Rick Just's Blog, page 148

October 8, 2020

An Early Everything Store

In the 1860s it wasn’t wise to carry around a lot of money or gold in Idaho Territory. There was always someone ready to relieve you of it and, perhaps, your life if you hesitated to turn over your wealth.

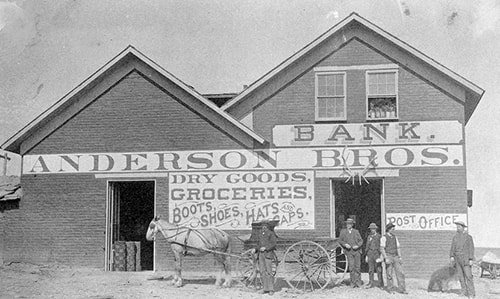

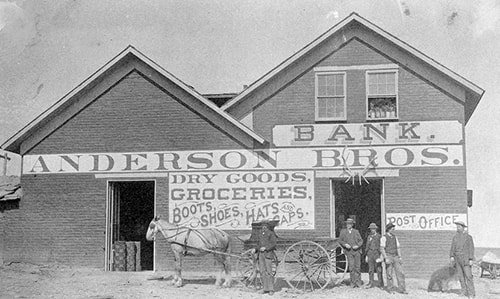

Travelers between Corrine or Kelton, Utah, and Virginia City, Montana began asking the proprietors at the Anderson Brothers store at Taylor Bridge to hold their m oney for them, keeping it safe until they would return. Taylor Bridge was a toll bridge at what was first called Taylor Bridge, then Eagle Rock as it became a town, and Idaho Falls when it became a city. The Anderson Brothers store was one of the first to serve travelers going back and forth between the Montana mines and Utah supply points.

As the only spot for hundreds of square miles that had even a hint of security, Anderson Brothers began keeping goods and wealth as a favor to miners, often with no receipt except a handshake. The miners would drop back by in person when they were ready to claim their possessions, or they’d send a note by mail to the Anderson Brothers store requesting they send it on to another destination.

The Anderson Brothers began to worry about having money and gold sitting around on shelves beneath the counter, so they ordered a safe. That safe, and its continued use inspired them to open Anderson Brothers Bank.

The store became an unofficial post office the same way it became an unofficial bank, by being a place where people stopped on their way to someplace else.

The post office came about because people would leave letters in a box, hoping someone going more or less in the direction the letter was headed would pick it up and take it a few miles closer. People just pawed through the mail looking for a letter for them, or finding a letter for someone else that they could move on down the road a bit.

If that sounds like a haphazard way to run a post office, it sounded the same way to a postal inspector that happened through on his way to Montana. When he pointed this out to the Anderson Brothers, according to an article in the August 26, 1932 edition of the Post Register, one of them kicked the box of letters out the door and said, “There is your post office. Take it with you, and if you don’t like the way we do things around here we will throw you after the box.”

The inspector had a change of heart and decided they could continue their unauthorized post office, which they did until an official one was established a few years later when the railroad arrived.

Travelers between Corrine or Kelton, Utah, and Virginia City, Montana began asking the proprietors at the Anderson Brothers store at Taylor Bridge to hold their m oney for them, keeping it safe until they would return. Taylor Bridge was a toll bridge at what was first called Taylor Bridge, then Eagle Rock as it became a town, and Idaho Falls when it became a city. The Anderson Brothers store was one of the first to serve travelers going back and forth between the Montana mines and Utah supply points.

As the only spot for hundreds of square miles that had even a hint of security, Anderson Brothers began keeping goods and wealth as a favor to miners, often with no receipt except a handshake. The miners would drop back by in person when they were ready to claim their possessions, or they’d send a note by mail to the Anderson Brothers store requesting they send it on to another destination.

The Anderson Brothers began to worry about having money and gold sitting around on shelves beneath the counter, so they ordered a safe. That safe, and its continued use inspired them to open Anderson Brothers Bank.

The store became an unofficial post office the same way it became an unofficial bank, by being a place where people stopped on their way to someplace else.

The post office came about because people would leave letters in a box, hoping someone going more or less in the direction the letter was headed would pick it up and take it a few miles closer. People just pawed through the mail looking for a letter for them, or finding a letter for someone else that they could move on down the road a bit.

If that sounds like a haphazard way to run a post office, it sounded the same way to a postal inspector that happened through on his way to Montana. When he pointed this out to the Anderson Brothers, according to an article in the August 26, 1932 edition of the Post Register, one of them kicked the box of letters out the door and said, “There is your post office. Take it with you, and if you don’t like the way we do things around here we will throw you after the box.”

The inspector had a change of heart and decided they could continue their unauthorized post office, which they did until an official one was established a few years later when the railroad arrived.

Published on October 08, 2020 04:00

October 7, 2020

A Remarkable Chief

Back before there was an Idaho, or a Wyoming, or pick your state, there was a Shoshoni land that stretched irregularly from Death Valley north to where Salmon is today, and east into the Wind River Range. It encompassed much of southern Idaho and northern Utah.

