Rick Just's Blog, page 137

January 28, 2021

A Plate Sticker Caper

Did I tell you how much I love potatoes? Love ‘em. Not so much on my license plates, though. So, in the late 1980s my brother, Kent Just, and I set out to give Idahoans a choice. I located the company that made the reflective material used on the license plates at that time and learned that you could buy it in strips. I ordered a roll of the stuff and had slogans printed on it in the same size, font, and color as the slogan on the license plates. Buyers could peel off the paper on the back and stick the new slogan over “Famous Potatoes.” We sold them for a couple of bucks through Stinker Stations. You could pick from “Famous Potholes,” “The Whitewater State,” and several others.

Kent acted as the front man on this project, because I was working for the State of Idaho at the time and was a little unsure about how my employer would take this little prank. We got publicity for the project in papers from Washington State to Washington DC. Some of the articles made it sound like we had a factory cranking these out by the thousands. I had a roll of stickers and a pair of scissors.

Encouraging people to put an unauthorized sticker on a license plate ruffled the feathers of the folks over at Idaho State Police HQ. They made noises about it sufficient enough to convince us to stop selling them. We were certain we were on solid legal ground because the US Supreme Court had already ruled that it was legal to cover up a license plate slogan in the name of free speech (New Hampshire’s “Live Free or Die”). Still, it didn’t seem worthwhile to hire a lawyer for a $150 joke. We’d had our fun, and we’d already made our money back.

Kent passed away in 2017. I know he wouldn’t mind my adding this little footnote to a footnote in Idaho history. I can hear his way-too-loud laugh right now.

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Kent acted as the front man on this project, because I was working for the State of Idaho at the time and was a little unsure about how my employer would take this little prank. We got publicity for the project in papers from Washington State to Washington DC. Some of the articles made it sound like we had a factory cranking these out by the thousands. I had a roll of stickers and a pair of scissors.

Encouraging people to put an unauthorized sticker on a license plate ruffled the feathers of the folks over at Idaho State Police HQ. They made noises about it sufficient enough to convince us to stop selling them. We were certain we were on solid legal ground because the US Supreme Court had already ruled that it was legal to cover up a license plate slogan in the name of free speech (New Hampshire’s “Live Free or Die”). Still, it didn’t seem worthwhile to hire a lawyer for a $150 joke. We’d had our fun, and we’d already made our money back.

Kent passed away in 2017. I know he wouldn’t mind my adding this little footnote to a footnote in Idaho history. I can hear his way-too-loud laugh right now.

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Published on January 28, 2021 04:00

January 27, 2021

Famous Potato Plates

As much as we love potatoes, some of us in Idaho are less enthused about the “Famous Potatoes” slogan that appears on the bottom of state license plates. We are hesitant to grace our Tesla or our pickup with that little snippet of free advertising that is jealously guarded by the Idaho Potato Commission. I am, perhaps, on the top of that anti-slogan heap. More on that in tomorrow’s post. Today, a little history.

Potatoes first showed up on Idaho plates in 1928. The elongated spud took up practically the whole plate. Idahoans hated it because, 1). They didn’t care to be a rolling advertisement for tubers, and 2). Tourists stole them for souvenirs. Newspapers editorialized against them. A couple of editorial headlines read, “Our Licenses Should Not Be Billboards,” “Tasty Indeed—But Hard to Read.”

The Idaho Secretary of State’s office was flooded with request to promote other products on the Gem State’s plates. After a year of complaints, the state went back to plain numbers in 1929.

Idaho’s 1928 spud plate is often credited with being the first advertising plate in the nation. If so, it shares that distinction with Massachusetts. They put a small cod on their plates in 28 and 29, dropping the fish probably because it began to smell.

In Idaho, potatoes did not go away. In 1947 a legislator from Bonneville County proposed putting a picture of a potato on the plates permanently. Wisely—if I may use that term in reference to the Idaho Legislature—they placated him with a two-year trial. The slogan on the bottom of the plates in 48 and 49 was “World Famous Potatoes.” In case that was too subtle for you, the silver plates featured a large, full-color baked potato sticker slapped on in the middle of the plate.

The decals cost only 4 cents each, but extra expense was incurred when officials found out the decal wouldn’t hold up unless the aluminum-colored plates got an extra coat of shellack.

The 1948 plates marked another milestone in Idaho’s license plate history. That was the year prisoners at the Idaho State Penitentiary began manufacturing them. The warden of the prison had a little fun with Governor C.A. Robbins when they concocted a press event to introduce the potato plates. They had dummied up a plate with a decal of a “curveful woman” in the center instead of a potato.

“My gosh, governor, we made a mistake and stamped out 20,000 plates with the design of this woman on it instead of the Idaho potato!” said the warden. That correspondence course in comedy really paid off.

Dare I say “predictably” residents hated the real potato plate? The baked potato with a pat of butter on top looked like a large goose dropping from a car length back.

Helen Miller, a Democratic representative from Glenns Ferry was quoted in the Idaho Statesman saying, “We give thanks the potato mutilation will only be a two-year period and not a permanent nuisance.” She went on to say, “If the next legislature favors the continuation of the practice to mutilate the license plate for advertising purposes and the identification lettering is kicked around, the highway patrol eventually will be using binoculars to identify the smaller lettering.”

