Rick Just's Blog, page 156

July 13, 2020

Dandy Lion Wine

Four years before the national prohibition of liquor, Idaho became a prohibition state on January 1, 1916. The Idaho Statesman seemed to treat it with good humor, lamenting that it "Would deprive many men of the only home they ever had." (See image)

But there also seemed an element in the paper, as there was in society in general, that had mixed opinions about it. On May 19, 1916, the Statesman reported on an alarming increase in dandelion wine in Boise: "Many owners of dandelion infested lawns have marveled lately at the number of children and grownups who asked permission to help extricate the little golden nuisances 'for a medicine that mother makes,' and have been enthusiastically granted permission.

"It has now earned the manufacture of dandelion wine has been carried on in many Boise homes in large quantities this spring."

State Chemist Jackson (no first name given) tested some of mamma's medicine and found it came in at 12.6 percent alcohol. He opined that perhaps it should be called "Dandy Lion" wine, because of its alcohol content.

The newspaper extolled the wine's virtues as a liver medicine, but cautioned that "many a strict prohibition mother is probably making the wine, never dreaming that she is a lawbreaker."

With those warnings out of the way, the paper proceeded to give a complete recipe for making the wine.

But there also seemed an element in the paper, as there was in society in general, that had mixed opinions about it. On May 19, 1916, the Statesman reported on an alarming increase in dandelion wine in Boise: "Many owners of dandelion infested lawns have marveled lately at the number of children and grownups who asked permission to help extricate the little golden nuisances 'for a medicine that mother makes,' and have been enthusiastically granted permission.

"It has now earned the manufacture of dandelion wine has been carried on in many Boise homes in large quantities this spring."

State Chemist Jackson (no first name given) tested some of mamma's medicine and found it came in at 12.6 percent alcohol. He opined that perhaps it should be called "Dandy Lion" wine, because of its alcohol content.

The newspaper extolled the wine's virtues as a liver medicine, but cautioned that "many a strict prohibition mother is probably making the wine, never dreaming that she is a lawbreaker."

With those warnings out of the way, the paper proceeded to give a complete recipe for making the wine.

Published on July 13, 2020 04:00

July 12, 2020

The Coeur d'Alene USO Fire

In 1935, Coeur d’Alene city leaders began talking about the need for a civic auditorium. Money is always tight for such aspirational projects, but the mission of the Works Project Administration (WPA), the largest agency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal program, was to create jobs. Building the city an auditorium would generate jobs during construction, and serve the community well into the future.

With the WPA putting up 65 percent of construction costs and providing the labor, work was begun on the auditorium in 1936. It hosted some events before its completion but wasn’t fully open until 1938.

It became the USO-Civic Auditorium in 1942 when military officials and USO personnel approached the city about providing off-base entertainment services for the “boots” at the new Farragut Naval Training Station (FNTS), and smaller military facilities in the area. The United Service Organization (USO), a non-profit dedicated to providing entertainment to US troops, took over the operation of the building with the understanding that it would be returned to the City of Coeur d’Alene when it was no longer needed as a USO.

The beautiful log building (pictured) was in a city park adjacent to Lake Coeur d’Alene. Service members could enjoy the beach, weather permitting, and take part in dances, play ping pong, see movies, and just enjoy a little free time. More than 2,000 sailors a day visited the USO during its peak.

On October 9, 1945, a 17-year-old recruit from Farragut boarded a bus with fellow boots for a little R and R in town. William Barna, from New Jersey, had been at FNTS only three weeks. A 6th-grade drop-out, Barna had no explanation for his actions that night. What he did was methodically tear stuffing from the upholstery in three cars in preparation for lighting them on fire. Then, he went into the USO and surreptitiously unlocked a back door so he could get back in after the building was closed for the night. When the patrons and staff were gone, Barna entered through the door and began pulling down curtains. He piled them on the floor along with wads of paper, and set it all on fire.

