Rick Just's Blog, page 172

February 4, 2020

Steamboat Shoshone

Lewiston was the first capital of Idaho Territory. It was a natural pick, because even in the early 1860s people could see the clear advantage of an inland port. Steamers could bring supplies upriver from Portland and haul ore back down. That served the mines in northern Idaho well. But in 1863, the year the territory was formed, the mining action was moving south with discoveries in the Owyhees, the Boise Basin, and other sites in the southwestern part of the territory.

It occurred to some entrepreneurs that the river road to an inland port might extend far beyond Lewiston. What if a steamboat could navigate the Snake River all the way to its confluence with the Boise? That would save the drudgery of hauling supplies across country and enable reliable fortunes to be made.

In 1865 the Oregon Steam Navigation Company (OSN) decided to risk their workhorse steamboat the George Wright on an exploratory trip up the Snake.

The 110-foot Wright had been built in 1858 and was a veteran of Columbia and Snake passages. She was the first steamship to make it all the way to Lewiston from Portland in 1861. Now, seven years after its launch the ship was the old lady of the river, ready to be mothballed. The OSN directors decided it was worth the risk to send her upriver under the command of Captain Thomas Stump.

Stump and his crew fought for eight days, battering the old steamer against rocks, making desperate repairs, and nearly sinking her more than once to get 21 miles above the confluence with the Salmon. Climbing a mountain to see that a ribbon of rapids was ahead up the Snake, a dejected Captain Stump limped back to Lewiston.

The OSN was undeterred. They sent Captain Stump south to explore the river from that direction. He found a good stretch of navigable river that he thought would save 95 miles in cross-country travel, even if it might not be possible to get all the way to Lewiston. The vision was a water route that could navigate between Salmon Falls, above Hagerman, and Farewell Bend.

The Oregon company contracted with a Boise sawmill operator, Albert H. Robie (for whom Robie Creek is named), to supply lumber to build a steamboat at the mouth of the Boise River. The boiler and other machinery for the boat was redirected to Idaho from a planned Columbia River steamboat.

The Shoshone launched on April 20, 1866. On board for her maiden voyage from Boise Ferry, near present-day Parma, Captain Josiah Myrick, engineer George B. Underwood, and Idaho Statesman Editor James S. Reynolds.

Reynolds stayed with the boat for several weeks, writing frequent dispatches about its progress. Those who took the reins in his absence were amused by this editorial lark, writing “The editor of this institution and several other bon tons have gone to see the Snake River steamboat. The steamboat puffs them down the river and the editor will puff the steamboat up. If the paper should prove more interesting than usual our readers will please excuse us, for there is no harm intended.”

The Shoshone, as described by Reynolds, drew “20 inches of water, and carried 175 tons.” It was also a work in progress. Carpenters and painters were busy on the upper deck finishing up the boat during its first outing.

The downstream voyage wasn’t a challenge for the new steamboat. The captain opted to continue using wood to fire the boilers even though there was coal available from an ultimately unsuccessful mine near Olds’ Ferry.

On May 21, the boat swung around at Farewell Bend to battle the river upstream. They were hoping to cruise east as far as Hagerman, where trade goods could be loaded and unloaded on a freight route to and from Salt Lake. The going was “duck soup” for a while. Then, about six miles up the Snake from where the Bruneau dumps in the Shoshone smacked its prow into a low waterfall. There was no going forward, so the Shoshone swung around and drifted back down to Owyhee Ferry.

The dreamed of water connection between Farwell Bend and Hagerman remained just that. For a while the boat hauled some mining supplies on the stretch it could navigate. When that proved less than profitable the OSN parked it. The steamer bobbed on the river doing nothing for three years. The owners of the boat decided to cut their losses by taking the Shoshone down through Hells Canyon where it could eventually serve on the Columbia. That worked. Sort of. The steamboat bashed rocks right and left. Battered, it spent a year in Huntington, Oregon before the company continued their attempt to take it downstream in 1870. Finally, it arrived in Lewiston, a cripple, on April 27. They patched her up and put the boat to work on the Columbia, where she met her end in 1874 near the Dalles, smashed to bits. Reportedly, the cabin of the Shoshone floated downstream until some enterprising farmer fished it out and turned it into a chicken coop.

The vision of steamboat navigation in Southwestern Idaho was an expensive one. The Oregon Steam Navigation company had laid out $80,000 to build the Shoshone. That would be well over $2 million in today’s dollars. This may be the only picture of the Shoshone. It was taken in 1873 or 1874 while the boat was docked in Portland. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

This may be the only picture of the Shoshone. It was taken in 1873 or 1874 while the boat was docked in Portland. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

It occurred to some entrepreneurs that the river road to an inland port might extend far beyond Lewiston. What if a steamboat could navigate the Snake River all the way to its confluence with the Boise? That would save the drudgery of hauling supplies across country and enable reliable fortunes to be made.

In 1865 the Oregon Steam Navigation Company (OSN) decided to risk their workhorse steamboat the George Wright on an exploratory trip up the Snake.

The 110-foot Wright had been built in 1858 and was a veteran of Columbia and Snake passages. She was the first steamship to make it all the way to Lewiston from Portland in 1861. Now, seven years after its launch the ship was the old lady of the river, ready to be mothballed. The OSN directors decided it was worth the risk to send her upriver under the command of Captain Thomas Stump.

