Rick Just's Blog, page 173

January 25, 2020

On the Road Again

I’m an Idaho native. My family came here about six weeks after it became a territory in 1863. I have some pride in my roots, but I’ve never thought it gave me any special status. How smart was I to be born here?

I’ve met many Idahoans who were born somewhere else but moved here on purpose and came to be as Idaho as you can get. Merle Wells, Cort Conley, Robert E. Smylie, Cecil Andrus, and Tom Trusky spring immediately to mind. So does Alan Minskoff.

Alan was born in New York. He moved to Idaho in 1970 after dropping out of grad school. The night he arrived he drove up to Bogus Basin and saw his first coyote. He fell in love with the place and by 1974 was the editor of the newly formed Idaho Heritage Magazine. He would later run Boise Magazine. Today he is a writer and journalism professor at the College of Idaho.

When he was running Idaho Heritage, a non-profit, Minskoff received a grant from the Idaho Humanities Council for a project called A Future for the Small Town in Idaho. As a part of that project he visited 24 small Idaho towns and learned about their histories and what made them tick. That was in 1976 and 1977. The magazine did a couple of special editions based on the project.

Then, more than 40 years later, Minskoff had an idea. What if he went back to those towns to reprise the project, looking for changes and for things that had not changed? Oh, and sampling the best pie in Idaho along the way.

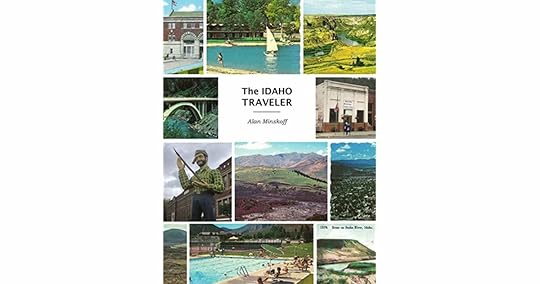

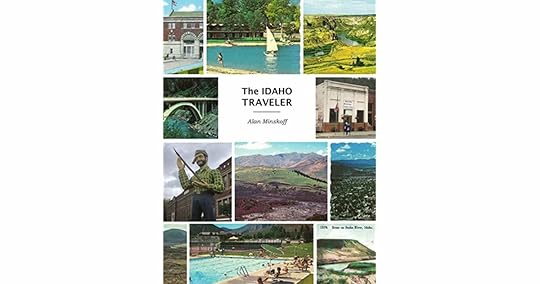

The result of this little brainstorm is a new book called The IDAHO TRAVELER ,* published by the legendary Caxton Press in Caldwell. It’s part autobiography, part travel guide, and part pie joint review. It’s about the small towns, but also includes things you didn’t know about Boise, Pocatello, Coeur d’Alene, Moscow, and Meridian.

You’ll meet the fascinating people that live in small town Idaho and begin to understand why they do. You’ll also meet Minskoff, an Idahoan who just happened to be born in New York.

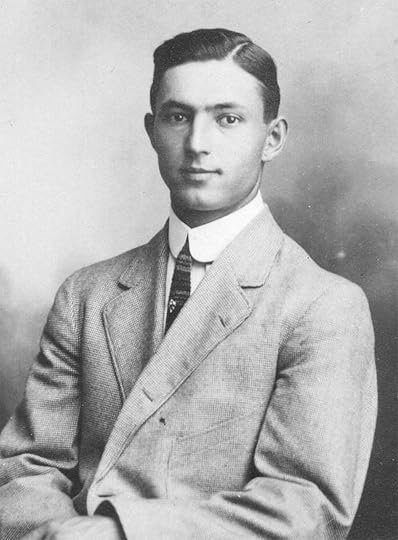

Alan Minskoff

Alan Minskoff

I’ve met many Idahoans who were born somewhere else but moved here on purpose and came to be as Idaho as you can get. Merle Wells, Cort Conley, Robert E. Smylie, Cecil Andrus, and Tom Trusky spring immediately to mind. So does Alan Minskoff.

Alan was born in New York. He moved to Idaho in 1970 after dropping out of grad school. The night he arrived he drove up to Bogus Basin and saw his first coyote. He fell in love with the place and by 1974 was the editor of the newly formed Idaho Heritage Magazine. He would later run Boise Magazine. Today he is a writer and journalism professor at the College of Idaho.

When he was running Idaho Heritage, a non-profit, Minskoff received a grant from the Idaho Humanities Council for a project called A Future for the Small Town in Idaho. As a part of that project he visited 24 small Idaho towns and learned about their histories and what made them tick. That was in 1976 and 1977. The magazine did a couple of special editions based on the project.

Then, more than 40 years later, Minskoff had an idea. What if he went back to those towns to reprise the project, looking for changes and for things that had not changed? Oh, and sampling the best pie in Idaho along the way.

The result of this little brainstorm is a new book called The IDAHO TRAVELER ,* published by the legendary Caxton Press in Caldwell. It’s part autobiography, part travel guide, and part pie joint review. It’s about the small towns, but also includes things you didn’t know about Boise, Pocatello, Coeur d’Alene, Moscow, and Meridian.

You’ll meet the fascinating people that live in small town Idaho and begin to understand why they do. You’ll also meet Minskoff, an Idahoan who just happened to be born in New York.

Alan Minskoff

Alan Minskoff

Published on January 25, 2020 04:00

January 24, 2020

J.R. Simplot’s Seed Money

J.R. Simplots origin story, as it were, is well known because he loved telling it. It’s a great story, so I’ll tell it again. By origin, I mean how he got to be wealthy.

John Richard Simplot understood how to make a dollar. He struck out on his own at age 14, leaving family and school behind. Not far behind, though. Simplot moved into a boarding house in his hometown of Declo to avoid arguments with his father. Leaving school at that age was quite common at the time. Young men had to get on with their working lives.

Simplot learned the basics of being a billionaire in that boarding house because of the eight school teachers who also boarded there for a dollar a day. Those teachers may have made some effort to pass on some knowledge to Simplot, but what he really learned was that they were willing to pass on half their salaries to him.

It was the middle of the Great Depression and money was tight. Teachers were paid not in dollars, but in scrip. Scrip was essentially an IOU, promising to pay the teachers at a later date, with a little interest. The teachers couldn’t wait until a later date, because they had bills to pay right then, such as what it cost to stay at the boarding house.

J.R. had left his home with $80 in gold certificates, money he had made from the sale of fat lambs. Carrying around that much money during hard times wasn’t wise, so he started a bank account. When he found out the boarding house residents were willing to sell their scrip to him for half its face value, he put that account to good use. He could afford to wait until the scrip matured.

