Rick Just's Blog, page 165

April 14, 2020

Forts Here and There

This 1849 lithograph shows Fort Boise, the trading post near Parma, in its prime. It fell into disuse in 1853 after flooding and Indian troubles. One of the most confusing things about Idaho history is keeping track of the entangled relationship of two southern Idaho institutions called Fort Hall and Fort Boise. Fort Hall came first, and its creation led almost immediately to the creation of Fort Boise.

This 1849 lithograph shows Fort Boise, the trading post near Parma, in its prime. It fell into disuse in 1853 after flooding and Indian troubles. One of the most confusing things about Idaho history is keeping track of the entangled relationship of two southern Idaho institutions called Fort Hall and Fort Boise. Fort Hall came first, and its creation led almost immediately to the creation of Fort Boise.Neither fort had a military connection at first. Neither was much of a fort. Fort Boise was a collection of sticks and poles cobbled into an enclosure about 100 feet square. Within the enclosure were a handful of shacks built of the same materials, almost as if nesting birds designed the whole thing. Fort Hall was, arguably, a little better structure in the beginning, with palisade walls enclosing a few cabins.

In the 1830s Britain and the United States were quibbling over where the border should be in what we today call the Pacific Northwest. So, it was significant when Nathanial Wyeth established a trading post along the Snake River near its confluence with the Portneuf. Fort Hall, near present day Pocatello, was named after Hall J. Kelley, who had recruited Wyeth to go west to establish a trading post. When Wyeth tamped the posts in that palisade wall down and opened the gates for business, Fort Hall became the only outpost with ties to the United States in Oregon country.

The British Hudson’s Bay Company saw Fort Hall as a challenge to their trading dominance in the region, so in the fall of 1834, they patched together a trading post near the confluence of the Snake and Boise rivers, taking the name of the latter for their Fort Boise. Francois Payette ran Fort Boise until 1844, mostly with a “staff” of traders from Hawaii. After a few years Payette moved the operation to another nearby site and constructed a much more substantial post, eventually surrounding it with sun-dried adobe brick.

Wyeth and his operation, meanwhile, lasted only until 1837, when he sold Fort Hall and a second trading post he had built on the Columbia, to the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The US settled the boundary dispute with the British in 1846, establishing the border we know today between Washington and Canada. That opened up a torrent of settlers headed west into Oregon Country. Both forts became important replenishment points for emigrants. Fort Boise was famous for welcoming Oregon Trail travelers and providing them with needed provisions.

Fort Boise, the trading post near present day Parma, fell into disuse in 1853 after flooding and Indian troubles. The original Fort Hall fell to a flood in 1863. A nearby replacement served emigrants for a few more years.

So, both forts, Hall and Boise, operated from about 1834, mostly as trading posts from about their original locations. Then it got confusing.

The military established the new Fort Boise in 1863 along the foothills north of the Boise River. The town of Boise sprung up below the fort.

In 1870, the US Army established a military post near the Blackfoot River about 25 miles from old Fort Hall. Rather than name the new post after some forgotten general, they called that one Fort Hall, too. In order to completely perplex students of history, the main town on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation also became Fort Hall. Then, to better tell the story of Fort Hall, history enthusiasts built a faithful replica of old Fort Hall near the zoo in Pocatello.

So, if someone mentions Fort Hall, ask them which one they’re referencing. Do they mean the reservation, the town, the old fort, the military fort, or the replica?

For Fort Boise, you only have to ask whether they mean the military fort or the trading post. Or, I suppose, the replica, which lurks near the trading post’s original location in Parma.

Published on April 14, 2020 04:00

April 13, 2020

Boise's First Home

Boise became a city in 1863. Remarkably, the first home built in what would become Idaho’s capital city is still standing. The O’Farrell cabin was built from cottonwood trees cut down nearby by John A. O’Farrell in June 1863. O’Farrell used a broad axe to flatten out the logs for his cabin. Branches and clay served as chinking between the logs. Inside, visitors would find a dirt floor and fabric covering the walls.

The following year when bricks and saw-cut lumber became available, O’Farrell improved the cabin by replacing the pole roof with cut rafters and hand-split shingles. He covered the inside walls, floor and ceiling with planks, added a brick fireplace, and installed glass windows.

The O’Farrell family lived in the cabin for seven more years before moving to a brick home.

In 1910 the O’Farrell children donated the old cabin to the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). The DAR moved the home across Fort Street and conducted the first restoration of the little building. Over the years they opened it occasionally for public tours and did some more restoration work. By 1957 the DAR found that it was unable to care for the building, so donated it to the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers. That group erected a roof structure over the entire cabin and installed bars on the windows to protect it.

The City of Boise took ownership of the cabin, and in 1979 the Boise City Historic Preservation Commission did some restoration work. Charles Hummel and the Columbian Club started a fund drive to restore the cabin in 1995. By 2002 the restoration fund was sufficient to bring the cabin back to its 1912 condition, with 85 percent of the original cabin materials still in place.

