Rick Just's Blog, page 171

February 14, 2020

Hugh Whitney Got Away, Part 2

This is part two of a three-part story about Hugh Whitney. Yesterday I told you about his robbing a saloon in Monida, Montana, then hopping on a train into Idaho. He was briefly arrested on board the train by a deputy who had gotten on in Spencer, Idaho for that purpose. When the cuffs came out he shot the deputy, then the train conductor. The latter later died.

The story was a sensation in Southeastern Idaho. Every paper carried updates on the search for Whitney. And what a search it was. Hundreds of men joined the effort within hours. Two groups got close to the escaped men, following them across the desert. Both times the pursuers backed away because of the hammering gunfire.

Somewhere near Hamer, the men split up. Whitney stole a horse at the McGill Ranch, shooting young Edgar McGill in the skirmish. Early reports were that Whitney had killed the youth, but he survived.

Authorities brought in bloodhounds from the Montana State Prison at Deer Lodge. They joined the lawmen and volunteers in the search but turned up only a shoplifter who was hiding out on the desert. A band of Blackfeet Indians joined the search, along with a hundred men from the Rigby area who were scouring the desert, mostly on horseback and with the aid of a couple of automobiles.

The Idaho Statesman reported that Whitney was likely somewhere between Blackfoot and Idaho Falls. The article said, “Until he shall faint from fatigue or fall before the guns of his hunters there will be no rest for isolated ranch families or the lonely sheepherders. New crimes are expected hourly as long as the desperate man is at large.”

Searchers thought that Whitney might try to cross the Menan Bridge to get back on the south side of the Snake where the going would be easier. They stationed Deputy Reuben Scott on the bridge with his rifle at the ready. Sure enough, here came Whitney riding his stolen horse across the planks at a slow clop.

“Halt and get off that horse,” Deputy Scott called out. Whitney replied, “Lookout, I’m a-coming’” and spurred his steed to a gallop. He took a running aim at the lawman and fired once. Scott’s rifle dropped to the ground, as did three of his fingers. Hugh Whitney got away.

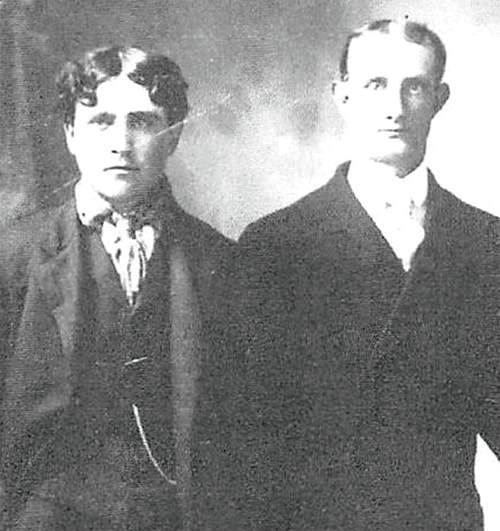

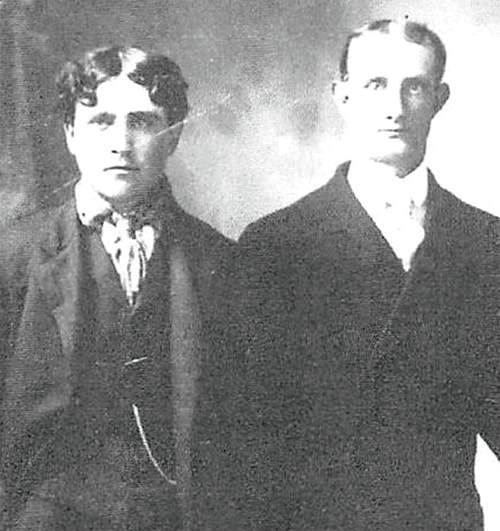

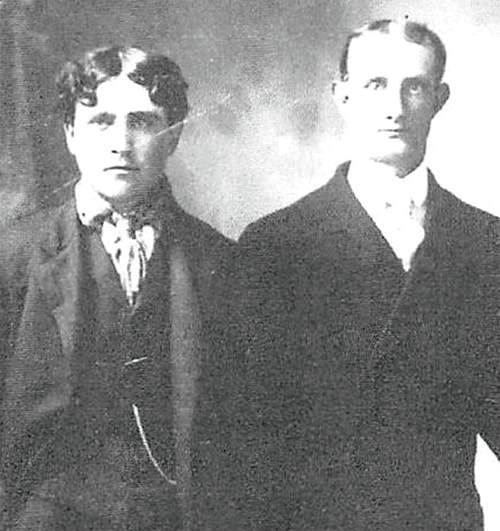

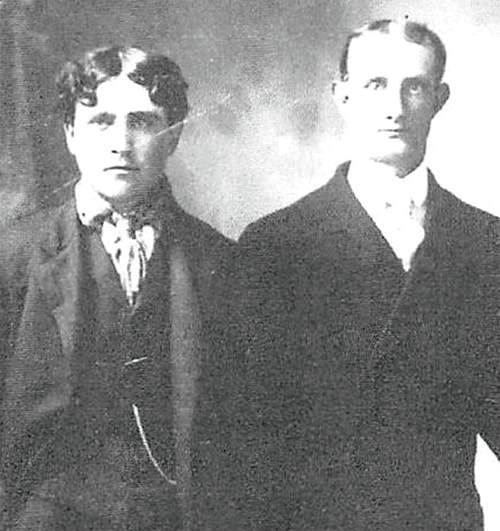

Check back tomorrow for the conclusion of this three-part story. Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

The story was a sensation in Southeastern Idaho. Every paper carried updates on the search for Whitney. And what a search it was. Hundreds of men joined the effort within hours. Two groups got close to the escaped men, following them across the desert. Both times the pursuers backed away because of the hammering gunfire.

Somewhere near Hamer, the men split up. Whitney stole a horse at the McGill Ranch, shooting young Edgar McGill in the skirmish. Early reports were that Whitney had killed the youth, but he survived.

Authorities brought in bloodhounds from the Montana State Prison at Deer Lodge. They joined the lawmen and volunteers in the search but turned up only a shoplifter who was hiding out on the desert. A band of Blackfeet Indians joined the search, along with a hundred men from the Rigby area who were scouring the desert, mostly on horseback and with the aid of a couple of automobiles.

The Idaho Statesman reported that Whitney was likely somewhere between Blackfoot and Idaho Falls. The article said, “Until he shall faint from fatigue or fall before the guns of his hunters there will be no rest for isolated ranch families or the lonely sheepherders. New crimes are expected hourly as long as the desperate man is at large.”

