Rick Just's Blog, page 143

November 29, 2020

A Fearless Connection

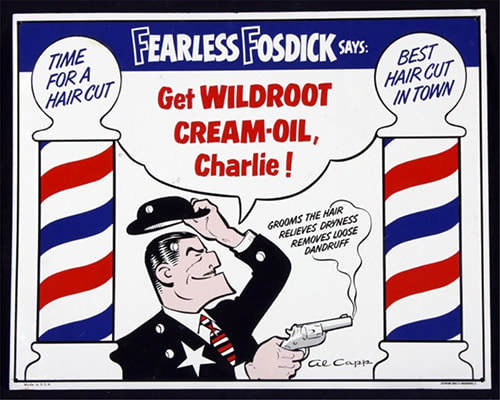

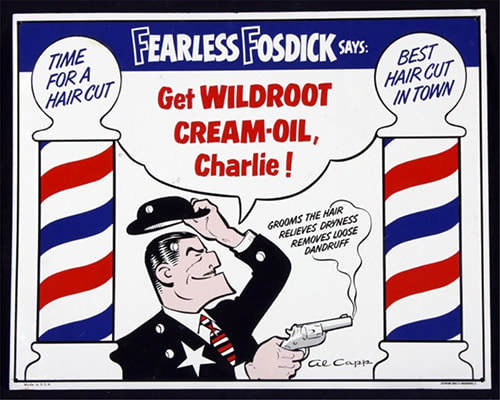

This is a little-known tidbit that I discovered while working on my book about “Fearless” Farris Lind, his Stinker Stations, and the quirky signs that were their signature advertising scheme during the 40s, 50s, and into the 60s.

Given that Farris Lind was a Navy fighter pilot instructor during World War II, and later a crop duster, one might assume that’s where he got the nickname Fearless Farris. Not so. Lind got the idea for the name from Fearless Fosdick, the cartoon character Al Capp drew as a parody of Dick Tracy. Lind knew the alliteration would make it easy to remember. He invented the story that he was Fearless Farris because the “big guy” oil companies didn’t scare him. The first neon sign for his Boise service station featured a boxer under the words “Fearless Farris.”

The iconic skunk, also a boxer, would come along later when a competitor called Lind a “stinker” for his cut rate prices for gasoline. Was Lind insulted? Oh, gosh, no. He latched onto that name like a leg trap. In no time his growing chain of outlets became Stinker Stations with a skunk logo.

There’s much more to tell, of course, stories of tragedy, comedy, and courage. You can find Fearless, Farris Lind, the Man Behind the Skunk in local bookstores and on Amazon.

Given that Farris Lind was a Navy fighter pilot instructor during World War II, and later a crop duster, one might assume that’s where he got the nickname Fearless Farris. Not so. Lind got the idea for the name from Fearless Fosdick, the cartoon character Al Capp drew as a parody of Dick Tracy. Lind knew the alliteration would make it easy to remember. He invented the story that he was Fearless Farris because the “big guy” oil companies didn’t scare him. The first neon sign for his Boise service station featured a boxer under the words “Fearless Farris.”

The iconic skunk, also a boxer, would come along later when a competitor called Lind a “stinker” for his cut rate prices for gasoline. Was Lind insulted? Oh, gosh, no. He latched onto that name like a leg trap. In no time his growing chain of outlets became Stinker Stations with a skunk logo.

There’s much more to tell, of course, stories of tragedy, comedy, and courage. You can find Fearless, Farris Lind, the Man Behind the Skunk in local bookstores and on Amazon.

Published on November 29, 2020 04:00

November 28, 2020

Restoring an 1887 Map

Today, I’m sharing a personal history project with you.

My great grandfather Nels Just, who had recently become a naturalized citizen, was proud of his adopted country. When his brick house along the Blackfoot River was finished in 1887, he ordered a four foot by six foot General Land Office Map of the United States, mounting it to the wall in the hallway of the new house.

The house doubled as the Post Office for Presto, Idaho Territory, then Presto, Idaho beginning in 1890. My great grandmother Emma Just was the postmistress for 13 years, welcoming postal patrons into her home, handing them their mail, and often talking with them about current events, using the map as a conversation tool.

The large map, varnished to ward off fingerprints, had hung unprotected for 127 years. Small pieces of the map had flaked off and it had discolored over the years. In 2014 our family decided to restore and protect the map so it would last at least another century.

With help from the Idaho Heritage Trust, we contracted with a restoration specialist in New York City. To get it to New York, we had to take it off the wall and ship it. That was a process that took several hours. Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus supervised the work.

The map had been mounted on the wall by Nels with lath strips using tacks. The process of safely taking it down included the use of a large “folder” built from fiber board to assure the map stayed flat and did not fall and crumple.

Once we got the map down flat on the large kitchen table in the house, we began removing the lath and tacks. It was then that we discovered that about a one-inch strip at the bottom of the map was missing. Nels had cut it off, none too cleanly. Why? We can’t know, but my guess is that he cut the lath to fit the map, then discovered he’d trimmed the side slats an inch too short. He wasn’t about to harness up a team to take into town to get more lath. So, his solution was just to haggle off the bottom of the map. No one would know. And no one did know until 127 years later. I confess, I would have done the same thing.

We rolled the map on an acid-free cardboard tube, wrapped the map with acid-free paper, placed it in an acid-free box, then placed the box in a length of plastic sewer pipe, filling it out with packing material. We used fitted sewer pipe ends to seal the map and shipped it to New York City.

Restoration on a wall map of this nature first involves removing the map from the original linen backing and then removing the glossy varnish coating the recto. The caustic glues common in the 19th century and the slowly degrading varnish, and exposure to temperature variation, had caused the moderate yellowing and chipping to the map. By having both the linen backing and the varnish removed, the restorer could then access the printed paper map to begin the repair work. When that was finished, the map was laid down on fresh linen and the edging was replaced.

