Rick Just's Blog, page 161

May 24, 2020

The State Horse

Idaho is horse country and has been for more than 250 years. Idaho even stakes a claim to a breed of horse, the appaloosa.

The appaloosa horse can be traced back at least to the Mongols in ancient China. It is the oldest identifiable breed of horse. It wasn’t called the appaloosa until it became associated with a place that would become Idaho. The horses were well known on the Palouse prairie of northern Idaho, and over the years those Palouse horses, became appaloosas.

The spotted horses came to the Northwest by way of Mexico. Spanish conquistadors lost or traded away enough of them to assure thriving herds in the new world. The Shoshone Tribe had them first, but it was the Nez Perce who perfected the breed.

Horses gave the Nez Perce a greatly expanded range, and produced a whole new way of living for them. They became buffalo hunters, and developed trade relationships with other tribes far removed from their traditional range.

The appaloosa breed was nearly lost when the great Nez Perce herds were split up and scattered following the Nez Perce War. An ambitious plan to save the horses brought the breed back from near extinction in the 1930s.

Today, thousands of the tough little horses with spotted blankets on their rear quarters can be seen in Idaho and around the world. If you visit Moscow, Idaho, don’t miss the Appaloosa Museum, where you can learn the complete story of the breed that became Idaho’s State Horse in 1975.

The appaloosa horse can be traced back at least to the Mongols in ancient China. It is the oldest identifiable breed of horse. It wasn’t called the appaloosa until it became associated with a place that would become Idaho. The horses were well known on the Palouse prairie of northern Idaho, and over the years those Palouse horses, became appaloosas.

The spotted horses came to the Northwest by way of Mexico. Spanish conquistadors lost or traded away enough of them to assure thriving herds in the new world. The Shoshone Tribe had them first, but it was the Nez Perce who perfected the breed.

Horses gave the Nez Perce a greatly expanded range, and produced a whole new way of living for them. They became buffalo hunters, and developed trade relationships with other tribes far removed from their traditional range.

The appaloosa breed was nearly lost when the great Nez Perce herds were split up and scattered following the Nez Perce War. An ambitious plan to save the horses brought the breed back from near extinction in the 1930s.

Today, thousands of the tough little horses with spotted blankets on their rear quarters can be seen in Idaho and around the world. If you visit Moscow, Idaho, don’t miss the Appaloosa Museum, where you can learn the complete story of the breed that became Idaho’s State Horse in 1975.

Published on May 24, 2020 04:00

May 23, 2020

Jerry Kramer

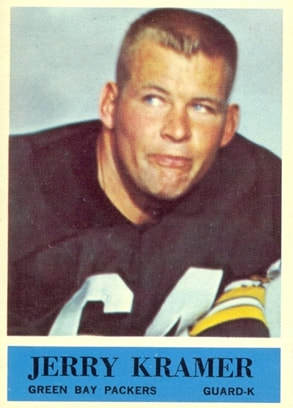

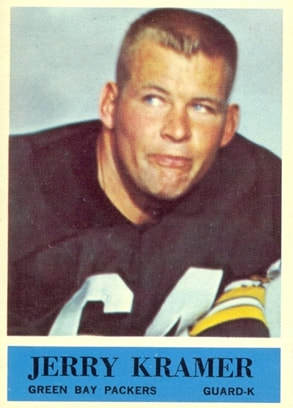

Here's a trivia question for you. Where did the man named the outstanding guard in the history of professional football grow up? Idaho, of course, but which town?

Football fans got this one right away. Jerry Kramer, named the outstanding guard in the history of professional football back in 1969, grew up in Sandpoint, Idaho. Kramer attended high school there, then went on to the University of Idaho, where he was a business major and football player.

Kramer was drafted by the Green Bay Packers in the fourth round of the 1958 NFL draft. He became a legendary guard with the team when he blocked Jethro Pugh in a do-or-die effort that allowed Bart Starr to make a winning touchdown and clinch the NFL championship in 1967.

The Packers called on Kramer's versatility in 1962 when their placekicker was injured. Jerry Kramer made nine of eleven field goal attempts and 38 of 39 extra points. Not a bad effort for a fill-in place-kicker.

Before retiring in 1968, Kramer played on five championship teams, was named All-Pro five times, and participated in three Pro Bowls. He played for the Packers in the first two Super Bowls. The team won them both.

After appearing as a finalist for induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame ten times, and is a member of the NFL's 50th Anniversary All-Time team. For many years he was the only member of that team not in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He was nominated ten times. Finally, at age 82, he got that well-deserved honor in 2018.

Kramer wrote several books about his football career, including Instant Replay: The Green Bay Diary of Jerry Kramer.

Football fans got this one right away. Jerry Kramer, named the outstanding guard in the history of professional football back in 1969, grew up in Sandpoint, Idaho. Kramer attended high school there, then went on to the University of Idaho, where he was a business major and football player.

Kramer was drafted by the Green Bay Packers in the fourth round of the 1958 NFL draft. He became a legendary guard with the team when he blocked Jethro Pugh in a do-or-die effort that allowed Bart Starr to make a winning touchdown and clinch the NFL championship in 1967.

The Packers called on Kramer's versatility in 1962 when their placekicker was injured. Jerry Kramer made nine of eleven field goal attempts and 38 of 39 extra points. Not a bad effort for a fill-in place-kicker.

Before retiring in 1968, Kramer played on five championship teams, was named All-Pro five times, and participated in three Pro Bowls. He played for the Packers in the first two Super Bowls. The team won them both.