The following year when bricks and saw-cut lumber became available, O’Farrell improved the cabin by replacing the pole roof with cut rafters and hand-split shingles. He covered the inside walls, floor and ceiling with planks, added a brick fireplace, and installed glass windows.

The O’Farrell family lived in the cabin for seven more years before moving to a brick home.

In 1910 the O’Farrell children donated the old cabin to the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). The DAR moved the home across Fort Street and conducted the first restoration of the little building. Over the years they opened it occasionally for public tours and did some more restoration work. By 1957 the DAR found that it was unable to care for the building, so donated it to the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers. That group erected a roof structure over the entire cabin and installed bars on the windows to protect it.

The City of Boise took ownership of the cabin, and in 1979 the Boise City Historic Preservation Commission did some restoration work. Charles Hummel and the Columbian Club started a fund drive to restore the cabin in 1995. By 2002 the restoration fund was sufficient to bring the cabin back to its 1912 condition, with 85 percent of the original cabin materials still in place.

Published on April 13, 2020 04:00

April 12, 2020

When the One-Eyed Monster Came to Eastern Idaho

Since I hit my 50th birthday, looong ago, I’ve recognized that by most standards I qualify as an antique. Even so, it is a little shocking to be writing about this historical event that was one of my earliest memories.

KID television in Idaho Falls came on the air with programming on Sunday, December 20, 1953. Since I was four it’s remarkable that I remember anything at all about the first television broadcast in southeastern Idaho. But, how could one forget the flamboyant Liberace?

We were watching at my aunt and uncle’s house in Idaho Falls. Pop hadn’t yet sprung for a TV set, though it wouldn’t be long before we had one. I remember the camera panning over the audience and Pop making a comment about some bald guy having less hair than he did.

One of the first mentions of the new TV station came on April 29, 1953, when CBS announced that KID would become its 111th affiliate. The release said they expected to start broadcasting on June 14. Technical issues kept pushing that date out.

With the 100,000 watt transmitter for KID located on one of the Twin Buttes, they expected to get their signal into Twin Falls and the rest of the Magic Valley. Technically, they did, but it was never a signal to brag about.

That didn’t stop stores from stocking televisions in Twin Falls. The Times-News also ran frequent ads suggesting that television repair had a promising future and helpfully giving the address of a school in California.

In Pocatello, they formed the Pocatello Television Dealers Association in anticipation of the big day, listing the programming a week ahead of the first broadcast to entice buyers to come in and shop.

In Blackfoot, Peterson’s, “The store that serves you best,” sold my folks a 17” Philco that seemed like a miracle to me. I watched whatever was on, at first, eventually growing more selective. My favorite was “Disneyland,” which started with Tinkerbell tapping her magic wand to set off sparkles and the opening of stage curtains. After the requisite sponsor blurbs, “When You Wish Upon a Star,” began playing. Other favorites came along, such as “The Cisco Kid,” “Maverick,” and “Sky King.”

KID’s first programming came a dozen years after the first commercial broadcast. That was in 1941 in New York City. But the eastern Idaho event had something earlier broadcasts did not. They had the inventor of television as a guest. Philo T. Farnsworth, who as a freshman at Rigby High School had come up with the concept for the cathode ray tube, helped KID TV celebrate its first broadcast.

IMAGE: When KID TV first went on the air in 1954 the inventor of television was there to help them celebrate. Philo T. Farnsworth had come up with the idea for the cathode ray tube as a freshman at Rigby High School. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A KID TV program guide from 1958, four years after the station aired the first television broadcast in eastern Idaho, courtesy of Frank Aiden.

A KID TV program guide from 1958, four years after the station aired the first television broadcast in eastern Idaho, courtesy of Frank Aiden.

KID television in Idaho Falls came on the air with programming on Sunday, December 20, 1953. Since I was four it’s remarkable that I remember anything at all about the first television broadcast in southeastern Idaho. But, how could one forget the flamboyant Liberace?

We were watching at my aunt and uncle’s house in Idaho Falls. Pop hadn’t yet sprung for a TV set, though it wouldn’t be long before we had one. I remember the camera panning over the audience and Pop making a comment about some bald guy having less hair than he did.

One of the first mentions of the new TV station came on April 29, 1953, when CBS announced that KID would become its 111th affiliate. The release said they expected to start broadcasting on June 14. Technical issues kept pushing that date out.

With the 100,000 watt transmitter for KID located on one of the Twin Buttes, they expected to get their signal into Twin Falls and the rest of the Magic Valley. Technically, they did, but it was never a signal to brag about.

That didn’t stop stores from stocking televisions in Twin Falls. The Times-News also ran frequent ads suggesting that television repair had a promising future and helpfully giving the address of a school in California.

In Pocatello, they formed the Pocatello Television Dealers Association in anticipation of the big day, listing the programming a week ahead of the first broadcast to entice buyers to come in and shop.