In his biography, J.R Simplot—A billion the hard way*, by Louie Attebery, Simplot is quoted as saying, “It wasn’t a lotta money, but it was enough to make some money. I’d buy that scrip every month when [they got paid]. They had to pay their board bill…Damn board bill was about half their [salary]. Tough. You talk about tough times; they were tough! Tough, boy! But I accumulated a few hundred dollars, and I made some money.”

He had a lot of stories like that, because spotting a bargain or a deal was his life. Simplot was known as the potato king because his company invented a way to process French fries that caught on just a little bit with companies such as McDonalds. He was big in fertilizer, raising cattle, and funding the development of microchips. The latter proving that he never lost the business acumen that he gained back at that boarding house in Declo.

J.R. Simplot was Idaho’s first billionaire. In 2007 he was the 89th richest person in the United States, with a personal fortune estimated to be about $3.6 billion dollars. When he passed away in 2008 at age 99, Jack Simplot was the oldest billionaire on the Forbes 400 list.

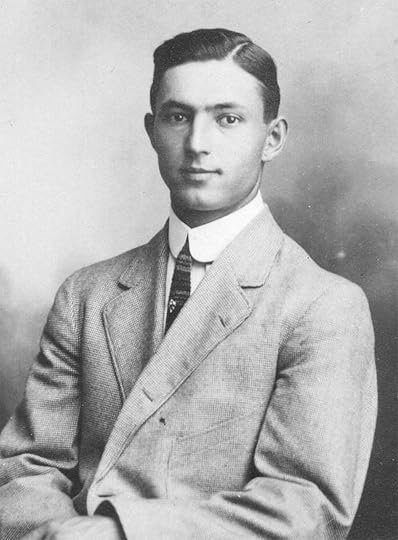

J.R. Simplot in 1961. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

J.R. Simplot in 1961. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

John Richard Simplot understood how to make a dollar. He struck out on his own at age 14, leaving family and school behind. Not far behind, though. Simplot moved into a boarding house in his hometown of Declo to avoid arguments with his father. Leaving school at that age was quite common at the time. Young men had to get on with their working lives.

Simplot learned the basics of being a billionaire in that boarding house because of the eight school teachers who also boarded there for a dollar a day. Those teachers may have made some effort to pass on some knowledge to Simplot, but what he really learned was that they were willing to pass on half their salaries to him.

It was the middle of the Great Depression and money was tight. Teachers were paid not in dollars, but in scrip. Scrip was essentially an IOU, promising to pay the teachers at a later date, with a little interest. The teachers couldn’t wait until a later date, because they had bills to pay right then, such as what it cost to stay at the boarding house.

J.R. had left his home with $80 in gold certificates, money he had made from the sale of fat lambs. Carrying around that much money during hard times wasn’t wise, so he started a bank account. When he found out the boarding house residents were willing to sell their scrip to him for half its face value, he put that account to good use. He could afford to wait until the scrip matured.

In his biography, J.R Simplot—A billion the hard way*, by Louie Attebery, Simplot is quoted as saying, “It wasn’t a lotta money, but it was enough to make some money. I’d buy that scrip every month when [they got paid]. They had to pay their board bill…Damn board bill was about half their [salary]. Tough. You talk about tough times; they were tough! Tough, boy! But I accumulated a few hundred dollars, and I made some money.”

He had a lot of stories like that, because spotting a bargain or a deal was his life. Simplot was known as the potato king because his company invented a way to process French fries that caught on just a little bit with companies such as McDonalds. He was big in fertilizer, raising cattle, and funding the development of microchips. The latter proving that he never lost the business acumen that he gained back at that boarding house in Declo.

J.R. Simplot was Idaho’s first billionaire. In 2007 he was the 89th richest person in the United States, with a personal fortune estimated to be about $3.6 billion dollars. When he passed away in 2008 at age 99, Jack Simplot was the oldest billionaire on the Forbes 400 list.

J.R. Simplot in 1961. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

J.R. Simplot in 1961. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on January 24, 2020 04:00

January 23, 2020

Some Treasured Mugshots

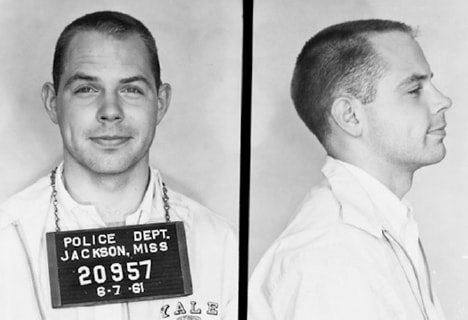

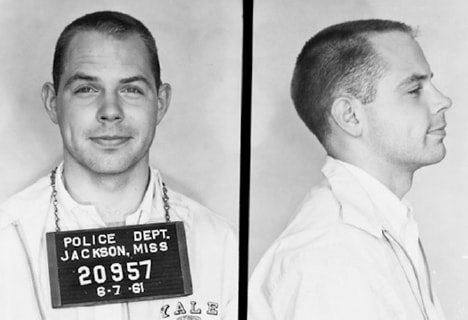

Some mugshots mean more than they would seem. Today we’re going to feature two men with strong Idaho ties who should be proud of their mugshots.

Edward W. Kale grew up mostly in Grangeville. Some sources say he was born in Idaho and some say it was Iowa. That Idaho/Iowa thing, again, perhaps. Kale attended the University of Idaho but graduated from the University of Denver. He taught at the American colleges in Athens, Greece and Istanbul, Turkey, for three years before coming back stateside to get a degree at Yale Divinity in 1965. He is an ordained Methodist minister who taught and served as a college chaplain for years in England and Germany before coming back to Idaho to teach at the University of Idaho in 1978. He taught and served as a college chaplain at the University of Texas, and the University of Minnesota. Retired from that calling he now runs a kayaking service in Minnesota. He was active in the anti-war and anti-apartheid movements, and in supporting human rights in Central America.