A few months later, the map came back. We had Todd Hanson of Hanson’s Design and Fabrication in Meridian custom build a handsome case for the map, using museum grade Plexiglas to protect it. We displayed the restored map at the Idaho State Historical Archives for a few weeks, and at the Boise Public Library. The Idaho Statehouse hosted it for a day, then it headed to Blackfoot. It was displayed at the Blackfoot Library for a time, then returned to the hallway where it belongs.

The 1887 Just house was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in the summer of 2020. The family had hoped to open the house to the public in the fall of 2020, marking the sesquicentennial of Nels and Emma settling in the Blackfoot River Valley. Covid-19 canceled those plans, as well as so many others. We will be opening the house for tours sometime next summer, COVID-19 permitting. I will keep readers informed when opportunities to visit the house and the map are available. The map is much brighter after restoration. Note that further removal of the streaks of varnish was contraindicated because of possible damage to the map.

The map is much brighter after restoration. Note that further removal of the streaks of varnish was contraindicated because of possible damage to the map.  Electricity was long ago shut off in the 1887 house, so we were working with only what natural light came in through the kitchen windows. Some of the details show up better in black and white. For instance, as the map is being flipped over you can see by the backlighting that it is a series of six printed panels taped together on the back.

Electricity was long ago shut off in the 1887 house, so we were working with only what natural light came in through the kitchen windows. Some of the details show up better in black and white. For instance, as the map is being flipped over you can see by the backlighting that it is a series of six printed panels taped together on the back.  Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus, left, gave us instruction on how best to remove the lath once the map was flat on the table. In the background you can see the large plastic tube that would serve as the hard shipping container for the map.

Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus, left, gave us instruction on how best to remove the lath once the map was flat on the table. In the background you can see the large plastic tube that would serve as the hard shipping container for the map.  The map was carefully wrapped and rolled before being placed in an acid-free cardboard box, then inserted into the shipping container.

The map was carefully wrapped and rolled before being placed in an acid-free cardboard box, then inserted into the shipping container.

My great grandfather Nels Just, who had recently become a naturalized citizen, was proud of his adopted country. When his brick house along the Blackfoot River was finished in 1887, he ordered a four foot by six foot General Land Office Map of the United States, mounting it to the wall in the hallway of the new house.

The house doubled as the Post Office for Presto, Idaho Territory, then Presto, Idaho beginning in 1890. My great grandmother Emma Just was the postmistress for 13 years, welcoming postal patrons into her home, handing them their mail, and often talking with them about current events, using the map as a conversation tool.

The large map, varnished to ward off fingerprints, had hung unprotected for 127 years. Small pieces of the map had flaked off and it had discolored over the years. In 2014 our family decided to restore and protect the map so it would last at least another century.

With help from the Idaho Heritage Trust, we contracted with a restoration specialist in New York City. To get it to New York, we had to take it off the wall and ship it. That was a process that took several hours. Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus supervised the work.

The map had been mounted on the wall by Nels with lath strips using tacks. The process of safely taking it down included the use of a large “folder” built from fiber board to assure the map stayed flat and did not fall and crumple.

Once we got the map down flat on the large kitchen table in the house, we began removing the lath and tacks. It was then that we discovered that about a one-inch strip at the bottom of the map was missing. Nels had cut it off, none too cleanly. Why? We can’t know, but my guess is that he cut the lath to fit the map, then discovered he’d trimmed the side slats an inch too short. He wasn’t about to harness up a team to take into town to get more lath. So, his solution was just to haggle off the bottom of the map. No one would know. And no one did know until 127 years later. I confess, I would have done the same thing.

We rolled the map on an acid-free cardboard tube, wrapped the map with acid-free paper, placed it in an acid-free box, then placed the box in a length of plastic sewer pipe, filling it out with packing material. We used fitted sewer pipe ends to seal the map and shipped it to New York City.

Restoration on a wall map of this nature first involves removing the map from the original linen backing and then removing the glossy varnish coating the recto. The caustic glues common in the 19th century and the slowly degrading varnish, and exposure to temperature variation, had caused the moderate yellowing and chipping to the map. By having both the linen backing and the varnish removed, the restorer could then access the printed paper map to begin the repair work. When that was finished, the map was laid down on fresh linen and the edging was replaced.

A few months later, the map came back. We had Todd Hanson of Hanson’s Design and Fabrication in Meridian custom build a handsome case for the map, using museum grade Plexiglas to protect it. We displayed the restored map at the Idaho State Historical Archives for a few weeks, and at the Boise Public Library. The Idaho Statehouse hosted it for a day, then it headed to Blackfoot. It was displayed at the Blackfoot Library for a time, then returned to the hallway where it belongs.

The 1887 Just house was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in the summer of 2020. The family had hoped to open the house to the public in the fall of 2020, marking the sesquicentennial of Nels and Emma settling in the Blackfoot River Valley. Covid-19 canceled those plans, as well as so many others. We will be opening the house for tours sometime next summer, COVID-19 permitting. I will keep readers informed when opportunities to visit the house and the map are available.

The map is much brighter after restoration. Note that further removal of the streaks of varnish was contraindicated because of possible damage to the map.

The map is much brighter after restoration. Note that further removal of the streaks of varnish was contraindicated because of possible damage to the map.  Electricity was long ago shut off in the 1887 house, so we were working with only what natural light came in through the kitchen windows. Some of the details show up better in black and white. For instance, as the map is being flipped over you can see by the backlighting that it is a series of six printed panels taped together on the back.

