Rick Just's Blog, page 158

June 23, 2020

Moving the Mackay Depot

History sometimes turns up in the most surprising places. For instance, Riverside Boot and Saddle in Blackfoot is a store stuffed with Western wear and riding gear. They have a great selection of new and used trailers. They also have stores in Jerome and Caldwell.

I know that sounds like a commercial, but it’s only background for a little Idaho history trivia.

Up until 1972 the building where the Blackfoot store resides sat alongside railroad tracks in Mackay. In fact, it was the Mackay Depot, built by Union Pacific in about 1901. The Mackay Branch line was discontinued in 1961.

It’s not unusual for an old railroad depot to find another purpose, but the move from Mackay to Blackfoot (Rockford, to be exact) must have been one of the longer ones for traveling depots, a distance of about 80 miles.

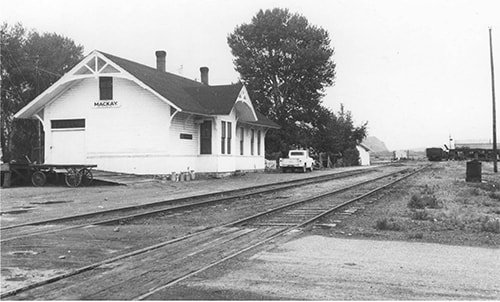

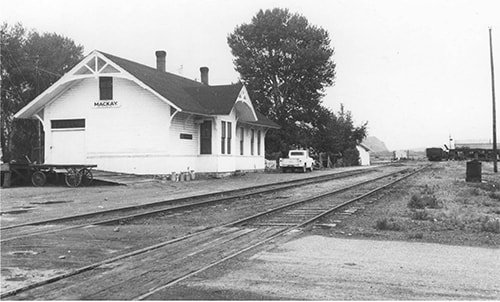

This is a photo of the Mackay Depot in 1962, about a year after the spur line shut down.

This is a photo of the Mackay Depot in 1962, about a year after the spur line shut down.  It's not easy to spot the depot in its new role as Riverside Boot and Saddle.

It's not easy to spot the depot in its new role as Riverside Boot and Saddle.

I know that sounds like a commercial, but it’s only background for a little Idaho history trivia.

Up until 1972 the building where the Blackfoot store resides sat alongside railroad tracks in Mackay. In fact, it was the Mackay Depot, built by Union Pacific in about 1901. The Mackay Branch line was discontinued in 1961.

It’s not unusual for an old railroad depot to find another purpose, but the move from Mackay to Blackfoot (Rockford, to be exact) must have been one of the longer ones for traveling depots, a distance of about 80 miles.

This is a photo of the Mackay Depot in 1962, about a year after the spur line shut down.

This is a photo of the Mackay Depot in 1962, about a year after the spur line shut down.  It's not easy to spot the depot in its new role as Riverside Boot and Saddle.

It's not easy to spot the depot in its new role as Riverside Boot and Saddle.

Published on June 23, 2020 04:00

June 22, 2020

Do You Have a Road Map?

Have you ever found yourself saying, “Somebody should do something about that”? Charlie Sampson, who often went by C.B., had one of those moments back in 1914. Rather than just letting the thought drift out of his head as you and I would likely do, Sampson took on a little job himself. He began marking highways in Idaho so people wouldn’t get lost.

Starting in 1906, Sampson ran the Sampson Music Company in Boise. His specialty was pianos. One of the ads for his pianos was a testimonial that read in part, “I play third grade music already, and my daddy only bought me my piano a little over a year ago.”

One day, while making a delivery in the desert south of town, Charlie got lost. That annoyed him. He thought there should be signs along the roads so travelers could find their way. He took that suggestion to local officials. They ignored him. To their surprise, Sampson proved that he was not one to let a good idea die. He began to mark the roads around Boise himself.

Sampson carried a bucket of orange paint with him wherever he went, and painted signs on rocks, trees, barns, bridges, fences... just about anything that didn't move. The routes he marked became known locally as the Sampson Trails. Of course, many of the larger signs also included a few words about the Sampson Music Company. Oh, and you could stop by the store and pick up a free map. By the way, could we interest you in a piano?