The 1950 plate was potato-free.

But those rolling mini signs were just too tempting to leave to just letters and numbers. The slogan World Famous Potatoes came back in 1953, sans potato, disappeared in ’54 and ’55, and came back in ’56. In 1957 “World” was dropped from the slogan, making it “Famous Potatoes.” That’s the slogan that has stuck ever since, though you can buy your way out of it by getting a personalized or specialty plate.

There was another way to get out of displaying the Famous Potatoes slogan on your Idaho license plates back in the 1980s. That story tomorrow.

The first advertising plate featured an elongated potato in 1928. These can bring $250 today from collectors.

The first advertising plate featured an elongated potato in 1928. These can bring $250 today from collectors.  The 1948 plate with a 1949 tag.

The 1948 plate with a 1949 tag.

Potatoes first showed up on Idaho plates in 1928. The elongated spud took up practically the whole plate. Idahoans hated it because, 1). They didn’t care to be a rolling advertisement for tubers, and 2). Tourists stole them for souvenirs. Newspapers editorialized against them. A couple of editorial headlines read, “Our Licenses Should Not Be Billboards,” “Tasty Indeed—But Hard to Read.”

The Idaho Secretary of State’s office was flooded with request to promote other products on the Gem State’s plates. After a year of complaints, the state went back to plain numbers in 1929.

Idaho’s 1928 spud plate is often credited with being the first advertising plate in the nation. If so, it shares that distinction with Massachusetts. They put a small cod on their plates in 28 and 29, dropping the fish probably because it began to smell.

In Idaho, potatoes did not go away. In 1947 a legislator from Bonneville County proposed putting a picture of a potato on the plates permanently. Wisely—if I may use that term in reference to the Idaho Legislature—they placated him with a two-year trial. The slogan on the bottom of the plates in 48 and 49 was “World Famous Potatoes.” In case that was too subtle for you, the silver plates featured a large, full-color baked potato sticker slapped on in the middle of the plate.

The decals cost only 4 cents each, but extra expense was incurred when officials found out the decal wouldn’t hold up unless the aluminum-colored plates got an extra coat of shellack.

The 1948 plates marked another milestone in Idaho’s license plate history. That was the year prisoners at the Idaho State Penitentiary began manufacturing them. The warden of the prison had a little fun with Governor C.A. Robbins when they concocted a press event to introduce the potato plates. They had dummied up a plate with a decal of a “curveful woman” in the center instead of a potato.

“My gosh, governor, we made a mistake and stamped out 20,000 plates with the design of this woman on it instead of the Idaho potato!” said the warden. That correspondence course in comedy really paid off.

Dare I say “predictably” residents hated the real potato plate? The baked potato with a pat of butter on top looked like a large goose dropping from a car length back.

Helen Miller, a Democratic representative from Glenns Ferry was quoted in the Idaho Statesman saying, “We give thanks the potato mutilation will only be a two-year period and not a permanent nuisance.” She went on to say, “If the next legislature favors the continuation of the practice to mutilate the license plate for advertising purposes and the identification lettering is kicked around, the highway patrol eventually will be using binoculars to identify the smaller lettering.”

The 1950 plate was potato-free.

But those rolling mini signs were just too tempting to leave to just letters and numbers. The slogan World Famous Potatoes came back in 1953, sans potato, disappeared in ’54 and ’55, and came back in ’56. In 1957 “World” was dropped from the slogan, making it “Famous Potatoes.” That’s the slogan that has stuck ever since, though you can buy your way out of it by getting a personalized or specialty plate.

There was another way to get out of displaying the Famous Potatoes slogan on your Idaho license plates back in the 1980s. That story tomorrow.

The first advertising plate featured an elongated potato in 1928. These can bring $250 today from collectors.

The first advertising plate featured an elongated potato in 1928. These can bring $250 today from collectors.  The 1948 plate with a 1949 tag.

The 1948 plate with a 1949 tag.

Published on January 27, 2021 04:00

January 26, 2021

How many Idaho State Parks are there?

One of the most common questions I get is, how many state parks are there in Idaho? Right now, 30 with an asterisk.

Idaho has always had a hard time defining the term state park. For decades one meaning was something like: any land owned by the state of Idaho that invited citizens to use it. That included rest areas and roadside stops that happened to have a picnic table. As a result, state parks were managed at various times by the Idaho Department of Transportation, Public Works, and the Idaho Department of Lands. It wasn’t until 1965 that a dedicated state parks agency was formed.

Today’s “30” state parks include at least one you’ve never heard of and is difficult to visit and one that isn’t actually managed as a state park anymore.

Mowry State Park, on Lake Coeur d’Alene, became a state park in 1972 when the Mowry family made a partial donation of the property to the state. It’s the one you’ve probably never heard of. The property is on two small peninsulas with a beautiful beach between the two. The problem is that the state doesn’t own the beach. It hoped to acquire it but was unsuccessful. That left one peninsula that is too high about the water and too small to be of much use, and another peninsula that can be reached only by boat. That one, called Gasser Point, is managed as a boat-in picnic site by Kootenai County Parks and Waterways.