The three cars and the log USO-Civic Auditorium went up in flames, a devastating loss to the community.

Barna was convicted of second-degree arson and given 5 to 10 years in the state prison. He served only four years before being released in 1949.

Much of the material for this post was taken from an article written by Don Pischner in the summer 2012 edition of the Museum of Northern Idaho’s newsletter.

With the WPA putting up 65 percent of construction costs and providing the labor, work was begun on the auditorium in 1936. It hosted some events before its completion but wasn’t fully open until 1938.

It became the USO-Civic Auditorium in 1942 when military officials and USO personnel approached the city about providing off-base entertainment services for the “boots” at the new Farragut Naval Training Station (FNTS), and smaller military facilities in the area. The United Service Organization (USO), a non-profit dedicated to providing entertainment to US troops, took over the operation of the building with the understanding that it would be returned to the City of Coeur d’Alene when it was no longer needed as a USO.

The beautiful log building (pictured) was in a city park adjacent to Lake Coeur d’Alene. Service members could enjoy the beach, weather permitting, and take part in dances, play ping pong, see movies, and just enjoy a little free time. More than 2,000 sailors a day visited the USO during its peak.

On October 9, 1945, a 17-year-old recruit from Farragut boarded a bus with fellow boots for a little R and R in town. William Barna, from New Jersey, had been at FNTS only three weeks. A 6th-grade drop-out, Barna had no explanation for his actions that night. What he did was methodically tear stuffing from the upholstery in three cars in preparation for lighting them on fire. Then, he went into the USO and surreptitiously unlocked a back door so he could get back in after the building was closed for the night. When the patrons and staff were gone, Barna entered through the door and began pulling down curtains. He piled them on the floor along with wads of paper, and set it all on fire.

The three cars and the log USO-Civic Auditorium went up in flames, a devastating loss to the community.

Barna was convicted of second-degree arson and given 5 to 10 years in the state prison. He served only four years before being released in 1949.

Much of the material for this post was taken from an article written by Don Pischner in the summer 2012 edition of the Museum of Northern Idaho’s newsletter.

Published on July 12, 2020 04:00

July 11, 2020

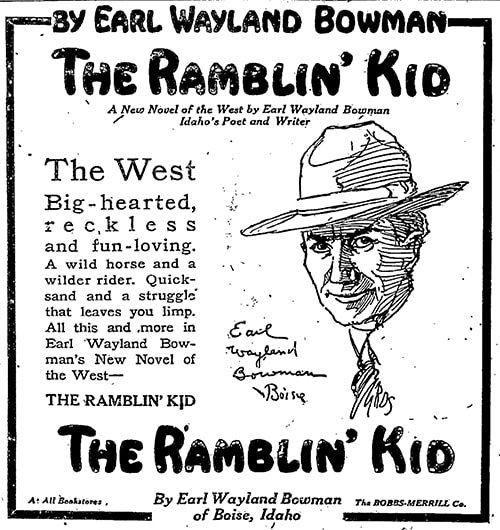

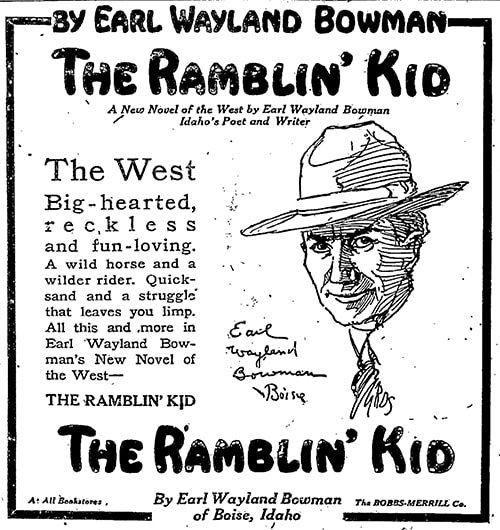

The Ramblin' Kid

If you’ve been reading these posts for a while you might remember that Agnes Just Reid, my great aunt, corresponded with several Western writers in her day, including B.M. Bower and Frank Robertson. One of Bower’s books, Ranch of the Wolverine, was written while she was staying with Agnes.

