Rick Just's Blog, page 167

March 25, 2020

Spud

If you live in Idaho, you really should know what a spud is, don’t you think? You may not have personally dug up a potato, but you’ve probably been the beneficiary of someone who has. Nowadays potatoes are usually wrenched from the ground by a mechanical digger and sent up a conveyor chain that bounces most of the dirt away, past some humans who handpick the clods and vines off the chain before the potatoes are tumbled into a truck. It wasn’t always so.

For centuries potatoes were excavated by hand using various implements, one of which was called a spud. It was typically a sharp, narrow-bladed tool something like a trowel. The name probably goes back as far back as the mid-1400s and may have come from the Latin “spad” or sword. Or, it might have come from the Dutch “spyd” which was a short dagger, or the Norse “spjot” which was a spear. Most sources pinpoint its entry into the printed English language to a reference in 1845 in New Zealand.

And now you know what a spud was. Why the word slipped over from the digging implement to the tuber it was digging is lost to history, but it’s not too startling that it did.

According to the website todayifoundout.com some have tried to attach the origin of the word to an acronym. SPUD was an acronym in England for the Society for the Prevention of an Unwholesome Diet, a 19th Century group that had ideas about what one should eat. Potatoes were on the Do Not Eat side of their ledger. It’s unlikely, though, because making words out of acronyms is a 20th Century phenomenon that came into vogue long after the members of SPUD had all been buried, probably with full-sized shovels. Even the word “acronym” wasn’t in use until 1943. We can all thank our lucky stars that it was invented, though, because government could not exist without them.

So “spud” probably wasn’t an acronym, originally. I bet we could do a backformation, though. What should it mean today? Super Potatoes Under Dirt? Society for the Promotion of Underused Dingbats? You tell me.

For centuries potatoes were excavated by hand using various implements, one of which was called a spud. It was typically a sharp, narrow-bladed tool something like a trowel. The name probably goes back as far back as the mid-1400s and may have come from the Latin “spad” or sword. Or, it might have come from the Dutch “spyd” which was a short dagger, or the Norse “spjot” which was a spear. Most sources pinpoint its entry into the printed English language to a reference in 1845 in New Zealand.

And now you know what a spud was. Why the word slipped over from the digging implement to the tuber it was digging is lost to history, but it’s not too startling that it did.

According to the website todayifoundout.com some have tried to attach the origin of the word to an acronym. SPUD was an acronym in England for the Society for the Prevention of an Unwholesome Diet, a 19th Century group that had ideas about what one should eat. Potatoes were on the Do Not Eat side of their ledger. It’s unlikely, though, because making words out of acronyms is a 20th Century phenomenon that came into vogue long after the members of SPUD had all been buried, probably with full-sized shovels. Even the word “acronym” wasn’t in use until 1943. We can all thank our lucky stars that it was invented, though, because government could not exist without them.

So “spud” probably wasn’t an acronym, originally. I bet we could do a backformation, though. What should it mean today? Super Potatoes Under Dirt? Society for the Promotion of Underused Dingbats? You tell me.

Published on March 25, 2020 04:00

March 24, 2020

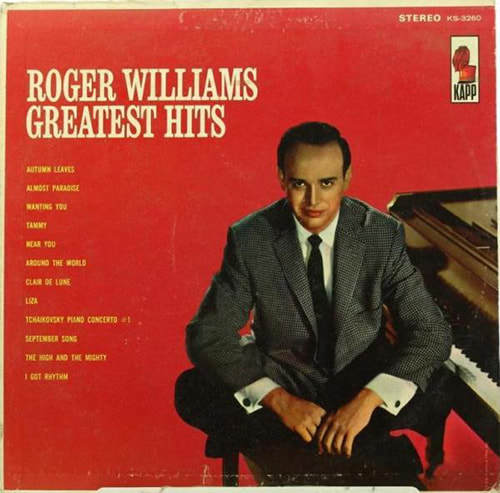

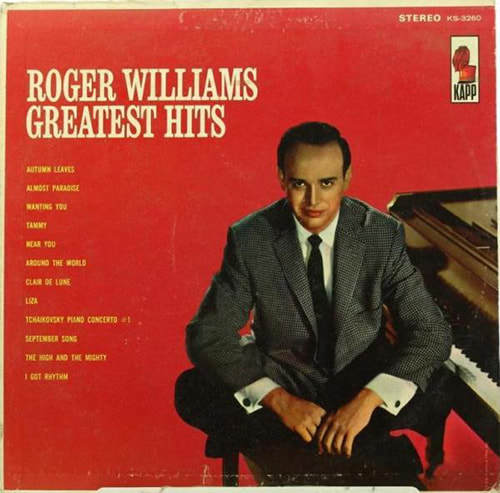

A Famous Pianist's Idaho Connections

Louis Jacob Weertz came to Idaho in 1943. He was one of almost 300,000 men who trained for World War II at Farragut Naval Training Station, where Farragut State Park is now. He played piano well even then, but at Farragut, he was probably best known for his boxing. Weertz was the welterweight champion boxer on the base.

Weertz was one of a handful of Farragut recruits who received part of their training at what was then the University of Idaho Southern Branch in Pocatello. He must have liked the city, because he came back after the war to attend college. He received a BA in music from ISU, then went on to get a Master's from Drake University. He studied further at Julliard in New York.

For whatever reason, Weertz decided to change his name while living in Pocatello. He allegedly pulled out a telephone book and ran his finger down the columns until he found one he liked. That name was Roger Williams.

There was only one Roger Williams in the phonebook at that time, according to the Roger Williams I knew. My friend, Roger, was a long-time Fish and Game employee and gained some measure of fame, along with Syd Tate, by charting out Idaho’s Centennial Trail.

The faux or, perhaps better-said, newly named Roger Williams gained quite a bit of fame in his time.