It wasn’t uncommon in the early days of automobile roads in the U.S. for car clubs to take on the job of marking routes and adding mileage signs to various locations. Since state governments didn’t take on the responsibility at that time, the clubs were free to mark roads and install signs of their own invention. Things got confusing when two or more car clubs competed to be the markers of a road, since there wasn’t always agreement on which was the main road and which was just a muddy side road. Different colored markings denoted the work of different clubs. Nothing was standardized. It was a mess. For instance, the first stop sign didn’t pop up until 1915 in Detroit, according to an article by Ethen Trex in the December 2010 edition of Mental Floss. It was a simple white, square sign with black lettering that was more of a suggestion than a regulation.

Sampson got the jump on car clubs in Idaho, and he did such a good job that he owned the Sampson Trails. He even hired a three-man crew to keep the signs in shape, spending thousands of dollars on the project.

In the mid-1920s, the Bureau of Highways decided to put a stop to Sampson's signing. They would sometimes mark a parallel route and paint over Sampson’s markers. The highway men, pun intended, claimed Sampson defaced the landscape with his orange paint. He probably did, but the Idaho Legislature didn't buy that argument. They passed a resolution commending Sampson for his efforts and gave him the right to continue marking the Sampson Trails.

Sampson eventually extended his work to five states, marking an astonishing seven thousand miles of road. Early highway maps often used the Sampson identifiers rather than state road names.

Charlie Sampson died in 1935, leaving the task of guiding people along the roadways to others. One who perpetuated Sampson’s effort is Cort Conley. His book, Idaho for the Curious, was where I first learned about the Sampson Trails. It is probably the best guide available for travelers interested in Idaho history.

The orange dot in this photo indicates one of Sampson's road markers. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The orange dot in this photo indicates one of Sampson's road markers. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Starting in 1906, Sampson ran the Sampson Music Company in Boise. His specialty was pianos. One of the ads for his pianos was a testimonial that read in part, “I play third grade music already, and my daddy only bought me my piano a little over a year ago.”

One day, while making a delivery in the desert south of town, Charlie got lost. That annoyed him. He thought there should be signs along the roads so travelers could find their way. He took that suggestion to local officials. They ignored him. To their surprise, Sampson proved that he was not one to let a good idea die. He began to mark the roads around Boise himself.

Sampson carried a bucket of orange paint with him wherever he went, and painted signs on rocks, trees, barns, bridges, fences... just about anything that didn't move. The routes he marked became known locally as the Sampson Trails. Of course, many of the larger signs also included a few words about the Sampson Music Company. Oh, and you could stop by the store and pick up a free map. By the way, could we interest you in a piano?

It wasn’t uncommon in the early days of automobile roads in the U.S. for car clubs to take on the job of marking routes and adding mileage signs to various locations. Since state governments didn’t take on the responsibility at that time, the clubs were free to mark roads and install signs of their own invention. Things got confusing when two or more car clubs competed to be the markers of a road, since there wasn’t always agreement on which was the main road and which was just a muddy side road. Different colored markings denoted the work of different clubs. Nothing was standardized. It was a mess. For instance, the first stop sign didn’t pop up until 1915 in Detroit, according to an article by Ethen Trex in the December 2010 edition of Mental Floss. It was a simple white, square sign with black lettering that was more of a suggestion than a regulation.

Sampson got the jump on car clubs in Idaho, and he did such a good job that he owned the Sampson Trails. He even hired a three-man crew to keep the signs in shape, spending thousands of dollars on the project.

In the mid-1920s, the Bureau of Highways decided to put a stop to Sampson's signing. They would sometimes mark a parallel route and paint over Sampson’s markers. The highway men, pun intended, claimed Sampson defaced the landscape with his orange paint. He probably did, but the Idaho Legislature didn't buy that argument. They passed a resolution commending Sampson for his efforts and gave him the right to continue marking the Sampson Trails.

