windy speeches about politics when he was well-lubricated, and this day he stationed himself on Main street and began to pontificate. To his surprise he felt the strong hand of the law on his collar and was whisked away to jail, protesting about the injustice all the way because, after all, he was wearing that pin. He got another 60 days for that one.

In 1903, the Statesman ran an unusually lengthy article about Hogan, pointing out that he had spent seven months of the past year in jail on long sentences, and that didn’t count the several short stints when he was there to just sleep it off.

In 1907 Hogan threw a brick at a phonograph in a tobacco store on Main Street, destroying it. He said the voices coming from the machine were calling him names.

That same year, in September, the headline was “Happy J. Hogan Leaves County Jail.” After serving his “forty-eleventh term in jail” Hogan had packed up his grip but left it with the deputy to take care of, saying he might as well keep it at the jail since he spent more time there than anywhere else.

Upon his departure deputies were watching him walk down the street. He turned and said, “Goodbye to ye, byes; don’t cry for me departure. Hogan the stiff will never desar-rt year. I’ll be back soon; never fear.”

The article ended with the line, “And he is expected.”

But he did not come back. The October 2, 1907 issue of the Statesman had a story about Hogan with a different tone. Hogan had passed away. No more Hogan the stiff, in this story. It read, “The deceased was about 65 years of age and resided in and around Boise for at least 30 years. He was a well-known character and friend to everybody in his humble way, while all who knew him were his friends. In late years it was through friendship that Hogan lived. Many gave him money and he was seldom found without some change in his pockets.”

The paper went on to say that many who had given him money to buy food would make up a purse to defray funeral expenses, and a special fund was being collected to buy flowers.

A crude concrete headstone marked his grave for 111 years. You’d have to get down on your hands and knees to read it.

I included a picture of his gravesite from the Find a Grave website when I first wrote about Jimmy in 2018. The photographer had tossed a red file folder over the little headstone to mark his grave for the photo. When people saw that, someone suggest that we get him a nice grave marker.

I did a little Go Fund Me campaign and in three or four days we had enough for an engraved stone marker, thanks to the generosity of Boise Valley Monument.

I’ll end this by explaining why the marker says what it does. You’d expect the dates of birth and death, of course. The epitaph is because of yet another Statesman article about Jimmy. The headline said “Just Plain Jimmy.” They quoted him saying to a reporter “Whin ye go up there to the Statesman office and write this up, please it jist plain Jimmy, and not Hogan the Stiff.

So, 111 years later, Jimmy got his wish. A toast to Just Plain Jimmy, 2018.

That's James Hogan on the left standing for a photo with the Idaho Legislature. He worked as a janitor in the capitol at one time. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society

That's James Hogan on the left standing for a photo with the Idaho Legislature. He worked as a janitor in the capitol at one time. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society

Published on September 11, 2020 04:00

September 10, 2020

The Intermountain Institute

The Intermountain Institute in Weiser was a boarding school established in the fall of 1899 to provide children who lived too far from a high school a chance at an education. The school’s motto was “An education and trade for every boy and girl who is willing to work for them.” Children worked five hours a day to help pay for their tuition, board, and room.

About 2,000 students got their education there before the ravages of the Great Depression forced it to close in 1933.

To architects, one feature of the campus buildings is worth note. All but one of the structures, a carriage house, were made of reinforced cast concrete. Concrete was a common building material in early Idaho, but it was used mostly in block form.

The buildings at the Intermountain Institute still had some style. The surfaces of the neo-classical buildings were scored to resemble masonry joints. This can be seen in the photo below of the laundry building under construction.

The Weiser School District used campus buildings until 1967 when a new high school was built. Hooker Hall, a three-story building with a five-story clock tower, became the county museum in the 1980s. In 1994 a fire caused much damage, and the building is still under renovation. Or, perhaps that's finished by now. Some loyal reader will let me know.

About 2,000 students got their education there before the ravages of the Great Depression forced it to close in 1933.

To architects, one feature of the campus buildings is worth note. All but one of the structures, a carriage house, were made of reinforced cast concrete. Concrete was a common building material in early Idaho, but it was used mostly in block form.

The buildings at the Intermountain Institute still had some style. The surfaces of the neo-classical buildings were scored to resemble masonry joints. This can be seen in the photo below of the laundry building under construction.

The Weiser School District used campus buildings until 1967 when a new high school was built. Hooker Hall, a three-story building with a five-story clock tower, became the county museum in the 1980s. In 1994 a fire caused much damage, and the building is still under renovation. Or, perhaps that's finished by now. Some loyal reader will let me know.

Published on September 10, 2020 04:00

September 9, 2020

The Concerns of 1890

In case you needed a reminder that things were a little different in 1890 from today, I pulled a few advertisements from a single page from the November 14, 1890 edition of the Idaho Statesman, so you could ponder what may have been on the minds of Boise residents in that first year of statehood.

