Rick Just's Blog, page 149

September 28, 2020

The Hansen Bridge

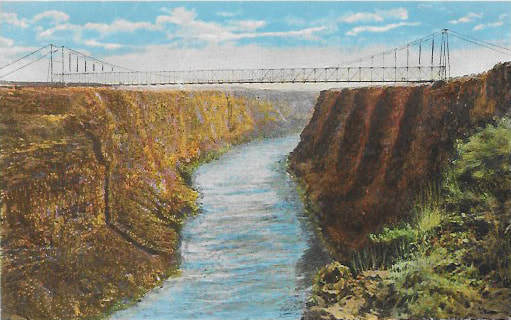

The Hansen Bridge, which spanned the Snake River Canyon near the town of Hansen, was a bit of a wonder in 1919 when it was built. It was 608 feet across, making it the second longest span in the country at the time. At 325 feet above the river, some accounts had it listed as being the highest suspension bridge in the world. And some accounts also listed it as being 345 feet above the Snake and 688 feet long. Break out your tape measure.

Superlatives aside, it held no record for width. At 16 feet, it seemed not to foresee a future where a couple of trucks might want to pass in opposite directions. The original wooden decking on the bridge also seemed better suited to wagons, whose use was waning, than automobiles.

Some locals may have been disappointed in the celebration for the bridge. Police seized 120 pints of booze one resident of Buhl was hoping to sell to the crowds when Gov. D.W. Davis officially opened the bridge.

The Hansen Bridge was important in its day, even if transportation needs quickly outgrew it. It remained in service until 1966.

Superlatives aside, it held no record for width. At 16 feet, it seemed not to foresee a future where a couple of trucks might want to pass in opposite directions. The original wooden decking on the bridge also seemed better suited to wagons, whose use was waning, than automobiles.

Some locals may have been disappointed in the celebration for the bridge. Police seized 120 pints of booze one resident of Buhl was hoping to sell to the crowds when Gov. D.W. Davis officially opened the bridge.

The Hansen Bridge was important in its day, even if transportation needs quickly outgrew it. It remained in service until 1966.

Published on September 28, 2020 04:00

September 27, 2020

Not that Betsey Ross

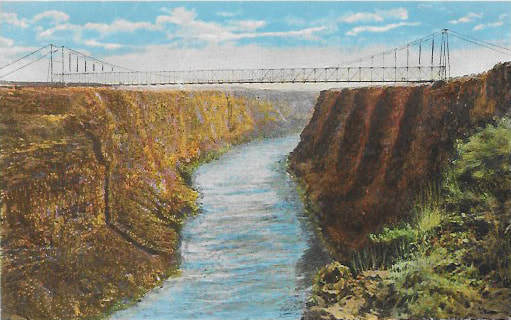

Not all that is written in stone is true. I did a post earlier about a monument memorializing a (probably) nonexistent massacre near Almo. We can trace the roots of that one and get at least an inkling of why the memorial exists. Not so with the memorial to Betsey Ross in the Forest Memorial Cemetery in Coeur d’Alene.

Yes, it is apparently supposed to honor the woman of flag-making legend, although her name did not have that extra E. She died in Philadelphia in 1836. This memorial doesn’t say she’s buried in Coeur d’Alene, just that she is being honored by one of her descendants, B.M. Ross. On one side of the monument B.M. Ross is listed as the son of James and Betsey Ross, born in 1834. Interesting, in that Betsy Ross would have been 82 in 1834, two years before she died. Also, she had seven daughters and no sons.

The Coeur d’Alene Parks Department, which manages the cemeteries in the city, has done an excellent walking tour brochure about the history buried (sorry) in the cemetery. That’s where I found most of the information for this post. If you know anything about Betsey Ross or B.M. Ross, they’d love to hear about it. Clearly someone spent quite a bit of money to put up the monument. The question is, why?

Yes, it is apparently supposed to honor the woman of flag-making legend, although her name did not have that extra E. She died in Philadelphia in 1836. This memorial doesn’t say she’s buried in Coeur d’Alene, just that she is being honored by one of her descendants, B.M. Ross. On one side of the monument B.M. Ross is listed as the son of James and Betsey Ross, born in 1834. Interesting, in that Betsy Ross would have been 82 in 1834, two years before she died. Also, she had seven daughters and no sons.