Searchers thought that Whitney might try to cross the Menan Bridge to get back on the south side of the Snake where the going would be easier. They stationed Deputy Reuben Scott on the bridge with his rifle at the ready. Sure enough, here came Whitney riding his stolen horse across the planks at a slow clop.

“Halt and get off that horse,” Deputy Scott called out. Whitney replied, “Lookout, I’m a-coming’” and spurred his steed to a gallop. He took a running aim at the lawman and fired once. Scott’s rifle dropped to the ground, as did three of his fingers. Hugh Whitney got away.

Check back tomorrow for the conclusion of this three-part story.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Published on February 14, 2020 04:00

February 13, 2020

Hugh Whitney Got Away

That headline would have sufficed a couple dozen times in newspapers across Idaho, Oregon, and Wyoming beginning in June 1911. The details of each story changed, but the headline would serve well enough.

This story is much longer than my usual posts, so I’m going to break it into three parts. Come back the next two days to find out what happened.

For all his escapes to come, Hugh Whitney started out his life of crime in such a reckless way his eventual capture would seem a certainty. He and an accomplice, perhaps his older brother Charlie or a man named Sesker, robbed a saloon in Monida, Montana on June 17, 1911. It would come out later that Whitney may have felt he was owed the money he stole. He had been drinking in the establishment the night before. He was blind drunk, and somehow lost what money he had, whether to a robber or in a card game is unclear.

On that Saturday morning Whitney and his friend went back to the pool hall, guns drawn, not bothering to cover their faces. They had a few free drinks, stole a little cash and whiskey, and sauntered down the street to the train station, where they casually bought tickets that would take them into Idaho.

The saloon keep telephoned Fremont County Deputy Sheriff Samuel Melton to report the robbery. Melton caught the train at Spencer. It didn’t take him long to find Hugh Whitney and the other man in the smoking room playing a game of cards with a couple of traveling men. Melton pulled his gun on the men and placed them under arrest. They laid their own guns on the table where the card game was taking place.

When Melton tried to cuff Whitney, the latter leapt for his gun, grabbed it, and fired twice into the deputy’s body. Melton was hit in the shoulder and chest. The train’s conductor, William Kidd, arrived on the scene at that time. He grabbed Whitney, but the robber shot him once in the chest. The conductor slumped over a seat.

Slipping quietly away at that point might have been the better course of action for Whitney and his partner. Instead, they made their way through the cars of the train blazing away randomly with guns in each hand. Whitney pulled the signal cord, then waited as the train slowed to a stop. He casually walked down the steps of the train, then turned and began firing into the cars as he backed away. This seemed meant to discourage pursuit. Just before he disappeared into the sagebrush, Whitney doffed his hat and waved it theatrically at the passengers.

Conductor Kidd died the next day in a Pocatello Hospital. Deputy Melton struggled near death for weeks but ultimately survived. Hugh Whitney got away.

We'll continue the story tomorrow.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

This story is much longer than my usual posts, so I’m going to break it into three parts. Come back the next two days to find out what happened.

For all his escapes to come, Hugh Whitney started out his life of crime in such a reckless way his eventual capture would seem a certainty. He and an accomplice, perhaps his older brother Charlie or a man named Sesker, robbed a saloon in Monida, Montana on June 17, 1911. It would come out later that Whitney may have felt he was owed the money he stole. He had been drinking in the establishment the night before. He was blind drunk, and somehow lost what money he had, whether to a robber or in a card game is unclear.

On that Saturday morning Whitney and his friend went back to the pool hall, guns drawn, not bothering to cover their faces. They had a few free drinks, stole a little cash and whiskey, and sauntered down the street to the train station, where they casually bought tickets that would take them into Idaho.

The saloon keep telephoned Fremont County Deputy Sheriff Samuel Melton to report the robbery. Melton caught the train at Spencer. It didn’t take him long to find Hugh Whitney and the other man in the smoking room playing a game of cards with a couple of traveling men. Melton pulled his gun on the men and placed them under arrest. They laid their own guns on the table where the card game was taking place.

When Melton tried to cuff Whitney, the latter leapt for his gun, grabbed it, and fired twice into the deputy’s body. Melton was hit in the shoulder and chest. The train’s conductor, William Kidd, arrived on the scene at that time. He grabbed Whitney, but the robber shot him once in the chest. The conductor slumped over a seat.

Slipping quietly away at that point might have been the better course of action for Whitney and his partner. Instead, they made their way through the cars of the train blazing away randomly with guns in each hand. Whitney pulled the signal cord, then waited as the train slowed to a stop. He casually walked down the steps of the train, then turned and began firing into the cars as he backed away. This seemed meant to discourage pursuit. Just before he disappeared into the sagebrush, Whitney doffed his hat and waved it theatrically at the passengers.

Conductor Kidd died the next day in a Pocatello Hospital. Deputy Melton struggled near death for weeks but ultimately survived. Hugh Whitney got away.

We'll continue the story tomorrow.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Published on February 13, 2020 04:00

February 12, 2020

The Man Who Invented Idaho

Today is Abraham Lincoln's birthday. In honor of that I'm going to be giving a brief presentation to the Idaho Senate about Idaho's connections with this great man. The following is a repeat of a post I did about 18 months ago. It contains much of what I'm going to share with the Idaho Senate today.

I love odd little connections. Idaho has a ton of them with Abraham Lincoln. So many that they have become an obsession with Lincoln scholar and former Idaho Attorney General David Leroy.

Leroy has spent a lifetime collecting Lincoln memorabilia and documenting his connections with Idaho. The most visible result of his passion is the exhibit Abraham Lincoln, His Legacy in Idaho at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. Donated by David and Nancy Leroy in 2010, the exceptional exhibit displays more than 200 documents and artifacts.

So, what are the connections? Lincoln personally lobbied Congress for the creation of Idaho Territory, and signed that creation into law on March 3, 1863. But his interest in what would become our state started much earlier. Lincoln sought to be Idaho’s governor. Well, not exactly, but he did seek to govern Oregon Territory in 1849, part of which would one day become Idaho.

Lincoln was there at a meeting where it was decided the name of the new territory would be Idaho.

Many of the Lincoln connections were by way of Illinois and Indiana. Friends and neighbors of his helped shape the state. Samuel C. Parks, a law partner, was the territory’s first associate Supreme Court Justice. Another friend was Idaho’s seventh territorial governor, Mason Brayman. Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, sought appointment as a territorial governor of Idaho from Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but did not get it.