In Blackfoot, Peterson’s, “The store that serves you best,” sold my folks a 17” Philco that seemed like a miracle to me. I watched whatever was on, at first, eventually growing more selective. My favorite was “Disneyland,” which started with Tinkerbell tapping her magic wand to set off sparkles and the opening of stage curtains. After the requisite sponsor blurbs, “When You Wish Upon a Star,” began playing. Other favorites came along, such as “The Cisco Kid,” “Maverick,” and “Sky King.”

KID’s first programming came a dozen years after the first commercial broadcast. That was in 1941 in New York City. But the eastern Idaho event had something earlier broadcasts did not. They had the inventor of television as a guest. Philo T. Farnsworth, who as a freshman at Rigby High School had come up with the concept for the cathode ray tube, helped KID TV celebrate its first broadcast.

IMAGE: When KID TV first went on the air in 1954 the inventor of television was there to help them celebrate. Philo T. Farnsworth had come up with the idea for the cathode ray tube as a freshman at Rigby High School. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A KID TV program guide from 1958, four years after the station aired the first television broadcast in eastern Idaho, courtesy of Frank Aiden.

A KID TV program guide from 1958, four years after the station aired the first television broadcast in eastern Idaho, courtesy of Frank Aiden.

Published on April 12, 2020 04:00

April 11, 2020

Escape!, Part Two

We told you about Prisoner Number 2 in Idaho’s Territorial Prison and his first escape attempt yesterday. We’ll continue that story today.

As noted, Moroni Hicks’ status as Prisoner Number 2 doesn’t mean a lot. They didn’t start assigning numbers to prisoners until 1880, 16 years after the first territorial prison opened for business.

After his first escape and recapture a few weeks later, Hicks resigned himself to his fate as a prisoner. For a while.

Then, on a cold day in March 1883, Hicks and three other inmates, who were breaking rocks at the quarry above the prison at Table Rock, rushed their guards and escaped. Besides Hicks there was Charles Chambers, a stage robber; J.W Hayes, serving time for larceny; and Ralph Johnson, a burglar from Wood River. They hightailed it into the hills with captured rifles.

Boise City Marshal Orlando “Rube” Robbins must have been especially aggravated at the escape. Just three years earlier, as a deputy U.S. Marshal, Robbins had chased down Moroni Hicks and some different prisoners who had escaped while picking apples at an orchard next to the prison.

The fugitives this time stopped in at the ranch of Mike McMahan, which was just over the hill from Table Rock, to requisition horses and food. The rancher was livid because they had relieved him of two of his best mounts.

Territorial Governor John Neil put a hundred-dollar reward on the heads of the men. This was a downgrade for Hicks, who at the peak of the hunt for him in the 1880 escape, he was worth $1,000 to anyone who brought him back, breathing or not.

Early on there was a shootout, probably, between the pursuing posse and Hicks and Hayes when they tried to cross the Boise River under cover of darkness. No one was hit, so some of that is speculation.

Meanwhile, Mike McMahan, the rancher, had set out following hoofprints into the Owyhee desert hoping to retrieve his horses. Ten days after he had been robbed, McMahan caught up with escapee Ralph Johnson and a couple of purloined horses on Catherine Creek, which is between Oreana and Grandview. Johnson gave up without a fight and McMahan got his horses back.

In mid-April, Moroni Hicks turned up in Canyon City, Oregon, where he had been arrested in a barroom brawl.

Rube Robbins eventually chased down Charles Chambers in an Oregon Asylum where he was living under an assumed name and pretending to have lost his wits.

J.W. Hayes seems to have vanished completely.

The common thread in these two escapes, Prisoner Number 2, aka Moroni Hicks, was released from prison in August 1891, after serving for eleven years. He married Lucinda Owen in June 1893 in Kane, Utah. They had eight children together. Moroni passed away on March 17, 1931 and is buried in the Oddfellows Cemetery in Los Angeles.

As noted, Moroni Hicks’ status as Prisoner Number 2 doesn’t mean a lot. They didn’t start assigning numbers to prisoners until 1880, 16 years after the first territorial prison opened for business.

After his first escape and recapture a few weeks later, Hicks resigned himself to his fate as a prisoner. For a while.

Then, on a cold day in March 1883, Hicks and three other inmates, who were breaking rocks at the quarry above the prison at Table Rock, rushed their guards and escaped. Besides Hicks there was Charles Chambers, a stage robber; J.W Hayes, serving time for larceny; and Ralph Johnson, a burglar from Wood River. They hightailed it into the hills with captured rifles.

Boise City Marshal Orlando “Rube” Robbins must have been especially aggravated at the escape. Just three years earlier, as a deputy U.S. Marshal, Robbins had chased down Moroni Hicks and some different prisoners who had escaped while picking apples at an orchard next to the prison.

The fugitives this time stopped in at the ranch of Mike McMahan, which was just over the hill from Table Rock, to requisition horses and food. The rancher was livid because they had relieved him of two of his best mounts.

Territorial Governor John Neil put a hundred-dollar reward on the heads of the men. This was a downgrade for Hicks, who at the peak of the hunt for him in the 1880 escape, he was worth $1,000 to anyone who brought him back, breathing or not.