The family has some correspondence and other clues and scraps about another writer she was friends with. He went by the nickname “The Ramblin’ Kid.” In his correspondence he would sometimes refer to Agnes as “The Range Cayuse,” after a book of poetry she wrote of the same name. The Ramblin’ Kid was a successful novel by the author, whose real name was Earl Wayland Bowman. I had done enough research to know that he wrote several books and some screenplays but I got distracted by some shiny object before I could dig up his Idaho connection.

Today, I did the requisite digging and found his Idaho roots run deep, though he was born in Missouri in 1875. Orphaned at about age 10, he spent many years knocking around Texas and the Southwest working any cowboy kind of job that came his way. This early experience would serve him well as a writer of the American West.

Somewhere along the line he learned how to set type and made his living as a traveling printer. It seemed only natural that he would come up with something to print.

He and his wife, Elva, moved to Idaho in 1901, living first in Weiser, then on a ranch he built up near Council. He began writing for a number of local papers, everything from letters to the editor to poetry. The latter was dense with a religious slant, but apparently popular with readers. He wrote poems regularly for the Idaho Statesman for several years.

Bowman started a periodical titled Homeseekers Monthly, essentially a real estate rag. It later morphed into a magazine called The Golden Trail. It featured short stories, poetry, and articles about Idaho written by Bowman and other writers. It was in The Golden Trail that he began developing his persona as “The Ramblin’ Kid.”

A frequent orator at political gatherings of the day, Bowman somehow got himself elected as an Idaho State Senator in 1914. I’m not the only one who finds this startling. “The Ramblin’ Kid” was a socialist and the only state senator of that persuasion ever elected in Idaho. He got several bills through the Legislature, including the Emergency Employment Act, which put the burden on counties to create jobs for everyone who needed one. Counties heartily resisted it. The Idaho Supreme Court found it unconstitutional 18 months later. Bowman lost the next election and went back to writing.

He passed away in southern California in 1952. His family donated Bowman’s papers to Boise State College in 1972.

Among those papers was a 1923 letter to Agnes Just Reid in which he groused about a letter he had received from the California State Librarian who wanted biographical information on him as a California author. He replied, the he was “an Idaho author if any kind,” and added to Agnes, “I’m all Idaho and want to stay that way.”

For more on Bowman, visit the Special Collections and Archives page on the Boise State University Library website, from which much of this information was gathered.

The family has some correspondence and other clues and scraps about another writer she was friends with. He went by the nickname “The Ramblin’ Kid.” In his correspondence he would sometimes refer to Agnes as “The Range Cayuse,” after a book of poetry she wrote of the same name. The Ramblin’ Kid was a successful novel by the author, whose real name was Earl Wayland Bowman. I had done enough research to know that he wrote several books and some screenplays but I got distracted by some shiny object before I could dig up his Idaho connection.

Today, I did the requisite digging and found his Idaho roots run deep, though he was born in Missouri in 1875. Orphaned at about age 10, he spent many years knocking around Texas and the Southwest working any cowboy kind of job that came his way. This early experience would serve him well as a writer of the American West.

Somewhere along the line he learned how to set type and made his living as a traveling printer. It seemed only natural that he would come up with something to print.

He and his wife, Elva, moved to Idaho in 1901, living first in Weiser, then on a ranch he built up near Council. He began writing for a number of local papers, everything from letters to the editor to poetry. The latter was dense with a religious slant, but apparently popular with readers. He wrote poems regularly for the Idaho Statesman for several years.

Bowman started a periodical titled Homeseekers Monthly, essentially a real estate rag. It later morphed into a magazine called The Golden Trail. It featured short stories, poetry, and articles about Idaho written by Bowman and other writers. It was in The Golden Trail that he began developing his persona as “The Ramblin’ Kid.”

