Rick Just's Blog, page 169

March 5, 2020

A Holdup at the Nat

It was approaching midnight on September 28, 1902. Natatorium manager Fred Peterson, bartender Nicholas Steinfeld, and four guests, Frank Bayhorse, W. Heuschkel, Ida Wells, and Julia Valverde, were in the lounge at the Nat having a quiet chat. That’s when two rough looking men, their faces obscured by handkerchiefs, burst through the swinging doors pointing revolvers and telling everyone to line up against a wall.

While one of the robbers moved the customers and bartender into the hallway and held them at gunpoint, the other herded Peterson into the manager’s office and demanded that he open the safe. Peterson fumbled with the dial, his hands shaking.

The man pointing the gun at him said, “Hurry up or I will use my gun; we haven’t much time.”

Peterson might have wondered what the hurry was. After a few more seconds of twisting the dial he did it right and the door to the safe swung open.

The hold-up man ordered Peterson to take out the two money drawers and take them to the front of the Natatorium where everyone else was lined up under guard. Thug number two had relieved them all of their cash. The robbers ordered everyone to face the wall and stay there for ten minutes.

On their way out of the building the armed men encountered two customers coming through the door. They ordered them to get quickly inside and up against the wall. One, Si Kent, apparently did not comply fast enough. One of the thugs hit him on the head with the butt of his gun, stunning him.

The gunmen then ran to catch the trolley, which had just made its regular stop near the Nat, thus explaining the particular hurry they were in. The men ordered motorman Herbert Shaw at the point of a pistol to move it along and quickly. At Second Street they had him stop the trolley. They jumped off and headed north on foot.

Within the hour bloodhounds from the nearby penitentiary were called into service to find the hoodlums. It was to no avail.

Speculation was that the men knew the safe would have more money than usual, Friday being payday for many. They got away with more than $500 in cash, the equivalent of about $13,000 in today’s dollars.

A couple of days after the robbery, The Idaho Statesman speculated that motorman Shaw must “have broken all records, not only for the trip to Second Street, where the men alighted, but the entire distance to the power house. It was probable if ever he feared for his trolley to leave the wire it was during his enforced run that night.”

The robbery was said to be “undoubtedly one of the boldest holdups in the history of Boise.” Bold it was, and successful. The robbers were never caught.

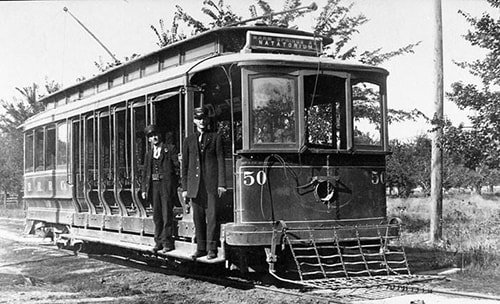

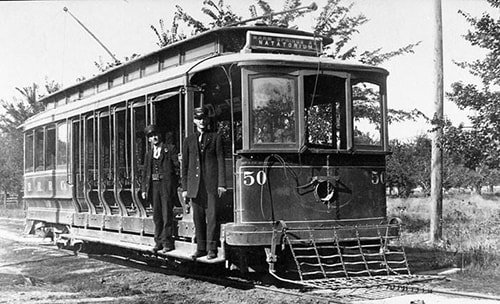

This might have been the getaway trolley used during the robbery of the Nat. Note the destination sign on this Warm Springs car.

This might have been the getaway trolley used during the robbery of the Nat. Note the destination sign on this Warm Springs car.

While one of the robbers moved the customers and bartender into the hallway and held them at gunpoint, the other herded Peterson into the manager’s office and demanded that he open the safe. Peterson fumbled with the dial, his hands shaking.

The man pointing the gun at him said, “Hurry up or I will use my gun; we haven’t much time.”

Peterson might have wondered what the hurry was. After a few more seconds of twisting the dial he did it right and the door to the safe swung open.

The hold-up man ordered Peterson to take out the two money drawers and take them to the front of the Natatorium where everyone else was lined up under guard. Thug number two had relieved them all of their cash. The robbers ordered everyone to face the wall and stay there for ten minutes.

On their way out of the building the armed men encountered two customers coming through the door. They ordered them to get quickly inside and up against the wall. One, Si Kent, apparently did not comply fast enough. One of the thugs hit him on the head with the butt of his gun, stunning him.

The gunmen then ran to catch the trolley, which had just made its regular stop near the Nat, thus explaining the particular hurry they were in. The men ordered motorman Herbert Shaw at the point of a pistol to move it along and quickly. At Second Street they had him stop the trolley. They jumped off and headed north on foot.

Within the hour bloodhounds from the nearby penitentiary were called into service to find the hoodlums. It was to no avail.

Speculation was that the men knew the safe would have more money than usual, Friday being payday for many. They got away with more than $500 in cash, the equivalent of about $13,000 in today’s dollars.

A couple of days after the robbery, The Idaho Statesman speculated that motorman Shaw must “have broken all records, not only for the trip to Second Street, where the men alighted, but the entire distance to the power house. It was probable if ever he feared for his trolley to leave the wire it was during his enforced run that night.”

The robbery was said to be “undoubtedly one of the boldest holdups in the history of Boise.” Bold it was, and successful. The robbers were never caught.

This might have been the getaway trolley used during the robbery of the Nat. Note the destination sign on this Warm Springs car.

This might have been the getaway trolley used during the robbery of the Nat. Note the destination sign on this Warm Springs car.

Published on March 05, 2020 04:00

March 4, 2020

Idaho's First White Settler

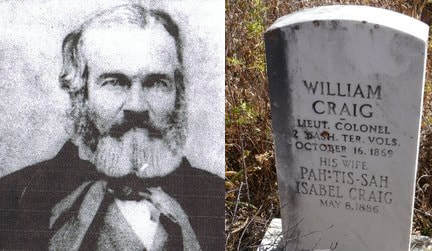

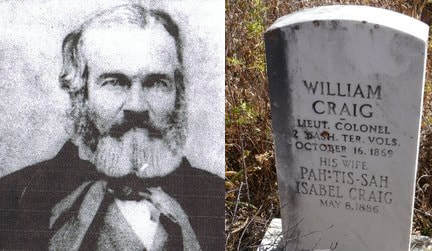

The name Idaho may not yet have been invented in 1840 when William Craig became the first permanent settler within the bounds of what would become the 43rd state.

Born in Virginia in 1807, Craig was about 18 when he joined a group of trappers associated with the American Fur Company. In 1836 he and two other trappers established the Fort Davy Crockett trading post in what is now Colorado. When the fur trade there started to wane, he went west with his frontiersmen friends Joe Meek and Robert Newell. Those men ended up in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, but Craig, who had fallen in love with a Nez Perce woman, decided to settle in her homeland near present day Lapwai.

His Nimiipuu wife was called Pahtissah by her family, but Craig called her Isabel. The mission of Henry and Eliza Spalding was not far away. The Spaldings had established their mission in 1836, so theirs counts as the first white home in Idaho, but they left in 1847 after their missionary friends, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman were killed by Cayuse Indians at their mission near Walla Walla.

Spalding didn’t care much for Craig, but did value his ability to communicate with the Nez Perce. The Spaldings found the Craig home a handy refuge when they decided to abandon their mission.

Craig’s reputation for good relations with the natives served him well. He was an Indian agent to the Nez Perce and served the same role for a time at Fort Boise.

When the Nez Perce negotiated the treaty of 1848, they honored their friend by giving him 640 acres inside their new reservation.

Craig was not only the first permanent settler, but he was credited with coming up with the name of what would become Idaho. A lot of people have been credited with that, and it is widely disputed. In this case, it was frontiersman, poet, and newspaper editor Joaquin Miller who claimed William Craig knew it as the Indian word “E-dah-Hoe,” meaning “the light on the line of the mountains” In 1861.