First, he won "Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts" program, with a lively piano rendition of I Got Rhythm. But it wasn't until 1954, that a record company executive heard him playing piano in a Manhattan cocktail lounge, and signed him to a contract. His first, and still most famous, hit record was Autumn Leaves. By 1968 he had recorded 52 albums, and sold nearly 15 million records. At 43, he became the best-selling instrumentalist of all time.

Roger Williams, name borrower, Farragut Naval Training Station recruit, ISU graduate, and world renowned pianist and composer passed away in 2011.

#rogerwilliams #Farragut #FNTS

Weertz was one of a handful of Farragut recruits who received part of their training at what was then the University of Idaho Southern Branch in Pocatello. He must have liked the city, because he came back after the war to attend college. He received a BA in music from ISU, then went on to get a Master's from Drake University. He studied further at Julliard in New York.

For whatever reason, Weertz decided to change his name while living in Pocatello. He allegedly pulled out a telephone book and ran his finger down the columns until he found one he liked. That name was Roger Williams.

There was only one Roger Williams in the phonebook at that time, according to the Roger Williams I knew. My friend, Roger, was a long-time Fish and Game employee and gained some measure of fame, along with Syd Tate, by charting out Idaho’s Centennial Trail.

The faux or, perhaps better-said, newly named Roger Williams gained quite a bit of fame in his time.

First, he won "Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts" program, with a lively piano rendition of I Got Rhythm. But it wasn't until 1954, that a record company executive heard him playing piano in a Manhattan cocktail lounge, and signed him to a contract. His first, and still most famous, hit record was Autumn Leaves. By 1968 he had recorded 52 albums, and sold nearly 15 million records. At 43, he became the best-selling instrumentalist of all time.

Roger Williams, name borrower, Farragut Naval Training Station recruit, ISU graduate, and world renowned pianist and composer passed away in 2011.

#rogerwilliams #Farragut #FNTS

Published on March 24, 2020 04:00

March 23, 2020

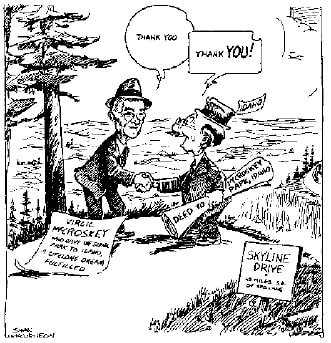

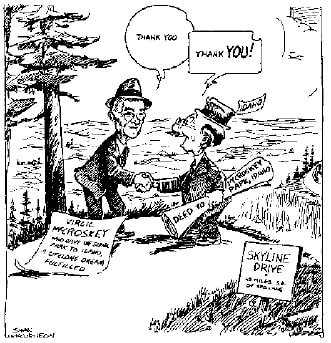

A Persistent Philanthropist

Virgil McCroskey might have been Idaho’s most persistent philanthropist, even though he didn’t live here. Virgil’s parents homesteaded near Steptoe Butte, about eight miles from Colfax, Washington. Virgil played there as a child and grew to love the views of the Palouse from its summit. As an adult his vocation was pharmacist, and his avocation was conservationist. He donated Steptoe Butte to the State of Washington in 1945 to create Steptoe Butte State Park.

He also loved the views of the Palouse just across the border in Idaho from the ridgetops along a winding dirt road called Skyline Drive. He began buying up property there so that he could present Idaho with a state park.

When Virgil McCroskey approached the Idaho Legislature in 1951 about accepting his gift of land, legislators worried about upkeep and about taking 2,000 acres off the property tax rolls. McCroskey purchased more property to add to the gift. By 1954, he had 4,400 acres to offer and a new governor, Robert E. Smylie, as a supporter. Still the legislators were concerned about maintenance, so McCroskey, 79 years old, agreed to maintain it himself for the next 15 years. The lawmakers finally relented, accepting the gift. McCroskey kept his word, taking care of the site until just before his death at age 94 in 1970.

In a sense, he still cares for the park today. McCroskey left $45,000 in trust to the state to be used for maintenance of Mary Minerva McCroskey State Park, which is named for his mother in honor of the pioneer women of the West.

#mccroskeystatepark

He also loved the views of the Palouse just across the border in Idaho from the ridgetops along a winding dirt road called Skyline Drive. He began buying up property there so that he could present Idaho with a state park.

When Virgil McCroskey approached the Idaho Legislature in 1951 about accepting his gift of land, legislators worried about upkeep and about taking 2,000 acres off the property tax rolls. McCroskey purchased more property to add to the gift. By 1954, he had 4,400 acres to offer and a new governor, Robert E. Smylie, as a supporter. Still the legislators were concerned about maintenance, so McCroskey, 79 years old, agreed to maintain it himself for the next 15 years. The lawmakers finally relented, accepting the gift. McCroskey kept his word, taking care of the site until just before his death at age 94 in 1970.

In a sense, he still cares for the park today. McCroskey left $45,000 in trust to the state to be used for maintenance of Mary Minerva McCroskey State Park, which is named for his mother in honor of the pioneer women of the West.

#mccroskeystatepark

Published on March 23, 2020 04:00

March 22, 2020

A Political Family

Today, we’re going to take a quick look at a family that has been a major force in Idaho politics.

We’ll start with John W. Thomas. Thomas is not the best-known US Senator ever to come from the State of Idaho, but he was one of the more persistent people to hold a Senate seat. His first taste of politics was as the mayor of Gooding. From 1925-1933, he was a member of the Republican National Committee. Thomas became a senator the first time in 1928, not by election, but by appointment when Sen. Frank Gooding died in office. He won a special election later that year, and served until 1933. He had lost a reelection bid to Democrat James Pope in 1932.

Thomas became a senator again in 1940, when he was appointed to fill the seat of William Borah, perhaps Idaho’s most famous senator. He was elected to the seat in 1942, but died in office three years later.

The political lineage of the family continues with Thomas’ daughter, Mary. She married Art Peavey of Twin Falls when both were students at the University of Idaho. They had two children, John and Elizabeth (Betty). Mary was widowed when Art Peavey was lost in a boating accident on the Snake River in 1941. She would marry C. Wayland “Curly” Brooks, a US Senator from Illinois in 1946. They were married eleven years until his death from a heart attack in 1957.