A frequent orator at political gatherings of the day, Bowman somehow got himself elected as an Idaho State Senator in 1914. I’m not the only one who finds this startling. “The Ramblin’ Kid” was a socialist and the only state senator of that persuasion ever elected in Idaho. He got several bills through the Legislature, including the Emergency Employment Act, which put the burden on counties to create jobs for everyone who needed one. Counties heartily resisted it. The Idaho Supreme Court found it unconstitutional 18 months later. Bowman lost the next election and went back to writing.

He passed away in southern California in 1952. His family donated Bowman’s papers to Boise State College in 1972.

Among those papers was a 1923 letter to Agnes Just Reid in which he groused about a letter he had received from the California State Librarian who wanted biographical information on him as a California author. He replied, the he was “an Idaho author if any kind,” and added to Agnes, “I’m all Idaho and want to stay that way.”

For more on Bowman, visit the Special Collections and Archives page on the Boise State University Library website, from which much of this information was gathered.

Published on July 11, 2020 04:00

July 10, 2020

Blister Rust

Blister rust is native to China, and was accidentally introduced to North America around 1900. It is devastating to white pines and, in turn, the ecosystems around them. The complex life cycle of blister rust requires two hosts, white pine, and currant or gooseberry plants. Some Indian paint brush has also been detected with blister rust.

If blister rust is discovered on a few limbs of a tree, and those limbs are pruned, the tree may be saved. If it is infecting the trunk of the tree, it will be lost. Pruning, while somewhat effective, is costly and time-consuming.

Battling white pine blister rust kept many young men of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) busy. In this photo, taken in 1933 by K.D. Swan and courtesy of the Museum of North Idaho, the young man in the foreground is using string to mark off a 25-foot area where all the host plants (currants and gooseberries) were to be pulled. In the background, other CCCs are pulling up the plants. All the host plants in the area had to be destroyed.

If blister rust is discovered on a few limbs of a tree, and those limbs are pruned, the tree may be saved. If it is infecting the trunk of the tree, it will be lost. Pruning, while somewhat effective, is costly and time-consuming.

Battling white pine blister rust kept many young men of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) busy. In this photo, taken in 1933 by K.D. Swan and courtesy of the Museum of North Idaho, the young man in the foreground is using string to mark off a 25-foot area where all the host plants (currants and gooseberries) were to be pulled. In the background, other CCCs are pulling up the plants. All the host plants in the area had to be destroyed.

Published on July 10, 2020 04:00

July 9, 2020

The Capitol Gets its Wings

The Idaho capitol couldn’t fly until it had wings. Old pictures of the statehouse with its familiar dome, spreading stairs, and soaring columns, sans the senate and house wings make the whole thing look a little stubby. The east and west additions balanced the look of the building and made it much more functional.

Adding the wings wasn’t as easy as it might seem. First, Legislators had to haggle over an appropriations bill. That gave members from eastern Idaho an excuse to bring up the idea of moving the capital halfway across the state, specifically to Shoshone. They thought the existing building would make a fine university. The idea did not have wings.

Once $900,000 was appropriated for construction of the additions, there was the matter of the state not actually owning the property where they were to go. Boiseans were asked to pass a bond of $135,000 to purchase the property where the wings would be built. The newly acquired property would later be swapped with the state.

Once the Boise bond was passed, the structures on the property had to go away. They included the Central School building, which was being used at the time by the state agriculture department. The Sherman House, a fashionable boarding house once owned by the sister of Mary Hallock Foote would come down, as would Collister Flats, the Aloha Apartments, and four small residences.

The wings, which now host the chambers of the house and senate as well as other state offices, were completed in 1920. The Idaho State Capitol prior to 1920.

The Idaho State Capitol prior to 1920.

Adding the wings wasn’t as easy as it might seem. First, Legislators had to haggle over an appropriations bill. That gave members from eastern Idaho an excuse to bring up the idea of moving the capital halfway across the state, specifically to Shoshone. They thought the existing building would make a fine university. The idea did not have wings.