William Craig died in 1869 and is buried near his home in the Jacques Spur Cemetery, also called the Craig Cemetery. Craig Mountain Plateau, between the Snake, Salmon, and Clearwater rivers is named in his honor.

Born in Virginia in 1807, Craig was about 18 when he joined a group of trappers associated with the American Fur Company. In 1836 he and two other trappers established the Fort Davy Crockett trading post in what is now Colorado. When the fur trade there started to wane, he went west with his frontiersmen friends Joe Meek and Robert Newell. Those men ended up in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, but Craig, who had fallen in love with a Nez Perce woman, decided to settle in her homeland near present day Lapwai.

His Nimiipuu wife was called Pahtissah by her family, but Craig called her Isabel. The mission of Henry and Eliza Spalding was not far away. The Spaldings had established their mission in 1836, so theirs counts as the first white home in Idaho, but they left in 1847 after their missionary friends, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman were killed by Cayuse Indians at their mission near Walla Walla.

Spalding didn’t care much for Craig, but did value his ability to communicate with the Nez Perce. The Spaldings found the Craig home a handy refuge when they decided to abandon their mission.

Craig’s reputation for good relations with the natives served him well. He was an Indian agent to the Nez Perce and served the same role for a time at Fort Boise.

When the Nez Perce negotiated the treaty of 1848, they honored their friend by giving him 640 acres inside their new reservation.

Craig was not only the first permanent settler, but he was credited with coming up with the name of what would become Idaho. A lot of people have been credited with that, and it is widely disputed. In this case, it was frontiersman, poet, and newspaper editor Joaquin Miller who claimed William Craig knew it as the Indian word “E-dah-Hoe,” meaning “the light on the line of the mountains” In 1861.

William Craig died in 1869 and is buried near his home in the Jacques Spur Cemetery, also called the Craig Cemetery. Craig Mountain Plateau, between the Snake, Salmon, and Clearwater rivers is named in his honor.

Published on March 04, 2020 04:00

March 3, 2020

Czenzi Ormonde

My great aunt, Agnes Just Reid, was a prolific poet, newspaper columnist, and the author of a couple of books. She corresponded with many other writers. While going through some of her letters recently I learned about an Idaho writer I had never heard about.

Czenzi (pronounced Chen-zee, with the accent on Chen) Ormonde was born in Tacoma in 1906 and moved to Los Angeles as a teenager. But she spent her last 57 years living in Hayden Lake. She wrote there when she wasn’t writing in Hollywood.

Much of her Hollywood career was anything but glamorous. She worked as a pool secretary for several studios. In the early 1930s she began having some success with writing, selling short stories to magazines. She wrote a couple of novels, Solomon and the Queen of Sheba ,* and Laughter from Downstairs,* both of which have long been out of print.

But it was her screenplay for Strangers on a Train ,* directed by Alfred Hitchcock, that is most remembered. She wasn’t Hitchcock’s first choice. Nor was she his second. She wasn’t even his eighth choice. She was number 9.

Hitchcock shopped a story treatment of the Patricia Highsmith novel around to name writers, among them John Steinbeck and Thornton Wilder. Everyone turned him down until he finally interested Raymond Chandler. Chandler wrote a couple of drafts before walking away from the project, tired of Hitchcock’s penchant for long, rambling meetings the subject of which rarely had anything to do with the movie. Next, Hitchcock tried Ben Hecht, who had written The Front Page, among other screenplays. Hecht passed, but suggested that his assistant, Czenzi Ormonde would be a good choice.

According to Patrick McGilligan’s book, Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light ,* at the first meeting with Ormonde, the director pinched his nose while holding up Chandler's screenplay, then dropped into the trash. He said he wouldn’t use a single line from it. He also told her not to bother reading the book. He gave her the early treatment of the movie and told her to start with a blank page.

Ormonde did as instructed and produced the screenplay for a movie that even today rates 98% on Rotten Tomatoes.

So, of course she was vaulted from obscurity and into the limelight where she would find her fame and fortune. Just kidding. She did well with her writing, but initially received little notoriety for Strangers on a Train. In spite of Hitchcock’s avowed distaste for Raymond Chandler’s screenplay, Warner Brothers slapped Chandler’s name on the film as the screenwriter. Such is Hollywood.

Ormonde was eventually recognized for her good work but didn’t get a lot of publicity for it. That was probably okay with her. Czenzi Ormonde was shy about publicity.

Which brings us back around to that letter to my great aunt I mentioned in the beginning of this piece. Agnes Just Reid had queried her on behalf of the Idaho Writers League in 1958, wondering if she would be interested in speaking to the group. Ormonde’s humble response, in part, was:

“I would be pleased but surprised if I could say anything to the members of the Writers League, as you suggested, which could be helpful. For being a professional writer does not automatically make me an authority. I fear it would be presumptuous to give advice. I’m sure the writers of Idaho do not need it, not if their work reflects the vigor and variety of this state’s geography! More power to them!”

Czenzi Ormonde died in 2004 at her home in Hayden Lake. She was 94.

Czenzi (pronounced Chen-zee, with the accent on Chen) Ormonde was born in Tacoma in 1906 and moved to Los Angeles as a teenager. But she spent her last 57 years living in Hayden Lake. She wrote there when she wasn’t writing in Hollywood.

Much of her Hollywood career was anything but glamorous. She worked as a pool secretary for several studios. In the early 1930s she began having some success with writing, selling short stories to magazines. She wrote a couple of novels, Solomon and the Queen of Sheba ,* and Laughter from Downstairs,* both of which have long been out of print.

But it was her screenplay for Strangers on a Train ,* directed by Alfred Hitchcock, that is most remembered. She wasn’t Hitchcock’s first choice. Nor was she his second. She wasn’t even his eighth choice. She was number 9.

Hitchcock shopped a story treatment of the Patricia Highsmith novel around to name writers, among them John Steinbeck and Thornton Wilder. Everyone turned him down until he finally interested Raymond Chandler. Chandler wrote a couple of drafts before walking away from the project, tired of Hitchcock’s penchant for long, rambling meetings the subject of which rarely had anything to do with the movie. Next, Hitchcock tried Ben Hecht, who had written The Front Page, among other screenplays. Hecht passed, but suggested that his assistant, Czenzi Ormonde would be a good choice.

According to Patrick McGilligan’s book, Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light ,* at the first meeting with Ormonde, the director pinched his nose while holding up Chandler's screenplay, then dropped into the trash. He said he wouldn’t use a single line from it. He also told her not to bother reading the book. He gave her the early treatment of the movie and told her to start with a blank page.

Ormonde did as instructed and produced the screenplay for a movie that even today rates 98% on Rotten Tomatoes.

So, of course she was vaulted from obscurity and into the limelight where she would find her fame and fortune. Just kidding. She did well with her writing, but initially received little notoriety for Strangers on a Train. In spite of Hitchcock’s avowed distaste for Raymond Chandler’s screenplay, Warner Brothers slapped Chandler’s name on the film as the screenwriter. Such is Hollywood.

Ormonde was eventually recognized for her good work but didn’t get a lot of publicity for it. That was probably okay with her. Czenzi Ormonde was shy about publicity.

Which brings us back around to that letter to my great aunt I mentioned in the beginning of this piece. Agnes Just Reid had queried her on behalf of the Idaho Writers League in 1958, wondering if she would be interested in speaking to the group. Ormonde’s humble response, in part, was:

“I would be pleased but surprised if I could say anything to the members of the Writers League, as you suggested, which could be helpful. For being a professional writer does not automatically make me an authority. I fear it would be presumptuous to give advice. I’m sure the writers of Idaho do not need it, not if their work reflects the vigor and variety of this state’s geography! More power to them!”

