Rick Just's Blog, page 147

October 20, 2020

Our State Shark

Why don’t we have a state shark? Just asking. We have a state amphibian, a state bird, a state fish, a state flower, a state fruit, a state gem, a state horse, a state insect, a state raptor, a state tree, and a state vegetable (any guesses?). But, sadly, no state shark. Now, the picky readers out there will point out that to have a state shark, we’d have to have a shark in the state. Ha! I have you there.

True, it’s a fossil shark, but there’s precedent for that. Idaho has a state fossil, the Hagerman Horse. The shark I’m talking about is Helicoprion, which once swam the oceans over what is now Soda Springs. “Once” was about 250 million years ago.

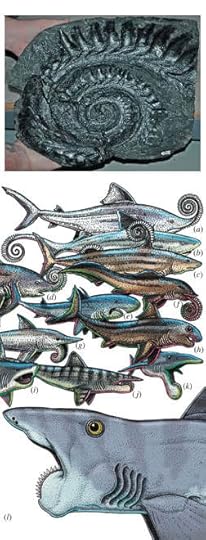

I’ve seen the famous fossils. Every time I’ve looked at them they puzzled me. I’m not alone. They puzzle scientists, too. Sharks don’t fossilize well because their skeletons are made of cartilage. Shark teeth, on the other hand, can hang around for millennia. So it is with the Helicoprion. All we have to prove that it once existed are teeth. But those teeth are so weird. They make up a spiral with small teeth in the center growing geometrically until those on the outer edge become large (picture, top).

With just those buzz-saw teeth to work from, scientists have speculated for years on what the shark would have looked like. Were the teeth in the front of its mouth? In the back? Were they down its throat somehow?

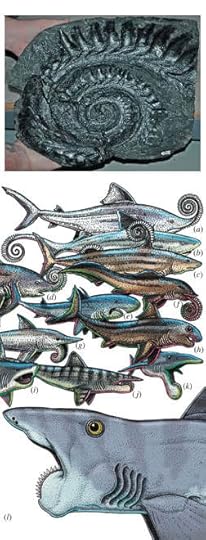

In 2013 an international team of paleontologists, including Professor Leif Tapanila of the Idaho Museum of Natural History and Idaho State University published a paper about the shark in the journal Biology Letters, describing a rare fossil specimen that contained enough cartilage to give scientists a better idea of the creature’s jaw configuration. The image, from that publication, shows several previous depictions above the larger version that their findings describe.

Cute, huh? Even if you’d pass on the state shark idea, think of the mascot possibilities! Soda Springs Cardinals, have you thought of this?

True, it’s a fossil shark, but there’s precedent for that. Idaho has a state fossil, the Hagerman Horse. The shark I’m talking about is Helicoprion, which once swam the oceans over what is now Soda Springs. “Once” was about 250 million years ago.

I’ve seen the famous fossils. Every time I’ve looked at them they puzzled me. I’m not alone. They puzzle scientists, too. Sharks don’t fossilize well because their skeletons are made of cartilage. Shark teeth, on the other hand, can hang around for millennia. So it is with the Helicoprion. All we have to prove that it once existed are teeth. But those teeth are so weird. They make up a spiral with small teeth in the center growing geometrically until those on the outer edge become large (picture, top).

With just those buzz-saw teeth to work from, scientists have speculated for years on what the shark would have looked like. Were the teeth in the front of its mouth? In the back? Were they down its throat somehow?

In 2013 an international team of paleontologists, including Professor Leif Tapanila of the Idaho Museum of Natural History and Idaho State University published a paper about the shark in the journal Biology Letters, describing a rare fossil specimen that contained enough cartilage to give scientists a better idea of the creature’s jaw configuration. The image, from that publication, shows several previous depictions above the larger version that their findings describe.

Cute, huh? Even if you’d pass on the state shark idea, think of the mascot possibilities! Soda Springs Cardinals, have you thought of this?

Published on October 20, 2020 04:00

October 19, 2020

My Private Idaho

We all have our own Idaho. I wrote about that a few years back in my novel,

Keeping Private Idaho

. Today—forgive my indulgence—I’m going to introduce you to mine.

Along about 1956 my father, who we called Pop, noticed that the configuration of ditches near the house on our family ranch outside of Blackfoot made three sides of a rectangle. I still remember him scraping up dirt with a squat little Ford tractor, pushing it up into what would become a dike along that fourth side.

Pop’s father and grandfather had built a major part of the canal system in Eastern Idaho, so he knew a little bit about making water do what he wanted it to. Usually that meant setting canvas dams in ditches and scraping off the high spots so that a field of alfalfa could get water. But while he was tromping around in waders with a shovel, pointing the way for water, he was thinking about his all-time favorite activity: fishing.

When pop diverted the water into what now had dikes on four sides, we saw his vision come to life. He had created a fish pond, about an acre in size. My brothers and I watched as the tankers came from Springfield with loads of rainbow trout, dumping them into the pond, which had quickly acquired moss, and bugs, and frogs.