Electricity was long ago shut off in the 1887 house, so we were working with only what natural light came in through the kitchen windows. Some of the details show up better in black and white. For instance, as the map is being flipped over you can see by the backlighting that it is a series of six printed panels taped together on the back.  Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus, left, gave us instruction on how best to remove the lath once the map was flat on the table. In the background you can see the large plastic tube that would serve as the hard shipping container for the map.

Textile Conservator Diana Hobart Dicus, left, gave us instruction on how best to remove the lath once the map was flat on the table. In the background you can see the large plastic tube that would serve as the hard shipping container for the map.  The map was carefully wrapped and rolled before being placed in an acid-free cardboard box, then inserted into the shipping container.

The map was carefully wrapped and rolled before being placed in an acid-free cardboard box, then inserted into the shipping container.

Published on November 28, 2020 04:00

November 27, 2020

The Bates Motel

If you’ve seen the 1960 Alfred Hitchcock movie, Psycho starring Janet Leigh, you probably think of it every time you step into a motel shower. That stabbing music—and that stabbing—tend to stick in the brain.

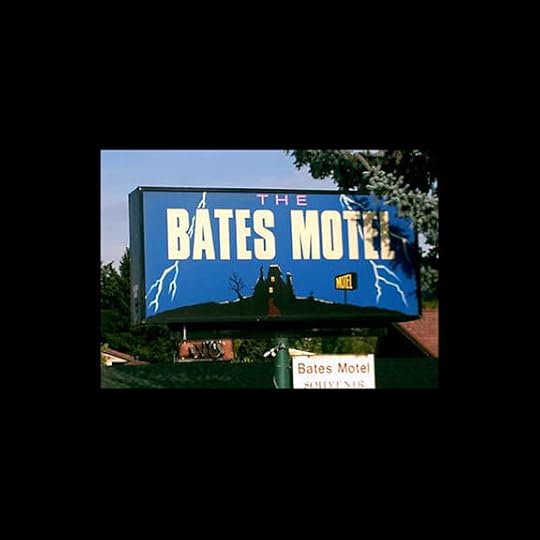

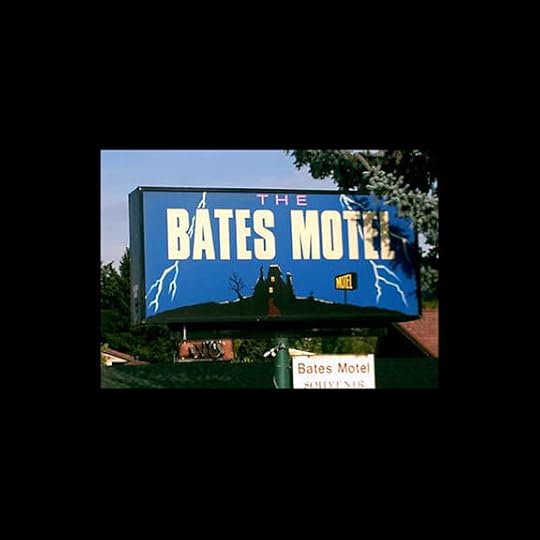

An entrepreneur in Coeur d’Alene either decided to take advantage of the movie’s fame by naming his lodging site the Bates Motel, after the one in the movie, or he happened to be named Bates (possibly Randy Bates), and simply took advantage of the coincidence. Alert readers in Coeur d’Alene will have opinions.

In any case any connection to the movie or the more recent TV series named Bates Motel is tangential at best. There is a rumor, retold endlessly in blurbs such as this one, that Robert Bloch, the man who wrote the book Psycho once stayed at the motel. Good luck chasing that down. Another rumor says that the very Psycho-like sign (photo) that encouraged people to spend the night there for many years was made by a movie production company that used the motel for a movie, or maybe just stayed there.

Gosh, what if they stayed in room 1 or room 3? Did the ashtrays move inexplicably? Did they feel a chill in the air?

Yes, the other thing the Bates Motel was famous for was that it was allegedly haunted, those rooms holding most of the hauntings. There doesn’t seem to be a death associated with the hauntings, so just random ghosts, I guess.

The old motel was originally officer’s quarters at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Maybe. Many old buildings in the area started out there, so that’s not far-fetched.

About the only thing we can say for sure about the Bates Motel once at 2018 E. Sherman Ave., is that it is no longer called that. It’s the Lighthouse, now. No word on whether or not the ghosts moved out in disgust when the name changed.

An entrepreneur in Coeur d’Alene either decided to take advantage of the movie’s fame by naming his lodging site the Bates Motel, after the one in the movie, or he happened to be named Bates (possibly Randy Bates), and simply took advantage of the coincidence. Alert readers in Coeur d’Alene will have opinions.

In any case any connection to the movie or the more recent TV series named Bates Motel is tangential at best. There is a rumor, retold endlessly in blurbs such as this one, that Robert Bloch, the man who wrote the book Psycho once stayed at the motel. Good luck chasing that down. Another rumor says that the very Psycho-like sign (photo) that encouraged people to spend the night there for many years was made by a movie production company that used the motel for a movie, or maybe just stayed there.

Gosh, what if they stayed in room 1 or room 3? Did the ashtrays move inexplicably? Did they feel a chill in the air?

Yes, the other thing the Bates Motel was famous for was that it was allegedly haunted, those rooms holding most of the hauntings. There doesn’t seem to be a death associated with the hauntings, so just random ghosts, I guess.

The old motel was originally officer’s quarters at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Maybe. Many old buildings in the area started out there, so that’s not far-fetched.

About the only thing we can say for sure about the Bates Motel once at 2018 E. Sherman Ave., is that it is no longer called that. It’s the Lighthouse, now. No word on whether or not the ghosts moved out in disgust when the name changed.