Czenzi Ormonde died in 2004 at her home in Hayden Lake. She was 94.

Published on March 03, 2020 04:00

March 2, 2020

Ahead of its Time

When Amity School was built in southwest Boise, the design was ahead of its time. Only two other earth-sheltered schools were in existence in the US. And, if 50 years is the yardstick you use to measure what qualifies as a historical building—as many do—it is again ahead of its time. The Amity School came down in 2018 after 39 years of use.

When the Boise School District purchased 15 acres for a new elementary school in 1975, energy issues were on everyone’s mind. The Yom Kippur war had taken place two years earlier and Arab countries were embargoing oil to the United States in retaliation for our country’s assistance to Israel in that conflict. Oil prices quadrupled.

So the school district decided to build an energy efficient building. They needed voter approval, of course. Usually school bonds are set for a given amount of money, then the district designs to that amount and comes in at or under budget. Not this time. Voters knew exactly what they were voting on when they went to the polls to give the up or down on the Amity School Bond. The district had already called for designs and chosen the most expensive one, at $3.5 million. They sold the proposal to voters on the idea that this earth-sheltered school with solar panels providing hot water heat, would pay for itself in lower energy costs. They expected the extra construction costs to be paid back in 16 years, and the solar panels to pay for themselves in 11 years. The district was wrong. With ever-increasing energy costs, the payback time was about half that.

Most people thought of Amity School as that “underground” school. It wasn’t. The concrete outer walls were poured on site, above ground, and the inner walls were completed with concrete block. Then, they put pre-cast concrete beams across the whole thing to form a roof. Once all the concrete was in place, they pushed about two feet of dirt up onto the roof and angled it against the walls on all sides to provide added insulation. The plan was originally to let the kids spend recess on the roof, playing in the grass. Early drawings showed landscaping up there, but it never happened, perhaps because there was plenty of ground for recess around the school and perhaps because watering the roof would add extra cost and complication, potentially causing leaks. That is, more leaks than were destined to happen anyway.

Designers didn’t want the school to feel like a cave, so they designed it so that every classroom had a door to the outside and one good-sized window. Offices, the lunchroom, restrooms, the gym, and the library were in the center of the structure and without natural light, but every room was painted in light, bright colors to compensate.

When the school came on line in 1979, its innovative design made Time Magazine. That first year the energy costs of the school were 72-74 percent lower than other schools in the district of similar size.

Amity School could handle 788 kids from kindergarten to sixth grade in 26 classrooms. Thousands of Boise kids grew up as “Groundhogs” (the school mascot was Solar Sam).

But, everything has a lifespan, and Amity School reached the end of its days in 2018, replaced by a new school built right next door.

Why tear down an innovative building? Leaks, mostly. That sod and concrete roof never could keep water out. But the district has learned a lot from the school. Several other schools in Boise use earth sheltered walls (not roofs) and other innovative features first tried out at Amity.

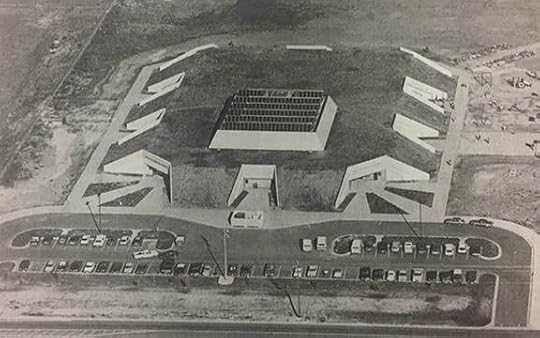

By the way, the first Amity School was in what was then the Meridian School District. It was built in 1919 to serve students a few miles west of the current school. The original Amity School was named such (probably) because the word means friendship and goodwill. They built a road to the school, which became Amity Road. The original school was converted to a private residence in the early 1950s, but was recently torn down. The name still stuck for the road, though, which then got attached to the earth-sheltered school, built in 1978, and first occupied in 1979. Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

When the Boise School District purchased 15 acres for a new elementary school in 1975, energy issues were on everyone’s mind. The Yom Kippur war had taken place two years earlier and Arab countries were embargoing oil to the United States in retaliation for our country’s assistance to Israel in that conflict. Oil prices quadrupled.

So the school district decided to build an energy efficient building. They needed voter approval, of course. Usually school bonds are set for a given amount of money, then the district designs to that amount and comes in at or under budget. Not this time. Voters knew exactly what they were voting on when they went to the polls to give the up or down on the Amity School Bond. The district had already called for designs and chosen the most expensive one, at $3.5 million. They sold the proposal to voters on the idea that this earth-sheltered school with solar panels providing hot water heat, would pay for itself in lower energy costs. They expected the extra construction costs to be paid back in 16 years, and the solar panels to pay for themselves in 11 years. The district was wrong. With ever-increasing energy costs, the payback time was about half that.

Most people thought of Amity School as that “underground” school. It wasn’t. The concrete outer walls were poured on site, above ground, and the inner walls were completed with concrete block. Then, they put pre-cast concrete beams across the whole thing to form a roof. Once all the concrete was in place, they pushed about two feet of dirt up onto the roof and angled it against the walls on all sides to provide added insulation. The plan was originally to let the kids spend recess on the roof, playing in the grass. Early drawings showed landscaping up there, but it never happened, perhaps because there was plenty of ground for recess around the school and perhaps because watering the roof would add extra cost and complication, potentially causing leaks. That is, more leaks than were destined to happen anyway.

Designers didn’t want the school to feel like a cave, so they designed it so that every classroom had a door to the outside and one good-sized window. Offices, the lunchroom, restrooms, the gym, and the library were in the center of the structure and without natural light, but every room was painted in light, bright colors to compensate.

When the school came on line in 1979, its innovative design made Time Magazine. That first year the energy costs of the school were 72-74 percent lower than other schools in the district of similar size.

Amity School could handle 788 kids from kindergarten to sixth grade in 26 classrooms. Thousands of Boise kids grew up as “Groundhogs” (the school mascot was Solar Sam).

But, everything has a lifespan, and Amity School reached the end of its days in 2018, replaced by a new school built right next door.

Why tear down an innovative building? Leaks, mostly. That sod and concrete roof never could keep water out. But the district has learned a lot from the school. Several other schools in Boise use earth sheltered walls (not roofs) and other innovative features first tried out at Amity.

By the way, the first Amity School was in what was then the Meridian School District. It was built in 1919 to serve students a few miles west of the current school. The original Amity School was named such (probably) because the word means friendship and goodwill. They built a road to the school, which became Amity Road. The original school was converted to a private residence in the early 1950s, but was recently torn down. The name still stuck for the road, though, which then got attached to the earth-sheltered school, built in 1978, and first occupied in 1979.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym. You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors. The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances. The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

Published on March 02, 2020 04:00

March 1, 2020

Mesa Orchards

When you think of big apple operations today, you probably think of Washington State. It’s the top apple producing state in the country. But over the years, Southwestern Idaho had some impressive orchards, from the one where Julia Davis Park is today to the orchards in Kuna, Emmett, and Sunnyslope. For a while, one of the largest operations in the world was located about 13 miles north of Cambridge at a place called Mesa.

The Mesa Orchards Company began as a cooperative in 1911. Investors, often from the East, purchased ten-acre plots for $500 an acre. The early money went into an essential project. Before you can become one of the largest apple suppliers in the world, you need to have a lot of apple trees, which require a lot of water, which, in the case of Mesa Orchards, required the building of six miles of flume from a new reservoir constructed for the operation.

Maintenance of the flume, care of the trees, and the harvest of fruit—including some peaches and pears—took a lot of people. Some 50 families lived in the little community of Mesa. It had its own post office, a company store, and a two-room school.

