Rick Just's Blog, page 140

December 29, 2020

Doc Hisom

Speaking of Idaho specializes in quirky stories from Idaho history. Often that’s defined as something unexpected. I had writen more than 200 scripts for the official Idaho Centennial radio program, Idaho Snapshots, in 1989 and 1990. A few years ago, I thought it might be fun to bring some of those back in blog form and to write a few others. I ran across a story about Dorthy Johnson, an African-American woman from Pocatello who was chosen as Miss Idaho in 1964. That’s the story that gave me the push to start the Speaking of Idaho blog. You can read it here.

From the very beginning of Idaho, the place was settled mostly by white pioneers. Even today finding a story about a Black Idahoan is a little unexpected. Because of Dorthy Johnson’s unexpected story and its nudge to get me writing, I’m always pleased to share another history vignette about an African-American Idahoan. I’ve written about Aurelius Buckner, Gobo Fango, Tracy Thompson, Elvina Morton, , York, and others.

Today, I add another African American to the list of Idahoans I’ve written about. His history wasn’t especially quirky, but it is a little unexcepted, simply because most of those who did what he did were of another race.

“Doc” Hisom (or Hison, or Hyson, as some references have it), was born in about 1858 a free man in Illinois. In his later years he seemed to delight in telling people he was a little older than he really was, so his birth year is uncertain. His marker in the Kohlerlawn Cemetery in Nampa, lists his birth date as October 6, 1850.

William C. Hisom came by his nickname legitimately. He had trained as a veterinarian and worked as one for some years before coming to Idaho to seek his fortune as a miner in the late 1800s. He, a Black man, partnered up with a white man named White. They claimed a 20-acre parcel along the Snake River near Melba in 1906 or 1907. They worked their claim for a few years before White drifted away. Doc Hisom lived there for the rest of his life.

Hisom was well known in the area as a storyteller and for his proficiency in practicing Native American and pioneer skills, such as flint knapping and working leather. One reference mentioned that he had at least some Indian blood.

A man of any color living miles from anywhere by his own hand doesn’t make the newspaper very often. I found just one story about him in the Idaho Statesman. It reported a big event in his life. In October of 1921, Doc Hisom made his way into Boise for the second time in 36 years. He marveled at the electric lights and the rapid transit of the city. The miner took his first ride on a streetcar and in an automobile during that trip.

The paper reported that the recluse was a friend of “Two-Gun Bob” Limbert, the man who almost single-handedly got Craters of the Moon named a national monument. Limbert often stayed at Hisom’s cabin. They probably discussed photography, among other things, since both were accomplished photographers. Taxidermy was a skill they also shared. Hisom may have entertained “Two-Gun Bob” by playing music for him. He could play seven instruments.

We don’t know for certain when Doc Hisom was born, but we do know when he died. That was December 26, 1944.

“Doc” Hisom working leather at his cabin along the Snake River.

“Doc” Hisom working leather at his cabin along the Snake River.

From the very beginning of Idaho, the place was settled mostly by white pioneers. Even today finding a story about a Black Idahoan is a little unexpected. Because of Dorthy Johnson’s unexpected story and its nudge to get me writing, I’m always pleased to share another history vignette about an African-American Idahoan. I’ve written about Aurelius Buckner, Gobo Fango, Tracy Thompson, Elvina Morton, , York, and others.

Today, I add another African American to the list of Idahoans I’ve written about. His history wasn’t especially quirky, but it is a little unexcepted, simply because most of those who did what he did were of another race.

“Doc” Hisom (or Hison, or Hyson, as some references have it), was born in about 1858 a free man in Illinois. In his later years he seemed to delight in telling people he was a little older than he really was, so his birth year is uncertain. His marker in the Kohlerlawn Cemetery in Nampa, lists his birth date as October 6, 1850.

William C. Hisom came by his nickname legitimately. He had trained as a veterinarian and worked as one for some years before coming to Idaho to seek his fortune as a miner in the late 1800s. He, a Black man, partnered up with a white man named White. They claimed a 20-acre parcel along the Snake River near Melba in 1906 or 1907. They worked their claim for a few years before White drifted away. Doc Hisom lived there for the rest of his life.

Hisom was well known in the area as a storyteller and for his proficiency in practicing Native American and pioneer skills, such as flint knapping and working leather. One reference mentioned that he had at least some Indian blood.

A man of any color living miles from anywhere by his own hand doesn’t make the newspaper very often. I found just one story about him in the Idaho Statesman. It reported a big event in his life. In October of 1921, Doc Hisom made his way into Boise for the second time in 36 years. He marveled at the electric lights and the rapid transit of the city. The miner took his first ride on a streetcar and in an automobile during that trip.