Sampson eventually extended his work to five states, marking an astonishing seven thousand miles of road. Early highway maps often used the Sampson identifiers rather than state road names.

Charlie Sampson died in 1935, leaving the task of guiding people along the roadways to others. One who perpetuated Sampson’s effort is Cort Conley. His book, Idaho for the Curious, was where I first learned about the Sampson Trails. It is probably the best guide available for travelers interested in Idaho history.

The orange dot in this photo indicates one of Sampson's road markers. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The orange dot in this photo indicates one of Sampson's road markers. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on June 22, 2020 04:00

June 21, 2020

Pop Gave Me My Own Private Idaho

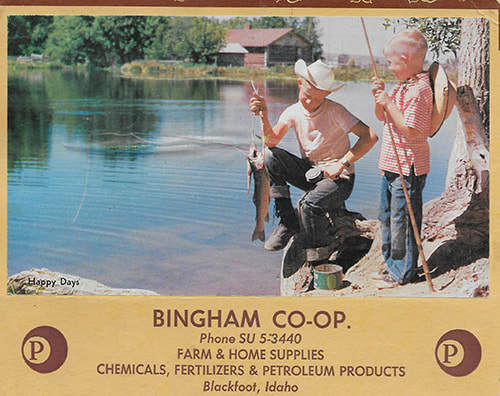

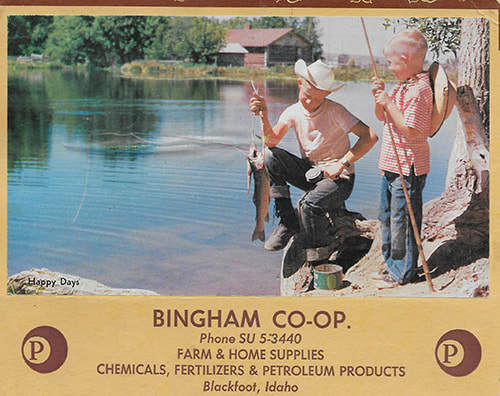

It's Fathers' Day. In honor of that I'm re-posting a story about a central part of my life that came from the mind of my father. He was a cowboy and a fisherman. The photo below shows his cowboy side. Below that is a picture of the Idaho he created for me. He passed away a couple of days after I turned 11, so I don't have as many memories of him as I'd like.

Here's that re-post.

We all have our own Idaho. I wrote about that a few years back in my novel, Keeping Private Idaho. Today—forgive my indulgence—I’m going to introduce you to mine.

Along about 1956 my father, who we called Pop, noticed that the configuration of ditches near the house on our family ranch outside of Blackfoot made three sides of a rectangle. I still remember him scraping up dirt with a squat little Ford tractor, pushing it up into what would become a dike along that fourth side.

Pop’s father and grandfather had built a major part of the canal system in Eastern Idaho, so he knew a little bit about making water do what he wanted it to. Usually that meant setting canvas dams in ditches and scraping off the high spots so that a field of alfalfa could get water. But while he was tromping around in waders with a shovel, pointing the way for water, he was thinking about his all-time favorite activity: fishing.

When pop diverted the water into what now had dikes on four sides, we saw his vision come to life. He had created a fish pond, about an acre in size. My brothers and I watched as the tankers came from Springfield with loads of rainbow trout, dumping them into the pond, which had quickly acquired moss, and bugs, and frogs.

Pop called his big idea Chick Just’s Trout Ranch. He had orange signs made that he could tack up on fence posts so people could find their way to the ranch. He charged by the pound for fish they caught. No charge if you didn’t catch anything. But they always caught fish. That was his joy. He liked nothing better than to see a kid catch her first trout.

So, paradise for me. I didn’t care much about fishing, but I cared for nothing more than I cared for that pond. It was my world; one which I could pole across in a skiff pretending I was Huck Finn, and swim in trying not to drown. I caught a million tadpoles and watched them turn into frogs, and chased dragonflies that were enemy helicopters.