At its peak the Mesa Orchards Company boasted some 1500 acres of orchards, planted 80 trees to the acre. The operation was so big they built a 3 ½ mile aerial tramway to transport boxes of apples to the Mesa railroad siding. It was a tourist attraction. One 1922 story in the Idaho Statesman started with the comment that “like most travelers along the highway, we halted at Mesa, where a model community has been erected for the benefit of workers.” The year before, more than 120 train cars full of apples and peaches had been shipped to different parts of the country “commanding fancy prices in New York State.”

The Mesa Orchards Company had some million-dollar years, but the downs were more frequent than the ups. One year jackrabbits killed a lot of fruit trees when winter conditions had the critters chewing the bark from around their base. In 1920 a packinghouse fire burned through 50,000 boxes of apples.

There were early freezes, and poor markets. Managers came and went. Finally, in 1954, the property was sold to a ranching family from Montana. By the time Brian and Emma Ball purchased the property the operation was down to about 700 acres of fruit trees. They were planning to make a go of it in the fruit business. A late frost put the kibosh on that, ruining 40,000 boxes of freshly picked apples that were sitting under the trees, along with some 100,000 boxes still to be picked.

What remained of the trees were uprooted in 1967. The tramway that had become a tourist attraction was purchased by a mining company. They took down the towers and moved the whole contraption out of state.

A few abandoned sections of the flume are today about the only signs that one of the world’s biggest apple operations once thrived at Mesa.

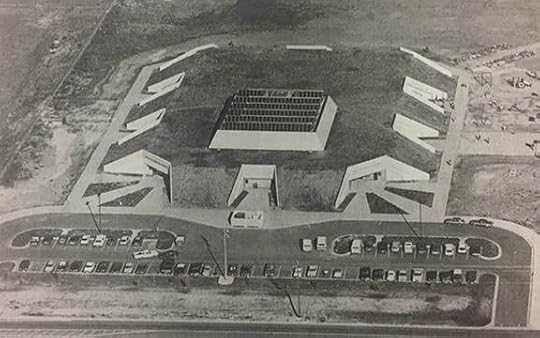

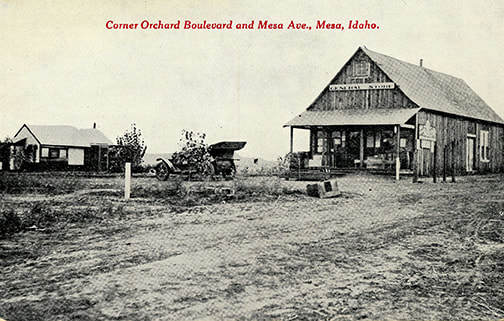

To learn more about Mesa Orchards, I recommend Cort Conley’s book, Idaho for the Curious ,* which is where I found much of the information for this post. The little company town of Mesa, Idaho supplied almost everything workers needed. It was located about 13 miles north of Cambridge. Real Picture Postcard photo from the Mike Fritz Collection.

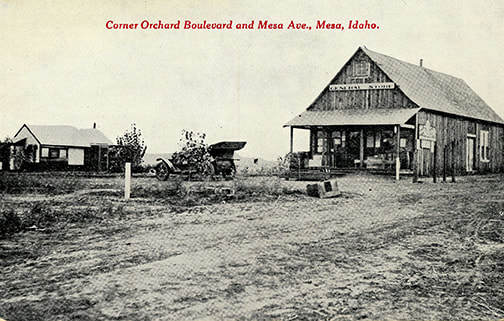

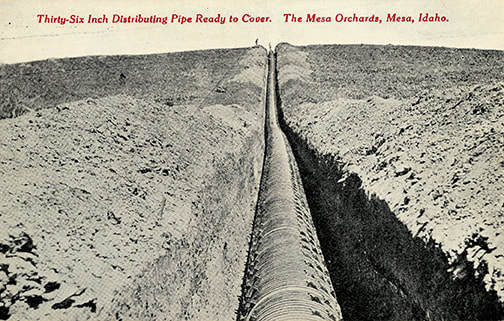

The little company town of Mesa, Idaho supplied almost everything workers needed. It was located about 13 miles north of Cambridge. Real Picture Postcard photo from the Mike Fritz Collection.  Six miles of flume watered the hundreds of acres of apples growing at the Mesa Orchards Company. Real Picture Postcard photo from the Mike Fritz Collection.

Six miles of flume watered the hundreds of acres of apples growing at the Mesa Orchards Company. Real Picture Postcard photo from the Mike Fritz Collection.

The Mesa Orchards Company began as a cooperative in 1911. Investors, often from the East, purchased ten-acre plots for $500 an acre. The early money went into an essential project. Before you can become one of the largest apple suppliers in the world, you need to have a lot of apple trees, which require a lot of water, which, in the case of Mesa Orchards, required the building of six miles of flume from a new reservoir constructed for the operation.

Maintenance of the flume, care of the trees, and the harvest of fruit—including some peaches and pears—took a lot of people. Some 50 families lived in the little community of Mesa. It had its own post office, a company store, and a two-room school.

At its peak the Mesa Orchards Company boasted some 1500 acres of orchards, planted 80 trees to the acre. The operation was so big they built a 3 ½ mile aerial tramway to transport boxes of apples to the Mesa railroad siding. It was a tourist attraction. One 1922 story in the Idaho Statesman started with the comment that “like most travelers along the highway, we halted at Mesa, where a model community has been erected for the benefit of workers.” The year before, more than 120 train cars full of apples and peaches had been shipped to different parts of the country “commanding fancy prices in New York State.”

The Mesa Orchards Company had some million-dollar years, but the downs were more frequent than the ups. One year jackrabbits killed a lot of fruit trees when winter conditions had the critters chewing the bark from around their base. In 1920 a packinghouse fire burned through 50,000 boxes of apples.

There were early freezes, and poor markets. Managers came and went. Finally, in 1954, the property was sold to a ranching family from Montana. By the time Brian and Emma Ball purchased the property the operation was down to about 700 acres of fruit trees. They were planning to make a go of it in the fruit business. A late frost put the kibosh on that, ruining 40,000 boxes of freshly picked apples that were sitting under the trees, along with some 100,000 boxes still to be picked.

What remained of the trees were uprooted in 1967. The tramway that had become a tourist attraction was purchased by a mining company. They took down the towers and moved the whole contraption out of state.

A few abandoned sections of the flume are today about the only signs that one of the world’s biggest apple operations once thrived at Mesa.

To learn more about Mesa Orchards, I recommend Cort Conley’s book, Idaho for the Curious ,* which is where I found much of the information for this post.

The little company town of Mesa, Idaho supplied almost everything workers needed. It was located about 13 miles north of Cambridge. Real Picture Postcard photo from the Mike Fritz Collection.

The little company town of Mesa, Idaho supplied almost everything workers needed. It was located about 13 miles north of Cambridge. Real Picture Postcard photo from the Mike Fritz Collection.  Six miles of flume watered the hundreds of acres of apples growing at the Mesa Orchards Company. Real Picture Postcard photo from the Mike Fritz Collection.

Six miles of flume watered the hundreds of acres of apples growing at the Mesa Orchards Company. Real Picture Postcard photo from the Mike Fritz Collection.

Published on March 01, 2020 04:00

February 29, 2020

Pop Quiz!

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). What is Wilson Butte Cave known for?

A. It’s the largest lava tube in North America.

B. It was one of several “Robbers Roosts” in the West.

C. It is the site of the oldest known human habitation in Idaho.

D. A box of rusty rifles from the 1800s was found there.

E. All of the above.

2). What was Dorthy Johnson of Pocatello known for?