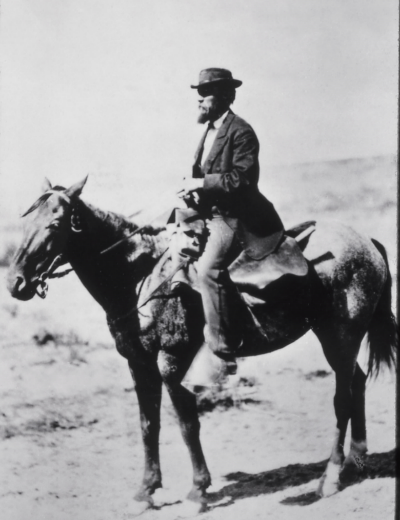

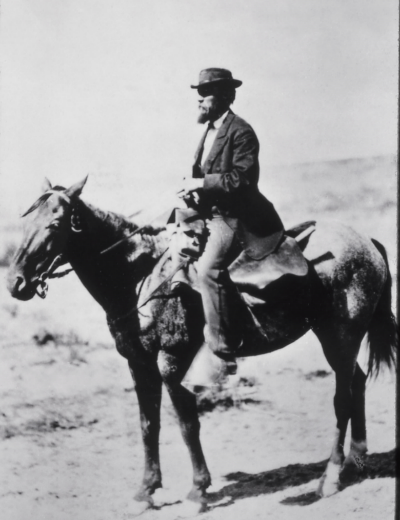

It was into this vast territory that a boy was born, known then as Pinaquanah and today as Washakie. He would become a leader of the Shoshone people and would be richly honored. He may have met his first white men in 1811 along the Boise River when Wilson Hunt’s party was on its way through to Astoria. When he was 16 he met Jim Bridger. They were friends for many years and Bridger married one of Washakie’s daughters in 1850.

Washakie became the chief of the Eastern Snakes in the late 1800s. His people were friendly with fur traders and later soldiers. He and his warriors helped General George Crook defeat the Sioux following Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn.

Chief Washakie, and other tribal chiefs, signed the Fort Bridger treaties of 1863 and 1868, establishing large reservations for the Shoshone people. The Eastern Shoshones, Washakie’s band, initially received more than three million acres in the Wind River Country. In most such treaties between the U.S. and Indian tribes, the tribes saw their lands dramatically reduced in size. Today the Wind River Reservation is about 2.2 million acres.

Washakie loved gambling and was a renowned artist, using hides as the medium on which he painted. He was interested in religion and became first an Episcopalian, then later in his life, as he became friends with Brigham Young, a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He believed deeply in education. Today’s Chief Washakie Foundation carries on his tradition of educating his people with his great-great grandson as its head.

Chief Washakie was honored in many ways. In 1878 Fort Washakie, in Wyoming, became the first—and to date—only U.S. military outpost to be named after a Native American. Wyoming’s Washakie County is named for him. Washakie, Utah, now a ghost town, carries his name. The dining hall at the University of Wyoming is Washakie Hall. There’s a statue of the man in downtown Casper. More importantly, Chief Washakie is depicted in a bronze sculpture in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol building. Two ships have carried his name, the Liberty Ship SS Chief Washakie commissioned during World War II, and the USS Washakie, a U.S. Navy harbor tug. When he died in 1900 he was given a full military funeral.

It was into this vast territory that a boy was born, known then as Pinaquanah and today as Washakie. He would become a leader of the Shoshone people and would be richly honored. He may have met his first white men in 1811 along the Boise River when Wilson Hunt’s party was on its way through to Astoria. When he was 16 he met Jim Bridger. They were friends for many years and Bridger married one of Washakie’s daughters in 1850.

Washakie became the chief of the Eastern Snakes in the late 1800s. His people were friendly with fur traders and later soldiers. He and his warriors helped General George Crook defeat the Sioux following Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn.

Chief Washakie, and other tribal chiefs, signed the Fort Bridger treaties of 1863 and 1868, establishing large reservations for the Shoshone people. The Eastern Shoshones, Washakie’s band, initially received more than three million acres in the Wind River Country. In most such treaties between the U.S. and Indian tribes, the tribes saw their lands dramatically reduced in size. Today the Wind River Reservation is about 2.2 million acres.

Washakie loved gambling and was a renowned artist, using hides as the medium on which he painted. He was interested in religion and became first an Episcopalian, then later in his life, as he became friends with Brigham Young, a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He believed deeply in education. Today’s Chief Washakie Foundation carries on his tradition of educating his people with his great-great grandson as its head.

Chief Washakie was honored in many ways. In 1878 Fort Washakie, in Wyoming, became the first—and to date—only U.S. military outpost to be named after a Native American. Wyoming’s Washakie County is named for him. Washakie, Utah, now a ghost town, carries his name. The dining hall at the University of Wyoming is Washakie Hall. There’s a statue of the man in downtown Casper. More importantly, Chief Washakie is depicted in a bronze sculpture in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol building. Two ships have carried his name, the Liberty Ship SS Chief Washakie commissioned during World War II, and the USS Washakie, a U.S. Navy harbor tug. When he died in 1900 he was given a full military funeral.

