Rick Just's Blog, page 154

August 9, 2020

The Almo Massacre Monument

So, here’s the story, as commemorated on an Idaho-shaped marker in the tiny Idaho town of Almo. “Dedicated to the memory of those who lost their lives in a horrible Indian Massacre, 1861. Three hundred immigrants west bound. Only five escaped. –Erected by S & D of Idaho Pioneers, 1938.”

I’m always a little peeved when someone depicts the shape of Idaho from memory, getting it a little wrong. This monument stretches the state from east to west, giving it a fat panhandle hardly worthy of the name. But that’s the least of the issues with this monument. The number of pioneers killed is a little off. By 300.

The earliest recorded mention of what would have been about the worst massacre ever in the old West was in 1927. That was 66 years after it was supposed to have taken place.

A 1937 article in the Idaho Statesman about the effort to erect a monument at the site noted that, “Idaho’s written histories, for some reason, say little or nothing of the Almo Massacre.”

Esteemed historian Brigham Madsen decided to look into the massacre. Madsen was a meticulous researcher and truth seeker. He checked newspapers of the time, which typically carried every clash between Indians and settlers with practiced sensationalism. Nada. He checked records from the War Department, the Indian Service, and state and territorial records. Zip.

His conclusion was that there was no such incident. So why did the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers put up the monument? In his opinion, it came about when a couple of area newspapers came up with something called “Exploration Day” in 1938. It was meant to bring tourists to Almo to gawk at City of Rocks, a nearby area of rock pinnacles that stands well enough on its own grandeur, thank you very much, and needs no help from a monument.

The promotion seemed to work, though President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent his regrets when invited to the unveiling of the monument. In 1939, the Statesman carried a detailed account of the massacre, notably starting with this paragraph: “Public interest in the City of Rocks near Oakley was revived recently by the second official exploration. Efforts to have the area designated as a national monument are progressing.” The detailed account gave practically a blow-by-blow description of the massacre, leaving out only the names of a single person who died there or the names of any of the five survivors.

So where did all the detail about the massacre come from? I found the account in a book called Six Decades Back, by Charles Shirley Walgamott, published first by Caxton in 1936 and republished by University of Idaho Press in 1990. Many of the newspaper accounts are lifted word for word from the book. Walgamott relied on the memory of W.M. E. Johnston who was a 12-year-old living in Ogden, Utah at the time of the alleged massacre. He remembered stories about the event from that time. About a dozen years later he and his family moved to the Almo area and began farming at the massacre site. He claimed they often plowed up old coins, pistols, and other evidence that it had taken place.

Merle Wells and other historians at the Idaho State Historical Society agreed with Madsen that the event never happened, and in the mid-1990s they proposed to take the stone down in the interest of accuracy. The residents of Almo were not at all thrilled with that idea. They had grown up hearing the story of the Almo Massacre. It was part of their cultural fabric. So, the stone stayed in place.

So did the City of Rocks. It should be on your bucket list to see the City of Rocks National Reserve, now jointly managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service. While you’re there, check out Castle Rocks State Park. Oh, and that monument, if you’re curious.

The Almo Massacre monument.

The Almo Massacre monument.

I’m always a little peeved when someone depicts the shape of Idaho from memory, getting it a little wrong. This monument stretches the state from east to west, giving it a fat panhandle hardly worthy of the name. But that’s the least of the issues with this monument. The number of pioneers killed is a little off. By 300.

The earliest recorded mention of what would have been about the worst massacre ever in the old West was in 1927. That was 66 years after it was supposed to have taken place.

A 1937 article in the Idaho Statesman about the effort to erect a monument at the site noted that, “Idaho’s written histories, for some reason, say little or nothing of the Almo Massacre.”

Esteemed historian Brigham Madsen decided to look into the massacre. Madsen was a meticulous researcher and truth seeker. He checked newspapers of the time, which typically carried every clash between Indians and settlers with practiced sensationalism. Nada. He checked records from the War Department, the Indian Service, and state and territorial records. Zip.

His conclusion was that there was no such incident. So why did the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers put up the monument? In his opinion, it came about when a couple of area newspapers came up with something called “Exploration Day” in 1938. It was meant to bring tourists to Almo to gawk at City of Rocks, a nearby area of rock pinnacles that stands well enough on its own grandeur, thank you very much, and needs no help from a monument.

The promotion seemed to work, though President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent his regrets when invited to the unveiling of the monument. In 1939, the Statesman carried a detailed account of the massacre, notably starting with this paragraph: “Public interest in the City of Rocks near Oakley was revived recently by the second official exploration. Efforts to have the area designated as a national monument are progressing.” The detailed account gave practically a blow-by-blow description of the massacre, leaving out only the names of a single person who died there or the names of any of the five survivors.