The paper reported that the recluse was a friend of “Two-Gun Bob” Limbert, the man who almost single-handedly got Craters of the Moon named a national monument. Limbert often stayed at Hisom’s cabin. They probably discussed photography, among other things, since both were accomplished photographers. Taxidermy was a skill they also shared. Hisom may have entertained “Two-Gun Bob” by playing music for him. He could play seven instruments.

We don’t know for certain when Doc Hisom was born, but we do know when he died. That was December 26, 1944.

“Doc” Hisom working leather at his cabin along the Snake River.

“Doc” Hisom working leather at his cabin along the Snake River.

Published on December 29, 2020 04:00

December 28, 2020

A Firtht

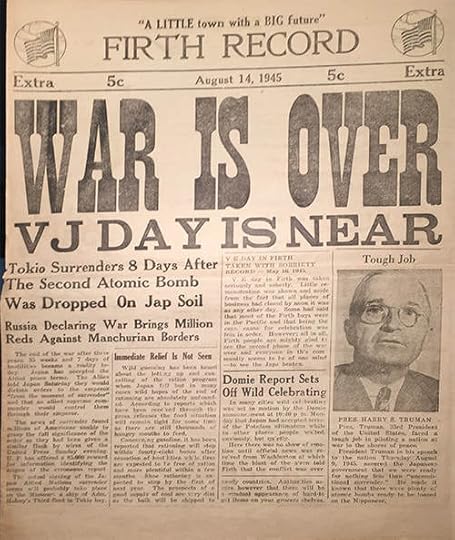

Chances are you’ve never heard of The Firth Record. It was the town paper of Firth, publishing from 1945 into the early 1950s. Copies of the old paper are so rare that the Idaho State Historical Society doesn’t have any in their microfilm collection at the state archives. I’ve recently come into possession of 26 editions of the paper, thanks to preservation-minded members of my family, particularly Kathy Christiansen. I’ve asked the Historical Society to scan them for the archives. Once that’s done, they will be donated to the Bingham County Historical Society.

Meanwhile, I ran across a surprising claim to fame for The Firth Record. In a retrospective published in the January 28, 1949 edition, the editor noted that one of the “extras” the paper had published drew “acclaim all over the nation, as the first to hit the streets, after the memorable Japanese surrender, marking the end of hostilities in a war torn world.”

Why? The editor explained. “Four months after the war’s end, The Firth Record was given national and international notoriety, with the announcement that it was the ‘firstest’ among the firsts. This was disclosed by the Publishers Auxiliary, a weekly newspaper published in Chicago.”

So, a Firth first. Further, the first Firthian to read the paper was Harold Brighton, who had it in his hands two minutes after it came off the press.

That moment of fame is gratifying to those of us from Firth who have endured jokes over the years such as, “Firth? Is that near Thecond?”

Meanwhile, I ran across a surprising claim to fame for The Firth Record. In a retrospective published in the January 28, 1949 edition, the editor noted that one of the “extras” the paper had published drew “acclaim all over the nation, as the first to hit the streets, after the memorable Japanese surrender, marking the end of hostilities in a war torn world.”

Why? The editor explained. “Four months after the war’s end, The Firth Record was given national and international notoriety, with the announcement that it was the ‘firstest’ among the firsts. This was disclosed by the Publishers Auxiliary, a weekly newspaper published in Chicago.”

So, a Firth first. Further, the first Firthian to read the paper was Harold Brighton, who had it in his hands two minutes after it came off the press.

That moment of fame is gratifying to those of us from Firth who have endured jokes over the years such as, “Firth? Is that near Thecond?”

Published on December 28, 2020 04:00

December 27, 2020

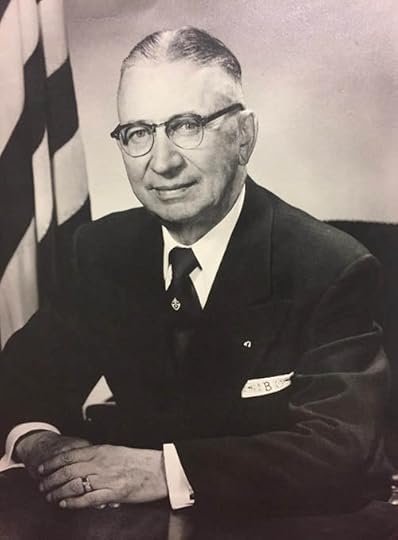

Clarence Bottolfsen

It would probably not surprise you that a 19-year-old “printer’s devil” (apprentice) went on to purchase and operate a small-town newspaper in Idaho. Clarence Bottolfsen was that young man. A North Dakota publisher founded the Arco Advertiser in 1909 and sent for Bottolfsen who had assisted him on publications in that state. In a few years young Bottolfsen purchased the Arco paper. He would run it until 1949 and would also serve as editor and general manager of the Blackfoot Daily Bulletin from 1934-1938. He was elected president of the Idaho Editorial Association in 1929.