Early on there was a shootout, probably, between the pursuing posse and Hicks and Hayes when they tried to cross the Boise River under cover of darkness. No one was hit, so some of that is speculation.

Meanwhile, Mike McMahan, the rancher, had set out following hoofprints into the Owyhee desert hoping to retrieve his horses. Ten days after he had been robbed, McMahan caught up with escapee Ralph Johnson and a couple of purloined horses on Catherine Creek, which is between Oreana and Grandview. Johnson gave up without a fight and McMahan got his horses back.

In mid-April, Moroni Hicks turned up in Canyon City, Oregon, where he had been arrested in a barroom brawl.

Rube Robbins eventually chased down Charles Chambers in an Oregon Asylum where he was living under an assumed name and pretending to have lost his wits.

J.W. Hayes seems to have vanished completely.

The common thread in these two escapes, Prisoner Number 2, aka Moroni Hicks, was released from prison in August 1891, after serving for eleven years. He married Lucinda Owen in June 1893 in Kane, Utah. They had eight children together. Moroni passed away on March 17, 1931 and is buried in the Oddfellows Cemetery in Los Angeles.

Published on April 11, 2020 04:00

April 10, 2020

Escape!, Part One

When you’re Prisoner Number 2 in the Idaho system, maybe you just try harder. Could that explain Moroni Hicks’ persistence in escaping?

Hicks’ low number—coveted by criminals everywhere—is a little misleading. He was an early prisoner, but many others weren’t assigned a number in the first years of the prison. The Idaho Territorial Prison had been accepting guests since 1864. Hicks checked in in 1880, convicted of second-degree murder.

Moroni Hicks was the third of eight children born to George Armstrong and Elizabeth Temperance Jolley Hicks in Spanish Fork, Utah in 1859. We know little about the murder for which they convicted him, except that the victim was a man named Johnson in Sandhole, which was an early name for Hamer.

Booking photos for Hicks got lost when his prison file was being examined by the attorney general’s office to determine his eligibility for parole. One poor photo of him from later years exists (below). We know he was a large man, but his description varied depending on who was telling the story. When they booked him into the territorial prison, they described Hicks as six feet three and one-fourth inches with a light complexion, grey eyes, and light brown hair. In a later account, he was six-six with red whiskers.

Hicks made his first escape on September 3, 1880, not long after his incarceration. He and five other convicts were picking apples in the Robert Wilson orchard when they rushed their guard and the orchard owner, overpowering them. Five of the prisoners chopped off their shackles, stole some guns, including two shotguns, and a cartridge belt.

The orchard was near the prison. C.W. Newman, a prison guard, heard Mrs. Wilson screaming. He mounted his horse and rode over to investigate. When he got near the house, one of the convicts shot him in the face. As he fell and turned, someone shot him in the back.

Other prison guards had dashed into town to tell of the escape. In minutes a posse formed, including several soldiers from Fort Boise. When the posse arrived at the orchard, they met a fusillade from the house where the Wilsons were now held hostage.

A cavalry corporal took a bullet to his body. Another soldier gave covering fire for his downed comrade and hit convict William Reese. He would die the next day and the corporal would recover. One of the convicts who had failed to cut his chains off and gave up.

That left four men desperate to escape. They were Moroni Hicks and John Wilson, both doing time for manslaughter, and William Mays and W.H. Overholt (or Overholtz) who were in for life for mail robbery.

Somehow, the four convicts slipped away through the orchard to the Boise River. They swam across and found some horses to steal. Wilson took off on his own for Oregon, while the other three headed east.

The next day word of the escapees came back to Boise from travelers on the Overland road. The men had held up six hunters and ranchers at a ranch 40 miles northeast of Boise. That netted them new horses, some mules, blankets, boots, and other provisions. Convict Mays became especially enamored with a new hat he was able to steal. As far as he knew his old one was back in the Boise orchard with a bullet hole through the crown.

The escapees terrorized several people along their route. Meanwhile, U.S. Marshall E.S. Chase was offering a reward for their capture, $1,000, dead or alive.

On their way east the escaped prisoners raided the Glenn home in Glenn’s Ferry, walking off with canned oysters and salmon.

Further east they were spotted by J.W. White at the mouth of Malad Gorge. A brief shootout with White had no apparent effect on anyone. White wrote to Deputy U.S. Marshal Orlando “Rube” Robbins, head of the pursuing posse, that “I am inclined to think we shall have to kill Mays and Overholtz.” He thought Prisoner Number Two, Moroni Hicks, was more interested in escape than a gun fight.

Hard up for food, the escapees had killed an ox a few days before, a piece of which White had seen, describing the meat as “black as my hat.”

What followed was a hunt through the rocky bottom of Malad Gorge, with occasional gunfire. The fugitives had claimed a cave for their own protection. The posse was sure they had them surrounded and that it would all be over at daybreak. Dawn came and what they found was the escapees had sneaked out during the night.

