Rick Just's Blog, page 177

December 16, 2019

Hemingway Butte

That beep, beep, beep you hear is the sound of me backing into this story. It’s about Hemingway Butte, which today is an off-highway vehicle play area managed by the Boise District Bureau of Land Management. It includes a popular trail system and steep hillsides where OHVs and motorbikes defy gravity for a few seconds courtesy of two-cycle engines.

Hemmingway Butte is about three miles southwest of Walter’s Ferry, which itself is about 15 miles south of Nampa. Beep, beep, beep.

Walters Ferry wasn’t always called that. It became Walter’s Ferry when Lewellyn R. Walter bought out his partner’s share of the ferry business in 1886. Previous owners had been John Fruit, George Blankenbecker, John Morgan, Leonard Fuqa, a Mr. Boon, Samuel Neeley, Perry Munday, Robert Duncan, and Reese Miles. But, beep, beep, we must back up to Munday for this story, because the drama took place when it was called Munday’s Ferry.

It was at Munday’s Ferry that the stage came thundering up from the south in August of 1878, its driver mortally wounded. Indians were chasing the stage and directing bullets at it. Munday and three soldiers set across the river toward the embattled stage coach, while two other soldier remained on the north side of the Snake to provide cover fire.

The soldiers and Indians exchanged fire for several minutes, according to a report in the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, while the ferry landed and the wounded stagecoach driver “quietly kept his seat, and when the boat touched the bank drove the team up the grade from the river and asked for water.”

Dr. W.W. McKay was dispatched from Boise to care for the driver. He made the dusty, 30-mile trip by buggy in two and a half hours, only to find when he got there that William Hemingway had breathed his last minutes before.

William Hemingway was the name of the stagecoach driver, and the aforementioned butte was named in his honor, as it was near there that the Indian attack began. Hemingway was buried in Silver City beside his wife and two children who had gone before.

#idahohistory #hemingwaybutte

Hemmingway Butte is about three miles southwest of Walter’s Ferry, which itself is about 15 miles south of Nampa. Beep, beep, beep.

Walters Ferry wasn’t always called that. It became Walter’s Ferry when Lewellyn R. Walter bought out his partner’s share of the ferry business in 1886. Previous owners had been John Fruit, George Blankenbecker, John Morgan, Leonard Fuqa, a Mr. Boon, Samuel Neeley, Perry Munday, Robert Duncan, and Reese Miles. But, beep, beep, we must back up to Munday for this story, because the drama took place when it was called Munday’s Ferry.

It was at Munday’s Ferry that the stage came thundering up from the south in August of 1878, its driver mortally wounded. Indians were chasing the stage and directing bullets at it. Munday and three soldiers set across the river toward the embattled stage coach, while two other soldier remained on the north side of the Snake to provide cover fire.

The soldiers and Indians exchanged fire for several minutes, according to a report in the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, while the ferry landed and the wounded stagecoach driver “quietly kept his seat, and when the boat touched the bank drove the team up the grade from the river and asked for water.”

Dr. W.W. McKay was dispatched from Boise to care for the driver. He made the dusty, 30-mile trip by buggy in two and a half hours, only to find when he got there that William Hemingway had breathed his last minutes before.

William Hemingway was the name of the stagecoach driver, and the aforementioned butte was named in his honor, as it was near there that the Indian attack began. Hemingway was buried in Silver City beside his wife and two children who had gone before.

#idahohistory #hemingwaybutte

Published on December 16, 2019 04:00

December 15, 2019

Blackfoot Newspaper History, Part III

This is the third in a three-part series the originally appeared as columns in The Morning News, Blackfoot's newspaper.

More than a half-dozen newspapers have called Blackfoot home, beginning back in 1880. There is an unbroken string, owner to owner, name to name, from The Idaho Republican to The Morning News.

Byrd Trego, who started The Idaho Republican in 1904, looms large in the history of Blackfoot’s newspapers. In previous posts I wrote about his gracious home, Sagehurst, and the time he was convicted then exonerated for a major crime.

Trego was the original Blackfoot booster. He liked what the town was, and he did everything he could to make it better, promoting infrastructure projects and beautification. He was the editor, publisher, and sole owner of The Idaho Republican, though he often acknowledged the help of the “silent editor,” his wife Susie, in the early years.

The Idaho Republican was a weekly for its first ten years. It became a semi-weekly, then in 1920, a tri-weekly. In 1927 the paper became a daily, changing its name to The Daily Bulletin. In 1930 it became Blackfoot’s only paper, absorbing The Bingham County News.

With the merger Trego had new partners and new names began to appear in print. C. A. Bottolfsen, who owned the weekly Arco Advertiser became the managing editor of the paper, while publishing the Arco paper at the same time. Bottolfsen left The Daily Bulletin in 1936 to enter politics. He served as a legislator, the speaker of the Idaho House of Representatives, and then was elected as governor in Idaho in 1939.

In 1940, Trego sold out to John Rider and E.H. Payson. He would continue to write for the paper occasionally for many years. W. R. Twining took over ownership in 1942. In 1947, Harold H. Smith, former publisher of The Northside News in Jerome took over the reins. That lasted into 1948 when Pete Kimball, a newspaperman from San Diego purchased The Daily Bulletin.

In 1954, former publisher Harold Smith, who had continued to live in Blackfoot after selling to Kimball, repurchased the paper. He ran it until 1957 when it was purchased by Drury Brown, who changed the name of the paper to The Blackfoot News.

I owe thanks to Drury Brown who compiled a history of Blackfoot’s newspapers, from which much of this information comes. His son, Mark Brown, became publisher in the 1970s, as I remember. And if I’m starting to rely on my memory rather than archives, it’s probably time to end this sketch of Blackfoot’s newspaper history.