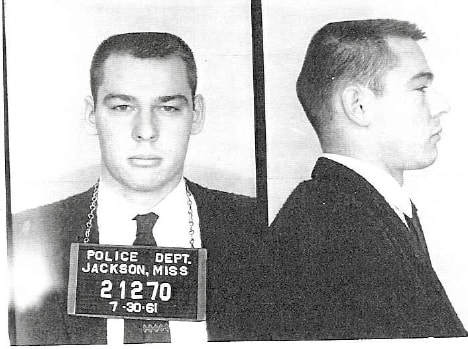

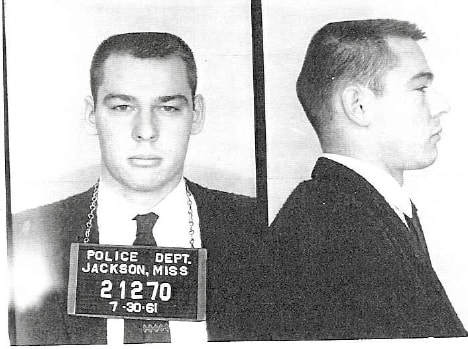

The second mugshot belongs to Max Pavesic. He grew up in California getting degrees from Los Angeles City College and UCLA before getting an MA and PhD from the University of Colorado. Pavesic taught anthropology at Idaho State University for 1967-1971 and Boise State University until his retirement in 2001. He had chaired the department of sociology, anthropology and criminal justice at BSU and was the recipient of many awards. Pavesic was an advisor to the Idaho Archeology Society and served as chair of the Idaho State Historical Society board of trustees. He lives today in Portland.

So, two academics with strong Idaho connections and mugshots in common. Why?

Both Edward W. Kale and Max Pavesic were arrested and jailed as Freedom Riders in 1961. The Freedom Riders risked their lives by taking public transportation as mixed-race riders that summer to spotlight local laws against it in the South. Discriminating against people based on the color of their skin was already against federal law, but many Southern jurisdiction flouted that and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had yet to publish rules against it.

Edward Kale’s bus ride through several Southern states was largely uneventful until June 7, 1961. When they rolled into Jackson, Mississippi, he and other Freedom Riders boldly ignored the bus terminal signs, whites going to the waiting room marked “colored waiting room” and blacks going through the doors to the “white waiting room.” He spent several weeks in the state penitentiary for his defiance.

Max Pavesic, along with 14 others, took a train from New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi on July 30, 1961. They were attempting to overwhelm the local jail system. When they got off the train they went into the “wrong” waiting rooms and were quickly arrested. He spent about a month in the penitentiary.

The Freedom Riders in the summer of ’61 drew nationwide attention to discrimination in the South. Their peaceful protests were often met with violence, sometimes with the KKK joining local police in confronting them. By November of that year the ICC issued a ruling reflecting earlier Supreme Court decisions against discrimination in public transportation. The Freedom Riders inspired thousands of others to take direct civil action in the civil rights movement.

Edward Kale in 1961.

Edward Kale in 1961.  Max Pavesic in 1961.

Max Pavesic in 1961.

Edward W. Kale grew up mostly in Grangeville. Some sources say he was born in Idaho and some say it was Iowa. That Idaho/Iowa thing, again, perhaps. Kale attended the University of Idaho but graduated from the University of Denver. He taught at the American colleges in Athens, Greece and Istanbul, Turkey, for three years before coming back stateside to get a degree at Yale Divinity in 1965. He is an ordained Methodist minister who taught and served as a college chaplain for years in England and Germany before coming back to Idaho to teach at the University of Idaho in 1978. He taught and served as a college chaplain at the University of Texas, and the University of Minnesota. Retired from that calling he now runs a kayaking service in Minnesota. He was active in the anti-war and anti-apartheid movements, and in supporting human rights in Central America.

The second mugshot belongs to Max Pavesic. He grew up in California getting degrees from Los Angeles City College and UCLA before getting an MA and PhD from the University of Colorado. Pavesic taught anthropology at Idaho State University for 1967-1971 and Boise State University until his retirement in 2001. He had chaired the department of sociology, anthropology and criminal justice at BSU and was the recipient of many awards. Pavesic was an advisor to the Idaho Archeology Society and served as chair of the Idaho State Historical Society board of trustees. He lives today in Portland.

So, two academics with strong Idaho connections and mugshots in common. Why?

Both Edward W. Kale and Max Pavesic were arrested and jailed as Freedom Riders in 1961. The Freedom Riders risked their lives by taking public transportation as mixed-race riders that summer to spotlight local laws against it in the South. Discriminating against people based on the color of their skin was already against federal law, but many Southern jurisdiction flouted that and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had yet to publish rules against it.

Edward Kale’s bus ride through several Southern states was largely uneventful until June 7, 1961. When they rolled into Jackson, Mississippi, he and other Freedom Riders boldly ignored the bus terminal signs, whites going to the waiting room marked “colored waiting room” and blacks going through the doors to the “white waiting room.” He spent several weeks in the state penitentiary for his defiance.

Max Pavesic, along with 14 others, took a train from New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi on July 30, 1961. They were attempting to overwhelm the local jail system. When they got off the train they went into the “wrong” waiting rooms and were quickly arrested. He spent about a month in the penitentiary.

The Freedom Riders in the summer of ’61 drew nationwide attention to discrimination in the South. Their peaceful protests were often met with violence, sometimes with the KKK joining local police in confronting them. By November of that year the ICC issued a ruling reflecting earlier Supreme Court decisions against discrimination in public transportation. The Freedom Riders inspired thousands of others to take direct civil action in the civil rights movement.

Edward Kale in 1961.

Edward Kale in 1961.  Max Pavesic in 1961.

Max Pavesic in 1961.

Published on January 23, 2020 04:00

January 22, 2020

Do you want fries with that? Tough.

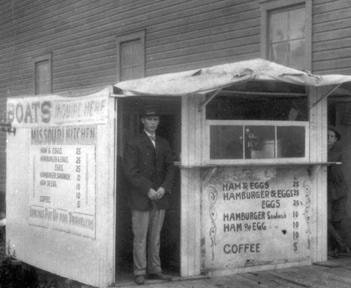

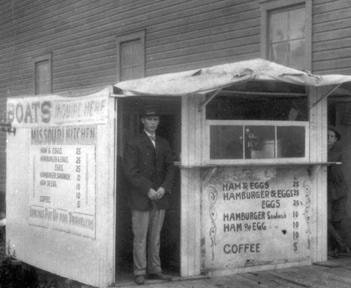

Hudson’s Hamburgers in Coeur d’Alene has been not selling fries with their hamburgers since 1907. And they do okay. You can get cheese on your hamburger, and you can order a pie for dessert. Just no fries.

Harley Hudson came to Coeur d’Alene from Brooklyn in 1905. The other Brooklyn. The one in Iowa. He sawed timber for a living for a couple of years, then thought the area could benefit from a good, basic burger. He built a rickety little stand out of canvas and boards and began selling hamburgers for a dime on the west end of the Idaho Hotel. He sold a lot of them. In 1910 he moved into a space next to the east end of the hotel that allowed him to have a counter and stools for a dozen customers.