After appearing as a finalist for induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame ten times, and is a member of the NFL's 50th Anniversary All-Time team. For many years he was the only member of that team not in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He was nominated ten times. Finally, at age 82, he got that well-deserved honor in 2018.

Kramer wrote several books about his football career, including Instant Replay: The Green Bay Diary of Jerry Kramer.

Published on May 23, 2020 04:30

May 22, 2020

The Iconic Idanha

Today you’d be hard pressed to find a residential lot in Boise for $125,000. In 1900 that amount built Boise’s most expensive building. The Idanha Hotel, which opened for business on January 3, 1901. It boasted 140 rooms on six floors with three grand turrets on the north, east, and west corners at 10th and Main. It was the tallest structure in the state and housed the state’s first elevator.

The building is so iconic in Boise that it is a surprise to many to learn that It wasn’t Idaho’s first Idanha. The first one was built in 1887 in Soda Springs. That Idanha was a luxury hotel, with electric lights and natural gas heating. The Tri-Weekly Statesman quoted a gentleman who had seen the Soda Springs hotel as saying “the structure was not only one of the most complete in the West, but for its size one of the finest in the world.”

The two hotels were related only by name, and there is no solid evidence that the one in Boise was named after the Soda Springs Idanha. Developers likely knew about the first hotel, which had a good reputation at the time, so, why not borrow the name? The first Idanha had borrowed its name, after all. The moniker first appeared on the labels of Idanha Mineral Water, bottled in Soda Springs and sold all over the United States. But, let’s leave the Soda Springs hotel, which burned down in 1921, and get back to Boise’s grand hotel.

As the preferred place to stay in town for decades, the Idanha saw a lot of history. Walter “Big Train” Johnson, years before his induction into baseball’s hall of fame, practiced pitches in the hallway of the Idanha, shattering an inconveniently placed chamber pot with one low pitch.

Movie star Ethel Barrymore stayed there while attending the high-profile Haywood trial. “Big Bill” Haywood, a leader of the International Workers of the World was on trial for hiring Harry Orchard to assassinate Frank Steunenberg, a former Idaho governor who had clashed with the union. It was Clarence Darrow for the defense.

The Idanha came close to being the site of the assassination, until Harry Orchard had second thoughts about the bomb he had placed under Steunenberg’s bed. He disconnected the device because he feared it might injure or kill a chambermaid. Orchard planted another bomb at the gate of the former governor’s home in Caldwell to complete the job.

Famous folks who stayed at the Idanha included William Jennings Bryan, Sally Rand, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Polly Bemis. The legendary little Chinese woman who lived in the Salmon River country got her first elevator ride there.

And, since there’s always a remote chance someone may consider me famous one day, I must mention that I got to stay in a second-floor turret room courtesy of the federal government the night before I was inducted into the Marine Corps. It was easily the best part of that experience.

The Idanha is no longer a hotel. In recent years it was converted into an apartment building with 80 small apartments ranging in size from 380 to 786 square feet. That historic elevator has been giving tenants and management grief in recent years, becoming increasing unreliable.

From the outside the Idanha looks much the same as the day it opened. Though Vardis Fisher wrote in his 1936 guide to Boise, published only recently, “nobody finds it beautiful today,” that opinion about the Idanha is likely a minority one in 2020.

The Idanha in 1979. Photo by Leo J. "Scoop" Leeburn, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

The Idanha in 1979. Photo by Leo J. "Scoop" Leeburn, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

The building is so iconic in Boise that it is a surprise to many to learn that It wasn’t Idaho’s first Idanha. The first one was built in 1887 in Soda Springs. That Idanha was a luxury hotel, with electric lights and natural gas heating. The Tri-Weekly Statesman quoted a gentleman who had seen the Soda Springs hotel as saying “the structure was not only one of the most complete in the West, but for its size one of the finest in the world.”

The two hotels were related only by name, and there is no solid evidence that the one in Boise was named after the Soda Springs Idanha. Developers likely knew about the first hotel, which had a good reputation at the time, so, why not borrow the name? The first Idanha had borrowed its name, after all. The moniker first appeared on the labels of Idanha Mineral Water, bottled in Soda Springs and sold all over the United States. But, let’s leave the Soda Springs hotel, which burned down in 1921, and get back to Boise’s grand hotel.

As the preferred place to stay in town for decades, the Idanha saw a lot of history. Walter “Big Train” Johnson, years before his induction into baseball’s hall of fame, practiced pitches in the hallway of the Idanha, shattering an inconveniently placed chamber pot with one low pitch.

Movie star Ethel Barrymore stayed there while attending the high-profile Haywood trial. “Big Bill” Haywood, a leader of the International Workers of the World was on trial for hiring Harry Orchard to assassinate Frank Steunenberg, a former Idaho governor who had clashed with the union. It was Clarence Darrow for the defense.

The Idanha came close to being the site of the assassination, until Harry Orchard had second thoughts about the bomb he had placed under Steunenberg’s bed. He disconnected the device because he feared it might injure or kill a chambermaid. Orchard planted another bomb at the gate of the former governor’s home in Caldwell to complete the job.

Famous folks who stayed at the Idanha included William Jennings Bryan, Sally Rand, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Polly Bemis. The legendary little Chinese woman who lived in the Salmon River country got her first elevator ride there.

And, since there’s always a remote chance someone may consider me famous one day, I must mention that I got to stay in a second-floor turret room courtesy of the federal government the night before I was inducted into the Marine Corps. It was easily the best part of that experience.

The Idanha is no longer a hotel. In recent years it was converted into an apartment building with 80 small apartments ranging in size from 380 to 786 square feet. That historic elevator has been giving tenants and management grief in recent years, becoming increasing unreliable.