The Idaho Republican building was constructed by Byrd Trego, publisher of the newspaper. It was designed so that the Linotype operator, reporter, secretary, and editor could be seen through the large windows from the sidewalk. Trego wanted the paper to be open to the community. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places and now houses the Blackfoot office of Raymond James.

The Idaho Republican building was constructed by Byrd Trego, publisher of the newspaper. It was designed so that the Linotype operator, reporter, secretary, and editor could be seen through the large windows from the sidewalk. Trego wanted the paper to be open to the community. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places and now houses the Blackfoot office of Raymond James.

More than a half-dozen newspapers have called Blackfoot home, beginning back in 1880. There is an unbroken string, owner to owner, name to name, from The Idaho Republican to The Morning News.

Byrd Trego, who started The Idaho Republican in 1904, looms large in the history of Blackfoot’s newspapers. In previous posts I wrote about his gracious home, Sagehurst, and the time he was convicted then exonerated for a major crime.

Trego was the original Blackfoot booster. He liked what the town was, and he did everything he could to make it better, promoting infrastructure projects and beautification. He was the editor, publisher, and sole owner of The Idaho Republican, though he often acknowledged the help of the “silent editor,” his wife Susie, in the early years.

The Idaho Republican was a weekly for its first ten years. It became a semi-weekly, then in 1920, a tri-weekly. In 1927 the paper became a daily, changing its name to The Daily Bulletin. In 1930 it became Blackfoot’s only paper, absorbing The Bingham County News.

With the merger Trego had new partners and new names began to appear in print. C. A. Bottolfsen, who owned the weekly Arco Advertiser became the managing editor of the paper, while publishing the Arco paper at the same time. Bottolfsen left The Daily Bulletin in 1936 to enter politics. He served as a legislator, the speaker of the Idaho House of Representatives, and then was elected as governor in Idaho in 1939.

In 1940, Trego sold out to John Rider and E.H. Payson. He would continue to write for the paper occasionally for many years. W. R. Twining took over ownership in 1942. In 1947, Harold H. Smith, former publisher of The Northside News in Jerome took over the reins. That lasted into 1948 when Pete Kimball, a newspaperman from San Diego purchased The Daily Bulletin.

In 1954, former publisher Harold Smith, who had continued to live in Blackfoot after selling to Kimball, repurchased the paper. He ran it until 1957 when it was purchased by Drury Brown, who changed the name of the paper to The Blackfoot News.

I owe thanks to Drury Brown who compiled a history of Blackfoot’s newspapers, from which much of this information comes. His son, Mark Brown, became publisher in the 1970s, as I remember. And if I’m starting to rely on my memory rather than archives, it’s probably time to end this sketch of Blackfoot’s newspaper history.

The Idaho Republican building was constructed by Byrd Trego, publisher of the newspaper. It was designed so that the Linotype operator, reporter, secretary, and editor could be seen through the large windows from the sidewalk. Trego wanted the paper to be open to the community. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places and now houses the Blackfoot office of Raymond James.

The Idaho Republican building was constructed by Byrd Trego, publisher of the newspaper. It was designed so that the Linotype operator, reporter, secretary, and editor could be seen through the large windows from the sidewalk. Trego wanted the paper to be open to the community. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places and now houses the Blackfoot office of Raymond James.

Published on December 15, 2019 04:00

December 14, 2019

Blackfoot Newspaper History, Part II

I write occasional columns for The Morning News in Blackfoot. Yesterday's post, this one, and tomorrow's post originally appeared as columns in The News.

I was up to 1907 in telling the history of Blackfoot’s newspapers in my last post. That was when Karl Brown began publishing The Blackfoot Optimist. It was not surprising to me that my great aunt, Agnes Just Reid, was featured in that paper as the reporter from Presto, or that they often published one of her poems. I was surprised, though, to eventually see her name listed as one of the owners of the newspaper. She and other investors, including William M. Dooley, who became editor, purchased the Optimist from founder Karl Brown in 1913. Dooley had previously been with The Shelley Pioneer.

Newspaper owners are sometimes wealthy nowadays, but it is a risky business. Papers consolidate, reorganize, and go broke. That was true in the early part of the Twentieth Century as well. The Blackfoot Optimist, which became The Bingham County News in 1918, struggled along until 1920 when the paper went bankrupt. That wasn’t the end of it, though. William S. Parkhurst, from Richfield, Idaho bought its assets at a sheriff’s auction. In 1921 it changed hands twice, ending up with Raymond Ludi, who ran it until August, 1930 when it was absorbed by The Idaho Republican, which you may recall was the paper started by Byrd Trego in 1904.

The Idaho Republican and its successors would ultimately be the major paper in the Blackfoot market. The Blackfoot Optimist and The Bingham County News would not be its only rivals, though.

On July 2, 1913, Edgar A. Cooke decided that “the time (was) ripe for the establishment of a daily paper in Blackfoot.” For a subscription price of 50 cents a week you could have The Evening Courier delivered to your door six days a week. The paper was likely undercapitalized. The January 28, 1914 issue announced that The Evening Courier had been placed in receivership. It struggled along under receivership for another year before folding in 1915.

Another paper, The Daily Bingham County News gave it a go starting in July 1920. Few issues of that one remain. It was still publishing in March of 1921 but probably disappeared shortly thereafter.

Tomorrow, we’ll take a closer look at The Idaho Republican and its successors, which include The Morning News.