Pop called his big idea Chick Just’s Trout Ranch. He had orange signs made that he could tack up on fence posts so people could find their way to the ranch. He charged by the pound for fish they caught. No charge if you didn’t catch anything. But they always caught fish. That was his joy. He liked nothing better than to see a kid catch her first trout.

So, paradise for me. I didn’t care much about fishing, but I cared for nothing more than I cared for that pond. It was my world; one which I could pole across in a skiff pretending I was Huck Finn, and swim in trying not to drown. I caught a million tadpoles and watched them turn into frogs, and chased dragonflies that were enemy helicopters.

That pond was the center of my life growing up. It must have occupied 50 years of my childhood. Yet, when I do the math now, I’m stunned by it. Pop died in 1960. We moved into town in 1961. Five years, not 50.

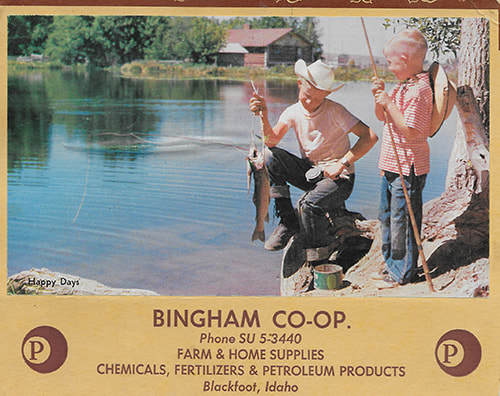

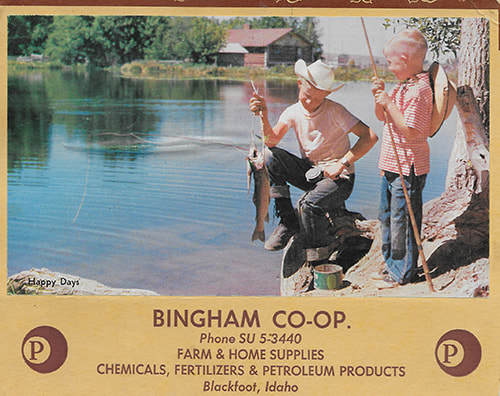

It was so idyllic for a kid you’d think I was making it up. But I have a picture. This one appeared on calendars and in magazines promoting Idaho for three or four years. It’s of me, the cute one, with my older brother, Kent. In the background, you can just make out our log house across the pond. My private Idaho. What does yours look like?

Along about 1956 my father, who we called Pop, noticed that the configuration of ditches near the house on our family ranch outside of Blackfoot made three sides of a rectangle. I still remember him scraping up dirt with a squat little Ford tractor, pushing it up into what would become a dike along that fourth side.

Pop’s father and grandfather had built a major part of the canal system in Eastern Idaho, so he knew a little bit about making water do what he wanted it to. Usually that meant setting canvas dams in ditches and scraping off the high spots so that a field of alfalfa could get water. But while he was tromping around in waders with a shovel, pointing the way for water, he was thinking about his all-time favorite activity: fishing.

When pop diverted the water into what now had dikes on four sides, we saw his vision come to life. He had created a fish pond, about an acre in size. My brothers and I watched as the tankers came from Springfield with loads of rainbow trout, dumping them into the pond, which had quickly acquired moss, and bugs, and frogs.

Pop called his big idea Chick Just’s Trout Ranch. He had orange signs made that he could tack up on fence posts so people could find their way to the ranch. He charged by the pound for fish they caught. No charge if you didn’t catch anything. But they always caught fish. That was his joy. He liked nothing better than to see a kid catch her first trout.

So, paradise for me. I didn’t care much about fishing, but I cared for nothing more than I cared for that pond. It was my world; one which I could pole across in a skiff pretending I was Huck Finn, and swim in trying not to drown. I caught a million tadpoles and watched them turn into frogs, and chased dragonflies that were enemy helicopters.

That pond was the center of my life growing up. It must have occupied 50 years of my childhood. Yet, when I do the math now, I’m stunned by it. Pop died in 1960. We moved into town in 1961. Five years, not 50.

It was so idyllic for a kid you’d think I was making it up. But I have a picture. This one appeared on calendars and in magazines promoting Idaho for three or four years. It’s of me, the cute one, with my older brother, Kent. In the background, you can just make out our log house across the pond. My private Idaho. What does yours look like?

Published on October 19, 2020 04:00

October 18, 2020

A Traveling Newspaper

The Post Register is one of Idaho’s more important newspapers, and one with a long history, tracing its roots back to 1880. The newspaper has published in Idaho Falls for most of that time, but it didn’t start out there. It started in Blackfoot, as the Blackfoot Register.

Blackfoot was the terminus of the railroad in 1880 and probably seemed to publisher Edward Wheeler the better bet for starting a newspaper than Eagle Rock, 25 miles to the north. Eagle Rock would later become Idaho Falls, and by far the larger city, but in 1880 it didn’t amount to much. It had a saloon, a store, and Matt Taylor’s toll bridge. Blackfoot, meanwhile, had a café, hotel, four general stores, four saloons, two blacksmith shops, a wagon shop, a lumber yard, a doctor, and even a jewelry store. It was also, at the time, the most populated city in Idaho Territory. Newspapers run on advertising, so starting one in the comparatively booming City of Blackfoot was the easy choice.