Stump and his crew fought for eight days, battering the old steamer against rocks, making desperate repairs, and nearly sinking her more than once to get 21 miles above the confluence with the Salmon. Climbing a mountain to see that a ribbon of rapids was ahead up the Snake, a dejected Captain Stump limped back to Lewiston.

The OSN was undeterred. They sent Captain Stump south to explore the river from that direction. He found a good stretch of navigable river that he thought would save 95 miles in cross-country travel, even if it might not be possible to get all the way to Lewiston. The vision was a water route that could navigate between Salmon Falls, above Hagerman, and Farewell Bend.

The Oregon company contracted with a Boise sawmill operator, Albert H. Robie (for whom Robie Creek is named), to supply lumber to build a steamboat at the mouth of the Boise River. The boiler and other machinery for the boat was redirected to Idaho from a planned Columbia River steamboat.

The Shoshone launched on April 20, 1866. On board for her maiden voyage from Boise Ferry, near present-day Parma, Captain Josiah Myrick, engineer George B. Underwood, and Idaho Statesman Editor James S. Reynolds.

Reynolds stayed with the boat for several weeks, writing frequent dispatches about its progress. Those who took the reins in his absence were amused by this editorial lark, writing “The editor of this institution and several other bon tons have gone to see the Snake River steamboat. The steamboat puffs them down the river and the editor will puff the steamboat up. If the paper should prove more interesting than usual our readers will please excuse us, for there is no harm intended.”

The Shoshone, as described by Reynolds, drew “20 inches of water, and carried 175 tons.” It was also a work in progress. Carpenters and painters were busy on the upper deck finishing up the boat during its first outing.

The downstream voyage wasn’t a challenge for the new steamboat. The captain opted to continue using wood to fire the boilers even though there was coal available from an ultimately unsuccessful mine near Olds’ Ferry.

On May 21, the boat swung around at Farewell Bend to battle the river upstream. They were hoping to cruise east as far as Hagerman, where trade goods could be loaded and unloaded on a freight route to and from Salt Lake. The going was “duck soup” for a while. Then, about six miles up the Snake from where the Bruneau dumps in the Shoshone smacked its prow into a low waterfall. There was no going forward, so the Shoshone swung around and drifted back down to Owyhee Ferry.

The dreamed of water connection between Farwell Bend and Hagerman remained just that. For a while the boat hauled some mining supplies on the stretch it could navigate. When that proved less than profitable the OSN parked it. The steamer bobbed on the river doing nothing for three years. The owners of the boat decided to cut their losses by taking the Shoshone down through Hells Canyon where it could eventually serve on the Columbia. That worked. Sort of. The steamboat bashed rocks right and left. Battered, it spent a year in Huntington, Oregon before the company continued their attempt to take it downstream in 1870. Finally, it arrived in Lewiston, a cripple, on April 27. They patched her up and put the boat to work on the Columbia, where she met her end in 1874 near the Dalles, smashed to bits. Reportedly, the cabin of the Shoshone floated downstream until some enterprising farmer fished it out and turned it into a chicken coop.

The vision of steamboat navigation in Southwestern Idaho was an expensive one. The Oregon Steam Navigation company had laid out $80,000 to build the Shoshone. That would be well over $2 million in today’s dollars.

This may be the only picture of the Shoshone. It was taken in 1873 or 1874 while the boat was docked in Portland. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

This may be the only picture of the Shoshone. It was taken in 1873 or 1874 while the boat was docked in Portland. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on February 04, 2020 04:00

February 3, 2020

Root Hog

Root hog, or die, was a well-known phrase in the United States as far back as the 1830s. It was common to turn out hogs and let them fend for themselves, and the phrase became synonymous with fending for oneself. You can do a search on the phrase and find several songs from the Civil War era and earlier with that title.

The phrase popped up often in newspapers of the 1880s and 1890s in Idaho. The Lewiston Teller on February 17, 1887 had an article rich in opinion that went like this: “Tramps are a great nuisance, and should never be left at liberty. It is unjust to the industrious portion of society that they should be compelled to support a horde of strong and healthy idlers. The out-and-out tramp hates work, and never was known to sing that Negro melody, ‘Root hog, or die.’”

In an 1887 opinion in the Idaho Statesman about the Indian “problem,” the author suggested that they be left to “root, hog, or die.” Perhaps he had forgotten that Indians had been the definition of self-sufficient before the idea of land ownership came along with white settlers.

More important to Idaho history, there was a stage station called Root Hog, or Die built in 1887 near the Big Southern Butte by Alexander Toponce. The route it was on started in Blackfoot and served the copper mines near Mackay and north to Challis. Like the phrase it was a reference to, the stage stop was named because they let pigs roam about and fend for themselves on the site, allegedly to keep the rattlesnakes in check. Its name eventually became shortened to Root Hog.

The Wood River Times in 1882 mentioned a road crew grading from Root Hog toward Hailey, and “advancing about 20 miles per day.” The Ketchum Keystone gave us a clue about where Roothog (one word in that article) was located. They reported in 1886 that a salesman for the Lorillard’s Climax Tobocco (sic) Company had an odometer on his buggy. He measured “Blackfoot to Roothog, 24 miles; Roothog to the Buttes, 14 1/2.” An 1890 Blackfoot News article mentioned a surveying effort that might bring irrigation to the area between Root Hog and Blackfoot. That never came about.

In June, 1887 the Idaho News had a single cryptic line from their Challis correspondent reporting that “Root Hog is as lively as ever.”