Years after Lincoln’s death a childhood playmate of Lincoln’s sons became U.S. Marshall of Idaho Territory, then a territorial congressional delegate. Fred T. Dubois lobbied hard to create the State of Idaho and to keep it from being split off and claimed by its neighbors.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, April 14, 1865, he had a meeting with Idaho’s delegate, William H. Wallace, about filling an Idaho supreme court vacancy. Wallace was said to have been invited to see a play that night with the Lincolns. He declined.

There’s a terrific little book about Lincoln’s connections to Idaho called Lincoln Never Slept Here, Idaho’s Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Tour written by Todd Shallat, PhD with Kathleen Craven Tuck Tuck.

#idahostatehistoricalarchives #Lincoln #abrahamlincoln #idahohistory

Boise's Lincoln statues.

Boise's Lincoln statues.

I love odd little connections. Idaho has a ton of them with Abraham Lincoln. So many that they have become an obsession with Lincoln scholar and former Idaho Attorney General David Leroy.

Leroy has spent a lifetime collecting Lincoln memorabilia and documenting his connections with Idaho. The most visible result of his passion is the exhibit Abraham Lincoln, His Legacy in Idaho at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. Donated by David and Nancy Leroy in 2010, the exceptional exhibit displays more than 200 documents and artifacts.

So, what are the connections? Lincoln personally lobbied Congress for the creation of Idaho Territory, and signed that creation into law on March 3, 1863. But his interest in what would become our state started much earlier. Lincoln sought to be Idaho’s governor. Well, not exactly, but he did seek to govern Oregon Territory in 1849, part of which would one day become Idaho.

Lincoln was there at a meeting where it was decided the name of the new territory would be Idaho.

Many of the Lincoln connections were by way of Illinois and Indiana. Friends and neighbors of his helped shape the state. Samuel C. Parks, a law partner, was the territory’s first associate Supreme Court Justice. Another friend was Idaho’s seventh territorial governor, Mason Brayman. Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, sought appointment as a territorial governor of Idaho from Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but did not get it.

Years after Lincoln’s death a childhood playmate of Lincoln’s sons became U.S. Marshall of Idaho Territory, then a territorial congressional delegate. Fred T. Dubois lobbied hard to create the State of Idaho and to keep it from being split off and claimed by its neighbors.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, April 14, 1865, he had a meeting with Idaho’s delegate, William H. Wallace, about filling an Idaho supreme court vacancy. Wallace was said to have been invited to see a play that night with the Lincolns. He declined.

There’s a terrific little book about Lincoln’s connections to Idaho called Lincoln Never Slept Here, Idaho’s Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Tour written by Todd Shallat, PhD with Kathleen Craven Tuck Tuck.

#idahostatehistoricalarchives #Lincoln #abrahamlincoln #idahohistory

Boise's Lincoln statues.

Boise's Lincoln statues.

Published on February 12, 2020 04:00

February 11, 2020

Dorthy Johnson

Largely because of the activities of the now defunct Aryan Nations, there is a lingering perception nationally that Idaho is not a place that welcomes diversity. Statistically, it is not a very diverse state. According to the Census Bureau, African-Americans made up just .06% of the state during the most recent census in 2010. It was about the same in 1964, when an African-American woman from Pocatello was chosen as Miss Idaho.

Yes, right in the middle of the civil rights movement, Idaho sent a woman of color to the Miss USA pageant. Nineteen-year-old Dorthy (sic) Johnson was not the first African-American woman to compete in the pageant. That distinction went to Corinne Huff who served as an alternate for Miss Ohio in 1960. But Johnson was the first African-American semi-finalist in the pageant.

There have since been six African-American winners of the pageant, since. The first was Carole Gist, Miss Michigan, in 1990.

Idaho’s Dorthy Johnson would go on to become an award-winning educator. She was the Los Angeles Reading Association’s Teacher of the Year in 1992, listed in Who’s Who Among America’s Teachers, and nominated for the Disney Teacher of the Year Award in 2002. Dorthy Johnson LeVels passed away in the town where she was born, Pocatello, in April 2017.

Yes, right in the middle of the civil rights movement, Idaho sent a woman of color to the Miss USA pageant. Nineteen-year-old Dorthy (sic) Johnson was not the first African-American woman to compete in the pageant. That distinction went to Corinne Huff who served as an alternate for Miss Ohio in 1960. But Johnson was the first African-American semi-finalist in the pageant.

There have since been six African-American winners of the pageant, since. The first was Carole Gist, Miss Michigan, in 1990.

Idaho’s Dorthy Johnson would go on to become an award-winning educator. She was the Los Angeles Reading Association’s Teacher of the Year in 1992, listed in Who’s Who Among America’s Teachers, and nominated for the Disney Teacher of the Year Award in 2002. Dorthy Johnson LeVels passed away in the town where she was born, Pocatello, in April 2017.

Published on February 11, 2020 04:00

February 10, 2020

Vardis Fisher's Boise

The name of Rediscovered Books, with stores in Boise and Caldwell, was never more appropriate than in January when their publishing arm brought out

Vardis Fisher’s Boise

.* Fisher began writing the guidebook in 1937. The manuscript would rest in a file folder at the Library of Congress for 80 years before it was discovered—rediscovered—by Boise State University archivist Alessandro Meregaglia.

Before I get to the book itself, I need to explain a thing or two, not least who Vardis Fisher was.

Fisher was Idaho’s best-known author for decades. If the question “What about Hemingway?” popped into your head I wouldn’t be surprised. Ernest Hemingway did some important writing while residing in Idaho, but he wasn’t born here. Vardis Fisher was, along the Snake River near Rigby.

Best known today for his 1965 novel Mountain Man: A Novel of Male and Female .* Fisher wrote 29 novels and nine nonfiction books in his long career. That 1965 novel was made into the movie Jerimiah Johnson in 1972, thus its lingering fame. Most of his other work has been forgotten by the general public.

Idaho historians know Fisher well, though. He was really Idaho’s only well-known writer in 1935 when he was named director of the Idaho Writers Project. Every state had a similar project, sponsored by the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), a program of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Project Administration. It was a New Deal program meant to put writers to work during the Great Depression.