Veterans Memorial State Park opened in 1982. The Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (IDPR) turned management of the site over to Boise Parks and Recreation in 1997. It’s still listed as a state park in statute, and is still owned by the State of Idaho, but is rarely mentioned by the agency.

Another thing that makes counting state parks confusing is local usage. Many people call Malad Gorge, Billingsley Creek, Box Canyon, Ritter Island, and Niagara Springs state parks. IDPR calls them “units” of Thousand Springs State Park.

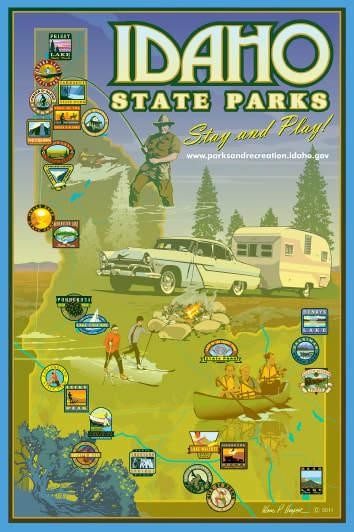

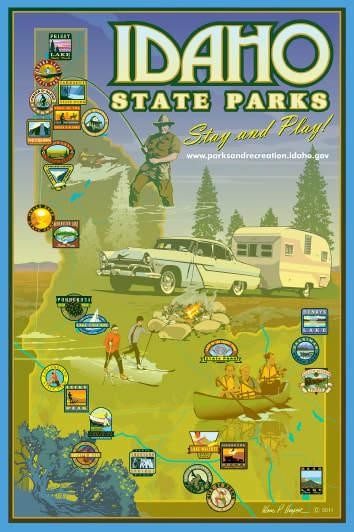

Even the nifty IDPR poster, below, created by Boise artist Ward Hooper shows only 27 state parks, which is off from the “official” count of 30 in statute. Why? Well, they didn’t bother creating a logo for Mowry or Veterans because see above. And—I’m just speculating here—they didn’t order a logo for Glade Creek State Park because of the nature of the place. Glade Creek, on Lolo Pass, was where Lewis and Clark first made camp in what would become Idaho. IDPR manages the site as a natural area and doesn’t encourage use other than brief visits to the interpretive overlook. So, you do the math!

Idaho has always had a hard time defining the term state park. For decades one meaning was something like: any land owned by the state of Idaho that invited citizens to use it. That included rest areas and roadside stops that happened to have a picnic table. As a result, state parks were managed at various times by the Idaho Department of Transportation, Public Works, and the Idaho Department of Lands. It wasn’t until 1965 that a dedicated state parks agency was formed.

Today’s “30” state parks include at least one you’ve never heard of and is difficult to visit and one that isn’t actually managed as a state park anymore.

Mowry State Park, on Lake Coeur d’Alene, became a state park in 1972 when the Mowry family made a partial donation of the property to the state. It’s the one you’ve probably never heard of. The property is on two small peninsulas with a beautiful beach between the two. The problem is that the state doesn’t own the beach. It hoped to acquire it but was unsuccessful. That left one peninsula that is too high about the water and too small to be of much use, and another peninsula that can be reached only by boat. That one, called Gasser Point, is managed as a boat-in picnic site by Kootenai County Parks and Waterways.

Veterans Memorial State Park opened in 1982. The Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (IDPR) turned management of the site over to Boise Parks and Recreation in 1997. It’s still listed as a state park in statute, and is still owned by the State of Idaho, but is rarely mentioned by the agency.

Another thing that makes counting state parks confusing is local usage. Many people call Malad Gorge, Billingsley Creek, Box Canyon, Ritter Island, and Niagara Springs state parks. IDPR calls them “units” of Thousand Springs State Park.

Even the nifty IDPR poster, below, created by Boise artist Ward Hooper shows only 27 state parks, which is off from the “official” count of 30 in statute. Why? Well, they didn’t bother creating a logo for Mowry or Veterans because see above. And—I’m just speculating here—they didn’t order a logo for Glade Creek State Park because of the nature of the place. Glade Creek, on Lolo Pass, was where Lewis and Clark first made camp in what would become Idaho. IDPR manages the site as a natural area and doesn’t encourage use other than brief visits to the interpretive overlook. So, you do the math!

Published on January 26, 2021 04:00

January 25, 2021

Boise's Mini-Me Skyscraper

The Hoff Building in Boise, once known as the Hotel Boise, is considered the city’s first skyscraper. Designed by Boise architects Tourtellotte & Hummell, it was built in 1930.

The big skyscraper spawned a smaller skyscraper, in a way. Across the parking lot from the Hoff Building, on the corner of 8th and Jefferson, stands a miniature skyscraper. It is 25 feet tall, measures about four feet wide at the base, and weighs five tons.

Many have noticed a resemblance to New York’s Empire State Building, which was built about the same time as the Hotel Boise. That’s likely because both the statue and the famous building in New York City have the telltale bold vertical lines and stepped back design of the art deco style of architecture. So did the Hotel Boise, now the Hoff Building.