Mary Brooks ran her father’s sheep ranch in Idaho from 1945 until 1961, when her son John took over. She served in the Idaho Senate from 1963 until 1969. It was in 1969 that President Nixon tapped Mary Brooks to run the US Mint, a post she held until February 1977. The photo is of Mary Brooks with President Nixon celebrating the release of the Eisenhower dollar.

It is Mary’s son, John Peavey, who is likely most familiar to Idahoans today, if only because he was in politics more recently. Peavey was appointed to fill his mother’s seat when she became Director of the Mint. He served in the Idaho Senate for 23 years, and ran unsuccessfully for lieutenant governor in 1994.

Mary Brooks in a room full of gold at the U.S. Mint.

Mary Brooks in a room full of gold at the U.S. Mint.

We’ll start with John W. Thomas. Thomas is not the best-known US Senator ever to come from the State of Idaho, but he was one of the more persistent people to hold a Senate seat. His first taste of politics was as the mayor of Gooding. From 1925-1933, he was a member of the Republican National Committee. Thomas became a senator the first time in 1928, not by election, but by appointment when Sen. Frank Gooding died in office. He won a special election later that year, and served until 1933. He had lost a reelection bid to Democrat James Pope in 1932.

Thomas became a senator again in 1940, when he was appointed to fill the seat of William Borah, perhaps Idaho’s most famous senator. He was elected to the seat in 1942, but died in office three years later.

The political lineage of the family continues with Thomas’ daughter, Mary. She married Art Peavey of Twin Falls when both were students at the University of Idaho. They had two children, John and Elizabeth (Betty). Mary was widowed when Art Peavey was lost in a boating accident on the Snake River in 1941. She would marry C. Wayland “Curly” Brooks, a US Senator from Illinois in 1946. They were married eleven years until his death from a heart attack in 1957.

Mary Brooks ran her father’s sheep ranch in Idaho from 1945 until 1961, when her son John took over. She served in the Idaho Senate from 1963 until 1969. It was in 1969 that President Nixon tapped Mary Brooks to run the US Mint, a post she held until February 1977. The photo is of Mary Brooks with President Nixon celebrating the release of the Eisenhower dollar.

It is Mary’s son, John Peavey, who is likely most familiar to Idahoans today, if only because he was in politics more recently. Peavey was appointed to fill his mother’s seat when she became Director of the Mint. He served in the Idaho Senate for 23 years, and ran unsuccessfully for lieutenant governor in 1994.

Mary Brooks in a room full of gold at the U.S. Mint.

Mary Brooks in a room full of gold at the U.S. Mint.

Published on March 22, 2020 04:00

March 21, 2020

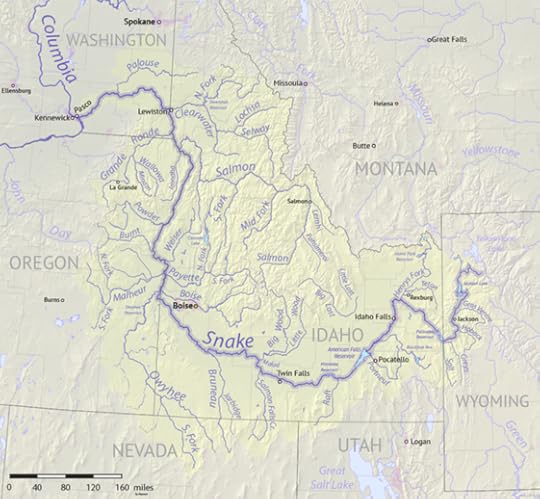

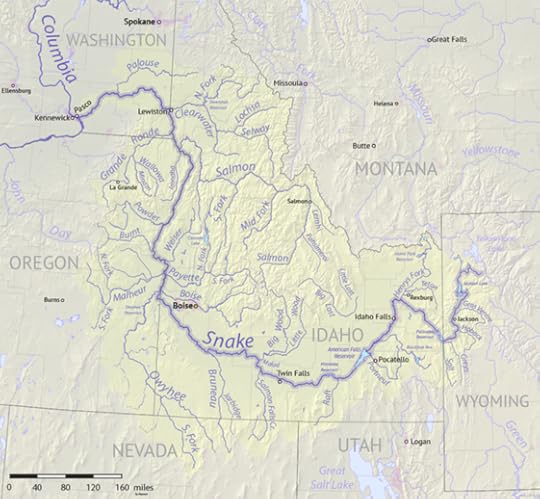

What to Call that River

The Snake River has had a few names. The Shoshone Tribe may have called it Ki-moo-e-nim or Yam-pah-pa after a plant that grew along its shores. In 1800, Canadian explorer David Thompson called it Shawpatin when he arrived at its confluence with the Columbia. In 1805, the Corps of Discovery christened it the Lewis River, after Captain Meriwether Lewis. Wilson Price Hunt called it the Mad River in 1811. Later, claiming one of his party at Cauldron Linn, the name seemed appropriate.

It wasn’t named “Snake” because of any reptile. Historians think it might have been named that because in describing it, Native Americans would make an S-shaped movement with their hands, probably in an attempt to portray its meanders.

By 1905 people had largely settled on calling it the Snake River and it appeared as such on maps. Along came a legislator from Kootenai County, Representative William Ashley, Jr., who wanted to change the name of the river to Shosho-Nee. The proper spelling of the word was a subsection of the debate with some saying it should be spelled Shoshon-e, or Shoshone as it is commonly spelled today.

But why change it at all? Some thought it evoked the shivering thought of snakes. Mercy.

Newspapers all over the state editorialized against the name change. The editor of The Idaho Republican in Blackfoot, where the citizens took up a petition against the name change, wrote “Our uncles in Boston or our aunts in Philadelphia may shudder at the name of Snake or Blackfoot, the college girl may laugh at such names as Bay Horse and Root Hog, and the lady from Maine may not like Buffalo Hump nor the Seven Devils, but she is accustomed to such names as Chemquasabamticook and Piscataquis, and our plain blunt names will do for a while yet.”