The original Root Hog stage station was near what today is Atomic City. But the name later became attached to a stage station further north at Kennedy Crossing. Residents of the area were, for some reason, not wild about the name Root Hog. They decided on a fancier name, more in tune with their sophistication, when they applied for a post office. They wanted to call it Junction, because it was at a junction of a couple of roads. Creative as that was, the Postmaster General thought there were already enough Junctions, so he suggested the community be called Arco, in honor of Georg von Arco, of Germany, who was visiting Washington, D.C. at the time. Arco was an important inventor in the field of radio transmission.

The postal people usually got the final say on naming places, so Arco it was. And is, though it later moved a few miles from the original site.

Root Hog just has a different flavor than Arco, don't you think?

Root Hog just has a different flavor than Arco, don't you think?

The phrase popped up often in newspapers of the 1880s and 1890s in Idaho. The Lewiston Teller on February 17, 1887 had an article rich in opinion that went like this: “Tramps are a great nuisance, and should never be left at liberty. It is unjust to the industrious portion of society that they should be compelled to support a horde of strong and healthy idlers. The out-and-out tramp hates work, and never was known to sing that Negro melody, ‘Root hog, or die.’”

In an 1887 opinion in the Idaho Statesman about the Indian “problem,” the author suggested that they be left to “root, hog, or die.” Perhaps he had forgotten that Indians had been the definition of self-sufficient before the idea of land ownership came along with white settlers.

More important to Idaho history, there was a stage station called Root Hog, or Die built in 1887 near the Big Southern Butte by Alexander Toponce. The route it was on started in Blackfoot and served the copper mines near Mackay and north to Challis. Like the phrase it was a reference to, the stage stop was named because they let pigs roam about and fend for themselves on the site, allegedly to keep the rattlesnakes in check. Its name eventually became shortened to Root Hog.

The Wood River Times in 1882 mentioned a road crew grading from Root Hog toward Hailey, and “advancing about 20 miles per day.” The Ketchum Keystone gave us a clue about where Roothog (one word in that article) was located. They reported in 1886 that a salesman for the Lorillard’s Climax Tobocco (sic) Company had an odometer on his buggy. He measured “Blackfoot to Roothog, 24 miles; Roothog to the Buttes, 14 1/2.” An 1890 Blackfoot News article mentioned a surveying effort that might bring irrigation to the area between Root Hog and Blackfoot. That never came about.

In June, 1887 the Idaho News had a single cryptic line from their Challis correspondent reporting that “Root Hog is as lively as ever.”

The original Root Hog stage station was near what today is Atomic City. But the name later became attached to a stage station further north at Kennedy Crossing. Residents of the area were, for some reason, not wild about the name Root Hog. They decided on a fancier name, more in tune with their sophistication, when they applied for a post office. They wanted to call it Junction, because it was at a junction of a couple of roads. Creative as that was, the Postmaster General thought there were already enough Junctions, so he suggested the community be called Arco, in honor of Georg von Arco, of Germany, who was visiting Washington, D.C. at the time. Arco was an important inventor in the field of radio transmission.

The postal people usually got the final say on naming places, so Arco it was. And is, though it later moved a few miles from the original site.

Root Hog just has a different flavor than Arco, don't you think?

Root Hog just has a different flavor than Arco, don't you think?

Published on February 03, 2020 04:00

February 2, 2020

Wilson Butte Cave

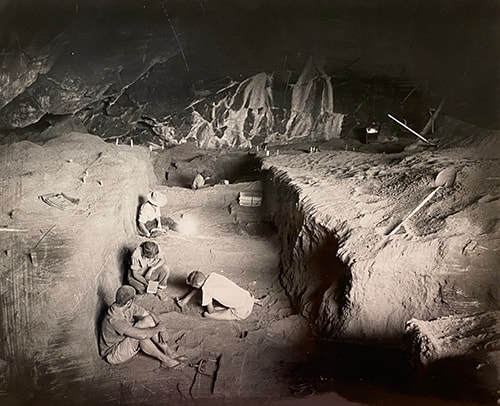

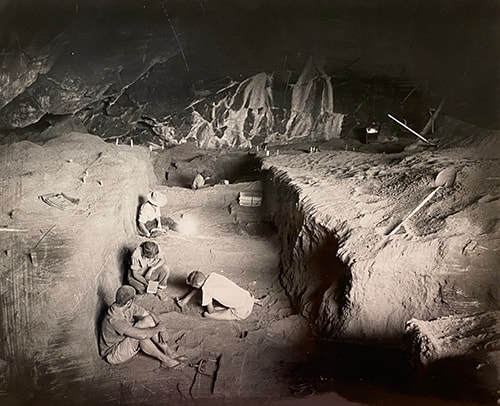

You could probably come up with a hundred reasons to spend a summer in Idaho without straining your brain a bit. In the summer of 1959, Ruth Gruhn came here to dig in the dirt inside a lava blister on the Snake River Plain in Jerome County. Was that one on your list?

Guhn was a grad student. In a way, she was looking for a PhD in the Idaho dirt. Wilson Butte is the lava blister she and others worked in that summer and again in 1988 and 1989. The butte was formed on an otherwise fairly flat lava field by gases that formed a big bubble during an eruption. Part of that bubble collapsed at some point, establishing an entrance to the dome now called Wilson Butte Cave. The cave had been discovered that year by Idaho State University field geologists.

