Rick Just's Blog, page 170

February 24, 2020

When Coal Was King

Coal is not a popular mineral in these days of climate change. But states where an abundance of it was found gained some prosperity for many years. Not Idaho, of course. No coal in Idaho. Or, as the Idaho Museum of Natural History states on their website, “Almost every important mineral except oil, gas and coal can be found in Idaho.”

Some would beg to differ. “A few thin beds” of coal have been found north of Horseshoe Bend and in the surrounding area. Also, geologists have found some coal near the Utah border in Cassia County. None of that amounts to much. But, how does 11 million tons sound? That’s the estimated amount of coal in several seams in the Horseshoe Basin near Driggs.

A small mine operated there beginning in 1905, but it was 1921 when things really got going with the development of a branch railroad to the Brown Bear seam where the Gem State Coal Company began working on a tunnel. By the following year the tunnel went 650 feet into the seam and coal had been shipped to nearby communities in Montana and Idaho. They mined into the 1930s, but a declining market for coal killed the operation. Most of that 11 million tons is still in the ground where, with the cost of other energy sources undercutting it, the coal will likely remain.

On a personal note, in 1924 my father-in-law was born in Sam, Idaho (long since abandoned) where his father was working for the Gem State Coal company.

An interesting, if racist, ad from a 1910 Idaho Statesman.

An interesting, if racist, ad from a 1910 Idaho Statesman.

Some would beg to differ. “A few thin beds” of coal have been found north of Horseshoe Bend and in the surrounding area. Also, geologists have found some coal near the Utah border in Cassia County. None of that amounts to much. But, how does 11 million tons sound? That’s the estimated amount of coal in several seams in the Horseshoe Basin near Driggs.

A small mine operated there beginning in 1905, but it was 1921 when things really got going with the development of a branch railroad to the Brown Bear seam where the Gem State Coal Company began working on a tunnel. By the following year the tunnel went 650 feet into the seam and coal had been shipped to nearby communities in Montana and Idaho. They mined into the 1930s, but a declining market for coal killed the operation. Most of that 11 million tons is still in the ground where, with the cost of other energy sources undercutting it, the coal will likely remain.

On a personal note, in 1924 my father-in-law was born in Sam, Idaho (long since abandoned) where his father was working for the Gem State Coal company.

An interesting, if racist, ad from a 1910 Idaho Statesman.

An interesting, if racist, ad from a 1910 Idaho Statesman.

Published on February 24, 2020 04:00

February 23, 2020

The Lapwai Press

Idaho became a state in 1890, as probably everyone reading this knows. It was 1959 before Hawaii became a state, yet it was to Hawaii that Reverend Henry Harmon Spalding turned to obtain a major machine of civilization. In 1838 Spalding wrote to the Congregational mission in Honolulu, “requesting the donation of a second-hand press and that the Sandwich Islands Mission should instruct someone, to be sent there from Oregon, in the art of printing, and in the meantime print a few small books in Nez Perces.”

The Sandwich Islands would later become the Hawaiian Islands, and the Oregon Spalding referred to what was then Oregon Territory, where his own Lapwai Mission stood. It would not become Idaho Territory until 1863, long after the Spaldings had fled the territory.

According to the book, The Lapwai Mission Press, by Wilfred P. Schoenberg, S.J., from which the quotes in this post are also taken, no book of Nez Perce was printed in Hawaii, though a proof consisting of a couple of pages of set type for a Nez Perce spelling book created by Spalding and his wife Eliza was printed. Instead, the Sandwich Island Mission prepared to fulfill Spalding’s main request, which was for a printing press to be sent to Lapwai.

The press they would send, was the fifth press in Hawaii. It would be the first in the Pacific Northwest, the eighth in what would become the West of the United States. Importantly, it is the only one of those first eight still in existence.

The Sandwich Island Mission sent not just the press, but the pressman. Edwin Oscar Hall, a lay minister in the congregation, would accompany the press to Lapwai. He agreed to do so partly because his wife’s health would benefit from a cooler climate.

Hall set up the press and began working it on May 16, 1839, three days after they arrived at Lapwai. He set about running proof sheets, and by May 24 he had printed four hundred copies of an 8-page book using an artificial alphabet of the Nez Perce Spalding had devised. This “reader for beginners and children” was the first book printed in Oregon Territory. If you had a copy of that thin to me it would be worth quite a lot today. But you don’t, because shortly after the little books were printed they were destroyed.

In July, 1839, all the missionaries of Oregon Territory got together to discuss the book. They found Spalding’s attempt to create a Nez Perce alphabet and provide a means for translating the language could not “be relied on for books, or as a standard in any sense.”

The Reverend Asa Bowen Smith edited a new version of Spalding’s book, which would be called First Book: Designed For Children And New Beginners.” It was published in August, 1839.

The book the missionaries rejected and ordered destroyed, lived on in a way. In later years it was discovered that some pages of that earliest printing were used in the cover and binding of the new “first book.”

The printer Hall and his wife returned to the Sandwich Islands in May of 1840, leaving the press behind.

In 1842 or 43 the press was used to print a book for young readers in the Spokane language, a book of The Laws and Statutes, and a hymn book. Spalding labored for two years on a Nez Perce translation of the gospel of St. Matthew. It was printed in 1845. That year the last of the imprints from the Lapwai press appeared, a “vocabulary” of Nez Perce and English words. In 1846 the press was moved to The Dalles. It had a short history printing The Oregon and American Evangelical Unionist, and, years later, in 1875, was donated to the Oregon State Historical Society in Salem, where it resides today. The Lapwai press, courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

The Lapwai press, courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

The Sandwich Islands would later become the Hawaiian Islands, and the Oregon Spalding referred to what was then Oregon Territory, where his own Lapwai Mission stood. It would not become Idaho Territory until 1863, long after the Spaldings had fled the territory.

According to the book, The Lapwai Mission Press, by Wilfred P. Schoenberg, S.J., from which the quotes in this post are also taken, no book of Nez Perce was printed in Hawaii, though a proof consisting of a couple of pages of set type for a Nez Perce spelling book created by Spalding and his wife Eliza was printed. Instead, the Sandwich Island Mission prepared to fulfill Spalding’s main request, which was for a printing press to be sent to Lapwai.

The press they would send, was the fifth press in Hawaii. It would be the first in the Pacific Northwest, the eighth in what would become the West of the United States. Importantly, it is the only one of those first eight still in existence.

The Sandwich Island Mission sent not just the press, but the pressman. Edwin Oscar Hall, a lay minister in the congregation, would accompany the press to Lapwai. He agreed to do so partly because his wife’s health would benefit from a cooler climate.

Hall set up the press and began working it on May 16, 1839, three days after they arrived at Lapwai. He set about running proof sheets, and by May 24 he had printed four hundred copies of an 8-page book using an artificial alphabet of the Nez Perce Spalding had devised. This “reader for beginners and children” was the first book printed in Oregon Territory. If you had a copy of that thin to me it would be worth quite a lot today. But you don’t, because shortly after the little books were printed they were destroyed.

In July, 1839, all the missionaries of Oregon Territory got together to discuss the book. They found Spalding’s attempt to create a Nez Perce alphabet and provide a means for translating the language could not “be relied on for books, or as a standard in any sense.”

The Reverend Asa Bowen Smith edited a new version of Spalding’s book, which would be called First Book: Designed For Children And New Beginners.” It was published in August, 1839.

The book the missionaries rejected and ordered destroyed, lived on in a way. In later years it was discovered that some pages of that earliest printing were used in the cover and binding of the new “first book.”

