Rick Just's Blog, page 139

January 8, 2021

Another NW Passage Connection

We’ve done stories before about the movie Northwest Passage, filmed near McCall at what is now the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. The location where the film was shot is the obvious Idaho connection. There is another link to Idaho that you may not know about.

Talbot Jennings, the screenwriter for the film, was born in Shoshone, Idaho in 1894. He attended high school in Nampa and, after serving in World War I, attended the University of Idaho. There he edited the yearbook and an English department publication before graduating Phi Betta Kapa in 1924. He got a master’s degree from Harvard and attended the Yale Drama School.

Jennings is best known for his screenplay for the 1935 movie Mutiny on the Bounty. He wrote or co-wrote 17 in all, receiving two Oscar nominations. His last screenplay was The Sons of Katie Elder, which came out in 1965.

Talbot Jennings died in 1985 at age 90.

Talbot Jennings, the screenwriter for the film, was born in Shoshone, Idaho in 1894. He attended high school in Nampa and, after serving in World War I, attended the University of Idaho. There he edited the yearbook and an English department publication before graduating Phi Betta Kapa in 1924. He got a master’s degree from Harvard and attended the Yale Drama School.

Jennings is best known for his screenplay for the 1935 movie Mutiny on the Bounty. He wrote or co-wrote 17 in all, receiving two Oscar nominations. His last screenplay was The Sons of Katie Elder, which came out in 1965.

Talbot Jennings died in 1985 at age 90.

Published on January 08, 2021 04:00

January 7, 2021

When the Stars Came Out (Sort of) in Boise

February 20, 1940 was a much-anticipated date in Boise. That evening would be the world premiere of a major motion picture at the Pinney Theater.

The movie was Northwest Passage, filmed around McCall, particularly in what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. It starred some big-name actors, Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey.

Based on a popular novel of the same name by Kenneth Roberts, Northwest Passage was called an “epic” picture and “Hollywood’s Greatest Adventure Drama” in headlines leading up to the premiere. Roberts was billed as “America’s foremost historical novelist.”

Filming the movie had certainly been an epic adventure for the citizens of McCall. It was shot over two summer seasons. Some 900 locals worked as extras and at other jobs related to filming. The production set up shop on 50 acres bordering Payette Lake. Twelve freight cars brought in dozens of Indian drums, sugar kettles, gun racks, weaving frames, rush bottom chairs, spinning wheels, leather bellows, anvils, and 1,000 cannon balls. It was a virtual traveling museum including antique desks, tables and chests, pelts of every North American mammal worth mentioning, candlesticks, mahogany buckets, brass clocks, and on and on.

A blacksmith shop was built to look like it originated in 1750 for some of the movie scenes, and it was used to forge nails for the buildings the crew would set up. Every effort was made to assure the props looked like the real thing. Indian items were designed using tribal markings of the Abenakia (the setting for the movie was in Maine). For verisimilitude the 700 scalps hung from poles on the set were made with human hair, though the “scalps” were made of rubber.

The green buckskin uniforms Rogers’ Rangers wore in the movie seemed totally wrong to people used to brown or buttery yellow buckskin. In the book, Roberts had specified that they wore green buckskin, so MGM went with that, though it was a constant headache to keep the costumes dyed evenly.

This was to be two-time Academy Award-winner Spencer Tracy’s greatest role, playing Major Rogers, of Rogers’ Rangers. Legendary director King Vidor directed. So, the speculation in Boise was, who would show up for the premiere?

On January 10, Pinney Theater Manager J.R. Mendenhall announced that Robert Young would attend, along with others yet to be named. Also, yet to be named were the members of the local committee set up to plan the festivities surrounding the premiere. Governor C.A. Bottolfsen didn’t waste any time, naming Idahoans from Boise, Caldwell, Nampa, Weiser, Payette, and Emmett to the committee, with state Senator Carl E. Brown of McCall to head it. Brown, along with the McCall Chamber of Commerce and the Idaho Timber Protective Association had been instrumental in bringing the production to Payette Lake.

As the date approached there was continued speculation in The Idaho Statesman about who would attend. Would King Vidor be there? Tracy? Brennan? Young? There was also speculation about what reserved seats at the Pinney would cost, this during a time when a ticket to the movies was typically 15 cents. MGM, suggested $2.50 would be about right. The Pinney settled on $1.10, and assured those who might be outraged at the price that the film would stick around for at least a couple of weeks at regular prices.

Meanwhile, the Governor’s committee charged ahead with planning. The stars, whomever they were, would be greeted at the Boise Depot at 7:23 am by committee members and Mayor James L. Straight. Then, it was off to the Owyhee hotel for a breakfast to be attended by the committee members and their wives (no women were on the committee) and the stars. After breakfast the stars would be escorted (by the committee) to the governor’s office. All Idaho mayors were invited to be on hand for that meet and greet. Then, at 12:15 a public luncheon starring the stars would be sponsored by the Boise Chamber of Commerce, with tickets available to the masses. At 2 pm there would be a parade featuring high school students—participants in a costume contest—dressed in clothing as depicted in the movie. Along the way merchants were expected to have appropriate displays.