So where did all the detail about the massacre come from? I found the account in a book called Six Decades Back, by Charles Shirley Walgamott, published first by Caxton in 1936 and republished by University of Idaho Press in 1990. Many of the newspaper accounts are lifted word for word from the book. Walgamott relied on the memory of W.M. E. Johnston who was a 12-year-old living in Ogden, Utah at the time of the alleged massacre. He remembered stories about the event from that time. About a dozen years later he and his family moved to the Almo area and began farming at the massacre site. He claimed they often plowed up old coins, pistols, and other evidence that it had taken place.

Merle Wells and other historians at the Idaho State Historical Society agreed with Madsen that the event never happened, and in the mid-1990s they proposed to take the stone down in the interest of accuracy. The residents of Almo were not at all thrilled with that idea. They had grown up hearing the story of the Almo Massacre. It was part of their cultural fabric. So, the stone stayed in place.

So did the City of Rocks. It should be on your bucket list to see the City of Rocks National Reserve, now jointly managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service. While you’re there, check out Castle Rocks State Park. Oh, and that monument, if you’re curious.

The Almo Massacre monument.

The Almo Massacre monument.

Published on August 09, 2020 04:00

August 8, 2020

White Bird

Do you remember the switchback road that snaked up the mountain at White Bird? If you wanted to go by car from the northern part of the state to the southern, or vice versa, you had no choice but to tackle that hill.

Coming from the south, the road brought you out of the Salmon River canyon and up onto the prairie, lifting you about 2,700 feet on a corkscrew path. It was a thrill to look down into the draws along the road to see the carcasses of cars that had failed to negotiate a turn. Legend has it that a woman from Massachusetts refused to ride down the hill with her husband. He drove the car slowly while she walked behind.

But all that changed in 1975 when the 811-foot span was dedicated. Governor Cecil D. Andrus is shown in this Idaho Transportation Department photo at the dedication. He famously referred to the old Highway 95 as a “goat path.”

The project, building the road and building the bridge, took ten years. It was a challenge just getting the 26 steel bridge sections to the site from Indiana where they were made. They weighed between 116,000 and 148,000 pounds. Each section arrived by truck. The first one slipped off the flatbed near Riggins causing minor injury to the rear steering unit driver. It took 45 days to get the steel sections on site so they could be assembled.

Today traveling the stretch between White Bird and the prairie above is easy enough, though it still provides some heart-stopping views into the valley. You can even spot the Seven Devils in the distance from the top of the hill if you know where to look. The old road is still in place. I’ve taken it a few times in a sports car just for grins.

Governor Cecil D. Andurs during the dedication of the new highway at White Bird in 1975.

Governor Cecil D. Andurs during the dedication of the new highway at White Bird in 1975.

Coming from the south, the road brought you out of the Salmon River canyon and up onto the prairie, lifting you about 2,700 feet on a corkscrew path. It was a thrill to look down into the draws along the road to see the carcasses of cars that had failed to negotiate a turn. Legend has it that a woman from Massachusetts refused to ride down the hill with her husband. He drove the car slowly while she walked behind.

But all that changed in 1975 when the 811-foot span was dedicated. Governor Cecil D. Andrus is shown in this Idaho Transportation Department photo at the dedication. He famously referred to the old Highway 95 as a “goat path.”

The project, building the road and building the bridge, took ten years. It was a challenge just getting the 26 steel bridge sections to the site from Indiana where they were made. They weighed between 116,000 and 148,000 pounds. Each section arrived by truck. The first one slipped off the flatbed near Riggins causing minor injury to the rear steering unit driver. It took 45 days to get the steel sections on site so they could be assembled.

Today traveling the stretch between White Bird and the prairie above is easy enough, though it still provides some heart-stopping views into the valley. You can even spot the Seven Devils in the distance from the top of the hill if you know where to look. The old road is still in place. I’ve taken it a few times in a sports car just for grins.

Governor Cecil D. Andurs during the dedication of the new highway at White Bird in 1975.

Governor Cecil D. Andurs during the dedication of the new highway at White Bird in 1975.

Published on August 08, 2020 04:00

August 7, 2020

Blister Rust

I recently posted a photo of a CCC blister rust crew. That prompted Donald Barclay to send me some crew photos from the mid-thirties, which prompted me to do another little piece about white pine blister rust.

Blister rust is native to China and was accidentally introduced to North America around 1900. It is devastating to white pines and, in turn, the ecosystems around them. The complex life cycle of blister rust requires two hosts, white pine, and currant or gooseberry plants. Some Indian paint brush has also been detected with blister rust.