The Coeur d’Alene Parks Department, which manages the cemeteries in the city, has done an excellent walking tour brochure about the history buried (sorry) in the cemetery. That’s where I found most of the information for this post. If you know anything about Betsey Ross or B.M. Ross, they’d love to hear about it. Clearly someone spent quite a bit of money to put up the monument. The question is, why?

Published on September 27, 2020 04:00

September 26, 2020

Not About Finger Steaks

If there’s a subject more likely to start a fight than the alleged Chinese tunnels in Boise, it’s probably the question of who invented finger steaks. Since my blog is well-known for providing the definitive answer to such questions I can state, without reservations, that I don’t know.

Further, this post isn’t about finger steaks at all, really, though I will say that the Wikipedia page for finger steaks (of course there is one) credits Milo Bybee as the first to say he invented finger steaks. He worked for the Torch Cafe in Boise starting in 1946. He claimed he invented them while working as a butcher for the Forest Service in McCall and brought the recipe to the Torch. Others claim it was Willie Schrier, the owner of the Torch from 1953 to 1958, who invented finger steaks. Either way the Torch seems to have been where they got famous.

In fact, the first mention of finger steaks in Boise was an ad for the Torch in the Idaho Statesman in August of 1956. And that brings us to the point of this blog. Finger steaks, recall, are just the side dish in this one.

I wanted to call your attention to a series of Personal Services ads in the Statesman that started in May of 1957 and ended in October 1958. The ads seemed to be the brainchild of Willie Schrier. The first one to appear in the Personals read:

“ADVICE TO THE LOVELORN. . .Dear Dr. Willie: ‘I love a chorus girl…buy her jewels and ermine…she still says no.” Puzzled. Dear Puzzled: ‘Chorus girls don’t want diamonds and ermine any more…They just want one of my delectable Finger Steaks.’ Dr. Willie…The Torch Café…1828 Main.”

Another personal read, “Dear Dr. Willie: ‘My boy friend has small biceps. What should he do? Agnes.’ Dear Agnes: ‘Wash his head with kerosene. That’ll kill them. Then bring him to the Torch Café, 1826 Main, and a diet of Finger Steaks will build him up.’”

Soon, a neighboring restaurant got into the act: “DEAR WILLIE—The best way to improve your atmosphere at The Torch, 1826 Main, is to remove Willie. Signed, Vince and Ed, The Royal, 1112 Main.”

In the same Personals section, Willie ‘replied.’ “SHORTAGE—The Torch, 1826 Main, is serving so many Finger Steaks that the meat suppliers are trying to breed beef that will develop double tenderloins.”

In November 1957, this pairing appeared: “PEOPLE were up in the air over the Royal’s Smokqueed Ribs long before the Russians thought of Sputnik. Ed & Vince. The Royal, 1112 Main.”

“IT’S OBVIOUS that Ed & Vince at the ROYAL are related. Vince Aguirre is Grave… and Ed Graves wishes he could Aquirre the customers my FINGER STEAKS are winning over to the TORCH! Dr. Willie Schrier, PhD. The Torch, 18th & Main.”

This good-natured jabbing went on for a couple of years between the guys at the Royal and The Torch, until Willie Schrier started the Stagecoach Inn in Garden City. That just changed the venue.

In September 1959 came this pairing in the Personals: “ATTENTION DISC JOCKERYS: Did you know that the song called “Mack The Knife” was written about a Boise man? He is the guy in the Royal’s kitchen who slices the steaks so thin you can read a newspaper through them. At the Stagecoach Inn our steaks are so thick we have to put cushions on the chairs so the customer can see over the top of them. Signed, Willie Schrier.”

“GAMBLERS ATTENTION: It is NOT true that Willie’s Stagecoach Inn has revived slot machines in Garden City. The only gamble you take when you go there is whether or not your stomach will ever be the same again after eating one of his meals. Of course, there’s not even that gamble at The Royal. Signed, Ed and Vince.”

One more pair from December 1959: “SMART ROYAL customers aren’t buying snow tires this year. Since they can’t eat those tough Royal steaks, they’re tying them onto their regular tires. I hear they’re the best non-skid steaks sold. Signed, Willie Schrier.”

“WE HEAR FOLKS are getting leery of Willie’s holiday egg nog. Seems the eggs he used are so old one customer spotted a newly hatched chick swimming in the nog. Even worse the chick had the hiccups. Signed, Ed and Vince.”

The jibing continued until about 1971 when the Personals ads stopped. Willie’s humor continued to be on display for years on the sign out in front of the Stagecoach. He was often the butt of the joke on those.