That evening, a radio broadcast would air from 8 until 8:30 outside the theater, around which would be Hollywood props and spotlights. Then, practically as an afterthought, they would show the film. The stars would catch the 11:20 out of town.

So, when the big day came, who of the Who’s Who showed up? Stars. Maybe none you’ve ever heard of, but it was still a big deal to welcome Ilona Massey, Virginia Grey, Alan Curtis, Isabel Jewell, and Nat Pendelton, luminaries all, to town. The crowd that came to see them was reportedly so enthusiastic that Boise’s new fire engine had to be called to rescue the actors, which was totally not a planned event. Certainly unplanned was the trampling of several cars when the star-struck climbed on hoods and roofs the better to capture a bit of stardust. And, as if to justify the firetruck, one of the klieg lights caught a tree branch on fire.

For those on tenterhooks, Shirley Weisgerber won the costume contest. Meanwhile, Spencer Tracy sent a telegram to the governor expressing his regrets for being unable to attend due to his “continued employment in Hollywood on Edison the Man.”

There was to be a sequel to Northwest Passage, but the studio never got around to making it. The movie won the Academy Award for best cinematography in 1941, in spite of the glowing green costumes.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

The movie was Northwest Passage, filmed around McCall, particularly in what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. It starred some big-name actors, Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey.

Based on a popular novel of the same name by Kenneth Roberts, Northwest Passage was called an “epic” picture and “Hollywood’s Greatest Adventure Drama” in headlines leading up to the premiere. Roberts was billed as “America’s foremost historical novelist.”

Filming the movie had certainly been an epic adventure for the citizens of McCall. It was shot over two summer seasons. Some 900 locals worked as extras and at other jobs related to filming. The production set up shop on 50 acres bordering Payette Lake. Twelve freight cars brought in dozens of Indian drums, sugar kettles, gun racks, weaving frames, rush bottom chairs, spinning wheels, leather bellows, anvils, and 1,000 cannon balls. It was a virtual traveling museum including antique desks, tables and chests, pelts of every North American mammal worth mentioning, candlesticks, mahogany buckets, brass clocks, and on and on.

A blacksmith shop was built to look like it originated in 1750 for some of the movie scenes, and it was used to forge nails for the buildings the crew would set up. Every effort was made to assure the props looked like the real thing. Indian items were designed using tribal markings of the Abenakia (the setting for the movie was in Maine). For verisimilitude the 700 scalps hung from poles on the set were made with human hair, though the “scalps” were made of rubber.

The green buckskin uniforms Rogers’ Rangers wore in the movie seemed totally wrong to people used to brown or buttery yellow buckskin. In the book, Roberts had specified that they wore green buckskin, so MGM went with that, though it was a constant headache to keep the costumes dyed evenly.

This was to be two-time Academy Award-winner Spencer Tracy’s greatest role, playing Major Rogers, of Rogers’ Rangers. Legendary director King Vidor directed. So, the speculation in Boise was, who would show up for the premiere?

On January 10, Pinney Theater Manager J.R. Mendenhall announced that Robert Young would attend, along with others yet to be named. Also, yet to be named were the members of the local committee set up to plan the festivities surrounding the premiere. Governor C.A. Bottolfsen didn’t waste any time, naming Idahoans from Boise, Caldwell, Nampa, Weiser, Payette, and Emmett to the committee, with state Senator Carl E. Brown of McCall to head it. Brown, along with the McCall Chamber of Commerce and the Idaho Timber Protective Association had been instrumental in bringing the production to Payette Lake.

As the date approached there was continued speculation in The Idaho Statesman about who would attend. Would King Vidor be there? Tracy? Brennan? Young? There was also speculation about what reserved seats at the Pinney would cost, this during a time when a ticket to the movies was typically 15 cents. MGM, suggested $2.50 would be about right. The Pinney settled on $1.10, and assured those who might be outraged at the price that the film would stick around for at least a couple of weeks at regular prices.

Meanwhile, the Governor’s committee charged ahead with planning. The stars, whomever they were, would be greeted at the Boise Depot at 7:23 am by committee members and Mayor James L. Straight. Then, it was off to the Owyhee hotel for a breakfast to be attended by the committee members and their wives (no women were on the committee) and the stars. After breakfast the stars would be escorted (by the committee) to the governor’s office. All Idaho mayors were invited to be on hand for that meet and greet. Then, at 12:15 a public luncheon starring the stars would be sponsored by the Boise Chamber of Commerce, with tickets available to the masses. At 2 pm there would be a parade featuring high school students—participants in a costume contest—dressed in clothing as depicted in the movie. Along the way merchants were expected to have appropriate displays.

That evening, a radio broadcast would air from 8 until 8:30 outside the theater, around which would be Hollywood props and spotlights. Then, practically as an afterthought, they would show the film. The stars would catch the 11:20 out of town.

