Rick Just's Blog, page 152

August 29, 2020

The Name Pocatello

To say that the city of Pocatello is named after Chief Pocatello is correct. Yet, those two words, chief and Pocatello, are themselves subject to much disagreement.

The concept of “chief” was often one introduced to Native American tribes by white settlers and soldiers. Soldiers, especially, liked the supposed certainty of dealing with a single person who could speak for a tribe. The tribes themselves often held several members—often elders—in high esteem because of their various skills or wisdom. The fact that a certain chief would sign a treaty did not always mean he spoke for his tribe in doing so.

Pocatello was certainly a trusted leader of his band of Shoshonis. Most such leaders, according to historian Merle Wells, considered themselves equals. Circumstances brought on by the influx of settlers into traditional Shoshoni lands, however, made Pocatello “more equal among equals.”

There is more confusion about his name than about his rank. The name has been given several meanings over the years. Brigham D. Madsen, in his book Chief Pocatello points to the first mention of the man in the 1857 writings of an Indian agent who called him “Koctallo.” Two years later an army officer who had never met him, but had often heard his name, wrote it as “Pocataro.” Some insist that the meaning of the name is something like “he who does not take the trail” or “in the middle of the road.” Others say it may have come from the town in Georgia called Pocataligo, which may be a Yamasee or Cherokee Indian word, the meaning of which is also in dispute. Note that residents of Pocatligo often call the place “Pokey” for short, just as the residents of Pocatello do. In any case, the Georgia connection seems far-fetched.

So the whites are confused. What about his own people? Again according to Madsen, the Hukandeka Shoshoni called him Tonaioza, meaning “Buffalo Robe,” or sometimes Kanah, which is apparently a reference to the gift of an army coat given to him by Gen. Patrick E. Connor during the signing of the Treaty of Box Elder. According to his daughter, Jeanette Pocatello Lewis, Pocatello never used that name at all and always went by Tonaioza or Tondzaosha.

One popular explanation for the name still heard is that the man was well known for his love of pork and tallow. Get it? Porkantallow? One must—if one is me, at least—call BS on that one. Under what circumstances would one particularly desire those two items to the extent that he would be named for them? It seems an obvious backformation meant to belittle a man who in no way deserved it.

The concept of “chief” was often one introduced to Native American tribes by white settlers and soldiers. Soldiers, especially, liked the supposed certainty of dealing with a single person who could speak for a tribe. The tribes themselves often held several members—often elders—in high esteem because of their various skills or wisdom. The fact that a certain chief would sign a treaty did not always mean he spoke for his tribe in doing so.

Pocatello was certainly a trusted leader of his band of Shoshonis. Most such leaders, according to historian Merle Wells, considered themselves equals. Circumstances brought on by the influx of settlers into traditional Shoshoni lands, however, made Pocatello “more equal among equals.”

There is more confusion about his name than about his rank. The name has been given several meanings over the years. Brigham D. Madsen, in his book Chief Pocatello points to the first mention of the man in the 1857 writings of an Indian agent who called him “Koctallo.” Two years later an army officer who had never met him, but had often heard his name, wrote it as “Pocataro.” Some insist that the meaning of the name is something like “he who does not take the trail” or “in the middle of the road.” Others say it may have come from the town in Georgia called Pocataligo, which may be a Yamasee or Cherokee Indian word, the meaning of which is also in dispute. Note that residents of Pocatligo often call the place “Pokey” for short, just as the residents of Pocatello do. In any case, the Georgia connection seems far-fetched.

So the whites are confused. What about his own people? Again according to Madsen, the Hukandeka Shoshoni called him Tonaioza, meaning “Buffalo Robe,” or sometimes Kanah, which is apparently a reference to the gift of an army coat given to him by Gen. Patrick E. Connor during the signing of the Treaty of Box Elder. According to his daughter, Jeanette Pocatello Lewis, Pocatello never used that name at all and always went by Tonaioza or Tondzaosha.

One popular explanation for the name still heard is that the man was well known for his love of pork and tallow. Get it? Porkantallow? One must—if one is me, at least—call BS on that one. Under what circumstances would one particularly desire those two items to the extent that he would be named for them? It seems an obvious backformation meant to belittle a man who in no way deserved it.

Published on August 29, 2020 04:00

August 28, 2020

The Johnny Sack Cabin

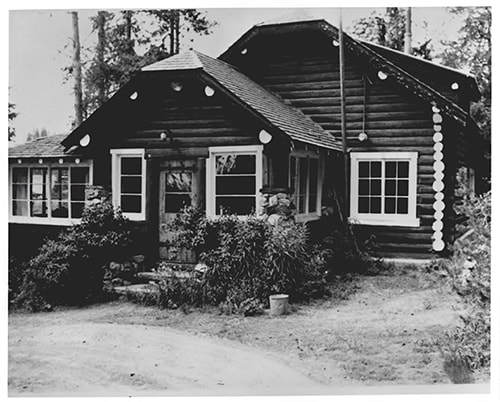

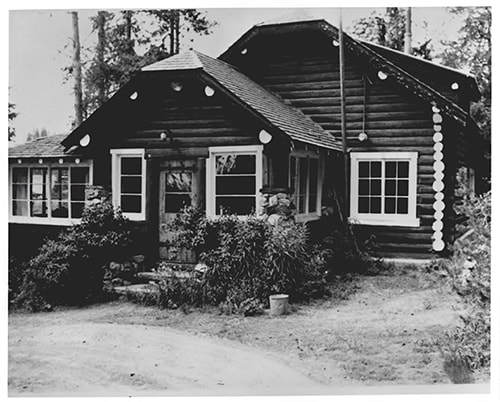

John Parsons sent me a link to a cool 3D tour of Johnny Sack’s cabin in Island Park. I decided to write a little about the cabin and share the link with you.