Published on October 07, 2020 04:00

October 6, 2020

A Boise Tunnel that isn't a Myth

Burying the story of Chinese tunnels in Boise for a moment, let’s take a look at a tunnel that indisputably exists. It’s the Capitol Mall Tunnel that runs more or less beneath State Street for a couple of blocks near the Idaho statehouse.

Digging the tunnel cost about $280,000 in 1977. It was created to provide underground access to state office buildings for use by state employees and legislators. The tunnel was originally designed to connect the Hall of Mirrors building (formally named the Joe R. Williams Building), the Len B Jordan Office Building, the Capitol Mall parking garage, the Pete T. Cenarrusa Building, and the statehouse. Today it also connects to the Idaho Supreme Court building and lessor known entities such as a credit union, a cafeteria, the state mail offices, and utilities.

The concrete tunnel, about 350 yards at its longest stretch, will not likely become a tourist attraction anytime soon. Although the smooth floor would thrill skateboarders, it isn’t open to the public. Access is available only to those who have key cards. Even so, there was an effort to cheer up the dreary gray walls in the 1980s. High school students were allowed to paint murals on the concrete walls. They are mildly interesting, but those walking through the tunnel might well wish for a midnight assault by spray paint from Banksy.

A mural of the word Agriculture with each letter filled with individual ag paintings was completed in February 2020 by Parma High School art teacher Linda McMillin. Unlike most of the earlier murals this one has a very professional look to it. That’s not a dig at the high school art student murals. They have a simple charm that captures a moment in time for the students who painted them.

Here are a few samples of the paintings in the tunnel.

Digging the tunnel cost about $280,000 in 1977. It was created to provide underground access to state office buildings for use by state employees and legislators. The tunnel was originally designed to connect the Hall of Mirrors building (formally named the Joe R. Williams Building), the Len B Jordan Office Building, the Capitol Mall parking garage, the Pete T. Cenarrusa Building, and the statehouse. Today it also connects to the Idaho Supreme Court building and lessor known entities such as a credit union, a cafeteria, the state mail offices, and utilities.

The concrete tunnel, about 350 yards at its longest stretch, will not likely become a tourist attraction anytime soon. Although the smooth floor would thrill skateboarders, it isn’t open to the public. Access is available only to those who have key cards. Even so, there was an effort to cheer up the dreary gray walls in the 1980s. High school students were allowed to paint murals on the concrete walls. They are mildly interesting, but those walking through the tunnel might well wish for a midnight assault by spray paint from Banksy.

A mural of the word Agriculture with each letter filled with individual ag paintings was completed in February 2020 by Parma High School art teacher Linda McMillin. Unlike most of the earlier murals this one has a very professional look to it. That’s not a dig at the high school art student murals. They have a simple charm that captures a moment in time for the students who painted them.

Here are a few samples of the paintings in the tunnel.

Published on October 06, 2020 04:00

October 5, 2020

Protesting is not a New Thing

If you’ve been reading these history posts for a while, you know that I’m interested in how things got their names. I’ve done posts on how the state got its name, where county names came from, and why cities in Idaho have their names. I’m even a proud member pf the Idaho Geographic Names Advisory Committee.

So, you would not be surprised that the name Protest Road in Boise has always intrigued me. What protest was it commemorating? Women’s suffrage, perhaps? Something to do with a labor strike from back in the Wobbly days? Maybe it came from the civil rights struggle.

As it turns out, Protest Road is named such because of a protest. Over a road. That road.

In March of 1950 stakes were going up in South Boise for a new road that would connect the area to a new fire station being built on the rim above. That wasn’t a surprise. Residents had voted to construct such a road. But in the mind of a citizen protest committee, the stakes indicated the road was being planned in the wrong place. The road as staked out would send fire engines to Boise Avenue, where they would have to reverse their direction and come back into South Boise along a narrow and twisting thoroughfare. They had voted on a route that would allow engines to access South Boise more directly.

More than 500 citizens showed up in early community meetings on the matter. They voted to form the South Boise Citizens Protest Committee. Ultimately a sensible alignment of the road was proposed that seemed to work for everyone. It was decided that the road should be called Protest Road in commemoration of the efforts of the Committee.

This wasn’t the first time a citizen protest committee from South Boise had been formed. I found an article from 1907 in the Statesman headlined “Citizens of South Boise to Hold an Indignation Meeting Next Tuesday Night.” That “indignation” was also over a transportation issue, poor rail service to the area.

It’s not surprising that residents take their transportation issues seriously in South Boise. Transportation was there before there was a South Boise. The Oregon Trail runs through that section of town.

Thanks to Barbara Perry Bauer for her help with research on this post and for her delightful little book South Boise Scrapbook.