From the outside the Idanha looks much the same as the day it opened. Though Vardis Fisher wrote in his 1936 guide to Boise, published only recently, “nobody finds it beautiful today,” that opinion about the Idanha is likely a minority one in 2020.

The Idanha in 1979. Photo by Leo J. "Scoop" Leeburn, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

The Idanha in 1979. Photo by Leo J. "Scoop" Leeburn, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

Published on May 22, 2020 04:00

May 21, 2020

Fake News, 1831 Style

Alas, fake news is not new.

Here’s what we know:

In 1831, four Nez Perce arrived in St. Louis seeking a man the tribe had met 25 years earlier, William Clark. What they sought wasn’t entirely clear, because the only person who knew any words in the language of the Nez Perce was Clark, and he didn’t remember much from that long-ago expedition. We also know that a few weeks after their arrival, the two older men, Black Eagle and Speaking Eagle, became ill and died, though not before being baptized by Catholics. Their younger companions stayed the winter and left for home the following spring aboard the steamer Yellowstone on its way up the Missouri River. At some point on that trip, George Catlin painted the surviving men (below), who were in their 20s. In the Catlin images below that is No Horns on His Head on the left and Rabbit Skin Leggings on the right. No Horns on His Head succumbed to disease on the trip home. Rabbit Skin Leggings may have made it back, or he may have been killed by Blackfeet before reaching home.

Here’s what’s fishy:

FISH TALE ONE. The journey the men made is fuzzily famous, mostly because of two accounts of their visit. The first was given by William Walker and quoted in the March 1, 1833, edition of the Christian Advocate by his friend G.P. Disoway, the secretary of the Methodist Board of Foreign Missions. Walker described meeting three of the Indians in St. Louis, and he told of their overwhelming desire to secure a copy of “a book containing directions of how to conduct themselves” that members of the Corps of Discovery had talked about when they met the Nez Perce. Disoway argued that the Indians were clearly seeking the wisdom of the Bible.

Walker, who allegedly met the Indians, went on to describe them in detail. He said they were “small in size, delicately formed, small hands, and the most exact symmetry throughout, except the head.” The unusual thing about their heads, you see, was that their foreheads had been flattened and sloped radically back in the manner of the Flathead people.

There are several points that make this story difficult to swallow. First, recall that no one knew the language of the Nez Perce so communication of complex concepts would have been difficult. Next, they were Nez Perce, not Flatheads, and the “Flatheads” didn’t practice the head flattening custom in the first place. The rest of Walker’s description was also wrong, as the men were not small and delicate at all. Finally, records show that Walker was not in St. Louis at the time of the visit, so could not have met them.

FISH TALE TWO. An unidentified man supposedly overheard a little speech given by one of the Nez Perce when they left St. Louis. In part, it reads, “I came to you, the Great Father of white men, but with one eye partly opened. I am to return to my people, beyond the mountains of snow, at the setting sun, with both eyes in darkness and both arms broken. I came for teachers and am going back without them. I came to you for the Book of God. You have not led me to it… And I am to return to my people to die in darkness.”

The speech reads like the trumped-up eloquence of a storyteller, not like the words of a young man who could not speak English. Also, if they could make their wishes known so plainly, why didn’t someone just give them a Bible? The question of how they were hoping to read it might come up, but surely Bibles were not in short supply in St. Louis.

Whatever reason the Nez Perce delegation had for seeking William Clark in St. Louis (he didn’t bother to mention the visit in his journals), the myth that grew up around it had an important effect. It triggered the missionary movement to the West, starting with the Spaldings and Whitmans leaving in 1836 to make their missions in Oregon Country (present-day Idaho and Washington State).

Here’s what we know:

In 1831, four Nez Perce arrived in St. Louis seeking a man the tribe had met 25 years earlier, William Clark. What they sought wasn’t entirely clear, because the only person who knew any words in the language of the Nez Perce was Clark, and he didn’t remember much from that long-ago expedition. We also know that a few weeks after their arrival, the two older men, Black Eagle and Speaking Eagle, became ill and died, though not before being baptized by Catholics. Their younger companions stayed the winter and left for home the following spring aboard the steamer Yellowstone on its way up the Missouri River. At some point on that trip, George Catlin painted the surviving men (below), who were in their 20s. In the Catlin images below that is No Horns on His Head on the left and Rabbit Skin Leggings on the right. No Horns on His Head succumbed to disease on the trip home. Rabbit Skin Leggings may have made it back, or he may have been killed by Blackfeet before reaching home.

Here’s what’s fishy:

FISH TALE ONE. The journey the men made is fuzzily famous, mostly because of two accounts of their visit. The first was given by William Walker and quoted in the March 1, 1833, edition of the Christian Advocate by his friend G.P. Disoway, the secretary of the Methodist Board of Foreign Missions. Walker described meeting three of the Indians in St. Louis, and he told of their overwhelming desire to secure a copy of “a book containing directions of how to conduct themselves” that members of the Corps of Discovery had talked about when they met the Nez Perce. Disoway argued that the Indians were clearly seeking the wisdom of the Bible.

Walker, who allegedly met the Indians, went on to describe them in detail. He said they were “small in size, delicately formed, small hands, and the most exact symmetry throughout, except the head.” The unusual thing about their heads, you see, was that their foreheads had been flattened and sloped radically back in the manner of the Flathead people.

There are several points that make this story difficult to swallow. First, recall that no one knew the language of the Nez Perce so communication of complex concepts would have been difficult. Next, they were Nez Perce, not Flatheads, and the “Flatheads” didn’t practice the head flattening custom in the first place. The rest of Walker’s description was also wrong, as the men were not small and delicate at all. Finally, records show that Walker was not in St. Louis at the time of the visit, so could not have met them.