A. She was Miss Idaho in 1964.

B. She was an award-winning educator.

C. She was the Los Angeles Reading Association's Teacher of the Year in 1992.

D. She was the first African American semi-finalist in the Miss USA Pageant.

E. All of the above.

3). What was the Steamboat Shoshone’s claim to fame?

A. It was the first steamboat to make it from Portland to Lewiston.

B. It was a split-wheel boat that could turn 360 degrees in its own length.

C. It was the first and only steamboat that worked on the Snake River near Parma.

D. It was the last steamboat on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

E. It was blown up on Lake Coeur d’Alene as a Fourth of July stunt.

4). What made Hugh Whitney infamous?

A. He held up a bar in Monida, Montana?

B. He shot and killed a train conductor in Idaho.

C. He held up a bank in Wyoming.

D. He fought in WWI while wanted for murder.

E. All of the above.

5) What kind of Idaho mine made Benjamin Franklin White a fortune?

A. Gold.

B. Coal.

C. Silver

D. Salt

E. Gravel Answers

Answers

1, C

2, E

3, C

4, E

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). What is Wilson Butte Cave known for?

A. It’s the largest lava tube in North America.

B. It was one of several “Robbers Roosts” in the West.

C. It is the site of the oldest known human habitation in Idaho.

D. A box of rusty rifles from the 1800s was found there.

E. All of the above.

2). What was Dorthy Johnson of Pocatello known for?

A. She was Miss Idaho in 1964.

B. She was an award-winning educator.

C. She was the Los Angeles Reading Association's Teacher of the Year in 1992.

D. She was the first African American semi-finalist in the Miss USA Pageant.

E. All of the above.

3). What was the Steamboat Shoshone’s claim to fame?

A. It was the first steamboat to make it from Portland to Lewiston.

B. It was a split-wheel boat that could turn 360 degrees in its own length.

C. It was the first and only steamboat that worked on the Snake River near Parma.

D. It was the last steamboat on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

E. It was blown up on Lake Coeur d’Alene as a Fourth of July stunt.

4). What made Hugh Whitney infamous?

A. He held up a bar in Monida, Montana?

B. He shot and killed a train conductor in Idaho.

C. He held up a bank in Wyoming.

D. He fought in WWI while wanted for murder.

E. All of the above.

5) What kind of Idaho mine made Benjamin Franklin White a fortune?

A. Gold.

B. Coal.

C. Silver

D. Salt

E. Gravel

Answers

Answers1, C

2, E

3, C

4, E

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on February 29, 2020 04:00

February 28, 2020

The Lincoln Creek Day School

The sad looking wreck of a school shown in the black and white picture accompanying this post represented an enormous improvement for the children of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. Built in 1937, the Lincoln Creek Day School operated only until 1944. It was part of a last-ditch effort from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to indoctrinate Shoshone and Bannock children into white culture. After this school, and a couple of others like it on the reservation were closed, Indian children most often began enrolling in regular public schools.

The Lincoln Creek Day School was an improvement over the Lincoln Creek Boarding School which was built at the first site of the military Fort Hall a few miles away. Children were cajoled to attend the day school to receive an education during the day and allowed to go home to their families at night. Like many such schools on reservations around the country, the earlier boarding school was much like a prison. Beginning in 1882 children were taken from their families, often by reservation police, and forced to live at the school in sometimes dangerous conditions.

At the Fort Hall boarding school children would attend classes during the morning hours. In the afternoon the girls would work in the kitchen, laundry, or sewing room, while the boys raised crops for school use and tended milk cows. All wore uniforms and most got new names. Siblings from a family might end up with two or three surnames.

Sickness spread quickly in the cramped boarding school. In 1891, ten students died from scarlet fever. Some students committed suicide. Years later students remembered playing in the schoolyard and finding bones of buried children at the Lincoln Creek Boarding School.

The attitude of the government was probably best summed up by the following quote.

"The Indians must conform to ‘the white man's ways,' peaceably if they will, forcibly if they must. They must adjust themselves to their environment, and conform their mode of living substantially to our civilization. This civilization may not be the best possible, but it is the best the Indians can get. They can not escape it, and must either conform to it or be crushed by it." –Thomas Morgan, US Commissioner of Indian Affairs, October 1889

Dr. Brigham Madsen, prominent historian of the early West wrote in his book, The Northern Shoshoni, "An ironic footnote to the educational troubles at Fort Hall came in a directive from the commissioner's office in August 1892 that all Indian schools were to hold an appropriate celebration in honor of Columbus Day in ‘line with practices and exercises of the public schools of this country.' Furthermore, the ‘interest and enthusiasm' of the children' were to be ‘thoroughly aroused.' No doubt many of the Shoshoni and Bannock wished Columbus had discovered some other country."

It is important to remember even the dark side of our history. All traces of the Lincoln Creek Boarding School are gone, but the Tribe is working to preserve The Lincoln Creek Day School. The Idaho Heritage Trust has been helping them do that with several grants in recent years. Once the renovation is completed, it will become a community center for that section of the reservation.

The Lincoln Creek Day School had fallen into disuse and become an attraction for vandals by latter part of the Twentieth Century when this picture was taken.

The Lincoln Creek Day School had fallen into disuse and become an attraction for vandals by latter part of the Twentieth Century when this picture was taken.  There is still much to do inside the Lincoln Creek Day School, but the exterior of the building now shows the results of much loving attention.

There is still much to do inside the Lincoln Creek Day School, but the exterior of the building now shows the results of much loving attention.

The Lincoln Creek Day School was an improvement over the Lincoln Creek Boarding School which was built at the first site of the military Fort Hall a few miles away. Children were cajoled to attend the day school to receive an education during the day and allowed to go home to their families at night. Like many such schools on reservations around the country, the earlier boarding school was much like a prison. Beginning in 1882 children were taken from their families, often by reservation police, and forced to live at the school in sometimes dangerous conditions.

At the Fort Hall boarding school children would attend classes during the morning hours. In the afternoon the girls would work in the kitchen, laundry, or sewing room, while the boys raised crops for school use and tended milk cows. All wore uniforms and most got new names. Siblings from a family might end up with two or three surnames.

Sickness spread quickly in the cramped boarding school. In 1891, ten students died from scarlet fever. Some students committed suicide. Years later students remembered playing in the schoolyard and finding bones of buried children at the Lincoln Creek Boarding School.

The attitude of the government was probably best summed up by the following quote.

"The Indians must conform to ‘the white man's ways,' peaceably if they will, forcibly if they must. They must adjust themselves to their environment, and conform their mode of living substantially to our civilization. This civilization may not be the best possible, but it is the best the Indians can get. They can not escape it, and must either conform to it or be crushed by it." –Thomas Morgan, US Commissioner of Indian Affairs, October 1889

Dr. Brigham Madsen, prominent historian of the early West wrote in his book, The Northern Shoshoni, "An ironic footnote to the educational troubles at Fort Hall came in a directive from the commissioner's office in August 1892 that all Indian schools were to hold an appropriate celebration in honor of Columbus Day in ‘line with practices and exercises of the public schools of this country.' Furthermore, the ‘interest and enthusiasm' of the children' were to be ‘thoroughly aroused.' No doubt many of the Shoshoni and Bannock wished Columbus had discovered some other country."

It is important to remember even the dark side of our history. All traces of the Lincoln Creek Boarding School are gone, but the Tribe is working to preserve The Lincoln Creek Day School. The Idaho Heritage Trust has been helping them do that with several grants in recent years. Once the renovation is completed, it will become a community center for that section of the reservation.

The Lincoln Creek Day School had fallen into disuse and become an attraction for vandals by latter part of the Twentieth Century when this picture was taken.

The Lincoln Creek Day School had fallen into disuse and become an attraction for vandals by latter part of the Twentieth Century when this picture was taken.  There is still much to do inside the Lincoln Creek Day School, but the exterior of the building now shows the results of much loving attention.