So, you would not be surprised that the name Protest Road in Boise has always intrigued me. What protest was it commemorating? Women’s suffrage, perhaps? Something to do with a labor strike from back in the Wobbly days? Maybe it came from the civil rights struggle.

As it turns out, Protest Road is named such because of a protest. Over a road. That road.

In March of 1950 stakes were going up in South Boise for a new road that would connect the area to a new fire station being built on the rim above. That wasn’t a surprise. Residents had voted to construct such a road. But in the mind of a citizen protest committee, the stakes indicated the road was being planned in the wrong place. The road as staked out would send fire engines to Boise Avenue, where they would have to reverse their direction and come back into South Boise along a narrow and twisting thoroughfare. They had voted on a route that would allow engines to access South Boise more directly.

More than 500 citizens showed up in early community meetings on the matter. They voted to form the South Boise Citizens Protest Committee. Ultimately a sensible alignment of the road was proposed that seemed to work for everyone. It was decided that the road should be called Protest Road in commemoration of the efforts of the Committee.

This wasn’t the first time a citizen protest committee from South Boise had been formed. I found an article from 1907 in the Statesman headlined “Citizens of South Boise to Hold an Indignation Meeting Next Tuesday Night.” That “indignation” was also over a transportation issue, poor rail service to the area.

It’s not surprising that residents take their transportation issues seriously in South Boise. Transportation was there before there was a South Boise. The Oregon Trail runs through that section of town.

Thanks to Barbara Perry Bauer for her help with research on this post and for her delightful little book South Boise Scrapbook.

Published on October 05, 2020 04:00

October 4, 2020

Lake, Ditch, Whatever

Sometimes place names are a little deceptive, and deliberately so.

The town of Cascade was founded in 1912, consolidating the communities of Van Wyck, Thunder City, and Crawford, according to Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. The town was named for nearby Cascade Falls. Cascade Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1948, creating Cascade Reservoir and effectively drowning the falls the reservoir was named for.

Cascade Reservoir hosted boaters and anglers for more than 50 years until 1999, when Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade. So, we have a lake that isn’t a lake named for a waterfall which the (not) lake destroyed.

I get it. I’m not complaining about the dam or the reservoir, only noting the irony that can sometimes come about when naming something.

Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade because local tourism promoters thought it sounded better. They were right. Lake Cascade sounds like something nature created and is thus more enticing than what we may picture in our minds when we think of a reservoir.

Another example of this bait and switch is Logger Creek in Boise. Logger Creek sounds much more scenic than Logger Ditch. Ditch it is, though. It was created in 1865 to power a waterwheel flour mill, which later became a sawmill. The ditch was then used to float logs to the mill. Much of Logger Creek was filled in years later, but the remaining section, which pulls water from the Boise River now does little else but take that water for a scenic ride along the Greenbelt before diverting it back into the river.

The town of Cascade was founded in 1912, consolidating the communities of Van Wyck, Thunder City, and Crawford, according to Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. The town was named for nearby Cascade Falls. Cascade Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1948, creating Cascade Reservoir and effectively drowning the falls the reservoir was named for.

Cascade Reservoir hosted boaters and anglers for more than 50 years until 1999, when Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade. So, we have a lake that isn’t a lake named for a waterfall which the (not) lake destroyed.

I get it. I’m not complaining about the dam or the reservoir, only noting the irony that can sometimes come about when naming something.

Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade because local tourism promoters thought it sounded better. They were right. Lake Cascade sounds like something nature created and is thus more enticing than what we may picture in our minds when we think of a reservoir.

Another example of this bait and switch is Logger Creek in Boise. Logger Creek sounds much more scenic than Logger Ditch. Ditch it is, though. It was created in 1865 to power a waterwheel flour mill, which later became a sawmill. The ditch was then used to float logs to the mill. Much of Logger Creek was filled in years later, but the remaining section, which pulls water from the Boise River now does little else but take that water for a scenic ride along the Greenbelt before diverting it back into the river.

Published on October 04, 2020 04:00

October 3, 2020

Simplot Chips In

J.R. Simplot was not born in Idaho. He was born in—wait for it—Iowa, thus further confusing those who can’t tell the two states apart.

Simplot didn’t stay in Iowa long. His parents brought him and his six siblings to a little farm near Declo, Idaho when he was about a year old. One could say he left a bit of a mark on the state’s business history.

J.R. made his first money from feeding pigs, and then kept making it. And making it. He lived in a time when it wasn’t unusual to quit school after completing the eighth grade, which was what he did. Most dropouts didn’t go on to become the largest shipper of fresh potatoes in the nation, or become a phosphate king, which he also did. The story of how his company developed a method of freezing French fried potatoes, and how he did a handshake deal with Ray Kroc to supply fries to McDonalds is well known.

J.R. liked to say that he was big in chips. He meant potato chips, but he also meant computer chips. He was key in the early days of computer chip maker Micron Technology. Simplot gave the Parkinson brothers of Blackfoot $1 million in the early days of the company, then put in another $20 million to help Micron build its first fabrication plant in Boise.