In Idaho, it mostly put one writer to work, Vardis Fisher. That writer was one hard worker. Three books came out of the Writers’ Project, Idaho: A Guide in Word and Picture (1937), The Idaho Encyclopedia (1938), and Idaho Lore (1939).* Fisher was so prolific that he beat all the other states to press with the Idaho guide, much to the chagrin of FWP officials in Washington, DC, who had planned a book on the nation’s capital to be the first in the nationwide guidebook series.

All three books were produced by Caxton Printers of Caldwell, the company that had published Fisher’s five novels (at that time). Publisher James H. Gipson and Vardis Fisher were great friends. They planned on publishing at least one more book together for the Federal Writers’ Project, a guidebook to Boise.

Fisher largely wrote without a filter. That is, he wrote exactly what he thought. The manuscript for the Boise guidebook has whole section of raw Fisher commentary crossed out by editors in DC. To their credit, Rediscovered Publishing ignored most of that, sticking closely to the original manuscript.

But those crossed-out comments are probably what kept the book unpublished in its day. One of the rules of the Federal Writers’ Project was that each book had to have a sponsor. Someone in an official capacity had to put their imprimatur on each book before it could be published. In the case of the Boise book the mayor, the chamber of commerce, even the secretary of state would do. No one was willing to bless it. That’s why the manuscript got boxed up with other material from the federal project and shipped to Washington, DC where Alessandro Meregaglia would finally find it, chasing it down after reading a footnote about it in a book on the FWP.

So, why wouldn’t anyone in an official capacity in Idaho give the book their blessing? Read the first couple of sentences from the main body of the book for a clue.

“As cities go, Boise is physically attractive, but it is the trees and not the buildings that make it so. Like cities everywhere it suffers from want of congruity and planning structures, and so presents the appearance of having grown up in a burst of individualism, with no regard in any building for those around it.”

Fisher’s Boise guide had an honesty about it that those familiar with boosterism books would not recognize. His writing is generally not derogatory. It is simply viewed with a critical eye.

Fisher blamed politics for not being able to secure a sponsor for his book, finding Republicans lodged solidly in every institution he approached. FDR’s New Deal and its Federal Writers’ Project were not popular with GOP members.

Vardis Fisher’s Boise is a snapshot of history from more than 80 years ago, at last unearthed like the product of an archeological dig. Spend a few minutes with it and you’ll learn why Fisher was considered one of the great writers of his time.

Note that Idaho Press contributor Tim Woodward wrote the biography of Vardis Fisher. It is called Tiger on the Road .*

J.H. Gipson and Vardis Fisher stand outside the Caxton offices in Caldwell. Photo from the Vardis and Opal Fisher Papers.

J.H. Gipson and Vardis Fisher stand outside the Caxton offices in Caldwell. Photo from the Vardis and Opal Fisher Papers.

Courtesy of Boise State Special Collections and Archives

Before I get to the book itself, I need to explain a thing or two, not least who Vardis Fisher was.

Fisher was Idaho’s best-known author for decades. If the question “What about Hemingway?” popped into your head I wouldn’t be surprised. Ernest Hemingway did some important writing while residing in Idaho, but he wasn’t born here. Vardis Fisher was, along the Snake River near Rigby.

Best known today for his 1965 novel Mountain Man: A Novel of Male and Female .* Fisher wrote 29 novels and nine nonfiction books in his long career. That 1965 novel was made into the movie Jerimiah Johnson in 1972, thus its lingering fame. Most of his other work has been forgotten by the general public.

Idaho historians know Fisher well, though. He was really Idaho’s only well-known writer in 1935 when he was named director of the Idaho Writers Project. Every state had a similar project, sponsored by the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), a program of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Project Administration. It was a New Deal program meant to put writers to work during the Great Depression.

In Idaho, it mostly put one writer to work, Vardis Fisher. That writer was one hard worker. Three books came out of the Writers’ Project, Idaho: A Guide in Word and Picture (1937), The Idaho Encyclopedia (1938), and Idaho Lore (1939).* Fisher was so prolific that he beat all the other states to press with the Idaho guide, much to the chagrin of FWP officials in Washington, DC, who had planned a book on the nation’s capital to be the first in the nationwide guidebook series.

All three books were produced by Caxton Printers of Caldwell, the company that had published Fisher’s five novels (at that time). Publisher James H. Gipson and Vardis Fisher were great friends. They planned on publishing at least one more book together for the Federal Writers’ Project, a guidebook to Boise.

Fisher largely wrote without a filter. That is, he wrote exactly what he thought. The manuscript for the Boise guidebook has whole section of raw Fisher commentary crossed out by editors in DC. To their credit, Rediscovered Publishing ignored most of that, sticking closely to the original manuscript.

But those crossed-out comments are probably what kept the book unpublished in its day. One of the rules of the Federal Writers’ Project was that each book had to have a sponsor. Someone in an official capacity had to put their imprimatur on each book before it could be published. In the case of the Boise book the mayor, the chamber of commerce, even the secretary of state would do. No one was willing to bless it. That’s why the manuscript got boxed up with other material from the federal project and shipped to Washington, DC where Alessandro Meregaglia would finally find it, chasing it down after reading a footnote about it in a book on the FWP.

So, why wouldn’t anyone in an official capacity in Idaho give the book their blessing? Read the first couple of sentences from the main body of the book for a clue.

“As cities go, Boise is physically attractive, but it is the trees and not the buildings that make it so. Like cities everywhere it suffers from want of congruity and planning structures, and so presents the appearance of having grown up in a burst of individualism, with no regard in any building for those around it.”

Fisher’s Boise guide had an honesty about it that those familiar with boosterism books would not recognize. His writing is generally not derogatory. It is simply viewed with a critical eye.

Fisher blamed politics for not being able to secure a sponsor for his book, finding Republicans lodged solidly in every institution he approached. FDR’s New Deal and its Federal Writers’ Project were not popular with GOP members.

Vardis Fisher’s Boise is a snapshot of history from more than 80 years ago, at last unearthed like the product of an archeological dig. Spend a few minutes with it and you’ll learn why Fisher was considered one of the great writers of his time.

Note that Idaho Press contributor Tim Woodward wrote the biography of Vardis Fisher. It is called Tiger on the Road .*

J.H. Gipson and Vardis Fisher stand outside the Caxton offices in Caldwell. Photo from the Vardis and Opal Fisher Papers.

J.H. Gipson and Vardis Fisher stand outside the Caxton offices in Caldwell. Photo from the Vardis and Opal Fisher Papers.Courtesy of Boise State Special Collections and Archives

Published on February 10, 2020 04:00

February 9, 2020

Idahoans at Wake Island

The 1940 Fourth of July headline in The Idaho Statesman was about a contract local construction company Morrison-Knudsen had just won. “Boise Company Builds Bases,” the headline on page 3 read. No one knew how quickly that story would move to the front page, impacting Idaho families for years to come.