So, a newspaper man through and through. No surprise. What might be news to you is why he is well-known in Idaho history.

Clarence A. Bottolfsen participated in Idaho politics. A lot. He served in the Idaho House of Representatives in the 1921 and 1923 session, back when the legislature met every other year. He had the appointed position of chief clerk of the House in 1925 and 1927, then came back as an elected representative in 1929 and 1931, serving as speaker of the house in 1931. He worked as Republican State Chair in 1936 and 37. In 1938 Idaho citizens elected him governor. In 1940 he ran for that office, again, but lost to Chase Clark. He had better luck in 1942, defeating Clark and serving a second term, making him the first governor in Idaho to serve in non-consecutive terms. Cecil D. Andrus was the second.

Bottolfsen ran for U.S. Senate in 1944, losing to Glen H. Taylor. He was appointed chief clerk of the Idaho House in 1949 and 1951. In 1953 he served as Deputy Sergeant of Arms of the U.S. Senate. He was back in Idaho in 1955 and 1956, serving again as the Chief Clerk of the Idaho House.

In 1958. Bottolfsen ran for a seat in the Idaho Senate. He won, serving until 1962 when his health precluded another run.

If you think serving as governor, twice, several terms in the Idaho House and Senate, and various political appointments, along with running a newspaper was enough to keep Bottolfsen busy, you’d be wrong. He was elected permanent parliamentarian for the National Education Association in 1937, a post he held for 17 years. Bottolfsen also served as State Commander of the American Legion (he served in the army during WWI) and was active in the Masons, and the Arco Chamber of Commerce and Rotary Club.

C.A. Bottolfsen passed away at the VA Hospital in Boise in 1964. He was 72.

Dedicated Idaho politician C.A. Bottolfsen.

Dedicated Idaho politician C.A. Bottolfsen.

So, a newspaper man through and through. No surprise. What might be news to you is why he is well-known in Idaho history.

Clarence A. Bottolfsen participated in Idaho politics. A lot. He served in the Idaho House of Representatives in the 1921 and 1923 session, back when the legislature met every other year. He had the appointed position of chief clerk of the House in 1925 and 1927, then came back as an elected representative in 1929 and 1931, serving as speaker of the house in 1931. He worked as Republican State Chair in 1936 and 37. In 1938 Idaho citizens elected him governor. In 1940 he ran for that office, again, but lost to Chase Clark. He had better luck in 1942, defeating Clark and serving a second term, making him the first governor in Idaho to serve in non-consecutive terms. Cecil D. Andrus was the second.

Bottolfsen ran for U.S. Senate in 1944, losing to Glen H. Taylor. He was appointed chief clerk of the Idaho House in 1949 and 1951. In 1953 he served as Deputy Sergeant of Arms of the U.S. Senate. He was back in Idaho in 1955 and 1956, serving again as the Chief Clerk of the Idaho House.

In 1958. Bottolfsen ran for a seat in the Idaho Senate. He won, serving until 1962 when his health precluded another run.

If you think serving as governor, twice, several terms in the Idaho House and Senate, and various political appointments, along with running a newspaper was enough to keep Bottolfsen busy, you’d be wrong. He was elected permanent parliamentarian for the National Education Association in 1937, a post he held for 17 years. Bottolfsen also served as State Commander of the American Legion (he served in the army during WWI) and was active in the Masons, and the Arco Chamber of Commerce and Rotary Club.

C.A. Bottolfsen passed away at the VA Hospital in Boise in 1964. He was 72.

Dedicated Idaho politician C.A. Bottolfsen.

Dedicated Idaho politician C.A. Bottolfsen.

Published on December 27, 2020 04:00

December 26, 2020

Those Cursed Canvas Dams

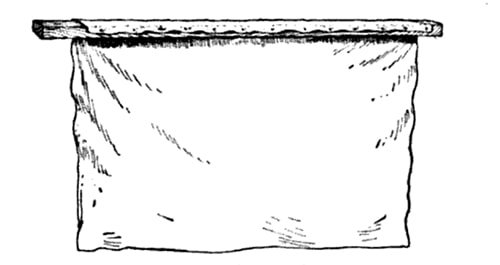

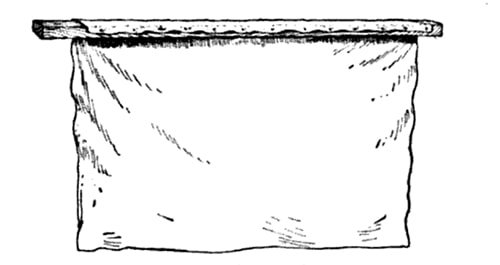

When you think of a dam, Hoover probably comes to mind, or maybe Lucky Peak. Both have Idaho stories behind them. Today, though, I’d like to recognize the lowliest of irrigation control devices, the canvas dam.

