Rick Just's Blog, page 155

July 30, 2020

The Aspirational Architecture of School Buildings

Forgive me, please, as I drift into a mild editorial today about public architecture.

School buildings were once a source of great community pride. This was displayed in their aspirational architecture, such as that of Boise High School (photo). The school people know today was built in phases, beginning in 1908. It was the work of Idaho architects John E. Tourtellotte and Charles F. Hummel, who would also design the Idaho statehouse. Boise High is designed in the neo-classical revival style. One of the details that one might consider aspirational is the representation of Plato in the frieze on the portico roof at the entrance, held aloft by soaring columns.

Compare this to almost any high school built in the past 30 years. You’ll more often find a design that would work as well for a prison, with concrete and cinder block walls and small windows if windows are included at all. There is an industrial feel to these schools.

The aspirations of the community were sometimes reflected in school names. In Boise three early schools were named for poets, Whittier, Lowell, and Longfellow. Today names like that are more often found in the themed streets of subdivisions.

Building a school with memorable architecture would probably be impossible today, given the resistance to the additional cost. I understand why communities, arguably, choose to invest more in education itself, rather than the buildings that house the students. I wonder, though, if we are missing something important in the educational environment, a sense of wonder and of continuity with the past.

Since we are unlikely to build something today with character, I encourage communities that still can to save their iconic old school buildings whenever possible.

School buildings were once a source of great community pride. This was displayed in their aspirational architecture, such as that of Boise High School (photo). The school people know today was built in phases, beginning in 1908. It was the work of Idaho architects John E. Tourtellotte and Charles F. Hummel, who would also design the Idaho statehouse. Boise High is designed in the neo-classical revival style. One of the details that one might consider aspirational is the representation of Plato in the frieze on the portico roof at the entrance, held aloft by soaring columns.

Compare this to almost any high school built in the past 30 years. You’ll more often find a design that would work as well for a prison, with concrete and cinder block walls and small windows if windows are included at all. There is an industrial feel to these schools.

The aspirations of the community were sometimes reflected in school names. In Boise three early schools were named for poets, Whittier, Lowell, and Longfellow. Today names like that are more often found in the themed streets of subdivisions.

Building a school with memorable architecture would probably be impossible today, given the resistance to the additional cost. I understand why communities, arguably, choose to invest more in education itself, rather than the buildings that house the students. I wonder, though, if we are missing something important in the educational environment, a sense of wonder and of continuity with the past.

Since we are unlikely to build something today with character, I encourage communities that still can to save their iconic old school buildings whenever possible.

Published on July 30, 2020 04:00

July 29, 2020

The Spud Bowl

The Idaho Potato Bowl has been around for a while. It wasn’t the first “bowl” named after the state’s famous tuber. That honor probably goes to Idaho State College’s “Spud Bowl.” It wasn’t a bowl game, though a sports columnist for the Idaho State Journal opined that there should be a bowl game with that name back in 1949.

The “Spud Bowl” was the college football field built by the Civil Works Administration (CWA) in 1936. CWA was one of the New Deal projects that came out of the Roosevelt administration. The photo below shows men scraping out the shape of the Spud Bowl.

The football field was renamed for William E. “Bud” Davis, who was Idaho State University President from 1965-1975.

The color photo at the bottom of this post is of Davis Field as it looks today. It has a seating capacity of 4,000 fans.

The “Spud Bowl” was the college football field built by the Civil Works Administration (CWA) in 1936. CWA was one of the New Deal projects that came out of the Roosevelt administration. The photo below shows men scraping out the shape of the Spud Bowl.

The football field was renamed for William E. “Bud” Davis, who was Idaho State University President from 1965-1975.

The color photo at the bottom of this post is of Davis Field as it looks today. It has a seating capacity of 4,000 fans.

Published on July 29, 2020 04:00

July 28, 2020

The Future, Courtesy of the New York Canal

Prognostication in print eventually tends to make the prognosticator look foolish. Witness the regular predictions about the fantastic future filled with flying cars, jet packs, and moving sidewalks common in the early Twentieth Century.