There is still much to do inside the Lincoln Creek Day School, but the exterior of the building now shows the results of much loving attention.

Published on February 28, 2020 04:00

February 27, 2020

Raptor Man

Idaho is a mecca for raptor lovers from all over the world. That’s because it is a magnet for birds of prey. The World Center for Birds of Prey is in Boise, Boise State University is home to the Raptor Research Center and offers the only Masters of Science in Raptor Research, and The Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area (NCA)is south of Kuna.

The birds congregate in the NCA not because it is a protected area, but because it is an ideal place for raptors to live. The uplift of air from the Snake River Canyon makes flying and gliding (sorry) a breeze for the birds, and the uplands above the canyon rim provide habitat for ground squirrels and other critters the birds consider lunch.

Morley Nelson figured that out when he first saw the canyon in the late 1940s. He had developed a love for raptors—especially peregrine falcons—growing up on a farm in North Dakota. When he moved to Idaho, following a WWI stint with the famous Tenth Mountain Division, he went out to the Snake River Canyon to see if he could find some raptors. He found a few. There are typically about 800 pairs of hawks, eagles, owls, and falcons that nest there each spring. It’s the greatest concentration of nesting raptors in North America, and probably the world.

Nelson became evangelical about the birds and their Snake River Canyon habitat. He worked on films about the birds with Walt Disney, Paramount Pictures, the Public Broadcasting System, and others. His passion for the birds was contagious, and through his efforts public understanding of their role in the natural world was greatly enhanced.

Morley Nelson convinced Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton to establish the Snake River Birds of Prey Natural area in 1971, and an expansion of the area by Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus in 1980. Then in 1993, US Representative Larry LaRocco led an effort in Congress to designate some 485,000 acres as a National Conservation Area.

It was also Nelson who led the effort to convince the Peregrine Fund to relocate to Boise and build the World Center for Birds of Prey south of town.

While those efforts were going on, Nelson was also doing pioneer work on an effort to save raptors from power line electrocution. He worked with the Edison Electric Institute and Idaho Power to study how raptors used those manmade perches known as power poles. Through those efforts poles are now designed to minimize electrocution and even provide safe nesting areas for the birds.

When Morley Nelson passed away in 2005 he had unquestionably done more to save and protect raptors than any other single person.

For more on Morley Nelson, see his biography, Cool North Wind , written by Steve Steubner.

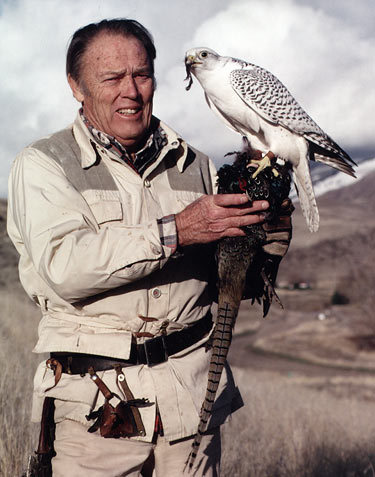

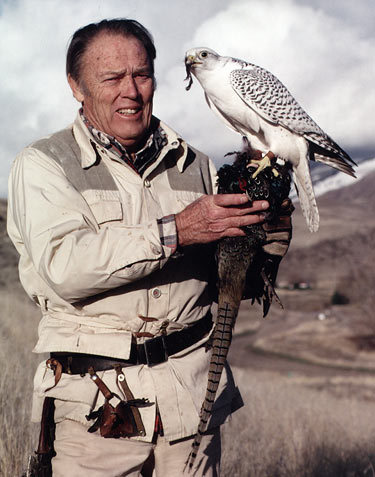

Morely Nelson with one of his favorite birds, a gyrfalcon named Thor. Photo courtesy of Steve Stuebner.

Morely Nelson with one of his favorite birds, a gyrfalcon named Thor. Photo courtesy of Steve Stuebner.

The birds congregate in the NCA not because it is a protected area, but because it is an ideal place for raptors to live. The uplift of air from the Snake River Canyon makes flying and gliding (sorry) a breeze for the birds, and the uplands above the canyon rim provide habitat for ground squirrels and other critters the birds consider lunch.

Morley Nelson figured that out when he first saw the canyon in the late 1940s. He had developed a love for raptors—especially peregrine falcons—growing up on a farm in North Dakota. When he moved to Idaho, following a WWI stint with the famous Tenth Mountain Division, he went out to the Snake River Canyon to see if he could find some raptors. He found a few. There are typically about 800 pairs of hawks, eagles, owls, and falcons that nest there each spring. It’s the greatest concentration of nesting raptors in North America, and probably the world.

Nelson became evangelical about the birds and their Snake River Canyon habitat. He worked on films about the birds with Walt Disney, Paramount Pictures, the Public Broadcasting System, and others. His passion for the birds was contagious, and through his efforts public understanding of their role in the natural world was greatly enhanced.

Morley Nelson convinced Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton to establish the Snake River Birds of Prey Natural area in 1971, and an expansion of the area by Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus in 1980. Then in 1993, US Representative Larry LaRocco led an effort in Congress to designate some 485,000 acres as a National Conservation Area.

It was also Nelson who led the effort to convince the Peregrine Fund to relocate to Boise and build the World Center for Birds of Prey south of town.

While those efforts were going on, Nelson was also doing pioneer work on an effort to save raptors from power line electrocution. He worked with the Edison Electric Institute and Idaho Power to study how raptors used those manmade perches known as power poles. Through those efforts poles are now designed to minimize electrocution and even provide safe nesting areas for the birds.

When Morley Nelson passed away in 2005 he had unquestionably done more to save and protect raptors than any other single person.

For more on Morley Nelson, see his biography, Cool North Wind , written by Steve Steubner.

Morely Nelson with one of his favorite birds, a gyrfalcon named Thor. Photo courtesy of Steve Stuebner.

Morely Nelson with one of his favorite birds, a gyrfalcon named Thor. Photo courtesy of Steve Stuebner.

Published on February 27, 2020 04:00

February 26, 2020

Marie Dorion, Part 2

When we left off yesterday, the Astorians—those still alive—had made it to Fort Astoria near the mouth of the Columbia. Marie and Pierre Dorion and their two children stayed at the fort a little over a year, then joined others on a beaver trapping expedition for the Pacific Fur Company in July 1813.

The men set up camp at the mouth of the Boise River near present-day Parma. After a time they determined a better site for their base would be along the Boise nearer present-day Caldwell. Marie and the kids, along with a few men, took care of things at the base camp while the trappers went out on their rounds in small groups. Pierre worked the Boise River along with Giles Le Clerc and Jacob Reznor.

In January 1814, the new year arrived with word from friendly local Indians that a band of Bannocks was terrorizing the trapping camps. Fearing for the safety of her husband, Marie piled the two kids on a horse with her and set out up the Boise to warn the trappers.

Three days later she arrived at the hut they had built, a little too late. Pierre and Jacob Reznor had been killed. Le Clerc was badly wounded. Marie got him up on a horse that was wandering near the camp, in spite of his protestations for her to leave him. The four of them began trekking back to the base camp. Two days later, Le Clerc died from his wounds.

Arriving at the base camp Marie Dorion found devastation. Everyone in camp had been killed and their bodies mutilated. All the weapons but a couple of knives had been looted. Marie gather together some meager supplies, including a buffalo robe and a couple of deerskins, and did what she had to do. In the dead of winter, she set out with her children for Fort Astoria, 500 miles away.

Her first major obstacle was the Snake River. She swam the horses across, dragging a float she had improvised for their supplies. Marie Dorion fought snowdrifts then for nine days up Burnt River, north along the Powder River, and across the hills to the Grande Ronde and to the foot of the Blue Mountains. Near today’s La Grande, Oregon, exhausted, Marie stopped and built a crude shelter beneath a rock overhang.