The cabin, built by the hands of Johnny Sack, isn’t the typical ramshackle residence you might expect from an Idaho loner. It’s a piece of art.

Sack and his brother Andy, arrived in Island Park by train in June 1909, during a blizzard, according to the Fremont County website. The brothers mostly worked cattle in the area for years before Johnny started building cabins and furniture for a living. He’d had some training working for the Studebaker Wagon Corporation, which morphed into the Studebaker car company.

In 1929, Johnny Sack leased a site at Big Springs for $4.15 a year from the Forest Service and began building his own cabin. It took about three years to complete. The main part of the log bungalow is about 20 x 27 feet. In the 1972 National Register of Historic Places application for the cabin, it states “It is considered to be the work of a master craftsman.”

You can read more about the exquisite little cabin and its builder on the website and take a virtual tour of the interior. Take special note of the unique pieces of furniture also carved and assembled by Sack.

1972 photo of the Johnny Sack cabin from its National Register of Historic Places application.

1972 photo of the Johnny Sack cabin from its National Register of Historic Places application.

The cabin, built by the hands of Johnny Sack, isn’t the typical ramshackle residence you might expect from an Idaho loner. It’s a piece of art.

Sack and his brother Andy, arrived in Island Park by train in June 1909, during a blizzard, according to the Fremont County website. The brothers mostly worked cattle in the area for years before Johnny started building cabins and furniture for a living. He’d had some training working for the Studebaker Wagon Corporation, which morphed into the Studebaker car company.

In 1929, Johnny Sack leased a site at Big Springs for $4.15 a year from the Forest Service and began building his own cabin. It took about three years to complete. The main part of the log bungalow is about 20 x 27 feet. In the 1972 National Register of Historic Places application for the cabin, it states “It is considered to be the work of a master craftsman.”

You can read more about the exquisite little cabin and its builder on the website and take a virtual tour of the interior. Take special note of the unique pieces of furniture also carved and assembled by Sack.

1972 photo of the Johnny Sack cabin from its National Register of Historic Places application.

1972 photo of the Johnny Sack cabin from its National Register of Historic Places application.

Published on August 28, 2020 04:00

August 27, 2020

The Tyee

Logging was THE industry around Priest Lake in the latter part of the 19th century and much of the 20th. Diamond Match Company cut a lot of Western white pine around the lake so that people all around the world could strike a match.

There is still some evidence of old logging operations around the lake, if you know where to look. In the Indian Creek Unit of Priest Lake State Park—the first unit on the lake you’ll come to—you’ll find a replica of a logging flume. You’ll find it on your own, right on the edge of the campground. But if you want to see the real remains of a logging flume and the remains of the old wooden dam that diverted water into the flume to float the logs, ask a ranger. There’s a road up the hillside not far away that will take you there (on foot), if you’re adventurous.

Once you’ve seen that, drive north to the Lionhead Group Camp. You’ll see some old dormitory buildings and a shower building near the white sand beach. Those buildings, which are still used today, were once part of a floating timber camp. The camp floated so they could move it around the lake to where the current cut was taking place.

Now, head up the road a mile or so to the Lionhead boat ramp. Park there and take a look at the relic of the Tyee II, sunk in the little bay, creating a picturesque scene. The Tyee II was the last wood-burning steam tugboat on the lake. It pulled a lot of logs in its day. The picture on top shows it circa 1930, while the color picture is a snap of the old hulk resting in the sand.

By the way, Tyee means chief or boss. It also refers to a large Chinook salmon.

There is still some evidence of old logging operations around the lake, if you know where to look. In the Indian Creek Unit of Priest Lake State Park—the first unit on the lake you’ll come to—you’ll find a replica of a logging flume. You’ll find it on your own, right on the edge of the campground. But if you want to see the real remains of a logging flume and the remains of the old wooden dam that diverted water into the flume to float the logs, ask a ranger. There’s a road up the hillside not far away that will take you there (on foot), if you’re adventurous.

Once you’ve seen that, drive north to the Lionhead Group Camp. You’ll see some old dormitory buildings and a shower building near the white sand beach. Those buildings, which are still used today, were once part of a floating timber camp. The camp floated so they could move it around the lake to where the current cut was taking place.

Now, head up the road a mile or so to the Lionhead boat ramp. Park there and take a look at the relic of the Tyee II, sunk in the little bay, creating a picturesque scene. The Tyee II was the last wood-burning steam tugboat on the lake. It pulled a lot of logs in its day. The picture on top shows it circa 1930, while the color picture is a snap of the old hulk resting in the sand.