The Silver City Nugget opined, “The names that are repulsive will be changed by the people as the state becomes populated, but such names as ‘Snake River’ will never be changed in common use, even should the legislature pass such an act.”

In Parma, the editor of The Herald said, “While ‘Snake’ may not be as euphonious as ‘Shoshonee,’ it is easier to pronounce, and a blamed sight easier to write.”

An Ada County legislator came up with a counter proposal to name—perhaps better said, rename—the stream Lewis River.

In the end the name change was defeated, and we were all left to shudder or shrug at the squirmy image it might provoke.

The Snake River winds through southern Idaho, exiting the state in the north at Lewiston. Does it really remind you of a snake?

The Snake River winds through southern Idaho, exiting the state in the north at Lewiston. Does it really remind you of a snake?

It wasn’t named “Snake” because of any reptile. Historians think it might have been named that because in describing it, Native Americans would make an S-shaped movement with their hands, probably in an attempt to portray its meanders.

By 1905 people had largely settled on calling it the Snake River and it appeared as such on maps. Along came a legislator from Kootenai County, Representative William Ashley, Jr., who wanted to change the name of the river to Shosho-Nee. The proper spelling of the word was a subsection of the debate with some saying it should be spelled Shoshon-e, or Shoshone as it is commonly spelled today.

But why change it at all? Some thought it evoked the shivering thought of snakes. Mercy.

Newspapers all over the state editorialized against the name change. The editor of The Idaho Republican in Blackfoot, where the citizens took up a petition against the name change, wrote “Our uncles in Boston or our aunts in Philadelphia may shudder at the name of Snake or Blackfoot, the college girl may laugh at such names as Bay Horse and Root Hog, and the lady from Maine may not like Buffalo Hump nor the Seven Devils, but she is accustomed to such names as Chemquasabamticook and Piscataquis, and our plain blunt names will do for a while yet.”

The Silver City Nugget opined, “The names that are repulsive will be changed by the people as the state becomes populated, but such names as ‘Snake River’ will never be changed in common use, even should the legislature pass such an act.”

In Parma, the editor of The Herald said, “While ‘Snake’ may not be as euphonious as ‘Shoshonee,’ it is easier to pronounce, and a blamed sight easier to write.”

An Ada County legislator came up with a counter proposal to name—perhaps better said, rename—the stream Lewis River.

In the end the name change was defeated, and we were all left to shudder or shrug at the squirmy image it might provoke.

The Snake River winds through southern Idaho, exiting the state in the north at Lewiston. Does it really remind you of a snake?

The Snake River winds through southern Idaho, exiting the state in the north at Lewiston. Does it really remind you of a snake?

Published on March 21, 2020 04:00

March 20, 2020

Idaho's Deep Throat

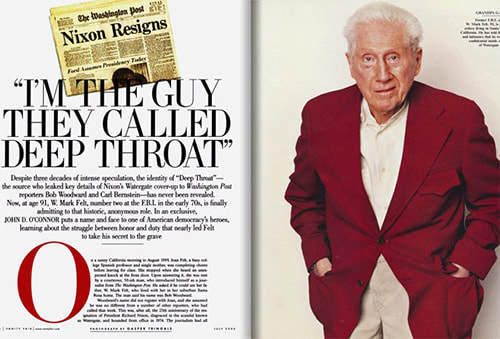

Today we have the story of an Idahoan who was more famous by his code name than his real name.

Mark Felt was born in Twin Falls, Idaho in 1913. He went to Twin Falls High School, and graduated from the University of Idaho in 1935. In 1938 Felt married a girl from Gooding, Audrey Robinson.

Felt went to work for U.S. Senator from Idaho James P. Pope, and later worked for his successor David Worth Clark.

Going to school nights, Felt earned a law degree from George Washington University, graduating in 1940. He started a career with the FBI in 1941, working his way up to the second highest spot in the bureau, associate director in 1972, retiring in 1973.

Oh, and he was “Deep Throat.”

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post , depended heavily on his anonymous tips during the Watergate scandal that brought down President Richard Nixon.

Only a handful of people (including Nixon) knew who “Deep Throat” was, until Vanity Fair magazine revealed the secret on May 31, 2005, when it published an article on its website, followed up by an article in the magazine’s June edition (photo).

Mark Felt passed away December 18, 2008 at the age of 95.

#markfelt #deepthroat

Mark Felt was born in Twin Falls, Idaho in 1913. He went to Twin Falls High School, and graduated from the University of Idaho in 1935. In 1938 Felt married a girl from Gooding, Audrey Robinson.

Felt went to work for U.S. Senator from Idaho James P. Pope, and later worked for his successor David Worth Clark.

Going to school nights, Felt earned a law degree from George Washington University, graduating in 1940. He started a career with the FBI in 1941, working his way up to the second highest spot in the bureau, associate director in 1972, retiring in 1973.

Oh, and he was “Deep Throat.”

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post , depended heavily on his anonymous tips during the Watergate scandal that brought down President Richard Nixon.

Only a handful of people (including Nixon) knew who “Deep Throat” was, until Vanity Fair magazine revealed the secret on May 31, 2005, when it published an article on its website, followed up by an article in the magazine’s June edition (photo).

Mark Felt passed away December 18, 2008 at the age of 95.

#markfelt #deepthroat

Published on March 20, 2020 04:00

March 19, 2020

An Old Era

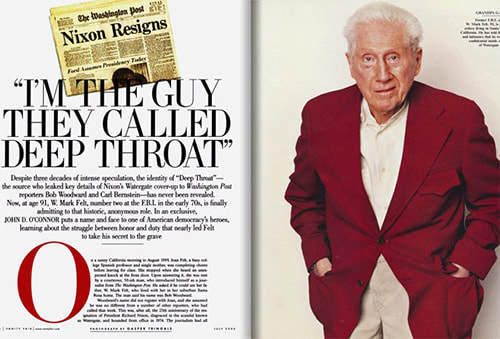

About all that remains of Era, Idaho is the substantial rock foundation of the short-lived crusher mill. Here’s a toast to an old Era. We’re using water from Champagne Creek for this toast, of course, because Champagne Creek was once called Era Creek. And Era was one of Idaho’s many short-lived ghost towns.