A night or two later their hunger proved to be the fugitives’ undoing. Marshals spotted a guttering little fire inside a ranch corral not far from the gorge. Cold and hungry the men had dug up some potatoes which they were attempting to roast.

Captured with no further resistance, the men were returned to Boise to face new charges. But this would not be the last taste of freedom for Moroni Hicks.

To be continued tomorrow.

Hicks’ low number—coveted by criminals everywhere—is a little misleading. He was an early prisoner, but many others weren’t assigned a number in the first years of the prison. The Idaho Territorial Prison had been accepting guests since 1864. Hicks checked in in 1880, convicted of second-degree murder.

Moroni Hicks was the third of eight children born to George Armstrong and Elizabeth Temperance Jolley Hicks in Spanish Fork, Utah in 1859. We know little about the murder for which they convicted him, except that the victim was a man named Johnson in Sandhole, which was an early name for Hamer.

Booking photos for Hicks got lost when his prison file was being examined by the attorney general’s office to determine his eligibility for parole. One poor photo of him from later years exists (below). We know he was a large man, but his description varied depending on who was telling the story. When they booked him into the territorial prison, they described Hicks as six feet three and one-fourth inches with a light complexion, grey eyes, and light brown hair. In a later account, he was six-six with red whiskers.

Hicks made his first escape on September 3, 1880, not long after his incarceration. He and five other convicts were picking apples in the Robert Wilson orchard when they rushed their guard and the orchard owner, overpowering them. Five of the prisoners chopped off their shackles, stole some guns, including two shotguns, and a cartridge belt.

The orchard was near the prison. C.W. Newman, a prison guard, heard Mrs. Wilson screaming. He mounted his horse and rode over to investigate. When he got near the house, one of the convicts shot him in the face. As he fell and turned, someone shot him in the back.

Other prison guards had dashed into town to tell of the escape. In minutes a posse formed, including several soldiers from Fort Boise. When the posse arrived at the orchard, they met a fusillade from the house where the Wilsons were now held hostage.

A cavalry corporal took a bullet to his body. Another soldier gave covering fire for his downed comrade and hit convict William Reese. He would die the next day and the corporal would recover. One of the convicts who had failed to cut his chains off and gave up.

That left four men desperate to escape. They were Moroni Hicks and John Wilson, both doing time for manslaughter, and William Mays and W.H. Overholt (or Overholtz) who were in for life for mail robbery.

Somehow, the four convicts slipped away through the orchard to the Boise River. They swam across and found some horses to steal. Wilson took off on his own for Oregon, while the other three headed east.

The next day word of the escapees came back to Boise from travelers on the Overland road. The men had held up six hunters and ranchers at a ranch 40 miles northeast of Boise. That netted them new horses, some mules, blankets, boots, and other provisions. Convict Mays became especially enamored with a new hat he was able to steal. As far as he knew his old one was back in the Boise orchard with a bullet hole through the crown.

The escapees terrorized several people along their route. Meanwhile, U.S. Marshall E.S. Chase was offering a reward for their capture, $1,000, dead or alive.

On their way east the escaped prisoners raided the Glenn home in Glenn’s Ferry, walking off with canned oysters and salmon.

Further east they were spotted by J.W. White at the mouth of Malad Gorge. A brief shootout with White had no apparent effect on anyone. White wrote to Deputy U.S. Marshal Orlando “Rube” Robbins, head of the pursuing posse, that “I am inclined to think we shall have to kill Mays and Overholtz.” He thought Prisoner Number Two, Moroni Hicks, was more interested in escape than a gun fight.

Hard up for food, the escapees had killed an ox a few days before, a piece of which White had seen, describing the meat as “black as my hat.”

What followed was a hunt through the rocky bottom of Malad Gorge, with occasional gunfire. The fugitives had claimed a cave for their own protection. The posse was sure they had them surrounded and that it would all be over at daybreak. Dawn came and what they found was the escapees had sneaked out during the night.

A night or two later their hunger proved to be the fugitives’ undoing. Marshals spotted a guttering little fire inside a ranch corral not far from the gorge. Cold and hungry the men had dug up some potatoes which they were attempting to roast.

Captured with no further resistance, the men were returned to Boise to face new charges. But this would not be the last taste of freedom for Moroni Hicks.

To be continued tomorrow.