The printer Hall and his wife returned to the Sandwich Islands in May of 1840, leaving the press behind.

In 1842 or 43 the press was used to print a book for young readers in the Spokane language, a book of The Laws and Statutes, and a hymn book. Spalding labored for two years on a Nez Perce translation of the gospel of St. Matthew. It was printed in 1845. That year the last of the imprints from the Lapwai press appeared, a “vocabulary” of Nez Perce and English words. In 1846 the press was moved to The Dalles. It had a short history printing The Oregon and American Evangelical Unionist, and, years later, in 1875, was donated to the Oregon State Historical Society in Salem, where it resides today.

The Lapwai press, courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

The Lapwai press, courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

Published on February 23, 2020 04:00

February 22, 2020

The Shelley Farm Camp

Most of us know something about Japanese internment camps. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor hysteria ran high, pressuring President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. It forced the removal and incarceration of more than 120,000 U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry (Nikkei) in ten prison camps across the West, based mostly on their ethnicity. Some 13,000 ended up at what is sometimes called the Hunt Camp at Minidoka, Idaho.

Less well known is a program that brought many of those incarcerated Americans to work in the beet fields of Bingham County.

Sugar is a staple product at any time. During World War II it was a staple that was in short supply. We think of sugar as a basic baking ingredient and something to put on our cereal. But in wartime it takes on new importance. It can be converted to industrial alcohol to be used in the making of synthetic rubber and munitions. It was so important to the latter, that the United States Beet Sugar Association stated that a fifth of an acre of sugar beets went up in smoke every time a sixteen-inch gun was fired.

The federal government encouraged farmers to plant more sugar beets, since the supply of cane sugar imported from the Philippines was cut off during the war. But planting beets isn’t enough. Farmers needed workers to cultivate and harvest their crops. Many men who might have once hoed the rows were now working in defense industries or fighting in the war.

Volunteers stepped up to thin beets. Business owners closed shops early, members of various clubs stepped up, and Idaho Fish and Game employees spent some time in the fields. A newspaper editor, a college president, and countless clerks volunteered. But more help was needed.

The Japanese internment camps became a source of labor for the wartime sugar harvests. Laborers and their families moved into the beet fields in nine western states. The Farm Labor Camp in Shelley was the center of the activity in Bingham County.

The program lasted about three years, employing several hundred workers in Bingham County from the internment camp at Minidoka. A young boy made a pet of a mourning dove at the Shelley Farm Camp. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

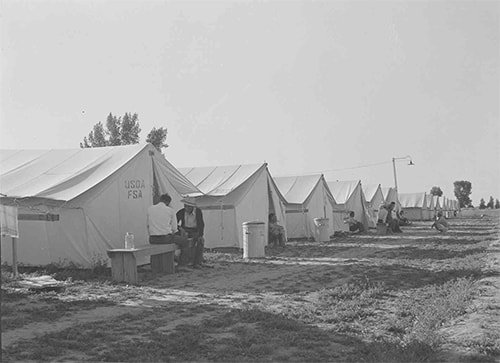

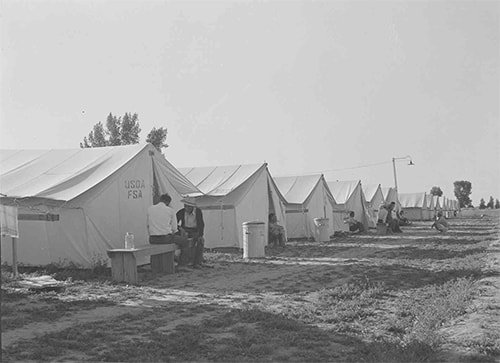

A young boy made a pet of a mourning dove at the Shelley Farm Camp. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.  Internees from the Minidoka Camp were housed temporarily in tents at the Shelley Farm Camp so that they could help with the sugar beet crop in the county. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Internees from the Minidoka Camp were housed temporarily in tents at the Shelley Farm Camp so that they could help with the sugar beet crop in the county. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Less well known is a program that brought many of those incarcerated Americans to work in the beet fields of Bingham County.

Sugar is a staple product at any time. During World War II it was a staple that was in short supply. We think of sugar as a basic baking ingredient and something to put on our cereal. But in wartime it takes on new importance. It can be converted to industrial alcohol to be used in the making of synthetic rubber and munitions. It was so important to the latter, that the United States Beet Sugar Association stated that a fifth of an acre of sugar beets went up in smoke every time a sixteen-inch gun was fired.

The federal government encouraged farmers to plant more sugar beets, since the supply of cane sugar imported from the Philippines was cut off during the war. But planting beets isn’t enough. Farmers needed workers to cultivate and harvest their crops. Many men who might have once hoed the rows were now working in defense industries or fighting in the war.

Volunteers stepped up to thin beets. Business owners closed shops early, members of various clubs stepped up, and Idaho Fish and Game employees spent some time in the fields. A newspaper editor, a college president, and countless clerks volunteered. But more help was needed.

The Japanese internment camps became a source of labor for the wartime sugar harvests. Laborers and their families moved into the beet fields in nine western states. The Farm Labor Camp in Shelley was the center of the activity in Bingham County.

The program lasted about three years, employing several hundred workers in Bingham County from the internment camp at Minidoka.

A young boy made a pet of a mourning dove at the Shelley Farm Camp. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A young boy made a pet of a mourning dove at the Shelley Farm Camp. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.  Internees from the Minidoka Camp were housed temporarily in tents at the Shelley Farm Camp so that they could help with the sugar beet crop in the county. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Internees from the Minidoka Camp were housed temporarily in tents at the Shelley Farm Camp so that they could help with the sugar beet crop in the county. Photo taken by Lee Russell of the Farm Services Administration, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Published on February 22, 2020 04:00

February 21, 2020

Hornikabrinka

Ah, what can one say about Hornikabrinka? Apparently, almost nothing. If you search for the word in The Idaho Statesman digital archives, you get several hits that talk about the 1913 revival of Hornikabrinka, which was to be held in conjunction with the semicentennial of the State of Idaho and the creation of Fort Boise that September. They were looking for “old-timers” who might be convinced to “reenact the stunts they used to do during the old time affairs.” What those stunts were is anyone’s guess.

There was little spate of interest in Hornikabrinka in 1968 when a reader asked the Action Post columnist at the Statesman about it. They provided an answer that, though sketchy, set me on the right track. The columnist spelled it Hornikibrinki. The spelling of the event also included Horniki Brinki and Hornika Brinka in some references.

Speculation about exactly what it was, what it meant, and how it started seemed to be part of the fun. A headline from the August 1913 Idaho Statesman read “Hornika Brinika—What’s His Batting Average?” The reporter had walked around town asking people what the word or words meant to them. “Is it a drink, a germ, or a disease?”

During the 1913 celebration, it was billed as a revival of the tradition from around the founding of Boise. George Washington Stilts, a well-known practical joker in town during those earliest days, seemed to be one of the ringleaders of those celebrations. Which were exactly what?

Think Mardis Gras.

The September 27 Idaho Statesman had a full page about the festivities, headlined, “FROLIC OF THE FUNMAKERS—Mask Parade and Street Dance a Wild Revel of Pleasure.” The article began, “Herniki Briniki—symbol for expression of a wild, care free, abandoned, and yet not unduly boisterous variety of mirth that only that phrase will describe…” It continued “Fully 500 maskers took part in the parade, and such costumes! From the beautiful to the ridiculous, with the emphasis on the latter, they ranged, in a kaleidoscopic and seemingly endless variety.”