Marie and her children holed up in the shelter for 53 days. Early on Marie killed the horses, smoking their meat to preserve it. She caught mice with horsehair snares and foraged for a few frozen berries. Marie rationed the food through the winter. By mid-March it was getting dangerously low. They abandoned their shelter and set out on foot for the west. Marie looked for landmarks she might recognize from her trek to Astoria nearly two years before. But looking became agony. At that altitude everything was still blindingly white.

John Baptiste excitedly pointed to tracks in the snow. When they went to them their joy evaporated. The tracks were their own. They had been traveling in a circle.

The three sought the shelter of nearby brush and holed up for three days to let Marie’s eyes rest. The reprieve from staring into the maddening reflections did the trick. She could again see, but they were out of food. Growing weaker each day they were near the point where Paul, the youngest child, could no longer go on and Marie had lost the capacity to carry him.

Marie saw smoke. Quickly she found a rude shelter in the brush for the children and secreted them away there. Then she went to determine the source of the smoke. She found a camp from the Walla Walla Tribe. Some of them remembered her from two years before when she and the Astorians had travelled through the country. She was saved at last. The Walla Wallas took the three back to their camp where members of the Astoria group found them a few weeks later.

Marie Dorion would live out the rest of her life in the Northwest, first at Fort Okanagon near present-day Brewster, Washington, where she lived with a French-Canadian trapper named Venier. They had a daughter in about 1819 they named Marguerite. Later, Marie met Jean Baptiste Toupin, another French-Canadian. They had two children together, Francois and Marianne, and were married in a Roman Catholic ceremony.

The Toupins moved to the Willamette Valley and settled on a farm in 1841. Marie died there in 1850. The priest who recorded her death estimated her age at 100. After what she had been through, she may have looked very old and worn out, but she would have been about 64.

Marie Dorion became well-known in her lifetime thanks to Astoria: Or, Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains , written by Washington Irving and published in 1836.* She is memorialized at Madame Dorion Memorial Park near Wallula, Washington, and has a residence hall named after her at Eastern Oregon University in La Grande. Outside of North Powder, Oregon a memorial plaque marks the likely area where she gave birth to her third child while with the Wilson Price Hunt expedition. A memorial to her was installed at the St. Louis Catholic Church in Gervais, Oregon, just north of Salem, in 2014

Red Heroines of the Northwest , by Byron Defenbach, written in 1929, tells her story extensively. Contemporary accounts include Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson's Lost Pacific Empire , by Peter Stark, and the Tender Ties Trilogy , by Jane Kirkpatrick.* Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

The men set up camp at the mouth of the Boise River near present-day Parma. After a time they determined a better site for their base would be along the Boise nearer present-day Caldwell. Marie and the kids, along with a few men, took care of things at the base camp while the trappers went out on their rounds in small groups. Pierre worked the Boise River along with Giles Le Clerc and Jacob Reznor.

In January 1814, the new year arrived with word from friendly local Indians that a band of Bannocks was terrorizing the trapping camps. Fearing for the safety of her husband, Marie piled the two kids on a horse with her and set out up the Boise to warn the trappers.

Three days later she arrived at the hut they had built, a little too late. Pierre and Jacob Reznor had been killed. Le Clerc was badly wounded. Marie got him up on a horse that was wandering near the camp, in spite of his protestations for her to leave him. The four of them began trekking back to the base camp. Two days later, Le Clerc died from his wounds.

Arriving at the base camp Marie Dorion found devastation. Everyone in camp had been killed and their bodies mutilated. All the weapons but a couple of knives had been looted. Marie gather together some meager supplies, including a buffalo robe and a couple of deerskins, and did what she had to do. In the dead of winter, she set out with her children for Fort Astoria, 500 miles away.

Her first major obstacle was the Snake River. She swam the horses across, dragging a float she had improvised for their supplies. Marie Dorion fought snowdrifts then for nine days up Burnt River, north along the Powder River, and across the hills to the Grande Ronde and to the foot of the Blue Mountains. Near today’s La Grande, Oregon, exhausted, Marie stopped and built a crude shelter beneath a rock overhang.

Marie and her children holed up in the shelter for 53 days. Early on Marie killed the horses, smoking their meat to preserve it. She caught mice with horsehair snares and foraged for a few frozen berries. Marie rationed the food through the winter. By mid-March it was getting dangerously low. They abandoned their shelter and set out on foot for the west. Marie looked for landmarks she might recognize from her trek to Astoria nearly two years before. But looking became agony. At that altitude everything was still blindingly white.

John Baptiste excitedly pointed to tracks in the snow. When they went to them their joy evaporated. The tracks were their own. They had been traveling in a circle.

The three sought the shelter of nearby brush and holed up for three days to let Marie’s eyes rest. The reprieve from staring into the maddening reflections did the trick. She could again see, but they were out of food. Growing weaker each day they were near the point where Paul, the youngest child, could no longer go on and Marie had lost the capacity to carry him.

Marie saw smoke. Quickly she found a rude shelter in the brush for the children and secreted them away there. Then she went to determine the source of the smoke. She found a camp from the Walla Walla Tribe. Some of them remembered her from two years before when she and the Astorians had travelled through the country. She was saved at last. The Walla Wallas took the three back to their camp where members of the Astoria group found them a few weeks later.

Marie Dorion would live out the rest of her life in the Northwest, first at Fort Okanagon near present-day Brewster, Washington, where she lived with a French-Canadian trapper named Venier. They had a daughter in about 1819 they named Marguerite. Later, Marie met Jean Baptiste Toupin, another French-Canadian. They had two children together, Francois and Marianne, and were married in a Roman Catholic ceremony.

The Toupins moved to the Willamette Valley and settled on a farm in 1841. Marie died there in 1850. The priest who recorded her death estimated her age at 100. After what she had been through, she may have looked very old and worn out, but she would have been about 64.

Marie Dorion became well-known in her lifetime thanks to Astoria: Or, Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains , written by Washington Irving and published in 1836.* She is memorialized at Madame Dorion Memorial Park near Wallula, Washington, and has a residence hall named after her at Eastern Oregon University in La Grande. Outside of North Powder, Oregon a memorial plaque marks the likely area where she gave birth to her third child while with the Wilson Price Hunt expedition. A memorial to her was installed at the St. Louis Catholic Church in Gervais, Oregon, just north of Salem, in 2014

Red Heroines of the Northwest , by Byron Defenbach, written in 1929, tells her story extensively. Contemporary accounts include Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson's Lost Pacific Empire , by Peter Stark, and the Tender Ties Trilogy , by Jane Kirkpatrick.*

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Published on February 26, 2020 04:00

February 25, 2020

Marie Dorion, Part 1

This story is a long one, so I’ll to split it into two posts.

Let’s start with an Indian woman, born in 1786, who married a man of French-Canadian heritage. She and her husband served as interpreters to a famous expedition west in the early part of the 18th century. That trek took them across what would become Idaho. She went along to assist with interpretation, taking her son, John Baptiste with them. Her name has been the source of some speculation over the years, though it wasn’t because the pronunciation was in dispute. Marie is a common enough name, though not so common at that time for an Indian woman. The dispute has been whether she ever had a non-Anglo name.

No, this wasn’t Sacajawea, though the parallels are striking. This was Marie Dorion, a contemporary of Sacajawea perhaps born the same year. She very likely knew Sacajawea when they both lived in St. Louis.

Sacajawea was Shoshoni; Marie Dorion was Iowan (the tribe, not the state).