Harry Morrison, president of MK, had just returned from Washington, D.C. with the good news that the company had been awarded a substantial portion of construction under the National Defense Program, building air base facilities in the South Pacific. Midway and Wake Islands were mentioned in passing.

The story moved to page 2 in the Statesman on March 20, 1941, when it was announced that 150 workers, many of them from the Boise area, would sail from San Francisco for Wake Island. The company would be sending men “from engineers to dishwashers” to help build the air base.

Another page 2 article a couple of weeks later told that “several Canyon County young men (had) been given draft deferments to go to Wake Island where they would be employed by Morrison-Knudsen Construction.”

Over the course of the next few months there followed many articles about individual men on their way to build the air base in the South Pacific.

On September 19, 1941, the newspaper ran a story about the impressions of O.O. Kelso, from Caldwell. Headlined, “Idahoan Finds Wake Island ‘Crazy Place,’” it quoted Kelso as saying “rocks float; wood sinks; fish fly, and we have a bird here that runs but can’t fly.”

It got much crazier. On December 8, 1941, the day after that “Day of Infamy” at Pearl Harbor, there was a report the Japanese had taken Wake Island. This caused great concern in the Boise area, of course, because of the MK project there.

The family of 19-year-old Joe Goicoechea was on tenterhooks. He was among the civilian employees of MK on Wake Island. His dream job there—paying $120 a month—would turn into a nightmare as he and other Morrison-Knudsen employees took up arms alongside soldiers. They held off the attackers from December 8 until Christmas Eve, when he and hundreds of others were taken prisoner.

The Japanese forced the prisoners to build bunkers and fortifications against an American counter-attack. That flightless bird that O.O. Kelso mentioned, was hunted to extinction by the Japanese when the blockade by American forces brought their garrison to the point of starvation.

Goicoechea and others captured ended up spending 46 months in captivity, which included a starvation diet, inadequate clothing against the cold, and torture.

There were 1,100 Morrison-Knudson men on Wake Island on December 7, 1941. Only 700 made it home. Forty-seven died defending the island. Ninety-eight were executed by the Japanese. About a third of the men died in captivity under harsh conditions.

Joe Goicoechea made it back to Idaho. He lived until January, 2017. The Idaho Statesman reported upon his death that Goicoechea was thought to be the last of the Morrison-Knudson men who had experienced the battle on Wake Island and subsequent imprisonment to die.

The "98 Rock" is a memorial for the 98 U.S. civilian contract POWs who were forced by their Japanese captors to rebuild the airstrip as slave labor, then were blindfolded and killed by machine gun Oct. 5, 1943. An unidentified prisoner escaped, and chiseled "98 US PW 5-10-43" on a large coral rock near their mass grave, on Wilkes Island at the edge of the lagoon. The prisoner was recaptured and beheaded by the Japanese admiral, who was later convicted and executed for war crimes. (U.S. Air Force photo/Tech. Sgt. Shane A. Cuomo)

The "98 Rock" is a memorial for the 98 U.S. civilian contract POWs who were forced by their Japanese captors to rebuild the airstrip as slave labor, then were blindfolded and killed by machine gun Oct. 5, 1943. An unidentified prisoner escaped, and chiseled "98 US PW 5-10-43" on a large coral rock near their mass grave, on Wilkes Island at the edge of the lagoon. The prisoner was recaptured and beheaded by the Japanese admiral, who was later convicted and executed for war crimes. (U.S. Air Force photo/Tech. Sgt. Shane A. Cuomo)

Harry Morrison, president of MK, had just returned from Washington, D.C. with the good news that the company had been awarded a substantial portion of construction under the National Defense Program, building air base facilities in the South Pacific. Midway and Wake Islands were mentioned in passing.

The story moved to page 2 in the Statesman on March 20, 1941, when it was announced that 150 workers, many of them from the Boise area, would sail from San Francisco for Wake Island. The company would be sending men “from engineers to dishwashers” to help build the air base.

Another page 2 article a couple of weeks later told that “several Canyon County young men (had) been given draft deferments to go to Wake Island where they would be employed by Morrison-Knudsen Construction.”

Over the course of the next few months there followed many articles about individual men on their way to build the air base in the South Pacific.

On September 19, 1941, the newspaper ran a story about the impressions of O.O. Kelso, from Caldwell. Headlined, “Idahoan Finds Wake Island ‘Crazy Place,’” it quoted Kelso as saying “rocks float; wood sinks; fish fly, and we have a bird here that runs but can’t fly.”

It got much crazier. On December 8, 1941, the day after that “Day of Infamy” at Pearl Harbor, there was a report the Japanese had taken Wake Island. This caused great concern in the Boise area, of course, because of the MK project there.

The family of 19-year-old Joe Goicoechea was on tenterhooks. He was among the civilian employees of MK on Wake Island. His dream job there—paying $120 a month—would turn into a nightmare as he and other Morrison-Knudsen employees took up arms alongside soldiers. They held off the attackers from December 8 until Christmas Eve, when he and hundreds of others were taken prisoner.

The Japanese forced the prisoners to build bunkers and fortifications against an American counter-attack. That flightless bird that O.O. Kelso mentioned, was hunted to extinction by the Japanese when the blockade by American forces brought their garrison to the point of starvation.

Goicoechea and others captured ended up spending 46 months in captivity, which included a starvation diet, inadequate clothing against the cold, and torture.

There were 1,100 Morrison-Knudson men on Wake Island on December 7, 1941. Only 700 made it home. Forty-seven died defending the island. Ninety-eight were executed by the Japanese. About a third of the men died in captivity under harsh conditions.

Joe Goicoechea made it back to Idaho. He lived until January, 2017. The Idaho Statesman reported upon his death that Goicoechea was thought to be the last of the Morrison-Knudson men who had experienced the battle on Wake Island and subsequent imprisonment to die.