And, make no mistake, advertising was top of mind for Mr. Wheeler. In the first edition of the Blackfoot Register he wrote, “We have… one main object in view, and that is to secure as large an amount of the filthy lucre as possible.”

Wheeler did well enough in Blackfoot for the more than three years he operated there. He plunged into local political issues, championed the building of the city’s first school, and even campaigned to make Blackfoot the territory’s new capital. But lucre moved north and so did the paper.

By 1884 the railroad line had stretched to Eagle Rock and established its headquarters there. Settlers began pouring in. Wheeler pulled up stakes and moved his operation to Eagle Rock where the newspaper began calling itself the Idaho Register.

I’ll write more about the Post Register in later posts, relying as I did for much of this post on William Hathaway’s fascinating book, Images of America, Idaho Falls Post Register , published by Arcadia Publishing.

Blackfoot was the terminus of the railroad in 1880 and probably seemed to publisher Edward Wheeler the better bet for starting a newspaper than Eagle Rock, 25 miles to the north. Eagle Rock would later become Idaho Falls, and by far the larger city, but in 1880 it didn’t amount to much. It had a saloon, a store, and Matt Taylor’s toll bridge. Blackfoot, meanwhile, had a café, hotel, four general stores, four saloons, two blacksmith shops, a wagon shop, a lumber yard, a doctor, and even a jewelry store. It was also, at the time, the most populated city in Idaho Territory. Newspapers run on advertising, so starting one in the comparatively booming City of Blackfoot was the easy choice.

And, make no mistake, advertising was top of mind for Mr. Wheeler. In the first edition of the Blackfoot Register he wrote, “We have… one main object in view, and that is to secure as large an amount of the filthy lucre as possible.”

Wheeler did well enough in Blackfoot for the more than three years he operated there. He plunged into local political issues, championed the building of the city’s first school, and even campaigned to make Blackfoot the territory’s new capital. But lucre moved north and so did the paper.

By 1884 the railroad line had stretched to Eagle Rock and established its headquarters there. Settlers began pouring in. Wheeler pulled up stakes and moved his operation to Eagle Rock where the newspaper began calling itself the Idaho Register.

I’ll write more about the Post Register in later posts, relying as I did for much of this post on William Hathaway’s fascinating book, Images of America, Idaho Falls Post Register , published by Arcadia Publishing.

Published on October 18, 2020 04:00

October 17, 2020

Snowplanes

If the landscape is going to be covered with fluffy, white flakes for several months out of the year, you may as well make the best of it. In Idaho, that meant figuring out a way to travel across snow and ice more easily, or in a way that was more fun.

From the January 11, 1870, Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, “Some of the boys have constructed an iceboat which runs by means of machinery and sails. They had it up on the skating park Sunday, and the time made would astonish a locomotive. It don’t exactly fly but just scoots along fast as the wind. The machine carries four persons and ought to be very popular with the ladies. Tom Maupin has charge of the critter, and will probably turn her loose again this afternoon. “

In the Idaho Daily Statesman of December 29, 1932, there ran a story about a mail carrier in Mountain home who had ordered a “snowmobile” so he could better make the trip from there to Rocky Bar and back.

In January, 1937, The Idaho Daily Statesman had a story about a local man whose “gimmick is a propeller-powered plane fuselage mounted on three skis—two in front in the usual place for landing gear, and the third in the rear at the tail skid.” The article noted that similar devices had been used on the ice on Payette and Coeur d’Alene lakes.

An Associated Press story from Arco appeared in 1937 stating that “James Taylor of Boise is testing on the snowbanks of south central Idaho this week his newly invented 'snowmobile.' He brought the machine, a sort of automobile on skis, from Boise on a trailer and is giving it a thorough ‘workout’ in this drifted area.”

That same year, Tom McCall, of McCall, Idaho, was using a 225 horsepower propeller-driven snowmobile to sled along at 50 mph. That snowmobile was to be put in service at Sun Valley Lodge.

For a number of years reports of snowmobile use could mean tracked vehicles or those using airplane engines with propellers. In the early 1940s, newspapers began calling the propeller-driven sleds “snowplanes.”

By 1947 they were holding “national” snowplane races near Spencer, Idaho, the first of which was won by Thomas Katseanes of Hamer. The second annual national snowplane race was held at the airport in DuBois, with Gov. C. A. Robbins in attendance. Tom Katseanes repeated his win.

Snowplane races went on for a few years, dropping further and further back in newspaper pages. The last mention of snowplanes in the Idaho Statesman was in 1972, when a young man was killed near Leadore when the machine he was riding in struck a cattle guard, hurling the spinning prop into the snowplane’s cab.

By the late 60s and early 70s the much more practical tracked snowmobiles, forerunner of the popular recreation vehicles of today, were starting their rise in popularity, thanks in no small part to a friend of mine, Chuck Wells, who started the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation’s snowmobile registration program that provides thousands of miles of groomed trails for riders each year.