Marie’s husband was Pierre Dorion, Jr. His father, who had served as an interpreter for Lewis and Clark, was French-Canadian and his mother was Yankton-Sioux. With Marie’s Iowan heritage, the Dorions became valued members of the expedition. Between the two of them they spoke French, English, Spanish, and several Indian dialects.

The expedition, which I have studiously avoided naming up to this point, was one financed by fur magnate John Jacob Astor in 1810 in an attempt to claim trapping territory for his newly formed Pacific Fur Company. Astor and his partners chartered two expeditions, one by sea and one by land and river. The members of the ocean expedition built an outpost on the Columbia called Fort Astoria. The fort became the first American settlement in the territory. The Hudson Bay Company, and not incidentally, the British, had ambitions in the area as well.

Astor partnered with Wilson Price Hunt for the overland expedition that was to launch from St. Louis and explore trapping territory all the way to Fort Astoria. Hunt, a New Jersey native and St. Louis merchant would lead the cross-country expedition, in spite of his lack of experience in such endeavors. The group was often called the “Astorians” though Astor himself wasn’t along on either expedition.

On April 21, 1811 the Hunt Party left their winter camp at Fort Osage, near present-day Sibley, Missouri to begin the bulk of their trip west. The ocean-going Astorians had done their part, establishing Fort Astoria nine days earlier, though not without some loss of life due to the treacherous sand bar at the mouth of the Columbia.

The Hunt Party was a large one, consisting of some 60 men. Oh, and one woman. Most were French-Canadian river men, known as voyageurs, since much of the expedition was expected to take place on rivers, just as the Lewis and Clark Expedition had a few years earlier. Worried about a confrontation with hostile Blackfeet, the Hunt Party would cut down through present-day Wyoming and cross the Continental Divide at the headwaters of the Snake River. They hoped to take that unexplored river all the way to Fort Astoria. Abandoning their horses near the headwaters, the Hunt Party built 15 dugout canoes to that end.

The Hunt Party ran into a tad of trouble at Caldron Linn, about 340 miles downriver from where they put in. On October 28, 1811, they lost a canoe, a man, and the desire to travel further on the Snake, which, after a few days of scouting, they declared unnavigable.

Without horses and with suddenly useless dugout canoes, the Hunt Party cached most of their supplies and split up, with about half travelling on either side of the Snake River, setting out on foot for Fort Astoria. Smaller parties would have a better chance of finding enough food to sustain them.

Hunt took the northern route. The Dorian family, Pierre, Marie, John Baptiste, who was four, and Paul, who was two, walked along with him. Well, Marie Dorion carried the two-year-old much of the way, though she was by this time several months pregnant.

They were able to trade for a couple of horses near today’s Boise, but by the time December rolled around the horses had become food. Near starvation they stole several horses from a Shoshoni camp to help them along their way.

The Snake River, which they called the Mad River, proved more obstacle than travel route. Hunt’s party struggled downstream into Hells Canyon only to find the rest of their party slogging back upstream on the opposite side of the river, discouraged by the steep cliffs and relentless rapids ahead.

Marie stayed behind while the rest of the expedition set out on December 30, 1811. She gave birth to her baby, alone, near today’s North Powder, Oregon. Marie then caught up with the rest of party the next day. The baby died a few days later. Most of the bedraggled Hunt Party—45 of the original 60—finally made it to Astoria on May 11, 1812.

And that’s where we’ll leave the story for today. Stop by tomorrow to hear the heroics of Marie Dorian when she travelled back to present-day Idaho. Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Let’s start with an Indian woman, born in 1786, who married a man of French-Canadian heritage. She and her husband served as interpreters to a famous expedition west in the early part of the 18th century. That trek took them across what would become Idaho. She went along to assist with interpretation, taking her son, John Baptiste with them. Her name has been the source of some speculation over the years, though it wasn’t because the pronunciation was in dispute. Marie is a common enough name, though not so common at that time for an Indian woman. The dispute has been whether she ever had a non-Anglo name.

No, this wasn’t Sacajawea, though the parallels are striking. This was Marie Dorion, a contemporary of Sacajawea perhaps born the same year. She very likely knew Sacajawea when they both lived in St. Louis.

Sacajawea was Shoshoni; Marie Dorion was Iowan (the tribe, not the state).

Marie’s husband was Pierre Dorion, Jr. His father, who had served as an interpreter for Lewis and Clark, was French-Canadian and his mother was Yankton-Sioux. With Marie’s Iowan heritage, the Dorions became valued members of the expedition. Between the two of them they spoke French, English, Spanish, and several Indian dialects.

The expedition, which I have studiously avoided naming up to this point, was one financed by fur magnate John Jacob Astor in 1810 in an attempt to claim trapping territory for his newly formed Pacific Fur Company. Astor and his partners chartered two expeditions, one by sea and one by land and river. The members of the ocean expedition built an outpost on the Columbia called Fort Astoria. The fort became the first American settlement in the territory. The Hudson Bay Company, and not incidentally, the British, had ambitions in the area as well.

Astor partnered with Wilson Price Hunt for the overland expedition that was to launch from St. Louis and explore trapping territory all the way to Fort Astoria. Hunt, a New Jersey native and St. Louis merchant would lead the cross-country expedition, in spite of his lack of experience in such endeavors. The group was often called the “Astorians” though Astor himself wasn’t along on either expedition.

On April 21, 1811 the Hunt Party left their winter camp at Fort Osage, near present-day Sibley, Missouri to begin the bulk of their trip west. The ocean-going Astorians had done their part, establishing Fort Astoria nine days earlier, though not without some loss of life due to the treacherous sand bar at the mouth of the Columbia.

The Hunt Party was a large one, consisting of some 60 men. Oh, and one woman. Most were French-Canadian river men, known as voyageurs, since much of the expedition was expected to take place on rivers, just as the Lewis and Clark Expedition had a few years earlier. Worried about a confrontation with hostile Blackfeet, the Hunt Party would cut down through present-day Wyoming and cross the Continental Divide at the headwaters of the Snake River. They hoped to take that unexplored river all the way to Fort Astoria. Abandoning their horses near the headwaters, the Hunt Party built 15 dugout canoes to that end.

The Hunt Party ran into a tad of trouble at Caldron Linn, about 340 miles downriver from where they put in. On October 28, 1811, they lost a canoe, a man, and the desire to travel further on the Snake, which, after a few days of scouting, they declared unnavigable.

Without horses and with suddenly useless dugout canoes, the Hunt Party cached most of their supplies and split up, with about half travelling on either side of the Snake River, setting out on foot for Fort Astoria. Smaller parties would have a better chance of finding enough food to sustain them.

Hunt took the northern route. The Dorian family, Pierre, Marie, John Baptiste, who was four, and Paul, who was two, walked along with him. Well, Marie Dorion carried the two-year-old much of the way, though she was by this time several months pregnant.

They were able to trade for a couple of horses near today’s Boise, but by the time December rolled around the horses had become food. Near starvation they stole several horses from a Shoshoni camp to help them along their way.

The Snake River, which they called the Mad River, proved more obstacle than travel route. Hunt’s party struggled downstream into Hells Canyon only to find the rest of their party slogging back upstream on the opposite side of the river, discouraged by the steep cliffs and relentless rapids ahead.

Marie stayed behind while the rest of the expedition set out on December 30, 1811. She gave birth to her baby, alone, near today’s North Powder, Oregon. Marie then caught up with the rest of party the next day. The baby died a few days later. Most of the bedraggled Hunt Party—45 of the original 60—finally made it to Astoria on May 11, 1812.

And that’s where we’ll leave the story for today. Stop by tomorrow to hear the heroics of Marie Dorian when she travelled back to present-day Idaho.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Artist Alma Parson's depiction of what Marie Dorion might have looked like from Byron Defenbach's Red Heroines of the Northwest.

Published on February 25, 2020 04:00