Then, showing the cultural sensitivity of the times it went on, “Every character commonly portrayed on the stage, from the pawnshop Jew and the plantation darkey, the heathen Chinee (sic) was there in half a dozen places.”

Moving on.

“At Sixth and Main streets a stop was made, and with the devil’s blacksmith shop as a backdrop and the red lights from The Statesman office lighting up the scene, the maskers staged the devil’s ball to the tune of that popular rag in a manner that would have set a grove of weeping willows to laughter.”

Now, there’s a metaphor you don’t often see.

When the parade was done, a dance commenced in front of the statehouse. “The capitol steps were black with humanity, and no space from which one could obtain a view of the dance space was vacant.”

All in all, good, clean fun. So, Boise kind of owns the name, however you spell it. It sounds way more entertaining than any parade I’ve ever seen in town. Someone should claim the name—however you want to spell it—and fest away. In 1913 The Idaho Statesman ran a full page about the semicentennial celebration, including the above pictures of the parade. The Hornikabrinika was a part of the parade, but other entries were less tongue-in-cheek.

In 1913 The Idaho Statesman ran a full page about the semicentennial celebration, including the above pictures of the parade. The Hornikabrinika was a part of the parade, but other entries were less tongue-in-cheek.

A rare Hornikibrinika pin.

A rare Hornikibrinika pin.

There was little spate of interest in Hornikabrinka in 1968 when a reader asked the Action Post columnist at the Statesman about it. They provided an answer that, though sketchy, set me on the right track. The columnist spelled it Hornikibrinki. The spelling of the event also included Horniki Brinki and Hornika Brinka in some references.

Speculation about exactly what it was, what it meant, and how it started seemed to be part of the fun. A headline from the August 1913 Idaho Statesman read “Hornika Brinika—What’s His Batting Average?” The reporter had walked around town asking people what the word or words meant to them. “Is it a drink, a germ, or a disease?”

During the 1913 celebration, it was billed as a revival of the tradition from around the founding of Boise. George Washington Stilts, a well-known practical joker in town during those earliest days, seemed to be one of the ringleaders of those celebrations. Which were exactly what?

Think Mardis Gras.

The September 27 Idaho Statesman had a full page about the festivities, headlined, “FROLIC OF THE FUNMAKERS—Mask Parade and Street Dance a Wild Revel of Pleasure.” The article began, “Herniki Briniki—symbol for expression of a wild, care free, abandoned, and yet not unduly boisterous variety of mirth that only that phrase will describe…” It continued “Fully 500 maskers took part in the parade, and such costumes! From the beautiful to the ridiculous, with the emphasis on the latter, they ranged, in a kaleidoscopic and seemingly endless variety.”

Then, showing the cultural sensitivity of the times it went on, “Every character commonly portrayed on the stage, from the pawnshop Jew and the plantation darkey, the heathen Chinee (sic) was there in half a dozen places.”

Moving on.

“At Sixth and Main streets a stop was made, and with the devil’s blacksmith shop as a backdrop and the red lights from The Statesman office lighting up the scene, the maskers staged the devil’s ball to the tune of that popular rag in a manner that would have set a grove of weeping willows to laughter.”

Now, there’s a metaphor you don’t often see.

When the parade was done, a dance commenced in front of the statehouse. “The capitol steps were black with humanity, and no space from which one could obtain a view of the dance space was vacant.”

All in all, good, clean fun. So, Boise kind of owns the name, however you spell it. It sounds way more entertaining than any parade I’ve ever seen in town. Someone should claim the name—however you want to spell it—and fest away.

In 1913 The Idaho Statesman ran a full page about the semicentennial celebration, including the above pictures of the parade. The Hornikabrinika was a part of the parade, but other entries were less tongue-in-cheek.

In 1913 The Idaho Statesman ran a full page about the semicentennial celebration, including the above pictures of the parade. The Hornikabrinika was a part of the parade, but other entries were less tongue-in-cheek. A rare Hornikibrinika pin.

A rare Hornikibrinika pin.

Published on February 21, 2020 04:00

February 20, 2020

Jane Russell's Rodeo

Last month I shared a post about early rodeos in Idaho and mentioned a time when movie star Jane Russell asked for a rodeo while she was on vacation in Idaho. Thanks to Jim Hall and Mindy Hogan, I have some additional information about that to share.

As you may recall, Jane Russell came to Idaho to relax after making her first movie, Outlaw . It was a Howard Hughes film about Billy the Kid that came out in 1943. Russell spent some time in Island Park where one of the locals pulled together a rodeo at her request.

Well, here’s the story from that “local’s” perspective.

Vearl Crystal was a young man in 1941 who had a job putting up hay for Chet Ellicott, the owner of a nearby dude ranch. “One day,” wrote Vearl, “Chet Ellicott came out to the field where we were putting up hay and told me he had a guest at the ranch who wanted a rodeo for publicity purposes. I told him I could do it, but I didn’t have any chutes to put the calves and steers and cows for wild cow milking into. He said I could have the whole haying crew for 24 hours to build whatever we needed.

“The guest turned out to be Jane Russell, the movie star,” Crystal went on. “Chet introduced me to Jane Russell and her co-star, Jack Buetel, as a rodeo cowboy. We put on a small but realistic rodeo with lots of pictures. I still have a copy of the old click magazine with all the pictures they used for publicity.”

Local officials were impressed with the publicity the little rodeo got, so they asked Crystal to put on an Island Park rodeo. The war put that on hold until 1946. That first rodeo was called the Island Park Wild Horse Stampede. It continued until at about 2008. The Crystal brothers, Vearl and DeMont produced that rodeo for years, as well as many others as the Crystal Brothers Rodeo Company.

Vearl Crystal passed away in 2011.

As you may recall, Jane Russell came to Idaho to relax after making her first movie, Outlaw . It was a Howard Hughes film about Billy the Kid that came out in 1943. Russell spent some time in Island Park where one of the locals pulled together a rodeo at her request.

Well, here’s the story from that “local’s” perspective.

Vearl Crystal was a young man in 1941 who had a job putting up hay for Chet Ellicott, the owner of a nearby dude ranch. “One day,” wrote Vearl, “Chet Ellicott came out to the field where we were putting up hay and told me he had a guest at the ranch who wanted a rodeo for publicity purposes. I told him I could do it, but I didn’t have any chutes to put the calves and steers and cows for wild cow milking into. He said I could have the whole haying crew for 24 hours to build whatever we needed.

“The guest turned out to be Jane Russell, the movie star,” Crystal went on. “Chet introduced me to Jane Russell and her co-star, Jack Buetel, as a rodeo cowboy. We put on a small but realistic rodeo with lots of pictures. I still have a copy of the old click magazine with all the pictures they used for publicity.”

Local officials were impressed with the publicity the little rodeo got, so they asked Crystal to put on an Island Park rodeo. The war put that on hold until 1946. That first rodeo was called the Island Park Wild Horse Stampede. It continued until at about 2008. The Crystal brothers, Vearl and DeMont produced that rodeo for years, as well as many others as the Crystal Brothers Rodeo Company.

Vearl Crystal passed away in 2011.

Published on February 20, 2020 04:00

February 19, 2020

The First Couple Married in Idaho

Do you know who the first non-native couple married in Idaho was? It could be difficult to track down. Still, I have a nomination. Let’s see if you know of a couple who were married in Idaho earlier.