That pond was the center of my life growing up. It must have occupied 50 years of my childhood. Yet, when I do the math now, I’m stunned by it. Pop died in 1960. We moved into town in 1961. Five years, not 50.

It was so idyllic for a kid you’d think I was making it up. But I have a picture. This one (second below) appeared on calendars and in magazines promoting Idaho for three or four years. It’s of me, the cute one, with my older brother, Kent. In the background, you can just make out our log house across the pond. My private Idaho. What does yours look like? This is Chick Just, the cowboy. It was taken by an artist friend of his named Glenn S. Potter. And, no, that isn't a cigarette in his right hand. It's just the space between his fingers. He never smoked.

This is Chick Just, the cowboy. It was taken by an artist friend of his named Glenn S. Potter. And, no, that isn't a cigarette in his right hand. It's just the space between his fingers. He never smoked.

Here's that re-post.

We all have our own Idaho. I wrote about that a few years back in my novel, Keeping Private Idaho. Today—forgive my indulgence—I’m going to introduce you to mine.

Along about 1956 my father, who we called Pop, noticed that the configuration of ditches near the house on our family ranch outside of Blackfoot made three sides of a rectangle. I still remember him scraping up dirt with a squat little Ford tractor, pushing it up into what would become a dike along that fourth side.

Pop’s father and grandfather had built a major part of the canal system in Eastern Idaho, so he knew a little bit about making water do what he wanted it to. Usually that meant setting canvas dams in ditches and scraping off the high spots so that a field of alfalfa could get water. But while he was tromping around in waders with a shovel, pointing the way for water, he was thinking about his all-time favorite activity: fishing.

When pop diverted the water into what now had dikes on four sides, we saw his vision come to life. He had created a fish pond, about an acre in size. My brothers and I watched as the tankers came from Springfield with loads of rainbow trout, dumping them into the pond, which had quickly acquired moss, and bugs, and frogs.

Pop called his big idea Chick Just’s Trout Ranch. He had orange signs made that he could tack up on fence posts so people could find their way to the ranch. He charged by the pound for fish they caught. No charge if you didn’t catch anything. But they always caught fish. That was his joy. He liked nothing better than to see a kid catch her first trout.

So, paradise for me. I didn’t care much about fishing, but I cared for nothing more than I cared for that pond. It was my world; one which I could pole across in a skiff pretending I was Huck Finn, and swim in trying not to drown. I caught a million tadpoles and watched them turn into frogs, and chased dragonflies that were enemy helicopters.

That pond was the center of my life growing up. It must have occupied 50 years of my childhood. Yet, when I do the math now, I’m stunned by it. Pop died in 1960. We moved into town in 1961. Five years, not 50.

It was so idyllic for a kid you’d think I was making it up. But I have a picture. This one (second below) appeared on calendars and in magazines promoting Idaho for three or four years. It’s of me, the cute one, with my older brother, Kent. In the background, you can just make out our log house across the pond. My private Idaho. What does yours look like?

This is Chick Just, the cowboy. It was taken by an artist friend of his named Glenn S. Potter. And, no, that isn't a cigarette in his right hand. It's just the space between his fingers. He never smoked.

This is Chick Just, the cowboy. It was taken by an artist friend of his named Glenn S. Potter. And, no, that isn't a cigarette in his right hand. It's just the space between his fingers. He never smoked.

Published on June 21, 2020 04:00

June 20, 2020

Special Guests at Farragut

The top picture is of a group of troops at Farragut Naval Training Station getting ready to board “cattle cars” for some work assignment. Do you notice anything unusual about them?

The second photo gives you a clue. Their camp newsletter was in German. This particular issue announces the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1945. Roosevelt had visited FNTS in 1942.

Perhaps as many as 926 POWs spent time at Farragut, clearing brush and shoveling coal mostly, but also as bakers, cooks, storekeepers, and firefighters. Long after the war, a former prisoner would occasionally show up at Farragut State Park for a visit. They generally had good memories.

The bottom photo is one of the POWs working with a horse on stable detail. His name was Werner Wagner. The horse’s name was Dime.