So, when the big day came, who of the Who’s Who showed up? Stars. Maybe none you’ve ever heard of, but it was still a big deal to welcome Ilona Massey, Virginia Grey, Alan Curtis, Isabel Jewell, and Nat Pendelton, luminaries all, to town. The crowd that came to see them was reportedly so enthusiastic that Boise’s new fire engine had to be called to rescue the actors, which was totally not a planned event. Certainly unplanned was the trampling of several cars when the star-struck climbed on hoods and roofs the better to capture a bit of stardust. And, as if to justify the firetruck, one of the klieg lights caught a tree branch on fire.

For those on tenterhooks, Shirley Weisgerber won the costume contest. Meanwhile, Spencer Tracy sent a telegram to the governor expressing his regrets for being unable to attend due to his “continued employment in Hollywood on Edison the Man.”

There was to be a sequel to Northwest Passage, but the studio never got around to making it. The movie won the Academy Award for best cinematography in 1941, in spite of the glowing green costumes.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

Published on January 07, 2021 04:00

January 6, 2021

Everyone Could Have a Job

In 1864, Idaho was barely a territory. One writer for the Idaho Statesman noticed that many people were coming through Boise on their way to Oregon Territory, often without stopping.

In the August 20, 1864 editorial the writer lamented that people seemed to give up on Boise too soon. “A man can seldom see a chance to make money or start in business the first or second day he stops in a new place.”

The writer noted that “Most of the available land along the river is claimed, but there are many thousands of acres lying back that are not claimed which need only a moderate outlay of labor and capital to make as productive as could be desired.”

It would be a couple more decades before canal projects made many of those thousand acres bloom. Still, there was plenty of opportunity in the valley.

The editorial expressed an almost unlimited need for laborers. “You cannot stay in this town three days without finding something to do, and our word for it, you will ever after that have more on your hands than you can do.” Not every profession was needed, though. The editorial concluded with this: “If you want to practice law or physic, don’t stop, for we have more than enough of both. If you want to get into office and dabble in politics, for Heaven’s sake move on to some other country. We have a large population of that sort that we would be glad to export.”

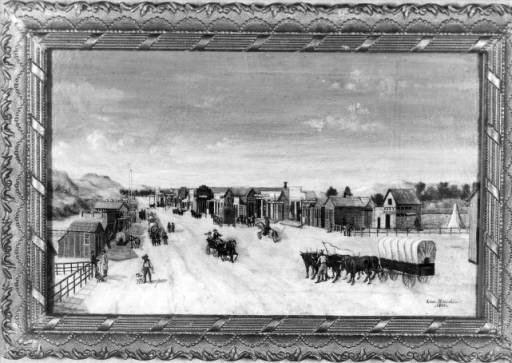

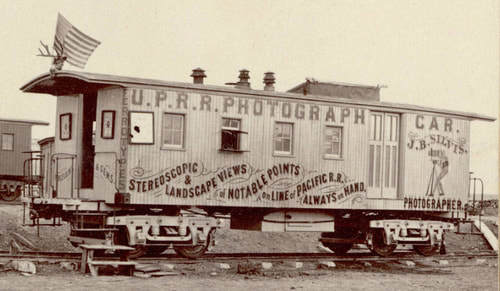

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

In the August 20, 1864 editorial the writer lamented that people seemed to give up on Boise too soon. “A man can seldom see a chance to make money or start in business the first or second day he stops in a new place.”

The writer noted that “Most of the available land along the river is claimed, but there are many thousands of acres lying back that are not claimed which need only a moderate outlay of labor and capital to make as productive as could be desired.”

It would be a couple more decades before canal projects made many of those thousand acres bloom. Still, there was plenty of opportunity in the valley.

The editorial expressed an almost unlimited need for laborers. “You cannot stay in this town three days without finding something to do, and our word for it, you will ever after that have more on your hands than you can do.” Not every profession was needed, though. The editorial concluded with this: “If you want to practice law or physic, don’t stop, for we have more than enough of both. If you want to get into office and dabble in politics, for Heaven’s sake move on to some other country. We have a large population of that sort that we would be glad to export.”

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on January 06, 2021 04:00

January 5, 2021

Dead Horse Cave

Idaho has its fair share of caves. I’ve written about 40 Horse Cave, Aviator Cave, Wilson Butte Cave, and others. Today’s story spotlights an annual gathering in a place called Dead Horse Cave, sometimes Jericho Dead Horse Cave.

A 1966 headline in the Twin Falls Times news called Dead Horse Cave, “Probably (the) World’s Biggest Hall.” If that seems an odd way to describe a cave, blame the Odd Fellows. The Independent Order of Oddfellows (IOOF) held meetings there annually, beginning at least as far back as the 1930s. They “improved” the cave with entrance stairs and concrete benches along the sides of the main room, which is 40 feet below the surface. It’s big enough to hold 300 Odd Fellows, according to various clips about their meetings. They don’t seem to be meeting there anymore, but did so into the late 60s.

The cave is named for its propensity to swallow up wild horses. The opening is more or less in the roof of the lava tube, meaning it was an unexpected hole in the ground when horses galloped across the desert. The bones of equines piled up on the floor of the cave leading to an obvious name.

Dead Horse cave is about 11 miles northwest of Gooding. Ask around or check with the Twin Falls Chamber of Commerce. It is well known locally. A visit in the heat of summer is recommended, since the air in the cave hovers around 56 degrees year-round. The steps into Dead Horse Cave.