One such posting read, “CLEAN UP GARDEN CITY—WILLIE GET OUT OF TOWN.” Unfortunately, the sign went up just about the same time Willie Nelson was about to perform at the Western Idaho Fair. Nelson’s people were not amused. They asked that the sign be taken down. It was. Then Willie Nelson showed up at the Stagecoach Inn to meet the other Willie. He was out of town at the time. Nelson left him a couple of tickets to his show. That’s when employees of the restaurant put up letters reading: “WILLIE, WHEN YOU LEAVE, TAKE WILLIE WITH YOU.”

Schrier passed the Stagecoach Inn on to his daughters when he retired. It was in the family for 50 years. Today it operates under new ownership. Willie Schrier passed away in 1996.

Further, this post isn’t about finger steaks at all, really, though I will say that the Wikipedia page for finger steaks (of course there is one) credits Milo Bybee as the first to say he invented finger steaks. He worked for the Torch Cafe in Boise starting in 1946. He claimed he invented them while working as a butcher for the Forest Service in McCall and brought the recipe to the Torch. Others claim it was Willie Schrier, the owner of the Torch from 1953 to 1958, who invented finger steaks. Either way the Torch seems to have been where they got famous.

In fact, the first mention of finger steaks in Boise was an ad for the Torch in the Idaho Statesman in August of 1956. And that brings us to the point of this blog. Finger steaks, recall, are just the side dish in this one.

I wanted to call your attention to a series of Personal Services ads in the Statesman that started in May of 1957 and ended in October 1958. The ads seemed to be the brainchild of Willie Schrier. The first one to appear in the Personals read:

“ADVICE TO THE LOVELORN. . .Dear Dr. Willie: ‘I love a chorus girl…buy her jewels and ermine…she still says no.” Puzzled. Dear Puzzled: ‘Chorus girls don’t want diamonds and ermine any more…They just want one of my delectable Finger Steaks.’ Dr. Willie…The Torch Café…1828 Main.”

Another personal read, “Dear Dr. Willie: ‘My boy friend has small biceps. What should he do? Agnes.’ Dear Agnes: ‘Wash his head with kerosene. That’ll kill them. Then bring him to the Torch Café, 1826 Main, and a diet of Finger Steaks will build him up.’”

Soon, a neighboring restaurant got into the act: “DEAR WILLIE—The best way to improve your atmosphere at The Torch, 1826 Main, is to remove Willie. Signed, Vince and Ed, The Royal, 1112 Main.”

In the same Personals section, Willie ‘replied.’ “SHORTAGE—The Torch, 1826 Main, is serving so many Finger Steaks that the meat suppliers are trying to breed beef that will develop double tenderloins.”

In November 1957, this pairing appeared: “PEOPLE were up in the air over the Royal’s Smokqueed Ribs long before the Russians thought of Sputnik. Ed & Vince. The Royal, 1112 Main.”

“IT’S OBVIOUS that Ed & Vince at the ROYAL are related. Vince Aguirre is Grave… and Ed Graves wishes he could Aquirre the customers my FINGER STEAKS are winning over to the TORCH! Dr. Willie Schrier, PhD. The Torch, 18th & Main.”

This good-natured jabbing went on for a couple of years between the guys at the Royal and The Torch, until Willie Schrier started the Stagecoach Inn in Garden City. That just changed the venue.

In September 1959 came this pairing in the Personals: “ATTENTION DISC JOCKERYS: Did you know that the song called “Mack The Knife” was written about a Boise man? He is the guy in the Royal’s kitchen who slices the steaks so thin you can read a newspaper through them. At the Stagecoach Inn our steaks are so thick we have to put cushions on the chairs so the customer can see over the top of them. Signed, Willie Schrier.”

“GAMBLERS ATTENTION: It is NOT true that Willie’s Stagecoach Inn has revived slot machines in Garden City. The only gamble you take when you go there is whether or not your stomach will ever be the same again after eating one of his meals. Of course, there’s not even that gamble at The Royal. Signed, Ed and Vince.”

One more pair from December 1959: “SMART ROYAL customers aren’t buying snow tires this year. Since they can’t eat those tough Royal steaks, they’re tying them onto their regular tires. I hear they’re the best non-skid steaks sold. Signed, Willie Schrier.”

“WE HEAR FOLKS are getting leery of Willie’s holiday egg nog. Seems the eggs he used are so old one customer spotted a newly hatched chick swimming in the nog. Even worse the chick had the hiccups. Signed, Ed and Vince.”