If you didn’t grow up on a farm you may never have even heard of a canvas dam. They are a marvel. They are simple, portable, durable, functional, and cheap. I’m going to let someone eminently more qualified than myself describe canvas dams and their use.

How much more qualified? Well, in the publication Irrigation in the United States which was published in 1902, its author, Frederick Haynes Newell, was described as “Hydraulic Engineer and Chief of the Division of Hydrography of the United States Geological Survey; Member of the American Society of Civil Engineers; Expert on Irrigation for the Eleventh and Twelfth United States Censuses; Secretary of the American Forestry Association, etc.”

Mr. Newell said that a canvas dam “consists of a piece of stout cloth, one edge of which is tacked to a stick long enough to extend across the lateral ditch or furrow. The canvas, falling into the furrow, fits the sides and bottoms, and is held in place by a clod of dirt thrown upon it. Water meeting the obstruction still further forces the canvas down, making a fairly tight dam, against which it accumulates and overflows into the field.”

I remember often seeing my father don his rubber waders and head out to a field with a small dam, canvas loosely wrapped around the pole, propped on one shoulder, a shovel across the other. If the ditch was big, so was the dam, so he’d usually be dragging those.

Gravity irrigation is not easy work, but I think it was his favorite work that did not involve straddling a horse. Encouraging water to flow down furrows or across pasture land gave him time to think and enjoy the weather.

My great aunt, Agnes Just Reid, knew about such men and honored them in poetry more than once.

The Man With the Shovel

After the work of construction

After the dam is made,

After the dream is realized

That has been long delayed:

Then comes the man with the shovel,

The man who is king in the west,

He takes up the ceaseless burden

And lets the dam builder rest.

He may not have vision of learning,

He may not have time to dream,

But he knows a field of sagebrush

And an irrigation stream.

Take away men of theories

With their plans so futile and dim,

But leave us the man with the shovel,

We cannot live without him!

She did not mention canvas dams, as if shovels would do the trick alone. She also did not mention the obligatory swearing when no matter how much sod a man would put on the canvas to hold it in place the dam would wash out, canvas flapping downstream like a wagging tongue.

Canvas dams were ubiquitous for about a hundred years on Idaho farms. No doubt there are a few of them in use today. Yet, do a Google images search for Canvas Dam and only one decent picture comes up, that one from Nevada in the 1980s and in the Smithsonian collection.

That doesn’t make the canvas dam picture in your old family album valuable, but it does make it rare. Share it if you have one.

If you didn’t grow up on a farm you may never have even heard of a canvas dam. They are a marvel. They are simple, portable, durable, functional, and cheap. I’m going to let someone eminently more qualified than myself describe canvas dams and their use.

How much more qualified? Well, in the publication Irrigation in the United States which was published in 1902, its author, Frederick Haynes Newell, was described as “Hydraulic Engineer and Chief of the Division of Hydrography of the United States Geological Survey; Member of the American Society of Civil Engineers; Expert on Irrigation for the Eleventh and Twelfth United States Censuses; Secretary of the American Forestry Association, etc.”

Mr. Newell said that a canvas dam “consists of a piece of stout cloth, one edge of which is tacked to a stick long enough to extend across the lateral ditch or furrow. The canvas, falling into the furrow, fits the sides and bottoms, and is held in place by a clod of dirt thrown upon it. Water meeting the obstruction still further forces the canvas down, making a fairly tight dam, against which it accumulates and overflows into the field.”

I remember often seeing my father don his rubber waders and head out to a field with a small dam, canvas loosely wrapped around the pole, propped on one shoulder, a shovel across the other. If the ditch was big, so was the dam, so he’d usually be dragging those.

Gravity irrigation is not easy work, but I think it was his favorite work that did not involve straddling a horse. Encouraging water to flow down furrows or across pasture land gave him time to think and enjoy the weather.

My great aunt, Agnes Just Reid, knew about such men and honored them in poetry more than once.

The Man With the Shovel

After the work of construction

After the dam is made,

After the dream is realized

That has been long delayed:

Then comes the man with the shovel,

The man who is king in the west,

He takes up the ceaseless burden

And lets the dam builder rest.