The steps into Dead Horse Cave.

A 1966 headline in the Twin Falls Times news called Dead Horse Cave, “Probably (the) World’s Biggest Hall.” If that seems an odd way to describe a cave, blame the Odd Fellows. The Independent Order of Oddfellows (IOOF) held meetings there annually, beginning at least as far back as the 1930s. They “improved” the cave with entrance stairs and concrete benches along the sides of the main room, which is 40 feet below the surface. It’s big enough to hold 300 Odd Fellows, according to various clips about their meetings. They don’t seem to be meeting there anymore, but did so into the late 60s.

The cave is named for its propensity to swallow up wild horses. The opening is more or less in the roof of the lava tube, meaning it was an unexpected hole in the ground when horses galloped across the desert. The bones of equines piled up on the floor of the cave leading to an obvious name.

Dead Horse cave is about 11 miles northwest of Gooding. Ask around or check with the Twin Falls Chamber of Commerce. It is well known locally. A visit in the heat of summer is recommended, since the air in the cave hovers around 56 degrees year-round.

The steps into Dead Horse Cave.

The steps into Dead Horse Cave.

Published on January 05, 2021 04:00

January 4, 2021

Misspellings in Idaho History

Things get misspelled all the time. If you don’t believe that, you’re clearly not on Facebook. I’ve begun collecting a few misspellings that have affected Idaho history. I hope that readers will share some things they’ve noticed, such as:

Hagerman

Shoshoni Indians traditionally wintered here and speared salmon at Lower Salmon Falls. It became a stage station on the Oregon Trail and eventually had enough residents that a couple of men applied for a post office. The men were Stanley Hegeman (or Hageman—I’ve seen it both ways) and Jack Hess. They wanted to call the place Hess, but postal officials nixed it because there was already a Hess, Idaho. There isn’t one now, and I’ve found no information about where Hess was. Someone will probably come to my rescue.

Naturally, since Hess was taken, they tried for Hageman (or Hegeman). Postal officials blessed that one, but misspelled the name as Hagerman, perhaps because of poor penmanship on the part of the applicants.

Potatoe

You remember Dan Quayle, right? He was the vice president who infamously corrected the spelling of Idaho’s famous tuber as “potatoe” in front of a group of kids on June 15, 1992. That moment is preserved for… as long as potatoes can be preserved, at the Idaho Potato Museum in Blackfoot. A California DJ asked Quayle to autograph a potato for him, all in good fun. Somehow the museum ended up with it.

Cariboo

Caribou County is named for Jesse “Cariboo Jack” Fairchild who was, in turn, nicknamed such because he had taken part in the gold rush in the Cariboo region of British Columbia in 1860. There are a lot of things around Soda Springs named after Cariboo Jack, including the ghost town of Caribou City, and the Caribou Mountains. Fairchild was born in Canada. What isn’t exactly clear is why the Cariboo region of British Columbia is spelled that way. Canadians don’t generally spell caribou differently. In any case Jack’s nickname became Caribou when it was attached to various sites in Caribou County, the last county created in Idaho.

Kansas

This one is outrageous. The Treaty of Fort Bridger was, among other things, meant to preserve the right of the Bannock Tribe to harvest camas bulbs on Camas Prairie near present-day Fairfield. Unfortunately, Camas Prairie was written as Kansas Prairie in the treaty. Using that flimsy excuse white settlers let their cattle and hogs trample and root around the traditional Bannock gathering site, devastating the camas fields, and leading to the Bannock War of 1878.

Spelling matters, kids.

Hagerman

Shoshoni Indians traditionally wintered here and speared salmon at Lower Salmon Falls. It became a stage station on the Oregon Trail and eventually had enough residents that a couple of men applied for a post office. The men were Stanley Hegeman (or Hageman—I’ve seen it both ways) and Jack Hess. They wanted to call the place Hess, but postal officials nixed it because there was already a Hess, Idaho. There isn’t one now, and I’ve found no information about where Hess was. Someone will probably come to my rescue.

Naturally, since Hess was taken, they tried for Hageman (or Hegeman). Postal officials blessed that one, but misspelled the name as Hagerman, perhaps because of poor penmanship on the part of the applicants.

Potatoe

You remember Dan Quayle, right? He was the vice president who infamously corrected the spelling of Idaho’s famous tuber as “potatoe” in front of a group of kids on June 15, 1992. That moment is preserved for… as long as potatoes can be preserved, at the Idaho Potato Museum in Blackfoot. A California DJ asked Quayle to autograph a potato for him, all in good fun. Somehow the museum ended up with it.

Cariboo

Caribou County is named for Jesse “Cariboo Jack” Fairchild who was, in turn, nicknamed such because he had taken part in the gold rush in the Cariboo region of British Columbia in 1860. There are a lot of things around Soda Springs named after Cariboo Jack, including the ghost town of Caribou City, and the Caribou Mountains. Fairchild was born in Canada. What isn’t exactly clear is why the Cariboo region of British Columbia is spelled that way. Canadians don’t generally spell caribou differently. In any case Jack’s nickname became Caribou when it was attached to various sites in Caribou County, the last county created in Idaho.