Guhn and her crew meticulously dug, one layer at a time, and recorded what they discovered there. In the lowest layer they found the bones of a couple of camels and an ancient horse. More importantly they found signs of human habitation, including arrow shafts, pottery shards, arrowheads, and a moccasin. Gruhn says the site was occupied by humans 14,000 to 15,000 years ago.

You can climb up on top of Wilson Butte and get a great view of the surrounding country. Archeologists speculate that’s exactly what early people did, looking for bison. Once they had killed one or two, they would bring them back to the cave to process. It would have made a great shelter from the elements.

The dig at Wilson Butte Cave established one of the earliest instances of human presence on the continent. There’s a good chance that people who lived there were present for that interesting little natural phenomenon we call the Bonneville Flood. Imagine what it might have been like to see and hear that go by.

Wilson Butte Cave is accessible. It’s managed by the BLM, so get access information from the Shoshone Field Office or the Twin Falls District Office. Here’s a link to a great little BLM publication about the cave written for kids.

ISU dig at Wilson Butte Cave, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

ISU dig at Wilson Butte Cave, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Guhn was a grad student. In a way, she was looking for a PhD in the Idaho dirt. Wilson Butte is the lava blister she and others worked in that summer and again in 1988 and 1989. The butte was formed on an otherwise fairly flat lava field by gases that formed a big bubble during an eruption. Part of that bubble collapsed at some point, establishing an entrance to the dome now called Wilson Butte Cave. The cave had been discovered that year by Idaho State University field geologists.

Guhn and her crew meticulously dug, one layer at a time, and recorded what they discovered there. In the lowest layer they found the bones of a couple of camels and an ancient horse. More importantly they found signs of human habitation, including arrow shafts, pottery shards, arrowheads, and a moccasin. Gruhn says the site was occupied by humans 14,000 to 15,000 years ago.

You can climb up on top of Wilson Butte and get a great view of the surrounding country. Archeologists speculate that’s exactly what early people did, looking for bison. Once they had killed one or two, they would bring them back to the cave to process. It would have made a great shelter from the elements.

The dig at Wilson Butte Cave established one of the earliest instances of human presence on the continent. There’s a good chance that people who lived there were present for that interesting little natural phenomenon we call the Bonneville Flood. Imagine what it might have been like to see and hear that go by.

Wilson Butte Cave is accessible. It’s managed by the BLM, so get access information from the Shoshone Field Office or the Twin Falls District Office. Here’s a link to a great little BLM publication about the cave written for kids.

ISU dig at Wilson Butte Cave, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

ISU dig at Wilson Butte Cave, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Published on February 02, 2020 04:00

February 1, 2020

Presidential Roots in Idaho

Presidents Benjamin Harrison, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft shared Idaho roots. No, none of them were born here, and none of them lived here, but they all put down roots.

It started with President Harrison. When he visited Idaho in 1891 he planted a red oak in front of the southeast corner of the Territorial Capitol. A rock sugar maple was the next presidential planting. That came about in 1903 when President Theodore Roosevelt visited Boise and put his tree next to Harrison’s red oak. Finally, President Taft planted an Ohio Buckeye (yes, he was from Ohio) next to Roosevelt’s maple.

The trees thrived. The first two planted lasted over 100 years. They came down in 2006, not from some disease but by the chainsaw of progress. That was the year excavation began for the new underground wings at the statehouse. They couldn’t work around the trees.

One Legislator with a sense of history and a woodworking hobby took it upon himself to preserve some of the history of the Idaho presidential trees. Then Rep. Max Black (R), District 15, saved much of the wood from the trees.

According to a story Royce Williams wrote for Idaho Public Television, saving the presidential wood was a challenge. Although Black had arranged with a contractor to secure the wood, when the chainsaws came out, it was a different contractor doing the work. Some fast talking saved the wood. Black then had to scramble to find a place to store it temporarily, and find a longer-term storage site where it could cure. Black secured a portable sawmill and 20 volunteers to slice up the trees. He located kilns in Emmett, Boise, and Meridian where he could dry the lumber.

After curing the wood for 18 months, Black began delivering it to wood carvers around the state. Each carver got enough wood to make something for themselves, and a piece for public display. Those creations are on rotating display today in Statuary Hall in the renovated capitol building (Photo).

It started with President Harrison. When he visited Idaho in 1891 he planted a red oak in front of the southeast corner of the Territorial Capitol. A rock sugar maple was the next presidential planting. That came about in 1903 when President Theodore Roosevelt visited Boise and put his tree next to Harrison’s red oak. Finally, President Taft planted an Ohio Buckeye (yes, he was from Ohio) next to Roosevelt’s maple.

The trees thrived. The first two planted lasted over 100 years. They came down in 2006, not from some disease but by the chainsaw of progress. That was the year excavation began for the new underground wings at the statehouse. They couldn’t work around the trees.

One Legislator with a sense of history and a woodworking hobby took it upon himself to preserve some of the history of the Idaho presidential trees. Then Rep. Max Black (R), District 15, saved much of the wood from the trees.

According to a story Royce Williams wrote for Idaho Public Television, saving the presidential wood was a challenge. Although Black had arranged with a contractor to secure the wood, when the chainsaws came out, it was a different contractor doing the work. Some fast talking saved the wood. Black then had to scramble to find a place to store it temporarily, and find a longer-term storage site where it could cure. Black secured a portable sawmill and 20 volunteers to slice up the trees. He located kilns in Emmett, Boise, and Meridian where he could dry the lumber.