The "98 Rock" is a memorial for the 98 U.S. civilian contract POWs who were forced by their Japanese captors to rebuild the airstrip as slave labor, then were blindfolded and killed by machine gun Oct. 5, 1943. An unidentified prisoner escaped, and chiseled "98 US PW 5-10-43" on a large coral rock near their mass grave, on Wilkes Island at the edge of the lagoon. The prisoner was recaptured and beheaded by the Japanese admiral, who was later convicted and executed for war crimes. (U.S. Air Force photo/Tech. Sgt. Shane A. Cuomo)

The "98 Rock" is a memorial for the 98 U.S. civilian contract POWs who were forced by their Japanese captors to rebuild the airstrip as slave labor, then were blindfolded and killed by machine gun Oct. 5, 1943. An unidentified prisoner escaped, and chiseled "98 US PW 5-10-43" on a large coral rock near their mass grave, on Wilkes Island at the edge of the lagoon. The prisoner was recaptured and beheaded by the Japanese admiral, who was later convicted and executed for war crimes. (U.S. Air Force photo/Tech. Sgt. Shane A. Cuomo)

Published on February 09, 2020 04:00

February 8, 2020

A Moscow Fire

On March 29, 1906 debate teams from the universities of Washington and Idaho met at the University of Idaho in a hard-fought academic contest that was witnessed by some 300 people. The debate was held in the university’s administration building, which served many functions on the campus, including as the home of the library. The contest was close, but the University of Washington team took home the trophy. The debaters and the audience left the building at 11 that night.

At 2:30 the next morning, Assistant Janitor J.F. Williams, who slept in the building, smelled smoke. He quickly discovered a fire in the basement stairway near the girl’s rest room. He immediately sounded the alarm.

Within minutes a hose company appeared on the scene and began sending streams of water into the building. They hoped to contain the fire to the basement. When that didn’t work, they tried containing the flames to the south wing.

Half the population of Moscow came out to see the conflagration. It lit up the sky like a second sun. While they stood watching the cupola with its topping flagpole twisted slowly and sank into the ruins. The towers fell next, one after another. In a few hours only the skeleton of the building remained.

Students and teachers scrambled to save records and artifacts. They could not save the seven pianos, a professor’s lifetime entomological collection, and museum artifacts. The library was a total loss.

That exact cause of the blaze that brought down the building, valued at $200,000, was never determined. Construction of the administration building had begun in 1892. It had served as the most important building on campus for just 14 years.

The University of Idaho Administration Building in the 1890s. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.

The University of Idaho Administration Building in the 1890s. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.  The same building at the moment of its demolition after the 1906 fire. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.

The same building at the moment of its demolition after the 1906 fire. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.

At 2:30 the next morning, Assistant Janitor J.F. Williams, who slept in the building, smelled smoke. He quickly discovered a fire in the basement stairway near the girl’s rest room. He immediately sounded the alarm.

Within minutes a hose company appeared on the scene and began sending streams of water into the building. They hoped to contain the fire to the basement. When that didn’t work, they tried containing the flames to the south wing.

Half the population of Moscow came out to see the conflagration. It lit up the sky like a second sun. While they stood watching the cupola with its topping flagpole twisted slowly and sank into the ruins. The towers fell next, one after another. In a few hours only the skeleton of the building remained.

Students and teachers scrambled to save records and artifacts. They could not save the seven pianos, a professor’s lifetime entomological collection, and museum artifacts. The library was a total loss.

That exact cause of the blaze that brought down the building, valued at $200,000, was never determined. Construction of the administration building had begun in 1892. It had served as the most important building on campus for just 14 years.

The University of Idaho Administration Building in the 1890s. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.

The University of Idaho Administration Building in the 1890s. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.  The same building at the moment of its demolition after the 1906 fire. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.

The same building at the moment of its demolition after the 1906 fire. Photo courtesy of the Hugh Hartman Collection.

Published on February 08, 2020 04:00

February 7, 2020

The Snake River's Lost Falls

Shoshone Falls, though largely captured for most of the year to run turbines for power generation, does sometimes run wild in the spring, giving us a taste of what it once looked like. We can see the free-falling water at Mesa Falls anytime, since it is the last large, unfettered falls on the Snake River.

Did you ever wonder what American Falls looked like prior to the building of the dam?

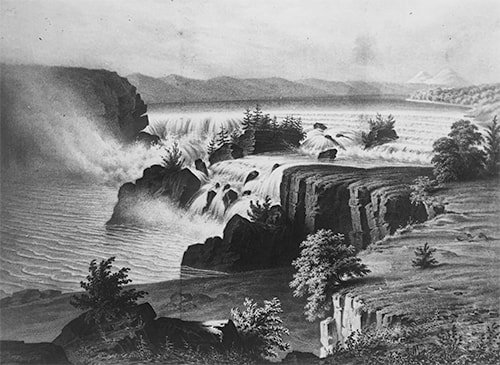

The earliest depiction of the falls that I’m aware of is a lithograph (above) of the American Falls from a sketch by Charles Preuss. It appeared in John Charles Fremont’s first report to congress on his western explorations. Preuss was the cartographer for the expedition. His 1843 sketch of the falls is one of the earliest depictions of anything in what is now Eastern Idaho.

The earliest depiction of the falls that I’m aware of is a lithograph (above) of the American Falls from a sketch by Charles Preuss. It appeared in John Charles Fremont’s first report to congress on his western explorations. Preuss was the cartographer for the expedition. His 1843 sketch of the falls is one of the earliest depictions of anything in what is now Eastern Idaho.

The sketch shows a dramatic drop of water, split by a rock island. But one must take the accuracy with a grain of salt. As stated in the book One Hundred Years of Idaho Art, 1850-1950 ,* by Sandy Harthorn and Kathleen Bettis, “Because Preuss was trained as a cartographer and not an artist, we can accept that his rather naïve drawings outline the land features rather than describe them as solid forms. Drawn in a stiff awkward manner, this deep vista appears exaggerated and fanciful. The river drops from a flattened plain over the edge of an angulated precipice more illusory than real.” A second, more detailed lithograph (above) was published in 1848. Though still depicting mountains in the background that are a little fanciful It shows a waterfall you’d certainly want to portage, unless you’re one of the kayakers who relishes a first drop. It looks about as daunting as Lower Mesa Falls, which kayakers occasionally run and live to tell about it.

A second, more detailed lithograph (above) was published in 1848. Though still depicting mountains in the background that are a little fanciful It shows a waterfall you’d certainly want to portage, unless you’re one of the kayakers who relishes a first drop. It looks about as daunting as Lower Mesa Falls, which kayakers occasionally run and live to tell about it.  Finally, here’s a photo from the early 1900s, well before the dam went in (1925). The locomotive steaming across the trestle is on the Oregon Shortline tracks, westbound.