If blister rust is discovered on a few limbs of a tree, and those limbs are pruned, the tree may be saved. If it is infecting the trunk of the tree, it will be lost. Pruning, while somewhat effective, is costly and time-consuming.

The method of controlling blister rust for many years was to destroy the alternate host, breaking the cycle of the fungus. That meant rooting up currant and gooseberry plants. The program to destroy those plants on Forest Service land lasted from 1916 to 1967. Ultimately, it wasn’t really working. During that time, though, arborists were identifying blister rust resistant trees. Cultivating those trees over the years has resulted in a variety of western white pine that is about 50 percent resistant to blister rust. Replacing stands with more disease resistant trees is the main strategy to control blister rust today.

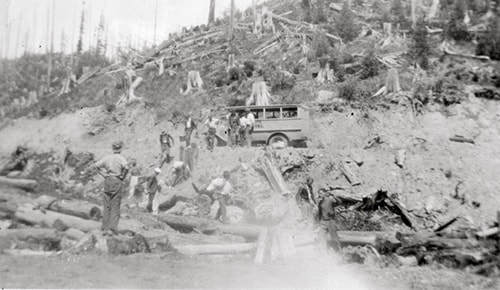

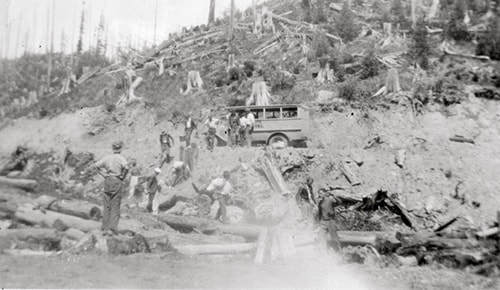

This is a blister rust crew working somewhere in Northern Idaho circa 1935. They may have been killing currant bushes left behind after a clearcut. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

This is a blister rust crew working somewhere in Northern Idaho circa 1935. They may have been killing currant bushes left behind after a clearcut. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.  Unidentified members of a blister rust crew. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

Unidentified members of a blister rust crew. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.  Another blister rust crew member armed for combat with a currant bush. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

Another blister rust crew member armed for combat with a currant bush. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

A blister rust crew camp circa 1935. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

A blister rust crew camp circa 1935. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

Blister rust is native to China and was accidentally introduced to North America around 1900. It is devastating to white pines and, in turn, the ecosystems around them. The complex life cycle of blister rust requires two hosts, white pine, and currant or gooseberry plants. Some Indian paint brush has also been detected with blister rust.

If blister rust is discovered on a few limbs of a tree, and those limbs are pruned, the tree may be saved. If it is infecting the trunk of the tree, it will be lost. Pruning, while somewhat effective, is costly and time-consuming.

The method of controlling blister rust for many years was to destroy the alternate host, breaking the cycle of the fungus. That meant rooting up currant and gooseberry plants. The program to destroy those plants on Forest Service land lasted from 1916 to 1967. Ultimately, it wasn’t really working. During that time, though, arborists were identifying blister rust resistant trees. Cultivating those trees over the years has resulted in a variety of western white pine that is about 50 percent resistant to blister rust. Replacing stands with more disease resistant trees is the main strategy to control blister rust today.

This is a blister rust crew working somewhere in Northern Idaho circa 1935. They may have been killing currant bushes left behind after a clearcut. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

This is a blister rust crew working somewhere in Northern Idaho circa 1935. They may have been killing currant bushes left behind after a clearcut. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.  Unidentified members of a blister rust crew. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

Unidentified members of a blister rust crew. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.  Another blister rust crew member armed for combat with a currant bush. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

Another blister rust crew member armed for combat with a currant bush. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

A blister rust crew camp circa 1935. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

A blister rust crew camp circa 1935. Photo courtesy of Donald Barclay.

Published on August 07, 2020 04:00

August 6, 2020

"A Winner Never Quits and a Quitter Never Wins"

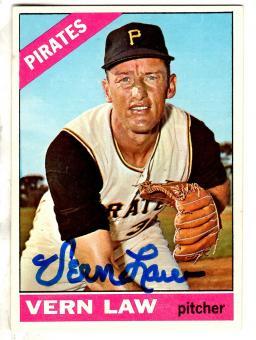

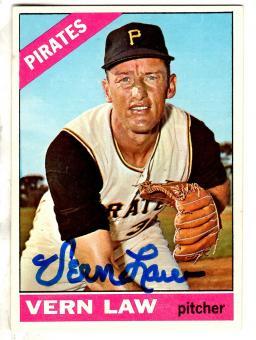

When you think of baseball players from Idaho, you might think of Harmon Kilibrew or Walter Johnson. Great players. But, don’t forget about Vern Law.