Kansas

This one is outrageous. The Treaty of Fort Bridger was, among other things, meant to preserve the right of the Bannock Tribe to harvest camas bulbs on Camas Prairie near present-day Fairfield. Unfortunately, Camas Prairie was written as Kansas Prairie in the treaty. Using that flimsy excuse white settlers let their cattle and hogs trample and root around the traditional Bannock gathering site, devastating the camas fields, and leading to the Bannock War of 1878.

Spelling matters, kids.

Published on January 04, 2021 04:00

January 3, 2021

Putting out the Paper

In the 1870s it was often a challenge for the staff of the Idaho Statesman and the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman to get the paper out. First, someone had to be found to turn the press. The single cylinder Acme press was hand operated, often by a Chinese laborer. If someone could not be found to crank the machine, it fell to the staff. Everyone from the editor on down took their turn at the wheel to keep the press running.

It was not always labor that was in short supply. The paper to feed through the press was brought in by freight teams from Kelton, Utah. Except when it wasn’t. If the newsprint failed to show, there was a scramble to find anything that would take ink. Butcher paper and grocery store paper sometimes filled in for the real thing.

The tri-weekly version of the paper had a circulation of about 1200 copies, and the weekly ran about 800 copies. That was a lot of folding. In those early days the newspapers had to be folded by hand by everyone in the office.

Charles Payton, who worked for the Statesman in the 1870s, reminisced about the early days in the December 15, 1918 edition of the paper. He remembered an irate subscriber that burst into the office one day. Payton had gotten a little ahead of the game by writing the man’s obituary. The man was on death’s door, so the paper printed it. Apparently the reportedly dead subscriber had decided not to knock on the door of death. Instead he stopped by to complain vehemently that his demise had been prematurely printed in the paper. Mark Twain, it is said, had a similar experience.

It was not always labor that was in short supply. The paper to feed through the press was brought in by freight teams from Kelton, Utah. Except when it wasn’t. If the newsprint failed to show, there was a scramble to find anything that would take ink. Butcher paper and grocery store paper sometimes filled in for the real thing.

The tri-weekly version of the paper had a circulation of about 1200 copies, and the weekly ran about 800 copies. That was a lot of folding. In those early days the newspapers had to be folded by hand by everyone in the office.

Charles Payton, who worked for the Statesman in the 1870s, reminisced about the early days in the December 15, 1918 edition of the paper. He remembered an irate subscriber that burst into the office one day. Payton had gotten a little ahead of the game by writing the man’s obituary. The man was on death’s door, so the paper printed it. Apparently the reportedly dead subscriber had decided not to knock on the door of death. Instead he stopped by to complain vehemently that his demise had been prematurely printed in the paper. Mark Twain, it is said, had a similar experience.

Published on January 03, 2021 04:00

January 2, 2021

The Union Pacific Photo Car

I ran across a photo in a family album from the 1880s that intrigued me. It wasn’t the subject of the picture; I don’t even know who the kid is. What caught my interest was the cardboard photo frame surrounding the portrait.

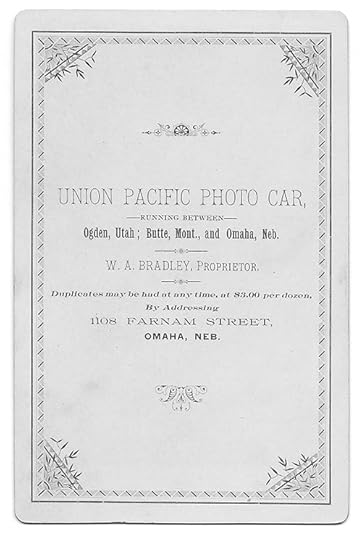

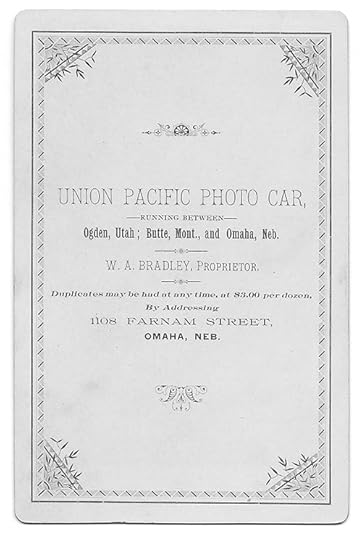

The photo below was taken by W.A. Bradley and labeled “Union Pacific Photo Car.” The back of the photo (below, below) had a bit more information about the photo car and its route.

I found that the photographer who came up with the idea of building a rail car dedicated to photography was John B. Silvis, a miner who had given up that pursuit to try his luck at something that used the silver he hadn’t had much luck finding.

He had tried his hand at ranching but ended up as a partner in a Salt Lake City photo studio in 1867. The partnership was dissolving about the time they hammered home the golden spike at Promontory, Utah in 1869. Silvis missed taking that famous picture, but he did start taking photos up and down the railroad line as commerce caused a growth spurt.