He may not have vision of learning,

He may not have time to dream,

But he knows a field of sagebrush

And an irrigation stream.

Take away men of theories

With their plans so futile and dim,

But leave us the man with the shovel,

We cannot live without him!

She did not mention canvas dams, as if shovels would do the trick alone. She also did not mention the obligatory swearing when no matter how much sod a man would put on the canvas to hold it in place the dam would wash out, canvas flapping downstream like a wagging tongue.

Canvas dams were ubiquitous for about a hundred years on Idaho farms. No doubt there are a few of them in use today. Yet, do a Google images search for Canvas Dam and only one decent picture comes up, that one from Nevada in the 1980s and in the Smithsonian collection.

That doesn’t make the canvas dam picture in your old family album valuable, but it does make it rare. Share it if you have one.

Published on December 26, 2020 04:00

December 25, 2020

Merry Christmas!

Here's a little cartoon snapshot from the Idaho Statesman in 1904 for your 2020 Christmas Day.

Published on December 25, 2020 04:00

December 24, 2020

A Ghostly Tale

Reginald Owen was visited by three ghosts in 1938. One of them pointed a shaking, boney finger at a headstone with his name on it. Well, the name of his character, Ebenezer Scrooge. Owen’s actual headstone, though, is in the Morris Hill Cemetery in Boise.

Owen was widely acclaimed for his role as Scrooge. This time of year, the movie is played and replayed to—forgive the pun—death. Scrooge was probably his best remembered character, but he played many of them. Notably, he played both Sherlock Holmes and Watson several times each. The same year he played Scrooge, Owen appeared in another movie as a character named Grump. Fortunately, that didn’t typecast him.

Reggie Owen’s career in film began in 1911 when he appeared as Thomas Cromwell in Henry VIII. His last film was Bedknobs and Broomsticks in 1971 in which he played Major General Sir Brian Teagler. Some might remember him as Admiral Boom in Mary Poppins.

His life on stage was at least equal to his film career and he was a radio star as well. In the TV era he had a part in an episode of Maverick with James Garner.

Finally, of trivial note, Owen rented his mansion in Bel Air to the Beatles when they performed at the Hollywood Bowl when no hotel would book them.

And, Boise? Owen had just wrapped up an appearance in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum in New York, when he and his wife decided to visit her son from a previous marriage. Robert Haveman was a labor relations manager at Boise Cascade. The former Barbara Haveman, Owen’s third wife, was a descendent of Russian nobility who had married the actor when he was 69. He spent the last three months of his life in Boise. A stroke or heart attack took him in 1972 at age 85.

Reginald Owen as Scrooge in 1938.

Reginald Owen as Scrooge in 1938.  The headstone of Reginald Owen at Morris Hill Cemetery in Boise.

The headstone of Reginald Owen at Morris Hill Cemetery in Boise.

Owen was widely acclaimed for his role as Scrooge. This time of year, the movie is played and replayed to—forgive the pun—death. Scrooge was probably his best remembered character, but he played many of them. Notably, he played both Sherlock Holmes and Watson several times each. The same year he played Scrooge, Owen appeared in another movie as a character named Grump. Fortunately, that didn’t typecast him.

Reggie Owen’s career in film began in 1911 when he appeared as Thomas Cromwell in Henry VIII. His last film was Bedknobs and Broomsticks in 1971 in which he played Major General Sir Brian Teagler. Some might remember him as Admiral Boom in Mary Poppins.

His life on stage was at least equal to his film career and he was a radio star as well. In the TV era he had a part in an episode of Maverick with James Garner.

Finally, of trivial note, Owen rented his mansion in Bel Air to the Beatles when they performed at the Hollywood Bowl when no hotel would book them.

And, Boise? Owen had just wrapped up an appearance in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum in New York, when he and his wife decided to visit her son from a previous marriage. Robert Haveman was a labor relations manager at Boise Cascade. The former Barbara Haveman, Owen’s third wife, was a descendent of Russian nobility who had married the actor when he was 69. He spent the last three months of his life in Boise. A stroke or heart attack took him in 1972 at age 85.

Reginald Owen as Scrooge in 1938.

Reginald Owen as Scrooge in 1938.  The headstone of Reginald Owen at Morris Hill Cemetery in Boise.

The headstone of Reginald Owen at Morris Hill Cemetery in Boise.

Published on December 24, 2020 04:00

December 23, 2020

The Kleinschmidt Grade

Albert Kleinschmidt had more money than he needed. He was a wealthy merchant and mine owner in Helena, Montana who made an expensive decision that would result in little more than getting his name on some Idaho maps.

