Rick Just's Blog, page 181

November 6, 2019

Sandpoint's Cedar Street Bridge

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

What do you do with a bridge that has outlived its usefulness? Often old bridges are sold and moved to a new location, or torn down for scrap. Not the Cedar Creek Bridge in Sandpoint.

The 400-foot-long bridge was built sometime in the 1920s so that pedestrians and cars could go from downtown Sandpoint to the railroad depot. As travel by rail became less popular, so did the bridge. By the 1970s it had fallen into disuse. The city blocked off the decaying bridge to traffic.

In the early 80s city officials were thinking about tearing it down when local entrepreneur Scott Glickenhaus approached them with an idea. He had seen the Ponte Vecchio, the oldest bridge in Florence, Italy. That bridge had housed shops as well as functioning as a bridge since the 13th century. Why not something like that in Sandpoint?

The derelict bridge was reinforced with new pilings, and a new enclosed structure was built on top of it from tamarack timbers. Shop spaces were built and rented. The bridge/mini-mall was opened in 1983. Coldwater Creek leased a small space on the bridge in 1988. Then a small mail-order retailer in Sandpoint, this was Coldwater Creek’s first retail store.

By 1995, Coldwater Creek had leased the entire bridge, which is about 16,000 square feet of space. In 2005 Coldwater Creek converted a downtown building for its use and moved out of the bridge.

A Sandpoint group purchased the bridge in 2006 and put over a million dollars into renovations. Today the Cedar Street Bridge hosts cart vendors, restaurants, gift shops, and boutiques and is a key feature of downtown Sandpoint.

What do you do with a bridge that has outlived its usefulness? Often old bridges are sold and moved to a new location, or torn down for scrap. Not the Cedar Creek Bridge in Sandpoint.

The 400-foot-long bridge was built sometime in the 1920s so that pedestrians and cars could go from downtown Sandpoint to the railroad depot. As travel by rail became less popular, so did the bridge. By the 1970s it had fallen into disuse. The city blocked off the decaying bridge to traffic.

In the early 80s city officials were thinking about tearing it down when local entrepreneur Scott Glickenhaus approached them with an idea. He had seen the Ponte Vecchio, the oldest bridge in Florence, Italy. That bridge had housed shops as well as functioning as a bridge since the 13th century. Why not something like that in Sandpoint?

The derelict bridge was reinforced with new pilings, and a new enclosed structure was built on top of it from tamarack timbers. Shop spaces were built and rented. The bridge/mini-mall was opened in 1983. Coldwater Creek leased a small space on the bridge in 1988. Then a small mail-order retailer in Sandpoint, this was Coldwater Creek’s first retail store.

By 1995, Coldwater Creek had leased the entire bridge, which is about 16,000 square feet of space. In 2005 Coldwater Creek converted a downtown building for its use and moved out of the bridge.

A Sandpoint group purchased the bridge in 2006 and put over a million dollars into renovations. Today the Cedar Street Bridge hosts cart vendors, restaurants, gift shops, and boutiques and is a key feature of downtown Sandpoint.

Published on November 06, 2019 04:00

November 5, 2019

Byrd Trego Arrested

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

On Sunday I wrote about Sagehurst, the Blackfoot home of Byrd and Susie Trego. It was a place where the Tregos loved to garden and entertain. But in 1913 a darkness fell over the home.

Byrd Trego was the editor of The Blackfoot Republican. The Morning News can trace its roots back to that paper. Trego was the original Blackfoot Booster, sometimes called “The One-Man Chamber of Commerce.” At that time there was a competing newspaper, The Blackfoot Optimist.

While doing research on Sagehurst, I was startled to see a front-page story about the arrest of Byrd Trego. In May 1913 he was arrested for assaulting a young girl who was living in the Trego home. The Optimist followed the case doggedly in the coming weeks. The Blackfoot Republican was silent about it.

The Tregos, who had no children of their own, took in a 13-year-old girl by the name of Nellie Ray from the Home Finding Society of Boise to raise as their own. According to the couple’s account she became increasingly hard to handle during the three years they had her, sneaking away to dances and the like. She was given chances to reform but did not take them. Finally, the Tregos resolved to send her back to the Orphan’s Home in Boise. As the date for her departure neared, Nellie became more and more disruptive. The Tregos soon put her on a train to Boise.

Once back in Boise, Nellie told her story of abuse by Byrd Trego. Then, she recanted her story, only to switch back to the original version. On the strength of the Home superintendent’s report, authorities in Blackfoot arrested editor Trego.

The Optimist covered the trial of Trego gleefully, calling him “a fiend in human form” and reporting the alleged offense in detail, while stating “the exact words used by the prosecuting witness (Nellie Ray) are not reproduced here, for while they might not affect the older readers, the story against this child as told in her own language is too suggestive for children to read.”

On June 12, 1913, the Optimist reported that jurors had deliberated for 13 hours and brought back a verdict of guilty. The smallest of the four stacked headlines on the story read, “Heinousness of Offense Does Not Seem to Penetrate Mind of Inhuman Brute Upon Whom Rests the Charge of Wrecking Life.”

So, dark days indeed at Sagehurst. And still, nothing from the Idaho Republican. That is until months later when the paper’s banner headline read, “Trego Case Reversed by Supreme Court.” That was on March 6, 1914.