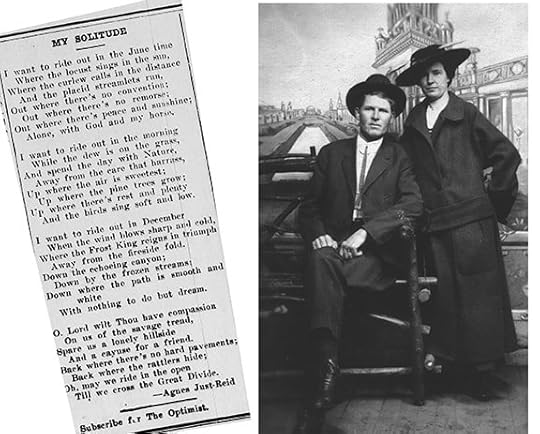

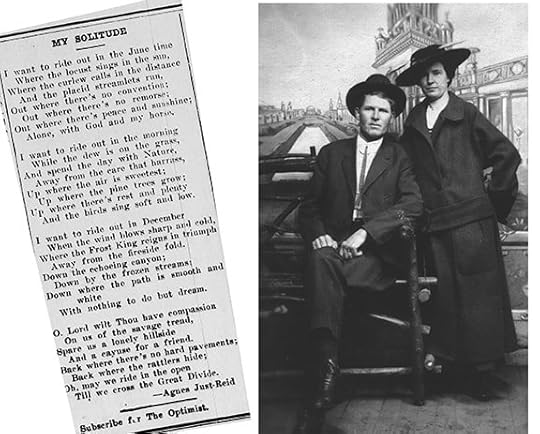

Agnes Just Reid wrote for at least a couple of the early Blackfoot papers and was one of the owners of The Blackfoot Optimist for a few years. A clipping of a poem she wrote for The Optimist in 1916 is on the left. Agnes and her husband Robert Reid are on the right in a photo taken that same year.

Agnes Just Reid wrote for at least a couple of the early Blackfoot papers and was one of the owners of The Blackfoot Optimist for a few years. A clipping of a poem she wrote for The Optimist in 1916 is on the left. Agnes and her husband Robert Reid are on the right in a photo taken that same year.

I was up to 1907 in telling the history of Blackfoot’s newspapers in my last post. That was when Karl Brown began publishing The Blackfoot Optimist. It was not surprising to me that my great aunt, Agnes Just Reid, was featured in that paper as the reporter from Presto, or that they often published one of her poems. I was surprised, though, to eventually see her name listed as one of the owners of the newspaper. She and other investors, including William M. Dooley, who became editor, purchased the Optimist from founder Karl Brown in 1913. Dooley had previously been with The Shelley Pioneer.

Newspaper owners are sometimes wealthy nowadays, but it is a risky business. Papers consolidate, reorganize, and go broke. That was true in the early part of the Twentieth Century as well. The Blackfoot Optimist, which became The Bingham County News in 1918, struggled along until 1920 when the paper went bankrupt. That wasn’t the end of it, though. William S. Parkhurst, from Richfield, Idaho bought its assets at a sheriff’s auction. In 1921 it changed hands twice, ending up with Raymond Ludi, who ran it until August, 1930 when it was absorbed by The Idaho Republican, which you may recall was the paper started by Byrd Trego in 1904.

The Idaho Republican and its successors would ultimately be the major paper in the Blackfoot market. The Blackfoot Optimist and The Bingham County News would not be its only rivals, though.

On July 2, 1913, Edgar A. Cooke decided that “the time (was) ripe for the establishment of a daily paper in Blackfoot.” For a subscription price of 50 cents a week you could have The Evening Courier delivered to your door six days a week. The paper was likely undercapitalized. The January 28, 1914 issue announced that The Evening Courier had been placed in receivership. It struggled along under receivership for another year before folding in 1915.

Another paper, The Daily Bingham County News gave it a go starting in July 1920. Few issues of that one remain. It was still publishing in March of 1921 but probably disappeared shortly thereafter.

Tomorrow, we’ll take a closer look at The Idaho Republican and its successors, which include The Morning News.

Agnes Just Reid wrote for at least a couple of the early Blackfoot papers and was one of the owners of The Blackfoot Optimist for a few years. A clipping of a poem she wrote for The Optimist in 1916 is on the left. Agnes and her husband Robert Reid are on the right in a photo taken that same year.

Agnes Just Reid wrote for at least a couple of the early Blackfoot papers and was one of the owners of The Blackfoot Optimist for a few years. A clipping of a poem she wrote for The Optimist in 1916 is on the left. Agnes and her husband Robert Reid are on the right in a photo taken that same year.

Published on December 14, 2019 04:00

December 13, 2019

Blackfoot's Newspaper History, Part I

I write occasional columns for The Morning News in Blackfoot. This post originally appeared there, as did the post you'll see tomorrow and the next day.

Newspapers have long been an important part of any community. In the community of Blackfoot, the history of newspapers goes back to 1880 when William E. Wheeler published the first newspaper in eastern Idaho. It was called The Idaho Register when it first came off the press on July 10. Blackfoot had a couple of general stores, two banks, a lumber yard, several eating establishments, a railroad station, a meat market, and five saloons when the offices of The Idaho Register were added to the list.

After just a few issues the paper’s masthead was changed to read The Blackfoot Register, to better reflect its location. Subscriptions ran $3 per year.

The old real estate saw, location, location, location, was just as true in the 1880s as it is today. Publisher Wheeler was a savvy man who kept his eye on business opportunities and in 1884 he determined that opportunities were popping up more often in Eagle Rock. The railroad headquarters had moved to that tiny town, so Wheeler decided he’d do the same. The last issue of The Blackfoot Register rolled off the press on March 22, 1884. Wheeler changed the name back to the Idaho Register. Eventually the paper’s name changed to The Post Register, which still publishes today in the town that changed its name to Idaho Falls.

So, Blackfoot was without a newspaper. It would remain so for the next three years.

In 1887, the Jones family started The Idaho News in Blackfoot. Colonel J.W. Jones, then Norman Jones, then Percy Jones (his sons) were listed one after another as publishers of the paper in the first few weeks of its existence. In 1891 the masthead would change to The Blackfoot News.

In the beginning the paper was published weekly in a seven-column, four-page format. That changed to an eight-page, six-column format in 1888.