The jibing continued until about 1971 when the Personals ads stopped. Willie’s humor continued to be on display for years on the sign out in front of the Stagecoach. He was often the butt of the joke on those.

One such posting read, “CLEAN UP GARDEN CITY—WILLIE GET OUT OF TOWN.” Unfortunately, the sign went up just about the same time Willie Nelson was about to perform at the Western Idaho Fair. Nelson’s people were not amused. They asked that the sign be taken down. It was. Then Willie Nelson showed up at the Stagecoach Inn to meet the other Willie. He was out of town at the time. Nelson left him a couple of tickets to his show. That’s when employees of the restaurant put up letters reading: “WILLIE, WHEN YOU LEAVE, TAKE WILLIE WITH YOU.”

Schrier passed the Stagecoach Inn on to his daughters when he retired. It was in the family for 50 years. Today it operates under new ownership. Willie Schrier passed away in 1996.

Published on September 26, 2020 04:00

September 25, 2020

A Little Plate History

Today’s post owes much to Dan P. Smith’s little publication, A Complete Guide for Idaho License Plates and DAV Tags. Dan is a license plate collector and authority on Idaho plates.

I’m revisiting this subject because one of my readers asked when Idaho began using the numeral/letter county designators on license plates. The answer is 1932. Those designators have appeared ever since on most plates, but do not appear on specialty and personalized plates.

I was surprised to learn that there were Idaho plates issued before the state issued them. That is, six cities issued automobile license plates in the early years, starting in 1910. They are extremely rare. Only 14 are known to exist. Some were made of porcelain and some of steel. Some were made of leather by the car owners themselves and featured metal numbers of aluminum or brass. Issuing cities were Boise, Hailey, Lewiston, Nampa, Payette, Twin Falls, and Weiser.

State of Idaho plates were sold beginning in 1913. Motorcycle plates came along in 1915.

Information is hard to come by for plates issued before 1950. In 1950, according to Dan’s book, Idaho Governor C.A. Robbins offered the job of state transportation director to the Gooding County Assessor. The man wasn’t interested in the job, but did agree to travel the state visiting all 44 counties on a consulting basis to determine the needs of each county. The trip was reportedly a success, with many best practices implemented. While the man was out of his temporary office, someone decided it would be a good idea to clean it. They disposed of all the piles of paper and boxes of old records that were cluttering up the place. Those records happened to be the historic records of Idaho license plates.

Early license plates that cost a few dollars can fetch a few thousand dollars today, if they’re rare.

I guess I collect plates a bit, myself. Those pictured are some of the personalized plates I’ve used over the years. I still use the bottom two.

I’m revisiting this subject because one of my readers asked when Idaho began using the numeral/letter county designators on license plates. The answer is 1932. Those designators have appeared ever since on most plates, but do not appear on specialty and personalized plates.

I was surprised to learn that there were Idaho plates issued before the state issued them. That is, six cities issued automobile license plates in the early years, starting in 1910. They are extremely rare. Only 14 are known to exist. Some were made of porcelain and some of steel. Some were made of leather by the car owners themselves and featured metal numbers of aluminum or brass. Issuing cities were Boise, Hailey, Lewiston, Nampa, Payette, Twin Falls, and Weiser.

State of Idaho plates were sold beginning in 1913. Motorcycle plates came along in 1915.

Information is hard to come by for plates issued before 1950. In 1950, according to Dan’s book, Idaho Governor C.A. Robbins offered the job of state transportation director to the Gooding County Assessor. The man wasn’t interested in the job, but did agree to travel the state visiting all 44 counties on a consulting basis to determine the needs of each county. The trip was reportedly a success, with many best practices implemented. While the man was out of his temporary office, someone decided it would be a good idea to clean it. They disposed of all the piles of paper and boxes of old records that were cluttering up the place. Those records happened to be the historic records of Idaho license plates.

Early license plates that cost a few dollars can fetch a few thousand dollars today, if they’re rare.

I guess I collect plates a bit, myself. Those pictured are some of the personalized plates I’ve used over the years. I still use the bottom two.

Published on September 25, 2020 04:00

September 24, 2020

Payette Lake Before the Dam

I got an interesting question from a reader about Payette Lake. They wanted to know what the lake would have looked like about 1900. Would it have been smaller?

The answer is that the lake level would have been pretty much the same as it is today, as long as you were visiting the lake in the spring. As the summer wore on it would have dropped considerably, especially in dry years.