Finally, here’s a photo from the early 1900s, well before the dam went in (1925). The locomotive steaming across the trestle is on the Oregon Shortline tracks, westbound.

Did you ever wonder what American Falls looked like prior to the building of the dam?

The earliest depiction of the falls that I’m aware of is a lithograph (above) of the American Falls from a sketch by Charles Preuss. It appeared in John Charles Fremont’s first report to congress on his western explorations. Preuss was the cartographer for the expedition. His 1843 sketch of the falls is one of the earliest depictions of anything in what is now Eastern Idaho.

The earliest depiction of the falls that I’m aware of is a lithograph (above) of the American Falls from a sketch by Charles Preuss. It appeared in John Charles Fremont’s first report to congress on his western explorations. Preuss was the cartographer for the expedition. His 1843 sketch of the falls is one of the earliest depictions of anything in what is now Eastern Idaho.The sketch shows a dramatic drop of water, split by a rock island. But one must take the accuracy with a grain of salt. As stated in the book One Hundred Years of Idaho Art, 1850-1950 ,* by Sandy Harthorn and Kathleen Bettis, “Because Preuss was trained as a cartographer and not an artist, we can accept that his rather naïve drawings outline the land features rather than describe them as solid forms. Drawn in a stiff awkward manner, this deep vista appears exaggerated and fanciful. The river drops from a flattened plain over the edge of an angulated precipice more illusory than real.”

A second, more detailed lithograph (above) was published in 1848. Though still depicting mountains in the background that are a little fanciful It shows a waterfall you’d certainly want to portage, unless you’re one of the kayakers who relishes a first drop. It looks about as daunting as Lower Mesa Falls, which kayakers occasionally run and live to tell about it.

A second, more detailed lithograph (above) was published in 1848. Though still depicting mountains in the background that are a little fanciful It shows a waterfall you’d certainly want to portage, unless you’re one of the kayakers who relishes a first drop. It looks about as daunting as Lower Mesa Falls, which kayakers occasionally run and live to tell about it.  Finally, here’s a photo from the early 1900s, well before the dam went in (1925). The locomotive steaming across the trestle is on the Oregon Shortline tracks, westbound.

Finally, here’s a photo from the early 1900s, well before the dam went in (1925). The locomotive steaming across the trestle is on the Oregon Shortline tracks, westbound.

Published on February 07, 2020 04:00

February 6, 2020

A Man Worth His Salt

In the 1860s many men were trying to make their fortunes in Idaho. Most were miners hoping to strike it rich. A few provided the necessities miners needed from gold pans to flour. Others prospered by providing not for miner’s needs, but for their desires. Think saloons and all they entailed.

There were a couple of men who set out to mine for what miners needed. They provided one of life’s basic necessities, salt.

Benjamin Franklin White and J.H. Stump began mining salt in Idaho in 1866, at Stump Creek, which is on the Idaho-Wyoming border about 50 miles north of Soda Springs. Stump Creek runs a little salty, about 60 percent. Coaxing the salt out of the water was easily done. All you had to do was let the water evaporate and it would leave salt behind. That was fine if you wanted to fill your shaker, but if you wanted salt in commercial quantities you needed to boil the water away.

That’s what White and Stump did. They built wooden flumes to carry the water into several large galvanized iron pots where the water was boiled away. The salt was shoveled out every 30 minutes. Workers let it drain for about 24 hours then put it in drying houses where it “ripened” for two to four months.

This was no small operation. At the peak of production, the Oneida Salt Works was processing two million pounds a year. Some 300 teams were employed hauling wagonloads of salt, much of it to Montana along the “Salt Road,” also known as the Lander Trail. Each “team” was a triple-wagon setup hitched together and pulled by nine yoke of oxen. The operation lasted some 30 years.

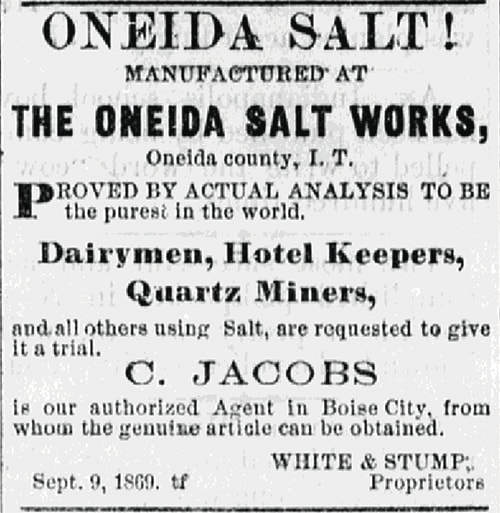

J.H. Stump, who managed the mine, had the creek named after him. B.F. White, his partner, got into politics.

Born in Massachusetts, White had American roots as deep as they go. He was a direct descendent of Peregrine White, the first child born to Pilgrim parents who sailed over on the Mayflower. His political career started out in Malad City, Idaho Territory, where he was elected county clerk and recorder of Oneida County. His career reached its peak in Montana, though.

White, who was a banker and lawyer in addition to his claim to fame as a salt works owner, moved to Montana in 1876, where he established the town of Dillon. He served a couple of terms as mayor and was then elected to the Montana Territorial Legislature in 1882. In 1889 he became the governor of Montana Territory, the last of its territorial governors. Later he would serve as speaker of the Montana House of Representatives and later a Montana State Senator.

Clearly, he was man worth his salt.

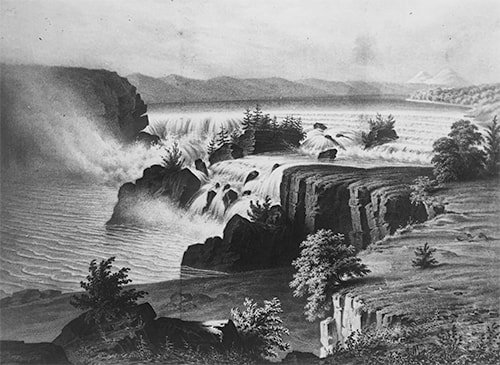

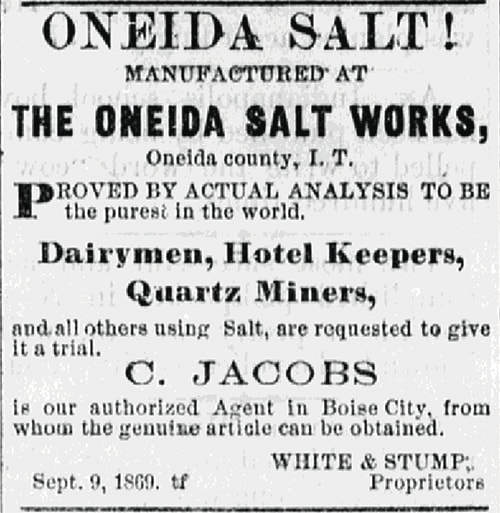

The Oneida Salt Works advertised often in The Idaho Statesman. This ad is from 1870.