Newspapers of that time were often unabashedly partisan. The Blackfoot News was a Democratic newspaper. The paper served the town until 1901 when Percy Jones stopped publishing it, with little evidence of the reason for its demise. He continued to run a printing shop for a few years.

In 1904 the publisher of The Mackay Telegraph noticed that the town of Blackfoot was without a paper. Byrd Trego came on the scene with The Idaho Republican. And, yes, it was a Republican paper, though Trego claimed it was “above petty partisanship.”

In 1907, The Blackfoot Optimist began publishing in direct competition with The Idaho Republican. Karl P. Brown was the publisher, though his life up to that point would not have made his choice of careers obvious. Born in Ohio he left home at 14 to find adventure in the West. He was a cattle rancher in Montana before moving to Blackfoot to work as a canal builder. When the canal was built, he suddenly turned into a newspaper publisher.

In doing research on Blackfoot papers it was at this point I found a surprising connection to publishing history that I did not know I had. I’ll pick up with that story tomorrow. Early Blackfoot newspaper mastheads, The Idaho News (1887-1894), The Blackfoot News (1891-1902), The Idaho Republican (1904-1932), and The Bingham County News (1918-1930.

Early Blackfoot newspaper mastheads, The Idaho News (1887-1894), The Blackfoot News (1891-1902), The Idaho Republican (1904-1932), and The Bingham County News (1918-1930.

Newspapers have long been an important part of any community. In the community of Blackfoot, the history of newspapers goes back to 1880 when William E. Wheeler published the first newspaper in eastern Idaho. It was called The Idaho Register when it first came off the press on July 10. Blackfoot had a couple of general stores, two banks, a lumber yard, several eating establishments, a railroad station, a meat market, and five saloons when the offices of The Idaho Register were added to the list.

After just a few issues the paper’s masthead was changed to read The Blackfoot Register, to better reflect its location. Subscriptions ran $3 per year.

The old real estate saw, location, location, location, was just as true in the 1880s as it is today. Publisher Wheeler was a savvy man who kept his eye on business opportunities and in 1884 he determined that opportunities were popping up more often in Eagle Rock. The railroad headquarters had moved to that tiny town, so Wheeler decided he’d do the same. The last issue of The Blackfoot Register rolled off the press on March 22, 1884. Wheeler changed the name back to the Idaho Register. Eventually the paper’s name changed to The Post Register, which still publishes today in the town that changed its name to Idaho Falls.

So, Blackfoot was without a newspaper. It would remain so for the next three years.

In 1887, the Jones family started The Idaho News in Blackfoot. Colonel J.W. Jones, then Norman Jones, then Percy Jones (his sons) were listed one after another as publishers of the paper in the first few weeks of its existence. In 1891 the masthead would change to The Blackfoot News.

In the beginning the paper was published weekly in a seven-column, four-page format. That changed to an eight-page, six-column format in 1888.

Newspapers of that time were often unabashedly partisan. The Blackfoot News was a Democratic newspaper. The paper served the town until 1901 when Percy Jones stopped publishing it, with little evidence of the reason for its demise. He continued to run a printing shop for a few years.

In 1904 the publisher of The Mackay Telegraph noticed that the town of Blackfoot was without a paper. Byrd Trego came on the scene with The Idaho Republican. And, yes, it was a Republican paper, though Trego claimed it was “above petty partisanship.”

In 1907, The Blackfoot Optimist began publishing in direct competition with The Idaho Republican. Karl P. Brown was the publisher, though his life up to that point would not have made his choice of careers obvious. Born in Ohio he left home at 14 to find adventure in the West. He was a cattle rancher in Montana before moving to Blackfoot to work as a canal builder. When the canal was built, he suddenly turned into a newspaper publisher.

In doing research on Blackfoot papers it was at this point I found a surprising connection to publishing history that I did not know I had. I’ll pick up with that story tomorrow.

Early Blackfoot newspaper mastheads, The Idaho News (1887-1894), The Blackfoot News (1891-1902), The Idaho Republican (1904-1932), and The Bingham County News (1918-1930.

Early Blackfoot newspaper mastheads, The Idaho News (1887-1894), The Blackfoot News (1891-1902), The Idaho Republican (1904-1932), and The Bingham County News (1918-1930.

Published on December 13, 2019 04:00

December 12, 2019

Oakley Stone

If you’ve seen a few fireplaces in Idaho, you’ve likely seen Oakley Stone. Beginning in the late 1940s the rock mined nearly Oakley, Idaho in the Albion Mountains became a popular building material for entryways, home veneers, and fireplaces. Geologists know it as micaceous quartzite or Idaho quartzite. Oakley Stone is a trade name.

Oakley stone is popular in the U.S., Canada, and even in Europe, because of its range of colors, from silver to gold and everything in between, but also because it is efficient. It can be split much thinner than competing rock from other quarries. A ton of Oakley Stone can cover 250 to 300 feet, while a ton of other stone veneers can cover 60 feet or less.

Oakley Stone was formed over the ages when layers of clay alternating with layers rich in quartz, compressed together. According to Terry Maley’s book, Exploring Idaho Geology , the alternating quartz-rich layers were flattened by the pressure so that the porosity of the material was removed and the quartz grains formed an interlocking mosaic.

The quarries for the stone are about halfway up Middle Mountain where they can dig through a shallow layer of dirt to access the tilted layers of sedimentary rock. It’s mostly hand work, chiseling along the front edge of the rock to break away plates as thin as a quarter inch and up to 4 inches thick. The plates can be as big as eight feet in diameter, but are usually broken into much smaller pieces. Once on site, the stone is easy to work and shape.

Frank Lloyd Wright specified the stone for the interior and exterior of Teater’s Knoll, near Hagerman. The home was built for artist Archie Teater and is the only one in Idaho designed for a particular site by the famous architect. The photo, courtesy of Henry Whiting, shows Kent Hale’s exterior rock work on the building.