By the way, Tyee means chief or boss. It also refers to a large Chinook salmon.

Published on August 27, 2020 04:00

August 26, 2020

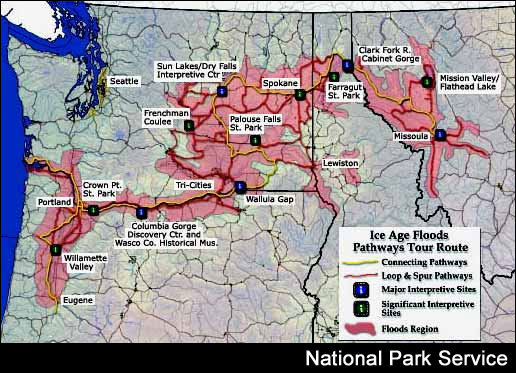

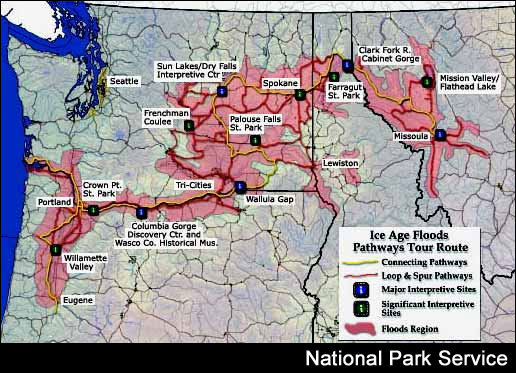

Those Monster Floods

There is some good-natured competition between north and south in our big state. Who has the best state parks? The best hunting and best fishing? The craziest politicians?

Bragging rights for one thing are really no contest. The Bonneville Flood, which roared through what is now southern Idaho about 12,000 years ago was a monster. When ancient Lake Bonneville, which covered most of what is now Utah, broke through a natural plug at Red Rock Pass it sent water crashing down the channel of the Snake River five or six times the flow of the Amazon, tearing out chunks of canyon the size of cars and tumbling the rock into rounded boulders. It drained some 600 cubic miles of water into Columbia and out to the Pacific in a matter of weeks and is said to be the second biggest flood in geologic history.

Second biggest. So, who had the first? Northern Idaho, of course.

About 15,000 years ago, during the last ice age, a huge glacier blocked the flow of the Clark Fork River near where it enters Lake Pend Oreille. Water backed up into present day Montana, forming an expansive lake that geologists call Lake Missoula. The glacial lake covered 3,000 square miles, with a depth of up to 2,000 feet.

The ice dam that created Lake Missoula could not contain it forever. When the ice finally gave

way--perhaps in the period of a day or two--a massive flood resulted.

You could not have outrun the rush of water called the Spokane Flood. It came ripping out of Idaho and into Washington at up to 80 miles per hour with the force of 500 cubic miles of water behind it. The flow may have run at 13 times the output of the Amazon. It's no wonder it scoured out 200-foot-deep canyons, and ripped the top soil away across 15,000 square miles of what is now Washington State.

The Bonneville Flood happened only once, while the Spokane Flood may have happened again and again—maybe up to 25 times—while ice dams formed and broke away.

Stay dry.

Path of the Ice Age Floods.

Path of the Ice Age Floods.

Bragging rights for one thing are really no contest. The Bonneville Flood, which roared through what is now southern Idaho about 12,000 years ago was a monster. When ancient Lake Bonneville, which covered most of what is now Utah, broke through a natural plug at Red Rock Pass it sent water crashing down the channel of the Snake River five or six times the flow of the Amazon, tearing out chunks of canyon the size of cars and tumbling the rock into rounded boulders. It drained some 600 cubic miles of water into Columbia and out to the Pacific in a matter of weeks and is said to be the second biggest flood in geologic history.

Second biggest. So, who had the first? Northern Idaho, of course.

About 15,000 years ago, during the last ice age, a huge glacier blocked the flow of the Clark Fork River near where it enters Lake Pend Oreille. Water backed up into present day Montana, forming an expansive lake that geologists call Lake Missoula. The glacial lake covered 3,000 square miles, with a depth of up to 2,000 feet.

The ice dam that created Lake Missoula could not contain it forever. When the ice finally gave

way--perhaps in the period of a day or two--a massive flood resulted.

You could not have outrun the rush of water called the Spokane Flood. It came ripping out of Idaho and into Washington at up to 80 miles per hour with the force of 500 cubic miles of water behind it. The flow may have run at 13 times the output of the Amazon. It's no wonder it scoured out 200-foot-deep canyons, and ripped the top soil away across 15,000 square miles of what is now Washington State.

The Bonneville Flood happened only once, while the Spokane Flood may have happened again and again—maybe up to 25 times—while ice dams formed and broke away.

Stay dry.

Path of the Ice Age Floods.

Path of the Ice Age Floods.

Published on August 26, 2020 04:00

August 25, 2020

The Idaho Insane Asylum

One of the more jarring things about searching through old newspapers is the prevalence of words commonly used at the time that have fallen out of favor today. Here’s a good example from a letter printed in the June 17, 1886 Wood River Times. The first line is, “The asylum is nearly ready for the reception of lunatics.” The letter was from T.T. Cabaniss, MD, the first administrator of what was then called the Idaho Insane Asylum, newly built and furnished in Blackfoot with $20,000 of taxpayer money.