I’m talking about a place officially named Idaho, so the first candidates would have to have been married on or after March 3, 1863, when Idaho became a territory.

My candidates are Niels and Mary Christofferson Anderson who were married in Morristown, July 30, 1863. Morristown lasted only a few years and became known as Soda Springs.

The year before, 15-year-old Mary Christofferson had been struck in the face by a cannonball, the beginning shot fired in what would be known as the Morrisite War, that took place at Kington Fort, Utah. Joseph Morris and his followers were holed up there waiting for the Second Coming when a group called the Mormon Militia came to demand the release of a prisoner they were holding. Morris had formed the breakaway Church of the Newborn when Brigham Young refused to acknowledge the prophecies of Morris.

In the siege that followed several Morrisites were killed, including their leader. About half of the followers of Morris were escorted into the newly formed Idaho Territory in May, 1863, where they founded Morristown.

Mary Anderson did not let her disfigurement—her jaw was shot off—ruin her life. She and Niels raised a thriving family. Many of their descendants live in Idaho today.

This was the shortest possible telling of the story of the Morrisite War. I give a one-hour presentation about the war to interested groups. You can also watch my YouTube video about it. The best book available on the subject is Joseph Morris: and the Saga of the Morrisites Revisited, by C. Leroy Anderson.

So, do you know of another non-native couple who were married in Idaho earlier? Mary Anderson may have been the first non-native woman married in Idaho Territory.

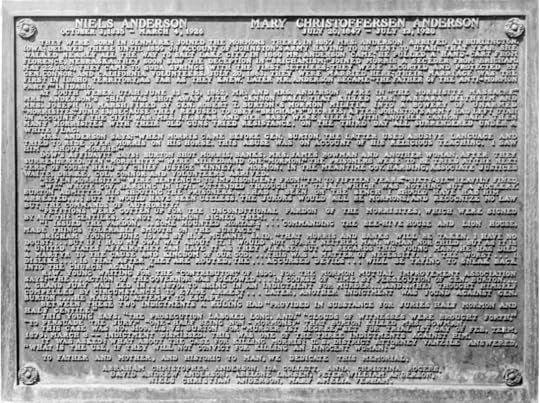

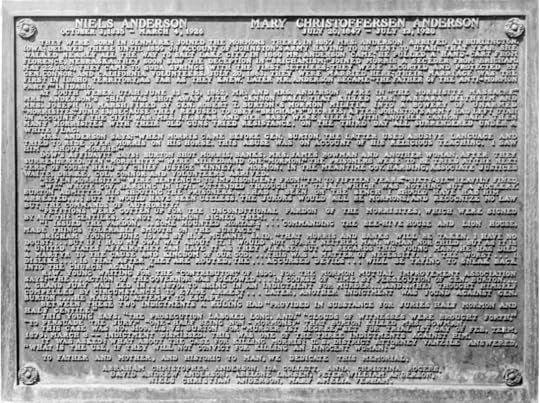

Mary Anderson may have been the first non-native woman married in Idaho Territory.  This is going to be difficult to read, but it's the grave marker of Neils and Mary Anderson. It tells the story of the Morrisites.

This is going to be difficult to read, but it's the grave marker of Neils and Mary Anderson. It tells the story of the Morrisites.

I’m talking about a place officially named Idaho, so the first candidates would have to have been married on or after March 3, 1863, when Idaho became a territory.

My candidates are Niels and Mary Christofferson Anderson who were married in Morristown, July 30, 1863. Morristown lasted only a few years and became known as Soda Springs.

The year before, 15-year-old Mary Christofferson had been struck in the face by a cannonball, the beginning shot fired in what would be known as the Morrisite War, that took place at Kington Fort, Utah. Joseph Morris and his followers were holed up there waiting for the Second Coming when a group called the Mormon Militia came to demand the release of a prisoner they were holding. Morris had formed the breakaway Church of the Newborn when Brigham Young refused to acknowledge the prophecies of Morris.

In the siege that followed several Morrisites were killed, including their leader. About half of the followers of Morris were escorted into the newly formed Idaho Territory in May, 1863, where they founded Morristown.

Mary Anderson did not let her disfigurement—her jaw was shot off—ruin her life. She and Niels raised a thriving family. Many of their descendants live in Idaho today.

This was the shortest possible telling of the story of the Morrisite War. I give a one-hour presentation about the war to interested groups. You can also watch my YouTube video about it. The best book available on the subject is Joseph Morris: and the Saga of the Morrisites Revisited, by C. Leroy Anderson.

So, do you know of another non-native couple who were married in Idaho earlier?

Mary Anderson may have been the first non-native woman married in Idaho Territory.

Mary Anderson may have been the first non-native woman married in Idaho Territory.  This is going to be difficult to read, but it's the grave marker of Neils and Mary Anderson. It tells the story of the Morrisites.

This is going to be difficult to read, but it's the grave marker of Neils and Mary Anderson. It tells the story of the Morrisites.

Published on February 19, 2020 04:00

February 18, 2020

Byron Defenbach

As a writer who focuses on the history of Idaho, I inevitably run across others who did the same, and are now a part of history themselves. Vardis Fisher, for instance, wrote quite a lot of Idaho history for the Idaho Writers Project. Most of that appeared in books produced for the Works Project Administration (WPA) effort. One writer I enjoy was Dick d’Easum. I’m particularly attracted to him because his writing style was often a little snide and quirky, something I relish, and because he, too, wrote newspaper columns and books. Dick was the information director for a state natural resources agency, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. I held the same position with the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

But enough about Dick, at least for today. This post is about a man who wrote formal Idaho history books, a popular book about Native American heroines, and a regular newspaper column. Those were all passions of Byron Defenbach, but he also had a day job. Several of them, in fact.

Defenbach was deeply involved in government almost from the time he moved to Sandpoint around 1900. In the first few years of the Twentieth Century he served as mayor of the town, the Bonner County Assessor, and had a few terms as an Idaho state senator under his belt. He was also the postmaster of Sandpoint.

In 1915, Idaho created the State Board of Accountancy. Defenbach had received a bookkeeping and accountancy certificate from Kinman Business School in Spokane, so he rushed to Boise to become a Certified Public Accountant. Defenbach family lore has it that the handful of men standing in the office waiting to be issued a certificate drew straws to see who would go first. Byron Defenbach won. He received certificate number one, making him the first CPA in Idaho. He would later serve on the Idaho State Board of Accountancy and the Idaho State Tax Commission.

Defenbach established an accounting firm in Lewiston with two sons. They also had a Pocatello office. Many snippets in Idaho newspapers across the state in the 20s and 30s tell about him coming to town to conduct an audit of city or county books.

Active in the Republican party, and an established money man, Defenbach was elected Idaho State Treasurer in 1927, serving in that office until 1930. That entailed a move to Boise, where he would make a permanent home. In 1932 he ran for governor, losing to Democrat C. Ben Ross.

It was likely not an accident that Defenbach began writing a regular column for Idaho newspapers while still state treasurer in 1928. It served to get his name in front of voters for about three years leading up to his unsuccessful run for governor.

The columns, under the title “The State We Live In,” were not strictly Idaho history. He wrote many about Idaho institutions, why they were formed, and how they were run. Not coincidentally, this showed that he had a good grasp of issues regarding state normal schools, the Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind, State Hospital South, the Old Soldiers Home, the reform school, and on and on. He wrote about gold and silver and geology in general. He wrote about the weather.