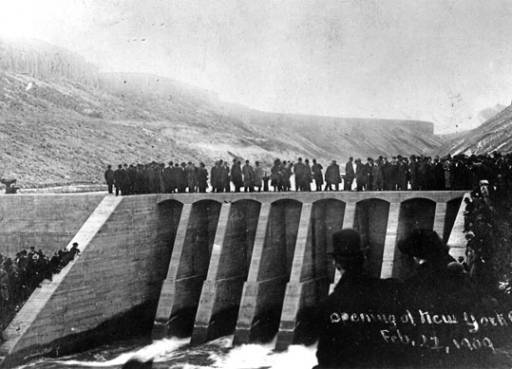

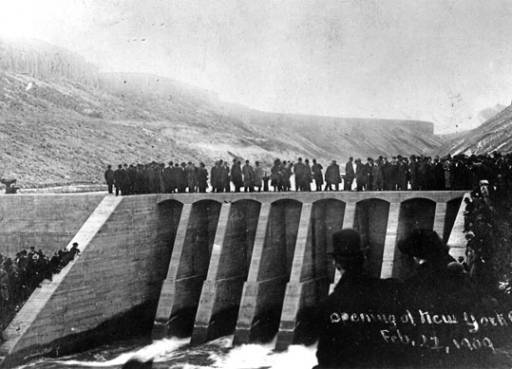

In 1909 one prognosticator at the Idaho Statesman got it right helped, perhaps, by his neglecting to establish a timeline for his predictions. The day following the dedication of Treasure Valley’s New York Canal on February, 22 1909, an article appeared titled “Power Behind the Dam.”

“Upon even the most thoughtless the real importance of the work, completion of which was yesterday celebrated will be forced to mind when thousands of acres of additional land is brought under cultivation, when Boise bounds to 150,000 population; when farms supplant great stretches of barren land and the swaddling clothes of towns in this part of the state are tossed into the rubbish heap in exchange for municipal togs.”

Boise’s population in 1909 was about 17,000, so a city of 150,000 probably seemed ludicrous. It would hit that mark in the early 1990s and today is closer to 250,000.

The progression from desert to farm to town to city was also correct. Eagle with a Hilton? Who’d have thought that in 1909 or even 1979?

Diversion Dam also supplied electricity for the valley for many years, as well as irrigation water for farmland that in more recent decades has grown into sprawling housing developments.

The photo of the dedication of New York Canal diversion is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive.

In 1909 one prognosticator at the Idaho Statesman got it right helped, perhaps, by his neglecting to establish a timeline for his predictions. The day following the dedication of Treasure Valley’s New York Canal on February, 22 1909, an article appeared titled “Power Behind the Dam.”

“Upon even the most thoughtless the real importance of the work, completion of which was yesterday celebrated will be forced to mind when thousands of acres of additional land is brought under cultivation, when Boise bounds to 150,000 population; when farms supplant great stretches of barren land and the swaddling clothes of towns in this part of the state are tossed into the rubbish heap in exchange for municipal togs.”

Boise’s population in 1909 was about 17,000, so a city of 150,000 probably seemed ludicrous. It would hit that mark in the early 1990s and today is closer to 250,000.

The progression from desert to farm to town to city was also correct. Eagle with a Hilton? Who’d have thought that in 1909 or even 1979?

Diversion Dam also supplied electricity for the valley for many years, as well as irrigation water for farmland that in more recent decades has grown into sprawling housing developments.

The photo of the dedication of New York Canal diversion is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive.

Published on July 28, 2020 04:00

July 20, 2020

The Fosbury Flop

Idaho has a claim on a sport-changing Olympian. Or, maybe he has a claim on Idaho. When Dick Fosbury won the gold medal in the 1968 Olympics he hailed from Oregon. But in 1977, he moved to Ketchum where he still lives. He and a partner established Galena Engineering in 1978. He ran for a seat in the Idaho Legislature in 2014 against incumbent Steve Miller, but lost that race.