J.R. Simplot died in 2008 at age 99. His company recently built a new headquarters building in Boise, and the J.R. Simplot Foundation built something called JUMP next door. That stands for Jack’s Urban Meeting Place. It’s the site of public performances in the arts, various makers studios, giant slippery slides, and a bunch of tractors. That description doesn’t do it justice. None does. You have to see it yourself to understand the vision. It’s worth a visit for the tractors alone. About 50 antique tractors from J.R. Simplot’s personal collection are on display at JUMP in downtown Boise.

The photo of J.R. Simplot with some unidentified kind of tuber is from the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

Simplot didn’t stay in Iowa long. His parents brought him and his six siblings to a little farm near Declo, Idaho when he was about a year old. One could say he left a bit of a mark on the state’s business history.

J.R. made his first money from feeding pigs, and then kept making it. And making it. He lived in a time when it wasn’t unusual to quit school after completing the eighth grade, which was what he did. Most dropouts didn’t go on to become the largest shipper of fresh potatoes in the nation, or become a phosphate king, which he also did. The story of how his company developed a method of freezing French fried potatoes, and how he did a handshake deal with Ray Kroc to supply fries to McDonalds is well known.

J.R. liked to say that he was big in chips. He meant potato chips, but he also meant computer chips. He was key in the early days of computer chip maker Micron Technology. Simplot gave the Parkinson brothers of Blackfoot $1 million in the early days of the company, then put in another $20 million to help Micron build its first fabrication plant in Boise.

J.R. Simplot died in 2008 at age 99. His company recently built a new headquarters building in Boise, and the J.R. Simplot Foundation built something called JUMP next door. That stands for Jack’s Urban Meeting Place. It’s the site of public performances in the arts, various makers studios, giant slippery slides, and a bunch of tractors. That description doesn’t do it justice. None does. You have to see it yourself to understand the vision. It’s worth a visit for the tractors alone. About 50 antique tractors from J.R. Simplot’s personal collection are on display at JUMP in downtown Boise.

The photo of J.R. Simplot with some unidentified kind of tuber is from the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

Published on October 03, 2020 04:00

October 2, 2020

A Legendary Packer

When you were a miner in the early days of Idaho, you couldn’t just order up supplies from Amazon. There were no planes, no trucks, and most importantly, no roads. Everything had to be packed in to remote areas, usually by a string of mules. If you had a big job, you counted on Jesus Urquides to get what you needed where you needed it.

Urquides was born in 1833, perhaps in San Francisco, as many sources claim, or perhaps in Sonora, Mexico, as he once said in a magazine interview. He is often called Boise’s Basque packer, though he was probably Mexican, not Basque.

Urquides started freighting in 1850, taking supplies to the Forty-niners—the miners. The football team of the same name would come along about a hundred years later.

He bragged that there was not a camp of any size between California and Montana that he had not packed supplies to. He packed a lot of whiskey, ammunition for the military, railroad track, and the first mill to the mine at Thunder Mountain. We’re not talking about a couple of mules here. Urquides would have trains of 65 or more.

Probably his most famous packing feat came when he was called on to take a roll of copper wire for a tram to the Yellow Jacket mine outside of Challis. A roll of wire doesn’t seem like much, but it weighed 10,000 pounds. It had to be distributed in coils across 35 mules working three abreast. The tricky thing was that you couldn’t simply cut it and make a couple of tidy rolls for each mule. Cutting the wire, then splicing it back together would make it too dangerous to use on a tram. Urquides’ solution was to wrap each mule in a coil of wire it could handle—maybe up to 300 pounds—then string it on to the next mule, and on and on. Of course, if one mule took a tumble, he’d drag other mules down with him. This happened several times. Each time Urquides and his men would get the mules back on their feet, make sure the wire was okay, then set off again. He only had 70 miles to travel, much of it up and down mountains and through canyons.

Ridiculous as the arrangement seems, Urquides made it work. He delivered the unbroken wire to its destination. He once commented, “I never coveted another job like that.”