FISH TALE TWO. An unidentified man supposedly overheard a little speech given by one of the Nez Perce when they left St. Louis. In part, it reads, “I came to you, the Great Father of white men, but with one eye partly opened. I am to return to my people, beyond the mountains of snow, at the setting sun, with both eyes in darkness and both arms broken. I came for teachers and am going back without them. I came to you for the Book of God. You have not led me to it… And I am to return to my people to die in darkness.”

The speech reads like the trumped-up eloquence of a storyteller, not like the words of a young man who could not speak English. Also, if they could make their wishes known so plainly, why didn’t someone just give them a Bible? The question of how they were hoping to read it might come up, but surely Bibles were not in short supply in St. Louis.

Whatever reason the Nez Perce delegation had for seeking William Clark in St. Louis (he didn’t bother to mention the visit in his journals), the myth that grew up around it had an important effect. It triggered the missionary movement to the West, starting with the Spaldings and Whitmans leaving in 1836 to make their missions in Oregon Country (present-day Idaho and Washington State).

Published on May 21, 2020 04:00

May 20, 2020

The Winchester Name

The origin of town names in Idaho provides occasional fodder for these postings. One of the better-known stories is about the town of Winchester. That’s because the town makes a point of telling it, with an over-sized model of a Winchester rifle hanging across one of their streets.

In any case, the story goes that when it came to naming the town someone decided to choose the moniker by counting the number of rifles bearing brand names and go with the most popular rifle brand. If there remains a tally to tell us how close the town came to being called Remington, I’m not aware of it.

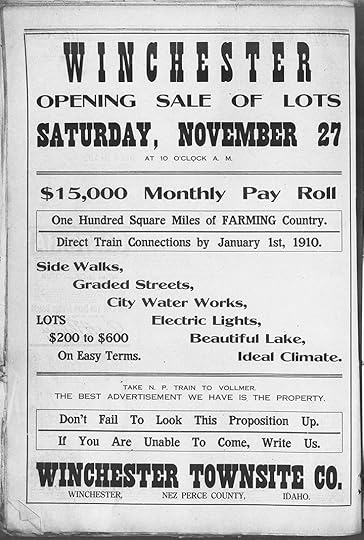

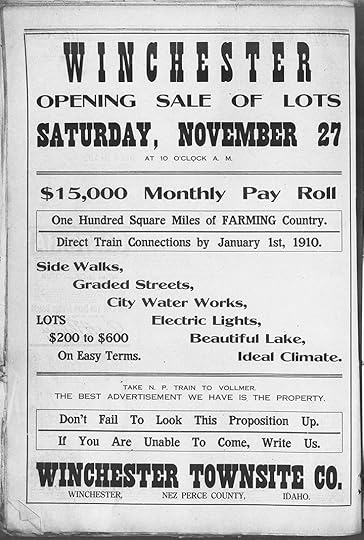

The image below is from the November 26, 1909 edition of the Camas County Chronicle announcing the irresistible lots available in the newly named (1908) town of Winchester.

#winchester #winchesterlake #winchesteridaho

In any case, the story goes that when it came to naming the town someone decided to choose the moniker by counting the number of rifles bearing brand names and go with the most popular rifle brand. If there remains a tally to tell us how close the town came to being called Remington, I’m not aware of it.

The image below is from the November 26, 1909 edition of the Camas County Chronicle announcing the irresistible lots available in the newly named (1908) town of Winchester.

#winchester #winchesterlake #winchesteridaho

Published on May 20, 2020 04:00

May 19, 2020

Meet William Orville Casey, a blind man with great sight

On September 12, 1906, Governor Frank Gooding decided to stop in to pay a visit to the students of the brand-new Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind in Gooding. The town of Gooding as well as the county of Gooding were both named after the governor. As it turned out, one of the students he greeted that day, a 7-year-old blind boy from the Treasure Valley named William Orville Casey, would one day be honored in a similar way.

Casey, who went by Orville most of his life, was blinded at age 4 when he got typhoid fever. He was in the first class at the new school, learning to get along without his sight.

Orville became a fine judge of animals, especially the milk cows he purchased for his dairy in Ustick, near McMillan and Maple Grove. When it came time to buy a cow the auctioneer at the local sales yard allowed Casey to get into the ring with a prospective animal, back it into a corner, and feel along its body to determine its quality. This wasn’t just for show. Lewis W. Morely, national secretary of the American Jersey Cattle Club, came to Boise in 1939 and visited the Casey dairy. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying, “This man has accomplished through his fingertips the ability to expertly judge a fine cow. Individual animals in his Jersey herd compare favorably with some of the best cows in the larger herds.” Casey’s cows proved his skill by winning many ribbons at the fair.

His visits to the auction ring gave Casey an idea for a little business that would serve him well over the years. He set up a card table with snacks for sale to auction goers. He knew coins by size and weight and trusted buyers when they told him the denomination of a bill. He claimed he could tell if they were lying by the tone of their voice.

He ran his dairy from 1923 to 1952. That’s when he took his small concession business to the Idaho statehouse. Casey purchased a small booth inside the capitol and opened what would become known as Casey’s Corner. He became a favorite with elected officials and visitors during the Legislative session. His grandson, Greg Casey, remembers helping out by taking coffee up to the second floor many times for Governor Robert E. Smylie.

Orville Casey retired from his concession stand at age 65 in 1964. He kept busy gardening — demonstrating an amazing ability to distinguish between weeds and vegetables — and started a wood cutting business.