Born in Meridian, in 1930, Law first pitched in the majors for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1950. He played just one season, then left to serve in the military from 1951-1954. He returned to the Pirates and had his best year in 1960, when he won the Cy Young award and helped his team win the World Series against the New York Yankees. He was the winning pitcher in two series games.

An injury in 1963 forced him on to the voluntary retired list. In 1965, he was back on the mound, and received the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award as comeback player of the year. He left the game in 1967.

Law had a career win-loss record of 162-147. He had a 3.77 earned run average, and played in the All-Star game twice.

Law, who is LDS, got some ribbing for his devout beliefs. He was nicknamed “The Deacon” He was known for some great quotes, including “A winner never quits and a quitter never wins.”

Born in Meridian, in 1930, Law first pitched in the majors for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1950. He played just one season, then left to serve in the military from 1951-1954. He returned to the Pirates and had his best year in 1960, when he won the Cy Young award and helped his team win the World Series against the New York Yankees. He was the winning pitcher in two series games.

An injury in 1963 forced him on to the voluntary retired list. In 1965, he was back on the mound, and received the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award as comeback player of the year. He left the game in 1967.

Law had a career win-loss record of 162-147. He had a 3.77 earned run average, and played in the All-Star game twice.

Law, who is LDS, got some ribbing for his devout beliefs. He was nicknamed “The Deacon” He was known for some great quotes, including “A winner never quits and a quitter never wins.”

Published on August 06, 2020 04:00

August 5, 2020

Take a Vacation!

Time for another edition of Idaho Then and Now, our occasional series that spotlights how things have changed… or not.

I did a search of the Idaho Statesman archives for the word “vacation.” The first 19 instances of the word’s use were for St. Michael’s Parish School in Boise, announcing its term schedule. Most early mentions of the word were about schools or government institutions taking a vacation. It wasn’t until 54 results into the search that I found a reference to a citizen taking a vacation. That was in 1881 when Mr. W.W. Calkins intended “shortly to take a few weeks vacation, during which to visit the picturesque lakes in Alturas county, for the benefit of his health.” The paper then editorialized a bit with, “He is very much in need of recreation, and we hope to see him return with rosy cheeks and beaming eyes.”

Good for W.W. Calkins! That’s what a vacation is for, right? Oh, wait. You’re from Idaho, so you may not know what a vacation is for.

According to a 2017 travel industry survey, Idaho ranks at the top of the heap when it comes to vacations. Unfortunately, it’s the wrong heap. It turns out that 78 percent of Idaho residents left vacation time unused in 2016. The worst record in the nation. Why? The same survey indicated that “showing complete dedication to their job” was one reason. Twenty-seven percent of Idaho respondents didn’t think their company culture promoted time off. And, 28 percent worried that they would appear replaceable.

Come on, Idahoans! Take a vacation! You live in a vacation wonderland.

I did a search of the Idaho Statesman archives for the word “vacation.” The first 19 instances of the word’s use were for St. Michael’s Parish School in Boise, announcing its term schedule. Most early mentions of the word were about schools or government institutions taking a vacation. It wasn’t until 54 results into the search that I found a reference to a citizen taking a vacation. That was in 1881 when Mr. W.W. Calkins intended “shortly to take a few weeks vacation, during which to visit the picturesque lakes in Alturas county, for the benefit of his health.” The paper then editorialized a bit with, “He is very much in need of recreation, and we hope to see him return with rosy cheeks and beaming eyes.”

Good for W.W. Calkins! That’s what a vacation is for, right? Oh, wait. You’re from Idaho, so you may not know what a vacation is for.

According to a 2017 travel industry survey, Idaho ranks at the top of the heap when it comes to vacations. Unfortunately, it’s the wrong heap. It turns out that 78 percent of Idaho residents left vacation time unused in 2016. The worst record in the nation. Why? The same survey indicated that “showing complete dedication to their job” was one reason. Twenty-seven percent of Idaho respondents didn’t think their company culture promoted time off. And, 28 percent worried that they would appear replaceable.

Come on, Idahoans! Take a vacation! You live in a vacation wonderland.

Published on August 05, 2020 04:00

August 4, 2020

The First Territorial Capital

As most Idahoan’s know, Lewiston was the first territorial capital. Even as territorial governor William H. Wallace arrived in Lewiston in July of 1863, the fate of the first capital was sealed, though no one knew it. I use that old saw about Lewiston’s fate being “sealed,” knowing full well that not a few of you will groan. Those not groaning, just wait a few more words.

Idaho Territory at its inception included what is now Montana. The size of the territory was going to make governing it from anywhere difficult. Fortunately, an influx of gold-seekers into mining camps across the Bitterroots led quickly to the formation of Montana Territory in May 1864.