Kleinschmidt bought into a trio of mines, the Helena, the Peacock, and the White Monument, in Idaho’s Seven Devils country in 1885. I obsessed most Idaho miners at the time with gold and silver, but these were copper mines. They were difficult to get to on foot or by mule. Getting there wasn’t the problem, though. It was getting copper ore out and to market that was an issue. You can pack only so much ore out in your pockets.

Our money man from Helena thought the solution might be a road down to the Snake River where steamboats could load up the ore and move it to Weiser to catch the nearest railroad line.

Building the road went fast, but that doesn’t mean it was easy. Kleinschmidt threw money into the construction, hiring experienced crews and pushing them to work on the road in all weather. It took them a couple of years, but the result was a 22-mile tangle of switchbacks that dropped 3,000 feet into Hells Canyon. The Kleinschmidt Grade was completed July 31, 1891. It cost $20,000.

Lounging in a chair today with our hindsight firmly installed, we can ask why the heck Kleinschmidt didn’t try the steamboat leg of the plan first, before putting so much money into the road. They built the Norma in 1891 for the purpose of hauling ore to Weiser, only to find out that navigating a steamboat up to the terminus of the road was treacherous. At about the same time they learned that little tidbit of information, the price of copper dropped through the floor.

Others had some later success in getting copper out, but no one ever made any money on it. Losing money on mining operations in the Seven Devils has been something of a tradition ever since Albert Kleinschmidt built that twisty memorial to himself.

You can take the Kleinschmidt Grade today if you have a vehicle that is ready for it. Be on the lookout for oncoming traffic. Two rigs can’t get by each other just anywhere on the road.

Kleinschmidt bought into a trio of mines, the Helena, the Peacock, and the White Monument, in Idaho’s Seven Devils country in 1885. I obsessed most Idaho miners at the time with gold and silver, but these were copper mines. They were difficult to get to on foot or by mule. Getting there wasn’t the problem, though. It was getting copper ore out and to market that was an issue. You can pack only so much ore out in your pockets.

Our money man from Helena thought the solution might be a road down to the Snake River where steamboats could load up the ore and move it to Weiser to catch the nearest railroad line.

Building the road went fast, but that doesn’t mean it was easy. Kleinschmidt threw money into the construction, hiring experienced crews and pushing them to work on the road in all weather. It took them a couple of years, but the result was a 22-mile tangle of switchbacks that dropped 3,000 feet into Hells Canyon. The Kleinschmidt Grade was completed July 31, 1891. It cost $20,000.

Lounging in a chair today with our hindsight firmly installed, we can ask why the heck Kleinschmidt didn’t try the steamboat leg of the plan first, before putting so much money into the road. They built the Norma in 1891 for the purpose of hauling ore to Weiser, only to find out that navigating a steamboat up to the terminus of the road was treacherous. At about the same time they learned that little tidbit of information, the price of copper dropped through the floor.

Others had some later success in getting copper out, but no one ever made any money on it. Losing money on mining operations in the Seven Devils has been something of a tradition ever since Albert Kleinschmidt built that twisty memorial to himself.

You can take the Kleinschmidt Grade today if you have a vehicle that is ready for it. Be on the lookout for oncoming traffic. Two rigs can’t get by each other just anywhere on the road.

Published on December 23, 2020 04:00

December 22, 2020

The Ross Hall Girls

During World War II, more than 292,000 “boots” trained at Farragut Naval Training Station, north of Coeur d’Alene. Sandpoint, Idaho, photographer Ross Hall provided class photographs the boots could buy. The photographs included a list of those pictured. It was quite a production.

The shot below shows three “Ross Hall Girls,” who kept track of names of those in the pictures and took orders. They’re shown in their booths with a class lined up for a photograph in the background. Ross Hall himself probably took this picture. To give you an idea of the scale of this operation, In March 1944, a record 20,891 boots had their pictures taken.

Hundreds of company photos are on file today at Farragut State Park to help those wanting to know more about family members who went through training at Farragut Naval Training Station.

The shot below shows three “Ross Hall Girls,” who kept track of names of those in the pictures and took orders. They’re shown in their booths with a class lined up for a photograph in the background. Ross Hall himself probably took this picture. To give you an idea of the scale of this operation, In March 1944, a record 20,891 boots had their pictures taken.

Hundreds of company photos are on file today at Farragut State Park to help those wanting to know more about family members who went through training at Farragut Naval Training Station.