Sighted folks marveled at his business and farming skills. Those in the blind community recognized him for many years of leadership. Orville Casey was the long-time president of the Idaho Society of the Blind, hosting annual picnics at his farm during the organization’s conventions.

In 1975, Governor Cecil Andrus presided over a ceremony naming the new high school building at the Idaho State School for the Deaf and Blind the Casey building. With remodeling and new construction, it has become the Casey Wing today, honoring the first blind graduate of the school.

William Orville Casey died in 1986 and is buried at the Joplin Pioneer Cemetery in Meridian.

Orville Casey, though blind from age four, new his way around animals. That's him riding on his horse at his Ustick farm.

Orville Casey, though blind from age four, new his way around animals. That's him riding on his horse at his Ustick farm.

Casey, who went by Orville most of his life, was blinded at age 4 when he got typhoid fever. He was in the first class at the new school, learning to get along without his sight.

Orville became a fine judge of animals, especially the milk cows he purchased for his dairy in Ustick, near McMillan and Maple Grove. When it came time to buy a cow the auctioneer at the local sales yard allowed Casey to get into the ring with a prospective animal, back it into a corner, and feel along its body to determine its quality. This wasn’t just for show. Lewis W. Morely, national secretary of the American Jersey Cattle Club, came to Boise in 1939 and visited the Casey dairy. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying, “This man has accomplished through his fingertips the ability to expertly judge a fine cow. Individual animals in his Jersey herd compare favorably with some of the best cows in the larger herds.” Casey’s cows proved his skill by winning many ribbons at the fair.

His visits to the auction ring gave Casey an idea for a little business that would serve him well over the years. He set up a card table with snacks for sale to auction goers. He knew coins by size and weight and trusted buyers when they told him the denomination of a bill. He claimed he could tell if they were lying by the tone of their voice.

He ran his dairy from 1923 to 1952. That’s when he took his small concession business to the Idaho statehouse. Casey purchased a small booth inside the capitol and opened what would become known as Casey’s Corner. He became a favorite with elected officials and visitors during the Legislative session. His grandson, Greg Casey, remembers helping out by taking coffee up to the second floor many times for Governor Robert E. Smylie.

Orville Casey retired from his concession stand at age 65 in 1964. He kept busy gardening — demonstrating an amazing ability to distinguish between weeds and vegetables — and started a wood cutting business.

Sighted folks marveled at his business and farming skills. Those in the blind community recognized him for many years of leadership. Orville Casey was the long-time president of the Idaho Society of the Blind, hosting annual picnics at his farm during the organization’s conventions.

In 1975, Governor Cecil Andrus presided over a ceremony naming the new high school building at the Idaho State School for the Deaf and Blind the Casey building. With remodeling and new construction, it has become the Casey Wing today, honoring the first blind graduate of the school.

William Orville Casey died in 1986 and is buried at the Joplin Pioneer Cemetery in Meridian.

Orville Casey, though blind from age four, new his way around animals. That's him riding on his horse at his Ustick farm.

Orville Casey, though blind from age four, new his way around animals. That's him riding on his horse at his Ustick farm.

Published on May 19, 2020 15:22

May 18, 2020

The Wealthiest Woman in the World

On Sunday, August 20, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran a full-page story with nine photos about a place in Island Park that was hosting a special guest, the “wealthiest woman in the world.” It was the first time Mrs. E.H. (Mary) Harriman would visit the state, but it would not be the last.

E.H. Harriman, “the biggest little railroad man the world had known,” had died in 1909, shortly after purchasing shares in the Island Park Land and Cattle Company. The place was already being called the Railroad Ranch because the men who bought the first 3,000 acres of the property in 1899 were associated with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Harriman, who ran Union Pacific Railroad, solidified that name with his purchase.

The article mentions, without naming them, that Mary Harriman’s sons came along with her. It would be those sons who had the most impact on Idaho, Averell by creating the Sun Valley Resort, and E. Roland by ultimately donating the Railroad Ranch to the State of Idaho to create Harriman State Park of Idaho (the latter two words in the name to distinguish it from Harriman State Park in New York).

The wealth of the Harrimans, the Guggenheims, and other investors did not escape the notice of the unnamed Statesman reporter, who wrote, “it is said that there is more wealth represented during the summer at Island Park than at any other point in the United States outside of Wall Street and Newport.”

Mrs. Harriman fell in love with the place, as did Averell and Roland.

The reporter predicted the future, when he (probably not she) wrote, “The world is open to Mrs. Harriman, but she selected Island Park as the place to spend her summer vacation in 1911; and it is an open secret that she will return next year and the next and indefinitely.”

Over the years there was no shortage of grousing from sportsmen and anglers who felt locked out of the Railroad Ranch, but ultimately saving this jewel of the Gem State was well worth it.

E.H. Harriman, “the biggest little railroad man the world had known,” had died in 1909, shortly after purchasing shares in the Island Park Land and Cattle Company. The place was already being called the Railroad Ranch because the men who bought the first 3,000 acres of the property in 1899 were associated with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Harriman, who ran Union Pacific Railroad, solidified that name with his purchase.

The article mentions, without naming them, that Mary Harriman’s sons came along with her. It would be those sons who had the most impact on Idaho, Averell by creating the Sun Valley Resort, and E. Roland by ultimately donating the Railroad Ranch to the State of Idaho to create Harriman State Park of Idaho (the latter two words in the name to distinguish it from Harriman State Park in New York).

The wealth of the Harrimans, the Guggenheims, and other investors did not escape the notice of the unnamed Statesman reporter, who wrote, “it is said that there is more wealth represented during the summer at Island Park than at any other point in the United States outside of Wall Street and Newport.”