About all that remains of Era, Idaho is the substantial rock foundation of the short-lived crusher mill. Here’s a toast to an old Era. We’re using water from Champagne Creek for this toast, of course, because Champagne Creek was once called Era Creek. And Era was one of Idaho’s many short-lived ghost towns.Era was southwest of Mackay, where prospectors discovered what would be called the Silver Horn Mine in 1885. At first, they just freighted the ore in wagons to a smelter in Hailey, but the lode justified its own 20-stamp dry crusher mill. The town quickly grew to 1200 people, serviced by about 15 crucial establishments, not the least of which were saloons. For a couple of years, it was a bustling little burg, then the ore played out. Played out may not be the right term because it all but disappeared as if someone had turned off the silver spigot. The mill ceased operations in 1888. Everybody moved out rather quickly. So did the buildings, most of which were moved to or dismantled and reconstructed in the little town of Arco.

So, that Era, was a short one. It disappeared about as rapidly as the creek that carried its name.

Champagne Creek rises out of the timbered mountains and meanders through a pretty little valley with a steep bench on one side and a lava field on the other, then dives down into the thirsty lava to join other streams in the area, such as Lost River, in a geological sponge known as the Snake River Aquifer.

Era Creek became Champagne Creek after the demise of the town. To my eternal disappointment it is so named not because of its effervescent water, as Champagne Springs near Soda Springs is, but because a rancher named Champagne settled there.

Much of the information about Era, Idaho came from the book Southern Idaho Ghost Towns ,* by Wayne Sparling.

Published on March 19, 2020 04:00

March 18, 2020

Little Jo

Have you ever fantasized about starting a new life? Perhaps no one ever did that more completely than Little Jo Monaghan.

Jo showed up in Ruby City, Idaho Territory in 1867 or 1868 determined to try his hand at mining. He was a slight little guy, no more than five feet tall, but he was a real worker. He dug with the best of them for several weeks, then decided mining was just too tough.

Jo Monaghan then became a sheepherder, spending three years mostly in the company of sheep. After that, he worked in a livery for a time and took to breaking horses for a living. He was so good at it that Andrew Whalen hired him to work in Whalen’s Wild West Show, billing the bronc rider as Cowboy Joe. Whalen offered $25 to anyone who could find a horse the man couldn’t ride.

Eventually Jo homesteaded near Rockville, Idaho. He built a cabin and raised a few livestock, living a quiet life. He served on juries and voted in elections. Jo Monaghan was a respected member of the community. A quiet man. Except that he wasn’t

In 1904 Jo Monaghan passed away. The Weiser Signal marked Jo’s death with the headline, "Sex is Discovered After Death" and noted that, "There are a number of people residing in Weiser, who knew the supposed man intimately, and never had a suspicion that she was not what she represented to be."

Jo Monaghan was a woman. Who that woman was is still open to speculation. One story often told is that she was from a wealthy New York family and had found herself in a family way. As that story goes, she left her child for her sister to raise and headed West. It wasn’t uncommon for women at that time to travel as men to help assure their own safety. Jo may have done that and simply found it convenient to keep up the ruse.

The story has fascinated people for decades. A 1993 movie called The Ballad of Little Joe, written and directed by Maggie Greenwald and starring Suzy Amis as Jo told a version of her life.

The part of the story that always interested me was that he voted. No, make that SHE voted. She might have been one of the first women to cast a vote in the United States.

#littlejoemonaghn #littlejomonaghn

Jo showed up in Ruby City, Idaho Territory in 1867 or 1868 determined to try his hand at mining. He was a slight little guy, no more than five feet tall, but he was a real worker. He dug with the best of them for several weeks, then decided mining was just too tough.

Jo Monaghan then became a sheepherder, spending three years mostly in the company of sheep. After that, he worked in a livery for a time and took to breaking horses for a living. He was so good at it that Andrew Whalen hired him to work in Whalen’s Wild West Show, billing the bronc rider as Cowboy Joe. Whalen offered $25 to anyone who could find a horse the man couldn’t ride.

Eventually Jo homesteaded near Rockville, Idaho. He built a cabin and raised a few livestock, living a quiet life. He served on juries and voted in elections. Jo Monaghan was a respected member of the community. A quiet man. Except that he wasn’t

In 1904 Jo Monaghan passed away. The Weiser Signal marked Jo’s death with the headline, "Sex is Discovered After Death" and noted that, "There are a number of people residing in Weiser, who knew the supposed man intimately, and never had a suspicion that she was not what she represented to be."

Jo Monaghan was a woman. Who that woman was is still open to speculation. One story often told is that she was from a wealthy New York family and had found herself in a family way. As that story goes, she left her child for her sister to raise and headed West. It wasn’t uncommon for women at that time to travel as men to help assure their own safety. Jo may have done that and simply found it convenient to keep up the ruse.

The story has fascinated people for decades. A 1993 movie called The Ballad of Little Joe, written and directed by Maggie Greenwald and starring Suzy Amis as Jo told a version of her life.

The part of the story that always interested me was that he voted. No, make that SHE voted. She might have been one of the first women to cast a vote in the United States.

#littlejoemonaghn #littlejomonaghn

Published on March 18, 2020 04:00

March 17, 2020

Train Wreckers

In the early days of railroads there was a subset of law breakers called Train Wreckers. They were sometimes involved in union activities, trying to derail a train as part of a labor action, but most often robbery was the motive. The activity inspired hundreds of headlines and at least one stage production.