Defenbach was an Idaho booster. He was part of a campaign to make City of Rocks a national monument. In a 1929 column he called the site “Goblin City” and compared it favorably to Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave and Garden of the Gods in Colorado. He ended his column with a paragraph that summed up his feelings about the site and gave some indication of the reach of his writings: “It is strange that so few, even of Idaho people, know of its existence, and it is to be regretted that greater efforts are not made to advertise, popularize, and capitalize this possession, unquestionably one of the outstanding show places of the state we live in. How many of the thirty-odd thousand readers of the seventy Idaho papers printing this article, ever heard of it before?”

City of Rocks, jointly operated by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service, became City of Rocks National Reserve in 1988.

Byron Defenbach, author of a The State We Live In, the three-volume Idaho the Place and its People—A History of the Gem State from Prehistoric Times to the Present Days, and Red Heroines of the Northwest passed away in 1947 at age 77.

My thanks to Defenbach’s grandson, also named Byron Defenbach, for his contribution to this post.

Byron Defenbach as a dapper young man. From the Defenbach family collection.

Byron Defenbach as a dapper young man. From the Defenbach family collection.

But enough about Dick, at least for today. This post is about a man who wrote formal Idaho history books, a popular book about Native American heroines, and a regular newspaper column. Those were all passions of Byron Defenbach, but he also had a day job. Several of them, in fact.

Defenbach was deeply involved in government almost from the time he moved to Sandpoint around 1900. In the first few years of the Twentieth Century he served as mayor of the town, the Bonner County Assessor, and had a few terms as an Idaho state senator under his belt. He was also the postmaster of Sandpoint.

In 1915, Idaho created the State Board of Accountancy. Defenbach had received a bookkeeping and accountancy certificate from Kinman Business School in Spokane, so he rushed to Boise to become a Certified Public Accountant. Defenbach family lore has it that the handful of men standing in the office waiting to be issued a certificate drew straws to see who would go first. Byron Defenbach won. He received certificate number one, making him the first CPA in Idaho. He would later serve on the Idaho State Board of Accountancy and the Idaho State Tax Commission.

Defenbach established an accounting firm in Lewiston with two sons. They also had a Pocatello office. Many snippets in Idaho newspapers across the state in the 20s and 30s tell about him coming to town to conduct an audit of city or county books.

Active in the Republican party, and an established money man, Defenbach was elected Idaho State Treasurer in 1927, serving in that office until 1930. That entailed a move to Boise, where he would make a permanent home. In 1932 he ran for governor, losing to Democrat C. Ben Ross.

It was likely not an accident that Defenbach began writing a regular column for Idaho newspapers while still state treasurer in 1928. It served to get his name in front of voters for about three years leading up to his unsuccessful run for governor.

The columns, under the title “The State We Live In,” were not strictly Idaho history. He wrote many about Idaho institutions, why they were formed, and how they were run. Not coincidentally, this showed that he had a good grasp of issues regarding state normal schools, the Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind, State Hospital South, the Old Soldiers Home, the reform school, and on and on. He wrote about gold and silver and geology in general. He wrote about the weather.

Defenbach was an Idaho booster. He was part of a campaign to make City of Rocks a national monument. In a 1929 column he called the site “Goblin City” and compared it favorably to Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave and Garden of the Gods in Colorado. He ended his column with a paragraph that summed up his feelings about the site and gave some indication of the reach of his writings: “It is strange that so few, even of Idaho people, know of its existence, and it is to be regretted that greater efforts are not made to advertise, popularize, and capitalize this possession, unquestionably one of the outstanding show places of the state we live in. How many of the thirty-odd thousand readers of the seventy Idaho papers printing this article, ever heard of it before?”

City of Rocks, jointly operated by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service, became City of Rocks National Reserve in 1988.

Byron Defenbach, author of a The State We Live In, the three-volume Idaho the Place and its People—A History of the Gem State from Prehistoric Times to the Present Days, and Red Heroines of the Northwest passed away in 1947 at age 77.

My thanks to Defenbach’s grandson, also named Byron Defenbach, for his contribution to this post.

Byron Defenbach as a dapper young man. From the Defenbach family collection.

Byron Defenbach as a dapper young man. From the Defenbach family collection.

Published on February 18, 2020 04:00

February 17, 2020

Edgar Miller

Edgar Miller was born in or near Idaho Falls a few weeks before the turn to the Twentieth Century. He was destined to become a major force in the art and design worlds in that century.

Miller knocked around with his brother exploring what there was to explore near his home growing up. They would go camping for days in the nearby hills, where Edgar drew. And drew. Creating pictures of wildflowers was a passion. One of his high school teachers saw his talent and got him accepted at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1917.

He took to the city the way he took to his art, eventually creating a live-work art community much of which exists still today. Most famous for his stained glass, he was a pioneer in graphic art advertising, and influential in architecture.

Miller loved growing up in Idaho. He saw a painting of Custer’s Last Stand when he was four and from that moment wanted nothing more than to be an artist. He began sketching everything he saw. Much of his work was inspired by his childhood in and around the frontier town.

For more on Edgar Miller, see this Time Magazine slideshow of his work. A comprehensive article about Miller is available from on the CITYLAB website. The Edgar Miller Legacy is a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the art and "handmade homes" he created. Finally, there is quite a lavish book called Edgar Miller and the Hand-Made Home: Chicago's Forgotten Renaissance Man.

Thanks to architectural historian Julie Williams of Idaho Falls for telling me about Edgar Miller.

Miller knocked around with his brother exploring what there was to explore near his home growing up. They would go camping for days in the nearby hills, where Edgar drew. And drew. Creating pictures of wildflowers was a passion. One of his high school teachers saw his talent and got him accepted at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1917.

He took to the city the way he took to his art, eventually creating a live-work art community much of which exists still today. Most famous for his stained glass, he was a pioneer in graphic art advertising, and influential in architecture.

Miller loved growing up in Idaho. He saw a painting of Custer’s Last Stand when he was four and from that moment wanted nothing more than to be an artist. He began sketching everything he saw. Much of his work was inspired by his childhood in and around the frontier town.

For more on Edgar Miller, see this Time Magazine slideshow of his work. A comprehensive article about Miller is available from on the CITYLAB website. The Edgar Miller Legacy is a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the art and "handmade homes" he created. Finally, there is quite a lavish book called Edgar Miller and the Hand-Made Home: Chicago's Forgotten Renaissance Man.

Thanks to architectural historian Julie Williams of Idaho Falls for telling me about Edgar Miller.

Published on February 17, 2020 04:00

February 16, 2020

Cynthia Mann

Cynthia Mann arrived in Boise an invalid in June 1879. Her journey across southern Idaho, lying on a pallet on the floor of a stagecoach, had been so brutal that at one point she begged to be left at a stage station so she could die beneath a roof.

Born in Kentucky, educated in Kansas, Cynthia Mann began teaching when she was just 18. At age 26 her husband, Samuel Mann, whom she would later divorce, brought her to Boise in the hopes that the change of climate might improve her health. Something did, for she became a dynamo in local affairs related to education, suffrage, politics, and prohibition.

Mann taught at several schools in Boise and in nearby communities. She was often mentioned in early papers as a teacher at Cloverdale, Cole, Central School, and Park School. She was one of the organizers of the Idaho State Teachers Association, and in 1906 ran for Superintendent of Public Schools on the Prohibitionist ticket.

“Lady Mann” was the affectionate nickname given to her by students, who were intensely loyal to her. She taught hundreds of children, and the children of those children, through the years. She is best remembered as the teacher of the “ungraded” school at the Children’s Home Finding and Aid Society of Idaho. That organization began in 1908 as a residence and adoption center for homeless children. It exists today as the Children’s Home Society of Idaho, carrying on its mission of placing children in good homes, though it is no longer a residence institution.