You didn't want to stand too close to the prop of a snowplane. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

You didn't want to stand too close to the prop of a snowplane. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

From the January 11, 1870, Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, “Some of the boys have constructed an iceboat which runs by means of machinery and sails. They had it up on the skating park Sunday, and the time made would astonish a locomotive. It don’t exactly fly but just scoots along fast as the wind. The machine carries four persons and ought to be very popular with the ladies. Tom Maupin has charge of the critter, and will probably turn her loose again this afternoon. “

In the Idaho Daily Statesman of December 29, 1932, there ran a story about a mail carrier in Mountain home who had ordered a “snowmobile” so he could better make the trip from there to Rocky Bar and back.

In January, 1937, The Idaho Daily Statesman had a story about a local man whose “gimmick is a propeller-powered plane fuselage mounted on three skis—two in front in the usual place for landing gear, and the third in the rear at the tail skid.” The article noted that similar devices had been used on the ice on Payette and Coeur d’Alene lakes.

An Associated Press story from Arco appeared in 1937 stating that “James Taylor of Boise is testing on the snowbanks of south central Idaho this week his newly invented 'snowmobile.' He brought the machine, a sort of automobile on skis, from Boise on a trailer and is giving it a thorough ‘workout’ in this drifted area.”

That same year, Tom McCall, of McCall, Idaho, was using a 225 horsepower propeller-driven snowmobile to sled along at 50 mph. That snowmobile was to be put in service at Sun Valley Lodge.

For a number of years reports of snowmobile use could mean tracked vehicles or those using airplane engines with propellers. In the early 1940s, newspapers began calling the propeller-driven sleds “snowplanes.”

By 1947 they were holding “national” snowplane races near Spencer, Idaho, the first of which was won by Thomas Katseanes of Hamer. The second annual national snowplane race was held at the airport in DuBois, with Gov. C. A. Robbins in attendance. Tom Katseanes repeated his win.

Snowplane races went on for a few years, dropping further and further back in newspaper pages. The last mention of snowplanes in the Idaho Statesman was in 1972, when a young man was killed near Leadore when the machine he was riding in struck a cattle guard, hurling the spinning prop into the snowplane’s cab.

By the late 60s and early 70s the much more practical tracked snowmobiles, forerunner of the popular recreation vehicles of today, were starting their rise in popularity, thanks in no small part to a friend of mine, Chuck Wells, who started the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation’s snowmobile registration program that provides thousands of miles of groomed trails for riders each year.

You didn't want to stand too close to the prop of a snowplane. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

You didn't want to stand too close to the prop of a snowplane. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Published on October 17, 2020 04:00

October 16, 2020

Poets Laureate

I was helping to produce an interpretive handout for use in the historic home once occupied by my great aunt, Agnes Just Reid when the subject of poet laureates came up. She was a well-known writer in the northwest when she was alive. A family member mentioned that she had been the poet laureate of Idaho. I didn’t think so, because it was the kind of thing I would remember. So, that sent me down a poet laureate path.

Poets laureate were frequently mentioned in early newspapers. Most of those stories were about poets in England, where there was a lot of respect for the title because it was bestowed by the royal family. British poets laureate often graced the pages of the Idaho Statesman in the early days. Alfred Austin was a favorite in the 1890s.

The term was loosely thrown around as an honor for those in clubs and organizations where someone would dash off a rhyme from time to time. Often the title was used in jest. The first mention of an Idaho poet laureate was used that way.

On March 25, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran an article with the headline, Poet Laureate of Idaho is on the Job at State House. “The spring poet may be a joke in some quarters,” the article began, “but he is an actual living, glowing reality in Boise, and with the first warm rain that burst the buds of the trees he blossomed forth and has been busily engaged for the past few days distributing his poems about the statehouse.”

The man was allegedly using the pen name Hask Haskell. No further mention of that name every appeared in the paper again.

But in 1923, it finally happened. Gov. C.C. Moore named Irene Welch Grissom of Idaho Falls Idaho’s first poet laureate. She appeared in stories here and there reading her poems to various groups and releasing new books for many years. Tracking her in a digital search was a little iffy because although everyone seemed to agree on the spelling of her first and last name, her middle name sometimes appeared as Welsh, sometimes Walsh, sometimes Welsch.

Shortly after Idaho named a poet laureate, Wyoming residents decided they needed one. Wyoming Governor W.B. Ross was reluctant to appoint one because he wasn’t sure he had the legal authority. The editor of the Casper Daily Herald was checking into how Idaho had done it, according to a blurb in the Statesman, which quoted Kelly the elevator man at the statehouse as saying, “Now I ask you, what have they in Wyoming to muse about ‘cept rattlesnakes, oil and cows?”

So, snark was alive and well in 1923.

Irene Welch Grissom was apparently expected to serve as Idaho’s poet laureate for life. She did so for many years until she committed a scandalous crime. In 1948 she moved to (gasp!) California.