The second photo gives you a clue. Their camp newsletter was in German. This particular issue announces the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1945. Roosevelt had visited FNTS in 1942.

Perhaps as many as 926 POWs spent time at Farragut, clearing brush and shoveling coal mostly, but also as bakers, cooks, storekeepers, and firefighters. Long after the war, a former prisoner would occasionally show up at Farragut State Park for a visit. They generally had good memories.

The bottom photo is one of the POWs working with a horse on stable detail. His name was Werner Wagner. The horse’s name was Dime.

Published on June 20, 2020 04:00

June 19, 2020

The Idaho Stop

Today’s post is another in our occasional Then and Now series.

Bicycles have been in Idaho since territorial days. Unlike horse-drawn conveyances, bikes were not replaced by automobiles.

In May 1911, the Boise Evening Capital News was effusive about the future of the bicycle. “No question about it—the bicycle is coming into its own again. Its fine record in the war, its many-sided utility in modern business, its wonderful influence for health, coupled with its undoubted economy and convenience—all have combined to make it even more desirable than before.”

A.P. Tyler, the local Firestone dealer was enthusiastic about bicycles, and the “Non-Skid” tires Firestone was selling. “I look for a big year for the bicycle trade generally. (Bicycles) meet a distinct need in our modern life—as the only really practical self-propelled vehicle.”

Fast forward to 1982 when Idaho showed its love for bicycles in a unique way. The Legislature that year was revising traffic rules and decided to stop cluttering up judicial calendars with “technical violations” of traffic control devices, i.e., stop signs. That was the invention of a law that has become known as the Idaho Stop. Bike riders in Idaho can treat a stop sign the same way drivers treat a yield sign. That is, if the coast is clear they can roll right through it. A later revision to Idaho code made it legal for bike riders to treat a stop light the same way vehicle drivers treat a stop sign: Stop, check to see if the way is clear, then proceed.

Several other jurisdictions across the country have tried implementing the Idaho Stop for bicyclists. To date, Idaho is the only place it is legal statewide.

Bicycles have been in Idaho since territorial days. Unlike horse-drawn conveyances, bikes were not replaced by automobiles.

In May 1911, the Boise Evening Capital News was effusive about the future of the bicycle. “No question about it—the bicycle is coming into its own again. Its fine record in the war, its many-sided utility in modern business, its wonderful influence for health, coupled with its undoubted economy and convenience—all have combined to make it even more desirable than before.”

A.P. Tyler, the local Firestone dealer was enthusiastic about bicycles, and the “Non-Skid” tires Firestone was selling. “I look for a big year for the bicycle trade generally. (Bicycles) meet a distinct need in our modern life—as the only really practical self-propelled vehicle.”

Fast forward to 1982 when Idaho showed its love for bicycles in a unique way. The Legislature that year was revising traffic rules and decided to stop cluttering up judicial calendars with “technical violations” of traffic control devices, i.e., stop signs. That was the invention of a law that has become known as the Idaho Stop. Bike riders in Idaho can treat a stop sign the same way drivers treat a yield sign. That is, if the coast is clear they can roll right through it. A later revision to Idaho code made it legal for bike riders to treat a stop light the same way vehicle drivers treat a stop sign: Stop, check to see if the way is clear, then proceed.

Several other jurisdictions across the country have tried implementing the Idaho Stop for bicyclists. To date, Idaho is the only place it is legal statewide.

Published on June 19, 2020 04:00

June 18, 2020

Mackay Shine

If there’s one thing Mackay is known for today, it is that newcomers to Idaho can almost never pronounce it correctly. The name is pronounced "Mackie" with the accent on the first syllable.

It was apparently better known about 100 years ago as the place where good liquor originated.

Mick Hoover, the curator of the Lost River Museum, says that the moonshine operation in Mackay during Prohibition was on an industrial scale. Barrels of corn came into the Mackay Depot marked ‘corn for distilling,’ along with sugar and yeast. Everyone seemed to know what the ingredients were for but chose to not notice them. “Mackay Shine” was shipped by rail to Chicago and points east. It became known across the country for its quality, allegedly because the pure water in the area made for a good product. There is a small moonshine still on display in the museum.