Published on April 10, 2020 04:00

April 9, 2020

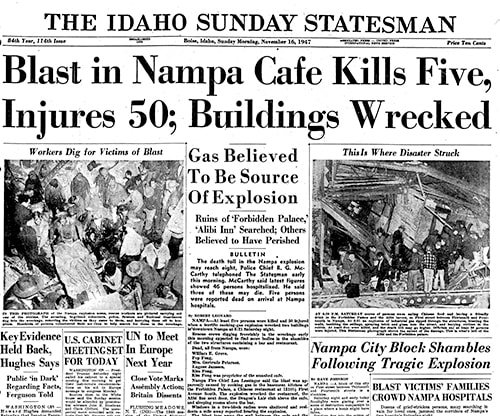

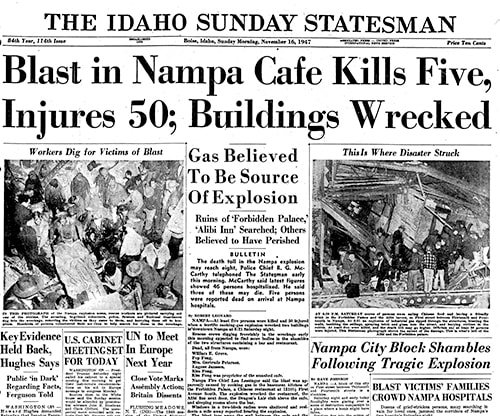

The Forbidden Palace Fire

On Saturday night, November 16, 1947, a customer walked into the Forbidden Palace Chinese restaurant in Nampa, sat down at the counter and said, “I smell gas.”

The waitress replied, “I do, too.”

As if the conversation set it off, an enormous blast rocked the restaurant and the Alibi tavern next door. The floor dropped from beneath their feet and the ceiling came crashing down on top of them. For a moment, as the dust settled, there was silence. Then the screams began.

Fifty people were injured in the explosion and building collapse, six were killed.

The explosion occurred as a service truck was filling the butane gas tank the restaurant used for cooking.

Within a couple of weeks Knu Gas and Appliance of Boise and Nampa was running ads notifying customers that they had nothing to do with the explosion and extolling the safety of PROPANE gas and gas appliances.

By the end of the year, the “Superlatives of 47” feature in the Idaho Statesman listed the Forbidden Palace explosion the greatest Boise Valley disaster of the year.

Numerous lawsuits against the City of Nampa and the company that installed the butane tank were filed. The Idaho Supreme Court ultimately absolved the city of responsibility.

The blast increased calls for establishing a state fire marshal to formulate rules on LPG. Legislation was introduced and defeated in 1948. It wasn’t until 1982 that the first state fire marshal was named. The office is a division of the Idaho Department of Insurance. The director of that department selects the fire marshal with approval of the governor.

The waitress replied, “I do, too.”

As if the conversation set it off, an enormous blast rocked the restaurant and the Alibi tavern next door. The floor dropped from beneath their feet and the ceiling came crashing down on top of them. For a moment, as the dust settled, there was silence. Then the screams began.

Fifty people were injured in the explosion and building collapse, six were killed.

The explosion occurred as a service truck was filling the butane gas tank the restaurant used for cooking.

Within a couple of weeks Knu Gas and Appliance of Boise and Nampa was running ads notifying customers that they had nothing to do with the explosion and extolling the safety of PROPANE gas and gas appliances.

By the end of the year, the “Superlatives of 47” feature in the Idaho Statesman listed the Forbidden Palace explosion the greatest Boise Valley disaster of the year.

Numerous lawsuits against the City of Nampa and the company that installed the butane tank were filed. The Idaho Supreme Court ultimately absolved the city of responsibility.

The blast increased calls for establishing a state fire marshal to formulate rules on LPG. Legislation was introduced and defeated in 1948. It wasn’t until 1982 that the first state fire marshal was named. The office is a division of the Idaho Department of Insurance. The director of that department selects the fire marshal with approval of the governor.

Published on April 09, 2020 04:00

April 8, 2020

A Final Flight

Flying always comes with some risk. If you’re part of the US Air Force Thunderbirds team you are certainly well aware of that.

The Thunderbirds are a demonstration squadron based at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada. They perform aerial acrobatics all over the country, thrilling crowds with their tight formation dives and loops. Their airshow performances have been marred just three times by fatal accidents since the formation of the squadron in 1953. But the worst accident they suffered was not during an airshow. It was during a routine flight over Idaho.

Just at sundown on October 9, 1958, several witnesses saw a cargo plane fly toward the sunset and into the silhouettes of a large flock of geese. The geese scattered, honking their disapproval. The plane’s engines stuttered, raced, then fell silent. The pilot had time to lower the landing gear and was probably looking for a place to put the aircraft down. Instead, it plowed nose first into a brush-covered hillside about six miles southeast of Payette, a ball of flame marking its impact.

The twin-engined Fairchild C123 was on its way from Hill AFB in Utah to McChord AFB in Washington. On board was a flight crew of five along with 14 aircraft maintenance personnel assigned to the Thunderbird squadron. None of the 19 survived. It remains the worst accident ever suffered by the Thunderbird team.

One year after the crash, members of the Payette High School Key Club dedicated a triangle-shaped monument to those who died. It is located in a small park and rest area on State Highway 52 south of Payette. The community has honored the crash victims with an annual ceremony ever since.

This is a Fairchild C123 much like the one that crashed near Payette in 1958.

This is a Fairchild C123 much like the one that crashed near Payette in 1958.