Oakley stone is popular in the U.S., Canada, and even in Europe, because of its range of colors, from silver to gold and everything in between, but also because it is efficient. It can be split much thinner than competing rock from other quarries. A ton of Oakley Stone can cover 250 to 300 feet, while a ton of other stone veneers can cover 60 feet or less.

Oakley Stone was formed over the ages when layers of clay alternating with layers rich in quartz, compressed together. According to Terry Maley’s book, Exploring Idaho Geology , the alternating quartz-rich layers were flattened by the pressure so that the porosity of the material was removed and the quartz grains formed an interlocking mosaic.

The quarries for the stone are about halfway up Middle Mountain where they can dig through a shallow layer of dirt to access the tilted layers of sedimentary rock. It’s mostly hand work, chiseling along the front edge of the rock to break away plates as thin as a quarter inch and up to 4 inches thick. The plates can be as big as eight feet in diameter, but are usually broken into much smaller pieces. Once on site, the stone is easy to work and shape.

Frank Lloyd Wright specified the stone for the interior and exterior of Teater’s Knoll, near Hagerman. The home was built for artist Archie Teater and is the only one in Idaho designed for a particular site by the famous architect. The photo, courtesy of Henry Whiting, shows Kent Hale’s exterior rock work on the building.

Published on December 12, 2019 04:00

December 11, 2019

Governor Dies a Pauper

George Shoup is celebrated as Idaho’s first governor. He was also the state’s last territorial governor and one of its first senators. Setting aside some disturbing Shoup history, let’s take a minute to examine his term as the state’s first governor. Well, not examine it, exactly, but measure it. George Shoup was the governor of the State of Idaho for 79 days. As the territorial governor he had agreed to stay on as the state’s governor only with the understanding that he would soon be a US senator, selected in those days by state legislatures. Shoup hand-picked his lieutenant governor knowing full well the man would be filling his gubernatorial shoes when he packed up for Washington, DC.

We don’t hear much about Norman B. Willey, Idaho’s second governor. That’s too bad, because it was really on his watch that most of the details of transition from territory to state took place. It was during his term that state agencies were set up and Idaho got its state seal. He served from December 18, 1890 to January 2, 1893. His political career, which included a term on the Idaho County school board, stints as an Idaho County commissioner and county treasurer, and several terms as a territorial legislator, came to an end when he did not win his party’s nomination for a second term as governor.

Willey had come to Idaho as a miner, and he left the state to become a mine superintendent in California. Things went downhill for him from there. He suffered a string of setbacks. Hearing of his financial situation, the Legislature appropriated $1200 to send to him as something of retirement gift. Then he fell from the public conscious until the headlines read “Former Governor Dies as a Pauper.”

Governor Willey had passed away in a Kansas City poor house after dropping out of sight for a number of years. To add a probably unintentional sting to his ignominious end, the Blackfoot Republican misspelled Norman B. Willey’s name in the announcement of his death. He became “Normal” B. Willey.

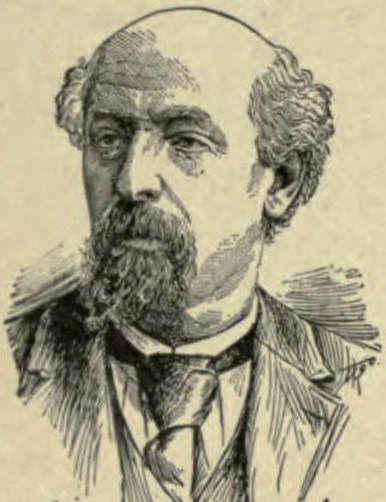

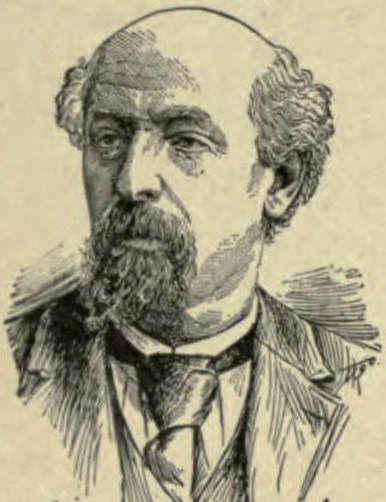

Idaho's second state governor, Norman B. Willey.

Idaho's second state governor, Norman B. Willey.

We don’t hear much about Norman B. Willey, Idaho’s second governor. That’s too bad, because it was really on his watch that most of the details of transition from territory to state took place. It was during his term that state agencies were set up and Idaho got its state seal. He served from December 18, 1890 to January 2, 1893. His political career, which included a term on the Idaho County school board, stints as an Idaho County commissioner and county treasurer, and several terms as a territorial legislator, came to an end when he did not win his party’s nomination for a second term as governor.

Willey had come to Idaho as a miner, and he left the state to become a mine superintendent in California. Things went downhill for him from there. He suffered a string of setbacks. Hearing of his financial situation, the Legislature appropriated $1200 to send to him as something of retirement gift. Then he fell from the public conscious until the headlines read “Former Governor Dies as a Pauper.”

Governor Willey had passed away in a Kansas City poor house after dropping out of sight for a number of years. To add a probably unintentional sting to his ignominious end, the Blackfoot Republican misspelled Norman B. Willey’s name in the announcement of his death. He became “Normal” B. Willey.

Idaho's second state governor, Norman B. Willey.

Idaho's second state governor, Norman B. Willey.

Published on December 11, 2019 04:00

December 10, 2019

McConnel Island

If you do a Google search for McConnel Island, you’ll come up with a couple of near matches, one for the McConnel Islands, plural, near Antarctica, and one for McConnell Island (note the second L) in the San Jaun Islands in Washington State.

If you’re looking for McConnel Island in Idaho, you’ll have to dig a little deeper. Ask around when you’re in Parma.