Once $900,000 was appropriated for construction of the additions, there was the matter of the state not actually owning the property where they were to go. Boiseans were asked to pass a bond of $135,000 to purchase the property where the wings would be built. The newly acquired property would later be swapped with the state.

Once the Boise bond was passed, the structures on the property had to go away. They included the Central School building, which was being used at the time by the state agriculture department. The Sherman House, a fashionable boarding house once owned by the sister of Mary Hallock Foote would come down, as would Collister Flats, the Aloha Apartments, and four small residences.

The wings, which now host the chambers of the house and senate as well as other state offices, were completed in 1920.

The Idaho State Capitol prior to 1920.

The Idaho State Capitol prior to 1920.

Published on July 09, 2020 04:00

July 8, 2020

An Irrigation Story from the Home Place

People who move into the state and even many Idaho natives often know little about how important irrigation is. Without it, the southern part of the state would be what it had been for millennia, a desert.

This came to mind while I was doing some research on Idaho pioneer Presto Burrell for a family magazine I edit. My family isn’t related to Burrell, but he was important enough in our history that our magazine is called Presto Press, named after him, as was the community of ranches where I grew up, near Blackfoot. It is called Lower Presto.

The April 29, 1910, issue of the Idaho Republican, a Blackfoot newspaper had the following under the heading, Blackfoot A Historic Spot.

“The newspapers of the state are giving Blackfoot some publicity on account of the fact that this is the fortieth anniversary of the building of the first irrigating ditches in the upper Snake River Valley. Now, within four decades we have more mileage of canals and more acreage of irrigable lands than any other county in the United States, and the marvelous development of forty years, for things move rapidly now.

“It was in 1870 that Fred S. Stevens, Presto Burrell, and Henry Dunn made their first ditches to convey water out upon the soil and they are all living and making money out of the products being raised each year by the same ditches on the same lands. Their work was experimental and the present prosperous population is reaping the benefit of the demonstrations they made.”

My great grandparents, Nels and Emma Just moved to the valley in which Presto Burrell settled, just a few months after he did. In later years Emma would be the postmistress for the area and Nels would suggest the name Presto for the post office. That’s how the area got its name, something Mr. Burrell was never comfortable with.

So, I grew up in that little valley where one of the first irrigation ditches in Bingham County was dug by Presto Burrell (photo). Family members—cousins—still farm and ranch in the valley.

This came to mind while I was doing some research on Idaho pioneer Presto Burrell for a family magazine I edit. My family isn’t related to Burrell, but he was important enough in our history that our magazine is called Presto Press, named after him, as was the community of ranches where I grew up, near Blackfoot. It is called Lower Presto.

The April 29, 1910, issue of the Idaho Republican, a Blackfoot newspaper had the following under the heading, Blackfoot A Historic Spot.

“The newspapers of the state are giving Blackfoot some publicity on account of the fact that this is the fortieth anniversary of the building of the first irrigating ditches in the upper Snake River Valley. Now, within four decades we have more mileage of canals and more acreage of irrigable lands than any other county in the United States, and the marvelous development of forty years, for things move rapidly now.

“It was in 1870 that Fred S. Stevens, Presto Burrell, and Henry Dunn made their first ditches to convey water out upon the soil and they are all living and making money out of the products being raised each year by the same ditches on the same lands. Their work was experimental and the present prosperous population is reaping the benefit of the demonstrations they made.”

My great grandparents, Nels and Emma Just moved to the valley in which Presto Burrell settled, just a few months after he did. In later years Emma would be the postmistress for the area and Nels would suggest the name Presto for the post office. That’s how the area got its name, something Mr. Burrell was never comfortable with.

So, I grew up in that little valley where one of the first irrigation ditches in Bingham County was dug by Presto Burrell (photo). Family members—cousins—still farm and ranch in the valley.