The three most popular methods of wrecking a train were, first, to take out a trestle, which would send a locomotive plunging. Second, was the removal of frogs, the structure that ties two rail ends together. This could be accompanied by the shifting of at least one of the rails. Third, vandals would put some obstruction on the track, ranging from logs to boulders. Derailing the train was often the result, but simply stopping it would do nearly as well.

In 1890 newspaper readers in the Treasure Valley followed the story of an attempt to wreck the Montreal Express near Albany New York. In 1891, wreckers were foiled when someone found a piece of iron fastened to tracks near Minneapolis. The plotters were caught and confessed they were planning to rob the disabled train.

In September 1892, Passenger Train Number 8 was derailed west of Osage, Missouri. Four men were killed in the attempted robbery of a million dollars on board the train. Thirty-five men, women and children were injured. That same year a train wreck was foiled in Coon Rapids, Iowa. There were alleged Mafia ties to that one.

In 1893, train wreckers bumped the Vandela Express from its tracks near Brazil, Indiana. In February 1894 a train was derailed near Houston, and the wreck robbed in a hail of bullets. That same year there were train wreckers in Colorado and California. And Idaho.

Some lament that Idaho is late to every party, but this wasn’t one to which anyone sought an invitation. It came by way of rail.

On a September day in 1894 a westbound train chugged out of Mountain Home across the desert toward Nampa. The train carried passengers, mail, and freight. Things were progressing routinely until the engineer squinted into the distance. There was something on the track. That something was moving toward them. It was a handcar with two men aboard pumping furiously into the teeth of the barreling locomotive. The engineer pulled hard on the brake lever, raising a hideous shriek from steel wheels sliding on steel rails.

The sudden action threw passengers from their seats. When the train came to a stop the travelers piled out of the cars to see what was up.

Aboard the handcar, now snugged up to the cowcatcher, was the railroad section foreman and a section hand, out of breath from pumping.

In words you are welcome to color with your imagination the engineer inquired as to the purpose of putting a handcar in the path of a speeding train. In fact, the section foreman had an excellent answer. He had been on a routine inspection of the tracks in his section near Owyhee Station when he noticed that someone had removed the frogs and fish plates to misalign a track section that ran across a gully. The next train to hit that trestle would have plunged 45 feet into the channel with cars piling behind it like loose dominos.

The railroad men had worked feverishly to repair the track before the scheduled train could hit the bad spot. Repaired though it was, the men thought it would be prudent to warn the coming train to take it slow and careful, and not just out of an abundance of caution about the repair. While working to fix the vandalized section the railroad men had spotted a man on horseback, well-armed, watching their progress from a nearby hilltop.

Fearing there might be more mischief ahead, the train crew prepared the passengers for a possible attack, having them crouch low on the floor. It was about then that the aforementioned horseman appeared as a silhouette on a ridgetop. As it happened, the assistant superintendent of the Oregon Short Line—so named because it was the shortest route between Wyoming and Oregon—was on board. S.S. Morris walked out to have a chat with the rider. The man declined the invitation by spurring his horse and disappearing behind the rise.

The slow, careful chug into Nampa with eyeballs examining the rails along the way, was accompanied at one point by the mystery rider. He galloped alongside the train, showing off his rifle in an aggressive way, but never firing a shot. It must have been an act of frustration.

The train rolled away, but the rider pulled up and turned his horse back toward Owyhee station where he found the section foreman and his section hand moving the handcar to a siding. The mystery rider began sending bullets in their direction. The rail men, no fools they, took cover. The bullets left a mark on the handcar, but the men were unharmed. The would-be robber finally rode off.

As soon as the train rolled into Nampa law enforcement got involved. Since the potential robbery of a mail car was involved, that brought in the U.S. Marshall. A renowned Indian fighter named Orlando “Rube” Robbins was dispatched to bring the perpetrator(s) to justice. Rube and his posse set out into Owyhee County with the best wishes and high hopes of the gentle people of the region. The Statesman opined, “(U.S.) Marshal Crutcher is fortunate in having been able to lay hands at once on Rube Robbins and start him on the trail. Robbins is like a bloodhound when tracking a criminal, and the fact that his game would have only a few hours start makes speedy capture exceedingly probable.”

Rube and his crew did find some promising tracks to follow, just as a thunderstorm sluiced them away. In talking with locals they uncovered a precious lead, which The Statesman duly reported. In stacked headlines, common at the time, the paper blared:

NOTORIOUS BANDIT HERE

Thought to Be the Leader of the

Train Wreckers

OLD HAND AT THE BUSINESS

Charles Somers, a Famous Outlaw.

Known to Have Been in This

Vicinity Recently.

Somers was the prime suspect because, “(he) is an outlaw who has been concerned in several train robberies.” He had been arrested by Pinkerton agents a year and a half earlier for robbing a train in California, tried, and sentenced to prison. Then he escaped.

It was reported that Somers had an aunt living in Boise, whom he had recently visited. He had boasted to someone that he had eaten at the Palace restaurant at the table right next to the chief of police!

Excitement about the train wrecker or wreckers and imminent capture of same soon dwindled as the posse came back without a prisoner in tow.

Somers, the main suspect, took some air out of the balloon when he wrote to The Statesman from Toronto, Canada. “I see I am charged with being the leader of bandits who recently attempted to wreck a train near Boise,” he wrote. “And also, with being an old hand at the business. Parties who perpetrated the recent crime deserve no consideration from the pursuing posse and would get none from me if I were a member of it.”

The accused went on to say, “If it will satisfy the curiosity of your readers to know the truth of the report that I ate supper at the same table in the Spanish restaurant in Boise with the chief of police let me end the suspense by saying yes. Such was the case, but is was April, not recently as claimed. I think I could go there and do so again with impunity. As to being a desperate man, I will say I am as docile as a kitten, but confess such charges in your article are enough to drive a man to desperation.”

Somers asked but one thing of The Statesman. Could they at least spell his name right? It was Summers, not Somers.