Published on November 27, 2020 04:00

November 26, 2020

An Oddball Fish

Would you like to do a little cod fishing in Idaho? You once could, and you didn’t need a deep sea fishing rig. Or, a sea, for that matter.

Burbot, or ling cod are eel-like fish that hold the distinction of being the only freshwater member of the cod family. You won’t confuse them with any other fish. First, there’s that eel-like thing. Then there’s the rounded tail and single whisker, or barbel, sticking out from their lower jaw. Top that off with spots all over their body and you’ll know why they’re sometimes called “The Leopards of the Kootenai.”

The spawning habits of burbot are a little odd. They spawn in the dead of winter in shallow water with much thrashing about involved.

The fish have been important to the Kootenai Tribe for generations. When the Libby Dam went in, just across the border on the Kootenai River in Montana, the population of burbot dropped like a rock. That was in 1974. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game banned fishing for burbot in 1992. By 2004, Fish and Game biologists could capture only a dozen of the fish for research in a five-month period.

An effort to bring back the population, led by the Kootenai Tribe and Bonneville Power, proved successful. The Tribe invested $15 million in a hatchery for burbot and the equally threatened white sturgeon. Now there are an estimated 50,000 ling cod in the river, so for the first time in 27 years a fishing season (year round) was set in 2019.

The fish are sometimes called “the poor man’s lobster” because of their slightly sweet taste.

Burbot, or ling cod are eel-like fish that hold the distinction of being the only freshwater member of the cod family. You won’t confuse them with any other fish. First, there’s that eel-like thing. Then there’s the rounded tail and single whisker, or barbel, sticking out from their lower jaw. Top that off with spots all over their body and you’ll know why they’re sometimes called “The Leopards of the Kootenai.”

The spawning habits of burbot are a little odd. They spawn in the dead of winter in shallow water with much thrashing about involved.

The fish have been important to the Kootenai Tribe for generations. When the Libby Dam went in, just across the border on the Kootenai River in Montana, the population of burbot dropped like a rock. That was in 1974. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game banned fishing for burbot in 1992. By 2004, Fish and Game biologists could capture only a dozen of the fish for research in a five-month period.

An effort to bring back the population, led by the Kootenai Tribe and Bonneville Power, proved successful. The Tribe invested $15 million in a hatchery for burbot and the equally threatened white sturgeon. Now there are an estimated 50,000 ling cod in the river, so for the first time in 27 years a fishing season (year round) was set in 2019.

The fish are sometimes called “the poor man’s lobster” because of their slightly sweet taste.

Published on November 26, 2020 04:00

November 25, 2020

Andrew Henry

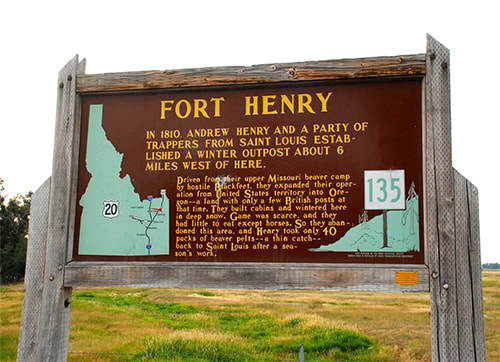

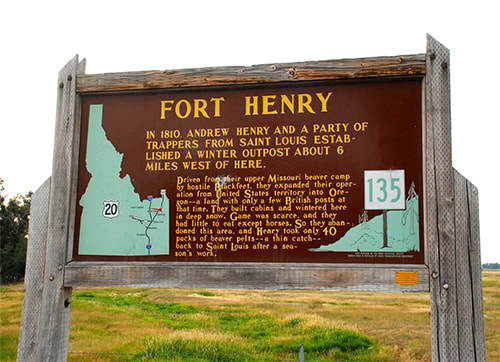

Andrew Henry’s name is all over Southeastern Idaho, all because he spent a hard winter near present-day St. Anthony. Henry and his men were on a trapping expedition, hoping to find a good supply of rodent fur they could liberate from beavers on account of the beavers being dead and all. Felt hats were all the rage.

The Henry party had been in present-day Montana on the upper Missouri on a quest for the slap-tails, but Blackfeet Indians had driven the trappers across the divide at Targhee Pass. They found a location near what would later be called the Henrys Fork of the Snake River, not far from what would later be called Henrys Flat at the foot of the Henrys Lake Mountains, near Henrys Lake, on the shores of which Henrys Lake State Park would one day be, and went about constructing a few cabins for the coming winter.

That winter of 1810 was a rough one for the trappers. The cold had driven buffalo south, so they found little game. The Henry party was reduced to eating some of their horses.

The next spring, they headed back to St. Louis with only 40 packs of pelts which, as everyone knows, was meager for a whole season of trapping.

The buildings they left behind would be much appreciated by the Wilson Price Hunt party the very next winter. They stayed there on their ill-fated trip to Fort Astoria in 1811.

Today, there’s an Idaho State Historical Marker a few miles from the site, and the City of St, Anthony has a monument downtown commemorating what the members of the Henry Party probably thought of as something like, “the winter we ate Sea Biscuit.”

The Henry party had been in present-day Montana on the upper Missouri on a quest for the slap-tails, but Blackfeet Indians had driven the trappers across the divide at Targhee Pass. They found a location near what would later be called the Henrys Fork of the Snake River, not far from what would later be called Henrys Flat at the foot of the Henrys Lake Mountains, near Henrys Lake, on the shores of which Henrys Lake State Park would one day be, and went about constructing a few cabins for the coming winter.

That winter of 1810 was a rough one for the trappers. The cold had driven buffalo south, so they found little game. The Henry party was reduced to eating some of their horses.

The next spring, they headed back to St. Louis with only 40 packs of pelts which, as everyone knows, was meager for a whole season of trapping.