But it wasn’t just corn liquor that Mackay was known for. On September 10, 1917, there was a report in the Blackfoot Idaho Republican, that a distillery was discovered in Custer County by the sheriff of Butte County, who was looking for the source of prune brandy that had been showing up in the area.

“For some time an intoxicating beverage has been used freely in the vicinity of the distillery,” the article read, “and the officials have been baffled in their efforts to located its source.” The distillery had been found only after “every possible ruse (had) been resorted to.”

The black market in moonshine came early to Idaho. The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified in January 1919, but Idaho had outlawed the sale of booze in 1917. The Eighteenth Amendment was eventually repealed by the Twenty-First Amendment in 1933, after it became clear Prohibition was causing more problems than it solved.

Governor Moses Alexander signing the bill that outlawed booze in Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Governor Moses Alexander signing the bill that outlawed booze in Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

It was apparently better known about 100 years ago as the place where good liquor originated.

Mick Hoover, the curator of the Lost River Museum, says that the moonshine operation in Mackay during Prohibition was on an industrial scale. Barrels of corn came into the Mackay Depot marked ‘corn for distilling,’ along with sugar and yeast. Everyone seemed to know what the ingredients were for but chose to not notice them. “Mackay Shine” was shipped by rail to Chicago and points east. It became known across the country for its quality, allegedly because the pure water in the area made for a good product. There is a small moonshine still on display in the museum.

But it wasn’t just corn liquor that Mackay was known for. On September 10, 1917, there was a report in the Blackfoot Idaho Republican, that a distillery was discovered in Custer County by the sheriff of Butte County, who was looking for the source of prune brandy that had been showing up in the area.

“For some time an intoxicating beverage has been used freely in the vicinity of the distillery,” the article read, “and the officials have been baffled in their efforts to located its source.” The distillery had been found only after “every possible ruse (had) been resorted to.”

The black market in moonshine came early to Idaho. The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified in January 1919, but Idaho had outlawed the sale of booze in 1917. The Eighteenth Amendment was eventually repealed by the Twenty-First Amendment in 1933, after it became clear Prohibition was causing more problems than it solved.

Governor Moses Alexander signing the bill that outlawed booze in Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Governor Moses Alexander signing the bill that outlawed booze in Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Published on June 18, 2020 04:00

June 17, 2020

That Jerk, Ilias Pierce

Randy Stapilus’ book

Speaking Ill of the Dead, Jerks in Idaho History

is an interesting read. He has a chapter on Elias Davidson Pierce. Pierce’s jerkiness, in Randy’s telling, comes from his complete disregard for both advice from authorities and reservation boundaries. I recommend you read the book to find out more.

Today, I’m going to pull out just a few tidbits that I found interesting.

Pierce was the first man to name a town in Idaho—or what would be Idaho—after himself. Others with little modesty would follow. His town came along in 1860 when he set it up on the Nez Perce Reservation to service miners. The town was called… Wait, have you been paying attention at all?

So, Pierce, Idaho grew up fast. Thousands came to mine gold and by 1862 it was the county seat of Shoshone County. Not the Shoshone County we know and love today, but Shoshone County, Washington Territory. Idaho Territory was still a year away. Even so, when they built the courthouse it would, upon Idaho gaining territorial status, become the territory’s first government building. It remains the oldest government building in Idaho (photo).

Pierce glittered like gold in a pan and for about that long. By 1863 the population dropped from several thousand to about 500, because gold glittered somewhere else, drawing miners away. That’s about the population of Pierce today.

Today, I’m going to pull out just a few tidbits that I found interesting.

Pierce was the first man to name a town in Idaho—or what would be Idaho—after himself. Others with little modesty would follow. His town came along in 1860 when he set it up on the Nez Perce Reservation to service miners. The town was called… Wait, have you been paying attention at all?