Published on July 08, 2020 04:00

July 7, 2020

The Hunt Camp Economic Boom

The internment of Americans of Japanese ancestry during World War II was devastating for those who went through it. I understand that many people at the time thought it was a necessary move, and that our feelings about it today are filtered through the lens of hindsight. For those interned there is no question that it was terrible. Today, I want to write about one aspect of the program that is seldom discussed.

Construction of the Hunt Camp at Minidoka in the summer of 1942 was the Depression-ender for the Magic Valley. Masons, carpenters, and their helpers could earn $72 a week during construction. If they could find work at all during that time, $20 to $25 a week was the norm for those trades.

Morrison-Knudsen was the contractor at the camp. The payroll for the M-K workers rolled through the Magic Valley bringing the first taste of prosperity to bars, restaurants, and clothing stores they had experienced in years. People brought their rattle-trap cars in to trade up and made long-overdue improvements to their homes.

The workers often lived in shacks and used outhouses. They were heard to grumble about the lucky “Japs” for whom they were building communal kitchens, laundries and bathhouses—luxuries the workers didn’t enjoy. No doubt the families forced to move to the Idaho desert from Portland and Seattle considered none of it luxurious.

Much of the information contained in this post comes from History of Idaho, Volume2, Leonard J. Arrington, published by the University of Idaho Press and the Idaho State Historical Society in 1994.

The Minidoka camp under construction.

The Minidoka camp under construction.

Construction of the Hunt Camp at Minidoka in the summer of 1942 was the Depression-ender for the Magic Valley. Masons, carpenters, and their helpers could earn $72 a week during construction. If they could find work at all during that time, $20 to $25 a week was the norm for those trades.

Morrison-Knudsen was the contractor at the camp. The payroll for the M-K workers rolled through the Magic Valley bringing the first taste of prosperity to bars, restaurants, and clothing stores they had experienced in years. People brought their rattle-trap cars in to trade up and made long-overdue improvements to their homes.

The workers often lived in shacks and used outhouses. They were heard to grumble about the lucky “Japs” for whom they were building communal kitchens, laundries and bathhouses—luxuries the workers didn’t enjoy. No doubt the families forced to move to the Idaho desert from Portland and Seattle considered none of it luxurious.

Much of the information contained in this post comes from History of Idaho, Volume2, Leonard J. Arrington, published by the University of Idaho Press and the Idaho State Historical Society in 1994.

The Minidoka camp under construction.

The Minidoka camp under construction.

Published on July 07, 2020 04:00

July 6, 2020

Beyond Hope

Residents of Hope, Idaho, take note. Here’s another of the endless opportunities to play on the name of your town by declaring that something is beyond Hope. In this case, someONE was beyond.

Hope was named in 1882 for a Doctor Hope who was a veterinarian with the Northern Pacific Railroad. But this is a beyond hope story.

It seems that a barber showed up in Sandpoint and worked in a barbershop there for a few days. He was reportedly a handsome, clean-shaven man with graying auburn hair who might have come from Kansas City.

None of that would have made the papers. His last act, did. The Spokesman Review reported that “he came to Hope Thursday evening showing signs of having been under the influence of liquor. During the evening, he flourished a razor in a hotel office and told the night clerk he would prove to the people present that he was a nervy man by cutting his own throat.”

The clerk talked quietly to the man and persuaded him to put the razor away.

But early the next morning the man was back. Quoting the paper, “at 5:30 he walked out onto the platform and five minutes later drew the razor from his breast pocket with his right hand, pulled down his shirt collar with the left hand, threw his head back and a little to one side, then drew the blade across his jugular and cut an awful gash in his throat.”

After that the report gets graphic. Suffice to say the man spent a minute or two dying. No clue about who he was could be found among his effects.

The paper dutifully reported that the coroner ruled the death a suicide.

Hope was named in 1882 for a Doctor Hope who was a veterinarian with the Northern Pacific Railroad. But this is a beyond hope story.