Miners were also pouring into camps in the Boise Basin. A census of the territory in September 1863 showed a total population of 32,342, including 12,000 who would soon be in Montana. That left 20,342 in what would end up in the territory/state we know today. Boise County, which included the boomtowns of Idaho City and Atlanta, boasted 16,000 residents. With four times the residents in the south as in the north—the census missed Franklin and Paris for some reason—a seat of government in southern Idaho made sense.

It’s important to note that the Idaho Territorial Legislature had yet to designate any town as the seat of government at that point. In November, 1864, the second legislature assembled in Lewiston. Legislators from the northern part of the territory tried to dodge the issue of naming a capital by proposing to ask Congress to create a new Idaho Territory to include the panhandle and eastern Washington. Southern Idaho could do whatever it wanted. This would have left the southern part of the territory shaped something like Iowa (how would Easterners ever tell them apart??).

The southern legislators had enough clout to stop that idea, and they had enough votes to establish Boise as the permanent capital of Idaho Territory.

At the end of the second territorial legislature, Lewiston Lawyers fought the decision. They claimed the legislature had convened on the wrong day and thus many legislators weren’t really legislators.

Then Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon, perhaps not having the stomach for this fight, simply left the territory. Quoting the Idaho State Historical Society Reference series on the subject, “Boise partisans tried to swipe the territorial seal and archives in order to remove them to Boise, Lewiston established an armed guard over the papers themselves. Both sides used loud language about each other, and there were petitions to Congress and hearings before a probate judge. His was not the proper court to hear the matter, but the proper court was incapacitated for reasons which embarrassed Lewiston. The territorial supreme court was not yet organized. The judges had not yet gotten together, and anyway the court was supposed to assemble in the capital and nobody knew where the capital was.” The photo is often labeled as the first territorial capitol. According to Steve Branting, who knows his Lewiston history, “the photograph, taken in 1905 by Henry Fair, helped perpetuate an error that still populates the ISHS Archives. Primary reports now show that the building, a livery store in 1863, was rented for use by Governors Wallace and Lyon as their office. The legislature met elsewhere, and where the legislature meets is the capitol. Civic groups had wanted to move the structure to save it in 1914. When they learned that it was merely Caleb Lyon's office, the well-funded preservation campaign collapsed. So did the building under heavy snow in February 1916. The only vestige of the office is a violin that was crafted from the scrap lumber. I discovered that fact from complete serendipity.”

The photo is often labeled as the first territorial capitol. According to Steve Branting, who knows his Lewiston history, “the photograph, taken in 1905 by Henry Fair, helped perpetuate an error that still populates the ISHS Archives. Primary reports now show that the building, a livery store in 1863, was rented for use by Governors Wallace and Lyon as their office. The legislature met elsewhere, and where the legislature meets is the capitol. Civic groups had wanted to move the structure to save it in 1914. When they learned that it was merely Caleb Lyon's office, the well-funded preservation campaign collapsed. So did the building under heavy snow in February 1916. The only vestige of the office is a violin that was crafted from the scrap lumber. I discovered that fact from complete serendipity.”

Idaho Territory at its inception included what is now Montana. The size of the territory was going to make governing it from anywhere difficult. Fortunately, an influx of gold-seekers into mining camps across the Bitterroots led quickly to the formation of Montana Territory in May 1864.

Miners were also pouring into camps in the Boise Basin. A census of the territory in September 1863 showed a total population of 32,342, including 12,000 who would soon be in Montana. That left 20,342 in what would end up in the territory/state we know today. Boise County, which included the boomtowns of Idaho City and Atlanta, boasted 16,000 residents. With four times the residents in the south as in the north—the census missed Franklin and Paris for some reason—a seat of government in southern Idaho made sense.

It’s important to note that the Idaho Territorial Legislature had yet to designate any town as the seat of government at that point. In November, 1864, the second legislature assembled in Lewiston. Legislators from the northern part of the territory tried to dodge the issue of naming a capital by proposing to ask Congress to create a new Idaho Territory to include the panhandle and eastern Washington. Southern Idaho could do whatever it wanted. This would have left the southern part of the territory shaped something like Iowa (how would Easterners ever tell them apart??).

The southern legislators had enough clout to stop that idea, and they had enough votes to establish Boise as the permanent capital of Idaho Territory.

At the end of the second territorial legislature, Lewiston Lawyers fought the decision. They claimed the legislature had convened on the wrong day and thus many legislators weren’t really legislators.