The buildings they left behind would be much appreciated by the Wilson Price Hunt party the very next winter. They stayed there on their ill-fated trip to Fort Astoria in 1811.

Today, there’s an Idaho State Historical Marker a few miles from the site, and the City of St, Anthony has a monument downtown commemorating what the members of the Henry Party probably thought of as something like, “the winter we ate Sea Biscuit.”

Published on November 25, 2020 04:00

November 24, 2020

The Guv Didn't Like it

Rosalie Sorrels, who passed away in 2017, was a much beloved Idaho folksinger and storyteller. Not universally beloved, however. Governor Don Samuelson was one who didn’t care for her or her lyrics.

Folk music has a long, proud history of political involvement and Rosalie never shied from a cause she believed in. In 1970 the cause was saving the White Clouds from a proposed open pit molybdenum mine at the base of Castle Peak. The song, “White Clouds,” was not meant as a particular poke in the eye for Governor Samuelson, though he took it that way. It was a poetic appeal to save wilderness from commercial encroachment and pollution. And it wasn’t so much that the governor was annoyed by Rosalie’s song as he was by the fact that a state employee was singing it. Stacy Gebhards was the Idaho Department of Fish and Game’s fishery management supervisor in 1970.

Gebhards performed “White Clouds” at several events rallying support to save the mountain from development. He and a couple of friends also performed it at a state dinner at which Interior Secretary Walter G. Hickel was in attendance. Governor Samuelson was there, too, and when the accompanying slide show started showing dramatic shots of pollution around the state, Samuelson began steaming.

Hickel later gave Gebhards a personal commendation and congratulatory letter. But word came from the governor’s office that if he ever sang the song in public again, Gebhards would be fired.

Paul Swenson, a writer for the Deseret News out of Salt Lake quoted an un-named source as saying, “The governor blew his stack.”

Gebhards kept his job. Rosalie Sorrels kept writing and singing. Samuelson lost the next to election to Cecil D. Andrus, and Castle Peak remains pristine today.

Much of the information for this post came from Rosalie Sorrels’ book Way out in Idaho: A Celebration of Songs and Stories .

Folk music has a long, proud history of political involvement and Rosalie never shied from a cause she believed in. In 1970 the cause was saving the White Clouds from a proposed open pit molybdenum mine at the base of Castle Peak. The song, “White Clouds,” was not meant as a particular poke in the eye for Governor Samuelson, though he took it that way. It was a poetic appeal to save wilderness from commercial encroachment and pollution. And it wasn’t so much that the governor was annoyed by Rosalie’s song as he was by the fact that a state employee was singing it. Stacy Gebhards was the Idaho Department of Fish and Game’s fishery management supervisor in 1970.

Gebhards performed “White Clouds” at several events rallying support to save the mountain from development. He and a couple of friends also performed it at a state dinner at which Interior Secretary Walter G. Hickel was in attendance. Governor Samuelson was there, too, and when the accompanying slide show started showing dramatic shots of pollution around the state, Samuelson began steaming.

Hickel later gave Gebhards a personal commendation and congratulatory letter. But word came from the governor’s office that if he ever sang the song in public again, Gebhards would be fired.

Paul Swenson, a writer for the Deseret News out of Salt Lake quoted an un-named source as saying, “The governor blew his stack.”

Gebhards kept his job. Rosalie Sorrels kept writing and singing. Samuelson lost the next to election to Cecil D. Andrus, and Castle Peak remains pristine today.

Much of the information for this post came from Rosalie Sorrels’ book Way out in Idaho: A Celebration of Songs and Stories .

Published on November 24, 2020 04:00

November 23, 2020

Steam Donkeys

What would you call a locomotive without wheels? Loggers called them donkeys. About 20 Willamette donkeys, stationary steam engines that made rolls of steel cable spin, operated in the St. Joe drainage at one time. Their purpose was to drag logs off a mountain and into a holding pond where they could be readied for a trip downriver.

Fueled by wood or oil the donkeys turned drums around which 8,000 to 12,000 feet of cable fed. That meant that the donkey puncher (the guy who operated the machine) was usually out of sight of the choker (the man up the mountain rigging the cable around downed trees). To facilitate communication between the donkey puncher and the choker—who might be a mile and-a-half apart—they would run a line all the way back to the steam engine’s whistle. The line was typically in the hands of youngster yet too small for felling trees. He was called the whistle punk. He’d yank on the line a certain number of times when the choker would signal he was ready, or not ready, for the donkey puncher to start rolling in the cable and skidding the logs downhill.

A couple of these old donkeys are still around. The St. Joe Ranger District has built a short hiking trail to one at Marble Creek, called the Hobo Historical Trail, not far from St. Maries. They can give you information how to see it. If you don’t feel like hiking, you can also see one in St. Maries (below), a town very proud of its logging history. In 1958 they rescued one and brought it to a new home on Main in a city park dedicated to that history. You’ll see a statue of John Mullen in the same park, and learn a bit about that famous first road the captain built.

Fueled by wood or oil the donkeys turned drums around which 8,000 to 12,000 feet of cable fed. That meant that the donkey puncher (the guy who operated the machine) was usually out of sight of the choker (the man up the mountain rigging the cable around downed trees). To facilitate communication between the donkey puncher and the choker—who might be a mile and-a-half apart—they would run a line all the way back to the steam engine’s whistle. The line was typically in the hands of youngster yet too small for felling trees. He was called the whistle punk. He’d yank on the line a certain number of times when the choker would signal he was ready, or not ready, for the donkey puncher to start rolling in the cable and skidding the logs downhill.