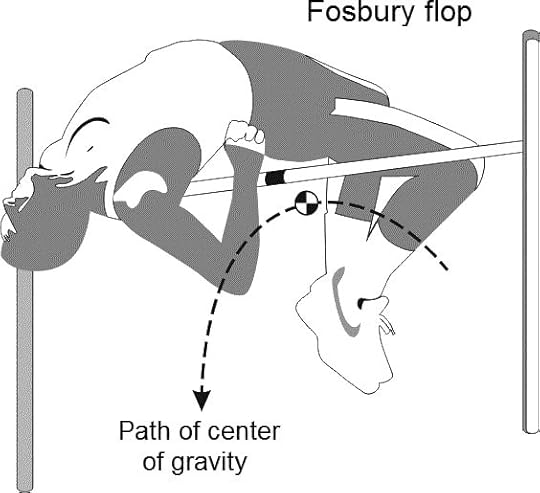

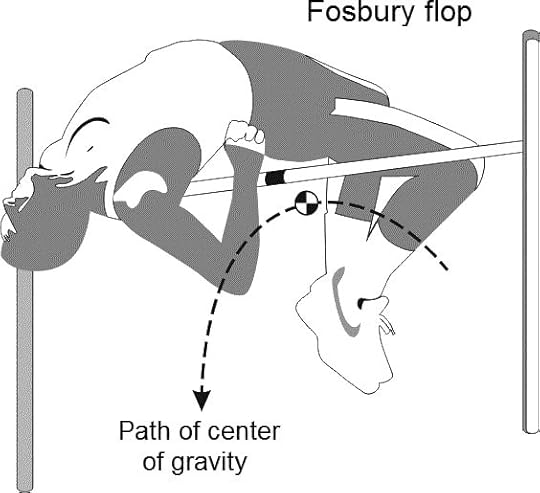

Winning an Olympic gold medal comes with its own notoriety. When you break the Olympic record and do so in a totally unconventional way, the notoriety is exponential. Fosbury’s sport was the high jump. His innovation, known today as the Fosbury Flop, was to go over the bar backwards, head-first, curving his body over and kicking his legs up in the air at the end of the jump, landing on his back. It was awkward looking. Maybe it even looked impossible, but it worked. Fosbury cleared 7 feet 4 ½ inches in Mexico City for a new Olympic record.

So, why hadn’t jumpers tried this before? Well, someone has to be first. Also, for decades preceding Fosbury’s innovation a jump like that would have been dangerous, almost guaranteeing injury. What made it possible in Fosbury’s time was the wide-spread use of thick foam pads as a landing site. Prior to that jumpers were landing in sawdust or wood chips.

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

Winning an Olympic gold medal comes with its own notoriety. When you break the Olympic record and do so in a totally unconventional way, the notoriety is exponential. Fosbury’s sport was the high jump. His innovation, known today as the Fosbury Flop, was to go over the bar backwards, head-first, curving his body over and kicking his legs up in the air at the end of the jump, landing on his back. It was awkward looking. Maybe it even looked impossible, but it worked. Fosbury cleared 7 feet 4 ½ inches in Mexico City for a new Olympic record.

So, why hadn’t jumpers tried this before? Well, someone has to be first. Also, for decades preceding Fosbury’s innovation a jump like that would have been dangerous, almost guaranteeing injury. What made it possible in Fosbury’s time was the wide-spread use of thick foam pads as a landing site. Prior to that jumpers were landing in sawdust or wood chips.

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

Published on July 20, 2020 04:00

July 19, 2020

Canning Programs

I continue to be amazed at the way this country pulled together during the Great Depression. Much of that came about through the efforts of the Works Projects Administration (WPA). The WPA programs started in 1935 and went into the war years, ending in 1943. Many of the projects were on a large scale such as the building of roads and parks. I recently ran across a program that was new to me.

The Canning Program was instituted to feed needy school children and persons in public institutions. Much of the produce came from the related Gardening Program.

Children signed up for “Rustler Clubs,” going out in groups to pick surplus fruits and vegetables.

Idaho had one of the larger canning projects. In July, 1936, production in Idaho reached 18,672 cans of vegetables, fruits, jellies, jams, and soups. During its lifetime, the program canned 85,000,000 quarts of food nationwide.

As the war came along the focus of the Boise canning program changed. It became a community canning service for families who wanted to preserve food so they could save their ration stamps. Operating out of the Ada County Fairgrounds, the Boise-Meridian cannery assisted women in putting up their own produce.