When 1917 rolled around—the ten-year anniversary of Hudson’s Hamburgers—Harley had saved up enough money to buy a two-story brick building on the south side of Sherman Avenue, between Second and Third streets. He promptly named it the Hudson Building. The family operated the business from there until 1962 when they leased the spot to J.C. Penney and moved across the street to their present location, 207 E. Sherman Avenue.

Descendants of Harley Hudson still run the joint today. The menu is about the same as it was in 1907: plenty of burgers, no fries. They’ve been doing the burger thing so long and so well that there just isn’t much point in changing their business formulae. They’ve been named one of the top hamburger spots in the West by Sunset Magazine. The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and Gourmet Magazine have all featured Hudson’s.

If you’re a history buff—and you probably are, if you’re reading this—stop in and take a look at the framed photos on the walls of big steamers and smaller boats that once plied the nearby waters. Maybe order a hamburger while you’re there.

Harley Hudson came to Coeur d’Alene from Brooklyn in 1905. The other Brooklyn. The one in Iowa. He sawed timber for a living for a couple of years, then thought the area could benefit from a good, basic burger. He built a rickety little stand out of canvas and boards and began selling hamburgers for a dime on the west end of the Idaho Hotel. He sold a lot of them. In 1910 he moved into a space next to the east end of the hotel that allowed him to have a counter and stools for a dozen customers.

When 1917 rolled around—the ten-year anniversary of Hudson’s Hamburgers—Harley had saved up enough money to buy a two-story brick building on the south side of Sherman Avenue, between Second and Third streets. He promptly named it the Hudson Building. The family operated the business from there until 1962 when they leased the spot to J.C. Penney and moved across the street to their present location, 207 E. Sherman Avenue.

Descendants of Harley Hudson still run the joint today. The menu is about the same as it was in 1907: plenty of burgers, no fries. They’ve been doing the burger thing so long and so well that there just isn’t much point in changing their business formulae. They’ve been named one of the top hamburger spots in the West by Sunset Magazine. The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and Gourmet Magazine have all featured Hudson’s.

If you’re a history buff—and you probably are, if you’re reading this—stop in and take a look at the framed photos on the walls of big steamers and smaller boats that once plied the nearby waters. Maybe order a hamburger while you’re there.

Published on January 22, 2020 04:00

January 21, 2020

So Many Firsts

Louise Shadduck wore a lot of hats, figuratively, and not rarely her favorite cowboy hat. She wrote the book

Rodeo Idaho

! She also wrote

Andy Little, Idaho Sheep King

,

Doctors With Buggies, Snowshoes, and Planes

,

The House that Victor Built

and

At the Edge of the Ice

.* Mike Bullard wrote a book about her called

Lioness of Idaho

.*

Shadduck, born in Coeur d’Alene in 1915, started out as a journalist. She wrote first for The Spokesman Review, then her hometown paper, The Coeur d’Alene Press. It was while working for The Press that she got her first taste of politics, covering the Republican National Convention in 1944. Inspired, she founded the Kootenai County Young Republicans. Then, she served a dual role working as a journalist while serving as an intern in Senator Henry Dworshak’s Washington, DC office.

In 1946 Shadduck took a job with Idaho Governor Charles Robbins, serving first as a publicity assistant, then as his administrative assistant. She was the first female to serve as a governor’s administrative assistant in Idaho. It wouldn’t be her last first. During her stint in the governor’s office she wrote a freelance column for The Coeur d’Alene Press called “This and That.”

When Len B. Jordan followed Robbins as governor, he retained Shadduck in her administrative assistant position. Then, in 1952, Senator Dworshak talked her into moving back to DC. There she became friends with Dwight Eisenhower. She spoke at the Republican National Convention in a televised address in 1952 in support of Eisenhower.

Shadduck decided to dive into politics herself, running for Idaho’s First Congressional District seat against Democrat Gracie Pfost. She lost that race, but it was another first for her. The match was the first time two women ran against each other for a congressional seat in US history. She spoke again for Eisenhower at the 1956 Republican National Convention, but her political future was to be on the state level.

Governor Robert E. Smylie appointed Shadduck to head the Idaho Department of Commerce and Development in 1958, making her the first woman in the country to serve in a state cabinet position. She was instrumental in bringing the National Girl Scout Roundup and the World Boy Scout Jamboree to Farragut State Park in 1965 and 1967, respectively.

Following Smylie’s last term in office she went to work as an administrative assistant to Congressman Orval Hansen.

Shadduck was troubled by the rise of white supremacists in her home state. She lobbied for a change in the malicious harassment law. That law was critical in putting the Aryan Nations out of business.

In her spare time, Shadduck served as president of the National Federation of Press Women from 1971 to 1973.

Shadduck never married. Upon her death in 2008, her great niece was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying, “it was because no man could keep up with her.”

Louise Shadduck with a pair of boy scouts in a promotional photo for the 1967 National Boy Scouts Jamboree. From the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo file.

Louise Shadduck with a pair of boy scouts in a promotional photo for the 1967 National Boy Scouts Jamboree. From the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo file.

Shadduck, born in Coeur d’Alene in 1915, started out as a journalist. She wrote first for The Spokesman Review, then her hometown paper, The Coeur d’Alene Press. It was while working for The Press that she got her first taste of politics, covering the Republican National Convention in 1944. Inspired, she founded the Kootenai County Young Republicans. Then, she served a dual role working as a journalist while serving as an intern in Senator Henry Dworshak’s Washington, DC office.

In 1946 Shadduck took a job with Idaho Governor Charles Robbins, serving first as a publicity assistant, then as his administrative assistant. She was the first female to serve as a governor’s administrative assistant in Idaho. It wouldn’t be her last first. During her stint in the governor’s office she wrote a freelance column for The Coeur d’Alene Press called “This and That.”

When Len B. Jordan followed Robbins as governor, he retained Shadduck in her administrative assistant position. Then, in 1952, Senator Dworshak talked her into moving back to DC. There she became friends with Dwight Eisenhower. She spoke at the Republican National Convention in a televised address in 1952 in support of Eisenhower.

Shadduck decided to dive into politics herself, running for Idaho’s First Congressional District seat against Democrat Gracie Pfost. She lost that race, but it was another first for her. The match was the first time two women ran against each other for a congressional seat in US history. She spoke again for Eisenhower at the 1956 Republican National Convention, but her political future was to be on the state level.