The Idaho Supreme Court excoriated the lower court, prosecutors, and witnesses in the original trial, pointing out gross inconsistencies in Nellie Ray’s story, stating that records showed she clearly testified falsely, and that she wanted to “get even” with the Tregos. “From the entire evidence, this court is warranted in assuming that the jury must have rendered the verdict under the influence of passion and prejudice,” the ruling read.

Now, suddenly, the Blackfoot Republican broke its silence. Byrd Trego had been advised by attorneys to stay mum while the case was on appeal. Now he had something to say. That something went on for thousands of words in a series of six weekly articles titled “The Conspiracy of the Twenty-Three.” He went on in excruciating detail about how local enemies had set him up.

Meanwhile, it was the Blackfoot Optimist taking a turn at silence. The paper reported the reversal by the Idaho Supreme Court in matter-of-fact terms, then moved on as if nothing had happened.

So, the dark veil was lifted from Sagehurst. The scandal that threatened the lives of the Tregos was abruptly behind them. Byrd Trego would edit The Idaho Republican until 1927, when it would merge with The Evening Bulletin to become The Daily Bulletin. Trego would continue as co-editor and co-publisher of that paper until his retirement in 1939 after 35 years in the newspaper business in Blackfoot. He died April 2, 1957. Susie Trego preceded him in death, passing away in 1937. Byrd Trego, editor and publisher of the Blackfoot Republican. Image courtesy of the Bingham County Historical Society Archives.

Byrd Trego, editor and publisher of the Blackfoot Republican. Image courtesy of the Bingham County Historical Society Archives.

On Sunday I wrote about Sagehurst, the Blackfoot home of Byrd and Susie Trego. It was a place where the Tregos loved to garden and entertain. But in 1913 a darkness fell over the home.

Byrd Trego was the editor of The Blackfoot Republican. The Morning News can trace its roots back to that paper. Trego was the original Blackfoot Booster, sometimes called “The One-Man Chamber of Commerce.” At that time there was a competing newspaper, The Blackfoot Optimist.

While doing research on Sagehurst, I was startled to see a front-page story about the arrest of Byrd Trego. In May 1913 he was arrested for assaulting a young girl who was living in the Trego home. The Optimist followed the case doggedly in the coming weeks. The Blackfoot Republican was silent about it.

The Tregos, who had no children of their own, took in a 13-year-old girl by the name of Nellie Ray from the Home Finding Society of Boise to raise as their own. According to the couple’s account she became increasingly hard to handle during the three years they had her, sneaking away to dances and the like. She was given chances to reform but did not take them. Finally, the Tregos resolved to send her back to the Orphan’s Home in Boise. As the date for her departure neared, Nellie became more and more disruptive. The Tregos soon put her on a train to Boise.

Once back in Boise, Nellie told her story of abuse by Byrd Trego. Then, she recanted her story, only to switch back to the original version. On the strength of the Home superintendent’s report, authorities in Blackfoot arrested editor Trego.

The Optimist covered the trial of Trego gleefully, calling him “a fiend in human form” and reporting the alleged offense in detail, while stating “the exact words used by the prosecuting witness (Nellie Ray) are not reproduced here, for while they might not affect the older readers, the story against this child as told in her own language is too suggestive for children to read.”

On June 12, 1913, the Optimist reported that jurors had deliberated for 13 hours and brought back a verdict of guilty. The smallest of the four stacked headlines on the story read, “Heinousness of Offense Does Not Seem to Penetrate Mind of Inhuman Brute Upon Whom Rests the Charge of Wrecking Life.”

So, dark days indeed at Sagehurst. And still, nothing from the Idaho Republican. That is until months later when the paper’s banner headline read, “Trego Case Reversed by Supreme Court.” That was on March 6, 1914.

The Idaho Supreme Court excoriated the lower court, prosecutors, and witnesses in the original trial, pointing out gross inconsistencies in Nellie Ray’s story, stating that records showed she clearly testified falsely, and that she wanted to “get even” with the Tregos. “From the entire evidence, this court is warranted in assuming that the jury must have rendered the verdict under the influence of passion and prejudice,” the ruling read.

Now, suddenly, the Blackfoot Republican broke its silence. Byrd Trego had been advised by attorneys to stay mum while the case was on appeal. Now he had something to say. That something went on for thousands of words in a series of six weekly articles titled “The Conspiracy of the Twenty-Three.” He went on in excruciating detail about how local enemies had set him up.

Meanwhile, it was the Blackfoot Optimist taking a turn at silence. The paper reported the reversal by the Idaho Supreme Court in matter-of-fact terms, then moved on as if nothing had happened.

So, the dark veil was lifted from Sagehurst. The scandal that threatened the lives of the Tregos was abruptly behind them. Byrd Trego would edit The Idaho Republican until 1927, when it would merge with The Evening Bulletin to become The Daily Bulletin. Trego would continue as co-editor and co-publisher of that paper until his retirement in 1939 after 35 years in the newspaper business in Blackfoot. He died April 2, 1957. Susie Trego preceded him in death, passing away in 1937.

Byrd Trego, editor and publisher of the Blackfoot Republican. Image courtesy of the Bingham County Historical Society Archives.