So, Pierce, Idaho grew up fast. Thousands came to mine gold and by 1862 it was the county seat of Shoshone County. Not the Shoshone County we know and love today, but Shoshone County, Washington Territory. Idaho Territory was still a year away. Even so, when they built the courthouse it would, upon Idaho gaining territorial status, become the territory’s first government building. It remains the oldest government building in Idaho (photo).

Pierce glittered like gold in a pan and for about that long. By 1863 the population dropped from several thousand to about 500, because gold glittered somewhere else, drawing miners away. That’s about the population of Pierce today.

Published on June 17, 2020 04:00

June 16, 2020

Boise's Lincoln Statues

Boise has two statues of President Abraham Lincoln. The first is on the capitol grounds in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest Lincoln statue in the West. It was first installed at the Soldiers Home in 1915, then moved to the Idaho Veterans Home in East Boise. In 2009 it was moved to its present location. It's one of six duplicates of a piece sculpted by Alphonso Pelzer. The original statue is in New Jersey.

The other Lincoln is a giant sculpture, 9 feet tall, and he’s sitting on a bench. You can sit with him in Julia Davis Park. Why two Lincolns in Idaho? He signed the act creating Idaho Territory in 1863. Fun facts: the sitting Lincoln sculpture is a copy of one created by Gutzon Borglum. In spite of his weird name, you need to know that he carved the faces on Mount Rushmore and that he was born in St. Charles, Idaho Territory, in 1867. Oh, and the original of the sitting Lincoln is also in New Jersey.

The other Lincoln is a giant sculpture, 9 feet tall, and he’s sitting on a bench. You can sit with him in Julia Davis Park. Why two Lincolns in Idaho? He signed the act creating Idaho Territory in 1863. Fun facts: the sitting Lincoln sculpture is a copy of one created by Gutzon Borglum. In spite of his weird name, you need to know that he carved the faces on Mount Rushmore and that he was born in St. Charles, Idaho Territory, in 1867. Oh, and the original of the sitting Lincoln is also in New Jersey.

Published on June 16, 2020 04:00

June 15, 2020

Meet William Orville Casey, a blind man with great sight

On September 12, 1906, Governor Frank Gooding decided to stop in to pay a visit to the students of the brand-new Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind in Gooding. The town of Gooding as well as the county of Gooding were both named after the governor. As it turned out, one of the students he greeted that day, a 7-year-old blind boy from the Treasure Valley named William Orville Casey, would one day be honored in a similar way.

Casey, who went by Orville most of his life, was blinded at age 4 when he got typhoid fever. He was in the first class at the new school, learning to get along without his sight.

Orville became a fine judge of animals, especially the milk cows he purchased for his dairy in Ustick, near McMillan and Maple Grove. When it came time to buy a cow the auctioneer at the local sales yard allowed Casey to get into the ring with a prospective animal, back it into a corner, and feel along its body to determine its quality. This wasn’t just for show. Lewis W. Morely, national secretary of the American Jersey Cattle Club, came to Boise in 1939 and visited the Casey dairy. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying, “This man has accomplished through his fingertips the ability to expertly judge a fine cow. Individual animals in his Jersey herd compare favorably with some of the best cows in the larger herds.” Casey’s cows proved his skill by winning many ribbons at the fair.

His visits to the auction ring gave Casey an idea for a little business that would serve him well over the years. He set up a card table with snacks for sale to auction goers. He knew coins by size and weight and trusted buyers when they told him the denomination of a bill. He claimed he could tell if they were lying by the tone of their voice.

He ran his dairy from 1923 to 1952. That’s when he took his small concession business to the Idaho statehouse. Casey purchased a small booth inside the capitol and opened what would become known as Casey’s Corner. He became a favorite with elected officials and visitors during the Legislative session. His grandson, Greg Casey, remembers helping out by taking coffee up to the second floor many times for Governor Robert E. Smylie.

Orville Casey retired from his concession stand at age 65 in 1964. He kept busy gardening — demonstrating an amazing ability to distinguish between weeds and vegetables — and started a wood cutting business.