The letter goes on to describe the facilities and makes a point that there was “not an iron bar in the house.” Even so, residents were commonly called inmates and were committed for life, albeit with the possibility of parole.

The community of Blackfoot was eager to have the facility on the outskirts of town. It meant jobs, and it gave local entrepreneurs the opportunity to bid on building materials in the early days, and the provision of supplies ongoing. Issues of the local papers in the years following the 1886 opening of the Idaho Insane Asylum were filled with advertisements to bid on providing clothing and food for the inmates. The list of needs went nearly A to Z, from “Apricots, evaporated” to “Yeast, magic.” The facility needed firewood, shoes for men and women, balls of darning cotton, coal, suspenders, buttons, and much more.

Once called the Idaho Insane Asylum, and later the South Idaho Sanitarium, the facility is today called State Hospital South. Residents are no longer called inmates, and the goal is providing effective treatment and recovery of Idaho's most seriously mentally ill citizens to enable their return to community living.

To Idaho’s credit the facility looks a bit like a college campus. It is located on 480 acres—most of which is leased for farming. State Hospital South has a $19 million annual budget with 300 full-time employees, serving an average of 115 patients at any given time.

The letter goes on to describe the facilities and makes a point that there was “not an iron bar in the house.” Even so, residents were commonly called inmates and were committed for life, albeit with the possibility of parole.

The community of Blackfoot was eager to have the facility on the outskirts of town. It meant jobs, and it gave local entrepreneurs the opportunity to bid on building materials in the early days, and the provision of supplies ongoing. Issues of the local papers in the years following the 1886 opening of the Idaho Insane Asylum were filled with advertisements to bid on providing clothing and food for the inmates. The list of needs went nearly A to Z, from “Apricots, evaporated” to “Yeast, magic.” The facility needed firewood, shoes for men and women, balls of darning cotton, coal, suspenders, buttons, and much more.

Once called the Idaho Insane Asylum, and later the South Idaho Sanitarium, the facility is today called State Hospital South. Residents are no longer called inmates, and the goal is providing effective treatment and recovery of Idaho's most seriously mentally ill citizens to enable their return to community living.

To Idaho’s credit the facility looks a bit like a college campus. It is located on 480 acres—most of which is leased for farming. State Hospital South has a $19 million annual budget with 300 full-time employees, serving an average of 115 patients at any given time.

Published on August 25, 2020 04:00

August 24, 2020

The Sinking Farm

Buhl doesn't get in the news much, which is probably the way the residents like it. In 1937, though, there was national attention on a farm near there. It was dubbed “the sinking farm” in newspaper headlines. Hundreds of tourists flocked to the area and Buhl residents began hiring themselves out as guides. They even started selling picture postcards of the event.

The farm was on the rim overlooking Salmon Falls Creek Canyon. Strictly speaking, the farm wasn’t so much sinking as it was falling into the canyon as erosion undercut the foundations of the canyon wall. The wall was breaking off in huge chunks like a glacier calving. Some rock would fall into the canyon and big chunks of it would sink and break and shift, making the land on top of it less than favorable for farming.

Paramount News was there to capture the event on film for newsreels. Geologists from local universities were also on hand to view the phenomenon and explain things to reporters.

Newspaper reports sometimes called it the H.A. Robertson farm. But other reports claimed it was Dr. C. C. Griffith who owned 320 acres on the canyon rim. He was away at his summer house in New York when all the excitement happened. According to a dispatch from the New York Herald-Tribune, which ran in the August 28, 1937, edition of the Idaho Statesman, he wasn’t worried about losing a few acres to the canyon. “What worries him most is the hazard the public is running invading his property.” His ranch manager, Emil Bordewick, was apoplectic about the crowds of people coming to the ranch. There was a deputy on site who wasn’t arresting anyone because wholesale arrests for trespassing might “cause a lot of trouble.” Bordewick had hired a guard. He had informed his employer it would cost $500 a month to “keep these people from getting killed.” And by the way, he wanted a raise.

Meanwhile, experts from the United States Geological Survey were not in a panic. They predicted the sinking would go on for a while. About five million years.

The grumpy ranch manager did see one potential silver lining. Well, a gold lining. He was hoping the new fissures in the earth might reveal a vein of gold.

The farm was on the rim overlooking Salmon Falls Creek Canyon. Strictly speaking, the farm wasn’t so much sinking as it was falling into the canyon as erosion undercut the foundations of the canyon wall. The wall was breaking off in huge chunks like a glacier calving. Some rock would fall into the canyon and big chunks of it would sink and break and shift, making the land on top of it less than favorable for farming.

Paramount News was there to capture the event on film for newsreels. Geologists from local universities were also on hand to view the phenomenon and explain things to reporters.