Byrd Trego, editor and publisher of the Blackfoot Republican. Image courtesy of the Bingham County Historical Society Archives.

Published on November 05, 2019 04:00

November 4, 2019

Those Elusive Chinese Tunnels

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

I enter the Chinese tunnels of Boise with some trepidation, knowing that opinions are strong and documentation is weak. Actually, let’s say I enter the debate, since the tunnels themselves are so elusive.

There were many newspaper mentions of tunnels built by Chinese laborers in the late 1800s. They weren’t in Boise, though. The stories that mentioned the tunnels were about mining in the mountains.

Boise had a substantial Chinese population in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but did they build tunnels? If they didn’t, where did the myth come from? There were Chinese tunnels, most famously in San Francisco. Portland had a network called the Shanghai tunnels. Los Angeles had Chinese tunnels. Did Boise?

I searched for mention of them in digital scans of the Statesman from those years and turned up nothing. The first mention I found of Chinese tunnels in the Statesman was in a column by Dick d’Easum in 1961. He was addressing the “myth” of the tunnels and speculating on how it got started. There were underground rooms that led off basements in the Chinese section of the city. It was said that illicit activities sometimes occurred there, such as the smoking of opium. What did not seem to be the case was that those rooms connected in a network beneath the city that would allow someone to enter at one point and pop up blocks away.

One possible source of the tunnel stories was the prevalence of unauthorized sewers. Today we hear of sinkholes opening up and swallowing cars. In Boise in the 1880s such sinkholes could make horses disappear. Dick d’Easum told of a wagon loaded with merchandise that suddenly sank half out of sight on Idaho Street. The struggling team of horses were soon pulled into the widening hole. A Chinese sewer was the cause. Once the team and wagon were extricated it was filled in. The city engineer found more unauthorized sewers and the city council decreed that they all be filled in.

Over the years Boise has had countless street and utility projects, not to mention the construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction of numerous buildings. No Chinese tunnels have been found. Yet, the myth persists. That’s partly because one can’t prove a negative such as this. There MIGHT be a system of tunnels somewhere that have yet to be found. Dig deeper, maybe. Great Uncle Hyrum said he saw them.

By the way, the graphic is supposed to be “China Tunnel” in pinyin, if you can trust those internet translation services.

I enter the Chinese tunnels of Boise with some trepidation, knowing that opinions are strong and documentation is weak. Actually, let’s say I enter the debate, since the tunnels themselves are so elusive.

There were many newspaper mentions of tunnels built by Chinese laborers in the late 1800s. They weren’t in Boise, though. The stories that mentioned the tunnels were about mining in the mountains.

Boise had a substantial Chinese population in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but did they build tunnels? If they didn’t, where did the myth come from? There were Chinese tunnels, most famously in San Francisco. Portland had a network called the Shanghai tunnels. Los Angeles had Chinese tunnels. Did Boise?

I searched for mention of them in digital scans of the Statesman from those years and turned up nothing. The first mention I found of Chinese tunnels in the Statesman was in a column by Dick d’Easum in 1961. He was addressing the “myth” of the tunnels and speculating on how it got started. There were underground rooms that led off basements in the Chinese section of the city. It was said that illicit activities sometimes occurred there, such as the smoking of opium. What did not seem to be the case was that those rooms connected in a network beneath the city that would allow someone to enter at one point and pop up blocks away.

One possible source of the tunnel stories was the prevalence of unauthorized sewers. Today we hear of sinkholes opening up and swallowing cars. In Boise in the 1880s such sinkholes could make horses disappear. Dick d’Easum told of a wagon loaded with merchandise that suddenly sank half out of sight on Idaho Street. The struggling team of horses were soon pulled into the widening hole. A Chinese sewer was the cause. Once the team and wagon were extricated it was filled in. The city engineer found more unauthorized sewers and the city council decreed that they all be filled in.

Over the years Boise has had countless street and utility projects, not to mention the construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction of numerous buildings. No Chinese tunnels have been found. Yet, the myth persists. That’s partly because one can’t prove a negative such as this. There MIGHT be a system of tunnels somewhere that have yet to be found. Dig deeper, maybe. Great Uncle Hyrum said he saw them.

By the way, the graphic is supposed to be “China Tunnel” in pinyin, if you can trust those internet translation services.

Published on November 04, 2019 04:00

November 3, 2019

Sagehurst

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

I’m guessing few of you have named your house anything more formal than “our place.” There’s one house in Blackfoot that has a beautiful—though some might say pretentious—name. The house is called Sagehurst.

The editor and publisher of the Blackfoot Republican, eventually absorbed by the Daily Bulletin the predecessor of the Morning News built and named Sagehurst in 1909. That was a couple of years before the Idaho Legislature made it possible to legally register a house name. Even so, Sagehurst was not the first house name to be officially registered in Bingham County. That achievement belonged to Grove Farm in Groveland, the home of Ernest F. Hale.

It was Sagehurst that made the papers time and again, though, in no small part because its owner, Byrd Trego, also owned the Blackfoot Republican. Sagehurst was often mentioned in society stories when teas were held there and when dignitaries from out of town would visit. Sagehurst was so named by Trego’s wife, Susie, because she painted many of the rooms the color of sagebrush. “Hurst” means a grove, hill, or nest.