Mrs. Harriman fell in love with the place, as did Averell and Roland.

The reporter predicted the future, when he (probably not she) wrote, “The world is open to Mrs. Harriman, but she selected Island Park as the place to spend her summer vacation in 1911; and it is an open secret that she will return next year and the next and indefinitely.”

Over the years there was no shortage of grousing from sportsmen and anglers who felt locked out of the Railroad Ranch, but ultimately saving this jewel of the Gem State was well worth it.

Published on May 18, 2020 04:00

May 17, 2020

Sunday Rest

I did the research for this post on a Sunday. I wrote it on another Sunday. It appeared on yet another Sunday as a column in the Idaho Press and on a Sunday today. Does that make me a scofflaw?

No, not in 2020. In 1907 the answer would not have been so clear.

Many Idahoans would rather the state name not even appear in the same sentence as California. It will appear that way here, twice. Idaho and California were the last two states in the nation that did not have a Sunday Rest law on the books in 1907. That was soon to change.

Sunday Rest laws were put in statute to codify a day of rest from secular labor. The International Reform Bureau was a group promoting such laws nationwide, and Idaho was in their sights. Dr. G.L. Tufts, of Portland, was the group’s lead lobbyist. He took his job seriously enough to get arrested for it.

Dr. Tufts became the first to test a law then recently passed by the Idaho Legislature that prohibited lobbying in the statehouse. Tufts was arrested on a Wednesday after repeated warnings that his conversations with lawmakers were prohibited. Presiding over the case a Justice Savidge released the man that Friday on the grounds that “Your thought (was) kindly and brotherly, nothing else, and your motive philanthropic. Your intention was far from anything criminal and you may go on your way.”

The law prohibiting lobbying didn’t last, perhaps due in part to this quick dismissal.

The bill Dr. Tufts lobbied for got considerable support from the citizenry in the form of petitions. As a sample, there were 41 signatures from St. Anthony, 126 from Boise, and, notably, 310 from Kellogg. The Silver Valley, which includes Kellogg, was deeply torn by the proposed law. Mine owners pointed out the hardship of shutting down their operations one day each week and missing out on the soaring silver prices at the time. Bar owners, especially in Wallace, openly vowed to flout the law if it passed.

It passed, and now it was up to law enforcement to see that citizens adhered to it. Whatever that meant. These days Pandora is a music streaming service. Back then it was a proverbial box filled with squirming issues released upon passage of the Sunday Rest law. If people couldn’t gather for a play on Sunday, could they gather at church? Most agreed they could, but in Boise the line between entertainment and religion was blurred when the county prosecutor shut down a Passion Play on a Sunday at the YMCA for violating the law.

As Jimmy Buffett once sang, “There’s a thin line between Saturday night and Sunday morning.” True to their word, bar owners in Wallace refused to shut down when Saturday nights rolled into the wee hours of Sunday. They were arrested and rearrested. They tried closing up the front of their establishments and sneaking people in the back.

Enforcement of the law was often lax. When three saloon keepers in Cottonwood stood trial, they were sentenced to spend one minute in the county jail at Grangeville.

In Boise the manager of Riverside Park was arrested for showing a theatrical production on a Sunday. The law specified a $100 fine for such an affront. Other Boiseans were arrested for operating a shoeshining stand, running a steam bath, and for selling produce. The prosecutor in Ada County got complaints about the Boise Commercial club and the Elks’ club conducting business over the bar on Sundays. He determined that since they were private enterprises the law did not apply.

And that was the rub. Deciding when the law applied and when it didn’t became an endless question. The manager at the Natatorium and the White City Amusement Park made his own determination about what could operate and what couldn’t. Predictably he guessed wrong, at least according to the Ada County Prosecutor.

In July of 1910, the Nat manager, G.W. Hull was arrested for running a scenic railroad around the White City Amusement Park on a Sunday. An immediate uproar commenced, with people questioning the fairness of arresting a train operator while leaving operators of the Interurban trolley line free to take people all around the valley on scenic excursions.

The scenic railroad arrest became a test case that went to the Idaho Supreme Court. The court ruled in favor of Hull, stating that amusements not “immoral, corrupt or boisterous” did not break the law.

Interpretations and misinterpretations continued for years with enforcement growing increasingly lax. The Idaho Legislature finally repealed the Sunday Rest law in 1939. So, today you’re welcome to go to church, watch a Passion Play—or any kind of play—as well as put in a hard day’s labor. You’re also welcome to rest.

The manager of the Natatorium Park Amusement Company got a warning before his arrest for violating Idaho’s Sunday Rest law. Image from the Bob Hartman Collection.

The manager of the Natatorium Park Amusement Company got a warning before his arrest for violating Idaho’s Sunday Rest law. Image from the Bob Hartman Collection.

No, not in 2020. In 1907 the answer would not have been so clear.

Many Idahoans would rather the state name not even appear in the same sentence as California. It will appear that way here, twice. Idaho and California were the last two states in the nation that did not have a Sunday Rest law on the books in 1907. That was soon to change.

Sunday Rest laws were put in statute to codify a day of rest from secular labor. The International Reform Bureau was a group promoting such laws nationwide, and Idaho was in their sights. Dr. G.L. Tufts, of Portland, was the group’s lead lobbyist. He took his job seriously enough to get arrested for it.

Dr. Tufts became the first to test a law then recently passed by the Idaho Legislature that prohibited lobbying in the statehouse. Tufts was arrested on a Wednesday after repeated warnings that his conversations with lawmakers were prohibited. Presiding over the case a Justice Savidge released the man that Friday on the grounds that “Your thought (was) kindly and brotherly, nothing else, and your motive philanthropic. Your intention was far from anything criminal and you may go on your way.”