The Thunderbirds are a demonstration squadron based at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada. They perform aerial acrobatics all over the country, thrilling crowds with their tight formation dives and loops. Their airshow performances have been marred just three times by fatal accidents since the formation of the squadron in 1953. But the worst accident they suffered was not during an airshow. It was during a routine flight over Idaho.

Just at sundown on October 9, 1958, several witnesses saw a cargo plane fly toward the sunset and into the silhouettes of a large flock of geese. The geese scattered, honking their disapproval. The plane’s engines stuttered, raced, then fell silent. The pilot had time to lower the landing gear and was probably looking for a place to put the aircraft down. Instead, it plowed nose first into a brush-covered hillside about six miles southeast of Payette, a ball of flame marking its impact.

The twin-engined Fairchild C123 was on its way from Hill AFB in Utah to McChord AFB in Washington. On board was a flight crew of five along with 14 aircraft maintenance personnel assigned to the Thunderbird squadron. None of the 19 survived. It remains the worst accident ever suffered by the Thunderbird team.

One year after the crash, members of the Payette High School Key Club dedicated a triangle-shaped monument to those who died. It is located in a small park and rest area on State Highway 52 south of Payette. The community has honored the crash victims with an annual ceremony ever since.

This is a Fairchild C123 much like the one that crashed near Payette in 1958.

This is a Fairchild C123 much like the one that crashed near Payette in 1958.

Published on April 08, 2020 04:00

April 7, 2020

Those Traveling Drill Halls

Farragut Naval Training Station, which is now Farragut State Park had some unique buildings.

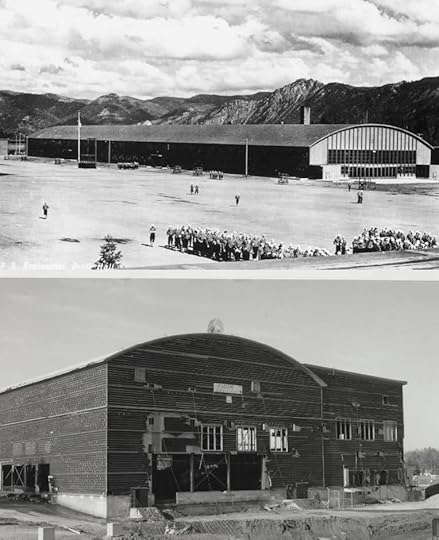

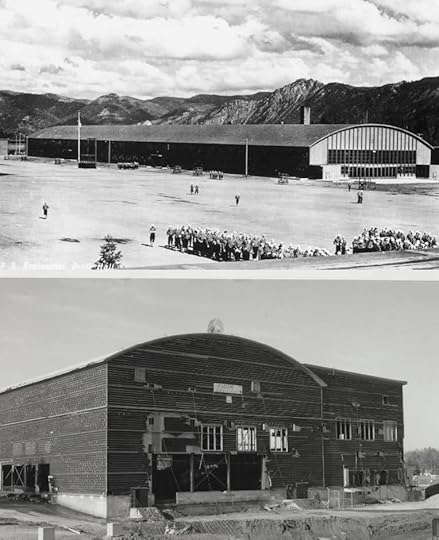

Each of the training camps had drill fields called “grinders” where the recruits marched. The huge regimental drill hall in the background of the top photo allowed training during all kinds of weather. They were billed as the largest clear span (without posts) structures in the world at that time. The structure in the top picture is probably the drill hall at Camp Bennion.

At least two of the drill halls found life after the Navy. One found a new usein Spokane for many years as a Costco. It is still there, just off the Division street exit, and now houses a Goodwill warehouse.

Another of the drill halls was donated to the University of Denver, disassembled, and reassembled on the DU campus in 1948-49. It was used as a hockey arena that fans called “the old barn.” It stood on campus for nearly 50 years. The University of Denver hockey arena was a modified drill hall from Farragut. It is shown here as it was being torn down.

The University of Denver hockey arena was a modified drill hall from Farragut. It is shown here as it was being torn down.

Each of the training camps had drill fields called “grinders” where the recruits marched. The huge regimental drill hall in the background of the top photo allowed training during all kinds of weather. They were billed as the largest clear span (without posts) structures in the world at that time. The structure in the top picture is probably the drill hall at Camp Bennion.

At least two of the drill halls found life after the Navy. One found a new usein Spokane for many years as a Costco. It is still there, just off the Division street exit, and now houses a Goodwill warehouse.

Another of the drill halls was donated to the University of Denver, disassembled, and reassembled on the DU campus in 1948-49. It was used as a hockey arena that fans called “the old barn.” It stood on campus for nearly 50 years.

The University of Denver hockey arena was a modified drill hall from Farragut. It is shown here as it was being torn down.

The University of Denver hockey arena was a modified drill hall from Farragut. It is shown here as it was being torn down.

Published on April 07, 2020 04:00

April 6, 2020

The Last Swim of Mr. Swim

Isaac T. Swim was a prospector who, like most prospectors, hadn't done very well. In 1881, his luck changed.