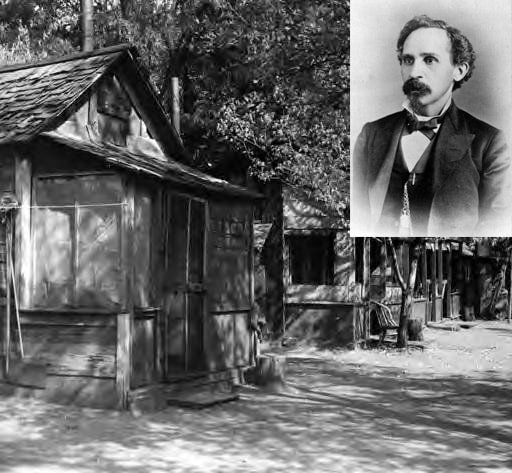

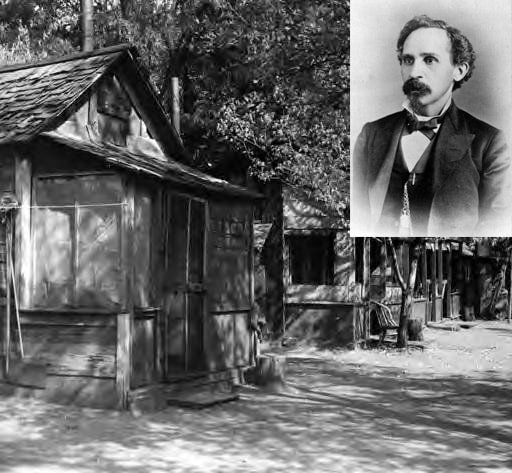

In the late 1870s Urquides built about 30 one-room buildings in Boise behind his home at 115 Main, to house his drivers and wranglers. It became known as “Spanish Village.” This shanty town would last about a hundred years, furnishing low-rent housing long past the days of 65-mule strings.

Jesus Urquides died in 1928 at age 95 and is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, not far from his Boise home. The photo of Spanish Village and Urquides are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Urquides was born in 1833, perhaps in San Francisco, as many sources claim, or perhaps in Sonora, Mexico, as he once said in a magazine interview. He is often called Boise’s Basque packer, though he was probably Mexican, not Basque.

Urquides started freighting in 1850, taking supplies to the Forty-niners—the miners. The football team of the same name would come along about a hundred years later.

He bragged that there was not a camp of any size between California and Montana that he had not packed supplies to. He packed a lot of whiskey, ammunition for the military, railroad track, and the first mill to the mine at Thunder Mountain. We’re not talking about a couple of mules here. Urquides would have trains of 65 or more.

Probably his most famous packing feat came when he was called on to take a roll of copper wire for a tram to the Yellow Jacket mine outside of Challis. A roll of wire doesn’t seem like much, but it weighed 10,000 pounds. It had to be distributed in coils across 35 mules working three abreast. The tricky thing was that you couldn’t simply cut it and make a couple of tidy rolls for each mule. Cutting the wire, then splicing it back together would make it too dangerous to use on a tram. Urquides’ solution was to wrap each mule in a coil of wire it could handle—maybe up to 300 pounds—then string it on to the next mule, and on and on. Of course, if one mule took a tumble, he’d drag other mules down with him. This happened several times. Each time Urquides and his men would get the mules back on their feet, make sure the wire was okay, then set off again. He only had 70 miles to travel, much of it up and down mountains and through canyons.

Ridiculous as the arrangement seems, Urquides made it work. He delivered the unbroken wire to its destination. He once commented, “I never coveted another job like that.”

In the late 1870s Urquides built about 30 one-room buildings in Boise behind his home at 115 Main, to house his drivers and wranglers. It became known as “Spanish Village.” This shanty town would last about a hundred years, furnishing low-rent housing long past the days of 65-mule strings.

Jesus Urquides died in 1928 at age 95 and is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, not far from his Boise home. The photo of Spanish Village and Urquides are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on October 02, 2020 04:00

October 1, 2020

Hayden This and That

A reader asked where the name Hayden came from for Hayden Creek in North Idaho. It seemed like a simple request, and I found the answer quickly in Lalia Boone’s definitive Idaho Place Names. Probably. Her explanation for the name Hayden Creek referred to a creek in Lemhi County, not the one that flows into Hayden Lake. That Hayden Creek flows from Hayden Basin. The basin and creek were named for Jim Hayden who was an early packer and freighter in the area. Hayden’s claim to fame was peppered with gunfire. Bill Smith, who was one of the first to discover gold in Leesburg, was playing cards with Jim Hayden in 1871. There was a dispute about a hand. Smith took umbrage at Hayden and fired at the man. Hayden was said to be unarmed, but he found a gun somewhere and shot back, killing Smith. Hayden was acquitted when he went to trial. His relief at that was short-lived. Hayden was killed by Indians in Birch Creek Valley in 1877.

The Hayden creek our reader asked about flows into Hayden Lake in Kootenai County and is not mentioned in Boones book. The lake and town are named after Matt Heyden (sic), soit follows that the creek probably also carries his name. Heyden was reportedly (wait for it…) playing cards with John Hager at Hager’s cabin. There was no gunplay involved with this one. The two men agreed to name the lake after the winner of a seven-up game. Heyden won. Why the name is spelled differently is not explained in Boone’s book, but the U.S. Postal Service was frequently the culprit, having a reputation at that time for little attention to detail.

But wait! There’s more! We can’t forget Hayden Peak in Owyhee County. It was named after Everett Hayden, a surveyor working for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s. Reportedly there was some local grumbling at the time because Hayden had never even been near the peak.

And, maybe there should be something else named Hayden in Idaho after a man the state has so far not honored. It was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (photo) who lead the famous Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871, which passed through Fort Hall on its way to what would become our nation’s first national park. The expedition named a lot of things, including Higham Peak in Bannock County, but nothing in Idaho bears the name of its leader.