A 1945 Statesman article listed asparagus, peas, Swiss chard, carrots and peas in combination, chicken, and pork and beans as food being canned under expert supervision.

The Canning Program was instituted to feed needy school children and persons in public institutions. Much of the produce came from the related Gardening Program.

Children signed up for “Rustler Clubs,” going out in groups to pick surplus fruits and vegetables.

Idaho had one of the larger canning projects. In July, 1936, production in Idaho reached 18,672 cans of vegetables, fruits, jellies, jams, and soups. During its lifetime, the program canned 85,000,000 quarts of food nationwide.

As the war came along the focus of the Boise canning program changed. It became a community canning service for families who wanted to preserve food so they could save their ration stamps. Operating out of the Ada County Fairgrounds, the Boise-Meridian cannery assisted women in putting up their own produce.

A 1945 Statesman article listed asparagus, peas, Swiss chard, carrots and peas in combination, chicken, and pork and beans as food being canned under expert supervision.

Published on July 19, 2020 04:00

July 18, 2020

FDR at Farragut

On October 3, 1942, the Kingston Daily Freeman printed the following, datelined Farragut Idaho. “No one knew the President of the United States was visiting the naval training station.

The two workmen looked up as a car went by.

Said one:

‘That almost looks like F.D.R. himself.’

Answered the other:

‘Yep, but he’s at the White House.’

They went back to work.”

It was FDR. He was on a secret nationwide tour of defense plants and military installations. The press was ordered not to cover his trip until two weeks after it was over. His stop in North Idaho took place on September 21, 1942.

The president’s relationship with the press during that time of war has received much analysis in later days. For one thing, the press seemed to shy away from any reference or photograph that might show FDR as anything less than at the top of his game. Pictures of him using a cane were rare. Even rarer were pictures of him in a wheelchair.

John Wood, well known for his history of railroads in the Coeur d’Alene mining area, shared with me a press photo of FDR on his visit to Farragut. He was going to PhotoShop out a few scratches, but when he looked closely at the picture he noticed someone had beaten him to it on the original. That is, the photo was altered in some interesting ways. First, someone seems to have dodged out a cigarette from FDR’s mouth. John also noticed that something was going on with the car’s visor on the right. It looks like there was a map clipped to it, most of which has been retouched to oblivion. When I looked at the photo I noticed one more little history-altering touch. Someone obliterated a hearing aid from FDR’s ear. In a way, it’s the most obvious alteration because it leaves a hearing-aid-shaped void.

For history buffs, this is interesting because it further illuminates to what extent the president’s public image was manipulated. To me the human frailties everyone was hiding only further emphasize the strengths FDR had.

The original press release photo, above, shows Idaho Governor Chase Clark in the back seat. The blow-up below shows the retouching that took place to improve FDR's image a bit.

The original press release photo, above, shows Idaho Governor Chase Clark in the back seat. The blow-up below shows the retouching that took place to improve FDR's image a bit.

The two workmen looked up as a car went by.

Said one:

‘That almost looks like F.D.R. himself.’

Answered the other:

‘Yep, but he’s at the White House.’

They went back to work.”

It was FDR. He was on a secret nationwide tour of defense plants and military installations. The press was ordered not to cover his trip until two weeks after it was over. His stop in North Idaho took place on September 21, 1942.

The president’s relationship with the press during that time of war has received much analysis in later days. For one thing, the press seemed to shy away from any reference or photograph that might show FDR as anything less than at the top of his game. Pictures of him using a cane were rare. Even rarer were pictures of him in a wheelchair.

John Wood, well known for his history of railroads in the Coeur d’Alene mining area, shared with me a press photo of FDR on his visit to Farragut. He was going to PhotoShop out a few scratches, but when he looked closely at the picture he noticed someone had beaten him to it on the original. That is, the photo was altered in some interesting ways. First, someone seems to have dodged out a cigarette from FDR’s mouth. John also noticed that something was going on with the car’s visor on the right. It looks like there was a map clipped to it, most of which has been retouched to oblivion. When I looked at the photo I noticed one more little history-altering touch. Someone obliterated a hearing aid from FDR’s ear. In a way, it’s the most obvious alteration because it leaves a hearing-aid-shaped void.