It seems that a barber showed up in Sandpoint and worked in a barbershop there for a few days. He was reportedly a handsome, clean-shaven man with graying auburn hair who might have come from Kansas City.

None of that would have made the papers. His last act, did. The Spokesman Review reported that “he came to Hope Thursday evening showing signs of having been under the influence of liquor. During the evening, he flourished a razor in a hotel office and told the night clerk he would prove to the people present that he was a nervy man by cutting his own throat.”

The clerk talked quietly to the man and persuaded him to put the razor away.

But early the next morning the man was back. Quoting the paper, “at 5:30 he walked out onto the platform and five minutes later drew the razor from his breast pocket with his right hand, pulled down his shirt collar with the left hand, threw his head back and a little to one side, then drew the blade across his jugular and cut an awful gash in his throat.”

After that the report gets graphic. Suffice to say the man spent a minute or two dying. No clue about who he was could be found among his effects.

The paper dutifully reported that the coroner ruled the death a suicide.

Published on July 06, 2020 04:00

July 5, 2020

Basque Boarding Houses

Assimilating into a new country and culture is not something that is done overnight. The Basques had some unique ways of coping with the stress of immigration.

You may think of Basques as sheepherders because in this country they often were. For most of them it wasn’t a way of life they had known in the Old Country. It was simply a job that they could learn quickly and one that didn’t require them to take on a new language immediately. The sheep didn’t care what language they spoke.

With themselves for company Basque Sheepherders got along fine during the warm months of the year. But what to do come winter? Their solution was to come together in Basque boarding houses where they could speak the language they knew, eat familiar food, and socialize with their own people. At the same time, the boarding houses were in towns where English was common and they could learn more about their adopted country.

During much of the Twentieth Century you could find Basque boarding houses, or ostatuak, in Boise, Caldwell, Cascade, Emmett, Gooding, Hailey, Jerome, Mackay, Mountain Home, Mullan, Nampa, Pocatelo, Rupert, Shoshone, and Twin Falls. There were more than 50 of them in Boise, alone, including one at the city’s oldest standing brick building, the Jacobs-Uberuaga House (photo), built in 1864. It became a Basque boarding house in 1910. The house is now the physical and historical center of Boise’s Basque Block.

You may think of Basques as sheepherders because in this country they often were. For most of them it wasn’t a way of life they had known in the Old Country. It was simply a job that they could learn quickly and one that didn’t require them to take on a new language immediately. The sheep didn’t care what language they spoke.

With themselves for company Basque Sheepherders got along fine during the warm months of the year. But what to do come winter? Their solution was to come together in Basque boarding houses where they could speak the language they knew, eat familiar food, and socialize with their own people. At the same time, the boarding houses were in towns where English was common and they could learn more about their adopted country.

During much of the Twentieth Century you could find Basque boarding houses, or ostatuak, in Boise, Caldwell, Cascade, Emmett, Gooding, Hailey, Jerome, Mackay, Mountain Home, Mullan, Nampa, Pocatelo, Rupert, Shoshone, and Twin Falls. There were more than 50 of them in Boise, alone, including one at the city’s oldest standing brick building, the Jacobs-Uberuaga House (photo), built in 1864. It became a Basque boarding house in 1910. The house is now the physical and historical center of Boise’s Basque Block.

Published on July 05, 2020 04:00

July 4, 2020

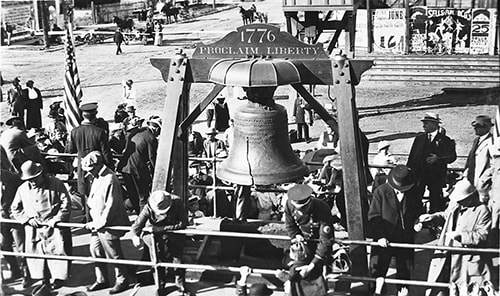

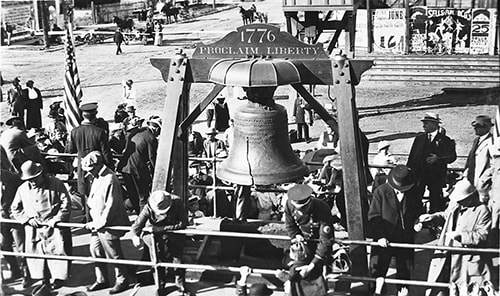

Let Freedom Ring

Have you seen the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia? Or, are you waiting for it to come to you?