The handsome stone building, designed by Tourtellotte and Company, for the Children’s Home Finding and Aid Society of Idaho is located at 740 E. Warm Springs Avenue. It is so located because of Cynthia Mann. Never a wealthy woman, Mann was savvy about real estate and owned a fair amount of it. She donated almost the entire block where the Society is located today, then went on to make many more donations large and small over the years.

Cynthia Mann was sometimes called a “club woman.” She tirelessly supported education and political reform as one of the early members of the Columbian Club and a founding member of the Boise chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was active in the YWCA, the Business Women’s Club, and the Council of Women Voters.

Man spoke often on the history of suffrage in Idaho and went to Washington, DC more than once to lobby for national women’s suffrage. It was on a trip to DC to visit her brother in 1911 when she almost met her end.

Mrs. Mann was reading the inscription on a “Peace Monument,” erected in memory of soldiers and sailors when a woman driving a horse and buggy knocked her down and ran over her. Bleeding from severe facial injuries and dazed, she was taken to a local Casualty hospital that had a shady reputation.

As she told the story, “I was badly cut about the face, in two places on my lip, sustained a bad gash in my forehead, and my feet were bruised. My head was bothering me more than any other portion of my anatomy, and it was just 24 hours after I begged for it that I got any ice to put on it, and this in the face of the terrible summer heat.”

To her good fortune, Addison T. Smith, secretary to Senator Weldon B. Heyburn of Idaho, read about her accident in the newspaper. “Mr. Smith came for me at once and insisted on taking me to his home and I feel that I owe my life to him and Mrs. Smith.”

The Idaho Statesman, in reporting about the incident, called Cynthia Mann “perhaps the greatest philanthropist in the state of Idaho.”

To, as they say, add insult to injury, Mann was robbed by a nurse while in the hospital. She got her $20 back only after Smith and a Congressman French put pressure on the institution.

Cynthia Mann continued her activism and her teaching until February of 1920. She qualified for a small pension, but at age 66 refused to quit teaching. Her health was starting to fail, so she got her affairs in order, which in her case meant creating a will that gave her remaining funds to her beloved clubs, for hospital work in South America, and $800 for the rehabilitation of a small village, Tilliloy, in northern France. She left most of the money for the construction of the Ward Massacre site monument to the Pioneer Chapter of the D.A.R.

On February 6, 1920, Cynthia Mann died of pneumonia following a bout of influenza.

Lady Mann planned her own funeral to the last detail. The following is a portion of what was read at the service, at her request.

“I had a dream which was not all a dream. I dreamed I was the children’s friend, that I loved them enough to give them pain, if by so doing, they might grow up good and true and beautiful in the sight of God. I loved them enough to go without what was unnecessary that they might have what would put good things into their lives: sweet thoughts and beautiful memories.”

Also at her request, Cynthia Mann’s body was carried by a group of her early pupils to be put to rest in Morris Hill Cemetery. Her marker reads, “It was Happiness to Serve.”

Cynthia Mann, for whom Cynthia Mann Elementary is named, arrived in Boise in 1879 in such poor health she was unable to stand. Over the next 41 years she would become known as “the children’s friend” and one of Idaho’s best-known philanthropists. This photo was taken of her when she was Cynthia Pease, age 16, in Lawrence, Kansas. Photo Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Cynthia Mann, for whom Cynthia Mann Elementary is named, arrived in Boise in 1879 in such poor health she was unable to stand. Over the next 41 years she would become known as “the children’s friend” and one of Idaho’s best-known philanthropists. This photo was taken of her when she was Cynthia Pease, age 16, in Lawrence, Kansas. Photo Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Born in Kentucky, educated in Kansas, Cynthia Mann began teaching when she was just 18. At age 26 her husband, Samuel Mann, whom she would later divorce, brought her to Boise in the hopes that the change of climate might improve her health. Something did, for she became a dynamo in local affairs related to education, suffrage, politics, and prohibition.

Mann taught at several schools in Boise and in nearby communities. She was often mentioned in early papers as a teacher at Cloverdale, Cole, Central School, and Park School. She was one of the organizers of the Idaho State Teachers Association, and in 1906 ran for Superintendent of Public Schools on the Prohibitionist ticket.

“Lady Mann” was the affectionate nickname given to her by students, who were intensely loyal to her. She taught hundreds of children, and the children of those children, through the years. She is best remembered as the teacher of the “ungraded” school at the Children’s Home Finding and Aid Society of Idaho. That organization began in 1908 as a residence and adoption center for homeless children. It exists today as the Children’s Home Society of Idaho, carrying on its mission of placing children in good homes, though it is no longer a residence institution.

The handsome stone building, designed by Tourtellotte and Company, for the Children’s Home Finding and Aid Society of Idaho is located at 740 E. Warm Springs Avenue. It is so located because of Cynthia Mann. Never a wealthy woman, Mann was savvy about real estate and owned a fair amount of it. She donated almost the entire block where the Society is located today, then went on to make many more donations large and small over the years.

Cynthia Mann was sometimes called a “club woman.” She tirelessly supported education and political reform as one of the early members of the Columbian Club and a founding member of the Boise chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was active in the YWCA, the Business Women’s Club, and the Council of Women Voters.

Man spoke often on the history of suffrage in Idaho and went to Washington, DC more than once to lobby for national women’s suffrage. It was on a trip to DC to visit her brother in 1911 when she almost met her end.

Mrs. Mann was reading the inscription on a “Peace Monument,” erected in memory of soldiers and sailors when a woman driving a horse and buggy knocked her down and ran over her. Bleeding from severe facial injuries and dazed, she was taken to a local Casualty hospital that had a shady reputation.

As she told the story, “I was badly cut about the face, in two places on my lip, sustained a bad gash in my forehead, and my feet were bruised. My head was bothering me more than any other portion of my anatomy, and it was just 24 hours after I begged for it that I got any ice to put on it, and this in the face of the terrible summer heat.”

To her good fortune, Addison T. Smith, secretary to Senator Weldon B. Heyburn of Idaho, read about her accident in the newspaper. “Mr. Smith came for me at once and insisted on taking me to his home and I feel that I owe my life to him and Mrs. Smith.”

The Idaho Statesman, in reporting about the incident, called Cynthia Mann “perhaps the greatest philanthropist in the state of Idaho.”

To, as they say, add insult to injury, Mann was robbed by a nurse while in the hospital. She got her $20 back only after Smith and a Congressman French put pressure on the institution.

Cynthia Mann continued her activism and her teaching until February of 1920. She qualified for a small pension, but at age 66 refused to quit teaching. Her health was starting to fail, so she got her affairs in order, which in her case meant creating a will that gave her remaining funds to her beloved clubs, for hospital work in South America, and $800 for the rehabilitation of a small village, Tilliloy, in northern France. She left most of the money for the construction of the Ward Massacre site monument to the Pioneer Chapter of the D.A.R.

On February 6, 1920, Cynthia Mann died of pneumonia following a bout of influenza.

Lady Mann planned her own funeral to the last detail. The following is a portion of what was read at the service, at her request.

“I had a dream which was not all a dream. I dreamed I was the children’s friend, that I loved them enough to give them pain, if by so doing, they might grow up good and true and beautiful in the sight of God. I loved them enough to go without what was unnecessary that they might have what would put good things into their lives: sweet thoughts and beautiful memories.”