In 1920 the water users of Payette Valley got together to apply for a storage water right on the lake of 50,000 acre feet of water. The previous year had been a dry one, causing a shortage of irrigation water in the lower Payette valley. It was the first time that had happened. Irrigators wanted it to be the last.

The Lardo Dam was born. The 120-foot dam was built to a height of about 8 feet. That cost about $20,000, a fair piece of change in 1920. Its function was to hold the lake at or near its ordinary high water mark most of the season so that it could be drawn down as needed.

Things went along well for the Lardo Dam until August of 1943 when it washed out, dropping the lake level two feet in a single day. It was replaced later that year and is still in operation, keeping the lake high for boaters, swimmers and, not incidentally, irrigators.

One interesting side note about the dam was the article written about it in the Caldwell Tribune, on March 5, 1920. The lede paragraph said, in part, “According to the application filed with the state commissioner of something or other of the Governor’s cabinet…”

The commissioner of something or other? I suspect the writer plugged that in, meaning to find out the name of the something or other before publishing the article. Then they forgot, giving me the chance to make fun of them a hundred years later.

Payette Lake from Porcupine Point. Photo by Adam Zaragosa courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Payette Lake from Porcupine Point. Photo by Adam Zaragosa courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

The answer is that the lake level would have been pretty much the same as it is today, as long as you were visiting the lake in the spring. As the summer wore on it would have dropped considerably, especially in dry years.

In 1920 the water users of Payette Valley got together to apply for a storage water right on the lake of 50,000 acre feet of water. The previous year had been a dry one, causing a shortage of irrigation water in the lower Payette valley. It was the first time that had happened. Irrigators wanted it to be the last.

The Lardo Dam was born. The 120-foot dam was built to a height of about 8 feet. That cost about $20,000, a fair piece of change in 1920. Its function was to hold the lake at or near its ordinary high water mark most of the season so that it could be drawn down as needed.

Things went along well for the Lardo Dam until August of 1943 when it washed out, dropping the lake level two feet in a single day. It was replaced later that year and is still in operation, keeping the lake high for boaters, swimmers and, not incidentally, irrigators.

One interesting side note about the dam was the article written about it in the Caldwell Tribune, on March 5, 1920. The lede paragraph said, in part, “According to the application filed with the state commissioner of something or other of the Governor’s cabinet…”

The commissioner of something or other? I suspect the writer plugged that in, meaning to find out the name of the something or other before publishing the article. Then they forgot, giving me the chance to make fun of them a hundred years later.

Payette Lake from Porcupine Point. Photo by Adam Zaragosa courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Payette Lake from Porcupine Point. Photo by Adam Zaragosa courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Published on September 24, 2020 04:00

September 23, 2020

Gobo Fango

Gobo Fango is not a name you often encounter in Idaho history, memorable as it is. Fango was born in Eastern Cape Colony of what is now South Africa in about 1855. He was a member of the Gcaleka tribe. He was saved from a bloody war with the British that would kill 100,000 of his people, only to end up the victim of a range war some 27 years later in Idaho Territory.

Fango’s desperate, starving mother left him in the crook of a tree when he was three when she could no longer carry him. The sons of Henry and Ruth Talbot, English-speaking settlers, found him. The family adopted Gobo Fango. Or maybe they simply claimed him as property. In either case, they probably saved his life.

The Talbots became converts to the LDS religion. Records of their baptisms exist, though none such for Fango. They smuggled Fango out of the country and into the United States where they found their way to Utah in 1861.

Gobo Fango worked for the Talbots as an indentured servant, by some accounts, as a slave by others. He lived in a shed near their home. When a teenager he was sold, or given to another Mormon family.

Eventually Fango was on his own and working for a sheep operation near Oakley, in Idaho Territory. He was even able to acquire a herd of his own.

Cattlemen viewed sheep as a scourge that was destroying the range. Range wars broke out all over the West between sheep men and cattlemen.

It was one of those conflicts that brought an end to Gobo Fango.

The Idaho Territorial Legislature had passed a law known as the Two-Mile Limit intended to keep sheep grazers at least two miles away from a cattleman’s grazing claim. Early one day cattleman Frank Bedke and a companion rode into Fango’s camp to tell him he and his sheep were too close to Bedke’s claim and that he should leave. Fango resisted. Exactly what happened will never be known, but the black man ended up with a bullet passing through the back of his head and another tearing through his abdomen.

The cattlemen rode away. Gobo Fango, who, incredibly, was still alive, began crawling toward his employer’s home, holding his intestines in his hand as he dragged himself four and half miles.