For history buffs, this is interesting because it further illuminates to what extent the president’s public image was manipulated. To me the human frailties everyone was hiding only further emphasize the strengths FDR had.

The original press release photo, above, shows Idaho Governor Chase Clark in the back seat. The blow-up below shows the retouching that took place to improve FDR's image a bit.

The original press release photo, above, shows Idaho Governor Chase Clark in the back seat. The blow-up below shows the retouching that took place to improve FDR's image a bit.

Published on July 18, 2020 04:00

July 17, 2020

Saved by the Cannibals

You’ve seen the comic trope where a couple of people are tied up and sitting in a big iron pot over a fire, right? It’s the setup to a cannibal joke of some kind. To Boisean John Nelson, it wasn’t a joke.

T/Sgt Nelson, an aerial gunner, and six companions bailed out of their B-24 Liberator bomber in November 1944, parachuting into jungles of Borneo. They were found by natives who had been headhunters prior to getting a little religion from missionaries they had met. But it wasn’t the headhunters the men were worried about; it was the Japanese.

The Boise High grad was 19 when he found himself running from Japanese soldiers in Borneo. He and the other six who had parachuted from the plane joined up with five Navy fliers who had bailed out of their flaming plane. Five other Navy men had been found and killed by the Japanese.

The Americans were hustled from village to village trying to outrun the enemy. They were on the lam for eight months before they were finally rescued by Australian guerilla fighters.

Nelson had malaria four times during those months. He was finally cured of that when the natives fed him some medicine made from the bark of a tree.

The men subsisted mostly on rice with a little chicken and pork coming along occasionally. For entertainment, when they weren’t on the run, they read and re-read a few old copies of Readers Digest. In one village one of the Liberator engineers got an old phonograph working that had been left by Dutch traders. They had two records, “Star Dust,” and “Lullaby of Broadway.” Nelson, quoted in the September 7, 1945 Idaho Statesman, said, “I’ll never forget the taste of rice or the melodies of those two songs.”

The story of the men’s trial was told in the 2009 PBS documentary, The Airmen and the Headhunters. A transcript is available here, but the video itself was unavailable last time I checked.

John Nelson passed away in 2000 in Tucson, Arizona.

John Nelson

John Nelson

T/Sgt Nelson, an aerial gunner, and six companions bailed out of their B-24 Liberator bomber in November 1944, parachuting into jungles of Borneo. They were found by natives who had been headhunters prior to getting a little religion from missionaries they had met. But it wasn’t the headhunters the men were worried about; it was the Japanese.

The Boise High grad was 19 when he found himself running from Japanese soldiers in Borneo. He and the other six who had parachuted from the plane joined up with five Navy fliers who had bailed out of their flaming plane. Five other Navy men had been found and killed by the Japanese.

The Americans were hustled from village to village trying to outrun the enemy. They were on the lam for eight months before they were finally rescued by Australian guerilla fighters.

Nelson had malaria four times during those months. He was finally cured of that when the natives fed him some medicine made from the bark of a tree.

The men subsisted mostly on rice with a little chicken and pork coming along occasionally. For entertainment, when they weren’t on the run, they read and re-read a few old copies of Readers Digest. In one village one of the Liberator engineers got an old phonograph working that had been left by Dutch traders. They had two records, “Star Dust,” and “Lullaby of Broadway.” Nelson, quoted in the September 7, 1945 Idaho Statesman, said, “I’ll never forget the taste of rice or the melodies of those two songs.”

The story of the men’s trial was told in the 2009 PBS documentary, The Airmen and the Headhunters. A transcript is available here, but the video itself was unavailable last time I checked.

John Nelson passed away in 2000 in Tucson, Arizona.

John Nelson

John Nelson

Published on July 17, 2020 04:00

July 16, 2020

Dickensheet

Time for our occasional Then and Now feature.

This photo, from 1925, shows a car following a temporary plank road leading to the Dickensheet Bridge. Note the spare tire cover proclaiming Priest Lake Idaho. I’m not sure what is going on in this photo, but this may be the railroad bridge the car is crossing. In any case, the bridge is not yet set up for cars.

Lalia Boone doesn’t tell us why it was named Dickensheet in her otherwise thorough Idaho Place Names book. We can surmise it was probably in honor of someone named Dickensheet.