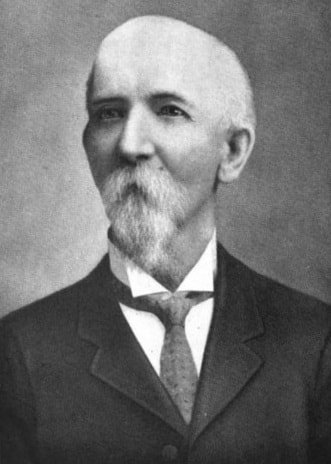

The Oneida Salt Works advertised often in The Idaho Statesman. This ad is from 1870.  Benjamin Franklin White started the Oneida Salt Works with J.H. Stump. He went on to be the last Montana territorial governor.

Benjamin Franklin White started the Oneida Salt Works with J.H. Stump. He went on to be the last Montana territorial governor.

There were a couple of men who set out to mine for what miners needed. They provided one of life’s basic necessities, salt.

Benjamin Franklin White and J.H. Stump began mining salt in Idaho in 1866, at Stump Creek, which is on the Idaho-Wyoming border about 50 miles north of Soda Springs. Stump Creek runs a little salty, about 60 percent. Coaxing the salt out of the water was easily done. All you had to do was let the water evaporate and it would leave salt behind. That was fine if you wanted to fill your shaker, but if you wanted salt in commercial quantities you needed to boil the water away.

That’s what White and Stump did. They built wooden flumes to carry the water into several large galvanized iron pots where the water was boiled away. The salt was shoveled out every 30 minutes. Workers let it drain for about 24 hours then put it in drying houses where it “ripened” for two to four months.

This was no small operation. At the peak of production, the Oneida Salt Works was processing two million pounds a year. Some 300 teams were employed hauling wagonloads of salt, much of it to Montana along the “Salt Road,” also known as the Lander Trail. Each “team” was a triple-wagon setup hitched together and pulled by nine yoke of oxen. The operation lasted some 30 years.

J.H. Stump, who managed the mine, had the creek named after him. B.F. White, his partner, got into politics.

Born in Massachusetts, White had American roots as deep as they go. He was a direct descendent of Peregrine White, the first child born to Pilgrim parents who sailed over on the Mayflower. His political career started out in Malad City, Idaho Territory, where he was elected county clerk and recorder of Oneida County. His career reached its peak in Montana, though.

White, who was a banker and lawyer in addition to his claim to fame as a salt works owner, moved to Montana in 1876, where he established the town of Dillon. He served a couple of terms as mayor and was then elected to the Montana Territorial Legislature in 1882. In 1889 he became the governor of Montana Territory, the last of its territorial governors. Later he would serve as speaker of the Montana House of Representatives and later a Montana State Senator.

Clearly, he was man worth his salt.

The Oneida Salt Works advertised often in The Idaho Statesman. This ad is from 1870.

The Oneida Salt Works advertised often in The Idaho Statesman. This ad is from 1870.  Benjamin Franklin White started the Oneida Salt Works with J.H. Stump. He went on to be the last Montana territorial governor.

Benjamin Franklin White started the Oneida Salt Works with J.H. Stump. He went on to be the last Montana territorial governor.

Published on February 06, 2020 04:00

February 5, 2020

Taking Aim at Farragut

Time for one of our occasional then and now features.

Farragut Naval Training Station (FNTS) on the shores of Lake Pend Oreille, was a key facility in World War II. It went up fast. Construction began in March, 1942. By September of that year, the “boots” were already training.

The barracks, drill halls, and other facilities weren’t designed for long-term use, so few of them exist today. The only major building left on site from the base, the concrete brig, is a museum today at Farragut State Park.

One facility, though, is still in use. It’s not a building. It’s the station’s rifle range.

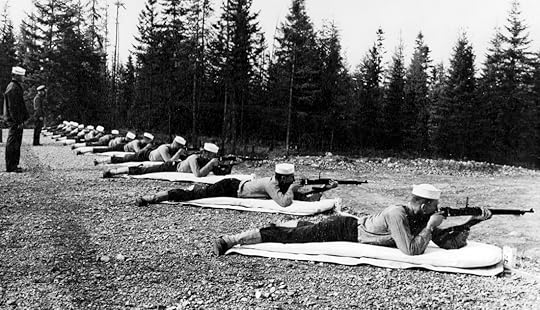

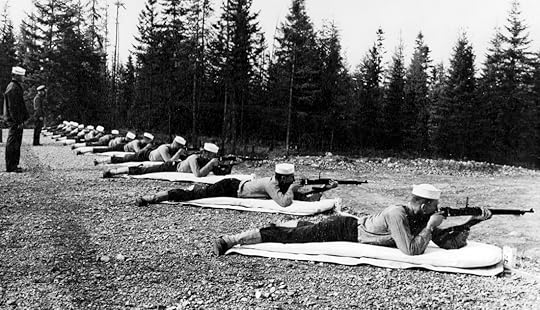

During rifle training, 100 men could fire their rifles at a time on the FNTS range. During the peak of training, about 12,000 rounds of ammunition were fired every day (photo). Both the lead and the brass were salvaged and recycled into new ammunition.

The 50-, 100-, and 200-yard rifle ranges still exist and can be rented for practice and special events. They are operated by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Farragut Naval Training Station (FNTS) on the shores of Lake Pend Oreille, was a key facility in World War II. It went up fast. Construction began in March, 1942. By September of that year, the “boots” were already training.

The barracks, drill halls, and other facilities weren’t designed for long-term use, so few of them exist today. The only major building left on site from the base, the concrete brig, is a museum today at Farragut State Park.

One facility, though, is still in use. It’s not a building. It’s the station’s rifle range.

During rifle training, 100 men could fire their rifles at a time on the FNTS range. During the peak of training, about 12,000 rounds of ammunition were fired every day (photo). Both the lead and the brass were salvaged and recycled into new ammunition.

The 50-, 100-, and 200-yard rifle ranges still exist and can be rented for practice and special events. They are operated by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Published on February 05, 2020 04:00