After curing the wood for 18 months, Black began delivering it to wood carvers around the state. Each carver got enough wood to make something for themselves, and a piece for public display. Those creations are on rotating display today in Statuary Hall in the renovated capitol building (Photo).

Published on February 01, 2020 04:00

January 31, 2020

Pop Quiz!

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). What was Duncan McDougal Johnston known for?

A. He was an Idaho congressional candidate.

B. He was the mayor of Twin Falls.

C. He was convicted of murder.

D. He fought in WWI.

E. All of the above.

2). Where did the first airplane flight in Idaho take place?

A. At the Lewiston Fairgrounds.

B. At the Boise Fairgrounds.

C. At the Blackfoot Fairgrounds.

D. At the Twin Falls Fairgrounds.

E. At the Coeur d’Alene Fairgrounds.

3). What brand of car ended up in its roof in Boise’s first auto accident?

A. REO Speedwagon.

B. Ford Model T.

C. A Winton touring car.

D. A Whiting Runabout.

E. An Overland.

4). What powerful Idaho woman wrote Rodeo Idaho?

A. Lulu Bell Parr.

B. Gracie Pfost.

C. Bethine Church.

D. Louise Shadduck.

E. Myrtle Enking.

5) What movie premiered in Boise in 1940?

A. His Girl Friday

B. The Grapes of Wrath

C. Northwest Passage

D. The Great Dictator

E. Pinocchio Answers

Answers

1, E

2, A

3, C

4, D

5, C

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). What was Duncan McDougal Johnston known for?

A. He was an Idaho congressional candidate.

B. He was the mayor of Twin Falls.

C. He was convicted of murder.

D. He fought in WWI.

E. All of the above.

2). Where did the first airplane flight in Idaho take place?

A. At the Lewiston Fairgrounds.

B. At the Boise Fairgrounds.

C. At the Blackfoot Fairgrounds.

D. At the Twin Falls Fairgrounds.

E. At the Coeur d’Alene Fairgrounds.

3). What brand of car ended up in its roof in Boise’s first auto accident?

A. REO Speedwagon.

B. Ford Model T.

C. A Winton touring car.

D. A Whiting Runabout.

E. An Overland.

4). What powerful Idaho woman wrote Rodeo Idaho?

A. Lulu Bell Parr.

B. Gracie Pfost.

C. Bethine Church.

D. Louise Shadduck.

E. Myrtle Enking.

5) What movie premiered in Boise in 1940?

A. His Girl Friday

B. The Grapes of Wrath

C. Northwest Passage

D. The Great Dictator

E. Pinocchio

Answers

Answers1, E

2, A

3, C

4, D

5, C

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on January 31, 2020 04:00

January 30, 2020

Negative .7

Harry Potter fans are familiar with platform 9 ¾ where students on their way to Hogwarts would walk through a wall to catch the train. Idaho has a trail marker on an old railroad route that is every bit as strange. It’s going to take a little history to explain how that came about.

At the peak of mining activity in Idaho’s Silver Valley, countless carloads of ore came out of the ground and travelled by rail between Mullan and Plummer, a 72-mile stretch of train tracks operated by the Burlington Northern Railroad in North Idaho. Those railroad cars were open so it was inevitable that dust and ore particles blew and jostled out onto the tracks beneath those steel wheels.

The railway crossed land owned by the Coeur d’Alene Tribe. Concerned that years of extraction of heavy metals had severely contaminated mining areas and the routes along which the ore travelled for processing, the Tribe sued Union Pacific Railroad and several mining companies to provide funding for a cleanup.

It became clear that cleaning up all the metal contaminants scattered along the old railway would be all but impossible.

In 1995 the federal government, Coeur d’Alene Tribe, and the State of Idaho agreed on a plan to cap the contaminated railroad bed to help contain the contamination. Under the plan the Coeur d’Alene Tribe and the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation share ownership and management of a paved pathway on top of the old Mullan to Plummer line. Union Pacific built the pathway and continues to provide major maintenance. The company also created an endowment fund to help pay for trail needs into the future.

This is a sow’s-ear-to-silk-purse story if ever there was one. The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes now attracts tourists from all over the world bringing business to bike rental shops, ice cream sellers, restaurants, and lodging establishments along the smooth route of those rattly old trains. It winds across lakes, beside rivers and streams, and between stands of timber where bicyclists can ride without a thought about traffic.

It’s 72-miles long. Plus a tad more. After all the trail markers were in place, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe built a beautiful park in Plummer in honor of Tribal members who lost their lives fighting for the United States. A new section of pathway there leads to the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes, and serves as the start of the trail on the western end. So, yes, there is a mile-marker negative point seven. Start your ride on the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes there and you’ll find it every bit as magical as a Harry Potter adventure.

At the peak of mining activity in Idaho’s Silver Valley, countless carloads of ore came out of the ground and travelled by rail between Mullan and Plummer, a 72-mile stretch of train tracks operated by the Burlington Northern Railroad in North Idaho. Those railroad cars were open so it was inevitable that dust and ore particles blew and jostled out onto the tracks beneath those steel wheels.

The railway crossed land owned by the Coeur d’Alene Tribe. Concerned that years of extraction of heavy metals had severely contaminated mining areas and the routes along which the ore travelled for processing, the Tribe sued Union Pacific Railroad and several mining companies to provide funding for a cleanup.

It became clear that cleaning up all the metal contaminants scattered along the old railway would be all but impossible.