Today, if you cross the bridge over Priest River on Dickensheet Highway, you are probably on your way to either Coolin or Priest Lake State Park. The Dickensheet Unit of Priest Lake State Park is on your right just after you’ve crossed the bridge. The park unit has a small campground with fishing access to the river.

The old railroad bridge that once served trains most often pulling carloads of logs serves ATVs, motorbikes, and snowmobiles alongside the highway bridge.

The photo is from the Mike Fritz Collection.

This photo, from 1925, shows a car following a temporary plank road leading to the Dickensheet Bridge. Note the spare tire cover proclaiming Priest Lake Idaho. I’m not sure what is going on in this photo, but this may be the railroad bridge the car is crossing. In any case, the bridge is not yet set up for cars.

Lalia Boone doesn’t tell us why it was named Dickensheet in her otherwise thorough Idaho Place Names book. We can surmise it was probably in honor of someone named Dickensheet.

Today, if you cross the bridge over Priest River on Dickensheet Highway, you are probably on your way to either Coolin or Priest Lake State Park. The Dickensheet Unit of Priest Lake State Park is on your right just after you’ve crossed the bridge. The park unit has a small campground with fishing access to the river.

The old railroad bridge that once served trains most often pulling carloads of logs serves ATVs, motorbikes, and snowmobiles alongside the highway bridge.

The photo is from the Mike Fritz Collection.

Published on July 16, 2020 04:00

July 15, 2020

The Scissors Grinder

Knives and scissors of high-quality steel tend to keep their edge for a long time. If they get dull, we sometimes toss them away today, or make a stab (sorry) at sharpening them ourselves.

In days gone by traveling professionals called scissors grinders would visit a community or farm and offer to sharpen instruments that were often not of the best quality.

In the November 16, 1886 edition of the Idaho Statesman, a short article described the profession thus:

“Most of the grinders leave town in the summer time. They commence about the first of May, and you don’t often see one carrying his machine around the city after the 1st of June. They go into the country and work in the little towns and among the farmers sharpening scissors and razors. Once in a while a $2 or $3 job is picked up in one house putting shaving tools in order and fixing the scissors.”

The chance to earn money wasn’t the only reason the grinders headed to the country in the summer.

“It don’t take much bread and meat to get along on when watermelons, cantaloupe and fruit are plenty. Potato patches and roasting ears help out a good deal, and occasionally a hen’s nest is found in some fence corner, so you see if a fellow wants to, he can live very cheap and save the money he earns.”

Grinders apparently saved up in the summer, because one needed cash to live through a winter in the city.

There was another mention of a scissors grinder in the April 18, 1891 Statesman. “A scissors grinder attracted considerable attention on the street. He was the first who has been in town for a long time.”

Scissors grinders were included in a full-page story in 1909 when the banner headline in the Statesman read, “Humble Yet Remunerative Occupations in Boise.” Other humble jobs included stove doctor, lawn surgeon, and postcard vendor. The scissor grinder interviewed for the story said he bought his grinder for $250 and could make $3-$7 a day.

Not a fortune, maybe, but one could still put some money away. In the February 21, 1905 edition of the Mountain Home Republican, this little quip appeared: “John J. Dowd, a scissors grinder, died, leaving a fortune of $30,000. John was a sharp businessman.”

Scissors grinder near Burley, Idaho, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives, Russel Lee photographer.

Scissors grinder near Burley, Idaho, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives, Russel Lee photographer.

In days gone by traveling professionals called scissors grinders would visit a community or farm and offer to sharpen instruments that were often not of the best quality.

In the November 16, 1886 edition of the Idaho Statesman, a short article described the profession thus:

“Most of the grinders leave town in the summer time. They commence about the first of May, and you don’t often see one carrying his machine around the city after the 1st of June. They go into the country and work in the little towns and among the farmers sharpening scissors and razors. Once in a while a $2 or $3 job is picked up in one house putting shaving tools in order and fixing the scissors.”

The chance to earn money wasn’t the only reason the grinders headed to the country in the summer.

“It don’t take much bread and meat to get along on when watermelons, cantaloupe and fruit are plenty. Potato patches and roasting ears help out a good deal, and occasionally a hen’s nest is found in some fence corner, so you see if a fellow wants to, he can live very cheap and save the money he earns.”