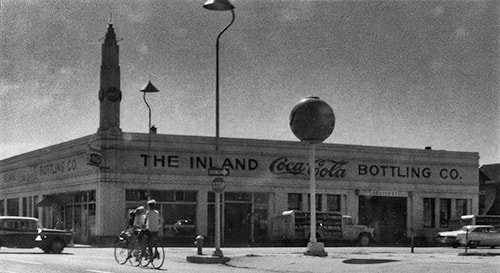

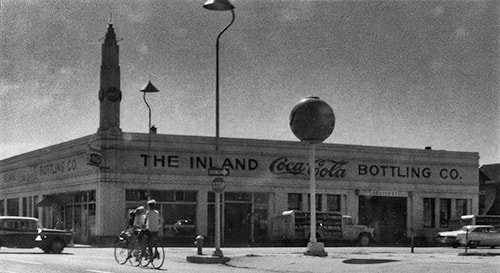

The little—if anything that weighs five tons can be called little—skyscraper is one of Boise’s earliest public art installations. It’s called Inland Spire. It was placed kitty corner from Idaho’s statehouse during a major refurbishment of the Hoff Building in 1979. Before that, it stood on the corner of the roof of the Inland Coca-Cola Bottling Company building at 12th and Idaho.

On the Coke building the spire boasted round red and white coke emblems on each side and neon tubing on the top in Coca-Cola colors. It was something of a landmark, but the building was ready for demolition in 1979 when Phil Murelaga got the idea of moving the spire to the Hoff Building site as a way of emphasizing its art deco elements. Murelaga was one of the building’s owners.

John Bertram, who was working with Planmakers to replace some of the missing art deco elements of the building, thought moving the spire onto the site was a great idea. He had been spending months studying art deco buildings around the Northwest and chasing down elements that matched that style for the renovation. They were able to rebuild the exterior marques from the original building plans. Bertram chased down art deco reproduction lights for the first floor interior and found bronze and glass exterior lights for the entrances in New York City. Other art deco touches included a large clock dial for the lobby and floor identification symbols on each floor by the original elevator.

Taller skyscrapers now add to Boise’s skyline. The Hoff Building, at 165 feet, is overshadowed by the Zion’s Bank building, the tallest in Idaho at 323 feet. Only one of Boise’s downtown buildings, though, has a mini-skyscraper as part of its heritage.

The Inland Spire concrete sculpture at the corner of 8th and Jefferson in Boise shares art deco features with the Hoff Building on the same property.

The Inland Spire concrete sculpture at the corner of 8th and Jefferson in Boise shares art deco features with the Hoff Building on the same property.  The skyscraper-like spire once perched on the corner of the Inland Coca-Cola Bottling Company building at 12th and Idaho. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.

The skyscraper-like spire once perched on the corner of the Inland Coca-Cola Bottling Company building at 12th and Idaho. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.

The big skyscraper spawned a smaller skyscraper, in a way. Across the parking lot from the Hoff Building, on the corner of 8th and Jefferson, stands a miniature skyscraper. It is 25 feet tall, measures about four feet wide at the base, and weighs five tons.

Many have noticed a resemblance to New York’s Empire State Building, which was built about the same time as the Hotel Boise. That’s likely because both the statue and the famous building in New York City have the telltale bold vertical lines and stepped back design of the art deco style of architecture. So did the Hotel Boise, now the Hoff Building.

The little—if anything that weighs five tons can be called little—skyscraper is one of Boise’s earliest public art installations. It’s called Inland Spire. It was placed kitty corner from Idaho’s statehouse during a major refurbishment of the Hoff Building in 1979. Before that, it stood on the corner of the roof of the Inland Coca-Cola Bottling Company building at 12th and Idaho.

On the Coke building the spire boasted round red and white coke emblems on each side and neon tubing on the top in Coca-Cola colors. It was something of a landmark, but the building was ready for demolition in 1979 when Phil Murelaga got the idea of moving the spire to the Hoff Building site as a way of emphasizing its art deco elements. Murelaga was one of the building’s owners.

John Bertram, who was working with Planmakers to replace some of the missing art deco elements of the building, thought moving the spire onto the site was a great idea. He had been spending months studying art deco buildings around the Northwest and chasing down elements that matched that style for the renovation. They were able to rebuild the exterior marques from the original building plans. Bertram chased down art deco reproduction lights for the first floor interior and found bronze and glass exterior lights for the entrances in New York City. Other art deco touches included a large clock dial for the lobby and floor identification symbols on each floor by the original elevator.

Taller skyscrapers now add to Boise’s skyline. The Hoff Building, at 165 feet, is overshadowed by the Zion’s Bank building, the tallest in Idaho at 323 feet. Only one of Boise’s downtown buildings, though, has a mini-skyscraper as part of its heritage.

The Inland Spire concrete sculpture at the corner of 8th and Jefferson in Boise shares art deco features with the Hoff Building on the same property.

The Inland Spire concrete sculpture at the corner of 8th and Jefferson in Boise shares art deco features with the Hoff Building on the same property.  The skyscraper-like spire once perched on the corner of the Inland Coca-Cola Bottling Company building at 12th and Idaho. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.

The skyscraper-like spire once perched on the corner of the Inland Coca-Cola Bottling Company building at 12th and Idaho. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.