Governor Robert E. Smylie appointed Shadduck to head the Idaho Department of Commerce and Development in 1958, making her the first woman in the country to serve in a state cabinet position. She was instrumental in bringing the National Girl Scout Roundup and the World Boy Scout Jamboree to Farragut State Park in 1965 and 1967, respectively.

Following Smylie’s last term in office she went to work as an administrative assistant to Congressman Orval Hansen.

Shadduck was troubled by the rise of white supremacists in her home state. She lobbied for a change in the malicious harassment law. That law was critical in putting the Aryan Nations out of business.

In her spare time, Shadduck served as president of the National Federation of Press Women from 1971 to 1973.

Shadduck never married. Upon her death in 2008, her great niece was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying, “it was because no man could keep up with her.”

Louise Shadduck with a pair of boy scouts in a promotional photo for the 1967 National Boy Scouts Jamboree. From the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo file.

Louise Shadduck with a pair of boy scouts in a promotional photo for the 1967 National Boy Scouts Jamboree. From the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo file.

Published on January 21, 2020 04:00

January 20, 2020

A Famous First Name

If you’ve been hanging around Idaho for a few decades paying a little attention to who did what, you’ve run across the name Bowler from time-to-time. There’s Bruce Bowler who was a pioneer conservationist and attorney who pioneered the field of environmental law in Idaho. Drich (short for Aldrich) Bowler was an artist and inventor who hosted the 13-part Idaho Centennial series, produced by Idaho Public Television, "Proceeding on Through a Beautiful Country: A Television History of Idaho." Ned Bowler was a speech/language professor at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

But this is a story about their brother, Holden. Holden was an athlete, a military man, and a business man. He held a state record for high school track in Idaho, retired as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve, ran a Denver ad agency, and taught environmental education. But it was his passion for singing that gave him a couple of interesting connections to noted contemporary figures.

While going to school at the University of Idaho in the early 1930s, Holden met Thomas Collins. They became good friends over the years, and Holden became godfather to Tom’s daughter Judy Collins, the well-known folksinger.

Singing took Holden to sea. He became the headline singer for a cruise line on a cruise to South America. He met a young man named Jerome who was staff on the ship. They became fast friends. The two toured the towns where the cruise ship stopped and shot the breeze. Jerome told Holden he was a writer. He liked Holden’s unusual first name and told him he would probably use it someday in a story.

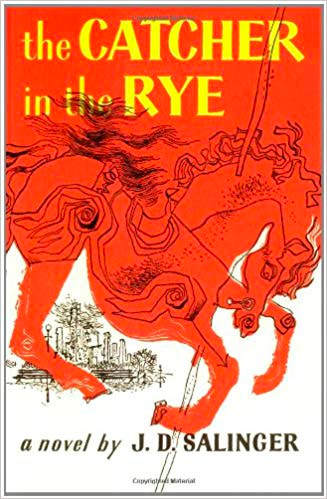

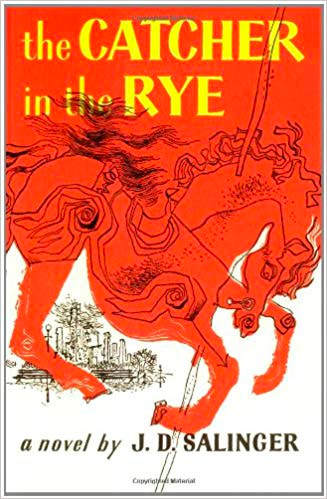

When Jerome got around to using Holden’s name, the writer was going just by his first initials, J.D. J.D. Salinger. The author of Catcher in the Rye* once wrote to Holden Bowler and said about the character who borrowed his name, “what you like about Holden (Caulfield) is taken from you, and what you don't like about him, I made up.”

Holden Bowler passed his passion for singing on to his daughter, Belinda Bowler, who I’ve heard called “Idaho folk music royalty.”

But this is a story about their brother, Holden. Holden was an athlete, a military man, and a business man. He held a state record for high school track in Idaho, retired as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve, ran a Denver ad agency, and taught environmental education. But it was his passion for singing that gave him a couple of interesting connections to noted contemporary figures.

While going to school at the University of Idaho in the early 1930s, Holden met Thomas Collins. They became good friends over the years, and Holden became godfather to Tom’s daughter Judy Collins, the well-known folksinger.

Singing took Holden to sea. He became the headline singer for a cruise line on a cruise to South America. He met a young man named Jerome who was staff on the ship. They became fast friends. The two toured the towns where the cruise ship stopped and shot the breeze. Jerome told Holden he was a writer. He liked Holden’s unusual first name and told him he would probably use it someday in a story.

When Jerome got around to using Holden’s name, the writer was going just by his first initials, J.D. J.D. Salinger. The author of Catcher in the Rye* once wrote to Holden Bowler and said about the character who borrowed his name, “what you like about Holden (Caulfield) is taken from you, and what you don't like about him, I made up.”

Holden Bowler passed his passion for singing on to his daughter, Belinda Bowler, who I’ve heard called “Idaho folk music royalty.”

Published on January 20, 2020 04:00

January 19, 2020

You Can't Roller Skate in a...

Belgian inventor John Joseph Merlin was a couple of centuries ahead of his time when he patented the first roller skate in 1760. His skates were just ice skates with rollers replacing the blade. He had basically invented the Rollerblade, not the roller skate. They weren’t popular because they were hard to steer and even harder to stop.

What we think of today as a roller skate came along in 1863, when James Plimpton of Massachusetts invented the familiar four-wheel design we know today. It was easier to turn because each wheel turned independently, allowing one to turn by putting one’s weight to one side of the skate. To say that they caught on would be an understatement. By 1871, even that outpost of civilization, Boise, had a skating rink.

Ads for the roller-skating rink at Templar Hall proclaimed that one could skate on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays during specified hours, with a “special assembly for the ladies” each of those days from 1 to 3 pm. After paying a quarter for admission you could pay another quarter to rent skates, if you didn’t have a pair of your own.

The rink pointed out that they had “the exclusive right for Plimpton’s Patent Roller Skates for Idaho Territory, same as used at the Pavilion Rink, San Francisco.”

In 1884 another rink opened in the city for “a multitude of excellent manipulators of the rollers” according to The Statesman. The rink was located in the newly converted opera house, and reportedly well managed. “In the evening the crowd was so large that the greatest precaution was necessary in order to preserve due regularity in the movements of skaters and Mr. P. F. Beal performed the duty of floor manager with commendable care and courtesy.”