The Hayden creek our reader asked about flows into Hayden Lake in Kootenai County and is not mentioned in Boones book. The lake and town are named after Matt Heyden (sic), soit follows that the creek probably also carries his name. Heyden was reportedly (wait for it…) playing cards with John Hager at Hager’s cabin. There was no gunplay involved with this one. The two men agreed to name the lake after the winner of a seven-up game. Heyden won. Why the name is spelled differently is not explained in Boone’s book, but the U.S. Postal Service was frequently the culprit, having a reputation at that time for little attention to detail.

But wait! There’s more! We can’t forget Hayden Peak in Owyhee County. It was named after Everett Hayden, a surveyor working for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s. Reportedly there was some local grumbling at the time because Hayden had never even been near the peak.

And, maybe there should be something else named Hayden in Idaho after a man the state has so far not honored. It was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (photo) who lead the famous Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871, which passed through Fort Hall on its way to what would become our nation’s first national park. The expedition named a lot of things, including Higham Peak in Bannock County, but nothing in Idaho bears the name of its leader.

Published on October 01, 2020 04:00

September 30, 2020

Pop Quiz!

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). What did Mrs. Fred T. Dubois give to President Taft when he visited Idaho?

A. A corsage.

B. A kiss on both cheeks.

C. A pig.

D. A basket of potatoes.

E. A bicycle.

2). Why is Henry C. Riggs remembered in Idaho history?

A. He introduced quail to the state.

B. He claimed to be the first resident of Boise.

C. He brought the first newspaper to Boise.

D. He introduced the bill in the Territorial Legislature to make Boise the capital.

E. All of the above.

3). How far did the two young men on a tandem bicycle get from Boise in 1911?

A. Mountain Home.

B. Buffalo, New York.

C. Wyoming.

D. St. Louis, Missouri.

E. Denver, Colorado.

4). What is the problem with “Old 97,” the cannon on the Idaho State Capitol grounds?

A. Although it was called “Old 97” the barrel is actually stamped “79.”.

B. It has never been fired because of a crack in the barrel.

C. Although purportedly a civil war cannon, it was manufactured in 1897.

D. It’s a copy of the original which was melted down for scrap during WWII.

E. No one has ever called it “Old 97.”

5) Why was Taylor Williams nicknamed “Bear Track”?

A. He was a hunting guide who specialized in tracking bears.

B. He once misidentified a melted otter track as being a black bear track.

C. He lost some toes in a grizzly bear attack.

D. As a kid he was convinced that every animal track he saw belonged to a bear.

E. He walked with his toes pointed out.

Answers

1, C

2, E

3, C

4, A

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). What did Mrs. Fred T. Dubois give to President Taft when he visited Idaho?

A. A corsage.

B. A kiss on both cheeks.

C. A pig.

D. A basket of potatoes.

E. A bicycle.

2). Why is Henry C. Riggs remembered in Idaho history?

A. He introduced quail to the state.

B. He claimed to be the first resident of Boise.

C. He brought the first newspaper to Boise.

D. He introduced the bill in the Territorial Legislature to make Boise the capital.

E. All of the above.

3). How far did the two young men on a tandem bicycle get from Boise in 1911?

A. Mountain Home.

B. Buffalo, New York.

C. Wyoming.

D. St. Louis, Missouri.

E. Denver, Colorado.

4). What is the problem with “Old 97,” the cannon on the Idaho State Capitol grounds?

A. Although it was called “Old 97” the barrel is actually stamped “79.”.

B. It has never been fired because of a crack in the barrel.

C. Although purportedly a civil war cannon, it was manufactured in 1897.

D. It’s a copy of the original which was melted down for scrap during WWII.

E. No one has ever called it “Old 97.”

5) Why was Taylor Williams nicknamed “Bear Track”?

A. He was a hunting guide who specialized in tracking bears.

B. He once misidentified a melted otter track as being a black bear track.

C. He lost some toes in a grizzly bear attack.

D. As a kid he was convinced that every animal track he saw belonged to a bear.

E. He walked with his toes pointed out.

Answers

1, C

2, E

3, C

4, A

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on September 30, 2020 04:00

September 29, 2020

A Salacious Tale

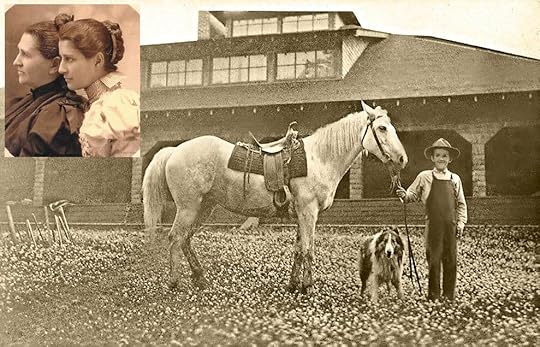

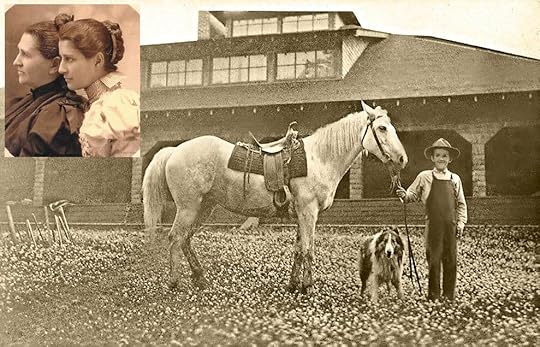

One step over from history is persistent, salacious rumor. Such is the story of Frieda Bethmann, one-time resident of Pardee, Idaho.