In 1995 the federal government, Coeur d’Alene Tribe, and the State of Idaho agreed on a plan to cap the contaminated railroad bed to help contain the contamination. Under the plan the Coeur d’Alene Tribe and the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation share ownership and management of a paved pathway on top of the old Mullan to Plummer line. Union Pacific built the pathway and continues to provide major maintenance. The company also created an endowment fund to help pay for trail needs into the future.

This is a sow’s-ear-to-silk-purse story if ever there was one. The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes now attracts tourists from all over the world bringing business to bike rental shops, ice cream sellers, restaurants, and lodging establishments along the smooth route of those rattly old trains. It winds across lakes, beside rivers and streams, and between stands of timber where bicyclists can ride without a thought about traffic.

It’s 72-miles long. Plus a tad more. After all the trail markers were in place, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe built a beautiful park in Plummer in honor of Tribal members who lost their lives fighting for the United States. A new section of pathway there leads to the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes, and serves as the start of the trail on the western end. So, yes, there is a mile-marker negative point seven. Start your ride on the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes there and you’ll find it every bit as magical as a Harry Potter adventure.

Published on January 30, 2020 04:00

January 29, 2020

Blackfoot's Sugar Factory

Let’s start today’s post, which recently ran as a column in the Blackfoot Morning News, with a pop quiz. What three iconic Blackfoot facilities were built on sand dunes? The answer, according to Idaho Republican editor Byrd Trego, writing in Volume 1, Number 1, of that paper in July 1904, is that the original Bingham County Courthouse, the Idaho Insane Asylum, and the Blackfoot sugar factory were all built on sand dunes.

That came up because construction of the sugar factory was just getting underway that year. By some accounts, which I’ve been unable to confirm, it was supposed to have been built the year before, but the project was hijacked. According to that story several men from Blackfoot had purchased the equipment for a sugar factory, but some scoundrels who wanted it for themselves changed the paperwork on the shipment and had it unloaded near the town of Lincoln where a sugar factory was built.

Putting possible treachery aside, the sugar factory that became a Blackfoot symbol was built in 1904. In August of that year, the local paper was reporting that “The carbonators, evaporators, fourteen diffusion batteries, all juice pumps and the entire boiler plan are now being placed in position.” Most of that equipment, manufactured in France, had been purchased from a bankrupt factory in Binghamton, New York.

Horse drawn Fresno scrapers leveled the sand dune prior to construction and carved out a reservoir for storing 70,000 tons of beet pulp. During construction about 180 men were put to work, 40 of them on the masonry alone. Many of those concentrated on bricking up the 135-foot smokestack that would be a Blackfoot icon for more than a hundred years.

In September the paper reported that there would be ancillary beet dumps placed in Firth, Moreland, and Wapello. Managers at the plant were showing local beet farmers how to construct wagon racks that would work best with the equipment going in. Those wagons along with train cars would be using one of several elevated trestles that facilitated dumping beets into huge piles.

The factory, with mostly French equipment, was an international operation. To get things rolling they had ordered half a carload of muriatic acid, 28,000 pounds of brimstone, 10,000 yards of cotton filtering cloth, 500 beet knives from Germany, and 8,000 sheets of parchment from Belgium.

On September 19, 1904, a strike of workers building the factory threatened to stop progress. Forty-six men said they would walk out if they didn’t get an additional nickel an hour in wages. Management rejected their demands. Thirty-seven of them walked off the job and left town.

The mini strike didn’t impact progress much. The factory was ready for the beets to start rolling in on Wednesday, November 9 at 1 pm, about a week ahead of schedule.

The Blackfoot plant could process 600 tons of beets a day, at first. That increased to an 800-ton daily capacity in 1911. The factory was closed for the season in 1910 because curly top had infected area beets. It closed, again, in 1922, 1926, and 1927 for the same reason. Its peak year of production was 1940, when it processed 104,206 tons of beets and turned out 368,007 bags of sugar.

The factory closed for good in 1948 and the equipment was dismantled in 1952. It served as a sugar storage warehouse for many years, starting in 1954. The iconic smokestack, which stood for 112 years, came down in 2016.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

That came up because construction of the sugar factory was just getting underway that year. By some accounts, which I’ve been unable to confirm, it was supposed to have been built the year before, but the project was hijacked. According to that story several men from Blackfoot had purchased the equipment for a sugar factory, but some scoundrels who wanted it for themselves changed the paperwork on the shipment and had it unloaded near the town of Lincoln where a sugar factory was built.

Putting possible treachery aside, the sugar factory that became a Blackfoot symbol was built in 1904. In August of that year, the local paper was reporting that “The carbonators, evaporators, fourteen diffusion batteries, all juice pumps and the entire boiler plan are now being placed in position.” Most of that equipment, manufactured in France, had been purchased from a bankrupt factory in Binghamton, New York.

Horse drawn Fresno scrapers leveled the sand dune prior to construction and carved out a reservoir for storing 70,000 tons of beet pulp. During construction about 180 men were put to work, 40 of them on the masonry alone. Many of those concentrated on bricking up the 135-foot smokestack that would be a Blackfoot icon for more than a hundred years.

In September the paper reported that there would be ancillary beet dumps placed in Firth, Moreland, and Wapello. Managers at the plant were showing local beet farmers how to construct wagon racks that would work best with the equipment going in. Those wagons along with train cars would be using one of several elevated trestles that facilitated dumping beets into huge piles.