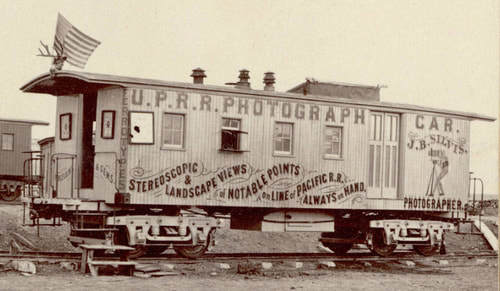

The details of how he got hold of an old caboose and what his exact relationship with the railroad was are unclear. We know only that he turned the caboose into a photography studio, a darkroom, living quarters, and an office where he could conduct business. Then, he began to catch trains to various points around the West where he would park on a sidetrack and advertise his services to the local community.

I found several clips from the Ketchum Keystone in 1883 advertising Silvis’ services. “The U.P. car will remain there (Hailey) till after the Fourth. This affords all desiring pictures an opportunity to procure them.”

In 1885, the Wood River Times announced that the car was back and under new management. That may have been when Charles Tate took over the car from Silvis, who had retired.

In August of 1888, the Blackfoot News announced that the Union Pacific photograph car was in town and would remain as long as “work lasts.” By then, William A. Bradley was operating the rolling studio. That may have been when the photo of the unidentified toddler below was taken.

The photo car continued to operate for a year or two before disappearing. Others copied the idea, but the original caboose built by Silvis was said to be the best, and there still exist several photos of the photo car.

Unidentified infant from a Just family photo album.

Unidentified infant from a Just family photo album.

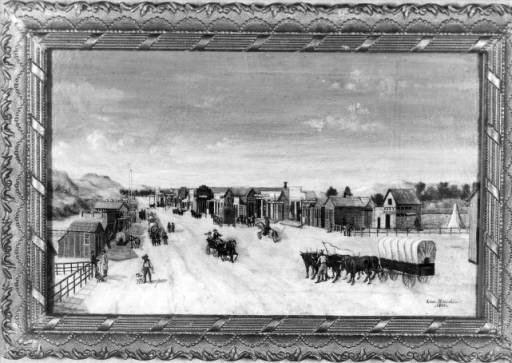

The back of the above photo frame.

The back of the above photo frame.  The Union Pacific Photo Car parked on a siding. Note the deer skull and antlers on the front.

The Union Pacific Photo Car parked on a siding. Note the deer skull and antlers on the front.

This was taken when Silvis still owned it.

The photo below was taken by W.A. Bradley and labeled “Union Pacific Photo Car.” The back of the photo (below, below) had a bit more information about the photo car and its route.

I found that the photographer who came up with the idea of building a rail car dedicated to photography was John B. Silvis, a miner who had given up that pursuit to try his luck at something that used the silver he hadn’t had much luck finding.

He had tried his hand at ranching but ended up as a partner in a Salt Lake City photo studio in 1867. The partnership was dissolving about the time they hammered home the golden spike at Promontory, Utah in 1869. Silvis missed taking that famous picture, but he did start taking photos up and down the railroad line as commerce caused a growth spurt.

The details of how he got hold of an old caboose and what his exact relationship with the railroad was are unclear. We know only that he turned the caboose into a photography studio, a darkroom, living quarters, and an office where he could conduct business. Then, he began to catch trains to various points around the West where he would park on a sidetrack and advertise his services to the local community.

I found several clips from the Ketchum Keystone in 1883 advertising Silvis’ services. “The U.P. car will remain there (Hailey) till after the Fourth. This affords all desiring pictures an opportunity to procure them.”

In 1885, the Wood River Times announced that the car was back and under new management. That may have been when Charles Tate took over the car from Silvis, who had retired.

In August of 1888, the Blackfoot News announced that the Union Pacific photograph car was in town and would remain as long as “work lasts.” By then, William A. Bradley was operating the rolling studio. That may have been when the photo of the unidentified toddler below was taken.

The photo car continued to operate for a year or two before disappearing. Others copied the idea, but the original caboose built by Silvis was said to be the best, and there still exist several photos of the photo car.

Unidentified infant from a Just family photo album.

Unidentified infant from a Just family photo album. The back of the above photo frame.

The back of the above photo frame.  The Union Pacific Photo Car parked on a siding. Note the deer skull and antlers on the front.

The Union Pacific Photo Car parked on a siding. Note the deer skull and antlers on the front. This was taken when Silvis still owned it.

Published on January 02, 2021 04:00

January 1, 2021

Fifty Years Hence

In 1921, the folks at the Idaho Statesman were feeling optimistic. They devoted a page and half to how grand Boise would be “Fifty Years Hence.” The article was full of “Predictions, based on scientific calculations and (the) law of averages.”

We’re a hundred years “hence,” so let’s see how well the prognosticators—various leading citizens—did.

Architect J.A. Fennel predicted hourly air service by 1971. That was probably correct. Some of his vision sounds familiar today. “The visitor will observe from his cab window a beautiful residential section festooning the hills, with wonderful winding driveways.” We can only wish his next prediction had come true. “The absence of parked automobiles from the streets will be accounted for by the fact that under-the-street garages or storage spaces have been provided.”