Newspaper reports sometimes called it the H.A. Robertson farm. But other reports claimed it was Dr. C. C. Griffith who owned 320 acres on the canyon rim. He was away at his summer house in New York when all the excitement happened. According to a dispatch from the New York Herald-Tribune, which ran in the August 28, 1937, edition of the Idaho Statesman, he wasn’t worried about losing a few acres to the canyon. “What worries him most is the hazard the public is running invading his property.” His ranch manager, Emil Bordewick, was apoplectic about the crowds of people coming to the ranch. There was a deputy on site who wasn’t arresting anyone because wholesale arrests for trespassing might “cause a lot of trouble.” Bordewick had hired a guard. He had informed his employer it would cost $500 a month to “keep these people from getting killed.” And by the way, he wanted a raise.

Meanwhile, experts from the United States Geological Survey were not in a panic. They predicted the sinking would go on for a while. About five million years.

The grumpy ranch manager did see one potential silver lining. Well, a gold lining. He was hoping the new fissures in the earth might reveal a vein of gold.

Published on August 24, 2020 04:00

August 23, 2020

The Bloody Death of Pearl Royal Hendrickson

Pearl Royal Hendrickson had a name that seemed aspirational. Though he lived in a ramshackle cabin in the Boise foothills, he was not without aspiration. Hendrickson was looking for wealth in the hills above Boise, like countless miners before him all across the State of Idaho. With the wealth, had he found it, might have come fame. Instead, his hunt for gallium would bring him only infamy.

His quest for gallium seems a little odd. Today the soft, silvery metal is used in electronic circuit boards, semiconductors, and LEDs. Why he thought it valuable in 1940 is open to conjecture. Gallium is akin to mercury in that it softens to a liquid when held in your hand. Playing with mercury that way is dangerous, but gallium seems relatively safe. Perhaps the changeable nature of the element held some fascination for Hendrickson.

Hendrickson was often called a squatter, though he may have originally had permission from the property owner to build his cabin on the foothills ridge near Bogus Basin. He and the landowner came to a dispute in 1936 when Hendrickson cut a cord of wood from the nearby forest. The property owner took him to court. Scant coverage of the matter appeared in the Idaho Statesman at the time, focusing mostly on the cost of the trials—an estimated $100—as compared with the value of the wood, $5. Two juries heard the case. The first couldn’t agree on a verdict and the second found Hendrickson not guilty.

The squatter was back in court again in 1939, this time fighting for his mineral rights in federal court against the Forest Service. Squatter was the appropriate term for the man by that time, because the Forest Service had purchased the property where he lived and wanted him off. Their argument against his mineral rights claim was that no mineral of worth had been discovered. This time Hendrickson lost the case.

In the early morning of Wednesday, July 31, 1940, Deputy U.S. Marshall John Glenn and Boise Police Captain George Haskin caught a cab and took it up the dirt road into the foothills for the purpose of serving a contempt of court citation to Hendrickson. They left the cab and driver on the road and walked in to Hendrickson’s cabin, about three quarters of a mile away.

While Haskin covered the window of the cabin, Glenn pounded on the door and roused Hendrickson. The Marshall said a few words about why they were there. Hendrickson, who had frequently said they would have to take him from his cabin boots first, shot the man twice. Glenn staggered away a few feet and fell dead. Haskin ran around the cabin and took cover. A few minutes later he made his way back to the taxi, and then back to town for reinforcements.

About 8 am law enforcement began to arrive at the cabin. U.S. Marshall George Meffan was the first, driving his car right up to the cabin where it stalled. Before he could get out Hendrickson shot him dead behind the wheel.

That’s when the siege—and that’s the word for it—began. Law enforcement officers from Boise, Ada County, Idaho City, Moscow, and the FBI surrounded the cabin and fired into it with everything they had for hours. And they had a lot. They used rifles, pistols, submachine guns, and even sticks of dynamite on Hendrickson. Sheltering in bushes and watching the situation develop were the county coroner and “girl reporter” Nina Varian. The fight went on for some four hours.

Varian, under the headline, “Girl Reporter Describes Tragic Drama of Man-Hunt; Negro Was Obsessed,” described it this way: “I saw grisly hell let loose in a lovely heaven of blue sky, green timber, gold sunshine. I crouched in soft, brown earth against hot gray rocks as the whine and roar of guns blasted all around me… I looked at two dead men—one sprawled like a blue lump on the ground, the other slumped over the wheel of his car, an inert mass; and I watched the frail hut that housed a doomed man.

“It was a man-hunt. Grim, relentless, terrible. Avenging man, hunting his kind; ruled by emotions muddied up from the dregs of ages past. I know now what ugly things are covered by the cloak of civilization.”

The outcome was never in doubt once the shooting started. Hendrickson fought for hours using his own weapons and the weapons of the men he killed. Eventually, he himself was killed.

The battle was covered on three pages of the newspaper on August 1, with stories from eyewitnesses, a timeline, multiple photos, and a sketch of scene. “Girl reporter” wasn’t the only term that jars today. Hendrickson was referred to as a negro and a colored man, both terms long since put to rest in most newspapers. The photos included one of Glenn’s body being unceremoniously carried away by two men.

Pearl Royal Hendrickson, 50, was carried off the same way, feet first, as he had promised many times if officials tried to evict him.

One of four pages of coverage of the Hendrickson incident.

One of four pages of coverage of the Hendrickson incident.