The law prohibiting lobbying didn’t last, perhaps due in part to this quick dismissal.

The bill Dr. Tufts lobbied for got considerable support from the citizenry in the form of petitions. As a sample, there were 41 signatures from St. Anthony, 126 from Boise, and, notably, 310 from Kellogg. The Silver Valley, which includes Kellogg, was deeply torn by the proposed law. Mine owners pointed out the hardship of shutting down their operations one day each week and missing out on the soaring silver prices at the time. Bar owners, especially in Wallace, openly vowed to flout the law if it passed.

It passed, and now it was up to law enforcement to see that citizens adhered to it. Whatever that meant. These days Pandora is a music streaming service. Back then it was a proverbial box filled with squirming issues released upon passage of the Sunday Rest law. If people couldn’t gather for a play on Sunday, could they gather at church? Most agreed they could, but in Boise the line between entertainment and religion was blurred when the county prosecutor shut down a Passion Play on a Sunday at the YMCA for violating the law.

As Jimmy Buffett once sang, “There’s a thin line between Saturday night and Sunday morning.” True to their word, bar owners in Wallace refused to shut down when Saturday nights rolled into the wee hours of Sunday. They were arrested and rearrested. They tried closing up the front of their establishments and sneaking people in the back.

Enforcement of the law was often lax. When three saloon keepers in Cottonwood stood trial, they were sentenced to spend one minute in the county jail at Grangeville.

In Boise the manager of Riverside Park was arrested for showing a theatrical production on a Sunday. The law specified a $100 fine for such an affront. Other Boiseans were arrested for operating a shoeshining stand, running a steam bath, and for selling produce. The prosecutor in Ada County got complaints about the Boise Commercial club and the Elks’ club conducting business over the bar on Sundays. He determined that since they were private enterprises the law did not apply.

And that was the rub. Deciding when the law applied and when it didn’t became an endless question. The manager at the Natatorium and the White City Amusement Park made his own determination about what could operate and what couldn’t. Predictably he guessed wrong, at least according to the Ada County Prosecutor.

In July of 1910, the Nat manager, G.W. Hull was arrested for running a scenic railroad around the White City Amusement Park on a Sunday. An immediate uproar commenced, with people questioning the fairness of arresting a train operator while leaving operators of the Interurban trolley line free to take people all around the valley on scenic excursions.

The scenic railroad arrest became a test case that went to the Idaho Supreme Court. The court ruled in favor of Hull, stating that amusements not “immoral, corrupt or boisterous” did not break the law.

Interpretations and misinterpretations continued for years with enforcement growing increasingly lax. The Idaho Legislature finally repealed the Sunday Rest law in 1939. So, today you’re welcome to go to church, watch a Passion Play—or any kind of play—as well as put in a hard day’s labor. You’re also welcome to rest.

The manager of the Natatorium Park Amusement Company got a warning before his arrest for violating Idaho’s Sunday Rest law. Image from the Bob Hartman Collection.

The manager of the Natatorium Park Amusement Company got a warning before his arrest for violating Idaho’s Sunday Rest law. Image from the Bob Hartman Collection.

Published on May 17, 2020 04:00

May 16, 2020

Pocatello's Standrod Mansion

One of Idaho’s most beautiful homes is the Standrod Mansion in Pocatello. Bonus: It may be haunted.

Drew W. Standrod was a lawyer in Malad City, Idaho in 1890 when he became a member of Idaho’s constitutional convention. He was later elected Fifth Judicial District State Judge. His district covered what are now the counties of Oneida, Bannock, Bingham, Fremont, Lemhi, Custer, and Bear Lake. In 1895 he and his family moved to Pocatello to be more centrally located in his district. He served as a judge until 1899 when he went into private practice in Pocatello.

Standrod was also a financier, serving on the boards of the Standrod and Company Bank in Blackfoot, and the J.N. Ireland and Company Bank in Malad. Those banks led to the creation of banks still well-known in Idaho, Ireland Bank and D.L. Evans Bank. Standrod was also a partner in the Yellowstone Hotel in Pocatello.

D.W. Standrod became a member of Idaho’s first Public Utilities Commission and as such wrote much of the irrigation and water rights law in use today.

Lest one think that he was a success at everything, it should be noted that he ran for a seat on the Idaho Supreme Court and for governor of the state, losing in both campaigns.

Emma Standrod, his wife, was a school principal and founder of the Wyeth Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was active in historical preservation and the Red Cross.

The Standrods built their mansion in 1902 using mostly local materials. The two-story home is one of only a few in the state built in the Châteauesque style, a revival style based on the French Renaissance architecture of the monumental French country houses. The prominent corner tower gives the home a castle-like—some might say forbidding—appearance. It would not be out of place in a Charles Addams cartoon from the New Yorker. Perhaps that bolsters the ghost stories attached to the mansion.

Legend has it that daughter Cammie Standrod, distraught over the disappearance of a boyfriend her father did not approve of, died in that iconic tower. She is said to have had a kidney disease and in her weakened state caught a cold that proved her demise. Cammie is the star of most stories of haunting, though some mention the ghostly image of an elderly man, perhaps D.W. himself, who also died in his mansion.

Though the City of Pocatello owned the home for about 20 years, the Standrod Mansion is now a private residence.

#standrodmansion #stanrodmansion

Drew W. Standrod was a lawyer in Malad City, Idaho in 1890 when he became a member of Idaho’s constitutional convention. He was later elected Fifth Judicial District State Judge. His district covered what are now the counties of Oneida, Bannock, Bingham, Fremont, Lemhi, Custer, and Bear Lake. In 1895 he and his family moved to Pocatello to be more centrally located in his district. He served as a judge until 1899 when he went into private practice in Pocatello.