A few mishaps were bound to occur. “The number of new beginners present was large and some falls were the result of too much haste and confidence.” Some were eager to take advantage of the newbies of a certain gender. “The young gentlemen who were masters of the rollers took the greatest imaginable delight in teaching young lady beginners the art and evidently the rink will be ‘all the rage’ this winter.”

But all was not perfection in the world of skating. A few weeks before statehood in 1890 The Statesman reported that “The walk to the Capitol from the corner of Seventh and Jefferson was taken possession of by boys with roller skates before it had become sufficiently hardened, and as a result it is very much creased and disfigured.” Cracks had also appeared in the concrete, perhaps likewise caused by unrestrained hooligan skaters. “Those cracks and creases will probably be an ‘eye-sore’ for years,” the paper concluded.

Today the wheels of skateboards are more often blamed for damage, real or imagined, but roller skates and enticing stretches of concrete are still with us.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

What we think of today as a roller skate came along in 1863, when James Plimpton of Massachusetts invented the familiar four-wheel design we know today. It was easier to turn because each wheel turned independently, allowing one to turn by putting one’s weight to one side of the skate. To say that they caught on would be an understatement. By 1871, even that outpost of civilization, Boise, had a skating rink.

Ads for the roller-skating rink at Templar Hall proclaimed that one could skate on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays during specified hours, with a “special assembly for the ladies” each of those days from 1 to 3 pm. After paying a quarter for admission you could pay another quarter to rent skates, if you didn’t have a pair of your own.

The rink pointed out that they had “the exclusive right for Plimpton’s Patent Roller Skates for Idaho Territory, same as used at the Pavilion Rink, San Francisco.”

In 1884 another rink opened in the city for “a multitude of excellent manipulators of the rollers” according to The Statesman. The rink was located in the newly converted opera house, and reportedly well managed. “In the evening the crowd was so large that the greatest precaution was necessary in order to preserve due regularity in the movements of skaters and Mr. P. F. Beal performed the duty of floor manager with commendable care and courtesy.”

A few mishaps were bound to occur. “The number of new beginners present was large and some falls were the result of too much haste and confidence.” Some were eager to take advantage of the newbies of a certain gender. “The young gentlemen who were masters of the rollers took the greatest imaginable delight in teaching young lady beginners the art and evidently the rink will be ‘all the rage’ this winter.”

But all was not perfection in the world of skating. A few weeks before statehood in 1890 The Statesman reported that “The walk to the Capitol from the corner of Seventh and Jefferson was taken possession of by boys with roller skates before it had become sufficiently hardened, and as a result it is very much creased and disfigured.” Cracks had also appeared in the concrete, perhaps likewise caused by unrestrained hooligan skaters. “Those cracks and creases will probably be an ‘eye-sore’ for years,” the paper concluded.

Today the wheels of skateboards are more often blamed for damage, real or imagined, but roller skates and enticing stretches of concrete are still with us.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

Published on January 19, 2020 04:00

January 18, 2020

Give Me an "I"

Time for a little audience participation. Get your cameras ready.

Have you ever given any thought to the big letter on the hills above your town? You know, the A above Arco, the B on Table Rock in Boise, the C on the hillside above Cambridge, etc.

According to Wikipedia, there are at least 35 letters on hillsides in Idaho, and maybe as many as 42. Most of them are the first letter of the town’s name, or a letter representing a local high school sports team. Franklin, the first town founded in Idaho Territory, has its big F, but above that are the numerals 1860 for the year it was founded (photo).

Pocatello had a big concrete I on Red Hill representing Idaho State University for many years. It was placed there in 1927. Travelers going south on I-15 knew it as a Pocatello landmark. But in 2014 it was removed because of the risk of a hillside collapse due to heavy erosion. The fear was that the concrete initial might come crashing down on trail users below.

In the book Quintessential Boise, An Architectural Journey*, by Charles Hummel, Tim Woodward, and others, they say the B on Table Rock above the Old Idaho Penitentiary, was placed there in 1931 by Ward Rolfe, Bob Krummes, Kenneth Robertson, and Simeon Coonrood, who were proud graduates of Boise High. As is the case with many such letters, the rocks often get a coat of paint to make them stand out.

Does your town have a letter? Post a picture in the comments section so we can all get a look. Do you have a story that goes along with the letter? An artifact of aliens, perhaps, or the site of your wedding proposal. Please share that, too.

Have you ever given any thought to the big letter on the hills above your town? You know, the A above Arco, the B on Table Rock in Boise, the C on the hillside above Cambridge, etc.

According to Wikipedia, there are at least 35 letters on hillsides in Idaho, and maybe as many as 42. Most of them are the first letter of the town’s name, or a letter representing a local high school sports team. Franklin, the first town founded in Idaho Territory, has its big F, but above that are the numerals 1860 for the year it was founded (photo).

Pocatello had a big concrete I on Red Hill representing Idaho State University for many years. It was placed there in 1927. Travelers going south on I-15 knew it as a Pocatello landmark. But in 2014 it was removed because of the risk of a hillside collapse due to heavy erosion. The fear was that the concrete initial might come crashing down on trail users below.

In the book Quintessential Boise, An Architectural Journey*, by Charles Hummel, Tim Woodward, and others, they say the B on Table Rock above the Old Idaho Penitentiary, was placed there in 1931 by Ward Rolfe, Bob Krummes, Kenneth Robertson, and Simeon Coonrood, who were proud graduates of Boise High. As is the case with many such letters, the rocks often get a coat of paint to make them stand out.

Does your town have a letter? Post a picture in the comments section so we can all get a look. Do you have a story that goes along with the letter? An artifact of aliens, perhaps, or the site of your wedding proposal. Please share that, too.

Published on January 18, 2020 04:00

January 17, 2020

Idaho's First (and Second) Flight

Idaho has a rich aviation history with solid connections to “Pappy” Boyington, Edward Pangborn, and Hawthorne Gray, to name a few daring pilots. The first contract air mail service in the United States was based in Boise with Varney Airlines. United Airlines claims Boise as its historical home, tracing its roots back to Varney.

But when was that first Idaho flight, the inception as it were of Idaho aviation history?

The Idaho Statesman declared, in an article on April 20, 1911, that Walter Brookins had launched into the air on “the first aeroplane flight ever made in the Gem state” the day before. This, in spite of the fact that the same paper had reported on October 16, 1910, that several flights had taken place above the fairgrounds in Lewiston, the last one ending in disaster.

Lewiston, still smarting today more than 150 years after losing the territorial capital, could be forgiven for being a little perturbed at this oversight.