Swim camped near the mouth of the Yankee Fork. A tremendous wind and rainstorm kept him there an extra day. When he woke up the next morning, he discovered that the wind had blown down branches and trees all around him. But that wasn't all he discovered. Beneath the roots of an uprooted tree, Isaac Swim discovered the glitter of gold.

The prospector blazed trees in the area so he could be certain of finding his way back. Then he set out for Challis, where he filed a mining claim on September 9, 1881.

Swim returned to his claim and gathered some choice samples of quartz generously flecked with gold. When he brought that back to civilization, it set men's imaginations to running wild. His grubstake partners were elated. They could hardly wait for spring.

Swim tried to lead his partners back to the claim in June 1882. Some stories say that a gaggle of miners also followed Swim, hoping to cash in.

The Salmon River was roaring with spring run-off. Eager to get back to his claim, Swim risked the river astride his horse. No one saw him drown, but it seems certain that the man named Swim was swept away in the river.

His partners went on to the area where Swim had discovered the vein. They found at least one of his tree blazes, but they didn't locate any gold.

Swim’s horse turned up months later, 50 miles downstream, lodged in driftwood. A body thought to be Swim’s turned up that summer in the Salmon River about 12 miles southwest of Challis. The site is called Dead Man’s Hole. A BLM campground is there today (photo).

Meanwhile, the Lost Swim Mine is still out there for the finding.

Swim camped near the mouth of the Yankee Fork. A tremendous wind and rainstorm kept him there an extra day. When he woke up the next morning, he discovered that the wind had blown down branches and trees all around him. But that wasn't all he discovered. Beneath the roots of an uprooted tree, Isaac Swim discovered the glitter of gold.

The prospector blazed trees in the area so he could be certain of finding his way back. Then he set out for Challis, where he filed a mining claim on September 9, 1881.

Swim returned to his claim and gathered some choice samples of quartz generously flecked with gold. When he brought that back to civilization, it set men's imaginations to running wild. His grubstake partners were elated. They could hardly wait for spring.

Swim tried to lead his partners back to the claim in June 1882. Some stories say that a gaggle of miners also followed Swim, hoping to cash in.

The Salmon River was roaring with spring run-off. Eager to get back to his claim, Swim risked the river astride his horse. No one saw him drown, but it seems certain that the man named Swim was swept away in the river.

His partners went on to the area where Swim had discovered the vein. They found at least one of his tree blazes, but they didn't locate any gold.

Swim’s horse turned up months later, 50 miles downstream, lodged in driftwood. A body thought to be Swim’s turned up that summer in the Salmon River about 12 miles southwest of Challis. The site is called Dead Man’s Hole. A BLM campground is there today (photo).

Meanwhile, the Lost Swim Mine is still out there for the finding.

Published on April 06, 2020 04:00

April 5, 2020

Boise in Hot Water

We talk a lot about alternative energy these days. You’ll find solar panels on my house and a plug-in car in my garage. But alternative energy is not new in Idaho.

In 1890 well drillers found 177 degree water pure enough for domestic use near the state penitentiary in Boise.

The water was first used to create a hot water resort. Boise's beautiful natatorium opened in May 1892 to the delight of swimmers and soakers. That same year, C.W. Moore put the hot water to another use. He piped it into his home to provide heat. The system worked well, and H.B. Eastman, who had built a mansion nearby, began to use geothermal heat. Others along the street saw the advantage, and they built a community heat line, using wooden pipe at first. It cost two dollars a month to heat an eight-room house--three dollars would heat the larger ones along Warm Springs Avenue in Boise. You've probably already figured out why the street got its name.

The system is still in use today, and it's been expanded to include more homes, apartments, and businesses.Boise City Hall, the Ada County Courthouse, Idaho's statehouse, and much of Boise State University are on the geothermal system. It was the first system of its kind in the United States.

Boise's geothermal building plaque was designed by Boise artist Ward Hooper.

Boise's geothermal building plaque was designed by Boise artist Ward Hooper.

In 1890 well drillers found 177 degree water pure enough for domestic use near the state penitentiary in Boise.

The water was first used to create a hot water resort. Boise's beautiful natatorium opened in May 1892 to the delight of swimmers and soakers. That same year, C.W. Moore put the hot water to another use. He piped it into his home to provide heat. The system worked well, and H.B. Eastman, who had built a mansion nearby, began to use geothermal heat. Others along the street saw the advantage, and they built a community heat line, using wooden pipe at first. It cost two dollars a month to heat an eight-room house--three dollars would heat the larger ones along Warm Springs Avenue in Boise. You've probably already figured out why the street got its name.

The system is still in use today, and it's been expanded to include more homes, apartments, and businesses.Boise City Hall, the Ada County Courthouse, Idaho's statehouse, and much of Boise State University are on the geothermal system. It was the first system of its kind in the United States.

Boise's geothermal building plaque was designed by Boise artist Ward Hooper.

Boise's geothermal building plaque was designed by Boise artist Ward Hooper.

Published on April 05, 2020 04:00