Published on January 25, 2021 05:09

January 24, 2021

Coyote

If you raise sheep, it's almost a foregone conclusion that you aren't a fan of coyotes. Arguments rage over just how many sheep coyotes kill each year in Idaho, but the predators do enjoy an occasional lamb chop.

Coyotes aren't picky eaters. They consume mostly small rodents and rabbits, but they seldom turn up their nose at any meal, animal or vegetable. They would love to eat what your dog eats.

Coyotes are a lot like dogs. They're intelligent. They bark like dogs, and they look a lot like Bowser and ol' Blue, although a coyote's nose is pointier than most dogs, and his tail bushier. They are related closely enough to cross breed with domestic dogs.

When they run--at speeds up to 40 miles per hour--coyotes hold their tail down between their hind legs. They share that almost unique trait with only one other dog-like creature, the red wolf.

Coyotes are typically shy, nocturnal creatures. You're more likely to hear them than see them. They seem to love singing to the moon. What would a Western movie be without the sound of coyotes? If you hear one of those moon songs you can try singing back to a coyote. They will often answer your call.

Native Americans greatly admired coyotes. A common character in their stories, Coyote sometimes plays the part of a man, sometimes an animal, and sometimes a god. The creation story of the Nez Perce involves Coyote tricking a monster into swallowing him. Coyote frees all the animals the monster had swallowed and cuts up its parts to form many tribes saving the heart of the monster for the creation of the Nez Perce.

You can see the Heart of the Monster near Kamiah, Idaho, where the National Park Service retells that Coyote story.

Heart of the Monster, with a ghostly coyote in the foreground.

Heart of the Monster, with a ghostly coyote in the foreground.

Coyotes aren't picky eaters. They consume mostly small rodents and rabbits, but they seldom turn up their nose at any meal, animal or vegetable. They would love to eat what your dog eats.

Coyotes are a lot like dogs. They're intelligent. They bark like dogs, and they look a lot like Bowser and ol' Blue, although a coyote's nose is pointier than most dogs, and his tail bushier. They are related closely enough to cross breed with domestic dogs.

When they run--at speeds up to 40 miles per hour--coyotes hold their tail down between their hind legs. They share that almost unique trait with only one other dog-like creature, the red wolf.

Coyotes are typically shy, nocturnal creatures. You're more likely to hear them than see them. They seem to love singing to the moon. What would a Western movie be without the sound of coyotes? If you hear one of those moon songs you can try singing back to a coyote. They will often answer your call.

Native Americans greatly admired coyotes. A common character in their stories, Coyote sometimes plays the part of a man, sometimes an animal, and sometimes a god. The creation story of the Nez Perce involves Coyote tricking a monster into swallowing him. Coyote frees all the animals the monster had swallowed and cuts up its parts to form many tribes saving the heart of the monster for the creation of the Nez Perce.

You can see the Heart of the Monster near Kamiah, Idaho, where the National Park Service retells that Coyote story.

Heart of the Monster, with a ghostly coyote in the foreground.

Heart of the Monster, with a ghostly coyote in the foreground.

Published on January 24, 2021 04:00

January 23, 2021

A Message from Space

In July 1969, much of the world’s attention was on the moon. At that same time, more than 34,000 scouts were attending the National Boy Scout Jamboree at Farragut State Park in Idaho. Astronaut Col. Frank Borman delivered a message from President Nixon on the closing night of the jamboree and presented a film from Neil Armstrong’s first step on the moon which had occurred a few days before. Only a handful of Scouts had seen the televised event, so the entire crowd sat spellbound, watching the scene from the moon and hearing Armstrong’s words. Both Borman and Armstrong were former Scouts.

Armstrong acknowledged the Scouts from space on his way to the moon, saying “Hello to my fellow scouts and scouters at Farragut National Park in Idaho.” No one bothered to tell Commander Armstrong that it was actually a state park.

Armstrong acknowledged the Scouts from space on his way to the moon, saying “Hello to my fellow scouts and scouters at Farragut National Park in Idaho.” No one bothered to tell Commander Armstrong that it was actually a state park.

Published on January 23, 2021 04:00

January 22, 2021

Ethel Redfield

I was reading the Pupil’s Workbook in the Geography of Idaho one recent rainy Sunday, as one does. That workbook was published in 1924. Among its amazing facts and statistics was a comparison of the number of horses in Idaho at the time—284,000—with the number of registered automobiles in the state—54,577.

It might surprise you to learn that the number of horses has stayed fairly steady, with about 220,000 in the state in 2016, compared with a plague of automobiles—more that 600,000.

The workbook was “prepared and arranged” by Ethel E. Redfield, a former superintendent of public instruction in Idaho.

It seemed a little unusual to me for a Superintendent of Education to write a textbook, so I decided to see what her story was.

Ethel Redfield was born April 22, 1877 at Kamiah on the Nez Perce Reservation. She went to college in Portland, getting a BA from Albany College (later renamed Lewis and Clark College) in 1897, then earning a BS the next year from the same school. Redfield started her career at a one-room school in Detroit, Oregon. She soon returned to Idaho as the head of the Latin Department at Lewiston High School from 1906 to 1913, then served as the Nez Perce County Superintendent of Schools for 1906 to 1917.