W.H.P. Hill, secretary of the Boise Chamber of Commerce expected 300,000 people to be living in Boise by 1971. It was closer to 75,000. Stay tuned, though. We aren’t far from Hill’s mark today. The chamber exec pointed out that Boise had the first tourist park for automobiles, and that he expected the future to bring an “Aero Tourist park with its perfect landing fields and accommodations for hundreds of flying machines and thousands of passengers.”

J.P. Congdon envisioned flying into Boise and seeing that “Both banks of the river have been very prettily parked and there are miles and miles of good driveways in them. Checks have been placed in the river to provide boating and bathing facilities.” He came the closest to guessing the 1971 population of Boise: 100,000.

Dora Thompson, the supervisor of schools in Boise, expected “well-proportioned business edifices, free from all advertising matter, and elegant in their simplicity of line and decoration.” She also predicted “Noiseless electric trains running without track or third rail.” She envisioned a magical device that would free the air from “noisome odors and flecks of begriming soot, for all the smoke of the city will be consumed in a municipally owned plant operated for that purpose.”

One prediction Ms. Thompson made had a sting it: “Boise will not be true to her name ‘wooded’ 50 years hence, however, if a city forester is not appointed in the near future, since trees are being cut ruthlessly and new ones are not being planted systematically.”

Perhaps the elected officials of the city heeded her call. Today we have a city forester and the nickname City of Trees.

What would you predict “50 years hence?”

We’re a hundred years “hence,” so let’s see how well the prognosticators—various leading citizens—did.

Architect J.A. Fennel predicted hourly air service by 1971. That was probably correct. Some of his vision sounds familiar today. “The visitor will observe from his cab window a beautiful residential section festooning the hills, with wonderful winding driveways.” We can only wish his next prediction had come true. “The absence of parked automobiles from the streets will be accounted for by the fact that under-the-street garages or storage spaces have been provided.”

W.H.P. Hill, secretary of the Boise Chamber of Commerce expected 300,000 people to be living in Boise by 1971. It was closer to 75,000. Stay tuned, though. We aren’t far from Hill’s mark today. The chamber exec pointed out that Boise had the first tourist park for automobiles, and that he expected the future to bring an “Aero Tourist park with its perfect landing fields and accommodations for hundreds of flying machines and thousands of passengers.”

J.P. Congdon envisioned flying into Boise and seeing that “Both banks of the river have been very prettily parked and there are miles and miles of good driveways in them. Checks have been placed in the river to provide boating and bathing facilities.” He came the closest to guessing the 1971 population of Boise: 100,000.

Dora Thompson, the supervisor of schools in Boise, expected “well-proportioned business edifices, free from all advertising matter, and elegant in their simplicity of line and decoration.” She also predicted “Noiseless electric trains running without track or third rail.” She envisioned a magical device that would free the air from “noisome odors and flecks of begriming soot, for all the smoke of the city will be consumed in a municipally owned plant operated for that purpose.”

One prediction Ms. Thompson made had a sting it: “Boise will not be true to her name ‘wooded’ 50 years hence, however, if a city forester is not appointed in the near future, since trees are being cut ruthlessly and new ones are not being planted systematically.”

Perhaps the elected officials of the city heeded her call. Today we have a city forester and the nickname City of Trees.

What would you predict “50 years hence?”

Published on January 01, 2021 04:00

December 31, 2020

Pop Quiz!

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture. If you missed that story, click the letter for a link.

1). What did Teddy Roosevelt give Beaver Dick’s daughter, besides a spanking?

A. A horse.

B. An autographed picture.

C. A rifle.

D. A plug of chewing tobacco.

E. A beaded belt.

2). What is the official name of the glacier on Mt. Borah?

A. Otto Glacier.

B. Borah Glacier.

C. 25-Acre Glacier.

D. Aurora Borah Alice.

E. It doesn’t have an official name.

3). Which of these jobs did Clarence Bottolfsen NOT hold?

A. Printer’s Devil.

B. Newspaper Editor.

C. U.S. Senator.

D. Idaho Governor.

E. Idaho State Senator.

4). What happened to all those Stinker Station signs?

A. The Highway Beautification Act of 1965 made them illegal.

B. The company switched to television advertising in the late 50s.

C. The BLM made Fearless Farris remove them from federal property.

D. When the chain of stations was sold the new company took them down.

E. Offended motorists complained so much that “Fearless” Farris took them down.

5) What is a printer’s devil?

A. A three-pronged instrument used to handle hot type.

B. The gutter space between columns.

C. A typesetting case.

D. An apprentice in a newspaper.

E. A specially-shaped spatula for applying ink to rollers.

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

1, C

2, E

3, C

4, A

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). What did Teddy Roosevelt give Beaver Dick’s daughter, besides a spanking?

A. A horse.

B. An autographed picture.

C. A rifle.

D. A plug of chewing tobacco.

E. A beaded belt.

2). What is the official name of the glacier on Mt. Borah?