His quest for gallium seems a little odd. Today the soft, silvery metal is used in electronic circuit boards, semiconductors, and LEDs. Why he thought it valuable in 1940 is open to conjecture. Gallium is akin to mercury in that it softens to a liquid when held in your hand. Playing with mercury that way is dangerous, but gallium seems relatively safe. Perhaps the changeable nature of the element held some fascination for Hendrickson.

Hendrickson was often called a squatter, though he may have originally had permission from the property owner to build his cabin on the foothills ridge near Bogus Basin. He and the landowner came to a dispute in 1936 when Hendrickson cut a cord of wood from the nearby forest. The property owner took him to court. Scant coverage of the matter appeared in the Idaho Statesman at the time, focusing mostly on the cost of the trials—an estimated $100—as compared with the value of the wood, $5. Two juries heard the case. The first couldn’t agree on a verdict and the second found Hendrickson not guilty.

The squatter was back in court again in 1939, this time fighting for his mineral rights in federal court against the Forest Service. Squatter was the appropriate term for the man by that time, because the Forest Service had purchased the property where he lived and wanted him off. Their argument against his mineral rights claim was that no mineral of worth had been discovered. This time Hendrickson lost the case.

In the early morning of Wednesday, July 31, 1940, Deputy U.S. Marshall John Glenn and Boise Police Captain George Haskin caught a cab and took it up the dirt road into the foothills for the purpose of serving a contempt of court citation to Hendrickson. They left the cab and driver on the road and walked in to Hendrickson’s cabin, about three quarters of a mile away.

While Haskin covered the window of the cabin, Glenn pounded on the door and roused Hendrickson. The Marshall said a few words about why they were there. Hendrickson, who had frequently said they would have to take him from his cabin boots first, shot the man twice. Glenn staggered away a few feet and fell dead. Haskin ran around the cabin and took cover. A few minutes later he made his way back to the taxi, and then back to town for reinforcements.

About 8 am law enforcement began to arrive at the cabin. U.S. Marshall George Meffan was the first, driving his car right up to the cabin where it stalled. Before he could get out Hendrickson shot him dead behind the wheel.

That’s when the siege—and that’s the word for it—began. Law enforcement officers from Boise, Ada County, Idaho City, Moscow, and the FBI surrounded the cabin and fired into it with everything they had for hours. And they had a lot. They used rifles, pistols, submachine guns, and even sticks of dynamite on Hendrickson. Sheltering in bushes and watching the situation develop were the county coroner and “girl reporter” Nina Varian. The fight went on for some four hours.

Varian, under the headline, “Girl Reporter Describes Tragic Drama of Man-Hunt; Negro Was Obsessed,” described it this way: “I saw grisly hell let loose in a lovely heaven of blue sky, green timber, gold sunshine. I crouched in soft, brown earth against hot gray rocks as the whine and roar of guns blasted all around me… I looked at two dead men—one sprawled like a blue lump on the ground, the other slumped over the wheel of his car, an inert mass; and I watched the frail hut that housed a doomed man.

“It was a man-hunt. Grim, relentless, terrible. Avenging man, hunting his kind; ruled by emotions muddied up from the dregs of ages past. I know now what ugly things are covered by the cloak of civilization.”

The outcome was never in doubt once the shooting started. Hendrickson fought for hours using his own weapons and the weapons of the men he killed. Eventually, he himself was killed.

The battle was covered on three pages of the newspaper on August 1, with stories from eyewitnesses, a timeline, multiple photos, and a sketch of scene. “Girl reporter” wasn’t the only term that jars today. Hendrickson was referred to as a negro and a colored man, both terms long since put to rest in most newspapers. The photos included one of Glenn’s body being unceremoniously carried away by two men.

Pearl Royal Hendrickson, 50, was carried off the same way, feet first, as he had promised many times if officials tried to evict him.

One of four pages of coverage of the Hendrickson incident.

One of four pages of coverage of the Hendrickson incident.

Published on August 23, 2020 04:00

August 22, 2020

Idaho's Response to the Great San Francisco Earthquake

Idaho history often includes events that took place out of state, but which impacted Idaho residents. One such event was the earthquake that hit San Francisco on April 18, 1906. Just five days later the Idaho Daily Statesman compiled a list of what communities where doing and the funds they had already raised for San Francisco relief.

Boise had raised $8,258.50. Caldwell, Paris, Genessee, and Lewiston had each shipped a car of flour. Payette was arranging for “a large amount of food (to be) cooked and shipped no later than tomorrow evening. It is the plan to buy out the remaining stock of canned goods of the cannery and ship it.”

The Commercial Club in Mountain Home had raise $100 and the city had matched it. The Commercial Club in Hailey raise $321.75 in an hour and a half. Blackfoot had raised $100 so far. Cambridge was ready to contribute $71.50. Sugar City had raised $250. Montpelier contributed $180.

Lewiston had already raised $2,000 with a goal of $3,000. Sandpoint was planning a ball to raise money. Coeur d’Alene had raised $300 and was putting on a benefit minstrel show. Moscow had sent a car of supplies and was planning to send more.

The CPI inflation calculator goes back only to 1913. Using that year as a base, $100 in 1906 was about the equivalent of $2500 today. Just the dollars reported on that fifth day after the earthquake would be nearly $300,000 in today’s dollars. Idaho at that time had about 165,000 residents.