So, that year, Gov. C.A. Robbins appointed a committee of writers who would nominate a new poet laureate. Agnes Just Reid was on that committee, so that may have been the connection in my cousin’s memory. They recommended, and Gov. Robbins selected, Sudie Stuart Hager of Kimberly as Idaho’s second poet laureate. There was confusion over her middle name in stories, as well. It sometimes appeared as Stewart.

Hager served until her death in 1982.

So, we had two poet laureates. No more. Today, the Idaho Commission on the Arts selects an Idaho Writer in Residence who serves for three years, receiving a modest stipend.

Here’s a list of the Idaho Poets Laureate and Idaho Writers in Residence to date:

Irene Welsh Grissom (1923-1948, poet laureate)

Sudie Stuart Hager (1949-1982, poet laureate)

Ron McFarland (1984-1985) (first person named Writer-in-Residence)

Robert Wrigley (1986-1987)

Eberle Umbach (1988-1989)

Neidy Messer (1990-1991)

Daryl Jones (1992-1993)

Clay Morgan (1994-1995)

Lance Olsen (1996-1998)

Bill Johnson (1999-2000)

Jim Irons (July 2, 2001-2004)

Kim Barnes (April 2004-2006)

Anthony "Tony" Doerr (July 2007-July 2010)

Brady Udall (July 1, 2010-June 20, 2013)

Dianne Raptosh, (July 2013-June 2016)

Christian Winn (July 2016 to June 2019)

Malia Collins (July 2019 to present)

Poets laureate were frequently mentioned in early newspapers. Most of those stories were about poets in England, where there was a lot of respect for the title because it was bestowed by the royal family. British poets laureate often graced the pages of the Idaho Statesman in the early days. Alfred Austin was a favorite in the 1890s.

The term was loosely thrown around as an honor for those in clubs and organizations where someone would dash off a rhyme from time to time. Often the title was used in jest. The first mention of an Idaho poet laureate was used that way.

On March 25, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran an article with the headline, Poet Laureate of Idaho is on the Job at State House. “The spring poet may be a joke in some quarters,” the article began, “but he is an actual living, glowing reality in Boise, and with the first warm rain that burst the buds of the trees he blossomed forth and has been busily engaged for the past few days distributing his poems about the statehouse.”

The man was allegedly using the pen name Hask Haskell. No further mention of that name every appeared in the paper again.

But in 1923, it finally happened. Gov. C.C. Moore named Irene Welch Grissom of Idaho Falls Idaho’s first poet laureate. She appeared in stories here and there reading her poems to various groups and releasing new books for many years. Tracking her in a digital search was a little iffy because although everyone seemed to agree on the spelling of her first and last name, her middle name sometimes appeared as Welsh, sometimes Walsh, sometimes Welsch.

Shortly after Idaho named a poet laureate, Wyoming residents decided they needed one. Wyoming Governor W.B. Ross was reluctant to appoint one because he wasn’t sure he had the legal authority. The editor of the Casper Daily Herald was checking into how Idaho had done it, according to a blurb in the Statesman, which quoted Kelly the elevator man at the statehouse as saying, “Now I ask you, what have they in Wyoming to muse about ‘cept rattlesnakes, oil and cows?”

So, snark was alive and well in 1923.

Irene Welch Grissom was apparently expected to serve as Idaho’s poet laureate for life. She did so for many years until she committed a scandalous crime. In 1948 she moved to (gasp!) California.

So, that year, Gov. C.A. Robbins appointed a committee of writers who would nominate a new poet laureate. Agnes Just Reid was on that committee, so that may have been the connection in my cousin’s memory. They recommended, and Gov. Robbins selected, Sudie Stuart Hager of Kimberly as Idaho’s second poet laureate. There was confusion over her middle name in stories, as well. It sometimes appeared as Stewart.

Hager served until her death in 1982.

So, we had two poet laureates. No more. Today, the Idaho Commission on the Arts selects an Idaho Writer in Residence who serves for three years, receiving a modest stipend.

Here’s a list of the Idaho Poets Laureate and Idaho Writers in Residence to date:

Irene Welsh Grissom (1923-1948, poet laureate)

Sudie Stuart Hager (1949-1982, poet laureate)

Ron McFarland (1984-1985) (first person named Writer-in-Residence)

Robert Wrigley (1986-1987)

Eberle Umbach (1988-1989)

Neidy Messer (1990-1991)

Daryl Jones (1992-1993)

Clay Morgan (1994-1995)

Lance Olsen (1996-1998)

Bill Johnson (1999-2000)

Jim Irons (July 2, 2001-2004)

Kim Barnes (April 2004-2006)

Anthony "Tony" Doerr (July 2007-July 2010)

Brady Udall (July 1, 2010-June 20, 2013)

Dianne Raptosh, (July 2013-June 2016)

Christian Winn (July 2016 to June 2019)

Malia Collins (July 2019 to present)