Also at her request, Cynthia Mann’s body was carried by a group of her early pupils to be put to rest in Morris Hill Cemetery. Her marker reads, “It was Happiness to Serve.”

Cynthia Mann, for whom Cynthia Mann Elementary is named, arrived in Boise in 1879 in such poor health she was unable to stand. Over the next 41 years she would become known as “the children’s friend” and one of Idaho’s best-known philanthropists. This photo was taken of her when she was Cynthia Pease, age 16, in Lawrence, Kansas. Photo Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Cynthia Mann, for whom Cynthia Mann Elementary is named, arrived in Boise in 1879 in such poor health she was unable to stand. Over the next 41 years she would become known as “the children’s friend” and one of Idaho’s best-known philanthropists. This photo was taken of her when she was Cynthia Pease, age 16, in Lawrence, Kansas. Photo Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on February 16, 2020 04:00

February 15, 2020

Hugh Whitney Got Away, Part 3

Part One

Part Two

This is part three of a three-part story about Hugh Whitney. Previously I told you about his robbing a saloon in Monida, Montana, then hopping on a train into Idaho. He was briefly arrested on board the train by a deputy who had gotten on in Spencer, Idaho for that purpose. When the cuffs came out he shot the deputy, then the train conductor. The latter later died. Yesterday we ended with Whitney shooting three fingers off the hand of a deputy who tried to stop him when he crossed the Menan Bridge.

After that, wanted posters went up across a three-state area offering a $500 reward. This was before anyone knew much about Whitney, other than he was a cowhand and a killer, probably from Cokeville, Wyoming. Then officials found out he had grown up on a ranch in Adams County, Idaho, about three miles south of Council, where his parents still lived. Idaho Governor James Hawley added $500 to the reward money, and Oregon Shortline officials put in another $1,000.

It was about that time Whitney became a ghost and a boogeyman. He was nowhere and everywhere, terrorizing gentle folks with his very existence.

Sightings came in from Idaho, Montana, Utah, and Wyoming. On August 13, the Idaho Statesman reported that Whitney had been arrested in Rexburg. Except it turned out not to be Whitney, but a young man from Boise who had wandered away from his surveying crew and gotten lost.

Then, on September 10, Whitney was positively seen, along with his brother, Charles, holding up a bank in Cokeville, Wyoming. The brothers had worked as sheepherders in the area but had been fired because Hugh Whitney had a habit of herding sheep by firing his pistol at them. The Whitneys stole about $500, mostly from 14 bank customers since the safe was on a timer and couldn’t be opened for them. When they finished with their collection of offerings, they mounted up and, shooting as they went, galloped out of town. Hugh Whitney got away.

Large posses from Cokeville and Afton, Wyoming, as well as Montepelier, Idaho pursued the pair. The brothers were spotted crossing a toll bridge at Chubb Springs not far from the Blackfoot Reservoir. Posses from Idaho Falls and Rexburg set out to intercept them.

On September 15, the Montpelier paper carried a story of a sighting of the Whitneys there. In the same issue the paper took umbrage over a dispatch from Cokeville that went to the Salt Lake Herald-Republican that claimed the pair had been hiding out in Montpelier for weeks with the aid of local residents.

On September 18, reports hit the papers that posses were closing in on Hugh Whitney near the Idaho Wyoming border.

On September 22, the Whitneys were surely the two masked men who robbed a resort at Hailey and shot a musician dead.

The ghostly Whitneys then made a series of appearances, starting with their capture in Montpelier by two homesteaders. Then Hugh was taken into custody in a Pocatello barber shop. Then he was captured in Mackay. Except, no, he wasn’t. That rounded out 1912.

In July, 1913, Whitney showed up in The Pocatello Tribune if not in Rigby, where he might have robbed a bank. At this point, you would be well advised to get a refreshment of your choice and settle in for the reading of the next sentence, which I will quote verbatim. “That it was Hugh Whitney, notorious Wyoming and Idaho desperado, who held up the bank at Rigby Tuesday afternoon, escaping with $3500; that he eluded a sheriff’s posse by swinging around by Willow Creek and back to the main line of the Short Line at Firth; that he boarded train No. 2, southbound, early yesterday morning, alighting at Pocatello and taking eastbound train No. 5, bound for his Wyoming haunts; that a saddle horse left near the station at Firth with a sack of silver tied to the horn belonged to the desperado; that he is by this time safe among his friends somewhere north of Cokeville, and that it is useless to search further for him, is the belief of local officers of the law, who yesterday afternoon received word from Firth that a saddle horse was found hitched there yesterday morning, with a sack of silver tied to the saddlehorn.”

I hope you took a breath.

In September of 1913, Salt Lake officials captured Whitney. No, they didn’t. A few days later he was sighted all over town in Pocatello. No, he wasn’t.

On September 27, The Idaho Statesman quipped that “Any town that wants to be sure to stay on the map should at once capture Bandit Hugh Whitney.”

By March 1914, Whitney Fever had yet to subside. The Statesman reported that a “desperate looking character” was trailed by reporters hoping for a scoop, only to find it was a local man who had just returned from a wool-buying trip in Oregon.

In July of 1914, three years after the murder of Conductor Kidd, they had Whitney at last. He was involved in the robbery of a train near Pendleton, Oregon. Two outlaws got away, but the “body of the dead desperado (was) positively identified as that of Hugh Whitney.”

Alas, no it wasn’t. The body had been identified because there was a watch that purportedly belonged to Whitney among the man’s belongings.

In 1915, speculation was high that the man holding a prominent Bingham County rancher for ransom was Hugh Whitney. He wasn’t.

The fever cooled for a while, but in 1925 Reno, Nevada police thought they had Hugh Whitney in custody. Say it with me, “they didn’t.”

In 1926, Hugh Whitney was killed during a bank robbery in Roseville, California. Not.

Hugh Whitney, according to The Post Register of March 10, 1932, was living somewhere in the area of Idaho Falls. Montana officers had tipped them off that Whitney was living incognito so near to the many places he had frequented (or not) some 21 years earlier. The excitement soon faded away.

Little was heard of Hugh Whitney, save for those “25 years ago” columns until 1951. That’s when a rancher named Frank S. Taylor sat down for a little talk with the governor of Montana, whom he knew. “Frank” had a confession to make.

Frank Taylor was actually Charlie Whitney, brother of the notorious Hugh and sometimes partner in crime. He was coming forward to confess, because Hugh Whitney had died. Charlie wanted to come clean.

It seems the brothers had fled the West after the Cokeville bank robbery. They lived in Wisconsin and Minnesota for about a year, then changed their names and moved to Montana. They worked as ranch hands near Glasgow in northeastern Montana.

The brothers both enlisted in the army during WWI and fought in France. They returned to Montana after the war, but Hugh went to Saskatchewan in 1935, where he prospered as a rancher. On his deathbed Hugh had confessed to his crimes and absolved Charlie of participation in any of them, except for the Cokeville bank robbery.

Montana’s governor sent Wyoming’s governor a letter recommending clemency for Charlie’s role in that hold up.