A couple of these old donkeys are still around. The St. Joe Ranger District has built a short hiking trail to one at Marble Creek, called the Hobo Historical Trail, not far from St. Maries. They can give you information how to see it. If you don’t feel like hiking, you can also see one in St. Maries (below), a town very proud of its logging history. In 1958 they rescued one and brought it to a new home on Main in a city park dedicated to that history. You’ll see a statue of John Mullen in the same park, and learn a bit about that famous first road the captain built.

Published on November 23, 2020 04:00

November 22, 2020

Jim Wardner, Tapeworm remover, etc.

Yes, this is the story about that famous jackass that found the Bunker Hill Mine, but it’s also about an entrepreneur named Jim Wardner, who found a clever way to take advantage of that discovery.

Wardner, by his own account, was a man always on the lookout for whatever would make him rich. With that goal in mind he spent some time as an assistant tapeworm remover, the owner of the exclusive rights to an anti-cow-kicking milking stool in the entire state of Wisconsin, a failed investor in hogs, the exhibitor of a “wild man,” the owner of a saloon and store in Deadwood where he claimed to be the first to sell oysters to gourmand miners, a freighter with 500 yoke of oxen, a gambler who once won a few thousand on a walking contest, and the distributor of butterine (a butter substitute), some of which he personally hauled into Idaho mining camps by pulling a toboggan.

Wardner had done pretty well in the Coeur d’Alene mining district with his various enterprises and was all packed up to go back to Wisconsin to his long-suffering wife, ready to give up his dreams of riches, when an acquaintance he’d grubstaked a bit came galloping into town. Upon seeing Wardner he said he could now pay him back for his past kindness because he and some other men had found one hell of a vein.

Never one to let news of a rich find slide by, Wardner set out that evening to find the mining camp. He came upon it just at sunrise. The three men sitting around the fire knew Wardner and when they saw that he had brought whiskey welcomed him into the camp. As the sun cleared the mountain tops a flash from across the canyon could not be missed. It was sunshine reflecting off a long, exposed vein of galena.

Noah Kellogg told Wardner the now famous story about how his jackass had gotten loose and led the men on a chase through the woods and across downed timber for quite some time until they saw the beast standing still and looking across the canyon as if something had caught his eye. That something was the flash of galena Wardner had now seen. The jackass would forever get credit for the discovery of the Bunker Hill Mine. A refrain from an old concert hall jingle from the time went like this:

“When you talk about the Coeur d’Alenes

And all their wealth untold,

Don’t fail to mention ‘Kellogg’s Jack,’

Who did that wealth unfold!”

Wardner, perhaps the first to hear that story, began thinking of a way to get in on this fabulous find. He told the men he thought he’d take a little stroll and asked if he could borrow an axe in case he needed to blaze a trail. He blazed, instead, a spot in a tree alongside what would later be called Milo Creek and wrote his claim to water rights in the stream in pencil on the blaze. Then he went back to the miners and asked them to come along with him. When they got to the tree, he asked them to witness his claim to water rights.

Men who had not just found wealth beyond their wildest dreams might have simply drowned him on the spot, but they played fair with Wardner and signed as witnesses, knowing that water rights were absolutely essential in mining and kicking themselves for not thinking of that sooner.

Wardner then agreed to put up a considerable sum—more than $15,000—to get the operation going. He bought up some lots in a nearby town which would end up being called Wardner. Eventually he would sell his water rights and mine shares in the Bunker Hill and Sullivan mines, and strike out for other adventures. Chasing gold would take him to the Klondike, South Africa, and British Columbia. There’s another small town named Wardner in British Columbia, named after you know who.

Jim Wardner went on to make and lose fortunes, even trying his hand at raising cats for their fur for a time on an island in Puget Sound. He died in El Paso, Texas in 1905.

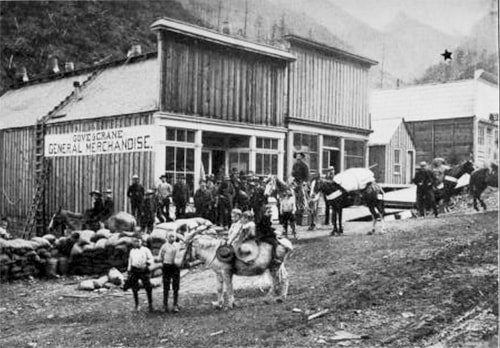

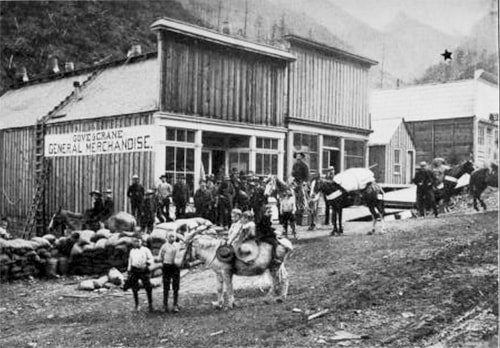

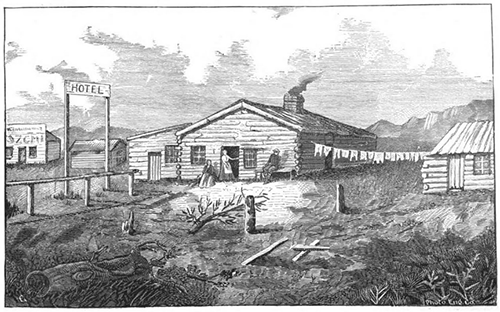

Image: Wardner, Idaho, in 1886. The animal in the foreground with kids astride it is the “4 million dollar” jackass that found the galena that would become the Bunker Hill Mine. The star in the upper right of the photo is the location of the mine. The photo comes from the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho published in 1900, which is an excellent read.

Thanks to Tim Blood who led me to the Wardner book.