A 1990 story in the Lewiston Tribune by Diane Pettit, which is easily found on the web, recounts the persistent rumors about Frieda and her son Miner. Frieda was the daughter of Francis Alfred Ferdinand Bethmann and Emile Bethmann. Her father was in the sugar importing business and her mother was active in the kindergarten movement.

The Bethmanns were friends with President Grover Cleveland. That Frieda turned up with a “nephew” named Miner who was almost certainly her son started the rumors rumbling. Cleveland admitted to fathering one illegitimate child in his bachelor days. Perhaps there was a second.

About 1908 after the death of her father, Frieda and her mother moved to a grand house overlooking the Clearwater River. Rumors had Pres. Cleveland building the house for his “mistress.” In fact, the house was built by Frieda’s mother. She purchased the land and oversaw its construction herself.

But it was Frieda everyone was interested in. Rumor had it that she had served as Cleveland’s appointment secretary, no doubt with emphasis on the “appointment.” In fact, she had served briefly as a kindergarten instructor to the Cleveland children.

The rumors had Cleveland making several visits to Idaho by rail. No photo or newspaper account seems to exist that would prove that. Cleveland allegedly signed the guest register at a Pomeroy, Washington hotel, but even that tenuous clue seems suspect as the signature looks nothing like Cleveland’s signature.

Miner Bethmann had reporters showing up on his doorstep from time to time throughout his life. He is said to have driven them off without comment.

The rumors persist and, yes, this retelling will only help keep them alive. We will probably never know who Miner’s father was. We do know that certain parts of the speculation, such as who built the house, are incorrect. Rumors about Cleveland visiting Frieda in Pardee seem not to add up. The Bethmanns moved there in 1908, the year Grover Cleveland died at age 71.

Pres. Cleveland may not have fathered a boy who grew up in Idaho, but he did do one thing that helped shape the state. In 1887 there was a movement in Congress to split off the northern part of Idaho Territory and attach it to Washington. The bill landed on President Cleveland’s desk, where it died as a pocket veto.

Thanks to Dick Southern for supplying much information on the Bethmanns in his exhaustive local book on Pardee, Idaho history They Called This Canyon “Home.”

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

A 1990 story in the Lewiston Tribune by Diane Pettit, which is easily found on the web, recounts the persistent rumors about Frieda and her son Miner. Frieda was the daughter of Francis Alfred Ferdinand Bethmann and Emile Bethmann. Her father was in the sugar importing business and her mother was active in the kindergarten movement.

The Bethmanns were friends with President Grover Cleveland. That Frieda turned up with a “nephew” named Miner who was almost certainly her son started the rumors rumbling. Cleveland admitted to fathering one illegitimate child in his bachelor days. Perhaps there was a second.

About 1908 after the death of her father, Frieda and her mother moved to a grand house overlooking the Clearwater River. Rumors had Pres. Cleveland building the house for his “mistress.” In fact, the house was built by Frieda’s mother. She purchased the land and oversaw its construction herself.

But it was Frieda everyone was interested in. Rumor had it that she had served as Cleveland’s appointment secretary, no doubt with emphasis on the “appointment.” In fact, she had served briefly as a kindergarten instructor to the Cleveland children.

The rumors had Cleveland making several visits to Idaho by rail. No photo or newspaper account seems to exist that would prove that. Cleveland allegedly signed the guest register at a Pomeroy, Washington hotel, but even that tenuous clue seems suspect as the signature looks nothing like Cleveland’s signature.

Miner Bethmann had reporters showing up on his doorstep from time to time throughout his life. He is said to have driven them off without comment.

The rumors persist and, yes, this retelling will only help keep them alive. We will probably never know who Miner’s father was. We do know that certain parts of the speculation, such as who built the house, are incorrect. Rumors about Cleveland visiting Frieda in Pardee seem not to add up. The Bethmanns moved there in 1908, the year Grover Cleveland died at age 71.

Pres. Cleveland may not have fathered a boy who grew up in Idaho, but he did do one thing that helped shape the state. In 1887 there was a movement in Congress to split off the northern part of Idaho Territory and attach it to Washington. The bill landed on President Cleveland’s desk, where it died as a pocket veto.

Thanks to Dick Southern for supplying much information on the Bethmanns in his exhaustive local book on Pardee, Idaho history They Called This Canyon “Home.”

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

Published on September 29, 2020 04:00