In the early days of settlement in that area the Boise River formed a delta, with two channels, one to the north and one to the south, forming a 4000-acre island. In 1865, David McConnel claimed land on the island and built a home there as a squatter. In 1879 he applied for and received a homestead claim of an additional 160 acres, bringing his ranch to about 500 acres. Other families, including that of David’s brother, Ben, lived there, and it even had a McConnel Island School.

David McConnel had come West in 1862 with a large Oregon Trail wagon train. He acted as a scout for that train. McConnel had 11 siblings, 10 brothers and a sister. Eight of his brothers followed him to the Boise Valley from their home in Iowa.

McConnel was a vigilante. That word has a negative note to it today, but it was a point of pride for him. It was the beginning of law and order in the area. In writing about his grandfather, Carl Isenberg recalled McConnel saying that “until the committee was formed and operated on several of the rustlers, murderers, etc., no one could feel secure, but that after a few examples, property and individual safety was secure.”

The island became McConnel Island because of David McConnel’s association with it. It ceased being an island when the Ross Fill was built to block off the southern channel of the river to help solve a frequent flooding problem.

Thanks to Merv McConnel for supplying much of the information used for this story.

If you’re looking for McConnel Island in Idaho, you’ll have to dig a little deeper. Ask around when you’re in Parma.

In the early days of settlement in that area the Boise River formed a delta, with two channels, one to the north and one to the south, forming a 4000-acre island. In 1865, David McConnel claimed land on the island and built a home there as a squatter. In 1879 he applied for and received a homestead claim of an additional 160 acres, bringing his ranch to about 500 acres. Other families, including that of David’s brother, Ben, lived there, and it even had a McConnel Island School.

David McConnel had come West in 1862 with a large Oregon Trail wagon train. He acted as a scout for that train. McConnel had 11 siblings, 10 brothers and a sister. Eight of his brothers followed him to the Boise Valley from their home in Iowa.

McConnel was a vigilante. That word has a negative note to it today, but it was a point of pride for him. It was the beginning of law and order in the area. In writing about his grandfather, Carl Isenberg recalled McConnel saying that “until the committee was formed and operated on several of the rustlers, murderers, etc., no one could feel secure, but that after a few examples, property and individual safety was secure.”

The island became McConnel Island because of David McConnel’s association with it. It ceased being an island when the Ross Fill was built to block off the southern channel of the river to help solve a frequent flooding problem.

Thanks to Merv McConnel for supplying much of the information used for this story.

Published on December 10, 2019 04:00

December 9, 2019

Media Man Marty

Radio is simultaneously one of the most ephemeral and longest lasting activities humans have come up with. It’s gone the instant it’s created, yet it lives on speeding through space infinitely.

Whoa! Who asked for a philosophy lecture? All I really want to do is write a little history column about a man who was a broadcasting institution in the Treasure Valley for nearly 40 years. Others have been on the air longer. Tom Scott and Paul J. Schneider come to mind, but there are few who played more roles in broadcasting than Marty Holtman.

Holtman began in 1961 at KBOI television and drifted over to KBOI radio shortly after. He worked most of his career for one or the other and often both.

“I did a kid’s show on TV, then walked across the hall and did a DJ show,” Holtman said. “Then I’d come back to the television side and sit in the director’s chair for the news, then hop up to do the weather, then slip back to the booth to direct.”

Holtman was the radio morning man for years before Dunn and Schneider started their long partnership on KBOI, getting up at 4:15 am every day for the “Yawn Patrol.” His hats included news anchor, DJ, weatherman, documentary maker, kid show host, director, music director, producer, writer, telethon host, and Claude Gloom, horrific host of movie nights on Channel 2.

As “Gloom” he wore a fright wig, heavy makeup—including a dangling eyeball—and introduced the segment by rising out of a coffin. He started a fan club called the “Dracula Deadbeats.” Young viewers wanted to meet this Claude Gloom character so much they arrived in throngs at the Channel 2 studios while he was on the air and banged on the doors. The station had to call the police. The teenage reaction to the show did not go unnoticed by parents. Someone worked up a petition asking the station to take the show off the air because it was keeping kids up too late on Friday nights. They gathered 8,000 signatures. After airing the program for eight months, the station finally dropped it.

As a TV weatherman in the early days, Holtman had none of the computer-generated graphics we’re used to seeing today. He had magnetic sun symbols, clouds, rain, etc., that he slapped on a metal map. He wrote in temperatures with a marker having memorized them before the red light on the studio camera came on. Commercials were recorded on film, which was prone to breaking. Holtman was always ready with something to say about the weather elsewhere in the country if a film broke and he had to fill time.

Some of the same technical issues, such as breaking tape, plagued him on the radio side. Holtman was always prepared, planning his morning shows a day ahead of time, writing himself scripts and jokes to read between records. He played mostly top 40 tunes, though he’d throw in a polka at least once a day to keep listeners on their toes. In the 60s he was forbidden to play “race records” as they were sometimes called. That meant no Motown, which he personally loved.

From the late 70s until he retired in 1999, Marty Holtman moved full-time to television. He reported, did local segments that aired during the CBS Morning Show, and kept the Treasure Valley informed about the weather. He also started a promotion that became an institution on Channel 2, Marty’s Santa Express. He took children from the Mountain States Tumor Institute on Christmas adventures, often to Hawaii, and at least once to North Pole, Alaska. He, along with producer Mark Montgomery and cameraman Clyn Richards, received a regional Emmy for that in 1989. In 2000, Marty Holtman received the Silver Circle Award for lifetime achievement from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. Marty Holtman during his early days as a weatherman.

Marty Holtman during his early days as a weatherman.  Marty Holtman in 2019 with the Emmy he won for Marty’s Santa Express.

Marty Holtman in 2019 with the Emmy he won for Marty’s Santa Express.