James J. Ward of Chicago made the first Idaho flight on October 13, 1910. In Lewiston. His engine sputtered, causing him to land a little rougher than he’d hoped and destroying the front wheel of the Curtiss biplane. There were plenty of bicycle wheels in Lewiston, so that was easily replaced. He made several successful flights for the cheering crowd in the grandstand at the Lewiston-Clarkston fairgrounds.

His luck ran out, some would say, on October 14. His engine conked out when he was some 200 feet in the air. That was unlucky. But, luckily, Ward was able to jump free of the plane just as it crashed sustaining only minor injuries. The Idaho Statesman printed a dispatch from Lewiston that read, “The Curtiss biplane with which J.J. Ward of Chicago has been making daily flights at the fair, tonight lies a heap of junk on the banks of the Snake River, and that Ward himself is not in the morgue or at the hospital, is almost a miracle.”

Lewiston can also claim the first attempted flight in Idaho, though it was going to be just a glide. That came about on July 30, 1904, less than a year after the first successful flight of the Wright brothers. Captain Stewart V. Winslow, who during his working hours operated a dredge in the Snake River, tried to get into the air by pedaling a bicycle with wings over a cliff. He planned to glide across the river to the Washington side in triumph. He may have considered it bad luck when his front bicycle wheel collapsed before he could ride the contraption off the cliff. Luckily, he never did make a second try.

But what about that 1911 flight in Boise? It didn’t qualify as the first in the state, but it was the first in Boise, and it was accomplished by an aviation pioneer.

Walter Brookins, the first pilot trained by the Wright brothers, took to the air a few minutes after 5 pm on April 19, 1911 from the center field of the racetrack at the fairgrounds in Boise. Note that the fairgrounds were not located where they are today. They were roughly on the corner of Orchard and Fairview, thus the name of the latter street.

Promoters of the spectacle had cancelled the flight, allegedly because the weather had turned too cold for spectators. The many spectators who had shown up began to grumble and speculate that brisk winds were the real reason for the cancellation and casting aspersions on the pilot. When Brookins heard this he immediately rolled out his biplane and made preparations to meet the winds, which were described as gale force, head on.

One spectator was particularly interested in how Brookins would take to the Boise air. W.O. Kay, of Ogden, Utah, had followed the aviator to Boise, disappointed because he had not been able to take a ride in the Wright Biplane when Brookins had flown in Utah. Kay, who weighed 164 pounds, would have been too great a load for the plane to get into the air over Utah’s capital city. The air was too thin to keep both men aloft at Salt Lake’s elevation of 4,220 feet. Kay and Brookins both thought Boise’s 2,730-foot elevation would allow a passenger.

Without a hint of drama Brookins rolled along in the rough pasture for about 200 feet and rose steadily into the air. He would fly around the racetrack five times, a distance of about three miles, before an easy landing. He could not resist putting on a show for the crowd.

The Idaho Statesman described what happened after the pilot seemed to take an unplanned dip, then recover. “Shortly after thrilling the crowd with this feat he increased his speed as though to descend right into the mob. He shot down at a terrific rate, the terror-stricken people scattering right and left.”

He rose at the last moment and made another circuit of the track before landing. The flight had lasted about 12 minutes, securing Brookins place at the head of the line in Boise’s aviation history.

Brookins performed further feats in the days to come, took Kay on his promised airplane ride, and raced an automobile around the track. He was a sensation. His flights moved Idaho Lieutenant Governor Sweetser to present Walter Brookins with a commission as a colonel in the Idaho National Guard, making Idaho the first state to so honor Brookins for his contribution to aeronautics.

Brookins went on to establish numerous aviation records. Chancy as flying was in those early days, he was never seriously injured (a few broken ribs) while flying. He died in 1953 and is buried at the Portal of the Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation in Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery, Los Angeles. Walter Brookins, aviation pioneer, was the first to fly the Boise skies, though not the first to fly in Idaho.

Walter Brookins, aviation pioneer, was the first to fly the Boise skies, though not the first to fly in Idaho.

But when was that first Idaho flight, the inception as it were of Idaho aviation history?

The Idaho Statesman declared, in an article on April 20, 1911, that Walter Brookins had launched into the air on “the first aeroplane flight ever made in the Gem state” the day before. This, in spite of the fact that the same paper had reported on October 16, 1910, that several flights had taken place above the fairgrounds in Lewiston, the last one ending in disaster.

Lewiston, still smarting today more than 150 years after losing the territorial capital, could be forgiven for being a little perturbed at this oversight.

James J. Ward of Chicago made the first Idaho flight on October 13, 1910. In Lewiston. His engine sputtered, causing him to land a little rougher than he’d hoped and destroying the front wheel of the Curtiss biplane. There were plenty of bicycle wheels in Lewiston, so that was easily replaced. He made several successful flights for the cheering crowd in the grandstand at the Lewiston-Clarkston fairgrounds.

His luck ran out, some would say, on October 14. His engine conked out when he was some 200 feet in the air. That was unlucky. But, luckily, Ward was able to jump free of the plane just as it crashed sustaining only minor injuries. The Idaho Statesman printed a dispatch from Lewiston that read, “The Curtiss biplane with which J.J. Ward of Chicago has been making daily flights at the fair, tonight lies a heap of junk on the banks of the Snake River, and that Ward himself is not in the morgue or at the hospital, is almost a miracle.”

Lewiston can also claim the first attempted flight in Idaho, though it was going to be just a glide. That came about on July 30, 1904, less than a year after the first successful flight of the Wright brothers. Captain Stewart V. Winslow, who during his working hours operated a dredge in the Snake River, tried to get into the air by pedaling a bicycle with wings over a cliff. He planned to glide across the river to the Washington side in triumph. He may have considered it bad luck when his front bicycle wheel collapsed before he could ride the contraption off the cliff. Luckily, he never did make a second try.

But what about that 1911 flight in Boise? It didn’t qualify as the first in the state, but it was the first in Boise, and it was accomplished by an aviation pioneer.

Walter Brookins, the first pilot trained by the Wright brothers, took to the air a few minutes after 5 pm on April 19, 1911 from the center field of the racetrack at the fairgrounds in Boise. Note that the fairgrounds were not located where they are today. They were roughly on the corner of Orchard and Fairview, thus the name of the latter street.

Promoters of the spectacle had cancelled the flight, allegedly because the weather had turned too cold for spectators. The many spectators who had shown up began to grumble and speculate that brisk winds were the real reason for the cancellation and casting aspersions on the pilot. When Brookins heard this he immediately rolled out his biplane and made preparations to meet the winds, which were described as gale force, head on.