The generosity of Idahoans is laudable. It’s worth noting that the earthquake brought something special to the state. For a few weeks Riverside Park in Boise hosted the San Francisco Opera Company. How special was it? The Idaho Statesman reported that “Never until the earthquake in April could the old Tivoli company be induced to leave San Francisco. But after that catastrophe, it was recognized that there would be no room for amusements in the stricken city for many months, and the members of the company, some of whom had been playing at the historic old playhouse for many years, left the California metropolis with many fears and misgivings, all hoping that the time of their banishment might be short.”

Riverside Park paid the company $2,000 a week while they were in town. Perhaps they made some money from the engagement. There was no shortage of efforts to make a buck off the disaster. Dozens of advertisements looking for agents to sell copies of competing books about the disaster began appearing on April 27 and continued for weeks. One local ad in Boise offered six carloads of pianos that had been enroute to San Francisco that were to be “sacrificed” for $187 to $327. “Suffice it to say that no combination of circumstances has ever brought piano prices so low as appear on our price tags now.” What good luck!

Boise had raised $8,258.50. Caldwell, Paris, Genessee, and Lewiston had each shipped a car of flour. Payette was arranging for “a large amount of food (to be) cooked and shipped no later than tomorrow evening. It is the plan to buy out the remaining stock of canned goods of the cannery and ship it.”

The Commercial Club in Mountain Home had raise $100 and the city had matched it. The Commercial Club in Hailey raise $321.75 in an hour and a half. Blackfoot had raised $100 so far. Cambridge was ready to contribute $71.50. Sugar City had raised $250. Montpelier contributed $180.

Lewiston had already raised $2,000 with a goal of $3,000. Sandpoint was planning a ball to raise money. Coeur d’Alene had raised $300 and was putting on a benefit minstrel show. Moscow had sent a car of supplies and was planning to send more.

The CPI inflation calculator goes back only to 1913. Using that year as a base, $100 in 1906 was about the equivalent of $2500 today. Just the dollars reported on that fifth day after the earthquake would be nearly $300,000 in today’s dollars. Idaho at that time had about 165,000 residents.

The generosity of Idahoans is laudable. It’s worth noting that the earthquake brought something special to the state. For a few weeks Riverside Park in Boise hosted the San Francisco Opera Company. How special was it? The Idaho Statesman reported that “Never until the earthquake in April could the old Tivoli company be induced to leave San Francisco. But after that catastrophe, it was recognized that there would be no room for amusements in the stricken city for many months, and the members of the company, some of whom had been playing at the historic old playhouse for many years, left the California metropolis with many fears and misgivings, all hoping that the time of their banishment might be short.”

Riverside Park paid the company $2,000 a week while they were in town. Perhaps they made some money from the engagement. There was no shortage of efforts to make a buck off the disaster. Dozens of advertisements looking for agents to sell copies of competing books about the disaster began appearing on April 27 and continued for weeks. One local ad in Boise offered six carloads of pianos that had been enroute to San Francisco that were to be “sacrificed” for $187 to $327. “Suffice it to say that no combination of circumstances has ever brought piano prices so low as appear on our price tags now.” What good luck!

Published on August 22, 2020 04:00

August 21, 2020

Sunbeam Dam

Today, when gathering energy from the sun through solar collectors is common, the word sunbeam as it pertains to energy is positive. The same was true in 1910 when the Sunbeam Dam was constructed on the Salmon River. It would positively power the Sunbeam mining operation up Jordan Creek from the new dam.

A new power source was needed because the area had been logged out partly to supply fuel for a steam-powered mill. Without logs, that mill couldn’t run. Without the mill to process raw ore, there was no point mining.

Sunbeam Dam to the rescue. It took 300 tons of concrete to build the dam, which was 95 feet wide and 35 feet high. The dam produced cheap electricity for the mine for a year. But the low grade of the ore coming out of Jordan Creek couldn’t make the operation pay, no matter how cheap the electricity was.

The dam, and other mining properties, were sold at a sheriff’s auction in 1911. The dam never produced electricity, again.

One little problem with the dam was that it proved to be an obstacle for migrating salmon. Fish ladders helped solve that problem for several years. The wooden ladders fell into disrepair and the salmon started to disappear from their spawning grounds. Fish and Game repaired the ladders at least once, but in 1933 the agency tired of the upkeep and decided to blow the dam up.

The dam belonged to someone, though, and dreams of mining riches die hard. Owners talked of using electricity from the dam again in “future” mining operations. They brought suit against the state to stop the destruction of the dam.

The mining company and the state settled out of court, with both parties agreeing to share costs in opening the dam up for migrating salmon. Fish passage was assured in 1934 by the careful application of dynamite.

Today, Sunbeam Dam is a tombstone to itself, a concrete reminder of a failed mining operation.

A new power source was needed because the area had been logged out partly to supply fuel for a steam-powered mill. Without logs, that mill couldn’t run. Without the mill to process raw ore, there was no point mining.

Sunbeam Dam to the rescue. It took 300 tons of concrete to build the dam, which was 95 feet wide and 35 feet high. The dam produced cheap electricity for the mine for a year. But the low grade of the ore coming out of Jordan Creek couldn’t make the operation pay, no matter how cheap the electricity was.