Published on December 22, 2020 04:00

December 21, 2020

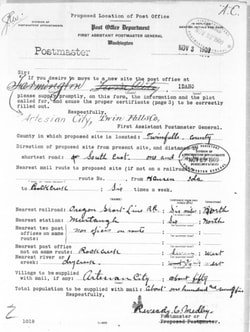

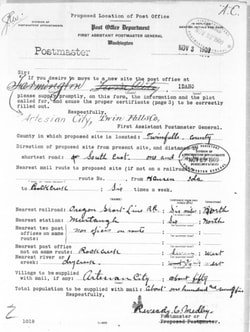

Artesian City

Water in the West is precious. “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over,” said Mark Twain. Possibly. No one has ever nailed down that quote as his, but it says a lot about the value of water in an arid country.

Imagine how settlers must have felt when they heard about water bubbling out of the desert all by itself in seemingly endless quantities. Bonus: The water came springing out of the earth at 110 degrees like a gift from God.

Artesian City came into existence because of two wells that James E. Bower drilled on the Cassia-Twin Falls county line a couple of miles south of Murtaugh Lake in 1895. Bower watered his cattle with the wells for a while, but he thought they might be an attractant for farmers whose crops might benefit from warm water.

By 1909, Bower had enticed a couple dozen families to purchase property from him. And, indeed, the crops seemed to respond well to warm water. Potatoes faired particularly well. Cattle seemed to do better drinking all the warm winter water they wanted. A couple of cattlemen from California moved 5,000 head into the area. The claim was that feeding alfalfa to cows that had access to warm water was worth about $1 a ton in feeding value.

Artesian City popped up with a general store, school, hotel, a couple of dance halls, a livery stable, a post office and a cemetery. The post office operated just a couple of years, from 1909 to 1911. The cemetery is still… operating.

In 1910, developers brought a sanatorium to Artesian City “for the cure of the ailments of humanity,” according to an Idaho Statesman article at the time. The project included a 40-room hotel with each room offering a bathtub in which one could soak privately in hot water. The water contained “Sulphur, iron, and magnesia in quantities that render it valuable in the eradication of many diseases of the human family.”

The sanatorium lasted into the 40s. The wells were capped after that. Some say drilling for irrigation water in the area has since killed the artesian effect.

One footnote worth mentioning is that James Bower, who dreamed of providing warm water to crops, played another role in Idaho history. He was the ranch foreman who hired “Diamondfield” Jack Davis. More important, he was one of the men who confessed to the murder of a pair of sheepherders that Davis had been convicted of killing. That confession freed “Diamondfield” Jack and seemed to have done Bower no discernable harm.

The two artesian wells drilled by James Bower in 1895 bubbled up ten feet high.

The two artesian wells drilled by James Bower in 1895 bubbled up ten feet high.  The sanatorium at Artesian City.

The sanatorium at Artesian City.

The application for a post office showed some indecision on the part of residents. Two town names were crossed out before they settled on Artesian City. Image courtesy of Bob Omberg who has the best collection of information about Idaho post offices that I know of.

The application for a post office showed some indecision on the part of residents. Two town names were crossed out before they settled on Artesian City. Image courtesy of Bob Omberg who has the best collection of information about Idaho post offices that I know of.

Imagine how settlers must have felt when they heard about water bubbling out of the desert all by itself in seemingly endless quantities. Bonus: The water came springing out of the earth at 110 degrees like a gift from God.

Artesian City came into existence because of two wells that James E. Bower drilled on the Cassia-Twin Falls county line a couple of miles south of Murtaugh Lake in 1895. Bower watered his cattle with the wells for a while, but he thought they might be an attractant for farmers whose crops might benefit from warm water.

By 1909, Bower had enticed a couple dozen families to purchase property from him. And, indeed, the crops seemed to respond well to warm water. Potatoes faired particularly well. Cattle seemed to do better drinking all the warm winter water they wanted. A couple of cattlemen from California moved 5,000 head into the area. The claim was that feeding alfalfa to cows that had access to warm water was worth about $1 a ton in feeding value.

Artesian City popped up with a general store, school, hotel, a couple of dance halls, a livery stable, a post office and a cemetery. The post office operated just a couple of years, from 1909 to 1911. The cemetery is still… operating.

In 1910, developers brought a sanatorium to Artesian City “for the cure of the ailments of humanity,” according to an Idaho Statesman article at the time. The project included a 40-room hotel with each room offering a bathtub in which one could soak privately in hot water. The water contained “Sulphur, iron, and magnesia in quantities that render it valuable in the eradication of many diseases of the human family.”

The sanatorium lasted into the 40s. The wells were capped after that. Some say drilling for irrigation water in the area has since killed the artesian effect.