Sagehurst was frequently mentioned in the Blackfoot Republican, almost as if it were a community gathering center. It was common at the time for people to report to the papers visits from friends and overnight guests. Those reports from Sagehurst stood out because the home was named, and because the guests were often dignitaries from out of town, especially politicians and newspaper editors.

The construction of a garage was seldom with a newspaper mention, but when one was added to Sagehurst in 1920, editor Trego treated readers to a full description of the two-car addition from its nearly flat roof “covered in Ruberoid” to the special cinder and clay floor designed to drain liquids such as the contents of radiators without the need for a sewer connection.

Mrs. Byrd Trego (as her byline read), sometimes called the “silent editor” of the paper, wrote lengthy articles about gardening, often mentioning the latest plantings at Sagehurst. The Tregos were big Blackfoot boosters who took great pride in their community and landscaped their home as a reflection of that. Midnight raids on flower beds were not uncommon, so the Tregos planted sections of their front yard with flowers meant for cutting and invited the community to stop by and pick a few for Blackfoot vases. The hope was that blossom hoodlums would leave the rest of the plants alone.

In 1917, on the occasion of the opening of the Shelley sugar factory, Byrd Trego announced that he had “four million seeds, hadn’t time to plant them all himself, and (he) called upon the north end of the county to help put them in the ground where they would add the most beauty to the country.” He spent two hours handing out varicolored hollyhock and garden variety perennial peas. No doubt there are still flowers around the county that can be traced to the seeds from Sagehurst.

Sagehurst was, and still is, a place of beauty. But there would be many months in 1913 and 1914 that would be remembered by the Tregos as dark days in the home. That story on Tuesday. Sagehurst, courtesy of the Bingham County Historical Society Archives.

Sagehurst, courtesy of the Bingham County Historical Society Archives.

The editor and publisher of the Blackfoot Republican, eventually absorbed by the Daily Bulletin the predecessor of the Morning News built and named Sagehurst in 1909. That was a couple of years before the Idaho Legislature made it possible to legally register a house name. Even so, Sagehurst was not the first house name to be officially registered in Bingham County. That achievement belonged to Grove Farm in Groveland, the home of Ernest F. Hale.

It was Sagehurst that made the papers time and again, though, in no small part because its owner, Byrd Trego, also owned the Blackfoot Republican. Sagehurst was often mentioned in society stories when teas were held there and when dignitaries from out of town would visit. Sagehurst was so named by Trego’s wife, Susie, because she painted many of the rooms the color of sagebrush. “Hurst” means a grove, hill, or nest.

Sagehurst was frequently mentioned in the Blackfoot Republican, almost as if it were a community gathering center. It was common at the time for people to report to the papers visits from friends and overnight guests. Those reports from Sagehurst stood out because the home was named, and because the guests were often dignitaries from out of town, especially politicians and newspaper editors.

The construction of a garage was seldom with a newspaper mention, but when one was added to Sagehurst in 1920, editor Trego treated readers to a full description of the two-car addition from its nearly flat roof “covered in Ruberoid” to the special cinder and clay floor designed to drain liquids such as the contents of radiators without the need for a sewer connection.

Mrs. Byrd Trego (as her byline read), sometimes called the “silent editor” of the paper, wrote lengthy articles about gardening, often mentioning the latest plantings at Sagehurst. The Tregos were big Blackfoot boosters who took great pride in their community and landscaped their home as a reflection of that. Midnight raids on flower beds were not uncommon, so the Tregos planted sections of their front yard with flowers meant for cutting and invited the community to stop by and pick a few for Blackfoot vases. The hope was that blossom hoodlums would leave the rest of the plants alone.

In 1917, on the occasion of the opening of the Shelley sugar factory, Byrd Trego announced that he had “four million seeds, hadn’t time to plant them all himself, and (he) called upon the north end of the county to help put them in the ground where they would add the most beauty to the country.” He spent two hours handing out varicolored hollyhock and garden variety perennial peas. No doubt there are still flowers around the county that can be traced to the seeds from Sagehurst.

Sagehurst was, and still is, a place of beauty. But there would be many months in 1913 and 1914 that would be remembered by the Tregos as dark days in the home. That story on Tuesday.

Sagehurst, courtesy of the Bingham County Historical Society Archives.

Sagehurst, courtesy of the Bingham County Historical Society Archives.

Published on November 03, 2019 04:00

November 2, 2019

Betsey Ross in Coeur d'Alene

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

Not all that is written in stone is true. I did a post earlier about a monument memorializing a (probably) nonexistent massacre near Almo. We can trace the roots of that one and get at least an inkling of why the memorial exists. Not so with the memorial to Betsey Ross in the Forest Memorial Cemetery in Coeur d’Alene.

Yes, it is apparently supposed to honor the woman of flag-making legend, although her name did not have that extra E. She died in Philadelphia in 1836. This memorial doesn’t say she’s buried in Coeur d’Alene, just that she is being honored by one of her descendants, B.M. Ross. On one side of the monument B.M. Ross is listed as the son of James and Betsey Ross, born in 1834. Interesting, in that Betsy Ross would have been 82 in 1834, two years before she died. Also, she had seven daughters and no sons.