Wardner, Idaho in 1886. The $4 million jackass in the foreground. The star marks the site of the Bunker Hill Mine. From the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho.

Wardner, Idaho in 1886. The $4 million jackass in the foreground. The star marks the site of the Bunker Hill Mine. From the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho.

Wardner, by his own account, was a man always on the lookout for whatever would make him rich. With that goal in mind he spent some time as an assistant tapeworm remover, the owner of the exclusive rights to an anti-cow-kicking milking stool in the entire state of Wisconsin, a failed investor in hogs, the exhibitor of a “wild man,” the owner of a saloon and store in Deadwood where he claimed to be the first to sell oysters to gourmand miners, a freighter with 500 yoke of oxen, a gambler who once won a few thousand on a walking contest, and the distributor of butterine (a butter substitute), some of which he personally hauled into Idaho mining camps by pulling a toboggan.

Wardner had done pretty well in the Coeur d’Alene mining district with his various enterprises and was all packed up to go back to Wisconsin to his long-suffering wife, ready to give up his dreams of riches, when an acquaintance he’d grubstaked a bit came galloping into town. Upon seeing Wardner he said he could now pay him back for his past kindness because he and some other men had found one hell of a vein.

Never one to let news of a rich find slide by, Wardner set out that evening to find the mining camp. He came upon it just at sunrise. The three men sitting around the fire knew Wardner and when they saw that he had brought whiskey welcomed him into the camp. As the sun cleared the mountain tops a flash from across the canyon could not be missed. It was sunshine reflecting off a long, exposed vein of galena.

Noah Kellogg told Wardner the now famous story about how his jackass had gotten loose and led the men on a chase through the woods and across downed timber for quite some time until they saw the beast standing still and looking across the canyon as if something had caught his eye. That something was the flash of galena Wardner had now seen. The jackass would forever get credit for the discovery of the Bunker Hill Mine. A refrain from an old concert hall jingle from the time went like this:

“When you talk about the Coeur d’Alenes

And all their wealth untold,

Don’t fail to mention ‘Kellogg’s Jack,’

Who did that wealth unfold!”

Wardner, perhaps the first to hear that story, began thinking of a way to get in on this fabulous find. He told the men he thought he’d take a little stroll and asked if he could borrow an axe in case he needed to blaze a trail. He blazed, instead, a spot in a tree alongside what would later be called Milo Creek and wrote his claim to water rights in the stream in pencil on the blaze. Then he went back to the miners and asked them to come along with him. When they got to the tree, he asked them to witness his claim to water rights.

Men who had not just found wealth beyond their wildest dreams might have simply drowned him on the spot, but they played fair with Wardner and signed as witnesses, knowing that water rights were absolutely essential in mining and kicking themselves for not thinking of that sooner.

Wardner then agreed to put up a considerable sum—more than $15,000—to get the operation going. He bought up some lots in a nearby town which would end up being called Wardner. Eventually he would sell his water rights and mine shares in the Bunker Hill and Sullivan mines, and strike out for other adventures. Chasing gold would take him to the Klondike, South Africa, and British Columbia. There’s another small town named Wardner in British Columbia, named after you know who.

Jim Wardner went on to make and lose fortunes, even trying his hand at raising cats for their fur for a time on an island in Puget Sound. He died in El Paso, Texas in 1905.

Image: Wardner, Idaho, in 1886. The animal in the foreground with kids astride it is the “4 million dollar” jackass that found the galena that would become the Bunker Hill Mine. The star in the upper right of the photo is the location of the mine. The photo comes from the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho published in 1900, which is an excellent read.

Thanks to Tim Blood who led me to the Wardner book.

Wardner, Idaho in 1886. The $4 million jackass in the foreground. The star marks the site of the Bunker Hill Mine. From the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho.

Wardner, Idaho in 1886. The $4 million jackass in the foreground. The star marks the site of the Bunker Hill Mine. From the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho.

Published on November 22, 2020 04:00

November 21, 2020

A Peaceful War

Indians fought losing wars with the United States Government for years during the settlement of the West. They fought for their way of life, their traditions, and mostly for their land.

What might have been the last Indian war was about land, too. No bullets were fired, nor arrows unleashed. The war was declared by a woman, Amy Trice, the chair of the Kootenai Tribe, on September 20, 1974.

The Kootenai had been unrepresented at the signing of the Treaty of Hellgate of 1855. Never-the-less that treaty took away any claim they had to their aboriginal lands and without compensation. They had no reservation.

That lack of representation was something of a Catch 22. Most tribes in the United States are prohibited from declaring war on the country, a clause laid out in multiple treaties. But the Kootenai had never signed a treaty. They weren’t even recognized as a tribe by the U.S.

So, after living in grinding poverty with no land base for 120 years, war it was. To underscore their claim of aboriginal lands, the Kootenai began waving cars over and collecting a voluntary fee of 10 cents to cross their lands on the highway north and south of Bonners Ferry. There was much local resentment of the action and rumors of weaponry being smuggled to the Indians. Members from several tribes began gathering near Bonners Ferry in support of the Kootenai.

The 67-member tribe suggested they would soon begin charging a 50 cent per day business tax and 10 cents per day for dwellings situated on their aboriginal lands.

The Kootenai’s call it a “War of the pen.” The publicity gained by declaring war and charging tolls got the attention of the press, the public, and politicians more than anything the Tribe had tried. In the end, President Gerald Ford signed legislation granting the Tribe 12.5 acres of land surrounding a mission. In the Hellgate Treaty, an estimated 1.6 million acres of land had been taken from the Kootenai.