Redfield ran for Idaho Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1917. Her platform, more or less, was that she wanted the office eliminated.

A new plan for organizing education in Idaho had been developed. Under that plan the office of superintendent of public instruction would be abolished. She ran under the assumption that the legislature would do away with the office in the next session, placing the duties of the position under the secretary of the state board of education.

Redfield won the office. A bill to eliminate it was killed in the Idaho senate, so she chose to serve in the position voters had handed her. She apparently did a good job. The next time elections rolled around, Redfield, a Republican, won easily. She was popular enough that in Canyon County she was nominated as a Democrat and as a Republican during the primary. She beat her Democratic opponent in the primary in that county.

Redfield served three terms as the head of Idaho’s schools, then began a string of jobs in education beginning as the state high school inspector, 1923-34; executive secretary of the State Board of Education, 1924-25; and the State Commissioner of Education, 1925-27. In her spare time, she taught summer school at Idaho State College and received an MS in Education there in 1925. She did additional graduate work at Stanford and Harvard and wrote the above-mentioned text.

In 1928, she began teaching full time at Idaho State College and stayed there until her retirement in 1947. Redfield’s alma mater, Lewis and Clark College in Portland, awarded her an honorary doctorate in 1955. Dr. Redfield, who passed away in 1957, has been called the “Dean of public education in Idaho.”

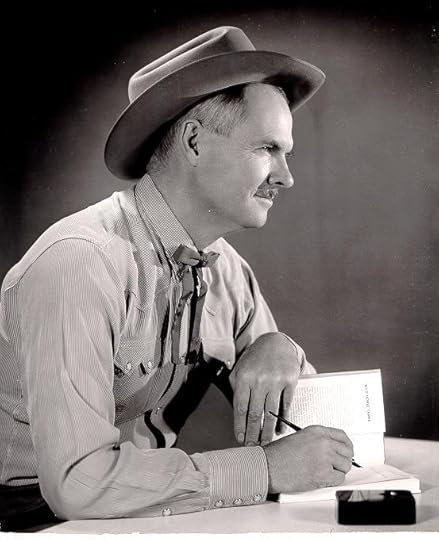

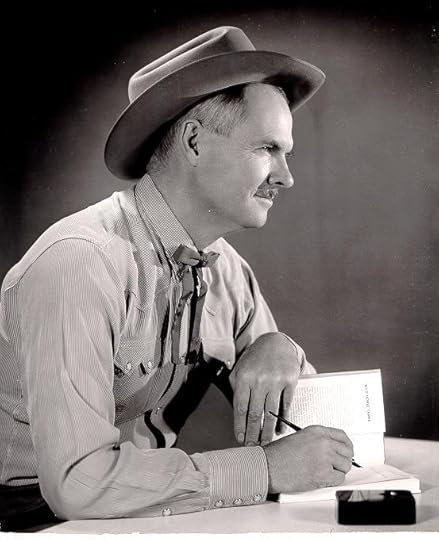

Thanks to Bud Cornelison for sending me the pupil’s workbook that started me off on this quest. Ethel Redfield in 1925. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Ethel Redfield in 1925. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

It might surprise you to learn that the number of horses has stayed fairly steady, with about 220,000 in the state in 2016, compared with a plague of automobiles—more that 600,000.

The workbook was “prepared and arranged” by Ethel E. Redfield, a former superintendent of public instruction in Idaho.

It seemed a little unusual to me for a Superintendent of Education to write a textbook, so I decided to see what her story was.

Ethel Redfield was born April 22, 1877 at Kamiah on the Nez Perce Reservation. She went to college in Portland, getting a BA from Albany College (later renamed Lewis and Clark College) in 1897, then earning a BS the next year from the same school. Redfield started her career at a one-room school in Detroit, Oregon. She soon returned to Idaho as the head of the Latin Department at Lewiston High School from 1906 to 1913, then served as the Nez Perce County Superintendent of Schools for 1906 to 1917.

Redfield ran for Idaho Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1917. Her platform, more or less, was that she wanted the office eliminated.

A new plan for organizing education in Idaho had been developed. Under that plan the office of superintendent of public instruction would be abolished. She ran under the assumption that the legislature would do away with the office in the next session, placing the duties of the position under the secretary of the state board of education.

Redfield won the office. A bill to eliminate it was killed in the Idaho senate, so she chose to serve in the position voters had handed her. She apparently did a good job. The next time elections rolled around, Redfield, a Republican, won easily. She was popular enough that in Canyon County she was nominated as a Democrat and as a Republican during the primary. She beat her Democratic opponent in the primary in that county.

Redfield served three terms as the head of Idaho’s schools, then began a string of jobs in education beginning as the state high school inspector, 1923-34; executive secretary of the State Board of Education, 1924-25; and the State Commissioner of Education, 1925-27. In her spare time, she taught summer school at Idaho State College and received an MS in Education there in 1925. She did additional graduate work at Stanford and Harvard and wrote the above-mentioned text.

In 1928, she began teaching full time at Idaho State College and stayed there until her retirement in 1947. Redfield’s alma mater, Lewis and Clark College in Portland, awarded her an honorary doctorate in 1955. Dr. Redfield, who passed away in 1957, has been called the “Dean of public education in Idaho.”