One footnote worth mentioning is that James Bower, who dreamed of providing warm water to crops, played another role in Idaho history. He was the ranch foreman who hired “Diamondfield” Jack Davis. More important, he was one of the men who confessed to the murder of a pair of sheepherders that Davis had been convicted of killing. That confession freed “Diamondfield” Jack and seemed to have done Bower no discernable harm.

The two artesian wells drilled by James Bower in 1895 bubbled up ten feet high.

The two artesian wells drilled by James Bower in 1895 bubbled up ten feet high.  The sanatorium at Artesian City.

The sanatorium at Artesian City. The application for a post office showed some indecision on the part of residents. Two town names were crossed out before they settled on Artesian City. Image courtesy of Bob Omberg who has the best collection of information about Idaho post offices that I know of.

The application for a post office showed some indecision on the part of residents. Two town names were crossed out before they settled on Artesian City. Image courtesy of Bob Omberg who has the best collection of information about Idaho post offices that I know of.

Published on December 21, 2020 04:00

December 20, 2020

Reporting All the News

Newspapers valiantly try to report the most important news of the day. This happens even when that news might ultimately be detrimental to the newspaper.

In 1996 I noticed that newspapers were infatuated with the Internet (then capitalized). Anything about this newfangled invention made the paper. I had just written my first novel, Keeping Private Idaho. As a promotional, dare I say “stunt,” I put it out on the internet as the first serialized novel to appear there. It didn’t get much notice on the worldwide web, but it got me a front-page story in the Idaho Statesman.

So, there was a newspaper publicizing what could have—but thankfully has not yet—led to its demise.

The Statesman was equally eager to promote the modern invention of radio. They happily printed everything about the new stations as they came on the air, giving them ample free advertising. The stations did eventually start buying a lot of advertising, too.

Recently I ran across a perfect example of this infatuation with a medium that was challenging the supremacy of newspapers.

On the 6th of February, 1936, the Idaho Statesman reported than Douglas Van Vlack, a “bushy-haired Tacoman,” was convicted of murdering his former wife. That story may be worth telling another time, but what caught my attention was this paragraph:

“Immediately after The Statesman received the Associated Press flash that Van Vlack had been found guilty the news was phoned to radio station KIDO and the verdict was on the air only a few seconds later.”

So nice of them. They clearly didn’t view a radio station as competition at that point.

The next paragraph underlined the timely utility of radio broadcasting by telling readers another way The Statesman got the word out.

“The first printed word of the verdict was also given out by The Statesman in the form of bulletins pasted on windows in the downtown district. The first bulletin was off the press within two minutes after the first flash.”

That broadcasting was at the dawning of new age that would forever change the media landscape might not have sunk in. Similarly, the Statesman and other papers have reported on the widespread reach of television, the internet, Twitter, Facebook, Tik Tok, et al. In 1936 they could not have imagined that those bulletins they pasted to the window would one day be sent to the smartphones of readers as even newspapers embraced digital technology.

In 1996 I noticed that newspapers were infatuated with the Internet (then capitalized). Anything about this newfangled invention made the paper. I had just written my first novel, Keeping Private Idaho. As a promotional, dare I say “stunt,” I put it out on the internet as the first serialized novel to appear there. It didn’t get much notice on the worldwide web, but it got me a front-page story in the Idaho Statesman.

So, there was a newspaper publicizing what could have—but thankfully has not yet—led to its demise.

The Statesman was equally eager to promote the modern invention of radio. They happily printed everything about the new stations as they came on the air, giving them ample free advertising. The stations did eventually start buying a lot of advertising, too.

Recently I ran across a perfect example of this infatuation with a medium that was challenging the supremacy of newspapers.

On the 6th of February, 1936, the Idaho Statesman reported than Douglas Van Vlack, a “bushy-haired Tacoman,” was convicted of murdering his former wife. That story may be worth telling another time, but what caught my attention was this paragraph:

“Immediately after The Statesman received the Associated Press flash that Van Vlack had been found guilty the news was phoned to radio station KIDO and the verdict was on the air only a few seconds later.”

So nice of them. They clearly didn’t view a radio station as competition at that point.

The next paragraph underlined the timely utility of radio broadcasting by telling readers another way The Statesman got the word out.

“The first printed word of the verdict was also given out by The Statesman in the form of bulletins pasted on windows in the downtown district. The first bulletin was off the press within two minutes after the first flash.”

That broadcasting was at the dawning of new age that would forever change the media landscape might not have sunk in. Similarly, the Statesman and other papers have reported on the widespread reach of television, the internet, Twitter, Facebook, Tik Tok, et al. In 1936 they could not have imagined that those bulletins they pasted to the window would one day be sent to the smartphones of readers as even newspapers embraced digital technology.

Published on December 20, 2020 04:00