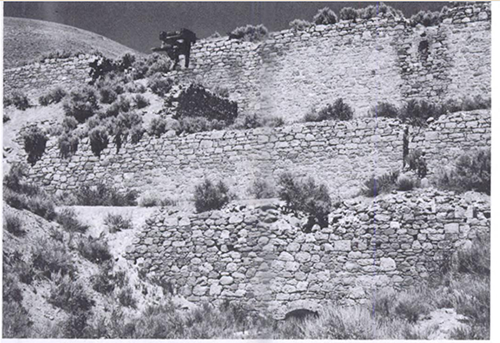

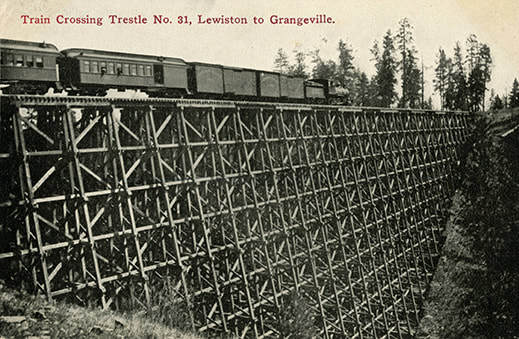

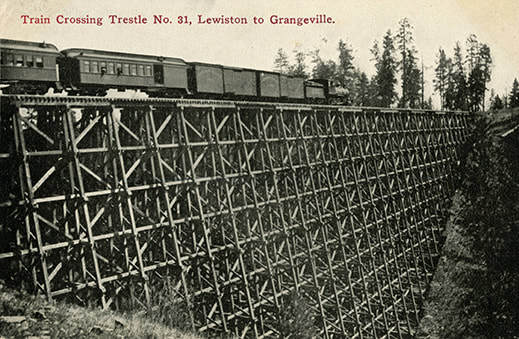

So, with little more gained from the whole incident than a spelling correction the story of the very nearly almost train wreck and robbery of 1894 faded away like a desert flower past its prime. This wasn't the train in the story, but it will help you imagine the kind of damage a train wrecker could cause.

This wasn't the train in the story, but it will help you imagine the kind of damage a train wrecker could cause.

The three most popular methods of wrecking a train were, first, to take out a trestle, which would send a locomotive plunging. Second, was the removal of frogs, the structure that ties two rail ends together. This could be accompanied by the shifting of at least one of the rails. Third, vandals would put some obstruction on the track, ranging from logs to boulders. Derailing the train was often the result, but simply stopping it would do nearly as well.

In 1890 newspaper readers in the Treasure Valley followed the story of an attempt to wreck the Montreal Express near Albany New York. In 1891, wreckers were foiled when someone found a piece of iron fastened to tracks near Minneapolis. The plotters were caught and confessed they were planning to rob the disabled train.

In September 1892, Passenger Train Number 8 was derailed west of Osage, Missouri. Four men were killed in the attempted robbery of a million dollars on board the train. Thirty-five men, women and children were injured. That same year a train wreck was foiled in Coon Rapids, Iowa. There were alleged Mafia ties to that one.

In 1893, train wreckers bumped the Vandela Express from its tracks near Brazil, Indiana. In February 1894 a train was derailed near Houston, and the wreck robbed in a hail of bullets. That same year there were train wreckers in Colorado and California. And Idaho.

Some lament that Idaho is late to every party, but this wasn’t one to which anyone sought an invitation. It came by way of rail.

On a September day in 1894 a westbound train chugged out of Mountain Home across the desert toward Nampa. The train carried passengers, mail, and freight. Things were progressing routinely until the engineer squinted into the distance. There was something on the track. That something was moving toward them. It was a handcar with two men aboard pumping furiously into the teeth of the barreling locomotive. The engineer pulled hard on the brake lever, raising a hideous shriek from steel wheels sliding on steel rails.

The sudden action threw passengers from their seats. When the train came to a stop the travelers piled out of the cars to see what was up.

Aboard the handcar, now snugged up to the cowcatcher, was the railroad section foreman and a section hand, out of breath from pumping.

In words you are welcome to color with your imagination the engineer inquired as to the purpose of putting a handcar in the path of a speeding train. In fact, the section foreman had an excellent answer. He had been on a routine inspection of the tracks in his section near Owyhee Station when he noticed that someone had removed the frogs and fish plates to misalign a track section that ran across a gully. The next train to hit that trestle would have plunged 45 feet into the channel with cars piling behind it like loose dominos.

The railroad men had worked feverishly to repair the track before the scheduled train could hit the bad spot. Repaired though it was, the men thought it would be prudent to warn the coming train to take it slow and careful, and not just out of an abundance of caution about the repair. While working to fix the vandalized section the railroad men had spotted a man on horseback, well-armed, watching their progress from a nearby hilltop.

Fearing there might be more mischief ahead, the train crew prepared the passengers for a possible attack, having them crouch low on the floor. It was about then that the aforementioned horseman appeared as a silhouette on a ridgetop. As it happened, the assistant superintendent of the Oregon Short Line—so named because it was the shortest route between Wyoming and Oregon—was on board. S.S. Morris walked out to have a chat with the rider. The man declined the invitation by spurring his horse and disappearing behind the rise.

The slow, careful chug into Nampa with eyeballs examining the rails along the way, was accompanied at one point by the mystery rider. He galloped alongside the train, showing off his rifle in an aggressive way, but never firing a shot. It must have been an act of frustration.

The train rolled away, but the rider pulled up and turned his horse back toward Owyhee station where he found the section foreman and his section hand moving the handcar to a siding. The mystery rider began sending bullets in their direction. The rail men, no fools they, took cover. The bullets left a mark on the handcar, but the men were unharmed. The would-be robber finally rode off.