The factory, with mostly French equipment, was an international operation. To get things rolling they had ordered half a carload of muriatic acid, 28,000 pounds of brimstone, 10,000 yards of cotton filtering cloth, 500 beet knives from Germany, and 8,000 sheets of parchment from Belgium.

On September 19, 1904, a strike of workers building the factory threatened to stop progress. Forty-six men said they would walk out if they didn’t get an additional nickel an hour in wages. Management rejected their demands. Thirty-seven of them walked off the job and left town.

The mini strike didn’t impact progress much. The factory was ready for the beets to start rolling in on Wednesday, November 9 at 1 pm, about a week ahead of schedule.

The Blackfoot plant could process 600 tons of beets a day, at first. That increased to an 800-ton daily capacity in 1911. The factory was closed for the season in 1910 because curly top had infected area beets. It closed, again, in 1922, 1926, and 1927 for the same reason. Its peak year of production was 1940, when it processed 104,206 tons of beets and turned out 368,007 bags of sugar.

The factory closed for good in 1948 and the equipment was dismantled in 1952. It served as a sugar storage warehouse for many years, starting in 1954. The iconic smokestack, which stood for 112 years, came down in 2016.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

This 1943 watercolor of the Blackfoot sugar factory was painted by Mable Bennett Hutchinson who grew up in Lower Presto. It shows the elevated unloading trestles better than most photos of the factory. Hutchinson went on to be a celebrated artist in California.

Published on January 29, 2020 04:00

January 28, 2020

Myrtle Enking

Idaho has a long history of women in the position of state treasurer. Julie Ellsworth (R) is Idaho’s current treasurer. Seven have held it previously, including, in reverse order, Lydia Justice Edwards (R), 1987-1998; Marjorie Ruth Moon (D), 1963-1986; Ruth Moon (D) (Marjorie’s mother), 1945-1946, and 1955-1959; Margaret Gilbert (R), 1952-1954; Lela D. Painter (R) (who died in office) 1947-1952; and Myrtle P. Enking, 1933-1944.

Enking was Idaho’s first female treasurer and the second female treasurer in the nation. Myrtle Powell graduated from high school in Avon, Illinois in 1898, and came to Idaho in 1909 to take a position as a bookkeeper at the Gooding Mercantile Company. She married William Enking in 1911. He passed away in 1913 leaving Myrtle with a son to raise.

Mrs. Enking was the first librarian of the Gooding Public Library and served as the Gooding County Auditor for 15 years before her successful run for state treasurer. In 1943, UPI Correspondent John Corlett called her “the greatest vote-getter in Idaho history.” There was speculation at that time that she might take on Congressman Henry Dworshak, but she did not. She was known for wearing tall hats, possibly because she stood only four foot eleven inches.

Myrtle Enking passed away in Boise in July, 1972 at the age of 92.

Enking was Idaho’s first female treasurer and the second female treasurer in the nation. Myrtle Powell graduated from high school in Avon, Illinois in 1898, and came to Idaho in 1909 to take a position as a bookkeeper at the Gooding Mercantile Company. She married William Enking in 1911. He passed away in 1913 leaving Myrtle with a son to raise.

Mrs. Enking was the first librarian of the Gooding Public Library and served as the Gooding County Auditor for 15 years before her successful run for state treasurer. In 1943, UPI Correspondent John Corlett called her “the greatest vote-getter in Idaho history.” There was speculation at that time that she might take on Congressman Henry Dworshak, but she did not. She was known for wearing tall hats, possibly because she stood only four foot eleven inches.

Myrtle Enking passed away in Boise in July, 1972 at the age of 92.

Published on January 28, 2020 04:00

January 27, 2020

Lulu Bell Parr, Daredevil

The myth of the Wild West became so ingrained in the story of our country that it sold well even in the West itself. Dime novels were popular everywhere and while cowboys were still plentiful on the range—they’re still not rare—wild west shows played to packed arenas.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show made at least one stop in Idaho Falls in the early part of the Twentieth Century. A competing spectacle, the “101 Ranch Show” played in Boise on June 17, 1912, a time when wagons were still more common than automobiles on the streets.

The 101 Ranch was a real place, an 87,000-acre spread in northeastern Oklahoma that was the largest diversified farm and ranch at the time, boasting, according to a 1905 Idaho Statesman article, 9,000 acres of wheat, 3,000 acres of corn, and 10,000 head of longhorn cattle. The wild west show was just one of their many enterprises.

During its 1912 visit to Boise the paper carried stories about the “Dare Devil Girls” of the 101 Ranch. The best-known cowgirl appearing was Lulu Bell Parr, who had also appeared in the Buffalo Bill’s shows. Lulu was your typical cowgirl, having grown up in Indiana, moving to Ohio when she got married in 1896. She was divorced in 1902 and by 1903 she was travelling in Europe with Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show.

The Statesman reported that she was one of the most “fearless riders and skillful manipulators of the lariat, [and was] to the manor born, for much of her life has been spent on a ranch, and the ranch life appeals to her as the only one that is really worthwhile.” One could be forgiven for wondering why she was performing in a string of wild west shows if green acres was the only place to be.