Published on October 16, 2020 04:00

October 15, 2020

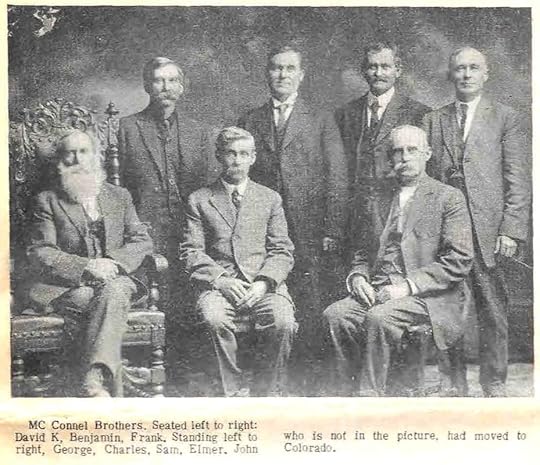

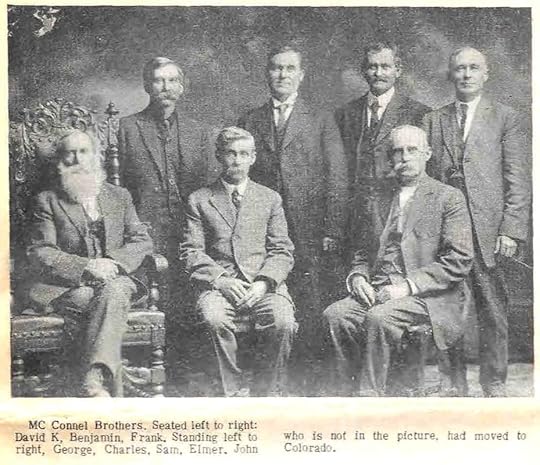

McConnel Island

If you do a Google search for McConnel Island, you’ll come up with a couple of near matches, one for the McConnel Islands, plural, near Antarctica, and one for McConnell Island (note the second L) in the San Jaun Islands in Washington State.

If you’re looking for McConnel Island in Idaho, you’ll have to dig a little deeper. Ask around when you’re in Parma.

In the early days of settlement in that area the Boise River formed a delta, with two channels, one to the north and one to the south, forming a 4000-acre island. In 1865, David McConnel claimed land on the island and built a home there as a squatter. In 1879 he applied for and received a homestead claim of an additional 160 acres, bringing his ranch to about 500 acres. Other families, including that of David’s brother, Ben, lived there, and it even had a McConnel Island School.

David McConnel had come West in 1862 with a large Oregon Trail wagon train. He acted as a scout for that train. McConnel had 11 siblings, 10 brothers and a sister. Eight of his brothers followed him to the Boise Valley from their home in Iowa.

McConnel was a vigilante. That word has a negative note to it today, but it was a point of pride for him. It was the beginning of law and order in the area. In writing about his grandfather, Carl Isenberg recalled McConnel saying that “until the committee was formed and operated on several of the rustlers, murderers, etc., no one could feel secure, but that after a few examples, property and individual safety was secure.”

The island became McConnel Island because of David McConnel’s association with it. It ceased being an island when the Ross Fill was built to block off the southern channel of the river to help solve a frequent flooding problem.

Thanks to Merv McConnel for supplying much of the information used for this story.

If you’re looking for McConnel Island in Idaho, you’ll have to dig a little deeper. Ask around when you’re in Parma.

In the early days of settlement in that area the Boise River formed a delta, with two channels, one to the north and one to the south, forming a 4000-acre island. In 1865, David McConnel claimed land on the island and built a home there as a squatter. In 1879 he applied for and received a homestead claim of an additional 160 acres, bringing his ranch to about 500 acres. Other families, including that of David’s brother, Ben, lived there, and it even had a McConnel Island School.

David McConnel had come West in 1862 with a large Oregon Trail wagon train. He acted as a scout for that train. McConnel had 11 siblings, 10 brothers and a sister. Eight of his brothers followed him to the Boise Valley from their home in Iowa.

McConnel was a vigilante. That word has a negative note to it today, but it was a point of pride for him. It was the beginning of law and order in the area. In writing about his grandfather, Carl Isenberg recalled McConnel saying that “until the committee was formed and operated on several of the rustlers, murderers, etc., no one could feel secure, but that after a few examples, property and individual safety was secure.”

The island became McConnel Island because of David McConnel’s association with it. It ceased being an island when the Ross Fill was built to block off the southern channel of the river to help solve a frequent flooding problem.

Thanks to Merv McConnel for supplying much of the information used for this story.

Published on October 15, 2020 04:00

October 13, 2020

Tolo Lake

Tolo Lake, near Grangeville, was in the news in the fall of 1994 when the Idaho Department of Fish and Game was deepening the drained lake to provide for better fishing. Fish and Game was hoping to take out a dozen feet of silt so that it could better support fish and waterfowl. What they found during the excavation was neither fish nor fowl. It was something much, much larger.

Tolo Lake, which is about 36 acres, was a rendezvous point for the Nez Perce, or nimí·pu, for many years, including at the start of what became the Nez Perce War. Digging there could help wildlife, sure, but it could also shed light on the Tribe’s history. But when the first bone was exposed it was clearly not an artifact of the Nez Perce occupation of the site. It was a leg bone 4 ½ feet tall. Its discovery quickly piqued the interest of archeologists, so scientists from the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho State Historical Society, University of Idaho, and the Idaho Natural History Museum descended on the site where it was quickly determined that these were the bones of mammoths.