The Coeur d’Alene Parks Department, which manages the cemeteries in the city, has done an excellent walking tour brochure about the history buried (sorry) in the cemetery. That’s where I found most of the information for this post. If you know anything about Betsey Ross or B.M. Ross, they’d love to hear about it. Clearly someone spent quite a bit of money to put up the monument. The question is, why?

Not all that is written in stone is true. I did a post earlier about a monument memorializing a (probably) nonexistent massacre near Almo. We can trace the roots of that one and get at least an inkling of why the memorial exists. Not so with the memorial to Betsey Ross in the Forest Memorial Cemetery in Coeur d’Alene.

Yes, it is apparently supposed to honor the woman of flag-making legend, although her name did not have that extra E. She died in Philadelphia in 1836. This memorial doesn’t say she’s buried in Coeur d’Alene, just that she is being honored by one of her descendants, B.M. Ross. On one side of the monument B.M. Ross is listed as the son of James and Betsey Ross, born in 1834. Interesting, in that Betsy Ross would have been 82 in 1834, two years before she died. Also, she had seven daughters and no sons.

The Coeur d’Alene Parks Department, which manages the cemeteries in the city, has done an excellent walking tour brochure about the history buried (sorry) in the cemetery. That’s where I found most of the information for this post. If you know anything about Betsey Ross or B.M. Ross, they’d love to hear about it. Clearly someone spent quite a bit of money to put up the monument. The question is, why?

Published on November 02, 2019 04:00

November 1, 2019

Bogus Basin's Skiing History

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

Downhill skiing has been around for a while, but maybe not as long as you think. It started to emerge as a recreational pursuit in the 19th century and didn’t become an Olympic sport, in the form of slalom racing, until 1936. That same year, in December, the Sun Valley Ski Resort opened in Idaho, becoming the first destination winter resort in the U.S.

Young, fit Boiseans, enthralled with Sun Valley, were eager to bring this new sport of downhill skiing closer to home. They formed the Boise Ski Club at a time when all skis were made of hickory and ski poles were made from bamboo.

The most convenient places to ski were at the American Legion Golf Course at the end of 8th Street, and on the summit of Horseshoe Bend Hill. Both meant a fair amount of trudging. Even so, the members of the ski club were hooked. They began looking for a better place to ski close to town.

Alf Engen of Sun Valley was an early competitive skier and ski-jumper commissioned by the Forest Service to look for a site on the Boise National Forest that might work. Joining him in the search were Boise Ski Club President John Hearne and Boise Forest Landscape Architect Yale Moeller. They did some trudging, some looking, and a lot of skiing from Horseshoe Bend Hill to Pilot’s Peak near Idaho City—some 85 miles across the ridges—before settling on Shafer Butte and nearby Deer Point, a site that seemed to offer dependable snow.

Of course, finding the site and getting people up the hill to enjoy it were two different things. The Boise Jaycees backed the effort to develop a ski area. They applied for and received a Works Project Administration (WPA) grant to build a road to the site and provide some basic utilities along with picnic and camping facilities. The road project began in 1938 and would end up costing $307,000.

Bogus Basin Road is today one of the most prominent facilities in southwestern Idaho that owes its existence to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). It took 120 men to accomplish the road work, while another 75 CCCs built facilities on the mountain.

The opening of the ski area was delayed a year because of World War II. Bogus Basin opened on December 20, 1942, with 200 skiers coming out to test the slopes, 50 of them soldiers from Gowen Field. Many carpooled up the road because of gas rationing. Skiing that day was delayed a bit because someone had stolen the cable from the lift, and it had to be replaced.

Early in the road’s history, the popularity of the ski area caused a major change to something we take for granted today. The City of Boise had selected a site not far from Bogus Basin road as the location of a landfill. Skiers put the kibosh to that, and the landfill was built where it is today, near Seamans Gulch.

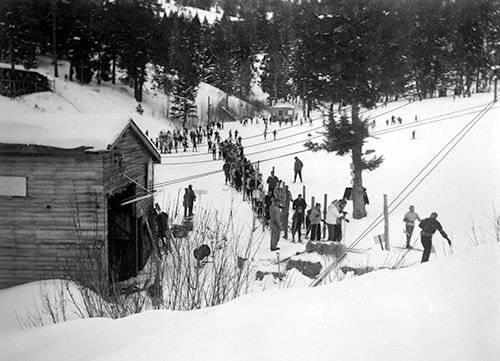

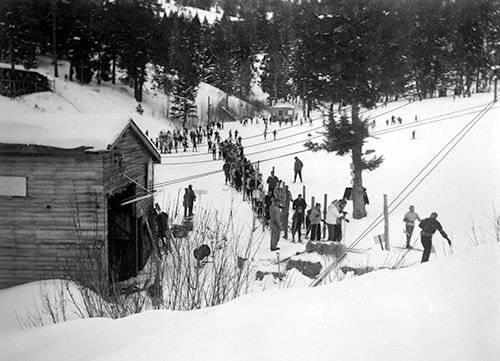

Bogus Basin today is better than ever with snow-making capabilities, jazzy lifts, and a panoply of summer activities from a climbing wall to the Glade Runner mountain slider. During the 2018-19 season, they hosted 377,000 visitors, quite a jump from that first 200-visitor day. There is much more fascinating history than I can plug into a short column. I recommend Building Bogus Basin by Eve Chandler if you’d like to find out more. Skiers lined up for the Bogus Basin rope tow in 1950. The first rope tow on the mountain was powered by a Model A engine. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-164-116e.