As soon as the train rolled into Nampa law enforcement got involved. Since the potential robbery of a mail car was involved, that brought in the U.S. Marshall. A renowned Indian fighter named Orlando “Rube” Robbins was dispatched to bring the perpetrator(s) to justice. Rube and his posse set out into Owyhee County with the best wishes and high hopes of the gentle people of the region. The Statesman opined, “(U.S.) Marshal Crutcher is fortunate in having been able to lay hands at once on Rube Robbins and start him on the trail. Robbins is like a bloodhound when tracking a criminal, and the fact that his game would have only a few hours start makes speedy capture exceedingly probable.”

Rube and his crew did find some promising tracks to follow, just as a thunderstorm sluiced them away. In talking with locals they uncovered a precious lead, which The Statesman duly reported. In stacked headlines, common at the time, the paper blared:

NOTORIOUS BANDIT HERE

Thought to Be the Leader of the

Train Wreckers

OLD HAND AT THE BUSINESS

Charles Somers, a Famous Outlaw.

Known to Have Been in This

Vicinity Recently.

Somers was the prime suspect because, “(he) is an outlaw who has been concerned in several train robberies.” He had been arrested by Pinkerton agents a year and a half earlier for robbing a train in California, tried, and sentenced to prison. Then he escaped.

It was reported that Somers had an aunt living in Boise, whom he had recently visited. He had boasted to someone that he had eaten at the Palace restaurant at the table right next to the chief of police!

Excitement about the train wrecker or wreckers and imminent capture of same soon dwindled as the posse came back without a prisoner in tow.

Somers, the main suspect, took some air out of the balloon when he wrote to The Statesman from Toronto, Canada. “I see I am charged with being the leader of bandits who recently attempted to wreck a train near Boise,” he wrote. “And also, with being an old hand at the business. Parties who perpetrated the recent crime deserve no consideration from the pursuing posse and would get none from me if I were a member of it.”

The accused went on to say, “If it will satisfy the curiosity of your readers to know the truth of the report that I ate supper at the same table in the Spanish restaurant in Boise with the chief of police let me end the suspense by saying yes. Such was the case, but is was April, not recently as claimed. I think I could go there and do so again with impunity. As to being a desperate man, I will say I am as docile as a kitten, but confess such charges in your article are enough to drive a man to desperation.”

Somers asked but one thing of The Statesman. Could they at least spell his name right? It was Summers, not Somers.

So, with little more gained from the whole incident than a spelling correction the story of the very nearly almost train wreck and robbery of 1894 faded away like a desert flower past its prime.

This wasn't the train in the story, but it will help you imagine the kind of damage a train wrecker could cause.

This wasn't the train in the story, but it will help you imagine the kind of damage a train wrecker could cause.

Published on March 17, 2020 04:00

March 16, 2020

Kulleyspell House

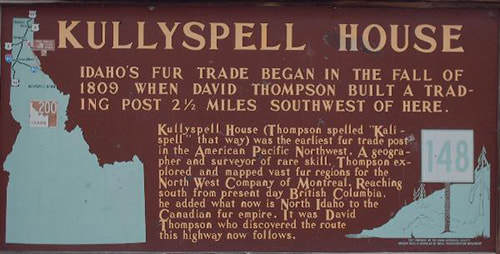

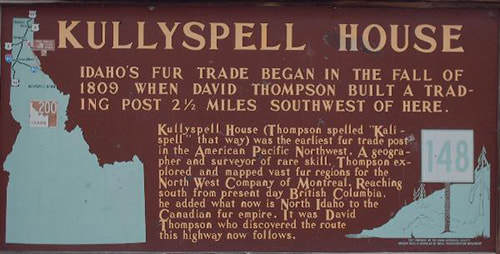

In 1809 explorer David Thompson, who worked for the North West Company, directed the construction of the first white establishment in what later became Idaho.

The trading post, called Kullyspell House, was located near present day Hope, about 16 miles from Sandpoint. The historical marker is on Idaho 200 at about mile marker 48.

It was made of split logs and had two big stone chimneys. It was the chimneys that lasted the longest. For 87 years they stood like tombstones against the elements before finally toppling in a big windstorm. With the chimneys fallen, Kullyspell House all but vanished.

In time, even the locals forgot its exact location.

Then in 1928 a group of Idaho pioneers and historians set out to settle the question of just where Kullyspell House had been located. Ironically, they used a blind man as their guide. An aged Indian named Kali Too remembered seeing the chimneys as a child. Even though Kali Too had been blind for many years he remembered the landscape clearly. He told the group to go to a certain point along the shore of Lake Pend Oreille. From there, he told them to look for a big rock that was shaped like a bear's paw. Sure enough, when they got to the site there was a rock that looked like a bear's paw. From there the old Indian directed the party inland. In just a few minutes a cheer went up. They had found a pile of rocks that might once have been the missing chimneys. Later archaeological research proved it. Kullyspell House--or what was left of it--had been found. You might call it blind luck.

#davidthompson #kullyspellhouse

The trading post, called Kullyspell House, was located near present day Hope, about 16 miles from Sandpoint. The historical marker is on Idaho 200 at about mile marker 48.

It was made of split logs and had two big stone chimneys. It was the chimneys that lasted the longest. For 87 years they stood like tombstones against the elements before finally toppling in a big windstorm. With the chimneys fallen, Kullyspell House all but vanished.

In time, even the locals forgot its exact location.

Then in 1928 a group of Idaho pioneers and historians set out to settle the question of just where Kullyspell House had been located. Ironically, they used a blind man as their guide. An aged Indian named Kali Too remembered seeing the chimneys as a child. Even though Kali Too had been blind for many years he remembered the landscape clearly. He told the group to go to a certain point along the shore of Lake Pend Oreille. From there, he told them to look for a big rock that was shaped like a bear's paw. Sure enough, when they got to the site there was a rock that looked like a bear's paw. From there the old Indian directed the party inland. In just a few minutes a cheer went up. They had found a pile of rocks that might once have been the missing chimneys. Later archaeological research proved it. Kullyspell House--or what was left of it--had been found. You might call it blind luck.

#davidthompson #kullyspellhouse

Published on March 16, 2020 04:00