Mammoths were not called that for nothing. They weighed 10-15,000 pounds and stood about 14 feet at the shoulder. They were alive in North America as recently as 4,500 to 12,500 years ago, meaning they may have been familiar to the first people on the continent.

The dig exposed the bones of three mammoths and an ancient bison skull. The longest tusk discovered was measured at 16 feet. One of the tusks is on display at the Bicentennial Museum in Grangeville. The town also boasts a mammoth skeleton replica in an interpretive exhibit next to the Grangeville Chamber of Commerce office.

Tolo Lake, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, was named for a Nez Perce woman who alerted settlers of the rampage that started the Nez Perce War.

Tolo Lake, which is about 36 acres, was a rendezvous point for the Nez Perce, or nimí·pu, for many years, including at the start of what became the Nez Perce War. Digging there could help wildlife, sure, but it could also shed light on the Tribe’s history. But when the first bone was exposed it was clearly not an artifact of the Nez Perce occupation of the site. It was a leg bone 4 ½ feet tall. Its discovery quickly piqued the interest of archeologists, so scientists from the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho State Historical Society, University of Idaho, and the Idaho Natural History Museum descended on the site where it was quickly determined that these were the bones of mammoths.

Mammoths were not called that for nothing. They weighed 10-15,000 pounds and stood about 14 feet at the shoulder. They were alive in North America as recently as 4,500 to 12,500 years ago, meaning they may have been familiar to the first people on the continent.

The dig exposed the bones of three mammoths and an ancient bison skull. The longest tusk discovered was measured at 16 feet. One of the tusks is on display at the Bicentennial Museum in Grangeville. The town also boasts a mammoth skeleton replica in an interpretive exhibit next to the Grangeville Chamber of Commerce office.

Tolo Lake, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, was named for a Nez Perce woman who alerted settlers of the rampage that started the Nez Perce War.

Published on October 13, 2020 01:54

October 11, 2020

Idaho's "Foot-Wide" Towns

In the August 20, 1951 edition of Life Magazine there was an article entitled, “Idaho’s Foot-Wide Towns.” The article listed the towns of Banks, Garden City, Island Park, Batise, Chubbuck, Atomic City, and Island Park as examples of same. Crouch was the “foot-wide” town most prevalently featured, population 125, and 10 miles long.

These were the towns exploiting a loophole in state law that allowed slot machines in any incorporated town of 125. That encouraged 17 villages along state highways to incorporate by stretching their boundaries up and down the highway, ballooning out here and there, until they snagged 125 people into their city limits. It was gerrymandering for a different cause.

Several of the featured towns, such as Garden City, didn’t much fit the “foot-wide” definition, though Garden City was created to take advantage of the fact that Boise had voted slot machines out.

The January 18, 1951, edition of the Idaho Statesman featured an article about the controversy over slot machines. It quoted a Fremont County legislator as saying 95 percent of Island Park’s income came “from tourists who like to play slot machines.”

Island Park, which has sometimes boasted that it has the longest Main Street in the country at 33 miles long, didn’t quite fit the foot-wide claim in Life Magazine. Its boundaries are 40 or 50 feet wide at the narrowest.

The Idaho Legislature outlawed slot machines in 1953, but some skinny towns such as Island Park retained their incorporation, so they could serve liquor by the drink, also made possible by the aforementioned loophole.

These were the towns exploiting a loophole in state law that allowed slot machines in any incorporated town of 125. That encouraged 17 villages along state highways to incorporate by stretching their boundaries up and down the highway, ballooning out here and there, until they snagged 125 people into their city limits. It was gerrymandering for a different cause.

Several of the featured towns, such as Garden City, didn’t much fit the “foot-wide” definition, though Garden City was created to take advantage of the fact that Boise had voted slot machines out.

The January 18, 1951, edition of the Idaho Statesman featured an article about the controversy over slot machines. It quoted a Fremont County legislator as saying 95 percent of Island Park’s income came “from tourists who like to play slot machines.”

Island Park, which has sometimes boasted that it has the longest Main Street in the country at 33 miles long, didn’t quite fit the foot-wide claim in Life Magazine. Its boundaries are 40 or 50 feet wide at the narrowest.

The Idaho Legislature outlawed slot machines in 1953, but some skinny towns such as Island Park retained their incorporation, so they could serve liquor by the drink, also made possible by the aforementioned loophole.

Published on October 11, 2020 04:00

October 10, 2020

Tamarack

It's a shame to look at a hillside covered with dead pine trees. You wonder what got them...fire, insects, disease? Sometimes it's difficult to tell. And sometimes, though they look it, they're not dead at all.

Many of us can't tell one type of tree from another. There are so many different kinds. About the only thing we're sure of is that trees with leaves lose them during the winter, and trees with needles keep them year around. That’s an easy rule... until you run across a tamarack.

The western larch, Larix laricina, or tamarack, has needles. Most people would call it a pine tree. But it does the strangest thing in the fall. The tamarack turns orange, or brilliant yellow, then drops its needles.