Skiers lined up for the Bogus Basin rope tow in 1950. The first rope tow on the mountain was powered by a Model A engine. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-164-116e.

Young, fit Boiseans, enthralled with Sun Valley, were eager to bring this new sport of downhill skiing closer to home. They formed the Boise Ski Club at a time when all skis were made of hickory and ski poles were made from bamboo.

The most convenient places to ski were at the American Legion Golf Course at the end of 8th Street, and on the summit of Horseshoe Bend Hill. Both meant a fair amount of trudging. Even so, the members of the ski club were hooked. They began looking for a better place to ski close to town.

Alf Engen of Sun Valley was an early competitive skier and ski-jumper commissioned by the Forest Service to look for a site on the Boise National Forest that might work. Joining him in the search were Boise Ski Club President John Hearne and Boise Forest Landscape Architect Yale Moeller. They did some trudging, some looking, and a lot of skiing from Horseshoe Bend Hill to Pilot’s Peak near Idaho City—some 85 miles across the ridges—before settling on Shafer Butte and nearby Deer Point, a site that seemed to offer dependable snow.

Of course, finding the site and getting people up the hill to enjoy it were two different things. The Boise Jaycees backed the effort to develop a ski area. They applied for and received a Works Project Administration (WPA) grant to build a road to the site and provide some basic utilities along with picnic and camping facilities. The road project began in 1938 and would end up costing $307,000.

Bogus Basin Road is today one of the most prominent facilities in southwestern Idaho that owes its existence to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). It took 120 men to accomplish the road work, while another 75 CCCs built facilities on the mountain.

The opening of the ski area was delayed a year because of World War II. Bogus Basin opened on December 20, 1942, with 200 skiers coming out to test the slopes, 50 of them soldiers from Gowen Field. Many carpooled up the road because of gas rationing. Skiing that day was delayed a bit because someone had stolen the cable from the lift, and it had to be replaced.

Early in the road’s history, the popularity of the ski area caused a major change to something we take for granted today. The City of Boise had selected a site not far from Bogus Basin road as the location of a landfill. Skiers put the kibosh to that, and the landfill was built where it is today, near Seamans Gulch.

Bogus Basin today is better than ever with snow-making capabilities, jazzy lifts, and a panoply of summer activities from a climbing wall to the Glade Runner mountain slider. During the 2018-19 season, they hosted 377,000 visitors, quite a jump from that first 200-visitor day. There is much more fascinating history than I can plug into a short column. I recommend Building Bogus Basin by Eve Chandler if you’d like to find out more.

Skiers lined up for the Bogus Basin rope tow in 1950. The first rope tow on the mountain was powered by a Model A engine. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-164-116e.

Skiers lined up for the Bogus Basin rope tow in 1950. The first rope tow on the mountain was powered by a Model A engine. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-164-116e.

Published on November 01, 2019 04:00

October 31, 2019

Sunken Ore

In the late 1880's many thousands of tons of ore were floated across Lake Coeur d'Alene from the Silver Valley mines in the Wallace and Kellogg area. The ore was loaded onto barges at Mission Landing near the Cataldo Mission, and towed by steamer down the Coeur d'Alene River and across the lake. In the winter the ice breaker Kootenai assisted with the job of transporting the ore.

Legend has it that late in the fall of 1889, the captain of the Kootenai received orders to bring two barges, each loaded with 150 tons of ore, down from Mission Landing. The Kootenai pushed one barge and towed the other for a while, but the captain had trouble breaking through the ice, that way.

He decided to tie up the front barge, leaving it behind, and tow the second barge on down to the ice-free lake.

As the story goes, about midnight, near McDonald's Point, on Lake Coeur d'Alene, something happened that caused the loose ore on the barge to shift. The barge tipped first one way, then the other, and 135 tons of high grade silver ore poured into the lake. That was about $15,000 worth in 1889.

So, is there a fortune in ore on the bottom of Lake Coeur d’Alene? The tale is told in the book Lost Treasures and Mines of the Pacific Northwest, by Ruby El Hult. A few other sources mention it, but I’ve yet to find a contemporaneous newspaper account of the incident. Divers have looked for it a few times, without reported success. North Idaho historians (and divers), what say you?

Legend has it that late in the fall of 1889, the captain of the Kootenai received orders to bring two barges, each loaded with 150 tons of ore, down from Mission Landing. The Kootenai pushed one barge and towed the other for a while, but the captain had trouble breaking through the ice, that way.

He decided to tie up the front barge, leaving it behind, and tow the second barge on down to the ice-free lake.

As the story goes, about midnight, near McDonald's Point, on Lake Coeur d'Alene, something happened that caused the loose ore on the barge to shift. The barge tipped first one way, then the other, and 135 tons of high grade silver ore poured into the lake. That was about $15,000 worth in 1889.