Gobo Fango lived four or five days before succumbing to his wounds. He made out a will leaving his money and property to friends. Frank Bedke would be tried twice for his murder, with the first trial ending with a hung jury. The second time he was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

The headstone of Gobo Fango can be seen today in the Oakley Cemetery.

Fango’s desperate, starving mother left him in the crook of a tree when he was three when she could no longer carry him. The sons of Henry and Ruth Talbot, English-speaking settlers, found him. The family adopted Gobo Fango. Or maybe they simply claimed him as property. In either case, they probably saved his life.

The Talbots became converts to the LDS religion. Records of their baptisms exist, though none such for Fango. They smuggled Fango out of the country and into the United States where they found their way to Utah in 1861.

Gobo Fango worked for the Talbots as an indentured servant, by some accounts, as a slave by others. He lived in a shed near their home. When a teenager he was sold, or given to another Mormon family.

Eventually Fango was on his own and working for a sheep operation near Oakley, in Idaho Territory. He was even able to acquire a herd of his own.

Cattlemen viewed sheep as a scourge that was destroying the range. Range wars broke out all over the West between sheep men and cattlemen.

It was one of those conflicts that brought an end to Gobo Fango.

The Idaho Territorial Legislature had passed a law known as the Two-Mile Limit intended to keep sheep grazers at least two miles away from a cattleman’s grazing claim. Early one day cattleman Frank Bedke and a companion rode into Fango’s camp to tell him he and his sheep were too close to Bedke’s claim and that he should leave. Fango resisted. Exactly what happened will never be known, but the black man ended up with a bullet passing through the back of his head and another tearing through his abdomen.

The cattlemen rode away. Gobo Fango, who, incredibly, was still alive, began crawling toward his employer’s home, holding his intestines in his hand as he dragged himself four and half miles.

Gobo Fango lived four or five days before succumbing to his wounds. He made out a will leaving his money and property to friends. Frank Bedke would be tried twice for his murder, with the first trial ending with a hung jury. The second time he was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

The headstone of Gobo Fango can be seen today in the Oakley Cemetery.

Published on September 23, 2020 04:00

September 22, 2020

The First Women in Idaho's Legislature

In 1896, Idaho became the fourth state in the nation—preceded by Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah—to give women the right to vote. If you want to get technical, Idaho was actually the second state to do so, since Wyoming and Utah were both territories at the time. This was 23 years ahead of the 19th Amendment which gave that right to all women in the United States.

It wasn’t just voting that interested women. They wanted to be a part of the political process at every level. In 1898 voters elected three women to the Idaho Legislature, Mrs. Mary Wright from Kootenai County (left in the photo), Mrs. Hattie Noble from Boise County, and Mrs. Clara Pamelia Campbell from Ada County. It was the fifth Idaho Legislature.

On February 8, 1899, the Idaho Daily Statesman noted that Mrs. Wright had become the first woman to preside over the Idaho Legislature, and perhaps the first to preside over any legislature in the nation. She was chairman of the committee of the whole during the preceding afternoon and “ruled with a firm but impartial hand.”

Mary Wright was elected Chief Clerk of the House of Representatives, and went on to take a job as the private secretary of Congressman Thomas Glenn.

All of this seemed not to sit well with her husband, who “filed a red hot divorce bill” according the Idaho Statesman, reporting on the proceedings in a Sandpoint court in the April 26, 1904 edition. Mr. Wright claimed that while in the legislature in Boise she “mingled with divers men, at improper hours and times, making appointments with strange men at committee rooms and hotels.” He also claimed she lost $2,000 on the board of trade, and “used improper language before their son, a lad of 16.”

Mrs Wright shot back with a suit of her own claiming her husband had slandered her. The paper reported that “She produced two witnesses in court and showed that Wright had done little toward her support in years.” The divorce was granted… In favor of Mrs. Wright.

It wasn’t just voting that interested women. They wanted to be a part of the political process at every level. In 1898 voters elected three women to the Idaho Legislature, Mrs. Mary Wright from Kootenai County (left in the photo), Mrs. Hattie Noble from Boise County, and Mrs. Clara Pamelia Campbell from Ada County. It was the fifth Idaho Legislature.

On February 8, 1899, the Idaho Daily Statesman noted that Mrs. Wright had become the first woman to preside over the Idaho Legislature, and perhaps the first to preside over any legislature in the nation. She was chairman of the committee of the whole during the preceding afternoon and “ruled with a firm but impartial hand.”