One spectator was particularly interested in how Brookins would take to the Boise air. W.O. Kay, of Ogden, Utah, had followed the aviator to Boise, disappointed because he had not been able to take a ride in the Wright Biplane when Brookins had flown in Utah. Kay, who weighed 164 pounds, would have been too great a load for the plane to get into the air over Utah’s capital city. The air was too thin to keep both men aloft at Salt Lake’s elevation of 4,220 feet. Kay and Brookins both thought Boise’s 2,730-foot elevation would allow a passenger.

Without a hint of drama Brookins rolled along in the rough pasture for about 200 feet and rose steadily into the air. He would fly around the racetrack five times, a distance of about three miles, before an easy landing. He could not resist putting on a show for the crowd.

The Idaho Statesman described what happened after the pilot seemed to take an unplanned dip, then recover. “Shortly after thrilling the crowd with this feat he increased his speed as though to descend right into the mob. He shot down at a terrific rate, the terror-stricken people scattering right and left.”

He rose at the last moment and made another circuit of the track before landing. The flight had lasted about 12 minutes, securing Brookins place at the head of the line in Boise’s aviation history.

Brookins performed further feats in the days to come, took Kay on his promised airplane ride, and raced an automobile around the track. He was a sensation. His flights moved Idaho Lieutenant Governor Sweetser to present Walter Brookins with a commission as a colonel in the Idaho National Guard, making Idaho the first state to so honor Brookins for his contribution to aeronautics.

Brookins went on to establish numerous aviation records. Chancy as flying was in those early days, he was never seriously injured (a few broken ribs) while flying. He died in 1953 and is buried at the Portal of the Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation in Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery, Los Angeles.

Walter Brookins, aviation pioneer, was the first to fly the Boise skies, though not the first to fly in Idaho.

Walter Brookins, aviation pioneer, was the first to fly the Boise skies, though not the first to fly in Idaho.

Published on January 17, 2020 04:00

January 16, 2020

Diamonds (and “Diamond Field”) Were a Girl’s Best Friend

First, let’s concede that there were at least a couple of women who went by the name of Diamond Tooth Lil. One, real name Honora Ornstein, was a vaudeville performer well-known in Klondike Gold Rush days. Her affectation of diamonds included much jewelry and several gold teeth studded with diamonds.

Idaho’s Diamond Tooth Lil was an entertainer and entrepreneur who bounced around the West from Silver City to San Francisco, spending significant time in Boise as a manager of rooming houses which were rumored to offer unadvertised recreational activities. Her birth name was Evelyn Fialla (some sources say Prado was her last name), and she was born in Austria-Hungary in about 1877. She married at least eight times, but the name she preferred to use was her first husband’s surname of Hildegard. Everyone else preferred Diamond Tooth Lil.

Lil loved to tell the story of her life to any reporter who would listen. She often told about her gold right front tooth with the diamond, about 1/3 carat, mounted in the center of it. She won that piece of art from a Reno dentist in a bet on a horse race in 1907. More than once she promised to leave the tooth and its diamond to the Idaho Children’s Home orphanage. What finally happened to it is open to speculation.

Diamond Tooth Lil’s stories were often about the love of her life, Diamond Field Jack. They spent time with each other over the years in Idaho and Nevada. She said he asked her to marry him many times, but she declined. They lost track of each other for 30 years, but reunited briefly at a Las Vegas casino in 1946, and in Los Angeles shortly before his death.

When Diamond Field Jack was struck by a cab in 1946 at age 84, it was Diamond Tooth Lil who alerted the Idaho Statesman. Before his death she reported that he had exonerated the taxi driver, saying, “I just wasn’t looking where I was going.”

She ran an auto court called the Depot Inn on the bench near the Boise Depot, and a hotel at 219 S. Ninth, among other Boise properties. She moved to Los Angeles to retire in 1943, but visited Boise regularly. In 1953 she sent photos and other items to the Boise Chamber of Commerce with a note, “just sending a little momento (sic), so you’ll not forget me.”

There’s little chance Diamond Tooth Lil will be forgotten. Mae West wrote a successful Broadway play called Diamond Lil in 1928, which was turned into a movie called She Done Him Wrong, and was revived on Broadway in 1949. Many say it was inspired by one Diamond Tooth Lil or the other, or perhaps the pair of them.

#diamontoothlil

Diamond Tooth Lil in 1947. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

Diamond Tooth Lil in 1947. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

Idaho’s Diamond Tooth Lil was an entertainer and entrepreneur who bounced around the West from Silver City to San Francisco, spending significant time in Boise as a manager of rooming houses which were rumored to offer unadvertised recreational activities. Her birth name was Evelyn Fialla (some sources say Prado was her last name), and she was born in Austria-Hungary in about 1877. She married at least eight times, but the name she preferred to use was her first husband’s surname of Hildegard. Everyone else preferred Diamond Tooth Lil.

Lil loved to tell the story of her life to any reporter who would listen. She often told about her gold right front tooth with the diamond, about 1/3 carat, mounted in the center of it. She won that piece of art from a Reno dentist in a bet on a horse race in 1907. More than once she promised to leave the tooth and its diamond to the Idaho Children’s Home orphanage. What finally happened to it is open to speculation.

Diamond Tooth Lil’s stories were often about the love of her life, Diamond Field Jack. They spent time with each other over the years in Idaho and Nevada. She said he asked her to marry him many times, but she declined. They lost track of each other for 30 years, but reunited briefly at a Las Vegas casino in 1946, and in Los Angeles shortly before his death.

When Diamond Field Jack was struck by a cab in 1946 at age 84, it was Diamond Tooth Lil who alerted the Idaho Statesman. Before his death she reported that he had exonerated the taxi driver, saying, “I just wasn’t looking where I was going.”

She ran an auto court called the Depot Inn on the bench near the Boise Depot, and a hotel at 219 S. Ninth, among other Boise properties. She moved to Los Angeles to retire in 1943, but visited Boise regularly. In 1953 she sent photos and other items to the Boise Chamber of Commerce with a note, “just sending a little momento (sic), so you’ll not forget me.”

There’s little chance Diamond Tooth Lil will be forgotten. Mae West wrote a successful Broadway play called Diamond Lil in 1928, which was turned into a movie called She Done Him Wrong, and was revived on Broadway in 1949. Many say it was inspired by one Diamond Tooth Lil or the other, or perhaps the pair of them.

#diamontoothlil

Diamond Tooth Lil in 1947. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

Diamond Tooth Lil in 1947. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

Published on January 16, 2020 04:00