Tamarack is often mixed in with ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, and lodgepole pine. In the fall the brilliant trees stand out like a scattering of glowing candles among the evergreens.

You can see tamaracks around McCall, in the Little Salmon River country, along the Clearwater River, and many places in northern Idaho. There's a whole hillside due south of New Meadows that is almost covered with tamarack. That's appropriate, because the tiny settlement of Tamarack, Idaho is not far away.

Tamarack wood is heavy and dense. It's often used for utility poles, fence posts, and mine timbers. It doesn't work well in building concrete forms, though. The wood contains a sugar that keeps concrete from curing.

The elves at Wikipedia tell us that the word tamarack is the Algonquian name for the species and means "wood used for snowshoes."

Many of us can't tell one type of tree from another. There are so many different kinds. About the only thing we're sure of is that trees with leaves lose them during the winter, and trees with needles keep them year around. That’s an easy rule... until you run across a tamarack.

The western larch, Larix laricina, or tamarack, has needles. Most people would call it a pine tree. But it does the strangest thing in the fall. The tamarack turns orange, or brilliant yellow, then drops its needles.

Tamarack is often mixed in with ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, and lodgepole pine. In the fall the brilliant trees stand out like a scattering of glowing candles among the evergreens.

You can see tamaracks around McCall, in the Little Salmon River country, along the Clearwater River, and many places in northern Idaho. There's a whole hillside due south of New Meadows that is almost covered with tamarack. That's appropriate, because the tiny settlement of Tamarack, Idaho is not far away.

Tamarack wood is heavy and dense. It's often used for utility poles, fence posts, and mine timbers. It doesn't work well in building concrete forms, though. The wood contains a sugar that keeps concrete from curing.

The elves at Wikipedia tell us that the word tamarack is the Algonquian name for the species and means "wood used for snowshoes."

Published on October 10, 2020 04:00

October 9, 2020

Caribou and Cariboo

There have been, occasionally, caribou in Idaho, and not just when Santa is flying over the state and, once again, pointedly skipping MY house. The caribou that until recently wandered in and out of Idaho in Boundary County, back and forth across the border with Canada, were the only caribou left in the Lower 48. The conservation effort that preserved them was abandoned and in early 2019 the last remaining caribou were removed to Canada.

Note that the caribou were in Boundary County. Caribou County does not have Caribou and never has in recorded history. So why would you name a county after caribou that never get closer than, say 480 miles away?

Residents are quick to tell you that Caribou County is not named after any sort of reindeer. And they are mostly correct. The county is named after “Carriboo” Jack Fairchild, a miner who was among those who first discovered gold on what is now called Caribou Mountain.

But one must wonder where Carriboo Jack got his name. As it turns out, the inveterate storyteller got his nickname because when questioned about the veracity of one of his stories he would often reply, “It is so, I will let you know I am from Cariboo.”

The Cariboo he was from was a mining district in British Columbia, where Fairchild had also worked a claim. The area retains the spelling, with a single “r” today. Carriboo had the extra “r” in his name because, I don’t know, he deserved it? And why don’t the Canadians spell it caribou?

The county in Idaho was called Carriboo until 1921, when someone decided to “correct” it. Caribou Mountian, Caribou City, and the Caribou National Forest all owe their name to Cariboo Jack, the story teller.

One story he often told was about his origins. “I was born in a blizzard snowdrift in the worst storm ever to hit Canada. I was bathed in a gold pan, suckled by a caribou, wrapped in a buffalo rug, and could whip any grizzly going before I was thirteen. That’s when I left home.” A guy like that can spell his name any way he wants.

Much of this story comes from a piece Ellen Carney wrote for the Caribou County website.

Note that the caribou were in Boundary County. Caribou County does not have Caribou and never has in recorded history. So why would you name a county after caribou that never get closer than, say 480 miles away?

Residents are quick to tell you that Caribou County is not named after any sort of reindeer. And they are mostly correct. The county is named after “Carriboo” Jack Fairchild, a miner who was among those who first discovered gold on what is now called Caribou Mountain.

But one must wonder where Carriboo Jack got his name. As it turns out, the inveterate storyteller got his nickname because when questioned about the veracity of one of his stories he would often reply, “It is so, I will let you know I am from Cariboo.”

The Cariboo he was from was a mining district in British Columbia, where Fairchild had also worked a claim. The area retains the spelling, with a single “r” today. Carriboo had the extra “r” in his name because, I don’t know, he deserved it? And why don’t the Canadians spell it caribou?

The county in Idaho was called Carriboo until 1921, when someone decided to “correct” it. Caribou Mountian, Caribou City, and the Caribou National Forest all owe their name to Cariboo Jack, the story teller.

One story he often told was about his origins. “I was born in a blizzard snowdrift in the worst storm ever to hit Canada. I was bathed in a gold pan, suckled by a caribou, wrapped in a buffalo rug, and could whip any grizzly going before I was thirteen. That’s when I left home.” A guy like that can spell his name any way he wants.

Much of this story comes from a piece Ellen Carney wrote for the Caribou County website.

Published on October 09, 2020 04:00