Mary Wright was elected Chief Clerk of the House of Representatives, and went on to take a job as the private secretary of Congressman Thomas Glenn.

All of this seemed not to sit well with her husband, who “filed a red hot divorce bill” according the Idaho Statesman, reporting on the proceedings in a Sandpoint court in the April 26, 1904 edition. Mr. Wright claimed that while in the legislature in Boise she “mingled with divers men, at improper hours and times, making appointments with strange men at committee rooms and hotels.” He also claimed she lost $2,000 on the board of trade, and “used improper language before their son, a lad of 16.”

Mrs Wright shot back with a suit of her own claiming her husband had slandered her. The paper reported that “She produced two witnesses in court and showed that Wright had done little toward her support in years.” The divorce was granted… In favor of Mrs. Wright.

Published on September 22, 2020 04:00

September 21, 2020

A Hidden Elevator

When the center part of Idaho’s capitol building was built in 1905, the part with the dome, you could ride a special elevator to the third floor where the Idaho Supreme Court met. Over the years the wings were added to the building for the Idaho House and Senate. Sometime during a remodel the elevator was covered up. They found it again during renovation in 2007. It would lead to the JFAC hearing room today, if it was operable. It isn’t worth maintaining, but it is so pretty they decided to open it up for you to see it. It’s easy to miss, so if you’re wandering around looking at the beautiful building, be sure you ask where the old elevator is.

Published on September 21, 2020 04:00

September 20, 2020

Old 97, not

A minor piece of Civil War history rests quietly on the grounds of the Idaho Statehouse. It’s a 42-pound seacoast gun, a cannon used during the Civil War at Vicksburg. The “42-pound” is a reference to the weight of the load, not the weight of the gun which is cast iron. The cannon was forged in 1857. The number 79 is stamped at the top of the muzzle rim. It has been known as “Old Ninety-Seven.”

Old Ninety-Seven seems like an odd nickname for a cannon stamped with the number 79. An article about the artifact that appeared in the June 8, 1941 edition of the Idaho Statesman was headlined “Old ‘Ninety-Seven’ on Statehouse Lawn Symbolizes Past in National Defense.” The piece went on to describe the gun, much as I did in the beginning of this story, except that it stated the number stamped on the muzzle rim was 97. I checked, then rechecked the number. It is 79. Maybe someone glanced at it, then misremembered when they did a story about the gun. It stuck, possibly because the writer confused it with the train song, “The Wreck of Old 97,” which is what you get when you Google Old Ninety-Seven today.

That mystery aside, we know that the statehouse cannon was purchased by Idaho State Treasurer S.A. Hastings and U.S. Senator William Borah and donated to the state in 1910.

The gun has been fired three times while on the statehouse grounds, but never officially. An accidental “firing” took place during prohibition. The barrel of the gun was a handy place to store lunch paper, cigar butts, and other trash. Someone secreted away a bottle of moonshine in there. On a particularly hot day, that resulted in a minor explosion with liquor leaking from the lip of the gun.

In 1936, following an article in the Idaho Statesman that pointed out the gun had never been fired in Idaho (save for the moonshine incident), scalawags set off a charge in the cannon that peppered a nearby parked car with debris, ruining its paint job. Then, in 1946, “kids” lit off a charge of gunpowder in the cannon, which coughed up sticks, rocks, bottles, bottle caps and other debris from its throat. Eventually, groundskeepers plugged the cannon.

In 1942, when the nation was calling on everyone to recycle their metal scrap so it could be used for the war effort, Gov. Chase Clark proposed to scrap the old cannon. He ran into a bit of a buzz saw in the form of a group called the Boise Circle No. 5 of the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR).

The ladies questioned whether the governor even had the authority to scrap the cannon. Mrs. Francis Leonard, who was “instructed to protest for the GAR” according to an article in the Statesman at the time, said, “One of our members, who, in fact, as a small child, sat on Abraham Lincoln’s lap when he was running for President, summed up our position when she declared the governor should also scrap the statue of the late Gov. Frank Steunenberg along with the cannon.” Clark quickly backpedaled and the cannon stayed in place.