A. Otto Glacier.

B. Borah Glacier.

C. 25-Acre Glacier.

D. Aurora Borah Alice.

E. It doesn’t have an official name.

3). Which of these jobs did Clarence Bottolfsen NOT hold?

A. Printer’s Devil.

B. Newspaper Editor.

C. U.S. Senator.

D. Idaho Governor.

E. Idaho State Senator.

4). What happened to all those Stinker Station signs?

A. The Highway Beautification Act of 1965 made them illegal.

B. The company switched to television advertising in the late 50s.

C. The BLM made Fearless Farris remove them from federal property.

D. When the chain of stations was sold the new company took them down.

E. Offended motorists complained so much that “Fearless” Farris took them down.

5) What is a printer’s devil?

A. A three-pronged instrument used to handle hot type.

B. The gutter space between columns.

C. A typesetting case.

D. An apprentice in a newspaper.

E. A specially-shaped spatula for applying ink to rollers.

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)1, C

2, E

3, C

4, A

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on December 31, 2020 04:00

December 30, 2020

D. Boon 1776

Daniel Boone was a celebrated frontiersman, back when the frontier included parts of Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Kentucky. He first gained fame during the American Revolution when he and a group of men recaptured three girls, one Boone’s daughter, from an Indian war party recruited by the British. James Fenimore Cooper wrote a fictionalized version of the event in Last of the Mohicans.

That was in 1776. Why do we in Idaho care? Because his well-documented exploits at that time seem to have placed him some 1,800 miles away from Idaho, not somewhere on the Continental Divide carving his misspelled name into an aspen tree.

In 1976 an Idaho Falls woman named Louise Rutledge became intrigued by an inscription on an aspen tree that said, “D. Boon 1776.” The carving was old. Well, maybe not 1776 old, but certainly not as new as 1976. Rutledge wrote a little book called D. Boon 1776 A Western Bicentennial Mystery. According to the Sunday, August 10, 1976 edition of the Idaho Statesman she “began extensive research to prove—or disprove—that frontiersman Daniel Boone was, in fact, in Idaho 30 years ahead of Lewis and Clark.”

Rutledge became convinced that Boone had carved his initials into the tree, not in spite of, but because of the absence of the “e” at the end of his name. She had grown up in the Cumberland Gap area of Tennessee which was awash in tales about “Boon trees.” She was certain that because of the misspelling, this carving was genuine. There were many “Boon trees” scattered around the south, often with the added information that D. Boon had cilled or kilt or killed a bar, bar being the way a genuine frontiersman would spell bear. We can’t know how many or if any of those carvings are genuine, but we do know that when signing or printing his name, Danielle Boone always knew how to spell it.

Not ready to leave a good story untold, Rutledge and her husband, Gene, and Bonita Pendleton, all of Idaho Falls, wrote a play speculating on Boone’s journey to Idaho, called D. Boone 1776, War Has Two Sides.

Tree experts later determined the carving on the Idaho Aspen had been done in about 1895. Undeterred, Rutledge postulated that someone had seen the original, genuine D. Boon tree, and noticed that it was dead. To preserve the history for posterity, they made a copy.

Well, it’s a theory.

Clipping from the August 3, 1976 Post Register.

Clipping from the August 3, 1976 Post Register.

That was in 1776. Why do we in Idaho care? Because his well-documented exploits at that time seem to have placed him some 1,800 miles away from Idaho, not somewhere on the Continental Divide carving his misspelled name into an aspen tree.

In 1976 an Idaho Falls woman named Louise Rutledge became intrigued by an inscription on an aspen tree that said, “D. Boon 1776.” The carving was old. Well, maybe not 1776 old, but certainly not as new as 1976. Rutledge wrote a little book called D. Boon 1776 A Western Bicentennial Mystery. According to the Sunday, August 10, 1976 edition of the Idaho Statesman she “began extensive research to prove—or disprove—that frontiersman Daniel Boone was, in fact, in Idaho 30 years ahead of Lewis and Clark.”

Rutledge became convinced that Boone had carved his initials into the tree, not in spite of, but because of the absence of the “e” at the end of his name. She had grown up in the Cumberland Gap area of Tennessee which was awash in tales about “Boon trees.” She was certain that because of the misspelling, this carving was genuine. There were many “Boon trees” scattered around the south, often with the added information that D. Boon had cilled or kilt or killed a bar, bar being the way a genuine frontiersman would spell bear. We can’t know how many or if any of those carvings are genuine, but we do know that when signing or printing his name, Danielle Boone always knew how to spell it.

Not ready to leave a good story untold, Rutledge and her husband, Gene, and Bonita Pendleton, all of Idaho Falls, wrote a play speculating on Boone’s journey to Idaho, called D. Boone 1776, War Has Two Sides.

Tree experts later determined the carving on the Idaho Aspen had been done in about 1895. Undeterred, Rutledge postulated that someone had seen the original, genuine D. Boon tree, and noticed that it was dead. To preserve the history for posterity, they made a copy.

Well, it’s a theory.

Clipping from the August 3, 1976 Post Register.

Clipping from the August 3, 1976 Post Register.

Published on December 30, 2020 04:00