Getting a visit from the bell is unlikely today, but it once travelled quite a lot to fairs and patriotic assemblages. On its most recent trip from Philadelphia it made it all the way to Idaho. That was over a hundred years ago.

The Liberty Bell was the centerpiece of a bond drive to support World War I. Mounted on a railroad flatcar it toured the United States in 1915 on its way to the Panama-Pacific International exposition in San Francisco and back. By some estimates, half the people in the country turned out to see it.

The bell was on view in Boise from 7:15 to 8 am, July 13, 1915. Between 15,000 and 20,000 people came to see it. The arrival of the bell was front page news in the Meridian Times even though the bell didn’t make a stop in Meridian. It did slow down. About 8,000 people turned out in Caldwell for the 25-minute stop there, before it steamed away into Oregon for the final leg of its trip to San Francisco.

The bell was then, and remains today, a beloved US icon. Why, exactly? Partly because of its inscription, and partly because of a popular fiction that grew up around it.

The bell was cast in London in 1752, commissioned by the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, and inscribed with a quote from Leviticus, “Proclaim LIBERTY Throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants Thereof.”

The bell cracked right away when it was first rung in Philadelphia. It was twice recast to repair it.

A popular story had it that the bell rang out on July 4, 1776, announcing the Declaration of Independence. No such announcement was made that day, but historians agree it was probably one of many bells that rang in the city on July 8, when the announcement was made.

The original crack having been repaired, the bell cracked again—and remained so—sometime in the early 19th century.

As a symbol of liberty, it was a war bond star. Americans bought an average of $170 each in the Liberty Bell war bond drives. The Liberty Bell visited Boise in 1915.

The Liberty Bell visited Boise in 1915.

Getting a visit from the bell is unlikely today, but it once travelled quite a lot to fairs and patriotic assemblages. On its most recent trip from Philadelphia it made it all the way to Idaho. That was over a hundred years ago.

The Liberty Bell was the centerpiece of a bond drive to support World War I. Mounted on a railroad flatcar it toured the United States in 1915 on its way to the Panama-Pacific International exposition in San Francisco and back. By some estimates, half the people in the country turned out to see it.

The bell was on view in Boise from 7:15 to 8 am, July 13, 1915. Between 15,000 and 20,000 people came to see it. The arrival of the bell was front page news in the Meridian Times even though the bell didn’t make a stop in Meridian. It did slow down. About 8,000 people turned out in Caldwell for the 25-minute stop there, before it steamed away into Oregon for the final leg of its trip to San Francisco.

The bell was then, and remains today, a beloved US icon. Why, exactly? Partly because of its inscription, and partly because of a popular fiction that grew up around it.

The bell was cast in London in 1752, commissioned by the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, and inscribed with a quote from Leviticus, “Proclaim LIBERTY Throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants Thereof.”

The bell cracked right away when it was first rung in Philadelphia. It was twice recast to repair it.

A popular story had it that the bell rang out on July 4, 1776, announcing the Declaration of Independence. No such announcement was made that day, but historians agree it was probably one of many bells that rang in the city on July 8, when the announcement was made.

The original crack having been repaired, the bell cracked again—and remained so—sometime in the early 19th century.

As a symbol of liberty, it was a war bond star. Americans bought an average of $170 each in the Liberty Bell war bond drives.

The Liberty Bell visited Boise in 1915.

The Liberty Bell visited Boise in 1915.

Published on July 04, 2020 04:00