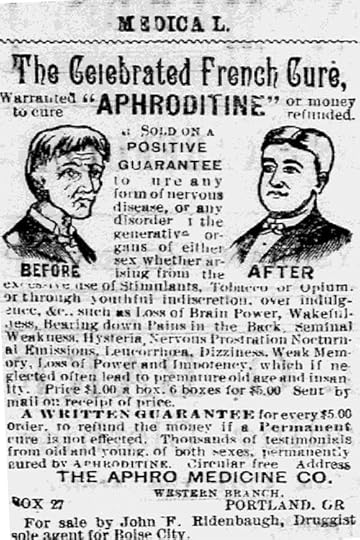

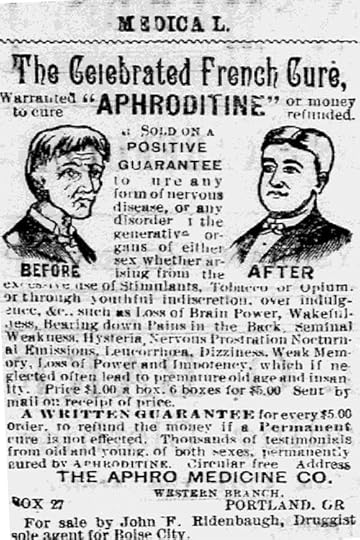

Ailments and maladies, mostly. It seems one could cure about anything by downing the right elixir. “The Celebrated French Cure,” called Aphroditine was guaranteed to “cure any form of nervous disease, or any disorder in the generative organs of either sex whether arising from the excessive use of stimulants, tobacco or opium.” Symptoms of the afflictions of those stimulants included loss of brain power, wakefulness, dizziness, and weak memory.

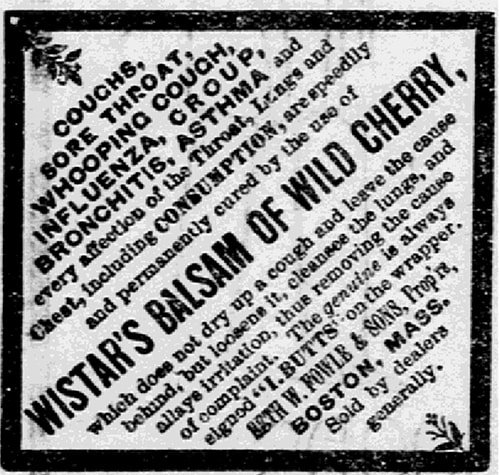

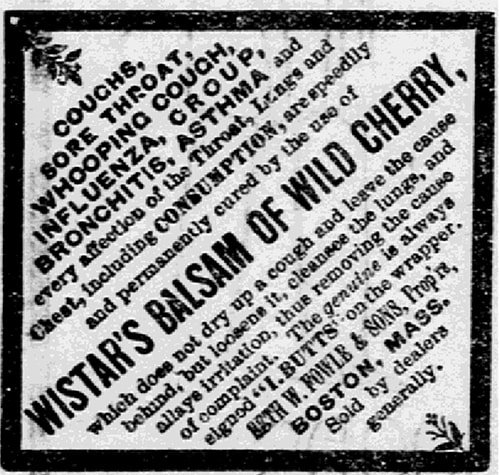

Whatever could not be cured by Aphroditine would surely fall to the powers of Wistar’s Balsam of Wild Cherry. It was said to clear up bronchitis, asthma, croup, influenza, whooping cough, and even consumption (tuberculosis). COVID-19 would doubtless be added to that list today.

For less deadly but still worrisome problems, one could turn to Skookum Root Hair Grower. It prevented baldness and even grew hair on bald heads if you used it religiously. The manufacturer was happy to note that the product “Contains no Mineral or Vegetable Poisons.”

Once your head was safely haired, you’d want to take care of your feet. Idaho Saddlery Company was happy to supply you with $3 shoes, if you were a man. You might even get a pair for $2 if you were a lady.

Assuming you had cured your weak mind, fixed your little hair loss problem, and shined up your shoes, you’d probably want to go courting. Successful courters would want to have the option of pulling those shades. To avoid catastrophe, you’d want none other than Hartshorn’s Self-Acting Shade Rollers. No need to accept imitations when every roller was autographed.

Ailments and maladies, mostly. It seems one could cure about anything by downing the right elixir. “The Celebrated French Cure,” called Aphroditine was guaranteed to “cure any form of nervous disease, or any disorder in the generative organs of either sex whether arising from the excessive use of stimulants, tobacco or opium.” Symptoms of the afflictions of those stimulants included loss of brain power, wakefulness, dizziness, and weak memory.

Whatever could not be cured by Aphroditine would surely fall to the powers of Wistar’s Balsam of Wild Cherry. It was said to clear up bronchitis, asthma, croup, influenza, whooping cough, and even consumption (tuberculosis). COVID-19 would doubtless be added to that list today.

For less deadly but still worrisome problems, one could turn to Skookum Root Hair Grower. It prevented baldness and even grew hair on bald heads if you used it religiously. The manufacturer was happy to note that the product “Contains no Mineral or Vegetable Poisons.”

Once your head was safely haired, you’d want to take care of your feet. Idaho Saddlery Company was happy to supply you with $3 shoes, if you were a man. You might even get a pair for $2 if you were a lady.

Assuming you had cured your weak mind, fixed your little hair loss problem, and shined up your shoes, you’d probably want to go courting. Successful courters would want to have the option of pulling those shades. To avoid catastrophe, you’d want none other than Hartshorn’s Self-Acting Shade Rollers. No need to accept imitations when every roller was autographed.

Published on September 09, 2020 04:00