Standrod was also a financier, serving on the boards of the Standrod and Company Bank in Blackfoot, and the J.N. Ireland and Company Bank in Malad. Those banks led to the creation of banks still well-known in Idaho, Ireland Bank and D.L. Evans Bank. Standrod was also a partner in the Yellowstone Hotel in Pocatello.

D.W. Standrod became a member of Idaho’s first Public Utilities Commission and as such wrote much of the irrigation and water rights law in use today.

Lest one think that he was a success at everything, it should be noted that he ran for a seat on the Idaho Supreme Court and for governor of the state, losing in both campaigns.

Emma Standrod, his wife, was a school principal and founder of the Wyeth Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was active in historical preservation and the Red Cross.

The Standrods built their mansion in 1902 using mostly local materials. The two-story home is one of only a few in the state built in the Châteauesque style, a revival style based on the French Renaissance architecture of the monumental French country houses. The prominent corner tower gives the home a castle-like—some might say forbidding—appearance. It would not be out of place in a Charles Addams cartoon from the New Yorker. Perhaps that bolsters the ghost stories attached to the mansion.

Legend has it that daughter Cammie Standrod, distraught over the disappearance of a boyfriend her father did not approve of, died in that iconic tower. She is said to have had a kidney disease and in her weakened state caught a cold that proved her demise. Cammie is the star of most stories of haunting, though some mention the ghostly image of an elderly man, perhaps D.W. himself, who also died in his mansion.

Though the City of Pocatello owned the home for about 20 years, the Standrod Mansion is now a private residence.

#standrodmansion #stanrodmansion

Published on May 16, 2020 04:00

May 15, 2020

Remember Haircuts?

Famous men and women get all the ink. People who never did anything worthy of a history book should get an occasional mention. That’s my mission today as I tell you about Harold Brighton, a man famous only in Firth.

Harold was the town barber for many years, working out of a tiny one-chair shop on Main Street. You could sit in the leather seat—or on the board placed across the arms if you were a little kid—and stare into infinity as your image bounced forth and back between the big mirrors on facing walls. The marble shelves beneath the mirror behind Harold were like a barback, bottles of various tonics and smell-goods sparkling in their reflections.

Those waiting for their haircut spent their time in chairs borrowed from an abandoned theater. They could read comics or mild men’s magazines. Mostly they talked about weather and farming.

The thing Harold will always be remembered for was his nickel rebate. It happened to be a pair of my cousins, Charlie and Frank Just, who as rambunctious kids started the tradition. They were bouncing around one day under the control of no one, their dad likely down the street at the drugstore or talking with someone at the International Harvester dealership nearby.

With no adult supervision handy, Harold bribed the kids. He offered them each a nickel to go get an ice cream cone after their haircut, if they’d sit still and be quiet. That was the best deal they’d heard all day, so the brothers were good as gold.

Harold might have forgotten about the nickels, but the Just kids didn’t. They expected it the next time they came in for their $1 haircuts. Further, they spread the word about the sit-still bribe among all their friends. Harold was on the hook for ice cream nickels from then on.

The tradition became so expected that some parents tried giving Harold 95 cents instead of the posted price of one dollar. Harold wouldn’t have it. Haircuts were a buck. The nickel belonged to a kid who worked hard at sitting still.

Harold Brighton often said that he could have bought a Cadillac with all the nickels he gave away over the years.

When Harold closed up shop and retired, my son, Jarad, was just about ready for his first haircut. I talked Harold into opening up the shop one more time so I could get the picture below of Jarad’s first haircut, and Harold’s last. It’s one of many treasured memories I have of a man famous only in Firth.

Harold was the town barber for many years, working out of a tiny one-chair shop on Main Street. You could sit in the leather seat—or on the board placed across the arms if you were a little kid—and stare into infinity as your image bounced forth and back between the big mirrors on facing walls. The marble shelves beneath the mirror behind Harold were like a barback, bottles of various tonics and smell-goods sparkling in their reflections.

Those waiting for their haircut spent their time in chairs borrowed from an abandoned theater. They could read comics or mild men’s magazines. Mostly they talked about weather and farming.

The thing Harold will always be remembered for was his nickel rebate. It happened to be a pair of my cousins, Charlie and Frank Just, who as rambunctious kids started the tradition. They were bouncing around one day under the control of no one, their dad likely down the street at the drugstore or talking with someone at the International Harvester dealership nearby.

With no adult supervision handy, Harold bribed the kids. He offered them each a nickel to go get an ice cream cone after their haircut, if they’d sit still and be quiet. That was the best deal they’d heard all day, so the brothers were good as gold.

Harold might have forgotten about the nickels, but the Just kids didn’t. They expected it the next time they came in for their $1 haircuts. Further, they spread the word about the sit-still bribe among all their friends. Harold was on the hook for ice cream nickels from then on.

The tradition became so expected that some parents tried giving Harold 95 cents instead of the posted price of one dollar. Harold wouldn’t have it. Haircuts were a buck. The nickel belonged to a kid who worked hard at sitting still.

Harold Brighton often said that he could have bought a Cadillac with all the nickels he gave away over the years.

When Harold closed up shop and retired, my son, Jarad, was just about ready for his first haircut. I talked Harold into opening up the shop one more time so I could get the picture below of Jarad’s first haircut, and Harold’s last. It’s one of many treasured memories I have of a man famous only in Firth.

Published on May 15, 2020 04:00