Then Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon, perhaps not having the stomach for this fight, simply left the territory. Quoting the Idaho State Historical Society Reference series on the subject, “Boise partisans tried to swipe the territorial seal and archives in order to remove them to Boise, Lewiston established an armed guard over the papers themselves. Both sides used loud language about each other, and there were petitions to Congress and hearings before a probate judge. His was not the proper court to hear the matter, but the proper court was incapacitated for reasons which embarrassed Lewiston. The territorial supreme court was not yet organized. The judges had not yet gotten together, and anyway the court was supposed to assemble in the capital and nobody knew where the capital was.”

The photo is often labeled as the first territorial capitol. According to Steve Branting, who knows his Lewiston history, “the photograph, taken in 1905 by Henry Fair, helped perpetuate an error that still populates the ISHS Archives. Primary reports now show that the building, a livery store in 1863, was rented for use by Governors Wallace and Lyon as their office. The legislature met elsewhere, and where the legislature meets is the capitol. Civic groups had wanted to move the structure to save it in 1914. When they learned that it was merely Caleb Lyon's office, the well-funded preservation campaign collapsed. So did the building under heavy snow in February 1916. The only vestige of the office is a violin that was crafted from the scrap lumber. I discovered that fact from complete serendipity.”

The photo is often labeled as the first territorial capitol. According to Steve Branting, who knows his Lewiston history, “the photograph, taken in 1905 by Henry Fair, helped perpetuate an error that still populates the ISHS Archives. Primary reports now show that the building, a livery store in 1863, was rented for use by Governors Wallace and Lyon as their office. The legislature met elsewhere, and where the legislature meets is the capitol. Civic groups had wanted to move the structure to save it in 1914. When they learned that it was merely Caleb Lyon's office, the well-funded preservation campaign collapsed. So did the building under heavy snow in February 1916. The only vestige of the office is a violin that was crafted from the scrap lumber. I discovered that fact from complete serendipity.”

Published on August 04, 2020 04:00

August 3, 2020

Slicing Through the Fairgrounds

An advisory committee formed in 2020 to consider moving the Western Idaho Fairgrounds from its location in Garden City. This isn’t a new idea. A similar group popped up in 1963 when it became clear that the Western Idaho Fairgrounds would need to find a new home. Spoiler alert: The one they found was in Garden City at its present location.

The fair had operated at its Fairview Avenue location since 1916. In case you ever wondered where Fairview Avenue got its name, you need wonder no more. The fairgrounds lay between Fairview Avenue on the north and Irving Street on the south. Orchard Street was the eastern boundary and Curtis Road bordered the fairgrounds on the west.

If this all seems impossible because of that multi-lane interstate highway spur running through the middle of it, you’ve hit on the reason for the move. The Idaho Transportation Department carved out a lot of dirt diagonally through the fairgrounds property, dropping the elevation of the highway well below grade (see graphic below).

Although moving the fairgrounds was an obvious need in 1963, the fair didn’t open at its current Garden City site until 1967. The move was delayed a bit because the savvy City of Boise annexed the old fairgrounds property in 1966, certain that values would go up and services would be needed. Overlaying city zoning on the property ruffled the feathers of some potential developers, but the annexation went through.

The fair became The Western Idaho Fair along with the move in 1967. Previously it had billed itself as The Western Idaho State Fair, though it had no affiliation with the state. The new site was 235 acres, compared with the 45-acre site along Fairview. That gave the county room to expand with parking for 6,000 cars. The Exposition Building made its debut in 1967, allowing for two acres of indoor exhibits.

The new fairgrounds generated many millions in economic activity and continues to do so today. It will likely be an economic engine for years into to the future, wherever it is.

A shot of the Western Idaho Fair from 1934. Note the bare ground at the top of the picture, probably looking west. The perimeter signs advertise Adam and Eve, Marvo the Wonder Boy Doomed to Die, palmistry, and the Girl Who Can Not Die. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A shot of the Western Idaho Fair from 1934. Note the bare ground at the top of the picture, probably looking west. The perimeter signs advertise Adam and Eve, Marvo the Wonder Boy Doomed to Die, palmistry, and the Girl Who Can Not Die. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.  The site of the old Ada County fairgrounds is shaded in light blue on the Google map above.

The site of the old Ada County fairgrounds is shaded in light blue on the Google map above.

The fair had operated at its Fairview Avenue location since 1916. In case you ever wondered where Fairview Avenue got its name, you need wonder no more. The fairgrounds lay between Fairview Avenue on the north and Irving Street on the south. Orchard Street was the eastern boundary and Curtis Road bordered the fairgrounds on the west.

If this all seems impossible because of that multi-lane interstate highway spur running through the middle of it, you’ve hit on the reason for the move. The Idaho Transportation Department carved out a lot of dirt diagonally through the fairgrounds property, dropping the elevation of the highway well below grade (see graphic below).