Still, she was a superb rider. “Many times,” the article said, “both on the cattle range and in the exhibitions of the 101 Ranch, Miss Parr has courted injury and possible death by her daredevil riding.” The preceding spring, in that well-known Cowtown, Philadelphia, she dared to ride “an outlaw pony that had defied nearly all the cowboys and other rough riders. She made the attempt and would have achieved an immediate victory over the vicious animal if her saddle girth had not slipped and thrown her to the ground. Notwithstanding the fact that she was momentarily stunned and received numerous painful bruises, the plucky little rider attempted the feat again the next day and triumphed over the animal.”

The wild west shows dwindled in popularity. By 1929 they were about dead. Lulu Bell Parr retired, broke and discouraged. She settled in Ohio where she lived with her brother until her death in 1960 at age 84.

#lulubellparr

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show made at least one stop in Idaho Falls in the early part of the Twentieth Century. A competing spectacle, the “101 Ranch Show” played in Boise on June 17, 1912, a time when wagons were still more common than automobiles on the streets.

The 101 Ranch was a real place, an 87,000-acre spread in northeastern Oklahoma that was the largest diversified farm and ranch at the time, boasting, according to a 1905 Idaho Statesman article, 9,000 acres of wheat, 3,000 acres of corn, and 10,000 head of longhorn cattle. The wild west show was just one of their many enterprises.

During its 1912 visit to Boise the paper carried stories about the “Dare Devil Girls” of the 101 Ranch. The best-known cowgirl appearing was Lulu Bell Parr, who had also appeared in the Buffalo Bill’s shows. Lulu was your typical cowgirl, having grown up in Indiana, moving to Ohio when she got married in 1896. She was divorced in 1902 and by 1903 she was travelling in Europe with Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show.

The Statesman reported that she was one of the most “fearless riders and skillful manipulators of the lariat, [and was] to the manor born, for much of her life has been spent on a ranch, and the ranch life appeals to her as the only one that is really worthwhile.” One could be forgiven for wondering why she was performing in a string of wild west shows if green acres was the only place to be.

Still, she was a superb rider. “Many times,” the article said, “both on the cattle range and in the exhibitions of the 101 Ranch, Miss Parr has courted injury and possible death by her daredevil riding.” The preceding spring, in that well-known Cowtown, Philadelphia, she dared to ride “an outlaw pony that had defied nearly all the cowboys and other rough riders. She made the attempt and would have achieved an immediate victory over the vicious animal if her saddle girth had not slipped and thrown her to the ground. Notwithstanding the fact that she was momentarily stunned and received numerous painful bruises, the plucky little rider attempted the feat again the next day and triumphed over the animal.”

The wild west shows dwindled in popularity. By 1929 they were about dead. Lulu Bell Parr retired, broke and discouraged. She settled in Ohio where she lived with her brother until her death in 1960 at age 84.

#lulubellparr

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Published on January 27, 2020 04:00

January 26, 2020

Mascots

There are 155 schools in the state that have mascots. I can’t name them all without a little help from my friend Google. You know who you are.

There are several unusual ones, i.e., the Bonneville Bees, the Malad Dragons, the American Falls Beavers, etc. The Soda Springs Cardinals? Really? Has anyone ever spotted one in Soda Springs?

According to Maxpreps.com, a website about high school sports, there are seven schools in Idaho that have unique mascot names. That is, no one else in the U.S. uses that mascot. They are the Orofino Maniacs (is anyone surprised?), the Kamiah Kubs (thanks to the spelling), the Kuna Kavemen (ditto), the Maranatha Christian Great Danes, the Cutthroats of the Community School in Sun Valley, the Shelley Russets, and the Camas County High School Mushers.

I would have thought the Clark Fork Wampus Cats might be unique. Nope. There are at least five other schools that use that name. The one in Conway, Arkansas has a claim to being unique among Wampus cats, though. Their mascot has six legs.

What is a Wampus cat? Clark Fork High School has its own legend. It’s also a half-dog, half-cat in Appalachian folklore. But I digress.

Back in Idaho we need to spotlight the Shelley Russets for their brave use of a vegetable as a mascot, albeit one wearing a crown. I couldn’t find another high school using a vegetable mascot, but Scottsdale Community College is proud of their Fighting Artichoke. There’s also a Fighting Okra at Delta State.

You will, no doubt, share your favorite mascot and/or vegetable observations.

There are several unusual ones, i.e., the Bonneville Bees, the Malad Dragons, the American Falls Beavers, etc. The Soda Springs Cardinals? Really? Has anyone ever spotted one in Soda Springs?

According to Maxpreps.com, a website about high school sports, there are seven schools in Idaho that have unique mascot names. That is, no one else in the U.S. uses that mascot. They are the Orofino Maniacs (is anyone surprised?), the Kamiah Kubs (thanks to the spelling), the Kuna Kavemen (ditto), the Maranatha Christian Great Danes, the Cutthroats of the Community School in Sun Valley, the Shelley Russets, and the Camas County High School Mushers.

I would have thought the Clark Fork Wampus Cats might be unique. Nope. There are at least five other schools that use that name. The one in Conway, Arkansas has a claim to being unique among Wampus cats, though. Their mascot has six legs.

What is a Wampus cat? Clark Fork High School has its own legend. It’s also a half-dog, half-cat in Appalachian folklore. But I digress.

Back in Idaho we need to spotlight the Shelley Russets for their brave use of a vegetable as a mascot, albeit one wearing a crown. I couldn’t find another high school using a vegetable mascot, but Scottsdale Community College is proud of their Fighting Artichoke. There’s also a Fighting Okra at Delta State.

You will, no doubt, share your favorite mascot and/or vegetable observations.

Published on January 26, 2020 04:00