So, is there a fortune in ore on the bottom of Lake Coeur d’Alene? The tale is told in the book Lost Treasures and Mines of the Pacific Northwest, by Ruby El Hult. A few other sources mention it, but I’ve yet to find a contemporaneous newspaper account of the incident. Divers have looked for it a few times, without reported success. North Idaho historians (and divers), what say you?

Published on October 31, 2019 04:00

October 30, 2019

Pop Quiz

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). A.B Meyer knew where the gold from a stagecoach robbery was buried. Why?

A. He claimed to be a clairvoyant.

B. He was a passenger in the coach who saw the robbers bury it.

C. He was the stagecoach driver who was in cahoots with the robbers.

D. He was one of robbers who told the location with his dying breath.

E. His brother had given him a map.

2). Who were the Aztec Eagles?

A. A Shoshoni drumming group.

B. A Mexican soccer team that beat the U of I team in 1953.

C. A Mexican air squadron that trained in Pocatello during WWII.

D. Raptors brought back from the brink of extinction by the World Center for Birds of Prey.

E. None of the above.

3). What made Coeur d’Alene’s Fish Inn unique?

A. It was the first to serve tater tots.

B. It was the first to serve finger steaks.

C. It had a stage on its roof where entertainers performed.

D. It was a restaurant built to look like a fish.

E. There was a car show in the parking lot every Wednesday night.

4). What brothers made their last movie partly in Idaho?

A. Don and Patrick Swayze.

B. The Three Stooges.

C. The Marx Brothers.

D. The Coen Brothers.

E. The four Baldwin Brothers.

5) How many Idaho State Flags were there in 1890?

A. 44, one for every county in the state.

B. Only the one in the governor’s office.

C. 16, one for every county in the state.

D. None.

E. 43, the number ordered to represent the 43rd state. Answers

Answers

1, A

2, C

3, D

4, B

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). A.B Meyer knew where the gold from a stagecoach robbery was buried. Why?

A. He claimed to be a clairvoyant.

B. He was a passenger in the coach who saw the robbers bury it.

C. He was the stagecoach driver who was in cahoots with the robbers.

D. He was one of robbers who told the location with his dying breath.

E. His brother had given him a map.

2). Who were the Aztec Eagles?

A. A Shoshoni drumming group.

B. A Mexican soccer team that beat the U of I team in 1953.

C. A Mexican air squadron that trained in Pocatello during WWII.

D. Raptors brought back from the brink of extinction by the World Center for Birds of Prey.

E. None of the above.

3). What made Coeur d’Alene’s Fish Inn unique?

A. It was the first to serve tater tots.

B. It was the first to serve finger steaks.

C. It had a stage on its roof where entertainers performed.

D. It was a restaurant built to look like a fish.

E. There was a car show in the parking lot every Wednesday night.

4). What brothers made their last movie partly in Idaho?

A. Don and Patrick Swayze.

B. The Three Stooges.

C. The Marx Brothers.

D. The Coen Brothers.

E. The four Baldwin Brothers.

5) How many Idaho State Flags were there in 1890?

A. 44, one for every county in the state.

B. Only the one in the governor’s office.

C. 16, one for every county in the state.

D. None.

E. 43, the number ordered to represent the 43rd state.

Answers

Answers1, A

2, C

3, D

4, B

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on October 30, 2019 04:00

October 29, 2019

Gobo Fango

Gobo Fango is not a name you often encounter in Idaho history, memorable as it is. Fango was born in Eastern Cape Colony of what is now South Africa in about 1855. He was a member of the Gcaleka tribe. He was saved from a bloody war with the British that would kill 100,000 of his people, only to end up the victim of a range war some 27 years later in Idaho Territory.

Fango’s desperate, starving mother left him in the crook of a tree when he was three when she could no longer carry him. The sons of Henry and Ruth Talbot, English-speaking settlers, found him. The family adopted Gobo Fango. Or maybe they simply claimed him as property. In either case, they probably saved his life.

The Talbots became converts to the LDS religion. Records of their baptisms exist, though none such for Fango. They smuggled Fango out of the country and into the United States where they found their way to Utah in 1861.

Gobo Fango worked for the Talbots as an indentured servant, by some accounts, as a slave by others. He lived in a shed near their home. When a teenager he was sold, or given to another Mormon family.

Eventually Fango was on his own and working for a sheep operation near Oakley, in Idaho Territory. He was even able to acquire a herd of his own.

Cattlemen viewed sheep as a scourge that was destroying the range. Range wars broke out all over the West between sheep men and cattlemen.

It was one of those conflicts that brought an end to Gobo Fango.

The Idaho Territorial Legislature had passed a law known as the Two-Mile Limit intended to keep sheep grazers at least two miles away from a cattleman’s grazing claim. Early one day cattleman Frank Bedke and a companion rode into Fango’s camp to tell him he and his sheep were too close to Bedke’s claim and that he should leave. Fango resisted. Exactly what happened will never be known, but the black man ended up with a bullet passing through the back of his head and another tearing through his abdomen.

The cattlemen rode away. Gobo Fango, who, incredibly, was still alive, began crawling toward his employer’s home, holding his intestines in his hand as he dragged himself four and half miles.