Although moving the fairgrounds was an obvious need in 1963, the fair didn’t open at its current Garden City site until 1967. The move was delayed a bit because the savvy City of Boise annexed the old fairgrounds property in 1966, certain that values would go up and services would be needed. Overlaying city zoning on the property ruffled the feathers of some potential developers, but the annexation went through.

The fair became The Western Idaho Fair along with the move in 1967. Previously it had billed itself as The Western Idaho State Fair, though it had no affiliation with the state. The new site was 235 acres, compared with the 45-acre site along Fairview. That gave the county room to expand with parking for 6,000 cars. The Exposition Building made its debut in 1967, allowing for two acres of indoor exhibits.

The new fairgrounds generated many millions in economic activity and continues to do so today. It will likely be an economic engine for years into to the future, wherever it is.

A shot of the Western Idaho Fair from 1934. Note the bare ground at the top of the picture, probably looking west. The perimeter signs advertise Adam and Eve, Marvo the Wonder Boy Doomed to Die, palmistry, and the Girl Who Can Not Die. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A shot of the Western Idaho Fair from 1934. Note the bare ground at the top of the picture, probably looking west. The perimeter signs advertise Adam and Eve, Marvo the Wonder Boy Doomed to Die, palmistry, and the Girl Who Can Not Die. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.  The site of the old Ada County fairgrounds is shaded in light blue on the Google map above.

The site of the old Ada County fairgrounds is shaded in light blue on the Google map above.

Published on August 03, 2020 04:00

August 2, 2020

Shoup and the Sand Creek Massacre

History is full of imperfect men. How could it be otherwise?

Idaho’s last territorial governor and the first governor of the State of Idaho was George L. Shoup. He didn’t serve long as Idaho’s governor. The Idaho Legislature elected him to the US Senate just a few weeks after he had been appointed governor. He served in the senate for ten years.

There is much one can say about Shoup that is positive. He was a strong force in shaping Idaho in its early days. Strong enough that he is honored in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the US Capitol. Each state gets only two statues. Idaho chose Shoup and Senator William E. Borah for that honor (photo).

Among his many business and political accomplishments is one that is a mere footnote in his biography, but it is one that has always troubled me. Col. George L. Shoup was a key leader of what is most often referred to today as the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado. Here’s how Wikipedia describes it:

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the Battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre in the American Indian Wars that occurred on November 29, 1864, when a 675-man force of Colorado U.S. Volunteer Cavalry attacked and destroyed a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho in southeastern Colorado Territory, killing and mutilating an estimated 70–163 Native Americans, about two-thirds of whom were women and children. The location has been designated the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site and is administered by the National Park Service.

It is too complex an issue for a short post to examine all sides of the story and better understand the motives of those involved. To his credit, many times in his later life Shoup showed a willingness to work with Native Americans and he supported fair treatment for them. It is also worth noting that two troop commanders, Captain Silas Soule and Lt. Joseph Cramer, refused to have their soldiers engage. They are seen as heroes today by many.

Idaho’s last territorial governor and the first governor of the State of Idaho was George L. Shoup. He didn’t serve long as Idaho’s governor. The Idaho Legislature elected him to the US Senate just a few weeks after he had been appointed governor. He served in the senate for ten years.

There is much one can say about Shoup that is positive. He was a strong force in shaping Idaho in its early days. Strong enough that he is honored in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the US Capitol. Each state gets only two statues. Idaho chose Shoup and Senator William E. Borah for that honor (photo).

Among his many business and political accomplishments is one that is a mere footnote in his biography, but it is one that has always troubled me. Col. George L. Shoup was a key leader of what is most often referred to today as the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado. Here’s how Wikipedia describes it:

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the Battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre in the American Indian Wars that occurred on November 29, 1864, when a 675-man force of Colorado U.S. Volunteer Cavalry attacked and destroyed a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho in southeastern Colorado Territory, killing and mutilating an estimated 70–163 Native Americans, about two-thirds of whom were women and children. The location has been designated the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site and is administered by the National Park Service.

It is too complex an issue for a short post to examine all sides of the story and better understand the motives of those involved. To his credit, many times in his later life Shoup showed a willingness to work with Native Americans and he supported fair treatment for them. It is also worth noting that two troop commanders, Captain Silas Soule and Lt. Joseph Cramer, refused to have their soldiers engage. They are seen as heroes today by many.

Published on August 02, 2020 04:00

August 1, 2020

What to Name the Monster

No self-respecting lake monster should go without a name. At least, that’s what A. Boon McCallum, editor and publisher of the Payette Lakes Star thought.