The dam, and other mining properties, were sold at a sheriff’s auction in 1911. The dam never produced electricity, again.

One little problem with the dam was that it proved to be an obstacle for migrating salmon. Fish ladders helped solve that problem for several years. The wooden ladders fell into disrepair and the salmon started to disappear from their spawning grounds. Fish and Game repaired the ladders at least once, but in 1933 the agency tired of the upkeep and decided to blow the dam up.

The dam belonged to someone, though, and dreams of mining riches die hard. Owners talked of using electricity from the dam again in “future” mining operations. They brought suit against the state to stop the destruction of the dam.

The mining company and the state settled out of court, with both parties agreeing to share costs in opening the dam up for migrating salmon. Fish passage was assured in 1934 by the careful application of dynamite.

Today, Sunbeam Dam is a tombstone to itself, a concrete reminder of a failed mining operation.

Published on August 21, 2020 04:00

August 20, 2020

Moving Panoramas

What did we do before the Internet for entertainment? Oh yeah, TV. Oh, and movies, and before that, moving panoramas, and before… Wait, moving panoramas?

The term “moving panorama” has often been used as a metaphor, as in “the street scene was a moving panorama,” or “the moving panorama of life.”

What is lost to most of us is that moving panoramas were a common form of entertainment in the 19th century. Picture (as in the picture) a continuous canvas scene with each end rolled around large spools. Cranking and rolling one spool would scroll the painting past an audience. The paintings themselves were usually not the whole show. There would be a narrator and perhaps music to go along with the narration. Often the story would be essentially a road trip or travelogue describing what the narrator saw on his adventure.

The first reference to one I found in an Idaho paper was the mention of Pendar’s Panorama of the War in the Nov. 21, 1863 edition of the Boise News, which was a short-lived Idaho City newspaper.

In 1865 the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman noted that “A Panorama of the civil war in America, ancient scenes of the Bible, and a large number of miscellaneous and running comic views, will be exhibited in this city to-night in the canvas spread on the corner opposite the Statesman office. In connection with it is a sword-swallower, stone-eater and snake charmer.”

Artemus Ward, arguably the first ever stand-up comic, travelled the world with a panorama that was a parody of panoramas.

The Idaho County Free Press in Grangeville trumpeted a panorama on September 11, 1891. “There will be a magic lantern exhibition at Grange hall, Tuesday evening September 22, showing views of Gettysburg, historic places of America, the Johnstown disaster, views along the vine-clad Rhine, Irish scenery, an ocean steamer at sea, etc, etc. There will also be recitations of famous poems, and an interesting lecture to accompany the panorama.”

A competing form of entertainment, and another presage of motion pictures, was the viewing of projected stereoscopic photos. An article or ad—it was sometimes difficult to tell the difference—in the Idaho City World of October 13, 1866, touted the superiority of this new amusement over moving panoramas with a series of stacked headlines:

New Exhibition

OF THE

STEREOSCOPTICON

And California and Nevada Scenary

Produced by the wonderful and celebrated

MAGNESIUM LIGHTS

Will exhibit at the

JENNY LIND THEATER, IDAHO CITY

The term “moving panorama” has often been used as a metaphor, as in “the street scene was a moving panorama,” or “the moving panorama of life.”

What is lost to most of us is that moving panoramas were a common form of entertainment in the 19th century. Picture (as in the picture) a continuous canvas scene with each end rolled around large spools. Cranking and rolling one spool would scroll the painting past an audience. The paintings themselves were usually not the whole show. There would be a narrator and perhaps music to go along with the narration. Often the story would be essentially a road trip or travelogue describing what the narrator saw on his adventure.

The first reference to one I found in an Idaho paper was the mention of Pendar’s Panorama of the War in the Nov. 21, 1863 edition of the Boise News, which was a short-lived Idaho City newspaper.

In 1865 the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman noted that “A Panorama of the civil war in America, ancient scenes of the Bible, and a large number of miscellaneous and running comic views, will be exhibited in this city to-night in the canvas spread on the corner opposite the Statesman office. In connection with it is a sword-swallower, stone-eater and snake charmer.”

Artemus Ward, arguably the first ever stand-up comic, travelled the world with a panorama that was a parody of panoramas.

The Idaho County Free Press in Grangeville trumpeted a panorama on September 11, 1891. “There will be a magic lantern exhibition at Grange hall, Tuesday evening September 22, showing views of Gettysburg, historic places of America, the Johnstown disaster, views along the vine-clad Rhine, Irish scenery, an ocean steamer at sea, etc, etc. There will also be recitations of famous poems, and an interesting lecture to accompany the panorama.”

A competing form of entertainment, and another presage of motion pictures, was the viewing of projected stereoscopic photos. An article or ad—it was sometimes difficult to tell the difference—in the Idaho City World of October 13, 1866, touted the superiority of this new amusement over moving panoramas with a series of stacked headlines:

New Exhibition

OF THE

STEREOSCOPTICON

And California and Nevada Scenary

Produced by the wonderful and celebrated

MAGNESIUM LIGHTS

Will exhibit at the

JENNY LIND THEATER, IDAHO CITY

Published on August 20, 2020 04:00