Thanks to Bud Cornelison for sending me the pupil’s workbook that started me off on this quest.

Ethel Redfield in 1925. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Ethel Redfield in 1925. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on January 22, 2021 04:00

January 21, 2021

Please Don’t Eat the Beavers

Trappers were most interested in beavers for their pelts. Once a beaver is liberated of its fur, though, another opportunity presents itself to man not too squeamish to eat a rodent. Beaver tail is considered a delicacy by some, and we’re not referring to the Canadian pastry of the same name which is shaped like a beaver tail.

All this is by way of giving you a little history on Malad. The river. Okay, both rivers. Idaho is blessed with two Malad rivers, one in Oneida County, the county seat of which—and only town of any size—is Malad City. The other is the Malad River in Gooding County. That one runs through Malad Gorge, the spectacular canyon where the river tumbles into Devil’s Washbowl right below the I-84 bridge near Tuttle. You can see the gorge while traveling on the interstate for 1.35 seconds if you happen to look south while going 80 miles per hour. Next time you drive by, don’t. Stop for a few minutes at Malad Gorge State Park. Walk across the gorge on the scary but safe footbridge and gaze down at the Malad River 250 feet below. Just don’t eat the beavers.

Ah yes, the beavers. Early trappers working for the Pacific Fur Company, called Astorians after company owner John Jacob Astor, encountered the river and its tasty beaver in 1811. That’s when Donald Mackenzie led them on an exploratory jaunt after the Wilson Price Hunt expedition met disaster in the rapids of the Snake River at Caldron Linn.

Long story short: They ate beaver and got sick. Mackenzie named the river Malad or Malade, which means “sick” in French.

Much speculation has ensued in the centuries following the illness the men experienced as to its cause. Had the beaver eaten some poisonous root? Had selenium concentrated in the fat of the beaver tails? No one knows.

By the way, the naming of Idaho’s other Malad River has a similar story with different players. The lesson here might be to stick to the Canadian pastry if you insist on adding beaver tails to your diet.

Malad Gorge.

Malad Gorge.

All this is by way of giving you a little history on Malad. The river. Okay, both rivers. Idaho is blessed with two Malad rivers, one in Oneida County, the county seat of which—and only town of any size—is Malad City. The other is the Malad River in Gooding County. That one runs through Malad Gorge, the spectacular canyon where the river tumbles into Devil’s Washbowl right below the I-84 bridge near Tuttle. You can see the gorge while traveling on the interstate for 1.35 seconds if you happen to look south while going 80 miles per hour. Next time you drive by, don’t. Stop for a few minutes at Malad Gorge State Park. Walk across the gorge on the scary but safe footbridge and gaze down at the Malad River 250 feet below. Just don’t eat the beavers.

Ah yes, the beavers. Early trappers working for the Pacific Fur Company, called Astorians after company owner John Jacob Astor, encountered the river and its tasty beaver in 1811. That’s when Donald Mackenzie led them on an exploratory jaunt after the Wilson Price Hunt expedition met disaster in the rapids of the Snake River at Caldron Linn.

Long story short: They ate beaver and got sick. Mackenzie named the river Malad or Malade, which means “sick” in French.

Much speculation has ensued in the centuries following the illness the men experienced as to its cause. Had the beaver eaten some poisonous root? Had selenium concentrated in the fat of the beaver tails? No one knows.

By the way, the naming of Idaho’s other Malad River has a similar story with different players. The lesson here might be to stick to the Canadian pastry if you insist on adding beaver tails to your diet.

Malad Gorge.

Malad Gorge.

Published on January 21, 2021 04:00

January 20, 2021

Glenn Balch

When you're about ten years old there’s nothing better than curling up with a novel and stepping into the old time West with a story about a noble horse or a faithful dog. An Idaho man provided many of those perfect moments for kids.

Glenn Balch grew up in Texas. He came to Idaho to fight fires in in 1924 when he was 21 years. He wrote for the Idaho Statesman for several years, worked as an assistant to U.S. Senator John Thomas for a while, then served as a pilot in the U.S. Army-Air Force. During World War II, he flew over 100 hours in combat over enemy territory. In 1963, he retired as an army colonel.

Now, all that's an interesting life, but there was much more to the life of Glenn Balch. He also found time to write 35 books.

Balch wrote his first book, Riders of the Rio Grande, while snowbound at Pettit Lake in the Sawtooths. It was published in 1935. His books about animals and the wild West were favorites with juvenile readers, and he received many awards for them.

One of his best-known books, called Indian Paint, was made into a movie starring Johnny Crawford. His books have been translated into many foreign languages. One Glenn Balch novel, a dog story titled White Ruff, sold over a million copies, and the horse story Tiger Roan, has been reprinted 19 times.

In September, 1989 at the age of 86, Glenn Balch died as the result of a car accident. The Boise author brought a lot of pleasure to generations of young readers. His books are largely out of print today.

Glenn Balch grew up in Texas. He came to Idaho to fight fires in in 1924 when he was 21 years. He wrote for the Idaho Statesman for several years, worked as an assistant to U.S. Senator John Thomas for a while, then served as a pilot in the U.S. Army-Air Force. During World War II, he flew over 100 hours in combat over enemy territory. In 1963, he retired as an army colonel.