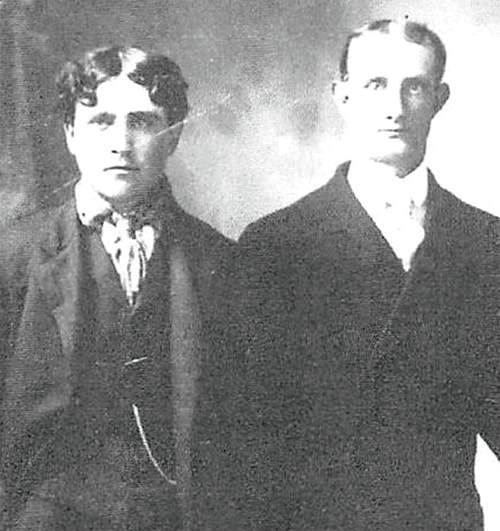

Charlie Whitney-cum-Frank Taylor traveled to Cheyenne to face whatever music was playing there. He spent ten days in jail while a judge, named Robert Christmas, contemplated his fate. The Christmas present was that the judge saw no point in punishing the 63-year-old-man for robbing a bank that no longer existed. He pardoned Charlie, who returned to ranching in Montana, where he passed away in 1968. But Hugh? Hugh Whitney got away. Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Part Two

This is part three of a three-part story about Hugh Whitney. Previously I told you about his robbing a saloon in Monida, Montana, then hopping on a train into Idaho. He was briefly arrested on board the train by a deputy who had gotten on in Spencer, Idaho for that purpose. When the cuffs came out he shot the deputy, then the train conductor. The latter later died. Yesterday we ended with Whitney shooting three fingers off the hand of a deputy who tried to stop him when he crossed the Menan Bridge.

After that, wanted posters went up across a three-state area offering a $500 reward. This was before anyone knew much about Whitney, other than he was a cowhand and a killer, probably from Cokeville, Wyoming. Then officials found out he had grown up on a ranch in Adams County, Idaho, about three miles south of Council, where his parents still lived. Idaho Governor James Hawley added $500 to the reward money, and Oregon Shortline officials put in another $1,000.

It was about that time Whitney became a ghost and a boogeyman. He was nowhere and everywhere, terrorizing gentle folks with his very existence.

Sightings came in from Idaho, Montana, Utah, and Wyoming. On August 13, the Idaho Statesman reported that Whitney had been arrested in Rexburg. Except it turned out not to be Whitney, but a young man from Boise who had wandered away from his surveying crew and gotten lost.

Then, on September 10, Whitney was positively seen, along with his brother, Charles, holding up a bank in Cokeville, Wyoming. The brothers had worked as sheepherders in the area but had been fired because Hugh Whitney had a habit of herding sheep by firing his pistol at them. The Whitneys stole about $500, mostly from 14 bank customers since the safe was on a timer and couldn’t be opened for them. When they finished with their collection of offerings, they mounted up and, shooting as they went, galloped out of town. Hugh Whitney got away.

Large posses from Cokeville and Afton, Wyoming, as well as Montepelier, Idaho pursued the pair. The brothers were spotted crossing a toll bridge at Chubb Springs not far from the Blackfoot Reservoir. Posses from Idaho Falls and Rexburg set out to intercept them.

On September 15, the Montpelier paper carried a story of a sighting of the Whitneys there. In the same issue the paper took umbrage over a dispatch from Cokeville that went to the Salt Lake Herald-Republican that claimed the pair had been hiding out in Montpelier for weeks with the aid of local residents.

On September 18, reports hit the papers that posses were closing in on Hugh Whitney near the Idaho Wyoming border.

On September 22, the Whitneys were surely the two masked men who robbed a resort at Hailey and shot a musician dead.

The ghostly Whitneys then made a series of appearances, starting with their capture in Montpelier by two homesteaders. Then Hugh was taken into custody in a Pocatello barber shop. Then he was captured in Mackay. Except, no, he wasn’t. That rounded out 1912.

In July, 1913, Whitney showed up in The Pocatello Tribune if not in Rigby, where he might have robbed a bank. At this point, you would be well advised to get a refreshment of your choice and settle in for the reading of the next sentence, which I will quote verbatim. “That it was Hugh Whitney, notorious Wyoming and Idaho desperado, who held up the bank at Rigby Tuesday afternoon, escaping with $3500; that he eluded a sheriff’s posse by swinging around by Willow Creek and back to the main line of the Short Line at Firth; that he boarded train No. 2, southbound, early yesterday morning, alighting at Pocatello and taking eastbound train No. 5, bound for his Wyoming haunts; that a saddle horse left near the station at Firth with a sack of silver tied to the horn belonged to the desperado; that he is by this time safe among his friends somewhere north of Cokeville, and that it is useless to search further for him, is the belief of local officers of the law, who yesterday afternoon received word from Firth that a saddle horse was found hitched there yesterday morning, with a sack of silver tied to the saddlehorn.”

I hope you took a breath.

In September of 1913, Salt Lake officials captured Whitney. No, they didn’t. A few days later he was sighted all over town in Pocatello. No, he wasn’t.

On September 27, The Idaho Statesman quipped that “Any town that wants to be sure to stay on the map should at once capture Bandit Hugh Whitney.”

By March 1914, Whitney Fever had yet to subside. The Statesman reported that a “desperate looking character” was trailed by reporters hoping for a scoop, only to find it was a local man who had just returned from a wool-buying trip in Oregon.

In July of 1914, three years after the murder of Conductor Kidd, they had Whitney at last. He was involved in the robbery of a train near Pendleton, Oregon. Two outlaws got away, but the “body of the dead desperado (was) positively identified as that of Hugh Whitney.”

Alas, no it wasn’t. The body had been identified because there was a watch that purportedly belonged to Whitney among the man’s belongings.

In 1915, speculation was high that the man holding a prominent Bingham County rancher for ransom was Hugh Whitney. He wasn’t.

The fever cooled for a while, but in 1925 Reno, Nevada police thought they had Hugh Whitney in custody. Say it with me, “they didn’t.”

In 1926, Hugh Whitney was killed during a bank robbery in Roseville, California. Not.

Hugh Whitney, according to The Post Register of March 10, 1932, was living somewhere in the area of Idaho Falls. Montana officers had tipped them off that Whitney was living incognito so near to the many places he had frequented (or not) some 21 years earlier. The excitement soon faded away.

Little was heard of Hugh Whitney, save for those “25 years ago” columns until 1951. That’s when a rancher named Frank S. Taylor sat down for a little talk with the governor of Montana, whom he knew. “Frank” had a confession to make.

Frank Taylor was actually Charlie Whitney, brother of the notorious Hugh and sometimes partner in crime. He was coming forward to confess, because Hugh Whitney had died. Charlie wanted to come clean.

It seems the brothers had fled the West after the Cokeville bank robbery. They lived in Wisconsin and Minnesota for about a year, then changed their names and moved to Montana. They worked as ranch hands near Glasgow in northeastern Montana.

The brothers both enlisted in the army during WWI and fought in France. They returned to Montana after the war, but Hugh went to Saskatchewan in 1935, where he prospered as a rancher. On his deathbed Hugh had confessed to his crimes and absolved Charlie of participation in any of them, except for the Cokeville bank robbery.

Montana’s governor sent Wyoming’s governor a letter recommending clemency for Charlie’s role in that hold up.

Charlie Whitney-cum-Frank Taylor traveled to Cheyenne to face whatever music was playing there. He spent ten days in jail while a judge, named Robert Christmas, contemplated his fate. The Christmas present was that the judge saw no point in punishing the 63-year-old-man for robbing a bank that no longer existed. He pardoned Charlie, who returned to ranching in Montana, where he passed away in 1968. But Hugh? Hugh Whitney got away.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Hugh Whitney and Charles Whitney before they robbed the Cokeville, Wyoming bank in 1911.

Published on February 15, 2020 04:00