Whoa! Who asked for a philosophy lecture? All I really want to do is write a little history column about a man who was a broadcasting institution in the Treasure Valley for nearly 40 years. Others have been on the air longer. Tom Scott and Paul J. Schneider come to mind, but there are few who played more roles in broadcasting than Marty Holtman.

Holtman began in 1961 at KBOI television and drifted over to KBOI radio shortly after. He worked most of his career for one or the other and often both.

“I did a kid’s show on TV, then walked across the hall and did a DJ show,” Holtman said. “Then I’d come back to the television side and sit in the director’s chair for the news, then hop up to do the weather, then slip back to the booth to direct.”

Holtman was the radio morning man for years before Dunn and Schneider started their long partnership on KBOI, getting up at 4:15 am every day for the “Yawn Patrol.” His hats included news anchor, DJ, weatherman, documentary maker, kid show host, director, music director, producer, writer, telethon host, and Claude Gloom, horrific host of movie nights on Channel 2.

As “Gloom” he wore a fright wig, heavy makeup—including a dangling eyeball—and introduced the segment by rising out of a coffin. He started a fan club called the “Dracula Deadbeats.” Young viewers wanted to meet this Claude Gloom character so much they arrived in throngs at the Channel 2 studios while he was on the air and banged on the doors. The station had to call the police. The teenage reaction to the show did not go unnoticed by parents. Someone worked up a petition asking the station to take the show off the air because it was keeping kids up too late on Friday nights. They gathered 8,000 signatures. After airing the program for eight months, the station finally dropped it.

As a TV weatherman in the early days, Holtman had none of the computer-generated graphics we’re used to seeing today. He had magnetic sun symbols, clouds, rain, etc., that he slapped on a metal map. He wrote in temperatures with a marker having memorized them before the red light on the studio camera came on. Commercials were recorded on film, which was prone to breaking. Holtman was always ready with something to say about the weather elsewhere in the country if a film broke and he had to fill time.

Some of the same technical issues, such as breaking tape, plagued him on the radio side. Holtman was always prepared, planning his morning shows a day ahead of time, writing himself scripts and jokes to read between records. He played mostly top 40 tunes, though he’d throw in a polka at least once a day to keep listeners on their toes. In the 60s he was forbidden to play “race records” as they were sometimes called. That meant no Motown, which he personally loved.

From the late 70s until he retired in 1999, Marty Holtman moved full-time to television. He reported, did local segments that aired during the CBS Morning Show, and kept the Treasure Valley informed about the weather. He also started a promotion that became an institution on Channel 2, Marty’s Santa Express. He took children from the Mountain States Tumor Institute on Christmas adventures, often to Hawaii, and at least once to North Pole, Alaska. He, along with producer Mark Montgomery and cameraman Clyn Richards, received a regional Emmy for that in 1989. In 2000, Marty Holtman received the Silver Circle Award for lifetime achievement from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences.

Marty Holtman during his early days as a weatherman.

Marty Holtman during his early days as a weatherman.  Marty Holtman in 2019 with the Emmy he won for Marty’s Santa Express.

Marty Holtman in 2019 with the Emmy he won for Marty’s Santa Express.

Published on December 09, 2019 04:00

December 8, 2019

The Spiral Highway

The Lewiston Hill road is an engineering marvel. Today it’s a four-lane, divided highway that allows drivers to zip up and down the road at 65 mph, hardly noticing the hill at all, unless you’re driving a truck. That wasn’t the case in 1915.

The Lewiston Spiral Highway was a huge project for the Idaho State Highway Commission in 1915 and 1916. It sucked up so much of the highway fund other parts of the state complained bitterly. But what a project. The road was to start in the valley at 725 feet above sea level, and top the hill above the city at 2,750 feet. That’s less than half a mile, as the crow flies, but Model T’s did not fly. The twisting road would run ten miles forth and back, and back and forth, testing many radiators in the climb.

An article in the September 27, 1916 edition of the Lewiston Morning Tribune reported that “Within just two and six tenths miles of the goal—which is the summit of Lewiston Hill—the big Marion Caterpillar steam shovel is still trembling with willing energy, still digging, still climbing, still creeping out of the valley over its own triumphant trail—a trail destined in time to become one of the noted scenic highways of the west.”

The Spiral Highway, sometimes called Uniontown Hill Road, cost the state and the Lewiston highway district $141,587. Oh, and 42 cents.

There was much demand for the new highway. According to a story in the January 12, 1918, edition of the Idaho Statesman “an actual count made by a man stationed at the Eighteenth street bridge” recorded 1280 cars climbing the hill on a single November day. The same article noted that you could see the Blue Mountains in Oregon to the southwest from the top of the hill.

Safety was a big concern. The Statesman article put everyone’s fears to rest. “The right-of-way has been fenced on both sides for the entire distance. Guarding railings, made of frame material with heavy posts were constructed at exposed points on the grade. Barbed wire was used for the balance of the distance. Both the guarding fencing and the wire are set in far enough on the highway to serve as a guide to autoists going over the road on the darkest nights.”

Oh, blessed barbed wire guiding our nighttime autoists!

The Lewiston Spiral Highway was a huge project for the Idaho State Highway Commission in 1915 and 1916. It sucked up so much of the highway fund other parts of the state complained bitterly. But what a project. The road was to start in the valley at 725 feet above sea level, and top the hill above the city at 2,750 feet. That’s less than half a mile, as the crow flies, but Model T’s did not fly. The twisting road would run ten miles forth and back, and back and forth, testing many radiators in the climb.

An article in the September 27, 1916 edition of the Lewiston Morning Tribune reported that “Within just two and six tenths miles of the goal—which is the summit of Lewiston Hill—the big Marion Caterpillar steam shovel is still trembling with willing energy, still digging, still climbing, still creeping out of the valley over its own triumphant trail—a trail destined in time to become one of the noted scenic highways of the west.”