Gobo Fango lived four or five days before succumbing to his wounds. He made out a will leaving his money and property to friends. Frank Bedke would be tried twice for his murder, with the first trial ending with a hung jury. The second time he was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

The headstone of Gobo Fango can be seen today in the Oakley Cemetery.

Fango’s desperate, starving mother left him in the crook of a tree when he was three when she could no longer carry him. The sons of Henry and Ruth Talbot, English-speaking settlers, found him. The family adopted Gobo Fango. Or maybe they simply claimed him as property. In either case, they probably saved his life.

The Talbots became converts to the LDS religion. Records of their baptisms exist, though none such for Fango. They smuggled Fango out of the country and into the United States where they found their way to Utah in 1861.

Gobo Fango worked for the Talbots as an indentured servant, by some accounts, as a slave by others. He lived in a shed near their home. When a teenager he was sold, or given to another Mormon family.

Eventually Fango was on his own and working for a sheep operation near Oakley, in Idaho Territory. He was even able to acquire a herd of his own.

Cattlemen viewed sheep as a scourge that was destroying the range. Range wars broke out all over the West between sheep men and cattlemen.

It was one of those conflicts that brought an end to Gobo Fango.

The Idaho Territorial Legislature had passed a law known as the Two-Mile Limit intended to keep sheep grazers at least two miles away from a cattleman’s grazing claim. Early one day cattleman Frank Bedke and a companion rode into Fango’s camp to tell him he and his sheep were too close to Bedke’s claim and that he should leave. Fango resisted. Exactly what happened will never be known, but the black man ended up with a bullet passing through the back of his head and another tearing through his abdomen.

The cattlemen rode away. Gobo Fango, who, incredibly, was still alive, began crawling toward his employer’s home, holding his intestines in his hand as he dragged himself four and half miles.

Gobo Fango lived four or five days before succumbing to his wounds. He made out a will leaving his money and property to friends. Frank Bedke would be tried twice for his murder, with the first trial ending with a hung jury. The second time he was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

The headstone of Gobo Fango can be seen today in the Oakley Cemetery.

Published on October 29, 2019 04:00

October 28, 2019

Massacres and Massacres

I’ve been reading Rod Miller’s excellent book,

Massacre at Bear River, First, Worst, Forgotten

. It is a detailed account of the worst Indian massacre in history, but includes a fascinating account of conditions leading up to the 1863 incident.

Miller discusses violence committed by and against Indians during the settlement of the West. He points out that more travelers were killed by the accidental discharge of weapons than by indigenous people.

When we think of Indian attacks, the circling of wagons comes to mind. Those wagons are probably on the plains, if the images from motion pictures are a guide. So, Plains Indians get the blame, or credit, depending on your point of view.

Miller says, “Careful research into the peak years of overland emigration, 1840 through 1860, shows that of more than 300,000 white travelers, only 362 were killed by Indians. Very few were killed by the celebrated tribes of the Great Plains.” He goes on to point out that about 90 percent of those who were killed by Indians died west of South Pass.

“In other words,” Miller says, “the vast majority of clashes and killings between native tribes and westbound settlers occurred in the heart of Shoshoni homelands.”

The Shoshoni often vigorously defended their land. Defense, of course, can seem like aggression when viewed through the eyes of those under fire.

So, the Bear River Massacre, deplorable as it was, did not take place in some alcove of history free from previous conflict. Was it a response by Col. Conner and his troops that was out of scale in comparison to previous attacks by Shoshonis? Yes. But how many dead would have been the perfect rejoinder?

The death toll at the Bear River Massacre can never be known with certainty. Contemporaneous reports place the loss to the Shoshonis as high as 496. That means that the military retaliation on that frigid January day in 1863 may have killed, in one attack, more Indians than the number of whites killed by Indians during the westward migration.

The site of the Bear River Massacre, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The site of the Bear River Massacre, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Miller discusses violence committed by and against Indians during the settlement of the West. He points out that more travelers were killed by the accidental discharge of weapons than by indigenous people.

When we think of Indian attacks, the circling of wagons comes to mind. Those wagons are probably on the plains, if the images from motion pictures are a guide. So, Plains Indians get the blame, or credit, depending on your point of view.

Miller says, “Careful research into the peak years of overland emigration, 1840 through 1860, shows that of more than 300,000 white travelers, only 362 were killed by Indians. Very few were killed by the celebrated tribes of the Great Plains.” He goes on to point out that about 90 percent of those who were killed by Indians died west of South Pass.

“In other words,” Miller says, “the vast majority of clashes and killings between native tribes and westbound settlers occurred in the heart of Shoshoni homelands.”

The Shoshoni often vigorously defended their land. Defense, of course, can seem like aggression when viewed through the eyes of those under fire.

So, the Bear River Massacre, deplorable as it was, did not take place in some alcove of history free from previous conflict. Was it a response by Col. Conner and his troops that was out of scale in comparison to previous attacks by Shoshonis? Yes. But how many dead would have been the perfect rejoinder?

The death toll at the Bear River Massacre can never be known with certainty. Contemporaneous reports place the loss to the Shoshonis as high as 496. That means that the military retaliation on that frigid January day in 1863 may have killed, in one attack, more Indians than the number of whites killed by Indians during the westward migration.

The site of the Bear River Massacre, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The site of the Bear River Massacre, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Published on October 28, 2019 04:00