Grinders apparently saved up in the summer, because one needed cash to live through a winter in the city.

There was another mention of a scissors grinder in the April 18, 1891 Statesman. “A scissors grinder attracted considerable attention on the street. He was the first who has been in town for a long time.”

Scissors grinders were included in a full-page story in 1909 when the banner headline in the Statesman read, “Humble Yet Remunerative Occupations in Boise.” Other humble jobs included stove doctor, lawn surgeon, and postcard vendor. The scissor grinder interviewed for the story said he bought his grinder for $250 and could make $3-$7 a day.

Not a fortune, maybe, but one could still put some money away. In the February 21, 1905 edition of the Mountain Home Republican, this little quip appeared: “John J. Dowd, a scissors grinder, died, leaving a fortune of $30,000. John was a sharp businessman.”

Scissors grinder near Burley, Idaho, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives, Russel Lee photographer.

Scissors grinder near Burley, Idaho, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives, Russel Lee photographer.

Published on July 15, 2020 04:00

July 14, 2020

The Desmet Fires

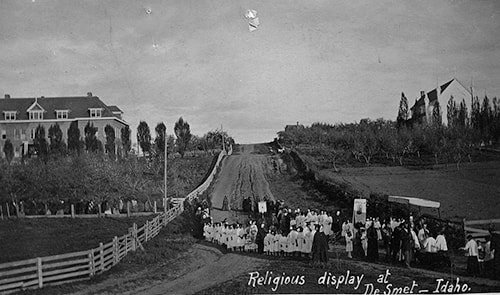

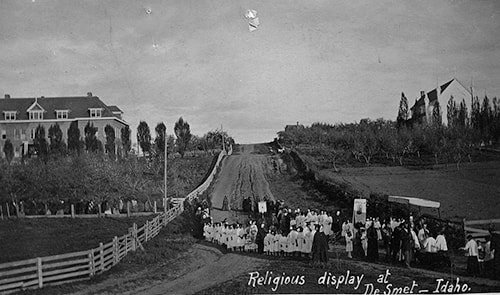

In this postcard image taken some time before 1939, the Mary Immaculate School in Desmet is on the left, while the Gothic style Sacred Heart church is on the right. Both structures would end in flames, though 72 years apart.

The first to burn was the Sacred Heart church of the Jesuit mission on April 2, 1939. Archbishop Seghers, the first bishop of the Pacific northwest and Alaska, had placed the cornerstone of the church in 1881. A legend about the fate of the church is told at the Museum of North Idaho. An elderly Coeur d’Alene named Agatha Timothy is said to have loved the church so much that she vowed to “take it to heaven with her.” The day after she died a furnace explosion caused the fire that destroyed the building.

The nearby Mary Immaculate School, run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence was built in 1892 as a boarding school for girls. It was one of many built across the West, with, perhaps, the best of intentions. Often the schools served to educate, but also separate Native American students from their families. The school closed in 1974. It burned on Feb. 3, 2011. The landmark building on the hill above DeSmet was on the National Register of Historic Places. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe is planning the Sister’s Building Park and Gathering Area on the site. It will include interpretive panels telling the history of the area.

The first to burn was the Sacred Heart church of the Jesuit mission on April 2, 1939. Archbishop Seghers, the first bishop of the Pacific northwest and Alaska, had placed the cornerstone of the church in 1881. A legend about the fate of the church is told at the Museum of North Idaho. An elderly Coeur d’Alene named Agatha Timothy is said to have loved the church so much that she vowed to “take it to heaven with her.” The day after she died a furnace explosion caused the fire that destroyed the building.

The nearby Mary Immaculate School, run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence was built in 1892 as a boarding school for girls. It was one of many built across the West, with, perhaps, the best of intentions. Often the schools served to educate, but also separate Native American students from their families. The school closed in 1974. It burned on Feb. 3, 2011. The landmark building on the hill above DeSmet was on the National Register of Historic Places. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe is planning the Sister’s Building Park and Gathering Area on the site. It will include interpretive panels telling the history of the area.

Published on July 14, 2020 04:00