The Spiral Highway, sometimes called Uniontown Hill Road, cost the state and the Lewiston highway district $141,587. Oh, and 42 cents.

There was much demand for the new highway. According to a story in the January 12, 1918, edition of the Idaho Statesman “an actual count made by a man stationed at the Eighteenth street bridge” recorded 1280 cars climbing the hill on a single November day. The same article noted that you could see the Blue Mountains in Oregon to the southwest from the top of the hill.

Safety was a big concern. The Statesman article put everyone’s fears to rest. “The right-of-way has been fenced on both sides for the entire distance. Guarding railings, made of frame material with heavy posts were constructed at exposed points on the grade. Barbed wire was used for the balance of the distance. Both the guarding fencing and the wire are set in far enough on the highway to serve as a guide to autoists going over the road on the darkest nights.”

Oh, blessed barbed wire guiding our nighttime autoists!

Published on December 08, 2019 04:00

December 7, 2019

Where there's Smoke...

Once, while visiting Hawaii, I had the chance to break off a delicate, lacey piece of lava so new it was still warm. Looking out over that fresh flow it struck me how like it was to some of the features in Craters of the Moon National Monument. There are lava flows there so untouched by seed or seedling that they might have happened yesterday.

Little wonder then that people over the years have sometimes been convinced a new eruption was going on. During the dedication of the monument on June 15, 1924 there was one such startling incident. The day was full of speeches from dignitaries such as energetic Idaho promoter Bob Limbert who almost single-handedly created the monument, C.B. Sampson of Sampson Roads fame, Blackfoot Republican publisher Byrd Trego, and Idaho State Automobile Association President T.E. Bliss. Stirring as the oration probably was, it could not match the belching volcano. While the speakers were still speaking spectators spied smoke boiling up from a nearby crater. Some in the gathering began to move briskly away from the smoke, but Commercial Club President Otto Hoebel calmed the crowd by telling them it was just a stunt designed expressly for the occasion by R.M. Kunze, amateur purveyor of pyrotechnics.

It also was smoke, and allegedly the smell of Sulphur that set gandy dancers on edge during the construction of the Oregon Shortline railroad outside of Shoshone in 1882. Reports were that “Smoke and flame of peculiar odor, color, and shape issued from chasms and seams in the lava beds.” The Idaho Statesman also reported that one observer said, “General commotion over the lava fields and unusual agitation of the boiling springs cause many railroad hands to leave, terror stricken. The whole area has the appearance from a distance of being on fire.”

Was the whole area on fire? That is, were workers spotting one or more range fires, never uncommon on the Idaho desert? There were reports of lava glowing at night and even bubbling. Indians from Fort Hall scoffed at the concern of the railroaders, saying that it happened regularly when the devil had a bellyache. There was also a rumor that rival railroaders were starting fires and spreading chemicals around to scare off the Oregon Shortline men. When the rains came, the smoke went away along with the concerns of the workers.

In 1911, reports—if not fresh lava—circulated again. The Blackfoot Republican, published south and a bit east of the lava fields quoted A.E. Byers of Blackfoot as saying smoke and great quantities of gas “rose to great height and spread like an umbrella.” Meanwhile residents who lived near the smoke thought it was just a brush fire.

No doubt many have looked out across that landscape, seeing smoke, perhaps even emanating from one of the three volcanic buttes in the area, and had a moment of pause. At that moment they might not have been comforted by the fact that park rangers speculate the most recent eruption was about 2,000 years ago.

Not an actual working volcano.

Not an actual working volcano.

Little wonder then that people over the years have sometimes been convinced a new eruption was going on. During the dedication of the monument on June 15, 1924 there was one such startling incident. The day was full of speeches from dignitaries such as energetic Idaho promoter Bob Limbert who almost single-handedly created the monument, C.B. Sampson of Sampson Roads fame, Blackfoot Republican publisher Byrd Trego, and Idaho State Automobile Association President T.E. Bliss. Stirring as the oration probably was, it could not match the belching volcano. While the speakers were still speaking spectators spied smoke boiling up from a nearby crater. Some in the gathering began to move briskly away from the smoke, but Commercial Club President Otto Hoebel calmed the crowd by telling them it was just a stunt designed expressly for the occasion by R.M. Kunze, amateur purveyor of pyrotechnics.

It also was smoke, and allegedly the smell of Sulphur that set gandy dancers on edge during the construction of the Oregon Shortline railroad outside of Shoshone in 1882. Reports were that “Smoke and flame of peculiar odor, color, and shape issued from chasms and seams in the lava beds.” The Idaho Statesman also reported that one observer said, “General commotion over the lava fields and unusual agitation of the boiling springs cause many railroad hands to leave, terror stricken. The whole area has the appearance from a distance of being on fire.”

Was the whole area on fire? That is, were workers spotting one or more range fires, never uncommon on the Idaho desert? There were reports of lava glowing at night and even bubbling. Indians from Fort Hall scoffed at the concern of the railroaders, saying that it happened regularly when the devil had a bellyache. There was also a rumor that rival railroaders were starting fires and spreading chemicals around to scare off the Oregon Shortline men. When the rains came, the smoke went away along with the concerns of the workers.

In 1911, reports—if not fresh lava—circulated again. The Blackfoot Republican, published south and a bit east of the lava fields quoted A.E. Byers of Blackfoot as saying smoke and great quantities of gas “rose to great height and spread like an umbrella.” Meanwhile residents who lived near the smoke thought it was just a brush fire.

No doubt many have looked out across that landscape, seeing smoke, perhaps even emanating from one of the three volcanic buttes in the area, and had a moment of pause. At that moment they might not have been comforted by the fact that park rangers speculate the most recent eruption was about 2,000 years ago.

Not an actual working volcano.

Not an actual working volcano.

Published on December 07, 2019 04:00