The 12.5 acres doesn’t seem like much, but it gave the Kootenai a reservation and the legislation recognized the Tribe, clearing the way for eligibility for some government funding. Today, the Kootenai Tribe holds about 2,500 acres of land. They are dedicated to habitat restoration, particularly for sturgeon and burbot.

Amy Trice, the woman who declared war against the U.S., passed away in 2011 at age 75, a heroine to her people.

Amy Trice, courtesy of Idaho Public Television. For more information on Trice and the Kootenai War, click here.

Amy Trice, courtesy of Idaho Public Television. For more information on Trice and the Kootenai War, click here.

What might have been the last Indian war was about land, too. No bullets were fired, nor arrows unleashed. The war was declared by a woman, Amy Trice, the chair of the Kootenai Tribe, on September 20, 1974.

The Kootenai had been unrepresented at the signing of the Treaty of Hellgate of 1855. Never-the-less that treaty took away any claim they had to their aboriginal lands and without compensation. They had no reservation.

That lack of representation was something of a Catch 22. Most tribes in the United States are prohibited from declaring war on the country, a clause laid out in multiple treaties. But the Kootenai had never signed a treaty. They weren’t even recognized as a tribe by the U.S.

So, after living in grinding poverty with no land base for 120 years, war it was. To underscore their claim of aboriginal lands, the Kootenai began waving cars over and collecting a voluntary fee of 10 cents to cross their lands on the highway north and south of Bonners Ferry. There was much local resentment of the action and rumors of weaponry being smuggled to the Indians. Members from several tribes began gathering near Bonners Ferry in support of the Kootenai.

The 67-member tribe suggested they would soon begin charging a 50 cent per day business tax and 10 cents per day for dwellings situated on their aboriginal lands.

The Kootenai’s call it a “War of the pen.” The publicity gained by declaring war and charging tolls got the attention of the press, the public, and politicians more than anything the Tribe had tried. In the end, President Gerald Ford signed legislation granting the Tribe 12.5 acres of land surrounding a mission. In the Hellgate Treaty, an estimated 1.6 million acres of land had been taken from the Kootenai.

The 12.5 acres doesn’t seem like much, but it gave the Kootenai a reservation and the legislation recognized the Tribe, clearing the way for eligibility for some government funding. Today, the Kootenai Tribe holds about 2,500 acres of land. They are dedicated to habitat restoration, particularly for sturgeon and burbot.

Amy Trice, the woman who declared war against the U.S., passed away in 2011 at age 75, a heroine to her people.

Amy Trice, courtesy of Idaho Public Television. For more information on Trice and the Kootenai War, click here.

Amy Trice, courtesy of Idaho Public Television. For more information on Trice and the Kootenai War, click here.

Published on November 21, 2020 04:00

November 20, 2020

A One-Star Review

In these days of Yelp reviews and Air BnB, we’re quite used to seeing personal ratings of overnight accommodations. It wasn’t so common in 1874 when

The Mormon Country, A Summer with the “Latter Day Saints

,” written by John Codman was published.

Codman lauded the mineral springs in Soda Springs and predicted that they would one day “infallibly make it a place of great resort.” His review of the Hotel Sterrit, though, would decidedly get a single star nowadays.

“Some ‘hotels I have seen in the wilds of Africa, the plains of India, the slums of Constantinople; but the ‘Hotel Sterrit’ of Soda Springs is the meanest building of that description into which I ever crept.” He went a step further by insulting the proprietor, to wit, “Sterrit(‘s)… energies seem to be directed to raising a numerous family, and making his boarders pay for it by getting nothing in return for their money.”

There being a single game in town of the hotel variety, Codman spent a fortnight in the Sterrit. He grumped that “I know that I can attribute my health to the waters, for food, of which there was none, could have had nothing to do with it.”

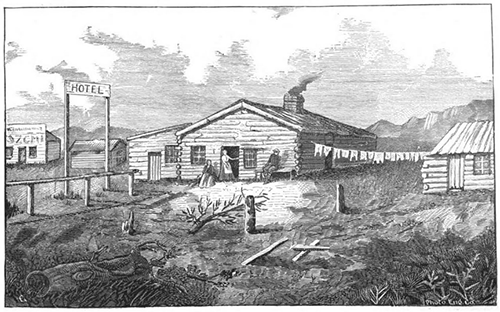

Codman hastened to report that a new and comparatively comfortable hotel was to be completed the next spring. What he didn’t know was that in 1887 a truly luxurious and beautiful hotel would be built in Soda Springs, the original Idanha, fulfilling his resort prophesy. An old woodcut of the Sterrit. A grand hotel it wasn't.

An old woodcut of the Sterrit. A grand hotel it wasn't.

Codman lauded the mineral springs in Soda Springs and predicted that they would one day “infallibly make it a place of great resort.” His review of the Hotel Sterrit, though, would decidedly get a single star nowadays.

“Some ‘hotels I have seen in the wilds of Africa, the plains of India, the slums of Constantinople; but the ‘Hotel Sterrit’ of Soda Springs is the meanest building of that description into which I ever crept.” He went a step further by insulting the proprietor, to wit, “Sterrit(‘s)… energies seem to be directed to raising a numerous family, and making his boarders pay for it by getting nothing in return for their money.”

There being a single game in town of the hotel variety, Codman spent a fortnight in the Sterrit. He grumped that “I know that I can attribute my health to the waters, for food, of which there was none, could have had nothing to do with it.”

Codman hastened to report that a new and comparatively comfortable hotel was to be completed the next spring. What he didn’t know was that in 1887 a truly luxurious and beautiful hotel would be built in Soda Springs, the original Idanha, fulfilling his resort prophesy.

An old woodcut of the Sterrit. A grand hotel it wasn't.

An old woodcut of the Sterrit. A grand hotel it wasn't.

Published on November 20, 2020 04:00