Now, all that's an interesting life, but there was much more to the life of Glenn Balch. He also found time to write 35 books.

Balch wrote his first book, Riders of the Rio Grande, while snowbound at Pettit Lake in the Sawtooths. It was published in 1935. His books about animals and the wild West were favorites with juvenile readers, and he received many awards for them.

One of his best-known books, called Indian Paint, was made into a movie starring Johnny Crawford. His books have been translated into many foreign languages. One Glenn Balch novel, a dog story titled White Ruff, sold over a million copies, and the horse story Tiger Roan, has been reprinted 19 times.

In September, 1989 at the age of 86, Glenn Balch died as the result of a car accident. The Boise author brought a lot of pleasure to generations of young readers. His books are largely out of print today.

Published on January 20, 2021 04:00

January 19, 2021

You Do that Hoodoo that You Do so Well

The other day I was browsing through the Twenty-Third Biennial Report of the State Historical Society of Idaho published in 1922, as one does. It caught my attention that the report listed all the monuments in Idaho and associated with Idaho at the time. I skimmed through the list and descriptions to see if there might be blog fodder. Indeed. I will victimize you further with future posts but will restrain myself to a single monument for this one.

In fact, I’ll give only cursory attention to the monument mentioned because searching for more information on it led me down a path that with liberal use of unnecessary words will in itself be a blog.

See. I’ve already written 115 words without getting to the point. But I digress. But you knew that.

The monument that I wanted to research was the Sheepeater Monument. That monument, which I’ll tell you about in another post, was located near where Big Creek runs into the Salmon River. It’s a story worthy of a blog post, which I have already promised.

But today’s post, the one you’re reading, which has now run to 191 words without even approaching its subject, is about a “monument” I found while trying to do a little research on the aforementioned Sheepeater Monument.

Breaking out my copy of the trusty internet I did a Google image search for Sheepeater Monument, Idaho. What came up was an oddly shaped rock. It was actually more of a hoodoo which, now that the little ones have nodded off, I can proceed to describe.

The hoodoo in question, which was sometimes called Sheepeater’s Monument, is, as technical jargon would have it, really, really tall. I found a reference that said 70 feet. I don’t know. Photos show it towering over nearby trees. It is undeniably… let’s say tree-like, in that it is tall and narrow, but without the limbs one would usually find on a tall pine. A pole then. It’s like a pole. Eons ago some force, probably water followed later by wind, wore away layers of rock around it leaving a shaft of rock. And, to top it off, there is a large boulder resting impossibly on the summit of the hoodoo.

The formation has had some colorful names that I will leave up to you to imagine. It has a smaller pair of hoodoo companions nearby. This grouping of rude rocks at the head of Monumental Creek in Valley County is apparently why the creek is called that. We can be thankful for this unusual display of modesty on the part of the person who named it.

Photos of the formation are rare for a couple of reasons. The site is a bit challenging to find and hike to and getting the entire formation in a shot requires some clever positioning by the photographer. Alas, I did find one photo that may show the formation without its signature boulder on top. Say it isn’t so. Really. Let me know if you have recent, first-hand knowledge of the hoodoo. Rock or no rock, we await the revelation.

In fact, I’ll give only cursory attention to the monument mentioned because searching for more information on it led me down a path that with liberal use of unnecessary words will in itself be a blog.

See. I’ve already written 115 words without getting to the point. But I digress. But you knew that.

The monument that I wanted to research was the Sheepeater Monument. That monument, which I’ll tell you about in another post, was located near where Big Creek runs into the Salmon River. It’s a story worthy of a blog post, which I have already promised.

But today’s post, the one you’re reading, which has now run to 191 words without even approaching its subject, is about a “monument” I found while trying to do a little research on the aforementioned Sheepeater Monument.

Breaking out my copy of the trusty internet I did a Google image search for Sheepeater Monument, Idaho. What came up was an oddly shaped rock. It was actually more of a hoodoo which, now that the little ones have nodded off, I can proceed to describe.

The hoodoo in question, which was sometimes called Sheepeater’s Monument, is, as technical jargon would have it, really, really tall. I found a reference that said 70 feet. I don’t know. Photos show it towering over nearby trees. It is undeniably… let’s say tree-like, in that it is tall and narrow, but without the limbs one would usually find on a tall pine. A pole then. It’s like a pole. Eons ago some force, probably water followed later by wind, wore away layers of rock around it leaving a shaft of rock. And, to top it off, there is a large boulder resting impossibly on the summit of the hoodoo.

The formation has had some colorful names that I will leave up to you to imagine. It has a smaller pair of hoodoo companions nearby. This grouping of rude rocks at the head of Monumental Creek in Valley County is apparently why the creek is called that. We can be thankful for this unusual display of modesty on the part of the person who named it.

Photos of the formation are rare for a couple of reasons. The site is a bit challenging to find and hike to and getting the entire formation in a shot requires some clever positioning by the photographer. Alas, I did find one photo that may show the formation without its signature boulder on top. Say it isn’t so. Really. Let me know if you have recent, first-hand knowledge of the hoodoo. Rock or no rock, we await the revelation.

Published on January 19, 2021 04:00