Sightings of some sort of creature that seemed out of place in Payette Lake had been going on for years when the newspaper in McCall decided to run a contest, in 1954, to give the poor beast a name. More than 200 people entered the contest. The suggestions ranged from the pseudo-scientific to variations on monster names. They included:

Boon

Fantasy

Nobby Dick

Humpy

Watzit

McFlash

High Ho

Peekaboo

Snorky

Neptune Ned

…and on and on. The winner, as you may know, was Sharlie. Le Isle Hennefer Tury of Springfield, Virginia walked away with the $40 prize for that one. Lest Idahoans grump too much about an out-of-stater winning the contest, it was pointed out that she had at one time lived in Twin Falls.

I confess to having my own “Sharlie” sighting once while standing atop Porcupine Point in Ponderosa State Park. With no boats in site for miles the water below in The Narrows started churning. It continued to churn for about two minutes. There was no creepy music accompanying the phenomenon, so I just chalked it up to space aliens.

Sightings of some sort of creature that seemed out of place in Payette Lake had been going on for years when the newspaper in McCall decided to run a contest, in 1954, to give the poor beast a name. More than 200 people entered the contest. The suggestions ranged from the pseudo-scientific to variations on monster names. They included:

Boon

Fantasy

Nobby Dick

Humpy

Watzit

McFlash

High Ho

Peekaboo

Snorky

Neptune Ned

…and on and on. The winner, as you may know, was Sharlie. Le Isle Hennefer Tury of Springfield, Virginia walked away with the $40 prize for that one. Lest Idahoans grump too much about an out-of-stater winning the contest, it was pointed out that she had at one time lived in Twin Falls.

I confess to having my own “Sharlie” sighting once while standing atop Porcupine Point in Ponderosa State Park. With no boats in site for miles the water below in The Narrows started churning. It continued to churn for about two minutes. There was no creepy music accompanying the phenomenon, so I just chalked it up to space aliens.

Published on August 01, 2020 04:00

July 31, 2020

Pop Quiz!

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). When Blackfoot celebrated a Diamond Jubilee in 1909, what was the celebration for?

A. The building of old Fort Boise.

B. The building of old Fort Hall.

C. The first Protestant sermon delivered west of the Rocky Mountains.

D. A famous horse race.

E. The construction of the Taylor Bridge.

2). What brought the Magic Valley out of the Great Depression?

A. The construction of the North Side Canal.

B. Opening Shoshone Falls as a tourist destination.

C. The construction of Minidoka Dam.

D. The construction of the Hunt Camp.

E. The construction of Albion Normal School.

3). Who was known as The Ramblin’ Kid?

A. U. S. Senator Glenn Taylor.

B. Idaho Senator Earl Wayland Bowman.

C. U.S. Senator William Borah.

D. Idaho Senator James Just

E. U.S. Senator Weldon B. Heyburn

4). What stopped in Boise for a visit in July 1915?

A. The U.S. Constitution.

B. The Betsy Ross Flag.

C. A marble statue of George Washington.

D. A model of the Statue of Liberty.

E. The Liberty Bell.

5) What was the football field at Idaho State University originally called?

A. Gate City Field

B. Bud Davis Field

C. Union Pacific Field

D. Chief Pocatello Field

E. The Spud Bowl

Answers

Answers

1, C

2, D

3, B

4, E

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). When Blackfoot celebrated a Diamond Jubilee in 1909, what was the celebration for?

A. The building of old Fort Boise.

B. The building of old Fort Hall.

C. The first Protestant sermon delivered west of the Rocky Mountains.

D. A famous horse race.

E. The construction of the Taylor Bridge.

2). What brought the Magic Valley out of the Great Depression?

A. The construction of the North Side Canal.

B. Opening Shoshone Falls as a tourist destination.

C. The construction of Minidoka Dam.

D. The construction of the Hunt Camp.

E. The construction of Albion Normal School.

3). Who was known as The Ramblin’ Kid?

A. U. S. Senator Glenn Taylor.

B. Idaho Senator Earl Wayland Bowman.

C. U.S. Senator William Borah.

D. Idaho Senator James Just

E. U.S. Senator Weldon B. Heyburn

4). What stopped in Boise for a visit in July 1915?

A. The U.S. Constitution.

B. The Betsy Ross Flag.

C. A marble statue of George Washington.

D. A model of the Statue of Liberty.

E. The Liberty Bell.

5) What was the football field at Idaho State University originally called?

A. Gate City Field

B. Bud Davis Field

C. Union Pacific Field

D. Chief Pocatello Field

E. The Spud Bowl

Answers

Answers1, C

2, D

3, B

4, E

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on July 31, 2020 04:00