Sighted folks marveled at his business and farming skills. Those in the blind community recognized him for many years of leadership. Orville Casey was the long-time president of the Idaho Society of the Blind, hosting annual picnics at his farm during the organization’s conventions.

In 1975, Governor Cecil Andrus presided over a ceremony naming the new high school building at the Idaho State School for the Deaf and Blind the Casey building. With remodeling and new construction, it has become the Casey Wing today, honoring the first blind graduate of the school.

William Orville Casey died in 1986 and is buried at the Joplin Pioneer Cemetery in Meridian. Orville riding a horse on his farm.

Orville riding a horse on his farm.

Casey, who went by Orville most of his life, was blinded at age 4 when he got typhoid fever. He was in the first class at the new school, learning to get along without his sight.

Orville became a fine judge of animals, especially the milk cows he purchased for his dairy in Ustick, near McMillan and Maple Grove. When it came time to buy a cow the auctioneer at the local sales yard allowed Casey to get into the ring with a prospective animal, back it into a corner, and feel along its body to determine its quality. This wasn’t just for show. Lewis W. Morely, national secretary of the American Jersey Cattle Club, came to Boise in 1939 and visited the Casey dairy. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying, “This man has accomplished through his fingertips the ability to expertly judge a fine cow. Individual animals in his Jersey herd compare favorably with some of the best cows in the larger herds.” Casey’s cows proved his skill by winning many ribbons at the fair.

His visits to the auction ring gave Casey an idea for a little business that would serve him well over the years. He set up a card table with snacks for sale to auction goers. He knew coins by size and weight and trusted buyers when they told him the denomination of a bill. He claimed he could tell if they were lying by the tone of their voice.

He ran his dairy from 1923 to 1952. That’s when he took his small concession business to the Idaho statehouse. Casey purchased a small booth inside the capitol and opened what would become known as Casey’s Corner. He became a favorite with elected officials and visitors during the Legislative session. His grandson, Greg Casey, remembers helping out by taking coffee up to the second floor many times for Governor Robert E. Smylie.

Orville Casey retired from his concession stand at age 65 in 1964. He kept busy gardening — demonstrating an amazing ability to distinguish between weeds and vegetables — and started a wood cutting business.

Sighted folks marveled at his business and farming skills. Those in the blind community recognized him for many years of leadership. Orville Casey was the long-time president of the Idaho Society of the Blind, hosting annual picnics at his farm during the organization’s conventions.

In 1975, Governor Cecil Andrus presided over a ceremony naming the new high school building at the Idaho State School for the Deaf and Blind the Casey building. With remodeling and new construction, it has become the Casey Wing today, honoring the first blind graduate of the school.

William Orville Casey died in 1986 and is buried at the Joplin Pioneer Cemetery in Meridian.

Orville riding a horse on his farm.

Orville riding a horse on his farm.

Published on June 15, 2020 04:00

June 14, 2020

Lewiston Flight Training Program

From 1938 until 1944, the federal government operated a Civilian Aeronautics Administration program to train pilots. It was called the Civilian Pilot Training Program. The government would pay for 72 hours of ground instruction and 35-50 hours of flight instruction to create more civilian pilots. During later iterations of the program, military pilots got their first taste of the air through an expanded program.

Lewiston State Normal School was one of 1,132 educational institutions to create a pilot training program. They contracted with Zimmerly Air Transport to train Navy cadets from 1942 to 1943.

The top photo shows an airport shuttle for the program, while the bottom picture, is the “9:20 flight of Intermediate students taxiing in a zig-zag manner to the end of the field for takeoff.” Both photos are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Lewiston State Normal School was one of 1,132 educational institutions to create a pilot training program. They contracted with Zimmerly Air Transport to train Navy cadets from 1942 to 1943.

The top photo shows an airport shuttle for the program, while the bottom picture, is the “9:20 flight of Intermediate students taxiing in a zig-zag manner to the end of the field for takeoff.” Both photos are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on June 14, 2020 04:00