Old Ninety-Seven seems like an odd nickname for a cannon stamped with the number 79. An article about the artifact that appeared in the June 8, 1941 edition of the Idaho Statesman was headlined “Old ‘Ninety-Seven’ on Statehouse Lawn Symbolizes Past in National Defense.” The piece went on to describe the gun, much as I did in the beginning of this story, except that it stated the number stamped on the muzzle rim was 97. I checked, then rechecked the number. It is 79. Maybe someone glanced at it, then misremembered when they did a story about the gun. It stuck, possibly because the writer confused it with the train song, “The Wreck of Old 97,” which is what you get when you Google Old Ninety-Seven today.

That mystery aside, we know that the statehouse cannon was purchased by Idaho State Treasurer S.A. Hastings and U.S. Senator William Borah and donated to the state in 1910.

The gun has been fired three times while on the statehouse grounds, but never officially. An accidental “firing” took place during prohibition. The barrel of the gun was a handy place to store lunch paper, cigar butts, and other trash. Someone secreted away a bottle of moonshine in there. On a particularly hot day, that resulted in a minor explosion with liquor leaking from the lip of the gun.

In 1936, following an article in the Idaho Statesman that pointed out the gun had never been fired in Idaho (save for the moonshine incident), scalawags set off a charge in the cannon that peppered a nearby parked car with debris, ruining its paint job. Then, in 1946, “kids” lit off a charge of gunpowder in the cannon, which coughed up sticks, rocks, bottles, bottle caps and other debris from its throat. Eventually, groundskeepers plugged the cannon.

In 1942, when the nation was calling on everyone to recycle their metal scrap so it could be used for the war effort, Gov. Chase Clark proposed to scrap the old cannon. He ran into a bit of a buzz saw in the form of a group called the Boise Circle No. 5 of the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR).

The ladies questioned whether the governor even had the authority to scrap the cannon. Mrs. Francis Leonard, who was “instructed to protest for the GAR” according to an article in the Statesman at the time, said, “One of our members, who, in fact, as a small child, sat on Abraham Lincoln’s lap when he was running for President, summed up our position when she declared the governor should also scrap the statue of the late Gov. Frank Steunenberg along with the cannon.” Clark quickly backpedaled and the cannon stayed in place.

Published on September 20, 2020 04:00

September 19, 2020

Bulging Elk

So, listening to NPR one morning on our way to work a few years back my wife and I heard a story about a painting of an elk that was being hung in some congressional office in Washington, DC. The reporter noted that it was a painting of a “bulging” elk. Whether the reporter was caught by a typo, or simply didn’t have a clue about elk did not matter. We couldn’t get the image of “bulging” elk out of our minds.

Had the reporter ever heard elk bugling he probably would have caught the error. A bugling elk is hard to forget, as is someone imitating an elk by applying what looks like a radiator hose to their lips and proceeding to make a series of whistling, gasping, alien sounds that would seem designed to attract a steam engine.

Whether or not you or I are attracted to the sound of a bugling elk is beside the point. Other elk find it well worth their notice, and this mating call seems to be working. Idaho has an abundance of elk. In 1935, when the Idaho began keeping records, there were 1,821 elk harvested in the state. That was three years before the citizen initiative that created the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, so there were likely some elk taken that weren’t counted. Elk harvest today is more than ten times that number, with 20,532 taken in 2019 of an estimated 120,000 elk in the state.

Not a few of those were lured to their demise by someone playing a weird tune on a modified radiator hose.

Elk numbers are likely much higher today than they were when Lewis and Clark trekked through what would become Idaho. Elk are creatures that like grassy, open spaces with trees nearby where they can quickly disappear. Such spaces have opened considerably by logging the past 150 years or so.

Had the reporter ever heard elk bugling he probably would have caught the error. A bugling elk is hard to forget, as is someone imitating an elk by applying what looks like a radiator hose to their lips and proceeding to make a series of whistling, gasping, alien sounds that would seem designed to attract a steam engine.

Whether or not you or I are attracted to the sound of a bugling elk is beside the point. Other elk find it well worth their notice, and this mating call seems to be working. Idaho has an abundance of elk. In 1935, when the Idaho began keeping records, there were 1,821 elk harvested in the state. That was three years before the citizen initiative that created the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, so there were likely some elk taken that weren’t counted. Elk harvest today is more than ten times that number, with 20,532 taken in 2019 of an estimated 120,000 elk in the state.

Not a few of those were lured to their demise by someone playing a weird tune on a modified radiator hose.

Elk numbers are likely much higher today than they were when Lewis and Clark trekked through what would become Idaho. Elk are creatures that like grassy, open spaces with trees nearby where they can quickly disappear. Such spaces have opened considerably by logging the past 150 years or so.

Published on September 19, 2020 04:00